Abstract

The present study assesses the effect of a three-session classroom-based training program involving singing songs with familiar melodies on second-language pronunciation and vocabulary learning. Ninety-five adolescent Chinese ESL learners (M = 14.04 years) were assigned to one of two groups. Participants learned the lyrics in English of three songs whose melodies were familiar to them either by singing or reciting the lyrics, following a native English singer/instructor. Before and after training, participants performed two vocabulary tasks (picture-naming and word meaning recall tasks) and two pronunciation tasks (word and sentence oral-reading tasks). The results revealed that although both groups showed gains in vocabulary and pronunciation after training, the singing group outperformed the speech group. These findings support the value of using songs with familiar melodies to teach second languages at the early stages of learning in an ESL classroom context.

1. Introduction

The use of music and songs in second language (L2) classrooms is perceived positively by teachers (Engh 2013; Tse 2015) despite the fact that their use appears to be rather occasional (Ludke and Morgan 2022). Applied researchers regularly recommend musical activities, such as listening to songs, to teach new vocabulary or grammatical structures (e.g., Arslan 2015; Bokiev et al. 2018; Degrave 2019; Pavia et al. 2019; Saricoban and Metin 2000). However, the use of music in the L2 classroom is usually perceived by teachers as a purely motivational and entertaining activity that allows students to “take a break” from more demanding activities, where the real learning is supposed to take place (e.g., Schoepp 2001). Nonetheless, songs and music may actually afford as much language learning as the perceived “more serious” activities. Research has shown a clear link between music abilities and language skills (e.g., Ribeiro Daquila 2021). Some researchers claim that a “transfer effect” takes place between music and language, i.e., knowledge or skills acquired in one context can be transferred to another context (e.g., Besson et al. 2011; Jäncke 2012). The term “transfer effect” refers to the knowledge or skills acquired in one context that can be transferred to another context or task. For example, a student’s musical skills such as pitch or rhythm perception skills can be transferred to L2 phonological skills (e.g., pitch or rhythm skills in languages, see Chobert et al. 2014; Ribeiro Daquila 2023, for reviews) as well as vocabulary learning (e.g., Chan et al. 1998; Ho et al. 2003; Kang and Williamson 2014).

More specifically, a set of transfer effects have been uncovered for singing expertise. First, a series of studies in which language learners were asked to imitate L2 speech have shown that their singing abilities correlated positively with their L2 pronunciation skills (Christiner and Reiterer 2013, 2015; Christiner et al. 2018, 2022a, 2022b; Coumel et al. 2019). Second, brain imaging studies have found that the mental processes involved in singing can be very similar to those involved in speech (e.g., tonal language processing, Christiner et al. 2022a) and that singing expertise can shape brain structures that are related to linguistic processing (e.g., Halwani et al. 2011). The positive transfer effects reported between singing abilities and phonological skills suggest that engaging language learners in singing sessions in the L2 curriculum may lead to an improvement in their pronunciation skills. Previous studies have tested this hypothesis, with somewhat mixed results, which we review in the following section. Crucially, there is evidence from several first-language acquisition studies that the prior familiarity of learners with a melody may enhance the efficacy of a song-based training program for language learning (Mehr et al. 2016; Peretz et al. 2004; Rainey and Larsen 2002). Using this research as a starting point, the present study aims to assess the effect of a three-session classroom-based singing training program, including songs with familiar melodies, on L2 pronunciation and vocabulary learning. The singing condition will be compared to a speech condition that uses the same materials being recited rather than sung.

1.1. The Effects of Listening to Songs and Singing on L2 Vocabulary and Pronunciation Learning

1.1.1. Training with Songs for Vocabulary Learning

Research on children’s first- and second-language acquisition has shown that learning with songs facilitates lexical memorization more than learning with speech (e.g., Davis and Fan 2016; Ginsborg and Sloboda 2007; Thiessen and Saffran 2009; Wallace 1994). Wallace (1994) pointed out that two crucial complementary elements of children’s songs may explain the high value of songs in early education, namely the use of a repetitive melody and a regular rhythm.

Second-language research has reported mixed findings. Focusing first on the positive effects of listening to songs in an L2, various studies have shown that such activities favor lexical memorization. For example, Salcedo (2010) compared a total of 94 American learners of Spanish who either listened to a Spanish song or listened to the lyrics of this song in a spoken version, as well as a control group that received no treatment. The results showed that the group that listened to the song recalled significantly more parts of the lyrics than the group that listened to the spoken version or the control group. In a similar study, Rukholm (2011) trained 66 beginning learners of Italian during two 30 min sessions and found that participants who listened to a song performed better in a subsequent vocabulary meaning recall task than those who were exposed to the lyrics of the song, which were recited rather than sung. Finally, a classroom study by Yousefi et al. (2014) also showed a positive effect of songs on L2 vocabulary learning. Sixty junior high school female L2 English learners in Iran were randomly divided into two groups, one that listened to a song and the other that listened to a recited version of the lyrics. Once again, the results revealed that, on average, the former group recalled more words from the target lyrics than the latter.

Regarding the effects of having students sing, various studies have reported positive effects on vocabulary learning in both children and adults. Focusing on studies with children, singing has been shown to help children who are recent immigrants to improve their L2 vocabulary recall (Busse et al. 2018), and also help Spanish children to learn L2 English words (Coyle and Gómez Gracia 2014). In another study, Good et al. (2015) asked 38 Ecuadorian children to learn a four-line passage in English by either singing it as a song or reciting it poem-like in four 20 min sessions. Results showed that participants in the singing group recalled significantly more words than participants in the recitation group after the fourth session and at a delayed post-test. Focusing on adults, the between-subjects study by Ludke et al. (2014) asked 60 English-speaking participants without any knowledge of Hungarian to learn 20 Hungarian phrases paired with English translations in a 15 min listen-and-repeat learning task by either singing, repeating, or rhythmically reciting the phrases. The results showed that vocabulary learning was facilitated more by singing than by either repeating or rhythmically reciting.

By contrast, other studies have reported that singing songs may not be more beneficial for vocabulary learning than simple repetition. Baills et al. (2021) explored the effect of listening to songs and singing compared to rhythmically reciting lyrics in French pronunciation and vocabulary learning with 108 young Chinese adults. Although singing songs proved to be useful for pronunciation, the effect it had on vocabulary recall was not enhanced more by singing than by rhythmic recitation. A possible explanation for this is that having to cope with both an unfamiliar foreign language and an unfamiliar melody simultaneously within a limited time was too challenging for the participants and interfered with their vocabulary learning. In a separate within-subjects study, Davis and Fan (2016) explored the effects of a 15-session singing training program on vocabulary learning with 64 Chinese ESL kindergarten students. The students were exposed to singing, speech, and control (no treatment) conditions. Results showed that the singing condition did not have significantly different effects from the speech condition, though both yielded a significantly higher improvement than the control condition. However, the findings might be due to the within-subjects design in that all the participants were exposed to all three conditions at different times. Heidari and Araghi (2015) compared the use of songs and pictures as instructional tools for vocabulary learning with 68 Iranian children learning English. Their results of a vocabulary recall post-test showed that the children who had been exposed to pictures outperformed the children who had been taught to sing a song. Finally, in a study testing L1 learning in adults, Racette and Peretz (2007) tested 18 French non-musicians and 18 professional musicians on their short- and long-term ability to recall the lyrics of unfamiliar songs. Their results showed that the mode of presentation, in other words, whether the song was sung or spoken, did not influence either short- or long-term lyrics recall.

1.1.2. The Effects of Songs on L2 Pronunciation

Several of the studies mentioned in the previous section in connection with song listening also tested the effects of singing on pronunciation on an individual basis. In Baills et al. (2021), although no effects were found for vocabulary learning, singing songs yielded effects similar to those produced by listening to songs and showed significantly higher improvements after training as measured by perceived accentedness ratings compared to recitation. Good et al. (2015) found that the group in the singing condition significantly outperformed the recitation group for the pronunciation of vowels but not for consonants.

A number of classroom studies have assessed the use of songs for L2 learning in a more holistic manner, looking at the effects of singing on various language skills. Fischler (2009) organized a four-week workshop with six advanced intermediate L2 English learners from various countries. Her results showed that rhythmic activities and rap songs helped enhance word stress placement in English for all except one student. Nakata and Shockey (2011) tested whether undergoing a 20 min session of singing in English over three months would help a group of 27 Japanese speakers to improve their L2 pronunciation. The results showed that singing practice significantly reduced the rate of vowel insertion into consonant clusters in this group compared to a control group that had no singing practice. Toscano-Fuentes and Fonseca-Mora (2012) implemented a one-year English learning program involving song listening and singing with 49 Spanish sixth graders. The results showed that the students benefited from the songs and improved their L2 skills in areas such as pronunciation, communication, and comprehension.

By contrast, to our knowledge, three studies have suggested that singing may not help to improve L2 pronunciation. Lowe (1995) compared two groups of English-speaking learners of French, one attending French lessons that included L2 singing activities, and the other simply attending regular French lessons (the control group). Participants’ reading pronunciation was rated after two months, and the results showed that the control group outperformed the singing group. In a second study, Ludke (2018) trained two groups of English-speaking learners of French by either listening to and singing songs or by doing visual arts and drama activities. Her results showed that although the two groups generally improved at post-test, the song activity group improved significantly more in grammar and vocabulary, pronunciation results were not clear-cut: although the singing group outperformed the drama activity group in an intonation and flow of speech test, scores for the two groups were similar on general pronunciation and reading-aloud pronunciation tests. Finally, Nemoto et al. (2016) trained 30 Japanese university students to learn a 14-word sentence taken from song in English that was not familiar to the students either by listening to and singing the sentence or by listening to a native English speaker simply say the sentence. Both groups were then allowed to practice the sentence for ten minutes. The results of a subsequent test revealed that the group that had trained by singing scored lower in pronunciation than the group that had only heard speech.

Taken as a whole, the research presented in the two preceding subsections has yielded mixed results regarding the value of using songs to facilitate the learning of L2 vocabulary and pronunciation. Two possible explanations for the negative results reported by some studies might be that either the melodies of the songs used in training were unfamiliar to the participants, or the training did not include enough repetitions to allow participants to become familiar with the songs. For instance, the study by Nemoto et al. (2016) involved a song that the participants did not know; Ludke (2018) used traditional French tunes with modified lyrics and rap songs from the French Caribbean, which may have proved challenging for the students.

1.1.3. The Role of Familiar Melodies in the Learning of Pronunciation

Familiarity with music has been reported to be an important factor in modulating auditory–motor synchronization responses in the brain because it enables the mind to anticipate harmonic progressions, rhythms, timbres, and melodic and lyric events (see Freitas et al. 2018 for a systematic review). Importantly, familiarity may increase a listener’s liking of a piece of music and positive emotional reactions to it. For instance, Omar Ali and Peynircioǧlu (2010) found that higher ratings of liking and intensity of emotion were given to familiar melodies than to unfamiliar ones. Similarly, Schubert (2007) found a strong correlation between familiarity and liking in participants across a wide age range. Interestingly, Szpunar et al. (2004) found that liking ratings for musical stimuli increased sharply from baseline over the first eight exposures but diminished thereafter, such that by the twenty-third exposure, liking ratings had returned to a baseline value.

Crucially, previous studies have found a familiarity effect in L1 phonological processing. Unfamiliarity may increase task difficulty. Infants can distinguish between consonants /b/ and /p/ at 14 months, but if the sounds they hear are unfamiliar, such as nonsense words instead of genuine words from their L1 (e.g., bih versus pih for the L1 English context), their performance may be worse (Stager and Werker 1997). With regard to L1 vocabulary learning, it has been shown that materials presented with familiar melodies facilitate vocabulary acquisition and memory skills (Rainey and Larsen 2002; Chew et al. 2016; Newman 2017; Creel 2019). For instance, Rainey and Larsen (2002) asked two groups of adult participants to memorize 14 nonsense words accompanied by either speech or songs with familiar melodies. Although no difference was found in an immediate post-test, in a test of their memory after one week the song group remembered the nonsense words faster than the speech group.

To our knowledge, Tamminen et al. (2017) is the only study that was controlled for familiarity in the context of singing training for L2 learning. The authors asked adult native English speakers to learn novel words in one of three conditions: a speech condition, an unfamiliar melody condition, and a familiar melody condition. In the familiar melody condition, participants listened to the melody in an instrumental version several times a day for one week before the training started. In a delayed post-test, participants in the familiar melody condition could recall more words than participants in the speech and unfamiliar music conditions.

Given this direct and indirect evidence in favor of using familiar melodies, some studies have underlined the importance of considering both the learner’s familiarity with a melody and the complexity of the melody when designing a singing training program (Davis and Fan 2016; Rukholm 2011; see also Tamminen et al. 2017).

1.2. Goals of the Current Study

Given the need for further experimental evidence regarding the utility of singing for L2 pronunciation and vocabulary learning, and the potential role of repetition and the use of familiar melodies within training, the present study sets out to investigate the effects of language training involving familiar melodies on L2 pronunciation and vocabulary learning in an ESL context in China. The training program consisted of three sessions in which participants were first exposed to English content that was either sung to them or recited to them in a poetry-like fashion and then asked to repeat what they had heard in the same modality. Notably, the proposed singing program took into account three factors that have been shown to be important in this context, namely (a) the use of familiar melodies, (b) the repetition of the content to be learned, regardless of the modality and, in the case of the singing group, (c) also access to the spoken version of the lyrics. Because participants were tested on speech and not on singing, we considered that having access to native English speech should be the baseline in both training conditions. Therefore, in each session, the speech group was exposed to the rhythmic spoken version of the song seven times, and the singing group was exposed to the rhythmic spoken version twice and to the sung version five times.

Our goals were to compare the effects of singing and poetry-like recitation on the acquisition of L2 vocabulary and pronunciation. Vocabulary gains were to be assessed before and after training by accuracy scores in two vocabulary tests, a picture-naming task and a word translation task. Pronunciation gains were to be assessed through the perceptual rating of participants’ oral production in two English oral-reading tasks (words and sentences) before and after the training program. We hypothesized that the singing group would achieve higher scores in vocabulary and pronunciation tests at post-tests compared to their pretest scores and to the poetry-like recitation group. Given that individual differences in working memory capacity, music aptitude and speech imitation skills may affect L2 phonological and lexical learning (Bley-Vroman and Chaudron 1994; Christiner and Reiterer 2013; Milovanov et al. 2008, 2010; Reiterer et al. 2011), the present study would also control for these measures by checking that the two between-subject groups did not differ significantly on these three measures.

2. Methods

The present study follows a between-subjects pre- and post-test design. The training program consisted of three 30 min sessions. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two training conditions, namely listening to and singing the lyrics of English songs with familiar melodies (henceforth the “singing group”); or listening to and repeating poetry-like recitations of the lyrics of the same English songs (henceforth the “speech group”). The audiovisual materials used and a detailed lesson plan for each of the sessions can be found in the OSF platform, https://osf.io/58ymv/?view_only=3a01311d8191466c97533aa9ba4207b1 (assessed on 16 March 2023).

2.1. Participants

One hundred 13- to 15-year-old 8th-graders were recruited from two class groups in a secondary school in Shandong Province, China. Participants in one class group were assigned to the “singing” condition, in which they listened to and sang the lyrics of English songs with familiar melodies, whereas participants in a second class group were assigned to the “speech” condition, in which they listened to and repeated poetry-like recitations of the lyrics of the same English songs. All of them presented normal hearing and no speech deficits. Participants took part in the experiment on a voluntary basis and prior to the experiment submitted written consents regarding their participation in the training program, the collection of control measures, and the treatment of data resulting from all tasks. Their parents, school administrators, and teachers were given full details of the experiment.

Five participants had to be excluded due to their absence from one of the training sessions. Thus, the final dataset analyzed in this study was obtained from a total of 95 students, of whom 46 were assigned to the singing group (19 females, M = 14.06 years) and 49 to the speech group (21 females, M = 14.02 years). Information about their musical experience and linguistic background was self-reported through a questionnaire (see Appendix A). All participants were monolingual Mandarin speakers and attended English classes every week as part of the school curriculum. They reported using English on average five hours per week, which corresponded to the total duration of their weekly English lessons. Following a recent study by Peng et al. (2021), the English proficiency of 8th-graders in China ranges from the A1 (beginning) to B1 (low-intermediate) levels of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). Participants’ vocabulary knowledge was directly measured with a vocabulary test with 50 words (see Section 2.2.1). Based on Peng et al. (2021) and the results of our vocabulary test, we assumed that participant proficiency ranged between beginner and low-intermediate levels. Based on the information provided by the self-report questionnaires, none of the participants spoke a third language or received formal musical training for more than half a year.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Control Measures

Working memory. An individual’s memory span, or “working memory”, can be measured in terms of the maximum number of words (sequence of numbers, letters, or words) from a list that the person can recall (Henry et al. 2012). Phonological loop capacity is often assessed using tasks such as digit span or word span (Baddeley 2003). The digit span test is commonly used as a typical phonological short-term working memory measurement (Brunfaut and Revesz 2015) notably within the field of L2 research (e.g., Baills et al. 2021; Christiner and Reiterer 2018; Li et al. 2021). The instrument used in this case to measure memory span was a self-administered computer-based adaptation of the forward digit span task by Woods et al. (2011). The participants were asked to recall sequences of digits, starting with three digits. Each correct response led to a trial with one additional digit, whereas an incorrect response resulted in the same number of digits presented again. If two consecutive incorrect responses occurred, the subsequent trial contained one less digit. The entire test comprised 14 trials. The program is available at https://github.com/pnavarro/digit-span (assessed on 15 March 2023). Individual scores were automatically generated by the PsychoPy3 software. The task took approximately 5 min to complete.

Speech imitation skills. To test their ability to imitate non-native speech, each participant completed a modified version of the imitation task used in Zhang et al. (2020) with six unfamiliar foreign languages (Catalan, Hebrew, Japanese, Russian, Turkish, and Vietnamese, see Appendix B). The test involved listening to two short sentences in each language and repeating them to the best of their ability while being recorded. Three native speakers of each language evaluated participants’ oral productions by comparing them with the native pronunciation of the target sentence on a Likert scale from 1 (“very different”) to 9 (“no difference at all”). They were instructed beforehand about the task and had the opportunity to practice with and discuss audio files that displayed a range of imitation skills. Raters had to listen to the sentence pronounced by the native speaker (the actual sample used in the imitation task) and compare it to the participant’s pronunciation by giving a score. The rating procedure was realized via an online survey platform Alchemer. The individual participant’s score was obtained by calculating the means of their scores for the 12 sentences. This test also took around five minutes.

Music perception skills. Musical aptitude was assessed using the melody, pitch, accent, and rhythm perception subtests of the open-access Profile of Music Perception Skills test (PROMs) by Law and Zentner (2012). The four subcomponents were sequentially tested in separate subsections, containing a total of 36 trials. During each trial, participants were presented with a target audio file twice, followed by a comparison audio file. Participants were asked to listen to the audio files and indicate whether the comparison file had the same melody, rhythm, accent, or pitch as the target audio file by choosing from the following response options: “Definitely the same”, “Probably the same”, “I don’t know”, “Probably different”, or “Definitely different”. The scores were calculated automatically by the program and were then available for download from the PROMs server. The test took around 20 min.

Written vocabulary test. In this test, participants were asked to translate into Chinese a set of 50 English words from two textbooks they had used in their classes and had been tested on in the preceding school year (see Appendix C). Each correct answer translation counted as one point, so a perfect score was 50. The test took about 20 min, making the total time required for the control measures about 50 min per participant.

2.2.2. Pre- and Post-test Materials

Participants’ school textbooks were carefully scrutinized and it was ascertained that none of the words or phrases featured in the testing materials appeared, ensuring that participants had no prior knowledge of these items.

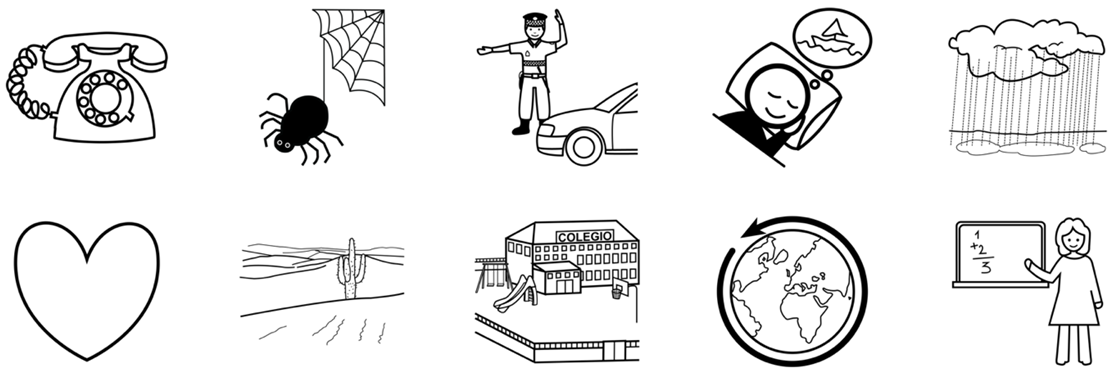

Picture-naming task. Ten words (nouns) were selected from the lyrics of the three songs. A set of ten black and white drawings depicting the meanings of the words was downloaded from the website www.arasaac.org (assessed on 8 May 2020) and printed for distribution to the participants (see Appendix D).

Word and sentence oral-reading tasks. These two tasks consisted of a list of 15 words and six phrases taken from the lyrics (five words and two phrases per song). The materials were printed and handed to each participant (see Appendix E). The total duration of the pre- or post-test procedure (the two were identical) was approximately ten minutes.

2.2.3. Training Materials

Selection of the songs. To select a set of three songs whose melodies would be familiar to Chinese adolescents, a link to an online survey on the online platform Alchemer was sent to 20 students (13 females) from the same school who were not participating in the training study. It listed 27 Chinese pop songs that are well known in China and for which English translations are also available. Next to each song was a link that enabled the survey taker to listen to the song in question. For each song, survey respondents were asked whether they recognized the melody and then asked to rate their degree of familiarity with the melody on a scale of 0 to 100 where 0 represented “I completely can’t recognize this melody” and 100 represented “I am totally familiar with this melody”. The three songs with the highest combination of scores were selected (see Table 1; English versions of the lyrics are available in Appendix F). In addition, after each training session, the teacher confirmed with the participants of the singing group that they were also familiar with the melodies.

Table 1.

Melody recognition and degree of familiarity of the three songs selected.

Audiovisual materials. The audiovisual stimuli consisted of sung and spoken versions of each of the three songs, both versions having been video-recorded in a professional recording studio by a female native speaker of English who was also a trained singer. In the sung version, the singer followed the melody and conveyed the emotions expressed in the lyrics. In the spoken version, there was no music, and the singer enunciated the lyrics in an emphatic and poetic manner so that emotions could also be passed on to the listeners. The mean duration of each recorded song was 60.7 s (sung version) and 55.3 s (spoken version), the difference between the two versions being due to the fact that the sung version contained instrumental interludes between verses. A t-test comparison of the duration of sentence-by-sentence clips showed no statistical differences between sung and spoken versions at the sentence level (t(86) = 1.914, p = 0.059). Before the video recording, the singer was allotted two months to become familiar with the songs by singing and reciting them. The six training videos (three in each condition) were edited in Adobe Premiere Pro CC 2017, which allowed us to add subtitles of the lyrics in English, which were synchronized with the singing, and modify the background (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Still images taken from the audiovisual materials of the three songs.

The training materials for both groups of participants consisted of a PowerPoint presentation into which video clips of the three songs were embedded, either sung or recited. In addition, because all the subsequent testing on pronunciation was based on spoken stimuli, it was considered crucial that the singing group should also have access to the spoken version of the lyrics. Thus, during a 15 min sentence-by-sentence learning phase in each session, the singing group also listened to each line of the song in its recited version (see Procedure below).

Word meaning recall task. At the beginning and end of each training session, a list of vocabulary items was distributed to participants (see Appendix G). Each item consisted of the Chinese translation and then a number of underscores equivalent to the number of letters in the English word, with the first and last letters provided (e.g., “r _ _ _ _ _ _ p” to elicit the word “raindrop”). Participants were expected to fill in the blanks. As the song in the first training session was relatively short and more repetitive, only eight target words were selected, whereas 18 words were selected from each of the two songs tested in the subsequent sessions. Although participants performed this task during the training sessions, not at the time of the pre- or post-tests, the three sets of results were also used as a kind of pretest/post-test to measure the effect of training.

2.3. Procedure

The procedure of the experiment is shown schematically in Figure 2. First, control measures were taken individually, followed two days later by the pretests. One day after the pretests, participants began the sequence of three training sessions, which were separated by three-day intervals. Finally, the post-test was carried out one day after the last training session. The post-test conditions and tasks were identical to those of the pretest. Both the control measures and the pre- and post-test tasks were performed by participants individually in separate silent rooms. The collection of participants’ responses to the control tasks and pre- and post-tests was carried out by six volunteer teachers and the teacher responsible for leading the experimental groups. The same individuals assisted with the handing out and collecting the word translation tests at the beginning and end of each training session. All materials were then sent to the first author for analysis.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the experimental design and procedure.

As noted, the three training sessions for the two experimental conditions took place at three-day intervals. The two groups of participants were guided through the training procedure by the same teacher in consecutive sessions and in separate multimedia classrooms equipped with large computer screens. All training sessions were video-recorded by four cameras (AVA AE-A6 Recording and Playing System) to check for fidelity to the scripted procedure and involvement in the activity on the part of the students. Stills taken from video recordings of the first session in the two classroom conditions can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Still images taken from video recordings of training session 1, for the singing group (left panel) and the speech group (right panel).

The training sessions were guided by one of the host school’s English teaching staff who had volunteered to assist in the experiment. Prior to each session, she was briefed in a 90 min online meeting by the first author on the procedure to follow during that session. She then carried out two trials of the training session, which were video-recorded, one for each experimental condition, using different groups of students, who were not study participants but in the same grade as participants. Recordings of her performance were viewed by and discussed with the three authors, with her participation. There was full agreement that the teacher was able to conduct all sessions effectively and in a way that generated participation from the students present. Hence, no changes were made to the original design.

Each training session lasted around 30 min and centered around learning one of the three selected songs or reciting lyrics in English. A full breakdown of a training session for the singing group can be seen in Table 2. (The script followed by the session leader for each part of the training session can be seen in Appendix H). The procedure followed in the speech group was identical, except that the video that they watched was the recited version on all seven occasions, not the sung one.

Table 2.

Structure of a training session, in this case for the singing condition.

The teacher’s adherence to the training protocol and the degree of student engagement in the training activities were assessed by the first author through an analysis of the video recordings of the three training sessions for both groups. The training procedure was accurately followed by the teacher, who ensured that students produced the target number of repetitions of the training materials. All the sessions ran smoothly without undue interruptions. Though originally intended to each last 30 min, the actual duration of the training sessions ranged from 30 to 39 min.

Finally, the post-test (which was identical to the pretest) was carried out by participants working individually in separate rooms one day after the last training session.

2.4. Data Assessment

Vocabulary. Pre- and post-test vocabulary scores were a number from 0 to 10 indicating the number of correct answers on the ten-item picture-naming task. For the session-embedded word meaning recall task, scores for each participant were calculated by adding the total number of correct answers at two points (pre-training, post-training) in the three sessions (session 1, eight items; session 2, 18 items; session 3, 18 items; total 44). The score for this task was calculated by the mean scores of the three sessions.

Pronunciation. Participants’ pronunciation in the pre- and post-test was evaluated by three native English speakers (M = 34.33 years, all females). The evaluators performed the ratings directly on the online survey platform Alchemer, which allows for the insertion of sound files and item randomization. Prior to the rating, the three evaluators participated in a one-hour training session, during which the authors of the present study explained the rationale for pronunciation evaluation and led raters through a trial rating session with audio samples of both words and sentences.

For the word oral-reading task, a total of 2850 audio recordings were obtained (95 participants × 2 tests × 15 items). In this case, raters were asked to evaluate pronunciation based on a Likert scale from 1 to 9 in terms of accentedness, where 1 corresponded to “extremely accented” and 9 indicated “not accented”.

For the sentence oral-reading task, a total of 1140 audio recordings were obtained (95 participants × 2 tests × 6 items). The raters were asked to evaluate pronunciation based on Likert scales from 1 to 9 in terms of accentedness, comprehensibility, fluency, segmental accuracy, and suprasegmental accuracy.

The evaluators followed the same procedures in the two tasks, first listening to two oral productions of each item, which corresponded to the randomly ordered pretest and post-test renditions of the target word/sentence produced by a single participant, and then rating what they had heard. The program allowed them to play any audio file as many times as they wished.

Inter-rater reliability was assessed with Cohen’s Kappa for each pre- and post-test item (McHugh 2012). For the word oral-reading task, the Kappa score was 0.931, indicating “almost perfect agreement” (κ > 0.90). For the sentence oral-reading task, the Kappa score was 0.894, indicating “strong agreement” (0.80–0.90 range).

2.5. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 26.0. A set of Generalized Linear Mixed Models (henceforth GLMMs) were run to analyze the scores obtained in the two vocabulary tasks and the two pronunciation tasks. The fixed factors in all the GLMM models were condition (two levels: singing group, speech group), test (two levels: pretest, post-test), and their interaction. One random effects block was specified, with participant and item intercepts. Depending on the task, a different set of dependent variables was used. Specifically, the score was used for the session-embedded word meaning recall and picture-naming tasks, whereas the mean accentedness score was used for the word oral-reading task. Five dependent variables were used for the sentence oral-reading task, namely the mean accentedness score, mean comprehensibility score, mean fluency score, mean segmental accuracy score, and mean suprasegmental accuracy score.

3. Results

First, we checked if there were any significant differences between the singing group and speech group in terms of the individual control measures. The scores from a set of independent t-tests confirmed that there were no significant differences between the two groups in any of the five individual measures, as follows: (1) age: t(93) = 1.082, p = 0.282; (2) working memory: t(93) = −0.262, p = 0.794; (3) speech imitation skills: t(93) = 0.538, p = 0.592; (4) musical perception skills: t(93) = 0.237, p = 0.813; and (5) vocabulary knowledge test: t(93) = 0.727, p = 0.469. Descriptive statistics for the above-mentioned individual measures are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Means, min, max, and standard deviations of control measures for the two groups of participants.

3.1. Vocabulary

3.1.1. Picture-Naming Task

Table 4 shows mean scores out of ten on the picture-naming task for the two experimental groups at the pre- and post-test. The result of the GLMM shows that there is a significant main effect of test (p = 0.001), and a significant interaction between condition and test (p = 0.016). No significance was detected on the main effect of condition (p = 0.167), see Table 5.

Table 4.

Picture-naming task: mean, standard deviation, standard error, and 95% confidence interval for scores at pretest and post-test across conditions.

Table 5.

GLMM: fixed effects of mean scores in the picture-naming task.

Post hoc analyses revealed that there was no difference between the singing and speech groups in the pretest (contrast estimate = 0.242, p = 0.473) but the post-test scores differed significantly (contrast estimate = 0.899, p = 0.007). The singing group improved significantly from pre- to post-test (contrast estimate = 1.400, p < 0.001), whereas the speech group did not (contrast estimate = 0.259, p = 0.449).

3.1.2. Session-Embedded Word Meaning Recall Task

Table 6 shows the descriptive statistics of the mean scores for the session-embedded word meaning recall task.

Table 6.

Session-embedded word meaning recall task: mean, standard deviation, standard error, and 95% confidence interval for scores before and after training across conditions.

The result of the GLMM shows a significant main effect of test (F(1, 580) = 392.906 p < 0.001) and a significant condition × test interaction (F(2, 580) = 21.843, p < 0.001). Condition did not show any main effect (p = 0.096). Post hoc analyses revealed that both groups improved significantly from before training to after training (singing group: contrast estimate = 3.573, p < 0.001; speech group: contrast estimate = 2.854, p < 0.001). Although no difference between the groups was found before training (contrast estimate = 0.401, p = 0.408), the singing group obtained significantly higher scores than the speech group after training (contrast estimate = 1.120, p = 0.021).

3.2. Pronunciation

3.2.1. Word Oral-Reading Task

Table 7 shows descriptive statistics for the mean Accentedness scores (minimum 1, maximum 9) from the word oral-reading task.

Table 7.

Word oral-reading task: mean, standard deviation, standard error, and 95% confidence interval for the rating scores at pretest and post-test across conditions.

The results of the GLMM show significant main effects of test (F(1, 2846) = 97.548, p < 0.001) and the interaction between condition and test (F(1, 2846) = 35.160, p < 0.001). There was no main effect of condition (p = 0.194). Post hoc analyses showed that both groups improved significantly from pre- to post-test (singing group: contrast estimate = 0.83, p < 0.001; speech group: contrast estimate = 0.207, p < 0.001). Although the two groups performed equally in the pretest (contrast estimate = −0.128, p = 0.394), the singing group significantly outperformed the speech group in the post-test (contrast estimate = 0.494, p = 0.001).

3.2.2. Sentence Oral-Reading Task

Table 8 shows descriptive statistics for mean rating scores (minimum 1, maximum 9) of the sentence oral-reading task for Accentedness, Comprehensibility, Fluency, Segmental Accuracy, and Suprasegmental Accuracy.

Table 8.

Mean, standard deviation, standard error, and 95% confidence interval for pronunciation ratings at pretest and post-test across conditions.

Table 9 summarizes the results of the five GLMMs analyzing the mean pronunciation ratings in terms of all five variables. The main effect of test (p < 0.001) indicates that the mean rating scores differed significantly from pretest and post-test for all five variables. Condition was not a significant main effect. There was also a significant interaction between condition and test for all five measures (p < 0.001), showing that across all variable measures the singing group improved significantly more than the speech group. Post hoc analyses are detailed below:

Table 9.

Summary of the five GLMMs: fixed effects of the mean rating scores on the sentence oral-reading task.

Accentedness. The two groups did not perform differently in the pretest (contrast estimate = −0.117, p = 0.560), and only a near-significant difference was found in the post-test (contrast estimate = 0.371 p = 0.065), though the singing group obtained higher mean scores than the speech group; when comparing the gains from pretest to post-test for each of the two groups, the results show that both groups performed significantly better in the post-test than in the pretest (singing group: contrast estimate = 0.682, p < 0.001; speech group: contrast estimate = 0.194, p = 0.006).

Comprehensibility. Though the two groups did not perform differently in the pretest (contrast estimate = −0.099, p = 0.677), the singing group obtained significantly higher scores in the post-test compared to the speech group (contrast estimate = 0.487, p = 0.040). However, both groups performed significantly better in the post-test compared to the pretest (singing group: contrast estimate = 0.793, p < 0.001; speech group: contrast estimate = 0.207, p = 0.019).

Fluency. The two groups did not perform differently in the pretest (contrast estimate = −0.202, p = 0.23), but the singing group obtained significantly higher scores in the post-test compared to the speech group (contrast estimate = 0.408, p = 0.016), although again both groups performed significantly better in the post-test than in the pretest (singing group: contrast estimate = 0.924, p < 0.001; speech group: contrast estimate = 0.314, p < 0.001).

Segmental accuracy. The groups did not perform differently in the pretest (contrast estimate = −0.150, p = 0.391), but the singing group obtained significantly higher scores in the post-test compared to the speech group (contrast estimate = 0.476, p = 0.006); again, both groups performed significantly better in the post-test than in the pretest (singing group: contrast estimate = 0.844, p < 0.001; speech group: contrast estimate = 0.219, p = 0.001).

Suprasegmental accuracy. Results here were similar: the groups did not perform differently in the pretest (contrast estimate = −0.140, p = 0.501), but the singing group obtained significantly higher scores in the post-test compared to the speech group (contrast estimate = 0.528 p = 0.011), although both groups performed significantly better in the post-test than in the pretest (singing group: contrast estimate = 0.866, p < 0.001; speech group: contrast estimate = 0.198, p = 0.011).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The present study assessed the benefits of a three-session singing training program using familiar melodies for the acquisition of vocabulary and pronunciation in an ESL context in China. The 95 Chinese middle school students who participated in this between-subjects study were divided into two groups. Whereas one group learned the English lyrics of three songs by listening to and singing them, the other groups listened to and repeated a poetically recited version of the lyrics. The results showed that although both types of training facilitated vocabulary and pronunciation learning, the singing group improved significantly more in both areas than the speech group. Regarding vocabulary, a comparison of the results of a word meaning recall task undertaken at the beginning of the training session and then again at the end of the session revealed that whereas both groups improved after training, participants in the singing group were able to remember significantly more words from the sessions than participants in the speech group. Similarly, in a comparison of the results of a picture-naming task, only the singing group showed a significantly higher word recall after training. Regarding pronunciation, the singing group showed significantly greater improvement in ratings of their pronunciation when reading English words or sentences aloud, across five dimensions, accentedness, comprehensibility, fluency, and segmental and suprasegmental accuracy.

All in all, our results offer further evidence of the value of having students sing songs in the foreign language classroom, in particular, students with beginning to low-intermediate levels of proficiency. These findings complement and expand previous results showing the benefits of using songs for L2 vocabulary learning (Busse et al. 2018; Coyle and Gómez Gracia 2014; Good et al. 2015; Ludke et al. 2014; Rukholm 2011; Salcedo 2010; Yousefi et al. 2014) and pronunciation learning (Baills et al. 2021; Fischler 2009; Ludke et al. 2014; Nakata and Shockey 2011; Toscano-Fuentes and Fonseca-Mora 2012). Crucially, the significantly higher improvements in the singing group detected here may stem from not only the perception of musical melody and rhythm, but also the actual singing activity. A potential reason for these transfer effects is that singing songs helps activate brain networks that facilitate auditory motor-mapping procedures, which in turn facilitate speech production (Gordon et al. 2018). Singing and speaking share large parts of neural correlates (e.g., Özdemir et al. 2006; Zarate 2013), suggesting that transfer may even be more powerful than the skill transfer obtained through music perception. Halwani et al. (2011) showed that professional vocal motor training induces a change in the volume and complexity of the white matter structure and this change improves the interplay between auditory perception and the kinesthetic system (Kleber et al. 2010). In that sense, Christiner and Reiterer (2015) found that professional singers outperform musicians in a speech imitation task, showing that vocal motor training plays a role together with auditory skills and that vocal flexibility correlates with higher speech imitation skills. As for word memorization, the melodic and rhythmic structure of the song may have served as a retrieval strategy (Good et al. 2015). In addition, the oromotor system may be involved in the memorization process (Schulze and Koelsch 2012). All in all, through singing, participants may have forged more robust connections between the sounds they heard, the articulatory movements required to produce those sounds, and the meanings derived from their combinations.

We would like to highlight two other aspects of the present training design that might help to explain why some previous training studies have yielded mixed findings. First, we controlled for the familiarity of the participants with the melodies of the songs by using Chinese pop songs with which participants were almost certainly familiar, replacing the Chinese lyrics with English translations. In our view, the fact that learners were familiar with the melodies of the target songs helped improve the atmosphere of the classroom by reducing students’ anxiety but more importantly meant that all participants’ cognitive efforts were concentrated on learning English rather than learning a new melody. The effectiveness of this strategy backs up previous results showing that familiarity with music will hold the attention of students as well as enhance their enjoyment of classroom activities, thus facilitating memorization skills and therefore L1 and L2 vocabulary acquisition (e.g., Davis and Fan 2016; Freitas et al. 2018; Tamminen et al. 2017). Second, an integral part of the training design was to guarantee that the singing group also listened to a recitation of the lyrics by a native English speaker and was asked to repeat after her. In other words, participants first listened to a recitation of each line of the lyrics before listening to the sung version. It is not clear that the design of some of the previous studies, especially those finding that singing content conferred no benefits for students in terms of acquisition (e.g., Nemoto et al. 2016; Racette and Peretz 2007), controlled for prior participant familiarity with the melody and/or offered participants the possibility of listening to (and repeating after) a recitation of song lyrics before listening to the sung version.

The results of the present study have clear pedagogical implications. We have offered empirical evidence in favor of using songs with familiar melodies in ESL classrooms with lower and lower-intermediate proficiency students, specifically for the improvement of L2 vocabulary and pronunciation. On top of linguistic improvements, exposure to songs and music can also play a positive role in diminishing anxiety, releasing tension, and increasing engagement in classroom activities among learners (Alemi et al. 2015; Geist and Geist 2012) that singing training strategies will be most effective if they involve familiar melodies (such as folk songs or pop songs, Spicher and Sweeney 2007), and also exposure of students to both sung and spoken versions of the lyrics. Since familiarity with melodies can also be culture-dependent, teachers are encouraged to assess the musical preferences of their target learner populations prior to selecting classroom materials and singing activities.

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations of the present study should be noted. First of all, it would have been of interest to confirm the importance of familiarity with melody by comparing results with those obtained from another training group listening to and repeating the same lyrics but accompanied by unfamiliar melodies. Second, a delayed post-test could have been administered to examine whether the effects of training were maintained over time. Moreover, it would be worthwhile to measure these effects in a longer-term training program consisting of a higher number of sessions and a greater variety of songs. Third, the findings reported here may have been age-dependent (it is unclear whether more mature learners would engage with the songs to the same degree as our adolescent learners) or ethnicity-dependent (Chinese participants might be more sensitive to melodic training). Finally, language teachers may be interested in the improvement of pronunciation in spontaneous production rather than through the reading of texts, taking into account the practical and communicative role of L2 pronunciation. In short, future classroom-based research could investigate all these issues.

4.2. Conclusions

On the whole, the present study has provided empirical evidence that a singing training program involving familiar melodies and enough spoken/sung repetitions of the lyrics can be helpful for pronunciation and vocabulary learning in the L2 classroom. The findings reported here have not only helped to identify the features that should be incorporated in the design of successful singing training programs but also point the way for teachers who wish to bring singing training into their classroom practices in a more systematic fashion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z., F.B. and P.P.; methodology, Y.Z., F.B. and P.P.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z., F.B. and P.P.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and F.B.; investigation, Y.Z.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., F.B. and P.P.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, P.P.; project administration, P.P.; funding acquisition, P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Generalitat de Catalunya [2017 SGR_971]; Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades [PGC2018-097007-B-I00]; Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación [PID2021-123823NB-I00]. The second author acknowledges funding by the European Union-NextGenerationEU, the Spanish Ministry of Universities and Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan, through a call from Pompeu Fabra University (Barcelona).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the OSF: https://osf.io/58ymv/?view_only=3a01311d8191466c97533aa9ba4207b1 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Musical and Linguistic Background Questionnaire (English Translation)

| Musical background questionnaire | ||

| Num. | Question | (Answer Type) |

| 1 | Do you play instruments or do vocal training? (Yes/No) If yes, please write down the instruments that you played and the years of playing. (Open answer) | |

| 2 | Have you ever passed instrumental grading tests? (Yes/No) If so, write down the instrument and grade that you have. (Open answer) | |

| 3 | Do you have absolute pitch? (Yes/No) If yes, please listen to a short audio of a musical note and answer which note it was | |

| 4 | Do you read Musical Notation? (Yes/No) | |

| 5 | How often do you listen to music? | (Never/1–2 days per week/3–4 days per week/5–6 days per week/Every day) |

| 6 | Would you consider yourself as a/an… | (Non-musician/Music loving non-musician/Amateur musician/Semi-professional musician/Professional musician.) |

| 7 | Are any members of your family musicians? | (No/Yes, amateur musicians/Yes, professional musicians) |

| Linguistic background questionnaire | ||

| 1 | Do you know any other foreign languages besides English? (Yes/No) | |

| 2 | If yes, please write down the foreign languages that you know, its level and how often you practice it (them) (Open answer) | |

| 3 | How long have you been studying English? (Open answer) | |

| 4 | How much extra time do you dedicate weekly to learn English? (Open answer) | |

Appendix B. Foreign Language Sentences Used in the Speech Imitation Control Task

| Language | Sentences in orthographic form | Translation in English |

| Russian | a. Мы работаем в офисе. | We are working in the office. |

| b. Эта газета лежит на столе. | This newspaper is on the table. | |

| Hebrew | a. שָׁלוֹם. שמי אלון ואני תלמיד. | Hello. My name is Alon and I am a student. |

| b. היום הוא יום יפה ,שהשמש זורחת. | Today is a beautiful day, and the sun is shining. | |

| Turkish | a. Özge ona çarpılmıştı. | Özge had been lovestruck by him. |

| b. Ali hayır dedi. | Ali said no. | |

| Japanese | a. 会社にいらっしゃいますか? | Are you at the company? |

| b. 食事していないんです. | I haven’t eaten yet. | |

| Catalan | a. Els Jocs Olímpics d’hivern de Pyeongchang. | Pyeongchang Winter Olympic Games |

| b. Avui fa un dia molt bonic. | It’s a nice day today. | |

| Vietnamese | a. Rất vui được gặp bạn! | Nice to see you! |

| b. Làm ơn cho tôi mượn tờ giấy. | Please lend me a piece of paper. |

Appendix C. Word List Used for Written Vocabulary Test (Control Measure)

color, telephone, middle, grandparent, eraser, dictionary, baseball, notebook, computer, model, radio, interesting, difficult, strawberry, vegetable, healthy, trousers, January, festival, favorite, subject, science, useful, question, finish, musician, brush, station, exercise, subway, important, elephant, giraffe, country, message, restaurant, straight, describe, popular, excellent, expensive, candle, special, height, newspaper, museum, quite, terrible, kitchen, delicious.

Appendix D. Picture-Naming Task Used in Pre- and Post-Test (10 Nouns)

Appendix E. English Oral-Reading Task (Words and Sentences)

Session 1:

- Words: Fun/Recall/Again/Battle/Matter

- Sentence 1: Try to be the best among the others in a game call the “Spider battle”

- Sentence 2: Then my teacher always told me, never ever be lazy again

Session 2:

- Words: Phone/Telepathic/Raindrop/Sunshine/Desert

- Sentence 1: Wishing we could be more telepathic

- Sentence 2: Can you feel the raindrops in the desert

Session 3:

- Words: Defense/Appear/Melody/Left/Heartbeat

- Sentence 1: Far, far away from me, without warning, and I’m only left with memories

- Sentence 2: Here in my dreams, in my heartbeat, in this melody

Appendix F. Song Lyrics Used in the Training Sessions

1. Childhood

- 1. I recall when I was young

- 2. OH, I will play and always having fun

- 3. with the neighbors next to me

- 4. And we’ll play until the setting sun

- 5. Try to be the best among the others in a game call the “Spider battle”

- 6. It doesn’t matter, who was the best, oh!

- 7. Those were the days of my past

- 8. Few years later when I got to school

- 9. And was late for lessons all the time

- 10. Always daydreaming in the class

- 11. Didn’t know the lesson was over

- 12. Then my teacher always told me, never ever be lazy again

- 13. What can I do now, what can I say now

- 14. Those were the days of my past

2. Sunshine in the Rain

- 1. When I’m in Berlin you’re off to London

- 2. When I’m in New York you’re doing Rome

- 3. All those crazy nights we spend together

- 4. As voices on the phone

- 5. Wishing we could be more telepathic

- 6. Tired of the nights I sleep alone

- 7. Wishing we could redirect the traffic

- 8. And we find ourselves a home

- 9. Can you feel the raindrops in the desert

- 10. Have you seen the sun rays in the dark

- 11. Do you feel my love when I’m not present

- 12. Standing by your side while miles apart

- 13. Sunshine in the rain Love is still the same Sunshine in the rain

- 14. Sunshine in the rain Love is still the same Sunshine in the rain

3. In This Melody

- 1. Without a single defense, and without any distress

- 2. You suddenly appear

- 3. Here in this world of mine

- 4. Bringing me delight

- 5. And full of surprise

- 6. But you, you’re always like this,

- 7. When I think nothing’s amiss

- 8. You go and disappear

- 9. Far far away from me, without warning,

- 10. and I’m only left with memories

- 11. And here you are

- 12. Here deep within my mind

- 13. Here in my dreams, in my heartbeat, in this melody

- 14. And here you are

- 15. Here deep within my mind

- 16. Here in my dreams, in my heartbeat, in this melody

Appendix G. Session-Embedded Word Meaning Recall Tasks Used during Training Sessions

| Session 1. Childhood | |||

| Number | Chinese Meaning | Complete the English word | Answer |

| 1 | 邻居 n. | n _ _ _ _ _ _ r | neighbor |

| 2 | 最好的,最棒的 adj. | b _ _ t | best |

| 3 | 是关紧要,要紧 v. | m _ _ _ _ r | matter |

| 4 | 老师 n. | t_ _ _ _ _ r | teacher |

| 5 | 记起; 回忆起; 回想起 v. | r _ _ _ _ l | recall |

| 6 | 蜘蛛 n. | s _ _ _ _ r | spider |

| 7 | 战斗,比拼 n. | b _ _ _ l _ | battle |

| 8 | 过去 adj. | p _ _ t | past |

| Session 2. Sunshine in the rain | |||

| Number | Chinese Meaning | Complete the English word | Answer |

| 1 | 阳光; 日光 n. | s _ _ _ _ _ _ e | sunshine |

| 2 | 柏林 n. | B _ _ _ _ n | Berlin |

| 3 | 花费,度过,消耗 v. | s _ _ _ d | spend |

| 4 | 伦敦 n. | L _ _ _ _ n | London |

| 5 | 夜晚 n. | n _ _ _ t | night |

| 6 | 罗马 n. | R _ _ e | Rome |

| 7 | 纽约 n. | N _ _ _ _ _ k | New York |

| 8 | 疯狂的 adj. | c _ _ _ y | Crazy |

| 9 | 太阳光线 n. | s _ _ _ _ y | sunray |

| 10 | 心灵感应的 adj. | t _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ c | telepathic |

| 11 | 电话 n. | p _ _ _ e | phone |

| 12 | 改变,改变方向 v. | r _ _ _ _ _ _ t | redirect |

| 13 | 相隔, 不在一起, 分离 adv. | a _ _ _ t | apart |

| 14 | 交通 n. | t _ _ _ _ _ c | traffic |

| 15 | 睡觉 v. | s _ _ _ p | sleep |

| 16 | 雨点; 雨滴 n. | r _ _ _ _ _ _ p | raindrop |

| 17 | 英里 n. | m _ _ e | mile |

| 18 | 沙漠 n. | d _ _ _ _ t | desert |

| Session 3. In this melody | |||

| Number | Chinese Meaning | Complete the English word | Answer |

| 1 | 独自的,仅有一个的 adj. | s _ _ _ _ e | single |

| 2 | 世界 n. | w _ _ _ d | world |

| 3 | 防卫,防备 n. | d _ _ _ _ _ e | defense |

| 4 | 带来 v. | b _ _ _ g | bring |

| 5 | 忧虑,悲伤,痛苦 n. | d _ _ _ _ _ _ s | distress |

| 6 | 突然地 adv. | s _ _ _ _ _ y | suddenly |

| 7 | 没有什么 pron. | n _ _ _ _ _ g | nothing |

| 8 | 出现,现身 v. | a _ _ _ _ r | appear |

| 9 | 高兴,愉悦 n. | d _ _ _ _ _ t | delight |

| 10 | 远的 adj. | f _ r | far |

| 11 | 这里,这儿 adv. | h _ _ e | here |

| 12 | 惊喜,意外 n. | s _ _ _ _ _ _ e | surprise |

| 13 | 不对,不正常 adj. | a _ _ _ s | amiss |

| 14 | 消失,不见 v. | d _ _ _ _ _ _ _ r | disappear |

| 15 | 提醒,警示 n. | w _ _ _ _ _ g | warning |

| 16 | 记忆(复数) n. | m _ _ _ _ _ _ s | memories |

| 17 | 心跳 n. | h _ _ _ _ _ _ _ t | heartbeat |

| 18 | 旋律,乐曲,歌曲 n. | m _ _ _ _ y | melody |

Appendix H. Session Leader’s Script for Training Sessions

| Action | Singing Group | Speech Group |

| Introduction to the training program | A research group from the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona has organized this training program for you consisting of three special classes which will help you learn new words in English and improve your pronunciation. After you finish all three classes, you will each receive a certificate of attendance. We will also do play some games during in the classes. I really hope all of you will enjoy this program and have fun learning English. | |

| Introduction of the instructor | This is Grace, she is from the US. She is a professional singer who has been trained in singing for many years. | This is Grace, she is from the US. She is a professional English teacher who has been teaching English for many years. |

| Session-embedded vocabulary test | Now let’s do a very brief vocabulary test. Please fill this out individually. Don’t worry if there are words that you don’t know. | |

| Listening and repeating line by line | (1) Let’s listen to Grace reading the line once carefully. | |

| (2) Action: teacher explains the line and elicits meanings of vocabulary; students listen to the teacher and then watch the recitation version of the video, line by line. | ||

| (3) Now that we know how to read this line, let’s sing it! Don’t be afraid to make mistakes or not sing perfectly. Please sing it aloud. You can do it! [Students sing the sentence twice] | (3) Now that we know how to read this sentence, let’s recite it aloud! Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. Please recite it aloud. You can do it! [Students recite the sentence twice] | |

| Listening (once) | Listen to the full song again and this time let’s concentrate on repeating the lyrics and at the same time pay attention to the words we have just heard. | Listen to the full recitation poem again and this time let’s concentrate on repeating the texts and at the same time pay attention to the words we have just heard. |

| Vocabulary game | [Action: five-minute vocabulary game minutes, as a break for the students during which they can win stationery as rewards. | |

| Singing/Reciting along | Before, we learnt the words and lines one by one. Now it’s time to sing the whole thing! This time you will see subtitles on the screen. You will find yourselves easily following them! I need to see all of you singing along with the video, alright? | Before, we learnt the words and lines one by one. Now it’s time to recite sing the whole thing! This time you will see subtitles on the screen. You will find yourselves easily following them! I need to see all of you reciting along with the video, alright? |

| Session-embedded vocabulary questionnaire | Before we finish the class, let’s take a few minutes to test how much we learned. I would like to remind you that the test will not affect your school grades so complete it all by yourselves. | |

References

- Alemi, Minoo, Ali F. Meghdari, and Maryam Ghazisaedy. 2015. The impact of social robotics on L2 learners’ anxiety and attitude in English vocabulary acquisition. International Journal of Social Robotics 7: 523–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, Derya. 2015. First grade teachers teach reading with songs. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 174: 2259–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baddeley, Alan. 2003. Working memory and language: An overview. Journal of Communication Disorders 36: 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baills, Florence, Yuan Zhang, Yuhui Cheng, Yuran Bu, and Pilar Prieto. 2021. Listening to songs and singing benefited initial stages of second language pronunciation but not recall of word meaning. Language Learning 71: 369–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, Mireille, Julie Chobert, and Céline Marie. 2011. Transfer of training between music and speech: Common processing, attention, and memory. Frontiers in Psychology 2: 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bley-Vroman, Robert, and Craig Chaudron. 1994. Elicited imitation as a measure of second language competence. In Research Methodology in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Elaine E. Tarone, Susan M. Gass and Andrew D. Cohen. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 245–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bokiev, Daler, Umed Bokiev, Dalia Aralas, Liliati Ismail, and Moomala Othman. 2018. Utilizing music and songs to promote student engagement in ESL classrooms. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 8: 314–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunfaut, Tineke, and Andrea Revesz. 2015. The role of task and listener characteristics in second language listening. Tesol Quarterly 49: 141–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, Vera, Jana Jungclaus, Ingo Roden, Frank A. Russo, and Gunter Kreutz. 2018. Combining song and speech-based language teaching: An intervention with recently migrated children. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Agnes S., Yim-Chi Ho, and Mei-Chun Cheung. 1998. Music training improves verbal memory. Nature 396: 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, Agnes Si-qi, Ya-ting Yu, Si-Wei Chua, and Samuel Ken-En Gan. 2016. The effects of familiarity and language of background music on working memory and language tasks in Singapore. Psychology of Music 44: 1431–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chobert, Julie, Clément Francois, Jean-Luc Velay, and Mireille Besson. 2014. Twelve months of active musical training in 8-to10-year-old children enhances the preattentive processing of syllabic duration and voice onset time. Cerebral Cortex 24: 956–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiner, Markus, and Susanne M. Reiterer. 2013. Song and speech: Examining the link between singing talent and speech imitation ability. Frontiers in Psychology 4: 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiner, Markus, and Susanne M. Reiterer. 2015. A Mozart is not a Pavarotti: Singers outperform instrumentalists on foreign accent imitation. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 9: 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiner, Markus, and Susanne M. Reiterer. 2018. Early influence of musical abilities and working memory on speech imitation abilities: Study with pre-school children. Brain Sciences 8: 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiner, Markus, Bettina L. Serrallach, Jan Benner, Valdis Bernhofs, Peter Schneider, Julia Renner, Sabine Sommer-Lolei, and Christine Groß. 2022a. Examining individual differences in singing, musical and tone language ability in adolescents and young adults with dyslexia. Brain Sciences 12: 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiner, Markus, Julia Renner, Christine Groß, Annemarie Seither-Preisler, Jan Benner, and Peter Schneider. 2022b. Singing Mandarin? What short-term memory capacity, basic auditory skills, musical and singing abilities reveal about learning Mandarin. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 895063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiner, Markus, Stefanie Rüdegger, and Susanne M. Reiterer. 2018. Sing Chinese and tap Tagalog? Predicting individual differences in musical and phonetic aptitude using language families differing by sound-typology. International Journal of Multilingualism 15: 455–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coumel, Marion, Markus Christiner, and Susanne M. Reiterer. 2019. Second language accent faking ability depends on musical abilities, not on working memory. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, Yvette, and Remei Gómez Gracia. 2014. Using songs to enhance L2 vocabulary acquisition in preschool children. ELT Journal 68: 276–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creel, Sarah C. 2019. The familiar-melody advantage in auditory perceptual development: Parallels between spoken language acquisition and general auditory perception. Attention, Perception, and Psychophysics 81: 948–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Glenn M., and Wen-fang Fan. 2016. English vocabulary acquisition through songs in Chinese kindergarten students. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics 39: 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrave, Pauline. 2019. Music in the foreign language classroom: How and why. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 10: 412–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engh, Dwayne. 2013. Why use music in English language learning? A survey of the literature. English Language Teaching 6: 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischler, Janelle. 2009. The rap on stress: Teaching stress patterns to English language learners through rap music. MinneTESOL Journal 26: 35–59. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11299/109937 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Freitas, Carina, Enrica Manzato, Alessandra Burini, Margot J. Taylor, Jason P. Lerch, and Evdokia Anagnostou. 2018. Neural correlates of familiarity in music listening: A systematic review and a neuroimaging meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neuroscience 12: 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geist, Kamile, and Eugene A. Geist. 2012. Bridging music neuroscience evidence to music therapy best practice in the early childhood classroom: Implications for using rhythm to increase attention and learning. Music Therapy Perspectives 30: 141–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsborg, Jane, and John A. Sloboda. 2007. Singers’ recall for the words and melody of a new, unaccompanied song. Psychology of Music 35: 421–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, Arla J., Frank A. Russo, and Jennifer Sullivan. 2015. The efficacy of singing in foreign-language learning. Psychology of Music 43: 627–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Chelsea L., Patrice R. Cobb, and Ramesh Balasubramaniam. 2018. Recruitment of the motor system during music listening: An ALE meta-analysis of fMRI data. PLoS ONE 13: e0207213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwani, Gus F., Psyche Loui, Theodor Rüber, and Gottfried Schlaug. 2011. Effects of practice and experience on the arcuate fasciculus: Comparing singers, instrumentalists, and non-musicians. Frontiers in Psychology 2: 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, Asghar, and Seyed Mehdi Araghi. 2015. A comparative study of the effects of songs and pictures on Iranian EFL learners’ L2 vocabulary acquisition. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research 2: 24–35. Available online: http://jallr.com/index.php/JALLR/article/view/149 (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Henry, Lucy A., David Messer, Scarlett Luger-Klein, and Laura Crane. 2012. Phonological, visual, and semantic coding strategies and children’s short-term picture memory span. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 65: 2033–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Yim-chi, Mei-chun Cheung, and Agnes S. Chan. 2003. Music training improves verbal but not visual memory: Cross-sectional and longitudinal explorations in children. Neuropsychology 17: 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäncke, Lutz. 2012. The relationship between music and language. Frontiers in Psychology 3: 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Hi Jee, and Victoria J. Williamson. 2014. Background music can aid second language learning. Psychology of Music 42: 728–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, Boris, Ralf Veit, Niels Birbaumer, John Gruzelier, and Martin Lotze. 2010. The brain of opera singers: Experience-dependent changes in functional activation. Cerebral Cortex 20: 1144–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Lily N. C., and Marcel Zentner. 2012. Assessing musical abilities objectively: Construction and validation of the Profile of Music Perception Skills. PLoS ONE 7: e52508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Peng, Xiaotong Xi, Florence Baills, and Pilar Prieto. 2021. Training non-native aspirated plosives with hand gestures: Learners’ gesture performance matters. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 36: 1313–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, Anne S. 1995. The Effect of the Incorporation of Music Learning into the Second-Language Classroom on the Mutual Reinforcement of Music and Language. Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ludke, K. M. 2018. Singing and arts activities in support of foreign language learning: An exploratory study. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 12: 371–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludke, Karen M., and Kathryn A. Morgan. 2022. Pop music in informal foreign language learning: A search for learner per-spectives. ITL-International Journal of Applied Linguistics 173: 251–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludke, Karen M., Fernanda Ferreira, and Katie Overy. 2014. Singing can facilitate foreign language learning. Memory and Cognition 42: 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, Mary L. 2012. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica 22: 276–82. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/89395 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Mehr, Samuel A., Lee Ann Song, and Elizabeth S. Spelke. 2016. For 5-month-old infants, melodies are social. Psychological Science 27: 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanov, Riia, Minna Huotilainen, Vesa Välimäki, Paulo A.A. Esquef, and Mari Tervaniemi. 2008. Musical aptitude and second language pronunciation skills in school-aged children: Neural and behavioral evidence. Brain Research 1194: 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milovanov, Riia, Päivi Pietilä, Mari Tervaniemi, and Paulo A. A. Esquef. 2010. Foreign language pronunciation skills and musical aptitude: A study of Finnish adults with higher education. Learning and Individual Differences 20: 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, Hitomi, and Linda Shockey. 2011. The effect of singing on improving syllabic pronunciation–vowel epenthesis in Japanese. Paper presented at The 17th International Conference of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS XVII), Hong Kong, China, August 17–21; pp. 1442–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto, Saori, Ian Wilson, and Jeremy Perkins. 2016. Analysis of the effects on pronunciation of training by using song or native speech. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 140: 3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Jenah. 2017. The Effects of Familiar Melody Presentation versus Spoken Presentation on Novel Word Learning. Doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Omar Ali, S., and Zehra F. Peynircioǧlu. 2010. Intensity of emotions conveyed and elicited by familiar and unfamiliar music. Music Perception 27: 177–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, Elif, Andrea Norton, and Gottfried Schlaug. 2006. Shared and distinct neural correlates of singing and speaking. Neuroimage 33: 628–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavia, Niousha, Stuart Webb, and Farahnaz Faez. 2019. Incidental vocabulary learning through listening to songs. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 41: 745–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]