Abstract

A rich tradition of studies on languages with differential object marking (DOM) is available in the literature. Languages like Spanish or Romanian are frequently cited in discussions about DOM, but Valencian is seldom mentioned in this context. This oversight may stem from a lack of familiarity with the Valencian language and an over-reliance on guidelines set by textbooks and official prescriptive grammars—in the case of Valencian, by the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua—which drafts the linguistic regulations of the Valencian language. This study aimed to analyze the usage of the DOM in Valencian and explore the social variables that help explain this usage (sex, age, and education). To achieve this goal, Spanish–Valencian bilingual participants completed an oral production task to evaluate their use of DOM in Valencian. Statistical analysis revealed that Valencian is a DOM language that marks direct objects that refer to humans and definite entities. These results point to the linguistic ideologies in Valencia that attempt to artificially create linguistic differentiation between Valencian and Spanish, the co-official languages in the region. Furthermore, the results emphasize the limitations of top-down prescriptive policies in modifying vernacular linguistic varieties.

1. Introduction

Individuals often refer to grammar manuals to improve their understanding of the languages they are studying. However, when exploring minority languages embroiled in political, linguistic, and identity conflicts, such as the Valencian language, exercising heightened caution becomes imperative because information found in grammar manuals may not serve as reliable descriptors of these languages. These grammars can pose challenges in accurately reflecting the linguistic practices of native speakers.

In recent years, an interest in the languages of Spain, including Valencian, has been observed (Davidson 2022; De la Fuente Iglesias and Pérez Castillejo 2022; Iranzo 2021). The studies stemming from this interest span various areas, including language ideologies in the educational domain (Iranzo 2021). In the Valencian Community, critiques within educational discourse often revolve around the stigmatization of the vernacular varieties of the Valencian language. However, a lack of empirical studies addressing the description of Valencian linguistic varieties and the impact of schooling prevails. The present study aims to fill this gap by examining differential object marking (DOM) in Valencian.

Only certain languages exhibit the marking of direct objects, but not others (Aissen 2003). Within the Romance language group, DOM is evident in several languages, including Spanish and Romanian (Irimia and Mardale 2023; Mardale and Karatsareas 2020; Montrul et al. 2015; von Heusinger and Kaiser 2007). For example, DOM in Spanish is lexicalized in the fake preposition “a” (López Otero 2020). The direct object la mujer ‘the woman‘ is marked with the fake preposition “a” in the sentence Veo a la mujer en la biblioteca ‘I see the woman in the library’ since the direct object is definite (introduced by a definite determiner) and human (la mujer ‘the woman’). The acquisition of DOM has been explored in diverse linguistic contexts, such as first language acquisition, including heritage languages (Arechabaleta Regulez and Montrul 2023; Hur 2020; Jegerski and Sekerina 2020; Montrul et al. 2015; Montrul and Sánchez-Walker 2013; Rodríguez-Mondoñedo 2008; Thane 2024), and second language contexts (Bowles and Montrul 2009; Guijarro-Fuentes and Marinis 2007; López Otero 2020, 2022; López Otero and Jimenez 2022).

In the case of Valencian, the corpus Museu de la Paraula ‘Museum of the Word’ (Diputació de Valencia n.d.) provides insights into the vernacular use of DOM in the Valencian language. However, it is important to note that all contributors to the corpus were born before the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). Therefore, the corpus cannot inform us about the use of DOM in younger generations. Below are four excerpts from videos showing the use of the fake preposition “a” employed specifically to mark human and definite direct objects, the central theme of this study. All videos were filmed in the province of Valencia, the geographical focus of the present study. The text in parentheses indicates the filename, including the city where the video was recorded. The text in bold indicates the verb along with the fake preposition “a”, used to mark direct objects that are definite and human: visitar al malalts, ‘to visit the sick’; vorer a les xiquetes, ‘to see the girls’; conéixer a la dona, ‘to know the woman’; and portar als metges, ‘to bring the doctors’.

- És visitar al malalt i beneir-lo o lo que fóra (MOMO12-Llutxent-D29)

- Veníem a vore a les xiquetes (MOR158-València-H36)

- Com coneix a la dona (MOTO26-Palmera-H30)

- I entonces portaren als metges (MOOR04-Beneixida-D37)

Given its different classification as a DOM language across grammar norms, the case of the Valencian language presents a unique opportunity for study. Instructional materials in Valencian schools may diverge from the linguistic practices of native speakers, potentially influencing the usage of DOM among Valencian speakers. The present study includes Valencian–Spanish bilingual speakers and utilizes a production task—a methodology employed in previous studies on DOM (Arechabaleta Regulez and Montrul 2021; Montrul and Sánchez-Walker 2013)—to assess their productive knowledge.

This article is organized as follows: The literature review describes DOM in Valencian and Spanish and introduces previous publications on prescriptivism and linguistic differentiation. The third section outlines the research questions and methodology applied in the current study, followed by a review of the study’s results, and finally, a discussion in the concluding section.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Differential Object Marker in Valencian and Spanish

DOM is observed in various languages (Aissen 2003; Bossong 1991). It involves marking arguments with greater semantic or pragmatic prominence than their unmarked counterparts (Montrul and Sánchez-Walker 2013). This distinctive marking of direct objects manifests through various means (Bautista Maldonado and Montrul 2019). Aissen (2003) proposed a two-factor scale influencing DOM, specifically animacy and specificity, as shown below:

- Animacy scale: Human > Animate > Inanimate.

- Definiteness scale: Personal pronoun > Proper name > Definite nominal phrase (NP) > Indef. specific NP > Non-specific NP.

For example, direct objects in Spanish with high prominence on the mentioned scale are explicitly marked (Cuza et al. 2019). Consider these two sentences in Spanish: Sergio visita a la doctora ‘Sergio visits the doctor’ vs. Sergio visita una galería ‘Sergio visits a gallery’. In the first sentence, la doctora ‘the doctor’ (human, definite NP) is marked with the fake preposition “a”. However, una galería ‘a gallery’ (non-human, non-definite NP) is not marked. This study focuses on transitive verbs accompanied by human and non-human definite direct objects (el bebé ‘the baby’, la porta ‘the door’) in the Valencian language.

According to the Statute of Autonomy of the Valencian Community in Spain, the region has two official languages: Spanish and Valencian. Two distinct organizations supervise standardization efforts for the Valencian language. The Real Acadèmia de Cultura Valenciana (RACV) was established in 1915, and the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua (AVL) was founded in 1998. Currently, the official grammar of the Valencian language is determined by the AVL. Both academies include DOM in Valencian in their respective normative grammars. The RACV grammar (Arlandis et al. 2015) states:

El complement directe personal generalment va introduït per la preposició a, la qual permet diferenciar clarament el subjecte del complement directe de persona, inclús quan este ocupa la posició posverbal.(p. 510)

The personal direct object is generally introduced by the preposition “a”, which allows for a clear distinction between the subject and the direct object of a person, even when the direct object occupies the post-verbal position.(p. 510)

The grammar of the RACV also includes normative examples, such as the following:

| Lo primer | és | socórrer | als cavallers |

| The first | is | to help | DOM the gentlemen. |

| ‘The first thing is to help the gentlemen.’ | |||

Because RACV grammar is not taught in Valencian schools, textbooks tend to overlook its guidelines.

However, this RACV norm does not match AVL grammar. The Valencian grammar published by the AVL (2006) asserts that la forma del sintagma nominal és manté tant si el CD és animat com si és inanimat ‘the form of the nominal phrase remains the same whether the direct object is animate or inanimate’ (p. 303). The AVL grammar provides several examples, including the following:

| Els pares | besen | els seus fills. |

| The parents | kiss | the their children. |

| ‘The parents kiss their children.’ | ||

According to AVL guidelines, direct objects that are both definite and human (els seus fills ‘their kids’) typically do not require the fake preposition “a”. This rule is explicitly stated in prescriptive language texts, such as reference grammars.

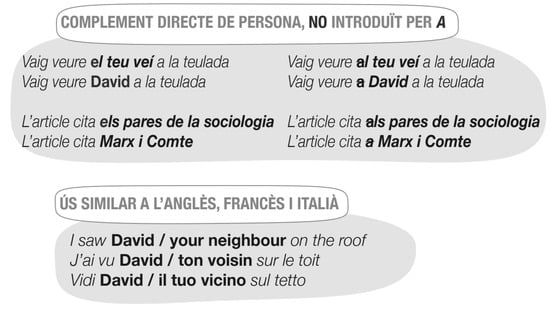

Gramàtica Zero (Esteve 2016), published by the University of Valencia, includes a section on DOM in Valencian, as illustrated in Figure 1. The grammar book states that the direct object referring to a person does not include the fake preposition “a”. On the left side, Figure 1 presents grammatically correct sentences according to the AVL’s guidelines (e.g., Vaig veure el teu veí en la teulada ‘I saw your neighbor on the roof’), and on the right, it shows incorrect sentences with the fake preposition “a” crossed out (e.g., Vaig veure al teu veí en la teulada ‘I saw your neighbor on the roof’).

Figure 1.

Gramàtica Zero (p. 43).

Another example can be found in the book Gramàtica Pràctica del Valencià (Ferrer 2017), which states that the direct object does not take a preposition normally (p. 171). The book includes various exercises illustrating this rule. One exercise involves translating sentences from Spanish into Valencian. The sentences include direct objects that are human and definite (e.g., ayudar a los refugiados ‘help the refugees’ and identificar a los asistentes ‘identify the attendees’) that take the fake preposition “a” in Spanish, but according to AVL prescriptive norms, the fake preposition “a” must not be included in the Valencian translation. Another exercise includes Valencian sentences in which students must identify incorrect usage and correct the sentences. Once again, examples with supposedly incorrect direct objects that are human and definite appear because they include the fake preposition “a” (e.g., atendre als pacients ‘attend the patients’).

However, the AVL grammar also acknowledges that in specific contexts, the direct object may be introduced by the fake preposition “a”. For instance, this occurs before personal pronouns, in cases of ambiguity between the subject and the direct object, in instances of dislocation, and optionally, before some indefinite pronouns, with ambiguous interrogatives and relatives, and before proper names. Lastly, the fake preposition “a” can also be used in structures in which one of the constituents already appears preceded by the fake preposition “a”.

Textbooks also mirror this prescriptive AVL norm. Numerous studies underscore the significance of researching textbooks, given their crucial role in classrooms (Bradley 2020; Iranzo 2021; Michelson and Anderson 2022). Indeed, these textbooks frequently serve as a foundational framework in curriculum development, particularly for less experienced instructors (Michelson and Anderson 2022). For example, in the textbook De dalt a baix B1 (p. 81) (Several Authors 2017), there is an explicit reference to the direct object. En valencià, el completement directe generalment no està introduït per la preposició a. ‘In Valencian, the direct object generally is not introduced by the preposition “a”.’ The book indicates that students must say He vist els alumnes a la cafeteria ‘I have seen the students in the cafeteria’ instead of He vist als alumnes a la cafeteria. Note that in the second sentence, the fake preposition “a” is included (als alumnes) to mark the direct object. Two exercises accompany the grammatical explanation. In the first, sentences such as els segrestadors han alliberat… ‘the kidnappers have released…’ appear, with the goal of students writing direct objects such as ‘the hostages’ in Valencian without the fake preposition “a”. The second activity is a fill-in-the-blanks exercise in which students must insert, where needed, the fake preposition “a”. For instance, la venedora ha atès ____ la clienta ‘the saleswoman has attended ____ the customer.’ In this case, according to the current AVL norm, nothing should be included in that blank.

Another example can be found in the textbook Junta (p. 20) (Pellicer and Pastor 2014). The content about direct objects and the fake preposition “a” says the following: Com el mateix nom ja indica, el complement directe és un sintagma nominal que va directament unit al verb, sense la presència de cap preposició ‘As the name itself indicates, the direct object is a noun phrase directly linked to the verb, without the presence of any preposition’. The book includes three examples: Pura busca la llibreta ‘Pura is looking for the notebook’, Pura busca el gat ‘Pura is looking for the cat’, and Pura busca la mare ‘Pura is looking for the mother’. Note that in the last example, la mare ‘the mother’ is a direct object that is both human and definite and is not introduced by the fake preposition “a”. Additionally, the textbook mentions that despite the use of the preposition “a” in Spanish, in Valencian, as in most languages, it is not used.

The present study specifically focuses on two types of direct objects: (+ animacy, + definiteness) vs. (– animacy, + definiteness). To summarize the norm in Spanish and the two norms in Valencian, Table 1 compiles the information in both languages.

Table 1.

DOM in Spanish and Valencian grammar norms.

2.2. The Effects of Prescriptivism

Educational institutions are spaces where prescriptive practices are enforced (Chrisomalis 2015; Collins 2022; Hubers et al. 2020). Prescriptivism has been defined as “individual, institutional, and socially shared preferences for how language ought to be used and any attempts made to regulate the language of others” (Cushing and Snell 2023, p. 196). Typically, though not always, prescriptivism is associated with a top-down process in which powerful groups (such as language academies or educators) attempt to impose prescriptive norms from their positions of authority or influence on language users (Lukač and Heyd 2023). The concept of prescriptivism is linked to ideologies of linguistic standardization that stigmatize the linguistic practices of certain groups for not adhering to prescriptive guidelines (Rosa 2016).

While the standardization of a language in educational settings has been linked to positive outcomes fostering favorable attitudes toward the language (Vari and Tamburelli 2021), the outcomes may take a distinct turn when considering minority languages. The effects of standardization and prescriptivism can have detrimental consequences, exacerbating the already delicate situation they face. For instance, Manchec-German (2023), in his study on Breton in France, cautions against these risks:

The idea of “saving” an endangered minority “language” by normalizing its grammar and modernizing its lexicon with the hope that this will arm future generations of speakers to compete with the prestigious language of a powerful nation-state can be doomed to failure.(p. 405)

Manchec-German (2023) argues that the standardization process and the subsequent imposition of norms can replace the spoken varieties the community uses with a standard that may be foreign even to the speakers. In such cases, despite such efforts often being interpreted as a “revival”, it would be more accurate to label them as “language replacement” (Manchec-German 2023).

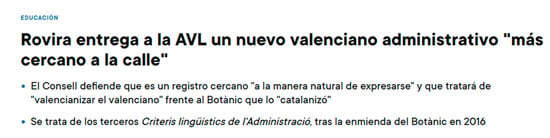

The case of the Valencian language may be similar to the abovementioned situation in which speakers sometimes question the norms taught in schools or used in official documents. A recurring criticism is directed at the Catalanization of the Valencian language by which Valencian forms are stigmatized or erased to converge toward Catalan forms. For example, Figure 2 is a news item published in a Valencian newspaper on 23 October 2023 (Sánchez 2023), indicating that the new right-wing government was set to use a Valencian language closer to the vernacular language. The news announces that the new government will “Valencianize” the language and claims that the previous government “Catalanized” the Valencian language.

Figure 2.

News item published in the Levante newspaper.

Despite efforts to impose the prescriptive norms of educators, language academies, and politicians, the debate on the effects of prescriptivism is far from settled. For example, Elspaß (2005) investigated the impact of prescriptivism on German. His research specifically focused on grammatical elements labeled incorrect in German for over a century. Elspaß (2005) categorized these elements into two distinct groups: those for which prescriptivism had achieved some measure of success and those whose influence remained minimal. The study presented three explanations for the persistence or disappearance of certain linguistic forms in German, despite historical disapproval. First, Elspaß (2005) highlighted the role of geographical distribution, noting that a nationwide presence of a linguistic form tended to diminish the sway of prescriptivism. Second, utility and functionality emerged as influential factors shaping language use, as certain linguistic forms persisted due to their effectiveness in communication. Finally, the study underscored the significance of stigmatizing linguistic features, revealing that prescriptivism had a more pronounced impact on elements considered vulgar or absurd.

Continuing the exploration of the impact of prescriptivism on language use, Hubers and De Hoop (2013) revealed the effects of prescriptivism on Dutch speakers. Prescriptive grammar rules in Dutch dictate the use of the complementizer dan ‘than’ in inequality comparatives. However, an alternative form, als ‘as’, has been used since the sixteenth century. Examining the Spoken Dutch Corpus, the authors observed that dan is generally more prevalent than als in comparative inequality constructions. Moreover, the choice between als and dan is influenced by the level of education. The study concludes that the observed educational effect underscores the strong influence of the prescriptive rules taught in schools, discouraging the use of als in inequality comparisons.

Despite the observed educational effects of prescriptivism, it is essential to consider the potential pitfalls associated with the application of prescriptive norms. Hubers et al. (2020) caution against the risk of hypercorrection, defined as “the overuse of prestigious forms in constructions in which they did not originally occur, and in fact should not occur according to prescriptive rules” (p. 552). As an illustration, Hubers et al. (2020) provided instances of replacing “me” with “I” in situations where “me” would be grammatically correct according to prescriptive norms (e.g., “It is difficult for my wife and me to find time” instead of “It is difficult for my wife and I to find time”). In their study, Hubers et al. (2020) investigated the use of the comparative particle dan and the accusative pronoun hen in Dutch among students at three different levels of high schools. Their findings indicated that instructing high school students in prescriptive grammar rules seems to improve their knowledge of these rules in specific constructions; however, the enhancement can be accompanied by an increase in hypercorrection in other instances.

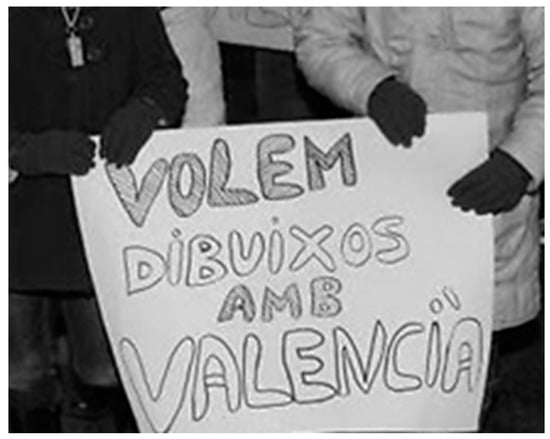

In Valencian, prescriptive norms can also cause hypercorrection among speakers or lead to uncertainty in using official norms. For instance, the prepositions en and amb can be a source of confusion for speakers of Valencian. While the preposition en in Valencian is commonly used as a translation of the English preposition “with” (e.g., Parle en ells ‘I speak with them’), it can also be equivalent to the English preposition “in” (e.g., Volem vore dibuixos en anglès ‘We want to watch cartoons in English’). Valencian students are taught in school that the preposition en is incorrect when it means “with” and should be replaced by amb (i.e., parle amb ells should be used instead of parle en ells). This norm that goes against the linguistic practices of the speakers creates a problem since they must change en to amb but only in specific contexts. As a result, hypercorrection sometimes occurs, changing en to amb even in contexts where the use of en is correct, as seen in Figure 3. Figure 3 (extracted from the blog “Societat Lingüística (2013)”) shows a sign that reads Volem dibuixos amb valencià ‘We want cartoons with Valencian, ‘rather than Volem dibuixos en valencià ‘We want cartoons in Valencian.’

Figure 3.

A sign in Valencian that shows an example of hypercorrection (https://societatlinguistica.blogspot.com/2013/12/en-i-amb-confusio-i-hipercorreccio.html, accessed on 27 January 2024).

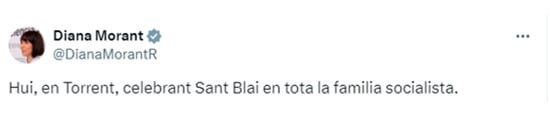

Avoidance of using this prescriptive norm can also be observed among Valencian speakers with extensive formal education. For example, Diana Morant, a Valencian citizen who serves as the Minister of Science and Innovation for the Spanish Socialist Party, sometimes tweets in Valencian. In February 2024, she tweeted (Figure 4) Hui, en Torrent, celebrant Sant Blai en tota la familia socialista (‘Today, in Torrent, celebrating Sant Blai with all the socialist family’). According to the official grammar of Valencian (AVL), the tweet should have read amb tota la familia socialista.

Figure 4.

A Tweet written by Diana Morant (Morant 2024). (https://twitter.com/DianaMorantR/status/1753749189014536557, accessed on 15 February 2024).

2.3. Linguistic Differentiation

The strategic use of language for political purposes has been a recurring phenomenon throughout history. One manifestation of this phenomenon is the creation of linguistic rules that artificially distinguish a language from others (van Splunder 2020). Such linguistic manipulation can manifest at various levels, including spelling, grammar, and vocabulary (Stojanov 2023; Tyran 2023; van Splunder 2020).

For instance, in Turkey, Atatürk’s nationalist program aimed at the westernization of the Turkish language. Arabic and Persian terms were erased as part of this initiative, making way for more Western terms, mainly from French (van Splunder 2020). Additionally, the alphabet transitioned from Arabic to Latin script (van Splunder 2020). Another example of ideological linguistic manipulation can be observed in the former Yugoslavia. Several studies have explored efforts to create differentiation among linguistic varieties (Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian) spoken in the region (Jovanović 2018; Kapović 2011; Kordić 2008). In Montenegrin, the first spelling manual introduced changes in orthography to widen the difference between Montenegrin and the other linguistic varieties (Stojanov 2023; van Splunder 2020). In Bosnian, differentiation is sought by increasing the use of terms of Turkish or Arabic origin (Jovanović 2017; Tyran 2023). Similarly, language policies in Croatia have aimed to eliminate Serbian influences, and debates focusing on spelling changes to increase differences between Serbian and Croatian are common (Jovanović 2017; Kapović 2011; Stojanov 2023). Norway also underwent a deliberate process of linguistic differentiation. Currently, Bokmål, which is based on Danish norms, stands as the dominant standard. In contrast, Nynorsk, utilized by approximately 15% of the population, was developed by linguists after Norway gained independence in the late nineteenth century (Strand 2019). Strand (2019) affirmed the following:

Nynork (previously called Landsmål ‘language of the country’) ought to include Norwegian linguistic forms and features that were furthest from, or least influenced by, Danish or Swedish. The Nynorsk written norm thus emphasizes grammatical and lexical forms that were widespread in the “conservative” spoken dialects of Western and Midland Norway in the mid- to late nineteenth century, believed to be closest to Old Norwegian.(p. 53)

In some instances, there is an attempt to exaggerate a particular characteristic of a linguistic variety, but in more radical instances, linguistic manipulation goes further. Politicians and institutions attempt to create grammatical rules or vocabulary that directly contradict the linguistic practices of the speakers, aiming to fabricate artificial differences. Kordić (2008), quoting Anić (2000) in an interview, encapsulates this phenomenon as follows:

Da noi esiste una versione semiidiotizzata, artificiale della lingua, creata in qualche studio di professori. Lì, uomini dotti inventano regole proprie, totalmente contrarie a quanto è stato detto intorno alle varie questioni linguistiche. Viene imposta una lingua del tutto falsa.

In our case, there exists a semi-idiotized, artificial version of the language created in some professor’s office. There, scholars invent their own rules, totally contrary to what has been said about various linguistic issues. A completely false language is imposed.

However, the effectiveness of these language policies in imposing change exhibits considerable variation. Despite some successful scenarios, institutional initiatives to alter speakers’ language often encounter challenges and may not consistently achieve their goals (Kapović 2011; van Splunder 2020).

3. The Study

3.1. Research Questions

This study examined the use of DOM in Valencian by bilingual speakers of Spanish and Valencian. According to the norm of the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua (AVL), Valencian does not use marking for definite human direct objects. However, this norm does not match the norm of the Real Acadèmia de Cultura Valenciana (RACV). Therefore, one of these norms must go against the linguistic practices of Valencian speakers (unless there is free variation among the speakers). Specifically, the study focuses on two research questions:

- (a)

- Is Valencian a DOM language that marks specific human direct objects with the fake preposition “a”?

Contrary to the assertions of official prescriptive grammars and textbooks, it was hypothesized that Valencian is a language that marks human and definite direct objects with the fake preposition “a”, as demonstrated in videos from the Museu de la Paraula. The insistence with which textbooks and prescriptive grammars affirm that the fake preposition “a” does not exist or is incorrect may indeed indicate its actual use.

- (b)

- What social factors explain the use of DOM in Valencian?

Despite the primary focus of the study on analyzing education’s role in the production of the fake preposition “a” to mark human and definite direct objects, demographic variables such as age and sex were also included. This inclusion aligns with the common approach in sociolinguistic studies (Regan 2020; Santana Marrero 2016; Tieperman and Regan 2023). Labov (1990) suggested that men tend to conform less to prescription in linguistic change from above. In this study, it was hypothesized that women would adhere more closely to the prescriptive grammar advocated by the AVL. In addition, previous studies in Spain have indicated a correlation between age and education. Generally, older generations exhibit lower levels of educational attainment (Regan 2020). This trend is particularly pronounced in Valencia, where participants from older generations studied in an educational system that did not include instruction in the Valencian language. It was hypothesized that participants with more formal education and younger in age would adhere more closely to the prescriptive norm.

3.2. Data Collection and Methods

3.2.1. Participants

A total of 37 participants (24 females), divided into two groups, took part in this study. One group consisted of Valencian–Spanish bilingual speakers without formal instruction in Valencian (n = 15), and the other group comprised Valencian–Spanish bilingual speakers with formal instruction in Valencian (n = 22). The study was conducted in the town of Puçol. Figure 5 shows the location of Puçol near the city of Valencia.

Figure 5.

Location of Puçol in Valencia.

The group without formal instruction (M age = 70.33; SD = 7.19) comprised 15 participants (8 females). All of them acquired Valencian from birth (age of onset of acquisition = 0) and Spanish during childhood, but not necessarily from birth (age of onset of acquisition = 0.94). These participants never received formal instruction in school, as they attended school before Valencian was introduced into the Valencian educational system through Act 4/1983 (llei d’ús i ensenyament del valencià) (Lledó 2011).

The group with formal instruction (M age = 34.86; SD = 10.38) included 22 participants (16 females). All of them learned Valencian from birth (age of onset of acquisition = 0) and Spanish during childhood, but not necessarily from birth (age of onset of acquisition: M = 0.65). These participants received formal instruction in Valencian in school (average years of education in Valencian: M = 10.64, SD = 2.43). Table 2 provides biographical information for both groups.

Table 2.

Biographical information.

3.2.2. Instruments

This study is part of a larger research project on the Valencian language in which the effects of prescriptivism at the morphosyntactic and lexical levels are explored. In this section, only the instruments relevant to this study will be described. The study began with an explanation of the project and obtaining signed consent forms. Subsequently, a production task was conducted, and finally, biographical information (age, sex, age of acquisition of Spanish and Valencian, and years of instruction in Valencian) was collected using a form in Qualtrics. In addition, since we were interested in participants who usually speak Valencian, the question below was included in Qualtrics, and only those participants who chose the first option were included.

Which option best defines you?

- (a)

- I have spoken Valencian since birth, and I speak it with my friends and family. I consider Valencian to be my native language (although I can speak Spanish).

- (b)

- I usually do not speak Valencian with my friends and family. Valencian is a language I learned at school. I usually speak Spanish with my family and friends. I consider Spanish to be my native language (although I can speak Valencian).

- (c)

- Neither of the above.

To examine the use of the DOM in Valencian, an oral production task was applied (Montrul and Sánchez-Walker 2013). The oral modality was chosen because older participants had never received formal instruction in Valencian. A PowerPoint presentation was used in which each slide displayed the subject, the infinitive verb, and the direct object (article + noun). The task comprised 21 slides, eight of which specifically examined the property under study. Four slides had a masculine singular direct object, and four had a feminine singular direct object. Figure 6 shows an example in which the subject, the infinitive verb, and the direct object are included. Four verbs were used: abraçar ‘to hug’, colpejar ‘to hit’, visitar ‘to visit’, and tocar ‘to touch’. Each verb appeared with a human definite direct object (el bebé ‘the baby’) or a non-human definite direct object (la planta ‘the plant’). Before starting the test, participants had the opportunity to practice and ask questions to the researcher. The participants’ productions were recorded and transcribed for later analysis.

Figure 6.

Example of the oral production task.

Participants received EUR 20 for their participation upon completing the study, and the entire duration of the study did not exceed one hour.

4. Results

First, the dependent and independent variables in this study must be defined. The dependent variable is the use of the fake preposition “a”, while the independent variables consist of three demographic factors: education, age, and sex. Education was categorized into two levels: with and without education. Age was categorized into three levels: older adults (65 or above), adults (35–64), and young adults (18–34), and the sex variable was divided into males and females.

Overall, the mean production of the fake preposition “a” to mark definite and human objects was 85.14% (SD = 21.62), and the 95% confidence interval was 77.93–92.34%. Table 3 shows the mean proportion and standard deviation of the use of the fake preposition “a” in both education groups with definite human and non-human direct objects. Both groups exhibited a high percentage of use of the fake preposition “a” to mark human and definite direct objects in Valencian. In the case of the group without instruction in Valencian, usage reached 90%, while in the group with instruction, it reached 81%. The use of the fake preposition “a” was reduced, as expected, when the direct object was non-human and definite. In the case of the group without instruction in Valencian, it reached 3.33%, while in the educated group, it reached 4.54%. It is worth noting that, according to the grammar of the AVL, which is currently official, the column “a for human” should be 0 because the direct object should not be marked with “a” if it is human and definite.

Table 3.

Results of production task by education.

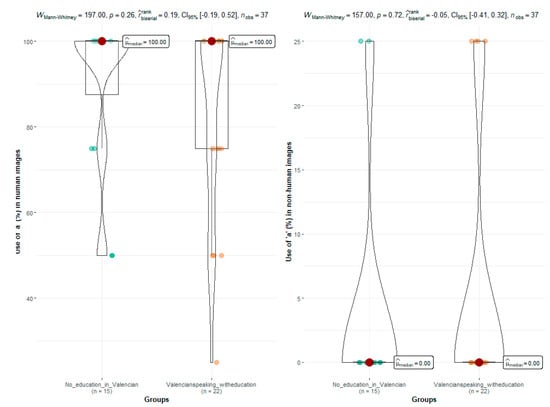

The comparative statistical analysis of our results is illustrated in Figure 7. Two violin plots show data density, focusing on the usage of the fake preposition “a” with human and non-human direct objects. The plots display median values and the outcomes of statistical comparison tests for the variable “group”, which categorizes individuals based on their educational background. The results of the Mann–Whitney test reveal that the difference between the two groups is not statistically significant for human direct objects ([U = 197.00, p = 0.26] and for non-human direct objects [U = 157, p = 0.72]). These results suggest the absence of an association between the grouping variable and the dependent variable (the use of the fake preposition “a”).

Figure 7.

Production of DOM by education group.

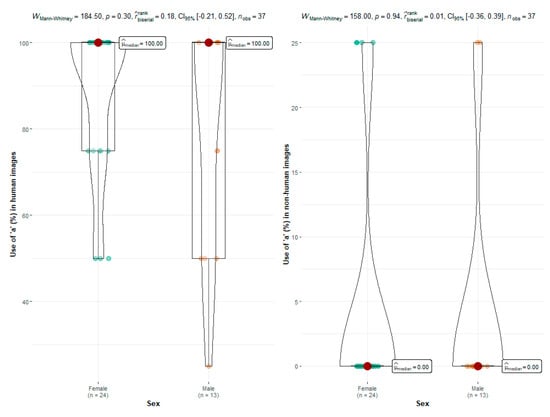

Table 4 displays the proportion of the use of the fake preposition “a” by sex. Use of the fake preposition “a” for human direct objects reached 88.54% in men compared to 78.85% in women. Regarding non-human direct objects, the use of the fake preposition “a” was 3.84% in men compared to 4.17% in females.

Table 4.

Results of production task by sex.

The comparative statistical analysis of our results is illustrated in Figure 8. The plots display median values and the outcomes of statistical comparison tests for the variable “group”, which categorizes individuals based on sex. The results of the Mann–Whitney test reveal that the difference between the two groups is not statistically significant for human direct objects ([U = 184.50, p = 0.30] and for non-human direct objects [U = 158, p = 0.94]). These results suggest the absence of an association between the grouping variable and the dependent variable.

Figure 8.

Production of DOM by sex.

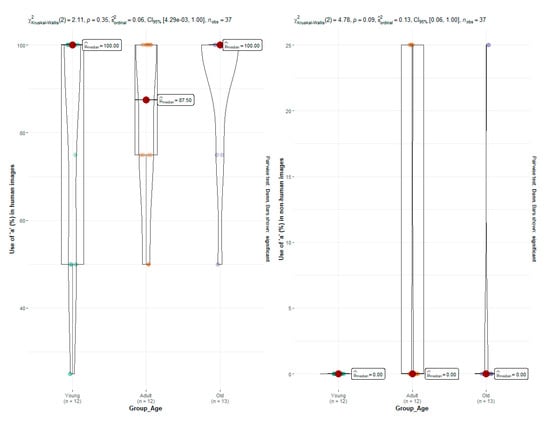

Table 5 displays the prevalence of the use of the fake preposition “a” by age group. The utilization of the fake preposition “a” reached 92.31% in the old group, 83.33% in the adult group, and 79.1% in the young group. Regarding non-human direct objects, the use of the fake preposition “a” reached 3.87% in the older adult group, 8.33% in the adult group, and 0 in the young adult group.

Table 5.

Results of production task by age.

Figure 9 displays the violin plots illustrating the relationship between the use of the “a personal” and sex. 6. In this case, the Kruskal–Wallis test will be used, which is the non-parametric equivalent of the ANOVA test, since we have three groups to compare. The Kruskal–Wallis test (Chi square = 2.1, p = 0.35) reveals that there is no statistically significant difference between the groups, suggesting that there is no association between the grouping variable and the dependent variable.

Figure 9.

Production of DOM by age group.

Next, a beta regression analysis (Table 6 and Table 7) will be chosen because the dependent variable is a percentage with values between 0 and 100. Three models will be employed: the first will include only the number of years studied in Valencian, the second will incorporate sex and age as control variables, and the third will add the interaction between years of education and age. This addition aims to assess whether these two variables have a significant influence, given their high correlation (r = –0.85).

Table 6.

Results of the multiple beta regression with “a” in non-human.

Table 7.

Results of the multiple beta regression with “a” in humans.

As shown in the tables above, none of the variables was significant. However, it should be noted that the model shows a slight improvement in R-squared when the interaction term is included. This suggests that exploring the interaction between age and years of study in Valencian could be an interesting avenue for further investigation despite the lack of significance in this study.

5. Discussion

Two primary objectives drove this study: First, to explore the DOM in the Valencian language, specifically the use of the fake preposition “a” to mark human and definite direct objects. Second, the study aimed to investigate what social factors help explain the use of the fake preposition “a” to mark direct objects. This study, conducted in Puçol (Valencia), included Spanish–Valencian bilingual speakers. The participants completed a picture description task to elicit the use of “a” in direct objects (e.g., el bebé ‘the baby’; la planta ‘the plant). The key findings are discussed below.

In assessing whether Valencian is a DOM language, our goal was to study the usage of the fake preposition “a” among Valencian speakers. According to official prescriptive grammars and textbooks, Valencian is a language that typically does not mark direct objects with the fake preposition “a”. Therefore, to demonstrate that Valencian is a DOM language, we operated under the assumption that the mean proportion of “a” usage should not be zero. Otherwise, we would consider that Valencian is not a DOM language.

The overall results revealed a mean production of the fake preposition “a” at 85.14%, with a 95% confidence interval of 77.93% and 92.34%. As this interval excludes zero, we assert that at a significance level of 0.05, the proportion of usage of the fake preposition “a” to mark direct objects (definite and human) is significantly different from zero. It is noteworthy that according to the AVL norm, this value is expected to be zero. According to that norm, the Valencian language should exhibit behavior similar to other languages, such as English, in sentences involving human and definite direct objects. Our findings suggest that Valencian should be categorized among DOM languages (Aissen 2003). Moreover, these findings question the established norm of the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua, pointing to a more descriptive orientation of the non-official Real Acadèmia de Cultura Valenciana norm. This indicates that a rule being normative does not necessarily mean it is more suitable for the speakers or more descriptive, but rather a matter of power or hegemony (Curzan 2014).

These results also indicate an attempted imposition of linguistic differentiation, similar to observations in other languages (Stojanov 2023; Tyran 2023; van Splunder 2020). Nevertheless, the efficacy of these imposed linguistic differentiations faces obstacles and may not always attain their goal successfully (Kapović 2011). While such changes are common in language varieties such as Serbian or Croatian, when these efforts aim to justify their classification as distinct languages, as in the case of Valencian, such categorization is deemed unnecessary. The era when Spanish was considered a language and other Spanish linguistic varieties like Valencian were labeled “dialects” is outdated. Spanish and Valencian are now widely regarded as independent languages in Spain. Imposing linguistic changes contrary to speakers’ practices may generate mistrust in Valencian usage, potentially affecting the respect for this minority language and the willingness to use it and transmit it to future generations.

The second research question focused on social factors that may explain the usage of the fake preposition “a”. According to the normative of the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua, taught in Valencian schools, a direct object is not introduced by the fake preposition “a” in the cases analyzed in this study. Despite the group with formal education using the fake preposition “a” slightly less than their counterparts (90% vs. 81.82%), the difference was not statistically significant. Additionally, no significant differences were found among sex and age variables. There are several reasons why we consider that the initial hypotheses were not fulfilled. The use of “a” may be prevalent across the entire Valencian Community, and its usage might not be stigmatized, reducing the impact of prescriptivism. This possibility aligns with previous observations about limitations in prescriptive actions (Elspaß 2005). The results of this study contradict those indicating the effects of prescriptivism in groups with formal instruction (Hubers and De Hoop 2013). The difference in the impact of prescriptivism observed between Hubers and De Hoop’s study and the current research could also stem from differences in teaching practices. Perhaps the emphasis and insistence on teaching the norms of DOM in Valencian, as per the AVL grammar, differ from how comparatives are taught in the Netherlands. Future research could benefit from examining the frequency with which prescriptive norms are taught throughout K–12 education to estimate the potential effects of prescriptivism.

Finally, this study paves the way for further research on Valencian’s DOM and other linguistic properties, as well as the effects of prescriptivism in minority languages. However, there are some limitations and avenues for future research that must be mentioned. First, there was a confounding between age and education variables, as older participants did not have access to education in Valencian. Second, both the samples from the Museu de la Paraula corpus and the participants in this study were from the province of Valencia, but the Valencian Community also includes the areas of Castellon and Alicante. Future studies could benefit from extending the investigation of DOM in Valencian to these areas. Third, future studies may focus on differences in the use of DOM in different verbs. Finally, a larger number of participants, as well as a balance between male and female participants, would have been beneficial.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of HelsinkIRB-AY20-21-217.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restriction.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge that we have used the Microsoft Word spell check and Grammarly while writing this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aissen, Judith. 2003. Differential object marking: Iconicity vs. Economy. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 21: 435–83. [Google Scholar]

- Anić, Vladimir. 2000. Gavorite li idiotski? Feral Tribune. [Google Scholar]

- Arechabaleta Regulez, Begoña, and Silvina Montrul. 2021. Psycholinguistic Evidence for Incipient Language Change in Mexican Spanish: The Extension of Differential Object Marking. Languages 6: 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arechabaleta Regulez, Begoña, and Silvina Montrul. 2023. Production, acceptability, and online comprehension of Spanish differential object marking by heritage speakers and L2 learners. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1106613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlandis, Bernat, Marta Lanuza, Miquel Àngel Lledó, and Òscar Rueda. 2015. Nova Gramàtica de la Llengua Valenciana. Valencia: Real Acadèmia de Cultura Valenciana. [Google Scholar]

- AVL. 2006. Gramàtica Normativa Valenciana. Valencia: Publicacions de l’Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista Maldonado, Salvador, and Silvina Montrul. 2019. An experimental investigation of differential object marking in Mexican Spanish. Spanish in Context 16: 22–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossong, Georg. 1991. Differential object marking in romance and beyond. In New Analyses in Romance Linguistics. Edited by Douglas Kibbee and Dieter Wanner. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 143–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, Melissa, and Silvina Montrul. 2009. Instructed L2 acquisition of differential object marking in Spanish. In Little Words. Their History, Phonology, Syntax, Semantics, Pragmatics, and Acquisition. Edited by Ronald Leow, Héctor Campos and Donna Lardiere. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 199–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Andrew. 2020. Linguistic Authority and Authoritative Texts: Comparing Student Perspectives of the Politics of Language and Identity in Catalonia and the Valencian Community. Doctoral thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Chrisomalis, Stephen. 2015. What’s so improper about fractions? Prescriptivism and language socialization at Math. Language in Society 44: 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Peter. 2022. Hypercorrection in English: An intervarietal corpus-based study. English Language and Linguistics 26: 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curzan, Anne. 2014. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, Ian, and Julia Snell. 2023. Prescriptivism in education: From language ideologies to listening practices. In The Routledge Handbook of Linguistic Prescriptivism. Routledge Handbooks in Linguistics. Edited by Joan Beal, Morana Lukač and Robin Straaijer. London: Routledge, pp. 194–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cuza, Alejandro, Lauren Miller, Rocio Pérez Tattam, and Maroliz Ortiz Vergara. 2019. Structure complexity effects in child heritage Spanish: The case of the Spanish personal a. International Journal of Bilingualism 23: 1333–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Justin. 2022. On Catalan as a minority language: The case of Catalan laterals in Barcelonan Spanish. Journal of Sociolinguistics 26: 362–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente Iglesias, Mónica, and Susana Pérez Castillejo. 2022. L1 phonetic permeability and phonetic path towards a potential merger: The case of Galician mid vowels in bilingual production. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 12: 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diputació de Valencia. n.d. Museu de la Paraula. Available online: www.musedelaparaula.es (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Elspaß, Stephan. 2005. Language norm and language reality. Effectiveness and limits of prescriptivism in New High German. In Linguistic Purism in the Germanic Languages. Edited by Nils Langer and Winifred Davies. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 20–45. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve, Francesc. 2016. Gramàtica Zero, 2nd ed. Valencia: Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, Montse. 2017. Gramàtica pràctica del valencià. Alzira: Tàndem. [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro-Fuentes, Pedro, and Theodoros Marinis. 2007. Acquiring phenomena at the syntax/semantics interface in L2 Spanish: The personal preposition a. Eurosla Yearbook 7: 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubers, Ferdy, and Helen De Hoop. 2013. The effect of prescriptivism on comparative markers in spoken Dutch. Linguistics in the Netherlands 30: 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hubers, Ferdy, Thijs Trompenaars, Sebastian Collin, Kees De Schepper, and Helen De Hoop. 2020. Hypercorrection as a By-product of Education. Applied Linguistics 41: 552–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Esther. 2020. Verbal lexical frequency and DOM in heritage speakers of Spanish. In The Acquisition of Differential Object Marketing. Edited by Silvina Montrul and Alexandru Mardale. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 207–36. [Google Scholar]

- Iranzo, Vicente. 2021. Where’s the llengua valenciana? A Study of Language Ideologies in Textbooks in Spain. Cahiers Internationaux de Sociolinguisticque 19: 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Irimia, Monica, and Alexandru Mardale. 2023. Differential Object Marking in Romance: Towards Microvariation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Jegerski, Jill, and Irina Sekerina. 2020. The processing of input with differential object marking by heritage Spanish speakers. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23: 274–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, Srdan. 2017. The misuse of language. Serbo-croatian, “czechoslovakian” and breakup states. East European Quaterly 45: 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanović, Srdan. 2018. Assertive discourse and folk linguistics: Serbian nationalist discourse about the cyrillic script in the 21st century. Language Policy 17: 611–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapović, Mate. 2011. Language, Ideology and Politics in Croatia. Slavia Centralis 4: 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kordić, Snježana. 2008. Purismo e censura linguistica in Croazia oggi. Studi Slavistici 5: 281–97. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William. 1990. The intersection of sex and social class in the course of linguistic change. Language Variation and Change 2: 205–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lledó, Miquel Àngel. 2011. The Independent Standardization of Valencian: From Official Use to Underground. In Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts. Edited by Joshua Fishman and Ofelia García. Oxford: OUP, vol. 2, pp. 336–48. [Google Scholar]

- López Otero, Julio César. 2020. On the acceptability of the Spanish DOM among Romanian-Spanish bilinguals. In The Acquisition of Diferential Object Marking. Edited by Silvia Montrul and Alexandru Mardale. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 161–81. [Google Scholar]

- López Otero, Julio César. 2022. Bidirectional cross-linguistic influence on DOM in Romanian-Spanish bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingualism 26: 710–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Otero, Julio César, and Abril Jimenez. 2022. Productive Vocabulary Knowledge Predicts Acquisition of Spanish DOM in Brazilian Portuguese-Speaking Learners. Languages 7: 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukač, Morana, and Theresa Heyd. 2023. Grassroots prescriptivism. In The Routledge Handbook of Prescriptivism. Edited by Joan Beal, Morana Lukač and Robin Straaijer. London: Routledge, pp. 227–45. [Google Scholar]

- Manchec-German, Gary. 2023. Standardization, prescriptivism and diglossia. In The Routledge Handbook of Linguistic Prescriptivism. Edited by Joan Beal, Morana Lukač and Robin Straaijer. London: Routledge, pp. 405–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mardale, Alexandru, and Petros Karatsareas. 2020. Differential Object Marking and Language Contact: An Introduction to this Special Issue. Journal of Language Contact 13: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, Kristen, and Ashley Anderson. 2022. Ideological views of reading in contemporary commercial French textbooks: A content analysis. Second Language Research & Practice 3: 34–61. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Noelia Sánchez-Walker. 2013. Differential Object Marking in Child and Adult Spanish Heritage Speakers. Language Acquisition 20: 109–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, Rakesh Bhatt, and Roxana Girju. 2015. Differential Object Marking in Spanish, Hindi and Romanian as heritage languages. Language 91: 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morant, Diana. 2024. [@DianaMorantR]. Hui, en Torrent, Celebrant Sant Blai en tota la Familia Socialista. [Images Attached] [Post]. X. February 3. Available online: https://twitter.com/DianaMorantR/status/1753749189014536557 (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Pellicer, Joan, and Sofia Pastor. 2014. Junta. Olbia: En Logística. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, Brendan. 2020. The split of a fricative merger due to dialect contact and societal changes: A sociophonetic study on Andalusian Spanish read-speech. Language Variation and Change 32: 159–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Mondoñedo, Miguel. 2008. The Acquisition of Differential Object Marking in Spanish. Probus 20: 111–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, Jonathan. 2016. Standardization, racialization, languagelessness: Raciolinguistic ideologies across communicative contexts. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 26: 162–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana Marrero, Juana. 2016. Seseo, ceceo y distinción en el sociolecto alto de la ciudad de Sevilla: Nuevos datos a partir de los materiales de PRESEEA. Boletín de Filología de La Universidad de Chile 51: 255–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Gonzalo. 2023. Rovira Entrega a la AVL un Nuevo Valenciano Administrativo “más Cercano a la Calle”. Levante. October 23. Available online: https://www.levante-emv.com/comunitat-valenciana/2023/10/23/rovira-avl-sellan-nuevo-valenciano-93684503.html (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Several Authors. 2017. De Dalt a Baix B1. Valencia: Bromera. [Google Scholar]

- Societat Lingüística. 2013. ‘En’ i ’amb’: Confusió i Hipercorrecció, April 18. Available online: https://societatlinguistica.blogspot.com/2013/12/en-i-amb-confusio-i-hipercorreccio.html (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Stojanov, Tomislav. 2023. Understanding spelling conflicts in Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian: Insights from speakers’ attitudes and beliefs. Lingua 296: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, Thea R. 2019. Tradition as innovation: Dialect revalorization and maximal orthographic distinction in rural Norwegian writing. Multilingua 38: 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thane, Patrick D. 2024. On the Acquisition of Differential Object Marking in Child Heritage Spanish: Bilingual Education, Exposure, and Age Effects (In Memory of Phoebe Search). Languages 9: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieperman, Robin, and Brendan Regan. 2023. A variationist corpus analysis of the definite article with personal names across three varieties of Spanish (Chilean, Mexican, Andalusian). Isogloss. Open Journal of Romance Linguistics 9: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyran, Katharina. 2023. Indicating ideology: Variation in Montenegrin orthography. Language & Communication 88: 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- van Splunder, Frank. 2020. Language is Politics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vari, Judit, and Marco Tamburelli. 2021. Accepting a “New” Standard Variety: Comparing Explicit Attitudes in Luxembourg and Belgium. Languages 6: 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Heusinger, Klaus, and Georg Kaiser. 2007. Differential object marking and the lexical semantics of verbs in Spanish. In Proceedings of the Workshop “Definiteness, Specificity and Animacy in Ibero-Romance Languages”. Edited by Georg Kaiser and Manuel Leonetti. Arbeitspapier 122. Konstanz: Universität Konstanz, Fachbereich Sprachwissenschaft, pp. 83–109. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).