2.1. A Short Introduction to TTR (A Theory of Types with Records)

As mentioned, TTR attempts to be a foundational theory of language and cognition, and as such aims to cover many (all) aspects of linguistics. TTR also makes semantics more cognitively oriented in comparison to model theoretic semantics and sees language as action, similarly to DS. This means that it is reasonable to try various ways of marrying the two.

We give a brief sketch of the aspects of TTR which we will use in this paper. For more detailed accounts, see

Cooper (

2023) (or

Cooper and Ginzburg (

2015) for a short overview).

s:T represents a judgment that s is of type T. Types may either be basic or complex (in the sense that they are structured objects which have types or other objects introduced in the theory as components). One basic type that we will use is Ind, the type of individuals; another is Real, the type of real numbers.

Given that and are types, is the type of total functions with domain objects of type and range included in the collection of objects of type .

Among the complex types are ptypes, which are constructed from a predicate and arguments of appropriate types as specified for the predicate. Examples are ‘man(a)’, ‘see(a,b)’, where . The objects or witnesses of ptypes can be thought of as situations, states or events in the world which instantiate the type. Thus, can be glossed as “s is a situation which shows (or proves) that a is a man”.

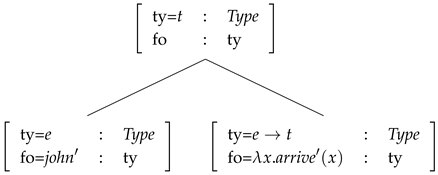

In TTR, records are modeled as a labeled set consisting of a finite set of fields. Each field is an ordered pair, , where ℓ is a label (drawn from a countably infinite stock of labels) and o is an object which is a witness of some type. No two fields of a record can have the same label. Importantly, o can itself be a record.

A record type is like a record except that the fields are of the form , where ℓ is a label as before and T is a type. The basic intuition is that a record, r, is a witness for a record type, T, just in the case that for each field, , in T, there is a field, , in r, where (note that this allows for the record to have additional fields with labels not included in the fields of the record type). The types within fields in record types may depend on objects which can be found in the record that is being tested as a witness for the record type. We use a graphical display to represent both records and record types, where each line represents a field. Example (1) represents a type of record which can be used to model situations where a man runs.

(1)

A record of this type would be of the form

(2)

where , , and .

Types may contain manifest fields like the field below:

(3)

Here,

is a convenient notation for

, where

is a

singleton type. If

, then

is a singleton type and

if

.

4 Manifest fields allow us to progressively specify what values are required for the fields in a type.

A type is a subtype of a type , , just in case implies no matter what we assign to the basic types and ptypes. Record types introduce a restrictive notion of subtyping.

(4) ⊑

(4) holds independently of what boys and dogs there are and what kind of hugging is going on. We can tell that the record type to the left is a subtype of the one to the right simply by the fact that the set of fields of the latter is a subset of the set of fields of the former.

It is possible to combine record types. An object a is of the meet type of and , , if and . If and are record types, then there will always be a record type (not a meet) , which is necessarily equivalent to . is the merging of and , written as :

| (5) | |

If and are record types, the asymmetric merge is a record type similar to the meet type , except that if a label ℓ occurs in both and , the value of ℓ in will be . Intuitively, it is the union of the two records, but for any shared labels, the value of the label in is chosen over the value of the label in .

| (6) | |

In addition to providing various kinds of types as we have so far discussed, TTR introduces type actions and action rules. Judgments are a kind of type action, and we use the formula in (7) to indicate, and agent, A, judges the object, o, to be of type T.

(7)

There can also be non-specific judgments where an agent judges that there is something of a type, that is, the type is non-empty. When we are thinking of types as propositions, the type being non-empty corresponds to the proposition being true. In standard type theories, this is often written as ‘’. Thus, if ‘run(d)’ is a type of situation where the individual d runs, then the type (proposition) is true, just the in the case that there is a situation of this type. (8) represents that agent, A, judging that there is something of type T.

(8)

A third kind of type action is to create an object of a given type. This is particularly useful when we wish to represent an agent performing some action, that is, creating a situation of a given type. In the notation, we use ‘!’ to indicate a creation. Thus, (9) represents that agent, A, creating an object of type T.

(9)

Note that there is no specific version of this type action—you cannot create something that already exists.

For more kinds of type acts and further discussion, see

Cooper (

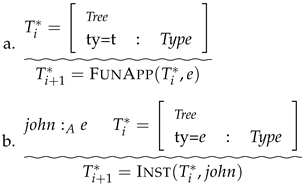

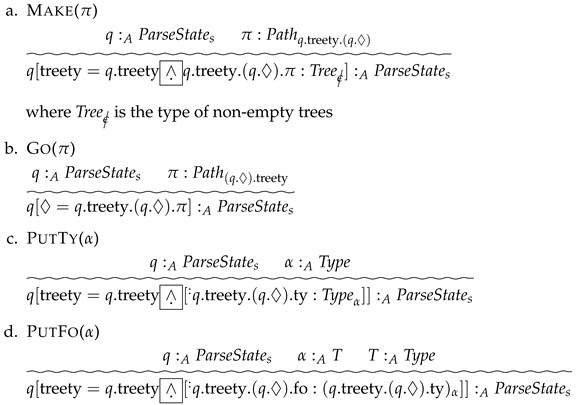

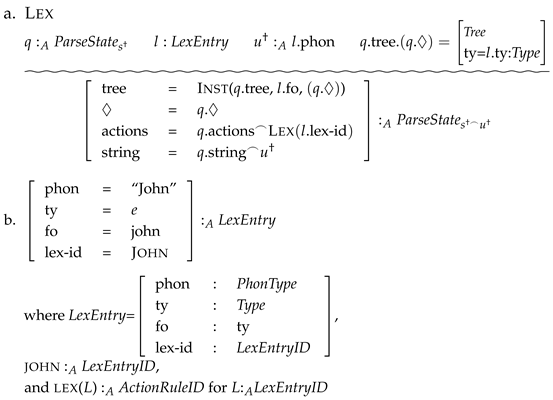

2023, Section 2.3). Type actions are regulated by action rules of the form (10).

| (10) | ![Languages 10 00300 i001 Languages 10 00300 i001]() |

Each

is either an action or some other condition that must hold true and

must be an action. While (10) is in the form of a proof tree indicating that the

are premises and

is a conclusion, we use the wavy line as opposed to a straight line in order to indicate that this is not a rule of inference but a rule which indicates that the premises above the line hold

license or

afford on the action below the line. Thus, there is no guarantee that the agent will carry out the action even if all the premises hold. In this way, TTR’s action rules can be seen as providing a calculus of

affordance in something like the sense of

Gibson (

1979). We will use TTR action rules in this paper to model the parse actions introduced by DS.