Abstract

This study takes us to the Greek diasporic community in Cairns, Far North Queensland, Australia. The data analyzed derive from audio-recorded conversations with first-generation Greek immigrants collected during fieldwork in 2013. Drawing on interactional linguistics and contact linguistics, this paper analyzes the prosody of bilingual discourse markers and bilingual repetition in Australian Greek talk-in-interaction. It is shown that the prosodic features of code switches, namely pitch, intensity and duration, shape action formation and ascription. In the case of bilingual discourse markers, pitch serves as a contextualization cue that conveys the speaker’s stance and frames the different functions of the code-switched items. In bilingual repetition, speakers mobilize duration and intensity to prosodically differentiate the first iteration delivered in English from the second iteration delivered in Greek and, thus, frame the interpretation of the code switch as participant-related. This study sheds light on the pragmatic aspects of the phonetics of the Greek variety spoken in Cairns, and demonstrates that prosody shapes the functions of language contact-induced speech behavior in specific interactional contexts.

1. Introduction

This paper examines the role of prosody in action formation and ascription in Australian Greek, namely by exploring how prosody shapes the interpretation of the actions implemented via code switches. This study targets the small Greek diasporic community living in Cairns, a tropical remote city of Far North Queensland, Australia. The first Greeks arrived in Queensland at the end of the 19th century and worked in the cotton and sugar cane industry, as well as on tobacco plantations (Tamis 2005). Big waves of migration followed after World War II, in the 1960s, 1970s, and in the early 1980s.1 The Greek community in Cairns consists of three generations: (i) first-generation Greeks, who were born and raised in Greece and arrived in Australia after their adolescence; (ii) second-generation Greeks,2 who were born in Australia to first-generation Greeks or born in Greece and arrived in Australia in their preschool or early primary school years; and (iii) third-generation Greeks, who were born in Australia to second-generation Greeks. This study focuses on first-generation Greeks (50–90 years old), who form a linguistic minority that became bilingual in the dominant host group (i.e., the English-speaking community) and maintained their native language. First-generation Greeks use Greek to communicate with spouses, children, and friends from their ethnic group, maintain contact with Greece on a regular basis, participate in ethnically homogeneous friendship networks, and consider the maintenance of Greek an essential part of preserving Greek cultural heritage and ethnic group identity.

In the community of Cairns, the Greek language is maintained with minor contact-induced changes, such as lexical borrowings (Alvanoudi 2018, 2019). Language alternation from Greek to English, also known as code switching, occurs between utterances delivered by different speakers or within the same speaker utterance, and is common among first-generation Greeks. Three types of code switching are relevant to the current study (cf. Auer 1995, 1998): (i) discourse-related or conversational code switching, which is interactionally motivated and locally meaningful; (ii) participant-related code switching, which is associated with speakers’ competence and preference in the two languages in question; and (iii) momentary intra-clausal switches or insertions that do not change the language of the interaction and do not carry any locally defined meanings, i.e., they constitute a ‘discourse mode’ (Poplack 1980, p. 614) that is common for the members of the speech community examined here (for a detailed discussion, see Alvanoudi 2019).3 In my previous work, only passing attention has been paid to the prosody of code-switched items. The current study aims to shed light on the role of prosody in differentiating the functions of code switching in Australian Greek talk-in-interaction, focusing on two language contact-induced phenomena: bilingual discourse markers and bilingual repetition.

1.1. Some Theoretical and Methodological Preliminaries

Discourse markers (also known as ‘pragmatic markers’ or ‘pragmatic particles’) are small, uninflected words or phrases that are relatively syntactically independent from their environment, routinely occur in oral speech, have little or no propositional meaning, and display textual and interpersonal pragmatic functions (e.g., Fischer 2006; Schiffrin 1987). Discourse markers are among the most commonly borrowed or code-switched items in language contact situations due to formal linguistic, interactional and social factors (Heine et al. 2021, pp. 219–29). Namely, discourse markers are “easy both to identify in text material of the donor language and to integrate in the receiver language” (Heine 2016, p. 254), because they are frequent in oral speech, detachable from the content message of the utterance (Matras 2009, p. 193) and their form is short and formulaic (Heine 2016, p. 254). Also, discourse markers are easily borrowed due to their emblematic status (Goss and Salmons 2000; Poplack 1980) and their local communicative functions (Maschler 1994; Matras 1998). In the Greek variety spoken in Cairns, English discourse markers enter as momentary code switches and maintain the pragmatic functions they have in English.

The second language contact-induced behavior examined in this study is bilingual repetition. In bilingual conversation, speakers often deliver self-repeats in two different languages; that is, they repeat a message that was initially delivered in one language in a different language. This type of self-repetition is known as ‘doubling’ (Muysken 2000, pp. 104–5), ‘coupling’ (Tsitsipis 1998, p. 74), ‘lexical/grammatical parallelism’ (cf. Aikhenvald 2006, p. 25) or ‘pseudo-translation’ (Auer 1984, p. 88). Such repeats maintain the original referential meaning of the first iteration and may be triggered by participants’ preferences for the two languages in question (Auer 1984, pp. 90–91) or carry conversational functions, such as adding emphasis (Auer 1984, p. 90) or evaluating narratives of personal experience (Tsitsipis 1983, p. 33). Bilingual repetition is found in Australian Greek talk-in-interaction, when speakers translate English lexical items into Greek without modifying their original referential meaning.

To sum up, prior research in language contact has shed light on the functions of bilingual discourse markers and bilingual repetition; yet, the role of prosody in shaping the functions of these language contact-induced phenomena is still not well understood. The present study aims to partly fill in this gap, bringing to light original data from a Greek diasporic community. The methodological framework deployed in this study is conversation analysis-informed interactional linguistics, that is, an empirical, data-driven approach to the investigation of language, as used in social interaction, that combines the sequential analysis of naturally occurring talk-in-interaction with a linguistic analysis of the lexico-semantic, morpho-syntantic, and prosodic means mobilized in conversational sequences (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting 2018). Interactional linguistics targets the relation between practices and actions, namely by examining the recurrent ways in which verbal and other resources, such as prosody, are used for the purpose of asking/answering, assessing/agreeing or disagreeing, and requesting/complying or non-complying, among others (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting 2018). In this framework, prosody is understood to encompass “all suprasegmental phenomena that are constituted by the interplay of pitch, loudness, duration and voice quality […] as long as they are used—independently of the language’s segmental structure—as communicative signals” (Selting 2010, p. 5; following Firth 1957).

Prosody is key in organizing interaction and recognizing actions. Each action is delivered in a distinct prosodic phrase, known as an intonational unit, uttered “under a single coherent intonation contour” (Chafe 1980, 1993; Du Bois et al. 1993, p. 47) that signals the boundary of the intonational unit and its relation to other units. As Selting (2010, p. 6) observes, in spoken language, prosody always co-occurs with grammar and lexis in utterances, and thus, is “co-constitutive in the expression and achievement of interactional meaning.” A number of studies have demonstrated the role of prosody in conveying the speaker’s stance (e.g., see Reber 2012; Selting 1996 on surprise; Szczepek Reed 2006 on affiliation with prior talk; Korpela et al. 2023 on apology sequences) and structuring information (e.g., Couper-Kuhlen 2004). For example, Selting (1996) reports that German speakers mobilize high pitch or extra loudness to initiate repair that deals with problems of expectation, and Couper-Kuhlen (2004) shows that English speakers deploy high pitch accents to introduce information at the beginning of a new sequence/topic.4 Prosody is shown to have a contextualizing function (Gumperz 1982), as it offers frames for the interpretation of utterances. According to Couper-Kuhlen and Selting (1996, p. 21), prosodic contextualization cues “stand in a reflexive relationship to language, cueing the context within which it is to be interpreted and at the same time constituting that context.” Following this line of research, the current study examines how the prosodic features of code switches in Australian Greek talk-in-interaction influence inferred meanings associated with the speaker’s stance and information packaging and contribute to action formation.

1.2. The Linguistic Profile of Greek

A short description of the linguistic profile of Greek is useful contextualization for the current study. Greek belongs to the Indo-European group of languages and is a fusional, highly inflecting language in which several grammatical categories are marked morphologically; for example, nouns inflect for gender, number and case, and verbs inflect for person, number, tense, aspect, voice, and mood. It is a pro-drop language with a flexible word order (descriptions of the language are in Holton et al. 2012; Mackridge 1985). According to Arvaniti (1999), the phonologically contrastive consonants of Greek include the bilabials/p/,/b/,/m/, the labiodentals/f/,/v/, the interdentals/θ/,/ð/, the alveolars/t/,/s/,/d/,/z/,/n/,/ɾ/,/1/, and the velars/k/,/x/,/g/,/ɣ/. Greek has a typical five-vowel system:/i e a o u/. It distinguishes unstressed and stressed (i.e., commonly accented) syllables, with the latter showing greater acoustic prominence (i.e., longer duration and/or higher amplitude) and more peripheral vowel quality (Arvaniti 1994; Arvaniti and Baltazani 2005; Baltazani 2007a). In terms of suprasegmental features relevant to the examples analyzed in Section 3, Greek declaratives normally end in a fall that may include a final stretch of low fundamental frequency (F0), represented as L- L% (Arvaniti and Baltazani 2005, drawing on the Autosegmental–Metrical framework of intonational phonology, cf. Ladd 1996). The default intonation of Greek polar questions consists of a rise–fall at the end of an utterance and is autosegmentally represented as L* L+H- L% (Arvaniti et al. 2006; Baltazani 2007b; for an alternative view, see Papazachariou 2004). The default intonation of Greek wh-questions consists of a rise–fall followed by a low plateau and a final rise (Arvaniti 2001; Arvaniti and Ladd 2009). Readers interested in further background on Greek phonetics are referred to Arvaniti (2007).

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

The data analyzed derive from 16 h of audio-recorded interviews and informal face-to-face conversations with 11 first-generation Greek immigrants that I collected during fieldwork in 2013. Three speakers5 (two females and one male) between the approximate ages of 89–60 years at the time of recording compose the pool of participants analyzed in the present study, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The cohort.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

During fieldwork, I became a member of the Greek community and immersed myself in daily life. Data were recorded in arranged meetings and cultural activities at the St. John Parish of Cairns or during dinners and lunches at the informants’ houses, where I was a guest. I put the digital audio recorder on a table and I invited informants to share their life stories, and talk about the history of the Greek community in Cairns or any other topic. Data were fully transcribed following conversation analytic conventions (cf. Jefferson 2004; an abbreviated representation of transcription conventions, following Couper-Kuhlen and Selting 2018 is in Appendix A).

For the data analysis, I deployed the tools of conversation analysis-informed interactional linguistics (see Section 1.1); the analytical practice regarding the study of prosody in naturally occurring conversation can be found in Szczepek Reed (2011). For the acoustic analysis of my natural speech samples, I used PRAAT software (Boersma and Weenink 2019). I analyzed audio files (stored in WAV format) that did not contain intense background noise or overlapping talk with other participants, and I removed speech material and pauses, preceding or following the immediate object of interest (i.e., the discourse marker or the bilingual repeat), from the audio files under analysis. The stretches of speech in audio files were kept as short as possible to allow for a clear representation of detail in the analysis. I measured and represented prosodic details that were relevant to the participant’s action in the given conversational context, namely pitch, intensity and duration. For pitch, I used a default window analysis of 50–500 Hz (in Figures 1, 2, 4, 5, 6), because the speech analyzed originated from speakers of different age and gender, and high levels of emotion were often involved in the recorded conversations (cf. Szczepek Reed 2011, p. 26). In Figure 3, the window has been shortened to 30–200 Hz, because there is a mismatch between the F0 value represented by PRAAT, which is very low, and the value that we perceive when we listen to the original recording, which is slightly higher. I used a logarithmic representation of speech that represents more clearly a human perception of the pitch curve in question, and I added a text tier to the pitch analysis to align the pitch curve with the words of the spoken text. The prosody7 of bilingual discourse markers and bilingual repetition is examined in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. The Prosody of Bilingual Discourse Markers

Greek immigrants insert English discourse markers in their speech. The occurrences and type of discourse marker per speaker are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

English discourse markers per speaker.

In using English discourse markers, Greek speakers transfer communicative patterns or ‘practice–action pairs’ in specific interactional contexts. As shown in this section, the prosodic configuration of the code-switched discourse marker is important for the interpretation of the action carried out by this item in talk-in-interaction.

Let us begin with the code-switched item no. Extract (1) comes from a conversation between Petroula, a first-generation Greek female, and the researcher at Petroula’s house. Petroula has offered the researcher homemade cake.

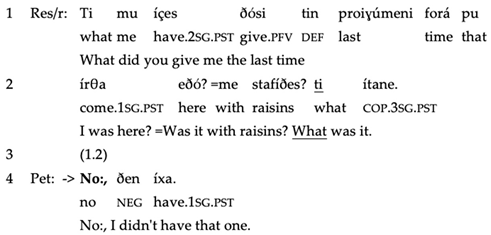

(1)

In line 1, the researcher uses a question-word interrogative to ask about the type of cake that Petroula gave her during her last visit. In line 2, she offers the participant a candidate answer via a polar question (Pomerantz 1988) (‘Was it with raisins?’) and requests the same piece of information via another question-word interrogative (‘What was it?’). Petroula’s response is in line 4, where she uses the negative response token no to minimally disconfirm the proposition put on the conversational table by the researcher’s polar question and deploys the negative clause ðen íxa (‘I didn’t have that one’) to overtly disconfirm the question’s proposition. As shown in Figure 1,8 Petroula delivers no with her default pitch register/local pitch span9 in this conversational episode; mean F0 is around 227 Hz.

Figure 1.

F0 of no in line 4 of (1).

This prosodic configuration changes when no is used in a different sequential position. Extract (2) comes from another conversation between Petroula and the researcher (first analyzed in Alvanoudi 2019). Petroula has offered the researcher cookies, and the researcher has told her that she also brought biscuits to share. In lines 1–2, the researcher announces that she will get the biscuits from her bag.

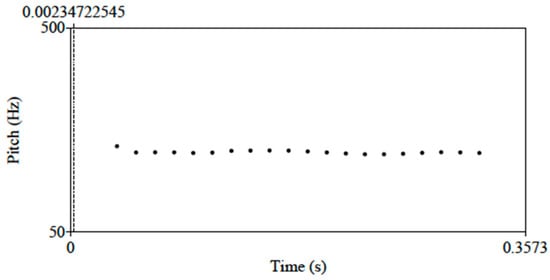

(2)

In lines 4 and 6, Petroula commands the researcher to not get the biscuits. She starts her turn in Greek, using the imperative mood with a sharp intonational rise and increased loudness (↑MI VGÁLIS ‘don’t take’). After a cutoff (ΤA- ‘the-’), the speaker continues her turn in English. She repeats the negative token no and the imperative leave it there with the same F0 and loudness throughout. The researcher complies with the command and returns to the table. Petroula uses a number of practices to display high entitlement, or her strong rights to impose her will on the recipient’s future behavior (cf. Stevanovic and Peräkylä 2012): the imperative form, repeating no, and code switching, which creates a contrast between the established language of interaction (i.e., Greek) and what follows the point marked by the switch (i.e., English), and carries communicative value (see Section 1). The prosodic configuration of no from (2) is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

F0 of no no no no no in line 4 of (2).

Unlike Extract (1), in Extract (2), the speaker adopts a higher pitch level (mean F0 is around 312 Hz) to utter the code-switched item no, and thus, she departs from her default pitch register. This prosodic feature serves as a contextualization cue that frames the different function of this negative token in terms of the speaker’s deontic stance. In both extracts, the negative response tokens consitute intonation units, or prosodically coherent segments of speech that implement a recognizable action. Yet, the action performed in each case differs based on the response token’s prosody and sequential position.

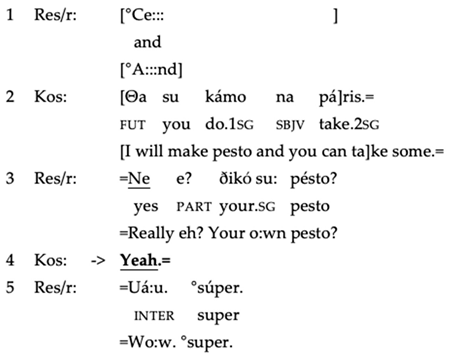

Prosody can also differentiate the communicative import of affirming/confirming answers to polar questions in terms of the speaker’s epistemic stance. In Extracts (3) and (4), Kostadina, a first-generation Greek female, uses the English particle yeah in a responsive position after a polar question. Polar questions indicate epistemic asymmetry between interlocutors, as questioners usually request information that falls into the respondents’ epistemic domain (cf. Heritage 2012). Respondents use different formats to convey their positioning toward the questioner’s epistemic stance and the proposition in question. For example, in English conversation, speakers use particles such as yes/yeah to “accept the terms of the question unconditionally, exerting no agency with respect to those terms, and thus acquiescing in them” (Heritage and Raymond 2012, p. 183; Raymond 2003). In the lines preceding Extract (3), Kostadina told the researcher that her husband got sick and died on a South Pacific island about thirty years ago.

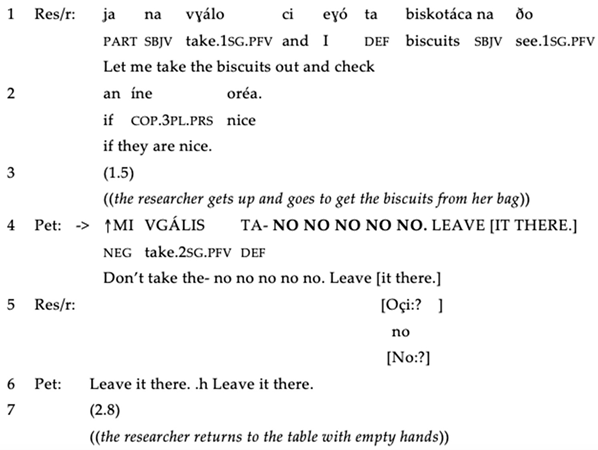

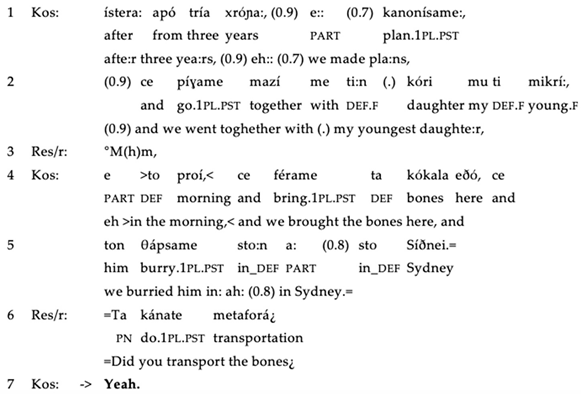

(3)

In lines 1–2 and 4–5, Kostadina informs the researcher that she and her daughter went to the island to transport her husband’s bones to Sydney. In line 6, the researcher requests confirmation of the action being performed by Kostadina and her daughter. The question (‘Did you transport the bones?’) positions the respondent as more knowledgeable [K+] and “construes the questioner as partly in the know,” given that “the information provided in the response is not treated as wholly new” for the questioner (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting 2018, p. 238). In line 7, Kostadina simply confirms with the token yeah, assuming an epistemically [K+] position and accepting the epistemic terms of the question. The mean pitch value of yeah is around 55 Hz. The F0 trace can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

F0 of yeah in line 7 of (3).

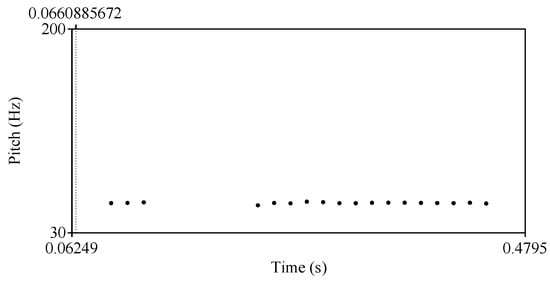

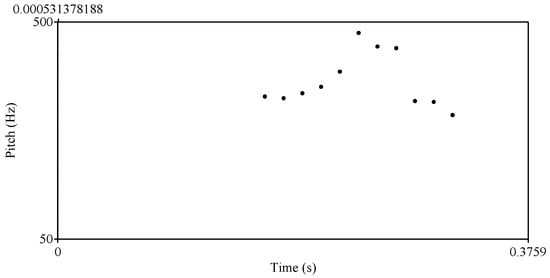

Extract (4) comes from the same conversation between Kostadina and the researcher. In the preceding lines, Kostadina offered to make pesto sauce for the researcher and listed the ingredients required for the recipe.

(4)

In line 2, Kostadina repeats the offer, and in line 3, the researcher initiates a repair sequence. In the first-turn constructional unit, she uses a surprise token (‘really eh?’) that seeks confirmation, and in the second-turn constructional unit, she uses a polar question that displays her surprise or disbelief, as shown by the prosodic realization (i.e., higher F0 around 275 Hz) of the turn (Selting 1996), seeks confirmation about the object being proffered, and positions the respondent as [K+]. In line 4, Kostadina emphatically confirms with the particle yeah, delivered contiguously (i.e., without any inter-turn gap or turn initial delay) and with a higher F0 (around 377 Hz). The polar answer provides the confirmation requested and accepts the epistemic terms of the question. At the same time, the polar answer embraces the surprise expressed by the questioner. The respondent mobilizes prosodic resources, such as a higher F0, to convey a congruent evaluative stance. In line 5, the researcher accepts the offer with enthusiasm. The F0 trace of the token yeah in Extract (4) is visible in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

F0 of yeah in line 4 of (4).

As we can see in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the pitch of yeah in (4) is significantly higher than the pitch of yeah in (3). This prosodic variation shapes subtle aspects of the action carried out. The speaker uses yeah with low F0 to simply confirm the proposition in question and uses yeah with higher F0 to convey a congruent evaluative stance besides confirming the question’s proposition. In other words, the prosodic configuration of the positive response token conveys the respondent’s stance toward the question and the action it implements.

To sum up, the analysis shows that F0 configurations play a key role in the interpretation of actions implemented by code-switched discourse markers. In the next section, I examine whether prosody can help us understand the fuzzy functions of bilingual repetition in Australian Greek.

3.2. The Prosody of Bilingual Repetition

The bilingual self-repeats found in the data do not carry the communicative value associated with specific local functions and seem to be associated with the speaker’s preference for Greek monolingual talk (Alvanoudi 2019). In this section, I show that the prosodic features of bilingual self-repeats provide further support for their interpretation as participant-related code switches.10

The five cases of bilingual repetition found in the data (Minas: 3; Petroula: 2) occur in the predicate of a clause and occupy the slot of a copula complement or core argument (O ‘transitive object’) that introduces a piece of ‘new’ information, which the speaker assumes the hearer does not know (i.e., it is non-pragmatically presupposed; cf. Lambrecht 1994). The acoustic analysis of the data yields a recurrent pattern, that is, the first iteration of the self-repetition is prosodically more prominent than the second, as it is uttered with greater intensity or more slowly. I examine two indicative examples below.

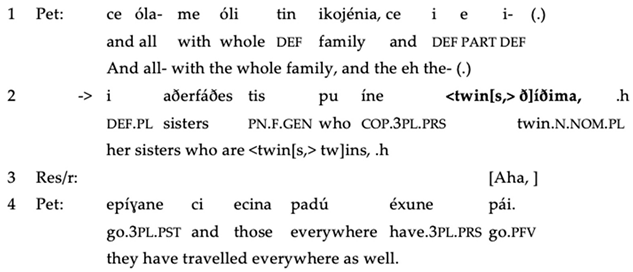

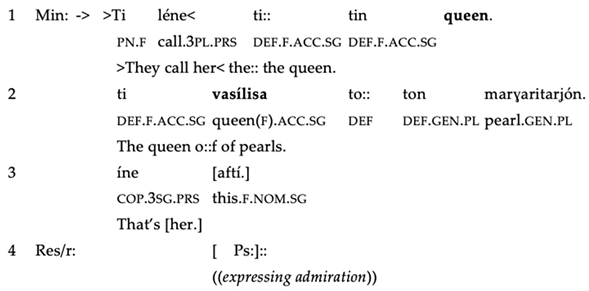

(5)

In Extract (5), Petroula refers to her granddaughters via the noun phrase i aðerfáðes tis (‘her sisters,’ line 2) and uses a relative clause with a copula construction to modify the noun (pu íne <twin[s,> ð]íðima, ‘who are twins, twins’, line 2). In the copula complement, the speaker first inserts the English item twins and then repeats the item in Greek (ðíðima). The acoustic display of the repeated items is in Figure 5. Both words are produced with similar intensity (around 70 dB)11 and a rise-to-high F0, as they begin at around 200 Hz and rise to around 300 Hz. Yet, as depicted in the waveform, the word twins occupies more time than the word ðíðima, that is, the speaker mobilizes prosodic resources to assign more prominence to the first iteration, which introduces new information. Therefore, the code switch found in the second iteration is not interactionally motivated, as it does not serve to highlight the referents’ twin relationship, but rather displays the speaker’s preference for Greek as the appropriate language of interaction.

Figure 5.

Waveform, F0, and intensity of twins, ðíðima in line 2 of (5).

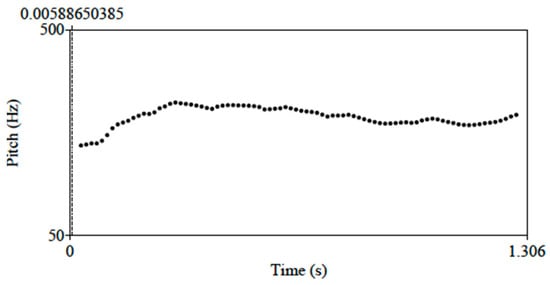

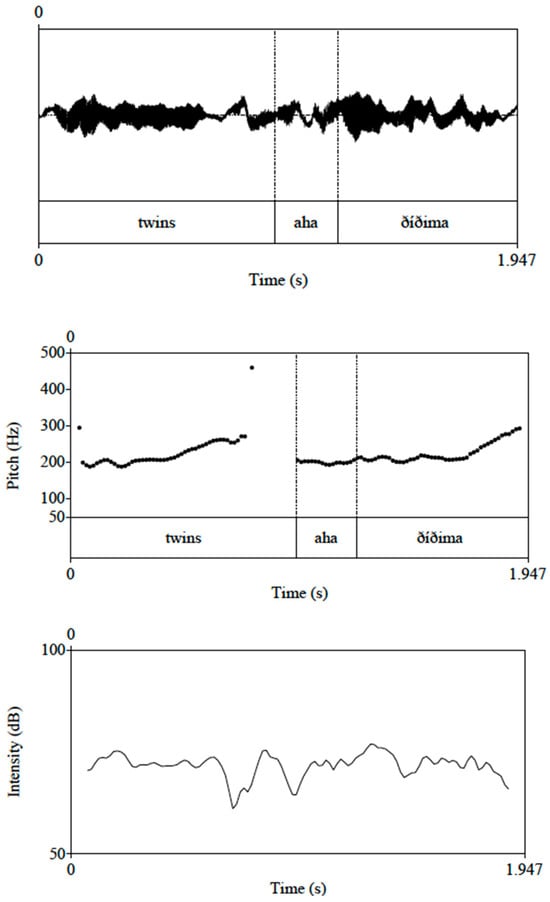

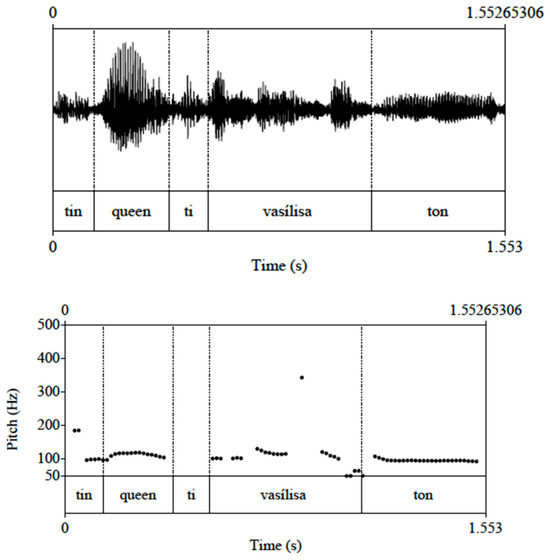

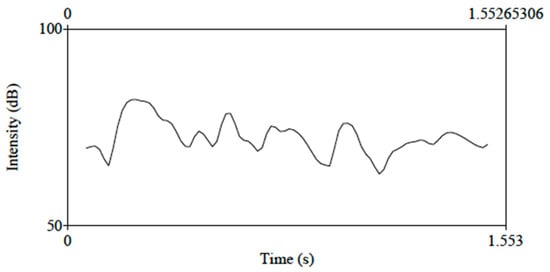

A similar case is in Extract (6). In the preceding lines, Minas, a first-generation Greek male, has mentioned a wealthy Greek woman who lives in northern Australia.

(6)

In lines 1–2, Minas informs the researcher that this woman is known as the queen of pearls. The core argument is a noun phrase with a hybrid structure, that is, it consists of the Greek definite feminine article ti and the English noun queen. In the next-turn constructional unit, the speaker repeats the noun in Greek (vasílisa). As we can see in Figure 6, the phrases tin queen ti vasílisa are delivered at a relatively level pitch throughout, but the word queen is uttered with greater intensity (78.06 dB) than the word vasílisa (72.45 dB). The stressed syllable queen is visible as the most prominent in the waveform (i.e., as an increase in air pressure). In sum, the speaker uses acoustic cues to assign more prominence to the first iteration and to highlight the attribute given to the referent. The code switch from English to Greek does not create a contrast that highlights new information, but rather orients toward the ‘language otherness’ of the initial lexical item and signals the speaker’s preference for Greek monolingual talk.

Figure 6.

Waveform, F0, and intensity of queen, vasílisa in lines 1–2 of (6).

In Extracts (5) and (6), bilingual repetition is shown to consist of two iterations in Greek and English, which are prosodically differentiated. Although the referential meaning of the second iteration remains the same, its prosodic configuration changes, thus shaping the function of the repeat. In both cases, speakers draw on prosodic features to mark a piece of information as not new in the midst of a telling.

4. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

To date, studies on language contact situations have examined how language contact affects the manifestation of the phonology and phonetics of minority languages (see Rao 2020). The current study takes a different path, as it sheds light on the pragmatic aspects of the phonetics of the Greek variety spoken in Cairns, Australia. More specifically, the study builds on prior research on bilingual discourse markers and bilingual repetition, and demonstrates that prosody contextualizes the functions of the latter language contact-induced phenomena in specific interactional contexts in real-life conversation.

As shown in Section 3.1, prosody contributes to the interactional meaning expressed via English discourse markers in Australian Greek talk-in-interaction; that is, Greek immigrants mobilize both verbal and prosodic resources for displaying their stance when providing positive or negative answers to polar questions or when asking someone to do something. Whether speakers also ‘copy’ the distinctive prosodic properties possibly associated with these items in Australian English talk-in-interaction remains to be established in the future. Moreover, as shown in Section 3.2, prosodic features provide frames for the interpretation of bilingual self-repetition as delivering ‘old’ rather than ‘new’ information. Prosodic prominence differentiates the ‘foreign’ saying from the ‘native’ one and guides analysts to interpret the bilingual self-repeat as an instance of participant-related code switching that displays the speaker’s preference for Greek monolingual talk. To sum up, the analysis of prosodic resources can help us understand how code switching becomes pragmatically meaningful in Australian Greek talk-in-interaction.

Overall, the findings reported in this study indicate that prosody shapes the functions of language contact-induced speech behavior and provide further support for a context-sensitive analysis of prosody in line with the interactional linguistic approach. Given the small sample of data analyzed in this study, we cannot draw any definite conclusions about whether the specific prosodic resources examined form practices used recurrently for the implementation of polar answers, directive actions or information packaging in Australian Greek talk-in-interaction. Thus, the contribution of this study to our understanding of the prosodic realization of specific actions remains limited.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly improved the quality of this paper. X. All remaining errors are my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

1—first person; 2—second person; 3—third person; acc—accusative; cop—copula; def—definite; gen—genitive; inter—interjection; m—masculine; f—feminine; n—neuter; neg—negation; nom—nominative; part—particle; pfv—perfective; pl—plural; pn—pronoun; prs—present; pst—past; sg—singular; sbjv—subjunctive

Appendix A

Transcription conventions

| [ | point of onset of overlap |

| ] | point of end of overlap |

| = | latching |

| (0.8) | silence in tenths of a second |

| (.) | micro-pause (less than 0.5 s) |

| . | falling/final intonation |

| ? | rising intonation |

| ¿ | rise stronger than a comma but weaker than question mark |

| , | continuing/non-final intonation |

| : :: | sound prolongation or stretching; the more colons, the longer the stretching |

| word | underlining is used to indicate some form of emphasis, either by increased |

| loudness or higher pitch | |

| ° | following talk markedly quiet or soft after a word or part of a word: cut-off or interruption |

| ↑ | sharp intonation rise |

| > < | talk between the ‘more than’ and ‘less than’ symbols is compressed or rushed |

| < > | talk between the ‘less than’ and ‘more than’ symbols is markedly slowed or |

| drawn out | |

| h | hearable aspiration; its repetition indicates longer duration |

| .hh | inhalation |

| (( )) | transcriber’s description of events |

Notes

| 1 | In 1996, Greek was the sixth most widely used community language spoken in Australia, after Arabic, Cantonese, Croatian, Dutch, and German (Clyne 2003). According to the 2016 Census (Australian Bureau of Statistics), 237,588 out of the 397,431 people of full or partial Greek ancestry living in Australia reported that they spoke Greek at home. |

| 2 | Second-generation Greeks in Cairns are the offspring of the Greeks who settled in Australia in the early 20th century and after World War II. |

| 3 | Turn-internal switches that do not allow the identification of the language of interaction were not found in the data on which the current study is based, and thus, are not discussed here. |

| 4 | Prosody has multiple functions: see e.g., Auer (1996) on turn expansion; Fox (2001), Local and Walker (2012), and Selting (2000) on turn projection, Couper-Kuhlen (1996) on differentiating repetition from mimicry of an interlocutor’s prior contribution and Local et al. (2010) on re-launching activities that failed to be successful at first try. |

| 5 | The data analyzed are indicative of the patterns found in the speech of first-generation Greeks in Cairns. |

| 6 | Speakers are given pseudonyms. |

| 7 | Speaker’s age does not seem to influence the discourse function of prosody during code switching. |

| 8 | All graphs are extracted with PRAAT. |

| 9 | Following Szczepek Reed (2011, p. 89), pitch register is understood as “a participant’s local pitch span during a given interactional sequence, turn or intonation phrase.” |

| 10 | Returns to the base language/code of an interaction in Extracts (5) and (6) are not cases of self-initiated self-repair, because speakers do not use devices, such as cut-offs, hesitation markers or silences/pauses, that make recognizable for the recipient that they are initiating a repair; i.e., that they are searching for a Greek word that is currently unavailable to them (cf. Kitzinger 2013). |

| 11 | The stressed vowel of the Greek word ðiðima is slightly louder than the stressed vowel of the English word twin, which is drawn out. |

References

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2006. Grammars in contact: A cross-linguistic perspective. In Grammars in Contact: A Cross-Linguistic Typology. Edited by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and Robert M. W. Dixon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Alvanoudi, Angeliki. 2018. Language contact, borrowing and code switching. Journal of Greek Linguistics 18: 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvanoudi, Angeliki. 2019. Modern Greek in Diaspora: An Australian Perspective. Palgrave Pivot. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, Amalia. 1994. Acoustic features of Greek rhythmic structure. Journal of Phonetics 22: 239–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, Amalia. 1999. Standard Modern Greek. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 29: 167–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, Amalia. 2001. The intonation of wh-questions in Greek. Studies in Greek Linguistics 21: 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Arvaniti, Amalia. 2007. Greek phonetics: The state of the art. Journal of Greek Linguistics 8: 97–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, Amalia, and D. Robert Ladd. 2009. Greek wh-questions and the phonology of intonation. Phonology 26: 43–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, Amalia, and Mary Baltazani. 2005. Intonational analysis and prosodic annotation of Greek spoken corpora. In Prosodic Typology: The Phonology of Intonation and Phrasing. Edited by Sun-Ah Jun. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 84–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, Amalia, D. Robert Ladd, and Ineke Mennen. 2006. Phonetic effects of focus and “tonal crowding” in intonation: Evidence from Greek polar questions. Speech Communication 48: 667–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, Peter. 1984. Bilingual Conversation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, Peter. 1995. The pragmatics of code-switching: A sequential approach. In One Speaker, Two Languages: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Code-Switching. Edited by Lesley Milroy and Pieter Muysken. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, Peter. 1996. On the prosody and syntax of turn-continuations. In Prosody in Conversation: Interactional Studies. Edited by Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen and Margret Selting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 57–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, Peter. 1998. Introduction: Bilingual conversation revisited. In Code-Switching in Conversation: Language, Interaction and Identity. Edited by Peter Auer. London: Routledge, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltazani, Mary. 2007a. Prosodic rhythm and the status of vowel reduction in Greek. In Selected Papers on Theoretical and Applied Linguistics from the 17th International Symposium on Theoretical & Applied Linguistics. Thessaloniki: Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, vol. 1, pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltazani, Mary. 2007b. Intonation of polar questions and the location of nuclear stress in Greek. In Tones and Tunes, Volume II, Experimental Studies in Word and Sentence Prosody. Edited by Carlos Gussenhoven and Tomas Riad. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2019. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer. Computer Program, Version 6.0.46. Available online: http://www.praat.org (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Chafe, Wallace L. 1980. The deployment of consciousness in the production of a narrative. In The Pear Stories: Cognitive, Cultural and Linguistic Aspects of Narrative Production. Edited by Wallace L. Chafe. Norwood: Ablex, pp. 9–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chafe, Wallace L. 1993. Prosodic and functional units of language. In Talking Data: Transcription and Coding in Discourse Research. Edited by Jane A. Edwards and Martin D. Lampert. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Clyne, Michael. 2003. Dynamics of Language Contact: English and Immigrant Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth. 1996. The prosody of repetition: On quoting and mimicry. In Prosody in Conversation: Interactional Studies. Edited by Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen and Margret Selting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 366–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth. 2004. Prosody and sequence organization in English conversation. In Sound Patterns in Interaction. Edited by Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen and Cecilia E. Ford. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 335–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth, and Margret Selting. 1996. Towards an interactional perspective on prosody and a prosodic perspective on interaction. In Prosody in Conversation: Interactional Studies. Edited by Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen and Margret Selting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 11–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth, and Margret Selting. 2018. Interactional Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, John, Stephan Schuetze-Coburn, Susanna Cumming, and Danae Paolino. 1993. Outline of discourse transcription. In Talking Data: Transcription and Coding in Discourse Research. Edited by Jane A. Edwards and Martin D. Lampert. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 45–89. [Google Scholar]

- Firth, John R. 1957. Papers in Linguistics, 1934–1951. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Kerstin, ed. 2006. Approaches to Discourse Particles. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Barbara. 2001. An exploration of prosody and turn projection in English conversation. In Studies in Interactional Linguistics. Edited by Margret Selting and Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 287–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, Emily L., and Joseph C. Salmons. 2000. The evolution of a bilingual discourse marking system: Modal particles and English markers in German-American dialects. International Journal of Bilingualism 4: 469–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumperz, John J. 1982. Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, Bernd. 2016. Extra-clausal constituents and language contact: The case of discourse markers. In Outside the Clause: Form and Function of Extra-Clausal Constituents. Edited by Gunther Kaltenbock, Evelien Keizer and Arne Lohmann. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 243–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, Bernd, Gunther Kaltenböck, Tania Kuteva, and Haiping Long. 2021. The Rise of Discourse Markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, John. 2012. Epistemics in action: Action formation and territories of knowledge. Research on Language and Social Interaction 45: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, John, and Geoffrey Raymond. 2012. Navigating epistemic landscapes: Acquiescence, agency and resistance in responses to polar questions. In Questions: Formal, Functional and Interactional Perspectives. Edited by Jan P. de Ruiter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 179–92. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, David, Peter Mackridge, Irene Philippaki-Warburton, and Vassilios Spyropoulos. 2012. Greek: A Comprehensive Grammar, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, Gail. 2004. Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation. Edited by Gene H. Lerner. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, Celia. 2013. Repair. In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Edited by Jack Sidnell and Tanya Stivers. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 229–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, Rosa, Melisa Stevanovic, and Salla Kurhila. 2023. Prosodic linking in apology sequences in Finnish elementary school mediations. Journal of Pragmatics 214: 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, D. Robert. 1996. Intonational Phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, Knud. 1994. Information Structure and Sentence Form. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Local, John, and Gareth Walker. 2012. How phonetic features project more talk. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 42: 255–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Local, John, Peter Auer, and Paul Drew. 2010. Retrieving, redoing and resuscitating turns in conversation. In Prosody in Interaction. Edited by Dagmar Barth-Weingarten, Elisabeth Reber and Margret Selting. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 131–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackridge, Peter. 1985. The Modern Greek Language: A Descriptive Analysis of Standard Modern Greek. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maschler, Yael. 1994. Metalanguaging and discourse markers in bilingual conversation. Language in Society 23: 325–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matras, Yaron. 1998. Utterance modifiers and universals of grammatical borrowing. Linguistics 36: 281–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matras, Yaron. 2009. Language Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muysken, Pieter. 2000. Bilingual Speech. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Papazachariou, Dimitris. 2004. Intonation variables in Greek polar questions. In Graphematische Systemanalyse als Grundlage der Historischen Prosodieforschung. Edited by Peter Gilles and Joerg Peters. Tübingen: Max Nieneyer Verlag, pp. 191–217. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz, Anita. 1988. Offering a candidate answer: An information seeking strategy. Communication Monographs 55: 360–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplack, Shana. 1980. Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish y termino en Español: Toward a typology of code-switching. Linguistics 18: 581–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Rajiv, ed. 2020. Spanish Phonetics and Phonology in Contact: Studies from Africa, the Americas, and Spain. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, Geoffrey. 2003. Grammar and social organization: Yes/no interrogatives and the structure of responding. American Sociological Review 68: 939–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, Elisabeth. 2012. Affectivity in Interaction: Sound Objects in English. Amsterdam: John Benjmanins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, Deborah. 1987. Discourse Markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Selting, Margret. 1996. Prosody as an activity-type distinctive cue in conversation: The case of so-called ‘astonished’ questions in repair. In Prosody in Conversation: Interactional Studies. Edited by Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen and Margret Selting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 231–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selting, Margret. 2000. The construction of units in conversational talk. Language in Society 29: 477–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selting, Margret. 2010. Prosody in interaction: State of the art. In Prosody in Interaction. Edited by Dagmar Barth-Weingarten, Elisabeth Reber and Margret Selting. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanovic, Melisa, and Anssi Peräkylä. 2012. Deontic authority in interaction: The right to announce, propose and decide. Research on Language and Social Interaction 45: 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepek Reed, Beatrice. 2006. Prosodic Orientation in English Conversation. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepek Reed, Beatrice. 2011. Analysing Conversation: An Introduction to Prosody. London: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis, Anastasios M. 2005. The Greeks in Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsitsipis, Lukas D. 1983. Narrative performance in a dying language: Evidence from Albanaian in Greece. WORD 34: 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitsipis, Lukas D. 1998. A Linguistic Anthropology of Praxis and Language Shift: Arvanítika (Albanian) and Greek in Contact. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).