Abstract

Following the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, the emphasis on digitization and robotization has grown at an unprecedented rate in the global economy, resulting in significant changes to the labour market composition and increasing the value of digital skills. The aim of this article is to emphasize the ways in which people’s digital abilities and appetite for online activities are connected to job productivity (salary levels) and to determine which individual internet-based digital skills are genuinely important and correlated with better wages. We employed a Principal Component Analysis (PCA-type factorial analysis) with orthogonal rotation to gain a general understanding of the main components that synthesize the digital capabilities of individuals from the European countries analyzed. We decreased the dimensionality of our initial dataset to two major components, namely comprehensive online skills and digital social and media skills, keeping more than 80% of the overall variability. We then evaluated the potential association between the two created components and the average hourly wages and salaries. Since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have observed an important shift in the impact of digital and internet skills on the job market in Europe. Thus, the development of comprehensive internet skills is highly correlated with individuals’ more effective integration into the labour market in Europe in general and the EU in particular, evidenced by better wage and salary levels (r = 0.740, p < 0.001). On the other hand, we found no correlation between the possibility of obtaining higher salaries for employees and the second component, digital social and media skills. The novelty of our research lies in its specific focus on the unique and immediate impacts of the pandemic, the accelerated adoption of digital skills, the integration of comprehensive individual internet skills, and the use of the most recent data to understand the labour market’s characteristics. This new approach offers fresh insights into how Europe’s workforce could evolve in response to unprecedented challenges, making it distinct from previous studies of labour market skills.

JEL Classification:

J24; J30; M54; O33

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the critical importance of digital skills for workers across various industries and occupations in Europe. The sudden shift to remote work, telehealth, and online education has highlighted the need for foundational digital competencies that enable quick adaptation and upskilling as job requirements evolve.

However, the European workforce faces a significant digital skills gap, with nearly one-third of workers lacking the essential digital proficiencies necessary to thrive in the post-pandemic labour market. Specifically, research data indicate that 13% of workers have no digital skills at all, while an additional 18% possess only very limited digital capabilities (Bergson-Shilcock 2020). While 35% have achieved a baseline level of digital proficiency, the remaining 33% are still struggling to keep up with the rapidly digitizing work environment.

This uneven distribution of digital skills has far-reaching implications for both individual economic mobility and business competitiveness in Europe. Workers with inadequate digital skills face diminished career prospects and reduced earning potential, as employers increasingly demand proficiency in a wide range of internet-based technologies (Bergson-Shilcock 2020). Conversely, businesses that are unable to find digitally skilled employees may struggle to adapt to new market realities, hampering their ability to remain competitive. To address this challenge, policymakers in Europe must prioritize initiatives that enhance the digital literacy of the workforce.

In Europe, various programmes are already in place to promote digital skills, with the European Commission evaluating each member state’s digital development by calculating the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). These initiatives play an important role in increasing individuals’ fundamental digital skills, promoting economic resilience, and decreasing current inequities (European Commission 2022).

Following the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, the emphasis on digitalization and robotization processes has achieved an unparalleled expansion within the global economy, resulting in substantial changes to the labour market’s structure. The automation of the primary production processes, remote work that is frequently performed from home, the expansion of the use of IT processes, and the digitalization of public administration all point to a new face of the labour market.

There are two ways that digitalization may affect the workforce. Thus, when robots take the place of human input, employment may decrease as a result of automation. The emergence of new occupational profiles in line with emerging technologies also contributes to the creation of jobs, as does the rise in demand for technology-based goods and services brought on by declining costs or the emergence of new markets, clientele, or demand areas. Because of the lower prices brought about by the digitization context, more people will have actual income to spend on goods and services, even outside of high-tech areas, which will help create new jobs. Wage levels in the labour market may also be impacted by digitalization (Lee and Clarke 2019). Wage increases may result in gains in productivity and aggregate demand caused by the usage of technology.

With the growth in process automation, starting in 2010 and particularly advancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, people’s digital skills gained significant importance in the job market, and the salary-to-skills relationship became increasingly apparent (Piroșcă et al. 2021). A few points of view in the specialized literature claim that because robotics and digital technologies are constantly advancing, non-automated jobs will eventually become obsolete (Frey and Osborne 2017). According to Bowles, in the next few decades, information and communication technologies (ICTs) will cause between 47% (in Sweden) and up to well over 60% (in Romania) of the labour force in the EU to lose their jobs (Bowles 2014). Additionally, forecasts in the scientific community indicate that ICTs will make it impossible for people to find employment in the future (Ford 2015).

Even with all of these seemingly negative viewpoints, ICTs also offer a number of advantages. These include being able to work around the clock, abolishing dangerous working conditions in some industries, relieving workers of a lot of repetitive work, and removing inefficiencies from productive flows—all of which lead to higher productivity.

The World Economic Forum’s The Future of Jobs Report 2023, which analyzed data from 803 businesses with a combined workforce of over 11.3 million, outlines the following key patterns about how ICTs will affect jobs in the future throughout the 2023–2027 time frame (World Economic Forum 2023):

- -

- In the upcoming five years, technology adoption will continue to be a major factor in corporate transformation. Increased adoption of cutting-edge technologies and expanding digital access are cited by over 85% of surveyed firms as the developments most likely to propel organizational transformation.

- -

- Regarding technology, big data, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence have a strong chance of being adopted. Within the next five years, about 75% of businesses plan to implement these technologies.

- -

- It is anticipated that most technologies will have a net positive influence on jobs over the next five years.

- -

- In 2023, the two most critical thinking abilities for workers will still be analytical and creative thinking; analytical thinking is expected to be the most prioritized skill for training from 2023 to 2027, comprising 10% of training initiatives on average.

- -

- A proportion of 45 percent of companies believe that government support for skill development is a useful tool for helping match skilled workers with jobs.

Our article proposes a critical approach to this widely discussed topic about the future of work in the context of the necessity to constantly develop peoples’ digital abilities against the backdrop of unprecedented digitization and robotization, a phenomenon exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic crisis.

Entire industries have been transformed, and many jobs that existed before the pandemic either disappeared or were significantly altered. Knowing which skills are now in demand helps workers and employers adapt to these structural changes. By concentrating on developing the right skills, individuals may increase their job prospects, while companies can make more appropriate hiring choices and invest in training that is relevant to the future of work. At the same time, understanding the skills that matter post-pandemic helps policymakers design effective interventions that target key industries, support vulnerable workers, and promote job creation.

The aim of this article is to emphasize the ways in which people’ digital abilities and appetite for online activities are connected to job productivity (salary levels) and to determine which individual internet-based digital skills are genuinely important and correlated with better wages, in the context of restructuring and modernization due to the unprecedented impact of ICTs following the end of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This manuscript is organized into six major sections. After the introduction, the main theoretical and practical elements from the specialized literature are briefly presented, followed by the methodological and conceptual norms and a comprehensive explanation of the acquired results. In the final section, the main findings as well as the limitations of our study are highlighted.

2. Literature Review

Digital skills have become increasingly important in the labour market, especially in the context of rapid technological advancements and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Two key dimensions—the rise in the demand for digital skills and the digital transformation of industries—can be used to illustrate how individual digital abilities affect employment opportunities. Digital skills are in high demand across many industries. Many jobs now require digital literacy, including basic IT abilities, while advanced skills like coding, data analysis, and cybersecurity are in high demand (Bessen 2019). Regarding the second dimension, industries such as healthcare, finance, and retail have undergone significant digital transformation, increasing the need for digital skills. For example, telehealth, fintech, and e-commerce have seen substantial growth, creating new job opportunities that require specific digital competencies (McKinsey Global Institute 2021).

One particularly intriguing finding is that there is a significant variation in the relationship between digital skills and inequality across different income groups in Europe. After studying 103 European regions for the period 2003–2013, the authors discovered that digitalization exacerbates inequality among the less affluent while decreasing it among those with higher income levels (Consoli et al. 2023).

Given the exponential growth in both the supply and demand for digital skills, employers need to provide proactive training and assistance to their staff members so they may expand on their current skill sets or pick up new ones (Arulsamy et al. 2023). Retraining employees and luring in fresh talent should be top priorities for European companies and organizations. Encouraging all parties involved in the digital skills and jobs community will strengthen public–private collaborations in the skills domain. Not only those, but education and training systems are essential to creating the “next generation workforce” and can assist close the skills gap that exists between what is currently offered in terms of schooling and what employers are looking for (Jackson et al. 2016).

Crișan et al. looked into how different EU member states were from one another in terms of labour market digitalization in the post-pandemic environment. They took a multifaceted approach, looking at metrics that showed the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects as well as labour market specifics and the level of digitization. Initially, a Pearson test was used to measure the degree of correlation between digitalization and labour market variables, and a cluster analysis was used to identify some trends between high- and medium-tech EU economies and their low-tech counterparts. According to the report, Finland is leading the EU’s digital transition and has the highest proportion of workers with digital skills among the high-tech economies. In contrast, the South-Eastern nations still lack an efficient framework for digital policy that would facilitate youth workers’ access to digital training, and they have the greatest work to do in order to recover (Crisan et al. 2023). Cyprus, Italy, and Belgium are the medium-tech economy cluster members with the most to gain from reshaping their digitalization processes, particularly with regard to integrating digital public services and digitally changing their human resources.

One of the biggest policy issues facing nations in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic is undoubtedly achieving a fair transition to a low carbon economy and society. Businesses, employees, and the organizations that represent them are also deeply concerned about it. A lot of attention has been paid to how this shift could lead to the creation of new jobs, especially at the policy level where clean technology and renewable energy are growing. Strachan et al., in a study conducted in 2022, report that “soft” transferrable abilities, as opposed to “hard” technical skills, are the most important skills needs identified across all levels. It was acknowledged that COVID-19 would both disrupt and spur the green transition (Strachan et al. 2022).

Although comprehensive internet skills are essential for most of the employees to carry out their jobs, it can be challenging to teach people these skills and adjust their skill set as needed. Since some changes may be persistent in the post-COVID-19 era, Gnecco et al. (2024) applied a matrix completion, a machine learning technique frequently used in the context of recommender systems to forecast the average fluctuation in the importance levels of the social soft skills needed for every occupation as working conditions shift. The study revealed that occupations, industries, and age cohorts exhibiting negative average fluctuations are susceptible to a deficiency in their social soft skills foundation, potentially resulting in reduced efficiency (Gnecco et al. 2024). Brucks and Levav (2022) suggest that the COVID-19-induced rise in virtual interaction and working from home may have impeded social soft skills because in-person teams can exchange ideas in a completely shared physical space. Virtual teams, on the other hand, are limited in their engagement because every team member has a screen in front of them (Brucks and Levav 2022).

Digital exclusion is a new socioeconomic concern brought about by the development and globalization of ICT. With time, this problem has developed into a complicated social issue that has immediate effects on the economy across the board. The extent of digital isolation declines as income rises (Śmiałowski and Ochnio 2019). The COVID-19 epidemic has increased the rate at which people are using digital technologies. Digital communication was more likely to have been embraced by younger people, those with greater incomes and educational levels, and those with more internet knowledge and expertise (Nguyen et al. 2021; Song et al. 2021). In particular, from the standpoint of the labour market, this phenomenon is significant on both the macro- and microeconomic levels. There has been a rapid surge in online business and management operations as a result of the COVID-19 epidemic. In 2022, Lacova et al. conducted a study in Slovakia on how digital exclusion is manifested in the labour market (Lacová et al. 2022). They examined both individual and aggregate data that were available to characterize the Slovak labour market from a macro viewpoint and compare it to other EU member states. They discovered that throughout the pandemic, the percentage of people in Slovakia and Europe who did not use the internet decreased significantly. They also found that the resilience of digitally disadvantaged populations, such as persons in financial trouble, those with poor education levels, and those who are at least 55 years old, was at risk due to long-term digital exclusion. Their findings highlighted the need for employers to support their staff members in developing their digital literacy and resilience in order to foster a more diverse and inclusive digital society as well as a more productive labour market in Slovakia (Lacová et al. 2022). A lack of desire or unwillingness to learn even basic digital skills might be linked to digital illiteracy. The findings of the Lacova study demonstrate that this circumstance is not solely the result of financial hardship, poverty, or the inability to purchase a computer. A sizable portion of managers believe that there is an issue with their staff members’ drive and mindset regarding learning digital skills. Given the complexity of social exclusion in the digital age, Bach et al. (2013) make the case for a framework called “Digital Human Capital”, which is meant to expand on and strengthen the call for more technology access and fundamental training programmes (Bach et al. 2013).

In order to be competitive in a job market that is always evolving, people must acquire both fundamental and sophisticated ICT skills, as demonstrated by the “digital surge” brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic throughout Europe (Sundblad and Kolding 2022).

Evangelista et al. examine the economic effects of digital technologies in Europe, making a distinction between the various phases and areas of the digital transformation process. Their econometric analysis indicates that the use of ICT, particularly digital empowerment, has a significant economic impact, particularly on employment, while also favouring the participation of ‘disadvantaged’ groups in the labour market. The authors conclude that digitization could boost productivity and employment development, and that inclusive policies may successfully contribute to closing the gap between the most advantaged and disadvantaged groups in the population, thus attaining the 2020 Europe objectives (Evangelista et al. 2014).

According to another study, using data collected from the Digital Economy and Society Index, which measures EU digital performance, an intense positive correlation was highlighted between salary levels and the digital skills of individuals for the EU countries during the COVID-19 pandemic (Piroșcă et al. 2021). At the same time, in 2021, while trying to identify and highlight any potential relationships between the elements of the digitization trend and the well-being of the population in 11 EU member countries from Central and Eastern Europe, Grigorescu et al. revealed a positive relationship between the dependent and independent variables of their multiple regression model. Their study highlighted that the digitalization of the economy and the development of human capital will eventually lead to an increase in population income (Grigorescu et al. 2021).

At the macroeconomic level, in 2023, Trang et al. investigated the connections between ICT development and IT specialists as well as the workforce’s digital skills and economic development. Using correlation and hierarchical cluster analyses, the study highlighted that almost all indicators of digital skills have a strong and positive correlation with economic development in the European Union countries (EU27) for the period 2020–2021, with the exception of the most basic level of online information and data literacy (Trang et al. 2023; Colbert et al. 2016; Ewing et al. 2019; Moqbel et al. 2013; Chu 2020; Hanna et al. 2011; Li 2016).

Also, Chu’s extremely interesting result indicates that social media use has significant, small, positive associations with workplace performance, job happiness, work engagement, and work–life conflict (Chu 2020).

According to Cone et al., the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated Europe’s digital transition and raised interest in the value of internet use for daily living, employment, and education (Cone et al. 2022). This development could be related to changes in individual earnings and the labour market for the following possible reasons:

- -

- Increased demand for digital skills: the shift to remote work necessitated employees’ proficiency in digital tools and platforms; those with good digital abilities were better positioned to sustain productivity and efficiency, increasing their value to employers.

- -

- Access to global job markets: remote work opened up opportunities for individuals to work for companies beyond their geographic location, often in higher-wage regions or industries, thereby increasing their earning potential.

- -

- Flexible working hours: the internet enables more flexible working arrangements, which can lead to higher productivity and a better work–life balance; higher productivity often translates into higher earnings.

- -

- Innovation and efficiency: businesses that used digital tools and procedures were able to innovate and run more effectively, resulting in increased profitability and the opportunity to raise wages and salaries.

- -

- Upskilling and reskilling: many workers used the pandemic period to upskill or reskill through online courses and training programmes, making them eligible for higher-paying employment.

- -

- Freelance and contract work: the internet facilitates freelance and contract work, allowing individuals to take on multiple projects and clients simultaneously; this flexibility can lead to higher overall earnings compared to traditional employment.

- -

- Access to resources and information: the internet gives people access to a variety of resources and information, allowing them to improve their work performance and advance their careers, resulting in payment increases.

Given that the recent COVID-19 pandemic has caused a significant number of businesses to go online, the goal of this study is to highlight the ways in which individuals’ digital skills and appetite for online activities are related to work productivity and, implicitly, to their salary levels. We will also attempt to identify which individual internet-based digital skills are actually relevant and associated with a better wages and salaries in the 2023 Post-pandemic European Labour Market.

3. Materials and Methods

In order to establish the degree of correlation between individuals’ digital abilities and their success in the European job market, we collected the most recent data from the European Union’s statistics office, EUROSTAT, the Digital Economy and Society division. The European Commission Digital Agenda outlines a set of metrics that evaluate the state of the European information society in four key areas: human capital, connectivity, integration of digital technology, and digital public services.

In our study, we used 10 statistical variables that describe the internet-related digital skills of individuals expressed as percentage of all population in 2023. These variables from the EUROSTAT database are particularly appropriate for describing how individual internet-based digital skills are relevant and associated with better wages because they represent a broad and nuanced set of digital skills that are highly relevant to the modern job market (Eurostat 2023a, 2023b). Their inclusion as indicators of digital competence reflects not only how people use technology but also their potential to earn higher wages through greater productivity, access to remote or flexible work, entrepreneurial activities, and continued professional development. The ability to perform a variety of online tasks is increasingly associated with economic success, making these variables relevant for wage-related studies.

- -

- Individuals using the internet for taking an online course (indicates the willingness and ability to improve skills, which is strongly associated with increased work possibilities and professional advancement). The dataset is accessible via the EUROSTAT website at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/TIN00103/default/table?lang=en&category=isoc.isoc_i.isoc_iiu (accessed on 24 September 2024)

- -

- Individuals regularly using the internet at least once a week (illustrates a fundamental digital competence required for ongoing involvement with online technologies). The dataset is accessible via the EUROSTAT website at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tin00091/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 24 September 2024)

- -

- Individuals with basic or above-basic overall digital skills (must know at least one activity related to each of the following: information and data literacy skills, communication and collaboration skills, digital content creation skills, safety skills, and problem-solving skills). This variable reflects a composite measure of overall digital literacy, which is commonly required for higher-paying occupations. The dataset is accessible via the EUROSTAT website at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tepsr_sp410/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 24 September 2024)

- -

- Individuals using the internet for selling goods or services (connects directly with entrepreneurial activities, where people can generate income through platforms or their own online shops). The dataset is accessible via the EUROSTAT website at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tin00098/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 24 September 2024)

- -

- Individuals using the internet for buying goods or services (manually typed e-mails are excluded). This variable is associated with e-commerce operations, where knowing digital platforms may lead to direct business opportunities or employment in sectors such as digital marketing, sales, or logistics. The dataset is accessible via the EUROSTAT website at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/TIN00096/default/table (accessed on 24 September 2024)

- -

- Individuals using the internet for sending/receiving e-mails (indicates fundamental communication abilities required in most professional contexts). The dataset is accessible via the EUROSTAT website at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tin00094/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 24 September 2024)

- -

- Individuals using the internet for internet banking (includes electronic transactions with a bank for payment, etc., or for looking up account information). It reflects a degree of confidence and familiarity with online financial services, which is essential for managing personal accounts or working in finance-related businesses. The dataset is accessible via the EUROSTAT website at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tin00099/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 24 September 2024)

- -

- Individuals using the internet for telephoning or video calls (indicates proficiency with remote working technologies, which is essential for modern flexible employment, especially in higher-paying industries like project management, consulting, and IT). The dataset is accessible via the EUROSTAT website at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ISOC_CI_AC_I/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 24 September 2024)

- -

- Individuals using the internet for participating in social networks (creating user profile, posting messages or other contributions to Facebook, Twitter, etc.). It indicates active use of social media, which is frequently linked to well-paying, expanding positions in the marketing, content development, and communications sectors. The dataset is accessible via the EUROSTAT website at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tin00127/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 24 September 2024)

- -

- Individuals using the internet for reading online news sites/newspapers/news magazines (represents the ability to acquire knowledge, which is crucial for critical thinking and decision making and is highly regarded in higher-paying professions). The dataset is accessible via the EUROSTAT website at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ISOC_CI_AC_I/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 24 September 2024)

The variables were retrieved in August 2024 from the EUROSTAT database for 30 European nations, including 27 EU members and 3 non-EU member states, for which data were available (Eurostat 2023a, 2023b). We included a direct link to the EUROSTAT website for each analyzed indicator, allowing users to study each dataset in depth.

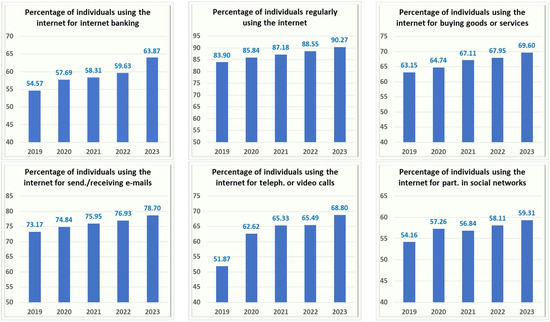

To begin, we discuss the evolution of some previously presented indicators throughout the period 2019–2023. The percentage of EU citizens using online banking services increased from 54.57% in 2019 to 63.87% in 2023 (Figure 1). In 2019, the lowest number was 8.36% in Romania and the highest was 90.78% in Denmark. In 2023, Romania stays in bottom position with a value of 21.89% (despite an almost threefold rise) and Denmark in first place with a value of 96.22% (a less than 6% increase).

Figure 1.

Average percentage of EU citizens with internet-related digital skills between 2019 and 2023. Source: processed according to EUROSTAT data (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database) (accessed on 4 August 2024) (Eurostat 2023a, 2023b).

At the same time, the average percentage of EU citizens who utilized the internet to buy goods and services increased significantly, from 63.19% in 2019 to 69.6% in 2023 (Figure 1). In 2023, Bulgaria had the lowest percentage of internet users buying goods and services (45.19%), while the Netherlands had the most (92.41%). The increasing utilization of the internet in the EU was also reflected in an average increase in the share of persons who used the network on a regular basis from 83.90% in 2019 to 90.27% in 2023. Bulgaria had the lowest percentage of regular internet users in 2023 (79.83%), while the Netherlands had the highest rate (98.92%). Romania (23.04%) and Bulgaria (19.43%) experienced the fastest increases in internet adoption rates between 2019 and 2023.

During the same period, the most significant rise in digital abilities to utilize the internet was for telephony and video calls, from 51.97% in 2019 to 68.80% by 2023. Similarly, we see a slightly lower increase in the percentage of persons using the internet to participate in social networks (making user profiles, posting messages or other contributions to Facebook, Twitter, etc.) from 54.16% in 2019 to 59.31% in 2023 (Figure 1).

The move to online activities has put a strain on individuals’ digital skills. As businesses become more digital, employees must possess fundamental software skills. The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have had an impact on the variables used in our analysis, and examining them may shed light on labour market shifts. From the large number of statistical variables used in practice, such as employment rate, productivity, and income, we chose the average hourly salary as an indicator to measure labour market performance. Wage and salary costs are defined by Eurostat as direct remunerations, bonuses, and allowances paid by an employer in cash or in kind to an employee in exchange for work performed, payments to employee savings schemes, payments for days not worked, and remunerations in kind such as food, drink, fuel, and company cars (Eurostat 2020).

The average hourly income is often used as an indication of the labour market’s structural performance because it gives a quantifiable, basic measure of how much workers earn per hour and can be used to examine wage changes over time. Although it is not a perfect measure of labour market performance, because it does not capture wage inequality or distribution and it does not account for job quality or the number of hours worked, this indicator is simple to evaluate, follow, and compare throughout time, industries, and different countries. It gives a clear picture of pay patterns and is connected to major economic indicators such as labour demand, consumer expenditure, and policy choices. Given the fact that there are still significant differences in salaries across EU member states for the same job categories (Maarek and Moiteaux 2021) and because the COVID-19 pandemic had a relatively limited impact on average wages (ILO Global Wage Report 2020), we consider that the average hourly salary is a reasonable indicator of the labour market’s performance for our analysis (Global Wage Report 2020). To perform the analysis, we used IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the main variables.

We employed a Principal Component Analysis (PCA-type factorial analysis) with orthogonal rotation to gain a general understanding of the main components that synthesize the digital capabilities of individuals in the 30 European countries analyzed. Our primary goal was to decrease the dimensionality of our data by reducing the number of variables while retaining essential information, in order to find patterns in the dataset and facilitate the presentation of high-dimensional data (Jolliffe 2002).

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test is an important first step in PCA since it ensures that the variables are sufficiently intercorrelated, suggesting that the dataset is suitable for PCA (Kaiser 1974). High KMO values indicate that PCA can deliver valuable insights without further preprocessing or additional data. The KMO statistic is calculated using the variables’ correlation and partial correlation matrices. It compares the magnitude of observed correlation coefficients with the magnitude of partial correlation coefficients. The dataset’s overall KMO statistic is calculated by averaging the individual KMO values.

The KMO value of 0.830 (Table 2) produced for our dataset is in the range of 0.8 to 0.9, which is pretty close to one, indicating that correlation patterns are quite compact, and hence PCA should provide obvious and reliable components (Hutchenson and Sofroniou 1999).

Table 2.

KMO and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity.

Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity is a statistical test that determines if the correlation matrix is substantially different from an identity matrix. We may infer that the correlations between the variables are significant enough for PCA and reject the null hypothesis based on Bartlett’s Test (Table 2).

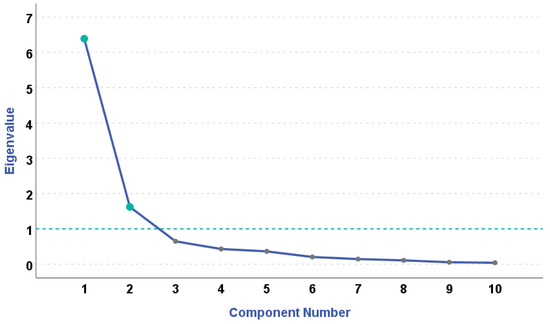

To find the eigenvalues for every element in the dataset, a new analysis was performed. Together, the two components accounted for 80.13% of the total variation (Table 3), with eigenvalues above the Kaiser criteria of 1.

Table 3.

Total variance explained.

We used varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization to capture the factor loadings, and the rotation converged after three iterations. The loadings are made simpler by this procedure, which facilitates the identification of the factors that contribute most to each major component. The purpose of varimax, an orthogonal rotation approach, is to maximize the variation in a factor’s squared loadings across variables in order to make the structure of the factor loadings more interpretable (Browne 2001).

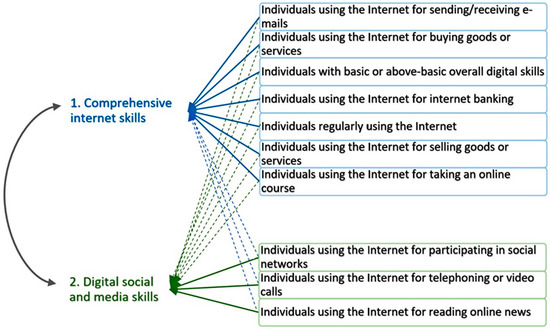

Table 4 shows that the variables were classified into two primary components, namely one for the first seven variables investigated and the other for the last three. Component no. 1 accounts for around 56% of the overall variation associated with the year 2023, whilst component no. 2 accounts for only about 25% (Table 3).

Table 4.

Rotated component matrix.

A scree plot is another helpful tool for determining how many factors best represent a particular dataset (Cattell 1966). In order to conclude how many principal components to keep in our PCA analysis and also to display the percentage of total variance explained by each factor, we created a scree plot (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Scree Plot showing eigenvalues of Principal Components.

The elbow point on the curve, which represents the optimum number of components to retain, validates the two principal components we obtained from the PCA analysis (Figure 2). It shows that adding more than two components to our model does not significantly enhance the variation explained. As a result, we may reduce the dimensionality of our initial dataset from ten to two variables, while retaining more than 80% of the data’s variability.

Using the regression method, the two factors’ scores were generated as new independent variables for additional analysis, since component scores are composite variables that give information about an individual’s location on each factor (DiStefano et al. 2009). This approach stabilizes variable variances and differences in units of measurement by adjusting the factor loadings to account for the initial correlations between variables.

4. Results

Given the considerations presented in the previous section, we will attempt to identify which individual internet-based digital skills are actually relevant and associated with higher wages and salaries in the 2023 Post-pandemic European Labour Market.

As shown in Figure 3, the variables that are grouped on the same components suggest that first factor reflects “Comprehensive internet skills”, and the second factor corresponds to “Digital social and media skills”. Component no. 1 describes the diverse and widespread usage of the internet for communication, economic activity, financial transactions, education, and job-related duties. It also reflects a wide range of online activities, demonstrating a high level of digital literacy and internet utilization. The second component incorporates the common theme of using the internet for numerous forms of communication and information consumption, demonstrating a diverse involvement with digital platforms for interaction with others, communication, and staying updated.

Figure 3.

Path diagram of individual internet-based digital skills.

Next, as part of the study, we will investigate the potential relationship between the two previously generated components (factor scores) and the average hourly wages and salaries for the 30 European countries considered in 2023.

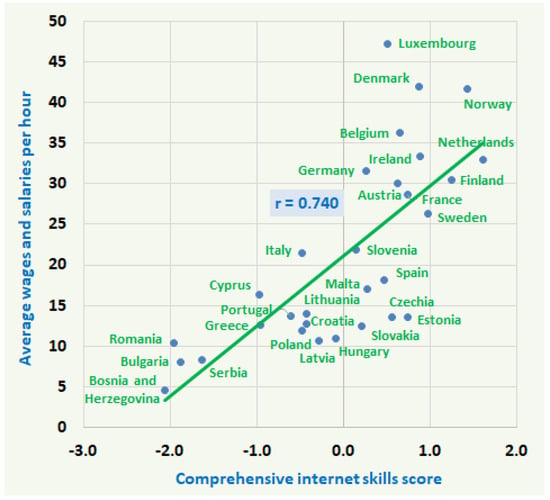

Figure 4 illustrates the correlation between European states wages and salaries and the comprehensive internet skills component score. The graphic representation indicates that the comprehensive internet skills score and average incomes and salaries per hour have significant positive association for the European countries in 2023 (Pearson correlation coefficient: , ). Thus, we observe notable differences between European countries, whereby individuals with comprehensive internet skills also tend to have higher average salaries.

Figure 4.

Comprehensive internet skills score and hourly wages.

Nearly 90% of EU citizens use the internet at least once a week, but only 54% of them have basic or above-basic digital skills in 2021, according to the Eurostat study Digitalization in Europe—2023. In 2021, Iceland (81%), Finland, Norway, and the Netherlands (all 79%) had the highest percentage of individuals in Europe with basic or above-basic digital abilities, compared to 28% in Romania and 31% in Bulgaria (Eurostat 2023a, 2023b).

Nevertheless, a group of EU member states (Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Croatia, Czechia, Slovakia, and Hungary), former communist countries, may have an important advantage in the European labour market because their comprehensive internet skills score is very close to the EU average, despite their earnings being significantly lower than the average wages and salaries (Figure 4).

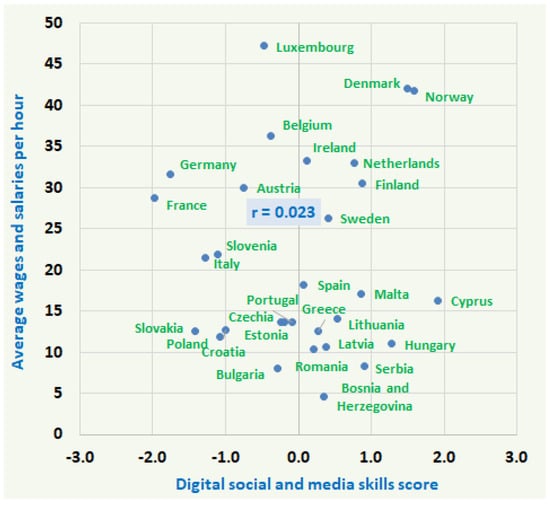

Similarly, we will assess the relationship between digital social and media skills and average hourly salaries in 30 European nations in 2023.

The Pearson correlation coefficient is nearly zero in Figure 5, indicating that there is no association between the two variables (, ). This graph also indicates that, regardless of average hourly earnings, digital socialization and media skills are roughly the same, with Romania and Bulgaria, for example, ranking similarly to Belgium and Luxembourg in terms of digital score skills but being diametrically opposed on the income scale.

Figure 5.

Digital social and media skills score and hourly wages.

The first explanation might be the widespread access to the internet: Internet access has expanded throughout Europe’s various socioeconomic categories. Regardless of financial level, almost everyone utilizes the internet for fundamental tasks like social networking, phone calls, and news reading.

Individuals, on the other hand, engage in these activities for a variety of reasons other than financial gain. For example, social networking can be used for personal, professional, or educational goals. Higher-income people may utilize video calls and read online news for professional reasons, but lower-income people may do so for personal reasons, making these behaviours common across income ranges.

In the third line, most individuals in Europe may access these internet activities at a minimal cost, lessening the possibility of a direct correlation with income. At the same time, cultural variables, such as the significance of staying connected or being informed, define internet usage patterns rather than economic levels.

Consequently, these behaviours are widely practised across all income levels due to a variety of goals and cultural considerations, making them poor markers of economic position. The extensive and diverse usage of the internet for various reasons dilutes any potential direct association to income levels, which explains why no meaningful relationship exists.

We can thus confirm that a wide range of digital skills and internet usage, which make up the first component “Comprehensive internet skills”, are highly correlated with the average hourly wage in Europe in 2023. These skills and usage include e-mail sending and receiving, online banking, online purchases and sales of goods and services, regular internet use, online course enrollment, and job searching. We also emphasized the lack of correlation between wages and salaries in Europe in 2023 and the component “Digital social and media skills”, which comprises the following variables: people using the internet for social network participation, people using the internet for phone or video calls, and people using the internet for reading online news.

5. Discussion

According to Eurostat research, digital skills are becoming increasingly important for a wide range of occupations, resulting in improved productivity and efficiency in the workplace, which finally might lead to higher wages and salaries (Eurostat 2023a, 2023b). The pandemic-induced acceleration of the digitalization process, owing to remote learning, telecommuting, or a growing inclination of numerous businesses to shift to virtual operations in order to fulfill customer demands and stay afloat, opened up new avenues for employee and entrepreneurial growth (Filipeanu et al. 2024).

Human capital will need to quickly adapt due to the rapid speed of technological advancements, which includes the emergence of AI technologies and the requirement for digitalization in terms of both infrastructure and skills. Certain segments of the population, including the elderly or those with poor skill levels, will find it challenging to keep up in this digitally advanced environment (Feyer 2024). According to the Digital Economy and Society Index, a third of European workers and four out of ten adults do not possess fundamental digital skills (European Commission 2022). Support measures that proved effective in addressing the challenge of rapid technological development and digital upskilling/reskilling included the following: methods to evaluate and raise the digital maturity of educational institutions at different levels; digital transformation incorporated into curriculum reforms; and methods to upskill and reskill the digital needs of different population categories, including adults with low skill levels (Feyer 2024).

Our idea of finding those skills necessary for an employee to be able to obtain a higher salary is not exactly a new idea, but it has been explored by in many studies (Smaldone et al. 2022; Jandrić and Ranđelović 2018). Due to the wide range of professions available on the labour market, it can be challenging to categorize jobs based on the skill requirements that they require, as they often overlap (Ao et al. 2023). For example, as big data becomes more complicated and diverse, data scientists are expected to make sense of these enormous repositories of information. This position is changing concurrently with today’s rapid technology development and its use in an increasing number of industries. “Specific capabilities to perform a particular job” is how Cimatti described hard skills (Cimatti 2016). Hard skills rely on training and job experience since they are practical abilities that can be acquired via study and practice.

While the hard skills needed for many jobs vary, for a data scientist, these can involve using certain equipment, working with data in a systematic manner, using pertinent software, developing software, or programming, knowledge of statistics, quantitative analysis, proficiency with a range of analytical, statistical, and modelling tools, or knowledge of a particular industry (Wang et al. 2022; Lyu and Liu 2021).

It is true that a variety of complementing soft skills have also been determined to be crucial in the setting of a career, in addition to these multidisciplinary hard abilities (Ao et al. 2023). Therefore, it is critical to emphasize the value of human abilities because robots will never be able to replace those. A balanced mastery of hard, digital, and soft skills is necessary for people to prosper in a technologically advanced future (Poláková et al. 2023).

A term that is frequently used yet hotly contested, “soft skills” refers to the entirety of a person’s innate traits that are inextricably related to their personal characteristics and are extremely valuable in any line of work. “Dealing with others and managing oneself and one’s emotions in a manner consistent with particular workplaces and organizations” is how they are put to use (Hurrell et al. 2013). As such, it is challenging to characterize soft skills in terms of a comprehensive idea. However, research has begun to indicate that common core soft skills—like initiative, leadership, problem solving, communication, self-control, knowledge, ambition, and ethics—might be grouped under the skills categories of learning and innovation, digital literacy, and life and career (Hirsch 2017; Alvarez and Alvarez 2018).

Our main finding that comprehensive internet skills correlate with higher wages while digital social and media skills do not is interesting. We found that in 2023, the European labour market placed a larger value on comprehensive internet skills since they align with the demands of quickly increasing, high-paying industries that require sophisticated digital competencies, such as technology, finance, and engineering. These abilities are more difficult to automate and need more formal training, making them rare and precious. Digital social and media skills, on the other hand, while necessary for some positions, are more prevalent, possibly less valuable economically, and frequently connected with sectors or gig-based labour (freelance social media managers, influencers, content creators) with lower compensation (Massingham and Tam 2015; Newlands and Lutz 2024). In the last ten years, the specialized literature has emphasized a substantial association between people’ digital abilities and professional success. Employees with a higher level of digital competence are more productive in their careers because they can use digital tools to complete tasks, solve issues, and innovate. The capacity to handle information, communicate efficiently, and cooperate utilizing digital platforms is recognized to be essential for productivity in the modern workplace (Van Laar et al. 2019; Bukht and Heeks 2018).

Our findings are consistent with those of other similar studies, namely strong positive relationships between Web usage and salary growth, indicating that specific digital skills correlated with internet use were valued by the labour market (Piroșcă et al. 2021; DiMaggio and Bonikowski 2008).

We chose PCA over other potential methods, such as factor analysis or structural equation modelling, because the goal of our analysis was to simplify a large set of digital skills into key components for further analysis, and the focus of the research was to explain the variance in digital skills that most closely relates to salaries and wages. Because the seven core digital abilities integrated in the comprehensive internet skills component are mostly found in persons with expertise in software development or IT-related activities, current and future opportunities in this dynamic sector are quickly expanding. With their competitive advantages in the labour market—with digital and internet skills above the EU average, and low wages—countries like Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Croatia, Czechia, Slovakia, and Hungary are seeing a significant increase in outsourcing activities, especially in fields like IT and call centres (Popelo et al. 2021). Thus, multinational firms especially have an opportunity given the constant need to reduce costs in order to increase profit margins by carrying out diverse operations in countries with much lower wage levels but with competent labour. Figure 4 depicts the cluster of seven Eastern European countries that could benefit from this obvious competitive advantage (comprehensive internet skills component) through more efficient integration into the EU labour market and, as a result, the possibility of higher incomes in the near future.

In 2021, Non et al. investigated the demographics of individuals with varying degrees of digital proficiency and connected digital proficiency to employment outcomes in the Netherlands. They discovered that people with poor digital skills are typically older, less educated, and more likely to be female. Additionally, a one standard deviation gain in digital abilities is linked to a four to six percent increase in wage. Due to their higher labour force participation rate, those with at least basic skills have a ten percent higher employment chance than people without any digital abilities (Non et al. 2021). In the above-mentioned study, the skill exam assessed the respondents’ abilities in the areas of problem solving in technologically advanced settings, reading, and numeracy between 2012 and 2019. The long-term stability of the relationship between digital skills and employment and salary suggests that the abilities acquired in 2012 have a lasting impact on labour market results.

A vast range of actions and procedures targeted at using digital platforms to promote goods, services, or brands are collectively referred to as “digital marketing”. Experts in digital marketing are in great demand and can fetch significant compensation, being a good example of a positive correlation between comprehensive internet skills and salary. Enrolling in an online course or certification programme is one approach to advancing your knowledge of digital marketing. Digital marketing courses are widely available from respectable universities to help workers acquire the abilities required for success in this industry (https://persuasion-nation.com/is-digital-marketing-a-high-income-skill/, accessed on 24 September 2024).

The digital economy has transformed many elements of life, including communication, information access, and social interaction. Despite these improvements, as we showed in our article the second component, digital social and media skills and wages and salaries in Europe in 2023 clearly do not correlate. Helsper and Eynon argue that digital social and media skills, which include using the internet for social networking, communication, and information consumption, fall primarily into the category of personal digital skills rather than professional ones (Helsper and Eynon 2010). Van Deursen and Van Dijk elaborate on this distinction, claiming that the abilities necessary for efficient internet use in everyday life do not always transfer into increased productivity or performance in job environments (Van Deursen and Van Dijk 2014). Hargittai highlights the challenges of effectively evaluating digital skills in the context of measurement and data limitations. The author concludes that surveys frequently lack the precision required to distinguish between different types of social media abilities and their unique impacts on economic results for different reasons such as biases in data collection, demographic disparities, and underrepresented groups (Hargittai 2020).

Comprehensive internet skills, our first analyzed component, may be included in digital marketing components and skills and we found a correlation between European states wages and salaries and the comprehensive internet skills component score. Utilizing social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to engage with your target market and advertise your goods or services is known as social media marketing. We consider that, unless these abilities are applied to marketing, there is no relationship between wages and salaries in Europe in 2023 and the component “Digital social and media skills”. The future workforce will be better prepared to meet the demands of the current labour market, attain professional goals, and live up to the expectations of the next generation if comprehensive internet skills development is given priority in secondary schools and colleges (European Commission 2023).

The novelty of our research lies in its specific focus on the unique and immediate impacts of the pandemic, the accelerated adoption of digital skills, the integration of comprehensive individual internet skills, and the use of most recent data to understand the labour market’s present characteristics. This new approach offers fresh insights into how Europe’s workforce could evolve in response to unprecedented challenges, making it distinct from previous studies of labour market skills.

Limitation of the Study

We are aware of the following limitations in the research. First and foremost, the use of a constrained dataset was forced by the availability of information at the Eurostat database level for 2023. Nevertheless, we think that the selected dataset adequately captures the phenomena of digitalization and labour market characteristics in all 30 European countries analyzed. Because there are significant differences in sampling methodology between national statistical institutes in European countries that report to EUROSTAT, we expect possible biases in internet usage statistics. Second, the PCA approach only provides a cross-sectional perspective of a very dynamic process of integrating digitalization into all socioeconomic areas of modern life. Furthermore, the possibility of confounding variables exists. It is difficult to rule out other reasons for the observed relationships in the absence of longitudinal data. Reverse causality is also more likely when systematic temporal analysis is lacking. To make a stronger case for causality, a longitudinal design or time series data could be considered.

6. Conclusions

This research fills a knowledge gap by identifying which skills are essential in the new labour market, allowing politicians, educators, and companies to realign workforce development plans to meet rising demands. This contributes to ongoing debates about the future of work by emphasizing the importance of upskilling and reskilling workers in order to adapt to a technologically sophisticated labour market. Policymakers and organizations might utilize these data to develop targeted training campaigns and invest in digital infrastructure. They are also likely to emphasize the need for further investment in lifetime learning and digital education programmes. Our study also provides valuable insights on the future of European labour mobility and cross-border employment, assisting workers and companies in managing the complexity of international employee recruitment and workforce distribution in the post-pandemic period.

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the growth of remote employment, making internet skills more important than ever. Individuals with robust internet and digital skills have more access to a wider variety of employment options, which often come with competitive salaries. Employees with internet abilities can use digital tools and platforms to increase efficiency and productivity. This frequently involves the extensive use of the internet for financial transactions, business, education, and communication, as well as for job-related tasks.

Since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have observed an important shift in the impact of digital and internet skills on the job market in Europe (Helsper and Eynon 2010). Thus, the more efficient integration of individuals into the labour market in Europe in general, and the EU in particular, as reflected by higher salary levels, is strongly associated with the development of comprehensive internet skills. On the other hand, as a novel aspect of our study, we found no correlation between the possibility of obtaining higher salaries for employees and the second component, digital social and media skills, which essentially include using the internet for a variety of forms of communication such as social networks, telephoning, video calls, and reading online news.

Our research also identifies a well-defined cluster of countries, namely Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Croatia, Czechia, Slovakia, and Hungary, that have a significant competitive advantage in the EU labour market due to relatively low salaries and a level of digital skills that is very close to the EU average. This aspect indicates the possibility of intensifying some regional discrepancies in the future, which could significantly affect the composition and functioning of the EU labour market. The workforce’s lack of adaptability can be a major barrier to future growth and development in some other nations. New data from future studies may reveal whether certain countries have made progress and what areas of worker adaptation need more attention.

There still remain numerous unknown elements in the context of the recently ended crisis, but we can conclude that employees and human resources should have the essential abilities to quickly adjust to change. Individuals who will not be able to adapt to these major changes, who lack the digital skills necessary to facilitate remote work, are typically the majority in terms of weight among people without a college education, with a low average income, and with poor use of internet resources, and who may become a vulnerable segment of the general population (Mongey and Weinberg 2020).

European economies’ competitiveness, resilience, and productivity were all impacted by the rise in digital skills as the new currency. The acquisition of comprehensive internet skills could perhaps encourage individuals who are not currently employed to re-enter the workforce. Even if we are unable to establish causation, we can nevertheless suggest comprehensive online skills training to those who wish to increase their income. Our findings also clearly justify the need for more controlled studies and research on the impact of skills training.

Our study’s practical implications primarily include offering decision makers with a clear view of the key issues to improve when developing and implementing the second digital agenda for Europe in the context of 2030.

In future research, we plan to broaden the scope of our investigation of the effects of digitalization on the labour market by employing a dynamic panel analysis that more accurately reflects this extremely complex phenomena that shapes our future and is becoming an increasingly important part of our lives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.Ț. and F.-A.L.; methodology, V.Ț. and E.Ț.; investigation, V.Ț. and F.-A.L.; validation, V.Ț. and E.Ț.; writing—original draft preparation, V.Ț. and E.Ț.; writing—review and editing, V.Ț. and F.-A.L.; visualization, V.Ț. and F.-A.L.; supervision, V.Ț. and E.Ț. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alvarez, Sally M., and Jose F. Alvarez. 2018. Leadership development as a driver of equity and inclusion. Work and Occupations 45: 501–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Ziqiao, Gergely Horváth, Chunyuan Sheng, Yifan Song, and Yutong Sun. 2023. Skill requirements in job advertisements: A comparison of skill-categorization methods based on wage regressions. Information Processing & Management 60: 103185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulsamy, A. S., Indira Singh, M. Senthil Kumar, Jetal J. Panchal, and K. K. Bajaj. 2023. Employee Training and Development Enhancing Employee Performance—A Study. Reseachgate Net 16: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, Amy, Gwen Shaffer, and Todd Wolfson. 2013. Digital Human Capital: Developing a Framework for Understanding the Economic Impact of Digital Exclusion in Low-Income Communities. Journal of Information Policy 3: 247–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergson-Shilcock, Amanda. 2020. The New Landscape of Digital Literacy: How Workers’ Uneven Digital Skills Affect Economic Mobility and Business Competitiveness, and What Policymakers Can Do about It, National Skills Coalition. Available online: https://nationalskillscoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/05-20-2020-NSC-New-Landscape-of-Digital-Literacy.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Bessen, James. 2019. Artificial Intelligence and Jobs: The Role of Demand, the Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-61347-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, Jeremy. 2014. The Computerisation of European Jobs. Brussels: Breughel. Available online: http://bruegel.org/2014/07/the-computerisation-of-european-jobs/ (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Browne, Michael W. 2001. An Overview of Analytic Rotation in Exploratory Factor Analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research 36: 111–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brucks, Melanie S., and Jonathan Levav. 2022. Virtual communication curbs creative idea generation. Nature 605: 108–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukht, Rumana, and Richard Heeks. 2018. Digital Economy Policy in Developing Countries. Manchester: Centre for Development Informatics, Global Development Institute, SEED, University of Manchester. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, Raymond B. 1966. The Scree Test for The Number of Factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research 1: 245–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Tsz Hang. 2020. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and employee outcomes. Telematics and Informatics 50: 101379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimatti, Barbara. 2016. Definition, development, assessment of soft skills and their role for the quality of organizations and enterprises. International Journal for Quality Research 10: 97–130. [Google Scholar]

- Colbert, Amy, Nick Yee, and Gerard George. 2016. The digital workforce and the workplace of the future. Academy of Management Journal 59: 731–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, Lucas, Katja Brøgger, Mieke Berghmans, Mathias Decuypere, Annina Förschler, Emiliano Grimaldi, Sigrid Hartong, Thomas Hillman, Malin Ideland, Paolo Landri, and et al. 2022. Pandemic Acceleration: COVID-19 and the emergency digitalization of European education. European Educational Research Journal 21: 845–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, Davide, Fulvio Castellacci, and Artur Santoalha. 2023. E-skills and income inequality within European regions. Industry and Innovation 30: 919–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan, Georgiana-Alina, Madalina Ecaterina Popescu, Eva Militaru, and Amalia Cristescu. 2023. EU Diversity in Terms of Digitalization on the Labour Market in the Post-COVID-19 Context. Economies 11: 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, Paul, and Bart Bonikowski. 2008. Make Money Surfing the Web? The Impact of Internet Use on the Earnings of U.S. Workers. American Sociological Review 73: 227–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, Christine, Min Zhu, and Diana Mîndrilă. 2009. Understanding and Using Factor Scores: Considerations for the Applied Researcher. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation 14: 20. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2022. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/desi (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- European Commission. 2023. Digital Skills and Jobs, Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. October 10. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-skills-and-jobs (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Eurostat. 2020. Labour Cost Levels by NACE Rev. 2 Methods and Definitions. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/Annexes/lc_lci_lev_esms_an_1.docx (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Eurostat. 2023a. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Eurostat. 2023b. Digitalisation in Europe—2023 Edition. ISBN 978-92-68-04421-6. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/digitalisation-2023 (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Evangelista, Rinaldo, Paolo Guerrieri, and Valentina Meliciani. 2014. The economic impact of digital technologies in Europe. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 23: 802–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, Michele, Linjuan Rita Men, and Julie O’Neil. 2019. Using social media to engage employees: Insights from internal communication managers. International Journal of Strategic Communication 13: 110–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyer, Ciresica. 2024. Reinventing Skills—Changing Paradigms and the EU Response. Intereconomics 59: 132–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipeanu, Dumitru, Florin Alexandru Luca, Liviu-George Maha, Claudiu Gabriel Țigănaș, and Viorel Țarcă. 2024. The nexus between digital skills’ dynamics and employment in the pandemic context. Eastern Journal of European Studies 14: 245–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, Martin. 2015. Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future. New York: Basic Books, a Member of the Perseus Books Group. ISBN 978-0-465-05999-7. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, Carl Benedikt, and Michael A. Osborne. 2017. The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114: 254–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Wage Report 2020–21. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_762534.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Gnecco, Giorgio, Sara Landi, and Massimo Riccaboni. 2024. The emergence of social soft skill needs in the post COVID-19 era. Quality & Quantity 58: 647–80. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorescu, Adriana, Elena Pelinescu, Amalia Elena Ion, and Monica Florica Dutcas. 2021. Human Capital in Digital Economy: An Empirical Analysis of Central and Eastern European Countries from the European Union. Sustainability 13: 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, Richard, Andrew Rohm, and Victoria L. Crittenden. 2011. We’re all connected: The power of the social media ecosystem. Business Horizons 54: 265–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, Eszter. 2020. Potential Biases in Big Data: Omitted Voices on Social Media. Social Science Computer Review 38: 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, Ellen Johanna, and Rebecca Eynon. 2010. Digital natives: Where is the evidence? British Educational Research Journal 36: 503–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, Barton J. 2017. Wanted: Soft skills for today’s jobs. Phi Delta Kappan 98: 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, Scott A., Dora Scholarios, and Paul Thompson. 2013. More than a ‘humpty dumpty’ term: Strengthening the conceptualization of soft skills. Economic and Industrial Democracy 34: 161–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchenson, Graeme, and Nick Sofroniou. 1999. The Multivariate Social Scientist. London: Sage Publications Ltd. ISBN 9780761952015. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Kathryn, Christi L. Lower, and William J. Rudman. 2016. The Crossroads between Workforce and Education. Perspectives in Health Information Management 13: 1g. [Google Scholar]

- Jandrić, Maja, and Saša Ranđelović. 2018. Adaptability of the workforce in Europe—changing skills in the digital era. Zbornik Radova Ekonomskog Fakulteta u Rijeci 36: 757–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, Ian T. 2002. Principal Component Analysis, 2nd ed. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-95442-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, Henry F. 1974. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39: 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacová, Zaneta, Ivana Kuráková, Maria Horehájová, and Anna Vallušová. 2022. How is digital exclusion manifested in the labour market during the COVID-19 pandemic in Slovakia? Forum Scientiae Oeconomia 10: 129–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Neil, and Stephen Clarke. 2019. Do low-skilled workers gain from high-tech employment growth? High-technology multipliers, employment and wages in Britain. Research Policy 48: 103803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Zongchao. 2016. Psychological empowerment on social media: Who are the empowered users? Public Relations Review 42: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Wenjing, and Jin Liu. 2021. Soft skills, hard skills: What matters most? Evidence from job postings. Applied Energy 300: 117307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maarek, Paul, and Elliot Moiteaux. 2021. Polarization, employment and the minimum wage: Evidence from European local labour markets. Labour Economics 73: 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massingham, Peter R., and Leona Tam. 2015. The relationship between human capital, value creation and employee reward. Journal of Intellectual Capital 16: 390–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey Global Institute. 2021. The Future of Work after COVID-19. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19 (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Mongey, Simon, and Alex Weinberg. 2020. Characteristics of Workers in Low Work-from-Home and High Personal-Proximity Occupations. Chicago: Becker Friedman Institute. Available online: https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/BFI_White-Paper_Mongey_3.2020.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Moqbel, Murad, Saggi Nevo, and Ned Kock. 2013. Organizational members’ use of social networking sites and job performance: An exploratory study. Information Technology & People 26: 240–64. [Google Scholar]

- Newlands, Gemma, and Christoph Lutz. 2024. Mapping the prestige and social value of occupations in the digital economy. Journal of Business Research 180: 114716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Minh Hao, Eszter Hargittai, and Will Marler. 2021. Digital inequality in communication during a time of physical distancing: The case of COVID-19. Computers in Human Behavior 120: 106717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Non, Marielle, Milena Dinkova, and Ben Dahmen. 2021. Skill Up or Get Left Behind? Digital Skills and Labour Market Outcomes in The Netherlands. CPB Discussion Paper 419. The Hague: CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Piroșcă, Grigore Ioan, George Laurențiu Șerban-Oprescu, Liana Badea, Mihaela-Roberta Stanef-Puică, and Carlos Ramirez Valdebenito. 2021. Digitalization and Labour Market—A Perspective within the Framework of Pandemic Crisis. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16: 2843–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poláková, Michaela, Juliet Horváthová Suleimanová, Peter Madzík, Lukáš Copuš, Ivana Molnárová, and Jana Polednová. 2023. Soft skills and their importance in the labour market under the conditions of Industry 5.0. Heliyon 9: e18670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popelo, Olha, Iryna Kychko, Svitlana Tulchynska, Zhanna Zhygalkevych, and Olha Treitiak. 2021. The Impact of Digitalization on the Forms Change of Employment and the Labour Market in the Context of the Information Economy Development. International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security 21: 160–67. [Google Scholar]

- Smaldone, Francesco, Adelaide Ippolito, Jelena Lagger, and Marco Pellicano. 2022. Employability skills: Profiling data scientists in the digital labour market. European Management Journal 40: 671–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Yu, Chenfei Qian, and Susan Pickard. 2021. Age Related Digital Divide during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 11285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strachan, Sarah, Alison Greig, and Aled Jones. 2022. Going Green Post COVID-19: Employer Perspectives on Skills Needs. Local Economy 37: 481–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundblad, Martin, and Marianne Kolding. 2022. Developing the Right Technology Skills: Using SORT to Support Career Choices for Young People. TECH SUPPLIER Feb 2022—Market Note—Doc # EUR148851222. Needham: IDC Corporate. [Google Scholar]

- Śmiałowski, Tomasz, and Luiza Ochnio. 2019. Economic context of differences in digital exclusion. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum 18: 119–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, Lam Quynh Tran, Herdon Miklós, Dai Phan Thich, and Tuan M. Nguyen. 2023. Digital skill types and economic performance in the EU27 region, 2020–21. Regional Statistics 13: 536–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deursen, Alexander J., and Jan A. Van Dijk. 2014. The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media & Society 16: 507–26. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laar, Ester, Alexander J. Van Deursen, Jan A. Van Dijk, and Jos De Haan. 2019. Determinants of 21st-century digital skills: A large-scale survey among working professionals. Computers in Human Behavior 100: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Wei, Zhen He, Min Zhang, and Baofeng Huo. 2022. Well begun is half done: Toward an understanding of predictors for initial training transfer. European Management Journal 40: 247–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. 2023. The Future of Jobs Report. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2023/ (accessed on 5 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).