Abstract

Ideophones are believed to exhibit distinct phonotactic patterns compared to regular language, in their expressiveness. Vowel harmony can be observed in ideophones in Modern Korean. However, over time, Korean has gradually lost its regular vowel harmony process, due to the influx of foreign words, especially from Chinese, and historical sound changes like the vowel shift of /ɔ/ to different vowel types. Previous studies have mainly focused on the vowel patterns of ideophones without necessarily comparing the degree of vowel harmony between ideophones and other lexical strata. This lack of comparison makes it challenging to assess the level of corruption in vowel harmony specifically within ideophones, relative to other components of the lexicon. To address this gap, this paper examines vowel patterns extracted from the online dictionary of Korean, developed by the National Institute of the Korean Language (NIKL) with contributions from anonymous users and specialists. The analysis specifically explores vowel patterns across lexical items with varying syllable lengths, focusing on the lexical stratum, adverbial parts of speech, and the semantic meaning of the adverbials. This examination aims to assess the regularity of vowel sequencing and determine the extent of purity in vowel harmony patterns. The quantitative analysis of the compiled dictionary provides valuable insights into the degree of irregular phonotactics and its relationship to sound symbolism in Modern Korean.

1. Introduction

Altaic languages, including Korean, exhibit a linguistic characteristic known as vowel harmony (Hattori 1982; H.-M. Sohn 1999; van der Hulst and van de Weijer 1995; Kawahara 2020). In Korean, vowel harmony refers to the categorization of vowels into light or yang (/o a ɔ/) and dark or ying (/u ɨ ɪ ə/) categories. Previous studies have attempted to identify a phonologically natural or phonetically motivated feature, but this endeavor has proven unsuccessful (H.-S. Sohn 1986; Cho 1994; Lee 1984; Kwon 2018). Instead, the vowel types have been defined based on semantic considerations (Cho 1994; Kim-Renaud 1976; H.-M. Sohn 1999; Kwon 2018). This phenomenon of vowel harmony occurs within words and in case markers and predicate suffixes (H.-M. Sohn 1999). In this paper, the terms “dark” and “light” are employed to denote these two categories, although alternative terms such as “ying” and “yang” may be used by other authors.

The phenomenon of vowel harmony in Modern Korean is fascinating, due to the diachronic vowel changes within the language and the influx of borrowed words from other languages. During the 15th and 16th centuries, vowel harmony was consistently observed across the entire vocabulary, with a strict prohibition on the co-occurrence of dark and light vowels within stems. Examples of vowel harmony within that lexicon are illustrated in (1), while examples involving harmony with a verbal suffix are presented in (2), as referenced by Larsen and Heinz (2012).

| (1) | salsal | ‘gently, softly, slowly’ | (LL) |

| culʌŋ-culʌŋ | ‘in clusters’ (e.g., grapes) | (DDDD) | |

| als’oŋtals’oŋ | ‘jumbled, obscure’ | (LLLL) |

| (2) | cap-a | ‘grab’ | (LL) | kipʰ-ʌ | ‘be deep’ | (DD) |

| coh-a | ‘like, be good’ | (LL) | cuk-ʌ | ‘die’ | (DD) | |

| po-a | ‘see’ | (LL) | mʌk-ʌ | ‘eat | (DD) |

Here, “L” on the right-hand side of the examples represents light vowels, and “D” indicates dark vowels.

Extensive research has been conducted on vowel harmony in Korean, both qualitatively and quantitatively, by various scholars. These include Kim-Renaud (1976), Lee (1984), Ahn and Kim (1985), H.-S. Sohn (1986), Park (1990), Lee (1992), Cho (1994), Oh (1998), H.-M. Sohn (1999), Chung (2000), Kwak (2003), Finley (2006), Hong (2008), Hong (2010), Ko (2010), Kwon (2015), Larsen and Heinz (2012), Kwon (2018), and Kim and Nam (2019), among others.

Regarding the historical aspect of qualitative studies on Korean vowel harmony, the vowel harmony system in Modern Korean has undergone significant deterioration compared to the system in Middle Korean. The breakdown of the harmony system began in the mid-15th century, due to the extensive influx of loanwords, especially from the Chinese language, which did not adhere to the harmony pattern (Park 1990). Despite the geographic, historical, and cultural proximity between Korea and China, Korean and Chinese do not belong to the same language family and are not genetically related (H.-M. Sohn 1999). Throughout its extended historical contact with various Chinese dynasties, Korean has, however, borrowed a considerable number of Chinese words and characters, which have become integral parts of the Korean vocabulary (H.-M. Sohn 1999).

Moreover, in Middle Korean, the light (or yang) vowel /ɔ/ underwent a vowel shift, resulting in the dark (or ying) vowel /ɨ/, and sometimes appearing as a light (or yang) /o/ in non-initial syllables. Eventually, it further shifted to another light vowel /a/. Consequently, the spelling for the word ‘to play (an instrument)’ was variously written as /tɔlɔjta/(LLL), /talɨjta/ (LDL), or /talɔjta/ (LLL) in the 18th century (Lee and Ramsey 2011, pp. 262–63). It is important to note that the vowel harmony system is not observed in the case of /talɨjta/ (LDL). These changes have been documented by Park (1990) and Lee and Ramsey (2011).

Despite the aforementioned changes, vowel harmony is still observed in Modern Korean, albeit in two different forms. Verbal suffix harmony and sound-symbolic harmony are the two distinct types of vowel harmony present in the language today, as described by Kim-Renaud (1976), Park (1990), H.-M. Sohn (1999), and other researchers.

Quantitative studies of the Korean vowel system have been conducted by Hong (2010), Larsen and Heinz (2012), Kwon (2018), and Kim and Nam (2019), among others. Hong (2010) conducted a corpus study using Wulimal Khun Sacen, a comprehensive Korean dictionary compiled by the Korean Language Society, containing around 450,000 lexical entries. The lexical entries in the dictionary are classified into native Korean stock (about 35%), Sino-Korean stock (approximately 60%), and borrowings (around 5%) (H.-M. Sohn 1999, pp. 13, 87). In Hong’s study, a total of 3191 sound-symbolic morphemes with two or more syllables, extracted from the dictionary, were analyzed. Larsen and Heinz (2012) also used the same dictionary as Hong (2010) for their analysis. They specifically examined patterns of vowel harmony, focusing on a set of neutral vowels in Modern Korean sound-symbolic words. Given that Modern Korean has a disrupted vowel harmony system, they sought to uncover quasi-regularity by positing the existence of more neutral vowels than traditionally acknowledged ones.1 Neutral vowels are those that do not adhere to the harmonizing principle. In Korean, certain dark vowels, for instance, act as harmony-neutral in non-initial syllables, allowing both dark or light vowels in the preceding syllable (Larsen and Heinz 2012). Examples from Kwon (2018, p. 4) are provided in (3):

where “N” refers to the neutral vowel. Similar to Hong (2010), Larsen and Heinz (2012) focused their study on “reduplicant sound-symbolic forms” (p. 441) to investigate the phonotactics of vowel harmony in Korean sound-symbolic words. The dataset analyzed by Larsen and Heinz (2012) comprised 3971 forms of vowel patterns, including 2992 disyllabic forms and 980 trisyllabic forms. Their analysis provided quantitative support for the conventional understanding of [i] and [ɨ] as neutral vowels, and also suggested that [u] and [y] may function as neutral vowels. However, the inclusion of [u] and [y] as neutral vowels may be a result of the compromised state of vowel harmony in Modern Korean.

| (3) | 둥글 /tuŋkɨl/ (DN) | 동글 | /toŋkɨl/ (LN) | ‘round, involving a large vs. small circle’ |

| 늘씬 /nɨls’in/ (DN) | 날씬 | /nals’in/ (LN) | ‘thinness of a taller vs. tall thing’ |

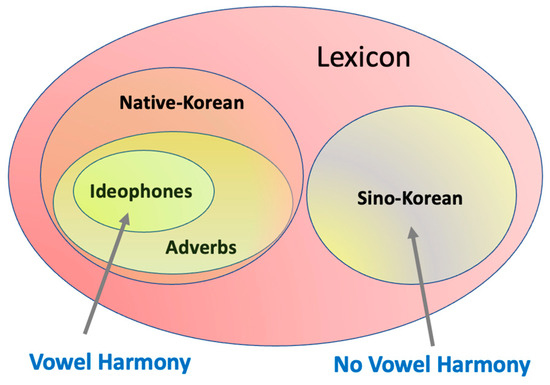

One of the reasons reduplicant ideophones are chosen for vowel harmony analysis is because the vowel harmony system is best preserved in these forms. It is widely suggested in the literature that ideophones, which are described as iconic words, exhibit distinct phonotactic patterns that differ from the regular phonotactic constraints of everyday language, emphasizing expressiveness (Kwon 2018 and references therein). Languages often employ unusual segments outside of their regular phonological inventory (Kwon 2018; Newman 2001) or arrange segments in unconventional ways as a means of expressing themselves. In Modern Korean, vowel harmony can be observed in ideophones. If ideophones demonstrate phonotactically distinct patterns from regular phonotactic constraints, it implies that vowel harmony in Modern Korean is a result of irregular phonotactics. Consequently, we would ideally expect little-to-no evidence of vowel harmony in other components of the lexicon. However, as mentioned earlier, the regular vowel harmony system in Korean has been somewhat compromised since Middle Korean (Park 1990). Therefore, the following research question arises: How harmonious are the vowels in the lexical components of ideophones compared to other parts of the lexicon, such as Sino-Korean words or adverbs? For instance, if we consider the entire lexicon, would ideophones exhibit the highest adherence to vowel harmony? If so, to what extent do ideophones within adverbs follow the vowel harmony pattern? It is possible that, as in Figure 1, the vowel harmony pattern is predominantly observed in ideophones, followed by native Korean adverbs, as they include ideophones. On the other hand, the vowel harmony pattern may not be attested in Sino-Korean vocabulary.

Figure 1.

Ideophones as a domain of vowel harmony.

To address this question, I conducted an analysis of vowel patterns by classifying vowels as positive, negative, or neutral and organizing lexical items according to their origin (native stock and Sino-Korean) and part of speech (noun and adverb). I extracted lexical items with two, four, or six syllables from the open dictionary Urimalsaem2. This extensive corpus-based study of vowel patterns in Korean aims to provide insight into the extent to which irregular phonotactics contribute to sound symbolism in Modern Korean, focusing on larger lexical components.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

This study analyzed a dataset provided by the National Institute of Korean Language (NIKL), which consists of over 1 million words (1,129,997 words, to be precise). The dataset is accessible on the NIKL website (https://opendict.korean.go.kr/main (accessed on 14 April 2022) and represents an open dictionary of Korean. Lexical entries have been contributed by anonymous users and validated by specialists before their being made available online. The dataset is distributed under a Korean Open Government License type 4, which allows it to be distributed with attribution, without derivatives, and not for commercial purposes.

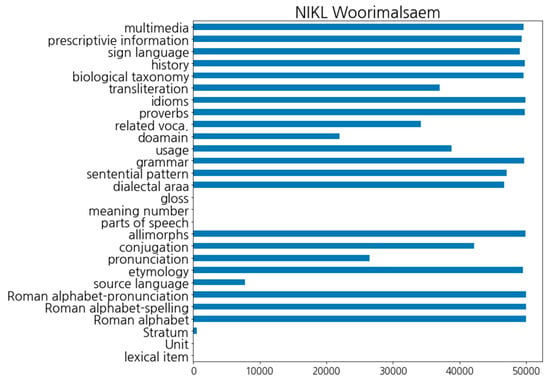

The dataset consists of 23 Excel files, each containing information for 50,000 entries, except for the last file, which contains 20,003 entries. The raw data are in MS Excel format and have a size of 187.1 MB, corresponding to 1,129,997 lexical entries. The raw data were last updated in December 2018 and are encoded in UTF-8. Each entry in the Excel spreadsheet has 27 columns, although quite a few columns have missing values or content in their entirety. Figure 2 is a bar graph that illustrates the number of missing values for each of the 27 columns listed on the y-axis.

Figure 2.

A bar graph for columns in the data frame on the y-axis and the degree of missing values on the x-axis.

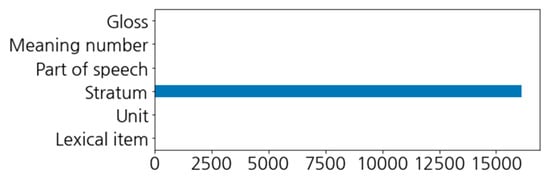

Python scripts were written to merge all the Excel files and select a subset of columns for the analysis of Korean vowel phonotactics in the dataset. The columns without bars indicate that all the necessary information is provided in those columns. Since several columns in the data frame either have missing values or are not relevant to the study’s focus, a subset of the column names was chosen. Figure 3 displays the columns of interest in the current study and the number of missing values for each column. From Figure 3, we can observe that only the “Stratum” category, which indicates whether the lexical item belongs to native Korean stock, Sino-Korean stock, or other stocks, has missing values. Specifically, there are 16,113 entries that lack information in this category, resulting in a total of 1,108,154 lexical items available for analysis (i.e., 1,124,267–16,113).

Figure 3.

Bar graphs that show the columns of interest and the number of missing values.

The Korean lexicon can be broadly divided into three strata:

- Native Korean words: Words that existed prior to any significant Chinese influence, such as words for basic concepts like body parts, natural phenomena, and verbs of daily life, as well as grammatical markers.

- Sino-Korean words: words borrowed from Chinese characters and adapted to the Korean language. These words often represent more advanced or academic concepts and names of countries, sciences, and other fields.

- Loanwords: words borrowed from other languages, such as English, Japanese, and French, especially in recent years, with the increasing globalization of Korean society.

According to the Wulimal Khun Sacen (NIKL 2000), a dictionary compiled by the Korean Language Society in 1993, there are approximately 450,000 lexical items, and these lexical items are reported to be categorized as native Korean stock (about 35%), Sino-Korean stock (approximately 60%), and borrowings (around 5%) (H.-M. Sohn 1999). In the Urimalsaem (NIKL 2019), which is used in this study, 903,333 lexical items are listed, along with their lexical stratum. Note that in Urimalsaem, a lexical item may be listed multiple times if it has multiple meanings. For the analysis, the multiple listings of each lexical item were collapsed into a single instance. Urimalsaem divides the Korean Language into native Korean stock, Sino-Korean, borrowings, and hybrid words. Table 1 provides a summary of the number of tokens and the proportion of each lexical component observed in the Urimalsaem database. It can be observed that the Sino-Korean stock makes up a larger portion of the Korean lexicon compared to the native Korean. Additionally, it is worth nothing that there are as many hybrid words as native Korean words in Urimalsaem. Hybrid words in Korean are a combination of Sino-Korean words, native Korean words, and loanwords with mixed meanings, pronunciations, and spellings. An example is “사이버범죄 [saibə bəm.tɕe]” (cyber (English) + 범죄 (犯罪; Sino-Korean); cybercrime). For the convenience of this paper, hybrid words were not analyzed.

Table 1.

Lexical Stratum in Urimalsaem.

Figure 4 is a screenshot illustrating examples of data from Urimalsaem. The columns include lexical items (‘어휘’), construction units (‘구성단위’), lexical stratum (‘고유어 여부’), parts of speech (‘품사’), number of lexical meanings (‘의미 번호’), and lexical meaning (‘뜻풀이’).

Figure 4.

A screenshot of samples taken from Urimalsaem (Open Source Korean Dictionary).

2.2. Preprocessing for Extracting Vowel Sequences

A Python script was written to extract vowel sequences from words with syllable lengths ranging from 2 to 6 and to convert them to the dark, light, and neutral vowel types. The extracted lexical items, based on this condition of syllable numbers, cover 89.6% (994,590 out of 1,108,154) of all the words in Urimalsaem. The restriction to these syllable lengths is for the efficient calculation of light and dark vowel types within words. Furthermore, only monophthongs were selected for analysis. Although the lexicon includes a large number of opening diphthongs with onglides [j] and [w], this paper disregards the harmonic classification of diphthongs in the discussion. This is because “the literature on Korean vowel harmony in sound-symbolic words does not generally discuss diphthongs”, as mentioned in Larsen and Heinz (2012)3. Additionally, the complete vowel merger in Modern Korean is taken into consideration, where [ɛ] (spelled ‘ㅔ’ and classified as dark) merges into [æ] (spelled ‘ㅐ’ and classified as light), resulting in the completed vowel merger in Korean (Kang et al. 2015).

Furthermore, based on the works of Kim-Renaud (1976) and H.-M. Sohn (1999), [i] and [ɨ] function as dark vowels in initial position but are neutral vowels that can appear following either type of vowel in non-initial positions. Considering the previous literature, this study applied the following procedures, using Python and Pandas, to each two- to six-syllable word:

- The lexical words were decomposed into consonants and vowels. The decomposed vowels were separated into a distinct list of sequences for further processing.

- The dark vowel [ɛ] ‘ㅔ’ was converted to the light vowel [æ] ‘ㅐ’.

- Monophthongal vowels in the initial syllable were classified as ‘light’ if the vowel was one of ‘ㅗ’([o]), ‘ㅏ’([a]), or ‘ㅐ’([æ]), and as ‘dark’ if the vowel was one of ‘ㅜ’([u]), ‘ㅓ’([ʌ]), ‘ㅣ’([i]), or ‘ㅡ’([ɨ]).

- Monophthongal vowels in the non-initial syllable were classified as ‘light’ if the vowel was one of ‘ㅗ’([o]), ‘ㅏ’([a]), or ‘ㅐ’([æ]), as ‘dark’ if the vowel was one of ‘ㅜ’([u]), ‘ㅓ’([ʌ]), and as ‘neutral’ if the vowel was either ‘ㅣ’([i]), or ‘ㅡ’([ɨ]).

- ‘l’([i]) and ‘ㅡ’ ([ɨ]) were treated as neutral if they appeared non-initially.

Table 2 provides a summary of the classification of monophthongal vowels into dark, light and neutral vowels based on their position in the initial and non-initial syllables.

Table 2.

Classification of monophthongal vowels into dark, light, and neutral vowels.

After classifying the monophthongal vowels into ‘dark’, ‘light’, and ‘neutral,’ the lexical items were further categorized based on factors such as the number of syllables, lexical stratum, part of speech, or ideophones if the part of speech corresponded to adverbials. As a result, the total number of lexical items analyzed was reduced from 994,590 to 716,397.

3. Results

3.1. Vowel Sequencing of the First Two Syllables in the Dataset

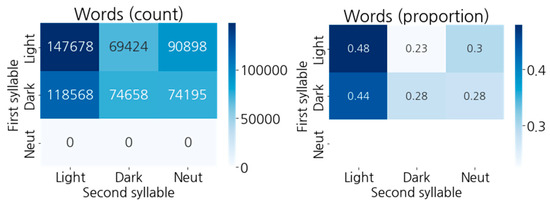

To assess the overall harmony between two adjacent vowels, we examined the heatmap representation of the initial two syllables for all the lexical items with syllable lengths ranging from two to six. Figure 5 represents the confusion matrix for the first two syllables of the analyzed lexical items, displaying the count on the left and the proportion on the right. It is worth noting that there are no words in our dataset that begin with a neutral vowel, resulting in an empty third row.

Figure 5.

Heatmap graphs for the first two syllables in the whole lexical items whose syllable lengths range from 2 to 6. The raw counts of vowel harmony types are on the left, and the proportion is given in the right-hand figure.

As shown in the figure, the light vowel is frequently followed by either another light or a neutral vowel, accounting for 48% and 30%, respectively, totaling 78%. Conversely, the likelihood of a dark vowel being followed by another dark vowel (28%) appears less probable than the probability of a dark vowel being followed by light vowel (44%). Considering neutral vowels as well, and assuming that cases of dark vowels followed by another dark vowel or a neutral vowel represent legitimate instances of vowel harmony, we observe that 56% of syllable-initial vowels exhibit legitimate vowel harmony (28% followed by dark vowels and 28% followed by neutral vowels).

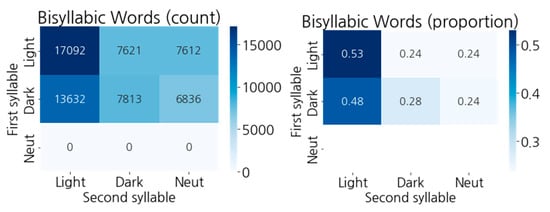

3.2. Results for Bisyllabic Words

Among the words, only bisyllabic words were extracted. These bisyllabic words consist of native Korean Stock, Sino-Korean Stock, and borrowings. To examine the patterns of vowel harmony, a heatmap was applied to the selected bisyllabic words. Figure 6 illustrates the vowel patterns in the bisyllabic words. Although minor differences are observed compared to Figure 5, the general pattern appears to be quite similar. Both light vowels and dark vowels tend to be followed by light syllables (53% for the syllable-initial light vowels vs. 48% for the syllable-initial dark vowels). Light vowels exhibit a higher occurrence of legitimate vowel harmony patterns (53% for light vowels and 24% for neutral vowel) compared to dark vowels (28% for dark vowels and 24% for neutral vowels).

Figure 6.

Heatmap graphs for the first two syllables in the bisyllabic words. The raw counts of vowel harmony types are on the left, and the proportion is given in the right-hand figure.

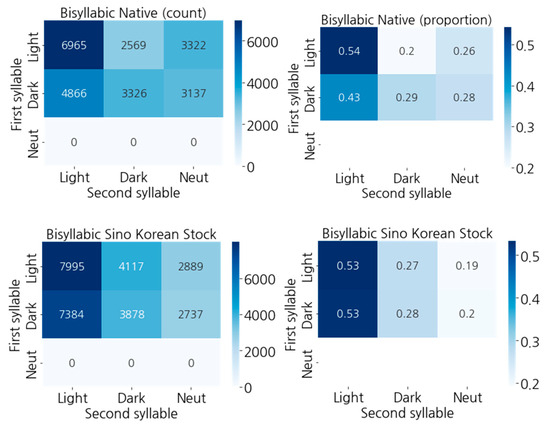

3.3. Native and Sino-Korean Vocabulary Stock

The lexical items are categorized based on the lexical stratum. According to the literature on vowel harmony, there is no preference for the choice of the second vowel type in both native Korean words and Sino-Korean words. If this is the case, we would expect to see a similar distribution of vowels for the first and second syllables.

For bisyllabic native Korean words, the dark vowel is followed by a light vowel 54% of the time, while it is followed by another dark vowel only 43% of the time, as shown in Figure 7. Similarly, for bisyllabic Sino-Korean words, we observe a similar pattern, with 53% of the light vowels being followed by other light vowels, and 53% of the dark vowels being followed by the same type of dark vowels.

Figure 7.

Heatmap graphs for the first two syllables in the bisyllabic native Korean words (top panel) and Sino-Korean words (bottom). The raw counts of vowel harmony types are on the left, and the proportion is given in the right-hand figure.

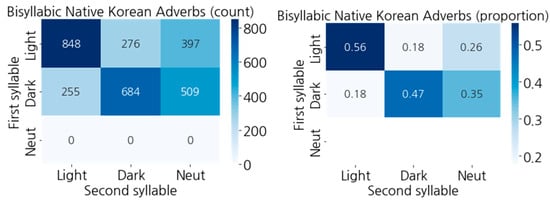

3.4. Bisyllabic Native Korean Adverbs

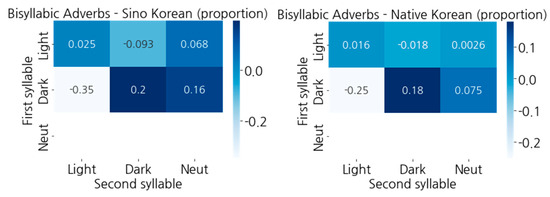

During the corpus analysis, we identified 2969 instances of bisyllabic native Korean adverbs. In comparison to other parts of speech, adverbs exhibit a pronounced preference for vowel harmony, which aligns with our expectations considering the inclusion of ideophones within this category. Specifically, as in Figure 8, light vowels are followed by other light vowels 56% of the time and by neutral vowels 26% of the time, making up a total of 82% of the data. Conversely, dark vowels are followed by other dark vowels 47% of the time and by neutral vowels 35% of the time, also accounting for 82% of the dataset. In Figure 9, the difference is shown between bisyllabic native Korean adverbs and bisyllabic Sino-Korean words. The vowel harmony pattern inherent in the native Korean adverbs makes the harmonious patterns more positive than the counterparts.

Figure 8.

Heatmap graphs for the first two syllables in the bisyllabic native Korean adverbs. The raw counts of vowel harmony types are on the left, and the proportion is given in the right-hand figure.

Figure 9.

The difference between bisyllabic native Korean adverbs and bisyllabic Sino-Korean words. The raw difference counts of vowel harmony types are on the left, and the difference proportion is given on the right.

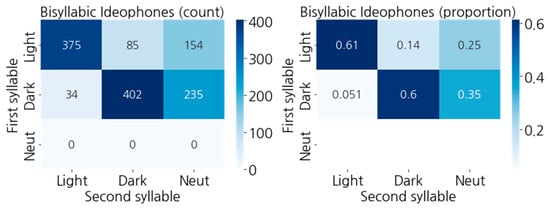

3.5. Bisyllabic Ideophones4

To focus specifically on contexts where vowel harmony is expected to be prominent, we extracted ideophones from the set of native Korean adverbs. Ideophones were identified by selecting adverbs whose meaning description ends with the description of sounds or manners. During the corpus analysis, we identified 1285 instances of bisyllabic ideophones. The two vowels in the syllabic nucleus were categorized as light, dark, or neutral. The findings as shown in Figure 10 revealed that 96% of the dark vowels were followed by the same type or a neutral vowel, demonstrating a high degree of vowel harmony productivity. In the case of the light vowel in the first syllable, 61% were followed by another light vowel, while 25% were followed by neutral vowels. For the dark vowel in the first syllable, 60% were followed by another dark vowel, and 35% were followed by neutral vowels. Consequently, despite some deviations in the vowel system, it can be confidently stated that bisyllabic ideophones exhibit a vowel harmony pattern. Unlike previous cases, the heatmap analysis shows a higher prevalence of vowel harmony patterns along the diagonal line, surpassing the average observed proportions.

Figure 10.

The difference between bisyllabic ideophones. The raw difference counts of vowel harmony types are on the left, and the proportion in difference is given on the right.

When comparing the vowel harmony patterns of bisyllabic Korean adverbs and ideophones, as in Figure 11, we can observe a 5% increase in light–light sequences and a 13% increase in dark–dark sequences in ideophones.

Figure 11.

The difference between bisyllabic ideophones and adverbs is shown in the left-hand figure, while the right-hand figure shows the top 5 V-V sequences of sound-symbolic bisyllabic words. In the figure on the right, eo on the y-axis corresponds to [ʌ].

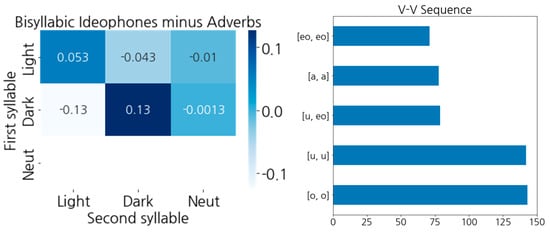

3.6. Results for Trisyllabic Ideophones

Examples of trisyllabic ideophones are listed below in Table 3:

Table 3.

Examples of the trisyllabic ideophones.

The heatmaps in the upper panel in Figure 12 display the vowel sequencing of the first two syllables of trisyllabic ideophones, while the heatmaps in the lower panel in Figure 12 show the sequencing of the last two syllables. We observe fewer instances of vowel harmony in the first two syllables compared to the last two syllables. When we focus on the harmonious cases excluding neutral vowels, we find that the second and third syllables exhibit more harmonious patterns (37% for the light–light sequence and 88% for the dark–dark sequence) compared to the first and second syllables (44% for the light–light sequence and 75% for the dark–dark sequence). As a side note, examples like ‘hudadak’ (후다닥; D-L-L) help us understand why the second and third vowels tend to form more harmonious sequences than the first and second vowels.

Figure 12.

Heatmap graphs for the first two syllables (top) and the last two (bottom) in the trisyllabic ideophones. The raw counts of vowel harmony types are on the left, and the proportion is given on the right.

The frequently observed sequences of vowel types as follows: the most common sequence of vowels is [a, a, a] (light–light–light), followed by [eo [ʌ], eo[ʌ], eo[ʌ]] (dark–dark–dark). Another commonly observed vowel harmony sequence is [a, ɨ, ɨ] (light–neut–neut). It is worth noting that none of the instances of the top most frequent vowel sequence violate the harmonic vowel patterns.

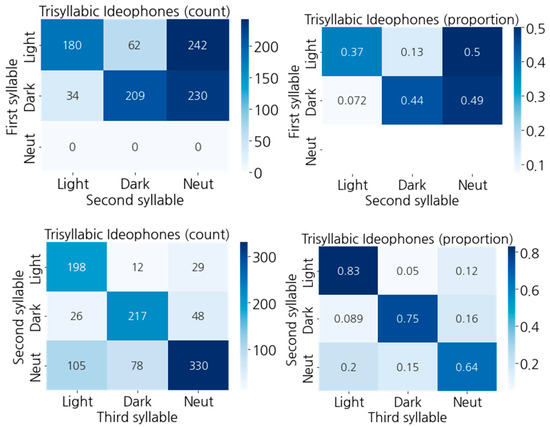

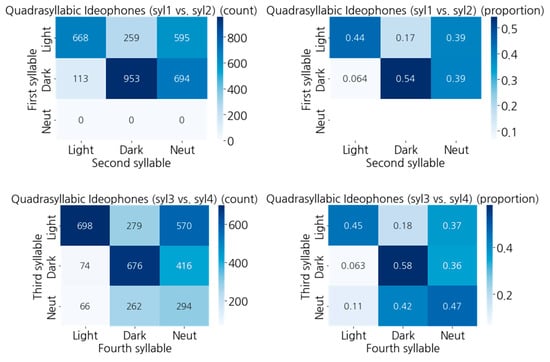

3.7. Results for Quadrisyllabic Ideophones

A total of 3344 sound-symbolic quadrisyllabic words were examined to analyze the regularity of sound-symbolic patterns. The majority of quadrisyllabic ideophones are formed through the word formation process of reduplication. Below in Table 4 are some examples of quadrisyllabic ideophones.

Table 4.

Examples of the quadrisyllabic ideophones.

The first two vowel patterns exhibit highly harmonious patterns (83% for the light–light and light–neutral patterns and 93% for the dark–dark and dark–neutral patterns), as shown in Figure 13 below. The last two syllables also exhibit highly harmonious patterns (82% for the light–light and light–neutral sequences and 94% for the dark–dark and dark–neutral pattern), as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Heatmap graphs for the first two syllables (top) and the last two (bottom) in the quadrisyllabic ideophones. The raw counts of vowel harmony types are on the left, and the proportion is given on the right.

Although quadrisyllabic ideophones are often reduplicative forms of bisyllabic ideophones, following the harmonic vowel sequence, there are instances where the vowel harmony patterns are violated. For example, in cases like 얼룩달룩 [ʌ u a u], the first two vowels adhere to the dark–dark pattern, conforming to the vowel harmony rule. However, the last two syllables exhibit a light–dark sequence, which goes against the vowel harmony pattern. From the figures in the lower panel in Figure 13, we can infer the number of these so-called corrupt cases of vowel harmony.

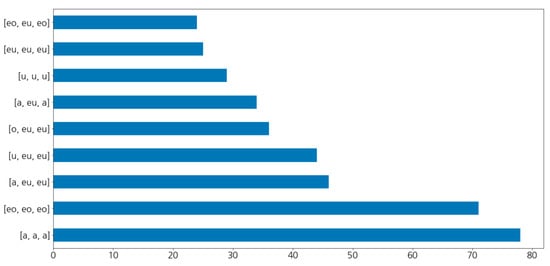

Figure 14 represents a bar graph depicting the top 10 most frequently observed vowel sequences. The sequences [a, a, a, a] and [u, u, u, u] involve the repetition of the same vowel types. The remaining sequences exhibit repetition of the first two syllables, indicating that total reduplication of the bisyllabic vowels is the most common type of vowel sequence in quadrisyllabic ideophones.

Figure 14.

The most frequently observed quadrisyllabic vowel sequences (n = 10). In the figure, eo corresponds to [ʌ] and eu to [ɨ].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper examined the vowel harmony of the Korean lexicon from a broader perspective, that is, by analyzing the patterns of vowel harmony in different lexical strata including Sino-Korean stock, native stock, and adverbs or ideophones within the native Korean stock. Previous studies have suggested that canonical iconic words such as ideophones have distinct phonotactic distributions that set them apart from ordinary vocabulary (Dingemanse 2012; Kwon 2018). For instance, ideophones in languages such as Hausa exhibit word-final obstruents, while most native Hausa words are either vowel- or sonorant-final (Newman 2001). Ideophones in Kisi demonstrate vowel harmony, whereas other lexical classes in that language lacks this harmonic pattern (Childs 1988). In Korean, ideophones exhibit stem-internal vowel harmony, which is absent in the prosaic lexicon (Kwon 2018).

Despite claims of skewed phonotactic distribution, the previous literature has not thoroughly investigated the degree of skewness in the phonotactic distribution of canonical iconic words compared to other parts of the lexicon. Therefore, it is necessary to examine whether the harmonic pattern of vowels observed in ideophones truly distinguishes them from ordinary vocabulary. Currently, no studies have directly compared the harmonic patterns of vowels in ideophones with those in other lexical components, such as Sino-Korean words, to confirm this distinction. Indeed, some studies have proposed the existence of neutral vowels to impose a more harmonious structure on vowel patterns in ideophones (Larsen and Heinz 2012; Kwon 2018; Kim and Nam 2019), presumably based on the assumption that the Korean lexical items strive to maximize the degree of vowel harmony, even by treating certain vowels that have been conventionally treated as non-neutral vowels as neutral. However, it remains unclear whether these newly recognized so-called neutral vowels are genuinely neutral. It is possible that the corruption of dark and light vowels is more prevalent in Modern Korean, and the notion of neutral vowels serve as a metric for quantifying the extent of vowel harmony corruption.

In order to examine whether ideophones exhibit a phonotactically skewed distribution compared to prosaic vocabulary, I conducted an analysis of an online Korean dictionary. The analysis took into account the lexical stratum, part of speech, and the status of ideophones. Monophthongs in words consisting of two to six syllables were categorized as dark, light, and neutral vowels, based on their position within the word. Regarding neutrality, within the ideophone harmony system, legitimate violations of the harmony rule only occur with the presence of ‘neutral’ vowels. Some dark vowels function as harmony-neutral in non-initial syllables, allowing either dark or light vowels in the preceding syllable. Forms that contain a combination of dark and light vowels within a morpheme are considered violations of the vowel harmony system in Korean. The analysis confirmed the presence of harmonious vowel patterns in adverbs, particularly those adverbs whose semantic meanings are ideophones. However, harmonic vowel patterns of ideophones are corrupt to some extent, as expected, due to historical sound changes and borrowings from other languages such as Chinese and English. The approach adopted in this paper is helpful, in that it enables us to quantify the degree of corruption in the vowel harmony system for different lexical components.

These data are valuable for researchers studying vowel sequences within words, vowel harmony systems, and sound symbolism. They can be utilized to investigate the strength of vowel harmony in sound-symbolic words from a phonotactic perspective, offering valuable insights for researchers in the field. Moreover, the findings obtained from the data have sparked unexpected curiosities. For example, in trisyllabic native Korean adverbs, we observed that the vowel harmony is more evident in the second and third syllables compared to the first and second syllables. Future studies may help us unravel the reasons behind this phenomenon, such as why trisyllabic ideophones exhibit more harmonic vowel patterns in the second and third syllables. Additionally, it would be interesting to explore whether native speakers of Korean perceive the second and third syllables as more harmonious than the first and second syllables in trisyllabic ideophones.

Funding

This research was supported by the Sungshin Women’s University Research Grant of 2020 and by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korean and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2021S1A5A2A03064795).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Urimalsame, which is the basis of the data used in this paper can be found at https://opendict.korean.go.kr/main (accessed on 14 April 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Neutral vowels refer to vowels that exhibit “dual functionality” in terms of vowel alternations (Hayes and Londe 2006; Hayes et al. 2009; Larsen and Heinz 2012). Neutral vowels in Korean undergo vowel harmony alternations in initial syllables, but not in non-initial syllable positions. For example, note that the neutral vowel [i] is not affected by the harmony process in [pusilʌk] ‘rusling’ and [posilak] ‘rustling (of a different type)’. Which vowels belong to the neutral vowel category in the Korean vowel harmony system has been controversial. According to Larsen and Heinz (2012), the dark /u/ in non-initial syllables also frequently follows light vowels. Although /u/ occurs with light vowels proportionally less than the traditional neutral vowels, Larsen and Heinz claimed that it follows closely the patterns of the neutral vowel and that it is, therefore, at least partially neutral. In a similar vein, /a/ is claimed to have a partial trait of neutrality, even though /a/ is harmonic to a greater extent than the traditional neutral vowels. Kwon (2018) treats /u/ as a neutral vowel but /a/ as a light vowel. Kim and Nam (2019) could not find convincing evidence of /a/ as a neutral vowel. Thus, neutral vowels in this paper are restricted to the traditional neutral vowels /i/ and /ɨ/. |

| 2 | Urimalsaem is “an innovative Korean language dictionary in which users collaboratively add words and their meanings, and modify the content directly from the web browser”(https://opendict.korean.go.kr/main (accessed on 14 April 2022)). |

| 3 | Larsen and Heinz (2012) observed that although the data is sparse, diphthongs in the initial syllable pattern with their nuclei and diphthongs in the non-initial position do not appear to pattern their nuclei. |

| 4 | In some research on Korean ideophones, cross-modal ideophones are further sub-classified into phenomimes and psychomimes. Since psychological states can be associated with the state or property of objects, some researchers opt to combine phenomimes and psychomimes into the category of ‘cross-modal ideophones’ instead of ‘onomatopoeic ideophones.’ Nevertheless, the practicality of this traditional dichotomous classification is questionable, because numerous Korean ideophones express multisensory experiences that defy the semantic boundaries of the two categories (Kwon 2018, p. 6). Considering the challenges involved in establishing a clear semantic classification boundary for ideophones, this paper treats these categories under the umbrella term ideophones. |

References

- Ahn, Sang-Cheol, and Chin-Woo Kim. 1985. Vowel harmony in Korean: A multi-tiered and lexical approach. In In Memory of Roman Jokobson: Papers from the 1984 MALC. Edited by Gilbert Youmans and Donald Lance. Columbia: Linguistic Area Program. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, G. Tucker. 1988. The phonology of Kisi ideophones. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 10: 165–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Mi-Hui. 1994. Vowel Harmony in Korean: A Grounded Phonology Approach. Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Chin Wan. 2000. An optimality-theoretic account of vowel harmony in Korean ideophones. Studies in Phonetics, Phonology and Morphology 6: 431–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dingemanse, Mark. 2012. Advances in the cross-linguistic study of ideophones. Language and Linguistics Compass 6: 654–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, Sara. 2006. Vowel harmony in Korean and morpheme correspondence. Harvard Studies in Korean Linguistics 11: 131–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori, Shiro. 1982. Vowel harmonies of the Altaic languages, Korean, and Japanese. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 36: 207–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Bruce, and Zsuzsa Cziráky Londe. 2006. Stochastic phonological knowledge: The case of Hungarian vowel harmony. Phonology 23: 59–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Bruce, Péter Siptár, Kie Zuraw, and Zsuzsa Londe. 2009. Natural and unnatural constraints in Hungarian vowel harmony. Language 85: 822–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Sung-Hoon. 2008. Variation and exceptions in the vowel harmony of Korean suffixes. The Journal of Studies in Language 24: 405–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Sung-Hoon. 2010. Gradient vowel cooccurrence restrictions in mono- morphemic native Korean roots. Studies in Phonetics, Phonology and Morphology 16: 279–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Yoonjung, Tae-Jin Yoon, and Sungwoo Han. 2015. Frequency effects on the vowel length merger in Seoul Korean. Laboratory Phonology 6: 469–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, Shigeto. 2020. Sound symbolism and theoretical phonology. Language and Linguistics Compass 14: e12372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sun-Hoi, and Sunghyun Nam. 2019. Revisiting vowel harmony in Korean sound-symbolic words: A corpus-based quantitative approach. The Journal of Studies in Languages 35: 309–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Renaud, Young-Key. 1976. Semantic features in phonology: Evidence from vowel harmony in Korean. CLS 12: 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Seongyeon. 2010. A contrastivist view on the evolution of the Korean vowel system. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 61: 181–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, Chung-Ku. 2003. The vowel system of contemporary Korean and direction of change. Kwukehak 41: 59–91. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Nahyun. 2015. The Natural Motivation of Sound Symbolism. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Austrailia. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Nahyun. 2018. Iconicity Correlated with Vowel Harmony in Korean Ideophones. Laboratory Phonology 9: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Darrell, and Jeffrey Heinz. 2012. Neutral vowels in sound-symbolic vowel harmony in Korean. Phonology 29: 433–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jin-Seong. 1992. Phonology and Sound Symbolism of Korean Ideophones. Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Ki-Moon, and S. Robert Ramsey. 2011. A History of the Korean Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sang-Oak. 1984. An overview of issues in the vowel system and vowel harmony of Korean: Disharmony among the hypotheses of vowel harmony. Eohak Yeongu [Language Research] 20: 417–51. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of the Korean Language (NIKL). 2000. Compilation Guidelines for the Great Standard Korean Dictionary II. Available online: http://www.korean.go.kr/front/reportData/reportDataView.do?report_seq=56&mn_id=45 (accessed on 26 December 2017).

- National Institute of the Korean Language (NIKL). 2019. Urimalsaem. Available online: https://opendict.korean.go.kr/main (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Newman, Paul. 2001. Are ideophones really as weird and extra-systematic as linguists make them out to be? In Ideophones. Edited by F. K. Erhard Voeltz and Cristina Killian-Hatz. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 251–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Sang-Suk. 1998. The Korean vowel shift revisited. Language Research 34: 445–63. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Sayhyon. 1990. Vowel harmony in Korean. Eohak Yeongu [Language Research] 26: 469–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, Ho-Min. 1999. The Korean Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, Hyang-Sook. 1986. Toward an integrated theory of morphophonology: Vowel harmony in Korean. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences 16: 157–84. [Google Scholar]

- van der Hulst, H., and J. van de Weijer. 1995. Vowel harmony. In The Handbook of Phonological Theory, 1st ed. Edited by John Goldsmith. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 495–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).