Abstract

This project explores the synchronic variation of participle forms in Brazilian Portuguese (BP). Despite general systematicity, the language maintains many historically irregular participles, which often compete with regularized variants. The language has also developed innovative participles, which tend to exist in variation with regular forms. Adopting a usage-based framework, the study examines how analogical processes affect persistent irregular participles and short-form forms in BP, emphasizing the role of grammatical context and frequency. Data are drawn from the Portuguese Web 2011 corpus, including 12 verbs with long-form Latinate irregulars (n = 4800) and 8 verbs with short-form forms (n = 3200). The results show that long-form Latinate irregulars are more common as adjectives and with the verb estar, while regularized forms are prevalent with ser and in perfect constructions. Conversely, short-form participles occur least frequently in perfect constructions, showing a tendency towards the maintenance of regularity in this context. Additionally, verbs that occur more often in perfect constructions are most resistant to innovation. These findings indicate that perfect constructions play a dual role in promoting and preserving regularity in BP and shed light on how grammar–internal relationships and contexts of occurrence play a role in language variation and change.

1. Introduction

This project investigates synchronic variation in Brazilian Portuguese (BP) past participle forms. Specifically, this analysis focuses on the variation of these forms as adjectives modifying nouns (1), with the verb estar (‘to be’) (2), with the verb ser (‘to be’) (often used in the passive voice)1 (3), and in perfect constructions with ter (‘to have’) (4). Throughout, the term ‘participle’ will be used as an umbrella term describing both true past participles in perfect constructions and participle-derived adjectival and predicative forms. Despite the general regularity of the formation of BP past participles through the addition of -ado/-ido to the verb root according to inflection class, there are two sets of verbs that do not conform to this model, namely, verbs with irregular long-form Latinate2 participles, and verbs that possess innovative, often termed ‘short-form’ participles. In both cases, divergent participle forms often exist in variation with forms that follow the regular template. This is exemplified in examples (1)–(4) for the verb imprimir (‘to print’), which can be expressed both as long-form Latinate irregular impresso and regularized imprimido.

| (1) | O | livro | impresso/imprimido | terá | características | únicas. |

| the | book | printed.m.sg | have.3sg.fut | characteristics | unique.f.pl | |

| ‘The printed book will have unique characteristics.’ | ||||||

| (2) | O | documento | está | impresso/imprimido | em | papel | grosso. |

| The | document | be.3sg.pres | printed.m.sg | on | paper | thick | |

| ‘The document is printed on thick paper.’ | |||||||

| (3) | O | livro | foi | impreso/imprimido | por | uma | só | editorial. |

| The | book | be.3sg.pret | printed.m.sg | by | one | only | publisher | |

| ‘The book was published by only one publisher.’ | ||||||||

| (4) | Ele | já | tinha | impresso/imprimido | o | documento. |

| He | already | have.3sg.imp | printed.m.sg | the | document | |

| ‘He had already printed the document.’ | ||||||

Similarly, innovative short-form participles in BP, which are often homophonous with other verb forms, most often first-person singular of the present indicative, exhibit alternation with regular forms. Example (5) illustrates the alternation between regular ganhado and short-form ganho for the verb ganhar (‘to earn/win’) in an adjectival context, though these forms can also be used in the same grammatical contexts as shown in (1)–(4). The innovative form ganho is identical to the first-person singular present indicative verb form meaning ‘I win’.

| (5) | Eles | recebem | uma | moeda | para | cada | ponto | ganhado/ganho. |

| They | receive.3pl.pres | a | coin | for | every | point | won.m.sg | |

| ‘They receive a coin for every point won.’ | ||||||||

Historically, participles in Latin and Old Portuguese showed greater irregularity than synchronic forms (Laurent 1999). Many previously irregular participles have been regularized in Modern BP, which has been described as a process of analogy and leveling towards increased systematicity in the participle paradigm (Chagas de Souza 2011; Laurent 1999). Significant research has been undertaken with regard to contemporary BP past participle variation (Chagas de Souza 2011; Huber 1933; Lobato 1999; Miara and Coelho 2015; Schwenter et al. 2019; Villalva and Jardim 2018; Queriquelli 2018; inter alia), though quite often with focus on innovative forms. Despite their mention in previous work, less is known about verbs whose long-form Latinate irregular participles persist synchronically, such as morto (‘dead’) for morrer (‘to die’), and their potential for regularization (cf. morrido, ‘dead’) (Laurent 1999, p. 74). In focusing on both regularization and innovation, the present analysis shows that these processes share some of the same underlying mechanisms. Specifically, this work applies usage-based frameworks of linguistic analysis to the investigation of synchronic participle variation in BP and demonstrates that this variation is at least in part governed by analogical processes that are conditioned by grammatical context, contextual probabilities, and frequency.

2. Background

2.1. Previous Work on Portuguese Past Participles

Historical variation in Portuguese past participles has continued from Old Portuguese to Modern Portuguese. Attestations of variation between standard and regularized participles in Portuguese can be found, going as far back as the 15th century. Examples of this are shown in (6) and (7), where the regularized abrido is used in place of irregular aberto from the verb abrir (‘to open’), and morrido is used instead of the irregular form morto for the verb morrer (‘to die’), respectively. Both examples were extracted from the Genre/Historical Corpus do português (Davies 2004).

| (6) | E | sera | abrido | a | vos. |

| and | be.3sg.fut | open.part | to | you | |

| ‘And it will be opened to you.’ | |||||

| Livro de vita Christi (1446) | |||||

| (7) | Tinha | morrido | o | Rey | do | Egypto. |

| have.3sg.imp | die.part | the | King | of | Egypt. | |

| ‘The king of Egypt had died.’ | ||||||

| Promptuario historico II, Frei Manoel da Mealhada (1760) | ||||||

Despite historical attestations of regularized abrido and morrido, neither underwent a full process of regularization. However, there are many verbs in Portuguese that have been fully regularized in the language, for which the regularized variants are the dominant variant and are, in many cases, used categorically. The changes that Portuguese past participles have experienced have been described in three phases (Chagas de Souza 2007). In the first phase, irregular forms from Latin existed in doublets, competing with their regularized counterparts. Examples of this are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample of long-form Latinate double participles in Portuguese.

In the second phase, Chagas de Souza (2007) suggests that homophony between persistent irregular forms and first-person singular present indicative verb conjugations allowed for the analogical extension of this pattern to other verbs in the first conjugation class (-ar) that did not originally exhibit this pattern. For example, the irregular participle for the verb aceitar (‘to accept’) is aceito, which is identical to the conjugated verb of the first-person singular of the present indicative. Table 2 shows some examples of verbs in the first conjugation to which this pattern was extended.

Table 2.

Sample of double past participles for -ar verbs in Portuguese.

In a diachronic analysis of ‘double participles’ in Portuguese, Hricsina (2019) finds that these pairs began to be used around the 14th century and began to increase significantly during the 15th century. It is important to note that, in Modern Portuguese, some of the innovative participles in the first conjugation (-ar) are considered to be standard, such as pago (cf. pagado, ‘to pay’), while others (e.g., chego ‘to arrive’) are not (Chagas de Souza 2007).

Finally, in the third phase, this pattern expands by analogy to other conjugation classes (i.e., -er, -ir). Examples of this extension are shown in Table 3. Again, it is critical to note that most of the innovative participles in these conjugation classes are not considered standard in Modern Portuguese (Chagas de Souza 2007).

Table 3.

Sample of double past participles for -er/-ir verbs in Portuguese.

These last two stages have brought about an abundance of competing participles forms in Modern Portuguese, which are often referred to as particípios duplos (‘double participles’) or ‘short-form’ participles (Lobato 1999). In these pairs, one participle generally follows the regular pattern of adding -ado or -ido to the infinitival stem. The other participle is identical to the first person singular present indicative verb conjugation (Perini 2002). Examples of these double participles are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Examples of regular and innovative double participles in Portuguese.

Much of the synchronic variation exhibited in Portuguese participles can be attributed to various stages of the processes described by Chagas de Souza (2007). Traditional grammars have suggested that the distinction between regular and short-form participles in Portuguese is a question of syntactic structures, namely, that regular participles are used in compound tenses, and the innovative analogical participles are used as adjectival complements (Cunha and Cintra 2016). More specifically, it has been suggested that regular participles are used with the auxiliary verb ter (‘to have’) and that short-form participles are generally used with the copular verb ser (‘to be’) or without an auxiliary (Perini 2002, p. 153). While some traditional grammars have acknowledged that there are exceptions to this pattern (cf. Perini 2002, p. 154) and that there are some participles that are used across different types of grammatical constructions, more recent research has shown that the situation is far more complex.

Previous work has shown that the selection between the two forms is most strongly determined on a verb-by-verb basis (Schwenter et al. 2019), indicating the role of specific verb lexemes and their frequency and uses. Furthermore, authors such as Hricsina (2019, p. 89) suggest that this lexical determination of which participle types are used in different grammatical constructions is a feature of a change in progress. Similarly, Chagas de Souza (2011) proposes that the lexical determination of past participle selection is part of a directional syncretism toward the first-person singular of the present indicative.

In their corpus analysis of Portuguese participles, Schwenter et al. (2019) found that for participle pairs that include a regular form and an irregular form based on the first-person singular of the present indicative, the irregular form was used 69% of the time. Conversely, for participle pairs composed of a regular form and an irregular form of some other type (e.g., long-form Latinate irregulars), the irregular form was used just 32% of the time. These findings reveal that long-form Latinate irregular participle forms are more often dispreferred as compared to their regularized counterparts in Portuguese, and that for verb lexemes that have regular and short-form participles, the latter are preferred. The authors conclude, therefore, that not only do grammatical function and verb lexeme play a role in participle selection, but the morphological shape of the participle itself is an important predictor of regular vs. irregular usage rates.

2.2. Usage-Based Grammar and Linguistic Analogy

Critical to the present work are explanatory frameworks for the participle patterns observed in BP. One such framework is Usage-based Theory. This approach to understanding linguistic variation views grammar as the cognitive organization of individuals’ experience with language (Bybee 2006), with some scholars going so far as to assert that grammar is an emergent phenomenon that is continually reshaped by its specific contexts of use (Hopper 1987). From the most general standpoint, our cognitive representations of language forms, their meanings, and the contexts they occur in are constructed out of our encounters with the forms in use. Contrary to generative theoretical approaches that focus on abstractions of language to the exclusion of how language is used in practice, usage-based approaches focus on how individuals’ cumulative experiences with language shape variation and change. In this way, language forms are conventionalized to varying degrees out of our experiences with them, meaning that form, frequency, and grammatical context play critical roles in cognitive representations of language.

In usage-based approaches, a critical mechanism of change is linguistic analogy. This refers to the process by which irregular forms, or forms that are perceived as irregular, are remade in the shape of other linguistic forms that are morphologically predictable. This process has been described as being relatedrelated to child language acquisition, wherein children produce new forms by accessing similar forms in the lexicon and applying the same pattern to the new items (MacWhinney 1978) and has long been thought to be a critical process in language change (Anttila 1977; Blevins and Blevins 2009; Hock 1991). Importantly, historical changes in Portuguese towards greater participle systematicity have been attributed to the mechanism of linguistic analogy (Laurent 1999; Chagas de Souza 2007).

The present work adopts the notion that this type of linguistic analogy is part of a cognitive process in which speakers transfer knowledge from one set of linguistic forms to another based on perceived similarities between them. This type of leveling is more likely to occur among closely related forms (Bybee 2010; Blevins and Blevins 2009). In the case of Portuguese participles, analogy to regular participle formation within the verbs of the same conjugation class is far more likely to occur than analogy to verbs of a different conjugation class or to verb forms that are not past participles. For example, the historically irregular Latinate participle nato for the verb nascer (‘to be born’) is thought to have regularized to nascido, based on the application of the morphologically predictable rule applied to other verbs in the same conjugation class, which involves the addition of -ido to the verbal stem. Additionally, analogical processes tend to affect paradigms that are less frequent and permit more alternations in those that are more frequent (Bybee 2010), which can be attributed to the strength of the mental representations of more frequent paradigms for speakers of the language (Bybee 1985). This mechanism of language variation and change is a critical explanatory framework for understanding not only historical change of Portuguese participles but also synchronic variation. On the one hand, these processes of analogical change affected many historically irregular participles from Latin to Portuguese. Still, not all irregular past participles were regularized in this way, resulting in verbs that either fully maintain long-form Latinate irregular participles or verbs that exhibit synchronic variation between long-form Latinate irregulars and regularized variants. On the other hand, verbs that have developed innovative participle forms in Portuguese have been described as undergoing analogical processes to first-person singular verb forms, driven by the existence of this historical overlap for other verbs. Importantly, the present analysis addresses the extent to which these analogical processes are synchronically applied to both persistent long-form Latinate irregular participles and to the extent of use of short-form participles forms in BP.

2.3. Frequency and Probability

A central tenet of usage-based approaches to grammar is the important role of frequency in linguistic patterns. Linguistic frequency refers to the number of times that a particular language unit occurs in a given corpus or data set and has been used to approximate the number of times speakers are likely to experience specific linguistic forms. Following usage-based approaches, specific instances of grammatical elements are stored in memory, and their frequency of use has an impact on their mental representations (Bybee 2006, 2010). Linguistic elements that speakers more frequently encounter are said to have higher degrees of representation in the mental lexicon (Bybee 1995), making them more resistant to change and more likely to serve as the basis for the development of new forms (Bybee 2003; Bybee and Beckner 2010; Langacker 1987).

When considering frequency and analogy as mechanisms of language variation and change, the relevance of the linguistic contexts in which variable forms occur cannot be ignored. In lexical diffusion models of sound change, it has long been considered that specific words undergo change, which can then gradually propagate to other words that share similar sounds or phonological patterns before potentially spreading throughout the lexicon. Importantly, these models have further developed to include a consideration of the influence of contextual factors on the rates of linguistic change. For example, the frequency with which a word occurs in a linguistic context that promotes a particular sound change can impact the rate at which the word undergoes said change. In a critical work on this topic, Bybee (2002) finds that patterns of /t,d/ deletion in American English occurred more readily in words that occurred more often before vowels than in words before consonants, demonstrating that the linguistics contexts of use of a given word can affect the rate of sound change.

While these sorts of models have been more frequently applied to sound-based language change, they can also be applied to morphosyntactic phenomena. In his analysis of lexical decision models, Baayen (2010) finds that overall word frequency predicts only a small portion of the variance observed in lexical decision tasks. Instead, he finds that the probabilities associated with local syntactic and morphological co-occurrences, referred to as contextual probabilities, are a far more powerful predictor of lexical decisions.

Relatedly, Schmid (2015) proposes that the syntagmatic associations between linguistic forms can be strengthened in a number of ways. First, the repetition of linguistic sequences strengthens the syntagmatic associations between their form and meaning. Second, the repetition of similar linguistic elements under similar contextual circumstances strengthens the relationships between them and facilitates their activation in comparable linguistic environments, termed contextual entrenchment. Most crucially to the present analysis, Schmid proposes that this process leads to increased routinization of linguistic forms through analogy as a cognitive process, which allows for the identification of the shared role that different elements play in a given linguistic context. In other words, the strength of association between co-occurring linguistic forms facilitates the development of schematic constructions in our mental grammar. These concepts of contextual probabilities and contextual entrenchment fit into previously established frameworks of linguistic analogy and regularization. In particular, linguistic analogy reforms verbal paradigms in such a way that functionally similar elements also become similar in form, referred to as paradigmatic iconicity (Croft 2003, 2012). These frameworks are critical to the analysis that follows, which demonstrates the important role of contextual relationships in processes of regularization and innovation in BP past participle forms.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Corpus Description

Data are drawn from Sketch Engine’s 2011 Portuguese Web Corpus (ptTenTen11), which contains 4.6 billion words (Kilgarriff et al. 2014). The corpus creators used the software Heritrix (Mohr et al. 2004) to identify and download text from the Portuguese-speaking Internet and the software program FreeLing (Padró et al. 2010) to clean and tag the data. The corpus includes Internet texts from throughout the Portuguese-speaking world. For the purpose of this analysis, the selection was restricted to Brazil only.3

3.2. Data Collection Procedures

For the data in the present analysis, I collected two different data sets: one including verbs that included irregular long-form Latinate past participles and one that included verbs with short-form past participles, following similar procedures. For the former, I examined a total of 46 verbs in Portuguese that have irregular long-form Latinate participle variants that persist synchronically to varying degrees, based on previous descriptions of irregular past participles in Portuguese (Chagas de Souza 2011; Laurent 1999; Perini 2002; Schwenter et al. 2019). I used the Corpus Query Language (CQL) of the ptTenTen11 corpus to simultaneously search for all morphological variants of a past participle type for each verb. For example, for the verb imprimir (‘to print’), I searched [word = ‘imprimido|imprimidos|imprimida|imprimidas’] to collect regularized tokens, and [word = ‘impresso|impressos|impressa |impressas’] to collect long-form Latinate irregulars. Some verbs required additional query specification due to overlap with words from other lexical categories. For example, the masculine forms of the irregular participle of the verb morrer (‘to die’), morto(s), are homophonous with the noun meaning ‘dead person/people’, and the masculine singular form of the irregular participle for the verb fixar (‘to attach’) is also a noun meaning ‘landline’. In cases like this, I included additional specifications in the CQL to exclude words tagged as nouns.

Regarding the verbs with short-form variants, I followed a similar procedure. However, as the short-form participle forms are homophonous with other verb forms, I added additional restrictions to the query, specifying exclusion of certain verb conjugations. For example, the short-form forms for the verb pagar (‘to pay’ overlap not only with the noun pago(s) (‘payment(s)’) but also with pago (‘I pay’), pagas (‘you paga’), paga (‘you/he/she pays’). I searched for [word = ‘pagado|pagado|pagada|pagadas’ and tag! = ‘N.*|V.IP123’] to collect regular tokens, and [word = ‘pago|pagos|paga|pagas tag! = ‘N.*|V.IP123’] to collect a sample of the short-form variant. Any nominal or conjugated verbal uses that were not eliminated following this procedure were excluded during the coding phase. For both data sets, I also recorded the total number of tokens of each participle type in the corpus and determined which verbs demonstrated sufficient variation for inclusion in inferential analysis as had been established previously via power analysis, which in the present case was 200 tokens per verb per participle type.

For each verb that had enough attestations in the corpus for each participle type, I collected a balanced random sample of tokens using Sketch Engine’s built-in random sampling feature. This tool works by randomly selecting the number of lines indicated by the user from all parts of the corpus. According to Sketch Engine’s documentation, the tool is designed to reduce the number of lines while at the same time maintaining the representativeness of the sample. For verbs with high token counts of both participle types, I used the built-in random sampling tool in the corpus to collect 400 tokens per type, for a total of 800 per verb. From these 400 tokens, I collected and coded the first 200 eligible tokens per verb for grammatical context (adjective modifying a noun, perfect construction with ter4, with estar or with ser). I collected a total of 200 tokens per type for each verb form, for a total of 400 tokens per verb. For the data set, which included long-form Latinate irregulars and regularizations, this procedure produced a total of 4800 tokens, or 400 tokens, for each of the 12 verbs that showed variation and had sufficient tokens for statistical inference. For the data set, including regular forms and short-form variants, this procedure resulted in a total of 3200 or 400 tokens for each of the 8 verbs analyzed.

3.3. Statistical Methods

For both of the data sets presented in this paper, I calculated the overall frequency of each verb lexeme using Sketch Engine’s built-in tool, which provides frequency per million words. I then calculated the ratios between particular types in order to capture their relative frequencies. For the subset of verbs containing long-form Latinate irregular participles, the relative frequencies range from 1.60 × 10−5 to 35,920.1 (median = 1.23 × 10−2), indicating a massive right skew for this measure, where values from zero to 1 indicate that the irregular value is more frequent, and values above 1 indicate greater relative frequency of the regularized variant. For the subset of verbs containing short-form participle forms, the relative frequencies ranged from 0.0016 to 125.45 (median = 0.154), also indicating right-skew, though not as extreme as in the first subset of the data. Therefore, for both subsets of the data, I log-transformed the relative frequency values to meet the necessary assumptions for statistical analysis. I then employed a two-tailed t-test for each data set to analyze the relationship between overall verb frequency and the relative frequencies of participle types.5

Additionally, in order to examine the potential role of lexeme frequency, I searched for each verb in both samples in the corpus, which returns a calculation of the number of occurrences of that word per million words in the corpus. For the sample containing long-form Latinate irregulars, verb lexeme frequencies ranged from 0.7 to 261.9 (median = 16.7). For the short-form data set, lexeme frequencies ranged from 20.43 to 481.75 (median = 93.5). I, therefore, log-transformed these measures for both data sets for similar reasons to those described above. Finally, in order to investigate the potential role of contextual frequencies in patterns of regularization and innovation, I also followed similar procedures to calculate the frequencies of each of the verbs in each of the grammatical contexts under consideration in these analyses.

Statistical analysis was performed using R (R Core Team 2022). For each separate data set, I generated random forests (Liaw and Wiener 2002), which uses series of decision trees to classify the relative strength of each predictor value with regard to the dependent variable. Based on this output, together with theoretically informed predictions, I created a series of nested models using the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015), considering grammatical context, verb lexeme frequency, and verb lexeme frequency in each of the grammatical contexts6 under consideration as potential predictors. For the sets of models for each grouping of the data, I included a random intercept for the verb. Though further random effects are desirable to create the optimal model, additional specification was not possible due to convergence issues despite optimization. Future analyses with additional data will attempt to resolve this issue. Finally, I tested the goodness of fit for each of the models using the anova() function in R, a likelihood ratio test (Fox and Weisberg 2018) to select the optimal model for each data.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Long-Form Latinate Irregulars

4.1.1. Description of the Data

Of the 38 verbs examined, 2 showed no use of irregular forms (devolver, ‘to return’; dissolver, ‘to dissolve’), 1 showed no evidence of regularized forms (predizer, ‘to predict’), and 2 showed categorical usage patterns across grammatical contexts. Specifically, there was a clean split for the verbs fixar (‘to possess’) and juntar (‘to join’), for which there were no instantiations of long-form Latinate irregulars fixo or junto in perfect constructions. These verbs were excluded from further analysis, leaving a total of 35 verbs that had attested use of both irregular and regularized participles that were used in overlapping grammatical contexts. Of these verbs, benzer (‘to bless’), corromper (‘to corrupt’), desenvolver (‘to develop’), despertar (‘to wake up’), eleger (‘to choose’), envolver (‘to include, to contain’), fritar (‘to fry’), imprimir (‘to print’), morrer (‘to die’), revolver (‘to revolve’), romper (‘to break’), soltar (‘to release, to detach’) showed sufficient variation for statistical inference, as established by power analysis. See Appendix A for the full list of verbs, token counts, and usage distributions.

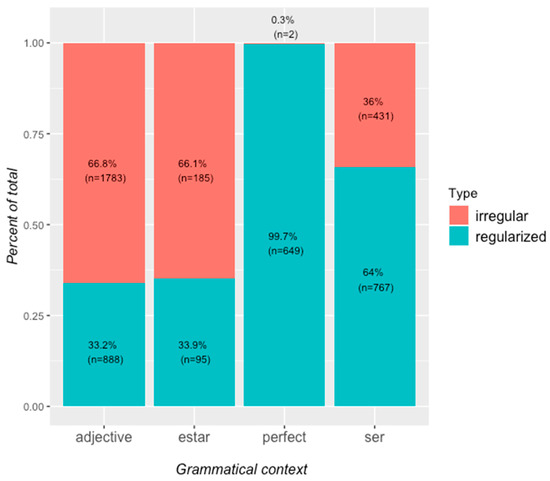

For these 12 verbs, I collected a total of 4800 past participle tokens, which included a total of 2671 tokens as adjectives, 280 tokens with estar, 1198 tokens with ser, and 652 tokens in perfect constructions. The overall results show that the irregular participle variants occurred more frequently as adjectives and with the verb estar, while the regularized forms occurred more frequently with ser and in perfect constructions. Specifically, 66.8% (n = 1783) of adjectival tokens and 66.1% (n = 185) of all tokens with estar in the sample occurred with the irregular participle variant. Conversely, 64% (n = 767) of tokens with ser occurred with the regularized variant, and perfect constructions nearly categorically (99.7%, n = 649) use the regularized form, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participle types by grammatical context for long-form Latinate irregulars.

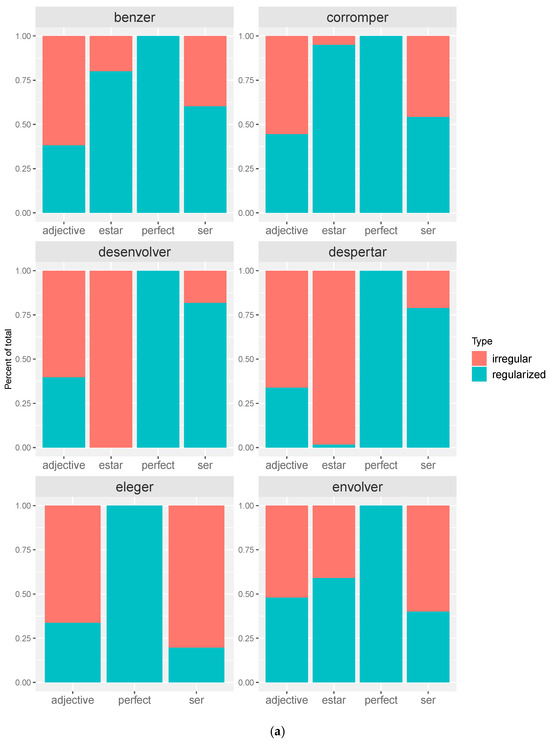

However, there was still variation by verb lexeme. Figure 2a,b shows the distributions of irregular and regularized participle types across grammatical functions for each verb. These figures show a clear trend of near-categorical use of the regularized variant in perfect constructions across all verbs. Additionally, for the majority of verbs, adjectival tokens and tokens with estar showed the lowest rate of regularized forms across all grammatical contexts. However, there are a few exceptions to general trends in these data. For example, while the majority of the verbs in the sample show higher rates of regularized forms with the verb ser, the verbs envolver, morrer, and soltar all show preference for the irregular participle in this grammatical context. Despite some idiosyncrasies by verb, there appears to be general consistency in preference for the regularized variant in perfect constructions and a preference for irregular variants as adjectives and with estar.

Figure 2.

(a) Distribution of participle types by context for verbs with long-form Latinate irregulars. (b) Distribution of participle types by context for verbs with long-form Latinate irregulars.

4.1.2. Inferential Analysis of Long-Form Latinate Irregulars

Following the described statistical procedure, the best-fit model for the data identified grammatical context as the sole main effect. The output of this regression model is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Best fit logistic regression model output for BP long-form Latinate irregulars.

The output of this best-fit model reveals that in these data, regularized forms are statistically significantly more likely to occur with ser and in perfect constructions than as adjectives and with estar. Conversely, the irregular variants are more likely to occur as adjectives and with estar than are regularized variants. Overall, these results indicate the critical role of grammatical context in the variation between long-form Latinate irregular participle forms and their regularized counterparts.

4.2. Short-Form Participles

4.2.1. Description of the Data

As previously noted, Brazilian Portuguese also possesses short-form participle forms that are often homophonous with other verb forms and, in particular, with the first-person singular of the present indicative. In this section, I describe and analyze a subset of these verbs with short-form past participles in order to compare and contrast their patterning with the participle types described in the previous section. Since the development of innovative participle forms in Brazilian Portuguese is a change in progress (Chagas de Souza 2007; Hricsina 2019), the group of verbs to which this change applies is ever-changing. Therefore, due to the limitations of the present analysis, 10 verbs that have been described as having short-form participle forms (Chagas de Souza 2007; Hricsina 2019; Perini 2002; Schwenter et al. 2019) were selected for analysis.7

The verbs examined in the present analysis are chegar (‘to arrive’), empregar (‘to employ’), entregar (‘to turn in’), ganhar (‘to win, to earn’), gastar (‘to spend’), limpar (‘to clean’), pagar (‘to pay’), pedir (‘to ask for’), pegar (‘to catch, to take’), and trazer (‘to bring’). Though all of the verbs examined showed variable use across grammatical contexts, two verbs did not have sufficient short-form tokens in the corpus for inferential analysis (pedir, ‘to ask for’; trazer, ‘to bring’). These verbs, reported in Table 6, were excluded from further analysis, leaving a total of eight verbs that showed sufficient variation for statistical analysis. While only the masculine singular participle form is listed in the table for the ease of the reader, the totals include all gender and number forms.

Table 6.

List of BP verbs with short-form participles in the present analysis.

I also calculated the relative frequencies of short-form to regular participles for each verb in this data set. The results of a two-tailed t-test show a significant relationship between verb frequency and the relative frequency of regularized participles for these 10 verbs included in the present analysis (t = 3.8899, df = 9, p-value = 0.003675). Additionally, Pearson’s correlation coefficient for these measures shows a moderate correlation between verb frequency and relative participle frequency (r = −0.6). This relationship indicates that, in general, more frequent verb lexemes show fewer instantiations of short-form participles than less frequent verbs in this data set. Nevertheless, this tendency is not absolute. While there is a general tendency for lower frequency verbs such as limpar and gastar to have high rates of innovation, empregar is a notable exception. Additionally, while higher frequency verbs chegar and trazer show lower rates of innovation, ganhar shows 18.70% regularization despite a higher frequency. This indicates that lexeme frequency is not the sole predictor of participle innovation. Other factors, such as the form of the short-form participle, the relationship between specific participles and other grammatical categories (e.g., nominal gasto(s) and emprego(s) from gastar and empregar, respectively), and more may play a role in the overall rates of innovation and will be explored in future analyses.

However, a stronger trend is shown regarding the overall rate of occurrence in perfect constructions and the degree of regularization for these verbs. Specifically, verbs in this sample that tend to occur more frequently in perfect constructions in the corpus overall also tended to show lower rates of innovation. While this analysis could be made more robust by the addition of more verbs, the results of a two-tailed t-test show a significant relationship between the number of tokens in perfect constructions in the corpus and the relative rate of innovation for these 10 verbs (t = 2.5076, df = 9, p-value = 0.03344). Additionally, Pearson’s correlation coefficient for these measures shows a small negative correlation (r = −0.32).

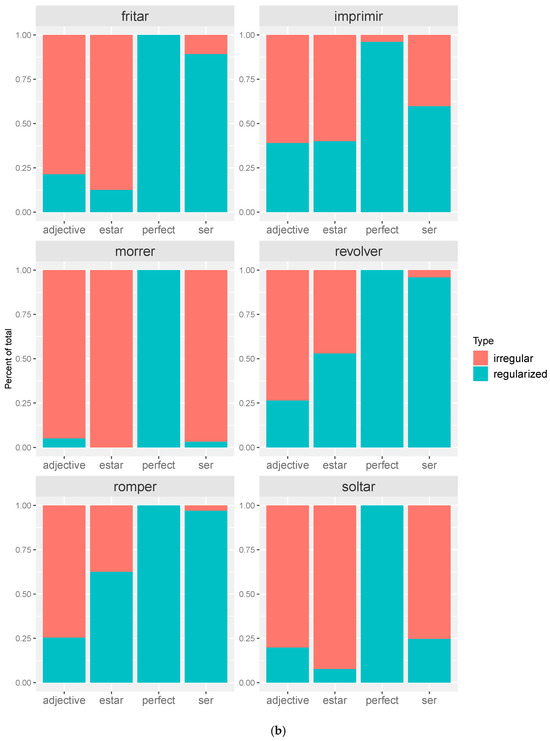

For the eight verbs that had sufficient tokens for analysis, I collected a total of 3200 past participle tokens. The overall results show that both short-form and regular participle types are used variably across all grammatical contexts. However, these data show the highest preference for the regular form in perfect constructions, specifically, 75.8% (n = 1151), whereas the frequency of regular forms in the other grammatical contexts under consideration ranges from 26.2 to 27.2%, as shown in Figure 3. Recall that because this is a balanced random sample, the overall prevalence of regularized forms may appear inflated. Nevertheless, Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of regular versus short-form forms across the grammatical contexts in the present data set, most notably highlighting the relative frequency of occurrence of each participle type across grammatical contexts.

Figure 3.

Participle types by grammatical context for verbs with short-form participles.

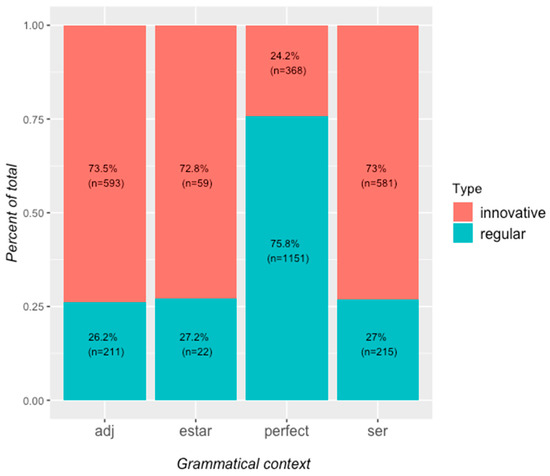

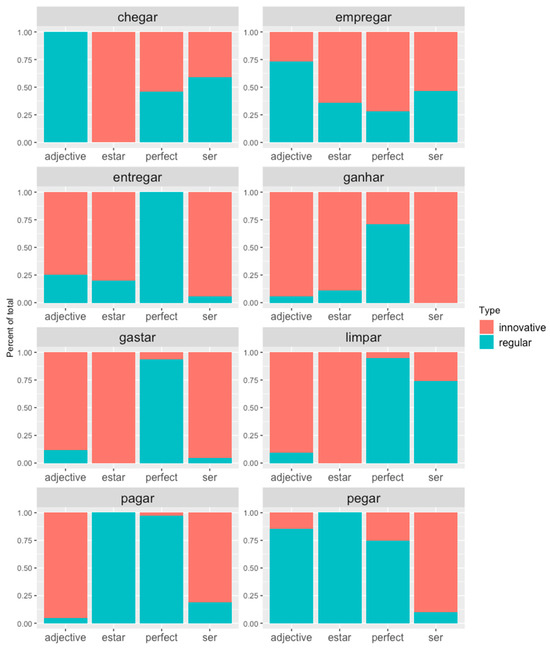

However, as in the previous data set, there was still variation between verbs. Figure 4 shows the distributions of regular and short-form participle types across grammatical functions for each verb. Interestingly, the most notable pattern in these data is the preference for the regular participle variant in perfect constructions, which is fairly consistent across verbs. Only 2/8 verbs, namely chegar (‘to arrive’) and empregar (‘to employ’), do not show a preference for the regular participle form in perfect constructions. Regarding adjectival contexts, all verbs except for chegar show a preference for the short-form variant. In constructions with estar, all verbs show greater rates of the short-form variant, except for pagar (‘to pay’) and pegar (‘to catch/get’). With ser, there is a great deal of variation between verbs, with overall rates of short-form vs. regular participles in this context showing the greatest variation between verbs of any of the grammatical contexts. Generally, most verbs show a preference for the short-form variant, but chegar (‘to arrive’) and limpar (‘to clean’) show more instantiations of the regular form. These differences between verbs suggest that while grammatical context plays an important role in this variation, there are undoubtedly other factors that influence these patterns. Future analysis will endeavor to examine more verbs in order to uncover additional motivating reasons for this variation.

Figure 4.

Distribution of participle types by context for verbs with short form.

4.2.2. Inferential Analysis of Short-Form Participles

The results from long-form Latinate participles, as well as the descriptive statistics provided in Section 4.2.1, highlight the potential for perfect constructions to be considered conditioning contexts for regular participles in BP. Therefore, the construction of models for the present data considered overall lexeme frequency as well as the contextual frequency of verb lexeme in perfect constructions as potential predictors of the use of regular participle forms. Following the described statistical procedure, the best-fit model for the data included grammatical context as a significant main effect and a significant interaction between grammatical context and verb frequency in perfect constructions8. The output of this model is shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Best fit logistic regression model output for short-form forms.

The output of this best-fit model highlights some compelling patterns related to short-form past participles by grammatical context. First, the output of this model shows that grammatical context is a statistically significant predictor of participle type. Specifically, short-form past participles are significantly less likely to occur in perfect constructions than they are to occur in all other grammatical contexts. Where the findings described in Section 4.1 showed that perfect constructions promote the regularization of long-form Latinate irregular past participles, these results show that perfect constructions also serve as conserving environments for regular participles that compete with short-form forms. This finding is yet another reinforcement of the strength of perfect constructions in BP as conditioning environments for regularity in the form of -ado/-ido participles.

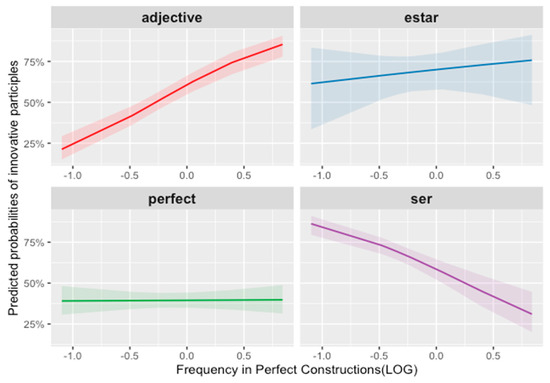

Second, the significant interaction between grammatical context and verb frequency in perfect constructions further emphasizes this conditioning. The output of this model shows that verbs that occur in perfect constructions, most frequently in the corpus as a whole, are more likely to show participle innovation as adjectives than in other grammatical contexts. This relationship is visualized in Figure 5. The x-axis shows the rate at which the verb lexeme associated with a given token occurs in perfect constructions in the corpus overall. In other words, this axis indicates the rate of co-occurrence of a participle with auxiliary ter or haver, with increasing co-occurrence from left to right. The y-axis shows the predicted probability of a short-form participle based on the best-fit model for these data.

Figure 5.

Predicted probabilities of short-form participles.

Examining this figure, we can see the effects of the significant interaction in the logistic regression model. First, this shows that the perfect constructions and contexts with estar are generally consistent in terms of the rates of short-form participles, independent of how often a particular verb lexeme occurs in perfect constructions in the corpus as a whole. Second, this figure shows the verbs that tend to occur more frequently in perfect constructions in the corpus were more likely to show short-form participles used as adjectives in the present data set. Third, ser shows an inverse relationship with adjectival contents, whereby verbs that occur more frequently in perfect constructions in the corpus as a whole are less likely to be realized as innovative variants with ser. These results show that although lexemes that are most strongly associated with perfect constructions in the corpus as a whole exhibit participle innovation, these short-form participles tend to be restricted to adjectival contexts.

4.3. Discussion

Two distinct trends emerge from these data for BP past participles. First, the participles for verbs with one long-form Latinate irregulars are conditioned by grammatical context, with the strongest conditioning environment for regularization being perfect constructions. Second, the degree of participle innovation is a product of both grammatical context and contextual frequency in perfect constructions. The common thread in both of these findings is that independent of the data set; there is a strong tendency towards the regular -ado/-ido participle forms in perfect constructions. In the case of long-form Latinate irregulars, this means that instantiations of regularized variants are more likely to appear in perfect constructions. In the case of short-form participles, this means that innovations are more likely to appear as adjectives and with ser or estar, while participles in perfect constructions are more likely to remain regular.

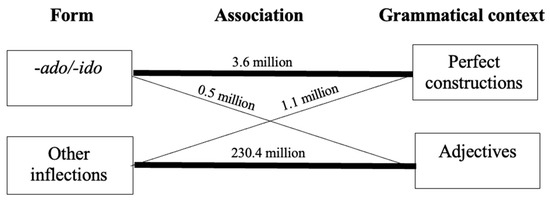

These trends can at least partially be explained by the paradigmatic regularity. Specifically, in the BP subset of the ptTenTen11 corpus, there are a total of 4.1 million instantiations of ter + past participle. Of these, 3.6 million (87.9%) end in -ado/-ido, providing evidence for a strong lexical association between perfect constructions and regularly formed past participles. Furthermore, of the 230.4 million adjectival tokens of Brazilian Portuguese in the PtTenTen11 corpus, only 1.1 million (0.5%) end in -ado/-ido. This comparison is illustrated in Figure 6. These findings also indicate that the contextual probability of a regular past participle after an instance of an auxiliary verb9 is also nearly 9 to 1 in BP.

Figure 6.

Form–function relationships of BP participle forms.

These findings align with previous work indicating that contextual probabilities are important predictors of lexical decisions (Baayen 2010) and provide additional evidence for the role of the strength of association between form and context in the development of grammatical constructions (Bybee 2013; Schmid 2015). The overall frequency with which auxiliary verbs and regular past participles are accessed together in BP, as illustrated by their high rate of co-occurrence in the corpus, heightens the possibility of analogical regularization due to the pressures of paradigmatic iconicity (Croft 2003, 2012) and contextual entrenchment (Schmid 2015).

These findings build on those laid out in previous work. First, these results align well with previous findings that regular past participles in Brazilian Portuguese are used in compound tenses, where innovative forms are used as adjectival complements (Cunha and Cintra 2016; Lobato 1999; Perini 2002; Villalva and Jardim 2018). Furthermore, these findings build on those of Schwenter et al. (2019), which showed that irregularity in Brazilian Portuguese past participles is highly lexically dependent. While a general correlation can be observed between the number of tokens in perfect constructions and the rate of innovation, there is still variation that cannot be explained via this mechanism. Observing Figure 1 above, the verb chegar shows the third-lowest rate of innovation in the data set but shows the overall highest number of tokens in the sample. While this could be a result of the overall frequency of chegar, it still indicates that there is some degree to which this variation is lexically constrained.

5. Conclusions

An important contribution of this analysis is the comparative examination of long-form Latinate irregulars and innovations rather than their treatment as a monolithic set of ‘irregulars’. This more fine-grained analysis shows that these two types of participles have overlapping yet distinct constraints on their use, which is critical for understanding how grammar–internal relationships between forms can influence use. Specifically, these findings highlight two distinct yet related effects of perfect constructions in BP. Namely, perfect constructions serve as a conditioning context promoting regularization in the case of long-form Latinate irregulars and serve as a conserving mechanism for regularity in the case of innovation, which can be attributed to the strength of association and frequency of occurrence between regular participle forms and perfect constructions. This analysis shows that these two types of participles have overlapping yet distinct constraints on their use, which is critical for understanding how grammar–internal relationships between forms can influence their usage patterns and highlights the role of the relationship between forms and contexts in language change. The present analyses not only provide insight into the synchronic variation of past participles in BP but also contribute to our understanding of the usage-based mechanisms of language variation and change.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the data collection methodology was based on the observation of public behavior. The information obtained is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that the identity of the human subjects cannot readily be ascertained, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects (Federal Code of Regulations Title 45, Subchapter A, Part 26, section (d)(2)(i)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived for this study because the data collection methodology was based on the observation of public behavior. The information obtained is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that the identity of the human subjects cannot readily be ascertained, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects (Federal Code of Regulations Title 45, Subchapter A, Part 26, section (d)(2)(i)).

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Full list of verbs considered for analysis, including token counts and usage distributions.

Table A1.

Full list of verbs considered for analysis, including token counts and usage distributions.

| Verb | Irregular Form | Total Irregular | Regularized Form | Total Regularized | Use across Contexts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abrir | aberto | 447,921 | abrido | 111 | variable |

| absolver | absolto | 31 | absolvido | 10,014 | variable |

| bendizer | bendito | 10,081 | bendizido | 1 | variable |

| benzer | bento | 2237 | benzido | 442 | variable |

| cobrir | coberto | 81,254 | cobrido | 41 | variable |

| contradizer | contradito | 553 | contradizido | 3 | variable |

| corromper | corrupto | 25,754 | corrompido | 8798 | variable |

| descobrer | descoberto | 61,744 | descobrido | 86 | variable |

| descrever | descrito | 111,788 | descrevido | 35 | variable |

| desenvolver | desenvolto | 685 | desenvolvido | 517,521 | variable |

| desfazer | desfeito | 8896 | desfazido | 1 | variable |

| despertar | desperto | 12,746 | despertado | 10,699 | variable |

| devolver | devolto | 0 | devolvido | 30,740 | no irreg. |

| dissolver | dissolto | 0 | dissolvido | 12,128 | no irreg. |

| dizer | dito | 217,670 | dizido | 33 | variable |

| eleger | eleito | 200,553 | elegido | 1072 | variable |

| envolver | envolto | 9514 | envolvido | 324,280 | variable |

| escrever | escrito | 425,412 | escrevido | 105 | variable |

| extinguir | extinto | 54,329 | extinguido | 667 | variable |

| fazer | feito | 1,997,297 | fazido | 32 | variable |

| fixar | fixo | 125,943 | fixado | 77,117 | categorical |

| fritar | frito | 17,060 | fritado | 544 | variable |

| imprimir | impresso | 96,505 | imprimido | 1654 | variable |

| inscrever | inscrito | 139,499 | inscrevido | 6 | variable |

| juntar | junto | 63,831 | juntado | 7834 | categorical |

| maldizer | maldito | 17,585 | maldizido | 3 | variable |

| morrer | morto | 183,516 | morrido | 15,348 | variable |

| possuir | posseso | 11 | possuído | 6481 | variable |

| predizer | predito | 1640 | predizido | 0 | no reg. |

| prover | provisto | 24 | provido | 16,180 | variable |

| recobrir | recoberto | 5247 | recobrido | 2 | variable |

| resolver | resolto | 6 | resolvido | 91,165 | variable |

| revolver | revolto | 6431 | revolvido | 595 | variable |

| romper | roto | 3749 | rompido | 10,053 | variable |

| satisfazer | satisfeito | 103,785 | satisfazido | 2 | variable |

| soltar | solto | 59,925 | soltado | 1145 | variable |

| transcrever | transcrito | 12,898 | transcribido | 2 | variable |

| ver | veido | 28 | visto | 445,431 | variable |

| voltar | volto | 9 | voltado | 323,281 | variable |

Notes

| 1 | Importantly, uses of participle forms with ser may correspond to different structures. Specifically, they can be used adjectivally (e.g., As comidas são feitas de milho ‘The foods are made with corn’), as well as in passive constructions (e.g., A comida foi feita pela cozinheira ‘The food was prepared by the cook’). Though there are potentially important semantic differences in these uses, the present analysis groups them together as uses with ser, in order to provide initial analysis of the role of grammatical context. Nevertheless, future analysis will endeavor to analyze potential distinctions between the two usage types. |

| 2 | In the present work, ‘Latinate’ is used as an umbrella term to refer to participles whose irregularity can be traced to influence from forms in Classical Latin. These are to be distinguished from other irregular participle forms which arose as innovations via other historical processes. |

| 3 | Interestingly, Schwenter et al. (2019) found greater use of short-form forms in European Portuguese as compared to Brazilian Portuguese. Though of great interest, this is beyond the scope of the present analysis. |

| 4 | There are different grammatical constructions with ter and participle forms. For example, the participle form can be part of a perfect construction like the Pretérito Perfeito Composto (tenho preparado a comida ‘I have prepared the food’), or function as an adjective as in tenho a comida preparada (‘I have a prepared food’). In the present data, instances of the first case were coded as perfect constructions with ter, while instances of the second were coded as adjectives modifying nouns. |

| 5 | The corpus data for long-form Latinate irregulars does not indicate a linear relationship between verb frequency and relative frequency of regularized past participles. Unexpectedly, results of a two-tailed t-test show a significant direct positive relationship between verb frequency and the relative frequency of regularized participles for these 35 verbs that show variation (t = 6.151, df = 34, p-value = 5.487 × 10−7). However, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient for these measures, which indicates the strength of association between the two continuous variables, shows only a very slight, if not negligible positive correlation (r = 0.01). |

| 6 | Though verb lexeme frequency in all grammatical contexts under analysis was calculated and taken into consideration in all statistical models, a significant contextual effect was seen only with regard to frequency in perfect constructions for short-form participles. |

| 7 | It is important to acknowledge that the data that comprise this corpus are from 2011, and it is likely that there have been changes since that time, in particular, on social media and other informal written genres. After the analysis of these data, Sketch Engine published a newer Portuguese copora (ptTenTen18 and ptTenTen20). This work represents only a preliminary view of this type of variation in Brazilian Portuguese past participles in the ptTenTen11 corpus and will continue to be developed. |

| 8 | Overall lexeme frequency was also considered as a potential predictor of degree of participle innovation, but was not found to be a statistically significant independent variable for these data and was not included in the best-fit model. |

| 9 | Due to the limitations on the current data set, teasing apart potential differences in participle selection between ter and haver was not possible, and most of the tokens occur with the former. Future research will endeavor to explore the the degree to which haver participates in regular perfect constructions as compared to ter. |

References

- Anttila, Raimo. 1977. Analogy. New York: Mouton Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Baayen, R. Harold. 2010. Demythologizing the word frequency effect: A discriminative learning perspective. The Mental Lexicon 5: 436–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Maechler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, James P., and Juliette Blevins. 2009. Introduction: Analogy in grammar. In Analogy in Grammar: Form and Acquisition. Edited by James P. Blevins and Juliette Blevins. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 1985. Morphology: A Study of the Relation between Meaning and Form. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 1995. Regular morphology and the lexicon. Language and Cognitive Processes 10: 425–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan. 2002. Word frequency and context of use in the lexical diffusion of phonetically conditioned sound change. Language Variation and Change 14: 261–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan. 2003. Mechanisms of change in grammaticization: The role of frequency. In The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Edited by Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 602–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2006. From usage to grammar: The mind’s response to repetition. Language 82: 711–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan. 2010. Language, Usage and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2013. Usage-based theory and exemplar representations of constructions. In The Oxford Handbook of Construction Grammar. Edited by Thomas Hoffman and Graeme Trousdale. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan, and Clay Beckner. 2010. Usage-based theory. In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis. Edited by Bernd Heine and Heiko Narrog. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 953–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas de Souza, Paulo. 2007. Athematic participles in Brazilian Portuguese: A syncretism in the making. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 54: 119–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas de Souza, Paulo. 2011. Particípios atemáticos no PB: Um processo paradigmático. ReVEL 5: 176–85. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, William. 2003. Typology and Universals, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, William. 2012. Verbs: Aspect and Causal Structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, Celso, and Lindley Cintra. 2016. Nova Gramática do Português Contemporâneo. Rio de Janeiro: Lexicon Editora Digital. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Mark. 2004. Corpus do Português: Genre/Historical (Corpus). Available online: https://www.corpusdoportugues.org/hist-gen/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Fox, John, and Sanford Weisberg. 2018. An R Companion to Applied Regression. California: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hock, Hans Henrich. 1991. Principles of Historical Linguistics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul J. 1987. Emergent grammar. Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 13: 139–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hricsina, Jan. 2019. The Periphrasis Formed by the Verb ir + Infinitive in the History of the Portuguese language. Etudes Romanes de Brno 40: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Joseph. 1933. Altportugiesisches Elementarbuch. Heidelberg: Carl Winters Universitätsbuchhandlung, (Portuguese translation Gramática do Português Antigo. Traslated by Maria Manuela Delille. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1986). [Google Scholar]

- Kilgarriff, Adam, Miloš Jakubíček, Jan Pomikalek, Tony Berber Sardinha, and Pete Whitelock. 2014. PtTenTen: A corpus for Portuguese lexicography. In Working with Portuguese Corpora. Bloomsbury: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 111–30. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 1987. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar: Theoretical Prerequisites. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, Richard. 1999. Past Participles from Latin to Romance. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw, Andy, and Matthew Wiener. 2002. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News 2: 18–22. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/doc/Rnews/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Lobato, Lucia. 1999. Sobre a forma do particípio do português e o estatuto dos traços formais. DELTA: Documentação de Estudos em Lingüística Teórica e Aplicada 15: 113–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 1978. The acquisition of morphophonology. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 43: 1–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miara, Fernanda Lima Jardim, and Izete Lehmkuhl Coelho. 2015. Particípios duplos: Norma, avaliação e uso escrito. Cadernos de Letras da UFF 25: 217–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, Gordon, Michael Stack, Igor Rnitovic, Dan Avery, and Michele Kimpton. 2004. An Introduction to Heritrix. Paper presented at 4th International Web Archiving Workshop, Bath, UK, September 16; pp. 109–15. [Google Scholar]

- Padró, Lluís, Miquel Collado, Samuel Reese, Marina Lloberes, and Irene Castellon. 2010. Freeling 2.1: Five years of open-source language processing tools. Paper presented at 7th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Valletta, Malta, May 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Perini, Mário. 2002. Modern Portuguese: A Reference Grammar. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2022. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Software. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Schmid, Hans-Jörg. 2015. A blueprint of the entrenchment-and-conventionalization model. Yearbook of the German Cognitive Linguistics Association 3: 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenter, Scott A., Mark Hoff, Eleni Christodulelis, Chelsea Pflum, and Ashlee Dauphinais. 2019. Variable past participles in Portuguese perfect constructions. Language Variation and Change 31: 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalva, Alina, and Fernanda Jardim. 2018. Particípios atemáticos no Português: Tipologia, distribuição e avaliação. Estudios de Lingüística del Español 39: 279–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queriquelli, Luiz Henrique Milani. 2018. Os particípios rizotônicos emergentes no português brasileiro e sua gênese histórica. Filologia e Linguística Portuguesa 20: 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Edwin B. 2016. From Latin to Portuguese: Historical Phonology and Morphology of the Portuguese Language. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).