Abstract

People often think about how they are perceived by others, but their perceptions (described as metaperceptions) are frequently off-target. Speakers communicating in their first language demonstrate a robust phenomenon, called the liking gap, where they consistently underestimate how much they are liked by their interlocutors. We extended this research to second language (L2) speakers to determine whether they demonstrate a similar negative bias and if it predicts willingness to engage in future interactions. We paired 76 English L2 university students with a previously unacquainted student to carry out a 10 min academic discussion task in English. After the conversation, students rated each other’s interpersonal liking, speaking skill, and interactional behavior, provided their metaperceptions for their partner’s ratings of the same dimensions, and assessed their willingness to engage in future interaction. We found a reliable interpersonal liking gap for all speakers, along with speaking skill and interaction behavior gaps for female speakers only. Only the female speakers (irrespective of their partner’s gender) seemed to factor metaperceptions into their willingness to engage in future communication. We discuss the implications of these initial findings and call for further work into the role of metaperception in L2 communication.

1. Introduction

People often think and even worry about how they are perceived by others, ranging from their family and friends to acquaintances and casual observers. Broadly described as metaperceptions (Carlson and Barranti 2016), their perceptions are far from perfectly accurate. In fact, people’s metaperceptions are often notoriously off-target when compared with how people are actually seen by others (Carlson and Kenny 2012). For example, speakers overestimate the degree to which their nervousness is perceptible to observers (Cameron et al. 2011; Savitsky and Gilovich 2003). Similarly, people who pay a compliment or offer help tend to underestimate the extent to which the receivers of these prosocial acts appreciate them, whereas individuals receiving help overestimate the degree to which those providing it feel inconvenienced (Dungan et al. 2022; Zhao and Epley 2021). In this study, we focused on another social domain, interpersonal liking, where metaperceptions have been shown to be inaccurate (Boothby et al. 2018; Elsaadawy and Carlson 2022). Speakers often underestimate how much they are liked, and this bias might preclude them from pursuing future interaction with their interlocutors (Mastroianni et al. 2021). We extend this work from interactions between first language (L1) speakers to conversations between second language (L2) speakers (university students performing an academic discussion task), examining whether speakers’ metaperception is related to their expected future behavior. Our aim is to highlight metaperception as a variable relevant to the social dynamics of L2 interaction.

1.1. Background Literature

People’s sense of self is created and maintained in the social domain, and their metaperceptions (or the impressions they believe to make on others) provide a roadmap for them to navigate their relationships and actions (Kenny 2019; Tice and Wallace 2003). For instance, in the workplace, metaperceptions appear to shape employee behavior, in the sense that coworkers who believe they are lacking in confidence, competence, or skill in the eyes of their colleagues might abstain from otherwise beneficial actions, such as speaking up at meetings or pursuing a promotion (Byron and Landis 2020; Mastroianni et al. 2021). Similarly, individuals holding particular political views tend to have an exaggerated perception of the hostility shown toward them from those supporting a different political agenda, and these biased metaperceptions lead to spiteful, harmful behaviors against political opponents (Moore-Berg et al. 2020). And in the personal domain, accurate metaperceivers are considered more likeable by others, both after an initial conversation and in lasting relationships (Carlson 2016; Tissera et al. 2021). Broadly speaking, metaperception is anchored in peoples’ self-views, where people strive to present themselves to others in specific ways (Kenny 2019), with metaperception—as a way of monitoring and interpreting the reactions of others—guiding people in their actions to enhance or preserve their social value (Baumeister and Leary 1995; Leary 2005).

Considering the key role of metaperception in people’s self-views, it is particularly important to understand whether and when people develop accurate insight into the impression they make on others. It appears that people have a fairly good sense of how they are perceived across many dimensions, including personality traits (e.g., extraversion and conscientiousness), competence attributes (e.g., intelligence and leadership), personal characteristics (e.g., attractiveness and honesty), and well-being descriptors (e.g., happiness and depression), with especially accurate metaperceptions for observable traits such as extraversion (Carlson and Kenny 2012). For instance, after previously unacquainted speakers engaged in a 5 min conversation, they provided judgments of how their personality traits (e.g., irritability, openness, and assertiveness) were seen by their partners, and these judgments generally corresponded to the partners’ actual assessments (Carlson et al. 2010).

Unlike various facets of people’s personality and character, many affective domains, including popularity and especially interpersonal liking, are prone to biased metaperception. In a sample of over 2000 observations involving individuals with both new and familiar acquaintances, Elsaadawy and Carlson (2022) reported interpersonal liking as a dimension that is particularly susceptible to negative bias, where people systematically underestimate the extent to which they are liked, especially in situations involving previously unacquainted individuals. In fact, in that sample, people’s tendency to underestimate their likability in the eyes of others was the strongest predictor of similar biases across many other social dimensions, where those who underestimated their liking also tended to show undervalued assessments of their conscientiousness, honesty, openness, and attractiveness (see also Sandstrom and Boothby 2021).

Assuming that initial interactions with previously unacquainted interlocutors are not only critical to the outcome of those interactions but also to the success of possible future relationships, it would be essential to understand whether and to what degree people are susceptible to negatively biased metaperceptions of interpersonal liking. In the study that inspired the present investigation, Boothby et al. (2018) demonstrated that previously unacquainted same-gender interlocutors who engaged in a 5 min conversation prompted by simple questions (e.g., about family and hobbies) showed a reliable difference in interpersonal liking. The speakers’ metaperception of liking (i.e., how much they believed they were liked by their partners) was significantly lower than the partners’ actual assessment of liking. In a follow-up experiment, this difference between speakers’ perceived and actual liking (referred to as the liking gap) was shown to be independent of conversation length, as it occurred after interactions lasting from 2 to 45 min. Perhaps most strikingly, a similar tendency for speakers to underestimate their perceived liking emerged for speakers engaged in conversations at a community workshop (i.e., after about 1.5 h of interaction) and persisted over several months for university students sharing accommodations on campus. In fact, the liking gap for students closed only in the last assessment episode, approximately eight months after they had moved in together, and their metaperception accuracy was unaffected by the financial incentive to receive a cash prize for accurate judgments of perceived liking.

People’s concern about the affective impressions they make on their interlocutors appears to emerge early in development and have important real-life consequences. In terms of development, a reliable liking gap was documented in a sample of 241 children (aged 4–11 years old) who worked together for 5 min to build a tower from game pieces (Wolf et al. 2021). Whereas 4-year-olds interacting with a similar-age child did not show a reliable difference in their perceived versus actual liking by their playmate, children between 5 and 11 years of age demonstrated a widening gap driven by children’s perception that their partner liked them progressively less and less. And in terms of potential real-life consequences of biased affective metaperceptions, a consistent liking gap has been reported not only for university students interacting in groups up to 12 people but also for workplace employees collaborating in teams of 3 to 5 people (Mastroianni et al. 2021). Most importantly, for all individuals, how much they believed their interlocutors liked them predicted whether they were willing to ask for help, give open and honest feedback, collaborate on another project, and (for workplace employees) how they assessed the team’s effectiveness and job satisfaction. Considering that 59% of the adult speakers in Elsaadawy and Carlson’s (2022) sample of over 2000 adult participants demonstrated negative interpersonal liking gaps, feeling less liked than they were actually perceived, many people might be disadvantaged if their negative impressions prevent them from seeking help, providing feedback, or performing their jobs effectively.

1.2. The Present Study

Considering the persistence of the liking gap and its consequences, it is important to understand whether this phenomenon extends to other language speakers and contexts. To the best of our knowledge, L2 speakers have not been targeted previously in research on interpersonal liking; so, it is unclear whether they are similarly susceptible to the liking gap and its negative consequences. Our main goal in this study was to identify the liking gap for L2-speaking university students and determine whether it predicts their willingness to engage in future social activities. Our choice of L2 English students was motivated not through practical consideration alone, in the sense that international students represent a large segment of Canada’s population (the context of our study), with over 807,750 international students (CBIE 2023) contributing an estimated CAD 22 billion to Canada’s yearly economy and creating over 170,000 jobs (El-Assal 2020). In many locations, including Canada, international students often report feeling excluded, isolated, and lacking in a sense of belonging (Netierman et al. 2022; Zhou and Zhang 2014), which suggests that their access to the social capital facilitated through interpersonal communication with peers is limited. Similarly, international students’ academic achievement and their ability to develop and maintain L2 skills required for academic performance depend on continued L2 use, especially in oral communication (Neumann et al. 2023). Thus, whether metaperception is a potential barrier to L2 communication among international students is a key question.

To understand the role of metaperception in L2 interaction involving international students, we focused on three sets of judgments. In addition to interpersonal liking, we also explored students’ metaperceptions of their speaking skill (i.e., beliefs about how their partners evaluated their L2 speech, in terms of its fluency and comprehensibility) and their interactional behavior (beliefs about how their partners assessed their conversational behaviors such as turn-taking and responsiveness). These two judgments not only encompass the linguistic and communicative challenges of students using their L2 in the academic domain but also likely reflect their concerns such as being able to communicate clearly and collaborate effectively. These two additional measures were also motivated through L1 communication research, where speakers have been shown to misjudge how harshly their interlocutors assess their conversational ability, for instance, in terms of speaking too much or being able to end a conversation (Sandstrom and Boothby 2021; Welker et al. 2023).

Finally, when exploring international students’ metaperceptions, we statistically controlled for several speaker-specific variables, including students’ personality traits (e.g., conscientiousness and agreeableness) and their demographic and linguistics profiles (e.g., age, length of residence in Canada, and their self-assessed L2 speaking ability), on the assumption that L2 speakers’ (meta)perceptions might vary as a function of these variables (Boothby et al. 2018; Cameron et al. 2011; Sandstrom and Boothby 2021). When examining potential consequences of students’ metaperceptions, before exploring the unique contribution of each metajudgment, we similarly accounted for each speaker’s liking of their interlocutor, on the assumption that the speaker’s desire to engage in a future interaction with that interlocutor would be driven, first and foremost, by the affect they feel toward them (Elsaadawy and Carlson 2022; Mastroianni et al. 2021).

Considering that people are consistently biased in their metaperceptions of interpersonal liking (Boothby et al. 2018; Carlson and Kenny 2012; Elsaadawy and Carlson 2022), we expected that L2 speakers would similarly underestimate the extent to which they are liked by their interlocutor. Given the lack of previous research on L2 speaker metaperception, we had no specific prediction for L2 speakers’ metajudgments of speaking skill and interactional behavior. On the one hand, L2 speakers might underestimate how their speaking and interactional performance is seen by interlocutors, in line with how L1 speakers feel insecure about their communication skills (Sandstrom and Boothby 2021; Welker et al. 2023). On the other hand, however, L2 international students communicating with fellow students might be less biased due to their shared identity and a common background in L2 learning and use. And in terms of the potential consequences of metaperceptions, we expected metajudgments of interpersonal liking to be associated with L2 speakers’ willingness for future interaction, in line with evidence from research in L1 communication (Mastroianni et al. 2021). Our study was guided by two research questions:

1. Do L2 students’ metaperceptions of interpersonal liking, speaking skill, and interactional behavior (perceived ratings) differ from how they are evaluated by their interlocutors (actual ratings) after engaging in an academic discussion task?2. Do L2 students’ metaperceptions of interpersonal liking, speaking skill, and interactional behavior predict their willingness to engage in future communication with their interlocutors?

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Participants

Participants included 76 L2 English speakers, all students at English-medium universities in Montréal, Canada, with an equal number of self-reported genders (38 females and 38 males) and a mean age of 24.51 years (SD = 4.99, range = 18–45). They were recruited through an announcement posted on social media student groups. Most were enrolled in master’s (35) or bachelor’s (33) degree programs, with the remaining pursuing PhD studies (7) or a graduate diploma (1). On average, the speakers’ length of residence in Canada was 5 years (SD = 8.12, range = 2 months–45 years), and they represented 23 different L1 backgrounds, with Mandarin (19), French (13), and Bengali (7) being the most common. Their English proficiency was at least the minimum required for university admission, which is a TOEFL iBT score of 75 or equivalent (corresponding to approximately a B2 CEFR level). The speakers self-reported their L2 speaking skill at a mean of 80.99 (SD = 15.54, range = 32–100) on a 100-point scale, where 100 meant “fluent”. The speakers were assigned to pairs for the interaction task based on their having a nonshared L1 background to avoid initial liking or familiarity through a common language identity. In total, there were three sets of gender dyads, with nearly equal speaker distributions: female–female (13), male–female (12), and male–male (13).

2.2. Materials

The materials consisted of an academic discussion task, a questionnaire eliciting the speakers’ impressions of their interaction, and a background and personality survey (all study materials and data are available via the OSF at https://osf.io/9pt8x, accessed on 14 June 2023). To prompt interaction between the two speakers, we gave each an academic text on a debatable topic (Appendix A). One text emphasized the importance of genetics in determining one’s personality (e.g., humor and interests), whereas the other supported the opposing view that one’s personality is shaped by the environment. Both texts were simplified summaries of research studies (Bouchard et al. 1990; Cherkas et al. 2000) and were relatively short (189–204 words) to ensure that the speakers focused more on discussing the topics than reading the summaries. At the end of each text, they were given five identical discussion questions (e.g., Which side do you agree with in the nature versus nurture debate? Are personality traits the result of nature or nurture?) which they could use to help guide their discussion on the topic.

We used a questionnaire to record the students’ impressions about their interaction (Appendix B). The first part of the questionnaire elicited each student’s impression of their partner along three dimensions, with 4 items per dimension (for a total of 12 statements). The first dimension was interpersonal liking (Boothby et al. 2018), which captured how much each student liked their partner: (a) “I liked the student”; (b) “I would like to get to know the student better”; (c) “I would like to interact with the student again”; and (d) “I could see myself becoming friends with the student”. The next two dimensions were developed specifically for this study to extend the scope of interpersonal liking to linguistic and behavioral dimensions of interaction. The dimension of speaking skill captured how much each student liked their partner’s way of speaking during the interaction: (a) “I liked how well the student spoke”; (b) “I liked how fluently the student spoke”; (c) “I liked how easy the student was to understand”; and (d) “I liked the student’s pronunciation”. The behavioral dimension targeted each student’s perception of their partner’s interactional behavior: (a) “I liked how well the student collaborated with me”; (b) “I liked how well the student responded to my ideas”; (c) “I liked how the student gave me chances to talk”; and (d) “I liked how comfortable the student made me feel”. For all statements, the speakers expressed their (dis)agreement using a 0–100 sliding scale, with endpoints labeled as “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree”.

The next part of the questionnaire elicited each student’s metaperceptions (i.e., perception of how their partner felt about them during the interaction), with 12 equivalent statements featuring the same scale length and endpoint labels. These statements targeted the same three dimensions but required each speaker to estimate their partner’s impressions. For interpersonal liking, the statements were (a) “I think the student liked me”; (b) “I think the student would like to get to know me better”; (c) “I think the student would want to interact with me again”; and (d) “I think the student could see themselves becoming friends with me”. For speaking skill, the statements were (a) “I think the student liked how well I spoke”; (b) “I think the student liked how fluently I spoke”; (c) “I think the student liked how easy I was to understand”; and (d) “I think the student liked my pronunciation”. For interactional behavior, the statements were (a) “I think the student liked how well I collaborated with them”; (b) “I think the student liked how well I responded to their ideas”; (c) “I think the student liked how I gave them chances to talk”; and (d) “I think the student liked how comfortable I made them feel”.

The last part of the questionnaire focused on potential future interactions from the perspective of each student. There were nine statements, each accompanied by a 0–100 sliding scale, with endpoints labeled “never” and “definitely”, asking the students to estimate whether they would want to engage in several academic activities with their interlocutor. The activities involved studying together (e.g., joining group discussions, doing a joint presentation, and belonging to a study group), communicating on academic topics (e.g., texting or emailing questions about course content and asking for feedback on assignments), and interacting outside coursework (e.g., spending free time outside class and giving open and honest feedback).

Finally, there was a background and personality survey that contained several questions about the students’ age, gender, language background, education, L2 English proficiency and use, and their length of residence in Canada. In terms of their personality profile, they completed the Big Five Inventory-2-S, which is a 30-item abbreviated form of the Big Five Inventory (Soto and John 2017), assessing five traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, negative emotionality, and open-mindedness) through 5-point scales, where 1 was labeled “disagree strongly” and 5 was labeled “agree strongly”.

2.3. Procedure

All data collection was conducted in accordance with an approved ethics certificate (30001284) from the researchers’ university. Each session was carried out with one pair of students in a quiet multiroom research space on campus, with one of two researchers assigned to be responsible for each student. At the beginning of each interactive session, the researchers ensured (to the best of their ability) that two students did not encounter each other before the academic discussion task began by inviting them to separate rooms upon arrival to review and sign the consent form (2 min). Both students were then brought to another room where they were seated at a table across from each other. They were introduced to the discussion topic and were instructed to read their academic text and then engage in a discussion using the guiding questions as prompts. The researchers then left the room, allowing the two students to complete the task unobserved. After finishing their reading (3–5 min), the students engaged in a 10 min free-flowing conversation, sharing their understanding of the text and their own opinions. The content and scope of each conversation was not controlled, in the sense that each pair could decide on whether and how to begin their conversation, how much personal information to provide (including whether and how to introduce themselves), and what to say in response to each question prompt. The conversations were audio-recorded through a microphone placed on the table (outside the students’ direct view of each other so as not to distract them), and all students were made aware of the recording through the consent form and instructions provided before the task. After the 10 min mark for each conversation was reached, the researchers re-entered the room, and the students returned to their original individual rooms to provide their perceptions of the interaction and to complete the background and personality survey. All rated items were presented on personal laptops through the LimeSurvey platform (https://www.limesurvey.org, accessed on 17 October 2022). At the end of the session, the students individually completed several other brief scales (e.g., focusing on their experience with discrimination, acculturative stress, and social attitudes), but these data fall outside the scope of this report and are not analyzed further. Each student remained alone while completing the online questionnaires in their designated room without any distractions until leaving the research space (20–30 min).

3. Data Analysis

All ratings from LimeSurvey were imported into spreadsheets. In terms of the students’ assessments of each other, following Boothby et al. (2018), there were two sets of ratings: the students’ actual ratings as assessed by their partners and their perceived ratings (i.e., metaperceptions, or how they believed their partner assessed them). Because the responses to the four statements per rated dimension (interpersonal liking, speaking skill, and interactional behavior) demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha), each student’s evaluations were averaged across the four relevant statements to derive a single actual and a single perceived score per dimension (i.e., by averaging across items a through d, as described above): actual interpersonal liking (0.91), perceived interpersonal liking (0.94), actual speaking skill (0.97), perceived speaking skill (0.92), actual interactional behavior (0.93), and perceived interactional behavior (0.88). In terms of the willingness to engage in future interaction, there was high consistency across the nine items (0.94), so a single mean composite score was computed per student. The scores for the five personality traits were derived per student by averaging across the six items targeting each trait using the test guidelines (Soto and John 2017): extraversion (0.69), agreeableness (0.71), conscientiousness (0.77), negative emotion (0.79), and open-mindedness (0.59). These internal consistency values were comparable to those reported previously in scale validation research (0.73–0.84) using large Internet-based and university-level participant samples (Soto and John 2017), but the consistency was lower for open-mindedness. Because no interaction lasted under 10 min and the researchers stopped each conversation at the 10 min mark, conversations were identical in duration across all dyads, meaning that interaction length did not need to be controlled.

To address the first research question, which asked whether the students differed in their actual versus perceived assessments of the interaction, we computed linear mixed-effects models in R (version 4.2.2, R Core Team 2023) using the lme4 package (version 1.1-31, Bates et al. 2015). In each model, interpersonal liking, speaking skill, and interactional behavior were the outcome variables, whereas rating type (actual vs. perceived), gender dyad (female–female vs. female–male vs. male–male), and their interaction served as fixed-effects predictors, with random intercepts for speakers (76) nested within pairs (38). In cases where the inclusion of gender dyad led to better-fitting models, we also modeled student gender (female vs. male), used as a fixed-effect predictor, given that mixed-gender dyads (predictably) included students of both genders. Finally, all models also included several fixed effects as student-level control covariates (five personality traits, plus speakers’ age, length of residence in Canada, and their self-assessed L2 speaking ability) on the assumption that the students’ ratings of each other might vary as function of their age, L2 experience and proficiency, and specific personality traits (e.g., agreeableness and open-mindedness).

To address the second research question, we similarly computed linear mixed-effects models, where the composite measure of willingness to engage in future interaction served as the outcome variable, and the students’ perceived ratings of interpersonal liking, speaking skill, and interactional behavior were used as separate fixed-effects predictors. In each model, we also entered the students’ actual ratings of their partners as a control covariate, on the assumption that the composite measure of future interactions would be primarily associated with the students’ actual perceptions. Because these models included only a single datapoint for each student per variable, we did not model students as a random effect; however, we accounted for the nested structure of our dataset by including random intercepts for pairs (38).

We used the maximum likelihood method to fit the models, with fit assessed through pairwise likelihood ratio tests comparing simpler to more complex models (Barr et al. 2013). Random slope models were examined separately for students and pairs, but these models did not improve fit; so, only the random intercepts of students and pairs were entered in the final models (where relevant). For fixed-effects predictors, we forward-tested the predictors in an exploratory fashion and explored the interactions only when the inclusion of a predictor improved model fit. To estimate the significance of each predictor, we obtained p-values through the MuMIn package in R (version 1.47.1, Bartoń 2020) and examined 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to check the statistical significance of each parameter (interval does not cross zero). Correlation strength was interpreted based on field-specific guidelines (Plonsky and Oswald 2014) for small (0.25), medium (0.40), and large (0.60) effects.

4. Results

4.1. Students’ Actual and Perceived Assessments

To address the first research question, we examined the students’ actual and perceived ratings. As summarized in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, the students’ actual ratings (as assessed by their partner) were generally higher (63–90 on a 100-point scale) than their perceptions of the partner’s assessment (60–76), although the magnitude of these gaps, at least in some instances, seemed to vary by the gender composition of the pair. Across the entire speaker sample, the actual and perceived ratings showed weak associations for interpersonal liking (r = 0.24, p = 0.036), speaking skill (r = 0.29, p = 0.011), and interactional behavior (r = 0.37, p < 0.001), revealing only a weak match between the students’ metaperceptions and their partners’ actual assessments. In terms of the relationships between the three rated dimensions, the actual ratings showed strong relationships (all above 0.60): interpersonal liking and speaking skill (r = 0.63, p < 0.001), interpersonal liking and interactional behavior (r = 0.80, p < 0.001), and speaking skill and interactional behavior (r = 0.69, p < 0.001). There were weaker relationships between the perceived ratings; however, they also approached or surpassed the 0.60 value: interpersonal liking and speaking skill (r = 0.54, p < 0.001), interpersonal liking and interactional behavior (r = 0.67, p < 0.001), and speaking skill and interactional behavior (r = 0.60, p < 0.001). Even though the three rated measures shared 29–64% of the variance, they nevertheless appeared to capture sufficiently distinct evaluative dimensions.

4.1.1. Interpersonal Liking

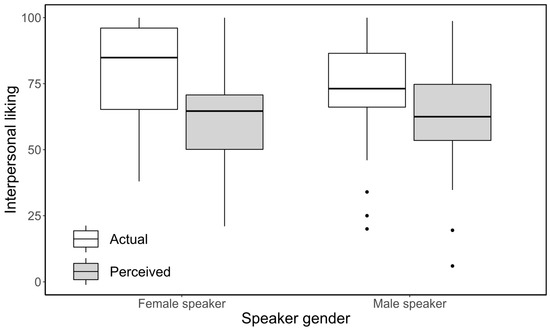

The initial model for interpersonal liking revealed a significant effect of rating type (perceived vs. actual), Estimate = −14.19, SE = 2.25, t = −6.30, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−18.61, −9.77], where the students tended to underestimate how much their partner liked them by approximately 14 points on a 100-point scale (see Table 1). Adding a fixed effect of gender pairing (female–female vs. female–male vs. male–male), χ2(2) = 1.65, p = 0.437, or the interaction term involving gender pairing, χ2(4) = 2.67, p = 0.614, did not improve model fit, implying that the effect of rating type was similar across the three gender pairings. Neither the inclusion of speaker gender (female vs. male speakers), χ2(1) = 0.13, p = 0.720, nor its interaction, χ2(2) = 3.17, p = 0.205, improved fit, suggesting that the effect of rating type was comparable for the female and male students. Finally, the inclusion of control covariates did not improve model fit either, χ2(8) = 7.70, p = 0.463; however, agreeableness emerged as a significant predictor in the final model, where higher scores on the agreeableness dimension predicted interpersonal liking positively, Estimate = 5.41, SE = 2.37, t = 2.28, p = 0.024, 95% CI [0.72, 10.10]. To summarize, all students (regardless of their own or their partner’s gender or the gender composition of a dyad) tended to underestimate how much their partner liked them (see Figure 1). The final model (summarized in Appendix C) accounted for 18% of variance through fixed effects (marginal R2 = 0.18) and explained a total of 48% variance through both fixed and random effects (conditional R2 = 0.48).

Figure 1.

Boxplots for ratings of actual and perceived interpersonal liking of conversation partners by gender: The effect of rating type (actual vs. perceived) is significant for both genders. Actual ratings describe assessments of each speaker by their partner; perceived ratings refer to each speaker’s perceptions of the partner’s assessment.

Table 1.

Means (Standard Deviations) for Actual and Perceived Interpersonal Liking Ratings.

Table 1.

Means (Standard Deviations) for Actual and Perceived Interpersonal Liking Ratings.

| Speaker Pair | Perceived | Actual | Correlation | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female–female (n = 26) | 63.73 (19.39) | 80.26 (19.47) | 0.39 * | −16.53 (21.38) |

| Male–male (n = 26) | 59.89 (20.20) | 71.09 (20.79) | 0.16 | −11.19 (26.52) |

| Female–male (n = 24) | 63.15 (14.35) | 78.04 (13.51) | 0.02 | −14.90 (19.48) |

Note. * p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

4.1.2. Speaking Skill

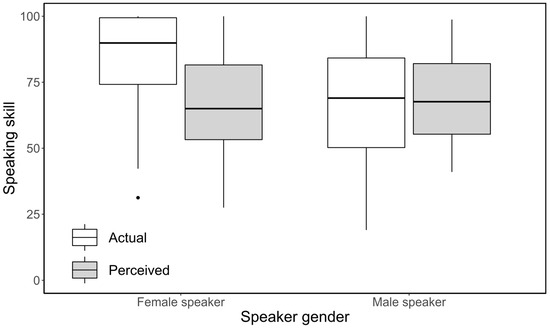

The initial model for speaking skill similarly yielded a significant effect of rating type, Estimate = −7.87, SE = 2.83, t = −2.78, p = 0.007, 95% CI [−13.45, −2.28], where the students tended to underestimate their partner’s rating. Adding a fixed effect of gender dyad did not improve model fit, χ2(2) = 4.53, p = 0.104, but including the interaction term involving gender pairing did, χ2(4) = 16.65, p = 0.002. This result was driven by a significant interaction involving student gender, χ2(2) = 14.19, p < 0.001, rather than gender pairing (see Table 2), where the effect of rating type was significant for the women, Estimate = −17.33, SE = 3.64, t = −4.76, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−24.55, −10.11], but not for the men, Estimate = 1.60, SE = 3.80, t = 0.42, p = 0.676, 95% CI [−5.93, 9.13]. Thus, only the women (i.e., regardless of whether they interacted with female or male partners) tended to underestimate how their partner assessed their speaking skills, by an average of 17 points (see Figure 2). The inclusion of control covariates further improved model fit, χ2(8) = 30.37, p =< 0.001, but did not change the pattern of findings. In addition to the effect of rating type, the students’ self-assessed L2 speaking ability predicted the ratings, where higher self-assessed L2 speaking ability was positively associated with the speaking skill, Estimate = 0.52, SE = 0.11, t = 4.60, p =< 0.001, 95% CI [0.29, 0.74]. No other control covariate predicted speaking skill. The final model (summarized in Appendix C) accounted for 29% of variance through fixed effects (marginal R2 = 0.29) and explained a total of 46% variance through both fixed and random effects (conditional R2 = 0.46).

Figure 2.

Boxplots for ratings of actual and perceived speaking skill of conversation partners by gender: The effect of rating type (actual vs. perceived) is significant only for female students. Actual ratings describe assessments of each speaker by their partner; perceived ratings refer to each speaker’s perceptions of the partner’s assessment.

Table 2.

Means (Standard Deviations) for Actual and Perceived Speaking Skill Ratings.

Table 2.

Means (Standard Deviations) for Actual and Perceived Speaking Skill Ratings.

| Speaker Pair | Perceived | Actual | Correlation | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female–female (n = 26) | 65.22 (20.41) | 84.59 (18.91) | 0.31 | −19.37 (23.08) |

| Male–male (n = 26) | 66.23 (15.97) | 62.85 (24.47) | 0.47 * | +3.38 (22.11) |

| Female–male (n = 24) | 68.31 (14.96) | 75.91 (21.93) | 0.19 | −7.59 (24.15) |

| Female speaker (n = 12) | 65.15 (16.47) | 78.06 (24.33) | 0.52 | −12.92 (21.20) |

| Male speaker (n = 12) | 71.48 (13.20) | 73.75 (20.10) | −0.25 | −2.27 (26.62) |

Note. The values for mixed-gender dyads are broken down separately for the female and male speakers in the last two rows of the table. * p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

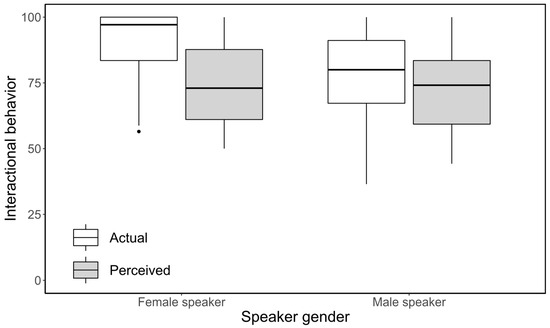

4.1.3. Interactional Behavior

The initial model for interactional behavior also yielded a significant effect of rating type, Estimate = −10.22, SE = 1.98, t = −5.15, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−14.12, −6.32], where the students again tended to underestimate their partner’s rating. Adding a fixed effect of gender pairing, χ2(2) = 6.46, p = 0.039, and the interaction term involving gender pairing, χ2(4) = 11.69, p = 0.020, improved model fit. As with the ratings of speaking skill, this result was driven by a significant interaction involving student gender, χ2(2) = 10.46, p = 0.005, rather than gender pairing (see Table 3), where the effect of rating type was significant for the women, Estimate = −15.98, SE = 2.68, t = −5.97, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−21.27, −10.69], but not for the men, Estimate = −4.46, SE = 2.72, t = −1.64, p = 0.110, 95% CI [−9.86, 0.94]. Thus, only the women (i.e., regardless of whether they interacted with female or male partners) seemed to underestimate how their partner assessed their interaction behavior (see Figure 3). The inclusion of control covariates did not improve model fit, χ2(8) = 6.36, p = 0.607; however, as with interpersonal liking, the control covariate agreeableness emerged as significant in the final model, where higher scores on the agreeableness dimension predicted interactional behavior positively, Estimate = 4.20, SE = 2.10, t = 2.00, p = 0.048, 95% CI [0.04, 8.36]. The final model (shown in Appendix C) accounted for 18% of variance through fixed effects (marginal R2 = 0.18) and explained a total of 51% variance through both fixed and random effects (conditional R2 = 0.51).

Figure 3.

Boxplots for ratings of actual and perceived interactional behavior of conversation partners by gender: The effect of rating type (actual vs. perceived) is significant only for female students. Actual ratings describe assessments of each speaker by their partner; perceived ratings refer to each speaker’s perceptions of the partner’s assessment.

Table 3.

Means (Standard Deviations) for Actual and Perceived Interpersonal Behavior Ratings.

Table 3.

Means (Standard Deviations) for Actual and Perceived Interpersonal Behavior Ratings.

| Speaker Pair | Perceived | Actual | Correlation | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female–female (n = 26) | 74.81 (16.32) | 90.07 (13.13) | 0.19 | −15.26 (18.91) |

| Male–male (n = 26) | 69.79 (15.97) | 74.32 (20.14) | 0.50 ** | −4.53 (18.44) |

| Female–male (n = 24) | 76.46 (13.35) | 87.39 (12.44) | 0.20 | −10.93 (16.37) |

| Female speaker (n = 12) | 73.10 (13.50) | 90.65 (13.10) | 0.17 | −17.54 (17.09) |

| Male speaker (n = 12) | 79.81 (12.88) | 84.13 (11.34) | 0.42 | −4.31 (13.15) |

Note. The values for mixed-gender dyads are broken down separately for the female and male speakers in the last two rows of the table. ** p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

4.2. Willingness to Engage in Future Interaction

To address the second research question, we examined whether the students’ meta-perceptions (i.e., how they thought their partner evaluated them) predicted possible future interactions as assessed through a composite measure across nine items targeting the speakers’ willingness to engage in communication with their partners. The students generally expressed fairly strong willingness to interact with each other in the future, with a mean composite score of 72.04 on a 100-point scale (SD = 20.68, range = 0–100). However, as shown through substantial standard deviation and range values, individual students expressed a range of opinions. To control for the possibility that the composite measure would be largely associated with the students’ actual affect expressed toward their partners (in terms of interpersonal liking, speaking skill, and interactional behavior), we included these ratings as control covariates in each model. We also tested these relationships separately for the female and male students, because the analyses reported above indicated that these relationships may differ by gender.

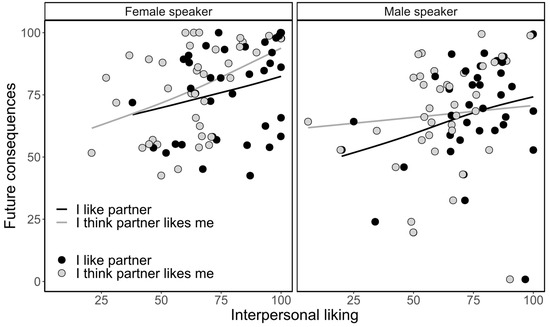

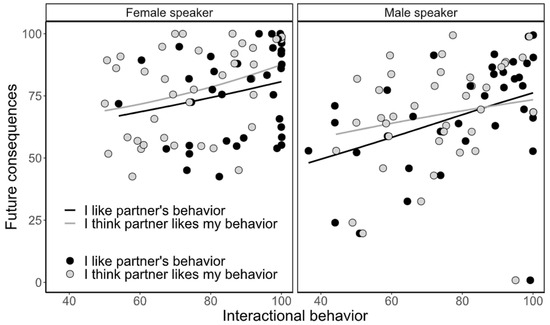

For the male students, after controlling for their actual perceptions of their partners, the composite measure of possible future interactions was not predicted by any perceived ratings: interpersonal liking, Estimate = 0.21, SE = 0.20, t(35) = 1.06, p = 0.296, 95% CI [−0.19, 0.61], speaking skill, Estimate = 0.17, SE = 0.26, t(35) = 0.65, p = 0.518, 95% CI [−0.36, 0.70], or interactional behavior, Estimate = 0.31, SE = 0.27, t(35) = 1.14, p = 0.261, 95% CI [−0.24, 0.86]. In contrast, for the female students, after controlling for their actual perceptions of their partners, the composite measure of possible future interactions was predicted by their perceived ratings of interpersonal liking, Estimate = 0.37, SE = 0.15, t(35) = 2.40, p = 0.022, 95% CI [0.06, 0.68], and interactional behavior, Estimate = 0.34, SE = 0.16, t(35) = 2.16, p = 0.038, 95% CI [0.02, 0.66], but not speaking skill, Estimate = 0.14, SE = 0.16, t(35) = 0.87, p = 0.389, 95% CI [−0.18, 0.46] (for full models, see Appendix C). In essence, how much the female students perceived that their partners liked them and believed that their partners appreciated their interactional behavior (regardless of partner gender) significantly predicted their willingness to interact with those partners, where lower perceived ratings were associated with less willingness to communicate. As illustrated in Figure 4 for interpersonal liking (see Appendix D for a similar scatterplot focusing on interactional behavior), only the female students’ future interactive behaviors were linked to how strongly they believed they were liked (gray trendline capturing metaperceptions), after controlling for their actual liking of their partners (black trendline).

Figure 4.

Scatterplot of speakers’ assessments of future consequences of interaction as a function of their actual perceptions of their partners (I like partner) and their perceived liking by their partners (I think partner likes me, capturing metaperception), separately for female and male students, with the trendlines (using the gam smoothing function) illustrating the best fit to the data.

5. Discussion

Our goal in this study was to extend prior L1 communication research to interactions involving L2 speakers, exploring whether previously reported metaperception gaps (i.e., differences between how speakers believe they are perceived versus how they are actually evaluated) occur in L2 conversations and whether L2 speakers’ metajudgments have consequences for their willingness to engage in future interaction. Our findings showed a reliable interpersonal liking gap for previously unacquainted L2 students; however, only the female students in our sample (regardless of their partner’s gender) demonstrated a similar gap in metaperception of their speaking skill and interaction behavior. Only the female students (irrespective of their partner’s gender) showed an association between their metaperceptions and their willingness to engage in future interaction. How much the female students believed that their partners liked them as a person and appreciated their interactional behavior predicted their willingness to participate in various future social communication activities with those partners.

5.1. Biased Metaperceptions

Considering that biased metaperception of interpersonal liking has been document-ed for L1 speakers across a range of individuals (e.g., children and adults), contexts (e.g., platonic conversations, dating scenarios, and workplace communication), and relationship types, including lasting friendships and new acquaintanceships (Boothby et al. 2018; Elsaadawy and Carlson 2022; Mastroianni et al. 2021; Wolf et al. 2021), it is not altogether surprising that L2-speaking international students similarly showed a liking gap. Even though the instruments used in prior research included different scale lengths, the magnitude of the liking gap reported here (M = 14 on a 100-point scale) is comparable to that reported in Boothby et al.’s (2018) initial investigation (M = 0.65 on a 7-point scale, or a 9.29% difference). In fact, in our dataset, a numerically larger proportion of participants (57 of the 76 L2 speakers, or 75%) showed a negative liking bias, reporting underestimated metajudgments, compared with 59% of L1 speakers demonstrating negative biases in Elsaadawy and Carlson’s (2022) dataset, and this proportion was nearly identical between the female (29/38, or 76%) and the male (28/38, or 74%) L2 students. Thus, as with L1 interlocutors, L2 students interacting with each other demonstrate a reliable liking gap, which appears to be a robust, generalizable phenomenon.

Our findings additionally extend prior work by showing that L2 speakers demonstrate similar gaps in metajudgments of their speaking skill (i.e., in terms of pronunciation quality, fluency, and comprehensibility) and their interactional behavior (i.e., in terms of turn-taking, responsiveness, and collaborativeness). At a broad level, these results are compatible with a documented tendency among L1 speakers to underestimate how their interlocutors perceive their conversational ability, for example, in terms of having sufficient content to contribute or knowing how to start or end a conversation (Sandstrom and Boothby 2021). Similarly, when asked to describe the best and the worst moments of a recent conversation, L1 speakers appear to associate various aspects of their own performance with the low points in the conversation, but they tend to attribute its best moments to their partners, while also estimating that their partners’ enjoyment of the conversation is significantly lower than their own (Welker et al. 2023). Thus, speakers’ uncertainty about their interaction success, as seen through the eyes of their interlocutors, coupled with an excessive worry about their own conversational shortcomings, may lead speakers to underestimate the value of their speaking skill and interactional behavior for their conversation partner.

However, metaperception gaps for speaking skill and interactional behavior in our study were primarily driven by the female students, irrespective of their speaking partner; so, the generalizability of these findings is limited. A gender difference in metaperception was unexpected in light of the robust findings reported previously (Boothby et al. 2018; Wolf et al. 2021); nevertheless, gender effects have been attested, for instance, where males and females differ in evaluation of partners’ conversational ability (Sandstrom and Boothby 2021) and likability (Tissera et al. 2021). As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, the negative bias demonstrated here by the female students in their metajudgments of speaking skill and interpersonal behavior was not due to them being particularly harsh metaperceivers. Rather, compared with the male students, the female students elicited more generous evaluations from their partners (both men and women) in speaking skill (Mfemale = 82.53 vs. Mmale = 66.29) and interactional behavior (Mfemale = 90.25 vs. Mmale = 77.41), with a reliable difference, t(38) > 3.20, p < 0.002, d > 0.73. From this vantage point, the obtained gender difference in the metaperceptions of speaking and interactional performance likely reflected a commonly reported proficiency advantage for female over male L2 speakers (Denies et al. 2022; van der Slik et al. 2015). Thus, the female L2 students were better speakers and communicators, which was recognized by their interlocutors through more generous evaluations of their actual performance (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

5.2. Consequences of Metaperception Bias

Considering that the female students in this sample were better speakers and communicators, at least as assessed by their conversation partners, it is particularly striking that only their metaperception predicted interest in future interactions. The female students who were feeling especially uncertain as to how likeable they were seen by their interlocutors and how much their interlocutors appreciated their interactional behavior expressed less willingness to communicate with those interlocutors in the future. This effect, which was independent of the students’ actual liking of their partners, was similar to the previously reported negative impact of metaperception on various real-life outcomes, such as willingness to ask for help and job effectiveness and satisfaction (Mastroianni et al. 2021). At a broader level, this effect also parallels the phenomenon that women are especially prone to underestimating their performance in self-assessment across a variety of skills (Sikora and Pokropek 2012), which might explain why women are reluctant to get into science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers (Verdugo-Castro et al. 2022). Just as the women who underestimate their scientific reasoning skills have been shown to decline a future invitation to participate in a science competition (Ehrlinger and Dunning 2003), the L2-speaking female students here might have felt insecure about the impressions they made on their interlocutor; so, they were reluctant to pursue a future interaction. The male and female students in our study came from comparable disciplines (across both science and the humanities) and did not differ in age (Mfemale = 23.74 vs. Mmale = 25.29), length of prior English study (Mfemale = 13.00 vs. Mmale = 14.33 years), or year of university studies (Mfemale = 2.19 vs. Mmale = 1.97), with women in fact reporting longer stays in Canada than men (Mfemale = 6.79 vs. Mmale = 3.23 years); so, it is unclear why women were especially reliant on metaperception in their willingness to pursue a future interaction with their interlocutor. If this finding is confirmed in follow-up work, it would be critical to show that a negative (meta)perception–behavior cycle can be broken through awareness-raising or intervention tasks (Sandstrom et al. 2022) to avoid a self-fulfilling prophesy where a speaker’s reluctance to engage in a conversation is interpreted as a sign of communicative incompetence (Jussim and Harber 2005).

5.3. Role of Individual Differences

To control for individual differences in the L2 students’ personality and language backgrounds, we included eight variables as control covariates (five personality traits, plus speakers’ age, length of residence in Canada, and their self-assessed L2 speaking ability). We found little contribution of these variables to their ratings, apart from a positive effect of agreeableness on the ratings of liking and interactional behavior and the positive effect of self-rated L2 speaking ability on ratings of speaking skill. Agreeableness, which encompasses such attributes as compassion, respectfulness, and trust, taps into people’s motivations for positive interpersonal relationships and their desire to avoid conflict (Jensen-Campbell and Graziano 2001); so, it is intuitive that the students with higher scores on this trait would provide greater ratings of liking and interactional behavior compared with those with lower agreeableness scores. With respect to the ratings of speaking skill, again, a positive contribution of self-rated speaking ability to pronunciation, fluency, and comprehensibility is similarly expected, in the sense that L2 students with a stronger own speaking skill tend to provide higher assessments of speaking (Trofimovich et al. 2016). We found little evidence for the role of other personality traits, including extraversion, conscientiousness, open-mindedness, and negative emotionality, in metaperception (Boothby et al. 2018; Cameron et al. 2011; Sandstrom and Boothby 2021). However, unlike these other studies, we included these variables as control covariates only, because direct and indirect influences of personality variables on metaperception fall outside our immediate research scope. We therefore leave it to follow-up work to investigate these issues in detail.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Our findings must be interpreted in light of several limitations. In terms of participant characteristics, it would be important to replicate and extend our results with other L2 speakers and other target languages, including language learners of different proficiency levels, recruited from both instructional and noninstructional settings. For instance, L2 speakers of lower proficiency might be particularly concerned about the impressions they make on others, in the sense that metajudgments of interpersonal liking might suffer when L2 speakers struggle to express their message clearly. It might also be interesting to systematically examine metaperceptions for speakers from different cultures, assuming that cross-cultural differences might moderate the degree to which interlocutors form accurate impressions of how they impact each other in their affect, language, and communication (Malloy et al. 1997). Considering that metaperception varies as a function of relationship type, insofar as metaperceptions are more accurate among individuals in close-knit relationships such as family and friends than for new acquaintances (Carlson 2016; Malloy et al. 1997), it might likewise be informative to explore metaperception for L2 interlocutors who know each other more versus less and who differ in status (Snodgrass et al. 1998), for instance, as L1 versus L2 speakers or interviewers versus interviewees. Last but not least, in terms of potential other speaker-level variables, in future work, it would be important to determine how other social constructs such as race and ethnicity influence interpersonal liking and other metaperceptions. Whereas such influences may have been obscured by our diverse sample of L2 speakers from different linguistic backgrounds, any perceived and actual biases of individual speakers may clearly impact their perception and behavior.

With respect to task effects, our findings might be specific to the particular requirements of the two-way information-gap task employed here. For instance, academic discussion, as a cognitively challenging task, might influence the extent to which interlocutors are susceptible to metaperception bias through the match or mismatch between a speaker’s academic skillset and the task demands. L2 speakers might also be more or less concerned about the impressions they make on their interlocutor in tasks that vary in degree of affective versus cognitive involvement or those that differ in extent of internally or externally imposed pressures, such as platonic conversations versus graded groupwork. Additionally, researchers might explore L2 speakers’ metaperceptions from two complementary perspectives (Donnelly et al. 2022). This study was conducted within the mean-level approach, which is concerned with documenting directional differences in L2 speakers’ metaperception (i.e., biases to under- or overestimate one’s impression on the interlocutor). However, as shown in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, the relative standing of speakers in terms of how well their metajudgment matched their partner’s evaluation (correlation strength) was generally independent from a whole-sample bias (magnitude and directionality of gaps). This implies that the importance of metaperception and its real-life consequences for L2 speakers depend on whether researchers focus on bias, just as we did here (e.g., investigating whether L2-speaking students know how positively or negatively they are seen by interlocutors), or whether researchers target accuracy (e.g., examining whether L2-speaking students are aware of their relative standing among their instructors, fellow classmates, or future employers).

Last but not least, our dataset has little to contribute to explaining the origins of the documented metaperception bias, especially for female L2 students, who appeared particularly disadvantaged in terms of their willingness to engage in potential future communication with their conversation partners. There is a rapidly growing body of evidence suggesting that conversations are cognitively complex; so, speakers might overlook feedback from their interlocutors (Epley et al. 2004), exaggerate the salience of their conversation behaviors (e.g., nervousness, talkativeness) to their interlocutors (Savitsky and Gilovich 2003), disproportionately question their conversational ability and focus on the negative aspects of a conversation (Boothby et al. 2018), blame themselves for how an interaction unfolds (Welker et al. 2023), and form metaperceptions based on the information that is unavailable to their interlocutors, such as particularly embarrassing, negative experiences with specific past conversations (Chambers et al. 2008). Therefore, in future research, it would be essential to clarify whether and to what degree all these sources of bias apply to L2 speakers. Even more importantly, it would be critical to explain why, although all L2 speakers in our sample experienced an interpersonal liking gap, such as feeling less secure about their likeability than they should, only the female speakers seemed to factor this bias into their decision to engage in a future interaction.

7. Conclusions

In this study, we extended prior research in L1 communication to L2 speakers, investigating whether metaperception might be a barrier to L2 interaction among international students. We showed that as a whole group, our L2 international students studying at an English-medium university experienced a liking gap, where they underestimated the impressions they made on their conversation partner, and that some students showed a comparable gap in the metaperception of their speaking skill and interactional behavior. We also demonstrated that metaperceptions were particularly consequential for the female students in our sample, where how much they believed their interaction partner liked them as a person and appreciated their interactional behavior predicted the extent of their willingness to interact with that partner in the future. Clearly, ours is an initial attempt to understand the metadynamics of L2 interaction for university students communicating in a shared L2, and we hope it will motivate applied linguists to expand this work as they clarify the role of metaperception in L2 interaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T. and K.M.; methodology, all authors; formal analysis, P.T.; investigation, R.L., T.-N.N.L., C.Z. and A.B.; data curation, R.L., A.B. and P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, P.T. and K.M.; visualization, P.T.; supervision, P.T., K.M. and R.L.; project administration, P.T., K.M. and R.L.; funding acquisition, P.T. and K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to P.T. and K.M., grant numbers 435-2019-0754 and 430-2020-1134.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by Concordia University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (Certificate 30001284, approved 19 August 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials for this study are publicly available via the OSF (https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/9pt8x).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all members of the Applied Linguistics Lab (https://www.cal-lab.ca, accessed on 14 June 2023), and especially Masatoshi Sato, Yoo-Lae Kim, and Chen Liu, for their feedback on earlier drafts of this work. Our thanks also go to Yoo-Lae Kim and Chen Liu for their help with data collection and data coding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Nature vs. Nurture Debate Interaction Task

- Text 1. Happy Families: A Twin Study of Humor

How do you respond to cartoons? Would you respond the same way as your family members or other students in your degree program? Cherkas et al. (2000) conducted a twin study to test whether an individual’s appreciation of humor is influenced by genetic factors or by one’s shared family environment or unique environment. Their participants included 127 pairs of female twins (71 identical twins who share 100% of their genes, and 56 nonidentical twins who share 50% of their genes), ages 20–75. Five cartoons were used in the questionnaire, in which both twins were asked to rate them on a scale from 0 (“This cartoon was a waste of paper”) to 10 (“This cartoon was one of the funniest I have ever seen”). The researchers hypothesized that humor is influenced by genetics, and therefore, they expected that the identical twins would be more similar in their appreciation for humor than the nonidentical twins, since they share more genes. However, they found that all twins (whether identical or not) had considerably similar responses to their twin. Therefore, the study’s results did not support the idea of genetic contribution to humor and instead suggested that humor appreciation is largely affected by an individual’s shared environment.

- Text 2. Sources of Human Psychological Differences: The Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart

Starting in 1979, Bouchard et al. (1990) conducted one of the most famous studies on the influence of genetics on human traits by studying more than 100 sets of identical twins who were separated at birth. This allowed the researchers to investigate the traits the twins shared despite growing up in different environments. The researchers found many striking similarities of mannerisms (e.g., both twins read magazines backwards), personal choices (e.g., both twins chose the same name for their child), and expressive social behavior (e.g., shyness). As these aspects are related to one’s personality, it is possible that there are strong influences of genetics on personality. One incredible example was two twins who were separated at 4 weeks old and were reunited at age 39, but they learned that they both married a woman named Betty and divorced a woman named Linda, both named their son James and their dog Toy, both did carpentry, mechanical drawing, and had law-enforcement training, and both vacation on the same beach in Florida. Therefore, the findings of their study support the hypothesis that genetic similarity contributes to individuals’ similarities in personality.

One of the most famous debates in the history of psychology is the nature vs. nurture debate, where nature refers to the influence genetics has on one’s appearance and personality characteristics and nurture refers to the role our experiences and environment play in who we are.

Discuss with your partner:

- Summarize for your partner the study you read about and explain which side of the nature vs. nurture debate it supports.

- Why have scientists been debating this question for centuries? In other words, why is it important to investigate whether nature or nurture is more dominant in determining a person’s personality?

- Which side do you agree with in the nature vs. nurture debate? Are personality traits the result of nature or nurture?

- Can you think of a human characteristic for which genetic differences would play almost no role? Defend your choice.

- To what extent are each of the following items influenced by nature or nurture? Why?

- Accent or what language you speak

- Intelligence

- Temper (aggressive behavior)

- Body size

- Language acquisition

- Artistic or musical ability

- Alcoholism

- Political opinions

Appendix B. Interpersonal Ratings

- Part 1. Answer some questions about how you felt about the student.

- I liked the student.

- I would like to get to know the student better.

- I would like to interact with the student again.

- I could see myself becoming friends with the student.

- I liked how well the student spoke.

- I liked how fluently the student spoke.

- I liked how easy the student was to understand.

- I liked the student’s pronunciation.

- I liked how well the student collaborated with me.

- I liked how well the student responded to my ideas.

- I liked how the student gave me chances to talk.

- I liked how comfortable the student made me feel.

- Part 2. Now answer some questions about how you think the student felt about you.

- I think the student liked me.

- I think the student would like to get to know me better.

- I think the student would want to interact with me again.

- I think the student could see themselves becoming friends with me.

- I think the student liked how well I spoke.

- I think the student liked how fluently I spoke.

- I think the student liked how easy I was to understand.

- I think the student liked my pronunciation.

- I think the student liked how well I collaborated with them.

- I think the student liked how well I responded to their ideas.

- I think the student liked how I gave them chances to talk.

- I think the student liked how comfortable I made them feel.

- Part 3. If you had class with the student you just met during the discussion activity, would you want to…

- Join group discussions with them in class?

- Do a presentation with them?

- Belong to a study group with them?

- Ask them to explain a concept or term?

- Text or email them a question about course content?

- Ask them for feedback on your paper?

- Ask them to share their notes with you?

- Spend free time with them outside class?

- Give them open and honest feedback?

Appendix C. Summary of Final Mixed-Effects Models

Table A1.

Interpersonal Liking.

Table A1.

Interpersonal Liking.

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 62.73 | 22.90 | [19.59, 106.12] | 2.74 | 0.008 |

| Rating type | −14.19 | 1.45 | [−17.04, −11.33] | −9.80 | <0.001 |

| Speaker-level covariates | |||||

| Extraversion | 1.01 | 2.63 | [−3.94, 5.98] | 0.38 | 0.702 |

| Negative emotion | −1.84 | 2.30 | [−6.13, 2.48] | −0.80 | 0.427 |

| Open-mindedness | 4.82 | 2.85 | [−0.51, 10.15] | 1.69 | 0.096 |

| Conscientiousness | −2.78 | 2.02 | [−6.77, 1.21] | −1.38 | 0.170 |

| Agreeableness | 5.41 | 2.37 | [0.72, 10.10] | 2.28 | 0.024 |

| Age | −0.04 | 0.41 | [−0.81, 0.73] | −0.10 | 0.924 |

| Residence in Canada | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] | −0.10 | 0.918 |

| English-speaking self-rating | −0.17 | 0.13 | [−0.41, 0.07] | −1.31 | 0.194 |

| Random effects | Variance | SD | Criterion | Estimate | |

| Speaker (intercept) | 157.22 | 12.54 | Log-likelihood | −613.02 | |

| Pair (intercept) | 61.25 | 7.83 | AIC | 1252.00 | |

| BIC | 1291.30 | ||||

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion, BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

Table A2.

Speaking Skill.

Table A2.

Speaking Skill.

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 68.81 | 22.89 | [21.11, 114.01] | 3.01 | 0.004 |

| Rating type | −19.37 | 4.77 | [−28.64, −10.09] | −4.06 | <0.001 |

| Female speakers: perceived vs. actual | −17.33 | 3.64 | [−24.55, −10.11] | −4.76 | <0.001 |

| Male speakers: perceived vs. actual | 1.60 | 3.80 | [−5.94, 9.13] | 0.42 | 0.676 |

| Speaker-level covariates | |||||

| Extraversion | −3.48 | 2.53 | [−8.14, 1.22] | −1.38 | 0.175 |

| Negative emotion | 0.13 | 2.21 | [−4.03, 4.19] | 0.06 | 0.954 |

| Open-mindedness | 2.51 | 2.77 | [−2.58, 7.62] | 0.91 | 0.368 |

| Conscientiousness | −1.54 | 2.45 | [−6.05, 3.01] | −0.63 | 0.533 |

| Agreeableness | 3.70 | 2.91 | [−1.71, 9.31] | 1.27 | 0.208 |

| Age | 0.26 | 0.43 | [−0.52, 1.06] | 0.61 | 0.542 |

| Residence in Canada | −0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.02] | −0.76 | 0.452 |

| English-speaking self-rating | 0.52 | 0.11 | [0.29, 0.74] | 4.60 | <0.001 |

| Random effects | Variance | SD | Criterion | Estimate | |

| Speaker (intercept) | 27.39 | 5.23 | Log-likelihood | −658.44 | |

| Pair (intercept) | 72.44 | 8.51 | AIC | 1350.90 | |

| BIC | 1402.30 | ||||

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion, BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

Table A3.

Interactional Behavior.

Table A3.

Interactional Behavior.

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 68.64 | 20.15 | [29.23, 106.79] | 3.41 | 0.001 |

| Rating type | −15.17 | 2.77 | [−20.56, −9.77] | −5.47 | <0.001 |

| Female speakers: perceived vs. actual | −15.98 | 2.68 | [−21.27, −10.69] | −5.97 | <0.001 |

| Male speakers: perceived vs. actual | −4.46 | 2.72 | [−9.86, 0.94] | −1.64 | 0.110 |

| Speaker-level covariates | |||||

| Extraversion | −0.57 | 2.23 | [−4.69, 3.66] | −0.26 | 0.799 |

| Negative emotion | 0.14 | 1.95 | [−3.44, 3.80] | 0.07 | 0.943 |

| Open-mindedness | 1.70 | 2.44 | [−2.80, 6.19] | 0.70 | 0.489 |

| Conscientiousness | −2.64 | 2.16 | [−6.62, 1.35] | −1.22 | 0.228 |

| Agreeableness | 4.20 | 2.10 | [0.04, 8.36] | 2.00 | 0.048 |

| Age | 0.42 | 0.38 | [−0.28, 1.12] | 1.10 | 0.274 |

| Residence in Canada | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.03] | −0.20 | 0.846 |

| English-speaking self-rating | 0.01 | 0.11 | [−0.20, 0.21] | 0.07 | 0.946 |

| Random effects | Variance | SD | Criterion | Estimate | |

| Speaker (intercept) | 84.64 | 9.200 | Log-likelihood | −607.98 | |

| Pair (intercept) | 60.25 | 7.762 | AIC | 1250.00 | |

| BIC | 1301.40 | ||||

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion, BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

Table A4.

Future Consequences of Interaction for Male L2 Speakers.

Table A4.

Future Consequences of Interaction for Male L2 Speakers.

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal liking (R2 = 0.08) | |||||

| (Intercept) | 36.11 | 17.52 | [0.47, 71.75] | 2.06 | 0.047 |

| Perceived rating (metaperception) | 0.21 | 0.20 | [−0.19, 0.61] | 1.06 | 0.296 |

| Actual rating of partner (covariate) | 0.25 | 0.20 | [−0.15, 0.65] | 1.26 | 0.217 |

| Speaking skill (R2 = 0.01) | |||||

| (Intercept) | 54.24 | 17.94 | [17.74, 90.74] | 3.02 | 0.005 |

| Perceived rating (metaperception) | 0.17 | 0.26 | [−0.36, 0.70] | 0.65 | 0.518 |

| Actual rating of partner (covariate) | 0.02 | 0.17 | [−0.32, 0.36] | 0.12 | 0.906 |

| Interactional behavior (R2 = 0.09) | |||||

| (Intercept) | 32.82 | 18.76 | [−5.34, 70.98] | 1.75 | 0.089 |

| Perceived rating (metaperception) | 0.31 | 0.27 | [−0.24, 0.86] | 1.14 | 0.261 |

| Actual rating of partner (covariate) | 0.15 | 0.23 | [−0.32, 0.62] | 0.66 | 0.512 |

Table A5.

Future Consequences of Interaction for Female L2 Speakers.

Table A5.

Future Consequences of Interaction for Female L2 Speakers.

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal liking (R2 = 0.26) | |||||

| (Intercept) | 32.52 | 13.28 | [5.50, 59.54] | 2.45 | 0.020 |

| Perceived rating (metaperception) | 0.37 | 0.15 | [0.06, 0.68] | 2.40 | 0.022 |

| Actual rating of partner (covariate) | 0.27 | 0.16 | [−0.05, 0.58] | 1.72 | 0.095 |

| Speaking skill (R2 = 0.15) | |||||

| (Intercept) | 44.86 | 12.97 | [18.46, 71.25] | 3.46 | 0.002 |

| Perceived rating (metaperception) | 0.14 | 0.16 | [−0.18, 0.46] | 0.87 | 0.389 |

| Actual rating of partner (covariate) | 0.28 | 0.15 | [−0.02, 0.58] | 1.92 | 0.063 |

| Interactional behavior (R2 = 0.38) | |||||

| (Intercept) | −11.42 | 18.57 | [−49.20, 26.36] | −0.62 | 0.543 |

| Perceived rating (metaperception) | 0.34 | 0.16 | [0.02, 0.66] | 2.16 | 0.038 |

| Actual rating of partner (covariate) | 0.70 | 0.18 | [0.33, 1.07] | 3.80 | 0.001 |

Appendix D. Scatterplot of Interactional Behavior Ratings

Figure A1.

Scatterplot of speakers’ assessments of future consequences of interaction as a function of their actual perceptions of their partners’ interactional behavior (I like partner’s behavior) and their perceived interactional behavior (I think partner likes my behavior, capturing metaperception), separately for female and male students, with the trendlines (using the gam smoothing function) illustrating the best fit to the data.

References

- Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers, and Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68: 255–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoń, Kamil. 2020. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. R Package Version 1.43.17. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, Roy F., and Mark R. Leary. 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin 117: 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boothby, Erica J., Gus Cooney, Gillian M. Sandstrom, and Margaret S. Clark. 2018. The liking gap in conversations: Do people like us more than we think? Psychological Science 29: 1742–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchard, Thomas J., David T. Lykken, Matthew McGue, Nancy L. Segal, and Auke Tellegen. 1990. Sources of human psychological differences: The Minnesota study of twins reared apart. Science 250: 223–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byron, Kris, and Blaine Landis. 2020. Relational misperceptions in the workplace: New frontiers and challenges. Organization Science 31: 223–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Jessica J., John G. Holmes, and Jacquie D. Vorauer. 2011. Cascading metaperceptions: Signal amplification bias as a consequence of reflected self-esteem. Self and Identity 10: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Erika N. 2016. Meta-accuracy and relationship quality: Weighing the costs and benefits of knowing what people really think about you. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 111: 250–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Erika N., and David A. Kenny. 2012. Meta-accuracy: Do we know how others see us? In Handbook of Self-Knowledge. Edited by Simine Vazire and Timothy D. Wilson. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 242–57. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, Erika N., and Maxwell Barranti. 2016. Metaperceptions: Do people know how others perceive them? In The Social Psychology of Perceiving Others Accurately. Edited by Judith A. Hall, Marianne Schmid Mast and Tessa V. West. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 165–82. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, Erika N., Michael Furr R., Simine Vazire, Marina Kouzakova, Johan C. Karremans, Rick B. van Baaren, and Ad van Knippenberg. 2010. Do we know the first impressions we make? Evidence for idiographic meta-accuracy and calibration of first impressions. Social Psychological and Personality Science 1: 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBIE (Canadian Bureau for International Education). 2023. Available online: https://cbie.ca/infographic (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Chambers, John R., Nicholas Epley, Kenneth Savitsky, and Paul D. Windschitl. 2008. Knowing too much: Using private knowledge to predict how one is viewed by others. Psychological Science 19: 542–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkas, Lynn, Fran Hochberg, Alex J. MacGregor, Harold Snieder, and Tim D. Spector. 2000. Happy families: A twin study of humour. Twin Research 3: 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denies, Katrijn, Liesbet Heyvaert, Jonas Dockx, and Rianne Janssen. 2022. Mapping and explaining the gender gap in students’ second language proficiency across skills, countries and languages. Learning and Instruction 80: 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, Kristin, Alice Moon, and Clayton R. Critcher. 2022. Do people know how others view them? Two approaches for identifying the accuracy of metaperceptions. Current Opinion in Psychology 43: 119–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungan, James A., David M. Munguia Gomez, and Nicholas Epley. 2022. Too reluctant to reach out: Receiving social support is more positive than expressers expect. Psychological Science 33: 1300–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlinger, Joyce, and David Dunning. 2003. How chronic self-views influence (and potentially mislead) estimates of performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Assal, Kareem. 2020. 642,000 International Students: Canada Now Ranks 3rd Globally in Foreign Student Attraction. CIC News. Available online: https://www.cicnews.com/2020/02/642000-international-students-canada-now-ranks-3rd-globally-in-foreign-student-attraction-0213763.html#gs.cv7pls (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Elsaadawy, Norhan, and Erika N. Carlson. 2022. Do you make a better or worse impression than you think? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 123: 1407–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, Nicholas, Boaz Keysar, Leaf Van Boven, and Thomas Gilovich. 2004. Perspective taking as egocentric anchoring and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87: 327–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen-Campbell, Lauri A., and William G. Graziano. 2001. Agreeableness as a moderator of interpersonal conflict. Journal of Personality 69: 323–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jussim, Lee, and Kent D. Harber. 2005. Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies. Personality and Social Psychology Review 9: 131–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, David A. 2019. Interpersonal Perception: The Foundation of Social Relationships. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, Mark R. 2005. Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: Getting to the root of self-esteem. European Review of Social Psychology 16: 75–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy, Thomas E., Linda Albright, David A. Kenny, Fredric Agatstein, and Lynn Winquist. 1997. Interpersonal perception and metaperception in nonoverlapping social groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72: 390–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]