Abstract

Living Book—Augmenting Reading for Life, a three-year EU-funded Erasmus + project (September 2016–August 2019), exploited the affordances of augmented reality (AR) and other emerging technologies in order to address the underachievement of European youth in reading skills. The program developed an innovative approach that empowers teachers from upper primary and lower secondary schools (ages 9–15) to ‘augment’ students’ reading experiences through combining offline activities promoting reading literacy with online experiences of books’ ‘virtual augmentation’ and with social dynamics. Various professional learning activities were designed within the project, aimed at strengthening European teachers’ profile and competences in effectively integrating the Living Book approach into their classroom activities, and in dealing with diversified groups of learners, particularly pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds. Teachers also received training in how to involve parents, and particularly those from disadvantaged and/or migrant backgrounds, in proreading activities to back the overall Living Book strategy at home. The current article provides an overview of the main phases of the Living Book project implementation, and of the program’s key activities and outputs. It also outlines the content and structure of the ‘Augmented Teacher’ and ‘Augmented Parent-Trainer’ training courses developed within the project. Finally, it reports on the main insights gained from the pilot testing of the courses and the follow-up classroom experimentation that took place in the project partner countries.

1. Introduction

Poor reading performance combined with a general disinterest for reading has long-term consequences for both individuals and society. In modern societies, reading literacy is seen as a primary skill, allowing citizens to ‘be’ and live in a complex world, to work at higher levels, and to enjoy their lives more fully [1]. Recognizing the importance of reading, the EU Education and Training 2020 (ET 2020) benchmarks, set in 2009, included having less than 15 percent of 15-year-olds being underskilled in reading by 2020 as one of its main targets. Unfortunately, while some EU countries have since made significant progress towards improving their students’ performance in reading skills, other countries are still lagging behind. The percentage of low achievers in reading at the EU level has actually grown in recent years, from 17.8 percent in 2012 to 21.7 percent in 2018, annulling all the progress made since 2009, when it was also 19.5 percent [2]. According to the PISA 2018 results, only four EU Member States (Estonia, Ireland, Finland, and Poland) met the ET 2020 benchmark of less than 15 percent underachievement in reading.

Technological advances provide the opportunity to implement innovative methodologies more suited to the needs of 21st century learners [3], and to create entirely new, student-centered learning environments [4]. These new developments can boost students’ reading engagement by significantly increasing the range and sophistication of possible classroom activities [5]. One promising approach that has been explored lately is the use of augmented reality (AR) tools and applications. AR is an emerging form of reality that enhances individuals’ experiences of the real world by overlaying location or context-sensitive virtual information (e.g., text, images, videos, animations with sound, etc.) onto elements of the physical environment [6]. AR incorporates a broad continuum of computer-generated sensory input (e.g., video, graphics, sound, GPS data) to project virtual content onto users’ perceptions of the real world. It has three fundamental characteristics [7]: (i) combination of real-world and virtual elements; (ii) interaction in real time; (iii) registration in three-dimensional space (i.e., 3D virtual elements intrinsically tied to real-world loci and orientation).

AR has gained a growing interest among researchers during the past few years, especially in the field of education [8,9,10,11,12]. In particular, AR books, which combine physical books with the interactive potentials provided by digital media, constitute a playful and engaging way for enhancing teaching and learning. Although the amount of available research concerning the integration of AR books into teaching and learning is still relatively small due to the novelty of these technologies, the majority of existing studies overwhelmingly point towards numerous positive attributes that have the potential to enhance both formal and informal student learning. The results of these studies demonstrate that the seamless interconnection of the virtual and the real world offered by AR books makes the learning process more relevant and enjoyable for the majority of students, including learners with diverse educational needs. This, in turn, helps to increase students’ motivation and engagement in learning, and to improve their story comprehension performance [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

Exploiting important affordances of AR environments such as realism, immersion, and situational awareness, has been found to improve students’ conceptual understanding [21]. By enabling users to manipulate virtual objects while, at the same time, interacting with real-world surroundings, AR books promote authentic learning and ‘learning by doing’, utilizing visualisations to make abstract concepts more tangible and concrete [22]. AR also focuses students’ attention on the learning process [23], providing opportunities for more authentic and situated learning [24,25], which can be useful for helping students develop contextual awareness [26].

The existing literature also suggests that the affordances provided through the wide range of modalities offered by AR books favor the principles of universal design for learning in relation to multiple means of representation, of action, and of engaging all learners in the educational process [27]. AR books can support all learners (including those with reading difficulties, emotional and behavioural difficulties, low motivation, etc.) as the integration of multiple modalities allows students to learn based on their preferred learning style [9]. Moreover, engagement with AR books and other relevant AR-supported learning activities (e.g., digital storytelling, animation making, game development), can reinforce important 21st century skills, such as communication, interpersonal and social skills, problem solving, creativity, and innovation.

The EU-funded Erasmus +/KA2 project The Living Book—Augmenting Reading for Life project (September 2016–August 2019) was proposed in an attempt to exploit the affordances of AR and other emerging technologies in order to address the underachievement of European students aged 9–15 in reading skills. The project consortium was comprised of nine partner organizations originating from six different EU countries (Cyprus, Estonia, Italy, Romania, Portugal, UK). In most of the partner countries, the proportion of low achievers in reading is still dramatically high (European Commission, 2019): Cyprus (43.7%), Romania (40.8%), Italy (23.3%), Portugal (20.2%). Groups with low performance tend to be students from socioeconomically disadvantaged families, with less well-educated parents, and with immigrant backgrounds. The project’s overall aim was to increase these young people’s motivation to read, while at the same time also boosting a cluster of other key and transversal competencies in students (e.g., digital skills, learning to learn, critical thinking, cooperative skills). Living Book aspired to achieve this through the development of a novel pedagogical approach that combines offline activities promoting reading literacy with online experiences of ‘virtual augmentation’ of a book and with social dynamics.

The Living Book consortium has reached out to European teachers to inform them about AR and other technological developments that could be utilized in schools to augment students’ reading experience with rich media content. A main output of the project is the “Augmented Teacher” professional development course, which targets in-service teachers of upper primary and lower secondary school (ages 9–15). Through a combination of open educational resources (OER) and involvement in professional learning activities, the course aims at strengthening the profile and competences of European teachers in effectively integrating the Living Book approach into their classroom activities. In parallel, the project has developed the “Augmented Parent-Trainer” course, which provides training to teachers in how to involve parents, and particularly those from disadvantaged and/or migrant backgrounds, in proreading activities to back the overall Living Book strategy at home. A Living Library (http://thelivinglibrary.eu/) has supported the project activities by offering students, parents, and teachers with online tools to augment the reading experience with rich media content. The Living Library also hosts a social community of “augmented teachers” and a social community of young “augmented readers”.

This article provides an overview of the Living Book project. It first gives a synopsis of the key activities and outputs of the project. Next, it describes the design of the Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer courses. It then reports on the main experiences gained from the pilot testing and follow-up classroom experimentation process that took place in four of the partner countries (Cyprus, Estonia, Portugal, Romania) in order to evaluate the level of success of the professional development program. The article concludes with some implications for teaching and for future research.

2. Overview of Living Book Activities and Outputs

In the three-year timeframe of the Living Book program, the following activities took place in order to achieve the project objectives:

2.1. Development of Living Book Methodological Guidelines

At the outset of the project, the consortium developed an e-publication providing teachers (and other relevant stakeholders) with theoretical and methodological guidelines to implement the Living Book approach. The guidelines offer the methodological framework for increasing pupils’ reading skills and motivation to read, and for making an appropriate use of ICT and new digital technologies for this purpose. In particular, they describe The Living Book approach, which combines unplugged activities promoting reading literacy with experiences of “virtual augmentation” of a book and strengthening of digital skills, and with social dynamics leading to the creation of European communities of young augmented readers. To foster young people’s motivation to read, the guidelines also suggest integrative activities for students with disadvantaged and migrant backgrounds who need to be motivated to read as a vehicle for integration, inclusion, and prevention of early school leaving. They also suggest the methodological approach and strategies to support reading at home. Moreover, the guidelines comprise a framework and appropriate tools for identifying and assessing the competences of the augmented reader. The e-publication containing the guidelines is freely available for European teachers and downloadable on any device (https://thelivingbook.eu/).

2.2. Development of Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer Course Content

Based on the Living Book Methodological Guidelines, the consortium next designed and developed a line of research-based curricular and instructional materials aimed at strengthening the profile and competences of teachers from primary and upper lower secondary schools (ages 9–15) in effectively integrating the Living Book approach into their classroom activities. They also designed the content for a blended training course—targeting teachers and other educators involved in parent training activities—on how to promote parental involvement in proreading activities. The Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer courses were jointly designed by a multinational consortium of educators, representatives of teachers’ organizations, experienced distance learning instructors, authors of technology-supported courses, and technicians, in order to ensure consideration of all different perspectives into their design. Material for both courses was developed in English and then translated into the partners’ national languages (Estonian, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian). It was culturally differentiated to accommodate local conditions in each participating country.

Before the implementation of the two courses, project staff of participating organizations attended a five-day joint staff training event, held in Cyprus in February 2018. The aim of the event was to assure an adequate level of knowledge and competences on the side of the partners’ staff to manage the testing phase of the ‘Augmented Teacher’ and ‘Augmented Parent-Trainer’ programs. The outcome of the joint staff training event was a pool of teachers and teacher educators, who then became “trainers of trainers” in their respective territories.

Given that the Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer courses are a main output of the Living Book project, Section 3 of this article is devoted to the description of the courses’ design.

2.3. Design and Development of Living Library Infrastructure and Services

In parallel to the development of the ‘Augmented Teacher’ and ‘Augmented Parent-Trainer’ course content, partners also jointly worked on the technical design and implementation of the infrastructure and services of the Living Library, which supports the project activities and outputs by offering open access to the professional development courses’ content, and to various other links and resources. The Living Library has been implemented as an interactive multilingual web portal, which includes space for discussions, chat rooms, and application sharing between European teachers and students (see https://thelivinglibrary.eu/). A series of OER toolkits (downloadable guides, videos, links to tools) have been integrated in this multilingual platform, and have been used by students and teachers to curate and create content. The Living Library also hosts a social community of augmented teachers and a social community of young augmented readers.

2.4. National Hands-On Sectorial Dissemination Seminars (March 2018–July 2018)

During spring and early summer of 2018, six sectorial dissemination seminars (multiplier events) were organized in parallel in all partner countries for professionals working in the school sector. These seminars aimed to (i) engage a sizable number of educators and school staff professionals in accessing the project’s opportunities; (ii) present the main outputs and the methodology; and (iiii) ensure products developed were seen and accessed by as many teachers/educators and learners as possible. The seminar in each partner country made use of interactive methodologies to engage the audience with The Living Book approach, and offered mini workshops on AR-based and hands-on activities with The Living Book instructional tools and the Living Library platform (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Teachers participating in an augmented reality (AR) workshop during the sectorial dissemination seminars in Estonia and Portugal; (a) Dissemination seminar in Estonia; (b) Dissemination seminar in Portugal.

2.5. Pilot Testing of Blended Training Courses for Augmented Teachers and Augmented Parent-Trainers (April 2018–December 2018)

Following the joint staff training event, a pilot testing of the Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer programs then took place in four partner countries (Cyprus, Estonia, Romania, and Portugal). Teacher trainers trained through the joint staff training event pilot tested the blended course for augmented teachers, as well as the related blended training course for augmented parent-trainers. The teacher groups from each country participating in pilot testing were representative of the project target audience. All groups consisted of both novice and experienced primary and secondary school teachers of different disciplines, not only of humanities/literature. The groups were carefully selected to include both technologically literate and less literate teachers, in order to ensure that the project results would be directly applicable to the target audience and would be tested in realistic settings. The pilot testing started in spring 2018 with a series of hands-on professional development seminars, and was completed in fall 2018—all these are described in more details in the rest of the paper.

2.6. Follow-Up Teaching Experimentation (September 2018–May 2019)

In order to evaluate the applicability and success of the training modules, teachers participating in the Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer courses subsequently undertook a teaching experiment during the 2018–2019 school year, where they activated Living Book didactical paths. They customized and expanded upon the lesson plans and learning materials provided to them, and applied them in their own classrooms. Local partners acted as mentors, providing their support to teachers using online communication tools. During the pilot teaching experimentation, teachers also included activities targeting parents (e.g., parent training workshops, family nights, etc.).

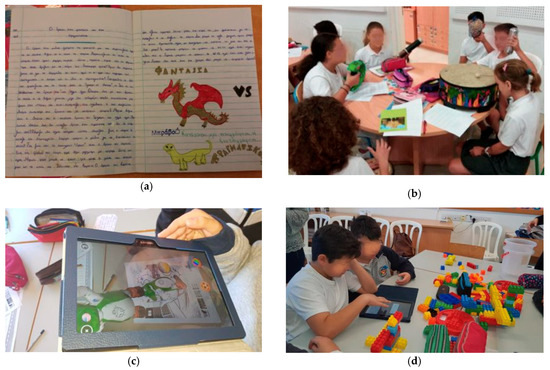

Once the pilot teaching experiment was completed, teachers wrote up their experiences, including a critical analysis of their work and that resulting from their students. This helped them to reflect on their practice and apply self-criticism constructively. They also reported on their experiences to the other teachers, and provided videotaped teaching episodes and samples of their students’ work for group reflection and evaluation. Figure 2, for example, shows samples of student work shared by a group of primary teachers from the partner school in Cyprus, who reported on a teaching intervention they had jointly designed based on the augmented reading approach and had implemented in a Grade 6 classroom (ages 11–12). In this intervention, which took the form of an interdisciplinary scenario (“Ice Dragon”) implemented in different subjects (literature, music, art, theatrical studies), students worked in groups to write a narrative that would continue the story of a novel (“Ice Dragon”, George R. R. Martin), and then used a variety of AR and other digital tools (HP Reveal, Quiver, QR Codes, MSQRD, etc.) to augment their story with video and audio.

Figure 2.

Students working in groups to implement the “Ice Dragon” interdisciplinary project; (a) Wriiting the narrative of the story and using the Green Screen Video app to record it; (b) Adding audio images to the text using a variety of musical instruments; (c) Using Quiver to enliven the “Ice Dragon” story; (d) Using various apps to further augment the story.

2.7. Student Exchanges (November 2018–December 2018)

In partner schools, the teaching experimentation stage was enriched with four short exchanges of groups of pupils and teachers among the involved schools: Vaslui, Romania (October–November, 2018), Nicosia, Cyprus (January 2019), Villa Nova di Paiva, Portugal (March 2019), and Tartu, Estonia (May 2019). The exchanges were structurally embedded in the pilot experimentation and an integral part of the Living Book paths students carried out in their schools.

These mobility activities were important to foster the creation of an EU community of augmented readers. The exchanges aimed to deepen the cooperation among involved schools and to provide pupils with an engaging exchange revolving around reading and augmented reading.

2.8. Cross-Sectoral Dissemination Events (June 2019)

At the end of the program, national events were organized in all territories to reach the wider community, even outside the school sector. These cross-sectorial dissemination events aimed at: (i) promoting the Living Book approach and the project’s outputs; (ii) transferring the Living Book approach to other sectors, thus expanding the opportunities for students to develop reading skills and engagement in reading in nonformal educational contexts; (iii) improving the cultural offer at local level and the integration of ICTs in the cultural sector; (iv) stimulating the driving and coordination role of public authorities in supporting the definition of innovative educational activities packages, intercepting the new schools’ needs; and (v) drawing the attention of the public on the importance of reading and proposing innovative ways to rediscover the pleasure of reading.

3. Design of Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer Courses

The main outputs of the Living Book project are the Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer professional development courses, which target in-service teachers of upper primary and lower secondary school (ages 9–15). We next outline the two courses’ content and structure. For a detailed description of Living Book’s theoretical premises and of the pedagogical and didactical approach underlying the design of the courses, the interested reader can refer to [8,28].

3.1. Augmented Teacher Course Content and Structure

Taking into account best practices in literacy education, adult education, teacher education, and blended learning, the Augmented Teacher course aims to enrich European upper elementary and middle school children’s (aged 9–15) experiences in reading through developing their teachers’ knowledge and skills in teaching using the Living Book approach. The course is made of the following eight modules delivered using a blended learning method:

- Module 1: The Living Book approach—why it is important to motivate reading and to augment books. The learning outcomes (in person).

- Module 2: Pedagogical basis to teach to read (in person).

- Module 3: Motivating disengaged pupils from groups at risk (in person).

- Module 4: Using the Living Library platform and exploring the tools available (video classes).

- Module 5: How to apply the Living Book approach in the classroom and how to match it into the curriculum (in person).

- Module 6: Assessing the reading skills and the competence of the augmented reader (in person).

- Module 7: Preparing for, conducting, and reflecting on the teaching experimentation (guided-field practice).

- Module 8: Practical course tasks, self-assessment of learning outcomes, and self-generation of the Augmented Teacher Certificate (interactive resource).

The Augmented Teacher course was designed to promote teaching to read as a transversal skill for all educators regardless of discipline. Teachers taking the course get familiarized with ways in which the Living Book methodology can help foster students’ motivation towards reading and improve their reading skills, while at the same time strengthening the development of a cluster of other key and transversal competencies (digital skills, learning to learn, critical thinking, cooperative and collaborative skills, etc.). Special focus is given to ways of increasing the level of participation and achievement of the most unmotivated learners from disadvantaged backgrounds. Central to the course design is the functional integration of technology with existing core curricular ideas, and specifically, the integration of AR and other technology-enhanced tools and resources provided by the Living Library platform.

The course is delivered using a blended learning method. At the beginning of the course, teachers in each country gather together to attend a series of face-to-face seminars familiarizing them with the project philosophy, objectives, and resources. Teachers are introduced to the objectives and pedagogical framework underlying the courses, and are familiarized with the technological tools and facilities offered by the Living Library. The remainder of the course is delivered online using the instructional content and services of the Living Library, and of the course dedicated platforms for teaching, support, and coordination purposes. The sites offer access to resources for professional learning (e.g., pedagogical framework, instructional content, lesson plans, etc.), as well as collaboration tools for professional dialogue and support (e.g., forums, wikis, chats).

3.2. Augmented Parent-Trainer Course Content

In an effort to create home environments that foster learners’ development and are coordinated with classroom work, teachers taking the Augmented Teacher training course, in parallel take a blended training course for parental engagement. Adult educators and other professionals involved in parent training are also be invited to participate in the course. The Augmented Parent-Trainer course is made up of five modules:

- Module 1: Living Book approach, why it is important for parents to motivate their children to read and to augment books; the learning outcomes (in presence).

- Module 2: Basic principles of parent education; recommended practices for promoting parental engagement and learning (e.g., family nights, family involvement case studies, etc.); reaching to disengaged parents from groups at risk (in presence).

- Module 3: The parent training pack (in presence).

- Module 4: Using the Living Library platform and exploring the tools available (video classes).

- Module 5: Practical course task, self-assessment of learning outcomes, and self-generation of the Parent Trainer Certificate (interactive resource).

The Augmented Parent-Trainer course aims at equipping parent educators with the required knowledge, skills, and resources to provide professional guidance to parents of elementary and middle school students (ages 9–15) in how to best support children’s development in reading through the adoption of the Living Book approach. Course participants get familiarized with innovative methodologies they can utilize to build parents’ capacity in raising children’s motivation and achievement in reading and in other key and transversal competencies (e.g., digital skills, critical thinking). They are also introduced to the objectives of a parent training pack developed by the consortium, and to the pedagogical framework underlying its development. Special focus is again being put on ways to increase the level of participation and achievement of learners originating from socially and economically excluded families.

The parent-trainer course is also delivered using a blended learning method. The course platform offers access to various tools and resources for professional dialogue and learning (e.g., pedagogical framework, instructional content, collaboration tools).

4. Methodology

4.1. Context and Participants

A total of 141 teachers participated in the pilot testing of the Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer courses that took place in four partner countries: Cyprus (n = 79), Estonia (n = 15), Portugal (n = 27), and Romania (n = 20). As already explained, the two courses were offered in parallel to the participating teachers in each country.

In Cyprus, local partners offered three rounds of the professional development due to an extremely high interest among the teaching community for participation in the Living Book program. In each round, a blended learning approach was used, which combined face-to-face meetings (5 meetings in total X 3 h per meeting) and use of the courses’ Moodle platforms. Professional development activities and teaching interventions in the other partner countries also followed a blended approach, adjusted based on each school partner’s needs and local specificities.

As already described earlier, to evaluate the applicability and success of the training modules, teachers from partner schools who completed the Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer courses subsequently undertook a teaching experiment. They customized and expanded upon lesson plans and other instructional materials provided by the consortium, and applied the Living Book augmented reading approach in their classrooms with the support of the local project team members.

During the pilot teaching experimentation, partner schools also organized activities targeting parents (e.g., parent training workshops, family nights, etc.). The experimentation was enriched with four (4) short-term exchanges of groups of pupils and teachers among the schools involved in the project.

Table 1 provides information regarding each of the four short-term exchanges of students that took place during the final year of the project (location, date, and number of participants).

Table 1.

Short-term exchanges of groups of students.

4.2. Instruments, Data Collection, and Analysis Procedures

The success of the Living Book program in increasing teachers’ level of competence in dealing effectively with reading difficulties and in cultivating young students’ motivation to read, while at the same time building other transversal competences (e.g., digital competences, learn to learn, teamwork, and cooperation), was evaluated using Guskey’s 5-level hierarchical model [29]. According to Guskey [29], professional development evaluation should move from the simple (reactions of participants), to the more complex (student learning outcomes), with data from each level building on the previous. Based on Guskey’s model, evaluation occurred at five levels, employing a variety of both qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques to gather information from teachers and their learners, as well as from parents, including the following: pre- and postsurveys, interviews, focus groups, postings in discussion forums, portfolios, classroom observations, videotaping of classroom activities, and student work samples.

The analysis of some of the multiple sources of data obtained during the pilot testing and follow-up classroom experimentation informed the revision of the professional development courses, and of the accompanying methodological and pedagogical frameworks and instructional materials and services included in the Living Library. However, given that the amount of data collected throughout the program duration was huge and overwhelming, the analysis of obtained qualitative data is still ongoing.

In the current study, we restricted our analysis to mainly the following sources of data:

- (i)

- A postsurvey administered to teachers upon completion of the pilot-testing of the professional development programs, in order to evaluate the impact of the training on participants’ attitudes, confidence level, and self-reported proficiency in adopting the Living Book approach in their teaching practices.

- (ii)

- A postsurvey administered to students in the partner schools at the end of the program to investigate their reading habits and their attitudes towards reading and towards the Living Book experience.

- (iii)

- A postsurvey completed by students who participated in short-term student exchanges.

- (iv)

- Questionnaires/activity reports completed by each school partner organization providing information about the main activities that took place in their school and community (i.e., pilot testing of professional development courses, follow-up classroom experimentation, participation in/ hosting of short-term student exchanges, organization of multiplier events).

Table 2 summarizes the different means of data collection employed in the current study, and indicates the number of participants in each case:

Table 2.

Data collection methods employed in study.

Most of the questions included in each postsurvey were closed-ended, requesting Likert-type ratings or multiple-choice responses. A few open-ended questions requiring text-based responses were also included to obtain more comprehensive information. The questionnaires were finalised after being pilot tested and were administered in electronic format. They were posted via Google Forms, and each took about 15–20 min to complete. Invitation messages explaining the purpose of the study, and providing a link to the postsurveys, were sent via email to participants. Teachers’ participation was voluntary and anonymous. No identifying information was collected from participants. Children’s participation in the postsurveys (as well as in any other form of data collected during the study) was also voluntary and anonymous, and it took place only under their parents’ written consent.

Quantitative data obtained from the postsurveys were analysed using descriptive statistics. The text-based responses were coded and clustered as themes. An interpretive case study approach was employed for the analysis of these data. We did not use an analytical framework with predetermined categories to assess how teachers’ perceptions and professional knowledge developed after going through the program. What we attempted instead was to produce a holistic understanding of the research situation through considering practitioners’ and learners’ own views and reflections on the model of professional development adopted by Living Book, and on how this model was transferred into teaching practice and, in turn, might have influenced students’ motivation and learning.

5. Results

In this section, we share the main insights gained from the pilot testing of the Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer courses, and the follow-up classroom experimentation in the project partner countries.

5.1. Pilot Testing of Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer Courses

Face-to-face professional development seminars focused on analysis and discussions of the research component of the project, the theoretical and pedagogical foundations of the Living Book approach, and the development digital skills for the use of specific tools, through hands on activities. Some examples of the main emphases of the face-to-face training are presented here:

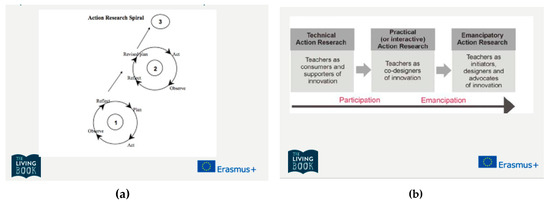

Augmented teachers as action researchers: Following the presentation of the aims and background of the program, participants were invited to reflect on their role as action researchers (see Figure 3). This was considered essential, both for their own participation in the study and for the implementation of the Living Book approach, as an agent for making a change to their educational practices and their students’ learning experiences. For the purposes of the project and the work presented in the paper, it was anticipated that participants should have been acquainted with the methodological and ethical issues regarding their engagement as reflective practitioners.

Figure 3.

The Living Book approach for action research, an example from Cyprus: Teachers’ familiarization with the action research spiral, and with different models of action research; (a) Action research spiral (Zuber &Skerrit, 2001); (b) Three models of action research (Masters, 1995).

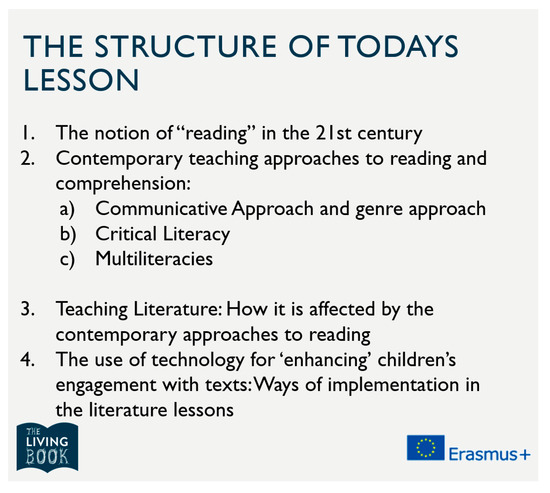

Literature and augmented reading: Participants were also introduced to the literacy theories on which the Living Book approach is premised. They compared different approaches to reading and their implications for students, and were asked to reflect on their classroom practices and on what ‘reading’ means to them and how its meaning can change in varied social, cultural, religious, and other contexts, and in different periods of time. After covering the basic theoretical principles, teachers were introduced to different online tools and discussed possible ways of using them in literary lessons (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Module 2 of the Augmented Teacher course—Living Book’s approach to literature.

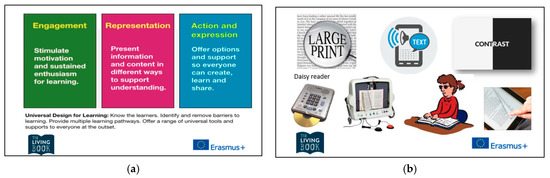

Augmented reading for all: As the project aimed at supporting teachers mainly to engage diversified groups of learners, and particularly pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds, a major part of the face-to-face training was devoted to discussions around inclusive education, accessibility, and universal design for learning (see Figure 5). Hence, the role of technology in overcoming barriers and providing options for accessibility was elaborated. Participants experimented with relevant applications and activities, and exchanged ideas on possible scenarios for inclusive education through the Living Book approach.

Figure 5.

Principles of the Universal Design for Learning and the role of technology in promoting access and accessibility; (a) Principles of Universal Design for Learning (b) Access, accessiblity, and the role of technology.

Hands-on activities with tools: After discussing the potential usefulness of different tools and before classroom experimentation, participating teachers were given the chance to become familiar with various technology tools, which they could potentially integrate for AR and other technology enhanced activities during the design and implementation of their lesson plans (see Figure 6). These included a variety of digital tools, such as QR Code, Story Jumper, PicCollage, Book Creator, StoryBoard That, Padlet, Popplet, some of which participants had the opportunity to explore in face-to-face meetings. Nevertheless, the focus was on AR apps, such as Zapworks and Aurasma (HP Reveal), that attracted most interest and attention, and were less familiar to participants.

Figure 6.

Examples of tools participants were familiarized with during the training; (a) List of useful technological tools introduced to teachers (b) More tools introduced to teachers.

At the end of the face-to-face seminars, participating teachers were invited to complete an online postsurvey in order for the consortium to evaluate their experience. A total of fifty-seven (n = 57) teachers (53 females, 4 males) responded to the invitation. Two-thirds (n = 38) were primary school teachers. The rest were secondary school teachers from diverse disciplines (e.g., language, mathematics, ICT, history, biology, geography, physics, chemistry, arts). The majority (65%) were older than 40 (54% aged 41–50, 11% aged 51–60). Only three respondents were younger than 30. Most were very experienced educators (35% 11–20 years, 44% more than 20 years of teaching experience). Two-thirds had a Master’s degree (n = 36, 63%), while two participants also held a doctorate.

Participants first indicated, using a 5-point Likert Scale (1 = strongly disagree….5 = strongly agree), their level of agreement with a number of statements regarding the seminars (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage that agreed or strongly agreed with each statement concerning the seminars.

As seen in Table 3, which shows the percentage of teachers who agreed or strongly agreed with each statement, all aspects of the professional development seminars received very high ratings by participants. When prompted to indicate what they particularly liked, almost everyone pointed out the program’s innovation/originality and how it helped them to explore ways to promote children’s love for reading through familiarization with highly motivating, technology-enhanced instructional methods. They also noted that they appreciated the program’s focus on differentiation of instruction and on accessibility.

The aspect of the seminars teachers seemed to have liked the most were the “practical application of the tools and apps presented during the seminar”, which they found to be “very useful for the classroom”. They appreciated the hands-on nature of the seminars, which gave them the opportunity to be familiarized with new, innovative augmented reality and other innovative technological tools (e.g., QR Codes, text creation tools, comic creation tools, digital games) and with ways in which these could be exploited to enhance students’ reading experiences.

Participants also pointed out that the program promoted cooperation and exchange of experiences with other teachers and schools in their country and abroad. They expressed an appreciation for the fact that a big part of the seminars were led by teachers (from the local schools participating in the project consortium) that had already tried out the Living Book approach in their classrooms, and had “good practice examples” and useful tips to share.

Almost all participants also expressed very high levels of satisfaction with both the technical and pedagogical features, as well as the tools and resources of the online platforms of the Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer courses and the project Living Library.

Respondents were asked to evaluate the extent to which the Living Book professional program met their expectations. Ninety-one percent (n = 52) indicated it did to a high or very high degree, and that they were very or extremely satisfied with the topics developed in the workshops, but also with the instructional materials/equipment used.

Respondents also specified the degree to which the different types of tasks, materials, and resources included in the online learning environments had contributed to their professional development in the context of the Living Book program. Almost everyone (91%) rated the contribution of suggested activities as very important, while a very high percentage also rated as important the contribution of the videos (84%), educational material in text form (86%), and suggested readings (74%) included in the course platforms and the Living Library.

When prompted to rate their overall level of readiness to integrate AR and other contemporary technologies (e.g., mobile devices, mixed reality, QR codes, etc.) in their instruction after participating in the seminars, 70 percent stated that they now felt “well” or “very well” prepared to do so, while the rest felt prepared “to a certain extent”. Teachers who did not feel sufficiently prepared noted the need for more hands-on practice with the educational apps and tools introduced during the training and for familiarization with additional tools. They would also like more examples of how to integrate emerging technologies in instruction, and would appreciate opportunities for collaborating with other educators in order to codesign educational activities based on the augmented reading approach.

Fifty-two of the participating teachers (91%) reported having used some of the AR technological tools introduced during the seminars (e.g., Quiver, HP Reveal, StoryJumper), either for personal use and/or for teaching purposes. The experiences of the teachers who had introduced AR tools in their classrooms were generally very positive:

“I have taught the Little Prince using Augmented Reality. Children got really excited and the lesson was very effective”,

“I have tried AR apps with my students and though some time was needed to learn how to use them, the results were very interesting and the students got very excited!”

The rest of the teachers stated that although they had not yet tried out AR tools in their classrooms, they did plan to exploit AR technologies in order to implement the augmented reading approach in various subjects (e.g., language, literature, arts, STEM/STEAM education, design and technology, computer science, social studies, etc.).

Teachers’ strongest incentive behind their intention to adopt the Living Book approach was to “build students’ motivation and get them engaged in reading activities” by exploiting technology to “make the learning process more interesting and more up-to-date”. They argued that the “mix between traditional and modern methods” can attract students’ attention, and get them interested in books: “Using the new technologies, students will be more motivated to read, because they are already acquainted with ICT”; “My long term objective is for children to get to love books”; “My objectives would be to utilize the Living Book platform so that children can get exposed to more books, through a different approach with the use of technology”. Teachers were expecting that through exposure to augmented reading and thus “to multiple ways/means of creative expression”, students would not only “be provided with a more motivating learning environment that would promote their reading habits”, but they would also gain several other educational benefits:

- Better comprehension of concepts and ideas;

- Enhancement of oral and written communication skills;

- Promotion of creativity (“students as creators of knowledge”), development of inquiry and problem-solving skills, and of critical thinking;

- Promotion of collaborative skills;

- Promotion of digital literacy.

When prompted to indicate challenges they expected to face when attempting to introduce the Living Book approach in their classes, teachers cited various factors as obstacles to technology integration: limitations in the availability of PCs, laptops, and tablets (at school and at home for some of the students); limited resources; limited time; technical issues (e.g., lack of internet connection, internet connection going down at times); lack of technical support; lack of support regarding ways to integrate technology into the curriculum; an oversized curriculum; shortage of suitable software; and lack of knowledge about suitable software. The need for additional training on the use of AR and other digital tools was particularly emphasized by the participants. Several of them also stressed that it is very challenging and time consuming “to manage converting all the ideas into digital augmented material”. Some also expressed the concern that they “might not develop adequate digital skills to keep up with students”.

In a question asking them to specify the profile of students that they believed would most benefit from the implementation of the augmented reading approach, the majority (32 teachers) argued that it would benefit everyone as “technology appeals to every child”. These teachers made comments such as the following: “All students since student participation and successful learning requires student motivation. Living book promotes student motivation to the highest possible level”; “Living Book helps to increase everyone’s motivation and maybe their love for books”. They stressed that the Living Book approach “can be easily adjusted to the skills, abilities, and needs of every child” and, thus, “promotes inclusion” by benefiting “all students in diverse ways”, “each for a different reason and in a different way”. Some teachers, however, believed that the Living Book approach is particularly beneficial for “students who face learning difficulties”, “students that have low motivation for learning”, and “students that need visual stimuli”. These educators made statements such as the following: “Students who are not interested in paper books, are more willing to learn using digital technology”; “I strongly believe that less motivated students who find it quite difficult to read and create traditional pencil and paper work on written material, would find it easier to be actively involved and select the tasks they like with the use of new technologies”; “Students belonging to groups at risk and with learning difficulties will find lessons adopting the Living Book approach more attractive and motivating”. Still others argued that it is students with good digital skills that will benefit the most: “It will be particularly beneficial for the students who are fond of technology. Why? The students who are not good at using technology, are not eager to use new applications”.

When prompted to indicate whether they would recommend to their colleagues to participate in the activities of the Living Book training program, everyone responded positively: “Yes, because the learning outcomes are impressive and children love it”. At the same time, however, some of them stated that they would warn their colleagues that “this entails huge work”, and thus they should be willing to invest a considerable amount of time.

Participants were requested to mention two elements of the Living Book training program that they found particularly positive. What many of them pointed out was that the training was innovative and very well organized. They particularly liked the “blended approach” of the program, and its focus on “practical training on digital tools”. Τhey appreciated the fact that through Living Book they got familiarized with emerging technologies like AR and experimented with “a big variety of innovative tools” that “promote student creativity” and offer “endless possibilities” for enhancing the learning process. They found the applications introduced “attractive and easy to use”.

What several participants considered as a particularly positive aspect of the program was “the augmented reading concept”, and the “mixing of literature and technology”. They pointed out that “the concept of augmented reading can be implemented in almost all school subjects, involving also students with special needs”. Respondents also praised the fact that the program provided many practical examples of application of the augmented reading approach in real classrooms:

“I liked the hands-on activities and the examples given by teachers after trying them out in class with their students”;

“We were given clear and practical suggestions by other teaching practitioners on how to get started implementing the augmented reading approach”.

Participants also liked the “exchange of ideas, lesson plans, and resources” among teachers “of different disciplines, schools, or even countries”. The discussions and exchange of experiences with teachers from other partner countries, in particular, was something pointed out by several teaches who noted that Living Book gave them, but also their students, the opportunity to get acquainted with “different cultures and school systems”, and to “reflect about different experiences in different countries,”

Additionally, many of the participants considered the parallel offering of the Augmented Teacher and Augmented Parent-Trainer trainings as a particularly positive aspect of the program, noting that the promotion of proreading activities not only at school but also at home is essential to the successful implementation of the Living Book approach. They valued the program’s focus on involving parents from disadvantaged backgrounds, and considered the methodologies they were familiarized with as “effective and practical strategies” that can help promote parental engagement so as to “support children’s literacy both in the classroom and at home.”

Teachers were also requested to refer to aspects of the Living Book training program that they considered negative. What was pointed out by many teachers was that the professional development program was too demanding: “The project was really time consuming, the teacher’s workload was very big, it was too much for a teacher who works full-time”. Several teachers found their participation in the program to be “too time consuming” and “a bit overwhelming”. Some teachers noted that there was “too much reading – a lot of theoretical material”, while others noted that it took “a lot of working at home in order to prepare a lesson plan”. They also pointed out that they got acquainted with “too many tools in a short period of time”, and argued that “some extra time was needed for some tools requiring more technological skills and knowledge, like HP Reveal”.

What numerous teachers stressed was that the successful implementation of the Living Book approach is highly dependent upon schools having the necessary infrastructure, and that this is not the case for many of the schools. Finally, a small number of teachers noted that the program “requires relatively high levels of digital competencies”. A few others noted the need for “high levels of language skills”, and for a good command of English to be able to interact in the discussion forums and other social media offered by the Living Library.

Finally, teachers provided some suggestions for further improvement of the Living Book Training Program. Some teachers noted that they would suggest “less time being devoted to theory” and more time “dedicated to the exploitation of digital tools”. Several other teachers, however, liked the “blend of theory and practical training offered by the course”, and suggested increasing the duration of the seminars to give teachers more time “for training on the tools and the Living Library”. Another suggestion was for schools, rather than individual teachers, to participate in the program so that teachers would collaborate with other educators in their school when designing and implementing instructional activities based on the Living Book approach. Finally, they recommended putting “even more emphasis on the use of the platform and the way teachers and student could meet, exchange ideas and material”. Concerning the parent training course, they suggested that in future offerings, “more time should be dedicated to the many practical activities on parental engagement”, and particularly “on how to actively engage parents with low learning, reading, and literacy skills, to which one can add the lack of digital capabilities”.

5.2. Follow-Up Classroom Experimentation

5.2.1. Student Postsurvey

As explained in the Methodology section, a student postsurvey was administered at the end of the pilot teaching experimentation in order to help the consortium understand how children felt towards reading and towards the Living Book experience. Specifically, students in the partner schools were invited to participate in an online survey administered during month 34 of the project (June 2019). This was an anonymous online survey that children could complete at home on a voluntary basis. One hundred students (42 girls and 58 boys) completed the survey. The vast majority (50 children) were aged 11–12, but there were also some older children (14–15 years old).

Two-thirds of the children (64%) reported spending on average, at most 2 h per week reading books (10% 0 h per week, 34% 1 h per week, 20% 2 h per week).

Table 4 indicates the percentage of children who agreed or strongly agreed with a number of statements regarding the reasons behind reading a book.

Table 4.

Percentage of students that agreed or strongly agreed with each statement regarding the reasons why they read books.

Around 60 percent of the children reported reading books because they like them, and a slightly lower percentage because books please them, and/or because books relax them. Other reasons several children gave for reading books included the following:

- “Books help to enrich my vocabulary and to improve my spelling”;

- “They help me to write better essays”;

- “Books offer me knowledge”;

- “I read books because I like to learn new things”;

- “Books cultivate my imagination and creativity”;

- “Books are adventurous”;

- “I can use my imagination to paint a picture described in a book in my head”;

- “Books help me improve my concentration”.

One student noted: “I want to be a surgeon when I grow up and I’ve heard that this requires lots and lots of reading”. A couple of other children wrote that they read either because they “want to be good students” or because “[their] parents force [them] to read because they think this is good for [them]”.

While reading seemed to be a joyous activity for more than half of the participants, responses to the survey indicate that a sizeable proportion of the children disliked reading. As shown in Table 5, around one-fifth of the respondents indicated that they do not read book because books make them tired (21%) and bore them (21%). Around two-fifths noted that they would rather play electronic games (41%) or play outside (37%) rather than reading a book. Many children (23%) stated that they do not read books due to lack of time. Several children indicated other activities that they prefer to do rather than playing games (e.g., jogging, playing football or watching a football game, watching TV, meeting with friends, etc.). A couple of students stated that “books are too big”, or that they “rarely find books [they] like”.

Table 5.

Percentage of students that agreed or strongly agreed with each statement.

More than two-thirds of the students indicated that they rarely or never visit a bookstore (68%) and/or a library (73%).

When prompted about their impressions regarding the Living Book project, two-thirds of the children (64%) noted that they liked the project. What is interesting is that this percentage was higher (74%) for children who had indicated spending at most 2 h per week reading books. Similarly, 75 percent of the children that had stated that they do not read books because they find them boring, indicated that they liked the Living Book approach.

Sixty percent of the children agreed or strongly agreed that their school’s participation in the program gave them the opportunity to learn about books that they would not normally choose on their own. They listed a number of classical novels that they got familiarized with due to the project (e.g., “Around the World in 80 Days”, “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer”), but also more contemporary books they were already familiar with, but which they now got the chance to augment through use of technology (e.g., “Harry Potter”, “The Wonder”, “Captain Underpants”).

In the survey, students also indicated what they considered as the main contribution(s) of the Living Book didactical approach. As shown in Table 6, “get involved with digital tools in a meaningful way” was the choice selected by the highest proportion of respondents (55%), followed by “stimulate imagination through the use of technology” (49%).

Table 6.

Percentage of students that agreed that the Living Book project gave them the opportunity to do each of the following.

A very high proportion of children noted that they now felt confident to use a variety of digital tools (e.g., QR Code, Story Jumper, PicCollage, Book Creator, StoryBoard That, Padlet, Popplet), including AR applications like HP Reveal and Quiver.

In order to assess if the Living Book approach fulfils the purpose of creating a community of augmented readers, students were also asked to indicate whether they agreed with each of the statements shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Percentage of students that agreed with each statement.

Students’ responses suggest that the big majority of the children enjoyed uploading their reading digital material in the Living Library in order to share it with other students, but also exploring the digital material developed by other students. They liked their participation in book discussion groups in the Living Library, and enjoyed meeting (either virtually or physically) with children from other countries.

5.2.2. Short-Term Exchanges of Students

In order to assess the quality of the short-term exchanges of groups of pupils that took place during the final year of the project, the four participating organizations were each asked to fill in a questionnaire/report describing the exchange process, and outlining and evaluating the activities taking place during the exchanges.

Data collected from the school partners confirmed that the profile of the students that participated in the short-term exchanges corresponded to the one specified in the project proposal: aged 9–15 and some from a disadvantaged background. In the selection of participants, each sending school put an effort on selecting not “best students”, but pupils belonging to groups at-risk and showing particular difficulties and general demotivation towards reading. The exchanges served as a vehicle to engage and motivate these students to join and reap the benefits. For this reason, each national team ensured that they included at least one participant belonging to vulnerable groups. As shown in Table 1, to guarantee the highest level of protection and safety of pupils during their travel and stay, teams were also accompanied by teachers. Hosting families were carefully selected among those expressing an interest to host students.

In the weeks preceding the mobility, students and teachers participating in the mobility and involved schools jointly worked on e-twinning to adequately prepare for the exchange. During the mobility, which each lasted for five (5) days, the learning activities included:

- Classroom collaborative and task-oriented activities promoting reading literacy using Living Library and the tools of the platform;

- Workshops for pilot testing at least one didactic unit in international teams of students;

- Activities of peer learning, collaborative learning to develop students’ creativity, critical thinking, and communication in English. These activities revolved around the collaborative draft and animation of a “story” that was uploaded in the Living Library platform as a collaborative story book created by students in mobility;

- Activities of socialization and personal development, helping students to better know each other and create and create links for further online collaboration;

- Cultural visits, visiting other schools and institutions to develop their cultural awareness and expression, learning to learn skills, and understanding of multiculturalism and diversity.

Self-evaluation and moments of discussion among students to assess their learning progress were embedded in the program of the exchanges. Participants reported that, in each short-term exchange, students developed collaborative drafts and animations of a “story” or book, specifically “The Old Estonian Fairy Tales” by Fr. R. Kreutzwald (in Estonia), “The Little Prince” by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (in Portugal), “Wonder” by R. J. Palacio (in Romania), and “Around the World in 80 Days” by Jules Verne (in Cyprus). As an example, we next describe students’ joint work during the exchange in Cyprus.

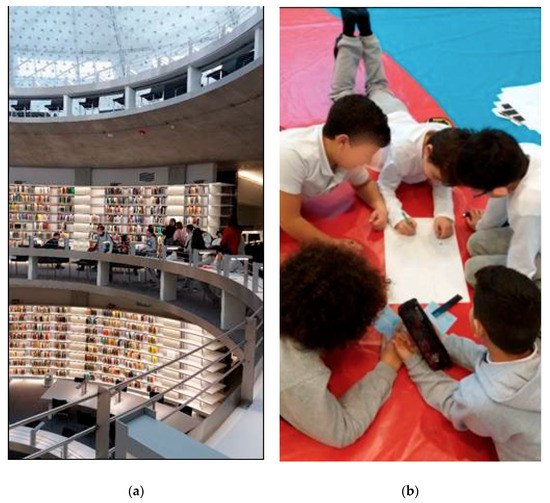

During their stay in Cyprus, students engaged in several activities based upon the “Around the World in 80 Days” book, which they had to read beforehand. Initially they were asked to interact with a hardcopy of the classic novel, and to locate information about Phileas Fogg’s journeys. The Google Tour Builder App was used to map the route of Phileas Fogg on the globe and helped the students realize the “around the world” part using the Google Earth. Cyprus teachers organized a visit and guided tour at the recently inaugurated University of Cyprus Library (http://library.ucy.ac.cy/en/library/steliosjoannou-lrc), officially named as Learning Resource Centre—Library “Stelios Ioannou”, a unique piece of architectural design (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Tour of the University of Cyprus Library and creative student activities during the visit; (a) Tour of the Library (b) Creative activities in the Library.

After the visit—which was conducted in small groups—students were involved in creative activities based upon excerpts from the Jules Verne book. They used mobile devices and applications such as HR Reveal, Book Creator, PicCollage, Video Recording, and online games. Simple greenscreen applications were also creatively used to produce short videos, enliven Phileas Fogg, and create passepartout dialogues. QR codes were inserted in the book leading to these dialogues. Guest students also participated in art lessons where they had to creatively present the means of transport Phileas Fogg used to travel “Around the World in 80 Days”, after having read and discussed certain excerpts from the book in groups. Their work and a short description were later uploaded on a ‘wall’, using the Padlet application. QR codes were used to embed this work and other Kahoot quizzes prepared by the students in the book.

Students, teachers, and parents also participated at the opening ceremony of the Annual Book Exhibition organised by both the Parents’ Association and the school. Activities for students and parents were organised and led by local, well-known writers, based upon literary books.

After each mobility, online collaboration among students continued and further strengthened the learning outcomes. The collaborative story, the draft of which was started during the exchange, was further developed online in the months following the international exchange.

In their reports on the school exchanges, participating schools portrayed a very positive picture for these exchanges. They all highlighted the warm welcoming from the host schools and families, the excellent organization of the exchanges, and the high quality of the learning experiences offered to students during the visits. They unanimously reported that the activities were all carefully selected by the hosting partners to promote the Living Book approach. The activities also facilitated collaborative learning and focused on developing students’ creativity and critical thinking. They included task-oriented hands-on activities stimulating reading literacy using the Living Library, and AR and other technological tools. Students’ level of engagement, communication, and collaboration were very high throughout each mobility.

Participating schools also inquired as to whether communicating in a different language was an issue for students (the language of communication among participants was English). They indicated most students were comfortable communicating in English. Nonetheless, communication in a foreign language proved difficult for a few of the children.

Students participating in the exchanges were also invited to complete a short postsurvey. Nine (n = 9) students accepted to take part. They all expressed their high level of satisfaction with the short exchange experience. They stated that they truly enjoyed participating in collaborative augmented reading activities. Students loved the fact that they explored books using AR and other digital tools and jointly worked with children from other countries to create their own augmented stories. Everyone agreed that the exchange gave them the opportunity to (1) learn about new books, (2) learn about new digital tools, (3) learn about other countries’ cultures, and (4) learn about other languages. Finally, almost everyone (eight out of nine students) also agreed that the experiences they gained before, during, and after the mobility strongly stimulated their long-term interest in reading.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Through cross-national, in-depth postsurveys of teachers and students, the current study aimed to gain insights into these key stakeholders’ perceptions, motivations, and experiences regarding the Living Book approach. A drawback of the study is the limited generalizability of its findings due to the self-selected nature and relative small size of the survey samples. Clearly, the presented results are only suggestive and warrant further study, using more rigorous data collection and analysis procedures. The ongoing qualitative analysis is also expected to provide a more in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences with the Living Book project and approach.

Despite the tentative and nongeneralizable nature of its findings, the conducted research contributes useful insights into the accumulating body of AR-enhanced teaching and learning. In line with relevant literature, the Living Book project and the pilot implementation program highlighted some of the potential benefits, as well some challenges, in relation to the incorporation of AR in education. These are summarized in this section together with some of our own reflections.

First of all, an important component of the Living Book approach is the fact that it combines traditional books and/or traditional teaching approaches with digital tools and creativity, including, but not limited, to AR technologies. This makes it easier for augmented reading to be incorporated in traditional classrooms that may not have the necessary equipment or know-how for using more advanced tools. Still, equipment and more general resources (e.g., internet availability, mobile devices, etc.) appeared to be a very important issue in the successful implementation of the Living Book approach, together with the need for more training, as well as the need for communities of teachers who can continuously support each other. Indeed, school culture and the existence of a supportive community for exchange of ideas, materials, and expertise emerged as important aspect both in the pilot implementation, as well as in the questionnaires.

With regards to AR technologies in particular, our findings concur with the research literature, which indicates that despite the multiple possibilities for augmenting students’ engagement in reading and learning offered by AR, there are several challenges still preventing its mainstream adoption that need to be addressed. These include the following [22]: (i) financial and time constraints, as AR can sometimes be expensive to implement; (ii) technical and/or pedagogical constraints of available AR apps, which might include limited scaffolding of the learning experience, inadequate model quality, poor simulation preciseness, and lack of haptic feedback [30]; (iii) students’ frustration if they find it difficult to use an AR application or if the application is not working appropriately; (iv) students’ distraction from the learning process caused by the virtual information when presented to them for the first time; (v) teachers’ failure to realize the benefits of AR in schools; (vi) teachers’ lack of time and/or interest in getting familiarized with this new technology and in introducing it into the educational process; (vii) limited number of freely available AR authoring tools that are easy for teachers to use; (viii) limited AR educational material available for teachers to use; (ix) teachers’ lack of skills and/or time in creating new learning content incorporating AR; and (x) lack of professional development opportunities and support for teachers.

In relation to the above, and reflecting on the limitations of the implementation of the project, it is noted that some tailoring of the professional development to individual teachers’ and schools’ needs, on-site training, and participants’ support during the experimentation phase need to be enhanced. The majority of the teachers involved came from urban schools or schools that often have more access to resources and training opportunities than smaller, and possibly rural, schools. Though almost all participants cited more or less the same factors as obstacles for technology integration, in practice, those obstacles vary in terms of technology resources availability, teachers’ background skills and experience, educational level, etc. Therefore the variation and the degree of impact these factors may have on different educational levels (i.e., primary and secondary education) and/or on different curriculum subjects should be examined in order to help trainers and teachers tailor the Living Book approach to their own needs, settings, resources, and expectations. Such an approach will also respond to some of the difficulties encountered in the implementation of the study, which were linked to the barrier factors already highlighted by participants. Specifically, during the implementation of the project, participants devoted substantial time, over and above other school activities, to familiarize themselves with the tools and to prepare, design, and develop appropriate educational materials and activities that would have added value for their students. Arguably, teacher training can include targeted tasks and time allowed for teachers to assess and analyze their school and classroom variables in order to maximize effectiveness of the Living Book approach by exploiting existing resources and context.

Another important theme that emerged consistently in teachers’ responses, and which is in accord with the existing research literature [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], is the positive impact of the augmented reading approach on students’ motivation. This was repeatedly mentioned both in the questionnaires and in conversations that we had during the training. According to teachers, the variety of AR and other technological tools, and the different activities implemented in the classroom as part of the project, seemed to motivate students, raising their enthusiasm and interest in the lesson and the books, something that was also reflected in students’ responses. Although the percentages of student satisfaction at a first glance seem smaller than the those of the teachers, still, the majority of students seemed to enjoy the Living Book approach and as shown earlier, and interestingly enough, the percentage was higher for those who did not enjoy traditional reading as much. As teachers implemented the Living Book approach differently based on the available resources in the school and their level of technological expertise, it is difficult to currently assess the students’ results and explain why teachers seemed more enthusiastic than students in questionnaire responses. Once again, the qualitative analysis is expected to shed more light on students’ experiences. Perhaps the fact that teachers had a more substantial involvement in the project may be one explanation, whilst the challenges and obstacles reported by students could also have impacted learners’ experience as they had a more limited exposure to the Living Book approach from the one presented to the teachers in the training program. Indeed, the students who participated more fully, taking part also in the exchanges seemed to report very high levels of satisfaction. We consider this an important issue, as student engagement was from the start a focus of this program. Offering the opportunity for learners to interact with books in multiple ways and not necessarily in the traditional ways was in line with our theoretical commitment to inclusive education and the principles of the universal design for learning—which is something worth discussing further.

Part of the theoretical tools of the Living Book project emerge from the field of inclusive education and the aim to empower teachers in order to engage diversified groups of learners, and particularly pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds. Recent studies [13,31,32] provided evidence that AR activities indeed help learners with reading difficulties and other educational needs to increase their literacy skills and demonstrate better understanding in reading, while at the same time helping improve learners’ motivation towards reading. Nevertheless, [32] identified a number of important challenges that need to be addressed in research on the effectiveness of AR for inclusive education. As the authors highlighted, one of these challenges is the absence of frameworks, models, and methodologies of inclusive education in the various studies. The Living Book project, however, responded to this challenge by bringing together the principles of universal design for learning and accessibility and the frameworks for teachers’ professional development for integrating technology in education. The framework was included in the Living Book Approach Guidelines described above, as well as in the design and implementation of the professional development modules. Nevertheless, reflecting on the limitations of the implementation of the project, it is acknowledged that the research team needed to place further emphasis not only on the theoretical framework of the principles of inclusive education, but also on practical aspects, by (a) including more accessibility tools and practices for building universally designed technology-enhanced activities and (b) supporting teachers to actually develop and implement those in their classroom practice. What is proposed to this end, especially regarding the latter, is increased support to participants during the follow-up classroom experimentation. Hence, it is suggested that future implementation of the project should include more practical and hands-on involvement of participants in assessing the technology available in relation to their students’ needs, and in designing and developing accessible and inclusive technology-enhanced reading activities, followed by support and coaching during classroom implementation.

Technological growth has given rise to diverse modes of communication and different types of texts (e.g., digital texts, audios, videos, multimedia, etc.). In line with the principles of inclusive education, as well as current literacy theories, the Living Book approach is based on the fact that oral and written language is no longer the sole means of communication, and that new types of literacy need to be included and cultivated in the classroom. This is especially important when it comes to literacy, which remains rather traditional and sometimes even an ‘elite’ practice. Recognizing the role of literature in children’s development, Living Book built on ways of using AR and other technological tools to promote children’s love for reading, while at the same time, serving the basic principles of inclusive education so that it could reach students with diverse learning needs.

Based on these findings, future research could further explore teachers’ readiness and enduring reservations in implementing AR technologies in the classroom, as well as students’ different modes of engagement with literary texts during literature instruction under the Living Book approach. In addition, future research can be even more attentive to issues of inclusive education and the use of AR, both from the learners’ perspective as well as the teachers’ understanding of the relations between technology integration frameworks and universal design for learning principles. Hence, a long-term focus on the use of AR for differentiation and universal design for learning would be interesting in looking into particular aspects of learners’ participation and engagement, beyond physical access to digital content.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, M.M.-M.; writing—review and editing, A.R.C., C.C., K.M., and C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is being funded by the EU, under the Erasmus + Key Action 2 program (The Living Book—Augmenting Reading For Life (Ref. #: 2016–1-CY01-KA201–017315)). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the EU.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Education and Culture. EU High Level Group of Experts on Literacy: Final Report. 2012. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000217605 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Education and Culture. PISA 2018 and the EU: Striving for Social Fairness through Education. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/education/files/document-library-docs/pisa-2018-eu_1.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2020).