Multimodal Transduction and Translanguaging in Deaf Pedagogy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodological Framework

2.1. Impetus

2.2. Questions and Design

2.3. Population, Site, Sample

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. A Theory of Multimodal Transduction in Deaf Pedagogy

3.1. Metatext

3.2. Multimodal Transduction in Deaf Pedagogy

3.3. Contrasting Multimodal Transduction and Translanguaging

Translanguaging reconceptualizes language as a multilingual, multisemiotic, multisensory, and multimodal resource for sense- and meaning-making… It has the capacity to enable us to explore the [holistic] human mind… and rethink some of the bigger, theoretical issues in linguistics.(n.p., emphases added)

3.4. Interpreting Data on Multimodal Transduction

3.5. Multimodal Transduction: Power and Axiology in Deaf Education

4. Data—Multimodal Transduction in Use: Three Case Analyses

4.1. Introduction to Data about MT

- a print word fixes the meaning of an image in an English class on new media forms

- two mathematical formulae are drawn on the board prior to a chemistry experiment

- a gesture explicates the connotation of a print word in a composition/rhetoric course

- an ASL narrative is metonymized with imagery in a science laboratory infographic

- an image captures “the feeling” or ethos of an era in a history or philosophy lecture

- a diagram is explained in detail using a descriptive text in the science lecture hall

- a drawing provides contextual cues for locating keywords in the computer lab

- a visual tool simplifies commonly used ASL phrases in the linguistics classroom

- a photograph documents a correct result in a science laboratory procedure

- a Google image search illustrates concepts in developmental writing classes

- a gesture links a textual definition with its applications in math word problem sets

- an ASL poem is “back-translated” from ASL into English in a deaf literature class

4.2. Case-Analysis 1—Astoria

4.2.1. Main Claim

4.2.2. Evidence

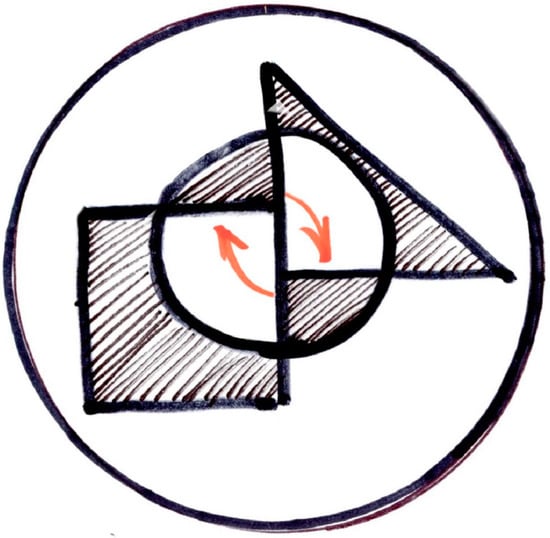

| Astoria told me she wanted to explore spatiality. She used language as data to describe spatial arrangements. She creatively uses ASL classifiers, the in-progress diagram, and complex gestures to ask questions about the particularities of spatial arrangements. She asked: “How is a bento box arranged? How is it eaten, from the center to outside or outside to center? Can circles represent fried zucchini? May small ovals characterize onigiri? Can triangles show winter squash?” In addition, Astoria used other tools from her semiotic toolkit: arrows, shapes, typewritten digital text, handwritten English, and images. Notably, she used ASL classifiers to illustrate spatial concepts from the text and ask questions. The English word “perched,” was a focus as she asks: “How might we depict a ‘flower perching on an egg’?” Her query was accompanied by an ASL classifier skit, showing how birds alight on a wire. | |

| As the class closely analyzed and unpacked the text, it became an act of social critical thinking. Together, they signed, drew, wrote, and gestured until the spatial arrangements and drawn elements generated a cohesive image. By using close reading and unpacking the image and the text, members of the class determined the placement and arrangement of items and answered the following questions: “What goes on top, to the left, right, center?” Astoria and her students collectively decided where to add an element to the diagram. Astoria physically drew the visual representations but under guidance from her students. Hypothetical arrangements were discussed, tested, and agreed upon (or changed) before setting them down in ink. Spatial arrangements were discussed with English, ASL with classifiers, and gestures but they were affixed by the visual image. Options were shown with language, but meaning was determined by drawing. | |

| Astoria’s Data End | (OBSERVATION 1, FIELD NOTE, pp. 5, 9). |

4.2.3. Implications

I am a visual person and do a lot of drawing myself. I often create concept maps, charts, graphs, or other images to make sense of new content. So, this [change] is natural for me. I just go through my toolbox… and try different methods—drawing, images from Google… There are instances where I ask students to do this (draw, find images/content, etc.)—to depict their understanding and how they would apply the content they learned. This helps me gauge their learning process (MEMBER CHECKING, p. 4, brackets added, parentheses original).

4.3. Case-Analysis 2—Howard

4.3.1. Main Claim

4.3.2. Evidence

| Field Note: |

| I asked Howard: “What is the visual tool? What is its purpose?” |

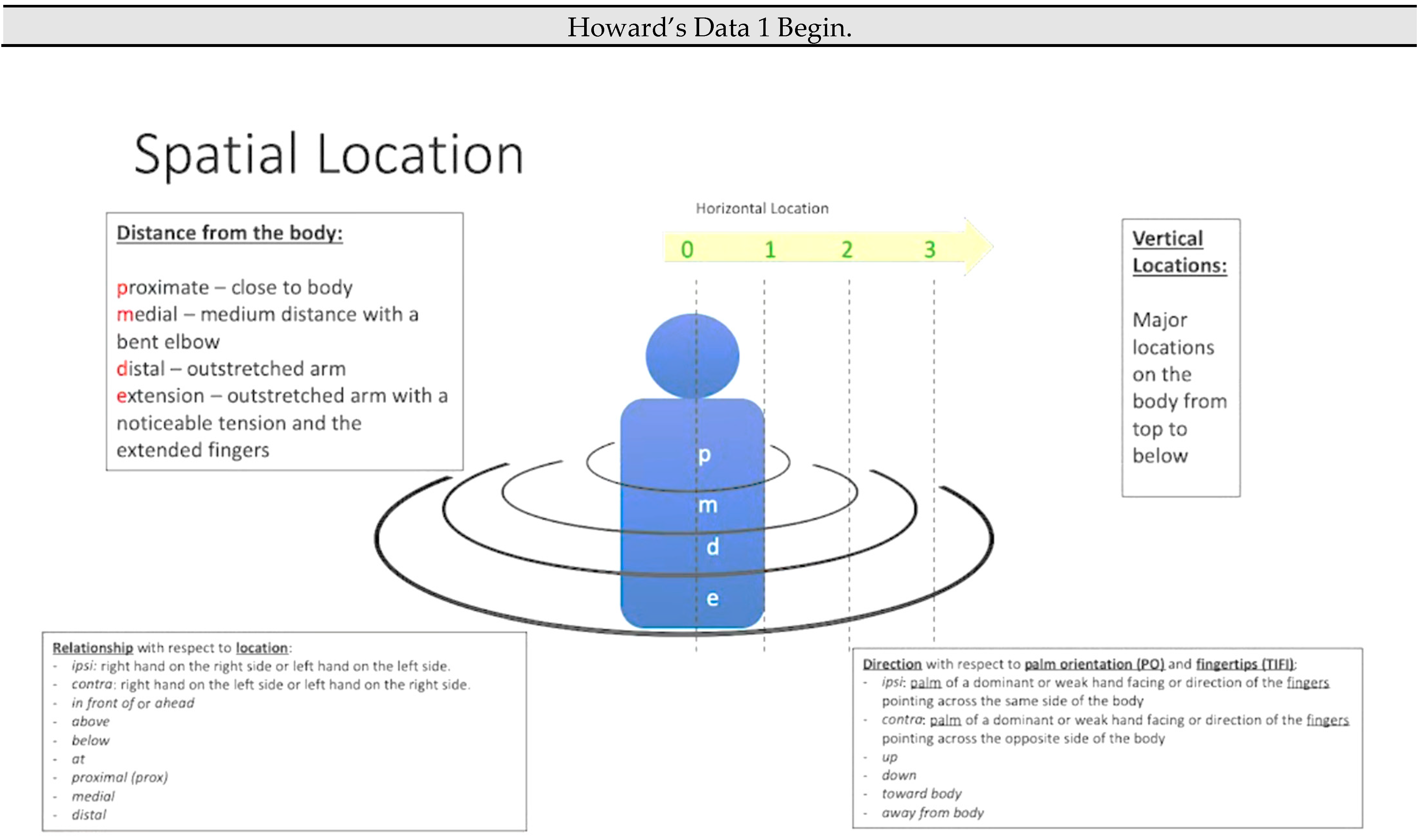

| Howard commented: The diagram represents ASL’s embodied spatial locations and body production sites. I designed it to visualize ASL morphemes like palm orientation, touch sites, and physical movements. The diagram represents spatial location in 2D. In addition to changing the form of knowledge, I simplified and reduced complexity and simplified the dimensions. |

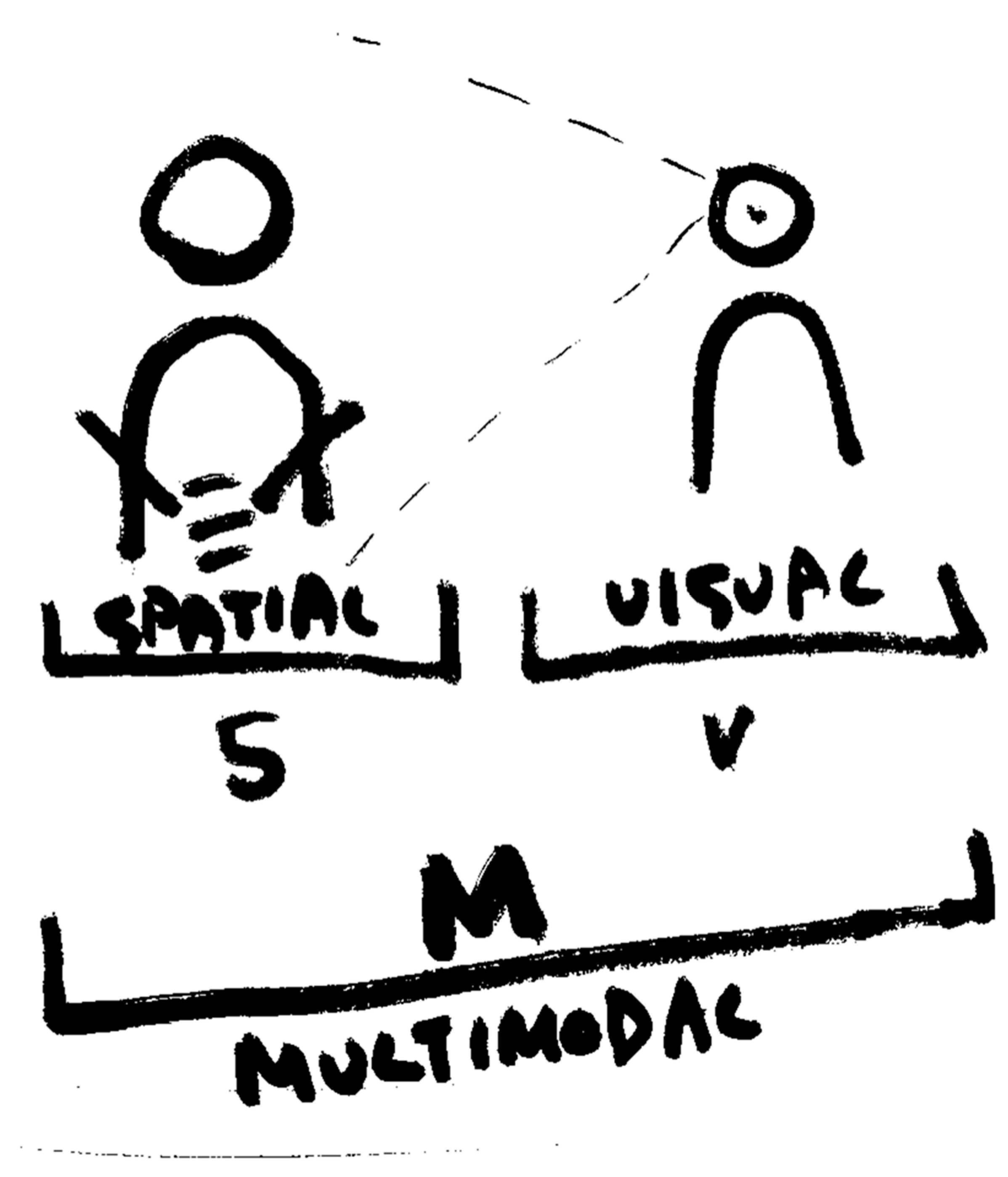

| I considered Howard’s diagram and narrative, then, constructed a drawing of my own (Figure 3, below). After, I wrote a memo to illustrate what I thought to be three primary kinds of knowledge: spatial, visual, and multimodal for two deaf agents engaged in a simple sign language educational interaction. These comprise an early draft of my theory of multimodal transduction, which explores four distinct forms of knowledge, each discussed in turn. |

| 1. SPATIAL knowledge |

| Like Howard’s tool, my sketch has icons representing people. On the left is a person signing in ASL, which is known for its embodied use of space as a form of knowledge. To know and use ASL is to describe signs in four spacetime dimensions. While ASL is temporal, here (as with Howard’s diagram), we pause time to focus on 3D axes: X, Y, and Z (height, width, depth). Simply, to sign in ASL is to use SPATIAL and embodied knowledge in language production. |

| 2. VISUAL knowledge |

| To the right is a second person, whose gaze rests on the signer at left. The icon is labeled VISUAL for its use of visual sensory systems to learn from spatial-embodied knowledge. The optic system “flattens” 3D signs into 2D neurological visual images. If signing production (“describing”) is spatial, then reading signs (“descrying”) by other agents is primarily a visual phenomenological event. Howard’s tool is also VISUAL. It reduces complexity by flattening 3D ASL production to a 2D surface. The visual tool eliminates the dimension of “time”, further simplifying the information exchange. |

| 3. MULTIMODAL knowledge | |

| A bracket connects SPATIAL and VISUAL. The bracket classifies the total interaction as MULTIMODAL. Multimodality combines spatiality and visuality and much more. Multimodality refers to the supersystem in which spatial and visual interactions co-occur. More explicitly, deaf multimodality is social and cognitive and dependent on human perceptual and cultural relationships and uses for specific modes (epistemology) that frequently undergo states of change affecting reality (ontology), in which forms are changed but meaning is conserved. This requires multimodal transduction. | |

| 4. Knowledge via MULTIMODAL TRANSDUCTION | |

| For an observing teacher, student, or researcher, spatial-embodied ASL knowledge is perceived as visual, whereas for the signer, it is perceived as spatial/embodied. Both are correct, relative to the point of view. This shows that Howard’s pedagogy is multimodal overall and requires numerous forms of transduction that supersede language-based changes. MT is an interaction; it makes explicit linkages both across and between sets of modes; this distinction obviates the change of mode beyond language. By establishing relationships among discourse forms in pedagogical interactions, both knowledge and reality changes. How it changes is different for Howard and for his students as relative to perspective and agent position. Likewise, educational forces, such as power and self-determination, are relevant in spurring the operation. This is what prompted Howard to make the tool—an ethical urge to support equity and redress inequality. | |

| Howard’s Data 1 End | (ELICITATION TASK, FIELD NOTE, p. 8) |

4.3.3. Implications

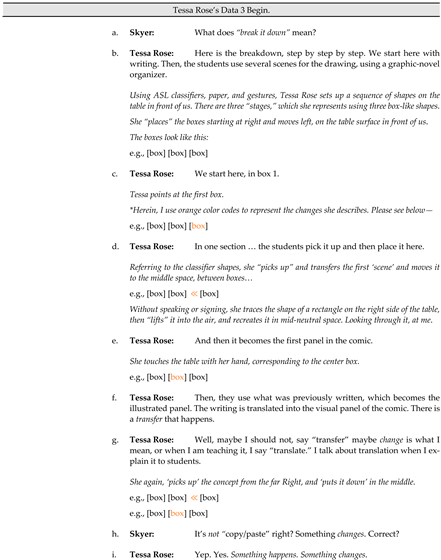

4.4. Case-Analysis 3—Tessa Rose

4.4.1. Main Claim

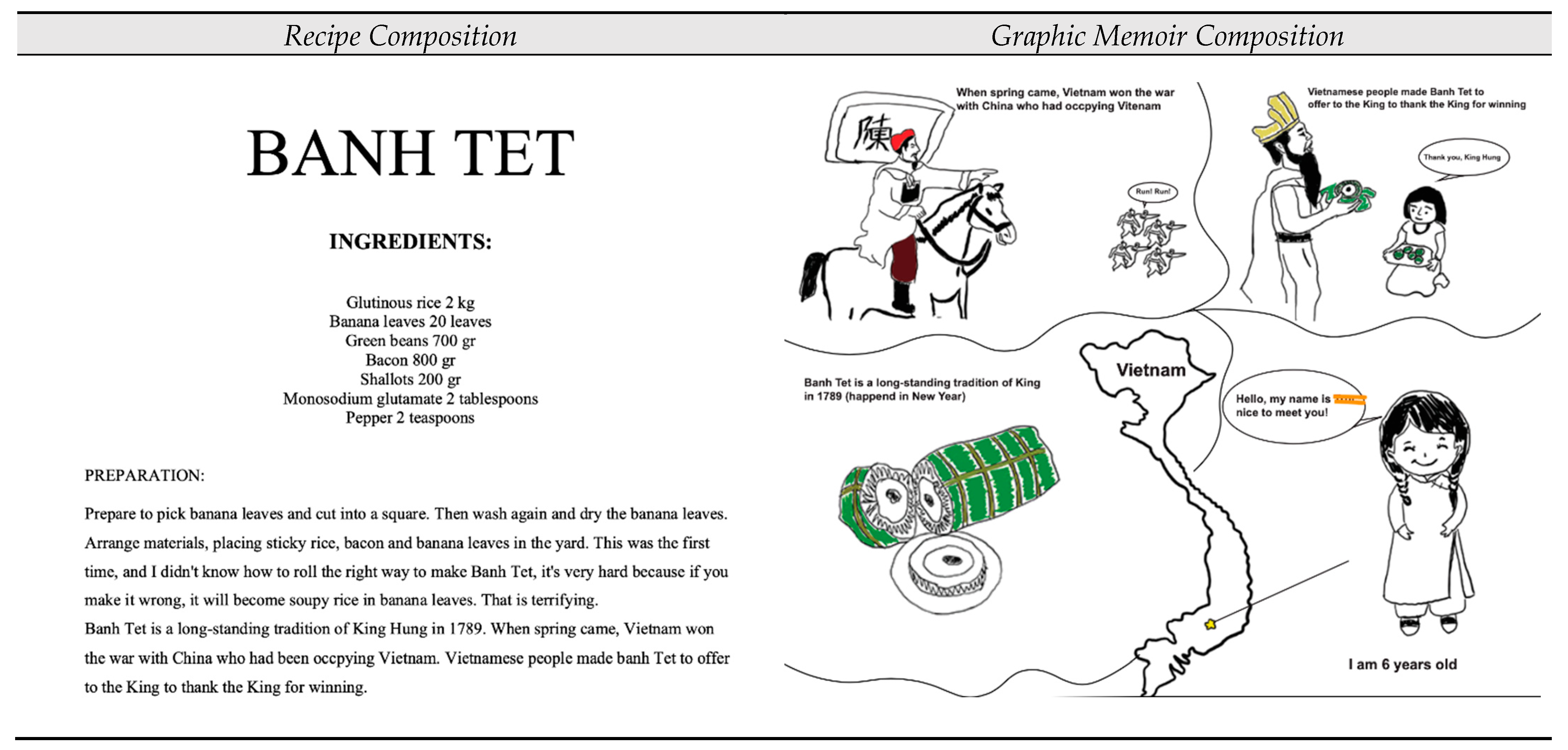

4.4.2. Evidence

I see this [MT] change as an expansion/distillation dynamic—breathing in and out, almost—[because] often ASL into English requires added language—expansion—English into ASL requires a distillation of meaning—almost like going from prose to poetry—keeping the essential oil if you will—ASL into drawing could be a much closer adaptation/translation = from poem to poem, almost—from ideogrammatic language to ideogrammatic language—so more “word for word” in a way [it requires a] cinematic grammar [in the way that H.D-L.] Bauman [writes about].

I could have scanned the materials into a PowerPoint, but I didn’t for at least two reasons: First that it was just not doable in a way that would preserve the sensory information that I wanted to share with them, and second, it would be too time consuming and [would] not [be] worth the effort.

4.4.3. Implications

5. Discussion

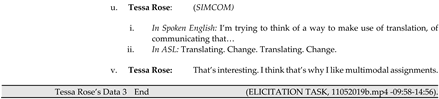

5.1. Theorizing Multimodal Transduction

5.2. Disambiguating Multimodal Transduction

5.3. Language Transduction: Four Modal Logics

[Chaining identifies] the ways that ASL and English interact with each other in various forms. Specifically:

- how teachers make connections between signing and print

- how teachers introduce/talk about English words

- how teachers use fingerspelling and initialized signs

- how teacher[s] introduce new words/concepts

- how teachers use different media to [connect ASL] with print

- other types of language interplay that teachers use (p. 87).

5.4. Communication Transduction: Four Modal Logics

5.5. Situating MT and Translanguaging in Deaf Pedagogies

5.5.1. Linguistic Overdetermination and Multimodal Superfusion

Originally, translanguaging described [how] a minority language was used in the classroom along with a majority language (Lewis et al. 2012), but since then, it has become a ‘terminological house with many rooms;’ (Jaspers 2018, p. 2). An often-cited recent definition is that translanguaging is ‘the deployment of a speaker’s full linguistic repertoire without regard for the watchful adherence to the socially and politically defined boundaries of named…languages (Otheguy et al. 2015). Garcia and Lin (2016, p. 19) suggested that we are witnessing a ‘translanguaging turn’ with the term now referring to both the complex language practices of plurilingual individuals and communities, as well as the pedagogical approaches that use those complex practices…Translanguaging is currently used in both descriptive and prescriptive ways. It can be used to refer to a bilingual pedagogy, multilingual spontaneous language practices, everyday cognitive processes, a theory of language in education, as well as a process of personal and social transformation” (p. 893).

5.5.2. Reclassifying Translanguaging as Multimodal Transduction

6. Limitations and Applications

6.1. Limitations and Transferability of MT

6.2. Limitations of Translanguaging

6.3. On Discourse and Axiology

7. Conclusions about Deaf Pedagogies of Multimodal Transduction

7.1. MT Is Literally and Metaphorically Transformative

7.2. Situated Deaf Pedagogies

7.3. On Disability

7.4. Use-Value of Multimodal Transduction

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The citations with “ALL CAPS” formatting are references to the dataset. These are included for the purpose of data audits. |

| 2 | Some are simple, others complex. Many may occur bidirectionally. To use the first as an example, a print word may become an image, but an image may also be likened to a word, and so forth. |

| 3 | Aside from the pedagogic, MT includes “exotic” processes such as: synesthesia, phronesis, ekphrasis, and aisthesis. Synesthesia is sensory to sensory crossover, as discussed by Kress and C. Spence; where, for example, one can see sounds or taste colors. Phronesis is the change from theoretical to practical knowledge guided by ethics, as described by Aristotle and Flyvbjerg more recently; where, for instance, a student of education enacts a theory of social literacy in the classroom. Ekphrasis is the practice of changing a visual artform into words, as discussed by Plato in ancient times and, more recently, by critics such as C. Greenberg; where, for example, an educator shares a work of art and then describes its formal composition for novices. Aisthesis converts the umwelt to text, seen in Rancière and J. Morrell; where, for example Thomas Wolfe encodes robust sensual experiences into poetic, textual narratives. MT also includes transcription, translation, and yes, translanguaging. Among these disparate changes, only one process is constant: meaning is deconstructed then reconstructed—in a word—transduced. MT undergirds numerous epistemological operations and ontological functions present in and beyond deaf pedagogy. MT is motivated and purposeful; it is a processual, flexible continuum of nonlinear interactions that are emergent and contingent. |

References

- Althusser, Louis. 1962. Contradiction and overdetermination. In For Marx: Notes for An Investigation. Translated by B. Brewster. London: Penguin Press. Available online: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/works/formarx/althuss1.htm (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Baker, Colin. 2011. Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 5th ed. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Bagga-Gupta, Sangeeta. 2019. Languaging across time and space in educational contexts. Language studies and deaf studies. Deafness and Education International 21: 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezemer, Jeff, and Carey Jewitt. 2010. Multimodal analysis: Key issues. In Research Methods in Linguistics. Edited by L. Litosseliti. London: Continuum, pp. 80–97. [Google Scholar]

- Boote, David N., and Penny Beile. 2005. Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educational Researcher 34: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon, Stephanie W., and Carrie Lou Garberoglio. 2017. Introduction. In Research in Deaf Education. Edited by Stephanie W. Cawthon and Carrie Lou Garberoglio. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Cherryholmes, Cleo H. 1999. Reading Pragmatism. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Kathee Mangan. 2010a. Where do we look? What do we see? A framework for ethical decision making in the education of students who are deaf or hard of hearing. In Ethical Considerations in Educating Children Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing. Edited by Kathee Mangan Christensen. Washington: Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Kathee Mangan, ed. 2010b. Ethical Considerations in Educating Children Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing. Washington: Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Grounded Theory, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- de Alba, Alicia, E. Gonzalez-Gaudiano, Colin Lankshear, and Michael Peters. 2000. Curriculum in the Postmodern Condition. New York: Lang. [Google Scholar]

- De Meulder, Maartje, Annelies Kusters, Erin Moriarty, and Joseph J. Murray. 2019. Describe, don’t prescribe. The practice and politics of translanguaging in the context of deaf signers. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural I 40: 892–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterbrooks, Susan R. 2017. Conceptualization, I, and application of research in deaf education: From phenomenon to implementation. In Research in Deaf Education. Edited by Stephanie Cawthon and Carrie Lou Garberoglio. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks, Susan R., and Melody Stoner. 2006. Using a visual tool to increase adjectives in the written language of students who are deaf or hard of hearing. Communication Disorders Quarterly 27: 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enns, Charlotte. 2017. Making the case for case studies in deaf education research. In Research in Deaf Education. Edited by Stephanie Cawthon and Carrie Lou Garberoglio. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 203–24. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia. 2009. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, and Angel M. Y. Lin. 2016. Translanguaging in bilingual education. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education; Bilingual and Multilingual Education. Edited by O. Garcia. New York: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, and Debra Cole. 2014. Deaf gains in the study of bilingualism and bilingual education. In Deaf Gain: Raising the Stakes for Human Diversity. Edited by H-Dirksen L. Bauman and Joseph J. Murray. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, and Li Wei. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism, and Education. London: Palgrave-MacMillian. [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo, Richard M., and Emily C. Bouck. 2021. Special Education in Contemporary Society, 7th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, James Paul. 2004. Situated Language and Learning: A Critique of Traditional Schooling. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Glickman, Neil S., and Wyatte C. Hall. 2019. Language Deprivation and Deaf Mental Health. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Patrick J. 2015. Examining the need of attention strategies for academic I in deaf and hard of hearing children. Journal of Education and Human I 4: 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardino, Caroline, Jennifer S. Beal, Joanna E. Cannon, Jenna Voss, and Jessica P. Bergeron. 2018. Case Studies in Deaf Education: Inquiry, Application, and Resources. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, Sanjay. 2019. Language deprivation syndrome. In Language Deprivation and Deaf Mental Health. Edited by Neil S. Glickman and Wyatte C. Hall. New York: Routledge, pp. 24–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, Robert, and Gunther Kress. 1988. Social Semiotics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb, Leala, Hannah M. Dostal, and Gloshanda Lawyer. 2021. Translanguaging Resources: An Informational Guide. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Holmström, Ingela, and Krister Schönström. 2018. Deaf lecturers’ translanguaging in a higher education setting. A multimodal multilingual perspective. Applied Linguistics Review 9: 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, Tom, and Francine MacDougall. 2000. Chaining’ and other links: Making connections between American Sign Language and English in two types of school settings. Visual Anthropology Review 15: 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, Jürgen. 2018. The Transformative Limits of Translanguaging. Language & Communication 58: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt, Carey. 2008. Multimodal discourses across the curriculum. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2nd ed. Vol. 3: Discourse and Education. Edited by M. Martin-Jones, A. M. de Mejia and N. H. Hornberger. Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Knoors, Harry, and Marc Marschark. 2014. Teaching Deaf Learners. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Konecki, K. T. 2011. Visual grounded theory: A methodological outline and examples from empirical work. Revija za Sociologiju 41: 131–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, Gunther R. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunther R. 2011. Discourse analysis and education: A multimodal social semiotic approach. In Critical Discourse Analysis in Education, 2nd ed. Edited by Rebecca Rogers. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunther R., and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntze, Marlon. 2016. Code-switching. In SAGE Deaf Studies Encyclopedia. Edited by G. Gertz and P. Boudreault. New York and London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntze, Marlon, and Debbie Golos. 2021. Revisiting rethinking literacy. In Discussing Bilingualism in Deaf Children: Essays in Honor of Robert Hoffmeister. Edited by Charlotte Enns, Jonathan Henner and Lynn McQuarrie. New York: Routledge, pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntze, Marlon, Debbie Golos, and Charlotte Enns. 2014. Rethinking literacy: Broadening opportunities for visual learners. Sign Language Studies 14: 203–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, Christopher, Debbie Golos, Lon Kuntze, Jonathan Henner, and Jessica Scott. 2021. Guidelines For Multilingual Deaf Education Teacher Preparation Programs. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kusters, Annelies, Massimiliano Spotti, Ruth Swanwick, and Elina Tapio. 2017. Beyond languages, beyond modalities: Transforming the study of semiotic repertoires. International Journal of Multilingualism 14: 219–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, Annelies Maria Jozef, and Michele Ilana Friedner. 2015. Introduction: Deaf-same and difference in international deaf spaces and encounters. In It’s a Small World: International Deaf Spaces and Encounters. Edited by Michele Friedner and Annelies Kusters. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, pp. ix–xxx. [Google Scholar]

- Kusters, Marieke. 2017. Intergenerational responsibility in deaf pedagogies. In Innovations in Deaf Studies: The Role of Deaf Scholars. Edited by Annelies Kusters, Maartje De Meulder and Dai O’Brien. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh, Irene W., and Jean F. Andrews. 2017. Deaf People and Society: Psychological, Sociological, and Educational Perspectives, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Gwyn, Bryn Jones, and Colin Baker. 2012. Translanguaging: Origins and I form school to street and beyond. Educational Research and Evaluation 18: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckner, John L. 2018. Foreword. In Case Studies in Deaf Education: Inquiry, Application, and Resources. Edited by Caroline Guardino, Jennifer S. Beal, Joanna E. Cannon, Jenna Voss and Jessica P. Bergeron. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lupi, Giorgia. 2016. From language to representation. In Mind, Maps, and Infographics. New York: Moleskine. [Google Scholar]

- Marschark, Marc, Allan Paivio, Linda J Spencer, Andreana Durkin, Georgianna Borgna, Carol Convertino, and Elizabeth Machmer. 2017. Don’t assume deaf students are visual learners. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 29: 153–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, Catherine, and Gretchen B. Rossman. 2016. Designing Qualitative Research, 6th ed. New York: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, Donna M. 2020. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology, 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, Matthew B., A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldana. 2020. Qualitative Data Analysis, 4th ed. New York: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Moges, Rezenet Tsegay. 2020. From White Deaf people’s adversity to Black Deaf Gain: A proposal for a new lens of Black Deaf educational history. Journal Committed to Social Change on Race and Ethnicity 6: 69–99. [Google Scholar]

- Moges-Riedel, R., S. Garcia, O. Robinson, S. Siddiqi, A. Lim Franck, K. Aaron-Lozano, S. Pineda, and A. Hayes. 2020. Open Letter in ASL about Intersectionality. [Video]. YouTube. Available online: https://youtu.be/JcTYXpofAI0 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Ortega, Lourdes. 2009. Understanding Second Language Acquisition. London: Hodder & Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia García, and Wallis Reid. 2015. Clarifying Translanguaging and Deconstructing Named Languages: A Perspective from Linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review 6: 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, Claudia M., and Christopher Kurz. 2021. Using ASL to navigate the semantic circuit in the bilingual math classroom. In Discussing Bilingualism in Deaf Children: Essays in Honor of Robert Hoffmeister. Edited by Charlotte Enns, Jonathan Henner and Lynn McQuarrie. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Perniss, Pamela. 2015. Collecting and analyzing sign language data: Video requirements and use of annotation software. In Research Methods in Sign Language Studies. Edited by Eleni Orfanidou, Bencie Woll and Gary Morgan. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Donna Kalmbach, and Kevin Carr. 2014. Becoming a Teacher through Action Research: Process, Context, and Self-Study, 3rd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, Robert Q., and Meghan L. Fox. 2019. Forensic evaluation of deaf adults with language deprivation. In Language Deprivation and Deaf Mental Health. Edited by Neil S. Glickman and Wyatte C. Hall. New York: Routledge, pp. 101–35. [Google Scholar]

- Raike, Antti, Suvi Pylvänen, and Päivi Rainò. 2014. Co-design from divergent thinking. In Deaf Gain: Raising the stakes for human diversity. Edited by H-Dirksen L. Bauman and Joseph J. Murray. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 402–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rancière, Jacques. 2010. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Rée, Jonathan. 1999. I See a Voice: Deafness, Language, and the Senses—A Philosophical History. New York: Metropolitan Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Gillian. 2012. Visual Methodologies. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, Oliver. 1990. Seeing Voices: A Journey into the World of the Deaf. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2012. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Schiff, Debra. 2010. Information Behaviors of Deaf Artists. Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 29: 44–47. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27949552 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Sfard, Anna. 1998. On two metaphors for learning and the dangers of choosing just one. Educational Researcher 27: 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, Laurene, Sharon Baker, and M. Diane Clark. 2013. The Standardized Visual Communication and Sign Language Checklist for Signing Children. Sign Language Studies 14: 101–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyer, Michael E. 2020. Invited article: The bright triad and five propositions: Toward a Vygotskian framework for deaf pedagogy and research. American Annals of the Deaf 164: 577–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyer, Michael E. 2021. Pupil ⇄ Pedagogue: Grounded Theories about Biosocial Interactions and Axiology for Deaf Educators. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Skyer, Michael E. 2022. Power in Deaf Pedagogy and Curriculum Design Multimodality in the Digital Environments of Deaf Education (DE2). Przegląd Kulturoznawczy (Arts and Cultural Studies Review) 3: 345–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyer, Michael E. 2023. The deaf biosocial condition: Metaparadigmatic lessons from and beyond Vygotsky’s deaf pedagogy research. American Annals of the Deaf, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Skyer, Michael E., and Laura Cochell. 2020. Aesthetics, Culture, Power: Critical Deaf Pedagogy and ASL Video-Publications as Resistance-to-Audism in Deaf Education and Research. Critical Education 11: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Melissa Beth. 2010. Opening our eyes: The complexity of competing visual demands in interpreted classrooms. In Ethical Considerations in Educating Children Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing. Edited by Kathee Mangan Christensen. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snoddon, Kristin. 2017. Uncovering translingual practices in teaching parents classical ASL varieties. International Journal of Multilingualism 14: 303–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, Robert E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. London: SAGE publications. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, Robert E. 2005. Qualitative case studies. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, pp. 443–66. [Google Scholar]

- Swanwick, Ruth. 2017a. Languages and Languaging in Deaf Education: A Framework for Pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swanwick, Ruth. 2017b. Translanguaging, learning and teaching in deaf education. International Journal of Multilingualism 14: 233–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanwick, Ruth, and Marc Marschark. 2010. Enhancing education for deaf children: Research into practice and back again. Deafness and Education International 12: 217–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanwick, Ruth, Samantha Goodchild, and Elisabetta Adami. 2022. Problematizing translanguaging as an inclusive pedagogical strategy in deaf education. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapio, Elina. 2013. A Nexus Analysis of English in the Everyday life of FinSL Signers: A multimodal View on Interaction. Doctoral Dissertation, University, Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Thoutenhoofd, Ernst D. 2010. Acting with attainment technologies in deaf education: Reinventing monitoring as an intervention collaboratory. Sign Language Studies 10: 214–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, Stefan, and Iddo Tavory. 2012. Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory 30: 167–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, Lev Semyonovich. 1993. The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky: The Fundamentals of Defectology (Abnormal Psychology and Learning Disabilities). New York: Plenium Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Li. 2018. Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics 39: 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Li. 2022. Translanguaging as method. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics 1: 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Li, and Ofelia García. 2022. Not a first language but one repertoire. Translanguaging as a decolonizing project. RELC Journal 52: 313–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Alys, and Bogusia Temple. 2014. Approaches to Social Research: The Case of Deaf Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

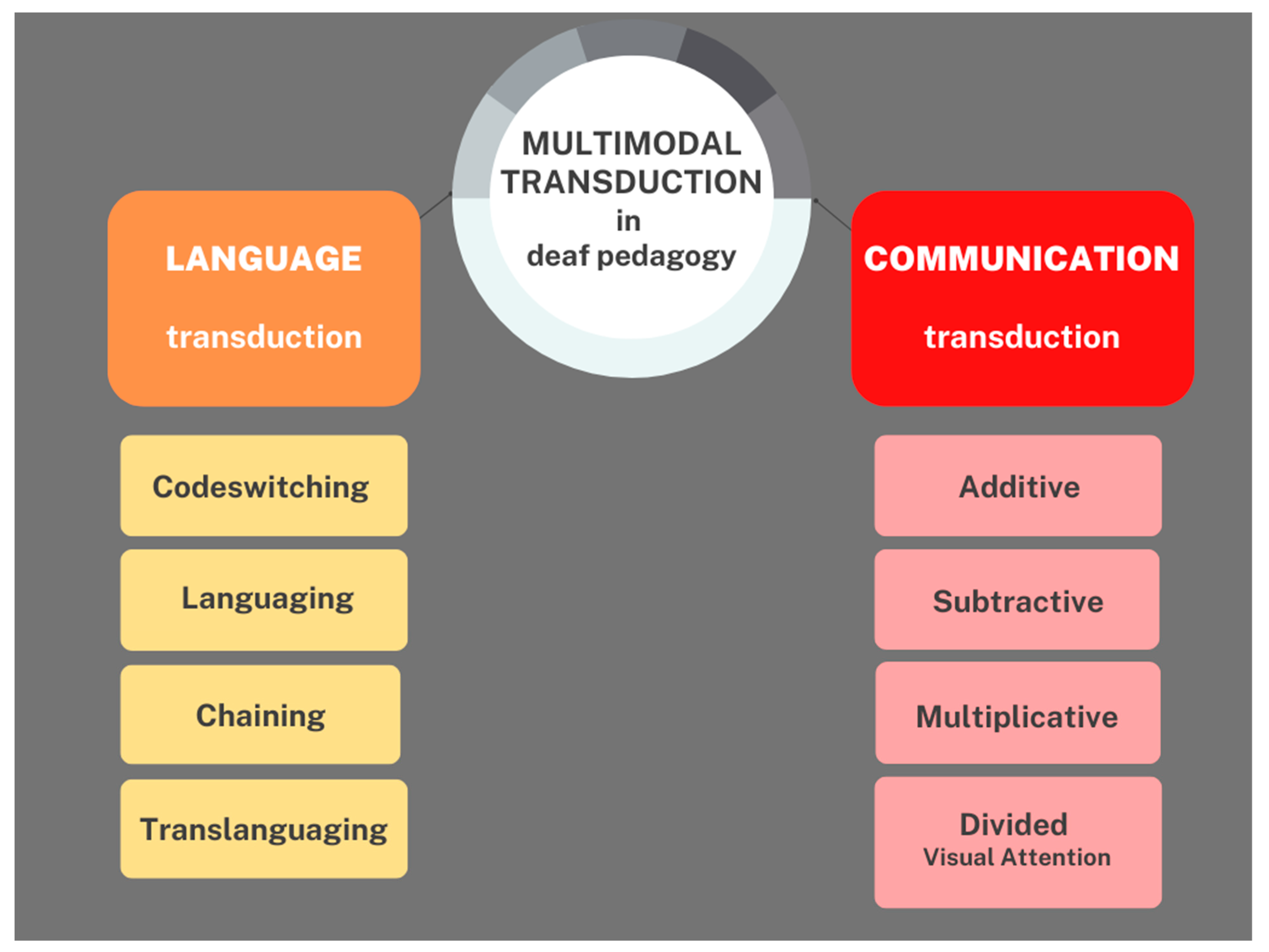

| Modal Logic: | Additive | Subtractive | Multiplicative | Divided Visual Attention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Deaf agents add one or more new mode/s or multimodal assemblages in a slow, methodical fashion. | Deaf agents purposefully remove single or multiple modes, or reduce the intensity or volume of multimodal assemblages. | Deaf agents deploy multiple modes or several assemblages quickly by means of simultaneous or near-simultaneous events. | Deaf agents divorce or disaggregate complex multimodal assemblages into components or split their gaze resources purposefully. |

| Purpose | …to increase explanatory power with the addition of new modes or to conserve time or effort. | …to augment reality or change knowledge forms by reducing dimensions or to clarify a salient concept using fewer modes. | …to simulate the depth, breadth, and intensity of multiple senses acting in concert or to simulate a complex, multimodal reality. | …to emphasize relationships between plural entities, including as an overt analysis of language-based or communication-based multimodal assemblages. |

| Corpus Examples | 1. Louis draws an arrow between two columns of biochemical data, drawing his students’ focus to links between data in one column and an applied mathematical formula in the second column. 2. Through elaborate, multimodal dialogues and social critical thinking, Astoria and her students create a new drawing using visual design principles to depict spatial arrangements, sourced from a text. | 1. Sarah Jo comments: English is 2D and linear, whereas ASL is 3D and spatial. She explains, textual language imposes limits on expansive discursive dimensions that are latent in ASL. 2. Howard disembodies and schematizes ASL modes using visual tools he designed to reduce the number and intensity of embodied modes students encounter at one time. | 1. Edward’s video lecture uses text, sign, image, speech, layout, the movement of the body in physical space [MOTBIPS], gesture, visual tools, and other modes in concert. 2. Tessa Rose’s table lecture deploys numerous graphic memoirs in various stages of completion. She prompts students to “look, look, look,” then, guides the students in multimodal analysis. | 1. Sarah Jo’s student uses a smartphone app to translate and decode her English instructions by using traditional Chinese pictographic characters. 2. Edward’s student sits with a notebook and his textbook to the left of his computer monitor; as he manipulates the visual tool software suite, he also refers back to his hand-constructed visual tools and textual notes in a lengthy cycle of learning. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skyer, M.E. Multimodal Transduction and Translanguaging in Deaf Pedagogy. Languages 2023, 8, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020127

Skyer ME. Multimodal Transduction and Translanguaging in Deaf Pedagogy. Languages. 2023; 8(2):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020127

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkyer, Michael E. 2023. "Multimodal Transduction and Translanguaging in Deaf Pedagogy" Languages 8, no. 2: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020127

APA StyleSkyer, M. E. (2023). Multimodal Transduction and Translanguaging in Deaf Pedagogy. Languages, 8(2), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020127