1. Introduction

Dialect contact occurs when speakers of different, yet mutually intelligible, language varieties interact regularly. Much like variationist research, studies in this field often rely on one-on-one sociolinguistic interviews to investigate the outcomes of such contact. Typically, these studies adopt a community-wide perspective, aiming to document the emergence of new dialects. Evidence of dialect formation is found in the ways speakers adjust their linguistic practices to align more closely with those of their interlocutors. The extent and direction of this accommodation are influenced by both linguistic and social factors, leading speakers either to converge with others or to preserve features from their dialects of origin.

1However, an important issue arises when sociolinguistic analyses rely exclusively on one-on-one interview data. In such settings, speakers are often recorded interacting with interviewers they have only just met—individuals who may also belong to a different dialect group, and thus be perceived as outgroup members. This context raises the question of whether speakers might adopt different dialect styles in alternative settings where the effects of the observer’s paradox (

Labov, 1972) are less pronounced. For instance, would they shift toward a more ingroup-oriented style if they were observed interacting exclusively with members of their own dialect group? And to what extent would such shifts be intentional? These scenarios invite us to consider whether, in dialect contact situations, speakers purposefully engage in style-shifting to align themselves with particular social groups—a process observed in contexts where dialect contact is less prominent (see, e.g.,

Bell, 2001;

Eckert, 1989). Building on the work of Bell, Eckert, and others, we can therefore ask: to what degree do individuals in dialect contact situations actively position themselves as members of distinct groups through their linguistic choices across different contexts, and how aware and agentive are they in making these stylistic moves?

In this paper, I adopt a mixed-methods approach to examine style-shifting practices among five adult Spanish speakers in an Anglo-American context of dialect contact. The analysis draws on recordings of group activities and conversations conducted in both ingroup and outgroup settings, providing insights into language use beyond the traditional sociolinguistic interview. In addition, peer-based metalinguistic commentary elicitation sessions are used to explore participants’ awareness and evaluation of linguistic features, providing further context for understanding their language practices. The analysis focuses on two variable features that consistently emerged in participants’ commentary: the use of

voseo and

tuteo forms for the second-person singular (2SG) and the alternation between lenition and retention in coda /s/ production. Both features serve as indexes of dialectal affiliation and social positioning within the broader Spanish-speaking world (

Díaz-Campos et al., 2020).

My analysis shows that these speakers exhibit a heightened awareness of, and control over, variation in 2SG reference and coda /s/ production across the recorded settings. They strategically use these features both to position themselves and their interlocutors within distinct membership categories and to achieve specific pragmatic goals. Accordingly, the methodological and analytical approach employed in this study provides a nuanced, context-sensitive, and speaker-centered perspective on the language choices individuals make in dialect contact situations. This analysis further contributes to a deeper understanding of the motivations driving these choices.

2. Dialect Contact

Increased global mobility has led many individuals to relocate to regions or countries different from their place of birth or upbringing. Consequently, people from diverse regional or national dialect groups frequently come into contact. The study of these dialect contact situations and their outcomes is largely informed by the theoretical framework of linguistic accommodation. Originally developed by Howard Giles in the early 1970s (

Giles, 1973;

Giles et al., 1973), accommodation theory was later applied to English dialect contact by scholars such as

Trudgill (

1986),

Kerswill and Williams (

1992), and

Britain (

1997). Since then, the theory has evolved and expanded to address dialect contact settings involving various languages beyond English, including Arabic (e.g.,

Al-Wer, 2003), Brazilian Portuguese (e.g.,

Oushiro, 2020), and Chinese (e.g.,

Stanford, 2008), among others.

Accommodation theory broadly identifies two possible outcomes when dialects come into contact: accommodation or its absence. Accommodation usually involves the convergence of the dialects, making them more similar over time. According to

Dodsworth (

2017), this process can occur through leveling, which reduces the number of linguistic variants or the magnitude of variation among them, as well as through the emergence of intermediate or interdialectal forms that were not present in any of the dialects prior to contact. Consequently, accommodation leads to changes in language use that may eventually give rise to a new dialect—a variety that is unique to the speakers in contact (

Britain & Trudgill, 1999).

In contrast, lack of accommodation occurs when speakers retain features from their original dialects following contact. Although this may seem at odds with processes of language change or the formation of a new dialect, such retention is not necessarily static. Instead, these features are often repurposed, taking on new grammatical functions or sociolinguistic meanings—a process known as reallocation (

Dodsworth, 2017).

Several factors can influence the outcomes of dialect contact, either independently or in combination. These include the frequency and perceptual salience of a variant, the number and composition of individuals in contact, the social prestige associated with different groups, the age at which individuals arrive in a new environment, the length of their stay, and the structure of their social networks. With respect to frequency and salience,

Dodsworth (

2017) notes that while frequent variants tend to persist, socially marked variants often decrease in usage—even when they are common—given their perceptual prominence. In terms of group composition and prestige,

Boas (

2008) observes that although minority groups often accommodate to the linguistic patterns of the majority, the social prestige attached to a group can ultimately influence whether a variant is retained or lost. Age of arrival and length of residence also play a role: according to

Siegel (

2010), the earlier individuals are exposed to speakers of other varieties and the longer they remain in contact, the more likely they are to accommodate—an effect more pronounced among second-generation migrants than first-generation ones. Finally, social networks are also crucial.

Kerswill et al. (

2008) argue that individuals who regularly interact with speakers from a range of dialect backgrounds are more likely to adjust their speech patterns than those whose networks consist mainly of speakers from similar backgrounds.

In summary, these studies collectively show that individuals in dialect contact situations tend to either accommodate to others’ interactional styles—integrating changes into their speech—or retain features of their source varieties. Yet, because much of this research relies on one-on-one sociolinguistic interviews—often with newly encountered individuals who may not share the same dialect background—it remains underexplored how speakers in these contexts might intentionally develop and deploy distinct dialect styles for specific situations and interlocutors. This possibility warrants further investigation through methodological approaches designed to capture how such dialect styles are actively shaped and deployed. But before detailing the methods used in this study to document style-shifting practices and their motivations, I first review in

Section 3 selected research on Spanish dialect contact in Anglo-America. This review highlights commonly analyzed linguistic features, their social significance, and evidence that speakers’ choices extend beyond accommodation or non-accommodation. It also provides the foundation for

Section 4, where I outline the theoretical orientation guiding my analysis.

3. Spanish Dialect Contact in Anglo-America

The increased mobility of people that has marked the latter half of the 20th century and continues today is also evident in the Spanish-speaking world. Numerous studies have examined contemporary situations of Spanish dialect contact, arising from both national and international mobility. In the Iberian Peninsula, for instance,

Moya Corral (

2000) analyzed the speech of rural Andalusian migrants in Granada, while

von Essen (

2016) focused on the speech of Argentine migrants in Málaga. In Latin America,

Klee and Caravedo (

2006) investigated interactions between Andean migrants and Limeños in Lima, and

Fernández-Mallat (

2018b) examined the speech of Western Bolivian migrants in Chile.

However, the region experiencing the most pronounced growth in studies examining the consequences of Spanish dialect contact driven by migration is Anglo-America. As

Bonnici and Bayley (

2010) note, the region hosts a remarkable convergence of Spanish varieties, brought together by a continuous flow of migrants across the Spanish-speaking world. This diversity is especially visible in the U.S. Southwest and Northeast, as well as in Ontario, Canada. While Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Salvadoran communities once dominated these areas, they now share the Spanish-speaking landscape with speakers from an ever-widening array of countries. In this way, many parts of Anglo-America have evolved into truly multidialectal spaces.

In these regions, several dialect features are frequently discussed, including the expression or omission of subject personal pronouns, the choice between

voseo and

tuteo for the 2SG, and the variation in coda /s/ between lenition and retention. These features exhibit intralinguistic differences that help define regional distinctions among Spanish-speaking communities (

Erker, 2018). They are also shaped by local social norms and attitudes, making them highly salient markers of speech. An exception to this pattern is the expression of subject personal pronoun, which is primarily governed by linguistic factors across Spanish dialects and “fl[ies] entirely below the limits of sociolinguistic detection” (

Erker, 2018, p. 277).

In communities where

voseo and

tuteo coexist,

voseo carries both strong regional associations and significant social signaling potential. Regionally,

voseo is often linked to expressions of national pride and local identity (see, e.g.,

Bland & Morgan, 2020;

Jang, 2013). This is particularly noteworthy given that the regions in Latin America where

voseo is prevalent are not geographically contiguous and do not necessarily fall within the same national boundaries. The social signaling potential of

voseo derives primarily from its perception as vulgar and colloquial, lacking the overt prestige typically granted to

tuteo, even though

voseo is widely used across social groups and communicative contexts (

Carricaburo, 2015). To a lesser extent,

voseo may also serve as a marker of youth identity (

Rivadeneira Valenzuela, 2016) and as a resource for projecting masculinity (

Fernández-Mallat & Basterretxea Santiso, 2025).

Similarly, in communities where /s/ reduction is prevalent, its occurrence is shaped by the interaction of linguistic and social factors, including speakers’ regional origins and social backgrounds (

Erker, 2018). At the intergroup level, /s/ reduction is generally associated with the Caribbean and with coastal and lowland regions of Mainland Latin America, whereas /s/ retention is more closely linked to highland varieties. Within groups, however, /s/ lenition is typically regarded as a non-standard feature, despite its widespread use across social strata.

Walker et al. (

2014) provide further evidence that individuals from communities both with and without common /s/ reduction tend to evaluate /s/ lenition less favorably than /s/ retention. Yet their findings also indicate that, regardless of regional origin, listeners are more accepting of /s/ weakening in the speech of coastal speakers, suggesting that /s/ lenition is expected in these communities.

Research on Spanish dialect contact in Anglo-America consistently aligns with broader findings on dialect contact, indicating that both accommodation and non-accommodation can occur, depending on the factors discussed earlier. For instance,

Hernández (

2002) investigated how Salvadoran Spanish speakers in Houston—who typically use

voseo for the 2SG—adjust their speech when interacting with Mexican Spanish speakers, for whom

tuteo is more common. Hernández found that Salvadorans tend to accommodate their speech to Mexican norms for two main reasons: the Mexican community constitutes the majority of Spanish speakers in Houston, and the use of

voseo often triggers negative social reactions from both Mexicans and Salvadorans. Moreover, the study shows that individuals who have lived in Houston longer or arrived at a younger age are more likely to fully adopt Mexican Spanish, with childhood migrants often abandoning

voseo entirely.

Sorenson (

2016) extended this line of research by comparing how Salvadoran and Argentine Spanish speakers—both

voseo users—accommodate to

tuteo when interacting with different majority groups in various U.S. localities. Sorenson found that, unlike Salvadorans, Argentines largely retain

voseo despite contact with

tuteo-speaking communities. This persistence is explained by Argentines’ relatively high social status within U.S. Spanish-speaking communities and the symbolic value of

voseo as an expression of national identity.

Similar patterns emerge in studies of other linguistic variables.

Hoffman (

2001) examined coda /s/ variation among Salvadoran speakers in Toronto, who often reduce coda /s/. Consistent with

Hernández’s (

2002) findings, Hoffman observed that longer-term residents or those who arrived at younger ages were more likely to fully articulate coda /s/. In contrast,

Ghosh Johnson (

2005) studied dialect contact between Mexican and Puerto Rican Spanish speakers in Chicago, where the two groups differ in their realization of coda /s/. Surprisingly, her findings revealed minimal accommodation in either group, which she attributes to limited interaction and the predominance of English in their social exchanges.

Two additional observations are particularly relevant to Spanish dialect contact in Anglo-America. First, pre-contact linguistic constraints appear to persist even amid tendencies toward accommodation (

Erker & Otheguy, 2020). For example,

Aaron and Hernández (

2007) examined coda /s/ in Houston, focusing on how Salvadoran Spanish speakers accommodate to Mexican Spanish speakers. Their findings indicate that accommodation is influenced by the speakers’ age of arrival in Houston, with those arriving between 0 and 7 years of age showing the most significant accommodation. Nevertheless, certain linguistic constraints that were relevant prior to contact—such as those associated with surrounding phonological segments—remain influential after contact, regardless of arrival age.

Second, distinguishing dialect contact from language contact becomes challenging when English is involved (

Bonnici & Bayley, 2010). For instance,

Otheguy and Zentella (

2012) find that Mainland Spanish speakers in New York increase subject pronoun expression (SPE) when interacting with Caribbean Spanish speakers, with social networks, arrival age, and length of stay shaping usage. However, exposure to English emerges as the strongest predictor, suggesting that higher SPE rates reflect both Spanish dialect contact and English influence. As

Erker (

2018) notes, similar dynamics likely affect coda /s/ and 2SG reference: just as SPE patterns may be shaped by English, increased sibilant realizations and

tuteo usage may reflect the relative invariance of these features in English.

The literature suggests that, as in other dialect contact scenarios, Spanish speakers are often perceived as either accommodating their language to others or not, regardless of the specific factors influencing contact outcomes. This perception may stem from the dominant methodology, which typically relies on one-on-one sociolinguistic interviews capturing interactions between recently acquainted individuals who may or may not share a dialect. Yet, as

Bonnici and Bayley (

2010) and

Dodsworth (

2017) note, speakers in dialect contact situations may not fit neatly into these static categories. Instead, they may strategically adjust their speech—or even develop distinct dialect styles—depending on context and interlocutors, highlighting a complexity that warrants further investigation.

Metalinguistic commentary supports the idea that speakers in dialect contact situations often develop context-dependent adaptive abilities, adjusting their speech to achieve specific social goals. A clear illustration of this dynamic appears in

Negrón’s (

2011) ethnographic work in New York City, which documents Roberto, a Venezuelan who moved to the U.S. at age nine. Roberto describes modifying his speech depending on the audience to avoid conflict, foster connections with other U.S.-based Latinos, and secure financial stability. Similarly,

Woods and Rivera-Mills (

2012) show that Salvadorans and Hondurans in the Pacific Northwest, where Mexican Spanish predominates, report favoring

tuteo in outgroup contexts to foster pan-Latino solidarity, while reserving

voseo for ingroup settings as a marker of Central American identity.

These observations align with empirical research demonstrating that speakers expand their repertoires and adjust their communication styles in contact situations.

Hernández (

2009), for example, studied Salvadoran Spanish speakers in Houston interacting with Mexican Spanish speakers, focusing on word-final nasal pronunciation—a feature largely invariant in Mexican Spanish. Interviews conducted in both ingroup (Salvadoran) and outgroup (Mexican) contexts revealed that participants retained velarized realizations of word-final /n/ in ingroup interactions, reflecting pre-contact Salvadoran Spanish, but predominantly used non-velarized variants in outgroup interactions. A comparable pattern emerges in Montreal, where Chilean speakers maintain

voseo with ingroup members yet suppress it with

tuteo-speaking outgroup interlocutors (

Fernández-Mallat, 2011). More recently,

Potowski and Torres (

2023) document similar behavior in Chicago, showing that Puerto Rican speakers avoid velarized /r/ when speaking with Mexican interlocutors but maintain this feature, at least to some degree, with other Puerto Ricans. Notably, and echoing

Ghosh Johnson’s (

2005) findings discussed earlier,

Potowski and Torres (

2023) also report that Puerto Ricans show minimal accommodation in their realization of coda /s/ across interlocutor groups. This suggests that coda /s/ carries comparatively weak social meaning in this context, whereas velarized /r/ functions as a more socially salient feature.

In sum, these studies point to the limitations of traditional accommodation models, which frame dialect contact mainly in terms of accommodation or non-accommodation. They instead highlight the value of examining how speakers in dialect contact situations actively expand their linguistic repertoires and deploy adaptive communicative strategies suited to a range of social contexts and communicative goals.

4. Analytical Framework

One useful framework for examining how speakers adapt their linguistic practices to context is

Bell’s (

2001) audience design theory. This approach holds that speakers knowingly draw on different linguistic resources or styles depending on the specific time-configurations they navigate. Crucially, it highlights that linguistic choices are shaped not only by a speaker’s own identity stance—that is, the aspects of self they wish to articulate in a given moment—but also by the composition of the audience. Speakers remain attuned to who is present—whether addressees, overhearers, or eavesdroppers—and to the characteristics of those individuals, adjusting their speech accordingly to converge with, diverge from, or otherwise position themselves in relation to them. Because the speech of the five speakers in this study is examined across contexts involving different audiences, audience design offers a valuable lens for highlighting the inherently interactive and context-sensitive nature of style-shifting practices.

To further explore how individuals in a dialect contact situation purposefully use different dialect styles, two additional analytical tools from sociolinguistics are employed: metalinguistic awareness and positioning. Metalinguistic awareness, as articulated by

Preston (

2016), refers to an individual’s ability to reflect on language and its social implications. It involves both the capacity to comment explicitly on linguistic features and their societal significance, and an understanding of how such reflections may shape one’s own linguistic choices. In this study, metalinguistic awareness will be key to assessing the extent to which speakers recognize features such as coda /s/ lenition and the use of

voseo for the 2SG, understand the social meanings associated with these features, and how this awareness influences their decision to use or avoid these features in specific contexts.

Positioning, in turn, provides a way of examining how speakers construct and negotiate identity in interaction. As

Bamberg (

2011) argues, positioning addresses questions of self-identity (

who am I?) and identity attribution (

who are you?), accomplished through various interactional resources—including linguistic features—that signal relevant social categories in context. In this study, attention to positioning of the self and others illuminates how speakers align themselves with or distance themselves from particular social personae depending on who is present and the characteristics of those interlocutors, and how such alignments are indexed through their use—or avoidance—of specific features.

Taken together, audience design, metalinguistic awareness, and positioning offer complementary perspectives on the construction of sociolinguistic personae in context. The selection of linguistic variants, grounded in their social relevance, serves to position both speakers and hearers as members of particular groups. By integrating these frameworks within a mixed-methods approach, this study aims to show how individuals strategically deploy dialect styles to suit different audiences and contexts, offering a comprehensive account of the dynamic nature of language use in situations of dialect contact.

5. The Study

This study draws on data collected from video-recorded activities conducted between 2019 and 2020 with five adult Spanish speakers. All participants were either born in Anglo-America or immigrated to the region before the age of 10, making them second-generation Spanish speakers who have spent most, if not all, of their lives in this geographical area (

Escobar & Potowski, 2015). This inclusion criterion was essential to ensure that all participants shared a comparable experience of dialect contact, as factors such as age of arrival and length of residence can significantly influence an individual’s degree of linguistic accommodation. Importantly, all participants were fluent in Spanish and regularly used the language in both family and broader social contexts—that is, with relatives, friends, acquaintances, and coworkers. Although no formal measures of language proficiency or social networks were taken, participants were informed that all phases of the study would be conducted in Spanish with other Spanish speakers, and no one reported any discomfort with this requirement.

Regarding regional origin,

Table 1 shows that while the speakers come from diverse backgrounds, they all have roots in Spanish-speaking areas where

voseo and coda /s/ reduction are common in everyday speech. One exception is SR, whose parents are from a region of Guatemala where coda /s/ is generally preserved as a sibilant. This overall commonality allowed for an examination of both the variable use of these features in participants’ speech and their awareness of them in metalinguistic commentary.

Each speaker took part in three group activities, with full availability for all three activities serving as an additional inclusion criterion. The first activity took place in an outgroup setting, where I acted both as observer and participant. Lasting approximately 60 min, this activity consisted of a spoken parlor game in which speakers interacted with at least three individuals whose Spanish varieties differed from their own—hence the designation “outgroup”. These individuals (i.e., the audience) came from regions where coda /s/ reduction and voseo are either common or uncommon. Importantly, all audience members were either friends or close acquaintances of the speakers, and the game’s structure encouraged conversations across a wide range of topics. This format proved particularly effective for eliciting 2SG forms, which are difficult to capture in sociolinguistic interviews.

Table 2 provides details about the audience participants in the outgroup activity, including their relationship to the speaker, their region of origin, and whether coda /s/ reduction and

voseo are characteristic (Ø; V) or not (S; T) in their respective varieties.

The second activity took place in an ingroup context without my presence. For this task, each speaker took the recording equipment home and replicated the initial activity with Spanish-speaking family members and/or friends from the same region of origin, hence the designation “ingroup”.

The third and final activity occurred in an outgroup setting, bringing together the same participants from the first activity for an additional 60 min. During this meeting, participants were encouraged to share their impressions of their own dialect, highlighting features they considered salient and socially meaningful, as well as to reflect on their linguistic practices in both ingroup and outgroup contexts, such as those encountered in the first two activities.

Together, these three activities provided naturalistic data from speakers across two distinct interactional settings that mirror the audiences they interact with regularly. They also offered valuable insight into how speakers reflect on language use across contexts, resulting in a comprehensive understanding of their sociolinguistic practices.

I transcribed the recordings orthographically, writing all words verbatim and marking pauses with ellipses, as these held particular relevance for the study. Minimal instances of codeswitching to English were not considered, as the focus of the study is on Spanish features. From the conversational data, I extracted all instances of variable verbal forms corresponding to the 2SG, resulting in speaker-specific counts. In addition, I identified 202 instances of variable coda /s/ production, evenly distributed across settings (101 in each).

The 2SG tokens were classified as either

tuteo or

voseo and coded for use in outgroup or ingroup settings. Following previous research (

Carvalho, 2010;

Fernández-Mallat, 2018a), I further categorized them according to the preceding pronoun (

tú,

vos, or null) and the referent type (specific interlocutor, generic interlocutor, or reported speech). Because four of the five speakers used one variant almost exclusively in the outgroup setting, I limit the discussion of this variable to descriptive statistics.

For coda /s/ tokens, I coded realizations as either [s] or lenited ([h] or elided), confirming acoustic characteristics with

Praat (

Boersma & Weenink, 2021). In line with

Klee et al. (

2018), realization was determined by the presence of aperiodicity in the waveform and turbulence in the spectrogram, while lenition was identified by glottalized turbulence ([h]) or by the absence of turbulence and aperiodicity (elision). Like the 2SG tokens, coda /s/ tokens were coded for ingroup or outgroup use. I also followed established criteria (

Mason, 1994;

Brown & Torres Cacoullos, 2002) to classify them by following context (consonant, vowel, or pause), morphological function (verbal, nominal, or none), and syllabic stress.

Finally, to assess the factors significantly influencing coda /s/ realization, I employed mixed-effects modeling with stepwise procedures and post hoc pairwise comparisons using the packages

lme4 (

Bates et al., 2015, version 1.1.37),

car (

Fox & Weisberg, 2019, version 3.1.3), and

emmeans (

Lenth, 2025, version 1.11.2-8) in

R (

R Core Team, 2025, version 4.5.1).

From the metalinguistic commentary generated during the third activity, I identified references to salient linguistic features and examined how speakers perceive their control over these features in different settings. The goal was to assess each speaker’s understanding of voseo and coda /s/ reduction, the social relevance of these features to them, and their self-reported command of them. I then correlated this awareness and self-reported command with findings from the conversational data to draw meaningful conclusions.

6. Results

6.1. Awareness and Self-Reported Command of Voseo

The findings on voseo awareness show that all participants demonstrated metalinguistic knowledge of this feature. When asked to identify distinctive elements of their dialect, four out of five speakers named voseo as their primary marker, while one participant (GM) ranked it second after coda /s/ reduction. Their descriptions were notably detailed: some explicitly referred to the use of voseo, while others highlighted the pronoun vos.

In terms of command, all speakers reported being able to alternate between

voseo and

tuteo. The motivations behind these switches were varied and often rooted in personal, speaker-centered considerations. Participants cited factors such as the regional background of their interlocutors, the social context, the connotations associated with each variant, and the way they wished to present themselves to different audiences. Regarding the first three factors, participants’ comments reflected a heightened sensitivity to whether their interlocutors were perceived as sharing their regional background or not. This sensitivity was driven by the perception that using

voseo with individuals outside one’s ingroup could be inappropriate, making

tuteo the more acceptable choice in such contexts. This is illustrated by SR in (1) and (2), who explained that in outgroup settings—such as among colleagues from diverse regional backgrounds—she often avoided using

voseo, considering

tuteo more appropriate. However, she noted that a

tuteo-oriented style felt odd when visiting her parents.

| (1) | a. | Cuando llegaba a casa, como que le … no sé. Le decía algo a mi papá o a mi mamá y como que: “Ugh … suena súper extraño”. Y ya cambiaba al voseo y yo: “¡Ah! Está más cómodo, ¿no?” |

| | b. | When I came home, I was like … I dunno. I would say something to my dad or my mom and like: “Ugh… it sounds so weird”. And then I would switch to voseo and I was like: “Ah! That’s better, right?” |

| | | |

| (2) | a. | Tú suena más como … más proper. |

| | b. | YouT2 sounds like more … more proper. |

Regarding the fourth reason, which, as noted, relates to questions of self-presentation, speakers’ comments fall into two distinct categories. The first includes four speakers who reported avoiding

voseo when interacting with individuals perceived as outgroup members. These speakers indicated that, in such situations, they use

tuteo to promote a sense of pan-Latino unity among Spanish speakers, as illustrated by CC’s statement in (3):

| (3) | a. | Por eso escojo esa opción. Porque es la que sirve como … de manera más eh … panhispánica o algo así. |

| | b. | That’s why I choose that option. Because it’s the one that works as … in a more uhm … pan-Hispanic way, or something like that. |

The second perspective is represented by a single speaker, JMM, who reported retaining

voseo regardless of the audience. JMM described this choice as a way to assert a strong Salvadoran identity, as illustrated in statement (4):

| (4) | a. | Yo creo que es un poco como de … de identidad. Uhm … es como un … un rasgo fuerte del español salvadoreño y … no sé … me gusta usarlo porque … como te digo uhm … es como un … como algo de … de identidad. |

| | b. | I think it’s a bit like … like identity. Uhm … it’s like a … a strong feature of Salvadoran Spanish and … I don’t know … I like to use it because … as I say uhm … it’s like a … something like … like identity. |

In summary, the considerations mentioned above suggest that these speakers possess metalinguistic awareness of voseo and view its use as normal when interacting with individuals who share their dialect background. At the same time, most participants report switching to tuteo when addressing speakers from different Spanish backgrounds. Their comments reveal the existence of distinct communities of practice, understood here as the speakers’ subjective experience of boundaries between groups and framed in terms of “ingroup” and “outgroup”. Interestingly, the speakers position themselves within both communities. According to them, the choice to align with the ingroup or outgroup through the use of a particular 2SG variant depends, at least in part, on the social meanings associated with voseo and tuteo. Tuteo is considered appropriate when interacting with Spanish speakers from diverse national backgrounds, as it conveys a sense of pan-Hispanic identity—likely due to its prevalence across Spanish varieties, including those where voseo is common. In contrast, voseo is seen as more suitable in ingroup contexts, signaling regional identity and reinforcing the normalcy of interactions within this community of practice. Notably, JMM represents an exception to this pattern: their reported use of voseo across settings indicates a strong Salvadoran identity and positioning within a single community, regardless of the audience.

6.2. Use of Voseo

The results regarding the use of

voseo are consistent with speakers’ comments. As shown in

Table 3, within ingroup settings, speakers generally maintain rates of

voseo that match or closely approximate the typical regional patterns reported earlier in

Table 1. In contrast, when addressing an outgroup audience, their usage declines noticeably (GM), in some cases resulting in near suppression (CC) or even complete avoidance (SR and JM). These patterns suggest that the speakers draw onto two distinct 2SG styles, adjusting their usage according to audience and context. One notable exception is JMM, whose rates of

voseo remain stable across settings, consistent with their comments that they use

voseo to signal pride in their Salvadoran regional identity, regardless of the audience.

Notably, examining the functions of

voseo in GM’s speech across different settings reveals context-dependent patterns and a careful attention to audience composition. Although GM’s shift in

voseo use between settings is less pronounced than in the cases of SR, JM, and CC, important nuances emerge, particularly in her use of

voseo with outgroup audiences. In ingroup settings, GM uses

voseo variably: to address specific interlocutors (n = 7), to refer to generic interlocutors (n = 5), and to quote other speakers (n = 3). By contrast, in outgroup situations, she primarily uses

voseo (n = 5) to quote conversations that took place within her ingroup, as illustrated in example (5), where she quotes herself speaking to Uruguayan friends and relatives:

| (5) | a. | Cuando hablo por WhatsApp … con amigas o primas, es como que, ¿no? Es: “¡Qué salado! No sabés lo que me pasó”. |

| | b. | When I talk on WhatsApp … with friends or cousins, it’s like, right? It’s: “This is crazy! YouV wouldn’t believe what happened to me”. |

When GM does use

voseo to refer to specific interlocutors in the outgroup setting (n = 3), these interlocutors are individuals who, like her, speak a Spanish variety in which

voseo is common. This pattern suggests that GM has developed two distinct, context-adaptable 2SG styles—similarly to SR, JM, and CC—and that, when addressing an outgroup audience, she reallocates and refunctionalizes

voseo in real time, using it exclusively to address or quote speakers of

voseo varieties. It also indicates her knowledge of which Spanish varieties employ

voseo and which do not. Interestingly, CC’s single

voseo token in the outgroup setting serves the same ingroup-quoting function observed in GM’s outgroup speech, as seen in example (6), where CC quotes his Chilean cousins:

| (6) | a. | Me dicen: “[nickname]” … eh … “¿Tenís ganas de tomar cerveza?” |

| | b. | They say: “[nickname]” … uhm … “Do youV feel like having a beer?” |

To summarize, speakers’ use of voseo in this study generally aligns with their self-reports. Those who indicated that they switch to tuteo when interacting with individuals from different dialect regions generally typically do so, reflecting audience-adaptive behavior that positions them within clearly defined ingroup and outgroup practice communities. Nevertheless, some speakers continue to use voseo with outgroup audiences. A closer examination of interactional factors shows that these speakers adapt and redefine voseo use in real time, depending on the regional background of their audience or the individuals they are quoting. In doing so, they simultaneously make their ingroup visible in an outgroup context and highlight that this social positioning depends on the use of voseo. In contrast, the speaker who maintains voseo to signal regional identity does so with remarkable consistency, regardless of audience composition.

6.3. Awareness and Self-Reported Command of Coda /s/ Reduction

The findings regarding knowledge of coda /s/ reduction show that, similarly to

voseo, all four speakers who exhibit this feature in their speech demonstrated metalinguistic awareness of it. However, it was not necessarily their primary focus. With the exception of GM, who mentioned it first, the other three speakers brought it up either second, following

voseo (CC), or third, after discussing

voseo and regional lexical items (JM and JMM). Despite this, the level of detail with which speakers discussed coda /s/ reduction was comparable to that of

voseo. In fact, they not only mentioned it, as JMM does in example (7), but in some cases also provided precise observations about the phonological contexts in which coda /s/ reduction occurs, as GM illustrates in example (8):

| (7) | a. | Las eses también. Las eses … sí. |

| | b. | S’s too. S’s … yeah. |

| | | |

| (8) | a. | Como … corto … el final de las palabras … a veces. |

| | b. | Like … I cut … the endings of words … sometimes. |

In terms of their reported ability to control coda /s/ reduction—similar to their reported command of

voseo—all four speakers who exhibit this feature claimed to manipulate it consciously. Beyond noting that /s/ reduction is specific to their dialect of origin and that /s/ retention is perceived as more “neutral”, three of the speakers reported intentionally producing [s] in outgroup settings to ensure comprehension by members of that audience (JMM being the exception). This is illustrated in statement (9) by CC, who not only identified coda /s/ reduction and

voseo as characteristic features of Chilean Spanish, but also clearly explained his strategic use of two distinct dialect styles in Anglo-American contexts. Specifically, he adapts his speech in outgroup settings so that speakers of different Spanish varieties can understand him. He further demonstrated his mastery of these styles through an example in which he alternated between variants for both 2SG reference and coda /s/ production to convey his point:

| (9) | a. | Tengo un español que … que me permite comunicar con todas las personas que son eh … latinas o que hablan en … en español sin problemas, ¿no? Por eso digo que es como neutro. Pero luego tengo otro español que es un español … chileno, ¿cierto? Que … es un español obviamente que tiene los rasgos del español de Chile. Y esos sí son muy particulares. Y … y trato de no usarlos siempre porque siempre me digo: “¡Oh! ¿Y qué tal si alguien no me entiende?”, ¿no? O sea, por eso … tengo este otro español neutro. O sea, yo a mi hermano no le digo … “¿Cómo e[s]tá[s]?”. Eh … yo en el español chileno se dice: “¿Cómo e[h]tái?” |

| | b. | I have a Spanish that … that allows me to communicate with everyone that’s uhm … that’s Latino or that speaks in … in Spanish without any problems, right? That’s why I say it’s like neutral. But then I have this other Spanish that’s a … a Chilean Spanish, right? It’s … it’s a Spanish that obviously has the features of Chilean Spanish. And those are really unique. And … and I try not to use them always because I always think to myself: ‘Oh! And what if someone doesn’t understand me?’, right? I mean, that’s why … I have this other neutral Spanish. I mean, I don’t say to my brother … “How are youT?”. Uhm … I in Chilean Spanish one says: “How are youV?” |

Taken together, the speakers’ comments indicate that, like voseo, this group demonstrates metalinguistic awareness of coda /s/ reduction in their speech and generally feels confident in their ability to produce [s] when interacting with speakers of different Spanish varieties—that is, with members of an outgroup audience. This pattern was clearly illustrated by CC, who produced both variants of coda /s/ to clarify his point and explained that reduction is typical in ingroup interactions, implying that retention is expected when addressing outgroup audiences. Notably, the previously identified ingroup and outgroup communities of practice for voseo appear to operate similarly here. Speakers’ positioning within these groups seems to hinge on whether they adopt a lenition or retention style. Favoring retention is particularly important with outgroup audiences, where it facilitates comprehension between speakers of varieties in which /s/ lenition is common and those in which it is not—likely because retention is perceived as pan-Hispanic, appearing even in regions where lenition prevails. In contrast, /s/ lenition is considered regionally bounded and functions to signal alignment with the ingroup, where, as noted earlier, its use is expected and socially accepted, even though it is regarded as non-normative. Like voseo, it functions as a marker of connection and shared identity within the group.

6.4. Use of Coda /s/ Reduction

The analysis of conversational data confirms the significant influence of setting on the realization of coda /s/ among this group of speakers. As shown in

Table 4, some speakers exhibit higher-than-typical rates of /s/ reduction for their region of origin within ingroup settings, while others show lower rates. Despite this variability, all speakers consistently favor lenited variants when addressing an ingroup audience and avoid them with outgroup audiences. This pattern, similarly to 2SG reference, indicates the emergence of two distinct, context-dependent coda /s/ styles, which speakers actively employ to position themselves within the constructed ingroup and outgroup practice communities.

Further supporting evidence comes from the best-fit model presented in

Table 5, which identifies, in descending order of importance, setting (

χ2[1] = 112.39,

p < 0.001), phonological identity of the following segment (

χ2[2] = 63.33,

p < 0.001), morphological role of the variant (

χ2[2] = 19.76,

p < 0.001), and the interaction between setting and following phonological segment (

χ2[2] = 14.37,

p < 0.001) as significant predictors of coda /s/ articulation. Positive parameter estimates confirm that speakers are significantly more likely to retain /s/ in outgroup settings compared to ingroup contexts. They also show that, relative to environments where /s/ is followed by a pause or a vowel, the likelihood of /s/ realization drops considerably when the following segment is a consonant. Finally, words without a morphological role are significantly more likely to retain /s/ than those carrying a nominal or verbal function.

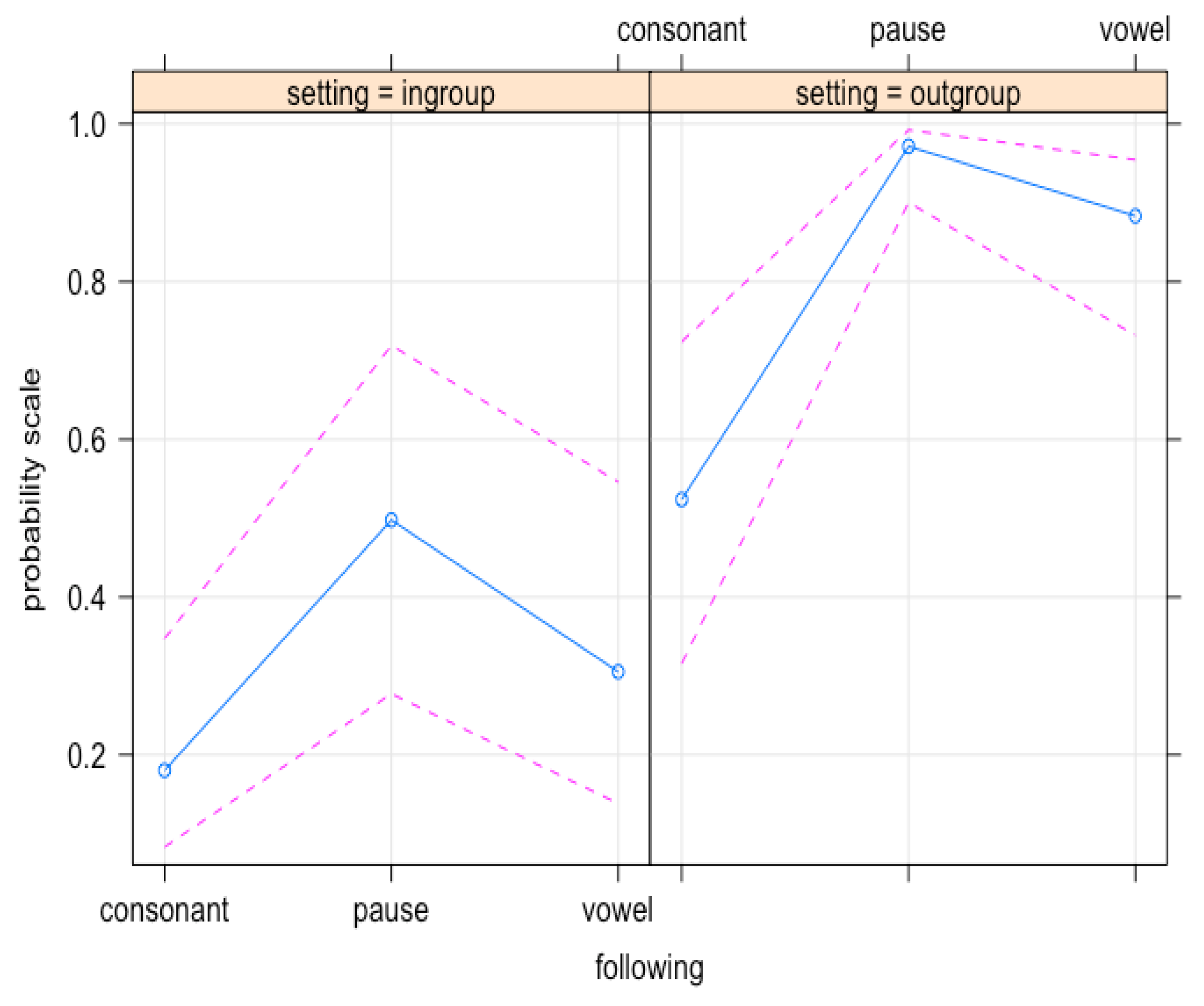

These findings highlight the central role of setting in shaping /s/ realization, not only as the strongest predictor in the model but also as part of an interaction. They further illustrate speakers’ ability to modulate their production: the emergence of distinct styles—favoring retention in outgroup settings and lenition in ingroup contexts—points to a high degree of stylistic control. At the same time, /s/ lenition remains frequent even in outgroup interactions, and the effect of the following segment is stable across settings, supporting

Aaron and Hernández’s (

2007) observation that structural continuity is generally robust in Spanish dialect contact situations. This pattern is visualized in

Figure 1, which plots the interaction on a probability scale. Unlike

voseo, which some speakers suppress entirely in the outgroup, coda /s/ is never fully controlled. Instead, its use reflects a more nuanced and sometimes elusive management of variation. As shown in the right panel of

Figure 1, the probability of /s/ retention in outgroup contexts exceeds 90% when the following segment is a pause or vowel but barely reaches 50% when followed by a consonant. Moreover, the probability ranges indicate that retention is at least twice as likely in outgroup than ingroup settings when /s/ is followed by a pause or vowel, whereas the cross-setting difference is much smaller (about 30 percentage points) when the following segment is a consonant. These patterns underscore the nuanced and partial nature of control over /s/ production: speakers exert strong control in contexts where /s/ precedes pauses or vowels, but their control is far weaker when it precedes consonants.

In summary, much like their manipulation of address forms, these speakers adeptly adjust their pronunciation of coda /s/ according to their audience. They favor lenition with ingroup interlocutors and shift toward retention with outgroup interlocutors, thereby positioning themselves within clearly defined practice communities. However, the persistence of /s/ lenition in outgroup settings underscores that this control is not absolute. Rather, it is conditioned by the following phonological environment: retention can be robustly maintained before pauses and vowels, but consonantal contexts constrain the ability to adopt a fully retention-oriented style. This stands in contrast to 2SG variants, over which speakers appear to exercise greater and more categorical control.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, I responded to calls by scholars like

Bonnici and Bayley (

2010) and

Dodsworth (

2017) to integrate recent and diverse sociolinguistic developments into the study of dialect contact, aiming to illuminate the full range of strategies speakers may employ in navigating different dialectal contexts. To this end, I adopted a mixed-methods approach, combining two sources of conversational data with metalinguistic commentary. The conversational data included interactions with speakers of the participants’ dialect of origin and interactions with speakers of diverse Spanish varieties, offering a speaker-centered perspective on dialect contact (

Fernández-Mallat & Nycz, 2024). The inclusion of metalinguistic commentary further enriched the analysis by incorporating speakers’ own reflections on their linguistic practices. Finally, the analytical framework built on recent advances to examine the extent to which individuals in dialect contact contexts—like those in non-contact contexts–develop and purposefully employ different dialect styles to position themselves within specific groups.

The conversational data indicate that these speakers have developed distinct speech styles tailored to different audiences. When interacting with speakers of their source dialects, their patterns largely mirrored those documented in previous studies on these varieties, thereby aligning themselves with an ingroup community of practice. In contrast, when engaging with speakers of other Spanish varieties, their patterns diverged significantly from those typical of their source dialects, allowing them to position themselves within an outgroup community of practice.

The metalinguistic commentary data collected during the third activity was crucial in confirming that these shifts in speech style were intentional rather than coincidental. The speakers’ reflections highlighted both their awareness of salient features of their source dialects and their deliberate choices to either employ or avoid these features depending on the audience. Overall, their style-shifting functioned as a way for positioning themselves within specific communities of practice relevant to ingroup and outgroup contexts.

While questions of self-presentation and identity, well-documented in studies on dialect styles (e.g.,

Bell, 2001;

Eckert, 1989), were certainly at play, the speakers’ motivations extended beyond identity work. Their style-shifting also reflected pragmatic concerns, particularly their desire to make communication easier (

Walker, 2024). These pragmatic considerations included fostering solidarity with ingroup audiences, ensuring mutual comprehension with outgroup audiences, and adapting to norms that render certain forms appropriate in some settings but inadequate in others.

Consistent with the broader literature on dialect styles, the speakers’ linguistic choices were influenced by the social meanings attached to particular features both in their regions of origin and across the Spanish-speaking world. Notably, voseo was perceived as more strongly tied to regional identity than coda /s/ lenition, while /s/ lenition was viewed as non-normative and potentially hindering comprehension to a greater degree than voseo. By contrast, both tuteo and /s/ retention were characterized as neutral forms with pan-Hispanic reach. These perceptions help explain why voseo was actively discussed and deployed as a regional identity marker—by speakers who reproduced it when representing ingroup speech to outgroup audiences, and by JMM, who stated they would use it and did so consistently across contexts to highlight their regional affiliation. Similarly, the association of /s/ lenition with non-normativity and the broader acceptability of /s/ retention clarify why retention was frequently discussed as a strategy for ensuring intelligibility with speakers of other varieties.

It is important to emphasize, however, that metalinguistic awareness alone did not equate to absolute control over these features. Conversational data revealed that while speakers could entirely avoid

voseo with outgroup audiences, they could not completely prevent coda /s/ lenition, even when adopting a retention-oriented style. This observation aligns with

Preston’s (

2016) claim that control is nuanced and sometimes elusive, but it warrants further explanation.

Two factors may account for this. First, not all speakers initially mentioned coda /s/ production when describing features of their source dialects, suggesting that manipulating /s/ may be less central than manipulating 2SG variants, which nearly all speakers cited first, for establishing positioning within ingroup and outgroup categories. Second, as

Chambers (

1992) notes, in dialect contact situations, speakers acquire and manipulate different types of features at varying rates. Phonological variants, such as coda /s/, often progress more slowly than morphological variants, such as 2SG reference. This difference likely arises because morphological variation, such as the choice between

voseo and

tuteo, is categorical and reflects distinct lexicalized options, whereas phonological variation, such as the realization of coda /s/, is gradient and involves fine-grained articulatory adjustments rather than the selection of discrete grammatical forms.

The data support this interpretation: /s/ retention with outgroup audiences was considerably more difficult when segments preceded consonants than when they preceded pauses or vowels, highlighting the strong effect of linguistic constraints. Taken together, the relatively greater importance of voseo for social positioning and the more limited control over coda /s/ help explain why JMM relies on the former, rather than the latter, to signal Salvadoran identity across contexts.

These findings have important implications for how accommodation and non-accommodation are typically conceptualized in dialect contact studies. Traditionally, these processes have been treated as long-term, community-based outcomes that emerge over extended periods of contact or across generations in diaspora contexts. By contrast, the evidence presented here, grounded in a speaker-centered perspective, shows that the speakers in this study cannot be neatly categorized as either fully accommodating their speech to others or permanently resisting accommodation. Rather, as revealed through their navigation of ingroup and outgroup contexts as well as their metalinguistic reflections, accommodation and non-accommodation emerge as situational and momentary practices. Speakers employ them purposefully to position themselves within different groups, drawing on adaptive communicative resources. While factors such as arrival age, length of stay, attitudes, and linguistic constraints continue to influence the acquisition of “new” features—as traditionally observed—these factors do not necessarily lead to the loss of “old” ones.

This is not to say that permanent accommodation does not occur in dialect contact settings, nor that some individuals never replace “old” features with “new” ones. Both possibilities remain valid. For instance, JMM’s consistent use of voseo regardless of setting or interlocutor background exemplifies the latter. The goal here has been to complicate the conventional view that accommodation and non-accommodation are fixed, long-term outcomes of dialect contact. Whereas community-based approaches, often grounded in traditional sociolinguistic interviews, have effectively captured such trajectories, the speaker-based, mixed-methods approach adopted here offers a complementary perspective. By drawing on both conversational data and metalinguistic commentary, it shows how speakers with extensive experience in contact settings demonstrate sophisticated style-shifting abilities. These abilities allow them to alternate between styles in which accommodation predominates and those in which non-accommodation prevails, thereby positioning themselves flexibly across different communities of practice. In this way, the present findings both acknowledge the insights of prior work and highlight the added value of focusing on speaker agency in dialect contact.

Future research could expand this line of inquiry by comparing the adaptive, context-dependent practices observed here with those of speakers from more diverse immigrant backgrounds—for instance, individuals who arrive later in life, have shorter durations of stay, or are first-generation immigrants. It would also be valuable to investigate whether the outcomes reported here are specific to contexts in which dialect and language contact coincide amid ongoing migration. Such contexts differ from the scenarios described in

Trudgill’s (

2004) three-stage model of new-dialect formation in former British colonies, where settler populations were predominantly monolingual and migration eventually ceased. In both cases, accommodation may foster a sense of community among speakers of different varieties; however, in contexts of ongoing migration, maintaining one’s source dialect may be especially important due to sustained opportunities for interaction with newly arrived speakers of that variety.

At the same time, these findings contribute to broader efforts to disentangle dialect contact from language contact in contexts where both operate. The data suggest that dialect contact exerts a stronger influence on speakers’ choices, though language contact remains significant. Speakers draw not only on features from their source varieties but also from other varieties, manipulating them to tailor their styles to different audiences. Still, this hypothesis requires further testing with less widely available features, such as SPE, which were not mentioned by the study’s participants. Prior research shows that not all contact features behave similarly in dialect contact settings; speakers primarily mobilize those with strong social salience (

Nycz, 2018). Features with limited availability and weaker indexical potential may thus be more susceptible to the pressures of language contact than those more readily accessible and tied to salient social meanings. This represents a promising direction for future research.

In sum, this study underscores the value of adopting a speaker-based approach to dialect contact, complemented by a mixed-methods design that foregrounds speakers’ agency in shaping their language practices within multidialectal spaces. Such an approach brings into focus the complexity and contextual variability of speakers’ adaptive repertoires while also advancing key debates on the dynamics of accommodation, style-shifting, and the interplay between dialect and language contact.