The Targetedness of English Schwa: Evidence from Schwa-Initial Minimal Pairs

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Variability in English Schwa

1.2. Eliciting Hyperarticulation of Schwa Targets

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Procedure

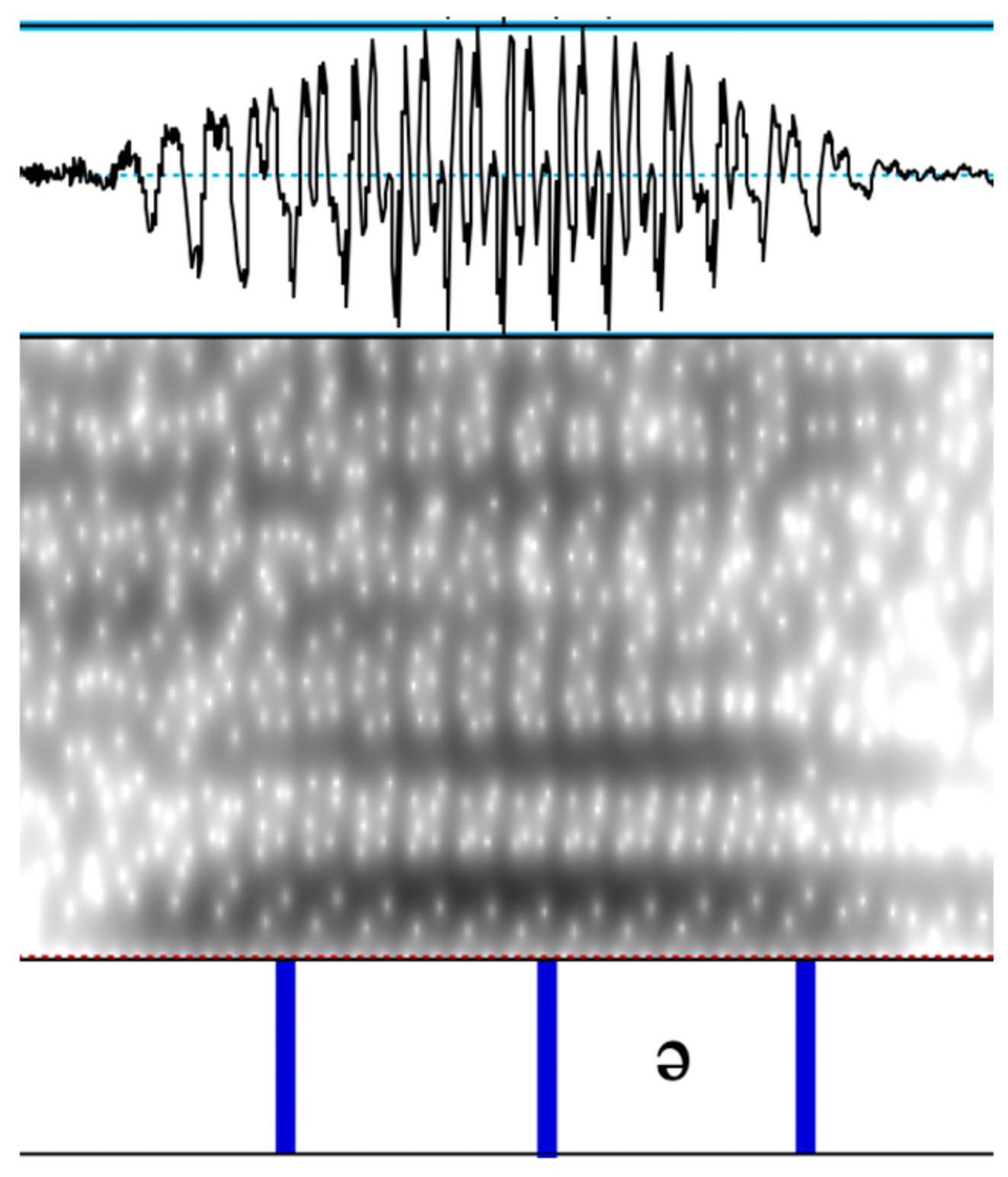

2.4. Data Processing

2.5. Model Building

3. Results

3.1. Midpoint and Duration Analyses

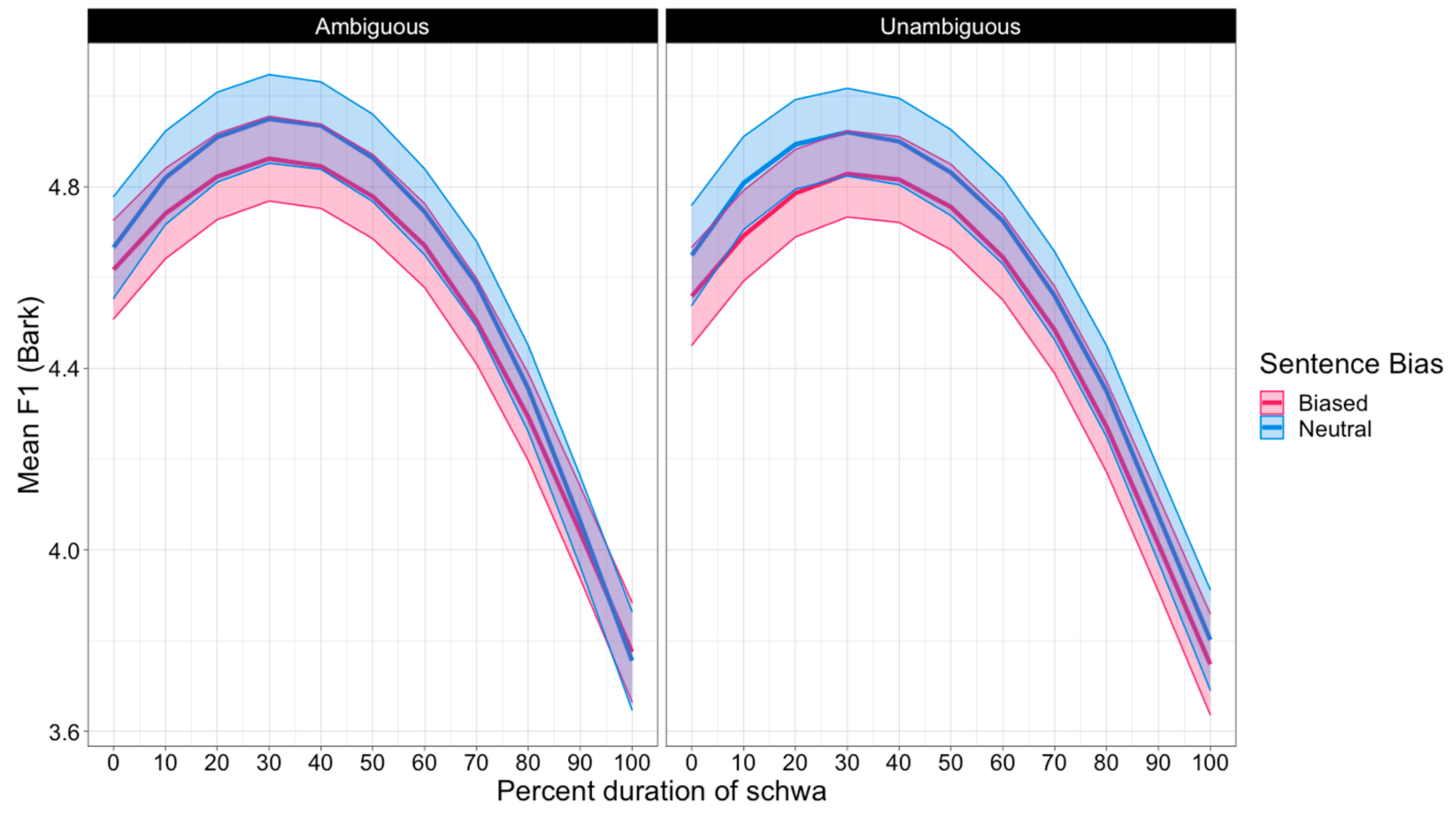

3.2. F1 Trajectory

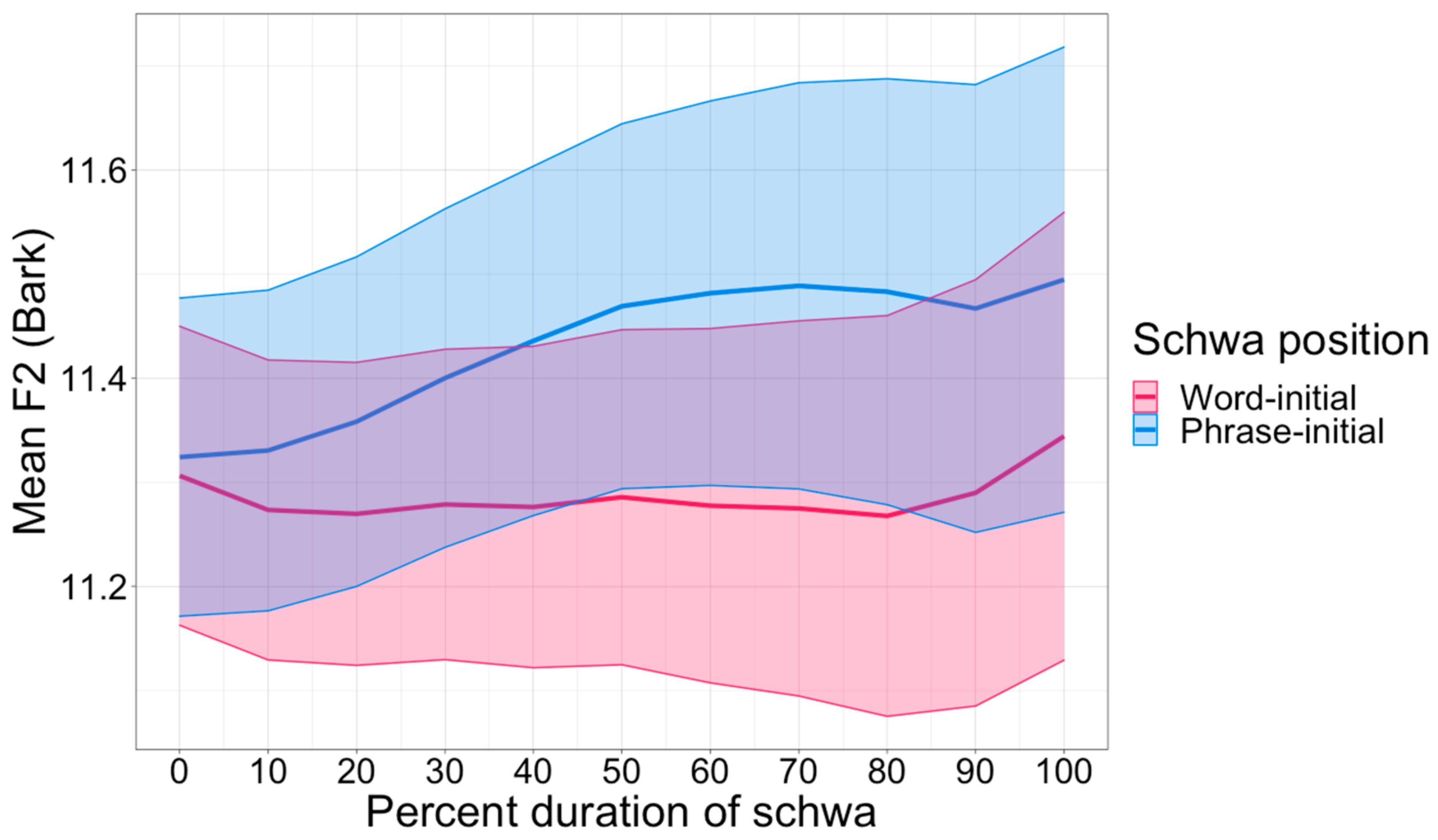

3.3. F2 Trajectory

4. Discussion

4.1. Targetedness of Word-Initial and Phrase-Initial Schwas in English

4.2. Hyperarticulation of Word-Initial and Phrase-Initial Schwas in English

4.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Ambiguity | Word/Phrase | Neutral Sentence | Biased Sentence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ambiguous | accompany | The man was sent to accompany a young lady. | The bodyguard had to accompany a celebrity. |

| a company | The man was sent to a company in New Orleans. | Workers are drawn to a company of high standards. | |

| Unambiguous | accomplish | The man was sent to accomplish a lofty goal. | The goal he set out to accomplish was finally complete. |

| a comic | The man was sent to a comic shop in New York. | The nerd loved to go to a comic store around the corner. | |

| Ambiguous | acquire | John was sent to acquire new skills. | The collectors wanted to acquire new items. |

| a choir | John was sent to a choir near Kentucky. | The singers belong to a choir near Kentucky. | |

| Unambiguous | aquatic | John was sent to aquatic nursing school. | The fish were brought to aquatic nurseries to grow. |

| a quiet | John was sent to a quiet nation for work. | The librarian walked to a quiet nearby room. | |

| Ambiguous | acute | The teenaged girl had acute kidney disease. | The doctor said he had acute colon cancer. |

| a cute | The teenaged girl had a cute kitten in her arms. | The girl had a cute collection of dolls. | |

| Unambiguous | acuity | The teenaged girl had acuity kids did not usually have. | The eye doctor said he had acuity comparable to a teenager. |

| a cube | The teenaged girl had a cube kept on her dresser. | The engineer had a cube collection on their desk. | |

| Ambiguous | adore | The servant came to adore every puppy. | Lovers are meant to adore each other. |

| a door | The servant came to a door in the basement. | The hallway leads to a door at the end. | |

| Unambiguous | adorn | The servant came to adorn the crown with jewels. | The jewels were used to adorn the queen’s crown. |

| a tour | The servant came to a tour of the house. | The band planned to do a tour of the world. | |

| Ambiguous | affair | She didn’t know what affair Dave was involved in. | The adulterer asked what affair Diane was talking about. |

| a fair | She didn’t know what a fair deal would be. | The judge should know what a fair deal should be. | |

| Unambiguous | effect | She didn’t know what effect Dean would have on the project. | The scientist should know what effect deer have on mice populations. |

| a fake | She didn’t know what a fake dealer may sell her. | A scammer must know what a fake deed looks like. | |

| Ambiguous | allowed | I think Janet might have allowed Sue to go. | The government has allowed so much corruption. |

| a loud | I think Janet might have a loud singing voice. | The rock singer has a loud sound system. | |

| Unambiguous | alarms | I think Janet might have alarms so that she wakes up. | The firehouse has alarms sounding constantly. |

| a lounge | I think Janet might have a lounge space in her house. | The night club has a lounge so clients can escape the noise. | |

| Ambiguous | attuning | The young man recently heard attuning various senses would help his spy career. | The spy would need to stop attuning his senses to this scenario. |

| a tuning | The young man recently heard a tuning violinist in the distance. | The musician should stop a tuning fork from playing that note. | |

| Unambiguous | assuming | The young man recently heard assuming violence would occur is bad. | The judge would need to stop assuming both parties were being honest. |

| a tubing | The young man recently heard a tubing venue was to be built nearby. | The skiers wanted to stop a tubing hill from being built. | |

| Ambiguous | attacks | They always claim that attacks largely happen at night. | It’s a vicious bear that attacks like lightning. |

| a tax | They always claim that a tax levy would help. | The IRS told us that a tax law had changed. | |

| Unambiguous | attachment | They always claim that attachment like that makes team building easier. | The mother said that attachment like the one to her son kept her going. |

| a tap | They always claim that a tap lightly on the shoulder could wake her up. | The fighter said that a tap leveled on the head would knock someone out. | |

| Ambiguous | aside | Meghan quickly took aside the children under 10. | The trainer took aside the boxer and yelled at him. |

| a side | Meghan quickly took a side that the others disagreed with. | The president took a side that was popular in debates. | |

| Unambiguous | asylum | Meghan quickly took asylum there in a different country. | The refugee took asylum that was offered in the country. |

| a size | Meghan quickly took a size that was too big. | The clerk took a size that was too small off the rack. | |

| Ambiguous | arose | Michael said the thought that arose could not have been more brilliant. | The film had zombies that arose quickly from the dead. |

| a rose | Michael said the thought that a rose could bloom here is strange. | No flower says the things a rose could say. | |

| Unambiguous | aromas | Michael said the thought that aromas could be this bad was surprising. | The old bakery had aromas that are second to none. |

| a road | Michael said the thought that a road could be this bumpy is ridiculous. | The potholes that filled a road says a lot about the government. |

Appendix B

| Model Term | Estimate | SE | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.8122 | 0.069 | 69.588 | <0.001 |

| Bias | −0.0300 | 0.010 | −2.899 | <0.01 |

| Ambiguity | 0.0051 | 0.040 | 0.130 | 0.897 |

| Schwa position | −0.0156 | 0.035 | −0.442 | 0.659 |

| Duration | 6.6345 | 0.328 | 20.253 | <0.001 |

| Frequency | 0.0150 | 0.020 | 0.738 | 0.463 |

| Bias × ambiguity | −0.0024 | 0.010 | −0.235 | 0.816 |

| Bias × schwa position | −0.0003 | 0.010 | −0.033 | 0.974 |

| Ambiguity × schwa position | −0.0214 | 0.031 | −0.698 | 0.0487 |

| Bias × ambiguity × schwa position | 0.0015 | 0.010 | 0.150 | 0.881 |

| Model Term | Estimate | SE | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 11.372 | 0.173 | 65.908 | <0.001 |

| Bias | 0.023 | 0.019 | 1.196 | 0.239 |

| Ambiguity | −0.054 | 0.100 | −0.538 | 0.591 |

| Schwa position | −0.025 | 0.073 | −0.338 | 0.736 |

| Duration | 2.630 | 0.437 | 6.019 | <0.001 |

| Frequency | −0.033 | 0.045 | −0.737 | 0.461 |

| Bias × ambiguity | 0.023 | 0.018 | 1.290 | 0.204 |

| Bias × schwa position | 0.011 | 0.017 | 0.674 | 0.504 |

| Ambiguity × schwa position | −0.021 | 0.062 | −0.348 | 0.728 |

| Bias × ambiguity × schwa position | −0.011 | 0.017 | −0.679 | 0.500 |

| Model Term | Estimate | SE | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.0636 | 0.002 | 31.889 | <0.001 |

| Bias | −0.0016 | 0.001 | −2.329 | 0.025 |

| Ambiguity | 0.0004 | 0.001 | 0.276 | 0.784 |

| Schwa position | −0.002 | 0.001 | −1.571 | 0.119 |

| Frequency | −0.0004 | 0.001 | −0.485 | 0.629 |

| Bias × ambiguity | −0.0001 | 0.001 | −0.216 | 0.830 |

| Bias × schwa position | −0.0002 | 0.001 | −0.452 | 0.653 |

| Ambiguity × schwa position | −0.0004 | 0.001 | −0.315 | 0.753 |

| Bias × ambiguity × schwa position | −0.0002 | 0.001 | −0.302 | 0.764 |

| 1 | We assume a continuum in production from hyperarticulation (i.e., enhancement) to hypoarticulation (i.e., reduction). The manipulations in the current study were intended to affect the relative degree of hyperarticulation (more vs. less) along this continuum. |

| 2 | The model specification for the GCA for F1 was as follows: f1.bark ~ (poly1 + poly2) * bias * ambiguity * schwa.position + frequency + duration + (poly1 | subject) + (1 | subject:bias) + (1 | subject:ambiguity) + (1 | subject:schwa.position) + (poly1 | word) + (1 | word:bias). |

| 3 | The model specification for the GCA for F2 was as follows: f2.bark ~ (poly1 + poly2) * bias * ambiguity * schwa.position + frequency + duration + (1 | subject) + (1 | subject:bias) + (1 | subject:schwa.position) + (1 | word) + (1 | word:bias). |

References

- Aylett, Matthew, and Alice Turk. 2004. The smooth signal redundancy hypothesis: A functional explanation for relationships between redundancy, prosodic prominence, and duration in spontaneous speech. Language and Speech 47: 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baayen, R. Harald, Richard Piepenbrock, and Leon Gulikers. 1995. CELEX2 LDC96L14 [Web Downloaded]. Linguistics Data Consortium. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baese-Berk, Melissa, and Matthew Goldrick. 2009. Mechanisms of interaction in speech production. Language and Cognitive Processes 24: 527–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, Rachel E., and Ann R. Bradlow. 2009. Variability in word duration as a function of probability, speech style, and prosody. Language and Speech 52: 391–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakst, Sarah, and Caroline A. Niziolek. 2021. Effects of syllable stress in adaptation to altered auditory feedback in vowels. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 149: 708–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, William J. 1998. Time as a factor in the acoustic variation of schwa. Paper presented at the 5th International Conference on Spoken Language Processing, Sydney, Australia, November 30–December 4; pp. 3071–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Sally A. R. 1995. Towards a Definition of Schwa: An Acoustic Investigation of Vowel Reduction in English. Doctoral thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, Paul, and David J. M. Weenink. 2014. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer (5.3.84) [Computer Software]. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 4 October 2020).

- Booji, Geert. 1995. The Phonology of Dutch. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Browman, Catherine P., and Louis Goldstein. 1992. “Targetless” schwa: An articulatory analysis. In Papers in Lanoratory Phonology II: Gesture, Segment, Prosody. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 26–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdin, Rachel S., Rory Turnbull, and Cynthia G. Clopper. 2015. Interactions among lexical and discourse characteristics in vowel production. Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics 22: 060005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buz, Esteban, Michael K. Tenenhaus, and T. Florian Jaeger. 2016. Dynamically adapted context-specific hyper-articulation: Feedback from interlocutors affects speakers’ subsequent pronunciations. Journal of Memory and Language 89: 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, Sasha. 2010. How does informativeness affect prosodic prominence? Language and Cognitive Processes 27: 1099–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Shuwen, and Peggy P. K. Mok. 2019. Speech production of rhotics in highly proficient bilinguals: Acoustic and articulatory measures. Paper presented at the 19th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Melbourne, Australia, August 5–9; pp. 1818–22. [Google Scholar]

- Clopper, Cynthia G., and Janet B. Pierrehumbert. 2008. Effects of semantic predictability and regional dialect on vowel space reduction. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 124: 1682–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clopper, Cynthia G., and Rory Turnbull. 2018. Exploring variation in phonetic reduction: Linguistic, social, and cognitive factors. In Rethinking Reduction: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Conditions, Mechanisms, and Domains for Phonetic Variation. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 25–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen Priva, Uriel, and Emily Strand. 2023. Schwa’s duration and acoustic position in American English. Journal of Phonetics 96: 101198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Mark. 2008. The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). Available online: https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Dorman, Michael F., Michael Studdert-Kennedy, and Lawrence J. Raphael. 1977. Stop-consonant recognition: Release bursts and formant transitions as functionally equivalent, context-dependent cues. Perception and Psychophysics 22: 109–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, Edward, and Stephanie Johnson. 2007. Rosa’s roses: Reduced vowels in American English. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 37: 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, Edward. 2009. The phonetics of schwa vowels. Phonological Weakness in English 493: 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahl, Susanne, and Susan M. Garnsey. 2004. Knowledge of Grammar, Knowledge of Usage: Syntactic Probabilities Affect Pronunciation Variation. Language 80: 748–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahl, Susanne. 2015. Lexical competition in vowel articulation revisited: Vowel dispersion in the Easy/Hard database. Journal of Phonetics 49: 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, Jason, Matthew B. Winn, Tristian Mahr, and Daniel Mirman. 2020. GazeR: A Package for Processing Gaze Position and Pupil Size Data. Behavior Research Methods 52: 2232–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gick, Bryan. 2002. An X-ray investigation of pharyngeal constriction in American English schwa. Phonetica 59: 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand, James, and Robert T. Gayvert. 1993. Identification of steady-state vowels synthesized from the Peterson and Barney measurements. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 94: 668–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillenbrand, James, Laura A. Getty, Michael J. Clark, and Kimberlee Wheeler. 1995. Acoustic characteristics of American English vowels. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 97: 3099–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillenbrand, James, Michael J. Clark, and Terrance M. Nearey. 2001. Effects of consonant environment on vowel formant patterns. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 109: 748–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillenbrand, James. 2013. Static and Dynamic Approaches to Vowel Perception. In Vowel Inherent Spectral Change, 1st ed. Berlin: Springer, pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, Patricia A. 1988. Underspecification in Phonetics. Phonology 5: 275–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Dahee, Joseph D. W. Stephens, and Mark A. Pitt. 2012. How does context play a part in splitting words apart? Production and perception of word boundaries in casual speech. Journal of Memory and Language 66: 509–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, Yuko. 1994. Targetless schwa: Is that how we get the impression of stress-timing in English? Paper presented at the Edinburgh Linguistics Department Conference ’94, Edinburgh, UK, May 26–27; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans-Van Benium, Florian J. 1994. What’s in a schwa? Durational and spectral analysis of natural continuous speech and diphones in Dutch. Phonetica 51: 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, Alexandra, Per B. Brockhoff, and Rune H. B. Christensen. 2017. lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. Journal of Statistical Software 82: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, Alvin M., Pierre C. Delattre, Franklin S. Cooper, and Louis J. Gerstman. 1954. The role of consonant-vowel transitions in the perception of the stop and nasal consonants. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied 68: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, Phillip. 1963. Some Effects of Semantic and Grammatical Context on the Production and Perception of Speech. Language and Speech 6: 172–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilley, Jason. 2012. The Characterization of Phonetic Variation in American English Schwa Using Hidden Markov Models. Doctoral thesis, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mirman, Daniel, James A. Dixon, and James S. Magnuson. 2008. Statistical and computational models of the visual world paradigm: Growth curves and individual differences. Journal of Memory and Language 59: 475–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Seung-Jae, and Björn Lindblom. 1994. Interaction between duration, context, and speaking style in English stressed vowels. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 96: 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, Benjamin, and Nancy P. Solomon. 2004. The Effect of Phonological Neighborhood Density on Vowel Articulation. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 47: 1048–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nusbaum, Howard, David B. Pisoni, and Christopher K. Davis. 1984. Sizing up the Hoosier Mental Lexicon: Measuring the familiarity of 20,000 words. In Research on Speech Perception Progress Report No. 10. Bloomington: Speech Research Laboratory, Indiana University, vol. 10, pp. 357–76. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Gordon E., and Ilse Lehiste. 1960. Duration of Syllable Nuclei in English. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 32: 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfarth, Scott. 2014. Word informativity influences acoustic duration: Effects of contextual predictability on lexical representation. Cognition 133: 140–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Ping, Ivan Yuen, Nan X. Rattanasone, Liqun Gao, and Katherine Demuth. 2019. Acquisition of weak syllables in tonal languages: Acoustic evidence from neutral tone in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Child Language 46: 24–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traunmüller, Hartmut. 1990. Analytical expressions for the tonotopic sensory scale. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 88: 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bergem, Dick R. 1994. A model of coarticulatory effects on the schwa. Speech Communication 14: 143–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, Richard. 1986. Schwa and the structure of words in German. Linguistics 24: 697–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Richard. 2004. Factors of lexical competition in vowel articulation. In Phonetic Interpretation: Papers in Laboratory Phonology, VI. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ambiguous | Unambiguous | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Word-Initial | Phrase-Initial | Word-Initial | Phrase-Initial |

| accompany | a company | accomplish | a comic |

| acquire | a choir | aquatic | a quiet |

| acute | a cute | acuity | a cube |

| adore | a door | adorn | a tour |

| affair | a fair | effect | a fake |

| allowed | a loud | alarms | a lounge |

| attuning | a tuning | assuming | a tubing |

| attacks | a tax | attachment | a tap |

| aside | a side | asylum | a size |

| arose | a rose | aroma | a road |

| Model Term | Estimate | SE | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.574 | 0.069 | 66.728 | <0.001 |

| Poly 1 (linear term) | −0.927 | 0.074 | −12.505 | <0.001 |

| Poly 2 (quadratic term) | −0.724 | 0.008 | −90.261 | <0.001 |

| Bias | −0.029 | 0.012 | −2.477 | 0.01 |

| Ambiguity | −0.025 | 0.027 | −0.935 | 0.350 |

| Schwa position | −0.001 | 0.021 | −0.052 | 0.958 |

| Frequency | −0.011 | 0.012 | −0.882 | 0.378 |

| Duration | 4.366 | 0.114 | 38.249 | <0.001 |

| Linear × bias | 0.031 | 0.008 | 3.878 | <0.001 |

| Quadratic × bias | 0.023 | 0.008 | 2.848 | <0.01 |

| Linear × ambiguity | −0.010 | 0.049 | −0.212 | 0.833 |

| Quadratic × ambiguity | −0.008 | 0.008 | −0.944 | 0.345 |

| Bias × ambiguity | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.803 | 0.426 |

| Linear × schwa position | 0.012 | 0.039 | 0.304 | 0.762 |

| Quadratic × schwa position | 0.023 | 0.008 | 2.861 | <0.01 |

| Bias × schwa position | −0.008 | 0.009 | −0.899 | 0.372 |

| Ambiguity × schwa position | −0.020 | 0.016 | −1.205 | 0.229 |

| Linear × bias × ambiguity | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.288 | 0.773 |

| Quadratic × bias × ambiguity | 0.020 | 0.008 | 2.491 | 0.012 |

| Linear × bias × schwa position | −0.009 | 0.008 | −1.214 | 0.225 |

| Quadratic × bias × schwa position | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.727 | 0.468 |

| Linear × ambiguity × schwa position | 0.004 | 0.037 | 0.103 | 0.918 |

| Quadratic × ambiguity × schwa position | −0.008 | 0.008 | −1.005 | 0.315 |

| Bias × ambiguity × schwa position | −0.002 | 0.008 | −0.238 | 0.813 |

| Linear × bias × ambiguity × schwa position | 0.018 | 0.008 | 2.265 | 0.023 |

| Quadratic × bias × ambiguity × schwa position | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.377 | 0.706 |

| Model Term | Estimate | SE | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 11.220 | 0.181 | 62.081 | <0.001 |

| Poly 1 (linear term) | 0.106 | 0.011 | 9.815 | <0.001 |

| Poly 2 (quadratic term) | −0.012 | 0.011 | −1.102 | 0.271 |

| Bias | 0.018 | 0.0230 | 0.779 | 0.440 |

| Ambiguity | −0.052 | 0.0427 | −1.224 | 0.221 |

| Schwa position | −0.032 | 0.036 | −0.892 | 0.373 |

| Frequency | 0.038 | 0.019 | 2.010 | 0.044 |

| Duration | 1.985 | 0.153 | 13.003 | <0.001 |

| Linear × bias | −0.031 | 0.011 | −2.841 | 0.005 |

| Quadratic × bias | 0.014 | 0.011 | 1.300 | 0.194 |

| Linear × ambiguity | 0.022 | 0.011 | 2.058 | 0.040 |

| Quadratic × ambiguity | −0.006 | 0.011 | −0.545 | 0.586 |

| Bias × ambiguity | 0.042 | 0.020 | 2.140 | 0.037 |

| Linear × schwa position | −0.084 | 0.011 | −7.844 | <0.001 |

| Quadratic × schwa position | 0.058 | 0.011 | 5.401 | <0.001 |

| Bias × schwa position | −0.013 | 0.016 | −0.805 | 0.423 |

| Ambiguity × schwa position | −0.017 | 0.025 | −0.680 | 0.497 |

| Linear × bias × ambiguity | −0.014 | 0.011 | −1.314 | 0.187 |

| Quadratic × bias × ambiguity | −0.017 | 0.011 | −1.560 | 0.119 |

| Linear × bias × schwa position | −0.004 | 0.011 | −0.373 | 0.709 |

| Quadratic × bias × schwa position | −0.006 | 0.011 | −0.555 | 0.579 |

| Linear × ambiguity × schwa position | 0.033 | 0.011 | 3.103 | 0.002 |

| Quadratic × ambiguity × schwa position | −0.006 | 0.011 | −0.608 | 0.543 |

| Bias × ambiguity × schwa position | −0.001 | 0.015 | −0.046 | 0.963 |

| Linear × bias × ambiguity × schwa position | 0.022 | 0.011 | 2.047 | 0.040 |

| Quadratic × bias ambiguity × schwa position | 0.011 | 0.011 | 1.041 | 0.298 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Napoli, E.R.; Clopper, C.G. The Targetedness of English Schwa: Evidence from Schwa-Initial Minimal Pairs. Languages 2024, 9, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9040130

Napoli ER, Clopper CG. The Targetedness of English Schwa: Evidence from Schwa-Initial Minimal Pairs. Languages. 2024; 9(4):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9040130

Chicago/Turabian StyleNapoli, Emily R., and Cynthia G. Clopper. 2024. "The Targetedness of English Schwa: Evidence from Schwa-Initial Minimal Pairs" Languages 9, no. 4: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9040130

APA StyleNapoli, E. R., & Clopper, C. G. (2024). The Targetedness of English Schwa: Evidence from Schwa-Initial Minimal Pairs. Languages, 9(4), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9040130