Abstract

In this study, we elucidate the income redistribution effects of the proposal to incorporate the Bend Points mechanism of the U.S. OASDI into the Korean National Pension Scheme (BP-KNPS Proposal) through a micro-simulation analysis using individual data from the Korean Labor and Income Panel Study (KLIPS). In addition to examining the effects of introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal into the current National Pension Scheme (NPS), we also consider the impact of this scheme being combined with the 5th National Pension Comprehensive Plan (Draft), announced by Korea’s Ministry of Health and Welfare on 30 October 2023. When the BP-KNPS Proposal is introduced into the current NPS, the Mean Log Deviation (MLD) of the net transfer amount (lifetime pension benefits minus lifetime pension contributions) for regular employees decreases from 0.2022863 to 0.1929960. Similarly, the MLD for self-employed and irregular workers decreases from 0.2046127 to 0.1721433, indicating a reduction in income inequality. Furthermore, when the BP-KNPS Proposal is combined with the 5th National Pension Comprehensive Plan (Draft), the effects are mixed. The proposals to increase the pension contribution rate and adjust the rate increase speed via generation lead to a reduction in income inequality compared to the current NPS when combined with the BP-KNPS Proposal. However, the proposals to raise the pensionable age result in increased income inequality, similar to the outcomes under the current system. This finding suggests that the triple burden identified by literature review—the reduction in benefits due to disparities in contribution periods and life expectancy, and the raised pensionable age—has a greater impact on low-income participants than the inequality-reducing effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal.

1. Introduction

The environment surrounding the public pension system of South Korea (hereinafter, Korea) can be described as extremely challenging. The underlying factors include the rapidly increasing elderly dependency ratio (Korea’s old-age dependency ratio is projected to reach 72.4% by 2050 (OECD 2018)), severely low birth rate (Korea’s total fertility rate for 2023 was recorded at 0.72 (Statistics Korea 2024b)), and high elderly poverty rate (Korea recorded a rate of 31.4% (age: 66–75) and 52% (age: over 75), the highest among OECD member countries, significantly exceeding the OECD averages of 12.5% for those aged 66–75 and 16.6% for those aged over 75 (OECD 2023)). Amid these conditions, discussions focused on reforming the National Pension Scheme (NPS), the core of Korea’s public pension system, began in earnest in August 2022. On 30 October 2023, the government announced the 5th National Pension Comprehensive Plan (Draft) (hereinafter, 5NPCPD), and the proposed reforms were submitted to the National Assembly.

However, the 5NPCPD is based on the financial projections of the 5th National Pension Financial Estimate Results (Ministry of Health and Welfare 2023b), which made strong assumptions about individual contributors without considering detailed income distributions among individuals. This proposal reflects the Yoon Suk-yeol administration’s strong focus on “stabilizing pension finances.” At the same time, the high elderly poverty rate in Korea underscores the growing importance of the “income redistribution function” of the NPS, given that pension income constitutes a significant portion of elderly incomes. However, the 5NPCPD, aimed primarily at pension financial stabilization, offers limited income redistribution effects. In fact, some proposals, such as raising the pension eligibility age, have been shown to widen pension income disparities in net transfers (the difference between lifetime pension benefits and lifetime contributions) among pension participants (J. Park 2024). The purpose of this study is to clarify the effects of the proposal to incorporate the Bend Points mechanism of the U.S. OASDI into the Korean NPS (BP-KNPS Proposal) as a policy recommendation to strengthen the income redistribution function of the Current National Pension Scheme (CNPS) and the 5NPCPD.

The 5NPCPD, similar to the reforms in 1998 and 2007, remains within the scope of parametric pension reform, such as adjusting contribution rates and pensionable ages. Recently, however, numerous studies have pointed out the limitations of parametric pension reform and emphasized the necessity of structural pension reform. This study proposes a BP-KNPS Proposal to enhance the income redistribution function of the NPS as part of a structural pension reform. The main objective of this study is to assess the impact of introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal on intergenerational and intragenerational income redistribution, reflecting the heterogeneity of individual contributors across different genders, employment types, and income levels.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we present an overview of the CNPS and the 5NPCPD, followed by a review of the related literature. In Section 3, we explain the structure of the NPS and the structure of the BP-KNPS Proposal proposed in this paper. In Section 4, we introduce the income redistribution indicator used in this paper and explain the measures taken to reflect the disparities in pension participation periods and life expectancy across income groups. In Section 5, we explain the data and the estimation methods using the BP-KNPS Proposal. In Section 6, we analyze the simulation results of the BP-KNPS Proposal’s income redistribution effects. In Section 7, we provide conclusions and policy recommendations for advancing the 5NPCPD.

2. Background

2.1. The CNPS and the 5NPCPD

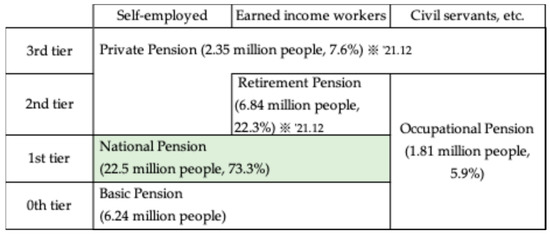

Korea’s public pension system comprises four components—the National Pension and Occupational Pensions for civil servants, private school teachers, and military personnel—as depicted in Table 1. The National Pension, Private Pension, Retirement Pension, and Basic Pension were introduced in 1988, 1994, 2005, and 2014, respectively, ostensibly creating a multi-layered old-age income security system (see Figure 1). The Basic Pension and National Pension, both public pensions, along with the National Basic Livelihood Security System, which is a form of public assistance, primarily serve the function of old-age income security. At present, while the Basic Pension, Retirement Pension, and Private Pension (including housing and farmland pensions) are developing, there is a need for role allocation and the enhancement of each system (Ryu 2022).

Table 1.

Overview of the Korean public pension system.

Figure 1.

Korea’s multi-tier old-age income security system. Note: The figures in parentheses indicate the number of beneficiaries and the ratio of subscribers to the population aged 18 to 59, with the Basic Pension representing the number of beneficiaries only (as of December 2022). The green color indicates that it is within the scope of analysis in this study. Data source: compiled by the author using (Ministry of Health and Welfare 2023a, p. 3).

Amid these developments, the NPS entered a serious reform trajectory following the establishment of the 5th Financial Calculation Committee under the Ministry of Health and Welfare in August 2022. This was followed by the announcement of the 5th National Pension Financial Estimate Results in March 2023 and the formulation and submission of the 5NPCPD to the National Assembly in October 2023. Public interest in NPS reform has been notably high. Over the past few years, the NPS has become a significant social issue, with widespread public distrust. Extreme views, such as calls for the abolition of the NPS, have also surfaced, resonating with certain population segments. These sentiments are driven by concerns over the financial sustainability and adequacy of benefits due to the rapidly increasing elderly dependency ratio, severely low birth rate, and high elderly poverty rate.

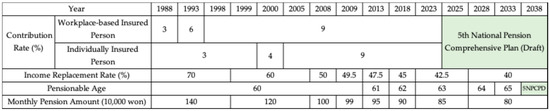

The National Pension Act was revised in 1998 and 2007 to achieve financial stability. The 1998 revision reduced the income replacement rate for a 40-year contribution period from 70% to 60% and raised the pensionable age from 61 in 2013, with annual increments, to 65 by 2033. The 2007 revision further lowered the income replacement rate for a 40-year contribution period from 60% to 50% in 2008, and this has been decreasing by 0.5% annually to reach 40% by 2028. These past reforms focused on reducing benefit expenditures by lowering the income replacement rate and delaying the pensionable age without increasing the contribution rate (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The history of reforms in Korea’s NPS and 5NPCPD. Note: The monthly pension amount assumes 40 years of participation with an average monthly income of KRW 2 million. Contribution rate: for Workplace-based Insured Persons, the rate was 9% at the enactment of the National Pension Act in 1988, 3% for the first 5 years of implementation, and 6% for the next 5 years. For Individually Insured Persons, the rate was initially 3% and increased by 1% each year starting in 2000, reaching 9% by 2005. Income replacement rate: based on 40 years of participation. As of 2018, the average participation period was 23.8 years, with an effective income replacement rate of 23.9%. The green color indicates that it is within the scope of analysis in this study. Data source: compiled by the author using (Ryu 2022, pp. 35–49).

The NPS comprises three types of participants: Workplace-based Insured Persons, Individually Insured Persons, and Voluntarily Insured Persons. Workplace-based Insured Persons include all employers and employees aged 18 to 60 working in companies with at least one employee. This group primarily consists of regular employees, but some irregular employees are also included. The contribution rate is shared equally between employers and employees, with each paying 4.5%. Individually Insured Persons include self-employed individuals, agricultural and fishery workers, and irregular employees residing in Korea, aged 18 to 60, with an income. They are responsible for the full contribution themselves, with a rate of 9%. Lastly, Voluntarily Insured Persons include individuals aged 18 to 60 who do not fall under the categories of workplace or regional participants but choose to join the system, such as homemakers and students (see Table 2). This study focuses on Workplace-based Insured Persons and Individually Insured Persons.

Table 2.

The types of NPS enrollment.

The 5NPCPD, announced on 30 October 2023, focuses on financial stabilization. Indeed, during the deliberation stage of the National Pension Financial Calculation Committee, it was proposed that the sustainability goal for the NPS finances should be to ensure that the reserve fund does not deplete within the financial calculation period (2023 to 2093). For the first time, the draft explicitly includes the fiscal objective of “adjusting to maintain long-term financial balance.” Considering the criticisms over the years regarding the vague financial goals of the pension system, especially in comparison to major overseas countries, this represents a significant step forward (see Table 3). This reform plan aligns with the financial stabilization priority of the Yoon Suk-yeol administration.

Table 3.

A comparison of financial goals in public pension systems in Korea and major overseas countries.

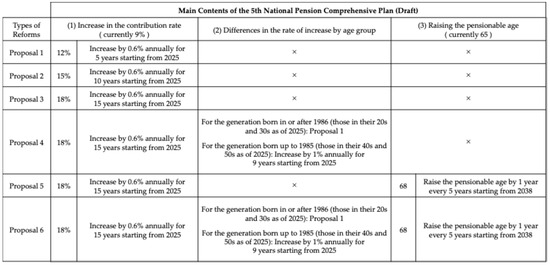

The content of the 5NPCPD includes 18 scenarios combining measures to achieve the newly set financial goals, such as raising the pension contribution rate (to 12%, 15%, and 18%), increasing the pensionable age (from the current 65 to 68), and improving the fund investment return rate (by 0.5%p-1%p above the 5th National Pension Financial Estimate Results). Additionally, it proposes generational equity adjustments to the speed of contribution rate increases (in 2025, the contribution rate for those born after 1986 (in their 20 s and 30 s) will rise by 0.6% annually, while for those born in the years up to 1985 (in their 40 s and 50 s), it will rise by 1% annually).

In this analysis, the National Pension income is assumed to consist solely of pension contributions, excluding other operational revenues and government subsidies. Therefore, excluding the scenarios improving fund investment returns, the analysis focuses on six reform proposals comprising scenarios of raising the pension contribution rate, increasing the pensionable age, and adjusting the generational increase rate, as restructured in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The content of the 5NPCPD used in this paper. Data source: created by the author referencing (Ministry of Health and Welfare 2023a, pp. 48–49).

2.2. The Significance of Income Redistribution in Pension Reform

The significance of considering income redistribution in pension reform, including in this paper, can be understood from two primary perspectives: (i) ensuring social equity and (ii) preventing poverty and promoting social stability. Public pension systems are a form of social insurance that constitutes a crucial element of social security, where “income redistribution” is one of the key functions (Barr and Diamond 2008). The BP-KNPS Proposal adheres to this principle by incorporating an income redistribution mechanism within its framework. This paper examines the current income redistribution function of the system and evaluates the impact of the BP-KNPS Proposal to provide insights that may contribute to achieving objective (i).

Moreover, as highlighted at the beginning of this paper, Korea faces an exceptionally high elderly poverty rate. Considering that pension income constitutes a significant portion of the elderly’s income structure in Korea, it is essential to assess the income redistribution function of the BP-KNPS Proposal from the perspective of (ii). Indeed, numerous previous studies have analyzed the income redistribution effects of the NPS (S. H. Kim 2004, 2019; Kim and Kang 2005; Lee 2006; Kang et al. 2008; Korea Development Institute 2008; Yuh and Yang 2011; Lee et al. 2016; Choi 2016; Choi and Han 2017). However, these studies primarily focus on evaluating the redistribution effects of the NPS and past reform proposals, without extending to policy recommendations. While some studies have proposed policy measures to mitigate pension income disparities among pensioners through other systems, such as the Basic Pension, Retirement Pension, and Private Pension, there has been no prior research that advocates for strengthening the income redistribution function within the NPS itself. This paper uniquely proposes such an approach by enhancing the income redistribution function embedded within the NPS framework.

This paper proposes the BP-KNPS Proposal as part of a strategy to strengthen the essential “income redistribution function” of social security, considering the significance of the NPS as social insurance and the current high elderly poverty rate in Korea. The BP-KNPS Proposal offers two primary advantages: (1) As a reform implemented through the NPS, which has the longest history and is now entering a mature phase compared to other public pension systems, such as the Basic Pension and Retirement Pension, it allows a large majority of the population to benefit from the reform’s effects. (2) Instead of introducing an entirely new system, it enhances the existing income redistribution mechanisms already embedded within the NPS, thereby reducing the administrative burden on the relevant authorities. However, there are potential drawbacks, such as the risk of excessive redistribution dampening labor incentives and the possibility of increased information asymmetry and decision-making costs among participants due to system complexity. Nevertheless, these issues can be addressed through the government’s continuous accountability and efforts to build a social consensus.

2.3. Literature Review

Recent studies on the reform of Korea’s public pension system, including the NPS, highlight the limitations of parametric pension reforms and emphasize the necessity of structural pension reforms. Specifically, these studies can be categorized into three types.

First, some studies advocate for reforms that focus on financial stabilization while maintaining the current income replacement rate of the National Pension (T. Kim 2015; Choi and Kim 2016; Lee and Shim 2018; Seok 2018; Chun 2020).

Secondly, research focusing on increasing the current income replacement rate to strengthen income security through National Pension reforms includes that performed by (Joo 2022). Joo proposes simultaneously enhancing the National Pension and Basic Pension, along with introducing a Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS).

Lastly, there is also research advocating for expanding the role of the Basic Pension, reducing the income replacement rate of the National Pension, and ensuring financial stability. These studies either propose expanding the current Basic Pension (Kim et al. 2016; Tchoe and Kang 2019; Tchoe and Kang 2023) or transitioning the Basic Pension into a new system (Ryu and Kim 2019; Oh 2021; S. Kim 2021).

However, while these previous studies suggest various reform directions, they often do not evaluate the policy effects of the proposed reforms while considering the heterogeneity of actual NPS contributors, such as income distribution, employment types, and disparities in contribution periods and life expectancy across income groups.

In contrast, this study proposes the BP-KNPS Proposal, modeled after the Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) bend points in the U.S, to enhance the income redistribution function of the NPS while maintaining the current income replacement rate and focus on financial stabilization. This paper puts forth a novel reform proposal aimed at enhancing the income redistribution function within the NPS, differentiating itself from prior studies that have adopted an external approach—emphasizing supplemental systems such as the Basic Pension, Retirement Pension, and Private Pension. However, as discussed earlier, these external systems, including housing and farmland pensions, are still in their developmental stages and require further refinement in terms of role definition and integration. In this context, relying on external systems alone to enhance the income redistribution function within the pension system appears impractical. Consequently, this paper proposes the BP-KNPS Proposal as a mechanism to reinforce the income redistribution function within the relatively well-established NPS framework.

The research question of this study is whether, given the current high elderly poverty rate, introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal into the CNPS and the 5NPCPD can simultaneously achieve the government’s goal of pension financial stabilization and strengthen the income redistribution function of pension income. To address this question, this study tests the following three hypotheses:

- Introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal into the CNPS is expected to reduce disparities in old-age pension income among pension participants.

- Introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal into the 5NPCPD is expected to reduce disparities in old-age pension income among pension participants.

- Compared to the CNPS, the 5NPCPD, with the introduction of the BP-KNPS Proposal, is expected to further reduce disparities in old-age pension income among pension participants.

The similarity between the pension systems of the two countries and the superior income redistribution function of the OASDI motivate this proposal. The NPS was designed with advice from the U.S. Social Security Administration, leading to the establishment of the “National Welfare Pension Act” in 1973 and the “National Pension Act” in 1986 (National Pension Service 2008). Choi compares the income redistribution functions embedded in the pension benefit formulas of NPS and the OASDI, finding that the OASDI is much more progressive and effective in terms of income redistribution (Choi 2018).

This study evaluates the income redistribution effect of the BP-KNPS Proposal using the lifetime income of individual contributors. The redistribution effects of social security and tax systems should be evaluated based on lifetime income rather than annual income, as current tax and social insurance contributions offset a significant portion of the redistribution (Haider and Solon 2006; Oshio 2010). Numerous studies have used panel data to estimate lifetime income and analyze the income redistribution effects of their respective pension systems (J. Park 2024; Coronado et al. 2000, 2011; Liebman 2002; Leimer 2004; Levell et al. 2015; Bengtsson et al. 2016; Haan et al. 2017; Xing 2021).

The distinct features of this study compared to previous research include the following:

- When estimating each contributor’s lifetime income, this study individually projects the number of future children and future employment status, incorporating the heterogeneity of contributors. The methodology follows that of J. Park (2024).

- Instead of assuming that all contributors participate in the same period, this study reflects disparities in pension participation periods and life expectancy across income groups, conducting a realistic analysis.

- The analysis distinguishes between employment types (regular employees, self-employed, and irregular employees) among NPS contributors, providing detailed insights.

- This study evaluates the income redistribution effect of the BP-KNPS Proposal alongside the CNPS and the 5NPCPD.

3. Pension Schemes

3.1. The CNPS

3.1.1. Lifetime Pension Benefits

The National Pension’s benefit structure follows a defined benefit model, similar to traditional public pension systems. The pension benefit amount for each participant is determined by the formula in Equation (1), which includes components such as the A value (the flat-rate portion), B value (the earnings-related portion), an actuarial adjustment coefficient, and the contribution period.

To understand the NPS, it is essential to grasp the concept of standard monthly income (SMI). This SMI refers to the amount reported by participants for pension benefit and contribution calculations, rounded down to the nearest thousand Korean won (KRW). The upper and lower limits of the SMI are adjusted annually, reflecting the average income changes of each Workplace-based Insured Person and Individually Insured Person (excluding exempted payers) over the past three years. These adjustments are announced by the Minister of Health and Welfare by the end of March each year and applied, starting in July, for one year. The actual and assumed future values of the SMI used in this study are detailed in Table A2.

The A value (flat-rate portion) in Equation (1) represents the average SMI of all participants over the three years preceding the pension receipt. For instance, the A value, applied from April 2020, is the average of the SMI of all participants from 2017 to 2019, adjusted to 2020 values using the national consumer price index by Statistics Korea (2021). Therefore, the A value reflects both inflation and income growth rates. The predicted values of A used in this study incorporate the assumed real interest rates and real wage growth rates used in the lifetime income estimations.

The B value (earnings-related portion) represents the average annual SMI of each participant during their contribution period, adjusted to the present value. Consequently, the B value is proportional to each participant’s previous labor income. This structure indicates that the NPS includes income redistribution features by calculating the pension benefit amount based on both the average income of all participants (A value) and the participant’s average income during the contribution period (B value).

As seen in Equation (1), the 1998 pension reform adjusted the weights of the A and B values, changing them from a 4:3 ratio to a 1:1 ratio, which reduced the income redistribution function of the pension benefits. The actuarial adjustment coefficient reflects the income replacement rate set by the National Pension Act. Initially, the NPS, introduced in 1988, was designed to guarantee 70% of the lifetime average income for an average-income participant with 40 years of contributions (coefficient of 2.4). However, the 1998 reform reduced the replacement rate to 60% (coefficient of 1.8), and the 2007 reform further reduced it to 50% (coefficient of 1.5) in 2008, with an annual decrease of 0.5 percentage points starting in 2009, to reach 40% (coefficient of 1.2) by 2028.

The contribution period also affects the pension benefit level. As indicated in Equation (1), participants with a 20-year contribution period can receive the full pension benefit amount. Those with contribution periods between 10 and 20 years receive incrementally increasing benefits, starting at 50% for 10 years and increasing by 5% for each additional year beyond 10 years. Participants with contribution periods exceeding 20 years receive more than the full benefit amount.

The pension benefit amount at the start of pension receipt for each participant, calculated from Equation (1), incorporates the aforementioned factors. This amount is then adjusted by reflecting the gender- and cohort-specific average life expectancy derived from the future life tables in the “2021 Life Table” published by Statistics Korea (2022). Using Equation (2), we estimate the lifetime pension amount converted to the present value for each participant. Similar to the approach taken by the National Pension Research Institute, this study excludes survivor benefits from the analysis and focuses solely on the individual’s old-age pension. In this study, the inflation rate () is used to re-evaluate the pension benefit amounts. However, it is important to note that the pension benefit amounts in Korea do not perfectly align with inflation, which requires careful consideration. Apart from this paper, previous studies that have utilized the inflation rate as an index for re-evaluating future pension benefits include (S. H. Kim 2004, 2019; Kim and Kang 2005).

is the pension benefits (monthly) for participant at the commencement of pension receipt (Pension Benefits Begin: PBB); is the total contribution period (months); is the average standard monthly income of all participants for the three years prior to pension receipt (fixed portion); is the average standard monthly income of participant during the contribution period (earnings-related portion); is the contribution period from 1988 to December 31, 1998 (months); is the contribution period from 1999 to 2007 (months); is the contribution period in 2008 (months); is the contribution period from 2009 onwards (months); is the actuarial proportional constant (income replacement rate coefficient); is the years exceeding 20 years of contributions.

is the lifetime pension benefits (monthly) for participant ; is the inflation rate for year (variables employed in revaluation); is the real interest rate (the discount rate) for year ; is the year of death for participant .

3.1.2. Lifetime Pension Contributions

The formula for calculating each participant’s lifetime contributions involves multiplying the SMI for each year by the contribution rate and discounting it to the base year of 2020. For convenience, the formula is structured to discount contributions from the first year of pension enrollment () to 2020 () and from 2021 () to the year before retirement (). As shown in Table 2, regular employees, classified as workplace participants, share the contribution equally with their employers, whereas self-employed and irregular workers, classified as regional participants, bear the entire contribution themselves. Therefore, the formulas are divided into Equation (3) for regular employees and Equation (4) for self-employed and irregular workers.

is the lifetime contributions (monthly) for participant ; is the NPS contribution rate for year ; is the employment status of participant (employed = 1, not employed = 0); is the standard monthly income of participant for year .

3.2. The BP-KNPS Proposal

This study proposes introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal, inspired by the OASDI bend points, to the earnings-related portion (B value) of the pension benefit formula in Equation (1). This proposal is based on the study by (Oshio and Urakawa 2008), which examined the income redistribution effects of introducing the OASDI bend points to Japan’s Employees’ Pension Insurance. In the U.S., the pension amount is calculated using the Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME) converted into the Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) through bend points, with different benefit percentages applied to different AIME ranges. For 2020, the bend points are 90% for AIME up to KRW 960 (first bend point), 32% for AIME between KRW 960 and KRW 5785 (second bend point), and 15% for AIME above KRW 5785 (third bend point) (Social Security Administration (SSA) 2024a, 2024b). This system reduces pension increases for high-income earners, enhancing the income redistribution among participants.

The BP-KNPS Proposal aims to improve income redistribution by setting bend points based on the ratio of Korea’s SMI to the U.S. AIME using 2020 values from the U.S. Social Security Administration and converting the currency at an average exchange rate of KRW 1200 per U.S. dollar (USD) in 2020.

This study excludes survivor pensions and focuses solely on calculating the old-age pension for the individual, following the National Pension Research Institute’s approach.

Next, using the Korean version of Bend Points calculated from Equation (5), each participant’s SMI is divided into three segments, and the new earnings-related portion, the value, is calculated using Equation (6). Then, replacing the B value in the pension benefit formula (Equation (1)) with the new earnings-related portion value, the initial pension amount at the commencement of pension receipt is calculated using Equation (7). Finally, reflecting the gender- and cohort-specific life expectancies derived from the future life tables in the “2021 Life Table” published by Statistics Korea (2022), the lifetime pension amount converted to the present value for each participant is estimated using Equation (8).

is the new earnings-related portion; is the portion of the SMI below KRW 557,226; is the portion of the SMI between KRW 557,226 and KRW 3,357,870; is the portion of the SMI above KRW 3,357,870.

is the lifetime pension benefits (monthly) for participant under the BP-KNPS Proposal.

4. Income Redistribution Measures

4.1. Income Redistribution Index

To assess the income redistribution effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal, this study uses the Mean Log Deviation (MLD). The MLD reflects the characteristic of household income, generally following a log-normal distribution, and is defined as the average deviation of the natural logarithm of income. The MLD reaches a minimum value of 0 when the income distribution is perfectly equal. As a linear measure, it is well-suited for decomposing inequality into contributing factors and is more sensitive to the distribution of low-income groups than other inequality measures.

This study aims to categorize participants into income brackets based on their lifetime earnings and measure pension income disparities among these income groups. In doing so, this research not only focuses on the overall impact of National Pension reforms on income inequality but also investigates the underlying causes of these changes. Since the Gini coefficient, which is commonly used as a measure of income inequality, does not effectively allow for the decomposition of inequality by income group, this study employs the “Mean Log Deviation” (MLD) measure. The MLD enables the identification of each group’s contribution to overall income inequality, making it a suitable metric for this analysis.

Following J. Park (2024), this study examines the income redistribution effects by decomposing the MLD into contributions from changes in intergenerational income disparity (intergenerational redistribution effect) in the first term and changes in intragenerational income disparity (intragenerational redistribution effect) in the second term, as shown in Equation (9). For intragenerational redistribution effects, the MLD is further decomposed within each generational group to assess the effect by income tier. Specifically, intragenerational redistribution effects are decomposed into contributions from changes in the income disparity between income tiers (inter-tier redistribution effect) in the first term and within income tiers (intra-tier redistribution effect) in the second term, as shown in Equation (10). The final expression of the overall income redistribution effect, combining Equations (9) and (10), is given in Equation (11). In this study, generational groups are categorized into four cohorts—those born in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s—while income classes are divided into quintiles.

The variables used in each equation are explained as follows.

is the number of income quintile groups (; first quintile group, second quintile group, third quintile group, fourth quintile group, and fifth quintile group). In this study, income quintiles are classified based on each participant’s lifetime income. is the number of participants belonging to income quintile group (1 = first quintile group, 2 = second quintile group, 3 = third quintile group, 4 = fourth quintile group, 5 = fifth quintile group) in generation group (1 = born in the 1960s, 2 = born in the 1970s, 3 = born in the 1980s, 4 = born in the 1990s). is the total number of participants in generation group . is the net transfer amount for participant belonging to income quintile group in generation group . is the average net transfer amount for income quintile group in generation group . is the average net transfer amount for the entire sample of generation group .

Additionally, when assessing the income redistribution effects of the current NPS and various reform proposals, the MLD is calculated based on the net transfer amount for each participant. The net transfer amount, as used in this study, is defined in Equation (12) as the difference between each participant’s lifetime pension benefits calculated from Equation (8) and their lifetime contributions calculated from Equations (3) and (4).

4.2. Reflecting Disparities in Contribution Periods and Life Expectancy across Income Groups

In this study, to incorporate the heterogeneity of National Pension participants, future predictions of the number of children and employment status were made separately for each participant. Furthermore, this study also reflects disparities in contribution periods and life expectancy across income tiers for each participant.

Firstly, this study utilizes the data on the “Average Contribution Period (months) of National Pension Participation Cases” from the final report of the “In-Depth Analysis of Multi-Layered Old Age Income Security System Using Administrative Data” submitted by the Seoul National University Industry—Academic Cooperation Foundation to the Ministry of Health and Welfare in November 2021 (Ku et al. 2021). These data are used to reflect different contribution periods across income tiers (see Table 4). Specifically, it was assumed that participants in the first income quintile contribute for 10 years, those in the second quintile contribute for 12 years, those in the third quintile contribute for 14 years, those in the fourth quintile contribute for 16 years, and those in the fifth quintile contribute for 20 years.

Table 4.

The average contribution period (months) for cases with an NPS participation history.

Additionally, this study incorporates different life expectancies across income tiers using the average life expectancy data using the income quintile for 2017 presented by Khang et al. (2019). Khang et al. utilized the National Health Insurance Service’s National Health Information Database (NHID), which includes comprehensive data from 2004 to 2017, to present annual average life expectancies by income quintile (at age 0). To calculate annual pension benefits and contributions, this study uses rounded values from Khang et al.’s “Average Life Expectancy by Income Tier” for analytical convenience (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Life expectancy disparities by income tier: actual values for 2017.

5. Data and Methods

5.1. Data and Assumptions in Statistical Analysis

This study uses data from the Korean Labor & Income Panel Study (KLIPS) to understand the National Pension participation history and estimate lifetime income, lifetime pension benefits, and lifetime contributions. The use of KLIPS data is justified by the need to track long-term changes and transitions at the household and individual levels in a dynamic context. Additionally, the availability of various survey items as explanatory variables in the income estimation model makes KLIPS an ideal choice. This study uses data from the first to the twenty-fourth wave of KLIPS.

The sample selection follows the methodology outlined by J. Park (2024) and is based on the following criteria:

- The analysis targets Workplace-based Insured Persons and Individually Insured Persons, excluding those with histories of Occupational Pension.

- The sample includes participants enrolled in the NPS between 2018 and 2020 and aged 25 to 57 as of 2020. The age of 25, the starting age for pension enrollment, follows S. H. Kim (2019), while the age of 57 reflects the scenario of an individual aged 25 in 1988 (the start year of the NPS), who would be 57 in 2020. Therefore, it is assumed that all participants enrolled in the NPS at age 25.

- Participants with a history of receiving National Pension benefits are excluded.

- Foreign workers are excluded due to employment instability and differing employment patterns.

- Participants who changed their employment status during the survey period (e.g., from regular to self-employment or irregular employment) are excluded.

Table 6 summarizes the representativeness analysis of the KLIPS data and the selected sample based on the above criteria. When comparing the number of participants and the sex ratio by participation type with the 2020 data from the National Pension Service (2020) and the KLIPS data, using KLIPS data poses no issues regarding representativeness. Additionally, differences in the ratio of Workplace-based Insured Persons to Individually Insured Persons were not deemed to affect the analysis, as it was conducted separately by participation type.

Table 6.

The number of participants and sex ratio by NPS enrollment type (1997–2020).

Furthermore, this study adopts several assumptions for statistical analysis, following research by J. Park (2024):

- To discount lifetime pension benefits and contributions to the present value, future values of real wage growth, real interest rates, and inflation rates are based on the basic assumptions for population and economy used in the 5th National Pension Financial Estimate Results (see Table A1). Historical real interest rates from 1988 to 2019 are derived by subtracting the consumer price index (CPI) from the nominal interest rates of deposit bank interest rates.

- Individual life expectancy is based on the gender- and cohort-specific life expectancies from the “2021 Life Table” published by Statistics Korea (2022) and is used to estimate lifetime pension benefits.

- The income range analyzed only includes labor income, excluding financial income, secondary job income, and inheritance income.

- The retirement age for regular employees is assumed to be 60, in line with the Elderly Employment Promotion Act, Article 19, Paragraph 1. Self-employed and irregular workers are assumed to work until the year before they start receiving pensions, based on the “Effective Retirement Age” (J. H. Park 2022).

- Residence is assumed to remain unchanged from the last survey response of the household or household member.

- For individuals over 40, the number of children is assumed to remain unchanged, with those above 40 having no additional children. For individuals without data over 40, the number of children is set as of age 39. This study estimates the number of children using KLIPS data instead of assuming that this remains constant from the last survey response, given the importance of the number of children in projecting future individual income. However, following research by H. S. Kim (2007), due to differences in the determinants of the number of children between married women over 40 and those under 40, this assumption is made for analytical convenience.

- Employment type is assumed to remain unchanged during the employment period.

- For the years mentioned in this study, income is considered for the year it was earned (the previous year of the survey), as KLIPS collects income data from the prior year.

- The base year for discounting to the present value is 2020, the latest year for which KLIPS data are available (survey year 2021).

These assumptions are critical for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the statistical analysis and reflecting the real-world conditions and variations among different income groups in studying the BP-KNPS Proposal and its impact on income redistribution.

5.2. Methodology

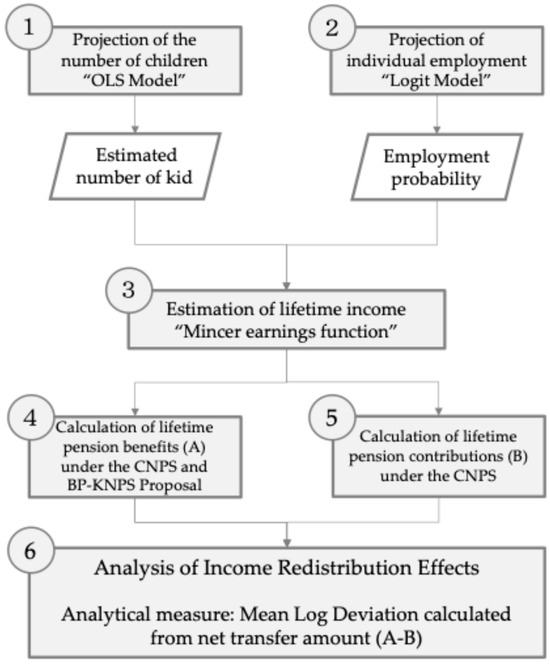

To assess the income redistribution effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal, the following estimations were made. First, using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), the determinants of the number of children each participant will have in the future are estimated, and these estimates are used to predict the future number of children. Next, a Logit Model is employed to estimate the determinants of whether each participant will be employed in the future, and these estimates are used to predict the future employment status. For those predicted to be employed, the Mincer earnings function is utilized to elucidate the relationship between age, tenure, and wage income, segmented by gender and employment type (regular employees, self-employed, and irregular employees). This allows for the prediction of annual wage income from employment to retirement for each participant. These wage predictions are then adjusted for wage growth and discount rates to determine the annual wage levels. Subsequently, the future pension benefits under both the CNPS and the BP-KNPS Proposal, as well as the annual insurance premiums under the CNPS, will be calculated.

The above estimates for future projections follow the methodology outlined in J. Park (2024). The lifetime pension benefits and contributions estimated in this study are theoretical values calculated based on the National Pension benefit and contribution formulas published by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, assuming participants earn the predicted lifetime income. Finally, the Mean Log Deviation (MLD) index is derived to assess income redistribution effects based on the net transfer amount (lifetime pension benefits minus lifetime pension contributions) by gender, employment type, and income group. A summary of this estimation process is illustrated in Figure 4. In summary, in step 4 of Figure 4, the lifetime pension amounts under the CNPS and with the implementation of the BP-KNPS Proposal are estimated. Then, in step 6, the three hypotheses set out in this paper are tested.

Figure 4.

The analysis flow.

Lifetime Income

In this study, the Mincer earnings function is used to predict future income beyond the survey period of the KLIPS, thereby estimating individual lifetime income. Additionally, future predictions for the number of children and employment status are incorporated into the lifetime income estimations.

First, the number of children for married women is estimated. The number of children for husbands in the same household follows the number estimated for their wives. As mentioned in the assumptions made for statistical analysis, it is assumed that no births occur after age 40. For participants over 40 without data, the number of children is set based on their status at age 39. The KLIPS data used in this analysis are detailed when capturing households’ economic situations, as noted by Song (2012), overcoming the limitations of previous studies that relied on the “National Fertility and Family Health and Welfare Survey” by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA), which excluded variables on household economic conditions.

Using OLS, the determinants of the number of children for married women under 39 are modeled, as shown in Equation (13). The number of children for each married woman is determined by variables such as age, employment status, previous year’s labor income (wage or business income), previous year’s household income, and individual attributes (education level, residence in a metropolitan area, and homeownership). The rationale for using the previous year’s labor and household income is that the economic situation immediately before childbirth is a key decision factor, and this study uses the predicted number of children for future income estimations. This allows the use of the predicted values of the previous year’s labor and household income to estimate the future number of children.

is the number of children for married women for year ; is the age of married women for year ; is the employment status of married women for year ; is the labor income (salary income or business income) of married women for year ; is the household income for year (the total labor income of household members, excluding married women); is the attributes of married women (education level, residence in a metropolitan area, and homeownership); is the error term.

Based on the parameters estimated from Equation (13), Equation (14) is derived to estimate the future number of children () for married women under 39 years old.

is the predicted number of children for married women for year .

Next, to analyze workers who make pension contributions, it is necessary to predict whether individuals will continue to be employed after the survey period. Specifically, using a Logit Model, the probability of each participant being employed is estimated from Equation (15). The employment status of each participant is determined by variables, including age and its square, the number of children and its square, household income (the sum of the labor income of household members other than the individual), the population of the city/province of residence, and individual attributes (education level, metropolitan area residence, homeownership, health status, and marital status). In the logit model used in this study, a value of 1 signifies ‘currently employed’, while a value of 0 denotes ‘not currently employed’.

is the employment probability of participant ; is the age of participant ; is the square of the age of participant ; is the number of children of participant ; is the square of the number of children of participant ; is the household income of participant for year (the sum of the labor income of household members); is the population of the city/province where participant resides; is the attributes of participant (education level, residence in a metropolitan area, homeownership, health status, and marital status); is the error term.

Based on the estimated employment probability from Equation (15), the future employment status of participant is determined as follows:

Finally, using the values of the number of children and employment status, obtained from Equations (14) and (15), the future income is estimated. This study utilizes the Mincer earnings function, which effectively leverages the variables that capture the attributes of workers in the KLIPS data (Kawaguchi 2011). Specifically, Equation (16) is used to estimate the income of each participant after the survey period. For regular employees, income is determined by variables such as age and its square, tenure and its square, the number of children, individual attributes (education level, metropolitan area residence, health status, marital status, firm size, and occupation), and unobservable individual-specific residuals. For self-employed and irregular workers, the firm size and occupation variables are excluded from Equation (16).

is the natural logarithm of participant ’s annual income for year ; is the participant ’s years of tenure for year (continuous years of employment: CE); is the square of participant ’s years of tenure for year ; is the attributes of participant (education level, metropolitan area residence, health status, marital status, firm size, and occupation); is the unobservable individual effects (unobservable individual-specific residual); is the error term.

The calculation of lifetime income is represented by Equation (17), with 2020 as the base year. This includes the portion of labor income (wage or business income) self-reported by household members and the predicted values from Equation (16). For household members excluded from the sample in certain years, the predicted annual income is used similarly to the method for estimating future income. The first term in Equation (17) represents the annual income from the initial enrollment in the NPS to the current time (2020), adjusted to 2020 values. The second term represents the annual income from the current time to just before retirement, adjusted to 2020 values, considering the future employment probability derived from Equation (15). The present value of each participant’s annual income is determined by the real interest rate () and the real wage growth rate (). The decision to use real interest rates instead of nominal interest rates in this paper is driven by the aim of adopting the macroeconomic indicators (real economic growth rate, real wage growth rate, real interest rate, and inflation rate) used in the 5th National Pension Financial Estimate Results (Ministry of Health and Welfare 2023b) to ensure consistency across these indicators (a similar approach was employed by S. H. Kim (2019)). Additionally, to ensure consistency between sample and actual values, an adjustment coefficient , which is the 10-year average ratio (2011–2020) of the median income estimated from KLIPS data to the actual monthly average wages by gender and employment type reported in the “Survey on Employment Conditions by Employment Type: Wages and Working Hours by Employment Type” by the Ministry of Employment and Labor (2021), is applied to Equation (17).

is the reported annual income of participant for year ; is the predicted annual income of participant for year ; is the initial year of National Pension enrollment; is 2020 (the reference year); is the year of retirement; is the real interest rate (the discount rate) for year ; is the real wage growth rate for year ; is the employment status of participant (employed = 1, not employed = 0); is the adjustment coefficient; is the lifetime income of participant (evaluated as of 2020).

6. Results

6.1. Income Redistribution Effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal

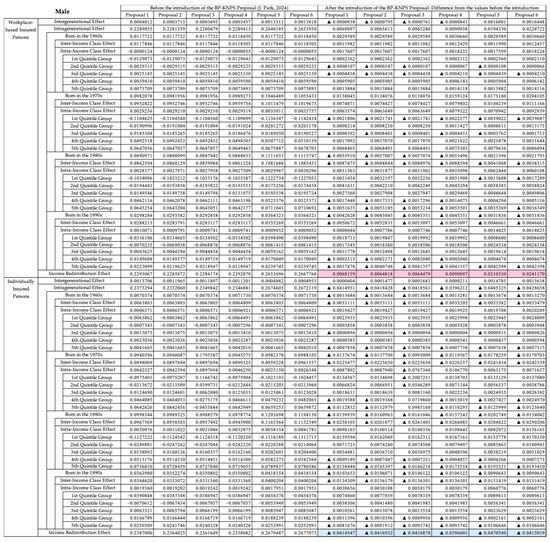

In this study, we measured the income redistribution effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal by comparing the MLD of income redistribution through the CNPS with the MLD through the BP-KNPS Proposal (6.1.1), comparing the MLD through the 5NPCPD with the MLD through the BP-KNPS Proposal (6.1.2), and comparing the MLD through the CNPS with the MLD through the BP-KNPS Proposal, implemented through the 5NPCPD (6.1.3). Table 7 provides an overview of the results measuring the income redistribution effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal across different types of NPS participation using the MLD indicator.

Table 7.

Income redistribution effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal from the perspective of MLD.

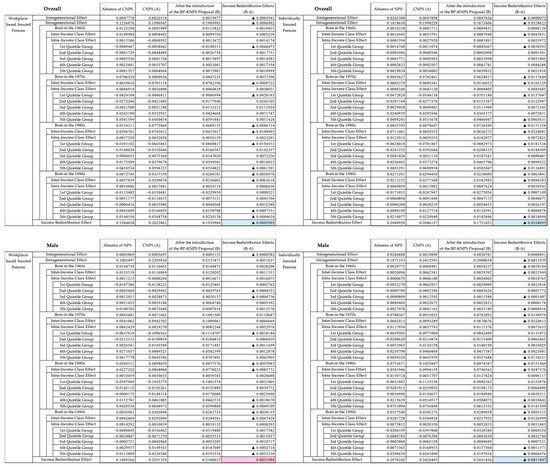

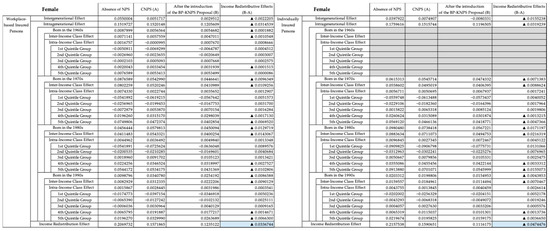

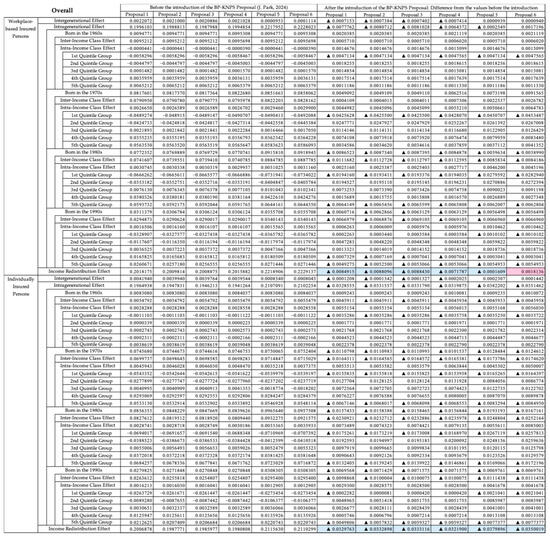

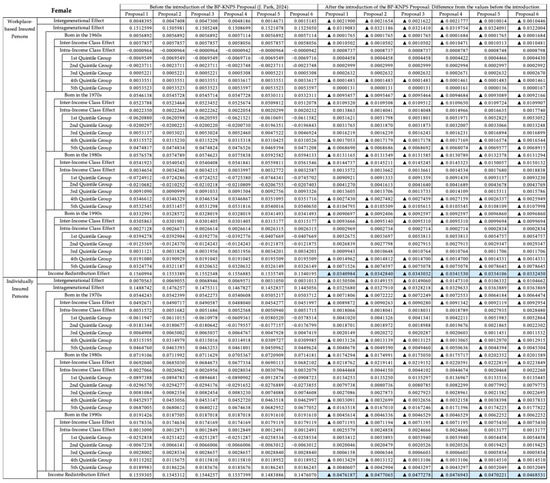

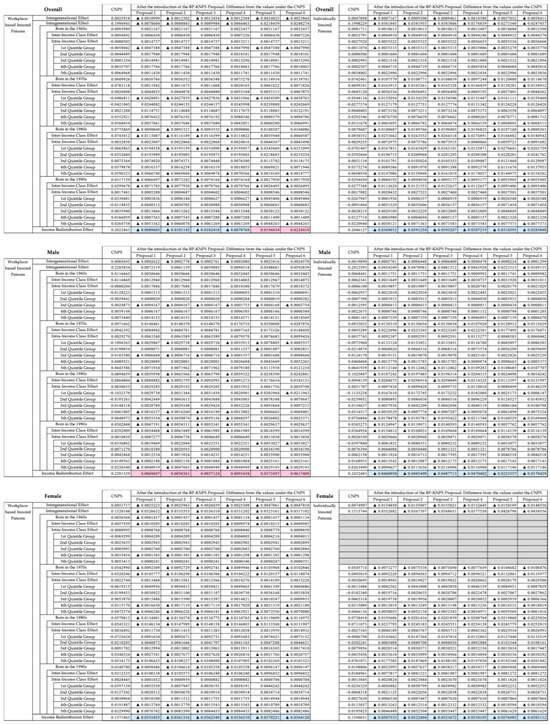

Figure A1, Figure A2 and Figure A3 illustrate the income redistribution effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal, decomposing these effects into intergenerational and intragenerational effects, with respective values presented for each. As described in Equation (15), the intragenerational effect (the income redistribution within a generation) is further decomposed into inter-tier and intra-tier effects. Additionally, Figure A2 and Figure A3 show the “After the Introduction of the BP-KNPS Proposal” section, indicating the extent to which income disparity has decreased (shown by a decrease in MLD) or increased (shown by an increase in MLD) compared to the CNPS, reflecting the effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal.

6.1.1. Effect of Introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal to the CNPS

Upon testing Hypothesis 1 defined in this study, it was confirmed that implementing the BP-KNPS Proposal in the CNPS resulted in a reduction in income disparity among pensioners’ old-age pension incomes. Figure A1 summarizes the income redistribution effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal, analyzed using the MLD, while reflecting the disparities in contribution periods and average life expectancy across different income tiers, as introduced in Table 4 and Table 5.

Firstly, as shown in Figure A1, introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal into the CNPS resulted in a reduction in income inequality, regardless of employment type. Specifically, the MLD for Workplace-based Insured Persons, including regular employees, decreased by 0.0092903 (with intragenerational income redistribution contributing 0.0086962). Similarly, the MLD for Individually Insured Persons, including self-employed and irregular workers, decreased by 0.0324695 (with intragenerational income redistribution contributing 0.0324623). These results indicate that the reduction in intragenerational income inequality significantly contributed to the overall decrease in income inequality, highlighting the greater impact of the BP-KNPS Proposal on self-employed and irregular workers compared to regular employees.

6.1.2. Effect of Introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal to the 5NPCPD

Upon testing Hypothesis 2 defined in this study, it was confirmed that implementing the BP-KNPS Proposal in the 5NPCPD also led to a reduction in the income disparity among pensioners’ old-age pension incomes. As shown in Figure A2, the income redistribution effects of introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal into all reform proposals of the 5NPCPD (from Proposal 1 to Proposal 6) varied by employment type. For Workplace-based Insured Persons (regular employees), the proposals involving an increase in contribution rates (Proposals 1, 2, and 3) and the proposal for adjusting the rate of increase in contribution rates (Proposal 4) led to a reduction in income inequality. In contrast, proposals to raise the pensionable age (Proposals 5 and 6) were found to increase income inequality. Specifically, the MLD of the net transfer amount (lifetime pension benefits minus lifetime pension contributions) after introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal under the contribution rate increase proposals (Proposals 1, 2, and 3) by 0.0071787. Conversely, the MLD under the proposals to raise the pensionable decreased by 0.0084915 to 0.0088430, indicating a reduction in income inequality. Similarly, the MLD under the proposal for adjusting the increase in contribution rates (Proposal 4) decreased age (Proposals 5 and 6) increased by 0.0018136 for Proposal 6 (and decreased by 0.0001609 for Proposal 5), indicating an increase in income inequality.

For Individually Insured Persons (self-employed and irregular workers), all reform proposals (from Proposal 1 to Proposal 6) showed reduced income inequality. Specifically, the MLD of the net transfer amount after introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal under the contribution rate increase proposals (Proposals 1, 2, and 3) decreased by 0.0329763 to 0.0333116, indicating a reduction in income inequality. The MLD under the proposal for adjusting the increase in contribution rates (Proposal 4) decreased by 0.0321900. Additionally, the MLD under the proposals to raise the pensionable age (Proposals 5 and 6) decreased by 0.0350019 to 0.0379896.

These findings confirm that the income redistribution effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal are more pronounced for self-employed and irregular workers compared to regular employees, both under the CNPS and the 5NPCPD.

6.1.3. Comparison between the CNPS and the 5NPCPD after Implementing the BP-KNPS Proposal

Upon testing Hypothesis 3 defined in this study, it was confirmed that, compared to the CNPS, the 5NPCPD with the implementation of the BP-KNPS Proposal led to a reduction in income disparity among pensioners’ old-age pension incomes. In Figure A1 and Figure A2, we analyze the income redistribution effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal. Figure A3 examines the changes in income redistribution effects between the CNPS and various proposals in the 5NPCPD when combined with the BP-KNPS Proposal. Compared to the CNPS, the income redistribution effects of each reform proposal (Proposals 1 to 6) after introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal varied by employment type, as shown in Figure A3.

For Workplace-based Insured Persons, which include regular employees, the proposals to increase contribution rates (Proposals 1, 2, and 3) and to adjust the rate of increase in contribution rates (Proposal 4) demonstrated a reduction in income inequality. In contrast, the proposals to raise the pensionable age (Proposals 5 and 6) resulted in increased income inequality. Specifically, the MLD of the net transfer amount (lifetime pension benefits minus lifetime pension contributions) decreased by 0.0089603 to 0.0102418 under the contribution rate increase proposals, indicating a reduction in income inequality. Similarly, the MLD under the proposal to adjust the rate of increase in contribution rates (Proposal 4) decreased by 0.0078768. However, under the proposals to raise the pensionable age (Proposals 5 and 6), the MLD increased by 0.0194434 to 0.0224410, indicating increased income inequality.

For Individually Insured Persons, which include self-employed and irregular workers, all reform proposals (Proposals 1 to 6) demonstrated a reduction in income inequality. Specifically, the MLD of the net transfer amount decreased by 0.0369012 to 0.0393267 under the contribution rate increase proposals and by 0.0387219 under the proposal to adjust the rate of increase in contribution rates. The proposals to raise the pensionable age (Proposals 5 and 6) also resulted in a decrease in the MLD from 0.0285848 to 0.0310393. These results confirm that the income redistribution effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal are greater for self-employed and irregular workers compared to regular employees.

Further analysis by gender (refer to Figure A3) shows that, for male regular employees, the proposals to raise the pensionable age (Proposals 5 and 6) and increase the contribution rates (Proposals 1, 2, and 3), as well as the proposal to adjust the rate of increase in contribution rates (Proposal 4), increased income inequality compared to the current system. This was primarily due to the increased intragenerational income disparity among middle-aged cohorts (those born in the 1960s and 1970s). However, the increase in MLD was relatively minor, ranging from 0.0057124 to 0.0091438. For male regional participants, all reform proposals showed a reduction in income inequality, consistent with the overall results for regional participants. Specifically, the MLD of the net transfer amount decreased by 0.0170429 to 0.0487713. For female regular employees and female Individually Insured Persons, all reform proposals showed a reduction in income inequality, with the proposals to raise the pensionable age (Proposals 5 and 6) having a more significant effect. The MLD for regular employees decreased by 0.0351855 to 0.0370221, and for Individually Insured Persons, it decreased by 0.0507533 to 0.0583112.

7. Discussion

This study examines the income redistribution effects of the BP-KNPS Proposal based on a simulation analysis using microdata from the KLIPS. It compares the income redistribution situation under the CNPS benefit calculation formula with the changes that would occur if the BP-KNPS Proposal were introduced, both for the CNPS and for each reform proposal of the 5NPCPD. Lifetime income was used to estimate the income redistribution index, and the MLD was utilized as the income redistribution measure.

One of the primary functions of social security administered by the state is income redistribution, and public pension systems serve as a form of social insurance that supports this objective. Analyzing income redistribution from the perspective of public systems is significant for ensuring social equity, preventing poverty, and promoting social stability. This is particularly critical in Korea, where the challenges of a rapidly aging population, a declining birth rate, a rising elderly dependency ratio, and a high level of elderly poverty further emphasize the importance of the public system’s role. The BP-KNPS Proposal is part of this initiative.

Upon comparing the results of this paper with those of J. Park (2024), who analyzed the income redistribution effects of the 5NPCPD without the BP-KNPS Proposal, several differences emerge:

- According to J. Park (2024), the effect of reducing income inequality through the proposals to increase contribution rates (Proposals 1, 2, and 3) before introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal was minimal (the reduction in MLD was 0.0004688 to 0.0013988 for Workplace-based Insured Persons and 0.0039249 to 0.0060151 for Individually Insured Persons). However, after introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal, the reduction in MLD increased from 0.0089603 to 0.0102418 for Workplace-based Insured Persons and 0.0369012 to 0.0393267 for Individually Insured Persons.

- The author of J. Park (2024) found that the effect of reducing income inequality through the proposal to adjust the rate of the increase in contribution rates (Proposal 4) before introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal was also minimal (the reduction in MLD was 0.0006981 for Workplace-based Insured Persons and 0.0065319 for Individually Insured Persons). After introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal, the reduction in MLD increased to 0.0078768 for Workplace-based Insured Persons and 0.0387219 for Individually Insured Persons.

- The author of J. Park (2024) found that the proposals to raise the pensionable age (Proposals 5 and 6) increased income inequality for all employment types (the increase in MLD was 0.0196043 to 0.0206274 for Workplace-based Insured Persons and 0.0064172 to 0.0069503 for Individually Insured Persons). However, after introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal, these proposals showed a reduction in income inequality for Individually Insured Persons (the reduction in MLD was 0.0285848 to 0.0310393).

- The author of J. Park (2024) identified that income inequality in the absence of the NPS and under the CNPS and the 5NPCPD was primarily due to intragenerational income disparities. In contrast, after introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal, the reduction in MLD indicated that intragenerational income redistribution reduced overall income inequality under the CNPS and the proposals to increase contribution rates (Proposals 1, 2, and 3) and adjust the rate of increases in contribution rates (Proposal 4).

- The author of J. Park (2024) found that all reform proposals (Proposals 1 to 6) increased intragenerational income inequality for middle-aged cohorts (born in the 1960s and 1970s). However, after introducing the BP-KNPS Proposal, self-employed and irregular workers born in the 1970s showed a reduction in intragenerational income inequality under all reform proposals.

These findings suggest that the BP-KNPS Proposal can enhance income redistribution effects under the CNPS and the 5NPCPD. The BP-KNPS Proposal’s effect on reducing intragenerational income inequality is particularly notable. While Parametric Pension Reform, such as adjusting contribution rates and the pensionable age, has limited redistribution effects, Structural Pension Reform, like the BP-KNPS Proposal, which introduces bend points into the earnings-related portion of pension benefits, significantly enhances redistribution effects. Additionally, the redistribution benefits of the BP-KNPS Proposal are more substantial for self-employed and irregular workers compared to regular employees.

From the perspective of the MLD indicator, the BP-KNPS Proposal reduces income inequality compared to the CNPS. For regular employees, the MLD decreased from 0.2022863 to 0.1929960, and for self-employed and irregular workers, it decreased from 0.2046127 to 0.1721433, indicating a significant reduction in income inequality. The effect was more pronounced for self-employed and irregular workers. Additionally, it is confirmed in Figure A1, Figure A2 and Figure A3 that Structural Pension Reform, such as the BP-KNPS Proposal, has superior income redistribution effects compared to Parametric Pension Reform measures like adjustments in contribution rates and the pensionable age proposed in the 5NPCPD.

However, regarding the income-inequality-widening effect of the proposals to raise the pensionable age (Proposals 5 and 6), as pointed out by J. Park (2024), this study finds that the BP-KNPS Proposal’s income redistribution effect could not mitigate such an impact for regular employees. This result highlights that the triple burden on low-income participants—reduced benefits due to disparities in contribution periods, life expectancy disparities, and raised pensionable age—has a more significant impact than the income redistribution effect of the BP-KNPS Proposal identified in this study.

The significance of this study lies in the clarification of two key points.

First, publicly available documents from the Korean government related to the National Pension, such as the “National Pension Financial Estimate” and the “National Pension Comprehensive Plan (Draft),” conduct policy evaluations (such as replacement rates, cost–benefit ratios, and income redistribution) without considering the heterogeneity across income groups (e.g., disparities in pension contribution periods or life expectancy). However, when assessing the current state and considering pension reforms, it is crucial to consider the heterogeneity of individual contributors. In fact, under the CNPS, when reflecting income-group-specific disparities in contribution periods and life expectancy for each participant, it was confirmed that income inequality increased for all employment types.

Second, in light of the “pension financial stability” goal proposed by the Yoon Suk-yeol administration and from the perspective of the NPS’s income redistribution function, the proposal to raise contribution rates (including the reform of the generational rate increase speeds) in the 5NPCPD is more favorable. When reflecting on the income-group-specific disparities in contribution periods and the life expectancy for each participant, it was confirmed that the proposal to raise the pension age, regardless of whether the BP-KNPS Proposal was implemented, widened income inequality for all types of employment.

For a more realistic analysis of the income redistribution effect, it is necessary to consider the layers of the population not covered in this analysis. However, due to the limitations in the scope of this study, such an analysis was not conducted and remains a subject for future research. Also, this paper focuses on the income redistribution function, a key feature of the NPS. However, it does not extend its analysis to other critical aspects such as pension fund stability (the long-term sustainability of the pension system) or retirement income security. Both of these issues are vital in discussions of pension reform and are earmarked for future research.

Funding

This research was funded by the Keio Economic Society.

Informed Consent Statement

This study uses an open database and does not involve this problem.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in FigShare at [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26391427.v1, accessed on 23 July 2024]. The code and processed data used in the analysis of this study are openly available in FigShare at [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26391442.v1, accessed on 23 July 2024].

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| NPS | National Pension Scheme |

| CNPS | Current National Pension Scheme |

| 5NPCPD | 5th National Pension Comprehensive Plan (Draft) |

| BP-KNPS | Proposal to incorporate the Bend Points mechanism into the Korean NPS |

| OASDI | Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance |

| KLIPS | Korean Labor & Income Panel Study |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| MLD | Mean Log Deviation |

| SMI | Standard monthly income |

| KRW | Korean Won (Korea’s Currency Unit) |

| AIME | Average Indexed Monthly Earnings |

| PIA | Primary Insurance Amount |

Appendix A

Table A1.

The assumed values of macroeconomic indicators used in this paper.

Table A1.

The assumed values of macroeconomic indicators used in this paper.

| Economic Variables | Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023–2030 | 2031–2040 | 2041–2050 | 2051–2060 | 2061–2070 | 2071–2080 | |

| Real economic growth rate | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Real wage growth rate | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Real interest rate | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Inflation rate | 2.2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Notes: Population and economic outlook use median values, which are fundamental assumptions. The unit is expressed in percentage (%). Data source: created by the author referencing “Table 5. Assumptions of Economic Variables in Combined Scenarios” in the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s “The 5th National Pension Financial Estimate Results” (Ministry of Health and Welfare 2023b, p. 7).

Table A2.

The actual and assumed standard monthly income (SMI).

Table A2.

The actual and assumed standard monthly income (SMI).

| Upper Limit | Lower Limit | Applicable Period |

|---|---|---|

| 2,000,000 | 70,000 | 1988.11.~1995.3. |

| 3,600,000 | 220,000 | 1995.4.~2007.3. |

| 3,600,000 | 220,000 | 2007.4.~2008.3. (Employee) |

| 2007.4.~2008.6. (Employer) | ||

| 3,600,000 | 220,000 | 2008.4.~2009.6. (Employee) |

| 2008.7.~2009.6. (Employer) | ||

| 3,600,000 | 220,000 | 2009.7.~2010.6. |

| 3,680,000 | 230,000 | 2010.7.~2011.6. |

| 3,750,000 | 230,000 | 2011.7.~2012.6. |

| 3,890,000 | 240,000 | 2012.7.~2013.6. |

| 3,980,000 | 250,000 | 2013.7.~2014.6. |

| 4,080,000 | 260,000 | 2014.7.~2015.6. |

| 4,210,000 | 270,000 | 2015.7.~2016.6. |

| 4,340,000 | 280,000 | 2016.7.~2017.6. |

| 4,490,000 | 290,000 | 2017.7.~2018.6. |

| 4,680,000 | 300,000 | 2018.7.~2019.6. |

| 4,860,000 | 310,000 | 2019.7.~2020.6. |

| 5,030,000 | 320,000 | 2020.7.~2021.6. |

| 5,240,000 | 330,000 | 2021.7.~2022.6. |

| 5,530,000 | 350,000 | 2022.7.~2023.6. |

| 5,900,000 | 370,000 | 2023.7.~2024.6. |

| Multiplying the inflation rate (assumed value) of the 5th National Pension Financial Estimate by the value of the previous year. | 2024.7.~2081.6. | |

Notes: The currency unit is KRW. Data source: created by the author referencing the homepage of the National Pension Service (2023).

Table A3.

Descriptive statistics for the estimation of the number of children.

Table A3.

Descriptive statistics for the estimation of the number of children.

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kid | 36,846 | 1.442219 | 0.863746 | 0 | 5 |

| age | 36,868 | 33.22263 | 4.178013 | 16 | 39 |

| education level (No formal education to middle school graduate = 1, High school graduate = 2, Junior college graduate = 3, University graduate = 4, Graduate school graduate = 5) | 36,856 | 2.741507 | 0.988337 | 1 | 5 |

| employment status | 36,868 | 0.449957 | 0.497496 | 0 | 1 |

| lnwage | 36,868 | 1.979052 | 2.459094 | 0 | 7.600903 |

| lnhwage (total labor income of household members excluding married women) | 36,868 | 6.7881 | 3.162861 | 0 | 28.00957 |

| homeownership | 36,868 | 0.498861 | 0.500006 | 0 | 1 |

| residence in a metropolitan area (Seoul Special City, Gyeonggi Province, Metropolitan Cities (Busan, Daegu, Daejeon, Incheon, Gwangju, Ulsan) = 1, Others = 0) | 36,868 | 0.715037 | 0.451403 | 0 | 1 |

| year | 36,868 | 2008.15 | 7.075877 | 1997 | 2020 |

| region | 36,868 | 6.970082 | 4.611014 | 1 | 19 |

Data source: created by the author referencing the KLIPS data.

Table A4.

The estimation of the number of children using OLS.

Table A4.

The estimation of the number of children using OLS.

| Variables | Kid |

|---|---|

| age | 0.0605 *** |

| (0.00105) | |

| education level | −0.0657 *** |

| (0.00466) | |

| employment status | 0.00566 |

| (0.0190) | |

| lnwage | −0.0744 *** |

| (0.00423) | |

| lnhwage | 0.0362 *** |

| (0.00190) | |

| homeownership | 0.133 *** |

| (0.00861) | |

| residence in a metropolitan area | −0.123 |

| (0.0799) | |

| year | YES |

| region | YES |

| Constant term | −0.886 *** |

| (0.0892) | |

| Observations | 36,834 |

| Sample size | 5826 |

| Log likelihood | −43,750.36 |

| Wald chi2(45) | 6797.60 |

| Standard errors in parentheses |

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. A high Wald chi2 value indicates that at least one of the regression coefficients is significantly different from zero, implying that the explanatory variables collectively have an impact on the dependent variable. The number inside the parentheses of the Wald chi2 statistic denotes the ‘degree of freedom.’ Data source: created by the author referencing the KLIPS data.

Table A5.

Descriptive statistics for employment probability estimation.

Table A5.

Descriptive statistics for employment probability estimation.

| <Male> | |||||

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| employment status | 59,193 | 0.394354 | 0.488716 | 0 | 1 |

| age | 59,193 | 36.63639 | 7.390114 | 25 | 57 |

| age 2 | 59,193 | 1396.838 | 565.5429 | 625 | 3249 |

| kid | 59,193 | 0.950873 | 0.967501 | 0 | 5 |

| kid 2 | 59,193 | 1.840201 | 2.447556 | 0 | 25 |

| employment experience | 59,193 | 0.891119 | 0.311493 | 0 | 1 |

| residence in a metropolitan area (Seoul Special City, Gyeonggi Province, Metropolitan Cities (Busan, Daegu, Daejeon, Incheon, Gwangju, Ulsan) = 1, Others = 0) | 59,193 | 0.732131 | 0.442853 | 0 | 1 |

| lnhwage (total labor income of household members excluding married women) | 59,193 | 6.309842 | 3.08751 | 0 | 22.40521 |

| homeownership | 59,193 | 0.55167 | 0.497327 | 0 | 1 |

| education level (No formal education to middle school graduate = 1, High school graduate = 2, Junior college graduate = 3, University graduate = 4, Graduate school graduate = 5) | 59,191 | 2.945414 | 1.034599 | 1 | 5 |

| unhealthy condition (Unhealthy = 1, Healthy = 0) | 51,963 | 0.038085 | 0.191403 | 0 | 1 |

| marital status | 59,193 | 0.689085 | 0.462872 | 0 | 1 |

| population by city/province | 59,193 | 229,829.1 | 166,068.3 | 3315 | 585,772 |

| year | 59,193 | 2010.477 | 6.534704 | 1997 | 2020 |

| region | 59,193 | 6.80915 | 4.593756 | 1 | 19 |

| <Female> | |||||

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| employment status | 55,806 | 0.246103 | 0.430743 | 0 | 1 |

| age | 55,806 | 36.47563 | 7.473477 | 25 | 57 |

| age 2 | 55,806 | 1386.323 | 572.4163 | 625 | 3249 |

| kid | 55,806 | 1.103 | 0.971376 | 0 | 5 |

| kid 2 | 55,806 | 2.160162 | 2.581674 | 0 | 25 |

| employment experience | 55,806 | 0.568201 | 0.495331 | 0 | 1 |

| residence in a metropolitan area (Seoul Special City, Gyeonggi Province, Metropolitan Cities (Busan, Daegu, Daejeon, Incheon, Gwangju, Ulsan) = 1, Others = 0) | 55,806 | 0.735082 | 0.441293 | 0 | 1 |

| lnhwage (total labor income of household members excluding married women) | 55,806 | 5.839738 | 3.559387 | 0 | 22.40521 |

| homeownership | 55,806 | 0.554295 | 0.497048 | 0 | 1 |

| education level (No formal education to middle school graduate = 1, High school graduate = 2, Junior college graduate = 3, University graduate = 4, Graduate school graduate = 5) | 55,785 | 2.690687 | 0.976857 | 1 | 5 |

| unhealthy condition (Unhealthy = 1, Healthy = 0) | 48,678 | 0.045236 | 0.207824 | 0 | 1 |

| marital status | 55,806 | 0.830896 | 0.374847 | 0 | 1 |

| population by city/province | 55,806 | 215160.6 | 158417.9 | 3145 | 541,289 |

| year | 55,806 | 2010.019 | 6.371594 | 1997 | 2020 |

| region | 55,806 | 6.726123 | 4.606665 | 1 | 19 |

Note: The number ‘2’ listed above the variables ‘age’ and ‘kid’ represents the squared values of each variable. Data source: created by the author referencing the KLIPS data. The population data by city and province from 1998 to 2021 are sourced from Statistics Korea’s “Future Population Projections (by City and Province): 2022–2052” (Statistics Korea 2024a).

Table A6.

The estimation of employment probability using the Logit Model.

Table A6.

The estimation of employment probability using the Logit Model.

| Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Employment Status | Employment Status | ||

| Coefficient | Marginal Effect | Coefficient | Marginal Effect | |

| age | 0.538 *** | 0.092 | 0.453 *** | 0.066 |

| (0.0167) | (0.0190) | |||

| age 2 | −0.00913 *** | −0.002 | −0.00737 *** | −0.001 |

| (0.000218) | (0.000247) | |||

| kid | 0.285 *** | 0.049 | 0.518 *** | 0.075 |

| (0.0406) | (0.0451) | |||

| kid 2 | −0.0806 *** | −0.014 | −0.128 *** | −0.019 |

| (0.0138) | (0.0150) | |||

| employment experience | 0.679 *** | 0.116 | 0.837 *** | 0.121 |

| (0.0474) | (0.0321) | |||

| residence in a metropolitan area | 0.1000 | 0.017 | 1.610 *** | 0.233 |

| (0.239) | (0.287) | |||

| lnhwage | 0.0191 *** | 0.003 | 0.0601 *** | 0.009 |

| (0.00428) | (0.00427) | |||

| homeownership | 0.163 *** | 0.028 | −0.0596 ** | −0.009 |

| (0.0222) | (0.0249) | |||

| education level | 0.227 *** | 0.039 | −0.0502 *** | −0.007 |

| (0.0107) | (0.0134) | |||

| unhealthy condition | −0.270 *** | −0.046 | −0.245 *** | −0.035 |

| (0.0657) | (0.0706) | |||

| marital status | 0.212 *** | 0.036 | −0.170 *** | −0.025 |

| (0.0380) | (0.0470) | |||

| population by city/province | 3.06 × 10−7 | 5.23 × 10−8 | −2.95 × 10−6 *** | −4.27 × 10−7 |