Abstract

This qualitative case study reports the impact of schooling on migrant children’s language socialization, particularly focusing on the role of language ideologies and practices within Korean schools. Despite an increasing population of migrant multilingual children in Korean schools, the education system predominantly follows a monolingual orientation with Korean as the primary medium of instruction. The research aims to address this gap by investigating the influence of Korean teachers’ and emergent multilingual youths’ language ideologies on bi- and multilingual language education. Additionally, this study explores how emerging multilingual children comply with or exhibit ambivalence/resistance toward instructed practices. Data were collected over three years from a regional middle school in South Korea and inductively analyzed using constant comparative methods. The findings underscore the significance of creating a multilingual space in classrooms where teachers value diverse linguistic and other semiotic resources, fostering more active engagement and negotiation of meaning among multilingual students. In contrast, monolingual-oriented classrooms result in the students’ passive behavior and hinder socialization into the Korean school environment. This study advocates for a more inclusive learning environment that recognizes and embraces multilingual values, facilitating meaningful language practices among emerging multilingual youth.

1. Introduction

Language socialization (LS) can be defined as an interactive process in which “members constantly conform and inform one another through language” (McDermott et al. 1978, as cited in Schieffelin and Ochs 1986, p. 165). Especially, LS research in multilingual educational settings and communities expands our understanding of children’s language acquisition, shift, and maintenance, as well as their socialization processes, as evidenced in their everyday experiences within and across small-scale communities, such as schools, families, and peer groups (Moore 1999). By exploring individuals’ socialization through languages and use of languages, LS is primarily concerned with one’s social and linguistic development as a lifetime work and views educational institutes as “integrated sites for socialization within society rather than as self-constrained autonomous settings” (Mangual Figueroa and Baquedano-López 2017, p. 142). This underscores the role of schooling in the socialization process and implies that schools and other educational institutes can become valuable and critical places particularly for (im)migrant children to successfully socialize into a new given context. With the emerging interest in (im)migrant children’s language socialization, recent LS studies have explored (im)migrant youth’s schooling experiences as they encounter new social contexts while simultaneously processing language and cultural contact from and within their home and host countries. These studies have brought to light the opportunities and challenges that emerge when diverse linguistic and cultural values meet in school (Baquedano-López and Mangual Figueroa 2011; Mangual Figueroa and Baquedano-López 2017). They have also demonstrated how school is the first and critical place where the cultural and linguistic collision occurs upon new (im)migrant groups’ arrival in a host community. Here, language ideological changes at the macro level and language practices at the micro level are also closely interconnected as school community members interact to transform classroom environments (Baquedano-López and Kattan 2008). In order to understand such socially embedded phenomena, it is necessary to take a close look at school performances from language socialization perspectives and from an ecological view, to some extent.

The conventional perception of South Korea has been predominantly monolingual and monocultural, as documented by early scholars (e.g., Spolsky 1972). However, the forces of globalization and a notable surge in migration to South Korea have engendered a shifting sociodemographic landscape not only in schools but also in Korean society at large (Fedorova and Nam 2023; Korean Ministry of Justice 2022). Notably, among the migrants, the number of Russian-speaking migrants reflects a substantial presence as one of the top five foreign-origin resident groups in Korea, hailing from various regions, including Russia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan (Korean Ministry of Justice 2022), and they are the focal participants in this article.

This migrant population is notable for its distinctive linguistic and cultural characteristics. They identify Russian as their primary language, and within their migrant community in South Korea, Russian serves as their dominant mode of communication, emphasizing the significance of acquiring and utilizing the Russian language, particularly for their offspring (Kim 2018). Moreover, it is reported that they tend to devalue learning and using Korean in their households and communities, which negatively impacts the development of young Russian-speaking migrants’ Korean language proficiency and their academic success in Korean schools (Kim 2018). Their primary reliance on Russian, coupled with a limited engagement in learning Korean, stands out, particularly when compared to migrants from other countries such as China, Japan, and Vietnam, who tend to place a higher value on using Korean in South Korea (Lee and Park 2020).

Despite the existing literature suggesting a devaluation of Korean language use and learning among Russian-speaking migrants, it is noteworthy that their communicative practices encompass a rich array of linguistic and other semiotic resources (English, Korean, and Russian, and emojis), which are frequently observed in various communal settings, including school, migrant centers, and churches (Jang 2021, 2023). Specifically, in communicating with Korean-English bilinguals (e.g., Korean-English teachers), newly migrated Russian-speaking students make use of their full linguistic repertoires to better communicate with them.

However, within the South Korean context, there is a noticeable absence of scholarly exploration regarding how multilingual values and beliefs serve as active and pivotal domains for legitimizing emerging multilingual migrant youth’s language and literacy practices, amplifying their voices and nurturing their social connections through communicative practices in their host country, particularly in school settings. Equally underexplored is the discursive construction of the young migrants’ language values and beliefs, as well as their school language socialization in institutional settings.

LS research on (im)migrant youth in schools in different countries, such as Italy, Japan, Spain, and the USA (Byon 2003; di Lucca et al. 2008; García-Sánchez 2010; Schecter and Bayley 1997; Son 2017), provides some answers to the roles that language ideologies play as shapers in children’s language learning experiences—which consequently have an impact on language acquisition, shift, and maintenance—by illustrating how such ideologies are implemented in school language socialization practices. Research on teachers’ and students’ everyday language socialization practices also reveals how children’s language use is articulated by the local interpretation of linguistic and social reproduction and change (Howard 2008). In line with these ideas, while underscoring the importance of harmonious multilingual education for this migrant youth population, in this paper, I will demonstrate the role of schooling in (im)migrant children’s school language socialization processes and practices with respect to two guiding questions:

- How do Korean teachers’ and emergent multilingual youths’ language ideologies (re)shape bi- and multilingual language education in school?

- How do the emerging multilingual children comply with or show ambivalence/resistance toward the practices they are instructed in?

Through the exploration of these questions, this study aims to (1) explore teachers’ and students’ language values and beliefs within school walls, (2) showcase unique insights from their language socialization practices by highlighting their perspectives and voices, and (3) expand the academic conversations for research on L2 education and school language socialization of school-aged migrant multilingual children.

1.1. Language Ideological Considerations within and across School Contexts

While language ideologies (a set of social/societal elements) are located at the macro level, schools and related communities are placed at the meso-level, illustrating social identities as a construct and as a part of socio-institutional relationships, within which roles are generalized through the interplay of agency, power, and investment (Douglas Fir Group 2016; Duff 2019). The whole point here is that ideologies are concurrently encountered, performed, discussed, resisted/compromised more at meso and micro levels while circulating within and beyond a macro level (Duff 2019). For instance, if educational policy both at the national and local levels favors dominant/national language-only educational institutions, this may be either welcomed or unwelcomed by individuals in a particular place and at a particular moment depending on the ideological constructs they inherit or create which, in turn, affect their language choice and learning. This implies that the more conflicts that result from the ideological gaps between individuals and national and/or local interpretations, the more the likelihood of first/second/foreign/additional language development for both dominant language speakers and minorities would decrease.

This influence becomes more evident by looking into di Lucca et al. (2008) and García-Sánchez (2010). These two studies show how Moroccan (im)migrant children dramatically shift or maintain their language(s) and shape and reshape their attitudes and practices in accordance with the contexts they are involved with. The study of di Lucca et al. (2008) reports on Moroccan migrant children’s language socialization both at home and in school in small towns in Northern Italy. Upon arrival, the children (aged between 9 and 13) used Moroccan Arabic as their home language. Their proficiency in Standard Arabic and French varied based on the number of years they had spent in Moroccan schools before migration while carrying almost no knowledge of Italian. Faced with the burden of learning Italian, the children (and their families) found themselves within a social context that was not quite ready to encompass their linguistic and cultural backgrounds.

Despite the fact that these particular families under study were the first Moroccan settlers in that region, throughout Italy a hostile nation-wide sentiment towards Moroccan migrants was already well in place at the time, as exemplified by the common reference to Moroccans as ‘Marocchino’, a derogatory term in Italian. This sentiment also had an impact on Italian schools and other educational institutions, which showed a strong orientation towards linguistic and cultural assimilation based on monolingualism.

The main goal of the schools was to have the migrant children acquire Italian to facilitate their content learning, as well as their in-class participation. For this purpose, the schools asked the children to attend classes one or two years lower than the ones appropriate for their ages and placed a high degree of pressure on them to achieve a level of Italian language proficiency comparable to native speakers of their ages. This kind of situation was a demotivating factor in the children’s language socialization.

Furthermore, most teachers also considered minority language(s) (e.g., Moroccan Arabic) to be an obstacle to learning Italian and did not see the children’s minority language(s) as valuable resources for enhancing their linguistic repertoires. Under such circumstances, Italian became the dominantly spoken language among the children, even when communicating with their Moroccan peers, while their native Moroccan Arabic was rarely used inside and outside of the school setting. Notably, none of the participants expressed any dissatisfaction toward the Italian school system in regard to their language education, and, in fact, they expressed full satisfaction with this de facto affirmation of the superiority of the Italian language over their heritage language(s).

On the other hand, the attitudes toward Moroccan immigrant communities in educational settings in Spain (García-Sánchez 2010) tended to be quite different from that in Italy (di Lucca et al. 2008) although, like in Italy, ethnic conflicts and tensions toward Muslim (im)migrant population exist (García-Sánchez 2014). In García-Sánchez’s (2010) study, Moroccan immigrant children attending Spanish public schools were able to enroll in a new Arabic language program, called Arabic Language and Moroccan Culture Teaching Program (LACM program) in their Spanish school, which was itself funded by the Spanish and Moroccan Ministries of Education. They were also able to attend after-school religious classes for Standard Arabic learning in a small oratory (‘msid’) mosque operated by a local Islamic cultural organization. The point here is that the immigrant children in this study engaged in more multilingual language learning contexts within and across educational institutions. Further, the public schools in the study had already been voluntarily participating in the LACM program for several years at the time the research was conducted.

The Spanish government not only jointly funded the program with the Moroccan government but also provided logistical support for those public schools that ran the program. As for their part, the Moroccan government was in charge of the Arabic language teacher assignment and curriculum design. Both governments collaborated and showed that they valued Standard Arabic learning as a critical element of the immigrant children’s religious, cultural, and linguistic heritage. However, although Moroccan children learned Standard Arabic with support from both inside and outside of school, they rarely used this language at home. Instead, Moroccan Arabic was most frequently spoken by the Moroccan immigrant children in everyday interactions within their homes and communities. It is reasonable to assume, however, that the children’s decision to more frequently use Moroccan Arabic in their daily lives cannot help but have been positively influenced by their exposure to Standard Arabic both in and outside of school (e.g., mosque) (i.e., García-Sánchez 2010, 2014; Moore 2006, 2008, 2010).

Though this study did not particularly explore the causal link between the study of Standard Arabic and the use of Moroccan Arabic, this school and community-sanctioned exposure to Standard Arabic doubtlessly contributed to the legitimacy and ‘positive vibes’ surrounding Arabic in general. At home, standard Arabic would not generally have been acquired or used by these migrant children otherwise. The children’s acquisition of Standard Arabic in schools and the subsequent positive carry-on effects on their use of Moroccan Arabic in and outside of schools demonstrate the vital influence of schools and other educational institutions on the children’s language of choice and its everyday use.

These two studies indicate how language ideologies interplay in the school system and how the ideologies have an impact on the present and future use of language(s) for academic and social purposes. Across two different contexts (Italy and Spain), schools have been shown to be critical agents and pathways through which (im)migrant children are interwoven into the cultures and communities of their host countries. At the same time, the school environment can either be a place where emerging multilingual children have opportunities to embrace their multilingualism (García-Sánchez 2010), or a place in which they have to narrow their focus and prefer one language over another in order to better orient themselves in a given situation (di Lucca et al. 2008).

In these contexts, language ideology plays a role either in more explicit spoken forms or in ways that are more implicitly indexed with practices representing “feelings or beliefs about language as used in their social worlds” (Kroskrity 2004, p. 498), which results in hegemonic, or harmonious (or both) language uses (Henderson 2017). As Duff (2019) indicates, access to L2 learning opportunities has been a meso-level concern, which involves educational institutions and communities. Namely, as shown in the cases (di Lucca et al. 2008; García-Sánchez 2010; Schecter and Bayley 1997) above, open access to L2 education can become one of the decisive factors for more harmonious and positive outcomes for bi- and multilinguals in those communities.

1.2. Emerging Multilingual Children in Korea: Language Practices within and beyond Classrooms

The primary research context investigated in this study is a Korean middle school, which has experienced a growing enrollment of Russian-speaking migrant students (Jang 2021). This student population has migrated to South Korea from Central Asia and Russia, aiming to reunite with parents who have been working in South Korea for several years prior to their migration. The parents settled in Korean society during the 2000s and early 2010s, mainly motivated by socio-economic disparities and political instability in their countries of origin following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 (Park 2013).

When examining the language and literacy practices of this specific population within and outside Korean classrooms, it becomes apparent that they exhibit distinct characteristics when compared to other migrants from Asian countries (e.g., China, Vietnam) and youths from international marriage families. What distinguishes Russian-speaking migrant youths in South Korea from other migrant populations is their prominent use of the Russian language within their community, often without proactive efforts to learn and use the Korean language. Concerns frequently arise regarding the exclusive use of the Russian language and the resulting lack of Korean proficiency, posing significant social challenges in Korea. These language-related difficulties have negatively impacted their social interactions with South Koreans (Kim 2018).

Even with South Korea experiencing a notable shift towards greater diversity, complexity, multiculturalism, and multilingualism, specific guidelines for developing classroom activities that foster the literacy practices of emerging multilingual students are absent in the national curriculum for English as a foreign language education and content areas, like Korean language arts, and mathematics (Jang 2021). Furthermore, emergent multilingual youths are frequently encouraged to use Korean exclusively within the classroom and are taught in content areas solely in Korean, lacking explicit support or guidance to fully utilize their diverse linguistic abilities. This limitation presents additional linguistic and academic challenges for these students, placing them in a position of developmental lag behind native speakers and making it challenging for them to catch up, let alone surpass native proficiency (Cross et al. 2022).

Namely, their language socialization practices within their households and communities exhibit notable distinctions when compared to their school language socialization practices. It highlights their socialization process involving multiple languages and/or a language dominant in a host country, aimed at sustaining and cultivating social relations across various contexts, including their homes, schools, and communities (e.g., Jang 2021). Surprisingly, despite these observations, there remains a paucity of studies that delve into their engagement in language socialization practices within institutional settings. By conducting situated and localized analyses that delve into language and literacy practices within Korean classroom contexts, studies can unveil the intricacies of how language ideologies come into play to enable or hamper the emerging multilingual youths’ engagement in language and learning practices and social interactions, as well as to build social relations.

2. Methodology

The data for this study constitute a segment of a larger research project spanning five years (2018–2022). The overarching research delved into local language practices, exploring how both migrants and local residents in Korea contribute to the evolution and transformation of linguistic landscapes in diverse contexts, including homes, schools, and communities. As a specific component of this extensive research initiative, the present study reported in this article primarily focuses on examining language socialization practices among Korean teachers and Russian-speaking migrant students in a regional middle school. The investigation covers a three-year period (2018–2020), during which the focal participants worked or were enrolled in the Bomun Middle School (pseudonym) detailed in the subsection below.

To uphold the ethical principles of this study, I, as the researcher, explicitly communicated the study’s purpose, data collection procedures, duration, potential risks, benefits, confidentiality measures, participant rights, and my contact information to all research participants. Only after providing this information did I request their signature on the consent form. In particular, the student’s consent form is divided into two distinct sections. One section necessitates parental consent for their children’s participation in the research, while the other section pertains to the student’s own consent for participation. Furthermore, to secure permission for data collection within the school, I obtained a letter of consent from the principal of Bomun Middle School. As for the data collection in classroom environments, while some teacher participants consented to video recording and photographing in their classrooms, in instances where access to the classroom environment was restricted, I relied on accounts provided by both students and teachers.

2.1. Researcher Positionality, Contexts, and Focal Participants

In this study, Jin (pseudonym), a bilingual Korean-English scholar and the article’s author, served as the principal researcher. She undertook data collection and performed initial data analysis. During the data collection phase, Jin provided weekly free online tutoring to migrant youths for their Korean and English language learning. Acting initially as an instructor, she gradually developed a strong rapport with the students. As the relationship evolved, Jin took on roles of mentor, elder sister, and supporter, engaging with the youths on various life issues within their households, communities, and schools. This involvement extended to interactions with their parents and schoolteachers, further shaping her relationships in these spheres.

This study was conducted at Bomun Middle School in Gwangsan (pseudonym), situated in the southwestern region of South Korea. Bomun Middle School is a relatively small regional school characterized by low student–teacher ratios. As the foreign population in Gwangsan has grown, so has the population of school-aged children. However, due to teachers’ limited experience in instructing and managing emergent multilingual speakers, the school faces challenges in effectively educating this student demographic.

Anticipating an increase in the enrollment of foreign students in the upcoming years, the school principal and teachers at Bomun Middle School expressed a keen interest in adopting inclusive and responsive teaching methods to better accommodate this specific student population. Despite this, until 2019, the school did not offer Korean as a second language (KSL) program beyond regular language classes, like Korean language arts and English. This was primarily because very few students experienced academic challenges resulting from limited proficiency in the Korean language. However, the dynamic shifted in 2019 when a total of seven foreign students, including five Russian speakers with limited Korean language proficiency, joined the school. This trend continued in 2020, with an additional six Russian-speaking students entering the school.

During the data collection period, Bomun Middle School had a staff of fourteen Korean-speaking teachers, none of whom had prior experience with inclusive teaching. These teachers expressed concerns about the future trajectories of their foreign students, emphasizing the significance of learning Korean within the school context. To address this, the school allocated funds in its budget to introduce a KSL program and afterschool programs for other content areas for emergent multilingual students, commencing in 2019. Despite these efforts, the emerging multilingual students continued to grapple with linguistic and cultural challenges within the school setting.

The research engaged seven Korean full-time teachers, including two Korean-English teachers (Ms. Kim and Ms. Min, pseudonyms), a high school admission consultant (Mrs. Park, a pseudonym), and others teaching subjects (Ms. Lee and Ms. Son in Korean language arts, Ms. Han in math, and Mrs. Kang in Korean as a second language, all pseudonyms). Additionally, eight Russian-speaking migrant youths participated in this study, identified by pseudonyms: Artur, Tanya, Leo, Lera, Sasha, Mark, Vika, and Katya. These migrant students originated from Kazakhstan, Russia, and Uzbekistan, predominantly communicating in and regarding Russian as their first language (L1).

Artur (grade 8 in 2020) entered middle school in 2019. Having migrated to Korea with his mother and younger brother in 2017 to reunite with his father, Artur emerged as the most active student, participating in a variety of language and literacy practices across diverse contexts, including home, school, and social media applications. While predominantly using Russian at home and within his Russian-speaking community, Artur exhibited a shift in language use within the school setting. Here, he primarily employed Korean when engaging in local language practices, but continued to use Russian when interacting with his Russian-speaking peers.

Another migrant student, Tanya (grade 9 in 2020), had lived with her grandparents in Uzbekistan for several years while her parents worked in Korea. In 2015, she moved to South Korea to join and reside with her parents. At the commencement of the data collection in 2018, Tanya was in grade 7. A very kindhearted individual, she willingly took on the role of a Korean-Russian translator for newly arrived Russian-speaking students and Korean teachers.

Leo (grade 8 in 2020), and Lera (grade 10), were siblings. They migrated to Korea in 2015 to reunite with their father, who had been employed in South Korea for several years before their arrival. When I first met Leo and Lera in 2018, they gained popularity among migrant youths in Gwangsan. They maintained a significant online presence with a high number of Instagram followers and were actively engaged both online and offline, participating in various regional and school events and festivals using English, Korean, and Russian.

Sasha (grade 9 in 2020) had lived with her grandparents in Uzbekistan for several years. Later in 2015, she was finally invited to join her parents in Korea. On our first meeting in 2018, Sasha (in grade 6) exhibited a strong desire to learn Korean with aspirations of becoming a K-pop star. She demonstrated a keen interest in sharing her daily experiences online and actively maintained communication with friends in both Uzbekistan and Korea through social media platforms such as KakaoTalk (a popular messenger app in Korea), Instagram, and Facebook.

In May 2020, Mark, a ninth-grader, along with Vika and Katya, both seventh-graders, initiated their participation in this study. They had recently migrated to South Korea and met each other in a Korean as a second language (KSL) program in school. Mark and Katya, hailing from Uzbekistan, and Vika, who migrated from Kazakhstan, had spent less than a year in a Korean school. All three of them communicated in Russian as their primary home language. They exhibited very limited proficiency in Korean and displayed relatively low levels of engagement in school compared to the other migrant youths introduced above.

In Mark’s case, this was his second year living in Korea in 2020, and due to family issues, he had to relocate to Gwangsan after spending almost one year in a different region, leading to more challenging moments during his resettlement. Like Mark, both Vika and Katya migrated to Korea in June 2019. Vika remained reserved in school but exhibited a vibrant online presence, enjoying capturing and sharing pictures and videos on social media. Katya was a deeply religious individual, prioritizing the cultivation and nurturing of connections within her church community. She also harbored a strong affinity for learning and using English, but held an opposing attitude toward Korean language learning and use, significantly impacting her overall school experience.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Considering the aim and the research questions of this study, Korean teachers’ and emergent multilingual students’ school language socialization practices were explored by focusing on “people’s lived experiences, […] locating the meanings people place on the events, processes, and structures of their lives and […] connecting these meanings to the social world around them” (Miles et al. 2020, p. 8). Thus, a qualitative case study approach is employed, allowing for a comprehensive investigation of a contemporary phenomenon (the case) within its authentic real-world setting. This method is particularly valuable when the demarcations between the phenomenon under examination and its surrounding context may not be immediately clear (Yin 2018, p. 15). To furnish corroborative support for this case study, I remained committed to the following foundational principles throughout the data collection process, as outlined by Yin (2018, p. 113): “(a) employing multiple sources of evidence; (b) maintaining a chain of evidence.”

Recognizing the critical importance of these principles in ensuring the robustness of this case study, the data were gathered through a variety of channels. It included conducting semi-structured interviews on a weekly basis, spending approximately an hour per interview. Additionally, the methodology involved making daily observations and detailed field notes during community visits between May and August and in December of 2018, 2019, and 2020. Furthermore, artifacts such as students’ academic tasks were collected during school visits. This data collection effort extended over a span of three years at Bomun Middle School in Gwangsan.

The data analysis process adhered to an inductive coding approach, coupled with the constant comparative method (Glaser and Strauss 2017). Upon gathering data from a wide array of sources, the information was transcribed into written form for data analysis. Subsequently, the data underwent inductive analysis and coding, with the goal of identifying noteworthy patterns and themes, all in alignment with well-established qualitative research methodologies (Duff 2008a).

Initial codes include ‘socialization into language(s)’, ‘the use of language(s) to socialize into school’, ‘school literacy practices’, ‘local language practices’, ‘monolingual/multilingual values embedded in school’, ‘flexible and fluid use of linguistic resources’, and so forth. As prominent themes emerged from this initial analysis, further theoretical categories were deduced, drawing upon both the existing literature and the insights gleaned from the data. This iterative process allowed for a comprehensive exploration of the dataset and the generation of meaningful findings. Overall, three major themes emerged throughout the data analysis: (1) monolingual orientation towards Korean language teaching and learning: creating Korean immersion classroom environments, (2) multilingual values and beliefs: teachers’ and students’ efforts to create a space to situate, access, and share more diverse resources, and (3) socialization into school language and/or using language(s) to socialize into school community.

In order to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the data and to facilitate the identification of patterns and themes across all the cases, a cross-case analysis approach was employed (Miles et al. 2020). It is important to note that the objective here is not to enhance generalizability, which may not be fitting for qualitative research. Instead, the aim is to assess the applicability and relevance of the findings to other similar language learning environments, with a focus on crafting more nuanced and robust explanations (Miles et al. 2020). Through the cross-case analysis of multiple instances, we were able to pinpoint the specific conditions under which particular findings manifested. This approach allowed for an assessment of the plausibility of extending these findings to other analogous conditions, thereby contributing to a richer understanding of the subject matter at hand (Miles et al. 2020).

3. Findings

In this section, I provide vivid descriptions of emerging multilingual migrants’ language socialization practices in school. In order to address my research questions, 1. How do Korean teachers’ and emergent multilingual youths’ language ideologies (re)shape bi- and multilingual language education in school? and 2. How do the youths comply with or show ambivalence/resistance toward the practices they are instructed in?, the Findings section is organized into three subsections (major themes): (1) maintaining and (re)creating monolingual Korean immersion classroom environments, (2) teachers’ and students’ efforts to create a space to situate, access, and share more diverse resources, and (3) socialization into school language and/or using language(s) to socialize into school community.

3.1. Sustaining and (Re)creating Korean Immersion Environments

Lera, the eldest among the focal student participants, made history as the initial foreign student to join Bomun Middle School in 2017. Subsequently, an increasing number of Russian-speaking foreign students enrolled in the school, constituting almost 30% of the total student population by 2020. Upon arrival in South Korea, they seemed to value Russian more than the Korean language, making a distinction between those languages by stating that Russian is a European language while Korean is an Asian language. Also, English was perceived as an international language that they should learn to communicate with people they met online spaces, such as Instagram, and to achieve a better socio-economic status when they become adults. Additionally, although they grew up in multilingual environments in Central Asia, as some of them were considered minorities, they seemed to have little knowledge of other languages (e.g., Uzbek language).

Given that none of the Korean schoolteachers had prior experience teaching this specific student demographic, for individuals who spoke Russian with limited knowledge of Korean, concerns arose regarding the student’s academic and Korean language proficiency development. Consequently, the teachers prioritized the students’ learning of the Korean language through exclusively monolingual practices, showing minimal regard for establishing multilingual language teaching and learning environments.

For instance, Mrs. Park recounted the story of a student who returned to Uzbekistan after a two-year stay in Korea, facing difficulties in Korean language learning. However, a year later, she returned to Gwangsan, expressing that her academic Russian skills were insufficient for following the Uzbekistan curriculum. Having spent three years shuttling between the two countries, the student missed crucial moments to catch up with academic work in both her home and host country.

In light of this story, Mrs. Park strongly advocated that migrant students should stay in their home country until they reached an age where they could manage their learning and living independently. Alternatively, they should exert substantial effort to enhance their Korean language proficiency if they decide to stay in Korea. Mrs. Park emphasized, “이렇게 되면 얘들은 갈 데가 없단 말이에요. (If they repeatedly fail to adjust to new languages and contexts, they will have nowhere to belong to.)” (Interview, 29 June 2019). Her statement reflects the empathy of Korean teachers towards migrant students who struggle to adapt to new languages and environments. It also underscores their belief that fostering proficiency in the Korean language is essential for supporting the academic success and overall career development of migrant students.

One of the most significant findings in this study is the students’ voluntary engagement in school activities closely intertwined with Korean language, culture, and history. Notably, the students proficient in Korean, such as Artur, Tanya, Leo, Lera, and Sasha, displayed active participation in school activities and frequently embraced practices solely in Korean. When queried about using Russian for academic tasks in the classroom, they asserted that Russian was unnecessary unless assisting newly arrived Russian-speaking peers in communication with Korean teachers and peers. Furthermore, they emphasized the need to complete academic assignments in Korean to attain good grades. Evidently, these students demonstrated a strong orientation toward the predominantly Korean school environment.

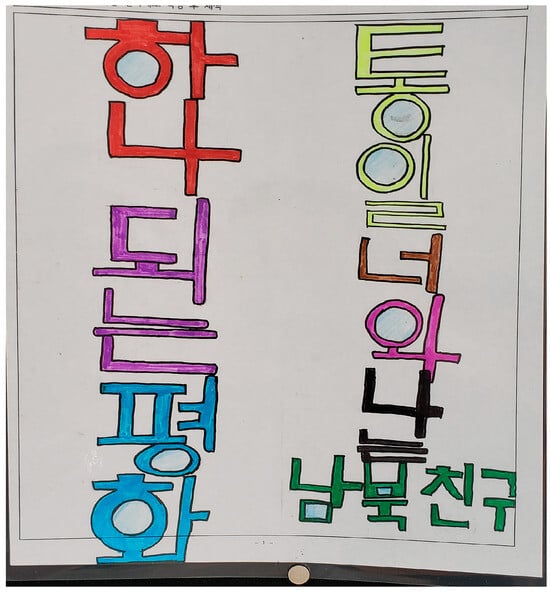

Below is an example of Tanya’s participation in the South–North Korean unification slogan creation event held at school (Figure 1). Drawing on her knowledge from social science and Korean history classes, Tanya crafted a slogan that eloquently conveyed her perspective on unity and friendship between North and South Koreans. Through the phrase “하나되는 평화, 통일, 너와 나는 남북친구”, (“United in Peace, Unification, North and South Koreans; You and I are friends”), she highlighted a shared humanity and bonds that transcended geographical and political boundaries.

Figure 1.

Tanya’s Slogan Wins at the Inter-Korean Unification Slogan Creation Event.

Despite being a migrant student, Tanya demonstrated a deep understanding of the significance of inter-Korean unification for Koreans. Her slogan revealed a heartfelt desire for people from both regions to perceive each other as friends rather than separate entities, and notably, she expressed this sentiment by creating her slogan in Korean. This example stands out as it showcases how migrant students can seamlessly integrate into a host country’s educational environment, mastering a language predominantly used in academic settings and becoming fixtures within the school community.

Likewise, the students’ active involvement in exclusive Korean-language and literacy practices was evident not only in core subject classrooms, like Korean language arts, Korean history, social science, and science but also in extracurricular programs, like the Korean as a second language (KSL) initiative. Additionally, especially for those who were quite proficient in Korean, there was a shared belief that using Russian in school could impede the enhancement of their academic proficiency in the Korean language. The following examples stem from a Korean history class, where Artur, Leo, and Sasha (in grade 8) collaborated with 18 Korean monolingual students.

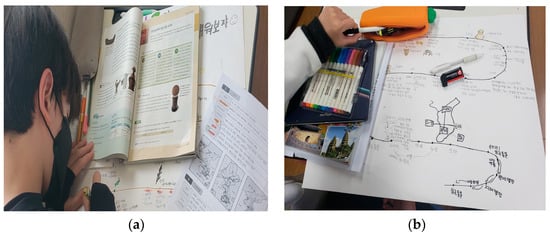

In Figure 2, illustrating images from the Korean history class, it is apparent that they individually constructed a timeline of Korean history, incorporating Korean language and images. Throughout this activity, involving reading and reflecting on historical content from the textbook, there was no need for the utilization of Russian. Moreover, given the fluent Korean proficiency of all three migrant students, they were adept at managing the task independently, requiring minimal assistance from their Korean teacher.

Figure 2.

Creation of Korean History Timeline by Students in Korean History Class. (a) Artur’s Timeline of Korean History; (b) Sasha’s Timeline of Korean History.

What stands out is that the Korean monolingual environments were not intentionally created. These classroom settings, existing for decades, persisted unchanged even as Russian-speaking migrants joined the same classrooms. The migrant students voluntarily integrated into these environments, embracing and developing their Korean language and academic skills in alignment with the prevailing language ideologies.

While some teachers, like Mrs. Park (as evident in her statement), contributed to the (re)creation and reinforcement of Korean monolingual values, the ideological atmosphere was not solely the result of teachers’ efforts. Instead, it emerged through the active engagement of both Korean and migrant students in local language and literacy practices, collectively reconstructing the environment as it stands today.

3.2. Teachers’ and Students’ Efforts to Create a Space to Situate, Discuss, and Embrace More Diverse Resources

While some teachers held firm monolingual beliefs when instructing the migrant youths in school, there were others—namely, two English teachers, Ms. Kim and Ms. Min, along with a Korean language arts teacher, Ms. Lee—who believed that encouraging students to use their own language(s) would not only support the development of their Korean language skills as a second language (L2) but also facilitate their adjustment to classroom environments. Notably, the two English teachers appeared to grasp the challenges that migrant youths might face in learning English while learning Korean as an L2. Ms. Kim, the English teacher, stated:

“[영어를] 한국어로 배우니깐 조금 힘들어 하는 것 같아요. […] 이해가 안 된다 싶으면 [러시아어를 모국어로 하는] 아이들끼리 서로 대화를 해서 서로가 서로를 이해시키고 하는 것 같아요. 러시어로 해주는 데 저는 못 알아듣지만 서로 이렇게 해서 물어보고… 그렇게 하는 것 같아요. […] [러시아어로 대화하는 게] 그 아이들이한테 도움이 될 꺼라고 생각을 하기 때문에… 그래서… 그 아이들은 영어도 하고 국어도 하고… 러시아어 이 세가지를 하는 거기 때문에… [영어 수업 시간에 러시아어로 대화하도록 해줘요.]” (“It seems a bit challenging for the migrant students [to learn English] in Korean. […] If they find it difficult to understand the content in English class, they tend to engage in conversations with each other, [especially with those who speak Russian as their native language]. Through these conversations in Russian, they try to help each other understand and keep up with the lessons. Even though I can’t comprehend when they converse in Russian, … it seems like they ask each other questions and try to follow the class. […] I believe that conversing in Russian is helpful for those students…. So… They use English, Korean … and Russian, engaging in all three languages. [That’s why I allow them to converse in Russian during the English class]”.)(Interview, 9 July 2020)

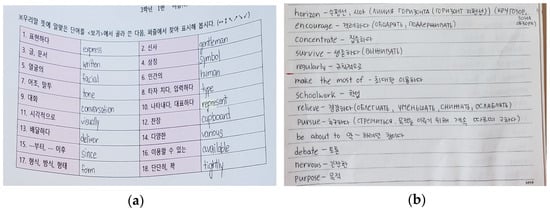

Although Ms. Kim and Ms. Min, English teachers, assigned academic tasks in both English and Korean, they frequently encouraged Russian-speaking migrant youths to utilize their linguistic knowledge when studying English. For instance, as depicted in the left image in Figure 3 below, a word list for English study was often provided in English and/or Korean. On the other hand, following the teachers’ guidance, Sasha created her own English word list in three different languages (English, Korean, and Russian), as shown in the right image of Figure 3. She made an effort to include the Russian definition within parentheses only when she faced difficulty understanding the English word’s meaning in Korean.

Figure 3.

Varied Local Language Practices among Students across English Classrooms. (a) Tanya’s English Word List in Two Languages (Korean and English); (b) Sasha’s English Word List in Three Languages (English, Korean, and Russian).

The examples illustrate the teachers’ and students’ endeavors to incorporate, discuss, and embrace a more diverse range of resources, thereby creating a multilingual space within the Korean school. Considering that the shift from a Korean monolingual to a multilingual student demographic occurred relatively recently, starting in 2017, the school environment remained predominantly Korean during the data collection period (2018–2020). Given this context, it was not a straightforward decision for both teachers and students to utilize Russian for academic success.

In light of these circumstances, the teachers’ and students’ efforts to incorporate Russian into their classrooms and academic work serve as a noteworthy example. This demonstrates the impact of local language socialization practices on the transformation of language ideology and identity, particularly within the confines of a Korean monolingual school environment.

3.3. Socialization within School Language and/or Using Language(s) to Socialize in School

The findings of this study reveal that emerging multilingual students (Artur, Tanya, Leo, Lera, and Sasha) with high confidence in Korean language use opt to socialize in the Korean language predominantly used in school. Conversely, newly migrated students’ (Mark, Vika, and Katya) school language socialization practices were often observed in two ways: (1) utilizing their entire linguistic repertoire to fulfill assigned tasks, and (2) remaining silent and inactive in the classroom. The language socialization process highlights instances of resistance or compliance with local language and literacy practices, particularly evident among the new Russian-speaking students, Mark, Vika, and Katya.

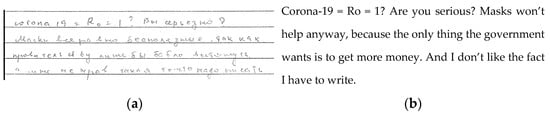

A noteworthy illustration is Mark’s written response to a math assignment assigned as homework. The task involved providing his reflections on a math essay discussing the mathematical background of achieving herd immunity to COVID-19, which was originally written in Korean. Mark’s math teacher, Ms. Han, encouraged him to take his time and, if he wished, complete it in Russian. Consequently, Mark submitted the assignment in Korean, English, and Russian; however, his Korean and English writing did not align with the task prompt. Regarding his Russian response (Figure 4), he shared his critical (and perhaps general) perspective on COVID-19, without specifically addressing the content of the provided math essay.

Figure 4.

Mark’s Written Response to a Math Classroom Task. (a) Mark’s Written Response in Russian; (b) Translation.

When questioned about why he did not address the main idea of the math essay in his initial written response but instead shared his general perspective on COVID-19, Mark explained that he disagreed with the concept of “herd immunity to COVID-19”. Additionally, he mentioned that Ms. Han would not understand his Russian. Subsequently, Ms. Han requested Mark to redo his work in English, the language he felt confident using as a novice learner of Korean, and the language she could understand. His English response significantly differed from the initial one, effectively addressing the points outlined in the essay.

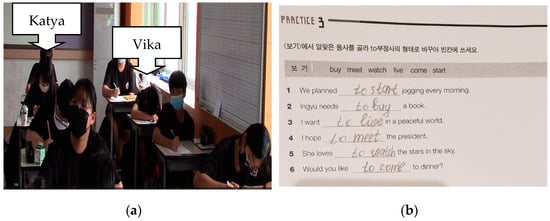

Similar to Mark, Katya also demonstrated a proactive approach to completing assigned tasks in a manner she could manage. Specifically, during English classes, Katya made an effort to complete tasks, leveraging her proficiency in English (as depicted in the right image of Figure 5), even though her proficiency in Korean was not sufficient to keep pace with other content classes, such as Korean language arts, math, and science. Also, when faced with tasks that necessitated the use of the Korean language, Katya sought permission from her teachers to use her cellphone in class. Then, she used it to translate and back-translate between Korean and Russian, in order to successfully finalize the tasks.

Figure 5.

Katya’s Voluntary Engagement in Classroom Activities Utilizing Her Linguistic Knowledge. (a) Photo of Katya and Vika in Classroom; (b) Katya’s Written Response in English.

On the contrary, Vika, Katya’s classmate, often rested her head on the desk and appeared listless during most of her time in the classroom, as depicted in the left image of Figure 5. While Vika was sociable and enjoyed conversing in Russian with peers outside the classroom, she consistently remained silent and inactive once the class began. This behavior was not unfamiliar to Ms. Lee and Ms. Son, Korean language arts teachers, and Mrs. Kang, the KSL program teacher, especially given that Korean was predominantly utilized in their classrooms, resembling the language socialization practices of newly migrated students in school. According to the Korean language teachers, this pattern raised concerns for novice Korean language learners, as they tended to exhibit more indifference towards their Korean language learning and displayed greater listlessness in the classroom compared to those with higher Korean language proficiency.

The examples highlight that the school language socialization practices of migrant students are contingent on their proficiency in the Korean language. Specifically, those with a high level of confidence in Korean tend to socialize in the school language, whereas the newly migrated students with limited Korean language knowledge either use their full linguistic repertoires or remain silent in the classroom.

4. Discussion

While schools are perceived as central places for language socialization processes and practices for school-aged children, as Bourdieu and Passeron (1990) insist, schools also act as venues for the reproduction of the social order and the reinforcement of social and cultural norms. Additionally, schools support the legitimacy and propagation of norms and social structures beyond the school context. Social norms that figure significantly in the lives of emerging multilingual children often relate to the use of home/heritage language in school.

However, traditionally, it has been considered appropriate to instruct children to follow or emulate the language of instruction, while their use of differing home language(s)/vernacular(s) in the school context has been reprimanded and corrected (di Lucca et al. 2008; Howard 2004, 2008; Moore 1999; Schecter and Bayley 1997; Son 2017). Because of the misbelief among educators that incorporating home language(s) or vernacular(s) in the school context hinders children’s learning of the more dominant language, the misbeliefs frequently influence the children’s language use both at home and in school (Howard 2008; Moore 2006). This has evolved into a social issue, allowing for its own forms of change and resistance that warrant further consideration in the education of migrant children, especially in emerging multilingual education settings (Baquedano-López and Kattan 2008).

As such, school is one of the important communities in which children are actively involved in language learning and where they socialize through languages and to use languages (Baquedano-López and Kattan 2008; Ochs and Schieffelin 1984; Schieffelin and Ochs 1986). Further, formal schooling creates either hegemonic or counter-hegemonic (or both) cycles of reproduction which become culturally and linguistically significant practices of the (im)migrant children’s communities. As Heath (1983) notes, “the boundaries between classrooms and communities should be broken … and the flow of cultural patterns between them encouraged” (p. 369).

This conceptualizes school as a place not only for social discontinuities between mainstream and non-mainstream communities but for linguistic and cultural discontinuities that (im)migrant children may experience between school and home community. Especially for the children living within and across transnational contexts, school is a valuable channel to experience language and cultural domains particular to their host countries; in the meantime, they are active participants who can be involved in any school activities through the medium of multiple and complex language repertoires, values, and norms, as well as through the process of acquisition, resistance, and negotiation of all linguistic and cultural factors come into play (Howard 2008).

The findings of this study reveal that while demographic change may not lead to ideological or cultural change in a brief space of time, teachers, and students eventually participate in (re)shaping language socialization practices in their place (e.g., di Lucca et al. 2008; Moore 1999; Schecter and Bayley 1997). Further, there appear possibilities that schools can be the supportive places for such processes, offering chances for young students to navigate through and critically cross-examine the linkages between languages, beliefs, power, and change to be prepared for a more democratic language learning environment (Avineri et al. 2015).

In this regard, the school language socialization examples of the Korean teachers and the emerging multilingual students are important in that they illustrate how the teachers and students encounter language and literacy practices in school that are embedded within and representative of language ideological conflicts. Namely, the findings reveal that multilingual students actively engaged in local language and literacy practices in classrooms where their multilingual resources were valued. In these classrooms, more linguistic and non-linguistic resources are available for negotiating meaning. Conversely, in monolingual-oriented classrooms, where teachers highlight the importance of Korean-only language practices, students tend to become silent and passive, affecting their socialization into the Korean school environment. The findings highlight the importance of creating a space where students can recognize, discuss, and embrace multilingual values, leading to active use of multiple languages. Clearly, this study emphasizes the role of multilingual language values and beliefs in school language socialization and underscores the significance of applying multilingual pedagogy for emerging multilingual youth (e.g., Alisaari et al. 2019; Bacon 2020; Bongartz and Torregrossa 2017; Manan and Tul-Kubra 2022).

Additionally, by making a comparison of language socialization between the migrant who are proficient in Korean language and those who are not within the school settings, it is identified that language ideological conflicts become more salient when newcomers are more explicitly socialized into particular language(s) while their ideologies are framed as problematic within strong monolithic ideology (e.g., di Lucca et al. 2008; Son 2017) and/or in cases of having a teacher with a strong assimilationist’s ideology (e.g., Moore 1999; Schecter and Bayley 1997).

Among the research on bi- and multilingual youth’s LS, only a few studies explore language contact and shift relative to linguistic ideologies (e.g., King 2000; Kulick 1998), and even the research on (im)migrant children’s language change regarding language ideological consideration is scant (di Lucca et al. 2008). As shown in most cases, the implementation of bilingual/multilingual programs is very limited, and sometimes bilingual programs are not operated for the sake of bi- and multilinguals. From ecological perspectives on language, Mufwene (2008) uses a metaphoric expression, “the actions of individual drivers on a highway influence the traffic flow” (p. 59) to illustrate how a communal language change may occur under interlocuter’s influences and as an adjustment to the activities that take place in a given context.

Indeed, just as what any one driver can perform depends on the overall highway traffic flow, there exists a similar dynamic of mutual dependence between language(s) or between individual speakers and the language community (Mufwene 2008). Thus, it is the role of schools to provide opportunities for children to participate in dynamic and multiple language learning experiences for linguistic development, along with the enhancement of cultural awareness. Such well-intentioned adjustments need to contribute to expanding the emerging multilingual migrant youth’s mainstream linguistic and cultural repertoires for their future trajectories as well (e.g., professional careers and higher education) (Duff 2008b).

5. Conclusions

Drawing on school language socialization, this study delved into how the language ideologies of Korean teachers and Russian-speaking migrant students influenced multilingual language education in school, examining the students’ compliance, ambivalence, or resistance toward instructed practices. The findings revealed that Korean teachers and proficient Korean-speaking students favored a monolingual orientation in Korean language teaching and learning. In contrast, Korean-English teachers and students with lower confidence in Korean valued multilingual language use, leveraging diverse linguistic resources to actively engage in classroom activities and complete academic tasks. These results underscore the role of local language and literacy practices in shaping their daily school experiences. Furthermore, the results underscore that migrant students with limited Korean proficiency adeptly utilize available resources in the classroom to either conform to or challenge the prevailing monolingual norms encountered as emerging multilingual migrant students. This suggests that their local language and literacy practices are not confined to either the Korean or Russian language but are dynamically (re)shaped through exploration, appropriation, and deliberate language choices, facilitating their integration into the school community.

The findings of this study underscore the importance of embracing multilingual language practices to enhance the engagement of newly migrated students in Korean-dominant classrooms and to (re)establish their membership within the local community, transcending their roles as foreigners. For recently arrived migrant students who may not always actively participate in local communities, providing opportunities to explore instances of multilingual language practices during L2 education or extracurricular programs can be particularly beneficial. This perspective also highlights the importance of critically examining their local communications in classroom contexts, considering its potential impact on their investment in L2 learning and power dynamics among individuals.

While the findings contribute to existing theoretical perspectives on school language socialization and underscore the importance of multilingual communication among migrant students, there are a few limitations to this study. Firstly, the data presented are derived from a specific group of Russian-speaking migrant youths in Korea, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to other emerging multilingual individuals in school contexts. Expanding the research to include a more diverse participant pool may offer a more comprehensive understanding of migrant youths’ school language socialization practices. Additionally, as this study focused on examples from middle school migrant youths, further exploration of language beliefs, values, and literacy practices among migrant youths at different age levels would be valuable for a more nuanced examination of language ideologies in educational settings and their impact on school language practices.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Columbus and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Ohio State University (protocol code 2018B0161 and date of approval (30 May 2018)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the first author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alisaari, Jenni, Leena Maria Heikkola, Nancy Commins, and Emmanuel Acquah O. 2019. Monolingual ideologies confronting multilingual realities. Finnish teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity. Teaching and Teacher Education 80: 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avineri, Netta, Eric Johnson, Shirley Brice-Heath, Teresa McCarty, Elinor Ochs, Tamar Kremer-Sadlik, Susan Blum, Ana Celia Zentella, Jonathan Rosa, Nelson Flores, and et al. 2015. Invited forum: Bridging the “language gap”. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 21: 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, Chris K. 2020. “It’s not really my job”: A mixed methods framework for language ideologies, monolingualism, and teaching emergent bilingual learners. Journal of Teacher Education 71: 172–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquedano-López, Patricia, and Ariana Mangual Figueroa. 2011. Language socialization and immigration. In The Handbook of Language Socialization. Edited by A. Duranti, E. Ochs and B. B. Schieffelin. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 536–63. [Google Scholar]

- Baquedano-López, Patricia, and Shlomy Kattan. 2008. Language socialization in schools. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Language Socialization. Edited by P. A. Duff and N. H. Hornberger. New York: Springer, vol. 8, pp. 161–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bongartz, Christiane, and Jacopo Torregrossa. 2017. The effects of balanced biliteracy on Greek-German bilingual children’s secondary discourse ability. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23: 948–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1990. Dependence through independence. In Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage Publication, pp. 177–219. [Google Scholar]

- Byon, Andrew Sangpil. 2003. Language socialization and Korean as a heritage language: A study of Hawaiian classrooms. Language, Culture and Curriculum 16: 269–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, Russell, Jacqueline D’warte, and Yvette Slaughter. 2022. Plurilingualism and language and literacy education. AJLL 45: 341–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Lucca, Lucia, Giovanna Masiero, and Gabriele Pallotti. 2008. Language socialization and language shift in the 1B generation: A study of Moroccan adolescents in Italy. International Journal of Multilingualism 5: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas Fir Group. 2016. A transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual world. The Modern Language Journal 100: 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, Patricia A. 2008a. Case Study Research in Applied Linguistics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, Patricia A. 2008b. Language socialization, participation and identity: Ethnographic approaches. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Edited by M. Martin-Jones, A. M. de Mejia and N. H. Hornberger. Boston: Springer, pp. 107–19. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, Patricia A. 2019. Social dimensions and processes in second language acquisition: Multilingual socialization in transnational contexts. The Modern Language Journal 103: 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, Kapitolina, and Hye Hyun Nam. 2023. Multilingual islands in the monolingual sea: Foreign languages in the South Korean linguistic landscape. Open Linguistics 9: 20220238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Inmaculada M. 2010. The politics of Arabic language education: Moroccan immigrant children’s language socialization into ethnic and religious identities. Linguistics and Education 21: 171–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Inmaculada M. 2014. Language and Muslim Immigrant Childhoods: The Politics of Belonging. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Barney, and Anselm Strauss. 2017. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Shirley Brice. 1983. Ways with Words: Language, Life and Work in Communities and Classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, Kathryn I. 2017. Teacher language ideologies mediating classroom-level language policy in the implementation of dual language bilingual education. Linguistics and Education 42: 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, K. 2004. Socializing respect at school in Northern Thailand. Working Papers in Educational Linguistics (WPEL) 20: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Kathryn. 2008. Language socialization and language shift among school-aged children. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Language Socialization. Edited by P. A. Duff and N. H. Hornberger. New York: Springer, vol. 8, pp. 187–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Jinsil. 2021. Transformative Potential of Writing Practices and Writer’s Agency: Focusing on Emergent Multilingual Students’ Cases in South Korea. Unpublished manuscript. Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Jinsil. 2023. Agency and Investment in L2 Learning: The Case of a Migrant Worker and a Mother of Two Children in South Korea. Social Inclusion 11: 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Kyung-hak. 2018. Children’s experiences of international migration and transnational identity with particular references to Koreyin children in Gwangju Metropolitan City. Cross-Cultural Studies 24: 61–103. [Google Scholar]

- King, Kendall. 2000. Language ideologies and heritage language education. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 3: 167–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Ministry of Justice. 2022. Immigration Statistics. Gwacheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea. Available online: https://www.moj.go.kr/moj/2411/subview.do (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Kroskrity, Paul V. 2004. Language ideologies. In A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology. Edited by Alessandro Duranti. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 496–517. [Google Scholar]

- Kulick, Don. 1998. Anger, gender language shift and the politics of Revelation in Papua New Guinean Village. In Language Ideologies. Edited by Bambi Schieffelin, Kathryn Woolard and Paul Kroskrity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Haiyoung, and Sun Hee Park. 2020. Research trends in Korean language education for learners from multicultural families. Asian and African Languages and Linguistics 14: 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Manan, Syed Abdul, and Khadija Tul-Kubra. 2022. Beyond ‘two-solitudes’ assumption and monolingual idealism: Generating spaces for multilingual turn in Pakistan. International Journal of Multilingualism 19: 346–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangual Figueroa, Ariana, and Patricia Baquedano-López. 2017. Language socialization and schooling. In Language Socialization. Edited by P. A. Duff and M. Stephen. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 141–53. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, R. P., Kenneth Gospodinoff, and Jeffrey Aron. 1978. Criteria for an ethnographically adequate description of concerted activities and their contexts. Semiotica 24: 245–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Matthew B., Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2020. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 4th ed. New York: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Leslie. 1999. Language socialization research and French language education in Africa: A Cameroonian case study. Canadian Modern Language Review 56: 329–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Leslie. 2006. Learning by heart in Qur’anic and public schools in northern Cameroon. Social Analysis: The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice 50: 109–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Leslie. 2008. Body, text, and talk in Maroua Fulbe Qur’anic schooling. Text & Talk—An Interdisciplinary Journal of Language, Discourse Communication Studies 28: 643–65. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Leslie. 2010. Learning in schools. In The Anthropology of Learning in Childhood. Edited by David F. Lancy, John Bock and Suzanne Gaskins. Lanham: AltaMira Press, pp. 207–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mufwene, Salikoko. S. 2008. How population-wide patterns emerge in language evolution: A comparison with highway traffic. In Language Evolution: Contact, Competition and Change. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, pp. 59–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs, Elinor, and Bambi Schieffelin. 1984. Language acquisition and socialization: Three developmental stories and their implications. In Culture Theory: Essays on Mind, Self, and Emotion. Edited by Richard Schweder and Robert LeVine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 293–328. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H. G. 2013. The Migration Regime among Koreans in the Russian Far East. Inner Asia 15: 77–99. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23615082 (accessed on 1 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Schecter, Sandra R., and Robert Bayley. 1997. Language socialization practices and cultural identity: Case studies of Mexican-descent families in California and Texas. TESOL Quarterly 31: 513–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieffelin, Bambi, and Elinor Ochs. 1986. Language socialization. Annual Review of Anthropology 15: 163–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Jeonghye. 2017. Language Socialization in the Post-Colonial Korean Diaspora in Japan: Language Ideologies, Identities, and Language Maintenance. Unpublished manuscript. Ph.D. dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, Bernard. 1972. The Language Education of Minority Children: Selected Readings. New York: Newbury House Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. New York: SAGE publications. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).