4.2.1. Biclausality

Let us first consider the hypothesis related to the biclausal nature of the analysed doublings. Claiming that the underlying structure of non-local doubling is (74) implies that between V1 and V2 there are no derivational relations. In fact, we suggest that the duplicated verbs belong to different clausal domains and, as a consequence, V1 and V2 are not related in the syntactic derivation.

The derivational independency between V1 and V2 allows us to explain three of the morphosyntactic properties described in

Section 3.2. V1 and V2:

can have different morphological information and roots,

can establish subject–verb agreement relations independently,

establish argumental relations in different domains.

Concerning the first point above, the data in (22a) and (23a), repeated in (75) below, present the structures in (76).

| (75) | a. | Tenían arroyo tienen ahí |

| | | have.imfv.pst.3pl brook have.prs.3pl there |

| | b. | Entraban hasta las culebras llegaban ahí |

| | | get inside.ipfv.pst.3PL even the snakes arrive.ipfv.pst.3PL there |

| (76) | a. | [CP1 ...tenían... ] [CP2 XPNAi tienen ti ] |

| | b. | [CP1 ...entraban... ] [CP2 XPNAi llegaban ti ] |

The possibility that V2 carries morphological and lexical information that is different from that of V1 is directly related to the

non-at-issue semantic aspect associated with non-local doubling. In accordance with the proposals about RD developed above, CP2 encodes a secondary meaning that corresponds to the semantic background and that, as a consequence, is irrelevant to the truth conditions of CP1.

11 In this respect, CP2 presents metacommunicative information directed to the participants in a particular situation (

Schneider 2015, p. 288). In the case of verbal non-local doubling in PatSp, we argue that the morphological and lexical differences can be explained by means of the semantic nature of CP2 and its possibility of encoding secondary information (in this case, declarations and corrections).

In relation to the second point, a datum such as (26), repeated in (77a), would have the structure in (77b) according to our proposal.

| (77) | a. | Traje tres percas trajimos esa vuelta |

| | | brought.1sg three perches brought.1pl that timeti ] |

| | b. | [CP1 ...traje... ] [CP2 XPNAi trajimos ti ] |

If (77a) actually has the structure in (77b), it is expected that V1 and V2 can establish subject–verb agreement relations in an independent way. The reason for this is that, in our view, CP1 and CP2 present different subjects and, even though features of person and number in both subjects are typically the same (see below), identical manifestation is not obligatory. Along these lines, the structure of (78) could be specified as follows.

| (78) | [CP1 1sg traje ... ] [CP2 XPNAi trajimos 1pl ti ] |

Finally, the third point indicates another relevant behaviour in verbal doublings in PatSp. Since V1 and V2 are part of different clauses, it is expected that both predicates select their arguments independently. In (78), for example, we observe that while the external argument of V1 is 1sg, the external argument of V2 is 1pl.

As we saw in

Section 3.2.3, duplicate verbs are equivalent in argument terms, that is, they select the same number of arguments and assign the same thematic roles. Now, if this is so, it is necessary to explain what happens in CP1. Consider again the structure of (78). Both V1 and V2 are dyadic predicates, so each of them selects two arguments in their clause domains. As shown (79), the argument structure of V1 is incomplete because one of its arguments does not materialise (a situation that we represent by ‘...’ in the data).

| (79) | a. | V1traje → 〈agent = 1sg, ...〉 |

| | b. | V2trajimos→ 〈agent = 1pl, theme = tres percas〉 |

In this paper, we argue that CP1 is an incomplete clause only in appearance. In (79), V1 selects a theme (in addition to an agent), which is semantically and syntactically equivalent to XPNA in CP2, as shown in (80).

| (80) | V1traje → 〈agent = 1sg, theme = tres percas〉 |

One of the reasons for arguing that CP1 is an incomplete clause is the Projection Principle (

Chomsky 1981,

1986), according to which syntactic structure is a projection of lexical requirements, while the subcategorisation properties of lexical pieces must be satisfied. In this sense, if the argument requirements of V1

traje were not satisfied, (77a) would be an ungrammatical sequence, contrary to the facts. In

Section 4.2.3, empirical evidence is offered for this statement.

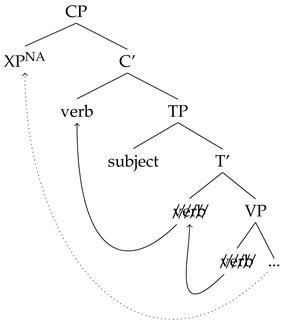

4.2.2. A’ Movement in CP2

Our second hypothesis is that XP

NA moves A’ on the left periphery of CP2. In other words, we assert that in CP2, a process of focalisation takes place. Most of the behaviours described in

Section 3 can be directly accounted for with this claim.

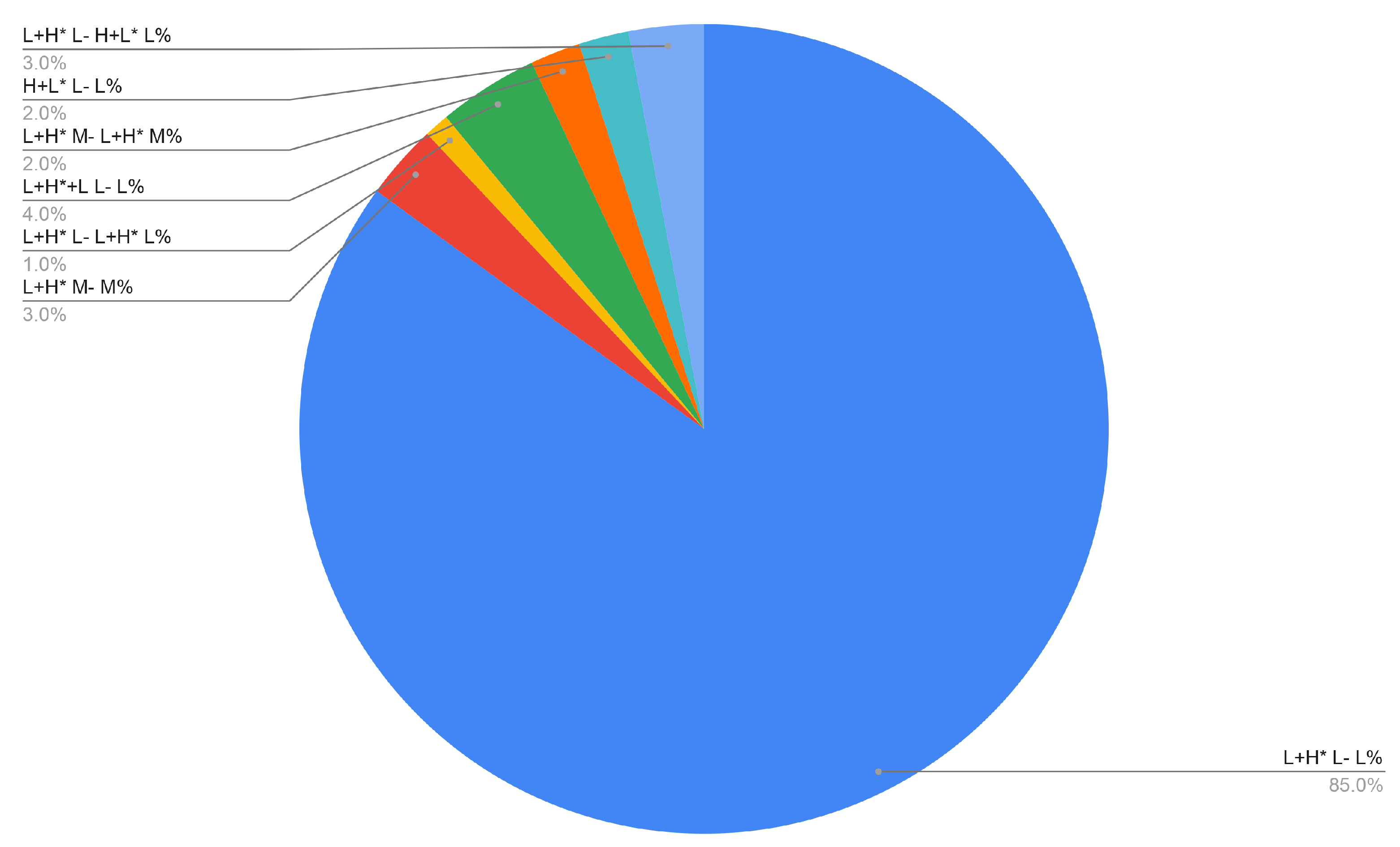

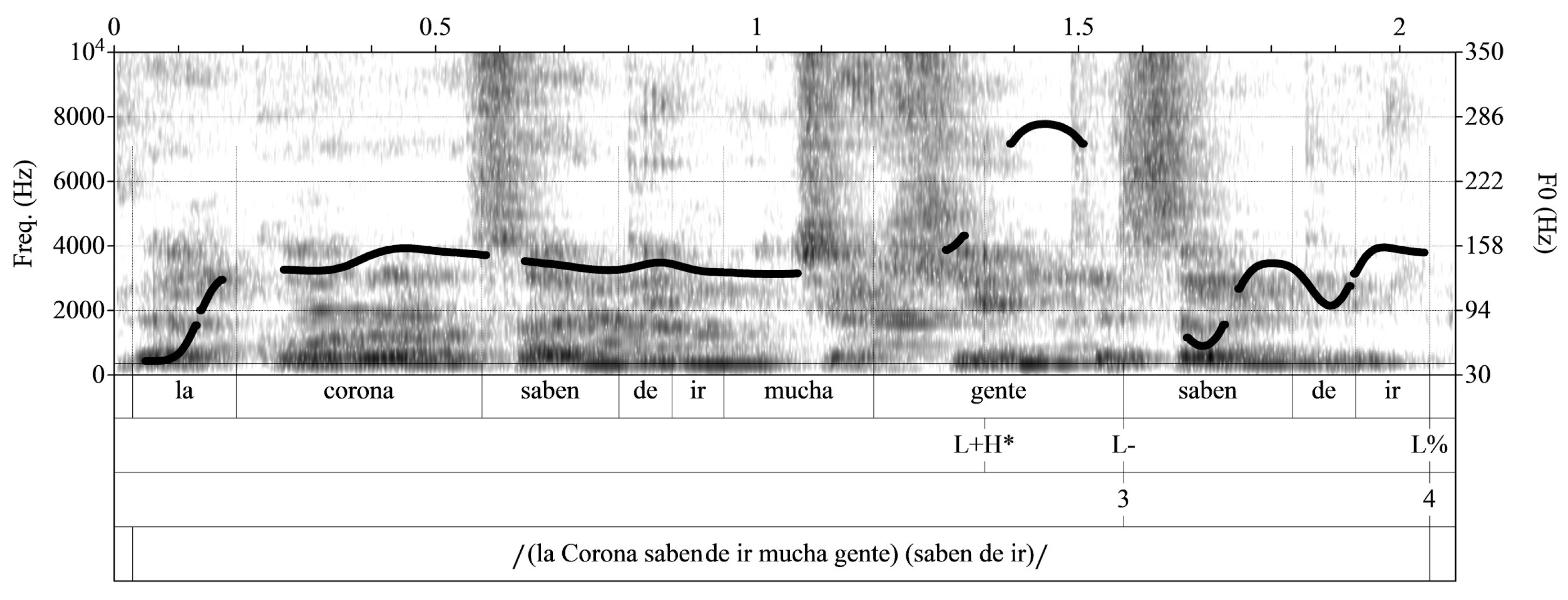

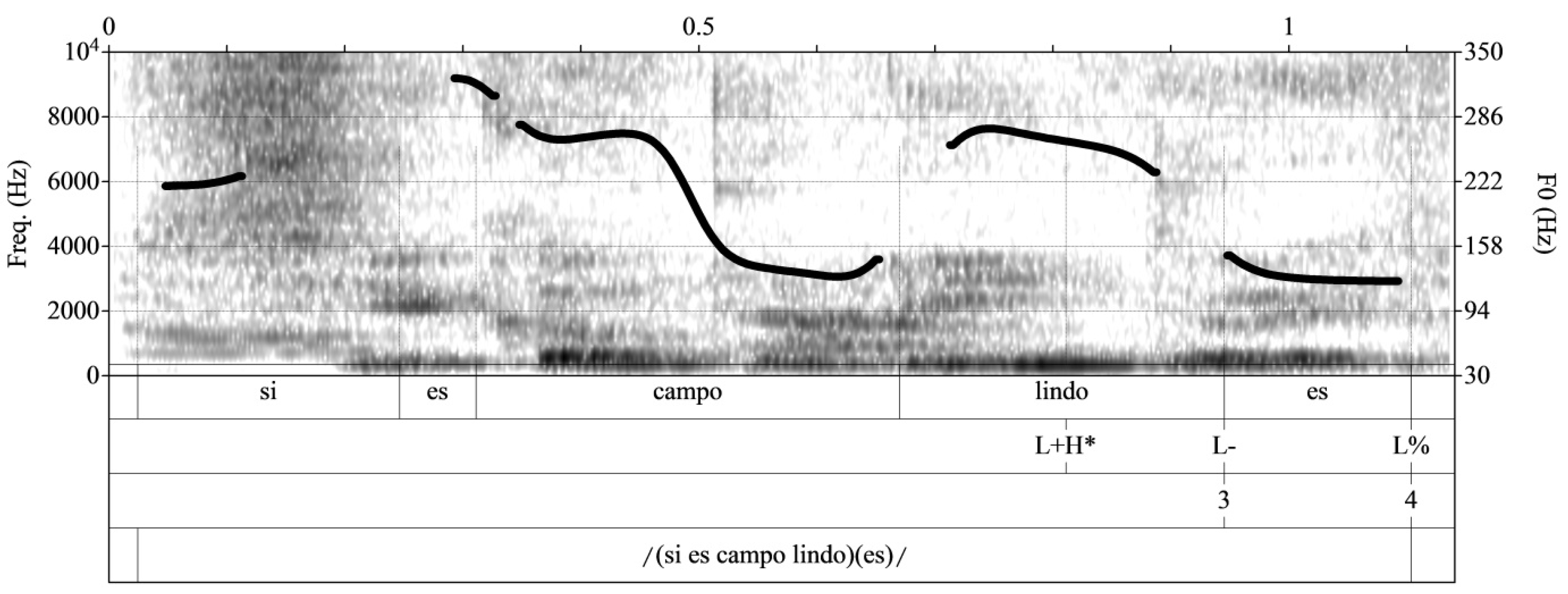

In relation to prosody, one of the characteristics of focalisation is prominence or emphatic stress (

Leonetti and Escandell Vidal 2021, p. 100). In verbal doubling in PatSp, this prosodic trait is manifested with the tonal configuration L+H* L-, in which there is a rising movement followed by an abrupt fall.

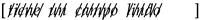

Focalisation of XP

NA, moreover, implies the obligatory adjacency between the NA and V2. This characteristic is directly explained if we assume, together with

Torrego (

1984);

Rizzi (

1996), and related literature, that in the process of focalisation, V rises up to C, similarly to what happens in a

wh- movement. The tree diagram in (81), adapted from

Kotzoglou (

2006, p. 97), illustrates this movement.

| (81) | |

| ![Languages 08 00255 i006 Languages 08 00255 i006]() |

The result of this configuration presents the following order: XPNA-V-subject. The structure in (81) allows us to explain not only the adjacency between the NA and V2, but also the obligatory subject inversion and the impossibility of introducing linguistic material between the NA and V2.

In addition, with respect to the prosodic configuration of

(81), XP

NA and V2 cannot be separated by an interruption in phonation. This behaviour has been pointed out by

Fábregas (

2016) for cases of focalisation in general Spanish. As the minimal pair in (82) indicates, there cannot exist a prosodic break (as represented by comma in (82b)) between the focalised constituent and the verb.

| (82) | General Spanish (Fábregas 2016, p. 33, adapted from his example (109)) |

| | a. A JUAN he visto |

| | to Juan have.1sg seen |

| | ‘I have seen JUAN’ |

| | b. * A JUAN, he visto |

| | to Juan have.1sg seen |

As we can observe in

Section 3.1, verbal doubling in PatSp exhibits the same behaviour.

| (83) | a. / se fueron por Bariloche (*/) se fueron / |

| | refl.3 went.3pl by Bariloche refl.3 went.3pl |

| | ‘I have seen JUAN’ |

| | b. / está cerquita (*/) está / |

| | is really near is |

Leonetti and Escandell Vidal (

2021) suggest that the acceptability of focalisation is questionable in subordinated clauses, as shown in (84).

| (84) | General Spanish (Leonetti and Escandell Vidal 2021, pp. 60–61, their examples (39)). |

| | a. ?? Ella quería que {[el POStre] lleváramos nosotros} |

| | she wanted.3sg that the dessert bring.sbjv.1pl us |

| | b. ?? {Cuando [manteQUIlla] le añades}, sabe mejor |

| | when butter to.it add.2sg taste.3sg better |

| | c. * Pretendía {[con el presiDENte] tener una entrevista} |

| | intended.3sg to with the president have.inf an interview |

As described in

Section 3.2, the same behaviour can be identified in non-adjacent doubling in PatSp. However, the data presented in (44a) and (44b), repeated below, indicate that V2

can appear in cases of subordination.

| (85) | a. | Tenía un campo lindo i creo que {tenía ti} |

| | | have.imfv.pst.3sg a land beautiful believe.1sg that have.imfv.pst.3sg |

| | b. | Venían de Roca i parece que {venían ti} |

| | | come.imfv.pst.3pl from Roca seem.3sg that come.imfv.pst.3pl |

The possibility of V2 subordination, nonetheless, seems to be semantically and syntactically conditioned by the properties of the subordinating verbs. In semantic terms, with verbs such as

creo and

parece in (85), the speaker mitigates his/her commitment on the propositional value of the sequence (expected values due to the

not-at-issue nature of CP2; see

Schneider 2015, p. 287 et seq.). Syntactically, subordinated sentences with verbs such as

creer and

parecer present main clause properties (

Fábregas 2016, Section 6). For example, they allow for the use of speaker-oriented adverbs (86a) and the topicalisation of the verbal phrase (86b).

| (86) | a. | Parece que, {lamentablemente, no van a llegar hasta el sauce} |

| | | Seems that unfortunately not go.3pl to get.inf to the willow |

| | | ‘It seems that, unfortunately, they won’t get to the willow’ |

| | b. | Creo que, {llegar hasta el sauce, no lo lograremos} |

| | | think.1sg that get.inf to the willow not it.acc.m manage.fut.1pl |

| | | ‘I think that, getting to the willow, we won’t manage’ |

The fact that the verbal duplications of PatSp cannot occur in subordination contexts is evidence in favour of the claim that these sequences involve a focalisation process.

It has also been pointed out that focalisation is not compatible with any sentence modality (

Leonetti and Escandell Vidal 2021, pp. 60–61). Sentences that have a focalised constituent cannot occur in interrogative or desiderative sentences, as the examples in (87) show.

| (87) | General Spanish |

| | a. * ¿Cuándo hasta el SAUCE vamos? |

| | when until the willow go1pl |

| | Int. ‘When does until the WILLOW we go?’ |

| | b. * Ojalá que hasta el SAUCE vayamos |

| | hopefully that until the willow go.subj.1pl |

| | Int. ‘I hope that we go until the WILLOW’ |

As we have seen in

Section 3.2, the same behaviours are observed in non-local doubling in PatSp.

In short, there is sufficient empirical evidence to support that in verbal doubling of the studied variety, the XPNA moves to the left periphery of CP2. Now, it is worth analysing how this movement triggers the mirative import associated with sequences that include a duplication.

As we discuss in

Section 3.3, non-local doubling presents two layers of meaning: a propositional meaning,

p, and a secondary meaning,

m. Unlike

p, the semantic value

m is not an asserted content, but an implied one. This means that

m is not obtained compositionally, i.e., it does not arise from the sum of the meanings of the elements that make up the sequence, rather, it is an implicit content systematically encoded in a specific syntactic structure (for an in-depth discussion on the characteristics of conventional implicatures, see

Fernández Ruiz 2015,

2018). In verbal doubling of PatSp, the implicit meaning encoded in the duplication is that

p could be unexpected for the listener.

In

Section 4.1, we discuss the way in which focalisation encodes a mirative semantic value in Italian (

Bianchi et al. 2016), German (

Frey 2010), and Peninsular Spanish (

Cruschina 2019). In this paper, we argue that this reasoning can be applied to the verbal doubling in PatSp.

Let us see an example. In (88), the values

p and

m can be differentiated, as (89) shows.

| (88) | La Corona sabe de ir mucha gente sabe de ir |

| | the Corona know.prs.3sg of go.inf many people know.prs.3sg of go.inf |

| (89) | a. | p = many people use to go to the Corona |

| | b. | m = p (i.e., the fact that many people use to go to the Corona), could be unexpected for you |

We argue that the meanings

p and

m are constructed in different clauses. Specifically, CP1 is responsible for the coding of

p and, in CP2, the focalisation that triggers

m takes place. In (90), this claim is illustrated.

| (90) | [CP1 la Corona saben de ir ...] [CP2 mucha gentei saben de ir ti] |

| | p m |

Let us first consider what happens in CP2. In line with the works by

Krifka (

2007) and

Krifka and Musan (

2012), we understand that focus signals a set of relevant alternatives for the interpretation of the entire sequence. Indeed, in CP2, the focalisation of

many people triggers the set of alternatives M described below.

| (91) |

M={ p1 few people use to go (to the Corona)

p2 a lot of scientists use to go (to the Corona)

p3 a lot of animals use to go (to the Corona)

p4 many people use to go (to the Corona)

…

pn the governor use to go (to the Corona) }

|--focus--| |---background---| |

The members of the set M, that is, the alternative propositions of p, are ordered in line with a probability scale that operates in the listener’s interpretation process, according to the state of knowledge that the speaker attributes to him/her. Thus, for the speaker, the state of knowledge of his/her interlocutor at the moment prior to enunciating the sequence containing the duplication is such that p1 is more likely than p2, p2 is more likely than p3, etc. The value m emerges precisely from the contrast between the order of the alternatives in M and the fact that the alternative that is finally stated is not the most probable option.

The hypothesis of focalisation in CP2, as we have seen, may account for the way in which the additional layer of meaning present in verbal non-local doubling in PatSp arises. This is certainly an advantage of our proposal compared to other analyses that exist in the literature on non-local doubling.

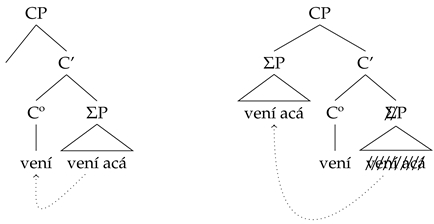

In addition, the hypothesis of focalisation in CP2 allows us to explain one of the fundamental properties of the analysed data: the condition of non-adjacency between the duplicates. In our analysis, the non-adjacency between V1 and V2 is a direct consequence of the movement of XP

NA to the left periphery of CP2, which is required to trigger the characteristic mirative value of duplications. In other words, V1 and V2 are not contiguous because the XP

NA systematically stands between them. Thus, the order V1-XP

NA-V2 described in

Section 3.2 and repeated here in (92a) can be reinterpreted as in (92b) in the light of our proposal.

| (92) | a. | V1 - XPNA - V2 |

| | b. | [CP1 V1 ] [CP2 XPNAi V2 ti ] |

If this analysis is correct, the non-adjacency between the duplicated verbs is not in itself a formal (morphosyntactic or prosodic) requirement for the good formation of verbal doubling in PatSp. Instead, it is a corollary of the way mirativity is encoded in this type of sequence.

4.2.3. On the Prosodic Materialisation of Doublings

To conclude this section, we briefly comment on some aspects related to the materialisation of doubling in PatSp. According to Match Theory, the syntactic structure determines the phonological representation in such a way that the units in Syntax have a direct prosodic correlate. Thus, while constituents are projected into phonological phrases (

), (non-subordinate) clauses are projected into intonation phrases (

).

| (93) | Match Theory (Selkirk 2011, p. 439) |

| | a. | Match clause |

| | | A clause in syntactic constituent structure must be matched by a corresponding prosodic constituent, call it , in phonological representation. |

| | b. | Match phrase |

| | | A phrase in syntactic constituent structure must be matched by a corresponding prosodic constituent, call it , in phonological representation. |

Therefore, Match Theory argues in favour of the following correlation:

If the correlation in (94) is correct, then our data exhibit a paradoxical behaviour. On the one hand, as observed in

Section 3.1, verbal non-local doubling in PatSp is generally expressed in a single IP. On the other, these sequences are made up of two independent CPs, given the ample empirical evidence presented in previous sections. Then, our data seem to go against Match Theory and the one-to-one relation between CP and IP by establishing a reformulation of (94) in the following terms.

One way to resolve this (apparent) paradox is to propose that CP1 is an incomplete clause, because the element that receives the NA is not pronounced (something we express by means of ‘...’ in (90)).

There is empirical evidence to support the claim that in CP1 there is silent material. The following example can be examined, in which the quantifiers ∀ and

three interact.

| (96) | [CP1 todos los albañiles construyeron ...] [CP2 tres casas construyeron] |

| | all the constructors built.3pl ... three houses built.3pl |

The sequence in (96) receives an ambiguous interpretation, as shown in (97).

| (97) | a. | Interpretation 1: |

| | | ∀>three |

| | | ‘For all x, x = constructor, it is true that x built three houses’ |

| | b. | Interpretation 2: |

| | | three>∀ |

| | | ‘There is three houses, such that for all x, x = constructor, three houses were built by x’ |

Where does this ambiguity come from? To answer this question, it is necessary to consider the two clauses that, in our analysis, form the doubling sequences. As can be seen in (98), CP2 only allows the second reading, according to which there are three houses that were built by all the constructors. The first interpretation, however, is not available in CP2.

| (98) | a. | Tres casas construyeron (todos los albañiles) |

| | | three houses built all the constructors |

| | b. | *∀ > tres |

| | | tres>∀ |

If interpretation ∀>

tres is not available in CP2, it follows that it must be available in CP1. This implies that CP1 contains quantifier

tres in the domain of quantifier ∀. A plausible option is that this quantifier is part of the silent material in CP1, as shown in (99).

| (99) | a. | Todos los albañiles construyeron ...[tres] |

| | | all the constructors built ...[three] |

| | b. | ∀ > tres |

| | | tres > ∀ |

In other words, it is possible to affirm that CP1 contains the quantifier tres that makes interpretation 1 possible.

The identity between the silent element in CP1 and XPNA in CP2 must also be syntactic. It can be demonstrated thanks to the categorical selection requirements of the predicates. To illustrate this observation, let us focus on the uses of the verb ganar(se) ’to place oneself’, a typical verb in PatSp.

In a recent work,

Garrido Sepúlveda et al. (

n.d.) provide a detailed description of the grammaticalisation process of the verb

ganar(se) in the Spanish spoken in Chilean and Argentine territory.

According to these authors, the verb

ganar exhibits three well-defined grammaticalisation stages in Chilean Spanish. In the first one,

ganar is used as a transitive verb with the meanings (perhaps the most widespread in the Spanish-speaking world) of ’to acquire some wealth or increase it’, ’to earn a wage or a salary’, or ’to obtain what is disputed in a match, game, contest, election, etc.’. In a second stage,

ganar acquires a pronominal form,

ganarse, and a locative meaning close to ’stay’ or ’take place’. Finally, the most advanced stage of this process is the one in which

ganarse loses (part of) its lexical content and it starts to denote an inchoative value as an auxiliary in an aspectual periphrasis. These values are systematised in

Table 2.

Pronominal uses of

ganarse with a locative value have been registered in PatSp.

Garrido Sepúlveda et al. (

n.d.) point out that

ganarse in this sense can only be combined with adverbial or prepositional phrases. The data in (102) are anomalous because, despite denoting location, the complement of

ganarse is an AP, NP, or DP.

| (100) | Ganate más cerca/debajo de la parra |

| | take your place near/under the vine |

| | ‘Get closer/under the vine’ |

| (101) | a. | Mi gata se ganó en el sillón y se quedó ahí toda la tarde |

| | | my cat refl sit in the couch and refl stay there all the afternoon |

| | | ‘My cat sat down in the couch and she stayed there during the evening’ |

| | b. | ¡Gánense en/a la sombrita! |

| | | stay.refl in/to the little.shadow |

| | | Stay away from the sun! |

| (102) | a. | * Ganate [Adj cercano] |

| | | get close |

| | b. | * Ganate [N biblioteca] |

| | | get library |

| | c. | * Nos ganamos [DP un costado] |

| | | We got a side |

With this in mind, let us resume our discussion on verbal doubling in PatSp. In the case of (103), in which the verb

ganarse is duplicated, there is only one interpretation available: that of

ganarse as a locative verb. This means that both V1 and V2 must be assembled with a PP/AdvP. The conclusion then is that, in CP1, ‘...’ is a PP/AdvP.

| (103) | Nos ganamos en esta orilla nos ganamos |

| | take our place in this side take our place |

| | Int. OK: We placed ourselves on this side and I understand that it sounds surprising to you. |

| | Int. *: We won X and we placed ourselves on this side; I understand that it sounds surprising to you. |

| (104) | [CP1 nos ganamos [PP ...]] [CP2 [PP en esta orilla ] nos ganamos] |

| | take our place in this side take our place |

In short, there seem to be reasons that justify the assertion that a silent XP occurs on the right margin of CP1 with the same semantic values and the same syntactic nature as the XP

NA of CP2. This is shown in (105).

| (105) | [CP1 V1 [XP ... ]] [CP2 XPNAi V2 [TP ti]] |

The fact that a silent element occurs in CP1 is the reason why verbal non-local doubling in PatSp materialises as a single IP. The reasoning is the following. According to

Zubizarreta (

1998), the NA is assigned by default through c-command relationships. Specifically, the NA is received by the constituent that is most embedded in the syntactic structure and, given

Kayne’s (

1994)

Axiom of Linear Correspondence, it is also the constituent that occurs in the right edge of the clause. This rule is known as the

Nuclear Stress Rule.

| (106) | Nuclear Stress Rule (Zubizarreta 1998, p. 38) |

| | The lowest constituent in the asymmetric c-command ordering in the phrase is the most prominent in that phrase. |

In this sense, the two CPs ⟺ one IP correlation exhibiting non-local doubling in PatSp could be explained from the incompleteness of CP1. In other words, CP1 cannot be materialised as an independent IP because the most embedded constituent in CP1, i.e., the one that should receive the NA, is not phonetically realised.

12 Juan]

Juan]

]

]