Muslim Clothing Online Purchases in Indonesia during COVID-19 Crisis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

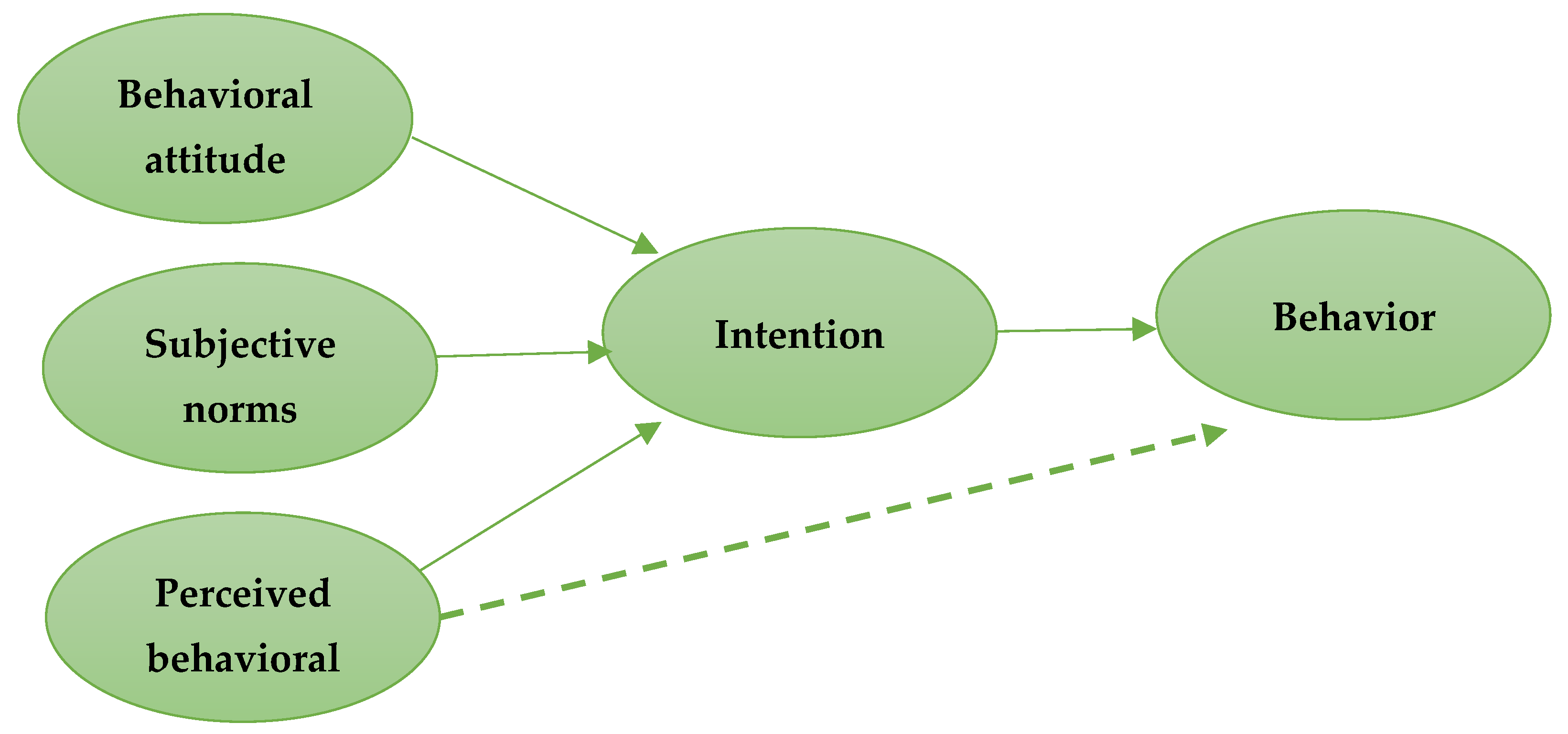

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2. Buying Intention

2.3. Attitude

2.4. Subjective Norm

2.5. Behavioral Control

2.6. Religious Belief

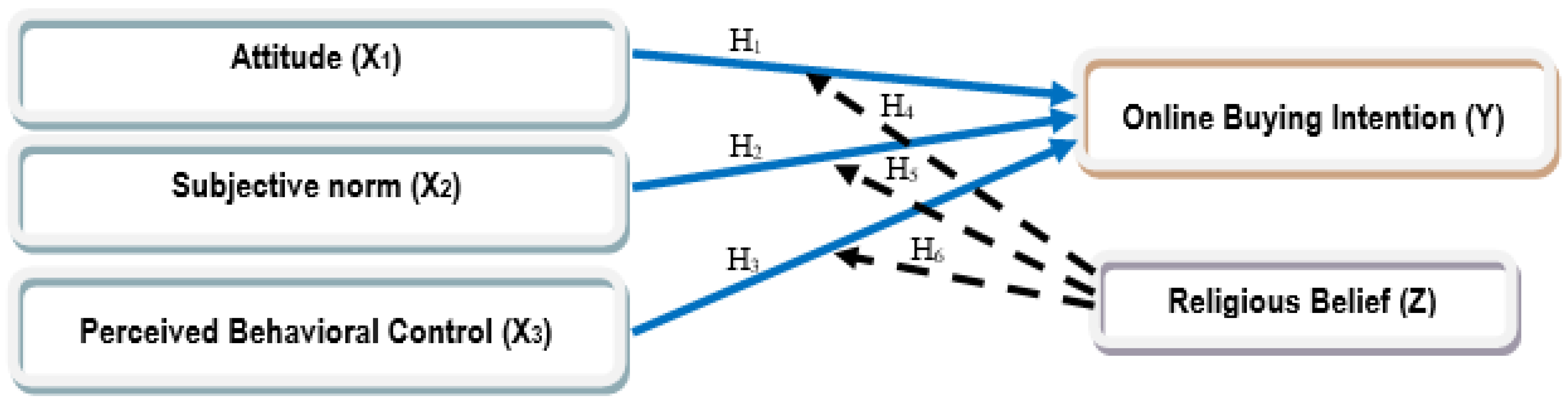

2.7. Conceptual Model

2.8. Thinking Framework and Hypotheses

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Types of Research

3.2. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

3.3. Data Analysis Method

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability Test

4.1.1. Validity Test

4.1.2. Reliability Test

4.1.3. Goodness of Fit (GOF)

4.2. Hypotheses Tests

5. Discussion

5.1. Attitude towards the Online Buying Intention of Muslim Clothing in Indonesia during the COVID-19 Crisis

5.2. Subjective Norm towards the Online Buying Intention of Muslim Clothing in Indonesia during COVID-19 Crisis

5.3. Perceived Behavioral Control the Online Buying Intention of Muslim Clothing in Indonesia during COVID-19 Crisis

5.4. Attitude Influences the Online Buying Intention of Muslim Clothing in Indonesia with Religious Belief as Moderating Variable

5.5. Subjective Norm Influences the Online Buying Intention of Muslim Clothing in Indonesia during the COVID-19 Crisis with Religious Belief as Moderating Variable

5.6. Perceived Behavioral Control Influences Online Buying Intention of Muslim Clothing in Indonesia during COVID-19 Crisis with Religious Belief as Moderating Variable

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ab Yajid, Mohd Shukri, and M. G. M. Johar. 2020. How Consumer’s Purchase Intention is affected by Attitude, Subjective Norms and Perceived Behavioral Control? Evidence from Telecommunication Sector. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy 11: 982–94. [Google Scholar]

- Agustian, Rinto. 2014. Peluang Usaha Distro Meraih Laba di Usia Muda. Yogyakarta: Pustaka Baru Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, Abu. 2002. Psikologi Sosial. Jakarta: Rineka Cipta. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, Icek, and Morris Fishbein. 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, Icek. 1985. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York and Tokyo: Springer, pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, Icek. 1991. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. In Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, pp. 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, Icek. 2005. Attitudes, Personality and Behavior, 2nd ed. New York: Open University Press-McGraw Hill Education, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Al Abdulrazak, Rula M., and Ayantunji Gbadamosi. 2017. Trust, religiosity, and relationship marketing: A conceptual overview of consumer brand loyalty. Society and Business Review 3: 320–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Abdullah, Usman Arshad, and Sayyed Adnan. 2012. Brand Credibility, Customer Loyalty and the Role of Religious Orientation Asia Pacific. Journal of Marketing and Logistics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, Joseph W., and J. Wesley Hutchinson. 1987. Dimensions of Consumer Expertise. Journal of Consumer Research 13: 411–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hyari, Khalil, Muhammed S. Alnsour, Ghazi Al-Weshah, and Mohamed Haffar. 2012. Religious beliefs and consumer behaviour: From loyalty to boycotts. Journal of Islamic Marketing. 2: 155–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabari, Mohammed A., Siti Norezam Othman, and Nik Kamariah Nik Mat. 2012. Actual Online Shopping Behavior among Jordanian Customers. American Journal of Economics 2: 125–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancok, Djamaludin, and Fuad Nashori Suroso. 2011. Psikologi Islami Solusi Islam Atas ProblemProblem Psikologi. Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar. [Google Scholar]

- Anoraga, Panji. 2010. Manajemen Bisnis (Edisi Kedua). Jakarta: Rineka Cipta. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, Zai Achmad. 2014. The Relationship between Religiosity and New Product Adoption among Muslim Consumers. International Journal of Management Sciences 6: 249–59. [Google Scholar]

- Antolin-Prito, Rebeca, Ana Reyes-Menendez, and Nuria Ruiz-Lacaci. 2021. Explorando los factores que afectan al comportamiento delos consumidores en plataformas de live streaming platforms. Espacios 42: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Asadifard, Mozhdeh, Azmawani Abduh Rahman, Yuhanis Abdul Aziz, and Haslinda Hashim. 2015. A Review on Tourist Mall Patronage Determinant in Malaysia. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology 6: 229–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, Saba, Muhammad Haroon Hafeez, Asif Yaseen, and Amna Naqvi. 2017. Do they care what they believe? Exploring the impact of religiosity on intention to purchase luxury products. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences (PJCSS) 11: 428–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ateeq-ur-Rehman, and Muhammad Shahbaz Shabbir. 2010. The relationship between religiosity and new product adoption. Journal of Islamic Marketing 1: 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrudin, Achmad, and Harapan Lulu Tobing. 2003. Analisis Data Untuk Penelitian Survey Dengan Menggunakan Lisrel 8. Bandung: FMIPA UNPAD. [Google Scholar]

- Bredahl, Lone. 2001. Determinants of Consumer Attitudes and Purchase Intentions with Regard to Genetically Modified Food—Results of a Cross-National Survey. Journal of Consumer Policy 24: 23–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chun-Der, Yi-Wen Fan, and Cheng-Kiang Farn. 2007. Predicting electronic toll collection service adoption: An integration of the technology acceptance model and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Transportation Research Part C Journal Emerging Technologies 5: 300–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, Mark, and Michel Laroche. 2007. Acculturaton to the global consumer culture: Scale development and research paradigm. Journal of Business Research 60: 249–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, Islahuddin, and Muhamad Eko Fitrianto. 2015. Peran Celebrity Endorser Dalam Membentuk. Manajemen Dan Bisnis Sriwijaya 13: 359–376. [Google Scholar]

- Dehyadegari, Saeid, Asghar Modhabaki Esfahani, Asadollah Kordnaiej, and Parviz Ahmadi. 2016. Study the relationship between Religiosity, Subjective norm, Islamic veil involvement and Purchase intention of veil clothing among Iranian muslim women. International Business Management 10: 2624–31. [Google Scholar]

- Delener, Nejdet. 1990. The Effects of Religious Factors on Perceived Risk in Durable Goods Purchase Decisions. Journal of Consumer Marketing 3: 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delener, Nejdet. 1994. Religious contrasts in consumer decision behavior patterns: Their dimensions and marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing 5: 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Menouar, Yasemin. 2014. The Five Dimensions of Muslim Religiosity. Results of an Empirical Study. Method, Data, Analyses 8: 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, James F., Roger Blackell, and Paul Miniard. 1995. Perilaku Konsumen. Edisi 6 Jilid 2. Jakarta: Binarupa Aksara. [Google Scholar]

- Essoo, Nittin, and Sally Dibb. 2004. Religious influences on shopping behaviour: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing Management 20: 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajar Subekhi, Rifki, and Ririn Tri Ratnasari. 2018. Religiousity and Theory of planned behaviour towards intention to give infaq. Jurnal Ekonomi Dan Bisnis Islam. Journal of Islamic Economics and Business 3: 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrag, Dalia Abdelrahman, and Mohammed Hassan. 2015. The Influence of Religiosity on Egyptian Muslim Youths’ Attitude Towards Fashion. Journal of Islamic Marketing 6: 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, Anna, Charlene Y. Senn, and David M. Ledgerwood. 2001. Predictors of Intention to Use Condoms Among University Women: An Application and Extension of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science 33: 103–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, Martin, and Icek Ajzen. 1975. Strategies of Change: Active Participation. In Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, Prerna, and Richa Joshi. 2018. Purchase intention of “Halal” brands in India: The mediating effect of attitude. Journal of Islamic Marketing 9: 683–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayatri, Gita, Mrgee Hume, and Gillian Sullivan Mort. 2011. The role of Islamic culture in service quality research. Asian Journal on Quality 1: 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghozali, Imam. 2008. Model Persamaan Struktural: Konsep dan Aplikasi Dengan Program AMOS 16.0. Semarang: Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro. [Google Scholar]

- Gopi, M., and T. Ramayah. 2007. Applicability of theory of planned behavior in predicting intention to trade online: Some evidence from a developing country. International Journal of Emerging Markets 2: 348–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph Franklin, Jeff Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Chistian M. Ringle. 2019. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 31: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafiah, Mohd Hafiz, and Nurul Alia Aqilah Hamdan. 2020. Determinants of Muslim travellers Halal food consumption attitude and behavioural intentions. Journal of Islamic Marketing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryono, Siswono. 2017. Metode SEM untuk Penelitian Manajemen AMOS Lisrel PLS. Jakarta: Luxima Metro Media. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, Haslinda, Siti Rahayu Hussin, and Nurdiyana Nadihahzainal Zainal. 2014. Exploring islamic retailer store attributes from consumers perspectives: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Economics and Management 8: 117–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Louise M., Edward M. K. Shiu, and Nina Michaelidou. 2010. The influence of nutrition information on choice: The roles of temptation, conflict and self-control. Journal of Consumer Affairs 44: 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, Elizabet. 1981. American Jewish Ethnicity: Its Relationship to Some Selected Aspects of Consumer Behavior. Journal of Marketing 45: 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, Daire, Joseph Coughlan, and Michael R. Mullen. 2008. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6: 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff Criteria for fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Byron R., Sung Joon Jang, David B. Larson, and Spencer De Li. 2001. Does Adolescent Religious Commitment Matter? A Reexamination of the Effects of Religiosity on Delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 38: 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumani, Zulfikar Ali, and Sasiwemon Sukhabot. 2021. Identifying the important attitude of Islamic brands and its effect on buying behavioural intentions among Malaysian Muslims: A quantitative study using smart-PLS. Journal of Islamic Marketing 12: 408–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Hyunmo, Minhi Hahn, David R. Fortin, Yong J. Hyun, and Yunni Eom. 2006. Effects of Perceived Behavioral Control on the Consumer Usage Intention of E-coupons. Psychology and Marketing 23: 841–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanuk, Leslie Lazar. 2008. Perilaku Konsumen, 7th ed. Jakarta: Indeks. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, Ali, Hossien Rezaei Dolat Abadi, and Nastaran Kabiry. 2013. Analyzing the Effect of Customer Equity on Repurchase Intentions. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 3: 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Khraim, Hamza. 2010. Article information: Measuring Religiosity in Consumer Research From an Islamic. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences 26: 52–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, Philip. 2012. Manajemen Pemasaran: Edisi 13, jilid 1 Pernerbit Airlangga, Jakarta, 13th ed. Jakarta: Erlangga. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- La Barbera, Priscilla A., and Zeynep Gürhan. 1997. The role of materialism, religiosity, and demographics in subjective well-being. Psychology and Marketing 14: 71–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, Barbara A., and Ronald E. Goldsmith. 1999. Corporate credibility’s role in consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions when a high versus a low credibility endorser is used in the Ad. Journal of Business Research 44: 109–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, Barbara A., Ronald E. Goldsmith, and G. Tomas M. Hult. 2004. The impact of the alliance on the partners: A look at cause-brand alliances. Psychology and Marketing 21: 509–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Ben, and Stephen Potter. 2007. The adoption of cleaner vehicles in the UK: Exploring the consumer attitude e action gap. Journal of Cleaner Production 5: 1085–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latan, Hengky, and Imam Ghozali. 2012. Partial Least Square: Konsep, Teknik, dan Aplikasi SmartPLS 2.0 M3. Semarang: Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro. [Google Scholar]

- Latan, Hengki, and Richard Noonan. 2017. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications. Stockholm: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Nancy R., and Philip Kotler. 2008. Social Marketing: Influencing Behaviors for Good. Choice Reviews Online (Vol. 45). Los Angeles: Sage Publication, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Kwek Choon, Dazmin Daud, Tan Hoi Piew, Kay Hooi Keoy, and Padzil Hassan. 2011. Perceived Risk, Perceived Technology, Online Trust for the Online Purchase Intention in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Management 6: 167–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mahardhika, Ayu Anastasya dan Saino. 2014. Analisis Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi Niat Beli Di Zalora Online Shop. Jurnal Ilmu Manajemen 2: 917–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ma’ruf, Jaman J., Osman Mohamad, and T. Ramayah. 2005. Intention to purchase via the internet: A comparison of two theoretical models. Asian Academy of Management Journal 10: 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, Bosnjak, Galesic Mirta, and Tuten Tracy. 2007. Personality determinants of online shopping: Explaining online purchase intentions using a hierarchical approach. Journal of Business Research 60: 597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhlis, Safiek. 2009. Relevancy and Measurement of Religiosity in Consumer Behavior Research. International Business Research 2: 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, Nazlida, and Dick Mizerski. 2010. The constructs mediating religions’ influence on buyers and consumers. Journal of Islamic Marketing 1: 124–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muda, M., and N. R. M. Khan. 2020. Electronic Word of Mouth (EWOM) and User Generated Content (UGC) on beauty Products on youtobe: Factors Affecting Consumer Attitudes and Purchase Intention. Malaysian Journal of Consumer and Family Economies 24: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar, Arshia, and Muhammad Mohsin Butt. 2012. Intention to choose Halal products: The role of religiosity. Journal of Islamic Marketing 3: 108–20. [Google Scholar]

- Munandar. 2014. Pengaruh Sikap Dan Norma Subyektif Terhadap Niat Menggunakan Produk Perbankan Syariah Pada Bank Aceh. Jurnal Visioner dan Strategis 3: 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ngah, Abdul Hafaz, Jagan Jeevan, Nurul. Haqimin Mohd Salleh, Taylor Tae Hwee Lee, and Siti. Marsila. Mhd Ruslan. 2020. Willingness to pay for halal transportation cost: The moderating effect of knowledge on the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Environmental Treatment Techniques 8: 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Heungsik, and John Blenkinsopp. 2009. Whistleblowing as planned behavior-A survey of south korean police officers. Journal of Business Ethics 85: 545–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peter, J. Petter, and C. Olson Jerry. 2008. Consumer Behavior Perilaku Konsumen dan Strategi Pemasaran. Jakarta: Erlangga. [Google Scholar]

- Pratana, Jessvita Anggelina Jaya. 2014. Analisis Pengaruh Sikap, Subjective Norm dan Perceived Behavioral Control Terhadap Purchase Intention Pelanggan SOGO Department Store di Tunjungan Plaza Surabaya. Jurnal Stratgei Pemasaran 2: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger, Yvette, and Omar Moufakkir. 2015. Cultural issues in tourism, hospitality and leisure in the Arab/Muslim world. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 9: 6–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Menendez, Ana, Jose Ramon Saura, and Pedro Palos-Sánchez. 2018a. Crowdfunding y financiacion 2.0. Un estudio exploratorio sobre el turis-mo cultural. International Journal of Information Systems and Tourism (IJIST) 3: 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Menendez, Ana, Jose Ramon Saura, Pedro R. Palos-Sanchez, and Jose Alvarez-Garcia. 2018b. Understanding User Behavioral Intention to Adopt a Search Engine that Promotes Sustainable Water Management. Symmetry 10: 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riadi, Edi. 2018. Statistik SEM: Structural Equation Modeling Dengan LISREL. Edited by Elizabeth Kurnia. Yogyakarta: Penerbit ANDI. [Google Scholar]

- Riptiono, Sulis. 2019. Does Islamic Religiosity Influence Female Muslim Fashion Trend Purchase Intention? An Extended of Theory of Planned Behavior. Iqtishadia 12: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salim, Muhartini, Lizar Alfansi, Sularsih Anggarawati, Fachri Eka Saputra, and Chairil Afandy. 2021. The Role of perceived usefulness in moderating the relationship between the DeLone and McLean model and user satisfaction. Uncertain Supply Chain Management 9: 755–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, G Leon, and Lesli Lazar Kanuk. 2008. Consumer Behavior, 7th ed. Englewood Cliff: Prentice Hall Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, Blair H., Jon Hartwick, and Paul R. Warshaw. 1988. The Theory of Reasoned Action: A Meta-Analysis of Past Research with Recommendations for Modifications and Future Research. Journal of Consumer Research 15: 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, Jae. K., Anique A. Quereshi, and Roberta M. Siegel. 2000. The International Handbook of Electronic Commerce. New York: Glenlake Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Siswomihardjo, Sari Winahjoe, Sudiyanti Sudiyanti, and Bayu Sutikno. 2019. Testing the Robustness of Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting Women’s Intention to Wear Jilbab. Jurnal Kawistara 8: 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Souiden, Nizar, and Marzouki Rani. 2015. Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions toward Islamic banks: The influence of religiosity. International Journal of Bank Marketing 33: 143–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevich, Alina. 2017. Explaining the Consumer Decision-Making Process. Critical Literature Review Journal of International Business Research and Marketing 2: 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Rodney, and Charles Y. Glock. 1968. American Piety: The Nature of Religious Commitment. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sumarwan, Ujang. 2011. Riset Pemasaran dan Konsumen: Panduan Riset dan Kajian: Kepuasan, Perilaku Pembelian, Gaya Hidup, Loyalitas dan Persepsi Resiko. Bogor: PT Penerbit IPB Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suryani, Tatik. 2008. Implikasi pada Strategi Pemasaran. Yogyakarta: Graha Ilmu. [Google Scholar]

- Suyanto, Mohammad. 2003. Strategi Periklanan Pada E-Commerce Perusahaan Top Dunia. Yohyakarta: Penerbit Andi. [Google Scholar]

- Swimberghe, Krist, Laura Flurry, and Janna M. Parker. 2011. Consumer Religiosity: Consequences for Consumer Activism in the United States. Journal of Business Ethics 103: 453–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassi, Sadra. 2012. The Role of Animosity, Religiosity and Ethnocentrism on Consumer Purchase Intention: A Study in Malaysia Toward European Brands. African Journal of Business Management 6: 6890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taib, Fauziah Md., T. Ramayah, and Dzuljastri Abdul Razak. 2008. Factors influencing intention to use diminishing partnership home financing. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 1: 235–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Margaret, and Thompson S. H. Teo. 1998. Factors Influencing the Adoption of the Internet. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 2: 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimourpour, Bahar, and Kambiz Heidarzadeh Hanzaee. 2011. The impact of culture on luxury consumption behaviour among Iranian consumers. Journal of Islamic Marketing 2: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triastity, Rahayu, dan Saputra Dwi, and Saputro. 2013. Pengaruh Sikap dan Norma Subyektif Terhadap Niat Beli Mahasiswa Sebagai Konsumen Potensial Produk Pasta Gigi Pepsodent. Surakarta: Universitas Slamet Riyadi Surakarta. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, Hardius, Prijono Tjiptoherijanto, T. Ezni Balqiah, and I. Gusti Ngurah Agung. 2017. The role of religious norms, trust, importance of attributes and information sources in the relationship between religiosity and selection of the Islamic bank. Journal of Islamic Marketing 8: 158–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayan, Ni, Sri Suprapti, Ni Nyoman, and Kerti Yasa. 2015. Aplikasi theory of planned behavior dalam membangkitkan niat berwirausaha bagi mahasiswa fakultas ekonomi unpaz, DILI Leonel da Cruz 1 Program Magister Manajemen Universitas Udayana (Unud). Denpasar, Bali Indonesia Fakultas Ekonomi dan Bisnis, Univer 12: 895–920. [Google Scholar]

- Yasid, Fikri Farhan, and Yuli Andriansyah. 2016. Factors affecting Muslim students awareness of halal products in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. International Review of Management and Marketing 6: 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, Raja Nerina R. 2013. Halal Foods in the Global Retail Industry, 1st ed. Serdang: Universiti Putra Malaysia Press, Available online: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/10.1108/SBR-03-2017-0014 (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Zafar, Qurat-Ul-Ain, and Mahira Rafique. 2012. Impact of Celebrity Advertisement on Customers’ Brand Perception and Purchase Intention. Asian Journal of Business and Management Sciences 1: 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrad, H., and M. Debabi. 2015. Analyzing the Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth on Tourists’ Attitude Toward Destination and Travel Intention. Available online: http://www.isca.in/IJSS/Archive/v4/i4/7.ISCA-IRJSS-2015-019.php (accessed on 17 February 2021).

| Demographic Attributes | Choice | Number of Answers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Man | 190 | 24.9% |

| Woman | 572 | 75.1% | |

| Total Respondents | 762 | 100% | |

| Your Age | 12—15 years | 12 | 1.6% |

| 16—18 years | 84 | 11% | |

| 19—21 years | 145 | 19% | |

| >21 years old | 521 | 68.4% | |

| Total Respondents | 762 | 100% | |

| Marital status | Not married yet | 407 | 53.4% |

| Marry | 355 | 46.6% | |

| Total Respondents | 762 | 100% | |

| Your Occupation | Student/Student | 320 | 42% |

| Government employees | 115 | 15% | |

| Private employees | 118 | 15% | |

| TNI/POLRI | 25 | 3.3% | |

| Businessman | 28 | 3.7% | |

| Other | 156 | 20% | |

| Total Respondents | 762 | 100% | |

| Your monthly income | <IDR 2,000,000 | 420 | 55.1% |

| Between IDR 2,000,000 to IDR 5,000,000 | 203 | 26.6% | |

| Between IDR 5,000,000 to IDR 10,000,000 | 97 | 12.7% | |

| Between IDR 10,000,000 to IDR 50,000,000 | 16 | 2.1% | |

| >Between IDR 50,000,000 | 26 | 3.5% | |

| Total Respondents | 762 | 100% | |

| Your Domicile | Sumatra | 359 | 47.1% |

| Java-Bali | 135 | 17.7% | |

| Borneo | 72 | 9.5% | |

| Sulawesi | 53 | 7% | |

| NTB-NTT | 48 | 6.3% | |

| Maluku | 46 | 6.1% | |

| Papua | 49 | 6.4% | |

| Total Respondents | 762 | 100% | |

| Variable Latent | Variable Manifest | Critical | Estimate | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loading | Factor Loading | |||

| ATT | ATT1 | 0.5–0.7 | 0.67 | Valid |

| ATT2 | 0.77 | Valid | ||

| ATT3 | 0.71 | Valid | ||

| ATT4 | 0.69 | Valid | ||

| ATT5 | 0.69 | Valid | ||

| ATT6 | 0.66 | Valid | ||

| ATT7 | 0.71 | Valid | ||

| ATT8 | 0.69 | Valid | ||

| ATT9 | 0.61 | Valid | ||

| NS | NS1 | 0.5–0.7 | 0.70 | Valid |

| NS2 | 0.80 | Valid | ||

| NS3 | 0.83 | Valid | ||

| NS4 | 0.73 | Valid | ||

| NS5 | 0.65 | Valid | ||

| PD | PD3 | 0.5–0.7 | 0.62 | Valid |

| PD4 | 0.68 | Valid | ||

| PD5 | 0.79 | Valid | ||

| PD6 | 0.84 | Valid | ||

| PD7 | 0.81 | Valid | ||

| BI | BI1 | 0.5–0.7 | 0.67 | Valid |

| BI2 | 0.73 | Valid | ||

| BI3 | 0.72 | Valid | ||

| BI4 | 0.72 | Valid | ||

| BI5 | 0.71 | Valid | ||

| BI6 | 0.76 | Valid | ||

| BI7 | 0.78 | Valid | ||

| BI8 | 0.77 | Valid | ||

| BI9 | 0.53 | Valid | ||

| BI13 | 0.61 | Valid | ||

| BI14 | 0.68 | Valid | ||

| BI15 | 0.71 | Valid | ||

| BI16 | 0.73 | Valid | ||

| RLG | RLG1 | 0.5–0.7 | 0.50 | Valid |

| RLG2 | 0.54 | Valid | ||

| RLG3 | 0.51 | Valid | ||

| RLG5 | 0.53 | Valid | ||

| RLG6 | 0.56 | Valid | ||

| RLG8 | 0.58 | Valid | ||

| RLG9 | 0.58 | Valid | ||

| RLG10 | 0.59 | Valid | ||

| RLG11 | 0.58 | Valid | ||

| RLG12 | 0.60 | Valid | ||

| RLG13 | 0.60 | Valid | ||

| RLG14 | 0.56 | Valid | ||

| RLG15 | 0.57 | Valid |

| Variable Latent | Variable Manifest | Estimate | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loading | |||||

| ATT | ATT1 | 0.67 | 0.7 | 0.94 | Reliable |

| ATT2 | 0.77 | ||||

| ATT3 | 0.71 | ||||

| ATT4 | 0.69 | ||||

| ATT5 | 0.69 | ||||

| ATT6 | 0.66 | ||||

| ATT7 | 0.71 | ||||

| ATT8 | 0.69 | ||||

| ATT9 | 0.61 | ||||

| NS | NS1 | 0.70 | 0.7 | 0.94 | Reliable |

| NS2 | 0.80 | ||||

| NS3 | 0.83 | ||||

| NS4 | 0.73 | ||||

| NS5 | 0.65 | ||||

| PD | PD3 | 0.62 | 0.7 | 0.94 | Reliable |

| PD4 | 0.68 | ||||

| PD5 | 0.79 | ||||

| PD6 | 0.84 | ||||

| PD7 | 0.81 | ||||

| BI | BI1 | 0.67 | 0.7 | 0.98 | Reliable |

| BI2 | 0.73 | ||||

| BI3 | 0.72 | ||||

| BI4 | 0.72 | ||||

| BI5 | 0.71 | ||||

| BI6 | 0.76 | ||||

| BI7 | 0.78 | ||||

| BI8 | 0.77 | ||||

| BI9 | 0.53 | ||||

| BI13 | 0.61 | ||||

| BI14 | 0.68 | ||||

| BI15 | 0.71 | ||||

| BI16 | 0.73 | ||||

| RLG | RLG1 | 0.50 | 0.7 | 0.97 | Reliable |

| RLG2 | 0.54 | ||||

| RLG3 | 0.51 | ||||

| RLG5 | 0.53 | ||||

| RLG6 | 0.56 | ||||

| RLG8 | 0.58 | ||||

| RLG9 | 0.58 | ||||

| RLG10 | 0.59 | ||||

| RLG11 | 0.58 | ||||

| RLG12 | 0.60 | ||||

| RLG13 | 0.60 | ||||

| RLG14 | 0.56 | ||||

| RLG15 | 0.57 |

| No | Measurement of Goodness of Fit | Cut-off Value | Estimation Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| absolute fit indices | ||||

| 1 | Chi-square P | Small scores p ≥ 0.05 | 6031.22 0.00 | Poor Fit |

| 2 | RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.069 | Good Fit |

| 3 | ECVI | (7.413—8.307) | 8.26 | Good Fit |

| 4 | RMR | ≤0.05 | 0.05 | Good Fit |

| incremental fit indices | ||||

| 5 | NFI | ≥0.90 | 0.97 | Good Fit |

| 6 | CFI | ≥0.95 | 0.98 | Good Fit |

| 7 | IFI | >0.90 | 0.98 | Good Fit |

| 8 | RFI | >0.90 | 0.97 | Good Fit |

| 9 | NNFI | ≥0.90 | 0.98 | Good Fit |

| parsimony fit indices | ||||

| 10 | PNFI | ≥0.90 | 0.92 | Good Fit |

| Hypotheses | Exogent Variables | Endogen Variables | tstatistic | ttabel | Criterion | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ATT | BI | 5.78 | 1.96 | Significant | Complied |

| 2 | NS | BI | 3.44 | 1.96 | Significant | Complied |

| 3 | PD | BI | 4.25 | 1.96 | Significant | Complied |

| 4 | ATT*RLG | BI | 2.51 | 1.96 | Significant | Strengthening |

| 5 | NS*RLG | BI | −1.85 | 1.96 | Not Significant | Weakening |

| 6 | PD*RLG | BI | −0.44 | 1.96 | Not Significant | Weakening |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salim, M.; Aprianto, R.; Anwar Abu Bakar, S.; Rusdi, M. Muslim Clothing Online Purchases in Indonesia during COVID-19 Crisis. Economies 2022, 10, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10010019

Salim M, Aprianto R, Anwar Abu Bakar S, Rusdi M. Muslim Clothing Online Purchases in Indonesia during COVID-19 Crisis. Economies. 2022; 10(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalim, Muhartini, Ronal Aprianto, Syaiful Anwar Abu Bakar, and Muhammad Rusdi. 2022. "Muslim Clothing Online Purchases in Indonesia during COVID-19 Crisis" Economies 10, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10010019

APA StyleSalim, M., Aprianto, R., Anwar Abu Bakar, S., & Rusdi, M. (2022). Muslim Clothing Online Purchases in Indonesia during COVID-19 Crisis. Economies, 10(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10010019