Ver-Based Evidential Re/Positioning Strategies in Conservative Digital Newspaper Readers’ Comments on Controversial Immigration Policies in Spanish

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Re/Positioning Discourse on Immigration: Spain and Europe

3. Theoretical Background

3.1. Evidential Perception

- Type I: Perception Verb (PV) + Finite Complement Clause (FCC);

- Type II: PV + WH-Complement Clause;

- Type III: PV + Direct Object (DO) + Non-Finite Verb (NFV);

- Type IV: PV + Prepositional Phrase (PP);

- Type V: PV + Adjective (ADJ);

- Type VI: PV + Conjunction (CONJ) + Clause (C);

- Type VII: PV + Infinitive Copula (IC) + ADJ or Noun (N) or ADJ + N;

- Type VIII: Parentheticals;

- Type IX: Perception Verb External to the Clause.

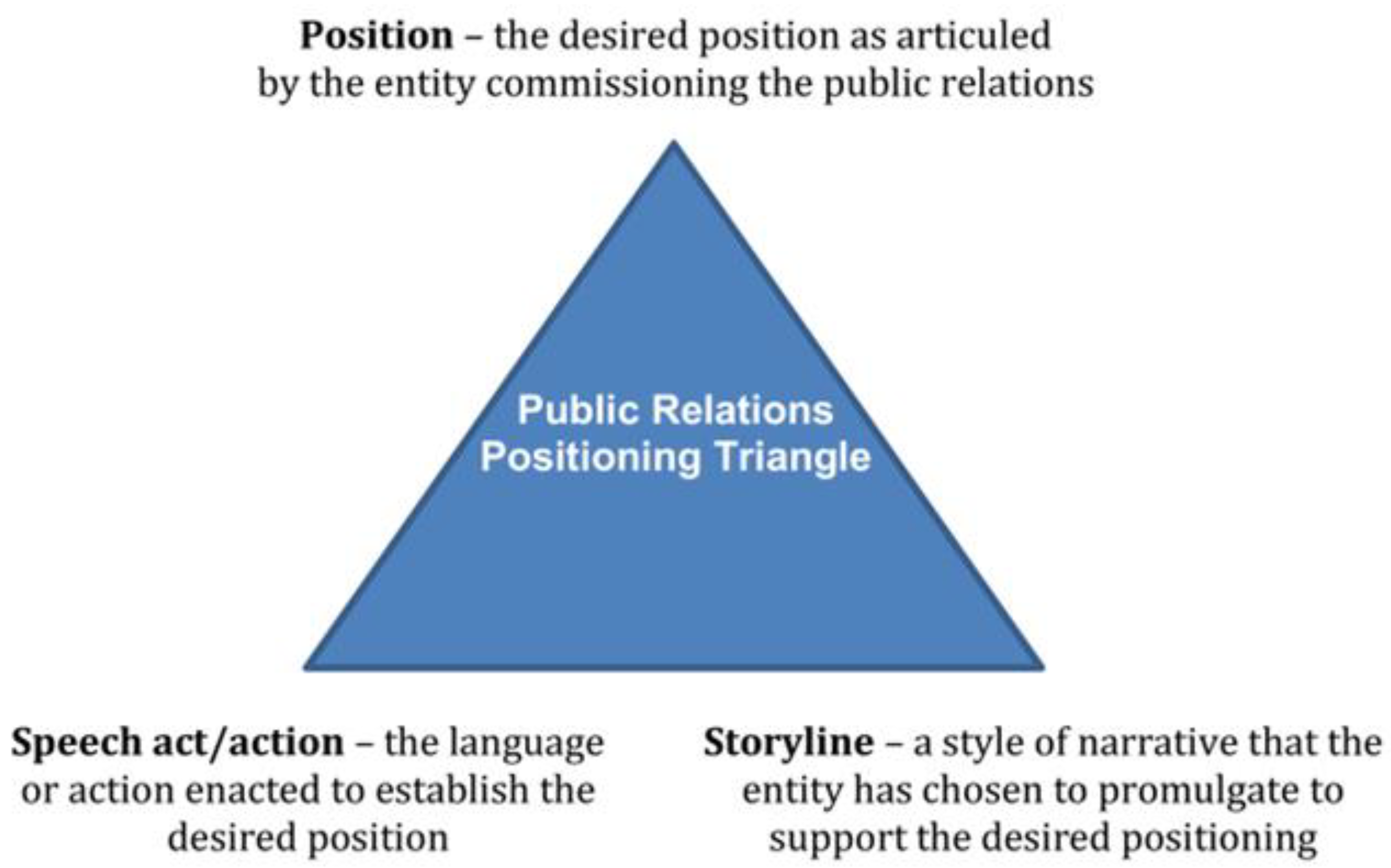

3.2. Positioning

3.3. Computer-Mediated Dialogicity

4. Aims, Corpus Description, and Methodology

- To identify and analyze the expressions of ver-based evidential positioning and repositioning strategies used by conservative Spanish readers in digital newspapers regarding the Spanish government's unexpected reception of the Aquarius vessel, carrying 630 immigrants and refugees, in June 2018, as well as their subsequent refusal to host the Open Arms vessel, which had 150 immigrants and refugees on board, in August 2019.

- To perform a content-based analysis of the viewpoints expressed by conservative Spanish readers through the use of ver-based evidential positioning and repositioning strategies, as identified in the case of both the Aquarius and the Open Arms events. The analysis will focus on examining the content and nature of these viewpoints.

- STAGE 1: Identification and classification of all the evidential markers of visual perception retrieved from the corpus (Aikhenvald 2018; Marco 2016; Kotwica 2015, 2017; Anderson 1986; Boye 2010; Hassler 2010; and Whitt 2010).

- STAGE 2: Content-based analysis of newspaper readers’ acts of positioning and repositioning involving their use of evidential markers of visual perception (Davies and Harré 1991; Harré and Van Langenhove 1999a, 1999b; Harré et al. 2009; Moghaddam and Harré 2010; and Harré and Moghaddam 2012).

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Stage 1

- Impersonal—Inference.

- Se ve que no es solución sino artificio y chapuza; la ayuda hay que prestarla enseñándoles a organizar sus países, con sus propias gentes y recursos, que tienen muchos pero pésimamente gestionados. (ABC).[It is seen/can be seen that this is not a complete solution but a half-way, botched one.]

- 2.

- Se ve que tienen dinero para salir (LR).[It can be seen that they have the money to go out.]

- Impersonal—Report.

- 3.

- ¿Alguien sabe por casualidad lo que nos va a costar en Euros el show de hoy…? porque asi, por lo que se ve, nos va a salir mas caro que el Desembarco de Normandia. (ABC).[… because like this, as we can see/it can be seen, this will cost more than the “Normandy Landing”.]

- First-person—Reasoning-based inference.

- 4.

- Yo veo clarísimamente el abismo al final del trayecto. (ABC).[I see very clearly the abyss at the end of the journey.]

- First-person—Perception-based inference.

- 5.

- Vaya, veo que no dominas muy bien la lectura, pues a mi sin comas ni acentos, ni puntos. (LR).[Oh! I can see that you are not very literate… no commas, accents or full stops.]

- First-person—Evaluation.

- 6.

- Con respecto a las ONGs veo injusto que diga que colaboran. (LR).[Regarding NGOs, I see it as unfair to say that they collaborate.]

5.2. Stage 2

5.2.1. ABC

- 7.

- No, lo que se ve es la calaña de Sánchez. Todo le vale para su negocio.[No, what it is seen/one can see is Sánchez’s true nature. Anything works for him.]

- 8.

- ¿Alguien sabe por casualidad lo que nos va a costar en Euros el show de hoy…? por que asi, por lo que se ve, nos va a salir mas caro que el Desembarco de Normandia.[… because like this, as it is/can be seen, this will cost more than the “Normandy Landing”.]

- 9.

- En mi casa somos tres y entran 1000 € al mes y 500 € se van para el alquiler del piso, y con el resto paga luz, agua, comida, gas, ropa… gasolina no, porque no me puedo permitir tener coche (ya quisiera yo tener uno, aunque fuera mas pequeño que alguno de los que veo que llevan ellos en muchas ocasiones…[In my house there are three of us and we earn €1000 a month and €500 are for the rent, and the rest is for electricity, water, food, gas, clothing… not petrol, because I cannot afford to have a car (but I would not mind having one, even if it were smaller than some of the ones that very often I see that they drive on many occasions…]

- PEDRO SÁNCHEZ IS IRRESPONSIBLE, SEEKING PERSONAL INTEREST;

- THE STATE IS THE GUARDIAN, WITH OBLIGATION TO PROTECT SPAIN FROM IMMIGRANTS. RESPONSIBILITY vs. SOLIDARITY;

- IMMIGRANTS ARE STATE ABUSERS WITH NO RIGHT TO THE SOLIDARITY OF THE SPANISH GOVERNMENT;

- EXPAND THE POSITION THAT THE STATE IS THE GUARDIAN, WITH THE RIGHT NOT TO WELCOME ABUSIVE IMMIGRANTS.

- 10.

- Pues yo que estoy en contra de este gobierno veo perfecto este bloqueo.[Well, though I am really against this government, I see this blockade as perfect…]

- 11.

- Cuando voy al medico y veo que el consultorio está lleno de inmigrantes.[When I go to the doctor’s and I see that the surgery is full of immigrants.]

- 12.

- Será el negocio que hacen las ONG rescatando gente, en el programa de Salvados se veia que recibian la llamada por móvil, recogían a inmigrantes que se jugaban la vida, y dejaban a la deriva la embarcación con el motor que volvían a recoger los traficantes de personas.[That must be the NGOs’ business when rescuing people, in Salvados it could be seen/one could see that they received a mobile call, they picked up the immigrants who were risking their lives, and they left the boat drifting with the engine for the human traffickers.]

- THE STATE IS THE GUARDIAN, WITH THE OBLIGATION TO PROTECT SPAIN FROM IMMIGRANTS. RESPONSIBILITY vs. SOLIDARITY;

- IMMIGRANTS ARE STATE ABUSERS WITH NO RIGHT TO THE SOLIDARITY OF THE SPANISH GOVERNMENT;

- EXPAND THE POSITION THAT THE STATE IS THE GUARDIAN, WITH THE RIGHT NOT TO WELCOME ABUSIVE IMMIGRANTS;

- NGOs ARE HUMAN TRAFFICKING MAFIAS WITH NO SOLIDARITY PURPOSE.

5.2.2. LA RAZÓN

- 13.

- España es el país más solidario de Europa por eso se convertirá en el hogar de los refugiados que no son aceptados en Europa…, se ve que Rajoy no los recibiría nunca porque son unos insolidarios. en cambio, Sánchez sí que es solidario él y todo su equipo de gobierno.[… it can be seen/one can see that Rajoy would never welcome them because they are unsupportive to the cause.]

- 14.

- El titular es totalmente falso. Hay imágenes donde se ve que los inmigrantes, antes de bajar del barco, cantan y aplauden de alegría. Es imposible estar en shock.[The headline is totally false. There are images where it can be seen/one can see that the immigrants, before they get off the boat, are singing and applauding with joy. They cannot be in shock.]

- 15.

- Veo todos los días que hay africanos que no trabajan, con buena ropa, buenas zapatillas, aseados, con buenas colonias, con buenos móviles y auriculares, de paseo. Que no nos engañen, porque 50 € a la semana no reciben.[Every day, I can see that there are Africans who don’t work, in good clothes, good shoes, clean, wearing good colognes, with good phones and headphones, walking in the streets.]

- 16.

- Con respecto a las ONGs veo injusto que diga que colaboran. Las ONGs están ahí para salvar a la gente, no van de costa a costa trasladando personas. El viaje se inicia en embarcaciones en mal estado, y cuando el motor se para… aparecen las ONGs. En este sentido deberían de ser los gobiernos y no las ONGs las que se encargasen de esto.[Regarding NGOs, I see/find it unfair that you say that they cooperate.]

- 17.

- …. soluciones que yo veo: por ejemplo quitar las ayudas desde el estado a las ongs, porque posiblemente alguna de ellas puede estar implicada en las mafias de trafico humano.[… solutions that I see: for example, removing the aids from the state to the NGOs, because some of them may be possibly involved in human trafficking mafias.]

- STATE IS THE GUARDIAN WITH OBLIGATION TO PROTECT SPAIN FROM IMMIGRANTS. RESPONSIBILITY vs. SOLIDARITY;

- EXPAND THE POSITION THAT THE STATE IS THE GUARDIAN WITH RIGHT NOT TO WELCOME ABUSIVE IMMIGRANTS;

- IMMIGRANTS ARE STATE ABUSERS WITH NO RIGHT TO THE SOLIDARITY OF THE SPANISH GOVERNMENT;

- NGOs ARE HUMAN TRAFFICKING MAFIAS WITH NO SOLIDARITY PURPOSE;

- EXPAND THE POSITION THAT IMMIGRANTS ARE STATE ABUSERS WITH NO RIGHT TO THE SOLIDARITY OF THE SPANISH GOVERNMENT.

- 18.

- Hay un video demoledor en el que se ve los movimientos de vuestros BARCOS NEGREROS yendo a por cargas a la costa africana y trayendolos 500 millas o mas hasta europa.[There is a devastating video in which it can be seen/one can see your SLAVE BOATS going to the African coast for cargoes and taking them 500 miles or more to Europe.]

- 19.

- Y vemos a nuestro lado conciudadanos pasandolo fatal y NO reciben ayuda alguna de las instituciones. Esto se tiene que acabar.[And we see our own people having a really rough time and NOT receiving any assistance from the institutions. This cannot go on.]

- EXPAND THE POSITION THAT NGOs ARE HUMAN TRAFFICKING MAFIAS WITH NO SOLIDARITY PURPOSE;

- EXPAND THE POSITION THAT IMMIGRANTS ARE STATE ABUSERS TO THE DETRIMENT OF SPANISH CITIZENS, WITH NO RIGHT TO THE SOLIDARITY OF THE SPANISH GOVERNMENT.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2003. Evidentiality in typological perspective. Studies in Evidentiality 1: 31. [Google Scholar]

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2004. Evidentiality. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2018. Evidentiality and Language Contact. The Oxford Handbook of Evidentiality. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Lloyd B. 1986. Evidentials, paths of change, and mental maps: Typologically regular asymmetries. In Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology. Edited by Wallace L. Chafe and Johanna Nichols. Norwood: Ablex, pp. 273–312. [Google Scholar]

- Arcila-Calderón, Carlos, Patricia Sanchez-Holgado, David Blanco-Herrero, and Javier J. Amores. 2022. Hate Speech and Social Acceptance of Migrants in Europe: Analysis of Tweets with Geolocation. Comunicar: Media Education Research Journal 30: 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Sarah. 2017. Audience anticipation, expectation and engagement in lost in London live. Participations 14: 697–713. [Google Scholar]

- Badarneh, Muhammad A., and Fathi Migdadi. 2018. Acts of positioning in online reader comments on Jordanian news websites. Language & Communication 58: 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Alex, and Tobias Buck. 2018. Merkel warns that EU is at threat from impasse over asylum. Financial Times, June 6. [Google Scholar]

- Bašić, Ivana. 2020. Verbs of visual perception as evidentials in research article texts in English and Croatian. In Academic Writing from Cross-Cultural Perspectives: Exploring the Synergies and Interactions. Ljubljana: Ljubljana University Press, Faculty of Arts, pp. 196–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bobkina, Jelena, and Elena Domínguez Romero. 2020. Exploring the perceived benefits of self-produced videos for developing oracy skills in digital media environments. Computer Assisted Language Learning 35: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobkina, Jelena, Elena Domínguez Romero, and María José Gómez Ortiz. 2020. FEducational Mini-Videos as Teaching and Learning Tools for Improving Oral Competence in EFL/ESL University Students. Teaching English with Technology 20: 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bobkina, Jelena, Elena Domínguez Romero, and María José Gómez Ortiz. 2023. Kinesic communication in traditional and digital contexts: An exploratory study of ESP undergraduate students. System 115: 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, Kasper. 2010. Evidence for what? Evidentiality and scope. STUF-Language Typology and Universals 63: 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, Kasper. 2012. Epistemic Meaning: A Crosslinguistic and Functional-Cognitive Study. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Chafe, Wallace L., and Johanna Nichols, eds. 1986. Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology. Norwood: Ablex Publishing Corporation, vol. 20, pp. 261–312. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Bronwyn, and Rom Harré. 1991. Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 20: 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, Ferdinand. 1999. Evidentiality and epistemic modality: Setting boundaries. Southwest Journal of Linguistics 18: 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Diewald, Gabriele, and Elena Smirnova, eds. 2010. Linguistic Realization of Evidentiality in European Languages. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez Romero, Elena. 2016. Object-oriented perception: Towards a contrastive approach to evidentiality in media discourse. Kalbotyra 69: 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Romero, Elena. 2020. Reframing (inner) terror: A digital discourse-based approach to evidential repositioning of reader reactions towards visual reframing. Profesional de la Información 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Romero, Elena. 2022. Reportive evidentiality. A perception-based complement approach to digital discourse in Spanish and English. Journal of Pragmatics 201: 134–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Romero, Elena, and Jelena Bobkina. 2021. Exploring the perceived benefits and drawbacks of using multimodal learning objects in pre-service English teacher inverted instruction. Education and Information Technologies 26: 2961–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Romero, Elena, and Victoria Martín de la Rosa. 2017. Experimental and cognitive ‘see/ver’domain overlap in English and Spanish journalistic discourse. In Evidentiality and Modality in European Languages. Edited by Juana I. Marín-Arrese, Julia Lavid-López, Marta Carretero, Elena Domínguez Romero, María Pérez Blanco and Ma Victoria Martín de la Rosa. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 111–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbuz, Seyma N. 2019. Xenophobia: Biggest threat to Europe’s future. Daila Sabah, December 6. [Google Scholar]

- Harré, Rom. 2005. Positioning and the discursive construction of categories. Psychopathology 38: 185–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harré, Rom. 2012. Positioning theory: Moral dimensions of social-cultural psychology. In The Oxford Handbook of Culture and Psychology. Edited by Jaan Valsiner. New York: Oxford University, pp. 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Harré, Rom, and Fathali Moghaddam. 2015. Positioning Theory and Social Representations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harré, Rom, and Fathali Moghaddam, eds. 2012. Psychology for the Third Millennium: Integrating Cultural and Neuroscience Perspectives. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Harré, Rom, and Luk Van Langenhove. 1999a. Introducing Positioning Theory. In Positioning Theory: Moral Contexts of Intentional Action. Edited by Rom Hareé and Luk Van Langenhove. Basil: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., pp. 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Harré, Rom, and Luk Van Langenhove. 1999b. Positioning Theory: Moral Contexts of Intentional Action. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Harré, Rom, Fathali M. Moghaddam, Tracey Pilkerton Cairnie, Daniel Rothbart, and Steven R. Sabat. 2009. Recent advances in positioning theory. Theory and Psychology 19: 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassler, Gerda. 2010. Epistemic modality and evidentiality and their determination on a deictic basis. In Modality and Mood in Romance. Modal Interpretation, Mood Selection, and Mood Alternation. Edited by Martin G. Becker and Eva-Maria Remberger. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Herring, Susan C., and Jannis Androutsopoulos. 2015. Computer-mediated discourse 2.0. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 127–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen, Pasi. 2016. Positioning theory and small-group interaction: Social and task positioning in the context of joint decision-making. Sage Open 6: 2158244016655584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Sam. 2018a. Aquarius migrants arrive in Spain after rough week at sea. The Guardian, June 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Sam. 2018b. Unilateralism not the answer to migrant crisis, says Spain’s PM. The Guardian, June 28. [Google Scholar]

- Kitade, Keiko. 2012. Pragmatics of asynchronous computer-mediated communication. The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwica, Dorota. 2015. Evidential al parecer: Between the physical and the cognitive meaning in Spanish scientific prose of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. Journal of Pragmatics 85: 155–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwica, Dorota. 2017. From seeing to reporting. Grammaticalization of evidentiality in Spanish constructions with ver (‘to see’). In Evidentiality and Modality in European Languages. Discourse-Pragmatic Perspectives. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Marco, Marta Albelda. 2016. La expresión de la evidencialidad en la construcción se ve (que). Spanish In Context 13: 237–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Arrese, Juana I. 2015. Epistemic legitimisation and inter/subjectivity in the discourse of parliamentary and public inquiries: A contrastive case study. Critical Discourse Studies 12: 261–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Arrese, Juana I. 2021. stance, emotion and persuasion: Terrorism and the press. Journal of Pragmatics 177: 135–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, Marion. 2018. Danish PM proposes asylum camps outside the EU. InfoImmigrants, June 7. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam, Fathali M., and Rom Harré. 2010. Words, conflicts and political processes. In Words of Conflict, Words of War: How the Language Weuse in Political Processes Sparks Fighting. Edited by Fathali M. Moghaddam and Rom Harré. Santa Barbara: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Denise E. 1985. Composition as conversation: The computer terminal as medium of communication. In Writing in Nonacademic Settings. Edited by Lee Odell and Dixie Goswami. New York: Guilford, pp. 203–27. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Denise E. 1988. The context of oral and written language: A framework for mode and medium switching. Language in Society 17: 351–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuyts, Jan. 2017. Evidentiality Revisited: Cognitive Grammar, Functional and Discourse-Pragmatic Perspectives. In Evidentiality Reconsidered. Edited by Juana I. Marín-Arrese, Gerda Hassler and Marta Carretero. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 57–83. [Google Scholar]

- Paradisi, Paolo, Marina Raglianti, and Laura Sebastiani. 2021. Online communication and body language. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 15: 709365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plungian, Vladimir A. 2001. The place of evidentiality within the universal grammatical space. Journal of Pragmatics 33: 349–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severinson Eklundh, Kerstin. 1986. Dialogue Processes in Computer-Mediated Communication: A Study of Letters in the COM System. Ph.D. dissertation, LiberFörlag, Stockholm, Sweden. Available online: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-35290</div> (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Slocum, Nikki, and Luk Van Langenhove. 2003. Integration Speak: Introducing Positioning. In The Self and Others: Positioning Individuals and Groups in Personal, Political, and Cultural Contexts. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- Squartini, Mario. 2001. The internal structure of evidentiality in Romance. Studies in Language. International Journal sponsored by the Foundation “Foundations of Language” 25: 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squartini, Mario. 2008. Lexical vs. grammatical evidentiality in French and Italian. Linguistics 4: 6917–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado, Francisco, and Ana Gálvez. 2008. Positioning theory and discourse analysis: Some tools for social interaction analysis. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung 33: 224–51. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. 2022. Global Focus: Europe. Available online: https://reporting.unhcr.org/europe (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Van Bogaert, Julie, and Timothy Colleman. 2013. On the grammaticalization of (’t) schijnt ‘it seems’ as an evidential particle in colloquial Belgian Dutch. Folia Lingüística 47: 481–520. [Google Scholar]

- Van Langenhove, Luk, and Rom Harré. 1999. Positioning as the production and use of stereotypes. In Positioning Theory: Moral Contexts of Intentional Action. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 127–37. [Google Scholar]

- Walther, Joseph B., Caleb T. Carr, and Scott Seung W. Choi. 2010. Interaction of interpersonal, peer, and media influence sources online. A Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites 17: 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton, Oliver. 2018. Boat with hundreds of refugees on board arrives at Spanish port after being turned away by other European countries. The Independent, June 17. [Google Scholar]

- Whitt, Richard J. 2010. Evidentiality and Perception Verbs in English and German. Berlin: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Wiemer, Bjorm. 2010. Evidenzialität aus kognitiver Sicht. In Die slavischen Sprachen im Licht der kognitiven Linguistik/Slavjanskie jazyki vkognitivnom aspekte. Edited by Tanja Anstatt and Boris Norman. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 117–39. [Google Scholar]

- Willems, Dominique. 1983. ‘Regarde voir’: Les verbes de perception visuelle et la complementation verbale. Romanica Candensia 20: 147–58. [Google Scholar]

- Willet, Thomas. 1988. A cross-linguistic survey of the grammaticalization of evidentiality. Studies in Language 12: 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Zhiwei. 2018. Positioning (mis) aligned: The (un) making of intercultural asynchronous computer-mediated communication. Language Learning & Technology 22: 75–94. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Domínguez Romero, E. Ver-Based Evidential Re/Positioning Strategies in Conservative Digital Newspaper Readers’ Comments on Controversial Immigration Policies in Spanish. Languages 2023, 8, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030171

Domínguez Romero E. Ver-Based Evidential Re/Positioning Strategies in Conservative Digital Newspaper Readers’ Comments on Controversial Immigration Policies in Spanish. Languages. 2023; 8(3):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030171

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomínguez Romero, Elena. 2023. "Ver-Based Evidential Re/Positioning Strategies in Conservative Digital Newspaper Readers’ Comments on Controversial Immigration Policies in Spanish" Languages 8, no. 3: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030171

APA StyleDomínguez Romero, E. (2023). Ver-Based Evidential Re/Positioning Strategies in Conservative Digital Newspaper Readers’ Comments on Controversial Immigration Policies in Spanish. Languages, 8(3), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030171