An Example of Linguistic Stylization in Spanish Musical Genres: Flamenco and Latin Music in Rosalía’s Discography

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Musical Genres: The Object of Study of Socio-Stylistics

2.1. Stylization and Indexicality in Music Genres

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Who Is Rosalía?

3.2. Corpus Development and Sample Determination

3.3. Linguistic and Extra-Linguistic Variables

- Articulatory lenition of the /s/ sound. In Spanish, the pronunciation of the sound /s/ in the implosive and final position presents some variants produced by articulatory lenition. The /s/ can be pronounced aspirated ([ehˈtɾeʝa] estrella (“star”)) or elided ([ˈfloɾe ˈasule] flores azules (“blue flowers”)).

- Aspiration of /x/ (velar fricative voiced sound). In some innovative Spanish-speaking areas /x/ is often pronounced as [h]. Thus, it is possible to hear an utterance like iré joven (“I Will go Young”) as [iˈɾe ˈhoβ̞en], for example.

- Seseo. Neutralization of the sounds /s/ and /θ/ with an [s] solution. In Rosalía, for example, we have found examples of seseo when she says [dehkonoˈsia] for desconocida (“unknown”).

- Neutralization of liquid sounds /l/ and /ɾ/. In this variable we are going to analyze two different results according to the type of musical genre. As Fernández de Molina Ortés (2020) found, in flamenco we can find examples of rhotacism, i.e., a neutralization of /l/ and /ɾ/ in favor of the rhotic [ɾ]. Thus, an example of rhotacism would be to pronounce alma (“soul”) as [ˈaɾma], for example. In Latin music, especially in Caribbean singers, we can find examples of lambdacism, i.e., pronouncing /ɾ/ as an [l]. For example, a case of lambdacism would be to pronounce comer (“eat”) as [koˈmel] (López 2016; Moreno-Fernández 2019; Maymí and Ortiz-López 2022; Moreno Fernández and Otero Roth 2016).

- Elision of intervocalic /d/. In Spanish, the voiced stop /d/ within a word is pronounced as an approximant [ð̞]. In this intervocalic context, /d/ undergoes articulatory lenition and, in some cases, the sound disappears completely. In Spanish, it is common for the elision of /d/ in the ending -ado (cansado “tired” [kanˈsao]). However, in other endings it can be lost, as in -ido, -ida (perdido, perdida “lost” [peɾˈð̞io], [peɾˈð̞ia]), in -odo and -oda (todo, toda “all” [ˈto], [ˈtoa]). In flamenco, it is even found in some combinations as -eda (enfermedad “illness” [ẽɱfeɾmeˈa]). However, the loss of /d/ is a phenomenon related to medium and low sociolects.

- Other changes. From a phonetic point of view, we analyze syllabic and vowel apocope in words such as para (“for”) and muy (“very”). In Spanish these are pronounced as [ˈpa] or [ˈmu] in relaxed contexts; we will also analyze the loss of intervocalic /d/ in different endings.

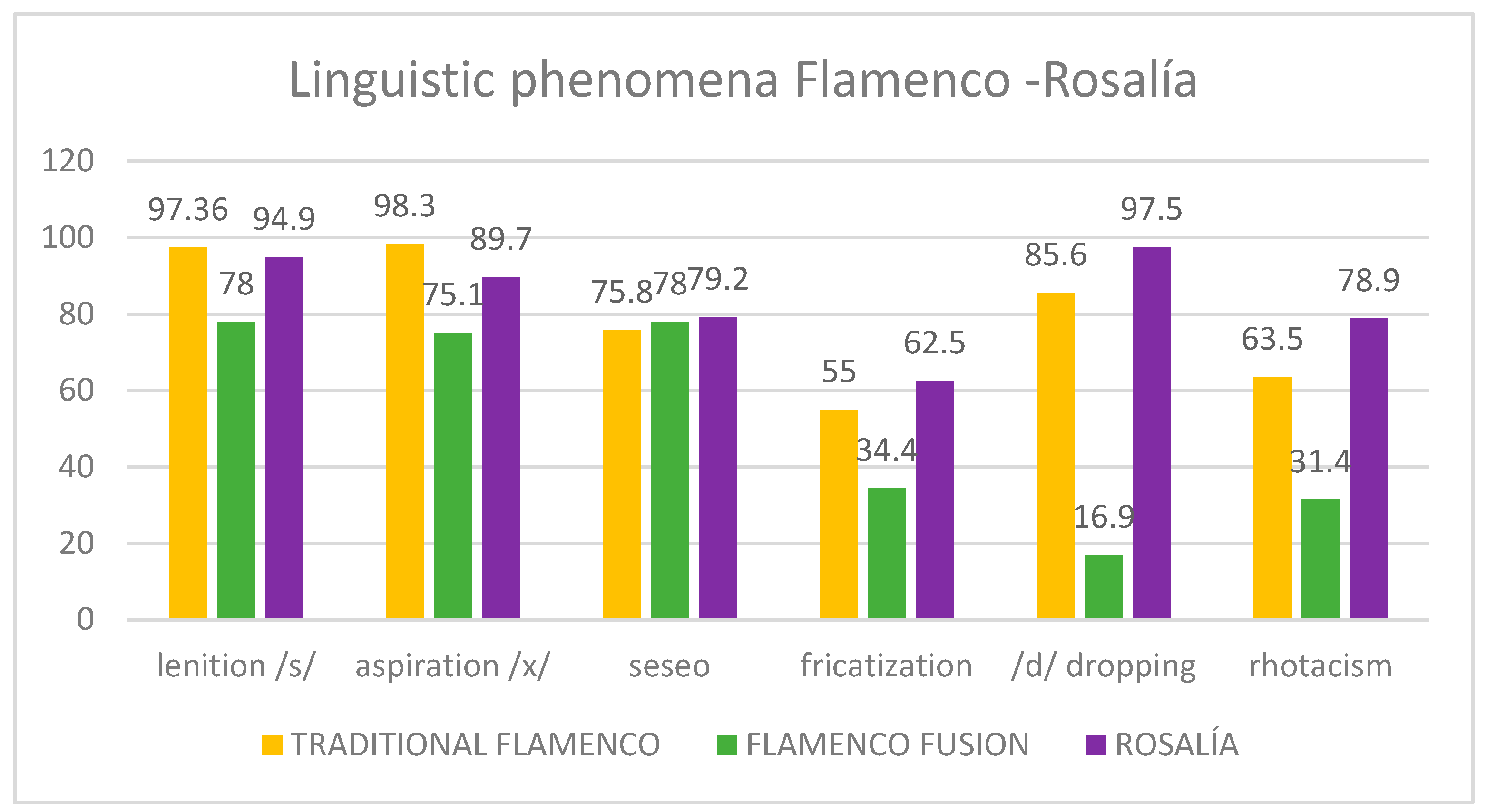

4. Results

4.1. Linguistic Uses in the Musical Sphere

4.1.1. Flamenco

4.1.2. Latin Music

4.2. Linguistic Characteristics of the Interviews

- Me siento bien agradecida;

- Yo pienso en que casi todo lo que me va pasando es bien orgánico;

- El pueblo tiene un nombre bien, bien largo.

- 4.

- Me gusta la gente, la vibra aquí, en la calle;

- 5.

- ¿Crees en el matrimonio? Sí, definitivo;

- 6.

- ¿Le gusta el snapple?;

- 7.

- Me acuerdo de cantar en los shows.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This type of research follows the latest trends in sociolinguistics; specifically, we refer to the sociolinguistics of the third wave (Eckert 2012, 2018), from which the study of the linguistic characteristics of an individual can allow us to observe the differential characteristics in the generality of larger works. |

| 2 | Trudgill justified this new variety as a necessary change driven by the bands of the new genres to break the American cultural domination of the time thanks to the international influence of groups such as the Beatles: with Beatlemania, British bands became confident and relied on their own linguistic features. In reality, this is a reverse initiative design, because in the genre the bands break with the institutionalized way of singing, American English, and mix it with a new one, British English (Bell 1984). |

| 3 | We have used Gibson and Bell’s theory of indexicality in this study, because it is directly related to musical genres. However, these classifications and themes can also be found in the work of Silverstein (2003) in other registers. |

| 4 | A record of the authors of the third generation can be found in the reference (Fernández de Molina Ortés 2020). The sample of cantaores was selected taking into account different generations and genres. Likewise, we used the variable origin to distinguish Andalusian and non-Andalusian professionals (see distribution, for example, in (Fernández de Molina Ortés 2022a, 2022b)). |

| 5 | The singers come from the Caribbean area (Daddy Yankee, Don Omar, Annuel, Raw Alejandro) and from other areas such as Colombia (J. Balvin, Sebastián Yatra, Karol G., Becky G.) and Panama (Joey Montana). |

| 6 | In the corpus analysis section, we will describe the phenomena of flamenco and Latin music from the control corpus. We will then compare these phenomena with the results of Rosalía. |

| 7 | From a historical and cultural point of view, (current) Latin music and flamenco fusion are closely related. The two genres were created as a consequence of social and political changes and also by industrialization and globalization, especially from the 1960s onwards in America (see González 2011; Recasens and Spencer 2011) and in Spain (Steingress 2005; Cruces Roldán 2008, 2012). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | Seseo is a variant that can currently be found in Andalusia. Sociolinguistic studies currently locate the phenomenon in Seville (Santana 2017; Villena-Ponsoda 1997, 2005), Malaga and Granada (Moya and Sosinski 2015), for example. This linguistic phenomenon is prestigious; however, it is not the only variant but rather alternates with other variants such as the distinction between /θ/ and /s/ and the lisp. Furthermore, social factors, such as gender and education level, influence the selection of these different variants. |

| 10 | However, although it is common for the singer to apocope the adverb “muy”, variants with the full pronunciation [ˈmui̯] have also been compiled. |

| 11 | As we see in the examples, Rosalía uses the labiodental for the sound /b/, regardless of the spelling of the sound, b, v. |

| 12 | In the corpus, 45 realizations of /ɾ/ have been analyzed and, in 100% of the cases, the pronunciation is percussive rhotic. |

| 13 | In the Latin music control corpus, 70 cases have been collected, of which 63 have been pronounced in an apocopated form. |

| 14 | According to the Diccionario de Americanismos (RAE and ASALE 2010), one of the meanings of “juquear(se)” in Honduras is “enfadarse mucho con alguien” (“to get very angry with someone”). In the case of “tote”, and also taking this dictionary as a reference, in Colombia, this adjective, in popular use, refers to a person who “está de mal humor” (“He/she is in a bad mood”). |

| 15 | “Baile con movimientos sensuales” (“Dance with sensual movements”) (RAE and ASALE 2010), located in Puerto Rico. |

| 16 | Included in this analysis are aspirated and elided pronunciations of /-s/, aspiration of /-x-/, the use of seseo, lambdacism or geminate variants of /ɾ/ and a following sound. |

| 17 | The use of “bien” as an intensifier in Spanish can be consulted in the entry of the Diccionario Panhispánico de Dudas (RAE 2005), available online at https://www.rae.es/dpd/bien (accessed on 10 December 2022). |

| 18 | To check the combinations of “bien” in different geographical areas, we have used the database of the Corpus de Referencia del Español Actual (RAE n.d.). |

References

- Agha, Asif. 2003. The Social Life of Cultural Value. Language & Communication 23: 231–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Edward G. 2004. Eminem’s Construction of Authenticity. Popular Music and Society 27: 335–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, Joan C. 2009. You’re Not from New York City, You’re from Rotherham: Dialect and Identity in British Indie Musi. Journal of English Linguistics 37: 223–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Allan. 1984. Language Style as Audience Design. Language in Society 13: 145–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Alan, and Andy Gibson. 2011. Staging Language: An Introduction to the Sociolinguistics of Performance. Journal of Sociolinguistics 15: 555–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blas Arroyo, José Luis. 1995. De Nuevo El Español y El Catalán, Juntos y En Contrate. Estudio de Actitudes Lingüísticas. Sintagma: Revista de Lingüística 7: 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Blas Arroyo, José Luis. 2004. El Español Actual En Las Comunidades Del Ámbito Lingüístico Catalán. In Historia de La Lengua Española. Edited by Rafael Cano. Barcelona: Ariel, pp. 1065–86. [Google Scholar]

- Blas Arroyo, José Luis. 2021. Español a La Catalana: Variación Vernácula e Identidad En La Cataluña Soberanista. Oralia: Análisis Del Discurso Oral 22: 7–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonero Cano, Pedro. 2007. Formas de Pronunciación En Andalucía. Modelos de Referencia y Evaluación Sociolingüística. In Sociolingüística Andaluza 15. Estudios Dedicados al Profesor Miguel Ropero. Edited by Pedro Carbonero Cano and Juana Santana Marrero. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, Secretariado de Publicaciones. pp. 121–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cruces Roldán, Cristina. 2008. El Aplauso Difícil: Sobre La ‘Autenticidad’, El ‘Nuevo Flamenco’ y La Negación Del Padre Jondo. In Comunicación y Música Vol. II. Edited by Miguel de Aguilera. Barcelona: UOC Press, pp. 167–211. [Google Scholar]

- Cruces Roldán, Cristina. 2012. Hacia Una Revisión Del Concepto ‘Nuevo Flamenco’. La Intelectualización Del Arte. In Las Fronteras Entre Los Géneros. Flamenco y Otras Músicas de Tradición Oral. Edited by José Miguel Díaz-Báñez, Francisco Javier Escobar Borrego and Inmaculada Ventura Molina. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt, Maeve, and Madeline Vdoviak-Markow. 2020. ‘I Ain’t Sorry’: African American English as a Strategic Resource in Beyoncé’s Performative Persona. Language & Communication 77: 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2012. Three Waves of Variation Study: The Emergence of Meaning in the Study of Sociolinguistic Variation. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2018. Third Wave Variationism. Oxford Handbook Online. Oxford: Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Walter F., and Leslie Ash. 2004. AAVE Features in the Lyrics of Tupac Shakur: The Notion of ‘Realness’. Word 55: 165–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Molina Ortés, Elena. 2020. Los Sonidos Del Flamenco: Análisis Fonético de ‘Los Orígenes’ Del Cante. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación 24: 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Molina Ortés, Elena. 2022a. Cambios Lingüísticos en el Cante: Evolución Fonética En Los Cantaores Del Flamenco Tradicional y El Flamenco Nuevo. In Estudios de Lingüística Hispánica. Teorías, Datos, Contextos y Aplicaciones. Edited by Laura Mariottini and Monica Palmerini. Madrid: Dykinson, pp. 235–262. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Molina Ortés, Elena. 2022b. El Flamenco Puro Desde Una Perspectiva Lingüística. Fenómenos Fonéticos Como Rasgos de Identidad. In Normatividad, Equivalencia y Calidad En La Traducción e Interpretación de Lenguas Ibéricas. Edited by Katarzyna Popek-Bernat. Berlín: Peter Lang, pp. 54–75. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Molina Ortés, Elena, and Juan M. Hernández-Campoy. 2018. Geographic Varieties of Spanish. In The Cambridge Handbook of Spanish Linguistics. Edited by Kimberly L. Geeslin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 496–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarta, Ekaterina. 2023. Cultural and Linguistic Features of British Rap (Brit-Hop). Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4324941 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Garachana, Mar. 2018. Gramáticas En Contacto. Inhibición Del Cambio Lingüístico y Gramaticalización En La Convivencia Entre El Español y El Catalán En Barcelona. Revista Internacional de Lingüística Iberoamericana 16: 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Mouton, Pilar. 2007. Lenguas y Dialectos de España, 5th ed. Madrid: Arco/libros. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Andy, and Allan Bell. 2012. Popular Music Singing as Referee Design. In Tyle-Shifting in Public: New Perspectives on Stylistic Variation. Edited by Juan Manuel Hernández-Campoy and Juan Antonio Cutillas-Espinosa. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 139–64. [Google Scholar]

- González, Juan Pablo. 2011. Música Popular Urbana En La América Latina Del Siglo XX. In A Tres Bandas. Mestizaje, Sincretismo e Hibridación En El Espacio Sonoro Iberoamericano. Madrid: AKAL, pp. 205–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hualde, José Ignacio. 2005. Los Sonidos Del Español. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, Lisa. 2022. English Rock and Pop Performances. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, Lisa, and Michael Westphal. 2017. Rihanna Works Her Multivocal Pop Persona: A Morpho-Syntactic and Accent Analysis of Rihanna’s Singing Style. English Today 33: 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Luis Ortiz. 2016. Dialectos Del Español de América: Caribe Antillano (Morfosintaxis y Pragmática). In Enciclopedia de Lingüística Hispánica. Oxfordshire: Routledge, Vol. 2, pp. 316–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maymí, Cristina Isabel, and Luis Ortiz-López. 2022. Contacto Dialectal y Percepciones Sociofonéticas En El Caribe. In Las Lenguas de Las Américas. Edited by Paul Danler and Jannis Harjus. Berlin: Logos Verlag Berlin, pp. 333–56. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Fernández, Francisco. 2019. Variedades de La Lengua Española. In Variedades de La Lengua Española. Series: Routledge Introductions to Spanish Language and Linguistics. New York: Routledge, pp. 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Fernández, Francisco, and Jaime Otero Roth. 2016. Atlas de La Lengua Española En El Mundo. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Moya Corral, Juan Antonio. 2007. Noticia de Un Sonido Emergente: La Africada Dental Procedente Del Grupo -St- En Andalucía. Revista de Filología 25: 457–65. [Google Scholar]

- Moya, Juan Antonio, and Marcin Sosinski. 2015. La Inserción Social Del Cambio. Distinción de s/θ En Granada. Análisis En Tiempo Aparente y En Tiempo Real. LEA 37: 5–44. [Google Scholar]

- Poch Oliver, Dolors. 2019. El Español de Cataluña En Los Medios de Comunicación. Edited by Dolors Poch Olivé. Madrid: Iberoamericana Vervuert. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAE. 2005. Diccionario Panhispánico De Dudas (DPD). Available online: https://Dpej.Rae.Es/ (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- RAE, and ASALE. 2010. Diccionario de Americanismos. Madrid: Santillana. [Google Scholar]

- RAE—Real Academia Española. n.d. CREA: Corpus de Referencia Del Español Actual. Available online: www.rae.es (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Recasens, Albert, and Cristian Spencer. 2011. Mestizaje, Sincretismo e Hibridación En El Espacio Sonoro Latinoamericano. Madrid: AKAL. [Google Scholar]

- Rius-Escudé, Agnès. 2020. Las Vocales Del Catalán Central En Habla Espontánea. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a La Comunicación 82: 209–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruch, Hanna. 2008. La Variante [ts] En El Español de La Ciudad de Sevilla. Aspectos Fonético-Fonológicos y Sociolingüísticos de Un Sonido Innovador. Zürich: Universidad de Zürich. [Google Scholar]

- Ruch, Hanna, and Sandra Peters. 2016. On the Origin of Post-Aspirated Stops: Production and Perception of/s/+ Voiceless Stop Sequences in Andalusian Spanish. Laboratory Phonology 7: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy Alim, H. 2002. Street-Conscious Copula Variation in the Hip Hop Nation. American Speech 77: 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, Juana. 2017. Factores Externos e Internos Influyentes En La Variación de/θs/En La Ciudad de Sevilla. Analecta Malacitana 34: 143–77. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, Michael. 2003. Indexical Order and the Dialectics of Sociolinguistic Life. Language & Communication 23: 193–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Paul. 1999. Language, Culture and Identity: With (Another) Look at Accents in Pop and Rock Singing. Multilingua 18: 343–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingress, Gerhard. 2005. La Hibridación Transcultural Como Clave de La Formación Del Nuevo Flamenco. Música Oral Del Sur. Revista Internacional 6: 119–52. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, Peter. 1980. Acts of Conflicting Identity: A Sociolinguistic Look at British Pop Songs. In Aspects of Linguistic Behaviour: Festschrift for R.B. Le Page. York Papers in Linguistics, 9. Edited by Manikhu W. Sugathapala de Silva. York: University of York. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, Peter. 1983. Acts of Conflicting Identity: The Sociolinguistics of British Pop-Song Pronunciation. In On Dialect: Social and Geographical Perspectives. Edited by Peter Trudgill. Oxford and New York: Basil Blackwell y New York University Press, pp. 141–60. [Google Scholar]

- Vida Castro, Matilde. 2015. Resilabificación de La Aspiración de/-s/Ante Oclusiva Dental Sorda. Parámetros Acústicos y Variación Social. In Perspectivas Actuales En El Análisis Fónico Del Habla. Tradición y Avances En La Fonética Experimental. Edited by Adrián Cebedo Nebot. Valencia: Universidad de Valencia, vol. 7, pp. 441–51. [Google Scholar]

- Vida Castro, Matilde. 2016. Correlatos Acústicos y Factores Sociales En La Aspiración de/-s/Preoclusiva En La Variedad de Málaga (España). Análisis de Un Cambio Fonético En Curso. Lingua Americana 38: 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vida Castro, Matilde. 2018. Variación y Cambio Fonético En La Aspiración de/s/ Preoclusiva. Caracterización Acústica y Distribución Social En La Ciudad de Málaga. In El Paisaje. Percepciones Interdisciplinares Desde Las Humanidades. Edited by Emilio Ortega Arjonilla. Granada: Comares, pp. 101–9. [Google Scholar]

- Vida Castro, Matilde. 2022. On Competing Indexicalities in Southern Peninsular Spanish. A Sociophonetic and Perceptual Analysis of Affricate [Ts] through Time. Language Variation and Change 34: 137–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Pujol, M. Rosa. 2007. Sociolinguistics of Spanish in Catalonia. International Journal of The Sociology of Language 184: 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena-Ponsoda, Juan Andrés. 1997. Convergencia y Divergencia Dialectal En El Continuo Sociolingüístico Andaluz: Datos Del Vernáculo Urbano Malagueño. ELUA 19: 83–125. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Ponsoda, Juan Andrés. 2005. Efectos Fonológicos de La Coexistencia de Modelos Ideales En La Comunidad de Habla y En El Individuo. Datos Para La Representación de La Variación Fonológica Del Español de Andalucía. Interlingüística 16: 43–70. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Ponsoda, Juan Andrés. 2022. El Español En España. In Dialectología Hispánica. Edited by Francisco Moreno-Fernández and Rocío Caravedo. London: Routledge, pp. 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Intervention | Example | Time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Musical intervention | Flamenco | Los Ángeles (2017) | 49:06 min |

| El mal querer (2018) | 28:10 min | ||

| Latino | Motomami (2022): “La fama”, “Candy”, “Delirio de grandeza”, “Bizcochito” Colaboraciones: “Con altura”, “El pañuelo”, “Yo x ti tú x mí”, “TKN”, “Relación Sech” “Lo vas a olvidar”, “La noche de noche”, “Besos mojados” | 34:38 min | |

| Interviews | National | Interview on Radio 3 (2022) I | 10 min |

| Interview with Javi y Mar (Cadena 100) (2022) II | 10 min | ||

| International | Interview with Alofoke (Dominican productor) III | 10 min | |

| Interview “Primer impacto” (Univisión) IV | 10 min |

| Style of Music | Analysis Time | Analysis Lemmas |

|---|---|---|

| Flamenco | 44 h | 94,978 lemmas |

| Latin music | 47:22 min | 1401 lemmas |

| Musical | Public | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-innovative | N | 52 | 393 | 445 |

| /%/ | 9.7% | 97.5% | 100.00% | |

| Innovative | N | 513 | 10 | 523 |

| /%/ | 90.8% | 2.5% | 100.00% | |

| Total | 565 | 403 | 968 | |

| Caribbean | Non-Caribbean | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Lambdacism | 41 | 63.1% | 1 | 2.1% |

| Non-lambdacism | 24 | 36.9% | 44 | 93.6% |

| Assimilation | 0 | 0% | 2 | 4.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández de Molina Ortés, E. An Example of Linguistic Stylization in Spanish Musical Genres: Flamenco and Latin Music in Rosalía’s Discography. Languages 2023, 8, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020128

Fernández de Molina Ortés E. An Example of Linguistic Stylization in Spanish Musical Genres: Flamenco and Latin Music in Rosalía’s Discography. Languages. 2023; 8(2):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020128

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández de Molina Ortés, Elena. 2023. "An Example of Linguistic Stylization in Spanish Musical Genres: Flamenco and Latin Music in Rosalía’s Discography" Languages 8, no. 2: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020128

APA StyleFernández de Molina Ortés, E. (2023). An Example of Linguistic Stylization in Spanish Musical Genres: Flamenco and Latin Music in Rosalía’s Discography. Languages, 8(2), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020128