Linguistic Repertoires: Modeling Variation in Input and Production: A Case Study on American Speakers of Heritage Norwegian

Abstract

1. Introduction

[H]eritage and L2 grammars are frequently described as ill-conceived versions of […] artificial gold standards based on idealized L1 […] monolingual grammars […]. From an MG perspective [however] all grammars are created equal. Each individual will have a grammar with a unique configuration of rules, and these individual configurations may converge or diverge from what is considered standard in a given language by different social groups. However, an individual grammar is never deficient in any way.

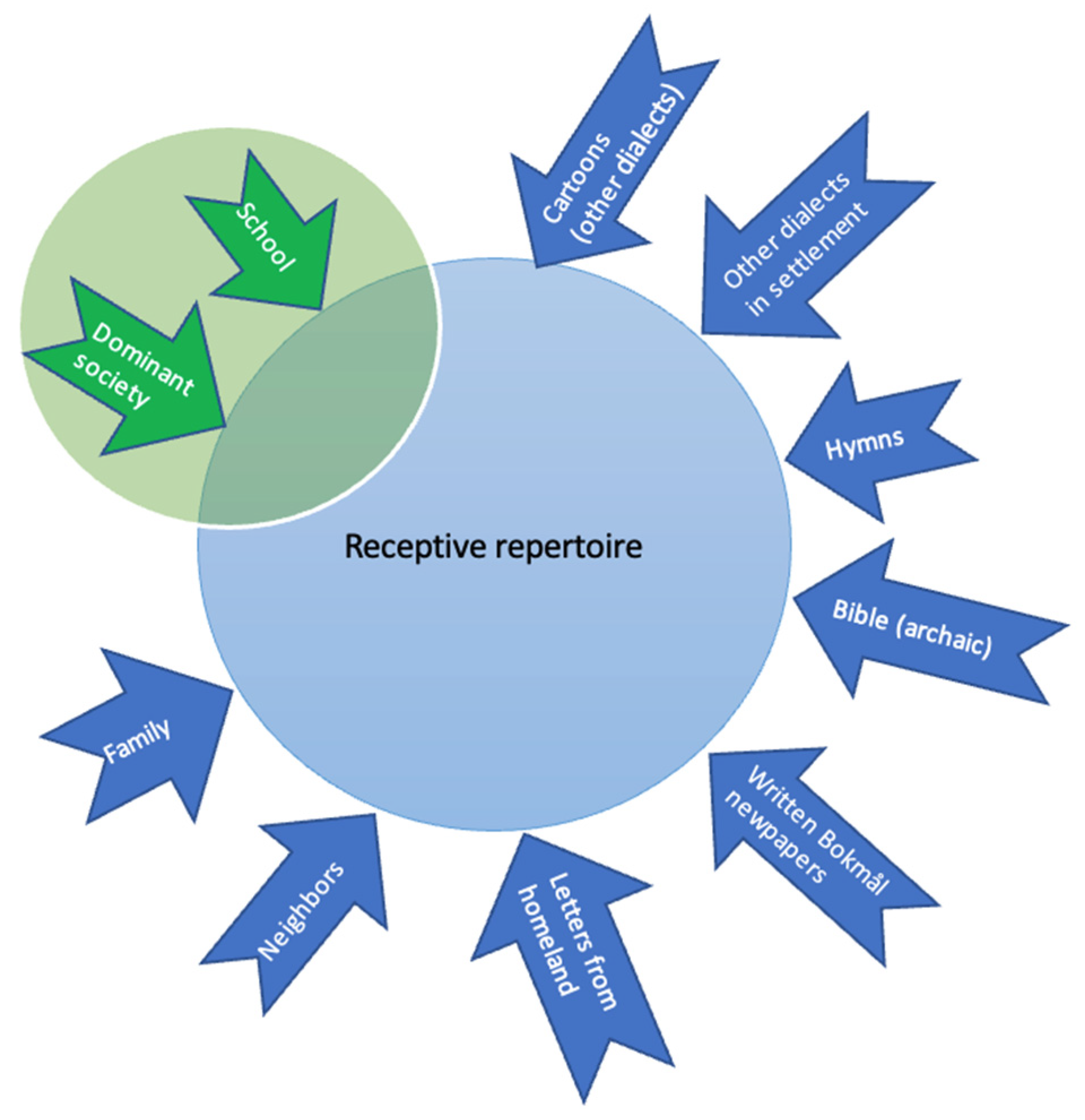

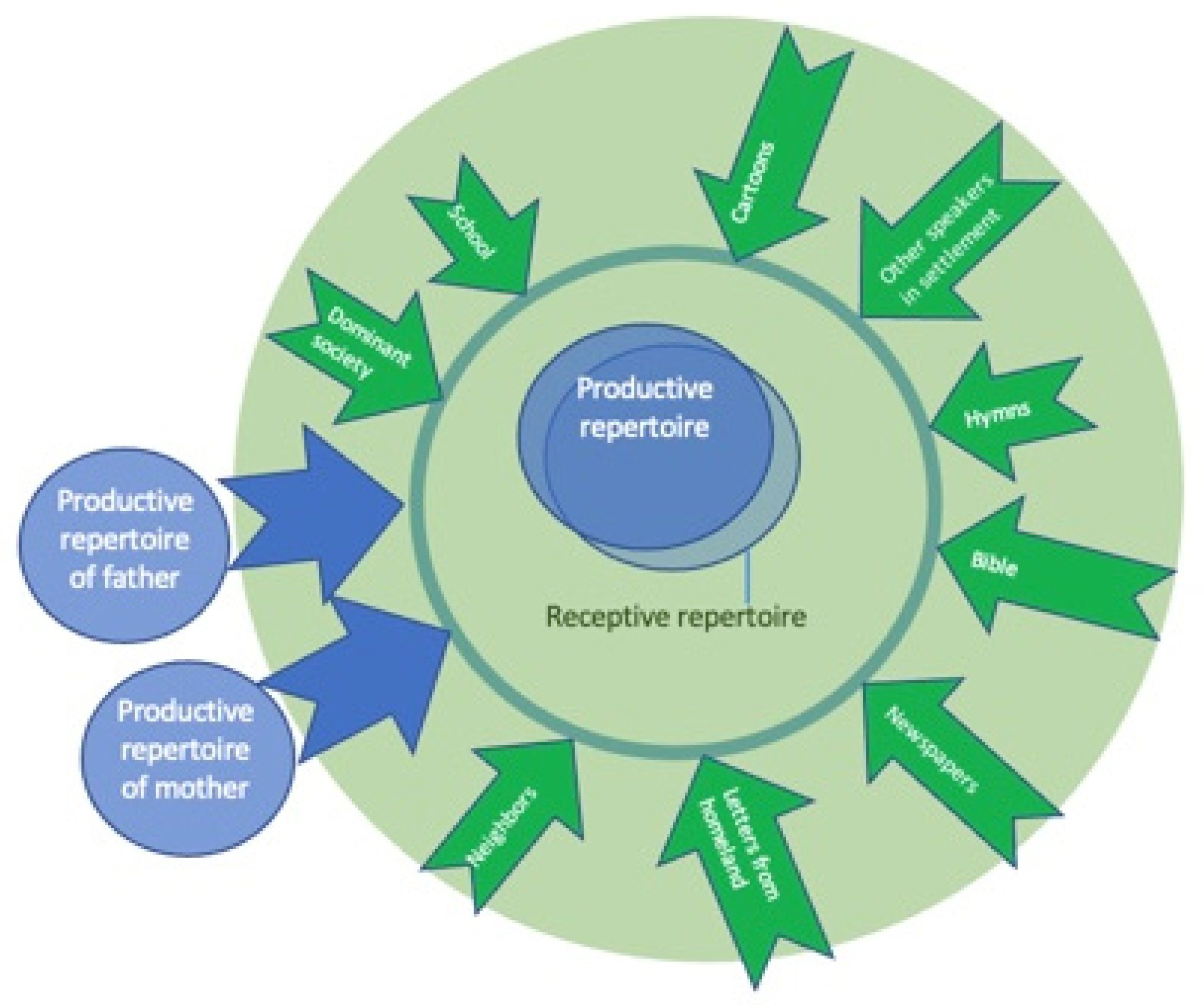

[R]educed input quality–in addition to reduced quantity–appears to play a central role in the unique outcomes of heritage speakers. The causes behind this effect remain to be explored, but Gollan et al. (2015) suggest that richer variety in the input could lead to more robust encoding of the relevant representations.

2. Studying Norwegian Immigrants in the American Midwest: Language and Society

2.1. Rural Settlements and Close-Knit Communities

There is a strong loyalty to the community and a correspondingly strong social pressure against any deviation from the accepted local pattern. What foreign elements have come in have either been assimilated completely to the cultural pattern of the community or they have been isolated socially until they preferred to leave.

The shell is still Norwegian, but the inward pattern, the spirit of the thing, is American. This is Norwegian-American, the language of the Norwegian immigrant.

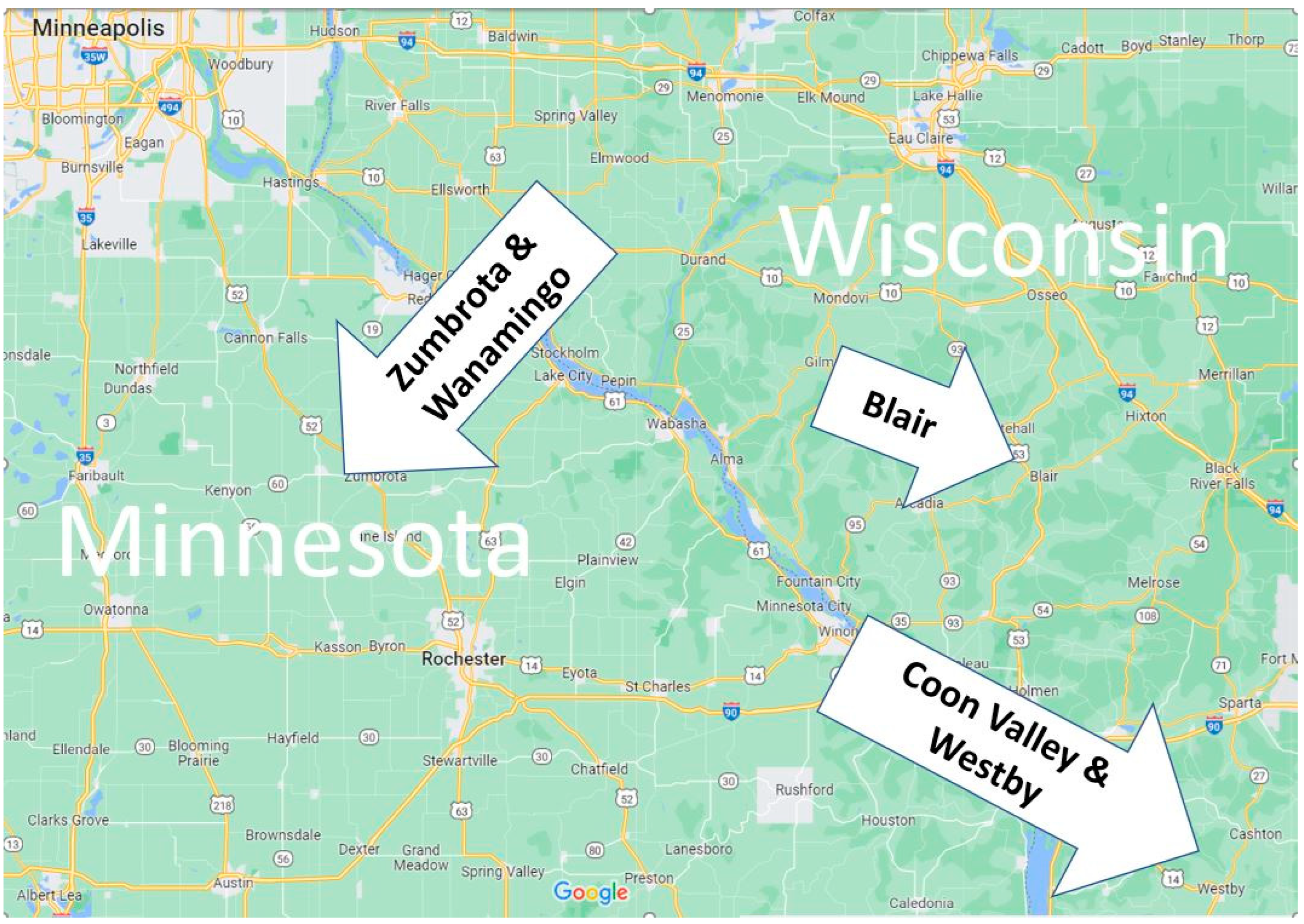

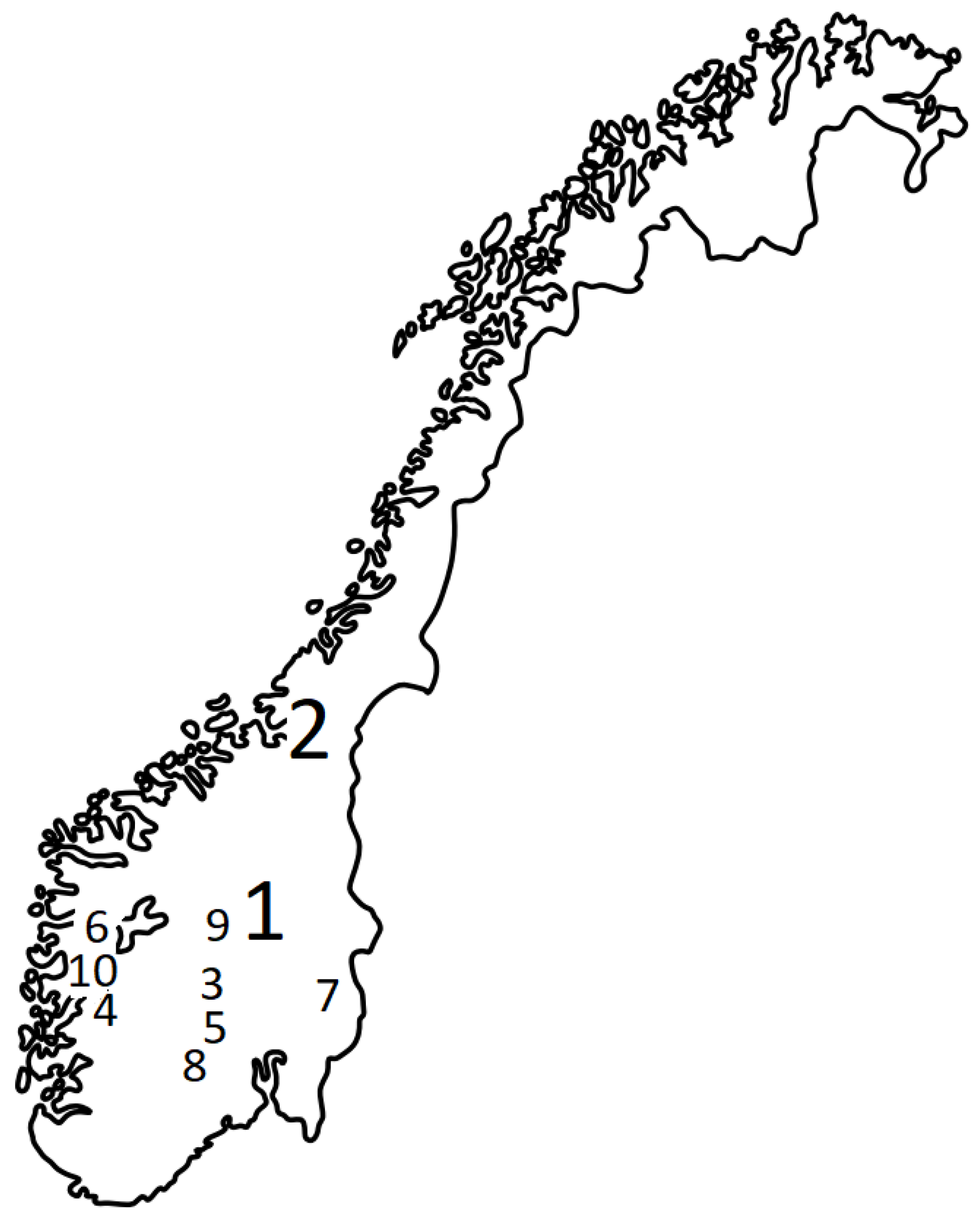

2.2. Selecting the Communities

3. Main Sources of Norwegian Input

3.1. The Local Spoken Dialect(s): Family, Neighbors and Settlement

3.2. Other Spoken Input: Church and Confirmation

If the person was confirmed in the Norwegian language, she had to read and memorize entire religious texts. Therefore, she would be able to easily recite […] Bible verses, passages from sermons, and other religious phrases. The Norwegian language persisted longest when it came to matters of faith. Even if a person could attend school, conduct business, or read newspapers in English, their entire religious vocabulary was in Norwegian.

3.3. The Written (Standardized) Language: Lingering Conservatism

3.4. Sources of Input for Written Norwegian: Language Learning and Maintenance

4. The Data

4.1. Recordings and Idealized Cohorts

4.2. Selecting Linguistic Features for the Study

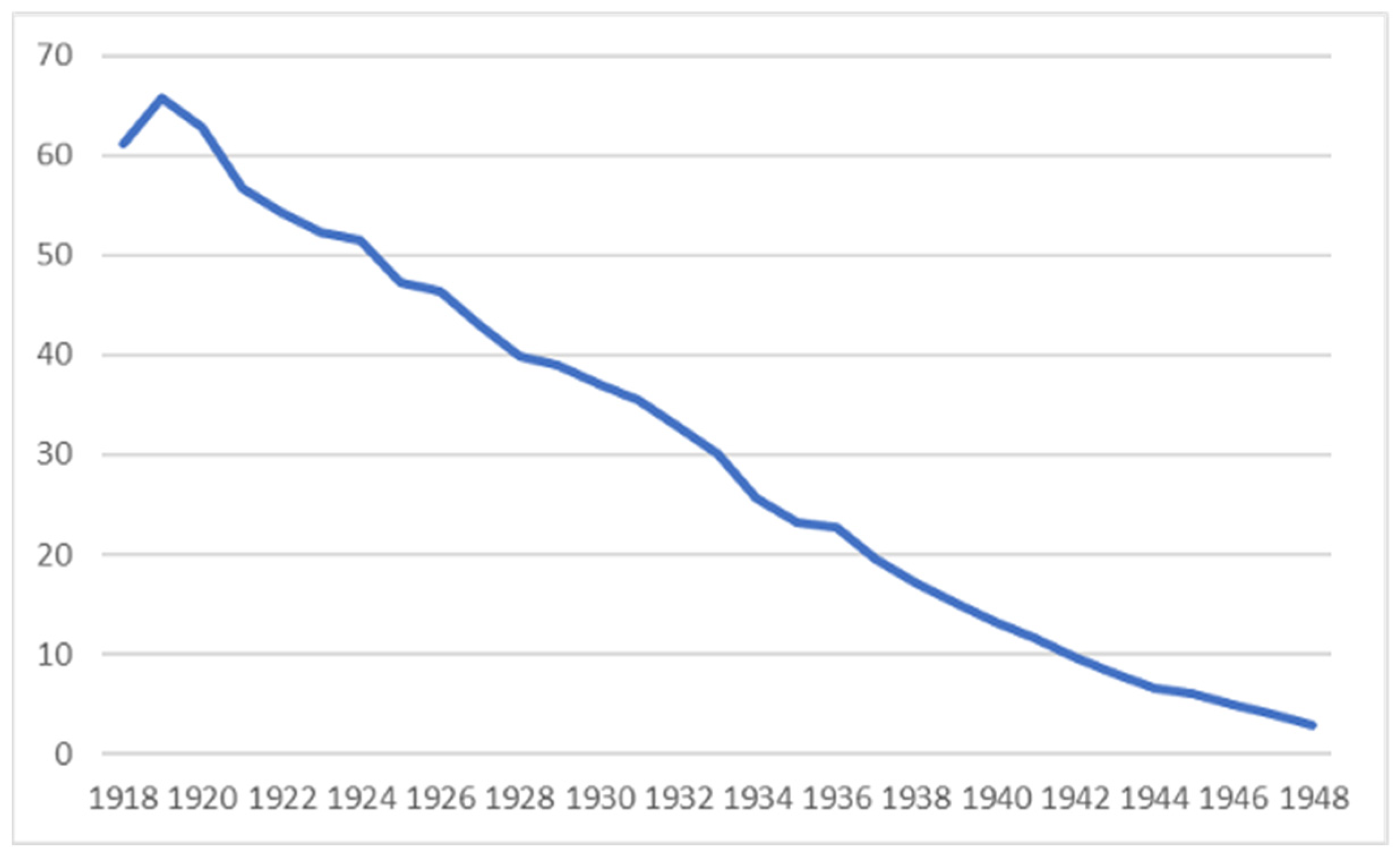

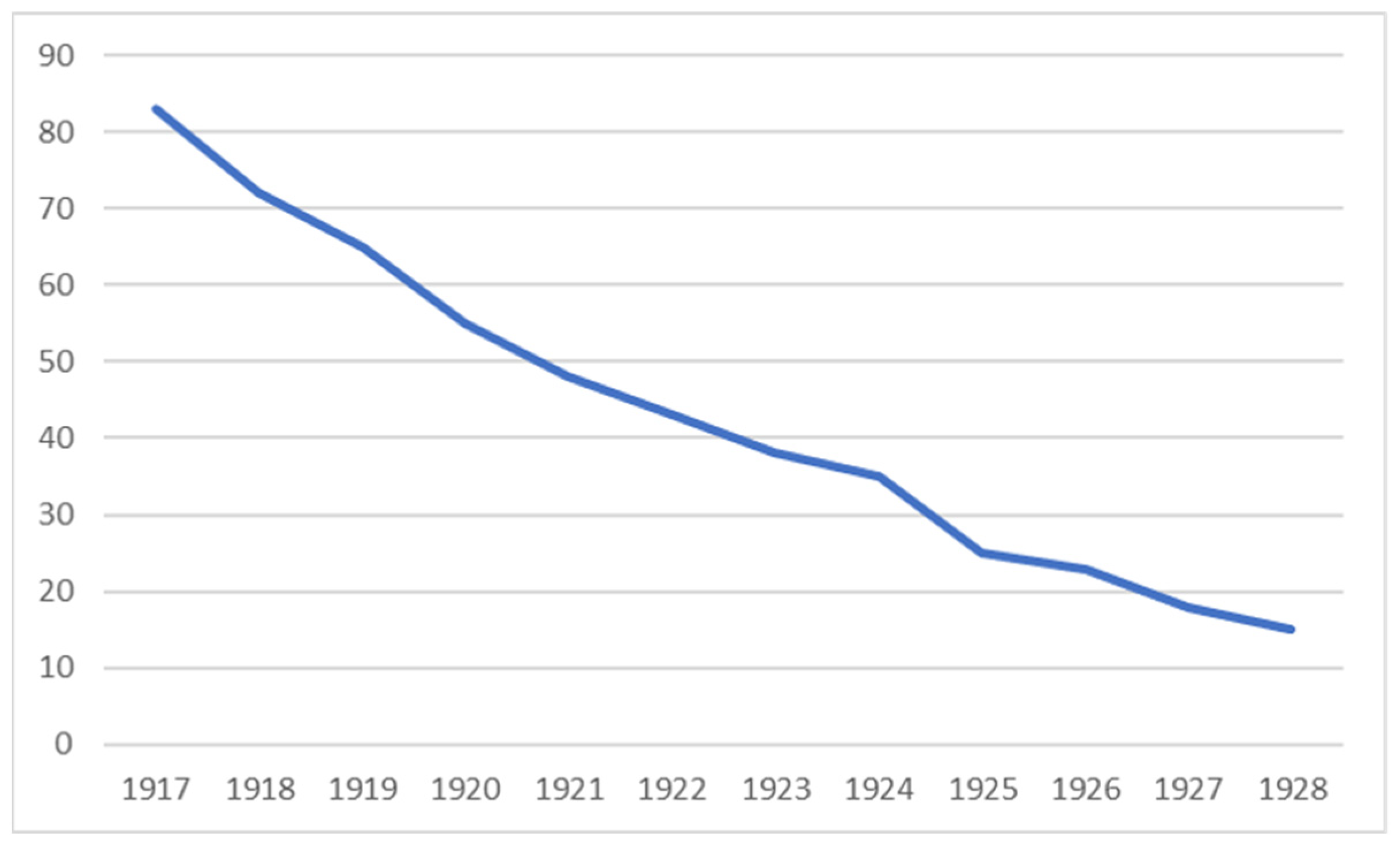

4.3. Morphological Paradigms: Productive Tense Suffixes of Loan Verbs

4.4. Intra-Phrasal Syntax: Prenominal and Postnominal Possessives

| (1) | min | hest |

| me.poss.def | horse | |

| ‘My horse’ | ||

| (2) | hest-en | min |

| horse.def | me.poss.def | |

| ‘My horse’ | ||

| Q1 | Hvordan | skal | vi | dra | til | byen? |

| How | shall | we | go | to | town | |

| ‘How will we go to town?’ | ||||||

| (3) | a. | *Vi | kan | ta | vår/VÅR | hest. |

| we | can | take | our | horse | ||

| ‘We can take our horse.’ | ||||||

| b. | Vi | kan | ta | hasten | vår. | |

| We | can | take | horse.def | our.poss.def. | ||

| ‘We can take our horse.’ | ||||||

| Q2 | Skal | vi | ta | hesten | vår | til | byen? |

| Shall | we | take | horse.def | our.poss.def | to | town | |

| ‘Should we take our horse to town?’ | |||||||

| (4) | a. | Nei | vi | tar | VÅR/*vår | hest |

| no | we | take | our | horse | ||

| ‘No, let’s take OUR horse.’ | ||||||

| b. | Nei | vi | tar | hesten | VÅR/*vår | |

| no | we | take | horse.def | our.poss.def | ||

| ‘No, let’s take OUR horse.’ | ||||||

4.5. Inter-Phrasal Syntax: Topicalization and Verb Movement

| (5) | Nå | går | vi | ferbi | hår | je | vaks | opp |

| now | walk | we | past | where | I | grew | up | |

| ‘Now let’s walk past the place where I grew up.’ | ||||||||

| (6) | Der | dem | lager | vin |

| Now | walk | we | past | |

| ’There they make wine’ | ||||

5. Modeling Multilingualism and Linguistic Change

It remains to be emphasized that linguistic diversity begins next door, nay, at home and within one and the same man […]. What we heedlessly and somewhat rashly call ‘a language’ is the aggregate of millions of such microcosms many of which evince such aberrant linguistic comportment that the question arises whether they should not be grouped into other ‘languages’.

[E]very human being speaks a variety of languages. We sometimes call them different styles or dialects, but they are really different languages, and somehow we know when to use them, one in one place and another in another place. Now each of these different languages involves a different [“grammar”].27

5.1. Receptive and Productive Repertoire

The language of our children is almost exclusively English, but they understand every word spoken to them in Norwegian; it is hard to teach the children Norwegian in this country, as English comes more naturally to them.31

| (7) | Helliget | vorde | Dit | Navn | |

| holy.made | be.SUBJ | Your | name | ||

| ‘Hallowed be Thy name.’ | |||||

| (8) | Komme | Dit | Rike | ||

| come.SUBJ | Your | kingdom | |||

| ‘Thy kingdom come.’ | |||||

| (9) | i Evighet | Vær | hos | oss | og | vår | Sjæl | bered |

| In eternity | be | with | us | and | our | soul | prepare | |

| ‘Be with us in eternity and prepare our soul’ | ||||||||

| (10) | At | Gud | vi | søke | Nåde | få | |

| That | God | we | seek | mercy | receive | ||

| ‘that we seek God, receive mercy’ | |||||||

| (11) | I | våre | Synder | la | oss | ei | forgå! |

| In | our | sins | let | us | not | perish | |

| ‘Do not let us perish in our sins’ | |||||||

5.2. Selecting the Productive Repertoire: “Somehow We Know When to Use Them…”

Your accent carries the story of who you are–who first held you and talked to you when you were a child, where you have lived, your age, the schools you attended, the languages you know, your ethnicity, whom you admire, your loyalties, your profession, your class position: traces of your life and identity are woven into your pronunciation, your phrasing, your choice of words. Your self is inseparable from your accent.

[T]here is pressure on the bilingual to simplify the selection procedure by reducing the degree of separation between the two subsets of the repertoire [. W]e might view the replication of patterns as a kind of compromise strategy that […] reduce[s] the load on the selection […] mechanism by allowing patterns to converge, thus maximizing the efficiency of speech production in a bilingual situation.

5.3. How Individual Choices Accumulate and Affect the Input for the Next Generation

Contextual diversity leads to greater ease of retrieval in single-word recognition (and reading aloud) to a greater extent than does frequency of use […], and similarly, use of an HL in different places, with different people at different times of day, and in different locations may be more important to achieving proficient HL word production than the number of exposures to HL words.

Different speakers talk in different ways, and interaction with a variety of speakers will likely result in exposure to a broader variety of accents, speech rates, and syntactic structures and a larger number of HL words. Alternatively, using the HL with a greater number of speakers may lead to a greater diversity of contexts with which the HL words are associated.

6. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | We use the term repertoires instead of register to avoid the latter’s association with vocabulary. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | In most normal acquisition situations, the preferred linguistic role model for a child will be its playmates and slightly older peers; hence, a child usually acquires the dialect or language of the local children. In the case of heritage language, this type of input is often lacking; hence, the input from parents becomes much more important. |

| 4 | We are specifying North American here since there are currently ongoing projects and fieldworks of Norwegian South-American Heritage language (NorSAHL), and Norwegian Heritage Language in Spain (NorSpaHL). Cf. the home pages of the NorAmDiaSyn–Norwegian in America project that was led by Janne Bondi Johannessen at the University of Oslo http://www.tekstlab.uio.no/nota/NorAmDiaSyn/english/index.html (accessed on 3 August 2022) and the new project Norwegian across the Americas led by Kari Kinn, University of Bergen. https://www.uib.no/en/lle/134611/norwegian-across-americas (accessed on 03 August 2022). |

| 5 | Janne Bondi Johannessen died of cancer in June 2020, only 59 years old. She will be remembered as one of the great figures in Scandinavian linguistics, and as we are writing this, we are still in mourning and coping with this loss. For an overview of Janne’s contribution to our field, cf. the English preface of Hagen et al. (2020). https://journals.uio.no/osla/article/view/8486/7896 (accessed on 2 August 2022). |

| 6 | The same speaker has been referred to under the pseudonym “Johan” in previous studies, but here we call him “Lars”. |

| 7 | Cf. Putnam and Salmons (2015) “In the village of Hustisford, in eastern Wisconsin, twenty-four percent of residents reported being monolingual in German in 1910, well over a half century after the main immigration to the community. Over a third of the reported monolinguals were born in the U.S. This included numerous third generation monolinguals—grandchildren of European immigrants who had not learned English—in 1910. Farther to the north, one scholar found that in a census district in New Holstein, twenty-eight percent reported being monolingual, with forty-nine of those born in the U.S.” |

| 8 | A koiné is a stabilized contact variety resulting from the mixing and leveling of features of varieties which are similar enough to be mutually intelligible, such as regional or social dialects; (cf. Siegel 2001, p. 175). |

| 9 | The terms Nynorsk and Bokmål were introduced in 1929. Before that, Bokmål, a standard originating from Danish, was called Rigsmaal/Riksmål. Nynorsk, based on Norwegian dialects, was called Landsmaal/Landsmål. We use the terms Nynorsk and Bokmål consistently to simplify; but note that the terms are slightly anachronistic. |

| 10 | Nordahl Rolfsen played a very central role in Norway’s school history as he published a very ground-breaking reader for the public school (Rolfsen 1892), which dominated the Norwegian school from the 1890s and well into the 1950s. This reader was also used in the US, and Rolfsen even compiled a reader intended for Norwegian American readers, Boken om Norge. |

| 11 | Decorah-Posten reached a circulation of 37,000 and Skandinaven approached 50,000 issues at a time when the largest newspaper in Norway, Aftenposten, had a circulation of 14,000 issues. It has to be mentioned though that while Decorah-Posten and Skandinaven came twice a week, Aftenposten had two daily issues. |

| 12 | 12 and 15 are the number of hours transcribed and selected for this study, out of many more hours of recordings that exist, also among our own recordings. We also use selected examples and informants from our earlier studies from Blair. |

| 13 | |

| 14 | Cf. http://tekstlab.uio.no/media/lydogbilde/amerikanorsk/einar_haugen/Transkripsjoner/ (accessed on 9 June 2022). A couple of comments are in order. Firstly, papers such as Decorah-Posten held on to the 1907 standard up until 1938, and it is more than likely that both written and spoken input would contain a lot of variation in the paradigms, depending on how conservative the writer would be. In our earlier investigations we also found that speakers would produce different inflections on different verbs, depending on whether they were of Norwegian or English origin, or even different inflections on the same verb, seemingly in a random fashion (e.g., our informant “Lena” who would produce /like/ or /liker/ as a present tense of the Norwegian verb ‘to like’). As the realizations of the inflections are more reliable in writing, we consulted a corpus of 500 “America-letters” and found that the same type of variation, e.g., between the more modern preterit kastet and the more archaic variant kastede, exists in variation for speakers of the same cohort. https://www.nb.no/emigrasjon/brev_oversikt_forfatter.php (accessed on 5 August 2022). |

| 15 | The infinitive in the old trønder dialect featured circumflex intonation, where monosyllable words are distinguished by tonality, like /kast/ ‘throw’ (noun) without circumflex and /kâst/ ‘throw’ (infinitive) with circumflex. This intonation is clearly in place for many of the older Trønder speakers, but no longer exists in recordings from the 2010s. |

| 16 | Other explanations are possible, but not as plausible. For instance, there was a substantial presence of speakers of the Telemark dialect (cf. Section 3.1 above) who would employ a paradigm featuring the same distinctions as Bokmål (but with other exponents). However, we cannot think of one single reason why the Telemark dialect would suddenly gain a much stronger impact in the community; furthermore, there is no reason why this impact, hypothetically, once established, would suddenly drop to a level explaining the developments we see in our data. The only causal feature of any substance that fits the time frame is written input. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | According to adult second-language learners of Norwegian, this is also how they approach the verbal paradigms of modern Norwegian in the homeland today. The written standard provides the regularity and authority of a norm, whereas the exponents, the actual forms realizing the slots in the paradigms, are recruited from the dialect they hear spoken around them. Thanks to Adrew Weir and Yvonne van Baal for volunteering their intuitions on this question. |

| 19 | Possessive constructions such as “boka hennes Janne” do not have a prenominal alternative and are as such ignored in this study. |

| 20 | The search yielded 25 POSS-N tokens versus 69 N-POSS ones. However, only about six of these twenty-five POSS-N structures have an actual N-POSS alternative, indicating that the proportion of prenominal possessives in the Gudbrandsdalen dialect is about 10%. These are small numbers and are only used to corroborate what we find from other sources. |

| 21 | One anonymous reviewer would like to see a lengthier discussion on why CLI is not at stake here. A proper answer to this question would require its own paper, but we mention some main points. Whenever a homeland variety contains two or more variants, i.e., exponents of the same morphosyntactic feature, rather sophisticated contextual restrictions regulate the selection between the two. This is the case for, e.g., null vs. overt pronouns (Sorace 2011), the presence or absence of resumptive pronouns in topicalizations (Bousquette et al. 2021) and the presence or absence of topicalizations themselves. In many language contact situations, simplification will occur such that one of the variants resides. Even if both variants are present in the input to some extent, there is too little input to provide the language learner with sufficient cues to observe the specific contextual restrictions relevant to the two variants. Thus, the language learner resorts to acquiring one of the variants, extending the functional domain of this variant to cover the domain of both variants. Now there is only one variant, performing the tasks split between two variants in the homeland variety. This is what constitutes “simplification” in language contact situations; an aspect of the debate on whether registers are possible in the “simplified grammars” we find in various contact situations. The acquisition of both variants hence depends on whether input is rich enough to provide the contextual cues. Moreover, which variant is chosen also depends on the input. In our data, we observe that “outlier Per”, whose input is almost exclusively written input, selects the prenominal possessive as his productive “fits-all” exponent, whereas his peers, whose inputs are exclusively spoken input, select the postnominal one as their single productive variant. The fact that the prenominal possessive is also present in the dominant language of the language learner (English) may be very significant to some learners and trigger a “close enough” response (those prone to alignment, cf. Section 5 below). For other learners, who tend to keep their two languages as separate as possible, the reaction may be exactly the opposite (those with an affinity to purism). To the latter learners, “norwegianness” will always trump the possibility for convergence between their two languages. |

| 22 | Cf. Bousquette et al. (2021) for a recent investigation into various topicalization variants in Norwegian and German heritage languages in the American Midwest. |

| 23 | Data from informant “Lena” born in 1929. |

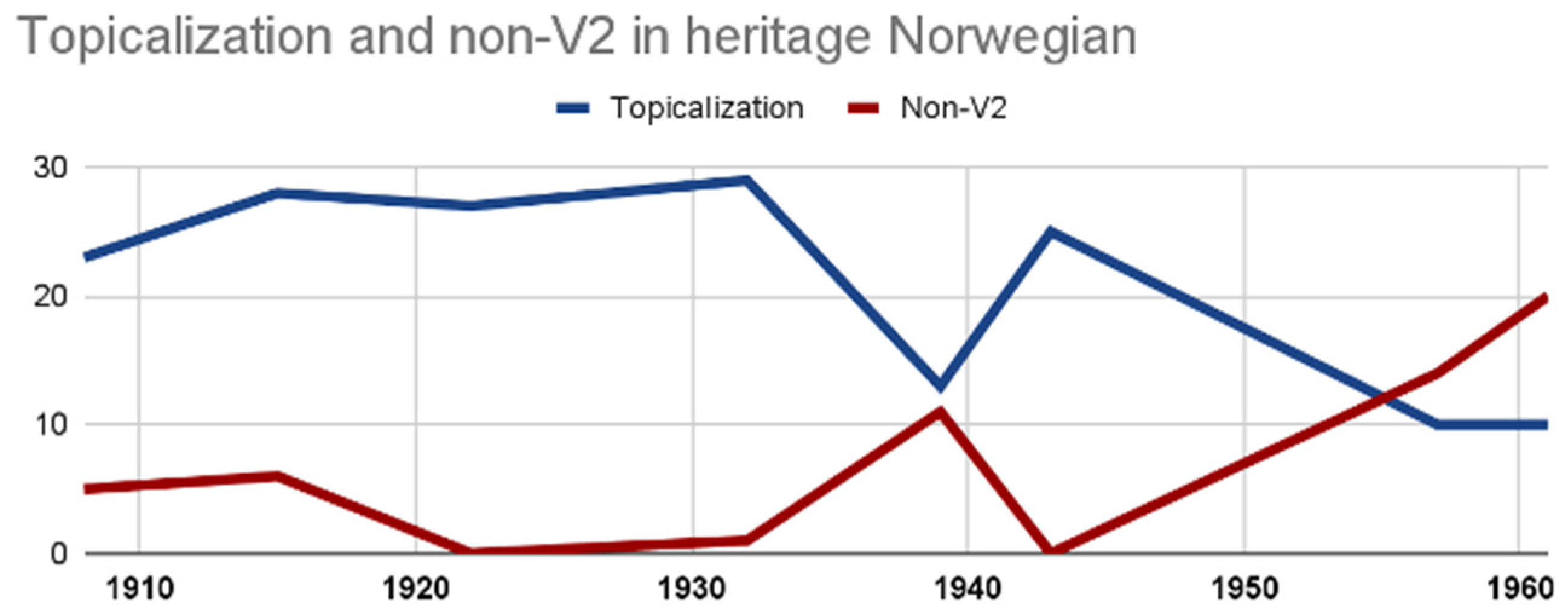

| 24 | The rate of topicalizations varies for the same speaker across contexts; cf. Eide and Hjelde (2015a), e.g., in online production vs. planned speech. Additionally, more complex topics typically trigger less V2. Note that certain adverbs, such as bare and kanskje trigger non-V2 even in homeland Norwegian, triggering a small percentage of non-V2 declaratives in production. |

| 25 | Liam is atypical compared to most of his cohort peers, as he speaks Norwegian frequently and seeks any opportunity to talk Norwegian. Hence, Liam’s continuous Norwegian input allows him to maintain his heritage language at a level different from most of his contemporary heritage speakers. |

| 26 | However, cf. Nistov and Opsahl (2014) for a study on new urban ethnolects in Norway where topicalization recedes, cf. also Freywald et al. (2014) for a comparative study of the phenomenon in new European urban vernaculars. |

| 27 | Chomsky uses the term “switch setting”, which we have substituted with “grammar” as it is more general. |

| 28 | Cf. Bakhtin (1981, p. 293): “Each word tastes of the context and contexts in which it has lived its socially charged life; all words and forms are populated by intentions. Contextual overtones (generic, tendentious, individualistic) are inevitable in the word.” |

| 29 | The term register in its classical sense has been confined to vocabulary, e.g., Trudgill (1983, p. 101) “Registers are usually characterized solely by vocabulary differences; either by the use of particular words, or by the use of words in a particular sense.” In more recent works, register is however extended to other linguistic features, as discussed, e.g., by Eide and Weir (2020, p. 229). |

| 30 | Or rather intake. Input refers to all the target language that the learner reads and hears; intake refers to the part of input which the learner comprehends and uses to develop his or her internal grammar of the target language. Van Patten (1996) attributes this term to Corder (1967). We are glossing over the input–intake debate here. |

| 31 | “Vore Børns Sprog er nesten udelukket Engelsk mend de forstaar hvert Ord, der tales til dem i norsk, det er haardt at faa lære Børnene norsk her i landet, da Engelsk falder dem lettere.” |

| 32 | Foreigner-directed, child-directed and computer-directed speech feature traits facilitating disambiguation, e.g., “less vowel reduction, a larger vowel space, a higher pitch, fewer idiomatic expressions, more high frequency words, simple syntactic constructions, and […] more repetitions as well as clarifications when compared to casual speech”; cf. Rothermich et al. (2019, p. 22). |

| 33 | Note that when we talk about the youngest speakers, these are the speakers born around 1940 and later; hence, some of these “youngsters” are in fact in their 80s, and the youngest of these “youngest” were around 50 when recorded (in their early 60s today). |

References

- Åfarli, Tor A. 2012. Hybride verbformer i amerikanorsk og analyse av tempus. [Hybrid verb forms in American Norwegian and analysis of tense]. Norsk Lingvistisk Tidsskrift 30: 381–98. [Google Scholar]

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2006. Grammars in Contact: A Cross-Linguistic Typology. In Alexandra Aikhenvald and R M W Dixon Grammars in Contact: A Cross-Linguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, Luiz, and Tom Roeper. 2014. Multiple grammars and second language representation. Second Language Research 30: 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschim, Anders. 2019. Luther and Norwegian Nation-Building. Nordlit 43: 127–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtin, Michail M. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Edited by Michael Holquist. Translated by Caryl Emerson, and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Allan. 1984. Language style as audience design. Language in Society 13: 145–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul, and Maria Polinsky. 2013. Heritage languages and their speakers: Opportunities and challenges for linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics 39: 129–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blegen, Theodore Christian. 1969. Norwegian Migration to America: The American Transition. Lake Geneva: Ardent Media. First published 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Blom, Jan-Petter, and John J. Gumperz. 2000. Social meaning in linguistic structure: Code-switching in Norway. In The Bilingualism Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 111–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bousquette, Joshua, Kristin Melum Eide, Arnstein Hjelde, and Michael T. Putnam. 2021. Competition at the Left Edge: Left-Dislocation vs. Topicalization in Heritage Germanic. In Selected Proceedings of the 10th Workshop on Immigrant Languages in the Americas (WILA 10). Edited by Arnstein Hjelde and Åshild Søfteland. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2000. The Architecture of Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Vivian Jones, and Mark Newson. 2007. Chomsky’s Universal Grammar. An introduction, 3rd ed. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Corder, Pit. 1967. The significance of learner’s errors. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 5: 161–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornips, Leonie, and Cecilia Poletto. 2005. On standardising syntactic elicitation techniques (part 1). Lingua 115: 939–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danbolt, Alf. 2021. Book Review of Biografi om C. F. W. Walther. [Biography of C. F. W. Walther]. Available online: https://www.fbb.nu/artikkel/biografi-om-cfw-walther/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Delsing, Lars-Olof, and Katarina Lundin-Åkesson. 2005. Håller språket ihop i Norden?: En forskningsrapport om ungdomars förståelse av danska, svenska och norska. [Does the Language Hold the Nordic Countries Together? A Research Report on Young People’s Understanding of Danish, Swedish and Norwegian? Copenhagen: Nordic Council Report. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum. 2002. Norwegian Modals. Ph.D. thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum. 2005. Norwegian Modals. Studies in Generative Grammar 74. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum. 2009a. Finiteness: The haves and the have-nots. In Advances in Comparative Germanic Syntax. Edited by Artemis Alexiadou, Jorge Hankamer, Thomas McFadden, Justin Nuger and Florian Schäfer. Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today 141. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 357–90. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum. 2009b. Tense, finiteness and the survive principle: Temporal chains in a crash-proof grammar. In Towards a Derivational Syntax: Survive-Minimalism. Edited by Michael Putnam. Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistic Today 144. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 91–132. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum. 2011. Norwegian non-V2 declaratives and the Wackernagel position. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 34: 179–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, Kristin Melum. 2016. Finiteness: Finiteness, inflection, and the syntax your morphology can afford. In Finiteness Matters: On Finiteness-Related Phenomena in Natural Languages. Edited by Kristin Melum Eide. Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistic Today 2231. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 121–67. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum. 2019. Convergence and Hybrid Rules: Verb Movement in Heritage Norwegian of the American Midwest. In Selected Proceedings of the 9th Annual Workshop on Immigrant Languages in the Americas (WILA 9). Edited by Kelly Biers and Joshua R. Brown. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum. 2022. Språket som superkraft. [Language Is Your Superpower]. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum, and Andrew Weir. 2020. Introduction to special issue on morphosyntactic variation within the individual language user. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 43: 229–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, Kristin Melum, and Arnstein Hjelde. 2015a. Verb Second and Finiteness Morphology in Norwegian Heritage Language of the American Midwest. In Moribund Germanic Heritage Languages in North America. Edited by Page B. Richard and Michael T. Putman. Leiden: Brill, pp. 64–101. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum, and Arnstein Hjelde. 2015b. Borrowing modal elements into American Norwegian. In Germanic Heritage Languages in North America. Edited by Janne Bondi Johannessen and Joseph C. Salmons. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 256–80. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum, and Arnstein Hjelde. 2018. Om verbplassering og verbmorfologi i amerikanorsk. [On verb placement and verb morphology in American Norwegian]. Maal og Minne 110: 25–70. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum, and Hilde Sollid. 2011. Norwegian main clause declaratives: Variation within and across grammars. In Linguistic Universals and Language Variation. Edited by Peter Siemund. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 327–60. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Kristin Melum, and Tor A. Åfarli. 2020. Dialects, registers and intraindividual variation: Outside the scope of generative frameworks? Nordic Journal of Linguistics 43: 233–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flom, George T. 1929. On the Phonology of English Loanwords in the Norwegian Dialects of Koshkonong in Wisconsin. Arkiv for Nordisk Filologi–Tilläggsband till bd, 178–89. [Google Scholar]

- Freywald, Ulrike, Natalia Ganuza, Ingvild Nistov, and Toril Opsahl. 2014. Urban vernaculars in contemporary northern Europe: Innovative variants of V2 in Germany, Norway, and Sweden. In Language Youth & Identity in the 21st Century. Edited by Jacomine Nortier and Bente Ailin Svensen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frøshaug, Andrea Skjold, and Truls Stende. 2021. Har Norden et språkfellesskap? [Does the Nordic Region Have a Language Community?]. Copenhagen: Nordic Council Report. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson, Laurann. 2009. Religion and Norwegian-American Quilts. University of Nebraska: Proceedings of the 4th Biennial Symposium of the International Quilt Museum, 3. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Giles, Howard. 1973. Accent mobility: A model and some data. Anthropological Linguistics 15: 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan, Tamar H., Jennie Starr, and Victor S. Ferreira. 2015. More than use it or lose it: The number-of-speakers effect on heritage language proficiency. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 22: 147–55. [Google Scholar]

- Granquist, Mark. 2015. Lutherans in America: A New History. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliksen, Øyvind T. 2002. Interdisciplinary Approaches in American Immigration Studies: Possibilities and Pitfalls. In Interpreting the Promise of America: Essays in Honor of Odd Sverre Lovoll. Edited by Odd S. Lovoll and Todd W. Nichol. Northfield: Norwegian-American Historical Association, pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, Kristin, Arnstein Hjelde, Karine Stjernholm, and Øystein A. Vangsnes, eds. 2020. Bauta: Janne Bondi Johannessen in Memoriam. OSLa. 11.2. Available online: https://journals.uio.no/osla/article/view/8486/7896 (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Haugen, Einar. 1938. Language and Immigration. Norwegian-American Studies 10: 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, Einar. 1939. Norsk i Amerika. [Norwegian in America]. Oslo: Cappelen. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, Einar. 1953. The Norwegian Language in America: A Study in Bilingual Behavior. Vol. I, The Bilingual Community. Vol. II, The American Dialects of Norwegian. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, Einar. 1966. Language Conflict and Language Planning: The Case of Modern Norwegian. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelde, Arnstein. 1992. Trøndsk talemål i Amerika. [The Trønder Dialect in America]. Trondheim: Tapir. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelde, Arnstein. 1996. Some phonological changes in a Norwegian dialect in America. In Language Contact across the North Atlantic. Edited by Ureland P. Sture and Iain Clarkson. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 283–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelde, Arnstein. 2012. “Folkan mine, dæm bære snakka norsk”–norsk i Wisconsin frå 1940-talet og fram til i dag. [«My people, they only spoke Norwegian»: Norwegian in Wisconsin from the 1940s until today]. Norsk Lingvistisk Tidsskrift 30: 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelde, Arnstein. 2015. Changes in a Norwegian dialect in America. In Germanic Heritage Languages in North America Germanic-Acquisition, Attrition and Change. Edited by Janne Bondi Johannessen and Joseph C. Salmons. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 283–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelde, Arnstein, and Camilla Bjørke. 2022. Reading Skills among Young Norwegian-American Heritage Speakers in the Early 1900s. In Selected Proceedings of the 11th Workshop on Immigrant Languages in the Americas (WILA 11). Edited by Kelly Biers and Joshua R. Brown. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelde, Arnstein, Bjørn Harald Kvifte, Linda Evenstad Emilsen, and Ragnar Arntzen. 2019. Processability Theory as a Tool in the Study of a Heritage Speaker of Norwegian. In Widening Contexts for Processability Theory: Theories and Issues. Edited by Anke Lenzing, Howard Nicolas and Jana Roos. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, E. 2020. Viewing dialect change through acceptability judgments: A case study in Shetland dialect. Glossa 5: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, Janne Bondi. 2015. The Corpus of American Norwegian Speech (CANS). Paper present at the 20th Nordic Conference of Computational Linguistics, NODALIDA 2015, Vilnius, Lithuania, May 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, Janne Bondi. 2018. Factors of variation, maintenance and change in Scandinavian heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 447–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, Janne Bondi. 2021. From Fieldwork to Speech Corpus: The American Norwegian Heritage Language and CANS. In Proceedings of the 10th Workshop on Immigrant Languages in the Americas (WILA 10). Edited by Arnstein Hjelde and Åshild Søfteland. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 1–10. Available online: http://www.lingref.com/cpp/wila/10/paper3535.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Johannessen, Janne Bondi, and Joseph C. Salmons. 2015. The study of Germanic heritage languages in the Americas. In Germanic Heritage Languages in North America: Acquisition, Attrition and Change. Edited by Janne Bondi Johannessen and Joseph C. Salmons. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, Janne Bondi, and Michael T. Putnam. 2020. Heritage Germanic languages in North America. In The Cambridge Handbook of Germanic Linguistics. Edited by Michael T. Putnam and Page B. Richard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 783–806. [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, Janne Bondi, and Signe Laake. 2015. On two myths of the Norwegian language in America: Is it old-fashioned? Is it approaching a written Bokmål standard? In The Study of Germanic Heritage Languages in the Americas. Edited by Janne Bondi Johannessen and Joe Salmons. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 299–322. Available online: http://www.jbe-platform.com/content/books/9789027268198 (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Johannessen, Janne Bondi, and Signe Laake. 2017. Norwegian in the American Midwest: A Common Dialect? Journal of Language Contact 10: 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joranger, Terje Mikael. 2010. Lokale eller nasjonale kollektive identiteter? Etnifisering og identitetsbygging blant norske immigranter i Amerika. [Local or national collective identities? Ethnification and identity building among Norwegian immigrants in America]. Historisk Tidsskrift 89: 223–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjær, Iver, and M. Baumann Larsen. 1972. Dansk i Amerika: Status og perspektiv. [Danish in America: Status and perspectives]. Sprog i Norden 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinmann, Howard H. 1977. Avoidance behavior in adult second language acquisition 1. Language Learning 27: 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroch, Anthony, and Ann Taylor. 1996. Verb movement in Old and Middle English: Dialect Variation and Language Contact. Philadelphia: Department of Linguistics, University of Pennsylvania [Host]. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, Arne. 1991. Norske stadnamn i Coon Valley, Wisconsin: Møte mellom to tradisjonar. [Norwegian place names in Coon Valley, Wisconsin: A meeting between traditions]. In Norsk språk i Amerika. [Norwegian Language in America]. Edited by Botolf Helleland. Oslo: Novus Press, pp. 135–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lovoll, Odd Sverre. 1977. Decorah-Posten: The Story of an Immigrant Newspaper. Norwegian-American Studies 27: 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lovoll, Odd Sverre. 1983. Det løfterike landet. [The Land of Promise]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Lovoll, Odd Sverre. 2006. Norwegians on the Prairie: Ethnicity and the Development of the Country Town. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lovoll, Odd Sverre. 2010. Norwegian Newspapers in America: Connecting Norway and the New Land. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lykke, Alexander K., and Arnstein Hjelde. 2022. New perspectives on grammatical change in heritage Norwegian: Introducing the adult speaker and adolescent relearner. University of Bergen: Bergen Language and Linguistics Studies 12: 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lødrup, Helge. 2012. Forholdet mellom prenominale og postnominale possessive uttrykk. In Grammatikk, bruk og norm. Festskrift til Svein Lie på 70-årsdagen, 15 April 2012. Edited by Hans-Olav Enger, Jan Terje Faarlund and Kjell Ivar Vannebo. Oslo: Novus, pp. 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Mathiesen, Henrik Olav. 2014. Belonging in the Midwest: Norwegian Americans and the Process of Attachment, ca. 1830–60. American Nineteenth Century History 15: 119–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matras, Yaron. 2009. Language Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, Mari J. 1991. Voices of America: Accent, Antidiscrimination Law, and a Jurisprudence for the Last Reconstruction. The Yale Law Journal 100: 1329–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisel, Jürgen M. 2020. Shrinking structures in heritage languages: Triggered by reduced quantity of input? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23: 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, Per. 1991. The influence of a Norwegian substratum on the pronunciation of Norwegian-Americans in Upper Midwest. In Norsk språk i Amerika. [Norwegian Language in America]. Edited by Botolf Helleland. Oslo: Novus Press, pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2008. Incomplete Acquisition in Bilingualism: Re-Examining the Age Factor. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Munch, Peter A. 1949. Social Adjustment among Wisconsin Norwegians. American Sociological Review 14: 780–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers-Scotton, Carol. 1993. Duelling Languages: Grammatical Structure in Codeswitching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nistov, Ingvild, and Toril Opsahl. 2014. The social side of syntax in multilingual Oslo. In The Sociolinguistics of Grammar. Edited by Tor A. Åfarli and Brit Mæhlum. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Pater, Joe. 2004. Bridging the gap between receptive and productive development with minimally violable constraints. In Constraints in Phonological Acquisition. Edited by René Kager, Joe Pater and Wim Zonneveld. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 2019–244. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Gregory Scontras. 2020. Understanding heritage languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23: 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, Ellen F. 1981. Topicalization, focus-movement, and Yiddish-movement: A pragmatic differentiation. Annual Meeting of The Berkeley Linguistics Society 7: 249–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Michael T., and Joseph Salmons. 2015. Multilingualism in the Midwest: How German has shaped (and still shapes) the Midwest. Middle West Review 1: 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reite, André Midtskogseter. 2011. Spørjing i skedsmokorsmålet: Ein generativ analyse av leddstelling og spørjeord i interrogative hovudsetningar i talemålet på Skedsmokorset. [Asking in the Skedsmokorset Dialect: A Generative Analysis of Sentence Structure and Interrogatives in Interrogative Main Clauses in the Skedsmokorset Dialect]. Master’s thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Riksem, Brita Ramsevik. 2018. Language Mixing in American Norwegian Noun Phrases. An Exoskeletal Analysis of Synchronic and Diachronic Patterns. Ph.D. thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Roeper, Thomas. 1999. Universal bilingualism. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 2: 169–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeper, Tom W. 2016. Multiple grammars and the logic of learnability in second language acquisition. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfsen, Nordahl. 1892. Læsebog for Folkeskolen: Med Tegninger af Norske Kunstnere. [Reader for the Primary School: With Drawings by Norwegian Artists]. Kristiania: Jacob Dybwads forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Rothermich, Kathrin, Havan L. Harris, Kerry Sewell, and Susan C. Bobb. 2019. Listener impressions of foreigner-directed speech: A systematic review. Speech Communication 112: 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, Jason. 2009. Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 155–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmons, Joseph. 2005a. The role of community and regional structure in language shift. In Regionalism in the Age of Globalism: Volume 1: Concepts of Regionalism. Edited by Lothar Hönnighausen, Marc Frey, James Peacock and Niklaus Steiner. Madison: Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures, pp. 129–38. [Google Scholar]

- Salmons, Joseph. 2005b. Community, Region and Language Shift in German-speaking Wisconsin. In Regionalism in the Age of Globalism: Volume 2: Forms of Regionalism. Edited by Lothar Hönnighausen, Anke Ortlepp, James Peacock, Niklaus Steiner and Carrie Matthews. Madison: Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern, pp. 133–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling-Estes, Natalie. 2004. Constructing ethnicity in interaction. Journal of Sociolinguistics 8: 163–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, John H. 1978. The Pidginization Process: A Model for Second Language Acquisition. New York: Newbury House Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, Jeff. 2001. Koine formation and creole genesis. Creole Language Library 23: 175–98. [Google Scholar]

- Soleng, Kine Dahlen. 2007. Their Minneapolis: Novels of Norwegian-American Life in Minneapolis. Master’s thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2011. Pinning down the concept of “interface” in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunde, Anne Mette. 2019. Skjult påvirkning: Tre studier av engelskpåvirkning i norsk. [Hidden Influence: Three Studies of English Influence in Norwegian]. Ph.D. thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Georg. 1991. Linguistic Purism. London and New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Troike, Rudolph C. 1970. Receptive competence, productive competence, and performance. In Linguistics and the Teaching of Standard English to Speakers of Other Languages or Dialects. Edited by James E. Alatis. Washington: Georgetown University Press, pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, Peter. 1972. Sex, Covert Prestige and Linguistic Change in the Urban British English of Norwich. Language in Society 1: 179–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudgill, Peter. 1983. On Dialect: Social and Geographical Perspectives. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ulbricht, Christiane, and Alexander Werth. 2021. What is Intra-individual Variation in Language? In Intra-Individual Variation in Language. Edited by Alexander Werth, Lars Bülow, Simone E. Pfenninger and Markus Schiegg. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton (Trends in Linguistics). [Google Scholar]

- Vaid, Jyotsna. 2002. Bilingualism. In Encyclopedia of the Human Brain. Edited by Vilayanur S. Ramachandran. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 417–44. [Google Scholar]

- van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen, and Liliane Haegeman. 2007. The Derivation of Subject-Initial V2. Linguistic Inquiry 38: 167–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Patten, Bill. 1996. Input Processing and Grammar Instruction in Second Language Acquisition. Norwood: AbLex Publishing Corperation. [Google Scholar]

- Venås, Kjell. 1974. Linne verb i norske målføre: Morfologiske studiar. [Weak Verbs in Norwegian Dialects: Morphological Studies]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich, Uriel. 2011. Languages in Contact: French, German, and Romansh in Twentieth-Century Switzerland. Introduction and Notes by Ronald I. Kim and William Labov. Amsterdam and Philadelphi: John Benjamins, First Publication of Weinreich’s Ph.D. thesis, Research Problems in Bilingualism with Special Reference to Switzerland, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard, Marit, and Merete Anderssen. 2015. Word order variation in Norwegian possessive constructions. In Germanic Heritage Languages in North America: Acquisition, Attrition and Change. Edited by Janne Bondi Johannessen and Joseph C. Salmons. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, Heike, Artemis Alexiadou, Shanley Allen, Oliver Bunk, Natalia Gagarina, Kateryna Iefremenko, Maria Martynova, Tatiana Pashkova, Vicky Rizou, Christoph Schroeder, and et al. 2022. Heritage speakers as part of the native language continuum. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 717973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winford, Donald. 2003. An Introduction to Language Contact. New York: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

| Location/Source | Blair | Coon Valley/Westby | Wanamingo/Zumbrota | Hours Recorded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942: Haugen | X | X | 8 | |

| 1930–40s: Haugen: CANS | X | 3 | ||

| 1987: Hjelde | X | 6 | ||

| 1992: Hjelde | X | 75 | ||

| 2010: Eide/Hjelde (NorAmDiaSyn) | X | X | 10 | |

| 2010–2014: CANS | X | X | 12 | |

| 2015–2018: Hjelde (NorAmDiaSyn) | X | 1512 | ||

| Field notes: Haugen, Hjelde | X | X | X |

| Cohort | I | II | III | IV | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born | Around 1870 | 1900–1920 | 1920–1930 | 1940–1950 | after 1950 |

| Data sets | Haugen 1940s | Haugen 1940s | Hjelde 1980s and 1990s | CANS Eide/Hjelde 2010 | CANS Hjelde 2010–2018 |

| Cohort | I | II | III | IV | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born | Around 1870 | 1900–1920 | 1920–1930 | 1940–1950 | after 1950 |

| Parent and child | Thor (Wa) | Iris (Z) | |||

| Mason (CV) | Liam (CV) | ||||

| Ted (CV) | Beth (W) | ||||

| Laura (W) | Lars (W) |

| a. | +finite | -finite | b. | +finite | -finite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +past | Preterit: kleima | Participle: kleima | +past | Preterit: kleimet | Participle: kleimet |

| -past | Present: kleimar | Infinitive: kleima | -past | Present: kleimer | Infinitive: kleime |

| a. | +finite | -finite | b. | +finite | -finite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +past | Preterit: kleime | Participle: kleime | +past | Preterit: kleima | Participle: kleima |

| -past | Present: kleimer | Infinitive: kleime | -past | Present: kleime | Infinitive: kleime |

| a. | +finite | -finite | b. | +finite | -finite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +past | Preterit: kleima | Participle: kleima | +past | Preterit: kleima | Participle: kleima |

| -past | Present: kleimer | Infinitive: kleime | -past | Present: kleime | Infinitive: kleim |

| a. | +finite | -finite | b. | +finite | -finite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +past | Preterit: kleima | Participle: kleima | +past | Preterit: claimed | Participle: claimed |

| -past | Present: kleime | Infinitive: kleime | -past | Present: claim | Infinitive: claim |

| Recordings | Generational Cohort | Prenominal Possessive | Postnominal Possessive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940s | I–II | 23% | 77% | |

| 1990s | III | 7% | 93% | |

| 2010s | Including outlier Per | III–V | 13% | 87% |

| 2010s | Excluding outlier Per | III–V | 5% | 95% |

| 2010s | outlier Per | III–V | 89% | 11% |

| Recordings | Prenominal Possessive Percentage | Prenominal Possessive Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| 1930s and 1940s (Haugen) | 23% | 91/404 |

| 1942 Coon Valley/Westby (Haugen) | 13% | 16/115 |

| 1980s and 1990s (Hjelde) | 12% | 15/126 |

| 2010s (CANS-project) | 5% | 40/739 * |

| Speaker | Thor | Iris | Mason | Liam | Ted | Beth | Laura | Lars |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | II | IV | II | IV | III | V | III | V |

| Birth year | 1908 | 1939 | 1915 | 1943 | 1932 | 1957 | 1922 | 1961 |

| Declaratives (N) | 235 | 274 | 87 | 164 | 779 | 68 | 254 | 318 |

| Topicalizations | 23% | 13% | 28% | 25% | 29% | 10% | 27% | 10% |

| Non-V2 | 5% | 11% | 6% | 0% | 1% | 14% | 0% | 20% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eide, K.M.; Hjelde, A. Linguistic Repertoires: Modeling Variation in Input and Production: A Case Study on American Speakers of Heritage Norwegian. Languages 2023, 8, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010049

Eide KM, Hjelde A. Linguistic Repertoires: Modeling Variation in Input and Production: A Case Study on American Speakers of Heritage Norwegian. Languages. 2023; 8(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleEide, Kristin Melum, and Arnstein Hjelde. 2023. "Linguistic Repertoires: Modeling Variation in Input and Production: A Case Study on American Speakers of Heritage Norwegian" Languages 8, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010049

APA StyleEide, K. M., & Hjelde, A. (2023). Linguistic Repertoires: Modeling Variation in Input and Production: A Case Study on American Speakers of Heritage Norwegian. Languages, 8(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010049