Does Social Investment Influence Poverty and Economic Growth in South Africa: A Cointegration Analysis?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Related Literature

2.1. Social Investment and Poverty

2.2. Social Investment and Economic Growth

2.3. Theoretical Framework

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Model Specification

3.2. Definition of Variables and Expected Signs

3.3. Data Analysis and Estimation Technique Procedure

3.3.1. Stationary Test

3.3.2. Augmented Dickey-Fuller Test

i = 1

i = 1

3.3.3. Johansen Cointegration Test

- ➣

- Test for the order of integration of the variables

- ➣

- The setting of appropriate lag length of the VAR in the model

- ➣

- Choosing the suitable model along with deterministic factors (constant and trends)

- ➣

- The establishment of the reduced rank is tested

- ➣

- Carrying out the weak exogeneity test

- ➣

- Linear restrictions in the co-integration vectors is tested for

3.4. Diagnostic Tests

3.4.1. Serial Correlation

3.4.2. Heteroskedasticity Tests: No Cross Times

4. Results and Discussion

- a.

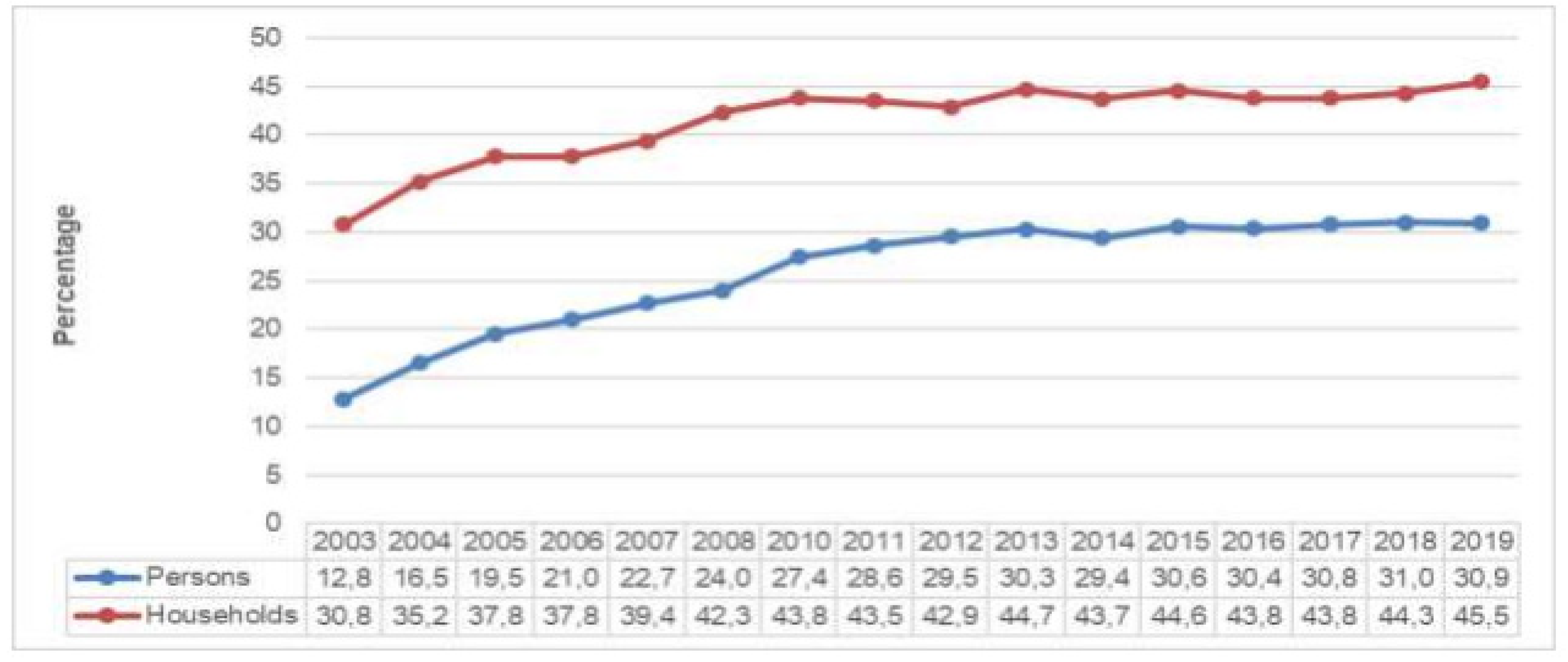

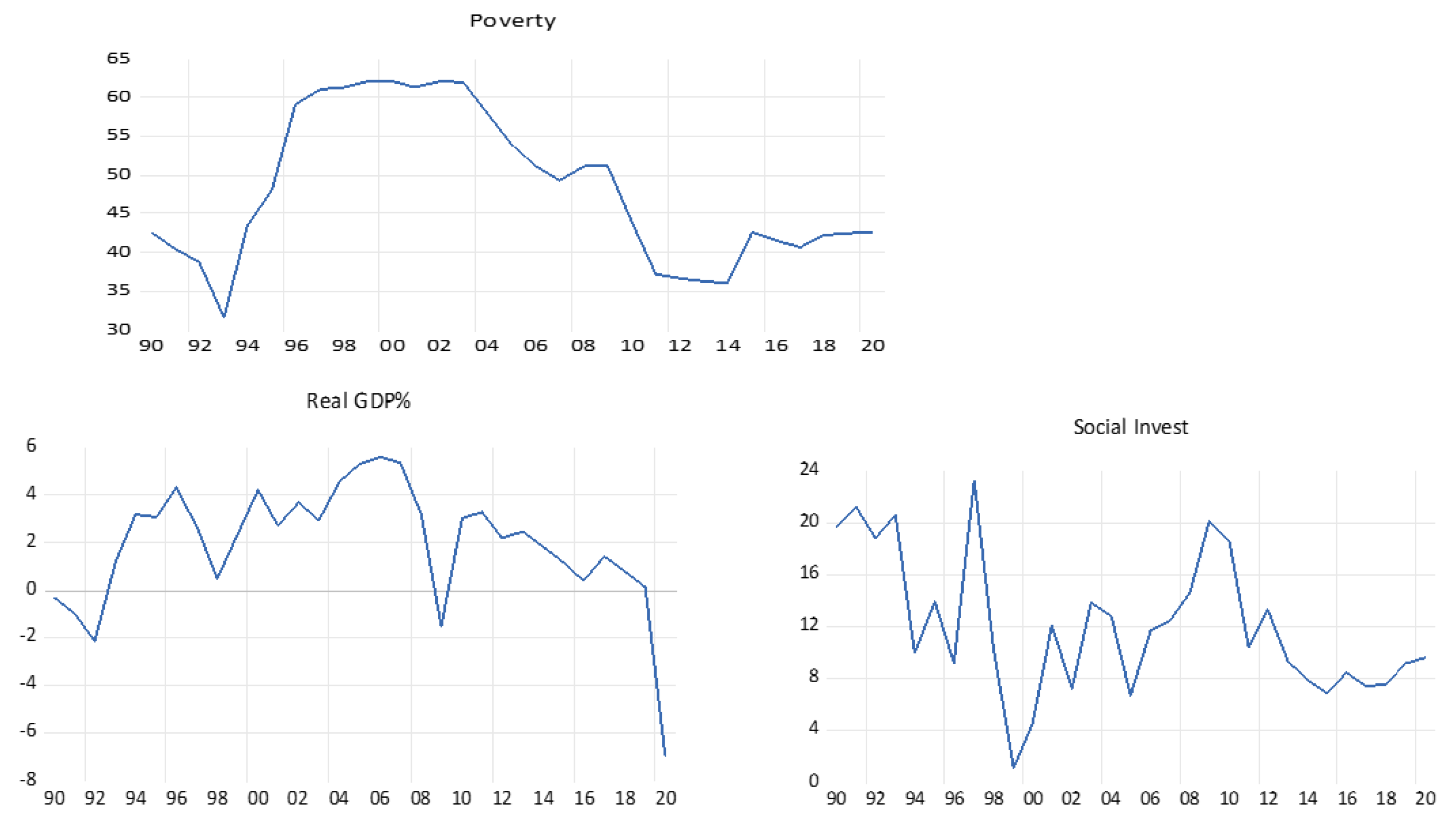

- Visual inspection of Variables at the level form

- b.

- Unit Root Test

- c.

- Johansen Cointegration Test

5. Concluding Remarks

- (1)

- In spite of having one of the worst rates of inequality and poverty in the world, South Africa is regarded as one of the top nations in terms of natural resource wealth and infrastructural development. The primary reason for these high rates is a significant lack of human capital or skills caused by inadequate health and education, particularly in rural areas where the bulk of black people live. Enhancing the infrastructure, education, and health facilities in rural areas can also help the economy thrive, which can subsequently help to lessen poverty and inequality.

- (2)

- It is critical that South African policymakers focus on human capital, natural economic growth, and long-term socio-economic development to reduce poverty and inequality. The creative and physical skills of its people fuel social investment that contributes to poverty alleviation, reduces inequality, and increases the economic growth of the population.

- (3)

- With a vast number of citizens staying in rural areas, implementing policies that encourage an increase in productivity at all levels would be beneficial to the country. This implies that South Africa’s macroeconomic policies, which appear to be more urban-focused, must be changed and channeled to policy initiatives as described in the national development programme (NDP), with tight restrictions in place to ensure its execution. The nature of rural and township life will change because of this strategy.

- (4)

- Social investments are insignificant, and they lack the power to produce an interaction effect that would raise the GDP’s capture index value. This means that after trying it for the past 20 to 30 years with various policies, the South African government must examine the reasons why the researched variables are not having a long-term association. As a result, the problem with government spending is with its direction rather than its amount.

- (5)

- The cointegration estimate results indicate that there is no cointegration between social investment, poverty, inequality, and economic growth. Thus, the critical focus should be on the beneficiaries of this expenditure, to determine the spread and its maximum optimum capacity to reduce poverty and inequality in the economy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adeleye, Ngozi, Obindah Gershon, Adeyemi Ogundipe, Oluwarotimi Owolabi, Ifeoluwa Ogunrinola, and Oluwasogo Adediran. 2020. Comparative Investigation of the Growth-Poverty-Inequality Trilemma in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin American and Caribbean Countries. Nigeria: Department of Economics and Development Studies. [Google Scholar]

- AFDB (African Development Bank). 2017. Indicators on Gender, Poverty, the Environment and Progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals in African Countries, Volume XVIII. Abidjan: African Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Sang-Hoon, and Soo-Wan Kim. 2015. Social investment, social service and the economic performance of welfare states. International Journal of Social Welfare 24: 109–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, Shahla, Zahid Pervaiz, Sajjad Ahmad Jan, and Kashif Saeed. 2021. Cross-District Analysis of Income Inequality and Education Inequality in Punjab (Pakistan). International Journal of Management 12: 561570. Available online: http://www.iaeme.com/IJM/issues.asp?JType=IJM&VType=12&IType=2 (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Amakom, Uzochukwu, and Kanayo Ogujiuba. 2010. Distribution Impact of Public Expenditure on Education and Healthcare in Nigeria: A Gender Based Welfare Dominance Analyses. International Journal of Business and Management 5: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Asteriou, Dimitrios, and Steven G. Hall. 2011. Applied Econometrics, 2nd ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, Robert J. 1999. Inequality, Growth, and Investment. (NBER Working Paper No. W7038). Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). [Google Scholar]

- Barro, Robert J. 2000. Inequality and growth in a panel of countries. Journal of Economic Growth 5: 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, Andrew, Jonathan Ostry, and Jeromin Zettelmeyer. 2012. What Makes Growth Sustained? Journal of Development Economics 98: 149–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, Özler. 2007. Not Separate, Not Equal: Poverty and Inequality in Post-apartheid South Africa. Economic Development and Cultural Change 55: 487–529. [Google Scholar]

- Bhorat, Haroon, and Carlene Van Der Westhuizen. 2012. Poverty, Inequality and the Nature of Economic Growth in South Africa. DPRU Working Paper 12/151. Cape Town: UCT. [Google Scholar]

- Bhorat, Haroon, Ravi Kanbur, and Natasha Mayet. 2012. The Impact of Sectoral Minimum Wage Laws on Employment, Wages and Hours of Work in South Africa. DPRU Working Paper 12/154, November. Cape Town: DPRU. [Google Scholar]

- Blanke, Jennifer, Caroline Ko, Marjo Koivisto, Jennifer Moyo, Peter Ondiege, John Speakman, and Audrey Verdier-Chouchane. 2013. Assessing Africa’s Competitiveness. pp. 1–38. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/The%20Africa%20Competitiveness%20Report%202013%20-%20Part%201%20-%20Assessing%20Africa’s%20Competitiveness.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Bloom, David, David Canning, and Kevin Chan. 2006. Higher Education and Economic Development in Africa. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Nicholas, Renata Lemos, Raffaella Sadun, Daniela Scur, and John van Reenen. 2014. The New Empirical Economics of Management. Journal of the European Economic Association 12: 835–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoli, Giuliano. 2012. Comment on Anton Hemerijck. Sociologica 1: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, Francois. 2003. The growth elasticity of poverty reduction: Explaining heterogeneity across countries and time periods. In Inequality and Growth: Theory and Policy Implications. Edited by Theo S. Eicher and Stephen J. Turnovsky. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, Ted. 2006. Theories of Poverty and Ant-Poverty Programs in Community Development. RPRC Working Paper No. 06-05. Columbia: Rural Poverty Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Busemeyer, Marius. 2007. The Determinants of Public Education Spending in 21 OECD Democracies, 1980–2001. Journal of European Public Policy 14582: 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, Simone, and Maria Rico. 2015. The rights-based approach in social protection. In Towards Universal Social Protection: Latin American Pathways and Policy Tools. ECLAC Books, No. 136. Edited by Simone Cecchini, Fernando Filgueira, Rodrigo Martínez and Cecilia Rossel. Santiago: ECLAC. [Google Scholar]

- Crossman, Ashley. 2021. The Sociology of Social Inequality. ThoughtCo. February 16. Available online: https://www.thoughtco.com/sociology-of-social-inequality-3026287 (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Dandan, Mwafaq. 2011. Government expenditure and economic growth in Jordan. International Conference on Economics and Finance Research Singapore 4: 467–471. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, Klaus, and John Okidi. 2003. Growth and Poverty Reduction in Uganda. Development Policy Review 21: 481–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, Stephen, Keetie Roelen, and Martina Ulrichs. 2015. Where Next for Social Protection? IDS Evidence Report 124. Brighton: IDS. [Google Scholar]

- Docampo, Domingo. 2007. International Comparisons in Higher Education. Working Paper. Gatersleben: ResearchGate. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunga, Steven Henry. 2014. The Channels of Poverty Reduction in Malawi: A District Level Analysis. Ph.D. thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Ebaidalla, Mahjoub. 2013. Causality between government expenditure and national income: Evidence from Sudan. Journal of Economic Cooperation and Development 34: 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Epaphra, Manamba, and John Massawe. 2016. Investment and Economic Growth: An Empirical Analysis for Tanzania. Turkish Economic Review 3: 4. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogdu, Erkan. 2007. Electricity demand analysis using cointegration ARIMA modeling: A case study of Turkey. Energy Policy 35: 1129–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Shenggen, Peter Hazell, and Sukhadeo Thorat. 1999. Government spending, growth and poverty in rural India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 82: 1038–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2021. What Are Social Safeguard Policies of International Financing Institutions? Rome: FAO. [Google Scholar]

- Fosu, Augustin. 2009. Inequality and the impact of growth on poverty: Comparative evidence for sub-Saharan Africa. The Journal of Development Studies 45: 726–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosu, Augustin. 2015. Growth, inequality and poverty in sub-Saharan Africa: Recent progress in a global context. Oxford Development Studies 43: 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosu, Augustin. 2018. The Recent Growth Resurgence in Africa and Poverty Reduction: The Context and Evidence. Journal of African Economies 27: 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadisi, Mikovhe, Enoch Owusu-Sekyere, and Abiodun Ogundeji. 2020. Impact of government support programmes on household welfare in the Limpopo province of South Africa. Development Southern Africa 37: 937–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, John, Shavit Madhala, and Guy Yanay. 2020. Social Investment in Israel. State of the Nation Report: Society, Economy and Policy in Israel 2020: 329–65. [Google Scholar]

- Garza-Rodriguez, Jorge. 2018. Poverty and economic growth in Mexico. Social Sciences 7: 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, William, and Edward Blakely. 2010. Separate Societies: Poverty and Inequality in US Cities, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gomanee, Karuna, Oliver Morrissey, Paul Mosley, and Adrian Verschoor. 2003. Aid, Pro-Poor Government Spending and Welfare. CREDIT Research Paper No. 3. Nottingham: Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade, University of Nottingham. [Google Scholar]

- Gyekye, Agyapong, and Oludele Akinboade. 2003. A profile of poverty in the Limpopo Province of South Africa. Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review 19: 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Geoff, and Claire Vermaak. 2015. Economic inequality as a source of interpersonal violence: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa and South Africa. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 18: a782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harris, Richard. 1995. Using Cointegration Analysis in Econometric Modelling. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Sin-Yu, and Bernard Iyke. 2018. Finance-growth-poverty nexus: A re-assessment of the trickle down hypothesis in China. Economic Change and Restructuring 51: 221–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogeveen, Johannes, and Berk Özler. 2006. Not Separate, Not Equal: Poverty and Inequality in Post Apartheid South Africa. Ann Arbor: William Davidson Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Howitt, Peter. 1999. Steady endogenous growth with population and RandD inputs growing. Journal of Political Economy 107: 715–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, Soren. 1991. Estimation and Hypothesis Testing of Cointegration Vectors in Gaussian Vector Autoregressive Models, Econometrica. The Econometric Society 59: 1551–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, Budlender. 2018. Key Features of Post-Apartheid Poverty. Available online: https://globaldialogue.isa-sociology.org/articles/key-features-of-post-apartheid-poverty (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Kamasa, Kofi, and Grace Ofori-Abebrese. 2015. Wagner’s or Keynes for Ghana? Government expenditure and economic growth dynamics, a VAR approach. Journal of Reviews on Global Economics 4: 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The General Theory of Interest, Employment and Money. London: McMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Khemili, Hasna, and Mounir Belloumi. 2018. Cointegration relationship between growth, inequality and poverty in Tunisia. International Journal of Applied Economics, Finance and Accounting 2: 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kularatne, Chandi. 2006. Social and Economic Infrastructure Impacts on Economic Growth in South Africa. Paper presented at the Development Policy Research Unit (DPRU) Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa, October 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Le, Manh, and Teruzazu Suruga. 2005. Foreign Direct Investment, Public Expenditure and Economic Growth: The Empirical Evidence for the Period 1970–2001. Applied Economic Letters 12: 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Leibbrandt, Murray, Amina Ebrahim, and Vimal Ranchhod. 2017. The Effects of the Employment Tax Incentive on South African Employment. Wider Working Paper 2017/5. Tokyo: United Nations University. [Google Scholar]

- Leibbrandt, Murray, and Ingrid Woolard. 2001. Labour Market and Household Income Inequality in South Africa. Paper Presented at the DPRU/FES Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa, November 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, Robert. 1988. On the Mechanics of Economic Development. Journal of Monetary Economics 22: 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhalima, Jabulile Lindiwe. 2020. An Analysis of The Determinants of Child Poverty in South Africa. International Journal Of Economics And Finance 12: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, Laurie, and Nieuwenhuis Rense. 2015. Family policies and single parent poverty in 18 OECD countries, 1978–2008. Community, Work & Family 18: 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, Asa. 2018. Translating social investment ideas in Israel: Economized social policy’s competing agendas. Global Social Policy 20: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monchuk, Victoria. 2014. Reducing Poverty and Investing in People: The New Role of Safety Nets in Africa; Directions in Development—Human Development. Washington: World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/16256 (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- More, Itumeleng, and Goodness Aye. 2017. Effect of social infrastructure investment on economic growth and inequality in South Africa: A SEM approach. International Journal of Economics and Business Research 13: 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, Nathalie, Bruno Palier, and Joakim Palme. 2012. Towards a Social Investment Welfare State: Ideas, Policies and Challenges. Bristol: The Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, Paul, John Hudson, and Arjan Verschoor. 2004. Aid, poverty reduction and the new conditionality. Economic Journal 114: 217–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimwe-Niyimbanira, Rachel, Zanele Ngwenya, and Ferdinand Niyimbanira. 2021. The Impact of Social Grants on Income Poverty in a South African Township. African Journal of Development Studies 11: 227–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, Alain. 2020. Is social investment inimical to the poor? Socio-Economic Review 18: 857–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunlela, Yemisi. 2012. Impact of the Programmes of the National Directorate of Employment on Graduate Employment in Kaduna State of Nigeria. Pakistan Journal of Sciences 9: 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Olamide, Ebenezer, Kanayo Ogujiuba, Andrew Maredza, and Semosa Phetole. 2022. Poverty, ICT and Economic Growth in SADC Region: A Panel Cointegration Evaluation. Sustainability 14: 9091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwatayo, Isaac, and Ayodeji Ojo. 2018. Walking through a tightrope: The challenge of economic growth and poverty in Africa. The Journal of Developing Areas 52: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotoso, Kehinde, and Stephen Koch. 2018. Assessing changes in social determinants of health inequalities in South Africa: A decomposition analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health 17: 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxaal, Zoe. 1997. Education and Poverty A gender Analysis. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, Hasheem, Yongcheol Shin, and Richard Smith. 1996. Testing for the Existence of a Long-Run Relationship. DAE Working Paper no. 9622. Cambridge: Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, Hasheem, Yongcheol Shin, and Richard Smith. 2001. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics 16: 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetsavong, Kongphet, and Masaru Ichihashi. 2012. The Impact of Public and Private Investment on Economic Growth: Evidence from Developing Asian Countries. Hiroshima: Hiroshima University. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, Paul. 1986. Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy 94: 1002–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, Paul. 1990. Endogenous Technological Change. Journal of Political Economy 98: S1971–S2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovny, Allison. 2014. The capacity of social policies to combat poverty among new social risk groups. Journal of European Social Policy 24: 405–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahn, David, and Stephen Younger. 2000. Expenditure Incidence in Africa: Microeconomic Evidence. Fiscal Studies 21: 329–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, Pravakar, Ranjan Dash, and Geethanjali Nataraj. 2012. China’s growth story: The role of physical and social infrastructure. Journal of Economic Development 37: 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, Takayuki. 2021. Do Social Investment Policies Reduce Income Inequality?: An Analysis of Industrial Countries. Journal of European Social Policy 31: 440–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Partap. 2012. Social Entrepreneurship: A Growing Trend in Indian Economy. International Journal of Innovations in Engineering and Technology (IJIET) 1: 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Adam. 1994. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. New York: Modern Library. [Google Scholar]

- Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit [SALDRU]. 2018. National Income Dynamics Study 2008, Wave 1 [Dataset]. Version 5.3. Cape Town: SALDRU [Producer]. Cape Town: DataFirst [Distributor]. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. 2017. Poverty Trends in South Africa. An Examination of Absolute Poverty beween 2006 and 2015. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. 2018. South Africa Poverty and Inequality Assessment Report. Pretoria: Government Printer. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. 2020. General Household Survey 2019/2020 [Dataset]. Version 1. Pretoria: Statistics SA [Producer]. Cape Town: DataFirst [distributor]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatsSA GHS (General Household Survey). 2020. Measuring the Progress of Development in the Country; Pretoria: StatsSA. Available online: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/GHS%202020%20Presentation%202-Dec-21.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- The National Development Plan (South African Government). 2015. Available online: https://www.gov.za/issues/national-development-plan-2030 (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Thevenon, Olivier, and Thomas Manfredi. 2018. Child poverty in the OECD. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper. Economics. Corpus ID: 158455491. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Todaro, Michael, and Stephen Smith. 2011. Economic Development. Boston: Addison-Wesley, England. [Google Scholar]

- Tomat, Gian Maria. 2007. Revisiting Poverty and Welfare Dominance. Washington: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Umbach, Gaby, and Igor Tkalec. 2021. Social investment policies in the EU: Actively concrete or passively abstract? Politics and Governance 9: 403–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2014. Economic Development in Africa Report 2014: Catalysing Investment for Transformative Growth in Africa. Geneva: UNCTAD, pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Berg. 2015. Funding University Studies: Who Benefits? (No. 10). Pretoria: Council for Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Berg, Krige Siebrits, and Bongisa Lekezwa. 2010. Efficiency and Equity Effects of Social Grants in South Africa (2010). Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers No. 15/10. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1727643 (accessed on 15 April 2019).

- Van Vliet, Olaf, and Chen Wang. 2015. Social Investment and Poverty Reduction: A Comparative Analysis across Fifteen European Countries. Journal of Social Policy 44: 611–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, Frank, and Koen Vleminckx. 2011. Disappointing poverty trends: Is the social investment state to blame? Journal of European Social Policy 2011: 450–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, William. 2006. Time Series Analysis Univariate and Multivariate Methods, 2nd ed. New York: Addison Wesley, pp. 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2001. World Development Report 2000/2001: Attacking Poverty. Washington: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2015. GINI Index (World Bank Estimate). Available online: http://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- World Bank. 2018. Overcoming Poverty and Inequality in South Africa. An Assessment of Drivers, Constraints, and Opportunities. Washington: World Bank. Available online: http://www.econrsa.org/system/files/publications/policy_papers/pp12.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Zizzamia, Rocco, Simone Schotte, and Murray Leibbrandt. 2019. Snakes and Ladders and Loaded Dice: Poverty Dynamics and Inequality in South Africa between 2008–2017. SALDRU Working Paper Number 235, Version 1/NIDS Discussion Paper 2019/2. Cape Town: SALDRU, UCT, p. 72. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Description of Variables | Expected Relationship with Social Investment |

|---|---|---|

| SOCIAL INVESTMENT | Expenditure on social investment is captured as aggregate expenditure on social investment to government expenditure [for instance, education, housing, health, and social services]. This is a proxy for social investment. | |

| POVERTY | Poverty is a measure of the basic standard of living for the citizens of a country. The annual per capita income, the percentage of the population living on less than one or two dollars per day, and the three poverty lines used in South Africa were all proposed as indicators for poverty measurement in the previous literature. | + (positive) |

| GDP | It is proxied for annual earnings, which are captured as domestic absorption in an economy. | + (positive) |

| Variables | Level Test Statistic | First Difference Test Statistic | Critical Values | Order of Integration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 5% | 10% | ||||

| SOCI | 0.8342 | 0.0016 | −4.309824 | −3.574244 | −3.221728 | Non-Stationary I(0) at level form and first difference Stationary I(1) at all critical values (1%,5%,10%) |

| POV | 0.8435 | 0.0008 | −4.309824 | −3.574244 | −3.221728 | Non-Stationery I(0) at level form but first difference Stationary I(1) at all critical values (1%,5%,10%) |

| GDP | 0.8540 | 0.0021 | −4.309824 | −3.574244 | −3.221728 | Non-Stationery I(0) at level form but first difference Stationery I(1) at all critical values (1%,5%,10%) |

| Trace Statistics | ||||

| Hypothesized No of CE(s) | Eigen Value | Trace Statistic | 5% Critical Value | Probability |

| None | 0.265684 | 8.712390 | 15.49471 | 0.3927 |

| At most 1 | 0.002338 | 0.065534 | 3.841465 | 0.7979 |

| *(**) denotes rejection of the claim at the 5% level. Trace test indicates no cointegration at both the 5% level. | ||||

| Max Eigen | ||||

| Hypothesized No of CE(s) | Eigen Value | Max Eigen Statistic | 5% Critical Value | Probability |

| None | 0.265684 | 8.646855 | 14.26460 | 0.3167 |

| At most 1 | 0.002338 | 0.065534 | 3.841465 | 0.7979 |

| *(**) denotes rejection of the claim at the 5% level. Max Eigen value test indicates no cointegration at both the 5% level. | ||||

| Heteroscedasticity | |||

| F-static | 1.486196 | Prob. F | 0.2330 |

| Obs * R-square | 1.512093 | Prob. Chi-square (1) | 0.2188 |

| Scaled explained SS | 0.290785 | Prob. Chi-square (1) | 0.5897 |

| Breusch-Godfrey Serial Correlation LM Test | |||

| F-Static | Durbin-Watson stat | Prob. | |

| 99.97582 | 1.894210 | 0.000000 | |

| Outlier Test for Poverty | |||

| Coefficient | R-square | Probability | |

| −0.901970 | 0.919766 | 0.0028 | |

| Trace Statistics | ||||

| Hypothesized No of CE(s) | Eigen Value | Trace Statistic | 5% Critical Value | Probability |

| None | 0.306706 | 10.25643 | 15.49471 | 0.2615 |

| At most 1 | 4.56 × 10−7 | 1.28 × 10−5 | 3.841465 | 0.9992 |

| *(**) denotes rejection of the claim at the 5% (1%) level. Trace test indicates no cointegration at both the 5% and 1% level. | ||||

| Max Eigen | ||||

| Hypothesized No of CE(s) | Eigen Value | Max Eigen Statistic | 5% Critical Value | Probability |

| None | 0.306706 | 10.25642 | 14.26460 | 0.1956 |

| At most 1 | 4.56 × 10−7 | 1.28 × 10−5 | 3.841465 | 0.9992 |

| *(**) denotes rejection of the claim at the 5% (1%) level. Max Eigenvalue test indicates no cointegration at both the 5% and 1% level. | ||||

| Heteroscedasticity | |||

| F-static | 0.036361 | Prob. F | 0.8501 |

| Obs * R-square | 0.038820 | Prob. Chi-square (1) | 0.8438 |

| Scaled explained SS | 0.097992 | Prob. Chi-square (1) | 0.7543 |

| Breusch-Godfrey serial correlation LM Test | |||

| F-Static | Durbin-Watson stat | Prob. | |

| 6.830415 | 1.543980 | 0.003977 | |

| Outlier Test for GDP | |||

| Coefficient | R-square | Probability | |

| −0.215745 | 0.641184 | 0.0013 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ogujiuba, K.; Mngometulu, N. Does Social Investment Influence Poverty and Economic Growth in South Africa: A Cointegration Analysis? Economies 2022, 10, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10090226

Ogujiuba K, Mngometulu N. Does Social Investment Influence Poverty and Economic Growth in South Africa: A Cointegration Analysis? Economies. 2022; 10(9):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10090226

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgujiuba, Kanayo, and Ntombifuthi Mngometulu. 2022. "Does Social Investment Influence Poverty and Economic Growth in South Africa: A Cointegration Analysis?" Economies 10, no. 9: 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10090226

APA StyleOgujiuba, K., & Mngometulu, N. (2022). Does Social Investment Influence Poverty and Economic Growth in South Africa: A Cointegration Analysis? Economies, 10(9), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10090226