Abstract

Along with declaratives and interrogatives, imperatives are one of the three major clause types of human language. In Spanish, imperative verb forms present poor morphology, yet complex syntax. The present study examines the acquisition of (morpho)syntactic properties of imperatives in Spanish among English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish. With the use of production and acceptability judgment tasks, this study investigates the acquisition of verb morphology and clitic placement in canonical and negative imperatives. The results indicate that the acquisition of Spanish imperatives among heritage speakers is shaped by the heritage speakers’ productive vocabulary knowledge, lexical frequency and syntactic complexity. Indeed, most of the variability in their knowledge was found in their production of negative imperatives: heritage speakers show a rather stable receptive grammatical knowledge while their production shows signs of variability modulated by the heritage speakers’ productive vocabulary knowledge and by the lexical frequency of the verb featured in the test items.

1. Introduction

Imperatives are one of the three major clause types of human language, along with declaratives and interrogatives (Aikhenvald 2010; Alcázar and Saltarelli 2014; Portner 2016). Imperatives are usually employed to express commands, but they can convey other meanings such as entreaties, requests, advice or instructions (Aikhenvald 2010). Additionally, imperatives present some general syntactic and morphological properties across languages. First, imperative clauses may feature null subjects even in non-pro-drop languages (Alcázar and Saltarelli 2014): subject realization in imperative clauses seems to respond to pragmatic factors (Potsdam 1998). Second, imperative verbs are characterized by having bare or minimally inflected forms (Alcázar and Saltarelli 2014; Birjulin and Xrakovskij 2001). Third, imperative verbs are arguably tenseless (Alcázar and Saltarelli 2014; Beukema and Coopmans 1989; Zanuttini 1996), yet counterexamples have been documented (Aikhenvald 2010).

Imperatives in Spanish present minimally inflected forms yet rich syntactic properties (Alcázar and Saltarelli 2014; Ezeizabarrena 1997; Rivero and Terzi 1995). Ezeizabarrena (1997) discussed the peculiarities of imperatives in Spanish along the lines of finiteness, such as imperatives in Spanish, particularly canonical imperatives, presenting similarities with both finite and nonfinite verbs in Spanish. The relatively poor morphology yet complex syntax characterizing imperatives in Spanish allows for the examination of the acquisition of different language components, namely core syntax versus functional morphology, within the same phenomenon. Specifically, the current study investigates the acquisition of syntactic and morphological properties of imperatives in Spanish among English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish and aims to explore what factors shape this acquisition process.

This article is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a review on the phenomenon under examination and on previous studies on the acquisition of imperatives in Spanish. Section 3 includes the research questions and hypotheses of the study, followed by Section 4, which introduces the study’s participants and methods. Section 5 presents the results, followed by the discussion in Section 6. The conclusion of this study can be found in Section 7.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Imperatives in Spanish

In order to account for the unique properties of imperatives in Spanish, Rivero and Terzi (1995) proposed the existence of an imperative mood operator in the CP layer. This mood operator presents imperative logical mood features that need to be checked for the clause to have a directive meaning. Logical mood refers to the main function of a sentence, and, according to their logical mood, also referred to as illocutionary act, sentences can be categorized as assertives, directives, commissives, expressives, and declarations (Granström 2011; Searle 1979).

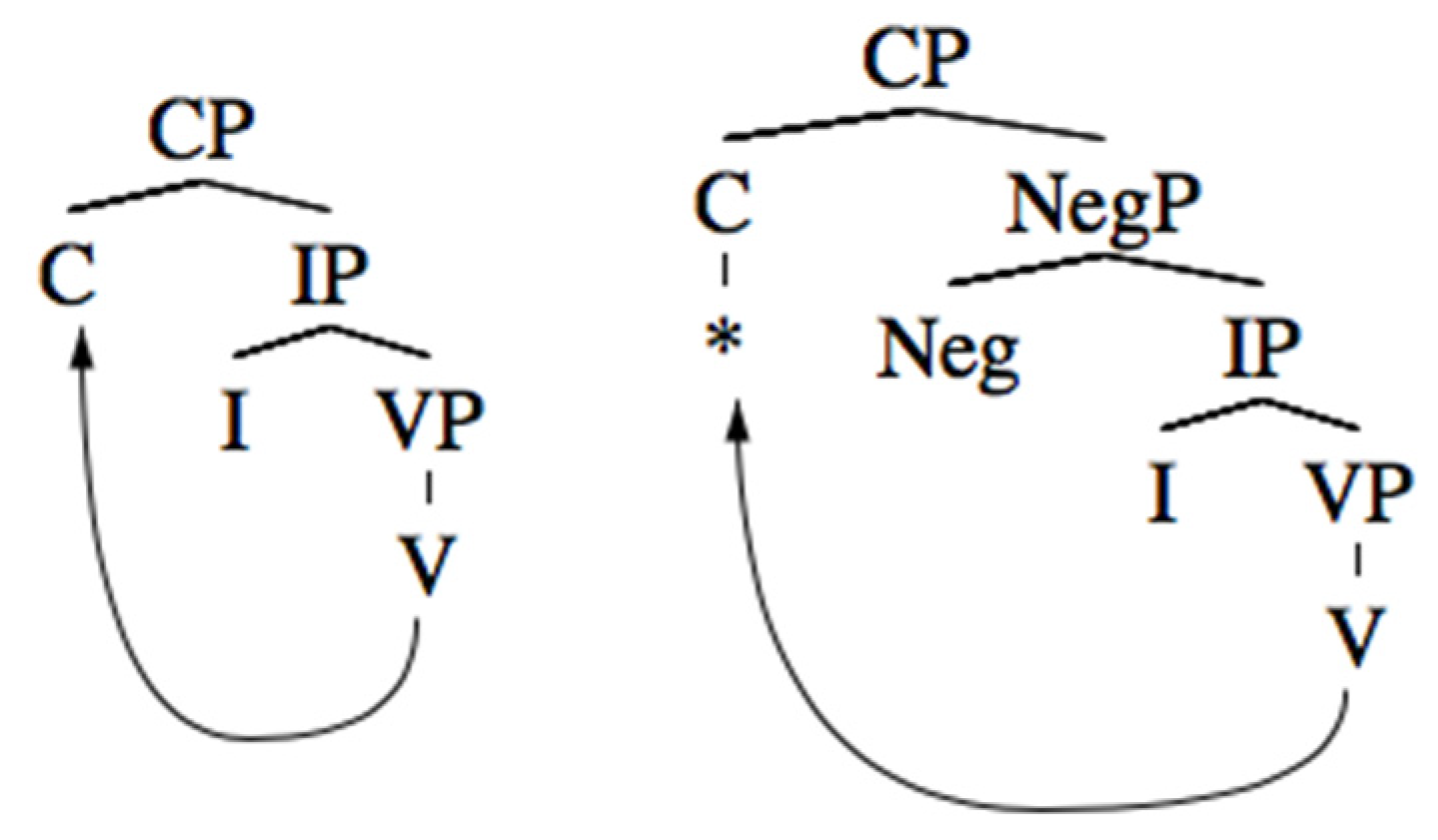

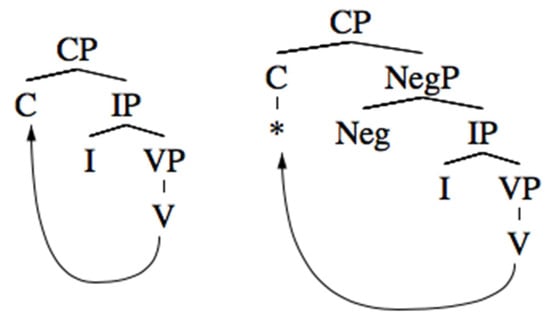

Rivero and Terzi (1995) claimed that languages can be classified into two categories according to the syntax of their imperative verbs: Class I, which presents imperative verbs with unique syntactic properties that distinguish them from other verb forms in the language, and Class II, whose imperative verbs lack such unique properties and, therefore, distribute like any other verb form in the language. Such difference is attested in their morphology, as Class I imperative verbs display a morphology unique to the imperative, whereas Class II imperative verbs do not. Class I imperative verbs, presenting unique imperative morphology, are raised to the CP layer to check the imperative logical mood features, while Class II imperatives remain within the inflectional phrase. Imperative verbs presenting unique imperative morphology are also known as canonical imperatives. Figure 1 below shows a simplified analysis of Class I imperative verbs (Rivero and Terzi 1995).

Figure 1.

Simplified analysis of Class I imperative verbs without (left) and with (right) the presence of a negative phrase (Rivero and Terzi 1995).

Imperatives in Spanish, a Class I language, present different syntactic properties when combined, for instance, with negation or clitics. Specifically, the raising of Class I imperative verbs to the CP layer is blocked by negative phrases, as shown in Figure 1 above. As seen in the examples below, Class I imperative verbs present unique morphology that cannot be combined with negation (1a, 1b), which results in a surrogate verb form, which is the subjunctive morphology in the case of Spanish (Ezeizabarrena 1997; Harris 1997, 1998) (1c):

| (1) Class I verb morphology cannot be negated. |

| (1a) ¡Lee! |

| Read-IMPERATIVE-2sg |

| “Read!” |

| (1b) *¡No lee! |

| Not read-IMPERATIVE-2sg |

| “Do not read!” |

| (1c) ¡No leas! |

| Not read-SUBJUNCTIVE-2sg |

| “Do not read!” |

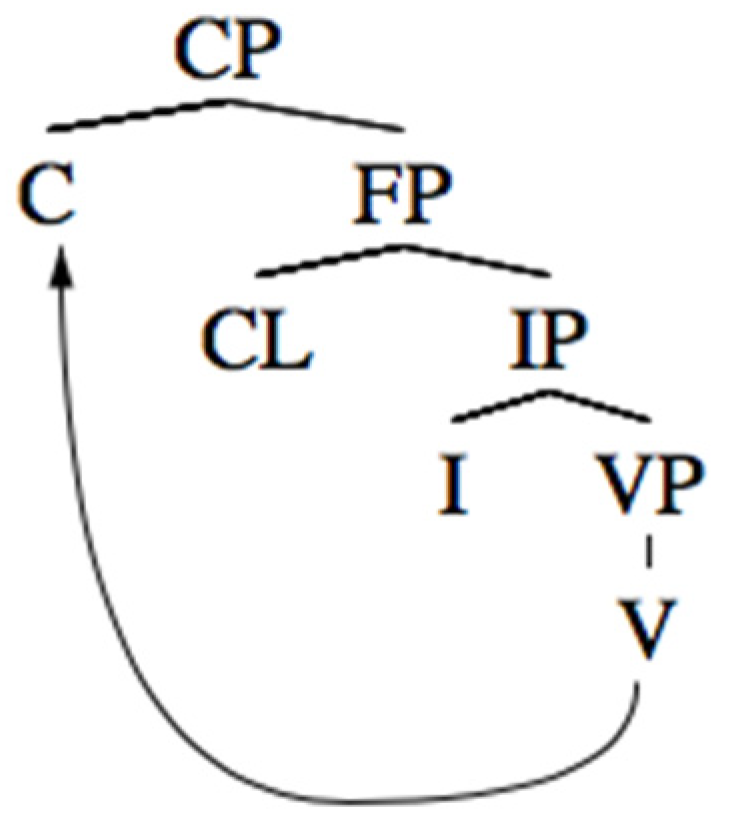

Class I imperative verbs and surrogate verbs in Spanish interact with clitics differently: Class I imperative verbs bypass clitics when raising to the CP layer, leading to enclitics or post-verbal clitics, as shown in Figure 2 below. On the other hand, surrogate verbs present proclitics or pre-verbal clitics as they remain within the inflectional phrase.

Figure 2.

Simplified analysis of Class I imperative verb with clitic (Rivero and Terzi 1995).

In sum, both Class I imperative and surrogate verb forms present specific morphology as well as different syntactic properties with regard to negation and clitics, as seen in the examples (2a–d) below:

| (2a) ¡Léelo! |

| Not Cl Read-PRES-SUBJUNCTIVE-2sg |

| “Read it!” |

| (2b) *¡No léelo! |

| Not Cl Read-PRES-SUBJUNCTIVE-2sg |

| “Do not read it!” |

| (2c) ¡No lo leas! |

| Not Cl Read-PRES-SUBJUNCTIVE-2sg |

| “Do not read it!” |

| (2d) *¡No léaslo! |

| Not Cl Read-PRES-SUBJUNCTIVE-2sg |

| “Do not read it!” |

In summary, Rivero and Terzi (1995) provided an analysis of imperatives in Class I languages, which feature a different verb paradigm in their negative imperatives, as opposed to Class II languages, which use the same imperative verb form regardless of the presence of a negative phrase. They account for the use of a surrogate form in Class I languages as a result of the negative phrase blocking the raising of the verb to the CP layer, whereas imperative verbs in Class II languages always remain below the CP regardless of the presence of a negative phrase.

2.2. Studies on the Acquisition of Imperatives in Spanish

Previous research on the acquisition of Spanish imperatives has mostly been documented among children: monolingual Spanish speakers (Gathercole et al. 1999, 2002) and those bilingually raised in Spanish and Catalan (Grinstead 1998) and in Spanish and Basque (Ezeizabarrena 1997). Ezeizabarrena (1997) analyzed data from a corpus of biweekly video recordings of two bilingual children who were acquiring both Spanish and Basque since birth. The recording sessions started when they were 1;08 and 1;10 and ended when they reached the age of 4. The author claims the acquisition of imperatives among children occurs at an early age, arguably because it is a frequently used form among young children, and it presents poor verbal morphology. Indeed, the two children from the corpus produced second person imperatives in their first session. However, Ezeizabarrena notes that the imperative forms used by the children may not be evidence of knowledge of the imperative verb morphology given that imperative verb morphology in Spanish is very poor.

The study also looks at the acquisition of surrogate forms in negative imperatives. One of the children does not produce any surrogate verb forms in negative imperatives until the age of 2;06. Before, said child produced mostly imperative verb forms in negative imperatives (e.g., no tira, no pisa). From the age of 2;06, the child in question alternated the use of the adult-like present subjunctive surrogate (e.g., no tires, no rompas) form with present indicative forms containing second person singular verb morphology (e.g., no tiras, no pisas). From the age of 3;0, all of the child’s negative imperatives were adult-like. For other verb paradigms, the child started producing adult-like verb forms with subject–verb agreement at the age of 1;10. Nonetheless, all clitics produced in imperative clauses featured an adult-like pattern (i.e., proclisis with imperative verb forms).

Ezeizabarrena (1997) concluded that children produce adult-like imperative forms in Spanish at a young age, but it is difficult to determine whether they are producing second person inflectional morphology or a bare form due to the poor morphology of imperative forms in Spanish, but mostly to the fact that imperatives in Spanish are in the middle of the continuum between finite and nonfinite forms. The fact that children may not be aware of the finiteness of imperatives in Spanish can also account for why adult-like forms of the negative imperative do not appear consistently until the age of 3;00. On the other hand, the two children produced infinite imperatives in Basque throughout the entire data collection period. The author argues that these infinite imperative forms are the most frequent ones among adults.

Grinstead (1998) examined the acquisition of subject and imperatives among Spanish-speaking and Catalan-speaking children. The author noted that imperatives are realized, but never combined with negation: the children under examination never produce ungrammatical imperative clauses using a negative phrase combined with an imperative verb form instead of with a surrogate form. Grinstead claimed that this is the result of principles of Universal Grammar. Specifically, “child Spanish and Catalan speakers cannot raise imperatives over negation because doing so would violate Relativized Minimality” (p. 137). Furthermore, Grinstead argued that children that age do produce negation in declaratives, but they do not produce surrogate forms in their negative imperative clauses because “subjunctive morphology is generally not available to children in this early period” (p. 142).

Gathercole et al. (2002) replied to Grinstead’s work by claiming that, among Spanish-speaking children, negative imperatives may be rare in young child language, but they occur. Children produce imperative clauses with illocutionary force using present indicative, a rote-learned form or a phonetically reduced form of the verb (e.g., no toca ahí, no caga, no cupeh). Gathercole et al. (2002) also noted that the acquisition of the subjunctive mood took place after the acquisition of negative imperatives among the Spanish-speaking children that they examined. Their acquisition of imperative verbs and surrogate forms is lexically driven, as early knowledge of verbs and verb forms is lexically specific.

Gathercole et al. (1999) analyzed the speech of a group of Spanish-speaking children and noted that the acquisition of verb paradigms is lexically driven and is not error-free. For instance, a verb like mirar (“look”) may be used in an imperative clause (e.g., ¡Mira!) earlier than in other verb paradigms, while acabar (“finish”) may do so in the preterit (e.g., Acabó). Additionally, there is no evidence that canonical imperatives occur earlier than other verb forms. Gathercole et al. (1999) defined this process as a piecemeal acquisition.

To summarize, the acquisition of imperatives in Spanish is characterized by its early appearance in child acquisition. On the other hand, the acquisition of negative imperatives does not take place until later, given that negative imperatives are not mastered until 3;00 (Ezeizabarrena 1997). Grinstead (1998) discussed that, until that age, Spanish-speaking children do not produce any negative imperatives with either imperative verb forms or surrogate forms. On the other hand, Gathercole et al. (1999) claimed that the acquisition of imperatives in Spanish is not error-free: Spanish-speaking children do produce non-adult-like negative imperatives, with imperative verb forms instead of surrogate verb forms before mastering their distribution. These authors emphasized how lexically driven the acquisition of imperatives is and argued that it could be considered as a piecemeal acquisition process as opposed to Grinstead’s (1998) rather categorical view.

2.3. Heritage Language Acquisition and Lexical Frequency

Putnam and Sánchez (2013) claimed that how often heritage languages are used for production and comprehension purposes has an effect on the stability or on the restructuring that the heritage languages experience. By referring to functional features (FFs), phonological form (PF), and semantic features, the authors’ activation approach indicates that heritage speakers present four different outcomes depending on how frequently they use their heritage language versus their dominant language.

- Stage 1:

- Transfer or re-assembly of some FFs from the L2 grammar to L1 PF and semantic features which may coincide with the activation of L2 lexical items on a more frequent basis from the standpoint of linguistic production;

- Stage 2:

- Transfer or re-assembly of massive sets of FFs from the L2 to L1 PF and semantic features, while concurrently showing significantly higher rates of activation of L2 lexical items than L1 lexical items for production purposes (i.e., they might code-switch more than bilinguals in the previous situation);

- Stage 3:

- Exhibit difficulties in activating PF and semantic features (as well as other FFs) in the L1 for production purposes but are able to do so for comprehension of some high frequency lexical items;

- Stage 4:

- Have difficulties activating PF features and semantic features (as well as other FFs) in the L1 for both production and comprehension purposes. (Putnam and Sánchez 2013, pp. 489–90).

The activation approach to heritage language acquisition is built on Lardiere’s (2008, 2009) Feature Reassembly Hypothesis, which was conceived for L2 learners. Putnam and Sánchez’s (2013) activation approach establishes a connection between heritage language activation and heritage language acquisition and maintenance (Levy et al. 2007; Linck et al. 2009; Seton and Schmid 2016), particularly due to the heritage speaker’s L2 (and dominant language) becoming the more activated language and the heritage language being frequently inhibited (Putnam et al. 2019).

Given the differences between Spanish and English with regard to the syntactic properties of their imperative clauses, heritage speakers of Spanish could restructure their heritage language imperatives due to crosslinguistic influence from English, their dominant language, as a result of low levels of heritage language activation. Specifically, Spanish imperatives, which belong to Rivero and Terzi’s (1995) Class I, would be restructured and adopt syntactic properties of Class II imperatives. If this were to happen, it would be observed in the heritage speakers’ use of the same verb morphology for both canonical and negative imperatives, which would have an effect on clitic placement. Recall that Spanish canonical imperatives present enclitics while negative imperatives, which feature a surrogate verb form consistent with that of the present subjunctive, present proclitics. Specifically, as a result of crosslinguistic influence from English, heritage speakers could restructure their heritage Spanish and use bare verb forms with enclitics only in both canonical and negative imperatives.

This restructuring process, however, is predicted to show signs of variability as a function of how frequently the heritage language is activated (Putnam and Sánchez 2013). Indeed, with the use of different variables operationalizing heritage language activation, previous studies have documented heritage language variability in the acquisition of morphosyntax (Hur et al. 2020; Putnam and Schwarz 2014; Yager 2016; Yager et al. 2015, inter alia). Such variability has been linked to patterns of heritage language exposure and use as an operationalization of heritage language activation (e.g., Cuza and Pérez-Tattam 2015; Goldin 2020; López Otero et al. 2021; López Otero et al. 2023). Other studies have found lexical frequency effects in heritage Spanish (Giancaspro 2017; Goldin et al. 2023; Hur 2020; Hur et al. 2020; López Otero 2022; Perez-Cortes 2022). These studies operationalized heritage language activation as lexical frequency and hypothesized that heritage speakers activate frequent lexical items more often than infrequent lexical items. The present study aims to test Putnam and Sánchez’s (2013) activation approach by operationalizing heritage language activation as lexical frequency. If lexical frequency effects play a role in the acquisition of imperatives in heritage Spanish, one could argue that such variability is the result of different levels of heritage language activation at the lexical level.

3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

This study investigates the acquisition of Spanish imperatives among English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish. Specifically, it focuses on the acquisition of the syntactic and morphosyntactic properties of canonical versus negative imperatives. Additionally, it explores the effects of productive vocabulary knowledge as well as of lexical frequency on the heritage speakers’ acquisition of imperatives in Spanish. The examination of lexical frequency effects aims to test Putnam and Sánchez’s (2013) activation approach given that lexical frequency can be considered as a proxy of heritage language activation. The following research questions guide this study:

RQ1: What acquisition patterns of the syntactic and morphosyntactic properties of Spanish imperatives do English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish show?

Hypothesis 1.

We hypothesize that heritage speakers of Spanish show variable knowledge of both the syntactic and morphosyntactic properties of Spanish imperatives as a result of the restructuring of heritage language features (Putnam and Sánchez 2013). Particularly, due to cross-linguistic influence from English, their dominant language, heritage speakers will show signs of treating Spanish imperatives as Class II imperatives, which present the same syntactic and morphosyntactic properties in both canonical imperatives and negative imperatives. This is consistent with previous studies documenting crosslinguistic influence in the heritage language from the dominant language (Cuza 2013; Cuza and Frank 2011; Montrul 2004; Pascual y Cabo and Gómez Soler 2015; Shin et al. 2023; van Osch 2019, inter alia).

RQ2: To what extent does productive vocabulary knowledge predict the acquisition of the morphosyntactic and syntactic properties of imperatives among English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish?

Hypothesis 2.

We hypothesize that productive vocabulary knowledge in the heritage language predicts the acquisition of the phenomena under examination among English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish. Productive vocabulary knowledge can be considered as a proxy for overall proficiency (Bedore et al. 2012; Gollan et al. 2012; Sheng et al. 2014; Treffers-Daller and Korybski 2015) and heritage language studies have found it to be a significant predictor of heritage language acquisition across several (morpho)syntactic phenomena (e.g., Hur 2020, 2022; Hur et al. 2020; López Otero 2022).

RQ3: To what extent is the acquisition of the morphosyntactic and syntactic properties of imperatives among English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish modulated by lexical frequency?

Hypothesis 3.

We hypothesize that the acquisition of the morphosyntactic and syntactic properties of imperatives among English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish is modulated by lexical frequency, which has been used as a proxy for heritage language activation. Following Putnam and Sánchez’s (2013) activation approach, the constant activation of the L2, which is the heritage speakers’ dominant language, leads to the inhibition of the heritage language for both production and comprehension purposes. Previous studies have found that heritage language activation can be operationalized as lexical frequency and, consequently, the acquisition of (morpho)syntactic properties presents lesser degrees of variability with frequent lexical items than with infrequent lexical items (e.g., Giancaspro 2017; Goldin et al. 2023; Hur 2020; Hur et al. 2020; López Otero 2022; Perez-Cortes 2022).

4. The Study

4.1. Participants

The participants in this study completed several tasks and a language background questionnaire. The language background questionnaire collected data on various aspects, such as the age at which they started learning different languages, their language exposure and usage patterns, and their self-rated language proficiency. Two screening tasks were conducted to assess the participants’ proficiency in Spanish and English. First, the DELE (Diploma de Español como Lengua Extranjera) test and the MiNT. The former (administered in several studies including (Cuza et al. 2013; Duffield and White 1999; Montrul and Slabakova 2003)) is a 50-item multiple-choice proficiency instrument adapted from a vocabulary task from the MLA Foreign Language Test and a cloze test from the Diploma de Español como Lengua Extranjera (DELE) focusing on (morpho)syntactic knowledge whereas the MiNT measures productive vocabulary knowledge. Traditionally, participants have been divided into three groups according to their DELE scores: low for those who score below 30, intermediate for those who score between 30 and 39, and advanced for those who score above 40. The Multilingual Naming Test (MiNT; Gollan et al. 2012), on the other hand, is a lexical knowledge task that prompts participants to name 68 objects depicted in black-and-white images. The MiNT was designed for Spanish, English, Mandarin, and Hebrew given that the words targeted in the test are not cognates between these languages. In the present study, the MiNT is used to measure productive vocabulary knowledge in both Spanish and English. While the DELE has been widely used to measure Spanish language proficiency in L2 and heritage language studies, an increasing number of studies are administering the MiNT in order to gather information about Spanish language proficiency, particularly among heritage speakers who may not feel comfortable reading and writing in Spanish (e.g., Hur 2020, 2022; Hur et al. 2020; López Otero 2022). The experimental tasks consisted of an elicited production task (EPT), an acceptability judgment task (AJT), and a self-rating lexical frequency task (SRLFT).

Eighty-one subjects participated in the study. They were categorized in two groups: English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish (n = 56; 40 women; age range = 18–46; M = 22.38; SD = 4.68) and Spanish-dominant Spanish-English bilinguals (n = 25; 17 women; age range = 20–48; M = 33.36; SD = 7.72). The latter served as a comparison group. The participants resided in the northeastern United States at the time of data collection. All participants provided consent and received compensation for their participation.

The heritage speakers acquired English at different ages throughout their childhood. Thirty-three of them were simultaneous bilinguals (range of age of acquisition of English = 0–3; M = 0.85; SD = 1.33) while thirty were sequential bilinguals (range of age of acquisition of English = 4–7; M = 5.09; SD = 0.90). The heritage speakers’ parents spoke various varieties of Spanish, including Mexican Spanish (n = 21), Colombian Spanish (n = 12), Ecuadorian Spanish (n = 12), Dominican Spanish (n = 11), Cuban Spanish (n = 10), Peruvian Spanish (n = 10), Puerto Rican Spanish (n = 8), Guatemalan Spanish (n = 6), Central American Spanish (n = 5), Peninsular Spanish (n = 4), Salvadoran Spanish (n = 4), Chilean Spanish (n = 2), Filipino Spanish (n = 2), Honduran Spanish (n = 2), U.S. Spanish (n = 2), Panamanian Spanish (n = 1), and L2 Spanish (n = 1). Table 1 provides an overview of the language background information for both the heritage speakers and the Spanish-dominant bilinguals.

Table 1.

Participants’ language background information.

The Spanish-dominant Spanish-English bilinguals started their acquisition of English at different ages (range = 3–25; M = 9.2; SD = 5.19) and spoke a wide array of varieties of Spanish: Peninsular Spanish (n = 5), Mexican Spanish (n = 4), Colombian Spanish (n = 3), Dominican Spanish (n = 3) Peruvian Spanish (n = 3), Venezuelan Spanish (n = 2), Argentinian Spanish (n = 1), Chilean Spanish (n = 1), Cuban Spanish (n = 1), Ecuadoran Spanish (n = 1), and Puerto Rican Spanish (n = 1). Although some Spanish-dominant speakers reported having started to receive exposure to English during their childhood, they were all monolingually raised in Spanish in monolingual Spanish-speaking environments. Some of them were exposed to some English at school settings in Spanish-speaking countries. As seen in their MiNT scores in Table 2 below, they are dominant in their native Spanish.

Table 2.

Comparison between DELE-based proficiency groups and MiNT scores.

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Screening Tasks

As mentioned above, all the participants completed two screening tasks to measure their language proficiency: the DELE and the MiNT. Table 2 shows a comparison between the participants’ DELE and MiNT scores. Heritage speakers are subdivided in groups according to their DELE scores. Nevertheless, this study only uses the heritage speakers’ MiNT scores as a continuous variable to investigate proficiency effects. DELE scores were collected in order to provide a comparison point with previous studies that may have used the DELE and not the MiNT as a tool to measure proficiency.

As seen in Table 2, DELE and Spanish MiNT scores increase hand in hand; however, English MiNT scores remain constant across DELE-proficiency groups, as the heritage speakers are dominant in English. Furthermore, the contrast between Spanish and English MiNT scores among the Spanish-dominant Spanish-English bilinguals confirms that this group is indeed formed of Spanish-dominant speakers. Specifically, the heritage speakers’ DELE test scores ranged from 21 to 50 out of 50 (M = 38.52/50; SD = 7.63) overall: twelve heritage speakers scored between 20 and 29, fifteen scored between 30 and 39, and twenty-nine scored above 40. Their MiNT scores in Spanish ranged from 24 to 61 out of 68 (M = 44.2/68; SD = 10.4), while their MiNT scores in English ranged from 50 to 68 out of 68 (M = 63.1/68; SD = 3.45). Finally, the Spanish-dominant bilinguals’ MiNT scores in Spanish ranged from 61 to 68 out of 68 (M = 64/68; SD = 7.75), while their MiNT scores in English ranged from 43 to 67 out of 68 (M = 57.3/68; SD = 6.36).

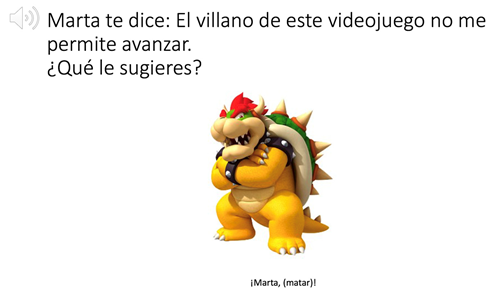

4.2.2. Elicited Production Task

The elicited production task (EPT) was the first experimental task that participants completed. It was administered orally with the help of a PowerPoint presentation and elicited the use of imperative clauses consisting of a verb and an accusative clitic referring to a human antecedent presented in the preamble. It included 12 experimental items in two conditions (k = 6): (a) canonical imperatives and (b) negative imperatives. The two conditions were distinguished by the presence or absence of the adverb no, which appear in parentheses along with the verb that participants were asked to use. There were 56 distractors. For each test item, the participants read and heard a preamble followed by a prompt in the form of a question, as shown in (3):

| (3) | a. | Condition: Canonical imperative. | |

| Preamble: | Marta te dice: El villano de este videojuego no me permite avanzar. “Marta tells you: the villain of this video game does not allow me to advance”. | ||

| Prompt: | ¿Qué le sugieres? “What do you suggest she does?” along with a picture and matar in parentheses. | ||

| Expected response: | ¡Marta, mátalo! “Kill him!” | ||

| b. | Condition: Negative imperative. | ||

| Preamble: | Marta te dice: Fernando y yo tenemos algunos problemas, pero nos queremos. “Marta tells you: Juan and I have some problems, but we love each other”. | ||

| Prompt: | ¿Qué le sugieres? “What do you suggest she does?” along with a picture and no dejar in parentheses. | ||

| Expected response: | ¡Marta, no lo dejes! “Do not leave him!” | ||

Below the prompts, participants were shown a picture as well as a verb, which could be preceded by the adverb no if the test item aimed to examine negative imperatives. At the bottom of the test items, participants were shown a vocative (e.g., Marta, Felipe) followed by a blank, which they were instructed to fill in with the words in parentheses. In order to keep consistency and allow for the study of lexical frequency effects, the same six verbs were used across the two conditions: ayudar (“help”), buscar (“search”), dejar (“leave”), echar (“expel”), llamar (“call”), matar (“kill”). They were all morphologically regular -ar verbs. With the exception of ayudar, all six verbs were disyllabic. These six verbs were used in the AJT as well. The participants completed three practice items at the beginning of the task. The EPT had two counterbalanced versions. Appendix A includes all EPT test items and Appendix C shows an EPT test item sample.

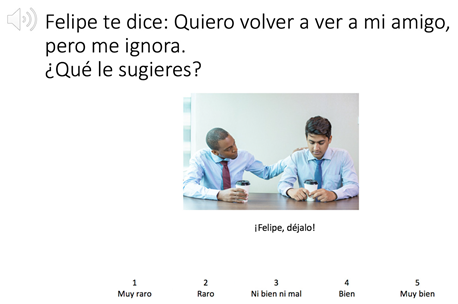

4.2.3. Acceptability Judgment Task

The acceptability judgment task (AJT) was the second experimental task that participants completed. The goal of the AJT is to examine the receptive grammatical knowledge of the morphosyntactic and syntactic properties of imperatives in heritage speakers. Like the EPT, it was administered using a PowerPoint presentation. It presented participants with both written and oral input. Participants were asked to read and listen to the test items and to rate the prompts using a Likert scale. This task included 56 distractors along with 12 experimental items, which were distributed in four conditions (k = 3): (a) grammatical canonical imperatives, (b) grammatical negative imperatives, (c) ungrammatical canonical imperatives, and (d) ungrammatical negative imperatives. Each test item included a preamble, a picture and a prompt as well as five-point Likert scale: (1—Completamente raro “completely odd”, 2—Raro “Odd”, 3—Ni bien ni mal “Neither good nor bad”, 4—Bien “Good”, 5—Completamente bien “Completely good”), as shown in (4):

| (4) | a. | Condition: Grammatical canonical imperatives. | |

| Preamble: | Marta te dice: El villano de este videojuego no me permite avanzar. ¿Qué le sugieres? “Marta tells you: the villain of this video game does not allow me to advance. What do you suggest she does?” | ||

| Prompt: | ¡Marta, mátalo! “Marta, kill him!” | ||

| Expected response: | 4 or 5. | ||

| b. | Condition: Grammatical negative imperatives. | ||

| Preamble: | Marta te dice: Fernando y yo tenemos algunos problemas, pero nos queremos. ¿Qué le sugieres? “Marta tells you: Juan and I have some problems, but we love each other. What do you suggest she does?” | ||

| Prompt: | ¡Marta, no lo dejes! “Marta, do not leave him!” | ||

| Expected response: | 4 or 5. | ||

| c. | Condition: Ungrammatical canonical imperatives. | ||

| Preamble: | Marta te dice: El villano de este videojuego no me permite avanzar. ¿Qué le sugieres? “Marta tells you: the villain of this video game does not allow me to advance. What do you suggest she does?” | ||

| Prompt: | ¡Marta, lo mata! “Marta, kill him!” | ||

| Expected response: | 1 or 2. | ||

| d. | Condition: Ungrammatical negative imperatives. | ||

| Preamble: | Marta te dice: Fernando y yo tenemos algunos problemas, pero nos queremos. ¿Qué le sugieres? “Marta tells you: Juan and I have some problems, but we love each other. What do you suggest she does?” | ||

| Prompt: | ¡Marta, no déjalo! “Marta, do not leave him!” | ||

| Expected response: | 1 or 2. | ||

| Likert scale (a.–d.): 1—Completamente raro “completely odd”, 2—Raro “Odd”, 3—Ni bien ni mal “Neither good nor bad”, 4—Bien “Good”, 5—Completamente bien “Completely good” | |||

If participants rated a prompt as 1 or 2, they were asked to provide an explanation in order to confirm that their rejection was related to the phenomenon under examination. As in the EPT, the task was administered by using two counterbalanced versions that ensured that verbs were distributed evenly across conditions in order to examine lexical frequency effects. In the AJT, participants also completed three practice items before starting the experimental items. Appendix B includes all AJT test items and Appendix C shows an AJT test item sample.

4.2.4. Self-Rating Lexical Frequency Task

The last task that participants completed was a self-rating lexical frequency task (SRLFT) (Hur et al. 2020). The goal of this task is to collect lexical frequency counts that are representative of the input and output that heritage speakers of Spanish are exposed to and produce in the United States, where several varieties of Spanish coexist. Such diversity is represented in our participants, as described in the participant section above. In these diverse contexts, Spanish corpora may present limitations.

Participants were asked to rate how often they produced and were exposed to the verbs used in the experimental tasks above with the use of a nine-point Likert scale: 1—never; 2—hardly ever; 3—a few times a year; 4—once a month; 5—a few times a month; 6—once a week; 7—several times a week; 8—once a day; 9—several times a day. Participants rated how often they produced (orally or in writing) in a first Likert scale, followed by a second Likert scale, which they were prompted to use to indicate how often they were exposed to (by listening or by reading) the verbs under examination. Additionally, in order to confirm the participants’ knowledge of these lexical items, they were also prompted to provide either an English equivalent or a Spanish synonym. The participants’ ratings were averaged within and across participants. The results are group self-rated lexical frequency counts ranging from 2 to 18. Appendix D shows the heritage speakers’ lexical frequency counts of the six verbs used in the EPT and AJT in decreasing order.

5. Results

5.1. Elicited Production Task

The results from the EPT were transcribed and coded by considering both the verb forms and the forms that the participants used to refer to the antecedent in the preamble. The combination of these two resulted in a myriad of responses. A summary of these responses across conditions and groups can be found in Appendix E. It is noteworthy to mention that all participants produced either tú or usted forms, with the exception of one participant, who used two instances of voseo (echalo and dejalo). This participant reported speaking Honduran Spanish.

The data coding was simplified in order to facilitate the statistical analysis. In the canonical imperative condition, imperative verb form followed by proclitic or DP was coded as expected while all other responses were coded as unexpected. In the negative imperative condition, surrogate imperative verb forms (which in Spanish share the same verb form with the present subjunctive) conjugated in second person singular (e.g., tú, usted, vos) followed by either a proclitic or a DP were coded as expected. All other forms were coded as unexpected. Table 3 shows the counts and proportions of expected and unexpected responses across conditions and groups.

Table 3.

Counts and proportions of expected responses across conditions and groups.

These data from the EPT were analyzed with the help of generalized linear mixed model, which was performed with the glmer function of the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015) in R (R Core Team 2021). In this model, response (expected = 1, unexpected = 0) was the dependent variable while condition (canonical or negative imperative), MiNT scores and SRLFT-based lexical frequency counts were the independent variables. The two last independent variables were continuous and were standardized. Additionally, the model also tested for all possible two-way interactions as well as one three-way interaction. Finally, the model included random intercepts for each subject as well as for each lexical item.

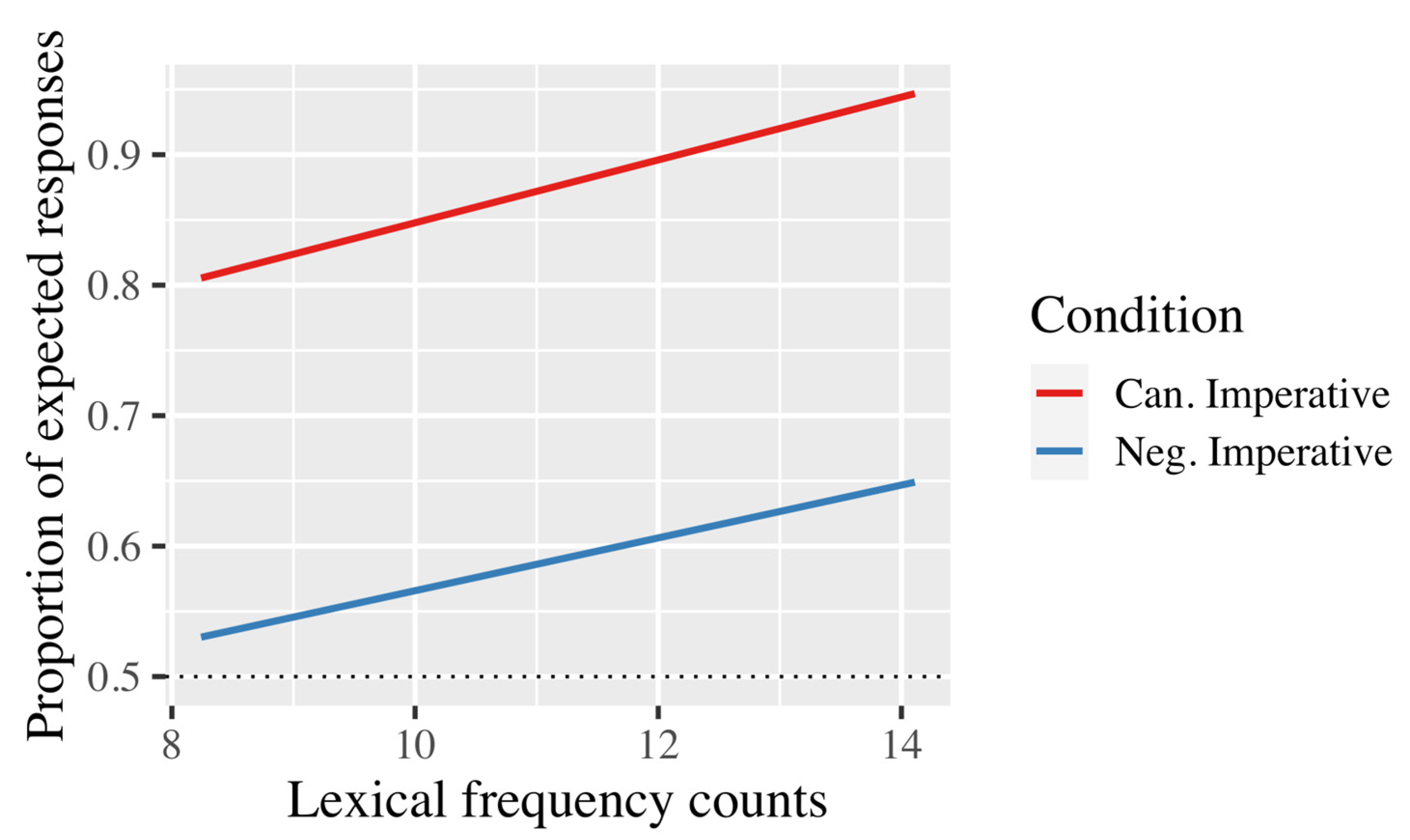

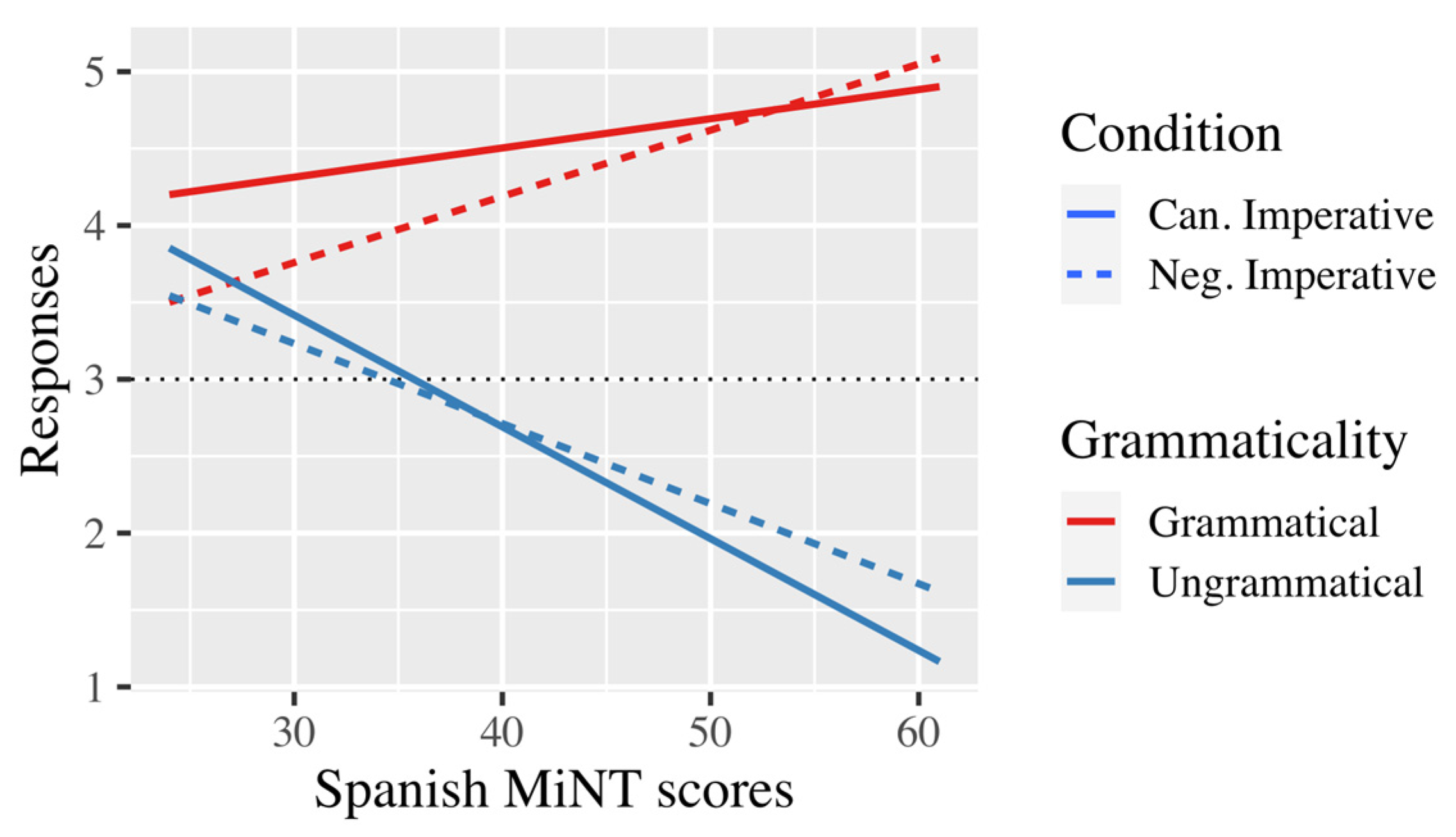

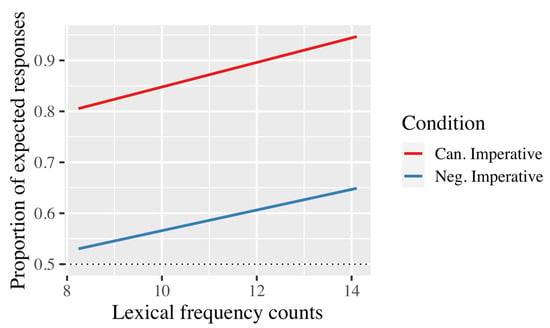

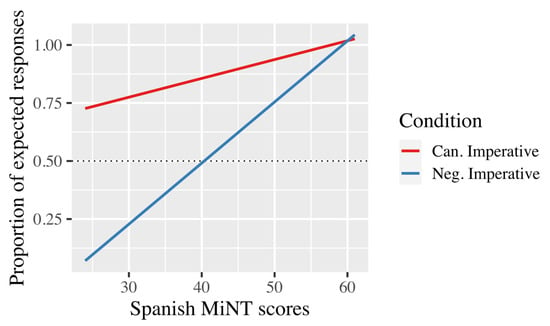

The results of the GLMM determined that the heritage speakers’ expected responses were predicted by condition (β = −2.79, SE = 0.41, z = −6.84, p < 0.01), their MiNT scores (β = 1.53, SE = 0.53, z = 2.88, p < 0.01), and lexical frequency (β = 1.11, SE = 0.50, z = 2.21, p = 0.03) of the verb included in each test item. Specifically, this output indicates that heritage speakers produced more variable responses in the negative imperative condition. Additionally, heritage speakers with deeper productive vocabulary knowledge produced more instances of expected responses across conditions. Finally, frequent verbs facilitated the production of expected responses, as opposed to less frequent verbs, which led to variability in the heritage speakers’ productive knowledge. Figure 3 below shows the effect of lexical frequency across conditions among the heritage speakers.

Figure 3.

Lexical frequency effects on the heritage speakers’ EPT responses across conditions.

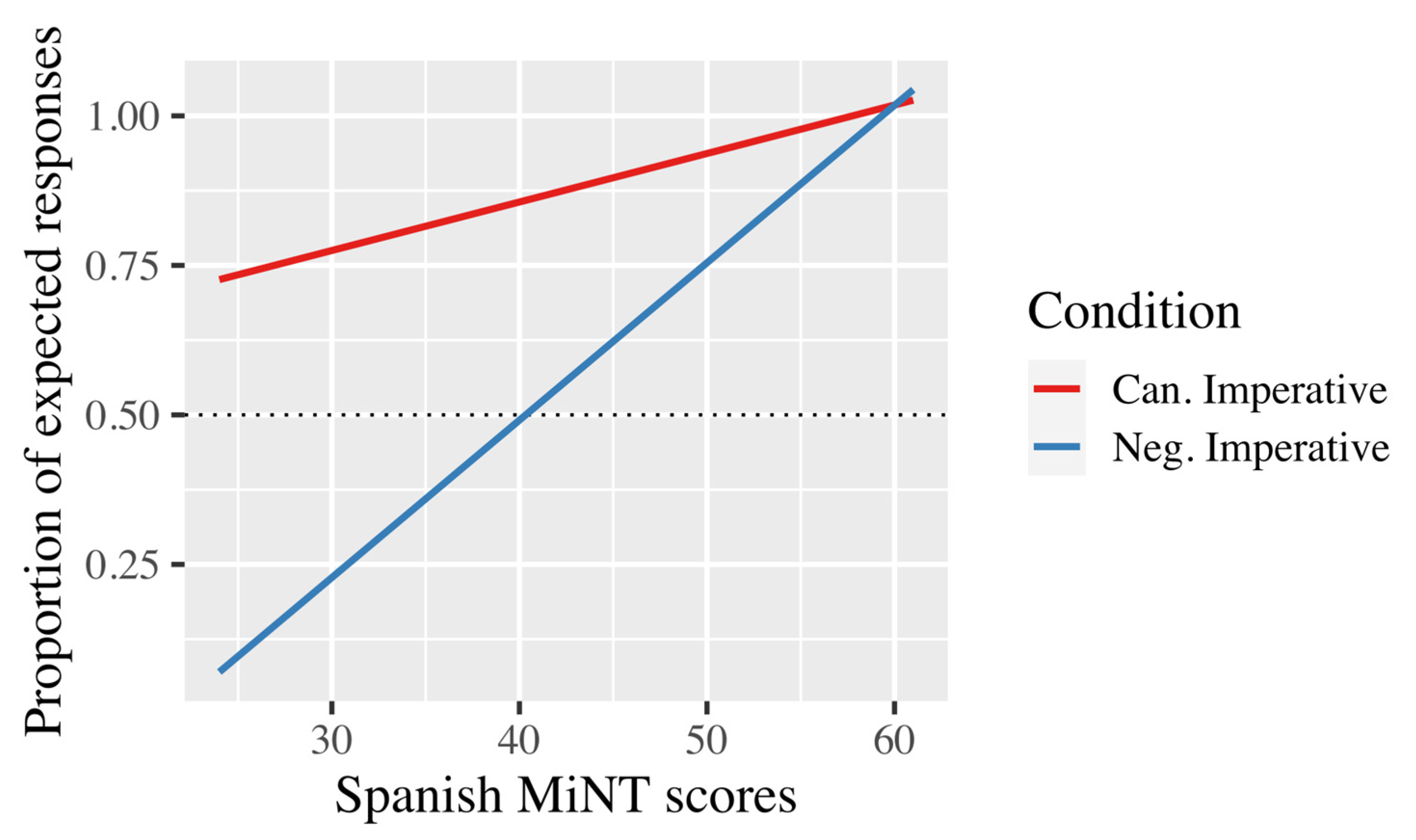

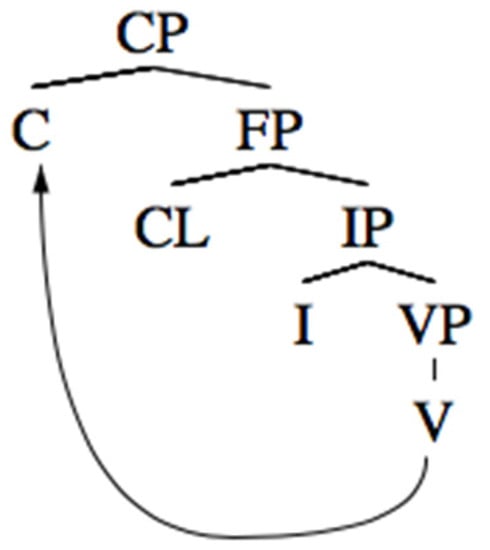

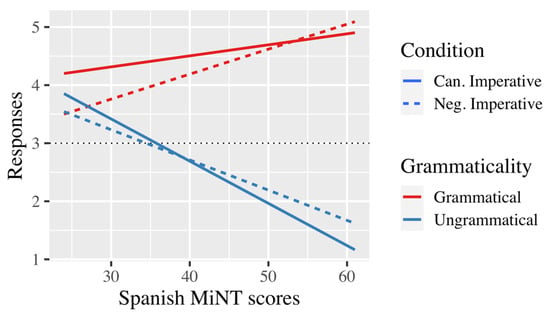

Furthermore, an interaction between condition and MiNT scores (β = 1.58, SE = 0.47, z = 3.34, p < 0.01) suggests that the effect of productive vocabulary knowledge on the production of expected responses is stronger in the negative imperative condition than in the canonical imperative condition, which did not generate as much variability. No other interactions were found to be significant. Figure 4 below shows the interaction between condition and MiNT scores.

Figure 4.

Spanish MiNT scores effects on the heritage speakers’ EPT responses across conditions.

In sum, the results from the EPT indicate that accuracy in the production of negative imperatives is shaped by the heritage speaker’s proficiency as measured by their productive vocabulary knowledge, and the verb in the imperative clause, particularly how frequent said verb is in the heritage speakers’ input and output. As the goal of the current study is to examine the acquisition of imperatives among heritage speakers as well as the factors that shape their acquisition, no statistical model was run to analyze between-group effects between the heritage speakers and the Spanish-dominant bilinguals, whose productive knowledge of imperatives did not show strong signs of variability.

5.2. Acceptability Judgment Task

The results from the AJT indicate that the heritage speakers’ receptive grammatical knowledge was more categorical when facing grammatical test items while their responses showed signs of variability when judging ungrammatical sentences. The Spanish-dominant bilinguals, on the other hand, rated both grammatical and ungrammatical sentences categorically, as expected. Table 4 shows the counts of the ratings assigned by both groups across grammaticality and conditions.

Table 4.

Counts and proportions of the ratings assigned by heritage speakers and Spanish-dominant bilinguals across grammaticality and conditions.

The data from the AJT were analyzed using an ordinal regression, which was performed by using the clmm (cumulative link mixed model) function of the ordinal package (Christensen 2015) in R (R Core Team 2021) in order to explore what factors predict the receptive grammatical knowledge of heritage speakers. This ordinal model included response (1, 2, 3, 4, or 5) as the dependent variable and grammaticality (grammatical or ungrammatical), condition (canonical or negative imperative), MiNT scores and SRLFT-based lexical frequency counts as independent variables. As in the GLMM used to analyze the EPT data, the two last independent variables were continuous and were standardized whereas grammaticality and condition were categorical. This ordinal model explored two two-way interactions: grammaticality x condition as well as grammaticality x MiNT scores. This ordinal model included random intercepts for each participant and for each lexical item.

The ordinal model yielded that the heritage speakers’ receptive grammatical knowledge is predicted by grammaticality (β = −4.83, SE = 0.32, z = −14.91, p < 0.01), condition (β = −0.64, SE = 0.25, z = −2.54, p = 0.01), and their productive vocabulary knowledge as measured by their MiNT scores (β = 1.11, SE = 0.26, z = 4.23, p < 0.01). However, lexical frequency was not found to shape their acceptability judgments (β = −0.02, SE = 0.12, z = −0.18, p = 0.86). These effects suggest (1) that heritage speakers were sensitive to the grammaticality of the test items and rated ungrammatical test items lower; (2) that negative imperatives received lower ratings than canonical imperatives, a sign that the heritage speakers’ receptive grammatical knowledge of canonical imperatives may be more stable than that of negative imperatives; and (3) that heritage speakers with higher productive vocabulary knowledge, used as a proxy for overall proficiency in this study, gave higher ratings overall.

The model also found two significant two-way interactions. First, within the ungrammatical test items, negative imperatives received higher ratings than canonical imperatives (β = 0.77, SE = 0.34, z = 2.28, p = 0.02). This indicates that the heritage speakers’ responses were more decisive when judging canonical imperatives as either grammatical or ungrammatical whereas ratings of negative imperatives did not present such contrast. Second, a negative interaction between grammaticality and MiNT scores (β = −2.46, SE = 0.22, z = −11.36, p < 0.01) indicates that the heritage speakers assigned higher ratings to ungrammatical test items as their MiNT scores decreased. In other words, heritage speakers with lower productive vocabulary knowledge rejected ungrammatical test items less than their counterparts with higher productive vocabulary knowledge. Figure 5 below shows the effect of MiNT scores on the heritage speakers’ AJT responses across grammaticality and conditions. For visualization purposes, this plot shows the AJT responses as a continuous variable.

Figure 5.

Spanish MiNT scores effects on the heritage speakers’ AJT responses across grammaticality (red vs. blue lines) and conditions (solid vs. dashed lines).

Succinctly, the heritage speakers’ receptive grammatical knowledge is modulated by the grammaticality and the condition of the imperative clause under examination (canonical or negative imperative) as well as by the heritage speakers’ productive vocabulary knowledge. Lexical frequency, nevertheless, does not play a role in their receptive grammatical knowledge. These results present asymmetries with regard to the EPT results as the heritage speakers’ productive knowledge of imperatives in Spanish is modulated by the lexical frequency of the main verb of the imperative clause in addition to condition (canonical or negative imperative) and productive vocabulary knowledge. No models were run to assess between-group comparisons or to explore within-group effects within the Spanish-dominant bilinguals as that is not the scope of the present study. Appendix F includes the outputs of the regressions performed for this study.

6. Discussion

This exploratory study aimed to examine the acquisition of the morphosyntactic and syntactic properties of the Spanish imperatives among English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish in the United States. Three research questions guided our study. RQ1 inquired about the acquisition patterns of the phenomena under examination among the heritage speakers of Spanish. The researcher hypothesized that their knowledge of these phenomena in their heritage Spanish would show signs of variability in both their productive and receptive grammatical knowledge as a result of the restructuring of heritage language features (Putnam and Sánchez 2013). The researcher predicted that this would be reflected in their EPT and AJT responses, which would show signs of cross-linguistic influence from their dominant language, English, in that heritage speakers would treat Spanish imperatives as Class II imperatives instead of as Class I imperatives. In other words, they would use the same verb form, as well as its syntactic properties, in both canonical and negative imperative clauses.

The results indicate that most of the variability found in the heritage speakers’ responses in both their productive and receptive grammatical knowledge is restricted to negative imperatives. In their productive knowledge as measured by the EPT, the heritage speakers produced more expected responses in the canonical imperative condition than in the negative imperative condition. As shown in Appendix E, the heritage speakers produced a wide range of different and innovative verb morphology and object forms. Their AJT responses indicate that, while the negative imperative condition shows more variability given the tighter gap in their ratings to grammatical and ungrammatical negative imperative test items, the ordinal model determined that, overall, their ratings are predicted by the grammaticality of the test items that they are judging. Therefore, their knowledge of imperatives in Spanish shows signs of asymmetry: their receptive grammatical knowledge seems to be more stable than their productive knowledge, which is more variable (Putnam and Sánchez 2013). These asymmetrical results are widely found in L2 studies (e.g., Ellis 2005a, 2005b; Geeslin and Gudmestad 2008; Shiu et al. 2018). In sum, the hypothesis formulated for RQ1 is not confirmed by the results of the current study: while the heritage speakers’ knowledge of negative imperatives does show signs of variability, which could indicate cross-linguistic influence from English, the fact that their receptive grammatical knowledge is sensitive to the grammaticality of the test items under examination excludes this possibility.

RQ2 aimed to investigate whether the heritage speakers’ productive vocabulary knowledge as measured by their Spanish MiNT scores predict their acquisition of Spanish imperatives. The researcher hypothesized that their productive vocabulary knowledge would go hand in hand with their knowledge of Spanish imperatives as examined with the use of productive and receptive tasks. Previous studies have found that productive vocabulary knowledge or lexical access is correlated with overall proficiency (Bedore et al. 2012; Gollan et al. 2012; Sheng et al. 2014; Treffers-Daller and Korybski 2015). The results from both the EPT and the AJT confirm the hypothesis formulated for RQ2: productive vocabulary knowledge predicts the knowledge of Spanish imperatives. Heritage speakers with higher Spanish MiNT scores showed more stable productive and receptive grammatical knowledge of Spanish imperatives whereas those with lower MiNT scores showed more signs of variability, particularly in their production. These findings are congruous with previous studies on heritage Spanish that have also documented that Spanish MiNT scores can predict the acquisition of (morpho)syntax (e.g., Hur 2020, 2022; Hur et al. 2020; López Otero 2022). Due to the rather consistent results in the production of canonical imperatives as opposed to the variability found in the heritage speakers’ production of negative imperatives, Spanish MiNT scores predicted the responses in the negative imperative condition of the EPT yet not in the canonical imperative condition. The contrast between these two conditions stems from differences in syntactic complexity and the computational costs associated to said complexity.

Finally, RQ3 focused on lexical frequency effects on the acquisition of the phenomenon under examination in this study. Consistent with Putnam and Sánchez’s (2013) activation approach, which claims that the patterns of heritage language activation and inhibition play a role in its restructuring, the researcher hypothesized that within-subject variability could, at least partially, be accounted for by the lexical frequency of the verbs featured in the test items. The results confirm this hypothesis given that lexical frequency modulates the heritage speakers’ productive knowledge yet does not play a role in their receptive grammatical knowledge. Specifically, the heritage speakers show more stable knowledge with frequent words versus more variability with infrequent lexical items. Previous studies that have also used lexical frequency as a proxy for heritage language activation have found lexical frequency effects on the acquisition of heritage language grammars in both productive and receptive grammatical knowledges (e.g., Giancaspro 2017; Hur 2022; Perez-Cortes and Giancaspro 2022) or in production exclusively (e.g., Goldin et al. 2023; Hur 2020; Hur et al. 2020; López Otero 2022).

Overall, the answers to the research questions indicate that the acquisition of Spanish imperatives among English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish is compatible with Putnam and Sánchez’s (2013) activation approach. The heritage speakers’ patterns of heritage language activation have led to a rather stable receptive grammatical knowledge. Recall that, despite showing a less defined contrast between grammatical and ungrammatical items belonging to the negative imperative condition, the heritage speakers’ AJT responses were predicted by the grammaticality of the test items. On the other hand, their productive knowledge showed stronger signs of innovation and variability, particularly among heritage speakers with lower productive vocabulary knowledge and with test items featuring less-frequent verbs. Taken together, these findings, particularly those from the AJT, indicate that the heritage speakers’ mental representation of Spanish imperatives has not undergone a restructuring process. Nevertheless, this group of heritage speakers experiences difficulties in accessing mental representations of their heritage language for production purposes (Perez-Cortes et al. 2019). This view is supported by the asymmetry between productive and receptive grammatical knowledge, the effects of productive vocabulary knowledge—or lexical access—and the lexical frequency effects found in their production. Furthermore, the syntactic complexity involved in the production of negative imperatives and the computational costs associated to such complexity may be another reason accounting for the variability in the heritage speakers’ production (e.g., Camacho and Kirova 2018; López Otero 2022).

7. Conclusions

The present study found that the acquisition of Spanish imperatives among English-speaking heritage speakers of Spanish is shaped by the heritage speakers’ productive vocabulary knowledge, the lexical frequency of the verbs featured in the test items and by the syntactic complexity of the phenomenon under examination. Specifically, most of the variability in the data was restricted to the productive knowledge of negative imperatives, which are syntactically more complex than canonical imperatives.

Further research should investigate individual differences, particularly among low-proficiency heritage speakers, in order to determine whether their receptive grammatical knowledge has undergone a restructuring process. Additionally, future projects could perform a fine-grained analysis of all the EPT responses with a focus on within-subject variability and innovation. Nevertheless, this study is not without limitations. First, most of the heritage speakers were considered advanced as per their DELE scores, which hinders our capability to draw conclusions from low-proficiency heritage speakers, who may show signs of heritage language restructuring. Second, as the SRLFT was conducted during the same session as the other tasks, it was not possible to control the lexical frequency counts and ranges for the verbs featured in the test items prior to the data collection session. Finally, collecting data from the heritage speakers’ family and community members would confirm that they are not exposed to innovative imperative verb forms.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rutgers University (protocol number Pro2018002198, approved on 9 September 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the participants for their time.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Elicited Production Task

- Condition A: canonical imperatives.

- A1. Felipe te dice: Tengo un estudiante muy desobediente en mi clase.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Felipe, ! (echar)

- A2. Marta te dice: El villano de este videojuego no me permite avanzar.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Marta, ! (matar)

- A3. Felipe te dice: Quiero volver a ver a mi amigo, pero me ignora.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Felipe, ! (dejar)

- A4. Felipe te dice: Mi amigo se ha enojado conmigo y no sé qué hacer.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Felipe, ! (llamar)

- A5. Felipe te dice: ¡Mi hermano se ha perdido y estoy desesperado!

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Felipe, ! (buscar)

- A6. Felipe te dice: Mi hermano tiene problemas y necesita ayuda.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Felipe, ! (ayudar)

- Condition B: negative imperatives.

- B1. Felipe te dice: En mi empresa tengo un trabajador mediocre, pero acaba de tener un bebé.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Felipe, ! (no echar)

- B2. Felipe te dice: ¡Qué extraño! El villano de este videojuego me intenta ayudar. ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Felipe, ! (no matar)

- B3. Marta te dice: Fernando y yo tenemos algunos problemas, pero nos queremos. ¡No sé qué hacer!

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Marta, ! (no dejar)

- B4. Marta te dice: Quiero hablar con mi amigo, pero él dice que soy una pesada… ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Marta, ! (no llamar)

- B5. Felipe te dice: Quiero reunirme con mi amigo, pero tiene la gripe.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Felipe, ! (no buscar)

- B6. Marta te dice: Mi amigo me ha pedido dinero de nuevo.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- ¡Marta, ! (no ayudar)

Appendix B. Acceptability Judgment Task (Versions 1 and 2)

- Condition A: canonical imperatives.

- A1. Felipe te dice: Tengo un estudiante muy desobediente en mi clase.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Felipe, échalo!

- Version 2: ¡Felipe, lo echa!

- A2. Marta te dice: El villano de este videojuego no me permite avanzar.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Marta, mátalo!

- Version 2: ¡Marta, lo mata!

- A3. Felipe te dice: Quiero volver a ver a mi amigo, pero me ignora.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Felipe, déjalo!

- Version 2: ¡Felipe, lo deja!

- A4. Felipe te dice: Mi amigo se ha enojado conmigo y no sé qué hacer.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Felipe, lo llama!

- Version 2: ¡Felipe, llámalo!

- A5. Felipe te dice: ¡Mi hermano se ha perdido y estoy desesperado!

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Felipe, lo busca!

- Version 2: ¡Felipe, búscalo!

- A6. Felipe te dice: Mi hermano tiene problemas y necesita ayuda.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Felipe, lo ayuda!

- Version 2: ¡Felipe, ayúdalo!

- Condition B: negative imperatives.

- B1. Felipe te dice: En mi empresa tengo un trabajador mediocre, pero acaba de tener un bebé.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Felipe, no échalo!

- Version 2: ¡Felipe, no lo eches!

- B2. Felipe te dice: ¡Qué extraño! El villano de este videojuego me intenta ayudar.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Felipe, no mátalo!

- Version 2: ¡Felipe, no lo mates!

- B3. Marta te dice: Fernando y yo tenemos algunos problemas, pero nos queremos. ¡No sé qué hacer!

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Marta, no déjalo!

- Version 2: ¡Marta, no lo dejes!

- B4. Marta te dice: Quiero hablar con mi amigo, pero él dice que soy una pesada.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Marta, no lo llames!

- Version 2: ¡Marta, no llámalo!

- B5. Felipe te dice: Quiero reunirme con mi amigo, pero tiene la gripe.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Felipe, no lo busques!

- Version 2: ¡Felipe, no búscalo!

- B6. Marta te dice: Mi amigo me ha pedido dinero de nuevo.

- ¿Qué le sugieres?

- Version 1: ¡Marta, no lo ayudes!

- Version 2: ¡Marta, no ayúdalo!

Appendix C. EPT and AJT Test Item Samples

- A.

- EPT test item sample

- B.

- AJT test item sample

Appendix D. Self-Rating Lexical Frequency Test Counts Provided by the Heritage Speakers

| Ayudar | 13.58/18 |

| Buscar | 12.84/18 |

| Dejar | 11.42/18 |

| Echar | 10.29/18 |

| Llamar | 14.11/18 |

| Matar | 8.24/18 |

Appendix E

- A.

- Distribution of the heritage speakers’ EPT responses

| Forms | Condition | |||

| Verb Form | Object Form | Example | Canonical Imperative | Negative Imperative |

| Imperative | DP | ¡Llama a tu amigo! | 29/336 (8.63%) | 11/336 (3.27%) |

| Imperative | Enclitic | ¡Déjalo! | 270/336 (80.36%) | 23/336 (6.85%) |

| Imperative | Null clitic | ¡No busca! | 23/336 (6.85%) | 21/336 (6.25%) |

| Imperative | Proclitic | ¡Lo deja!, ¡No lo ayuda! | 1/336 (0.30%) | 8/336 (2.38%) |

| Present Indicative | DP | ¡No buscas tu amigo! | 0/336 (0%) | 2/336 (0.60%) |

| Present Indicative | Enclitic | ¡No le ayudas! | 0/336 (0%) | 1/336 (0.30%) |

| Present Indicative | Null clitic | ¡No buscas! | 0/336 (0%) | 23/336 (6.85%) |

| Present Indicative | Proclitic | ¡No lo dejas! | 0/336 (0%) | 11/336 (3.27%) |

| Present Subj. (Usted) | Null clitic | ¡No mate! | 0/336 (0%) | 1/336 (0.30%) |

| Present Subj. (Usted) | Proclitic | ¡No lo ayude! | 0/336 (0%) | 3/336 (0.89%) |

| Present Subj. (Tú) | DP | ¡No eches al trabajador! | 0/336 (0%) | 7/336 (2.08%) |

| Present Subj. (Tú) | Null clitic | ¡No mates! | 0/336 (0%) | 20/336 (5.95%) |

| Present Subj. (Tú) | Proclitic | ¡No lo dejes! | 0/336 (0%) | 192/336 (57.14%) |

| Infinitive | DP | ¡No dejar a Fernando! | 0/336 (0%) | 1/336 (0.30%) |

| Infinitive | Enclitic | ¡Buscarlo! | 4/336 (1.19%) | 1/336 (0.30%) |

| Infinitive | Null clitic | ¡No matar! | 4/336 (1.19%) | 2/336 (0.60%) |

| Infinitive | Proclitic | ¡Echarlo! | 1/336 (0.30%) | 0/336 (0%) |

| Other | Enclitic | Debería matarlo. | 4/336 (1.19%) | 4/336 (1.19%) |

| Other | Null clitic | ¡No matará! | 0/336 (0%) | 2/336 (0.60%) |

| Other | Proclitic | ¡No le dejarás! | 0/336 (0%) | 3/336 (0.89%) |

| Total: | 336/336 (100%) | 336/336 (100%) | ||

- B.

- Distribution of the Spanish-dominant bilinguals’ EPT responses

| Forms | Condition | |||

| Verb Form | Object Form | Example | Canonical Imperative | Negative Imperative |

| Imperative | DP | ¡Busca a tu hermano! | 10/150 (6.67%) | 0/150 (0%) |

| Imperative | Enclitic | ¡Déjalo! | 135/150 (90%) | 0/150 (0%) |

| Imperative | Null clitic | ¡No ayuda! | 5/150 (3.33%) | 3/150 (2%) |

| Present Subj. (Usted) | Null clitic | ¡No llame! | 0/150 (0%) | 1/150 (0.67%) |

| Present Subj. (Tú) | DP | ¡No busques a tu amigo! | 0/150 (0%) | 6/150 (4%) |

| Present Subj. (Tú) | Null clitic | ¡No mates! | 0/150 (0%) | 2/150 (1.33%) |

| Present Subj. (Tú) | Proclitic | ¡No lo ayudes! | 0/150 (0%) | 138/150 (92%) |

| Total: | 150/150 (100%) | 150/150 (100%) | ||

Appendix F. Regression Outputs

- A.

- GLMM output (EPT data)

GLMM output (EPT data). Reference value for condition: canonical imperative.

| Fixed Factor | Estimate | SE | Z Value | p Value |

| (Intercept) | 4.39022 | 0.63990 | 6.861 | <0.001 * |

| Condition (Negative imperative) | −2.78639 | 0.40758 | −6.836 | <0.001 * |

| MiNT scores | 1.52598 | 0.53064 | 2.876 | 0.004031 * |

| Lexical frequency scores | 1.10959 | 0.50270 | 2.207 | 0.027295 * |

| Condition (Negative imperative) × MiNT scores | 1.58014 | 0.47357 | 3.337 | 0.000848 * |

| Condition (Negative imperative) × Lexical frequency scores | −0.38359 | 0.47378 | −0.810 | 0.418147 |

| MiNT scores × Lexical frequency scores | 0.03503 | 0.37867 | 0.093 | 0.926291 |

| Condition (Negative imperative) × MiNT scores × Lexical frequency scores | 0.34296 | 0.50322 | 0.682 | 0.495534 |

- B.

- Ordinal regression output (AJT data)

Ordinal regression output (AJT data). Reference value for grammaticality: grammatical. Reference value for condition: canonical imperative.

| Fixed Factor | Estimate | SE | Z Value | p Value |

| Grammaticality (Ungrammatical) | −4.82718 | 0.32371 | −14.912 | < 0.001 * |

| Condition (Negative imperative) | −0.64016 | 0.25248 | −2.535 | 0.0112 * |

| MiNT scores | 1.11413 | 0.26339 | 4.230 | < 0.001 * |

| Lexical frequency scores | −0.02252 | 0.12487 | −0.180 | 0.8569 |

| Grammaticality (Ungrammatical) × Condition (Negative imperative) | 0.76658 | 0.33618 | 2.280 | 0.0226 * |

| Grammaticality (Ungrammatical) × MiNT scores | −2.45606 | 0.21619 | −11.361 | < 0.001 * |

References

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra. 2010. Imperatives and Commands. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alcázar, Asier, and Mario Saltarelli. 2014. The Syntax of Imperatives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, Douglas, Reinhold Kliegl, Shravan Vasishth, and Harald Baayen. 2015. Parsimonious Mixed Models. arXiv arXiv:1506.04967. [Google Scholar]

- Bedore, Lisa M., Elizabeth D. Peña, Connie L. Summers, Karin M. Boerger, Maria D. Resendiz, Kai Greene, Thomas M. Bohman, and Ronald B. Gillam. 2012. The measure matters: Language dominance profiles across measures in Spanish-English bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 616–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukema, Frits, and Peter Coopmans. 1989. A Government-Binding perspective on the imperative in English. Journal of Linguistics 25: 417–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birjulin, Leonid A., and Victor S. Xrakovskij. 2001. Imperative sentences: Theoretical problems. In Typology of Imperative Constructions. Edited by Victor S. Xrakovskij. Munich: Lincom Europa, pp. 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, José, and Alena Kirova. 2018. Adverb placement among heritage speakers of Spanish. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3: 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Rune H. B. 2015. Ordinal—Regression Models for Ordinal Data. R Package Version 2019.3–9. Available online: http://www.cran.r-project.org/package=ordinal/ (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Cuza, Alejandro. 2013. Crosslinguistic influence at the syntax proper: Interrogative subject–verb inversion in heritage Spanish. International Journal of Bilingualism 17: 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro, Ana Teresa Pérez-Leroux, and Liliana Sánchez. 2013. The role of semantic transfer in clitic-drop among simultaneous and sequential Chinese-Spanish bilinguals. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 35: 93–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro, and Joshua Frank. 2011. Transfer effects at the syntax-semantics interface: The case of double-que questions in heritage Spanish. The Heritage Language Journal 8: 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro, and Rocío Pérez-Tattam. 2015. Grammatical gender selection and phrasal word order in child heritage Spanish: A feature re-assembly approach. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19: 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, Nigel, and Lydia White. 1999. Assessing L2 knowledge of Spanish clitic placement: Converging methodologies. Second Language Research 15: 133–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rod. 2005a. Measuring implicit and explicit knowledge of a second language. A psychometric study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 27: 141–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rod. 2005b. Planning and task-based research: Theory and research. In Planning and Task-Performance in a Second Language. Edited by Rod Ellis. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeizabarrena, María José. 1997. Imperativos en el lenguaje de los niños bilingües. In Actas do I simposio internacional sobre o bilingüismo. Vigo: Servicio de Publicacións da Universidade de Vigo, pp. 328–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole, Virginia, Eugenia Sebastián, and Pilar Soto. 1999. The early acquisition of Spanish verbal morphology: Across-the-board or piecemeal knowledge? The International Journal of Bilingualism 3: 133–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, Virginia, Eugenia Sebastián, and Pilar Soto. 2002. Negative commands in Spanish-speaking children: No need for recourse to relativized minimality. Journal of Child Language 29: 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geeslin, Kimberly L., and Aarnes Gudmestad. 2008. Comparing interview and written elicitation tasks in native and non-native data: Do speakers do what we think they do? In Selected Proceedings of the 10th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Joyce Bruhn de Garavito and Elena Valenzuela. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Giancaspro, David. 2017. Heritage Speakers’ Production and Comprehension of Lexically- and Contextually Selected Subjunctive Mood Morphology. Ph.D. dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, Michele. 2020. An exploratory study of the effect of Spanish immersion education on the acquisition of pronominal subjects in child heritage speakers. Languages 5: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, Michele, Julio César López Otero, and Esther Hur. 2023. How frequent are these verbs?: An exploration of lexical frequency in bilingual children’s acquisition of subject-verb agreement morphology. Isogloss: Open Journal of Romance Linguistics 9: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, Tamar H., Gali H. Weissberger, Elin Runnqvist, Rosa I. Montoya, and Cynthia M. Cera. 2012. Self-ratings of spoken language dominance: A Multilingual Naming Test (MINT) and preliminary norms for young and aging Spanish–English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granström, Johan G. 2011. Treatise on Intuitionistic Type Theory. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Grinstead, John. 1998. Subjects, Sentential Negation and Imperatives in Child Spanish and Catalan. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, James. 1997. There is no imperative paradigm in Spanish. In Issues in the Phonology and Morphology of the Major Iberian Languages. Edited by Fernando Martinez-Gil and Alfonso Morales-Front. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 537–57. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, James. 1998. Spanish imperatives: Syntax meets morphology. Journal of Linguistics 34: 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Esther. 2020. Verbal lexical frequency and DOM in heritage speakers of Spanish. In The Acquisition of Differential Object Marking. Edited by Alexandru Mardale and Silvina Montrul. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 207–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, Esther. 2022. The Effects of Lexical Properties of Nouns and Verbs on L2 and Heritage Differential Object Marking. Ph.D. dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, Esther, Julio Cesar Lopez Otero, and Liliana Sanchez. 2020. Gender agreement and assignment in Spanish heritage speakers: Does frequency matter? Languages 5: 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2008. Feature-assembly in second language acquisition. In The Role of Formal Features in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Juana Liceras, Helmut Zobl and Helen Goodluck. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 106–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2009. Some thoughts on the contrastive analysis of features in second language acquisition. Second Language Research 25: 173–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Benjamin J., Nathan D. McVeigh, Alejandra Marful, and Michael C. Anderson. 2007. Inhibiting your native language: The role of retrieval-induced forgetting during second-language acquisition. Psychological Science 18: 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linck, Jared A., Judith F. Kroll, and Gretchen Sunderman. 2009. Losing access to the native language while immersed in a second language: Evidence for the role of inhibition in second-language learning. Psychological Science 20: 1507–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Otero, Julio Cesar. 2022. Lexical frequency effects on the acquisition of syntactic properties in heritage Spanish: A study on unaccusative and unergative predicates. Heritage Language Journal 19: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Otero, Julio César, Alejandro Cuza, and Jian Jiao. 2021. Object clitic use and intuition in the Spanish of heritage speakers from Brazil. Second Language Research 39: 02676583211017603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Otero, Julio César, Esther Hur, and Michele Goldin. 2023. Syntactic optionality in heritage Spanish: How patterns of exposure and use affect clitic climbing. International Journal of Bilingualism, 13670069231170691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2004. Subject and object expression in Spanish heritage speakers: A case of morphosyntactic convergence. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 125–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Roumyana Slabakova. 2003. Competence similarities between native and near-native speakers: An investigation of the preterite-imperfect contrast in Spanish. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 25: 351–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual y Cabo, Diego, and Inmaculada Gómez Soler. 2015. Preposition stranding in Spanish as a heritage language. Heritage Language Journal 12: 186–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cortes, Silvia. 2022. Lexical frequency and morphological regularity as sources of heritage speaker variability in the acquisition of mood. Second Language Research 38: 149–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cortes, Silvia, and David Giancaspro. 2022. (In) frequently asked questions: On types of frequency and their role (s) in heritage language variability. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1002978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cortes, Silvia, Michael T. Putnam, and Liliana Sánchez. 2019. Differential Access: Asymmetries in Accessing Features and Building Representations in Heritage Language Grammars. Languages 4: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portner, Paul. 2016. Imperatives. In Cambridge Handbook of Semantics. Edited by Maria Aloni and Robert van Rooij. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Potsdam, Eric. 1998. Syntactic Issues in the English Imperative. Outstanding Dissertations in Linguistics. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Michael T., and Lara Schwarz. 2014. How interrogative pronouns can become relative pronouns: The case of was in Misionero German. STUF-Sprachtypologie Und Universalienforschung 67: 613–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Michael T., and Liliana Sánchez. 2013. What’s so incomplete about incomplete acquisition? A prolgomenon to modeling heritage grammars. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3: 478–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Michael T., Silvia Perez-Cortes, and Liliana Sánchez. 2019. Language attrition and the Feature Reassembly Hypothesis. In The Oxford Handbook of Language Attrition. Edited by Barbara Köpke and Monika Schmid. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Rivero, María Luisa, and Arhonto Terzi. 1995. Imperatives, V-Movement and Logical Mood. Journal of Linguistics 2: 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, John R. 1979. Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seton, Bregtje, and Monika S. Schmid. 2016. Multi-competence and first language attrition. In The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Multi-Competence. Edited by Vivian Cook and Li Wei. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 338–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Li, Ying Lu, and Tamar H. Gollan. 2014. Assessing language dominance in Mandarin–English bilinguals: Convergence and divergence between subjective and objective measures. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 17: 364–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Naomi, Alejandro Cuza, and Liliana Sánchez. 2023. Structured variation, language experience, and crosslinguistic influence shape child heritage speakers’ Spanish direct objects. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 26: 317–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiu, Li-Ju, Şebnem Yalçin, and Nina Spada. 2018. Exploring second language learners’ grammaticality judgment performance in relation to task design features. System 72: 215–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffers-Daller, Jeanine, and Tomasz Korybski. 2015. Using lexical diversity measures to operationalise language dominance in bilinguals. In Language Dominance in Bilinguals: Issues of Measurement and Operationalization. Edited by Carmen Silva-Corvalan and Jeanine Treffers-Daller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 106–23. [Google Scholar]

- van Osch, Brechje. 2019. Vulnerability and cross-linguistic influence in heritage Spanish: Comparing different majority languages. Heritage Language Journal 16: 340–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, Lisa. 2016. Morphosyntactic Variation and Change in Wisconsin Heritage German. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Yager, Lisa, Nora Hellmold, Hyoun-A. Joo, Eleonora Rossi, Catherine Stafford, and Joe Salmons. 2015. New structural patterns in moribund grammar: Case marking in heritage German. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanuttini, Raffaella. 1996. On the relevance of tense for sentential negation. In Parameters and Functional Heads. Essays in Comparative Syntax. Edited by Adriana Belletti and Luigi Rizzi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 181–207. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).