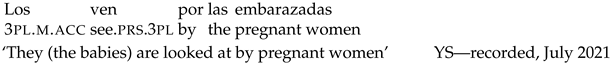

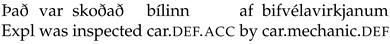

In this section, I compare and contrast A-P hybrids with other types of impersonal and passive constructions in Spanish. A-P hybrids are superficially very similar to sentences with “arbitrary plural” pronominal subjects (

Jaeggli 1986), such as (31).

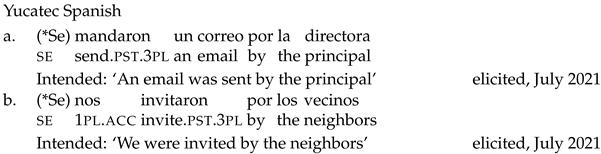

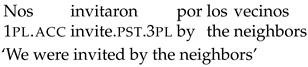

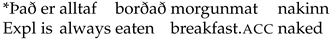

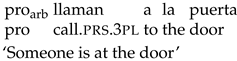

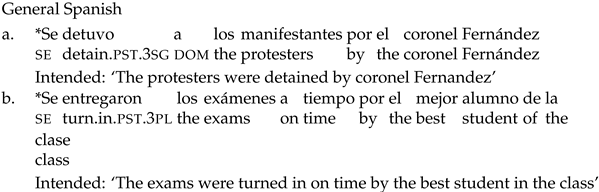

The arbitrary null pronoun in the subject position of such sentences is formally plural but semantically underspecified. It only indicates that there is an unspecified third-person subject that may be singular or plural. This mismatch between formal features and semantic interpretation is shared with A-P hybrids. Where arbitrary plural sentences differ from A-P hybrids is in their inability to accept by-phrases.

| (32) | ![Languages 09 00024 i038]() |

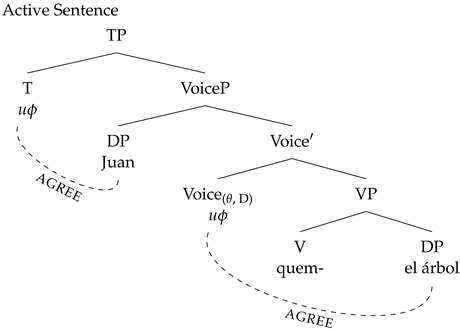

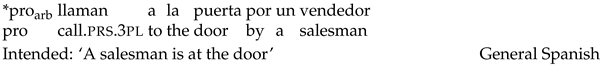

The difference between arbitrary plural sentences and A-P hybrids can be captured in the features of Voice and the nature of the pronominal element in the specifier of Voice. Arbitrary plurals are transitive sentences in which a full DP saturates the argument of a Voice head with a “D” feature, while A-P hybrids are grammatical object passives in which a

P restricts the argument variable of an initiator predicate introduced in Voice.

| (33) | ![Languages 09 00024 i039]() |

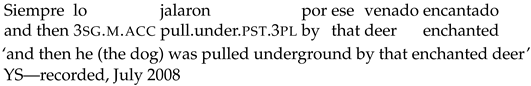

A-P hybrids are also similar to non-paradigmatic SE constructions (see

MacDonald and Maddox (

2018),

Ormazabal and Romero (

2019) and (

Saab 2020) for recent overviews and analyses), which include what are traditionally known as impersonal and passive SE constructions.

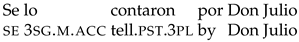

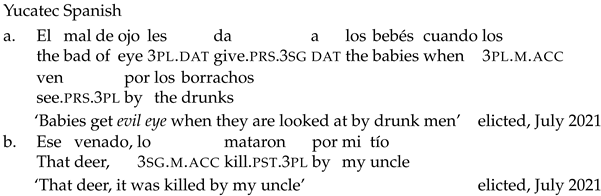

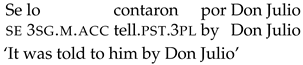

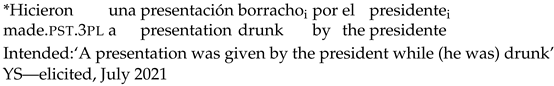

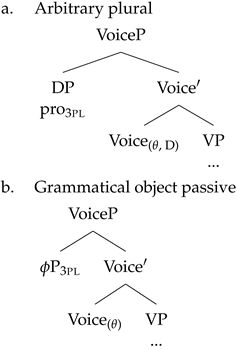

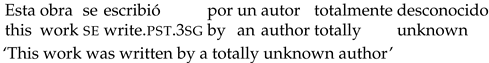

| (34) | ![Languages 09 00024 i040]() |

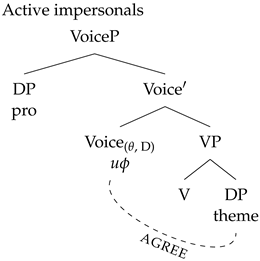

MacDonald and Maddox (

2018) have argued, based on data such as (29), that non-paradigmatic

se constructions have a null pronoun with a “D” feature that saturates the external argument variable introduced in Voice. Moreover, it has been argued in both

Ormazabal and Romero (

2019) and (

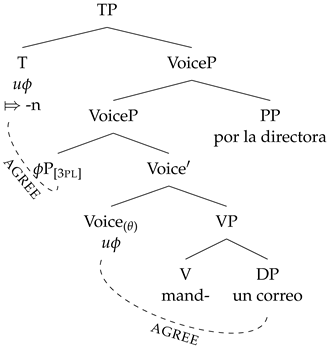

Saab 2020) that the variable agreement on the verbs in non-paradigmatic SE constructions is not really an indication of an active–passive distinction. Both sentences in (34) are active transitive sentences, and the apparent agreement between the verb and the object in (34-b) can be handled outside of the narrow syntax. Based on this work, I assume that non-paradigmatic SE constructions have the structure below. I follow

MacDonald and Maddox (

2018) in assuming that

se is a Voice morpheme generated in the Voice head.

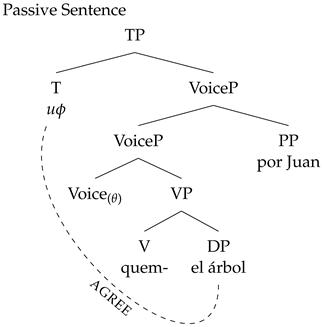

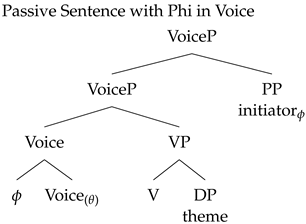

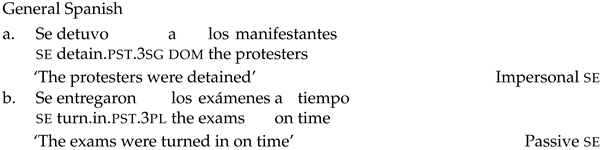

| (35) | ![Languages 09 00024 i041]() |

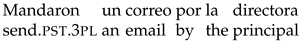

Given this treatment of non-paradigmatic

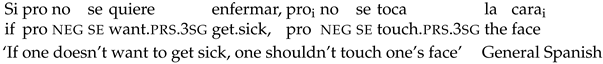

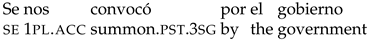

se constructions, one would expect them to pattern like arbitrary plural sentences with respect to by-phrases. This is largely true as referential by-phrases that refer to individuals are unacceptable.

| (36) | ![Languages 09 00024 i042]() |

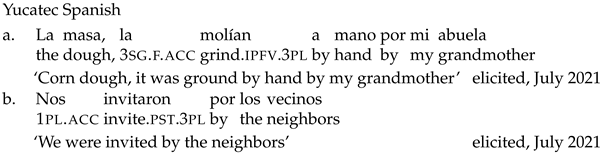

There are, on the other hand, some by-phrases with unspecified readings that either refer to institutions or generically to a type or class of people that are accepted by some speakers.

Pujalte (

2013) and

Ormazabal and Romero (

2019) suggest that the peculiar restrictions on these by-phrases warrant a treatment that is distinct from the agentive by-phrases we see in canonical passives. They are adjuncts that modify an already saturated VoiceP and thus do not identify the initiator in the same way as in a canonical passive or, indeed, a grammatical object passive. Note that A-P hybrids permit a far wider range of by-phrases, suggesting that they are more like passives than non-paradigmatic SE constructions. In (38), repeated from

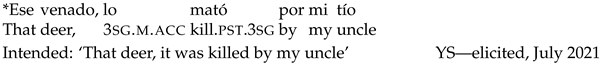

Section 3, we see that by-phrases may refer to specific individuals in A-P hybrids.

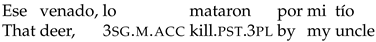

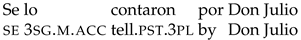

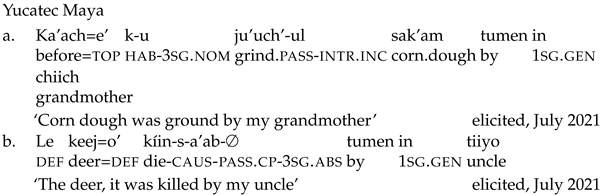

| (38) | Yucatec Spanish |

| | a. | ![Languages 09 00024 i045]() | |

| | | ‘That deer, it was killed by my uncle’ | elicited, July 2021 |

| | b. | ![Languages 09 00024 i046]() | |

| | | ‘It was told to him by Don Julio’ | (Lema 1991, p. 1279) |

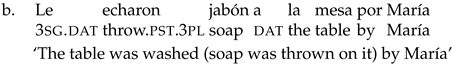

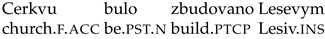

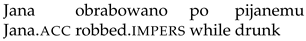

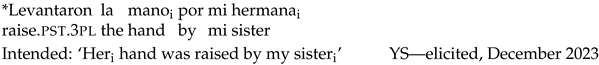

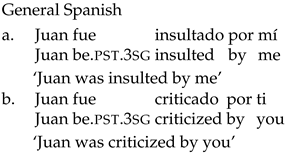

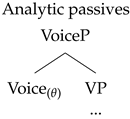

Finally, let us consider analytic passives. Like A-P hybrids, these sentences have no “D” feature in Voice. However, unlike A-P hybrids, they have no specifier and no restriction on potential by-phrases. This means that they are compatible with first- and second-person by-phrases, as shown in (39).

| (39) | ![Languages 09 00024 i047]() |

The lack of restrictions on by-phrases are due to the fact that Voice has an unsaturated and unrestricted initiator role that can be freely modified by an adjunct.

| (40) | ![Languages 09 00024 i048]() |

In conclusion, the range of different impersonal/passive constructions that we observe across different varieties of Spanish can be differentiated based on whether Voice has a specifier and the nature of the pronoun in that specifier. A-P hybrids occupy a unique place in this typology that is slightly distinct from any other existing construction. The last issue that will be discussed concerns how they might have arisen and the potential role that language contact with Yucatec Maya played in causing their emergence.