Examining Oral (Dis)Fluency in—uh– —Spanish as a Heritage Language

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Understanding Pauses and Other Markers of Oral (Dis)Fluency

- Pauses; silent, empty, or unfilled pauses: empty interruptions in speech. The threshold of duration ranges between 100 ms (Riazantseva 2001), 250 ms (Bosker et al. 2013; Leonard and Shea 2017), and 400 ms (Derwing et al. 2004) (e.g., “There was a bunny and a (-) big dog”).

- Filled pauses or fillers: interruptions filled with sounds like uh or er, a nasal consonant alone (e.g., mm), or a vowel followed by a nasal consonant (e.g., em, um) (e.g., “The (hum) wolf was ugly”).

- Repetitions: repetitions of syllables or words, unless duplications are semantically motivated, made to provide clarification or specification (e.g., “The thing is that (-) the thing is that the big dog never learns”.

- Self-corrections: modification of the original speech before interruption because the sentence material (generally grammar), in eyes (or voice) of the speaker, needs rectification (e.g., and then the wolf catched (-) caught the rabbit”).

Oral Fluency in Bilingual Literature

3. The Present Study: Toward a Better Understanding of Pauses in Spanish Heritage Speech

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants

4.2. Instrument: Oral Production Task

- (1)

- El lobo [eh-0.709 (filled pause)] es un poquito gordito y el conejo muy [0.523 (silent pause)] po-pequeño y hermoso y el lobo quiero [0.430 (correction] quiere [0.261 (correction)] quería [0.444 (reformulation)] el lobo quería [0.846 (silent pause)] almorzar el conejo.(The wolf is a bit chubby and the rabbit very small and handsome and the wolf want wants wanted the wolf wanted to eat the rabbit).

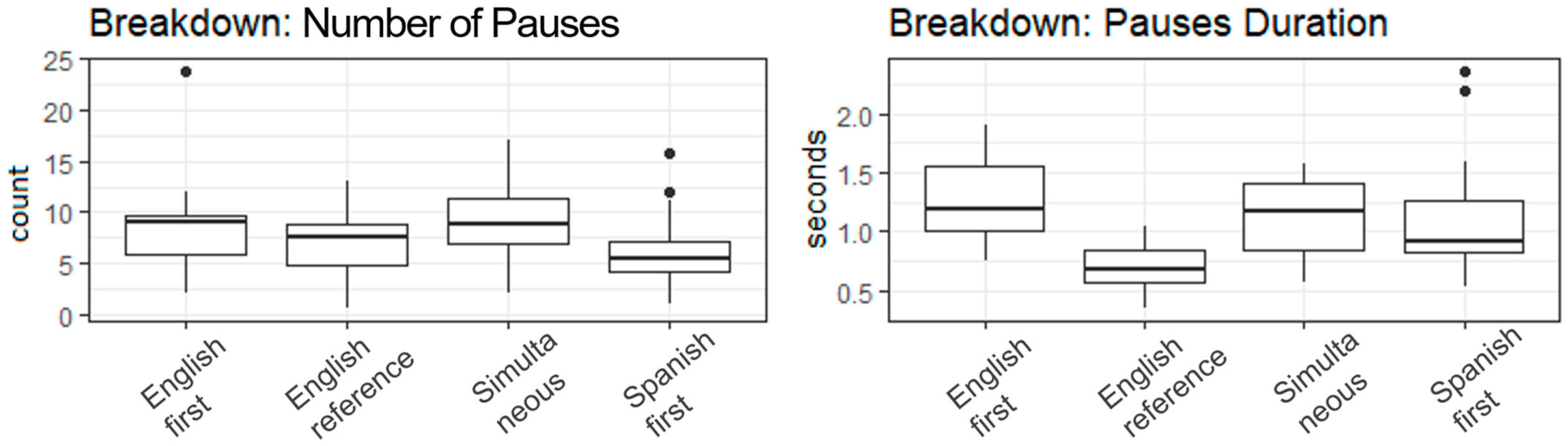

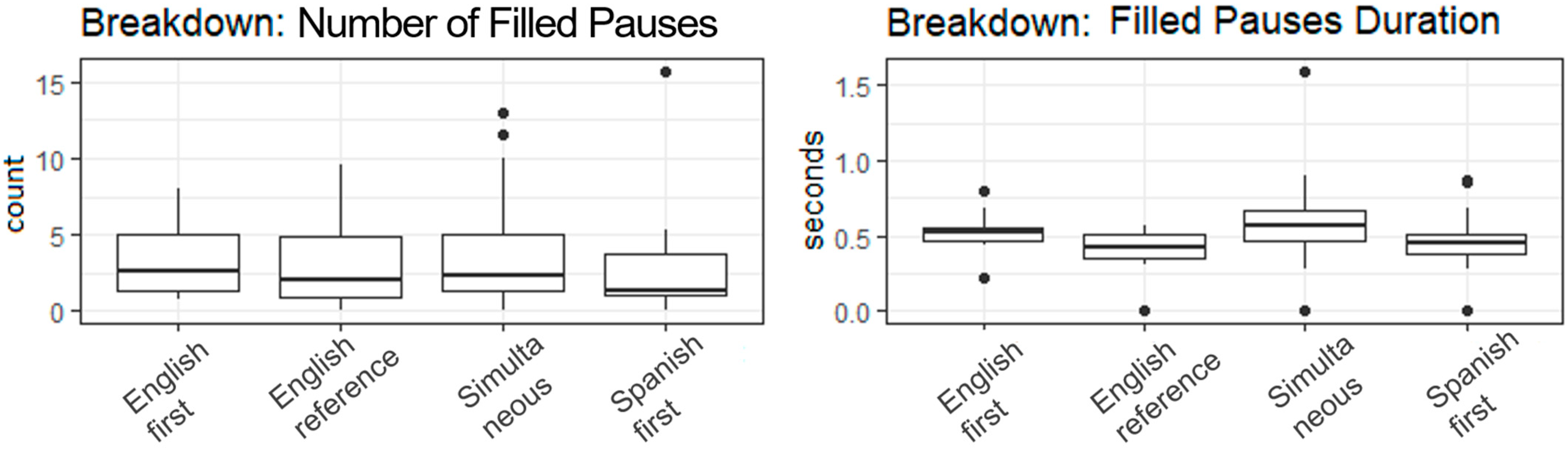

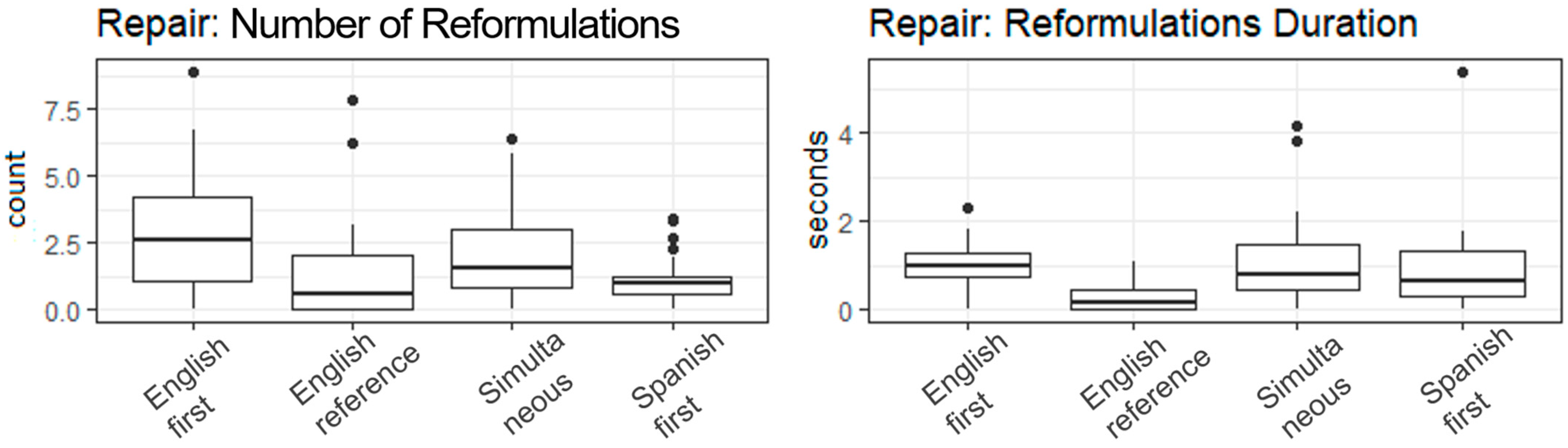

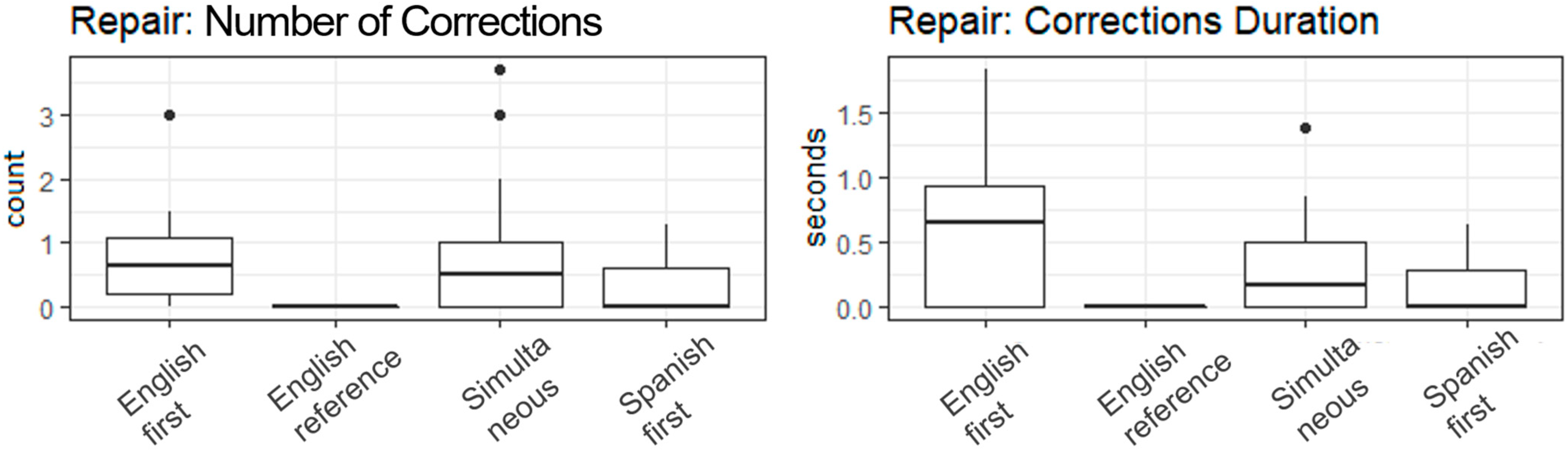

5. Results

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | As a note, pause values for Spanish monolingual and Spanish dominant speakers seem to range between 400 and 700 ms (e.g., Cremades 2016; Llisterri et al. 2019; Blondet 2006). |

| 2 | “Pocho Spanish” is a pejorative term to refer to the Spanish spoken in the US by heritage speakers, specifically Mexican Americans. |

| 3 | Looking back at the work conducted in the early 2000, the idea was that HLLs’ linguistic experiences in the HL during childhood (i.e., exposure to naturalistic input) were responsible for the target-like development of their oral communicative skills (e.g., Polinsky and Kagan 2007; Au et al. 2008). |

| 4 | Fillers are an intrinsic component of natural speech that facilitate production and perception rather than interruptions in the conversation flow. |

| 5 | Questions regarding course number and instructor were added. |

| 6 |

References

- Amengual, Mark. 2019. Type of early bilingualism and its effect on the acoustic realization of allophonic variants: Early sequential and simultaneous bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingualism 23: 954–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, Terry Kit-fong, Leah M. Knightly, Sun-Ah Jun, and Janet S. Oh. 2002. Overhearing a language during childhood. Psychological Science 13: 238–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, Terry Kit-fong, Janet S. Oh, Leah M. Knightly, Sun-Ah Jun, and Laura F. Romo. 2008. Salvaging a childhood language. Journal of Memory and Language 58: 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul, and Maria Polinsky. 2010. White Paper: Prolegomena to Heritage Linguistics. Cambridge: Department of Linguistics, Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong, David, Libby M. Gertken, and Mark Amengual. 2012. Bilingual Language Profile: An Easy-to-Use Instrument to Assess Bilingualism. Austin: University of Texas at Austin. Available online: https://sites.la.utexas.edu/bilingual/ (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- Blondet, María. 2006. Variaciones de la Velocidad de Habla en Español: Patrones Fonéticos y Estrategias Fonológicas. Un Estudio Desde la Producción. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Los Andes, Mérida, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bosker, Hans Rutger, Anne-France Pinget, Hugo Quené, Ted Sanders, and Nivja H. De Jong. 2013. What makes speech sound fluent? The contributions of pauses, speed and repairs. Language Testing 30: 159–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, Jasone. 2000. Pauses and hesitation phenomena in second language production. ITL-International Journal of Applied Linguistics 127: 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1992. Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science 1: 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantoni, Laura, Alejandro Cuza, and Natalia Mazzaro. 2016. Task-related effects in the prosody of Spanish heritage speakers and long-term immigrants. In Intonational Grammar in Ibero-Romance: Approaches across Linguistic Subfields. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cremades, Elga. 2016. El tempo como factor discriminante en el análisis forense del habla: Análisis descriptivo en hablantes bilingües (catalán-español). Estudios Interlingüísticos 4: 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, Nivja H. 2016. Predicting pauses in L1 and L2 speech: The effects of utterance boundaries and word frequency. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 54: 113–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwing, Tony W., Jacqueline Laures-Gore, and Melissa C. Duff. 2004. Acute stress reduces speech fluency. Biological Psychology 100: 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran-Karaoz, Zeynep, and Parvaneh Tavakoli. 2020. Predicting L2 fluency from L1 fluency behavior: The case of L1 Turkish and L2 English speakers. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 42: 671–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echevarría, Leire, and Diego Pascual y Cabo. 2023. Examining the Effects of Spanish Heritage Language Instruction in Students’ Writing Performance over the Course of a Semester. Hispanic Studies Review 7. [Google Scholar]

- Enríquez, Nuria. 2020. Pausas y Actividad Neuronal en la Producción oral de Hablantes de Herencia, Nativos y no Nativos de Español e Inglés Utilizando Encefalograma. Ph.D. thesis, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Erker, Daniel, and Joanna Bruso. 2017. Uh, bueno, em…: Filled pauses as a site of contact-induced change in Boston Spanish. Language Variation and Change 29: 205–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felker, Emily R., Heidi E. Klockmann, and Nivja H. De Jong. 2019. How conceptualizing influences fluency in first and second language speech production. Applied Psycholinguistics 40: 111–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Ying, and Wanyi Du. 2013. A Study on the Oral Disfluencies Developmental Traits of EFL Students—A Report Based on Canonical Correlation Analysis. English Language Teaching 6: 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Amaya, Lorenzo. 2009. New findings on fluency measures across three different learning contexts. In Selected proceedings of the 11th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- García-Amaya, Lorenzo. 2015. A Longitudinal Study of Filled Pauses and Silent Pauses in Second Language Speech. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332554262_A_longitudinal_study_of_filled_pauses_and_silent_pauses_in_second_language_speech (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- García-Amaya, Lorenzo. 2020. An investigation into utterance-fluency patterns of advanced LL bilinguals: Afrikaans and Spanish in Patagonia. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 12: 163–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Amaya, Lorenzo, and Sean Lang. 2020. Filled pauses are susceptible to cross-language phonetic influence: Evidence from Afrikaans-Spanish bilinguals. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 42: 1077–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, Sandra. 2013. Fluency in Native and Nonnative English Speech. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, François. 1980. Spoken word recognition processes and the gating paradigm. Perception & Psychophysics 28: 267–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havekate, Henk. 1987. La cortesía como estrategia conversacional. Diálogos Hispánicos de Amsterdam 6: 27–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kasl, Stanislav V., and George F. Mahl. 1965. Relationship of disturbances and hesitations in spontaneous speech to anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1: 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knightly, Leah M., Sun-Ah Jun, Janet S. Oh, and Terry Kit-fong Au. 2003. Production benefits of childhood overhearing. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 114: 465–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopotev, Mikhail, Kisselev Olesya, and Maria Polinsky. 2020. Collocations and near-native competence: Lexical strategies of heritage speakers of Russian. International Journal of Bilingualism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, Judit. 2006. Speech Production and Second Language Acquisition. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, Jean C., and Louise D. Braida. 2002. Investigating alternative forms of clear speech: The effects of speaking rate and speaking mode on intelligibility. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 112 Pt 1: 2165–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupisch, Tania, and Jason Rothman. 2016. Interfaces in the acquisition of syntax. In Manual of Grammatical Interfaces in Romance. Edited by Susann Fischer and Christoph Gabriel. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, Karen Ruth, and Christine E. Shea. 2017. L2 speaking development during study abroad: Fluency, accuracy, complexity, and underlying cognitive factors. The Modern Language Journal 101: 179–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Level, Willem J. M. 1983. Monitoring and self-repair in speech. Cognition 14: 41–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llisterri, Joaquim, María J. Machuca, and Antonio Ríos. 2019. Caracterización del hablante con fines judiciales: Fenómenos fónicos propios del habla espontánea. E-Aesla 5: 265–78. [Google Scholar]

- López, Belem. 2020. Incorporating language brokering experiences into bilingualism research: An examination of informal translation practices. Language and Linguistics Compass 14: e12361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Belem, Alicia Luque, and Brandy Piña-Watson. 2023. Context, intersectionality, and resilience: Moving toward a more holistic study of bilingualism in cognitive science. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 29: 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, Andrew. 2000. Spanish-speaking Miami in sociolinguistic perspective: Bilingualism, recontact, and language maintenance among the Cuban-origin population. In Research on Spanish in the United States: Linguistic Issues and Challenges. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 271–83. [Google Scholar]

- Maclay, Howard, and Charles E. Osgood. 1959. Hesitation phenomena in spontaneous English speech. WORD 15: 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2013. El bilingüismo en el Mundo Hispanohablante. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2014. Structural changes in Spanish in the United States: Differential object marking in Spanish heritage speakers across generations. Lingua 151: 177–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2023. Heritage Languages: Language Acquired, Language Lost, Language Regained. Annual Review of Linguistics 9: 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Maria Polinsky, eds. 2021. The Cambridge Handbook of Heritage Languages and Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Fernández, Francisco. 2002. Producción, Expresión e Interacción Oral. Madrid: Arco/Libros. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, Daniel C., and Sabine Kowal. 2005. Where do interjections come from? A psycholinguistic analysis of Shaw’s Pygmalion. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 34: 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, Lourdes. 2021. Epílogo. El contexto sociopolítico y el español como lengua de herencia. In Aproximaciones al Estudio del Español como Lengua de Herencia. London: Routledge, pp. 275–90. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, Maria Luisa, Marta Llorente Bravo, and Maria Polinsky. 2018. De bueno a muy bueno: How pedagogical intervention boosts language proficiency in advanced heritage learners. Heritage Language Journal 15: 203–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual y Cabo, Diego, and Inmaculada Gómez Soler. 2015. Preposition Stranding in Spanish as a Heritage Languages. Heritage Language Journal 12: 533–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual y Cabo, Diego, and Silvina Montrul. 2021. Consideraciones sobre algunos aspectos de la morfosintaxis del español como lengua de herencia en adultos. In Aproximaciones al Estudio del Español como Lengua de Herencia. London: Routledge, pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Plonsky, Luke, and Frederick L. Oswald. 2014. How big is “big”? Interpreting effect sizes in L2 research. Language Learning 64: 878–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Olga Kagan. 2007. Heritage languages: In the ‘wild’ and in the classroom. Language and Linguistics Compass 1: 368–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Gregory Scontras. 2019. Understanding heritage languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23: 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, Josh, Paola Guerrero-Rodriguez, and Diego Pascual y Cabo. 2020. Heritage language anxiety in two Spanish language classroom environments: A comparative mixed methods study. Heritage Language Journal 17: 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragsdale, J. Donald. 1976. Relationships between hesitation phenomena, anxiety, and self-control in a normal communication situation. Language and Speech 19: 257–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Rajiv. 2014. On the Status of the Phoneme /b/ in Heritage Speakers of Spanish. Sintagma 26: 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Rajiv. 2015. Manifestations of /bdg/ in heritage speakers of Spanish. Heritage Language Journal 12: 48–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Rajiv. 2016. On the nuclear intonational phonology of heritage speakers of Spanish. In Advances in Spanish as a Heritage Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Rajiv, and Rebecca Ronquest. 2015. The heritage Spanish phonetic/phonological system: Looking back and moving forward. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 8: 403–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazantseva, Anastasia. 2001. Second language proficiency and pausing a study of Russian speakers of English. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 23: 497–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggenbach, Heidi. 1991. Toward an understanding of fluency—A microanalysis of nnonnative speaker conversations. Discourse processes 14: 423–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquest, Rebecca. 2013. An acoustic examination of unstressed vowel reduction in heritage Spanish. In Selected Proceedings of the 15th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 151–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquest, Rebecca. 2016. Stylistic Variation in Heritage Spanish Vowel Production. Heritage Language Journal 13: 275–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. 2020. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Said-Mohand, Aixa. 2008. Aproximación sociolingüística al uso de entonces en el habla de jóvenes bilingües estadounidenses. Sociolinguistic Studies 2: 97–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Muñoz, Ana. 2016. Heritage language healing? Learners’ attitudes and damage control in a heritage language classroom. In Advances in Spanish as a Heritage Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 49, pp. 205–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, Sandra. 2015. Las variables temporales en el español de Costa Rica y de España: Un estudio comparativo. Revista de Filología y Lingüística de la Universidad de Costa Rica 41: 127–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalowitz, Norman. 2010. Cognitive Bases of Second Language Fluency. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Eurie. 2005. The Perception of Foreign Accents in Spoken Korean by Prosody: Comparison of Heritage and Non-heritage Speakers. The Korean Language in America 10: 103–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakoli, Parvaneh. 2020. Making fluency research accessible to second language teachers: The impact of a training intervention. Language Teaching Research 27: 1362168820951213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchiano, Marco. 2020. Efficient Effect Size Computation. R Package Version 0.8.1. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/effsize/index.html (accessed on 3 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Torres, Lourdes, and Kim Potowski. 2008. A comparative study of bilingual discourse markers in Chicago Mexican, Puerto Rican, and MexiRican Spanish. International Journal of Bilingualism 12: 263–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tree, Jean E. F. 1995. The Effects of False Starts and Repetitions on the Processing of Subsequent Words in Spontaneous Speech. Journal of Memory and Language 34: 709–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Amelia. 2021. Qué barbaridad, son latinos y deberían saber español primero’: Language Ideology, Agency, and Heritage Language Insecurity across Immigrant Generations. Applied Linguistics 42: 113–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 2001. Heritage language students: Profiles and possibilities. In Heritage Languages in America: Preserving a National Resource. McHenry: Center for Applied Linguistics, pp. 37–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, Richard. 1984. Language production in foreign and native languages: Same or different. In Second Language Productions. Tübingen: Narr Verlag, pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Simon A., and Malgorzata Korko. 2019. Pause behavior within reformulations and the proficiency level of second language learners of English. Applied Psycholinguistics 40: 723–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Speak | Understand | Read | Write | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eng | Spa | Eng | Spa | Eng | Spa | Eng | Spa | |

| Seq_Eng first | 6.0 (0) | 3.64 (1.08) | 5.93 (0.27) | 4.5 (0.94) | 5.9 (0.3) | 4.07 (1.2) | 6 (0) | 3.57 (1.4) |

| Seq_Spa first | 5.8 (0.52) | 4.35 (0.9) | 5.9 (0.44) | 5.5 (0.61) | 5.9 (0.31) | 4.9 (0.79) | 5.7 (0.73) | 4.2 (1.06) |

| Simultaneous | 5.8 (0.55) | 3.7 (1.05) | 6 (0) | 5 (0.91) | 5.95 (0.22) | 4.58 (0.69) | 5.79 (0.55) | 3.7 (0.86) |

| Simultaneous English First | Simultaneous Spanish First | English First Spanish First | Simultaneous English Reference | English First English Reference | Spanish First English Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pauses | ||||||

| count | 0.15 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.13 |

| duration | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 1.49 | 1.57 | 1.04 |

| Filled pauses | ||||||

| count | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.15 |

| duration | 0.35 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.06 |

| Reformulations | ||||||

| count | 0.76 | 0.65 | 1.4 | 0.29 | 0.95 | 0.21 |

| duration | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 1.01 | 1.53 | 0.82 |

| Corrections | ||||||

| count | 0.41 | 0.69 | 0.41 | 1.16 | 1.27 | 1.02 |

| duration | 0.22 | 0.45 | 0.8 | 1.02 | 1.47 | 1.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuartero, M.; Domínguez, M.; Pascual y Cabo, D. Examining Oral (Dis)Fluency in—uh– —Spanish as a Heritage Language. Languages 2023, 8, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030173

Cuartero M, Domínguez M, Pascual y Cabo D. Examining Oral (Dis)Fluency in—uh– —Spanish as a Heritage Language. Languages. 2023; 8(3):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030173

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuartero, Marina, María Domínguez, and Diego Pascual y Cabo. 2023. "Examining Oral (Dis)Fluency in—uh– —Spanish as a Heritage Language" Languages 8, no. 3: 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030173

APA StyleCuartero, M., Domínguez, M., & Pascual y Cabo, D. (2023). Examining Oral (Dis)Fluency in—uh– —Spanish as a Heritage Language. Languages, 8(3), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030173