Abstract

This paper aims to provide a clearer understanding of the structure known in the literature as the innovative use of estar, illustrated in sentences like Luego salgo/voy a visitar usuarios que están muy morosos [Medellín, Colombia; Preseea] (“Today I am going to visit users that are.ESTAR defaulting debtors”). In such sentences, no comparison is established between stages or counterparts of the subject of predication with regard to the property expressed by the adjective, as opposed to estar-sentences in standard/general Spanish. This innovative structure is a syntactic scheme employed throughout different Latin American Spanish varieties. The goal of this paper is twofold: it is both descriptive and theoretical. From a descriptive perspective, it offers an exhaustive and updated empirical characterization of the extent of this structure in Latin American Spanish based on an analysis of the Preseea corpus. This description takes into consideration both its geographical distribution in the different Latin American dialectal varieties and the lexical–syntactic classes of adjectives that appear as predicates in innovative estar-sentences. Building on this, from a theoretical point of view, a critical evaluation is made of the existing proposals in the literature that explain the properties—both syntactic and semantic—of the innovative construction.

1. Introduction

In this paper, we focus on the structure known in the literature as the innovative use of estar (Silva-Corvalán 1986), illustrated in the following example from Mexican Spanish: E: ¿Y cómo era la fábrica? ¿estaba grande? I: Estaba grande, sí, estaba grande (“And what was.SER the factory like? Was.ESTAR it big? I: Yes, it was.ESTAR big.”, Mexico, MONR_M21_044, Preseea; all the examples in this article have been extracted from the Preseea corpus). The innovative use of estar is a syntactic pattern that is widely attested in Latin American Spanish and is considered by Malaver (2009, p. 97) as a syntactic Americanism: a syntactic schema that can be found in the speech of urban areas in at least two or more Latin American countries (according to Company’s 2006, 26 definition). As a descriptive label, we will call the geolectal varieties where this structure is possible innovative varieties.

In innovative estar-structures, no comparison is established between stages or counterparts of the subject of predication with regards to the property expressed by the adjective following the copula. In this sense, innovative structures are different from general or standard1 copular sentences with estar, as is illustrated in: Han reformado la fábrica, y ahora está muy grande, muy espaciosa (“The factory has been renovated and is.ESTAR now very big, very spacious”), where two temporal stages of the subject la fábrica “the factory” are compared regarding size. Several authors (Gutiérrez 1994, a.o.) have noticed that the crucial aspect of the meaning of innovative estar-structures is to express the subjective point of view of the speaker about the attribution of a particular quality to an entity.

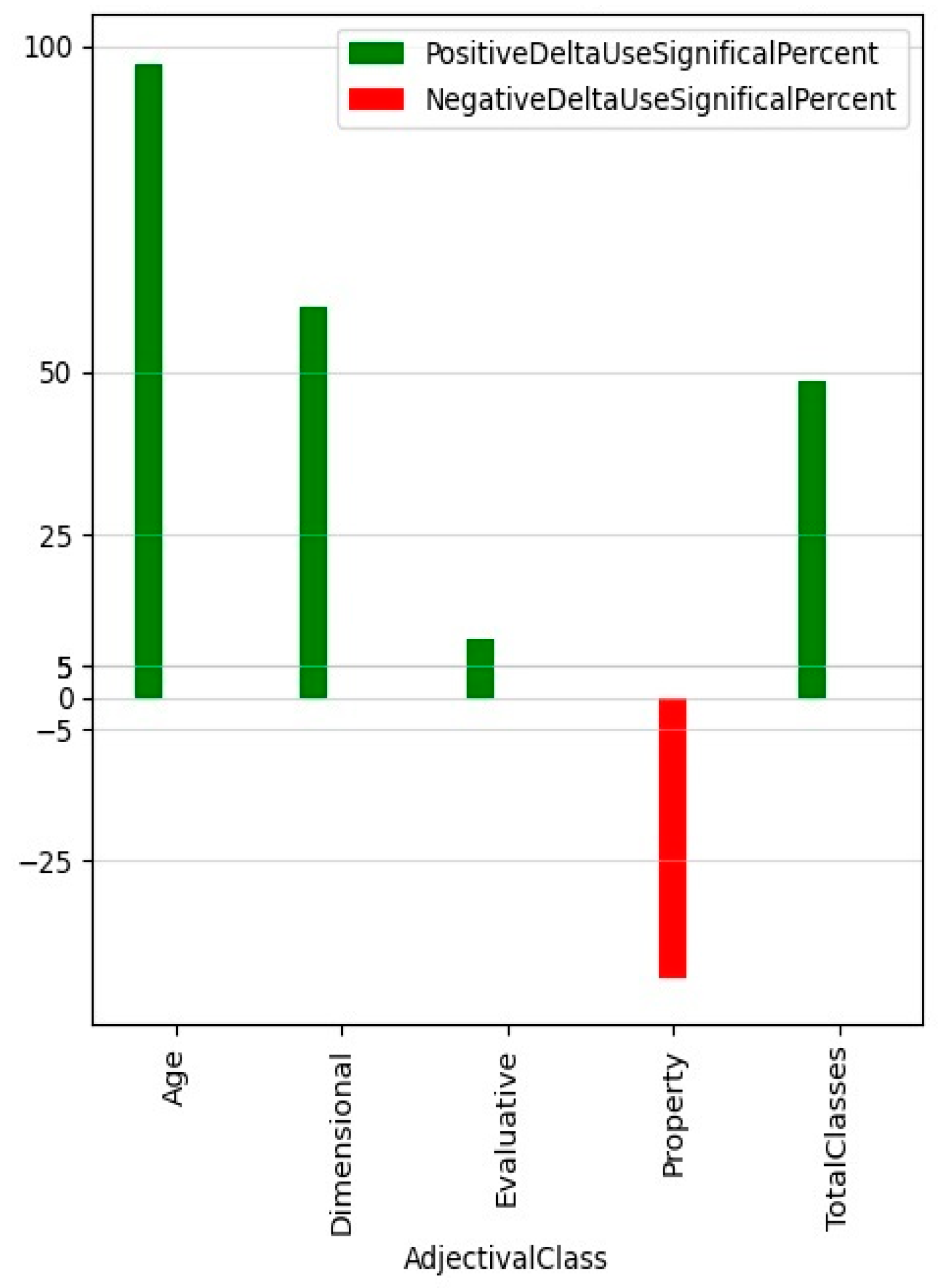

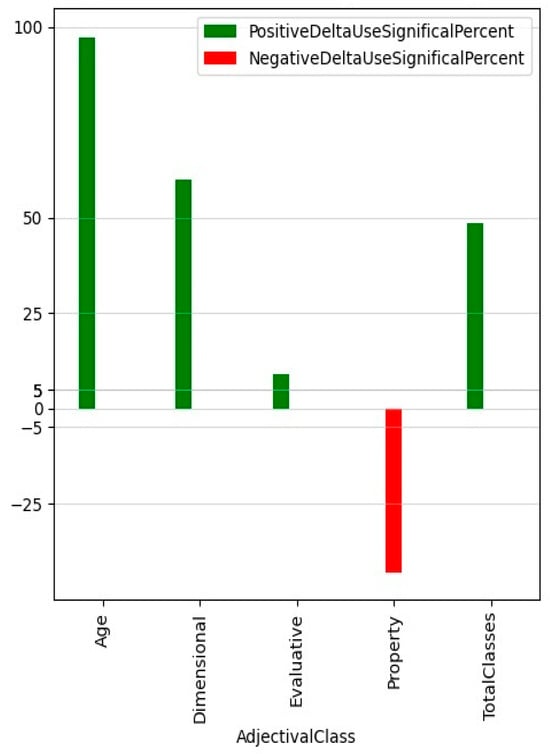

Most of the studies that analyze innovative estar-sentences in different varieties of Spanish explain their existence as the result of the modification of some semantic properties of the copula estar of general Spanish, or as linked to the generalization of pragmatic mechanisms that apply in a more restricted way in copular sentences in general Spanish. Against this type of proposals, focused on the semantic–pragmatic properties of estar in innovative varieties, Gumiel-Molina et al. (2020) and Moreno-Quibén (2022) argue that the lexical–syntactic properties of adjectives are crucial to understanding this pattern of syntactic variation. In this context, the aim of this paper is twofold: (a) to demonstrate that the lexical–syntactic classes to which adjectives belong are relevant to understanding the syntactic and semantic properties of the innovative estar-construction as well as its geographical distribution across Latin American Spanish varieties, and (b) to explore the theoretical consequences of this fact. Thus, to affirm the relevance of the lexical–syntactic classes of adjectives to explain the differences between the general/standard copular structures and the innovative estar-sentences, we offer an exhaustive and updated characterization of the extent of this structure in Latin American Spanish, considering both its geographical distribution in the different American dialectal varieties and the lexical–syntactic classes of adjectives that appear as predicates in innovative estar-sentences. Our study will be based on an empirical analysis of the Preseea corpus. We conclude that there is a significant difference in the occurrence of the various lexical–syntactic classes of adjectives in the innovative estar-construction both within each dialectal area and across dialectal areas of Latin American Spanish. From a theoretical perspective, in light of the generalizations established, a critical evaluation will be made of the existing proposals in the literature that explain the existence and properties—both syntactic and semantic—of the innovative structure. We claim that only those proposals that consider the lexical–syntactic properties of adjectives as subject to dialectal variation can account for the paradigm described.

In order to achieve these goals, this article first goes on to address the pertinent literature to establish the theoretical framework in which the study has been undertaken. Key terms such as general/standard and innovative use of estar-sentences (estar+ Adjectival Phrase) are also defined. This subsequent section also addresses a literature review that examines the dialectal distribution of innovative use and its grammatical properties. In Section 3, the methodological underpinnings of the present study are presented. In Section 4, the results are presented in relation to the key parameters under investigation, i.e., geographical distribution and lexical–syntactic classes of adjectives. In Section 5, the results are discussed and statistically supported. In Section 6, the proposals made in the related literature to explain the use of estar are revisited as a means of discussing their adequacy to explain the general trends highlighted in the previous section. In Section 7, the final conclusions drawn are presented.

2. The Distribution of <ser/estar + Adjectival Phrase> across Spanish Varieties. General/Standard and Innovative Uses

As has long been established, general Spanish or standard Spanish has two copular verbs, which can be combined with adjectival predicates: ser “be.SER” and estar “be.ESTAR”. In Section 2.1 we describe the combination patterns of the copulas ser and estar with adjectival predicates characteristic of general/standard Spanish. In Section 2.2 we describe the innovative use of <estar + Adjectival Phrase>. We will base our description on the lexical–semantic–syntactic classes of adjectives established in Demonte (1999a, 1999b, 2011), apud Dixon (1982):

- Qualifying adjectives: the following subclasses have been considered:

- (a)

- Dimensional adjectives: adjectives expressing dimensional properties of entities such as length, height, width, thickness, etc., excluding age (alto “tall”, ancho, “wide”, grueso “thick”, largo “long”, etc.). Dimensional adjectives take measure phrases (5 metros de largo “5 m long”).

- (b)

- Age adjectives: express the chronological age of an animate entity (chavo “little”, joven “young”, pequeño “little”, viejo “old”, etc.).

- (c)

- Property adjectives: non-dimensional adjectives expressing physical or abstract properties of entities (duro “hard”, triste “sad” …—in this paper, subclasses of property adjectives will not be considered, although emotional adjectives also have an evaluative component). Adjectives expressing degrees of price or temperature were included in this class (barato “cheap”, costoso “expensive”, caliente “hot”, etc.).

- (d)

- Color adjectives (blanco “white”, negro “black”, etc.).

- (e)

- Evaluative adjectives: macro-class that includes various subclasses with different syntactic–semantic properties (Demonte 1999a, 1999b, 2011; McNally and Stojanovic 2015; Liao et al. 2016; Moreno-Quibén 2022; Gumiel-Molina et al. 2023). Evaluative adjectives give rise to scalar variation.

- Extreme-degree adjectives (bárbaro “awesome”, terrible “horrible”), which express a very high positive or negative general evaluation of an entity, not necessarily linked to a specific parameter (vs. the following subclasses).

- Aesthetic adjectives (bello “beautiful”, guapo “handsome”, lindo “cute, beautiful“…), which express the aesthetic value of an entity.

- Predicates of personal taste (sabroso, rico “tasty” …), which express evaluation involving direct physical contact with the entity expressed by the subject of predication (i.e., through smelling, eating, or drinking).

- Predicates of personal judgment (difícil “difficult”), which express evaluation of entities not involving physical contact.

- “Other”: This class accommodates other evaluative adjectives that do not fit neatly into the above classes because of their meaning or syntactic behavior. Many of the adjectives grouped in this heterogeneous class only co-occur with ser in copulative sentences in general Spanish (e.g., conflictivo “conflictive”, significativo “significant”, importante “important”, recto “upright”—which is a moral predicate in the sense of Stojanovic and McNally (2022).

- Relational, circumstance or adverbial and modal adjectives.As Demonte (1999b) points out, some adjectives in these classes can be used as predicates: El queso brie es francés “Brie cheese is.SER French”; Esa publicación no es periódica “This publication is.SER not a regular one”; La victoria es posible “Victory is.SER possible”. They are combined with ser in general Spanish. See also RAE-ASALE (2009, p. 37.9b,c).

2.1. <ser/estar + Adjectival Phrase> in General/Standard Spanish

Qualifying adjectives can generally be combined with both copulas, as is illustrated below (1).

| (1) | a. | Físicamente | mi | esposo | es | gordito, | es | alto |

| physically | my | husband | is.SER | chubby | is.SER | tall | ||

| Physically, my husband is chubby, he’s tall. (Colombia, CALI_M21_041) | ||||||||

| b. | Ella | está | desarrollando | y | está | alta | ||

| she | is.ESTAR | developing | and | is.ESTAR | tall | |||

| She is growing and is tall (now). (Cuba, LHAB_M22_055) | ||||||||

To explain the difference between the copular structures (1a) and (1b), all the existing proposals have resorted in one way or another to the distinction between individual and stage-level predications, regardless of the theoretical implementation of this difference (this is, in fact, the distinction used in contemporary traditional grammar to explain the differences between copulative sentences with ser and with estar, cf. RAE-ASALE 2009, p. 37.7; see also Marín 2004, 2016, for a description of the general/standard use of the Spanish copulas within an aspectual approach). Theoretical proposals based on modes of comparison, such as the one developed by Gumiel-Molina et al. (2015a, 2015b), argue that the attribution of a gradable property to an entity in a copular sentence is always based on a (implicit or explicit) comparison to other entities (see also Crespo 1946; Bolinger 1947; Roldán 1974; Falk 1979; Franco and Steinmetz 1983, 1986; Bazaco 2017; Sánchez-Alonso 2018).

According to Gumiel-Molina et al. (2015a), the sentences in (1a) and (1b) differ in the class of semantic entities regarding which the comparison is made (comparison class). With ser, (1a), the comparison class consists of other individuals with which the referent of the subject (mi esposo, “my husband”) shares some characteristic (e.g., being a 40-year-old man); thus, (1a) is true if the subject exceeds the average height calculated for that class (comparison between individuals X-Y). In contrast, with estar, (1b), the comparison class refers to alternative counterparts/stages of the subject; thus, (1b) could be true or false depending on the comparison of the stage s of the subject with a degree Xn of the property at the time of assertion with a previous or alternative (non-factual) stage s’ of the same individual with a degree Xj of the property (comparison within the individual Xn-Xj).

This type of proposal explains the systematic difference in meaning found in general Spanish between ser- and estar-sentences when qualifying adjectives appear as predicates (c.f. Gumiel-Molina et al. 2021, Section 4.2.3 for some apparent exceptions to this generalization). Furthermore, it explains that participial and perfective adjectives combine only with estar (Juan está harto/borrracho “Juan is.ESTAR fed up/drunk”). This is because they lexically express a state resulting from a previous event affecting the subject of the predication so that counterparts of the subject must be necessarily taken into account in order to consider the sentence true or false. Also, non-qualifying adjectives used as predicates combine with ser, for instance, relational adjectives, adverbial adjectives, etc., e.g., El pasaporte es italiano “The passport is.SER Italian”; La revista es seminal, “The magazine is.SER weekly”, since they are sortal predicates that express a defining property, i.e., a property salient enough to define an individual as a particular member of a class (c.f. Gumiel-Molina et al. 2015a; Roy 2013). This is also the case with modal adjectives like posible “possible” and evidente “evident” (RAE-ASALE 2009, p. 379b, c)

Although the combination of most qualifying adjectives (dimensional adjectives –alto “tall”, delgado “thin”–, property adjectives including dispositional ones –triste “sad”, blando “soft”, generoso “generous”–, color adjectives –blanco “white”–, etc., cf. RAE-ASALE 2009, p. 37.9d, f, l) with ser and estar obeys the systematic pattern of meaning alternation that has just been described, some clarifications should be added in relation to age adjectives and evaluative adjectives.

2.1.1. Age Adjectives

The combination of age adjectives with ser and estar in Spanish is complex and has not been fully explained in the literature, to the best of our knowledge. Descriptively speaking, as stated in RAE-ASALE (2009, p. 37.9t), in general/standard Spanish, these adjectives combine with ser to express chronological age: En su carnet pone que tiene 16/103 años, así que es joven/viejo “His ID card says he is 16/103 years old, so he is.SER young/old”. When combined with estar, they express some property associated with age. A sentence like Juan tiene 50 años pero está mayor/viejo “Juan is 50 years old but looks older, Lit. is.ESTAR old”, expresses clumsiness or physical weakness, slowness or lack of reflexes, or aged appearance. Similarly, Juan tiene cincuenta años pero está mayor/joven para escalar “Juan is fifty years old but is.ESTAR (too) old/young to climb”, expresses age (in)adequacy to perform an action. Considering this description of the standard/general combination of age adjectives with estar, other possible patterns departing from it will be considered as innovative uses, as in the following examples Yo tenía seis años, P. habrá tenido cuatro, o sea, estaba chiquito (“I was six years old, P. must have been four, I mean, he was a little kid”, Lit. he was.ESTAR little”; Perú, LIMA_M23_042); [Speaking of the birth of their children] porque recuérdate que el otro nació cuando nosotros estábamos grandes (“Because remember that the other one was born when we were.ESTAR grown up” Lit. “…we were.ESTAR big”, Venezuela, CARA_M33_103). In these examples, the predicate of the estar-sentence is an age adjective (chiquito, grande) exclusively expressing chronological age.

2.1.2. Evaluative Adjectives

Evaluative adjectives form a macro-class whose subclasses behave differently in combination with ser and estar in standard Spanish. Evaluative aesthetic adjectives give rise to the general contrast between ser- and estar-sentences: Ana es hermosa (“Ana is.SER beautiful”); Ana estaba hermosa ayer en la boda (“Ana was.ESTAR beautiful yesterday at the wedding) (cf. RAE-ASALE 2009, p. 37.7c).

However, some evaluative adjectives also give rise to a judge-oriented reading in general Spanish. This is the case with predicates of personal taste, (2) (rico, sabroso “tasty”). In this example, there is no comparison between counterparts of the subject of predication regarding the property expressed by the adjective. However, this sentence does express a comparison within an individual. As claimed recurrently in the literature, these evaluative adjectives have an experiencer argument as part of their argument structure, which may be syntactically implicit or explicit: rico para X, “tasty for X” (Lasersohn 2011, 2012; Pearson 2013; Bylinina 2014, 2017). Gumiel-Molina et al. (2020, 2023) and Moreno-Quibén (2022) claim that this argument provides the necessary counterparts to form the within-the-individual comparison class in estar-sentences. The comparison is thus established between the evaluation of the property that the experiencer makes in the sentence evaluation index and an alternative evaluation that a counterpart of the experiencer might make in a different evaluation index. Given that the experiencer is by default coindexed with the speaker, the sentence expresses a perspectivized assertion, a subjective judgment of the speaker expressing his or her point of view on the attribution of the property. Examples like (2) below are dubbed in the literature as evidential estar-sentences (Franco and Steinmetz 1983; Roby 2009); this label is compatible with the explanation just outlined if it is assumed that adjectives of personal taste require that the experiencer has an experiential contact with the entity to which the subject refers.

| (2) | ese | [queso] | está | muy | rico | ||

| that | chesse | isESTAR | very | tasty | |||

| That cheese is really tasty. (México, MONR_M12_022) | |||||||

Predicates of personal judgment (fácil “easy”, difícil “difficult”, divertido “fun”, etc.) also have an experiencer/judge2 argument—fácil/difícil/divertido para X—(Hartman 2011, 2012; Bylinina 2014, 2017; McNally and Stojanovic 2015) and show a similar reading in estar-sentences, (3). In (3), the subject expresses a situation in which the experiencer/judge participates (Franco and Steinmetz 1983; Roby 2009).

| (3) | a. [Context: Speaking of the impossibility of finding a job] | |||||||

| E: en | cualquier | lugar | encuentras | trabajo (…) | ||||

| in | any | place | find.2.SG.PRES | job | ||||

| I: pues no/ | no | está | fácil | |||||

| well, no | not | is.3.SG.ESTAR | easy | |||||

| You can find a job anywhere? no, it is not easy [to find a job]. (México, MEXI_H21_090) | ||||||||

| b. [Context: Talking about Christmas plans] | ||||||||

| debe | de | estar | re divertido | salir | un veinticuatro | |||

| must | of | be.ESTAR | super fun | going out | on 24th [December] | |||

| It must be fun going out on Christmas Eve. (Uruguay, MONV_M12_020) | ||||||||

However, the behavior of personal judgment adjectives in ser/estar sentences is complex, in ways unexplored in the literature. First, some lexical items cannot be combined with estar in at least some varieties, for example Peninsular Spanish: Realizar aquel encargo fue/*estuvo duro “Carrying out that task was.SER/*ESTAR hard”, Escuchar sus palabras fue/*estuvo muy fuerte “Listening to his words was.SER/*ESTAR really hard”. Second, for other lexical items in this class, the combination with the copula interferes with tough-movement, and there are grammaticality differences between the variants with and without tough-movement: Construir aquel muro estuvo (fácil/divertido/complicado/interesante/??/*sencillo) “Building that wall was.ESTAR easy, fun, complicated, interesting, ??/* simple”, ??/*Aquel muro estuvo fácil/divertido/complicado/interesante/sencillo de construir “That wall was.ESTAR easy, fun, complicated, interesting, simple to build” (sentences with ser are grammatical in both cases). In this article, we will not attempt to explain this behavior; suffice it to say that, as we will see below, Spanish varieties differ as to the classes of subjects that are accepted in estar sentences with predicates of personal judgment.

Finally, extreme-degree adjectives (maravilloso “awesome”, espectacular “spectacular”) have also been claimed to have an experiencer/judge argument that provides counterparts to form a within-an-individual comparison class in estar-sentences (Bylinina 2014, 2017). In (4a), the subject takes part in a structured event (a show) in which the experiencer/judge has a certain role (viewer). In (4b), the subject expresses a situation in which the experiencer/judge participates. Other similar examples (with structured events as subjects) are La fiesta estuvo fantástica “The party was.ESTAR fantastic” and La boda estuvo horrible “The wedding was.ESTAR awful” (cf. Gumiel-Molina et al. 2015a; RAE-ASALE 2009, p. 37.9d). Also, in these cases, the comparison is established between the evaluation of the property that the experiencer/judge makes regarding the entity in the sentence evaluation index and an alternative evaluation that a counterpart of the experiencer/judge might make in a different evaluation index. It must be acknowledged that the kinds of semantic entities that can appear as subjects in these sentences are complex and will not be dealt with in this paper; see Escribano Roca (2023) for further information on this topic.

| (4) | a. [Context: Talking about a just-released show] | |||||||

| el | cuerpo | de | baile | estaba | espectacular | |||

| the | corps | de | ballet | was.3.SG.ESTAR | spectacular | |||

| The corps de ballet was spectacular. (Cuba, LHAB_M13_079) | ||||||||

| b. E: aprendés bastante porque //te enseñan a a construir tu propia casa ah (…) | ||||||||

| E: you learn a lot because//they teach you how to build your own house ah | ||||||||

| I: claro | está | bárbaro | está | genial | eso | |||

| I: of course | is.3.SG.ESTAR | awesome | is.3.SG.ESTAR | cool | that | |||

| Of course, it [learning how to build your own house] is awesome, it is cool (Uruguay, MONV_H11_035) | ||||||||

2.2. Innovative <Estar + Adjectival Phrase>

It is important to note that the consideration of an example as general/standard or as innovative is based on the compositional meaning of the structure estar + AP, and not on the lexical choice of the adjective, which can be restricted to a specific variety. For example, the adjective padre (“very good, very funny, of good quality”, Diccionario del español de México, COLMEX, https://dem.colmex.mx/, accessed on 16 August 2023) is restricted to Mexico, but an example such as the following illustrates the general/standard use of estar-sentences, parallel to (4): …y me gusta porque, no sé, es verano y el clima está súper padre “…and I like it because, I don’t know, it’s summer and the weather is.ESTAR really cool” (México, MXLI_M13_029). Similarly, the adjective patuleco is restricted to some American varieties with the meaning of “(applied to people) person who limps or walks defectively”. However, the following example must be considered as part of general/standard Spanish since counterparts of the subject of predication are compared with the property in question: Últimamente, como yo estoy media patuleca y… no ando <observacion_complementaria=“se refiere a su pérdida de agilidad producto de la edad”> “Lately, as I’ve been a bit clumsy and… I don’t walk <supplementary_observation=“refers to her loss of agility due to age”>“ (Chile, SCHI_M33_103). The innovative use of estar must be considered a case of syntactic variation, regardless of whether adjectival predicates are subject also to lexical variation.

In this work, when referring to the innovative use of estar or innovative estar-sentences, we refer to structures like those exemplified in (5) and (6) below, which differ in their semantic and grammatical properties from those described in Section 2.1 as part of general/standard Spanish.

| (5) | E: ¿Y | cómo | era | la | fábrica? | ¿Estaba | grande? |

| and | how | was. 3.SG.SER | the | factory? | was.3.SG.ESTAR | big? | |

| I: Estaba | grande, | sí | estaba | grande | |||

| was.3.SG.ESTAR | big | yes | was. 3.SG..ESTAR | big | |||

| E: And what was the factory like? Was it big?, I: It was big, yes, it was big. (México MONR_M21_044) | |||||||

| (6) | luego | salgo/ | voy | a | visitar | usuarios | que | están |

| then | go-out.1.SG | go.1.SG | to | visit | users | that | are.3.PL.ESTAR | |

| muy | morosos/ | voy a | hacer | cobros | (note) | |||

| very | defaulting.MASC.PL | go to | make | collections | ||||

| Today I am going out; I am going to visit users who are defaulting debtors; I am going to collect invoices. (MEDE_H22_002, Medellín, Colombia) | ||||||||

For example, in (5), a stage of the factory is not compared with alternative, previous or possible, stages of the factory regarding the property expressed by the dimensional adjective (size adjective), contrary to what happens in an example like (1b). In addition, this kind of adjective lacks, in general Spanish, an experiencer/judge argument that could provide counterparts to form a comparison within the individual, as would be the case with evaluative adjectives. Similarly, in (6) the sentence does not express a comparison of stages of the subject of predication with regards to the property denoted by the property adjective. Since moroso “defaulting (debtor)” is not an evaluative adjective (and thus lacks an experiencer argument), a meaning parallel to the one obtained in (2)–(4) is not possible in general/standard Spanish. Therefore, (5) and (6) are examples illustrating the innovative use of estar-sentences (these examples are judged as ungrammatical in Peninsular Spanish).

The main semantic characteristic of these structures is that they present the attribution of the property to the subject as a subjective judgment of the speaker, expressing his or her point of view on the predication at the time of assertion (Gutiérrez 1994; García-Márkina 2013; Sánchez-Alonso et al. 2016; Sánchez-Alonso 2018; Gumiel-Molina et al. 2020, 2023; Moreno-Quibén 2022).3

As it has been pointed out in different works (Gutiérrez 1992; De Jonge 1993a, 1993b; Ortiz-López 2000; Cortés-Torres 2004; Malaver 2009, 2012a, 2012b; Díaz-Campos and Geeslin 2011; Alfaraz 2012; Brown and Cortés-Torres 2012; Juárez-Cummings 2014; García-Márkina 2013; Sánchez-Alonso 2018; Sánchez-Alonso et al. 2016, 2019; Moreno-Quibén 2022; Gumiel-Molina et al. 2020, 2023), the extension of the innovative structure with estar differs in the distinct varieties of Spanish both from a geographical distribution perspective and in terms of the kinds of adjectival predicates that appear in it. On the one hand, innovative estar-sentences have been documented systematically in Mexican Spanish, and less systematically in the varieties spoken in Guatemala, Venezuela, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Costa Rica and Peru. It is not attested in the Rioplatense area (nor in European Spanish, although Malaver 2009 provides examples of the Andalusian variety).

On the other hand, it has been observed that not all lexical–syntactic classes of adjectives appear in the innovative structure. For instance, Gutiérrez (1994), Cortés-Torres (2004) and García-Márkina (2013) point to the existence of the following hierarchy in the frequency of appearance of the lexical–syntactic classes of adjectives in the innovative estar-structure in Mexican Spanish: age adjectives (joven, chiquito “young”) > size adjectives (grande “big”) > evaluative adjectives expressing beauty (aesthetic predicates, guapo “handsome”, lindo, bello “beautiful”).

However, there is certain inconsistency regarding other lexical classes of adjectives in the innovative structure, namely non-dimensional adjectives expressing physical properties, or they are unattested, e.g., color adjectives. Similar generalizations are established in Ortiz-López (2000) and Brown and Cortés-Torres (2012) for Puerto Rican Spanish and in Alfaraz (2012) for Cuban Spanish. Moreno-Quibén (2022, chp. 4) reaches similar conclusions from an analysis of the Preseea corpus based on the analysis of a predetermined list of adjectives belonging to different lexical–syntactic classes in copular estar-sentences. Highlighting an intuitive generalization, Gutiérrez (1994, p. 79) pointed out that the adjectives that appear preferentially in the innovative construction are those that express properties for whose attribution the speaker has the norm of evaluation.

In this context, as outlined in the introduction, the descriptive aim of this article is to offer an exhaustive and updated characterization of the extent of the innovative estar-structure in Latin American Spanish, considering simultaneously both its geographical distribution in the different dialectal varieties and the lexical–syntactic classes of adjectives that appear in it. To this end, an empirical study has been carried out based on the Preseea corpus as is described in the following section.

3. Methodology of the Corpus Study

To characterize the extent of the innovative estar-structure in American Spanish with a focus on the distribution of different lexical–syntactic classes of adjectives, a database based on Preseea was compiled. Preseea is a corpus of spoken Spanish representative of large urban centers in the Hispanic world, suitable for studying geographical and social varieties. A sample of the corpus is accessible on the web at https://preseea.uah.es/, accessed on 15 June 2023. Access is provided to semi-directed oral interviews—18 interviews per city with their corresponding transcriptions, produced by male and female speakers of three age groups (20–34; 35–54; 55+) and three levels of education (low, medium, high) (Moreno Fernández 2021).

In this study, the Latin American cities listed below have been focused on, which were grouped according to the Latin American dialectal areas established by Moreno Fernández (2019, a.o), RAE-ASALE (2009), Malaver (2022), and Orozco (2022), while we are aware of the need to review the generally accepted dialectal areas when analyzing strictly grammatical phenomena (Fernández-Ordóñez 2022). The Mexican variety and the Central American varieties are considered as members of a single dialectal area in Moreno Fernández (2009), Moreno Fernández and Otero Roth (2016) and RAE-ASALE (2009), although they appear as separate dialectal areas in Moreno Fernández (2019). The scarcity of examples from the only Central American country represented in Preseea (Guatemala, 122,478 words) has determined that we adopt the Mexico–Central American area as a unit to avoid the atomization of the counts for each lexical–semantic class of adjectives. For the same reason, we have decided not to differentiate between insular Caribbean and Antillean Caribbean areas. The other areas (Andean, Chilean and Rioplatense or Austral areas) have been considered independently, following the aforementioned references, which define them as distinct areas.

The interviews used as a corpus for elaborating the database have a total of 3,278,060 words. The number of words of each subcorpus, the acronyms of each city (which are also used in the references of the examples in this paper), and the time range in which the texts were compiled are as follows:

- Mexican and Central American area: Mexico (Mexicali MXLI, Ciudad de Mexico MEXI, Guadalajara GUAD, Monterrey MONR, Puebla PUEB); Guatemala (Ciudad de Guatemala GUAT): 108 interviews, 1,280,631 words (1,158,153 words in Mexico and 122,478 in the Central American area). Data collected between 11-2001 and 03-2018.

- Caribbean area (Continental and Antillean): Colombia (Barranquilla BARR), Venezuela (Caracas CARA), Cuba (La Habana LHAB): 54 interviews, 479,038 words (07-2001–12-2011)

- Andean area: Bolivia (La Paz LPAZ), Colombia (Bogota BOGO, Cali CALI, Medellin MEDE, Pereira PERE), Peru (Lima LIMA), Venezuela (Mérida MEVE): 126 interviews, 969,863 words. (08-2004–10-2022)

- Chilean area: Chile (Santiago de Chile SCHI): 18 interviews, 208,938 words. (05-2007–04-2009)

- Rioplatense area: Argentina (Buenos Aires BAIR), Uruguay (Montevideo MONV): 36 interviews, 339,590 words. (11-2007–06-2012)

As will be shown more specifically below, the differences found in the extent of the innovative estar-structure between areas indicate genuine dialectal differences, which do not derive from an imbalance in the corpus used to compile the database.

The search interface of Preseea allows for including lemmas and categorial tags. The following search strings were used to extract documented examples of the innovative estar-structure with adjectival predicates. The searches were carried out between March and July 2023:

- (1) Search 1: any form of the verb estar + an adjective

- ([(lemma=‘estar’ & pos=‘V.+’%c)] [(pos=‘AQ.+’%c)])

- (2) Search 2: any form of the verb estar + an adverb + an adjective

- ([(lemma=‘estar’ & pos=‘V.+’%c)] [(pos=‘R.+’%c)] [(pos=‘AQ.+’%c)]).

- (3) Search 3: sequences Qué + adjective + any form of the verb estar

- [(word=‘qué’%c)] [(pos=‘AQ.+’%c)] [(lemma=‘estar’%c)]

These searches yielded 2881 naturalistic examples of estar-sentences, with a total of 337 adjectives. In this paper, only those adjectives that appear in at least one example illustrating the innovative estar-structure were considered for inclusion in the database in order to provide quantitative-based generalizations. Thus, perfective adjectives and adjectival participles were excluded from our database, as they were found only in examples illustrating the general/standard use of copular estar-sentences. Other qualifying adjectives documented only in general/standard sentences were not considered from the quantitative perspective, but were used to build up descriptive generalizations, as will be shown below. Furthermore, given the relevance to the analysis here of the lexical–syntactic class to which an adjective belongs, the methodological decision was taken to not include in the database those lexical items whose syntactic–semantic properties are not well established in the literature and do not fit into the lexical–syntactic classes mentioned in Section 2.4 The remaining examples were classified as “general/standard” or “innovative”, according to the definitions provided in the previous section. In cases where the context did not allow the researchers to clearly determine the innovative or standard interpretation of the estar-sentence (recall Note 2), it was considered uninterpretable and was excluded from subsequent counts.

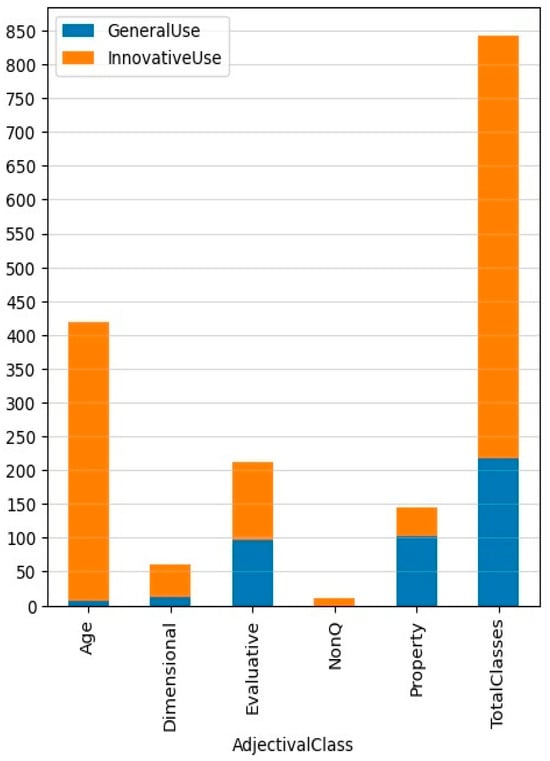

Once these methodological decisions were undertaken, the database used to establish the quantitative-based generalizations that will be presented in the following subsections includes 88 adjectives that appear in at least 1 example of innovative estar-structure, with a total of 847 examples: 215 examples illustrating the general/standard use of estar and 632 innovative examples. In cases where a single form has two different syntactic–semantic uses, consecutive numeration has been used to differentiate each of them: e.g., chiquito1 is an age adjective, and chiquito2 is a dimensional size adjective.

The examples in the database were annotated with the following information retrieved from the corpus: interview reference, city, country, gender, age and educational level of the interviewee.5 The countries were linked to the dialectal areas indicated above. Moreover, adjectival predicates were classified according to the lexical–semantic–syntactic classes established in Demonte (1999a, 1999b, 2011, apud Dixon 1982), which were introduced in Section 2:

- Qualifying adjectives:

- (f)

- Dimensional adjectives.

- (g)

- Age adjectives.

- (h)

- Property adjectives.

- (i)

- Color adjectives.

- (j)

- Evaluative adjectives.

- Extreme-degree adjectives.

- Aesthetic adjectives.

- Predicates of personal taste.

- Predicates of personal judgment.

- Other evaluatives.

- Non-qualifying adjectives: relational, circumstance or adverbial and modal adjectives.

In the following section, the findings on the extent of the innovative estar-construction in American Spanish are presented, considering the lexical–syntactic classes of adjectival predicates that appear in it and their geographical extension.

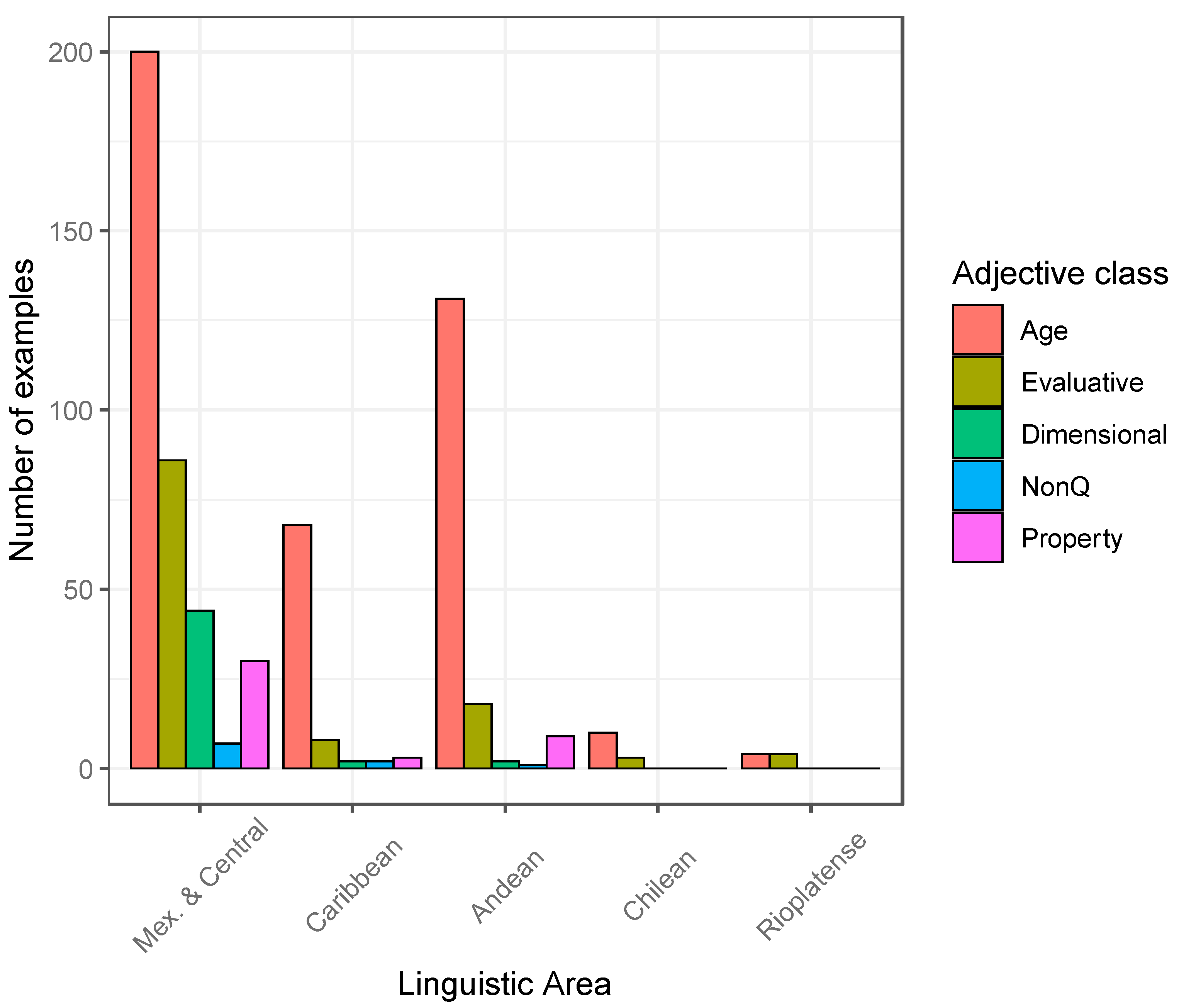

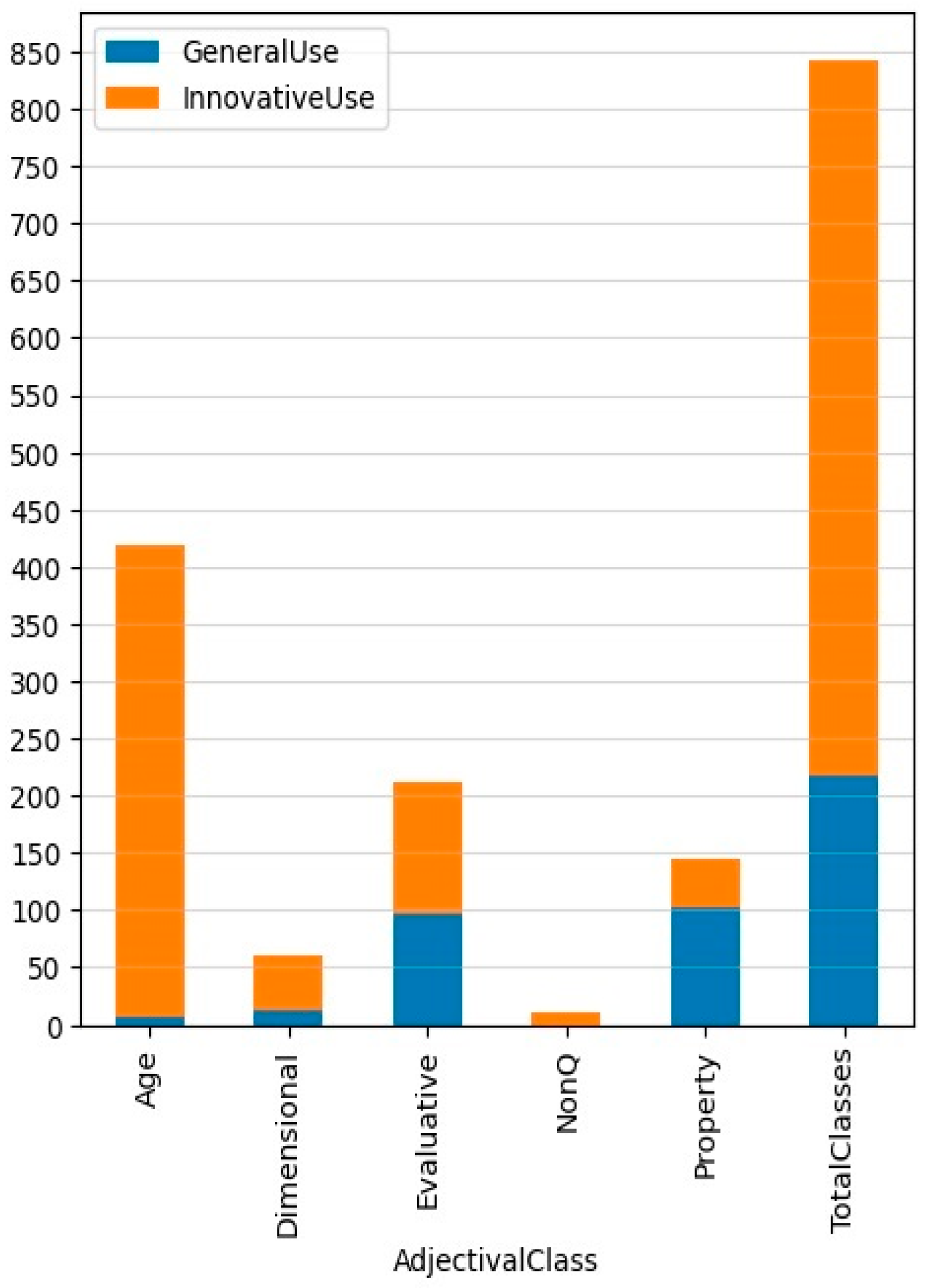

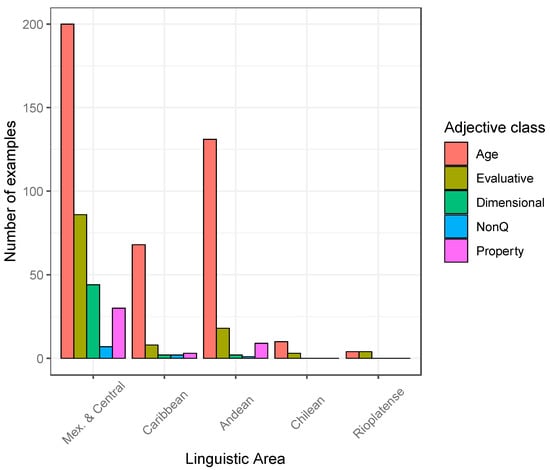

4. Results of the Corpus Study: Lexical–Syntactic Classes of Adjectives in Innovative Estar-Sentences

Table 1 below shows the total number of estar-sentences found for each lexical–syntactic class of adjectives. As mentioned above, the database contains 847 examples—215 examples illustrating the general/standard use of estar and 632 innovative examples—with a total of 88 adjectives. Recall that only adjectives appearing in at least one example of innovative estar-structure were included in the database. Table 2 below shows the geolectal distribution of the 632 innovative estar-sentences documented in the database, considering the lexical–syntactic class to which the adjectival predicates belong. The adjectival classes are presented in decreasing order from left to right according to their occurrence in a greater or lesser number of dialectal areas: age adjectives > evaluative adjectives (considering this class as a whole) > dimensional adjectives > property adjectives > and non-qualifying adjectives (adverbial, relational, and modal adjectives) used as predicates. The dialectal areas have been ordered taking into account the north–south geographical axis.

Table 1.

Total number of general and innovative examples in the database by adjectival class.

Table 2.

Geolectal distribution of the innovative estar-sentences by lexical–syntactic classes of adjectives.

In the following subsections, each of the adjectival classes will be discussed in more detail. The ordering of the dialectal areas will be the same in all the tables shown.

4.1. Age Adjectives

- Number of age adjectives in the database found in at least one innovative example and total number of examples for this class: 13 age adjectives (expressing the chronological age of an animate entity) occurring in at least one innovative estar-sentence were included in the database, with a total of 419 examples.

- Number of general/innovative examples: As can be seen in Table 3 above, 98.6% of the total of 419 examples illustrate the innovative use of the copular structure.

Table 3. Age adjectives in estar-sentences.

Table 3. Age adjectives in estar-sentences.

- Lexical items: The adjectives documented in innovative estar-sentences are the following: adolescente “adolescent”, adulto “adult”, chavo “little”, chico1 “little”, chiquitito “very little”, chiquito1 “very little”, grande1 “old”, joven “young”, mayor “old”, niño “little”, pequeño1 “little”, sardino “adolescent”, viejo1 “old”. Only grande1, mayor, viejo1 “old” also appeared in examples illustrating the standard structure with estar.Some adjectives appear only once and restricted to a single dialectal area: adolescente “adolescent” (Chile), adulto “adult”, sardino “adolescent” (Colombia), chavo “little” (Mexico). On the contrary, the forms chico1 “little”, chiquito1 and chiquitito1 “very little”, are documented in innovative examples in all varieties except in those from the Rioplatense area. Grande1 and viejo1 are documented in innovative examples in all dialectal areas.

- Dialectal distribution: The presence of this class of adjectives in the innovative structure is documented in all the dialectal areas, with similar percentages, except for the Rioplatense area.6 Thus, the appearance of this class of adjectives in combination with estar to express chronological age can be considered a robust innovative characteristic of American Spanish, as has been claimed in the literature. If the row% is considered, it is Mexican and Central American (48%), Andean (31%), and Caribbean (16%) areas that are leading in innovation with age adjectives.

- Other adjectives of this class found in the corpus exclusively in standard estar-sentences: It is also important to note that no age adjective has been documented exclusively in estar-sentences illustrating the standard/general use.

- Examples: Some innovative examples with adjectives of this kind are offered in (7)–(9) below. In these examples, the estar-sentence solely expresses chronological age.

| (7) | I: y ya | tiene | una | niña (…) | una beba | de | tres | meses |

| and already | has | a | baby | a baby-girl | of | three | months | |

| E: está | bien | chiquita | ||||||

| is.ESTAR.3.sg | really | small | ||||||

| I: and she already has a baby girl (…) a three-month-old baby girl. E: she (the baby) is very little/young. (México, MONR_M21_044) | ||||||||

| (8) | [Context: Talking about the changes that Medellín has undergone] | ||||||

| (…) pues | o sea | los | años | cuando | yo | ||

| (…) mmm | well | the | years | when | I | ||

| estaba | joven// | por ahí | de | quince | de dieciocho | años | |

| was.ESTAR | young | around | of | fifteen | of eighteen | years | |

| nunca | pensé | ver | esta | ciudad | como está | ahora | |

| never | thought.1.sg | see | this | city | as is | now | |

| Well, when I was young, around fifteen or eighteen years old, I never thought I would see this city as it is today. (Colombia, MEDE_H21_002) | |||||||

| (9) | [Context: Telling anecdotes of life] | |||||||

| (…) | esa | noche | del | terremoto (…) | /estaba | un | mi | |

| (…) | that | night | of.the | earthquake | was.ESTAR.3.sg | a | my | |

| hermano/ | (…) con | mis | hijos, | ellos | estaban | pequeños, | mi | |

| brother | with | my | children | they | were.ESTAR.3.pl | little | my | |

| esposa | y | yo | 30 | |||||

| wife | and | I | 30 | |||||

| …that night of the earthquake (…)/my brother was there/(…)/with my children, they were young, and my wife and I were 30 years old. (Guatemala, GUAT_H31_031) | ||||||||

The standard use is illustrated in the following example, where the adjective expresses (possibly ironic) the inadequacy of age for a certain activity: E.: ¿y sos de ir a bailar?—I.: ahora muy poco/antes sí (…) ahora como que ya con veintitrés años ya estoy viejo ya para eso <risas> “E.: And do you go dancing?—I.: now very little/before I did (…) now I’m twenty-three years old and I’m.ESTAR too old for that <laughs>“ (Uruguay, MONV_H11_035).

4.2. Evaluative Adjectives

The macro-class of evaluative adjectives consists of semantic and syntactically complex subclasses of adjectives with unequal behavior in the innovative structure with estar. Taken as a whole, as shown in Table 4, this macro-class appears in innovative estar-sentences in all dialectal areas: 95 examples out of 214 illustrate the general use (4.4%) and 119 examples illustrate the innovative use (55.6%). In the area of Mexico and Central America, the number of innovative estar-sentences in which this class of adjectives appears exceeds the number of sentences illustrating the standard/general use. If the row% of innovative use is considered, it is the Mexican and Central American area that is leading in innovation with this adjectival class.

Table 4.

Evaluative adjectives in estar-sentences.

In the following subsections, extreme-degree adjectives (Section 4.2.1), adjectives of personal judgment (Section 4.2.2), aesthetic adjectives (Section 4.2.3) and the heterogeneous class of “other” evaluative adjectives are analyzed separately. It should be noted that predicates of personal taste were found in the corpus only in standard estar-sentences. Specifically, 21 examples were found of standard estar-sentences with the adjectives bárbaro1 “awesome”, bueno1 “good”, exquisito “exquisite”, rico2 “tasty” used as personal taste predicates (see the example (16) below). Recall that it has been generally claimed in the literature that predicates of personal taste have an experiencer/judge argument in their argument structure that can provide counterparts to form the within-the-individual comparison class required in estar-sentences in standard Spanish, giving rise to an experiential reading (see example (2) above) (Moreno-Quibén 2022; Gumiel-Molina et al. 2023).

4.2.1. Extreme-Degree Adjectives

- Number of extreme-degree adjectives in the database found in at least one innovative example and total number of examples for this class: five extreme-degree adjectives occurring in at least one innovative estar-sentences were included in the database, with a total of nine examples.

- Number of general/innovative examples: As can be seen in Table 5, eight examples (88.9%) of the total of nine examples illustrate the innovative use of the copular structure.

Table 5. Extreme-degree adjectives in estar-sentences.

Table 5. Extreme-degree adjectives in estar-sentences.

- Lexical items: The adjectives documented in innovative estar-sentences are the following: especial “special”, impresionante “impressive”, mortal “terrific”, terrible “horrible”, tremendo “tremendous” (with also one occurrence in the general structure).

- Dialectal distribution: The innovative use of this class of adjectives in estar-sentences is documented in the Mexican and Central American and Andean areas.7

- Other adjectives of this class found in the corpus exclusively in standard estar-sentences: It is also important to note that 18 adjectives belonging to this class have been documented in the corpus exclusively in estar-sentences illustrating the standard/general use (occurrence-range from 1 to 22, in a total of 107 examples): bárbaro2 “awesome”, bravo1 “great”, bonito2 “beautiful”, chévere “cool”, chido “cool”, divino “divine”, espantoso “awful”, espectacular “amazing”, fabuloso “fabulous”, feo2 “ugly”, genial “great”, grande3 “great”, horrible “horrible”, ideal “ideal”, lindo2 “nice”, padre “great”, perfecto “perfect”, pésimo “terrible” y rico3 “nice” (some are restricted to specific areas such as padre, chido Mx.).

As was claimed before, extreme-degree adjectives expressing highest positive or negative degree, such as those in (4a) and (4b) (espectacular “amazing”, bárbaro “awesome” and genial “great”), have an experiencer/judge in their argument structure in standard Spanish. When they appear as predicates in copular estar-sentences, this argument provides counterparts to form a within-an-individual comparison class, giving rise to the general/standard judge-oriented estar-sentences. It should be remembered that in these sentences, the subject expresses a situation (when it refers to structured events or to propositional content) or takes part in a situation in which the experiencer/judge also participates.

- Examples: Innovative examples typically have subjects that are not possible in general Spanish in estar-sentences with this kind of adjective. In (10), the subject expresses an unstructured event (collision) in which the experiencer/judge does not play any role (contrary to what happened in (4) above); (11) below refers to magnitudes or abstract entities.

| (10) | [Context: Talking about the work and importance of paramedics] | |||||||

| ellos | también | ven | muchas | cosas | (…) por | ejemplo | ||

| they | also | see.3.PL | many | things | for | example | ||

| unos | choques | que | están | impresionantes | ||||

| some | collisions | that | are.3.PL.ESTAR | impressive | ||||

| They also see many things (…) for example, some collisions that are very impressive. (México, PUEB_M23_069) | ||||||||

| (11) | a. [Context: Someone is narrating coming from a distant city] | |||||||

| (…) la | distancia | de | norte | a | sur | está | tremenda | |

| the | distance | from | north | to | south | is.ESTAR | tremendous | |

| The distance from north to south is tremendous. (México, MEXI_H21_090) | ||||||||

| b. (…) | ni | de | ir | a | ningún | lugar | porque | |

| or | of | going | to | any | place | because | ||

| el | frío | está | terrible | |||||

| the | cold | is.ESTAR | terrible | |||||

| You cannot go anywhere because the cold is terrible (Bolivia, LPAZ_M32_016) | ||||||||

4.2.2. Adjectives of Personal Judgment

- Number of adjectives of personal judgment in the database found in at least one innovative example and total number of examples for this class: nine adjectives of personal judgment occurring in at least one innovative estar-sentence were included in the data base, with a total of 102 examples.

- Number of general/innovative examples: As shown in Table 6, there are 41 innovative examples (40.2%) vs. 62 examples (59.8%) illustrating the standard/general use of the copular structure.

Table 6. Adjectives of personal judgment in estar-sentences.

Table 6. Adjectives of personal judgment in estar-sentences.

- Lexical items: The adjectives documented in innovative estar-sentences are the following: bizarro “bizarre”, difícil “difficult”, fuerte2 “strong”, grueso2 (meaning “difícil”) “difficult”, leve “slight”, pesado “heavy”, raro “weird”, suave2 “pleasant”, trabajoso “laborious” (range of innovative examples of each item from 1 to 18).

- Dialectal distribution: Standard examples are documented in all dialectal areas; innovative examples are restricted to the Mexican and Central American, Caribbean and Andean areas.

- Other adjectives of this class found in the corpus exclusively in standard estar-sentences: It is also important to note that 10 adjectives belonging to this class have been documented in the corpus exclusively in estar-sentences illustrating the standard/general use, with a total of 14 examples (range of occurrences of each adjective 1–3): aceptable “acceptable”, agradable “pleasant”, cómico (meaning “divertido”) “funny”, complicado “complicated”, crítico (meaning “difícil”) “difficult”, divertido “fun, amusing”, duro2 “hard”, extraño “strange”, fácil “easy”, fastidioso “annoying”. Examples:

As was also explained before, predicates of personal judgment also have an experiencer/judge argument (fácil/difícil/divertido for X). Thus, when they appear as predicates in copular estar-sentences in standard Spanish, this argument can provide counterparts to form a within-the-individual comparison class. This is the case in sentences like La crianza de los hijos está muy difícil “Parenting is.ESTAR very difficult” (Colombia, BOGO_M22_057), whose subject expresses a situation in which the experiencer/judge participates. Recall also (3).

- Examples: The following examples below are illustrative of the innovative construction. In (12), a lexical item (fuerte “strong”) that does not combine with estar in standard Spanish is presented (note that the same lexical item is combined with ser in the same context in the previous discourse. In (13) and (14), subjects that are not possible in standard sentences with these predicates are illustrated, that is to say, events in which the experiencer/judge does not participate or other kinds of abstract nouns.

- (12)

- [Context: talking about religious life]Previous paragraph:

I: [La muerte] (…)/no posee nada//no tiene nada…

E: pero que a la vez eso también es muy fuerte/¿no? o sea no poseer nada…

(…)

I: (…) yo tengo por ahí un amigo/muy querido que renunció a todo (…) es un misionero/franciscano

E: y su amigo por ejemplo/¿a qué edad decidió?

I: muy joven/a los veinticinco años

“I: [Death] (…)/possesses nothing//has nothing…

E: but, at the same time, that is.SER also very harsh/isn’t it? that is to say, not owning anything?

(…)

I: (…) I have a very dear friend who renounced everything (…) he is a Franciscan/Franciscan missionary.

E: and your friend for example/at what age did he decide?

I: very young/at the age of twenty-five.”

| es que | está | muy | fuerte | eso/ | tienes | que | estar | |

| well | is.3.SG.ESTAR | very | strong | that | have.2.SG | to | be | |

| muy | convencido | |||||||

| very | convinced | |||||||

| That’s very strong, you have to be very convinced. (México, MONR_M22_060) | ||||||||

- (13)

- Previous paragraph:

I: …incrédulos de lo que estaba pasando porque pues/nosotros lo habíamos visto ayer y ahora ya no está/así como que te quedas/(…)/

“we were incredulous at what was going on because/we had seen him yesterday and now he’s gone/so you’re just like…”

| te | digo | que | estuvo | muy | rara | su | muerte | |

| you.DAT | tell | that | was.3.SG.ESTAR | very | weird | his | death | |

| I tell you that his death was very weird. (México, MONR_M22_060) | ||||||||

| (14) | a. | [Context: Talking about the psychology studies that the speaker completed in her youth] | ||||||

| ¿Está | muy | difícil | la | carrera? | ||||

| is.3.SG.ESTAR | very | difficult | the | degree | ||||

| Is the degree very difficult? (México, MXLI_M23_032) | ||||||||

4.2.3. Aesthetic Adjectives

The class of aesthetic adjectives (bello “beautiful”, guapo “handsome”, lindo “cute, beautiful”…) expresses the aesthetic value of an entity. These adjectives give rise to a within-the-individual comparison based on the subject of predication when combined with estar in standard/general Spanish, as it was shown previously in Section 2. The distribution of the data for this class of adjectives is shown in the table below.

- Number of aesthetic adjectives in the database found in at least one innovative example and total number of examples for this class: seven aesthetic adjectives with at least one innovative occurrence were found in the database, with a total of 74 examples.

- Number of general/innovative examples: As shown in Table 7, 41 examples (55.4%) of the total of 74 examples illustrate the innovative use of the copular structure. 33 examples (44.6%) illustrate the standard/general use.

Table 7. Aesthetic adjectives.

Table 7. Aesthetic adjectives.

- Lexical items: The adjectives documented in innovative estar-sentences are the following: bello, bonito1 “beautiful”, feo1 “ugly”, guapo “handsome”, hermoso, lindo1 “beautiful”, precioso “precious” (the number of examples obtained for each ranges from 1 to 25—bonito1 “beautiful”––). The adjectives bello, bonito1 “beautiful”, feo1 “ugly”, precioso “precious” and lindo “cute, beautiful” were also documented in examples illustrating the general use of estar-sentences.

- Dialectal distribution: As can be seen in Table 7, the number of innovative examples exceeds the number of standard estar-sentences, but this pattern is marked only in the Mexican and Central American area and the Caribbean area. These results are consistent with the conclusions reached by Moreno-Quibén (2022) and Gumiel-Molina et al. (2023), where the innovative use of estar-sentences with aesthetic adjectives is explored in detail.

- Other adjectives of this class found in the corpus exclusively in standard estar-sentences: It is important to note that no adjectives of this kind appeared only in standard context in the corpus.

- Examples:

Some examples illustrating the innovative use of estar-sentences with aesthetic adjectives are offered in (15)–(17) below. These examples do not compare counterparts of the subject, as is clearly seen in (15)–(16), where the speaker relates his first experience with an unknown referent and therefore no comparison can be made with previous counterparts or with possible alternative counterparts based on an expectation. In (17) the innovative structure appears within an intensional context. It is important to note that, according to both Moreno-Quibén (2022) and Gumiel-Molina et al. (2023), aesthetic adjectives lack an experiencer/judge argument in the standard variety of Spanish (even though expressing an evaluative property, see McNally and Stojanovic 2015); the presence of this argument is, in their proposal, the locus of the syntactic variation giving rise to the innovative examples in some American varieties, as will be seen below.

- (15)

- Previous paragraph:

- … ahora/te voy a contar/si me lo permites//cómo//conoció (…) a mi madre//mi padre//con veintipico de años//ya tenía/carro propio (…) y pasa/por delante//de uno de los palacios/más/ostentosos de//del Vedado//(…) y da la casualidad/que mi mamá//que era/ayuda de cámara//de la señora/de esa casa//de esa mansión//y mi madre/en ese momento/se encontraba/en el jardín//(…) mi padre/se quedó mirando//detuvo el carro//y lo primero que dijo/“esa gallega/tiene que ser para mí, porque ¡qué hermosa!

- “… now/I’m going to tell you/if you allow me//how//he met (…) my mother//my father//in his early twenties//already had/his own car (…) and passed/in front//of//one of the most/splendid/palaces//in Vedado//(…).) and it so happens/that my mother//who was/a chambermaid//of the lady/of that house//of that mansion//and my mother/at that moment/was/in the garden//(…) my father/stared//stopped the car//and the first thing he said/”that gallega/has to be for me because!

| “¡qué | bella | está!” | ¡bueno! | entonces | él | se apea | del carro | |

| how | beautiful | is.3.SG.ESTAR | well | then | he | got out | of.the car | |

| “How beautiful she is!”//well!//then he got out of the car. (LHAB_H33_097, La Habana, Cuba) | ||||||||

| (16) | y | me | vendió | la | torta | y | la | torta |

| and | me.DATIVE | sold.3SG | the | cake | and | the | cake | |

| estaba | sabrosa/ | y | estaba | bonita | ||||

| was.3.SG.ESTAR | tasty | and | was.3.SG.ESTAR | pretty | ||||

| And she sold me the cake and the cake was tasty and it was pretty. (Venezuela, CARA_M11_007) | ||||||||

- (17)

- Previous paragraph:

- yo mi mundo lo hacía muy cerradito (…)/o sea nunca andaba con alguien que no bailara o que no fuera músico/

- “my world was very closed (…)/I never went with someone who didn’t dance or wasn’t a musician”

| o | que | no | estuviera | muy | guapo | o sea | o | que |

| or | who | not | was.3.SG.SUBJUNCTIVE.ESTAR | very | handsome | that is | or | who |

| no | fuera | como | de | la | moda | |||

| not | was.3.SG.SER | like | of | the | fashion | |||

| [someone] who wasn’t very handsome or wasn’t fashionable. (Mexico, MEXI_M12_048) | ||||||||

4.2.4. Other Evaluative Adjectives

Finally, there is a group of lexical items with evaluative meaning that are difficult to classify in the aforementioned classes, which have been considered together. Their distribution is shown in Table 8:

Table 8.

Other evaluative adjectives.

- Number of other evaluative adjectives found in the database exclusively in innovative examples and total number of examples for this class: 8 adjectives of this class were included in the database, with a total of 29 examples.

- Number of general/innovative examples: All the examples illustrate the innovative use of copular estar-sentences.

- Lexical items: The adjectives documented in innovative estar-sentences are the following: (occurrence range 1–15 –peligroso “dangerous”–): conflictivo “conflictive”, correcto “correct”, importante “important”, inseguro “insecure”, peligroso “dangerous”, recto “upright” (moral predicates, Stojanovic and McNally 2022), seguro3 “secure”, significativo “significant”.

- Dialectal distribution: These evaluative adjectives are documented in all dialect areas, although their number is higher in the Mexican and Central American area. Examples: Some innovative examples are shown below. The adjectives in (18), (19), and (20) are ungrammatical in standard Spanish with the copula estar. In these examples, the subjects refer to abstract entities, situations or propositional contents. When the subject refers to places, (21), no counterparts of the entity referred to are compared.

- (18)

- Previous paragraph:

E: ¿y vio bastantes cambios en su casa o sigue estando así/desde siempre?

I: la casa ha tenido cambios/(…) pero últimamente está muy estático (…) hacemos pequeños cambios

“E: and did you see many changes in your house or has it always been like this?

I: the house has had changes/(...) but lately it is very static (…) we make small changes”

| pero | que | no | están | muy | significativos | |||

| but | that | not | are.3.PL.ESTAR | very | significant | |||

| but they are not very significant. (Bolivia, LPAZ_M23_012) | ||||||||

- (19)

- Previous paragraph:

- [alguien recibe una llamada de teléfono]… “chamo vente para tu casa ¿no viste el mensaje?/te mandé un mensaje ahorita/que hay un primo tuyo herido”, y yo “¿herido güevón?”/no le paré mucho/me vuelvo a meter en clase/leo el mensaje ¡verga! (…) y entonces/yo bueno vamos a esperar un ratico a ver/

- “[someone receives a phone call]… “boy, come home, didn’t you see the message?/I sent you a message right now/that your cousin is hurt”, and I “hurt, asshole?”/I didn’t pay much attention/I go back to class/I read the message (…) and then/well, let’s wait a little while to see/”

| la | clase | estaba | muy | importante | ta ta ta | y | yo | estaba |

| the | class | was.3.SG.ESTAR | very | important | uh | and | I | was |

| preocupado | ya, | ¿no? | ||||||

| worried | already | wasn’t I | ||||||

| the class was very important, uh, and I was already worried, wasn’t I? (Venezuela, CARA_H13_073) | ||||||||

- (20) [Context: talking about punishments in cases of corruption or criminal acts in the armed forces; the speaker refers to the military base of Sonoyta, Mexico, where in his opinion the law is applied fairly and equally regardless of military rank]

- Previous paragraph:

I: sí pero estamos hablando que/estamos hablando de que la gente de arriba/entre más estrellas y más barras tengan/menos les pasan cosas pues (…)

E: siempre es así //pero te voy a decir que

“I: yes but we are saying that/we are saying that the people at the top/the more stars and bars they have/the less things happen to them so (…).

E: it’s always like that//but I’m going to tell you that

| ahí | la | de | Sonoyta | estaba | muy | recto | todo | |

| there | the | of | Sonoyta | was.3.SG.ESTAR | very | upright | everything | |

| there in Sonoyta everything was very upright. (México, MXLI_H12_011) | ||||||||

- (21)

- Previous paragraph:

E: sí/lo/pues nosotros siempre/en mi familia siempre vamos a la playa en semana santa/nada más que/lo único malo es como que el tráfico/que hay muchísima gente en esa en esa semana

I: sí

E: sí, y hay muchos accidentes

I: y luego para allá, para Autlán/eres de Autlán ¿verdad?

E: sí

“E: yes/well/well we always/in my family we always go to the beach during Easter week/the only bad thing is the traffic/there are a lot of people during that week

I: yes

I: yes and there are a lot of accidents

I: and then to Autlan/you are from Autlan, right?

E: yes”

| I: | para | allá | las | curvas | están | medias | peligrosas | |

| over | there | the | bends | are.3.SG.ESTAR | half | dangerous | ||

| Over there the bends are quite dangerous (continuation: Sí sí, he manejado para allá y está complicadón “Yes, yes, I have driven there and it is very complicated”). (Mexico, GUAD_H23_004) | ||||||||

4.3. Dimensional Adjectives

Number of dimensional adjectives in the database found in at least one innovative example and total number of examples for this class: 15 dimensional adjectives occurring in at least 1 innovative example were included in the database, with a total of 60 examples. Their distribution is shown in Table 9:

Table 9.

Dimensional adjectives.

- Number of general/innovative examples: As can be seen in Table 9, 48 examples (80%) of the total of 60 examples with dimensional adjectives illustrate the innovative use of the copular structure. However, these examples are restricted mainly to the Mexican and Central American area.

- Lexical items: The adjectives documented in innovative estar-sentences are the following: (occurrence range 1–4): amplio “large”, ancho “wide”, bajo1 “short”, chaparrito “short”, chico2, chiquito2 “little”, enano “tiny”, enorme “huge”, espacioso “spacious”, extenso “large”, grande2 “big”, grueso1 “thick”, largo “long”, pequeño2 “small”, reducido “cramped”. Only the adjective grande2 “big” has been documented also in standard examples (12 standard examples and 22 innovative examples).

- Dialectal distribution: The innovative use of this class of adjectives in estar-sentences is documented in the Mexican and Central American area, and also in the Caribbean and Andean areas. If the row% of innovative use is considered, it is the Mexican and Central American area that is leading in innovation with this adjectival class.

- Other adjectives of this class found in the corpus exclusively in standard estar-sentences: six dimensional adjectives belonging to this class have been documented in the corpus exclusively in estar-sentences illustrating the standard/general use (occurrence-range from 1 to 18 –gordo–, in a total of 29 examples, distributed in all dialectal areas): alto1 “tall”, corto “short” (in examples such as Estamos cortos de dinero “We are short of money”), and adjectives expressing weight: delgado “thin”, gordo “fat”, flaco “thin”.

- Examples: Some innovative examples are offered in (22)–(26) below; see also (5) above. None of them express a comparison between counterparts of the subject of predication with respect to the dimensional property expressed by the adjective. The innovative use is more frequent when the subject does not refer to human or animate entities but to places, inanimate objects, or abstract concepts.

- (22)

- Previous paragraph:

I: pues ahora luego nos buscamos un lugar más grandecito porque sí

“I: well, now we are looking for a bigger place because”

| están | muy | reducidas | las | recámaras/ | apenas | una | camita |

| are.3.PL.ESTAR | very | small | the | bedrooms | just | a | bed |

| y | un | buró. | |||||

| And | a | desk | |||||

| E: | Ah | o sea sí | está | chiquito. | |||

| E: | Oh | yes | is.3.SG.ESTAR | small | |||

| The bedrooms are very small, just a bed and a bureau/E: Oh yes, it is very small. (Mexico, MEXI_M21_096) | |||||||

| (23) | E: (…) | ¿cómo | es | tu | casa? | ||

| How | is.3.SG.SER | your | house | ||||

| I: (…) | era | con | cochera/(…) | sala/(…) | estaba | muy | |

| was.3.SG.SER | with | garage | living room | was.3.SG.ESTAR | very | ||

| pequeña | la | casa | pero | estaba | muy | chida | |

| small | the | house | but | was.3.SG.ESTAR | very | nice | |

| E: What was your house like?/I: (…) it had a garage/living room/the house was very small but it was very nice. (Mexico, GUAD_H13_014) | |||||||

- (24) [Context: Talking about the interviewee’s participation in the dance of the Curpites in the role of a Curpite and about the costume he wore in that dance]

- Previous paragraph:

I: y la máscara pues de plano no te deja ver ni mais

E: sí/sí

I: y luego las mangas/o sea/sí me gustó

E: ¡y pesan!/¿no?

I: sí/pesan

E: sí pesa un buen/y la máscara es de madera/¿verdad?

I: sí

“I: and the mask doesn’t let you see anything else.

E: yes/yes

I: and then the sleeves/I mean/yes, I liked it.

E: and they are heavy, aren’t they?

I: yes/they are heavy

E: they do weigh a lot/and the mask is made of wood/isn’t it?

I: yes”

| E: | pero | sí | está | gruesa | ¿no? | ||

| but | yes | is.3.SG.ESTAR | thick | isn’t it | |||

| But it really is thick, isn’t it? (Mexico, MEXI_H12_042) | |||||||

- (25) [Context: Talking about the causes that make it take a long time to travel the distance between two nearby cities]

- Previous paragraph:

E: ¿porque están los precipicios?

I: sí/porque están los precipicios muy feos

E: y vienen los traileres bien rápido y puedes chocar de frente

I: sí entonces tienes que ir despacio/

“E: because of the cliffs?

I: yes/because the cliffs are very ugly (“bad”)

E: and the trailers come very fast and you can crash head-on.

I: yes then you have to go slowly/”

| eso | es | lo que | lo | hace | largo, | ||

| that | is.3.SG.SER | what | it.ACCUSATIVE | makes | long | ||

| pero | no | está | largo. | ||||

| but | not | is.3.SG.ESTAR | long | ||||

| That’s what makes it long/but it’s not long. (Mexico, MONR_M13_033) | |||||||

- (26)

- Previous paragraph:

I: porque mira/si tú vas y compras/un largo de tu pantalón/te cuesta cincuenta pesos/hay telas hasta de cuarenta pesos/y con un largo te haces un pantalón/con un largo de altura/a tu gusto/a tu medida/como tú lo quieras

“I: because, look/if you go and buy (…)/there are fabrics that cost up to forty pesos/and with a piece of fabric you can make a pair of pants/(…) according to your taste/to your size/the way you want them”

| E: eso | sí, | porque | ahorita, | ¿no?, | están | muy | chiquitas |

| E: yes, | because | now | right? | are.3.PL.ESTAR | very | small | |

| las | tallas | y | uno | batalla, | ¿no? | ||

| the | sizes | and | one | struggles, | right? | ||

| E: yes, because right now/right?/the sizes are too small and you struggle/right? (México, MONR_M31_082) | |||||||

4.4. Property Adjectives

- Number of property adjectives in the database found in at least one innovative example and total number of examples for this class: 24 adjectives expressing non-dimensional properties were found in at least one innovative example and included in the database, with a total of 144 examples.

- Number of general/innovative examples: As can be seen in Table 10, 102 examples (70.8%) of the total of 144 examples illustrate the general use of the copular structure, vs. 42 examples (29.2%) illustrate the innovative use.

Table 10. Property adjectives.

Table 10. Property adjectives.

- Lexical items: The following adjectives were documented exclusively in innovative sentences (occurrence range of each lexical item 1–6): accesible (meaning “cheap”), cariñoso (“expensive” in El Salvador and Mexico), chistoso “jokey”, cálido “warm”, costoso “expensive”, descarado “brazen”, despierto2 “alert”, entendible “comprehensible”, fuerte1 “hard”(“having strength or intensity”), invisible “invisible”, moderno (“modern, showing signs of modernity”), moroso “owing money”, pobre “poor”, puntual “punctual”, tenaz “tenacious”, raquítico “scarce, low in number”. On the other hand, the following adjectives appeared in both standard and innovative estar-sentences (the number of examples obtained for each of the adjectives ranged from one to seven in the innovative context and from one to 18 in the standard sentences): barato “cheap”, caliente “hot”, caro “expensive”, cómodo “comfortable”, cruel “unforgiving (applied to weather conditions)”, duro1 (“severe, intense”), frío “cold”, triste “sad”.

- Dialectal distribution: As shown in Table 8, the number of examples illustrating the general use exceeds the number of innovative sentences in all dialectal areas. The presence of this class of adjectives in the innovative structure is restricted to the Mexican and Central American, Caribbean and Andean areas. If the row% of innovative use is considered, it is the Mexican and Central American area that is clearly leading in innovation with this adjectival class.

- Other adjectives of this class found in the corpus exclusively in standard estar-sentences: It is important to note that a further 82 property adjectives were documented in the corpus exclusively in sentences illustrating the general use, in all dialect areas, with a total of 369 examples (occurrence range from 1 to 114) (e.g., alegre “cheerful”, blando “soft”, débil “weak”, feliz “happy”, incómodo “uncomfortable”, nervioso “nervous”, plano “flat”, suave1 “smooth”, tranquilo “quiet” etc.).

- Examples: Some innovative examples are offered in (27)–(31) below, with different kinds of semantic entities as subjects. None of them express a comparison between counterparts of the subject of predication with respect to the property denoted by the adjective.

- (27)

- Previous paragraph:

I: ahí deportes cómo no/me gusta más verlo no hacerlo/es un/es es admirar a los atletas

“I: sports, of course/I like more to watch sports, not to practice/to admire the athletes”

| E: | Sí, sí | está | más | cómodo | |||

| yes, yes | is.3.SG.ESTAR | more | comfortable | ||||

| I: | Me | canso | nomás | de | verlos | ||

| myself | get.tired.1.SG | just | of | watch.them | |||

| E: yes, yes, it’s more comfortable/I: I get tired just by watching them (Mexico, MONR_H13_025) | |||||||

- (28)

- Previous paragraph:

- me regalaron unas blusas y no me atrevo a ponérmelas/le digo a mi hija “ay nomás de pensar en mis brazotes que se me vean” (…) “ya estoy viejita”/“ay pero no” dice

- “they gave me some blouses as a present and I don’t dare to wear them/I tell my daughter “oh, just to think of my arms showing” (…) “I’m already old”/”oh, but no” she says

| “no | están | descaradas | tus | blusas | mama, | póntelas” |

| not | are.3.PL.ESTAR | brazen | your | blouses | mom | put-you.DAT-them.ACC |

| “Your blouses are not brazen, mom, put them on” (Mexico, MEXI_M21_096) | ||||||

| (29) | [Context: Talking about a performance that the speaker has attended] | ||||||

| y | el | guión | yo | siento | que | estuvo | |

| and | the | script | I | feel | that | was.3.SG.ESTAR | |

| muy | entendible, | pero | la | coreografía | ya | no | |

| very | comprehensible | but | the | choreography | then | not | |

| And the script, I feel that it was very comprehensible, but the choreography was not. (México, MEXI_H12_042) | |||||||

- (30) [Context: Talking about a cotton processing plant]

- Previous paragraph:

I: (…) están esperando venderla pero piden mucho dinero/no se ponen de acuerdo/(…) o sea/todos/cualquiera de los algodoneros que está ahí se las compra pero/que les den precio//un buen precio

E: sí

“I: (…) they are waiting to sell it but they are asking for a lot of money/they do not agree/(…) that is/everyone/any of the cotton growers that are there would buy it but/they have to give them a good price//a good price.

E: yes”

| I: | porque | está | buena | esta | planta | ||

| because | is.3.SG.ESTAR | good | that | plant | |||

| E: | está | muy | grande | también | |||

| is.3.SG.ESTAR | very | big | too | ||||

| I: | está | moderna | pues | y | tiene | mucha | velocidad |

| is.3.SG.ESTAR | modern | indeed | and | has | much | speed | |

| I: because that plant is good/E: it is also very big/I: it is modern and it is very fast. (Mexico, MXLI_H32_018) | |||||||

- (31) [Context: The interviewer anticipates the questions he/she is going to ask the interviewee next]

| las | siguientes | preguntas | están | bien | tristes | para | ti | |

| the | following | questions | are.3.PL.ESTAR | very | sad | for | you.OBL | |

| “The following questions are very sad for you”. (Mexico, GUAD_H12_098) | ||||||||

4.5. Non-Qualifying (Adverbial, Relational and Modal) Adjectives Used as Predicates

Table 11 shows the results obtained for this class of non-qualifying adjectives in estar-sentences.

Table 11.

Property adjectives.

- Number of non-qualifying adjectives in the database found in innovative examples and total number of examples for this class: seven non-qualifying adjectives occurring in innovative estar-sentences were included in the database, with a total of 10 examples (four adverbial adjectives with a total of seven examples, two relational adjectives with a total of two examples, one modal adjective found in one example).

- Number of general/innovative examples: Estar-sentences with adverbial, relational and modal adjectives as predicates exemplify a radically innovative use since these classes of adjectives are only combined with ser when they appear in copular structures in general Spanish.

- Lexical items: Regarding adverbial adjectives, the following lexical items were documented in the innovative structure: antiguo “old, ancient, antique”, frecuente “frequent”, incipiente “incipient”, nuevo2 “new”. Two color items were found used as relational adjectives to express a person’s race: negro “black”, moreno “brown” (other color adjectives have been found only in standard examples in the corpus; blanco “white”, gris “grey”, verde “green”, and also claro “clear”, pálido “pale”, with a total of nine examples). Finally, one modal adjective was documented: imposible “impossible”.

- Dialectal distribution: The innovative use of this class of adjectives in estar-sentences is documented in the Mexican and Central American, Caribbean and Andean areas.

- No other adjectives of this class were found in the corpus in estar-sentences.

- Examples: Adverbial adjectives are illustrated in (32) and (33) (note, in this example, that each of the participants in the conversation use different copulas with this lexical item). Relational adjectives and modal adjectives are illustrated in (34) and (35) respectively.

- (32) [Context: The interviewer asks if the interviewee has ever quit a job before and why]

- Previous paragraph:

I: en primer lugar//uno como vendedor rutero, no es un trabajo estable//que lo tenga uno//¿porque?//primero/por la situación que se está viviendo en Guatemala veá//

“I: first of all//one job as a route salesperson, it’s not a stable job//that you have//why?//first//because of the situation that Guatemala is going through//you see

| Que | los | asaltos | están | muy | frecuentes | ||

| That | the | muggings | are.3.PL.ESTAR | very | frequent | ||

| Muggings are very frequent. (Guatemala, GUAT_H12_044) | |||||||

- (33) [Context: Speaking of a store in the neighborhood]

- Previous paragraphs:

I: creo que ya tiene cuarenta/o más de cuarenta años (…) ese negocio sí

E: no pues sí ya está

I: sí ya/está

E: ya es

I: es antiguo

“I: I think it is already forty/or more than forty years old (…) that store yes.

E: no well, it is.ESTAR already

I: yes it already/is.ESTAR