Abstract

This study investigates the correlation between the Gini index and gross domestic product (GDP) in two of the world’s largest capitalist economies: the United States and the United Kingdom. Utilizing econometric methods, including stationarity tests and linear regression, this research work aims to elucidate the relationship between economic inequality and economic growth. The results for the United States reveal a significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index, suggesting that economic growth is associated with rising income inequality. In contrast, the United Kingdom shows a much weaker relationship, indicating that other factors, such as redistributive policies and social welfare programs, may mitigate the impact of economic growth on income inequality. These findings highlight the importance of national policies and institutional frameworks in shaping economic outcomes and can be used in policy making. This study contributes to the existing literature by providing a comparative analysis of the correlation between GDP and the Gini index in two major capitalist economies, offering fresh empirical insights.

Keywords:

economic inequality; Gini index; GDP; growth; comparative analysis; time series; regression analysis 1. Introduction

Economic inequality has become a central issue in contemporary socioeconomic discourse, particularly in advanced capitalist economies. Ingersoll (2024) claims that wealth and income inequality are inherent and inevitable, unable to be fully eradicated by any economic, social, or policy interventions. Gross domestic product (GDP) is a fundamental indicator of economic performance, reflecting the total economic output of a nation (Johnson 2024). The Gini index, a measure of income inequality, has been extensively used to evaluate the distribution of income within a country (Atkinson 2015). Various methods for measuring inequality exist, but the Gini index is the most commonly used due to its simplicity, while poverty, inequality, and social exclusion are interconnected issues being actively addressed through global cooperation and efforts to drive political and voluntary actions forward (Halkos and Aslanidis 2023).

The primary objective of this study is to analyze the correlation between the Gini index and GDP in two of the world’s largest capitalist economies: the United States of America (USA) and the United Kingdom (UK). Despite their economic prowess, these nations exhibit significant disparities in income distribution, making them ideal subjects for this comparative analysis (Piketty 2014). Both the United States and the United Kingdom are leading economies with substantial global influence. Their economic policies and performance not only impact their own populations but also have far-reaching effects on the global economy. Studying these two countries provides valuable insights into the dynamics of economic growth and income inequality in advanced capitalist systems.

The United States is known for its high levels of income inequality, which have been rising over the past several decades due to technological advancements, globalization, and policy decisions (Saez and Zucman 2016), while it is also known for its high levels of GDP growth. Research by Piketty and Saez (2003) demonstrates how economic growth in the United States has disproportionately benefited top-income earners, leading to increased inequality. Autor et al. (2008) observed similar trends, highlighting that wage inequality has increased significantly with economic growth, especially benefiting high-income groups. Chetty et al. (2014) further explored the limited intergenerational mobility in the US, showing how economic opportunities are not equally distributed. Mishel and Bivens (2017) argued that technological advancements exacerbate wage disparities, contributing to overall inequality. Additionally, Stiglitz (2012) emphasized how the current economic policies and market structures in the US have led to a divided society where GDP growth does not equate to equitable wealth distribution.

In contrast, the United Kingdom has implemented various social welfare programs and redistributive policies aimed at reducing income inequality, yet still faces significant challenges in this area. Studies have shown that tax and benefit policies significantly influence income inequality in the UK (Brewer et al. 2013). The impact of social policies on inequality has been highlighted, particularly in the context of the economic crisis and subsequent recovery efforts (Hills et al. 2015). Reports from the Institute for Fiscal Studies emphasize the role of government policies in mitigating inequality and improving living standards (Amin-Smith et al. 2017). These findings indicate that while redistributive policies and social welfare programs can mitigate the impact of economic growth on income inequality, the United Kingdom still experiences significant disparities that require ongoing attention and targeted interventions.

The divergent policy approaches of the United States and the United Kingdom towards economic growth and income distribution offer a unique opportunity to compare and contrast their impacts. The US tends to favor market-oriented policies with less emphasis on redistribution (Lindh and McCall 2022), whereas the UK has a more robust welfare state and actively pursues redistributive measures (Taylor-Gooby and Larsen 2004). This comparison can shed light on the effectiveness of different policy frameworks in managing income inequality.

Additionally, both countries maintain comprehensive and publicly accessible economic data, allowing for a detailed and rigorous econometric analysis. The availability of long-term data on GDP and the Gini index facilitates a thorough investigation of trends and relationships over time. The socio-political contexts of the United States and the United Kingdom also play a crucial role in their economic dynamics. The political climate, public attitudes toward inequality, and historical developments influence how each country addresses economic disparity. Comparing these contexts can provide a deeper understanding of the interplay between economic policies and social outcomes. By focusing on these two major economies, this study aims to contribute to the existing literature with fresh empirical evidence and perspectives. The findings can inform policymakers, economists, and researchers about the implications of economic growth for income inequality and help design more effective strategies to promote equitable growth.

Understanding the relationship between economic growth and income inequality is crucial for formulating effective economic policies. A positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index may suggest that economic growth is accompanied by increasing income disparity, a phenomenon that could have profound socioeconomic implications (Stiglitz 2012). This study aims to provide insights that can help policymakers to balance economic growth with equitable income distribution.

While numerous studies have examined the relationship between economic growth and income inequality, this research is distinctive in its comparative approach, focusing specifically on the United States and the United Kingdom. By analyzing these two major capitalist economies, this study seeks to contribute to the existing literature with fresh perspectives and empirical evidence. This study aims to empirically investigate the correlation between the Gini index and GDP in the United States and the United Kingdom from a comparative perspective. By employing rigorous econometric techniques, this research intends to elucidate whether economic growth in these countries is associated with changes in income inequality.

This study hypothesizes that the United Kingdom and the United States differ significantly in their relationship between economic growth and income inequality due to their differing social welfare systems and policy approaches. The UK, with its stronger redistributive policies and social welfare programs, is expected to show a weaker correlation between GDP growth and rising income inequality compared to the US, where a more market-oriented and neoliberal approach may lead to a stronger connection between economic growth and inequality.

Our research demonstrates the significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index in the United States, suggesting that economic growth is associated with rising income inequality. In contrast, the United Kingdom shows a much weaker relationship, indicating that other factors, such as redistributive policies, play a critical role in moderating this relationship. These findings emphasize the importance of considering national contexts and policy frameworks when addressing economic inequality, offering valuable insights for policymakers aiming to balance economic growth with equitable income distribution.

The study is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed overview of the relevant literature, highlighting the existing findings on the relationship between income inequality and economic growth. In Section Research Gap—Research Question—Research Hypotheses, after reviewing the literature, the research gap is identified, leading to the formulation of the research question and hypotheses. Section 3 outlines the methodology used, including the econometric techniques applied and the rationale behind the selection of the data and methods. Section 4 presents the results, with a comparative analysis of the United States and the United Kingdom, focusing on the relationship between GDP and income inequality. Finally, Section 5 discusses the implications of these findings, emphasizing the differences in policy frameworks and their potential influence on income inequality, while Section 6 offers concluding remarks and suggests areas for further research.

2. Literature Review

Theoretical perspectives on inequality have evolved. Classical economists like Smith (2002) and Ricardo (1821) recognized the potential for the unequal distribution of wealth but were generally optimistic about the self-correcting nature of markets. Marx (1993), however, argued that capitalism inherently leads to increasing inequality and social conflict. Contemporary theories emphasize the role of institutions and power dynamics in shaping inequality (Robinson and Acemoglu 2012). The work of North (1990) and Olson (2022) highlights how institutional frameworks can either mitigate or exacerbate inequality.

Several studies have explored the relationship between GDP and income inequality. Kuznets (1955) hypothesized an inverted U-shaped relationship, suggesting that inequality initially increases with economic growth, but eventually decreases. This hypothesis, known as the Kuznets curve, has been tested in various contexts with mixed results (Acemoglu et al. 2002; Barro 2000).

Piketty (2014) argues that in the long run, the rate of return on capital exceeds the rate of economic growth, leading to increasing inequality. This assertion has been supported by empirical evidence from multiple studies (Saez and Zucman 2016; Stiglitz 2012). Stiglitz (2016), further contends that inequality is not just a byproduct of economic forces but is also influenced by policies and institutional frameworks.

Research by Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) indicates that higher income inequality is associated with various social problems, including poor health outcomes and lower levels of trust. They argue that more equal societies tend to have better social cohesion and overall well-being.

Krugman (2012) emphasizes that economic policies play a crucial role in shaping income distribution. He argues that progressive taxation and social safety nets can mitigate the adverse effects of inequality. Similarly, Deaton (2024) points out that addressing inequality requires a multifaceted approach, including education and healthcare reforms.

Technological change has also been identified as a significant driver of inequality. Autor et al. (2013) show that technological advancements have disproportionately benefited high-skilled workers, leading to a widening income gap. Goldin and Katz (2009) similarly highlight the role of education in mediating the effects of technological change on inequality.

Several cross-country studies have examined the impact of globalization on income inequality. Jaumotte et al. (2013) find that while globalization has contributed to economic growth, it has also exacerbated income disparities in many countries. This is corroborated by the work of Milanovic (2016), who documents the divergent effects of globalization on different segments of the population.

In the context of the United States and the United Kingdom, several studies have documented rising income inequality over the past few decades (Autor 2014; Blundell and Etheridge 2010). The increasing concentration of wealth at the top of the income distribution has been highlighted as a significant concern (Chetty et al. 2014; Krueger 2012).

McGovern et al.’s (2023) study examined the coverage of rising income inequality in major UK and US newspapers from 1990 to 2015, finding that while media attention on the issue increased, especially after the 2008 financial crisis, the framing shifted from conceptualizing inequality to managing it through policy, leading to a more polarized and moralized debate, yet without sparking widespread public outrage.

In comparing the United States and the United Kingdom, Hoffmann et al. (2020) found that while income inequality has increased in both countries since the 1980s, the growth in inequality has been driven by different factors. In the United States, labor income inequality has been the primary driver, with capital income playing an increasing role in more recent years, particularly for high-income individuals. This study highlights that education has significantly contributed to the growing inequality in the US, as rising returns on education have widened the income gap between high- and low-educated workers. By contrast, in the United Kingdom, the role of education in inequality growth has been less pronounced, with returns on education remaining relatively stable in recent years. However, similar to the US, rising labor income inequality has been a significant factor in the overall increase in income disparities. Despite these trends, the UK’s more comprehensive welfare system has helped to cushion the impact of income inequality compared to the US, where the weaker safety net has exacerbated income disparities.

Policy responses to inequality have varied across countries. The Nordic countries, for example, have managed to maintain relatively low levels of inequality through comprehensive welfare states and active labor market policies (Esping-Andersen 1990). In contrast, the United States and the United Kingdom have experienced higher levels of inequality, partly due to implementing fewer redistributive policies (Kenworthy and Pontusson 2005).

The relationship between economic growth and inequality remains complex and context-dependent. While some studies find that economic growth can reduce inequality in the long run (Dollar and Kraay 2002; Kuznets 2019; Shin 2012; Seo et al. 2020), others argue that growth often exacerbates income disparities (Bourguignon 2004; Mallick et al. 2020; Stiglitz 2016).

According to Sakaki (2019), in market economies, income inequality generally follows three patterns—high (United States, United Kingdom, Japan), low (Northern Europe), and medium Gini coefficient levels—while the relationship between income distribution and social welfare poses a challenging issue in economics.

Blundell et al. (2018) found that in the United Kingdom, while the inequality of males’ earnings has increased over recent decades, net family income inequality has remained relatively stable due to the effectiveness of redistributive policies, including expanded welfare programs and tax credits, which have mitigated the impact of wage disparities. In contrast, the United States has experienced significant increases in both earnings and net income inequality, driven by a weaker social safety net and less effective tax and welfare systems. As a result, income inequality has grown sharply in the US, particularly for lower-income households, with fewer policy interventions to counterbalance the effects of rising wage inequality. This comparison underscores the crucial role of policy differences in shaping income distribution in each country.

Chancel et al. (2017) claim that both the United States and the United Kingdom have committed to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 10, which focuses on reducing inequality. The United Kingdom has made more progress, with its stronger redistributive policies and welfare systems helping to mitigate rising income inequality, aligning more closely with SDG 10’s targets for inclusive growth. In contrast, the United States has faced greater challenges due to weaker social safety nets and rising inequality driven by both labor and capital income concentration. Despite its commitment to SDG 10, the US continues to struggle with implementing effective policies to reduce inequality, highlighting the need for significant reforms in taxation, welfare, and labor markets to achieve sustainable development.

Research Gap—Research Question—Research Hypotheses

Despite a substantial body of research, a gap persists in the comparative analysis of the relationship between GDP and the Gini index in major capitalist economies like the United States and the United Kingdom. While individual studies have explored these variables within each country, a consistent, cross-country comparison has been lacking. This study seeks to bridge that gap by offering a comparative analysis of the correlation between GDP and the Gini index in both nations, employing rigorous econometric techniques to provide fresh empirical insights. After a comprehensive review of the literature, this study identifies a need to understand how income inequality, as measured by the Gini index, correlates with GDP in these two countries, leading to the formulation of the research question and hypotheses as follows:

Research Question (RQ):

How do GDP and income inequality, as measured by the Gini index, interact in the United States and the United Kingdom, and are there significant differences between these two economies?

Research Hypotheses for the United Kingdom:

(H0):

There is no significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index in the United Kingdom. Specifically, changes in GDP do not significantly predict changes in income inequality.

(H1):

There is a significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index in the United Kingdom. Specifically, as GDP increases, income inequality also rises.

Research Hypotheses for the United States:

(H0):

There is no significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index in the United States. Specifically, changes in GDP do not significantly predict changes in income inequality.

(H1):

There is a significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index in the United States. Specifically, as GDP increases, income inequality also rises.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

The data for this study were obtained from the World Bank (2024c) database. This dataset consists of annual observations of the Gini index and gross domestic product (GDP) for the United States and the United Kingdom, covering the period from 1968 to 2021. The World Bank was chosen as the source for these data due to its reputation for providing comprehensive, reliable, and globally standardized economic statistics. The World Bank compiles data from national statistical offices and other credible international sources, ensuring accuracy and consistency across countries and periods. By relying on data from such a trusted institution, this study ensured the validity and robustness of its analysis, enhancing the credibility of its findings.

The years 1968 to 2021 were selected for this study because they represent the period for which consistent and comparable data are available for both the United States and the United Kingdom, specifically regarding the Gini index and GDP. This timeframe provided a long-term perspective, allowing us to capture significant economic and policy shifts in both countries, such as periods of economic growth, recessions, and changes in social and fiscal policies. Using this common time range ensured that the analysis remained consistent across both nations, enabling a robust comparative study of income inequality and economic growth. The availability of reliable and standardized data for both variables during these years enhanced the validity of the findings and allowed for meaningful cross-country comparisons.

According to the World Bank (2024a, 2024b), the Gini index quantifies how income (or, in certain cases, consumption expenditure) is distributed among individuals or households within an economy, comparing it to a situation of perfect equality. It utilizes the Lorenz curve, which illustrates the cumulative distribution of income relative to the population, starting from the lowest earners. The Gini index reflects the area between the Lorenz curve and an ideal line of total equality, as a percentage of the total area under that line. A Gini score of 0 indicates complete equality, while 100 signifies absolute inequality. The gross domestic product (GDP) is the total value added by all producers within an economy, including product taxes and excluding any subsidies not factored into product values. It is calculated without accounting for the depreciation of physical assets or the depletion and degradation of natural resources. The data are presented in constant local currency terms. Additionally, the UK’s GDP is reported in billions of GBP, while the US’s GDP is presented in billions of USD.

The selection of the Gini index and GDP for this study was based on their widespread use as standard measures to assess economic inequality and overall economic performance, respectively. The Gini index is a well-established metric for evaluating income inequality, capturing the disparity in income distribution across a population. It provides a quantitative basis to compare inequality both within and between countries. Similarly, GDP is a core indicator of economic output, reflecting the total value of goods and services produced in an economy. It is fundamental for understanding economic growth and performance over time.

A combination of the Gini index and GDP was selected for this study to explore the relationship between economic growth and income inequality, which are two critical dimensions of socioeconomic well-being. While GDP measures the overall economic performance of a country, it does not capture how the benefits of that growth are distributed among the population. The Gini index, on the other hand, specifically quantifies income inequality, revealing the extent to which economic growth is shared across different income groups.

By examining both variables together, we can investigate whether a higher economic output (as measured by GDP) is associated with greater income inequality (as reflected by the Gini index). This relationship is particularly important in the context of advanced economies, where rising GDP may coincide with increasing inequality, as seen in various empirical studies. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for policymakers aiming to balance economic growth with inclusive development, ensuring that the benefits of growth are more equitably distributed.

In the current research, data processing and statistical analysis were carried out using SPSS and R programming software. These tools were applied to ensure a rigorous and accurate analysis of the time series data, with econometric methods such as stationarity tests and linear regression being utilized. The combination of SPSS and R facilitated robust handling of the datasets, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of the relationships between economic growth and income inequality in both countries.

3.2. Method

In this study, a comprehensive suite of statistical methods was employed to rigorously analyze the relationship between GDP and the Gini index for the United States and the United Kingdom. Stationarity tests were first conducted on the time series data to ensure the validity of subsequent analyses. The Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test and the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) test were applied to determine whether the data series were stationary. If non-stationarity was detected, differencing was applied to transform the series into their stationary forms, with a focus on the first differenced variables.

After the stationarity tests and necessary transformations, linear regression analysis was conducted to explore the correlation between the differenced GDP and the Gini index. The regression analysis was used to evaluate the research hypotheses, enabling the quantification of the relationship and providing insights into how changes in economic growth affect income inequality in each country.

Linear regression was selected as the research method for this study due to its effectiveness in analyzing the relationship between a dependent variable (the Gini index) and an independent variable (GDP). This method provided a clear and quantifiable way to understand how changes in GDP, a measure of economic growth, impact income inequality as measured by the Gini index.

Linear regression was particularly suitable for this study because it provides a straightforward interpretation of the relationship between two variables. It quantifies the strength and direction of the association, helping to determine whether GDP growth leads to increases or decreases in income inequality. Additionally, linear regression allows for statistical testing of the significance of the relationship, providing insights into whether the observed correlation between GDP and the Gini index is statistically meaningful or due to random chance.

Furthermore, linear regression is widely used in economic studies and is supported by robust statistical techniques, making it a reliable and well-established method for examining the impact of one variable on another. It also accommodates the analysis of long-term data, such as the 1968–2021 period in this study, and allows for adjustments (such as differencing data) to handle potential issues like non-stationarity. Overall, its simplicity, interpretability, and ability to produce statistically significant results make linear regression an appropriate and effective choice for this research.

In linear regression analysis, the relationship between a dependent variable Y and one or more independent variables X is modeled using a linear equation. For this study, where the dependent variable is the Gini index (measuring income inequality) and the independent variable is GDP, the linear regression model can be expressed mathematically as

where:

Y = β0 + β1X + ε

- Y = Gini index (dependent variable);

- X = GDP (independent variable);

- β0 = intercept (the value of Y when X is zero);

- β1 = slope (the change in Y for a one-unit change in X);

- ε = error term (captures the variation in Y that cannot be explained by X).

The regression coefficient β1 represents the strength and direction of the relationship between GDP and the Gini index. A positive β1 suggests that as GDP increases, income inequality also increases, while a negative β1 would indicate that higher GDP is associated with lower inequality.

The model Gini = β0 + β1GDP + ε allowed us to test whether GDP significantly predicts changes in the Gini index across the given dataset for the two countries. The methodology of our analysis began with the presentation of descriptive statistics for the differenced data of the variables under study, specifically gross domestic product (GDP) and the Gini index. This step provided a fundamental understanding of the dataset, including values such as the mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum for each variable.

Following the descriptive statistics, the regression model summary was examined. Key statistics such as R (the correlation coefficient) were used to indicate the strength of the relationship between the variables. The R-squared value showed the percentage of the variance in the dependent variable (Gini) that can be explained by the independent variable (GDP). The adjusted R-squared value was also provided, offering a more accurate measure that accounts for the number of predictors in the model. The standard error of the estimate indicated how closely the model’s predictions match the actual data. Additionally, the Durbin–Watson statistic was used to check for autocorrelation in the residuals.

Next, ANOVA (analysis of variance) was performed, presenting values such as the sum of squares, degrees of freedom (df), mean square, F-statistic, and significance (Sig.). The F-statistic was used to assess whether the regression model was statistically significant, while the p-value (Sig.) determined if the relationship between GDP and the Gini index is statistically meaningful.

Then, the regression coefficients were analyzed, showing both unstandardized and standardized coefficients. The unstandardized coefficient (B) indicated how much the dependent variable (Gini index) changes for each unit change in the independent variable (GDP). The t-values and p-values for each coefficient were also provided to assess their statistical significance. Afterward, the collinearity diagnostics were reviewed to ensure that there was no collinearity between the independent variables, meaning that the variables were not excessively correlated with each other, which could compromise the validity of the model.

The next step was the analysis of regression residual statistics, where residuals (the differences between observed and predicted values) were examined to confirm that they were normally distributed and to check for any issues in the model. Finally, a scatter plot was presented to illustrate the relationship between differenced GDP and differenced Gini. This visual representation helped to clarify the nature of the relationship between the two variables. Following these steps, the analysis moved on to test the research hypotheses based on the results obtained from the regression model.

The analyses presented in this study are essential for understanding the relationship between GDP and income inequality in two major economies, the United States and the United Kingdom. Each analysis serves a specific purpose in testing the research hypotheses and validating the findings. First, descriptive statistics provide a foundational understanding of the data, offering insights into the variability of GDP and the Gini index. The stationarity tests ensure the reliability of time-series data, making sure that the results are not skewed by non-stationary trends. The regression analysis, including key statistical measures such as R-squared, ANOVA, and coefficients, directly addresses the core research question by quantifying the relationship between economic growth and income inequality. Without these critical analyses, it would be impossible to determine whether GDP growth significantly influences income inequality in either country. Additionally, diagnostics such as collinearity checks and residuals ensure the robustness of the models, validating the integrity of the results. Thus, each component of the analysis is necessary to provide a comprehensive, scientifically rigorous understanding of the dynamics between GDP and income inequality, offering clear value to both academic discourse and policy making.

4. Results

4.1. Stationarity Tests

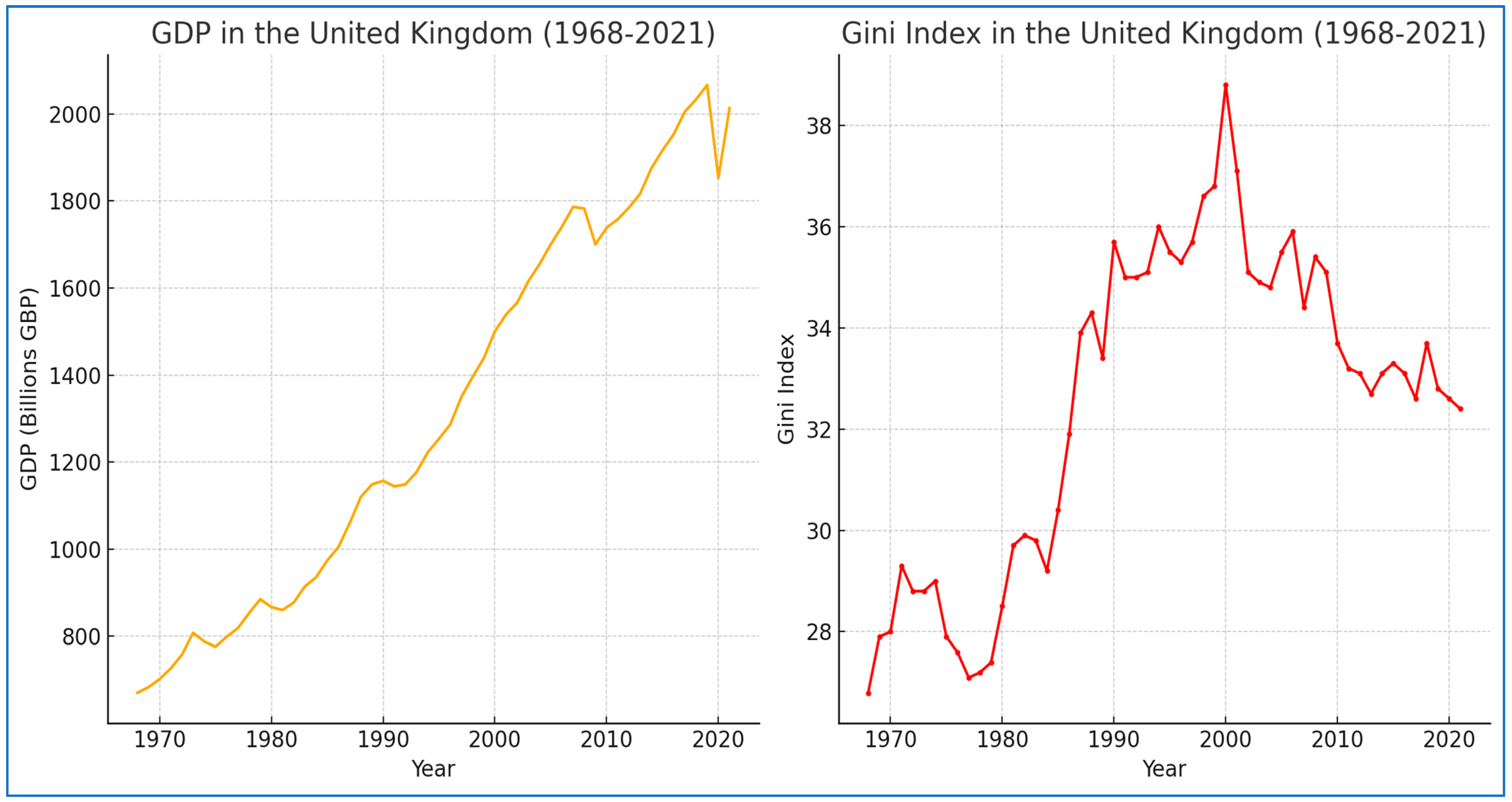

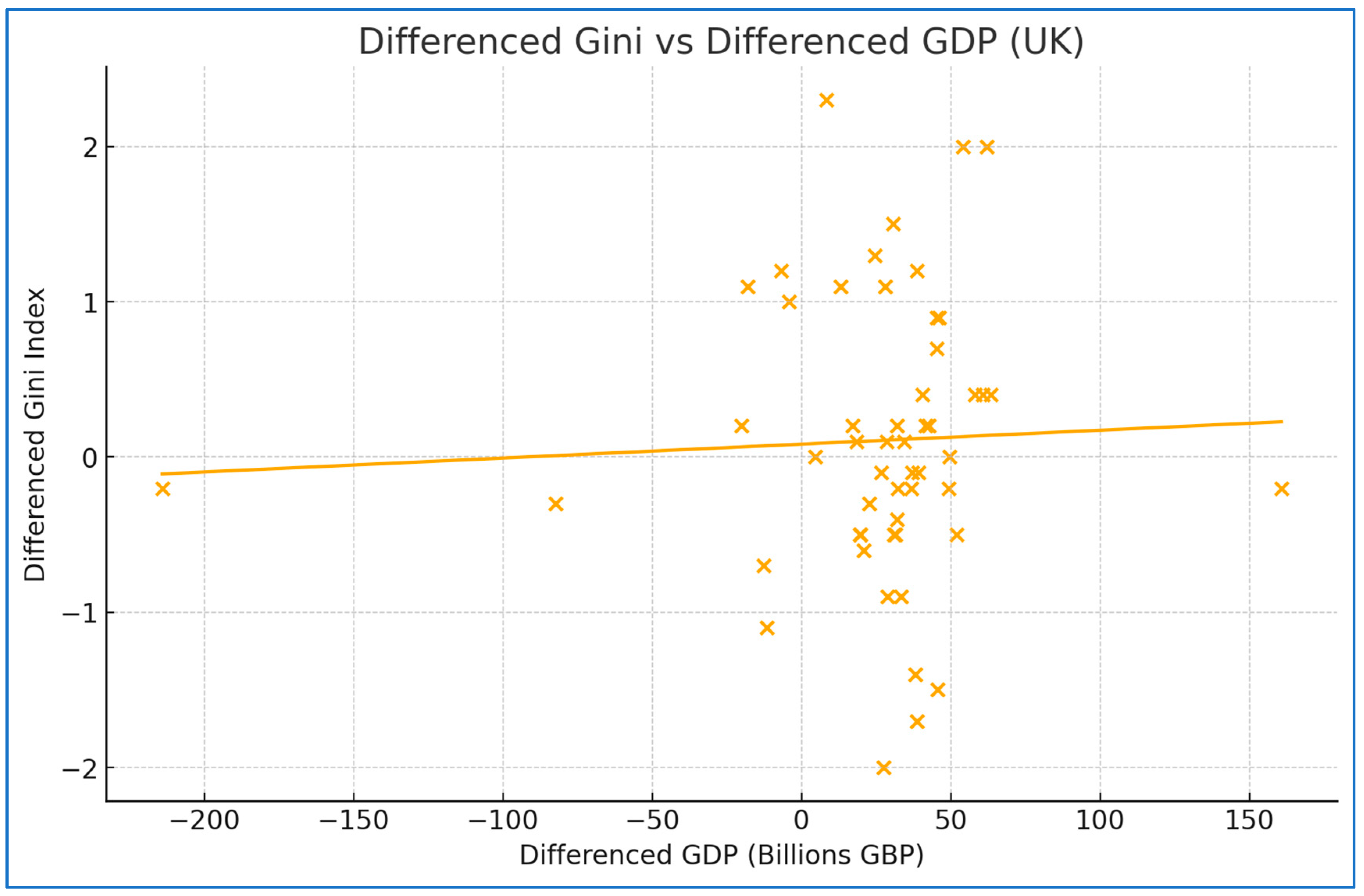

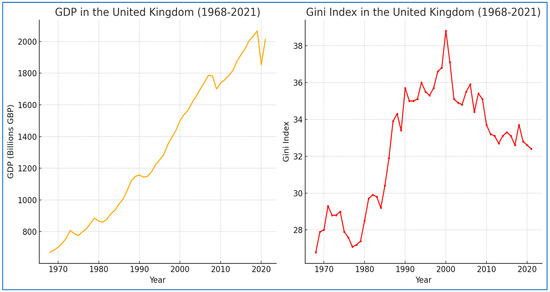

The following figures provide a preliminary depiction of the trends in GDP and the Gini index over time for the United Kingdom and the United States. These initial plots serve as a first impression of the time series, showcasing how economic growth (GDP) and income inequality (Gini index) have evolved in these two major economies. Figure 1 depicts the UK’s GDP over time, showing a generally increasing trend, indicating economic growth over the period from 1968 to 2021. Notably, there are periods of more rapid growth as well as periods of economic downturn, such as during the global financial crisis of 2008–2009. This upward trajectory highlights the overall economic development in the UK during the observed period.

Figure 1.

The UK’s GDP and Gini Index 1968–2021.

The Gini index for the UK exhibits fluctuations over time, reflecting changes in income inequality. The trend suggests periods where inequality increased, especially during the 1980s and early 1990s, which might be associated with policy changes and economic reforms during that era. There are also periods where inequality appears to have stabilized or slightly decreased, possibly due to redistributive policies, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in the United States (Nichols and Rothstein 2015) and progressive income tax systems in many European countries (Elshani and Ahmeti 2017), universal healthcare like the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK (Niemietz 2016), and social welfare programs, such as Social Security in the US (Liebman 2002), unemployment benefits in European countries (Eichhorn 2014), and universal basic income (UBI) experiments (de Paz-Báñez et al. 2020). Overall, the Gini index figure indicates that income inequality has been a persistent issue in the UK, with varying degrees of intensity over the years.

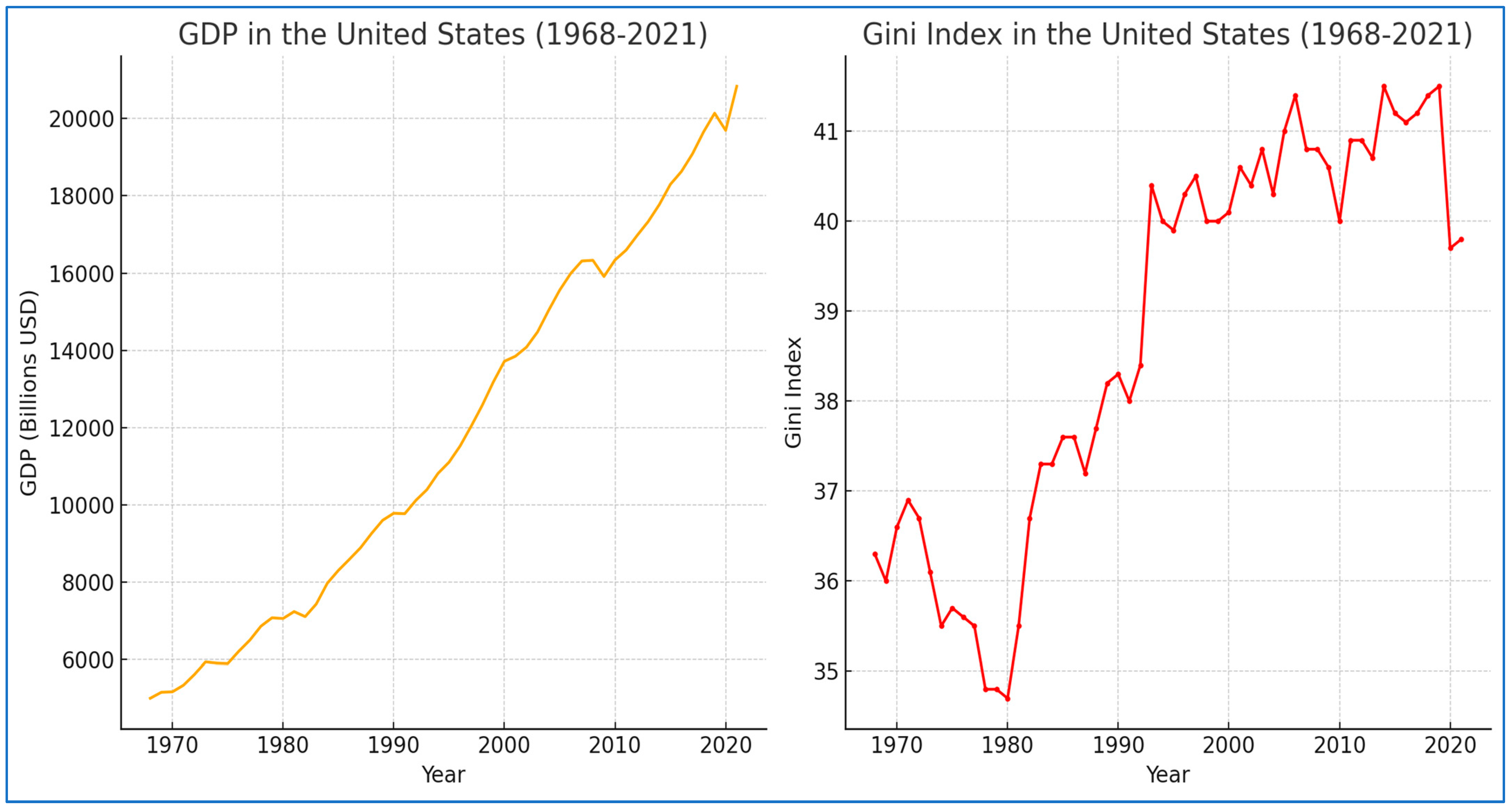

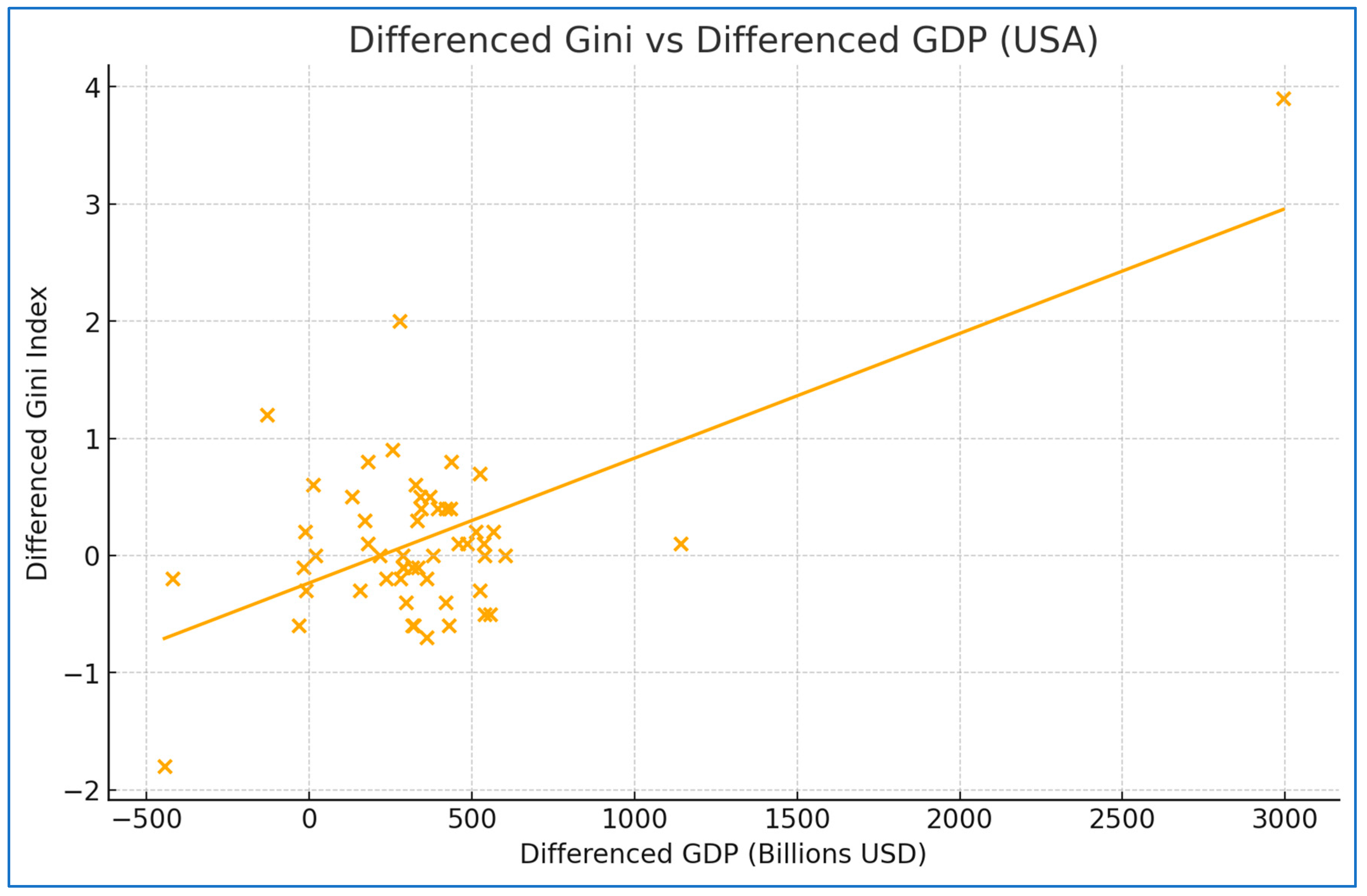

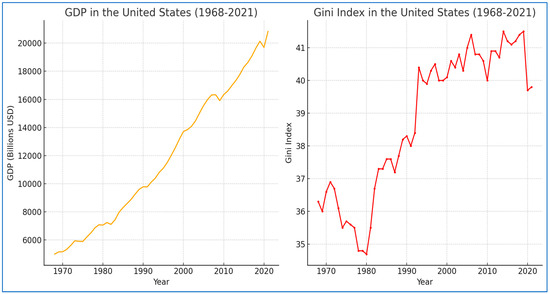

The GDP for the United States (see Figure 2) shows a consistent upward trend, indicating robust economic growth from 1968 to 2021. Similar to the UK, the USA experienced significant growth spurts as well as recessions, such as during the early 1980s and the financial crisis of 2008–2009. The overall growth trend underscores the strong economic performance of the US economy over the observed period.

Figure 2.

USA: GDP and Gini Index 1968–2021.

The Gini index for the USA shows a clear upward trend, indicating a steady increase in income inequality over time. The rise in the Gini index is particularly pronounced from the late 1970s onward, suggesting that economic growth has been accompanied by increasing disparities in income distribution. This trend highlights the growing challenge of income inequality in the USA, which has become a prominent issue in economic and social policy discussions.

Given the apparent trends in the data, it is essential to perform stationarity checks, such as the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) tests, to ensure the validity and reliability of further statistical analyses. Stationarity is a critical property in time series data, indicating that the statistical properties of the series, such as mean and variance, do not change over time. Non-stationary data can lead to spurious regression results, where relationships between variables appear significant when they are not. The ADF test helps to detect the presence of a unit root, suggesting non-stationarity, while the KPSS test assesses the stationarity of the series around a deterministic trend. By confirming that the data are stationary, we can proceed with regression analysis.

The stationarity tests conducted for the United Kingdom, as shown in Table 1, reveal important findings regarding the behavior of the GDP and Gini series. For the UK’s GDP, the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test fails to reject the hypothesis of non-stationarity, indicating that the GDP series does not exhibit stationarity. Additionally, the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) test rejects the null hypothesis of stationarity, further supporting the conclusion that the GDP series is non-stationary.

Table 1.

Stationarity test results for the United Kingdom.

Similarly, the stationarity tests for the UK’s Gini coefficient yield consistent results. The ADF test, once again, does not reject the null hypothesis of non-stationarity, implying that the Gini series lacks stationarity. Meanwhile, the KPSS test rejects the hypothesis of stationarity, confirming that the Gini series also demonstrates non-stationary behavior. These results suggest that both the UK’s GDP and Gini series exhibit trends or patterns over time that do not revert to a constant mean, implying potential long-term shifts in economic output and income inequality.

The stationarity tests for the United States, as presented in Table 2, provide key insights into the behavior of the GDP and Gini series. For the USA’s GDP series, the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test does not reject the hypothesis of non-stationarity, indicating that the series is not stationary. Similarly, the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) test rejects the hypothesis of stationarity, reinforcing the conclusion that the GDP series lacks stationarity.

Table 2.

Stationarity test results for the United States.

For the USA’s Gini series, the results are consistent with those for its GDP series. The ADF test again fails to reject the hypothesis of non-stationarity, and the KPSS test rejects the hypothesis of stationarity. This suggests that the Gini series, like the GDP series, is non-stationary. Given these findings, further differencing of both datasets is necessary to achieve stationarity before proceeding with linear regression analysis. This step is critical to ensure reliable and valid results in subsequent statistical modeling.

The stationarity tests for the United Kingdom, as outlined in Table 3, provide important results regarding the differenced series for the GDP and Gini coefficient. For the differenced UK GDP series, the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test rejects the hypothesis of non-stationarity, while the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) test does not reject the hypothesis of stationarity. These findings indicate that the differenced GDP series achieves stationarity.

Table 3.

Stationarity test results for differenced data for the United Kingdom.

Similarly, for the differenced UK Gini series, the ADF test rejects the hypothesis of non-stationarity, and the KPSS test fails to reject the hypothesis of stationarity. This suggests that the differenced Gini series is also stationary. The stationarity of both series confirms that the data are now suitable for further analysis, including regression modeling.

The stationarity tests for the United States, as presented in Table 4, reveal key findings for the differenced GDP and Gini series. For the differenced USA GDP series, the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test rejects the hypothesis of non-stationarity, while the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) test does not reject the hypothesis of stationarity. This indicates that the differenced GDP series is stationary.

Table 4.

Stationarity test results for differenced data for the United States.

Similarly, for the differenced USA Gini series, the ADF test rejects the hypothesis of non-stationarity, while the KPSS test fails to reject the hypothesis of stationarity. These results suggest that the differenced Gini series also achieves stationarity, making both the GDP and Gini series suitable for further statistical analysis. This confirms that the data can now be utilized effectively in regression models without the risk of non-stationarity-related distortions.

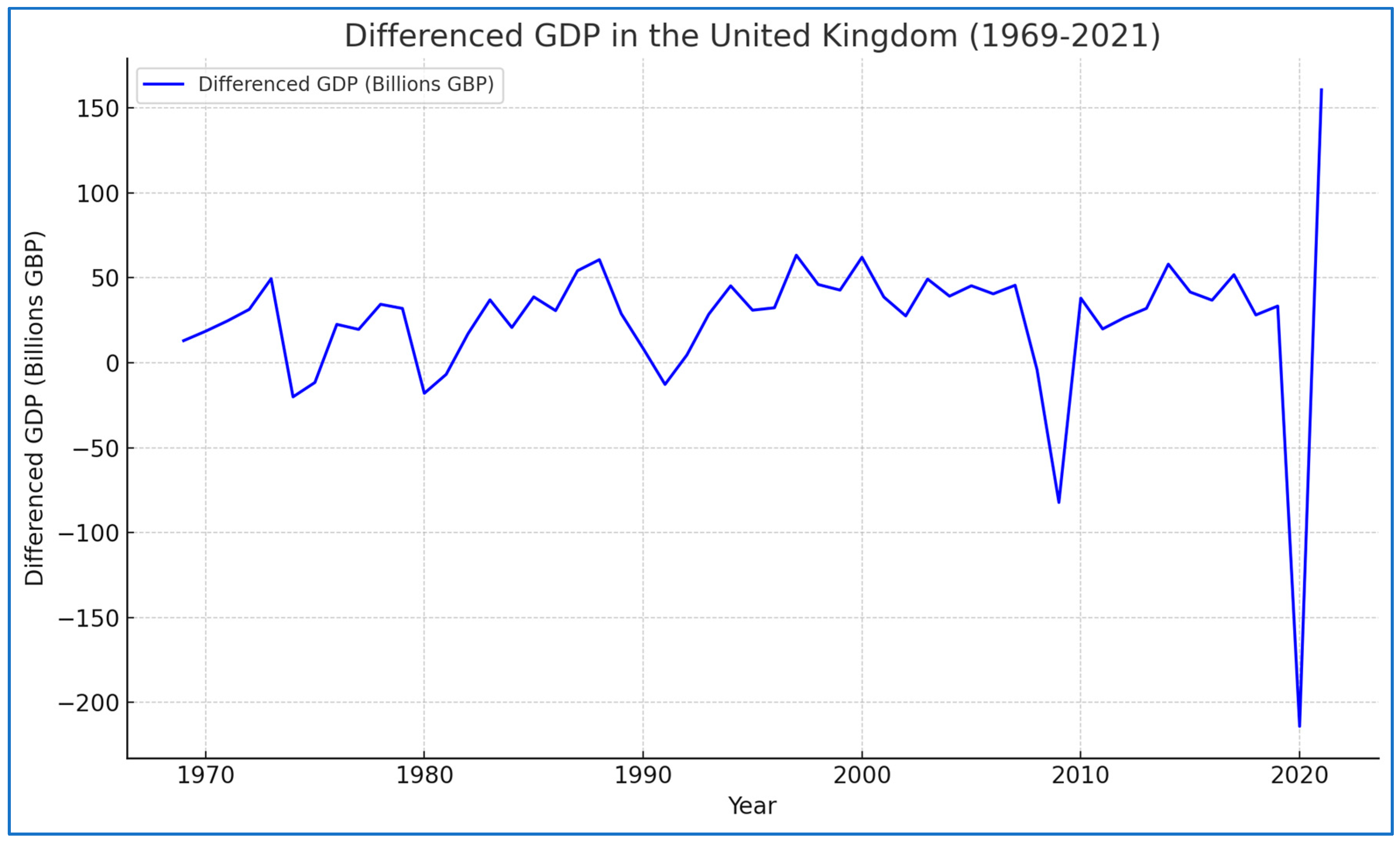

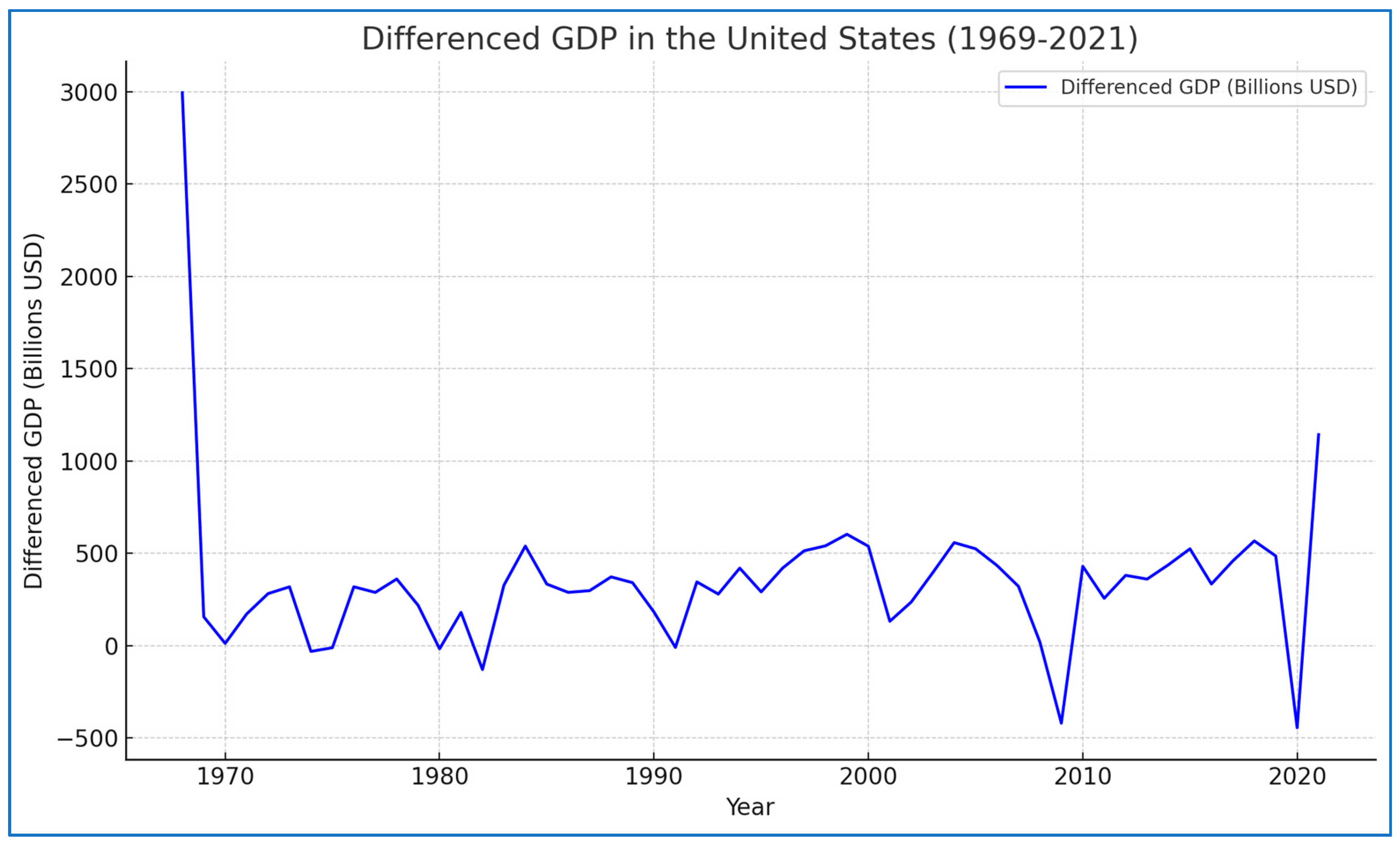

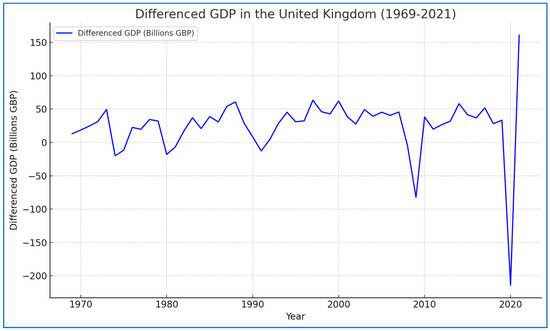

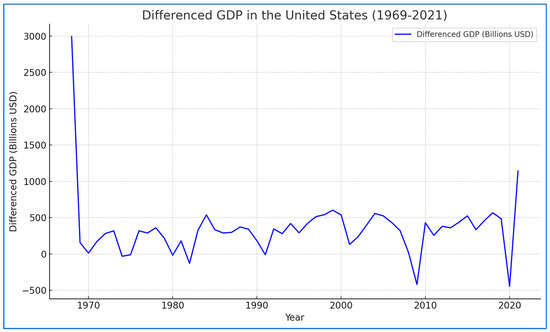

The following figures (Figure 3 and Figure 4) provide a visualization of the trends in the differenced GDP series for the United Kingdom and the United States. They show the fluctuations and changes in the differenced data over time, highlighting the stationary nature of the transformed series. These figures (Figure 3 and Figure 4) suggest that the differencing step helps in stabilizing the mean, making the series more stationary. These figures display the differenced GDP values over the years for each country, highlighting the stationary nature of the data after differencing. Given these results, the differenced GDP series for the UK and USA are now stationary, making them suitable for further analysis such as linear regression.

Figure 3.

Differenced GDP time series for the United Kingdom.

Figure 4.

Differenced GDP time series for the United States.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

In the following section, we present the descriptive statistics regarding the differenced data for both the United Kingdom and the United States. This includes key metrics such as the range, mean, minimum, maximum, standard deviation, and variance for the Gini index and GDP for each country. These statistics provide a foundational understanding of the variability and distribution of income inequality and economic output over the study period, allowing us to explore the relationship between these two important economic indicators in both economies.

To provide context for the exceptionally high GDP figures observed in both the United States and the United Kingdom, it is essential to recognize their status as leading global economies. These figures reflect not only significant industrial activity but also their roles in international markets. The large GDP values should be interpreted alongside the economic growth trajectories experienced during the study period, which included both periods of robust expansion and economic contraction. This context is vital for understanding the intricate relationship between GDP and the Gini index, as it illustrates how substantial economic output can coexist with varying levels of income inequality.

The UK’s Gini index (Table 5) shows a range of 4.30, with a mean of 0.105, indicating moderate variation in income inequality during the observed period. The standard deviation of 0.917 reflects the spread of income inequality, showing moderate fluctuations. On the other hand, the UK’s GDP has a wide range of approximately GBP 374.8 billion, with a mean GDP of around GBP 25.32 billion. The standard deviation of GBP 45.70 billion indicates substantial variability in GDP, reflecting periods of both economic growth and contraction.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics for the United Kingdom.

The USA’s Gini index (Table 6) shows a range of 5.7, with a mean of 0.137, indicating moderate changes in income inequality over time. The standard deviation of 0.766 shows a reasonable degree of variation in inequality, but it is not excessively wide. The US’s GDP, on the other hand, has an extremely wide range of approximately USD 3440 billion, reflecting significant economic fluctuations during the observed period. The mean GDP is around USD 348.5 billion, with a very high standard deviation of USD 445.1 billion, indicating substantial variability in economic performance. This large spread reflects major economic growth and downturns over the years.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics for the United States.

4.3. Linear Regression

To analyze the relationship between GDP and the Gini index, we perform a regression analysis on the differenced data. The Gini index is used as the dependent variable, and GDP is used as the independent variable. We use a significance level of α = 5% to evaluate the statistical significance of the results. Tables with the statistical results and their interpretation are presented. The purpose of this analysis is to verify the research hypotheses regarding the correlation between GDP and income inequality. This approach allows us to determine whether changes in GDP significantly impact income inequality in each country.

4.3.1. Linear Regression for the United Kingdom

The regression analysis results for the relationship between GDP and the Gini index (see Table 7) show a very low correlation coefficient (R) of 0.045, indicating a weak linear relationship between the two variables. The R-squared value of 0.002 suggests that only 0.2% of the variance in the Gini index can be explained by changes in GDP, implying that GDP is not a significant predictor of income inequality in this model. The adjusted R-squared value of −0.018 further confirms the poor explanatory power of the model, as it accounts for the number of predictors and is negative, indicating that the model performs worse than a simple mean model. The standard error of the estimate (0.925) shows the average distance that the observed values fall from the regression line. The Durbin–Watson statistic (1.958) is close to 2, indicating no significant autocorrelation in the residuals. Overall, these results suggest that changes in GDP do not significantly impact the Gini index, and the model has very limited explanatory power.

Table 7.

United Kingdom regression model summary.

The ANOVA analysis results indicate that the regression model does not significantly explain the variation in the differenced Gini index (see Table 8). The regression sum of squares (SSR) is 0.087, while the residual sum of squares (SSE) is 43.641, leading to a total sum of squares (SST) of 43.728. With degrees of freedom (df) of 1 for the regression and 51 for the residuals, the mean squares are 0.087 and 0.856, respectively. The F-statistic is 0.102, and the significance (p-value) is 0.751, which is much greater than the common significance level of 0.05. This high p-value indicates that we fail to reject hypothesis H0, suggesting that changes in GDP do not significantly predict changes in the Gini coefficient. Consequently, the regression model does not demonstrate a significant impact of GDP changes on income inequality for the data analyzed.

Table 8.

United Kingdom regression and residuals summary.

Table 9 provides coefficients from the regression analysis, including both unstandardized and standardized coefficients, along with their standard errors, t-values, and significance levels. The intercept (constant) has an unstandardized coefficient (B) of 0.083 with a standard error of 0.146, resulting in a t-value of 0.570 and a significance (p-value) of 0.571. This high p-value indicates that the intercept is not significantly different from zero, suggesting it does not have a meaningful baseline level in this context. For the UK’s GDP (differenced), the unstandardized coefficient is 8.966 × 10−13 with a standard error of 0.000 and a standardized coefficient (Beta) of 0.045. The t-value is 0.319 with a significance (p-value) of 0.751. These values indicate a very weak positive relationship between GDP and the Gini index; however, the high p-value suggests that this relationship is not statistically significant. Therefore, changes in GDP do not significantly predict changes in income inequality for the United Kingdom. Overall, the coefficients indicate no significant relationship between the differenced GDP and the differenced Gini index for the United Kingdom, with high p-values for both the intercept and the GDP coefficient suggesting that neither contributes meaningfully to predicting changes in income inequality in this regression model.

Table 9.

United Kingdom regression coefficients.

Table 10 provides diagnostic measures for multicollinearity in the regression analysis. The eigenvalue and condition index are used to assess the presence of multicollinearity among the predictors. An eigenvalue close to zero indicates potential multicollinearity, while a high condition index (greater than 15 or 30) suggests severe multicollinearity. In this case, the condition indices are 1.000 and 1.705, both well below the threshold indicating no severe multicollinearity. The variance proportions show how the variance of each coefficient is distributed across the different dimensions. For both the constant and the UK’s GDP, the variance proportions are 0.26 and 0.74 for the two components, respectively. These results suggest that there is no significant multicollinearity affecting the regression model, as the condition indices are low and the variance proportions are evenly distributed, ensuring the stability and reliability of the regression coefficients.

Table 10.

United Kingdom regression collinearity diagnostics.

The residual statistics (see Table 11) indicate that the predicted values of the differenced Gini index range from −0.109 to 0.227, with a mean of 0.105 and a standard deviation of 0.040. The residuals, which represent the differences between observed and predicted values, range from −2.107 to 2.209, with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 0.916, suggesting they are centered around the regression line. The standardized predicted values have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, facilitating easier comparison. Similarly, the standardized residuals have a mean of zero and a standard deviation close to one (0.990), indicating a roughly normal distribution. These statistics suggest that the model’s residuals are appropriately distributed, supporting the assumption of normality in regression analysis.

Table 11.

United Kingdom regression residuals statistics.

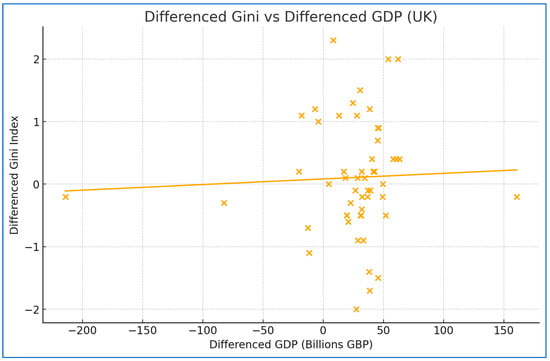

Figure 5 shows the scatter of differenced GDP versus differenced Gini, along with a regression line. The scattered points and the nearly horizontal regression line indicate a weak or nonexistent relationship between the two variables.

Figure 5.

Relationship between differenced GDP and differenced Gini for the United Kingdom.

4.3.2. Linear Regression for United States of America

The model summary (see Table 12) for the linear regression analysis of the relationship between GDP and the Gini index in the United States shows a moderate to strong positive correlation (R = 0.618), indicating that as GDP increases, the Gini index also tends to rise. The R-squared value of 0.382 means that approximately 38.2% of the variance in the Gini index can be explained by changes in GDP, suggesting a moderate level of explanatory power. The adjusted R-squared value of 0.370 confirms this, indicating that around 37% of the variance is accounted for after adjusting for the number of predictors. The standard error of the estimate is 0.608, suggesting reasonably accurate model predictions. The Durbin–Watson statistic of 1.831 indicates little to no autocorrelation in the residuals. Overall, these results support the hypothesis that GDP growth is associated with increases in income inequality in the United States.

Table 12.

United States regression model summary.

The ANOVA results (see Table 13) for the linear regression analysis of the relationship between GDP and the Gini index in the United States indicate that the model significantly explains the variation in the Gini index. The regression sum of squares (11.895) is substantially higher than the residual sum of squares (19.251), suggesting that the model captures a significant portion of the variation in the data. With degrees of freedom of 1 for the regression and 52 for the residuals, the mean square for the regression is 11.895, compared to 0.370 for the residuals. The high F-statistic (32.130) and the associated p-value (0.000) indicate that the model is statistically significant, leading us to reject hypothesis H0 that the model does not explain the variation in the Gini index. Thus, the relationship between GDP and the Gini index is confirmed to be statistically significant.

Table 13.

United States regression and residuals summary.

The coefficients in Table 14 for the linear regression analysis of the relationship between GDP and the Gini index in the United States reveal significant findings (see Table 12). The intercept (constant) has an unstandardized coefficient (B) of −0.234 with a standard error of 0.106, resulting in a t-value of −2.217 and a p-value of 0.031, indicating that the intercept is significantly different from zero. The coefficient for GDP is 1.064 × 10−12, with a standard error of 0.000 and a standardized coefficient (Beta) of 0.618. The t-value for GDP is 5.668 with a p-value of 0.000, showing that GDP is a highly significant predictor of the Gini index. The positive standardized coefficient indicates a strong positive relationship between GDP and the Gini index, suggesting that as GDP increases, income inequality also rises. These results confirm hypothesis H1, that GDP growth is associated with increased income inequality in the United States.

Table 14.

United States regression coefficients.

Table 15, analyzing eigenvalues and condition indices for the regression model’s predictors, provides insights into multicollinearity. The eigenvalues are 1.620 and 0.380, with condition indices of 1.000 and 2.065, respectively. These low condition indices indicate no severe multicollinearity among the predictors. The variance proportions for both the constant and the USA’s GDP are 0.19 and 0.81, respectively, for the two components. This distribution suggests that the predictors do not suffer from multicollinearity, ensuring the stability and reliability of the regression coefficients. Thus, the predictors in the model are not highly correlated, supporting the validity of the regression analysis results.

Table 15.

United States regression collinearity diagnostics.

The residual statistics (see Table 16) provide detailed information about the predicted values and residuals from the regression analysis. The predicted values for the differenced Gini index range from −0.708 to 2.953, with a mean of 0.137 and a standard deviation of 0.474, indicating a moderate spread around the mean. The residuals, representing the differences between observed and predicted values, range from −1.092 to 1.938, with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 0.603, suggesting that the residuals are centered around zero and exhibit reasonable variability. The standardized predicted values have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, ranging from −1.785 to 5.944, which indicates that the predicted values are normalized. Similarly, the standardized residuals range from −1.794 to 3.184, with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 0.991, suggesting that the residuals are approximately normally distributed. These statistics confirm that the model’s residuals are appropriately distributed, supporting the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity in the regression analysis.

Table 16.

United States regression residuals statistics.

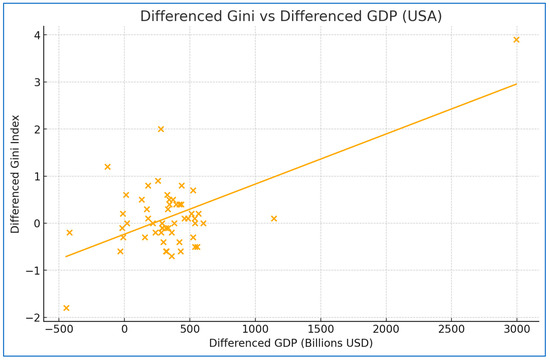

Figure 6 shows the scatter of differenced GDP versus differenced Gini, along with a regression line. The upward slope of the regression line suggests a positive relationship between differenced GDP and differenced Gini, indicating that increases in GDP are associated with increases in income inequality

Figure 6.

Relationship between differenced GDP and differenced Gini for the United States.

4.4. Evaluation of Research Hypotheses

Based on the results of the regression analysis for the United Kingdom, the research hypothesis that there is a significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index is rejected. The regression model yielded an R-squared value of 0.002, indicating that only 0.2% of the variance in the Gini index can be explained by changes in GDP. The F-statistic of 0.102 and the corresponding p-value of 0.751 further confirm that the model is not statistically significant. Additionally, the coefficient for GDP was 8.966 × 10−13 with a high p-value of 0.751, indicating that GDP is not a significant predictor of the Gini index. These results suggest that changes in GDP do not significantly impact income inequality in the United Kingdom, leading to the rejection of hypothesis H1 and the acceptance of the hypothesis H0.

For the United States, the regression analysis supports the research hypothesis that there is a significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index. The model showed an R-squared value of 0.382, meaning that 38.2% of the variance in the Gini index can be explained by changes in GDP. The F-statistic of 32.130 with a p-value of 0.000 indicates that the model is highly significant. The coefficient for GDP was 1.064 × 10−12 with a p-value of 0.000, confirming that GDP is a significant predictor of the Gini index. These findings demonstrate a strong positive relationship between GDP growth and income inequality in the United States, leading to the rejection of hypothesis H0 and the acceptance of hypothesis H1.

5. Discussion

The results of this study show no significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index in the United Kingdom. The regression analysis results for the United Kingdom indicate that changes in GDP do not significantly predict changes in the Gini index. The R-squared value of 0.002 suggests that only 0.2% of the variance in income inequality, as measured by the Gini index, can be explained by variations in GDP. This extremely low explanatory power indicates that other factors, not captured by GDP alone, likely drive changes in income inequality. The high p-value (0.751) for the F-statistic and the GDP coefficient further confirms that the relationship between GDP and the Gini index is not statistically significant. These findings lead to the rejection of hypothesis H1 and acceptance of hypothesis H1, indicating no significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index in the United Kingdom. This result may reflect the complexity of income inequality dynamics in the UK, where other economic, social, and policy factors play a more substantial role than GDP alone.

This finding is consistent with similar studies that highlight the complex and multifaceted nature of income inequality in the UK. For instance, Brewer and Wren-Lewis (2016) found that income inequality in the UK is influenced more by tax and benefit policies, labor market changes, and educational disparities rather than GDP growth alone. Their study concluded that the effects of economic growth on income distribution are mitigated by these factors.

In contrast, the regression analysis for the United States supports the hypothesis that there is a significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index. The model’s R-squared value of 0.382 indicates that 38.2% of the variance in the Gini index can be explained by changes in GDP, suggesting a moderate explanatory power. The F-statistic of 32.130 and its corresponding p-value of 0.000 highlight the model’s statistical significance. Additionally, the GDP coefficient’s p-value of 0.000 confirms that GDP is a highly significant predictor of the Gini index. These results support hypothesis H1, demonstrating that as GDP increases, income inequality also rises in the United States. This finding aligns with the existing literature that suggests economic growth in the US often benefits higher-income groups disproportionately, leading to increased income inequality. The strong positive relationship between GDP and the Gini index underscores the need for policies that address the unequal distribution of economic gains.

Autor et al. (2008) also observed that wage inequality has increased with economic growth in the USA and found that persistent increases in wage disparity since the late 1980s are largely due to the mechanical effects of labor force composition changes that cause confusion. Mishel and Bivens (2017) argued that technological advancements exacerbate wage disparities, contributing to inequality.

The findings for the United Kingdom, which show no significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index, suggest that income inequality is driven by factors other than GDP growth. Economic policies in the UK should focus on structural reforms and targeted interventions to address the root causes of inequality. This could include progressive taxation, which ensures that higher income earners contribute a fair share, and enhancing social welfare programs to support low-income households. Additionally, investment in education and skills development is crucial to address disparities in the labor market and promote social mobility. Policies aimed at improving access to affordable housing and healthcare can also help to reduce inequality. These targeted measures can help ensure that the benefits of economic growth are more evenly distributed across the population.

The significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index in the United States implies that economic growth has led to increased income inequality, with benefits accruing disproportionately for higher-income groups. To address this, economic policies should aim to promote inclusive growth. This can be achieved through progressive taxation, ensuring that wealthy individuals and corporations pay their fair share. Strengthening social safety nets, such as unemployment benefits and food assistance programs, can provide a buffer for those at the lower end of the income distribution. Investing in education, particularly in underserved communities, can help reduce inequality by providing equal opportunities for all. Additionally, policies that promote wage growth, such as increasing the minimum wage and supporting collective bargaining, can help to ensure that workers share in the economic gains. Addressing healthcare affordability and accessibility is also critical to reducing the financial burden on low-income households.

The phenomenon of income inequality manifests differently in the United Kingdom and the United States, as evidenced by the regression analysis and corroborated by the literature. In the United Kingdom, income inequality appears to be less influenced by GDP growth and more by structural factors such as tax policies, labor market changes, and social welfare programs. In contrast, the United States shows a significant positive correlation between GDP growth and income inequality, indicating that economic growth tends to benefit higher-income groups disproportionately. This dichotomy suggests that while both countries experience income inequality, the underlying causes and effective mitigation strategies differ. The UK may benefit more from policy interventions targeting social equity and labor market reforms, whereas the US needs to address the distribution of economic gains to ensure that growth benefits all socioeconomic strata. This comparative analysis underscores the importance of understanding the unique socioeconomic dynamics within each country to formulate effective policies for reducing income inequality.

Theories of capitalism and inequality provide various lenses to interpret our findings. Marxist theory and Piketty’s analysis explain the increasing inequality in the US, while the Kuznets Curve and Human Capital Theory offer insights into the UK’s different experiences. Neoliberalism’s impact on policy and inequality highlights the importance of considering economic policies’ broader implications. Understanding these theoretical frameworks helps to contextualize the complex relationship between economic growth and income inequality in different capitalist economies.

Karl Marx (1993) posited that capitalism inherently leads to inequality, as the capitalist class (bourgeoisie) exploits the working class (proletariat). The accumulation of capital by the few results in increasing disparities in wealth and power. Our findings in the United States, where GDP growth correlates with increased income inequality, align with Marx’s view that economic growth under capitalism benefits the wealthy disproportionately. Thomas Piketty (2014) argues that when the rate of return on capital exceeds the rate of economic growth, inequality rises. This theory is reflected in our US findings, where economic growth is associated with increased income inequality, suggesting that returns on capital disproportionately benefit the wealthy.

According to Harvey (2007), neoliberal theories advocate for free-market policies, deregulation, and reductions in government spending. Critics argue that such policies exacerbate income inequality. The positive correlation between GDP growth and income inequality in the US found in our study could be seen as a consequence of neoliberal policies that prioritize economic growth over equitable wealth distribution. Human Capital Theory posits that investments in education and skills enhance productivity and economic growth, potentially reducing inequality (Becker 2009). Our findings suggest that in the United Kingdom, where GDP growth does not significantly impact inequality, investing in human capital could play a crucial role in addressing income disparities.

The contrasting results for the United Kingdom and the United States highlight the need for tailored economic policies that reflect the unique socioeconomic dynamics of each country. Stone et al. (2015) provided a comprehensive analysis of historical trends in income inequality, emphasizing the need for policy measures to address these issues. These studies indicate that while GDP growth is essential, it must be accompanied by policies that promote equitable wealth distribution to mitigate the adverse effects of increasing inequality. In the UK, where inequality is less correlated with GDP growth, policies should focus on structural reforms and social equity. In the US, where GDP growth is linked to increasing inequality, policies should aim to ensure that economic gains are more broadly shared. Both countries can benefit from progressive taxation and investments in education and healthcare, but the specific focus and implementation of these policies should be adapted to the different drivers of inequality in each context. For the UK, these focuses should include wage disparity and the labor market structure (Katz 1999), regional disparities, education and skills gap, etc., while for the US, they should comprise the weaker social safety net (Bitler et al. 2020), the high income concentration at the top, educational access and healthcare costs, etc. This nuanced approach can help to create more equitable and sustainable economic growth in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

Our study and Sakaki’s (2019) research highlight the critical role of income inequality and its impact on economic growth in major capitalist economies like the United States and the United Kingdom. While our study uses econometric analysis to show how redistributive policies and social welfare programs can mitigate the effects of economic growth on inequality, particularly in the UK, Sakaki’s agent-based simulation suggests that a more equal income distribution leads to higher long-term growth potential in countries with high marginal propensity to consume, such as the US and UK. The key difference lies in methodology—our research focuses on real-world data and policy impacts, whereas Sakaki’s provides theoretical simulations—but both studies reinforce the importance of addressing inequality through policy interventions to promote sustainable and inclusive growth.

6. Conclusions

The primary objective of this study was to analyze the correlation between the Gini index and gross domestic product (GDP) in the United States and the United Kingdom. By comparing these two major capitalist economies, this research aimed to shed light on the relationship between economic growth and income inequality, using rigorous econometric techniques to provide empirical insights.

The analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between GDP and the Gini index in the United States, indicating that economic growth in the US is associated with increasing income inequality. In contrast, the United Kingdom exhibited a much weaker relationship between GDP and the Gini index. The regression results for the UK showed no significant correlation, suggesting that other factors, such as redistributive policies and social welfare programs, might mitigate the impact of economic growth on income inequality.

This study contributes to the existing body of research by providing a comparative analysis of the correlation between GDP and the Gini index in two major capitalist economies. While many studies have examined these variables individually within each country, this research is innovative in its direct comparison using consistent methodologies. By focusing on the United States and the United Kingdom, this study offers fresh empirical evidence and insights into the dynamics of economic growth and income inequality.

Like any empirical research, this study has its limitations. The analysis is based on historical data, which may not fully capture future trends and changes in economic policies. Additionally, while this study employs robust econometric techniques, the complexity of economic inequality means that there are likely other contributing factors that were not accounted for in this analysis. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between GDP and income inequality. The use of first-order differencing and rigorous statistical methods ensures that the results are reliable and meaningful. Furthermore, the comparative approach adds depth to the understanding of how different policy frameworks can impact economic outcomes.

Future research in both the United Kingdom and the United States should delve deeper into understanding the multifaceted nature of income inequality. In the UK, studies should explore structural factors such as tax policies, labor market dynamics, and social welfare programs, and their interaction with GDP growth. Longitudinal studies tracking changes over time and regional analyses can provide further insights. For the US, research should evaluate the impact of specific economic policies, technological advancements, and automation on inequality. Investigating the role of education, skills development, and intergenerational mobility is crucial. Comparative studies with other countries that have successfully managed income inequality can offer valuable lessons for both nations, guiding the development of more effective and equitable economic policies.

In light of our findings, it is crucial to acknowledge the risk of a “green unjust transition,” where the focus on environmental sustainability, driven by capitalist and neoliberal approaches, may prioritize economic growth without adequately addressing social inequalities. A transition that neglects the social dimension of the economy could exacerbate existing disparities, leaving vulnerable populations further marginalized. To ensure a just transition, it is essential that policies not only aim for environmental goals but also consider the equitable distribution of benefits and burdens. Addressing both the economic and social sides of this transition is critical to achieving sustainable and inclusive development for all.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; methodology, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; software, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; validation, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; formal analysis, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; investigation, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; resources, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; data curation, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; writing—review and editing, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; visualization, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; supervision, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; project administration, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M.; funding acquisition, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S. and S.P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset can be downloaded at: https://www.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 6 August 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. 2002. Reversal of fortune: Geography and institutions in the making of the modern world income distribution. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117: 1231–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin-Smith, Nicola, Michael Choo, David Phillips, Jessica Glover, Laurie Lucas, Jennifer Goldsworthy, and Nick Jones. 2017. The Local Vantage: How Views of Local Government Finance Vary across Councils. IFS Report, No. R131. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Anthony B. 2015. Inequality: What Can Be Done? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Autor, David H. 2014. Skills, education, and the rise of earnings inequality among the “other 99 percent”. Science 344: 843–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. The China syndrome: Local labor market effects of import competition in the United States. American Economic Review 103: 2121–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, David H., Lawrence F. Katz, and Melissa S. Kearney. 2008. Trends in U.S. wage inequality: Revising the revisionists. The Review of Economics and Statistics 90: 300–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, Robert J. 2000. Inequality and Growth in a Panel of Countries. Journal of Economic Growth 5: 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Gary S. 2009. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitler, Marianne, Hilary W. Hoynes, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach. 2020. The social safety net in the wake of COVID-19. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 119–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, and Beth Etheridge. 2010. Consumption, income and earnings inequality in Britain. Review of Economic Dynamics 13: 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, Robert Joyce, Agnes Norris Keiller, and James P. Ziliak. 2018. Income inequality and the labour market in Britain and the US. Journal of Public Economics 162: 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, François. 2004. The Poverty-Growth-Inequality Triangle (No. 125). Working Paper. New Delhi: Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER). [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Mike, Alastair Muriel, and Liam Wren-Lewis. 2013. Accounting for Changes in Inequality Since 1968: Decomposition Analyses for Great Britain. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Mike, and Liam Wren-Lewis. 2016. Accounting for changes in income inequality: Decomposition analyses for the UK, 1978–2008. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 78: 289–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancel, Lucas, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman. 2017. Global inequality dynamics: New findings from WID.world. American Economic Review 107: 404–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, and Emmanuel Saez. 2014. Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. Quarterly Journal of Economics 129: 1553–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paz-Báñez, Manuela A., María José Asensio-Coto, Celia Sánchez-López, and María-Teresa Aceytuno. 2020. Is there empirical evidence on how the implementation of a universal basic income (UBI) affects labour supply? A systematic review. Sustainability 12: 9459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, Angus. 2024. The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dollar, David, and Aart Kraay. 2002. Growth is Good for the Poor. Journal of Economic Growth 7: 195–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, Jan. 2014. The (non-) effect of unemployment benefits: Variations in the effect of unemployment on life-satisfaction between EU countries. Social Indicators Research 119: 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshani, Alban, and Skender Ahmeti. 2017. The Effect of Progressive Tax on Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence from European OECD Countries. International Journal of Economic Perspectives 11: 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, Claudia, and Lawrence F. Katz. 2009. The Race between Education and Technology. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halkos, George E., and Panagiotis-Stavros C. Aslanidis. 2023. Causes and Measures of Poverty, Inequality, and Social Exclusion: A Review. Economies 11: 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, David. 2007. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, John, John Cunliffe, Polina Obolenskaya, and Eleni Karagiannaki. 2015. Falling behind, Getting ahead: The Changing Structure of Inequality in the UK 2007–2013. London: London School of Economics and Political Science. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, Florian, David S. Lee, Thomas Lemieux, and Aloysius Siow. 2020. Growing income inequality in the United States and other advanced economies. Journal of Economic Perspectives 34: 52–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, John G. 2024. Inequality in the Distribution of Wealth and Income as a Natural Consequence of the Equal Opportunity of All Members in the Economic System Represented by a Scale-Free Network. Economies 12: 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaumotte, Florence, Subir Lall, and Chris Papageorgiou. 2013. Rising income inequality: Technology, or trade and financial globalization? IMF Economic Review 61: 271–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, David W. 2024. N. Gregory Mankiw (1958–). In The Palgrave Companion to Harvard Economics. Edited by Robert W. Dimand and Harald Hagemann. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1039–64. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Lawrence F. 1999. Changes in the wage structure and earnings inequality. In Handbook of Labor Economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 3, pp. 1463–555. [Google Scholar]

- Kenworthy, Lane, and Jonas Pontusson. 2005. Rising inequality and the politics of redistribution in affluent countries. Perspectives on Politics 3: 449–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, Alan. 2012. The Rise and Consequences of Inequality. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, January 12. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, Paul. 2012. End This Depression Now! New York: WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznets, Simon. 1955. Economic growth and income inequality. American Economic Review 45: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznets, Simon. 2019. Economic growth and income inequality. In The Gap between Rich and Poor. London: Routledge, pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]