Aspectual se and Telicity in Heritage Spanish Bilinguals: The Effects of Lexical Access, Dominance, Age of Acquisition, and Patterns of Language Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

| (1) | María | se | comió | la | manzana. |

| María | CL | eat-3.S.PST | the | apple | |

| ‘María ate the apple (completely).’ | |||||

| (2) | Maria ate the apple. |

2. Telicity

| (3) | Telicity |

| A predicate ψ is telic if and only if for any event e ψ describes, ψ does not describe any subevent of e. |

| (4) | Maximization in expressions with aspectual se |

| An expression with aspectual se and predicate ψ that takes theme x and describes event e is true if and only if (i) the whole of x (as picked out by the cover) participates in e, and (ii) the scale s associated with ψ in e is bounded. |

3. Lexical Access, Dominance, Age of Acquisition, and Patterns of Language Use

3.1. Lexical Access

3.2. Dominance

3.3. Age of Acquisition and Patterns of Language Use

4. Research Questions and Variables

- Are the heritage speakers’ telicity interpretations sensitive to the presence of se in Spanish? Are their interpretations sensitive to the boundedness of scalar verbs in English?

- Do levels of lexical access, language dominance, age of acquisition, and patterns of language use affect the interpretation of telicity/maximization indicators (maximizers) in English and Spanish among Spanish heritage speakers?

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Tasks

5.1.1. Multilingual Naming Test (MiNT)

5.1.2. The Bilingual Language Profile (BLP)

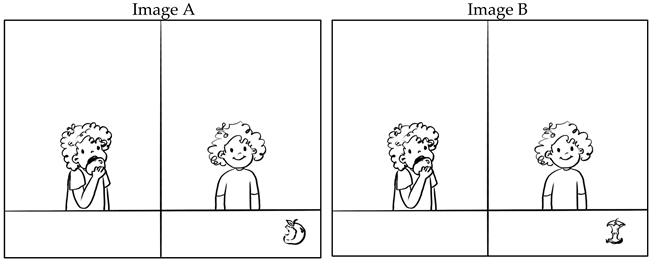

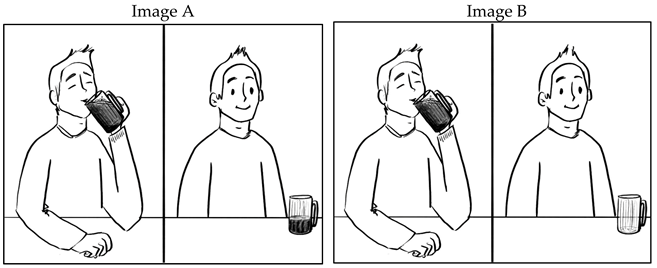

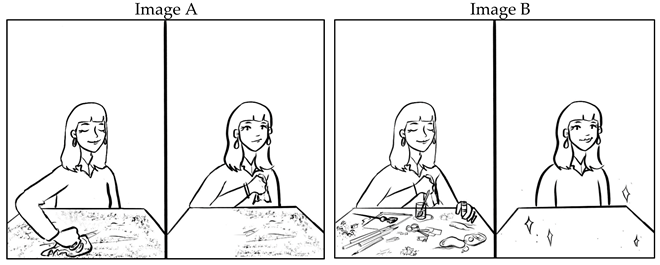

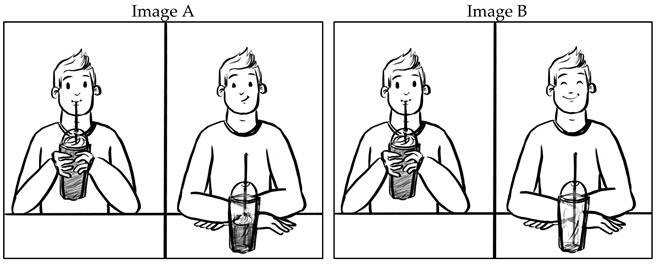

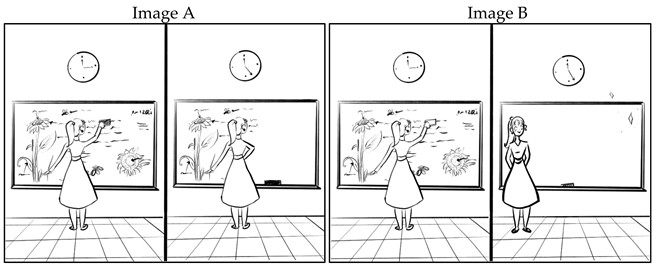

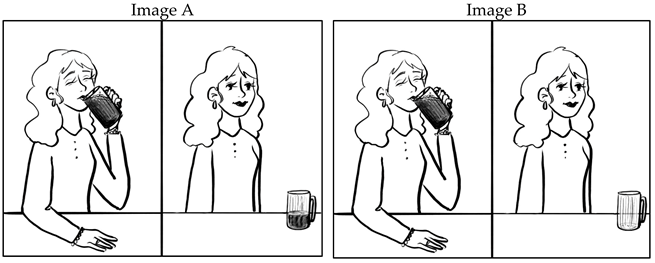

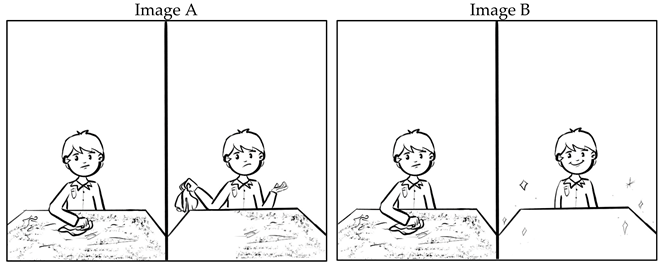

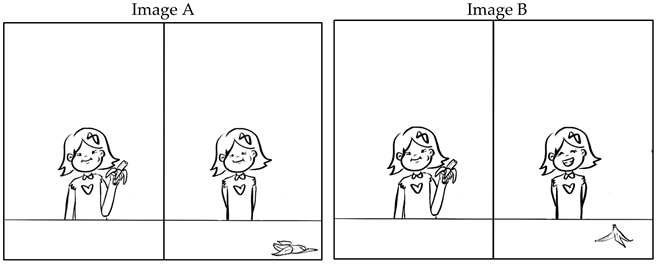

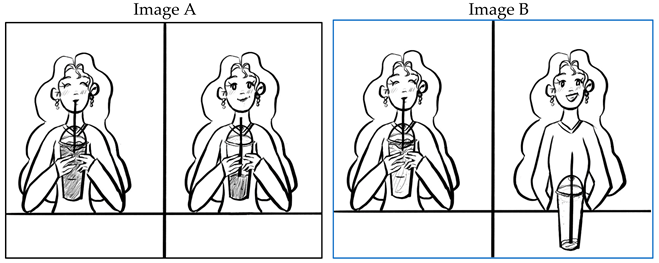

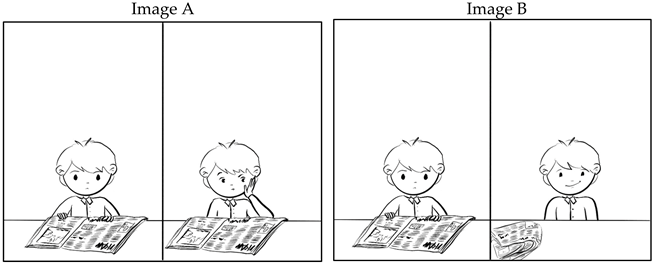

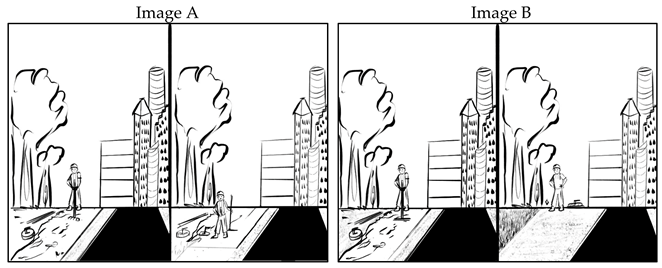

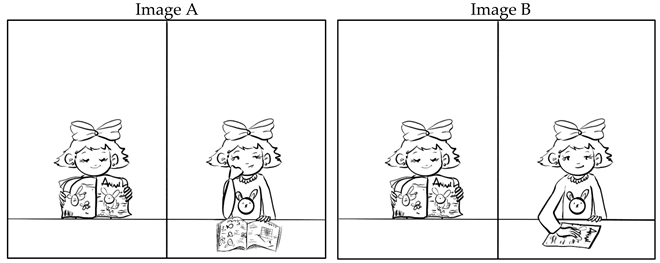

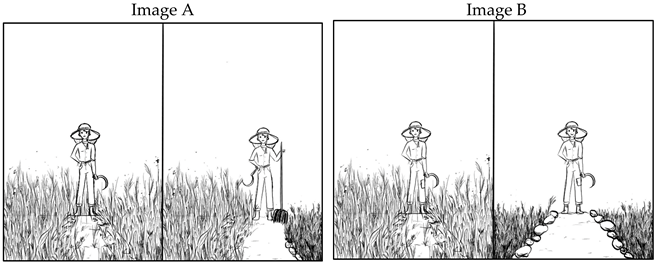

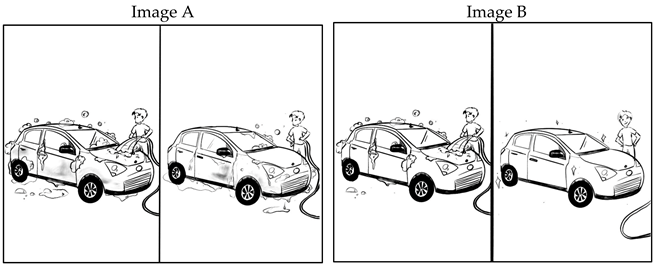

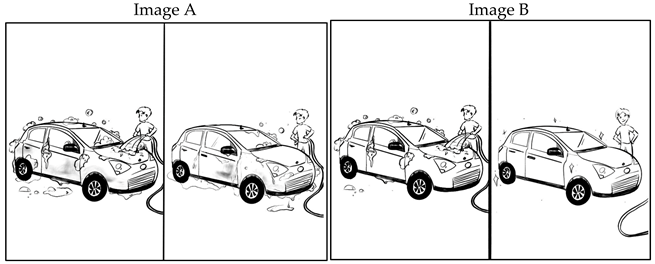

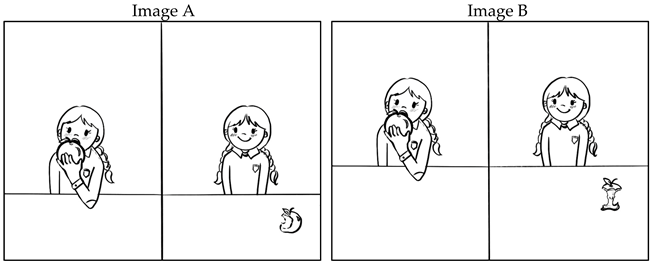

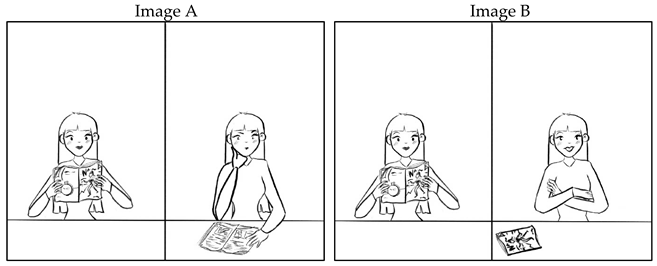

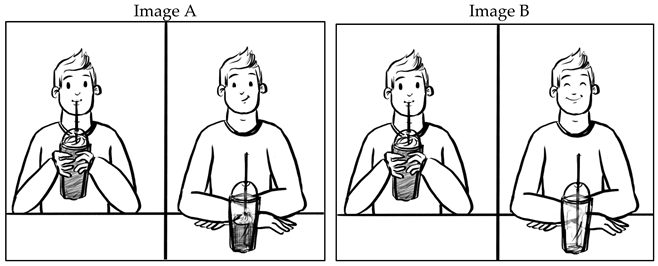

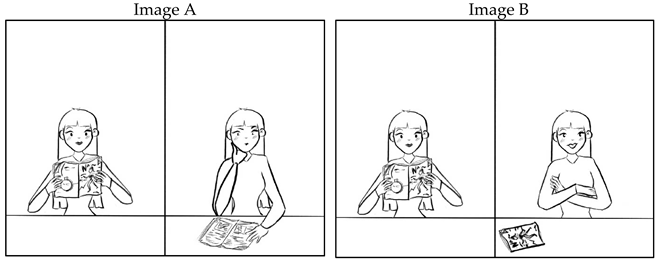

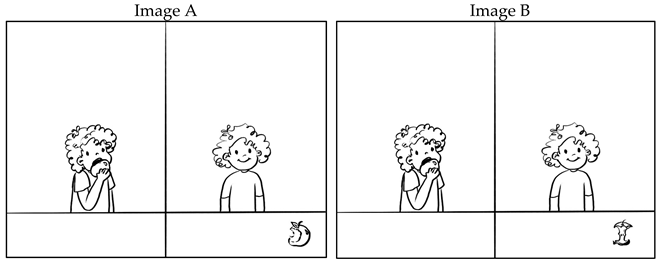

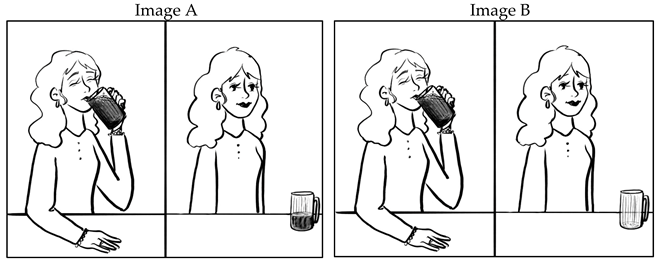

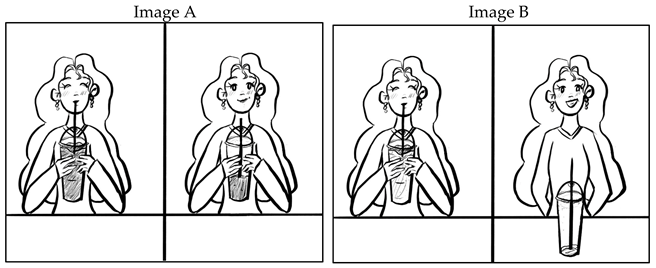

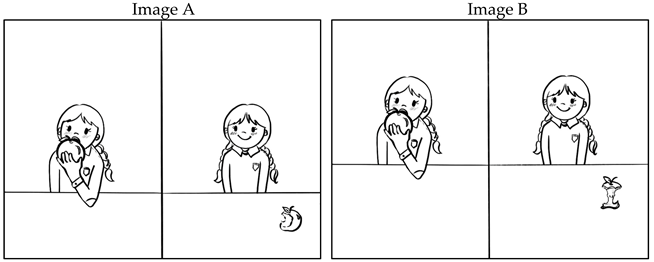

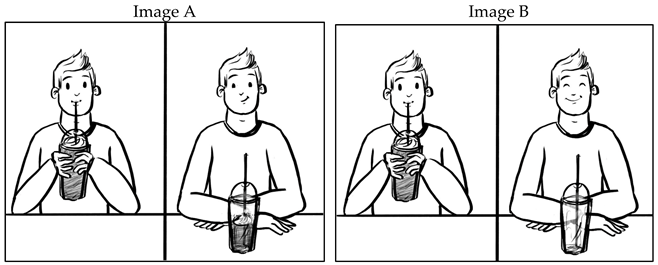

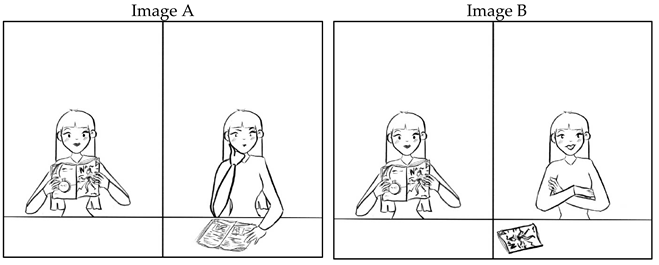

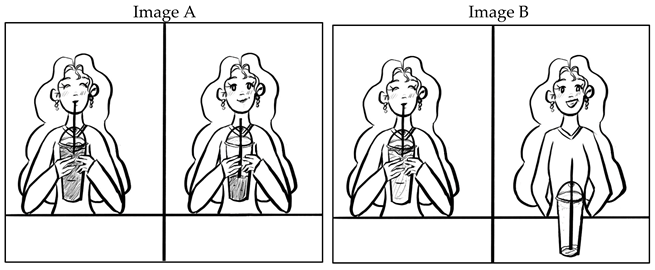

5.1.3. Experimental Task

| (5) | a. | The dad drank the beer. | (bounded scalar verb, telic) |

| b. | The dad widened the path. | (unbounded scalar verb, atelic) |

| (6) | a. | El papá se tomó la cerveza | (with se, telic) |

| b. | El papá tomó la cerveza | (without se, ±atelic) |

5.1.4. Participants

5.1.5. Statistical Analysis

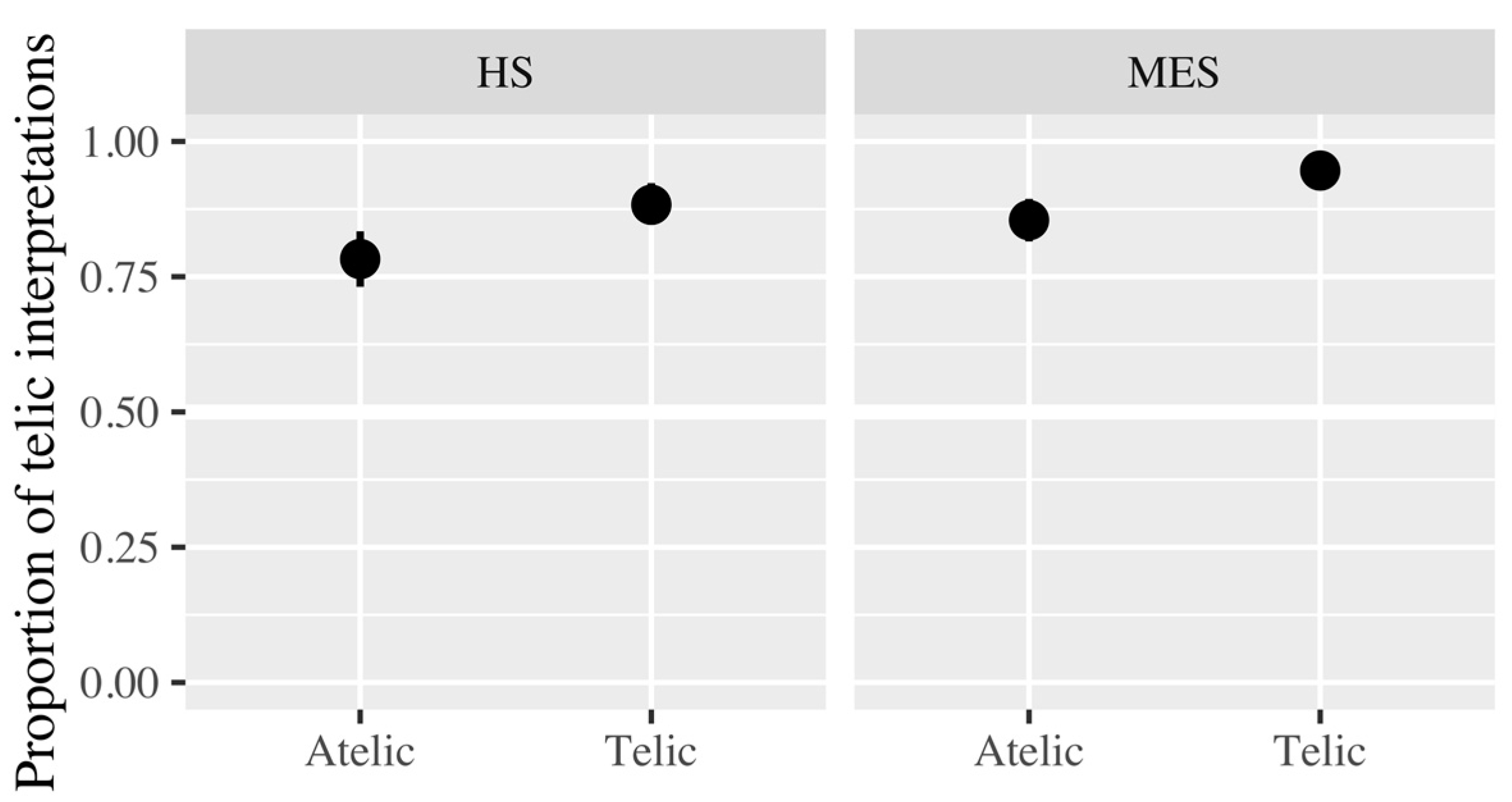

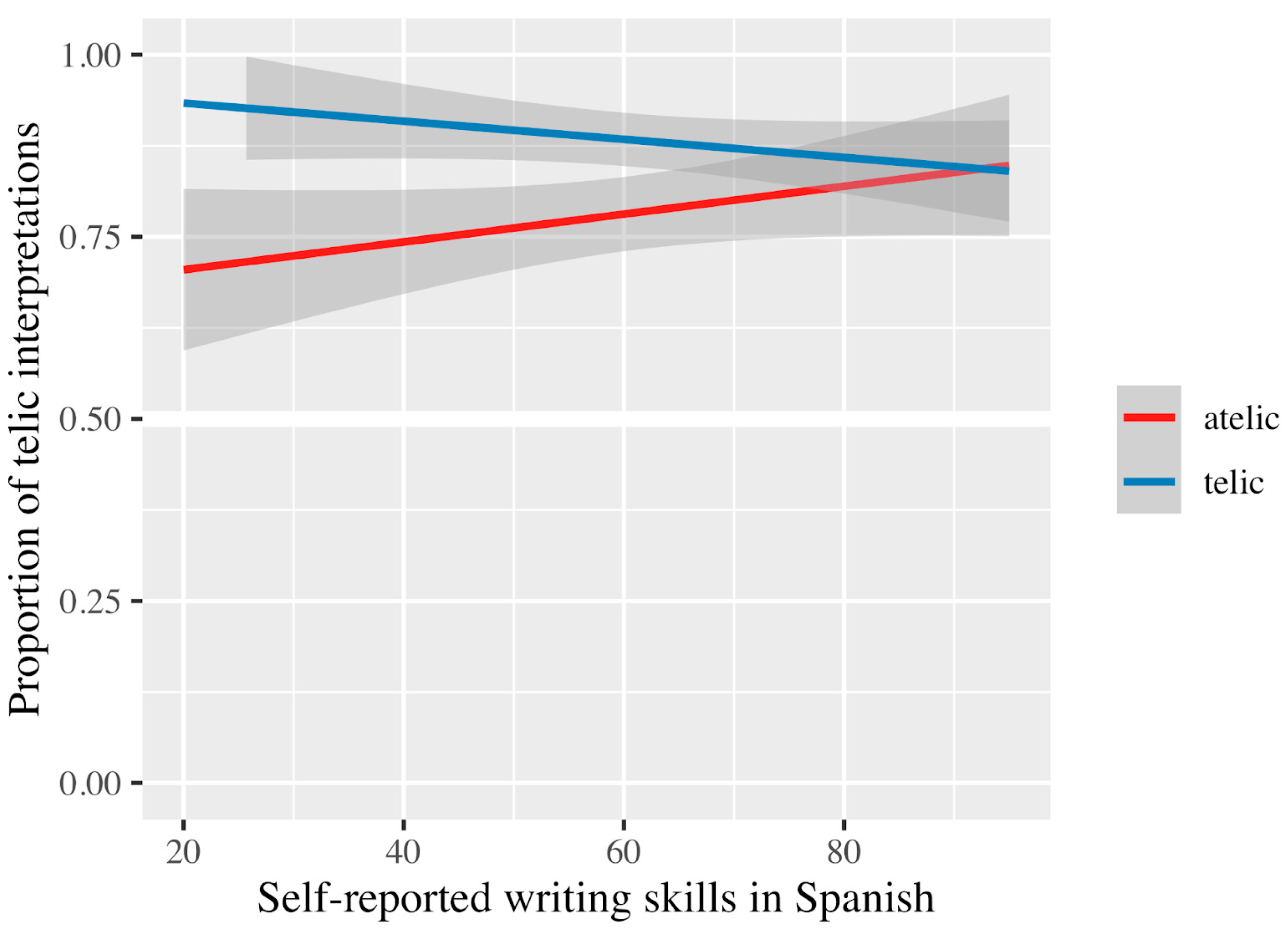

6. Results

6.1. The MiNT and BLP Results

6.2. Picture Selection Task: English

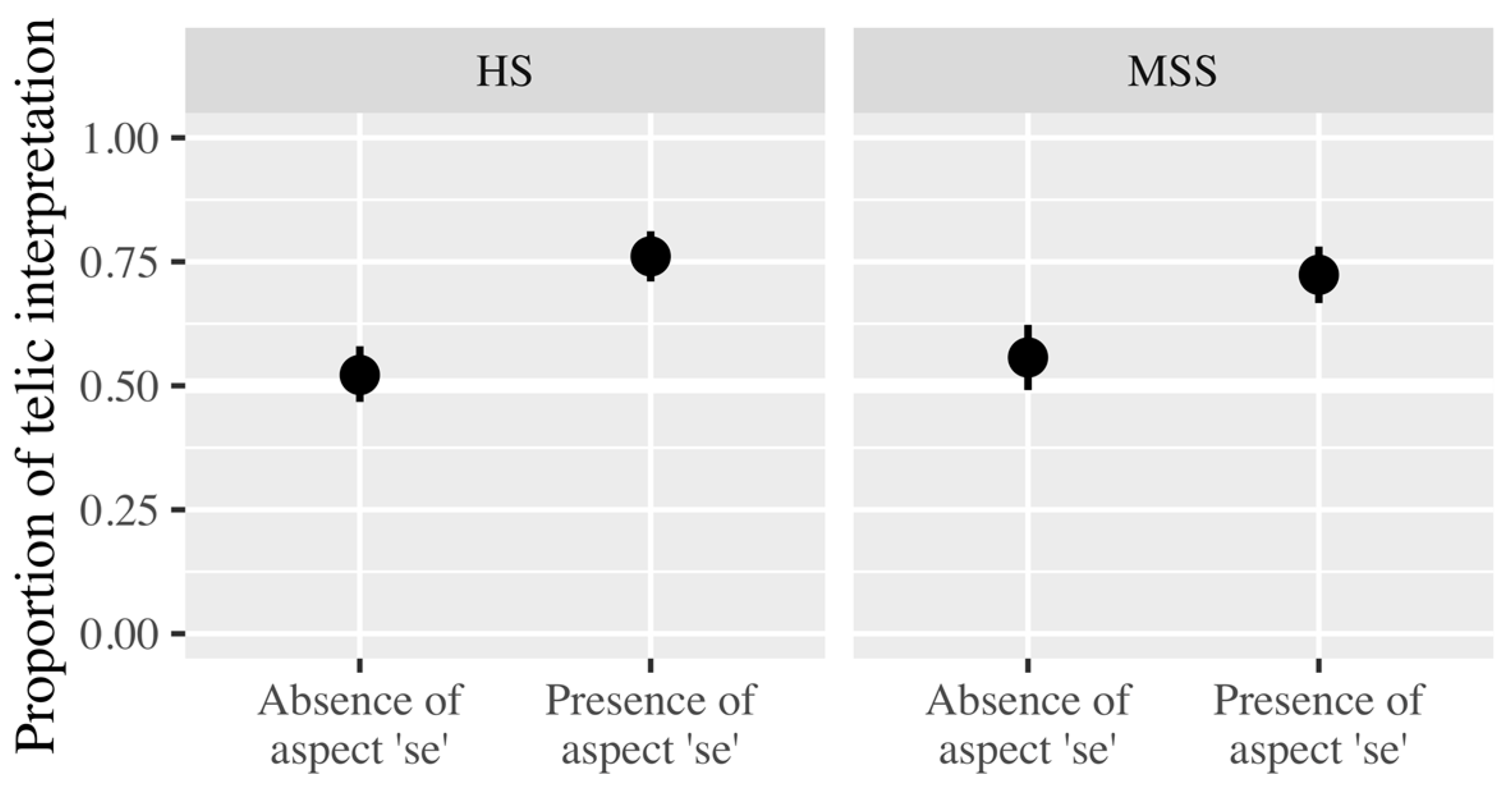

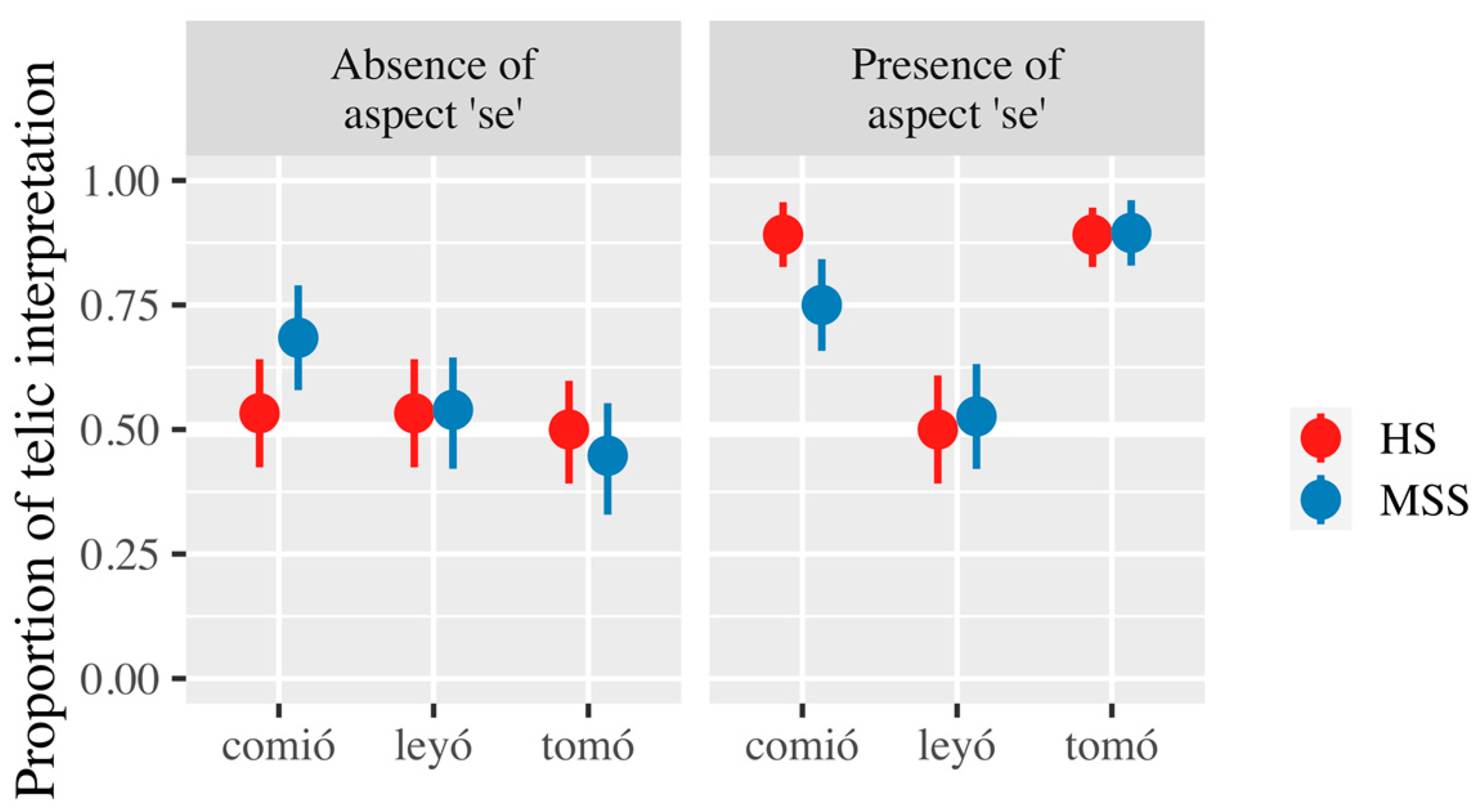

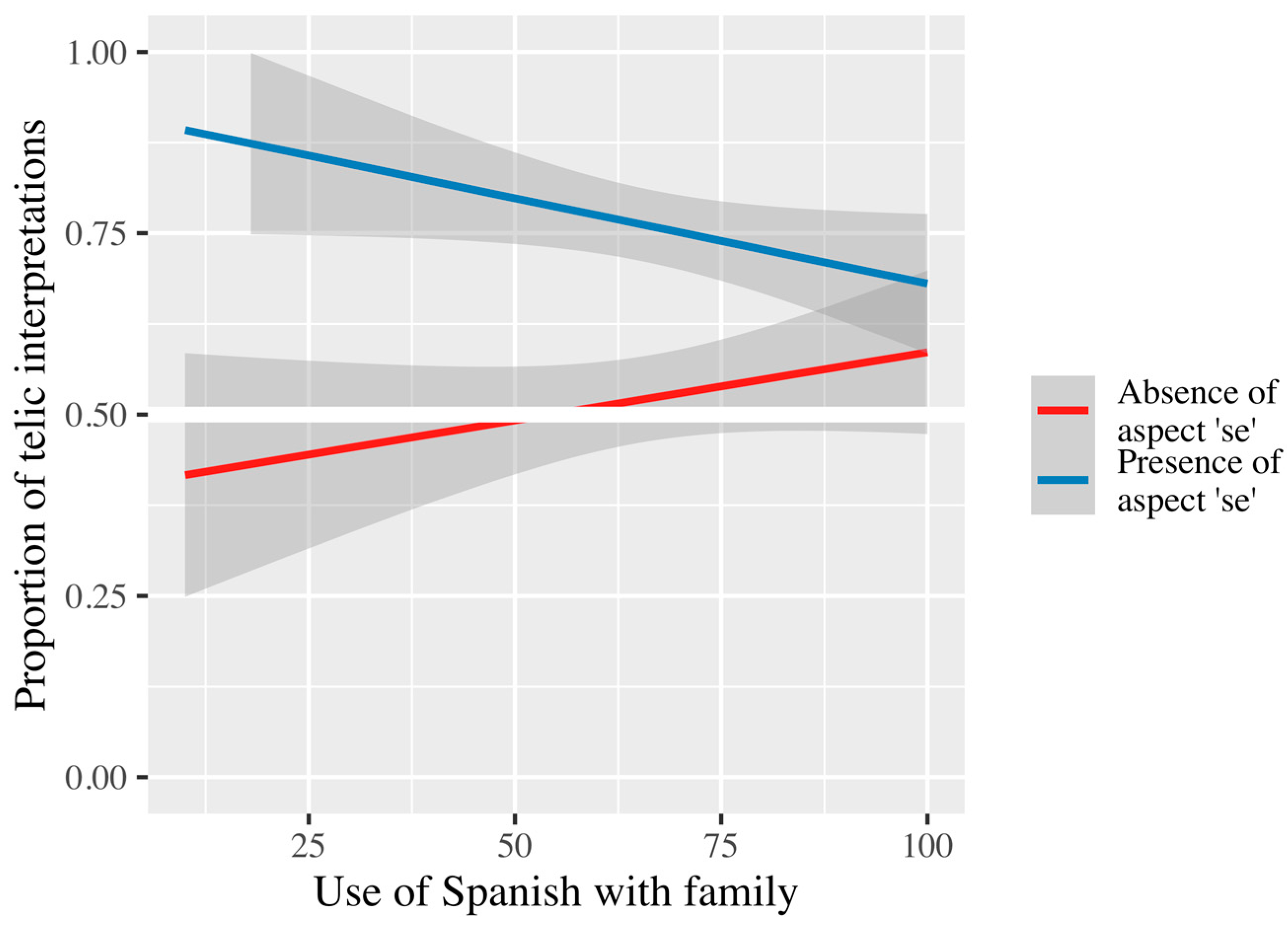

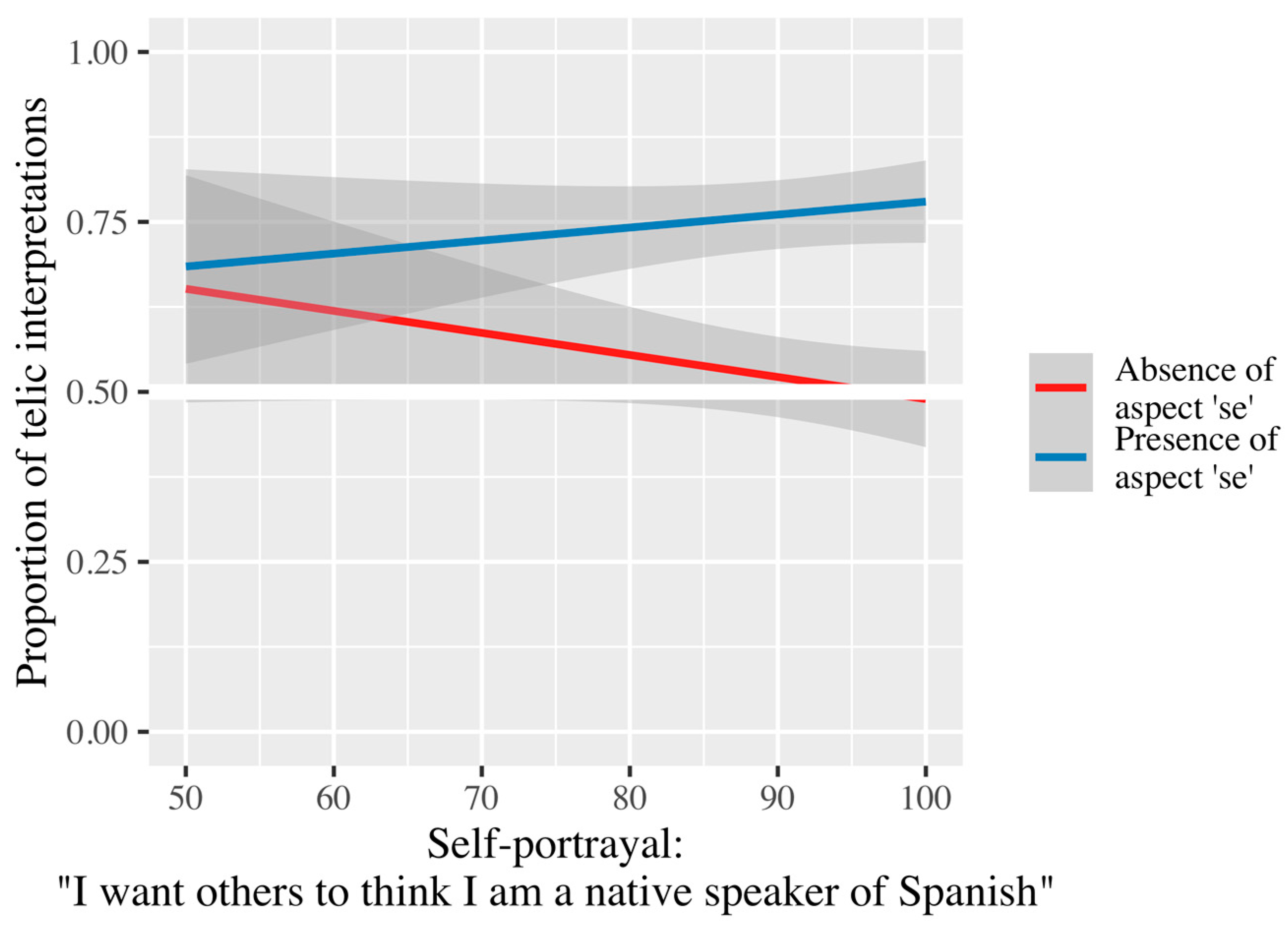

6.3. Picture Selection Task: Spanish

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Experimental Items

- The boy ate the apple.

- The dad drank the beer.

- The teacher cleaned the table.

- The boy ate the banana.

- The dad drank the smoothie.

- The teacher cleaned the blackboard.

- The girl ate the apple.

- The mom drank the beer.

- The student cleaned the table.

- The girl ate the banana.

- The mom drank the smoothie.

- The student cleaned the blackboard.

- The boy read the magazine.

- The dad widened the path.

- The teacher washed the car.

- The boy read the newspaper.

- The dad widened the sidewalk.

- The teacher washed the truck.

- The girl read the magazine.

- The mom widened the path.

- The student washed the car.

- The girl read the newspaper.

- The mom widened the sidewalk.

- The student washed the car.

- La niña se comió la manzana.

- El papá se tomó la cerveza.

- La profesora se leyó la revista.

- La niña se comió el plátano.

- El papá se tomó el licuado.

- La profesora se leyó el periódico.

- El niño se comió la manzana.

- La mamá se tomó la cerveza.

- El estudiante se leyó la revista.

- El niño se comió el plátano.

- La mamá se tomó el licuado.

- El estudiante se leyó el periódico.

- La niña comió la manzana.

- El papá tomó la cerveza.

- La profesora leyó la revista.

- La niña comió el plátano.

- El papá tomó el licuado.

- La profesora leyó el periódico.

- El niño comió la manzana.

- La mamá tomó la cerveza.

- El estudiante leyó la revista.

- El niño comió el plátano.

- La mamá tomó el licuado.

- El estudiante leyó el periódico.

| 1 | See these works for further details of the model, as well as for extensive literature on the topic. |

| 2 | C is a cover of mereological object x (i.e., x has parts that relate to the whole) if and only if C is a set whose sum is x. |

| 3 | The case of aspectual se is similar to what takes place in other languages, e.g., Slavic languages and Hungarian. The issue of telicity strategies falls under maximization or maximalization (Filip 2008; Kardos 2016). Key here is that maximization picks out the largest unique event in the denotation of a predicate, thus guaranteeing telicity (as no event subpart can be described in similar terms to the whole event). |

| 4 | See Martínez Vera (2022) and references therein for discussion of particles in English, which, crucially, are not maximizing means. Specfically, maximizers such as aspectual se (or its counterparts in Slavic languages or Hungarian, as Martínez Vera 2022 discusses) have an overarching effect on the whole event, i.e., on how the relevant scale and the theme are mapped into the event. English particles do not fix these aspects in the relevant sense. Thus, for instance, predicates in which the theme has an unspecified amount, e.g., eat up sandwiches (where sandwiches has cumulative reference), are possible, in contrast to cases with aspectual se as the ones discussed in this paper, where the theme’s quantity must be specified. |

| 5 | The clitic se in Spanish can be interpreted as a reflexive clitic as in María se mira en el espejo ‘Maria looks at herself in the mirror’, a dative as in Se lo dimos ‘We gave it to him/her/them’, a detransitiver with change-of-state verbs as in Se rompió ‘It broke’ and psychological verbs as in Ella se asustó ‘She got frightened’, or even as an ethical dative as in José se ganó la lotería ‘Jose won the lottery (for himself)’. We focus only on the aspectual interpretation of se in contexts where there is a contrast between two possible interpretations: a telic and an atelic one. |

| 6 | One possible reason for these particular results is a restructuring of the feature hierarchy used to determine telicity in the bilinguals’ Spanish. In this case, there seems to be a higher reliance on se as a marker of telicity. This could be a case of fixating on one possible alignment (Sánchez 2019), or association of certain phonological or morphological features with lexical-semantic meanings for more efficient processing rather than exhibiting the typical variability found in bilingual heritage speakers. Further research is needed in this regard. |

References

- Abutalebi, Jubin, and David Green. 2007. Bilingual language production: The neurocognition of language representation and control. Journal of Neurolinguistics 20: 242–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amengual, Mark. 2023. Cross-language influences in the acquisition of L2 and L3 phonology. In Cross-language Influences in Bilingual Processing and Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Irina Elgort, Anna Siyanova-Chanturia and Marc Brysbaert. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 16, pp. 74–99. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Grant. 2013. Agentive reflexive clitics and transitive se constructions in Spanish. Borealis. An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 2: 81–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basilico, David. 2010. The se clitic and its relationship to paths. Probus. International Journal of Romance Linguistics 22: 271–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavers, John. 2011. On affectedness. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29: 335–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedore, Lisa M., Elizabeth D. Peña, Connie L. Summers, Karin M. Boerger, Maria D. Resendiz, Kai Greene, Thomas M. Bohman, and Ronald B. Gillam. 2012. The measure matters: Language dominance profiles across measures in Spanish–English bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 616–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen, Fergus Craik, and Gigi Luk. 2008a. Cognitive control and lexical access in younger and older bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 34: 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen, Fergus Craik, and Gigi Luk. 2008b. Lexical access in bilinguals: Effects of vocabulary size and executive control. Journal of Neurolinguistics 21: 522–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsong, David. 2014. Dominance and age in bilingualism. Applied Linguistics 35: 374–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsong, David, Libby M. Gertken, and Mark Amengual. 2012. Bilingual Language Profile: An Easy-to-Use Instrument to Assess Bilingualism. Austin: COERLL, University of Texas at Austin. [Google Scholar]

- Brisson, Christine M. 1998. Distributivity, Maximality, and Floating Quantifiers. Ph.D. dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Campanini, Cinzia, and Florian Schäfer. 2011. Optional Se-constructions in Romance: Syntactic encoding of conceptual information. Handout from talk at Generative Linguistics in the Old World. Available online: https://amor.cms.hu-berlin.de/~schaeffl/papers/glow34.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Cuartero, Marina, Eleonora Rossi, Ester Navarro, and Diego Pascual y Cabo. 2023. Mind the net! Unpacking the contributions of social network science for heritage and Bilingualism research. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics 2: 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro, and Lauren Miller. 2015. The protracted acquisition of past tense aspectual values in child heritage Spanish. In Hispanic Linguistics at the Crossroad: Theoretical Linguistics, Language Acquisition and Language Contact. Edited by Rachel Klassen, Juana M. Liceras and Elena Valenzuela. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 211–30. [Google Scholar]

- De Carli, Fabrizio, Barbara Dessi, Manuela Mariani, Nicola Girtler, Alberto Greco, Guido Rodriguez, Laura Salmon, and Mara Morelli. 2015. Language use affects proficiency in Italian-Spanish bilinguals irrespective of age of second language acquisition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 18: 324–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubiel, Bozena, and Eithne Guilfoyle. 2021. Early shifts in the heritage language strength: A comparison of lexical access and accuracy in bilingual and monolingual children. International Journal of Bilingualism 25: 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, Alexandra L., and Jean E. Fox Tree. 2009. A quick, gradient bilingual dominance scale. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 12: 273–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip, Hana. 2008. Events and Maximalization: The Case of Telicity and Perfectivity. In Theoretical and Crosslinguistic Approaches to the Semantics of Aspect. Edited by Susan Rothstein. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 217–56. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Cristina, and Esther Rinke. 2020. The relevance of language-internal variation in predicting heritage language grammars. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23: 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Cristina, Ana Lúcia Santos, Alice Jesus, and Rui Marques. 2017. Age and input effects in the acquisition of mood in Heritage Portuguese. Journal of Child Language 44: 795–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Tejada, Aída, Alejandro Cuza, and Eduardo Gerardo Lustres Alonso. 2023. The production and comprehension of Spanish se use in L2 and heritage Spanish. Second Language Research 39: 301–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertken, Libby M., Mark Amengual, and David Birdsong. 2014. Assessing Language Dominance with the Bilingual Language Profile. In Measuring L2 Proficiency. Edited by Pascale Leclercq, Amanda Edmonds and Heather Hilton. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 208–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gharibi, Khadijeh, and Frank Boers. 2017. Influential factors in incomplete acquisition and attrition of young heritage speakers’ vocabulary knowledge. Language Acquisition 24: 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancaspro, David. 2019. The late (r) bird gets the verb? Effects of age of acquisition of English on adult heritage speakers’ knowledge of subjunctive mood in Spanish. Languages 4: 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, John, and Elizabeth Ramirez. 2004. Maintaining a Minority Language: A Case Study of Hispanic Teenagers. Buffalo: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, Michele, Julio César López Otero, and Esther Hur. 2023. How frequent are these verbs?: An exploration of lexical frequency in bilingual children’s acquisition of subject-verb agreement morphology. Isogloss: Open Journal of Romance Linguistics 9: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, Tamar H., Gali H. Weissberger, Elin Runnqvist, Rosa I. Montoya, and Cynthia M. Cera. 2012. Self-ratings of spoken language Dominance: A Multilingual Naming Test (MINT) and preliminary norms for young and aging Spanish-English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, Tamar H., Timothy J. Slattery, Diane Goldenberg, Eva Van Assche, Wouter Duyck, and Keith Rayner. 2011. Frequency drives lexical access in reading but not in speaking: The frequency-lag hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 140: 186–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heredia, Roberto R. 1997. Bilingual memory and hierarchical models: A case for language dominance. Current Directions in Psychological Science 6: 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Esther, Julio Cesar Lopez Otero, and Liliana Sanchez. 2020. Gender agreement and assignment in Spanish heritage speakers: Does frequency matter? Languages 5: 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Esther. 2020. Verbal lexical frequency and DOM in heritage speakers of Spanish. In The Acquisition of Differential Object Marking. Edited by Silvina Montrul and Ayşe Gürel. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 207–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Jian, Alejandro Cuza, and Julio López-Otero. 2020. The acquisition of personal a among Chinese-speaking L2 learners of Spanish. In Current Theoretical and Applied Perspectives on Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics. Edited by Idoia Elola and Diego Pascual y Cabo. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 27, pp. 233–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kardos, Éva. 2016. Telicity marking in Hungarian. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 1: 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenbaum, Jessica G., Lisa M. Bedore, Elizabeth D. Peña, Li Sheng, Ilknur Mavis, Rajani Sebastian-Vaytadden, Grama Rangamani, Sofia Vallila-Rohter, and Swathi Kiran. 2019. The influence of proficiency and language combination on bilingual lexical access. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 22: 300–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Christopher, and Beth Levin. 2008. Measure of change: The adjectival core of degree achievements. In Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics and Discourse. Edited by Louise McNally and Christopher Kennedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 156–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Kitaek, and Hyunwoo Kim. 2022. Sequential bilingual heritage children’s L1 attrition in lexical retrieval: Age of acquisition versus language experience. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 25: 537–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, Judith F., Tamar H. Gollan, Matthew Goldrick, Victor Ferreira, and Michele Miozzo. 2014. Speech Planning in Two Languages: What Bilinguals Tell Us about Language Production. In The Oxford Handbook of Language Production. Edited by Matthew Andrew Goldrick, Victor S. Ferreira and Michele Miozzo. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 165–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Jason Rothman. 2018. Terminology matters! Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals are heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 564–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Valerie P. C., Susan J. Rickard Liow, Michelle Lincoln, Yiong Huak Chan, and Mark Onslow. 2008. Determining language dominance in English–Mandarin bilinguals: Development of a self-report classification tool for clinical use. Applied Psycholinguistics 29: 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Link, Godehard. 1983. The logical analysis of plural and mass terms: A lattice-theoretical approach. In Meaning, Use and Interpretation of Language. Edited by Rainer Bäuerle, Christoph Schwarze and Arnim von Stechow. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 302–23. [Google Scholar]

- López-Beltrán, Priscila, and Matthew T. Carlson. 2020. How usage-based approaches to language can contribute to a unified theory of heritage grammars. Linguistics Vanguard 6: 20190072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otero, Julio Cesar. 2020. The Acquisition of the Syntactic and MORPHOLOGICAL properties of Spanish Imperatives in Heritage and Second Language Speakers. Ph.D. dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- López-Otero, Julio Cesar. 2022. Lexical frequency effects on the acquisition of syntactic properties in heritage Spanish: A study on unaccusative and unergative predicates. Heritage Language Journal 19: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Otero, Julio César, Esther Hur, and Michele Goldin. 2023. Syntactic optionality in heritage Spanish: How patterns of exposure and use affect clitic climbing. International Journal of Bilingualism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łyskawa, Paulina, and Naomi Nagy. 2020. Case marking variation in heritage Slavic languages in Toronto: Not so different. Language Learning 70: 122–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macbeth, Alessandra, Natsuki Atagi, Jessica L. Montag, Michelle R. Bruni, and Christine Chiarello. 2022. Assessing language background and experiences among heritage bilinguals. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 993669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, Jonathan E. 2017. Spanish aspectual se as an indirect object reflexive: The import of atelicity, bare nouns, and leísta PCC repairs. Probus. International Journal of Romance Linguistics 29: 73–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, Viorica, Henrike K. Blumenfeld, and Margarita Kaushanskaya. 2007. The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing language profiles in bilinguals and multilinguals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 50: 940–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Vera, Gabriel. 2021. Degree achievements and maximalization: A cross-linguistic perspective. Glossa: A Journal of GENERAL linguistics 6: 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Vera, Gabriel. 2022. Revisiting aspectual se in Spanish: Telicity, statives and maximization. The Linguistic Review 39: 159–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Lauren, and Alejandro Cuza. 2013. On the status of tense and aspect morphology in child heritage Spanish: An analysis of accuracy levels. In Proceedings of the 12th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference. Edited by Jennifer Cabrelli, Tiffany Judy and Diego Pascual y Cabo. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 117–29. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2002. Incomplete acquisition and attrition of Spanish tense/aspect distinctions in adult bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 5: 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2004. The Acquisition of Spanish. Morphosyntactic Development in Monolingual and Bilingual L1 Acquisition and in Adult L2 Acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2006. On the bilingual competence of Spanish heritage speakers: Syntax, lexical-semantics and processing. International Journal of Bilingualism 10: 37–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2008. Incomplete Acquisition in Bilingualism. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2014. Structural changes in Spanish in the United States: Differential object marking in Spanish heritage speakers across generations. Lingua 151: 177–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Rebecca Foote. 2014. Age of acquisition interactions in bilingual lexical access: A study of the weaker language of L2 learners and heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism 18: 274–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Silvia Perpiñán. 2011. Assessing Differences and Similarities between Instructed Heritage Language Learners and L2 Learners in Their Knowledge of Spanish Tense-Aspect and Mood (TAM) Morphology. Heritage Language Journal 8: 90–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, Rebecca Foote, and Silvia Perpiñán. 2008. Gender agreement in adult second language learners and Spanish heritage speakers: The effects of age and context of acquisition. Language learning 58: 503–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, Daniel J. 2023. Measuring bilingual language dominance: An examination of the reliability of the Bilingual Language Profile. Language Testing 40: 521–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Walter A. 2015. A Scalar Analysis of Again-Ambiguities. Journal of Semantics 32: 373–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Cortés, Silvia, Michael T. Putnam, and Liliana Sánchez. 2019. Differential Access: Asymmetries in Accessing Features and Building Representations in Heritage Language Grammars. Languages 4: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2006. Acquisition of Russian: Uninterrupted and incomplete scenarios. Glossos 8: 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2011. Reanalysis in adult heritage language: A case for attrition. Studies in Studies in Second Language Acquisition 33: 305–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Michael T., and Liliana Sánchez. 2013. What’s so incomplete about incomplete acquisition? A prolegomenon to modeling heritage grammars. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3: 478–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Rah, Anne. 2010. Transfer in L3 sentence processing: Evidence from relative clause attachment ambiguities. International Journal of Multilingualism 7: 147–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinke, Esther, and Cristina Flores. 2018. Another look at the interpretation of overt and null pronominal subjects in bilingual language acquisition: Heritage Portuguese in contact with German and Spanish. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3: 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinke, Esther, Cristina Flores, and Aldona Sopata. 2019. Heritage Portuguese and heritage Polish in contact with German: More evidence on the production of objects. Languages 4: 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Liliana. 2019. Bilingual Alignments. Languages 4: 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, Montserrat. 2000. Events and Predication: A New Approach to Syntactic Processing in English and Spanish. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Scontras, Gregory, Zuzanna Fuchs, and Maria Polinsky. 2015. Heritage language and linguistic theory. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, Christine. 2019. Dominance, proficiency, and Spanish heritage speakers’ production of English and Spanish vowels. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 41: 123–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 2014. Bilingual Language Acquisition: Spanish and English in the First Six Years. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tamamaki, Kinko. 1993. Language dominance in bilinguals’ arithmetic operations according to their language use. Language Learning 43: 239–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, Seth, and Natasha Tokowicz. 2021. Language proficiency is only part of the story: Lexical access in heritage and non-heritage bilinguals. Second Language Research 37: 681–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | N | Age | AoA (English) |

|---|---|---|---|

| English monolinguals | 30 (F = 14) | 18–62 (M = 35.73) | n/a |

| Spanish monolinguals | 19 (F = 19) | 30–57 (M = 42.63) | n/a |

| Spanish heritage speakers | 23 (F = 19) | 18–30 (M = 20.04) | 0–13 (M = 4.04) |

| English Monolinguals | Spanish Monolinguals | Spanish Heritage Speakers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| English MiNT scores | Spanish MiNT scores | English MiNT scores | Spanish MiNT scores |

| Range = 56–68/68; M= 63.7/68; SD = 2.57 | Range = 50–63/68; M = 58.5/68; SD = 3.59 | Range = 49–68/68; M = 58.9/68; SD = 4.54 | Range = 37–61/68; M = 50.1/68; SD = 6.22 |

| English Monolinguals | Spanish Monolinguals | Spanish Heritage Speakers |

|---|---|---|

| Range = −215 to −110; M = −178; SD = 26.6 | Range = 20.6 to 202; M = 111; SD = 55.1 | Range= −87.5 to 84.1; M= −31; SD = 41.5 |

| English Monolinguals | Spanish Monolinguals | Spanish Heritage Speakers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| English scores | Spanish scores | English scores | Spanish scores |

| Range = 50 to 100; M = 95/100; SD = 14 | Range = 30 to 100; M = 82.1/100; SD = 23.1 | Range = 0 to 90; M = 34.1/100; SD = 21.1 | Range = 10 to 100; M = 65.9/100; SD = 21.1 |

| Condition | Spanish Heritage Speakers | Monolingual English Speakers |

|---|---|---|

| Bounded scalar verb | M= 0.88; SD= 0.32 | M= 0.88; SD= 0.32 |

| Unbounded scalar verb | M= 0.78; SD= 0.41 | M= 0.86; SD= 0.35 |

| Condition | Spanish Heritage Speakers | Monolingual Spanish Speakers |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of se | M= 0.76; SD= 0.43 | M= 0.72; SD= 0.45 |

| Absence of se | M= 0.52; SD= 0.50 | M= 0.56; SD= 0.50 |

| Condition | Verb | Spanish Heritage Speakers | Monolingual Spanish Speakers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of se | comió | M = 0.89; SD = 0.31 | M = 0.75; SD = 0.44 |

| leyó | M = 0.50; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.53; SD = 0.50 | |

| tomó | M = 0.89; SD = 0.31 | M = 0.90; SD = 0.31 | |

| Absence of se | comió | M = 0.53; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.68; SD = 0.47 |

| leyó | M = 0.53; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.54; SD = 0.50 | |

| tomó | M = 0.50; SD = 0.50 | M = 0.45; SD = 0.50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez Vera, G.; López Otero, J.C.; Sokolova, M.Y.; Cleveland, A.; Marshall, M.T.; Sánchez, L. Aspectual se and Telicity in Heritage Spanish Bilinguals: The Effects of Lexical Access, Dominance, Age of Acquisition, and Patterns of Language Use. Languages 2023, 8, 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030201

Martínez Vera G, López Otero JC, Sokolova MY, Cleveland A, Marshall MT, Sánchez L. Aspectual se and Telicity in Heritage Spanish Bilinguals: The Effects of Lexical Access, Dominance, Age of Acquisition, and Patterns of Language Use. Languages. 2023; 8(3):201. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030201

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez Vera, Gabriel, Julio César López Otero, Marina Y. Sokolova, Adam Cleveland, Megan Tzeitel Marshall, and Liliana Sánchez. 2023. "Aspectual se and Telicity in Heritage Spanish Bilinguals: The Effects of Lexical Access, Dominance, Age of Acquisition, and Patterns of Language Use" Languages 8, no. 3: 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030201

APA StyleMartínez Vera, G., López Otero, J. C., Sokolova, M. Y., Cleveland, A., Marshall, M. T., & Sánchez, L. (2023). Aspectual se and Telicity in Heritage Spanish Bilinguals: The Effects of Lexical Access, Dominance, Age of Acquisition, and Patterns of Language Use. Languages, 8(3), 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030201