Abstract

In this paper, we consider mood selection in embedded clauses by focusing on a German-based minority language, Cimbrian, which is spoken in a northern Italian enclave. Mood selection in Cimbrian relies on the presence of two different complementizers, az and ke (the latter being borrowed from Romance varieties), each of which selectively require a specific mood. Az selects the mood subjunctive in modal sentences introduced by non-factive verbs, whereas ke co-occurs with the indicative in purely declarative clauses introduced by factive and semi-factive verbs. However, this binary distribution is challenged in the two following contexts, and it is precisely at this point that feature borrowing comes into play: (i) with the verb gloam ‘to believe/to think’, the expected binary pattern appears (irrealis az + subjunctive and the realis ke + indicative), but, crucially, a third construction emerges, namely ke + subj.; (ii) surprisingly, az + subj. displays some ‘gaps’ in its paradigm, specifically in the first person, which appeared in the data we collected via translation tasks from Italian into Cimbrian. Both phenomena shed light on how language contact works, not in terms of structural borrowing but rather in terms of the transfer of the specific features of a given lexical item.

1. Introduction

Cimbrian is a dialect of Bavarian origin which has lost the well-known Germanic linear V2 restriction allowing more than one constituent on the left of the finite verb (cf. 1):

| (1) | [In balt] | [haüt] | [dar pua] | hatt | gesek | in has |

| in-the woods | today | the boy | has | seen | the hare | |

| ‘In the woods today, the boy saw the hare’. | ||||||

In the literature devoted to Cimbrian1 syntax, there is, nevertheless, general agreement regarding the assumption that it still maintains structural V2, i.e., mandatory finite verb movement into the C domain, even after centuries of isolation from the German-speaking area in a Romance environment. This assumption is based on two traditional arguments:2

- (i)

- Subject–finite verb inversion, although this is limited to the pronominal subject:

(2) a. Gestarn in balt hatt=ar nèt gesek in has yesterday in-the wood has=he.cl not seen the.acc hare ‘Yesterday, he didn’t see the hare in the wood’. b. *Gestarn in balt hatt dar pua nèt gesek in has yesterday in-the wood has the.nom boy not seen the.acc hare - (ii)

- Residual asymmetry between the root and the embedded word order pattern, essentially based on the relative order of the negative particle (nèt) with respect to the finite verb (Vfin NEG versus NEG Vfin):

| (3) | Haüt | geat=ar | nèt | ka | Trento | ||

| today | go=he.cl | not | to | Tria | |||

| ‘Today, he doesn’t go to Trento’. | |||||||

| (4) | (I speràr), | az=ar | nèt | gea | ka Tria | haüt | |

| I hope | that=he.cl | not | go.sbjv | to Trento | today | ||

| ‘I hope that he doesn’t go to Trento today’. | |||||||

Of interest, Cimbrian is characterized by a dual system of lexical complementizers.3 In fact, Cimbrian presents both a class of low complementizers such as az that realize the lower functional field within the C domain, i.e., FinP (see Rizzi 1997), and a second class of higher complementizers that realize the highest portion of the C-domain (let us say SubordP, following Bhatt and Yoon 1991)4 to which the loanword ke belongs to. The most important diagnostic feature to detect the different position of the two classes of complementizers is the asymmetrical word order pattern triggered by az as already shown above in (4) and exemplified again in (cf. 6a) in clear contrast to sentences introduced by ke, which are characterized by the root word order pattern (cf. 5 with 6b):

| (5) | Dar | geat | nèt | ka | Tria | |||

| he | go | not | to | Trento | ||||

| ‘He doesn’t go to Trento’. | ||||||||

| (6) | a. | (I speràr), | az=ar | nèt | gea | ka Tria | ||

| I hope | that=he.cl | not | go.sbjv | to Trento | ||||

| ‘I hope that he doesn’t go to Trento’. | ||||||||

| b. | (I boaz), | ke | dar | geat | nèt | ka Tria | ||

| I know | that | he | go | not | to Trento | |||

| ‘I know that he doesn’t go to Trento’. | ||||||||

The opposition between az and ke does not simply rely on the maintenance versus the dismantling of the asymmetry between root and embedded word order, but is reinforced by a clear specialization of two lexical items:

- -

- az always requires the subjunctive mood, and typically introduces a declarative clause selected by non-factive (volitional) verbs such as bölln ‘to want’ and non-assertive (affective) verbs such as speràrn ‘to hope’ (see 6a above).

- -

- ke introduces embedded declarative clauses in the indicative mood that are selected by strongly assertive verbs such as khön ‘to say’ or semi-factive (knowledge) verbs such as bizzan ‘to know’ (see 6b above), perceptive verbs such as seng ‘to see’ and weakly assertive (epistemic) ones such as pensàrn ‘to think’.

The specialization of az versus ke is extremely interesting with regard to both the way in which the borrowing of functional words first affects the target system (cf. Section 2) and how it could further develop favoring the occurrence of ke and hence the gradual dismantling of the root-embedded word order asymmetry. In Section 3, we discuss a potential innovation in the occurrence of ke that was produced during the translation tasks by some native speakers which unexpectedly admit ke + subjunctive mood; in Section 4, we consider an evident weakness of az in connection with the first-person plural in the subjunctive paradigm. In the concluding remarks (cf. Section 5), we emphasize the coherence of our observations with recent assumptions about the relevance of heritage language studies to a theoretical approach to language contact in the bilingual brain and, ultimately, to a theory of language change (see Polinsky and Scontras 2020; Lohndal et al. 2019).

2. The Specialization of az versus ke

The specialization of az versus ke per se represents clear evidence of how the borrowing of functional words5 impacts on the target system from both a structural and a morphological point of view:

A. From a structural point of view:

(i) az represents the [-WH] counterpart of [+WH] ob ‘if’ in the introduction of argumental subordinate clauses and competes with finite verb movement with regard to the same structural position within the C domain; that is, Fin0. This is completely in line with the well-known German pattern whereby dass ‘that’ and the finite verb compete for the lexicalization of the so-called linke Satzklammer; that is, the head of the CP resulting in the root-embedded word order asymmetry.

(ii) ke does not compete with az with regard to the low C head but enters the Cimbrian Split-C domain lexicalizing its highest portion; that is, SubordP, and requiring the root V2 word order pattern (see also Padovan et al. 2016).6

B. From a morphological point of view:

(i) ke does not interfere with either the position or the morphology of the finite verb, as the latter displays the default indicative mood and always raises to Fin0, thus dismantling the root-embedded word order asymmetry (see 4a above).

(ii) az always requires the subjunctive mood and inhibits verb movement by reproducing the traditional word order asymmetry displayed by V2 Germanic languages.

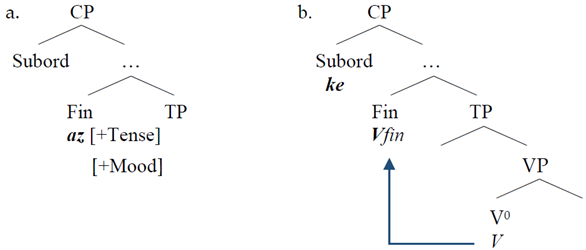

The following graphical representation (see Bidese et al. 2013, p. 55) illustrates the structural difference between az and ke:

| (7) |  |

Argumental clauses introduced by az imply the selection by a non-factive verb, and the embedding is overtly marked by the following phenomena:

(a) the lexical complementizer;

(b) the morphology of the finite verb, which displays the subjunctive mood; and

(c) the word order pattern; that is, the delayed position of the finite verb (=no verb movement = no subject–verb inversion).

By contrast, argumental clauses introduced by ke are generally selected by factive or semi-factive verbs, and embedding is signalled only by the lexical complementizer as there is no word order asymmetry nor subjunctive mood; that is, the finite verb raises to Fin and displays the default indicative value, as in the root declarative clause.

These clear-cut differences between the syntactic behavior of az with respect to ke force us to assume a double system of complementizers—in line with a large body of literature (see, among others, Grewendorf and Poletto 2009, 2011; Padovan 2011; Bidese et al. 2012, 2014; Padovan et al. 2016). There is, indeed, no historical evidence for a high az, as we would coherently expect for a Germanic V2 variety; on the contrary, high complementizers has been assumed for medieval Romance languages (see Wolfe 2019). The insertion of che into the Cimbrian C-system must be interpreted as a consequence of the splitting of the C-domain—i.e., the loss of linear V2 which opened the door to the borrowing of the Romance functional word.

The specialization of ke with regard to az shows that the borrowing of a functional word in the Cimbrian complementizer system resulted in a situation that is uncommon in both the Italian and the German systems, as both rely on a single lexical complementizer (that is, che—dass). Nevertheless, the choice of a different lexical complementizer determined by the class of factive versus non-factive verbs is well known in the literature, since it is attested in different language systems.7

If our analysis proves to be correct, we can assume that the borrowing of the lexical complementizer ke favoured the specialization of the paradigm that relied on a single lexical complementizer for the introduction of an argumental clause (the lack of a ‘high’ complementizer; that is, no lexical item in the highest structural position in the C domain), thus necessitating a restructuring of the system via the specialisation of the autochthonous az.8

3. A First Exception to the System: ke with the Subjunctive Mood

The data obtained during the translation task from Italian into Cimbrian revealed an interesting exception to the general system discussed in the previous paragraph: On one hand, our informants never connected az to the indicative mood; on the other hand, the choice of ke could unexpectedly co-occur with a subjunctive verbal form. The first context in which this occurred was with the semi-factive and assertive-epistemic verb gloam ‘to believe/to think’, which can select both the sequences az + Subjv and ke + Ind depending on the grade of certainty/veridicality. Let us consider the following examples:9 (8) shows the stimulus sentence in Italian to be translated into Cimbrian and (9) shows the examples of the translated sentences:

| (8) | Italian stimulus sentence: | Loro | credono | che | (lui) | sia | arrivato | tardi | |||

| they | believe | that | (he) | be.sbjv | arrived | late | |||||

| ‘They believe that he arrived late’. | |||||||||||

| (9) | a. | Sa | gloam | ke | dar | iz | gerift spet | (ke + Ind) | |||

| they | believe | that | he | is.ind | arrived late | ||||||

| b. | Sa | gloam | azz=ar | sai(be) | gerift | spet | (az + Subjv) | ||||

| they | believe | that=he.cl | is.subjv | arrived | late | ||||||

| c. | Sa | gloam | ke | dar | sai(be) | gerift | spet | (ke + Subjv) | |||

| they | believe | that | he | is.subjv | arrived | late | |||||

| d. | *Sa | gloam | azz=ar | iz | gerift spet | *(az + Ind) | |||||

| they | believe | that=he.cl | is.ind | arrived late | |||||||

A further context in which we elicited the string ke + Subjv was with the negative expression ‘z iz nèt khött ‘it is not certain’ (see 10), which triggered a non-veridical interpretation:

| (10) | Italian stimulus sentence: | Non | è | detto | che | Gianni | venga | con | noi | |||

| not | is | said | that | Gianni | come.subjv | with | us | |||||

| ‘It is not certain that Gianni will come with us’. | ||||||||||||

| (11) | ’Z | iz | nèt | khött | ke | dar Gianni | khemm | pit | üs | |||

| it | is | not | said | that | the Gianni | come.subjv | with | us | ||||

We are aware of the fact that, from a methodological point of view, the collected data are not statistically significant and that translation tasks are an extremely unusual way to collect data pertaining to bilingualism. Nevertheless, this approach allowed us to reproduce a strong ‘artificial’ attrition in the L1 that favored the borrowing of features. In addition, it should be noted that the data were confirmed by a follow-up questionnaire and that Tyroller (2003, p. 238), who questioned many more speakers, also mentioned that ke could select the subjective mood; unfortunately, he did not provide any examples.

The data presented above were notable due to at least three aspects:

(a) The exception to the az + Subjv − ke + Ind distribution (see 9c and 11 above) only goes in one direction, namely ke + Subjv, but *az + Ind;

(b) the possibility of combining ke with a subjunctive verbal form does not imply a word order variation. The subordinate clauses introduced by ke always display a root word order pattern; that is, no asymmetry root versus an embedded clause (see 7c and 9), unlike the sequence az + Subjv; and

(c) in our data, the combination ke + Subjv was only attested in translation tasks using the Italian model sentence and was not present in spontaneous production (but see Tyroller 2003, p. 238).

The innovation concerning the extension of ke within the specialization space of az is not as unusual at it may seem at first glance. On the contrary, it is coherent with the process of the gradual dismantling of the root versus embedded word order asymmetry, as noted previously in the literature on Cimbrian syntax (see Bidese and Tomaselli 2016), and acts as a further potential step towards the loss of V2. Furthermore, the pressure of Italian on Cimbrian morpho-syntax appeared to follow a precise path:

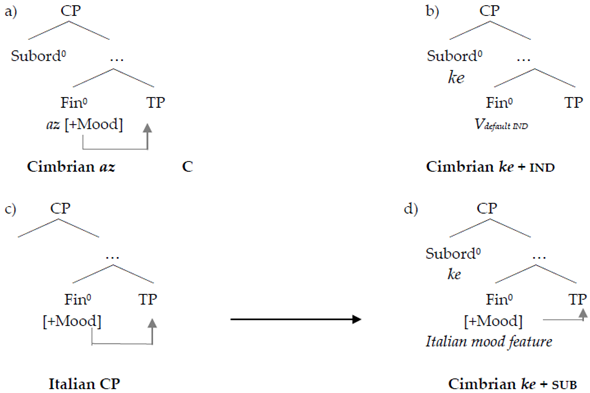

(i) The borrowing of a functional word, that is, the lexical complementizer ke, as a holistic lexical brick with no modal features that realises the highest position in the Cimbrian C domain; and

(ii) the functional feature [+MOOD] enters the system by replacing the default value of an empty (that is, unlexicalized) Fin0, which is c-commanded by ke. These two steps are represented in the following schema (see Bidese et al. 2013):

| (12) |  |

If we are correct, the impact of the model language on the functional C domain in the target language complies with the following requirements:

(a) It affects the highest functional layer, as a new functional word enters the system from above;10

(b) the borrowing of functional elements implies the absence of specialization of the paradigm at both the lexical and the morphological level in the target system. In fact, our analysis suggests that

(i) there is no substitution of the lexical element (ke instead of az), but rather the filling of an empty structural position in the target language. In other words, a new item taken from the Romance dialect is inserted into the Cimbrian C domain in a high ‘free’ position (SubordP); and

(ii) the change in the feature specification in a functional head only applies to the default value. In other words, the subjunctive mood co-occurring with ke realizes a non-selected default value in Fin0. In fact, we consider the Cimbrian ke to be a lexical (that is, semantic) subordinator that does not select the mood feature in Fin0, thus allowing feature borrowing from the Italian system.

The assumptions in (a) and (b) allowed us to draw our first conclusion: the coexistence of two grammatical systems in the bilingual brain supports the borrowing of abstract features and their recombination in the bilingual mind (see Aboh 2015, p. 5).

4. A Gap in the Paradigm of the Subjunctive Mood: The First-Person Plural

We found an interesting confirmation of what we have developed thus far in a second phenomenon that concerns the embedded sentences selected by the non-factive (or, more precisely, the semi-factive) verb gloam ‘to believe/to think’. If the embedded verb selected by gloam is in the first-person plural, the embedded sentences are always introduced by ke. In other words, in our data, the speakers systematically choose ke with the first-person plural in the embedded sentence. Consider the following examples:

| (13) | Italian stimulus sentence: | Credono | che | (noi) | siamo | arrivati | tardi | [+/− realis] | |||

| believe.3pp | that | we | are | arrived | late | ||||||

| ‘They believe that we arrived late’. | |||||||||||

| (14) | a. | Sa | gloam | ke | bar | soin | gerift | spet | |||

| they | believe | that | we | are | arrived | late | |||||

| b. | *Sa | gloam | az=par | soin | gerift | spet | |||||

| they | believe | that=we.cl | are | arrived | late | ||||||

To understand the problem in depth, let us consider the stimulus sentence and the entire paradigm of both possible expected translations: az + Subjv and ke + Ind (see Bidese et al. 2013, p. 54):

| (15) | Credo | di | essere | in ritardo | I | goabe | zo soina | spet | ||||

| believe.1ps | to | be | late | I | believe | to be.inf.fl | late | |||||

| (16) | a. | Credo | che | tu | sia | in ritardo | I | gloabe | az=to | sai(be)st | spet | |

| believe.1ps | that | you | be.subjv | late | I | believe | that=you.cl | be.2s.subjv | late | |||

| b. | I | gloabe | ke | du | pist | spet | ||||||

| I | believe | that | you | are.ind | late | |||||||

| (17) | a. | Credo | che | lui | sia | in ritardo | I | gloabe | azz=ar | sai(be) | spet | |

| believe.1ps | that | he | be.subjv | late | I | believe | that=he.cl | be.3s.subjv | late | |||

| b. | I | gloabe | ke | dar | iz | spet | ||||||

| I | believe | that | he | is.ind | late | |||||||

| (18) | a. | Credo | che | noi | siamo | in ritardo | *I | gloabe | az=par | soin | spet | |

| believe.1ps | that | we | be.ind/subjv | late | I | believe | that=we.cl | be.1p.ind/subjv | late | |||

| b. | I | gloabe | ke | bar | soin | spet | ||||||

| I | believe | that | we | are.ind | late | |||||||

| (19) | a. | Credo | che | voi | siate | in ritardo | I | gloabe | azz=ar | sait | spet | |

| believe.1ps | that | you | be.subjv | late | I | believe | that=you.cl | be.2p.ind/subjv | late | |||

| b. | I | gloabe | ke | dar | sait | spet | ||||||

| I | believe | that | you | are.ind | late | |||||||

| (20) | a. | Credo | che | loro | siano | in ritardo | I | gloabe | az=ze | soin | spet | |

| believe.1ps | that | you | be.subjv | late | I | believe | that=they.cl | be.3p.ind/subjv | late | |||

| b. | I | gloabe | ke | se | soin | spet | ||||||

| I | believe | that | they | are.ind | late | |||||||

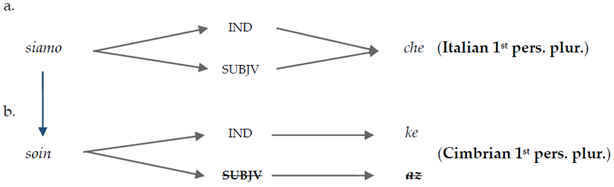

As it can easily be seen, Italian verb credo ‘to believe’ only selects the complementizer che with the subjunctive form which is morphologically different from the indicative one in all persons of the paradigm but the first-person plural. On the other side, Cimbrian has two possibilities depending on whether the action in the embedded clause should be interpreted as [+irrealis] (az + subjunctive) or [+realis] (ke + indicative). In Cimbrian, the morphological difference between subjunctive and indicative is visible only in the singular persons, and in the plural ones it exhibits syncretic forms. Cimbrian manifests the contrast through the specialization of the complementizers in a very consistent way with one exception. The first-personal plural is the only person in which the subjunctive and indicative forms are homophonous in Italian (for example, siamo ‘we are.subjv/ind’, abbiamo ‘we have.subjv/ind’, arriviamo ‘we arrive.subjv/ind’, leggiamo ‘we read.subjv/ind’ and finiamo ‘we finish.subjv/ind’). This is the only context in which the Cimbrian complementizer system exhibits a ‘gap’; that is, the choice of az is ruled out and ke represents the only possible choice (cf. 16). It should be stressed that the problem is not the homophonous forms in the Cimbrian mood system, in which, actually, all plural forms are syncretic between the indicative and the subjunctive; the real point is the syncretism in Italian, which is exclusively in the first-person plural.11

We assume that the exclusion of az in the first-person plural depends on the choice of Ind induced by homophony in Italian. In other words, the lack of subjv was contact induced in the grammar of our bilingual speakers who assumed these homophonous verbal forms to be a ‘default Ind’, thus forcing the choice of ke, as represented in the following schema (see Bidese et al. 2013, p. 56):

| (21) |  |

The notion of ‘default’ was revealed to be crucial once again, despite its formal definition not yet having been provided.

In the translation task, the influence of che in the model language was the indirect result of the morphological homophony of the suffix in the first-person plural. Of the two morphological values, the indicative exponent prevails leading to the logical selection of the appropriate lexical complementizer, which is ke as opposed to az, which is the specialized form for the subjunctive mood.

5. Conclusions

Cimbrian is a German(ic) variety that has been spoken in isolation in a geographical and linguistic Romance-language context for centuries; furthermore, the number of its native speakers has decreased dramatically in recent decades. In fact, it is included in the list of ‘definitely endangered’ languages (see Moseley 2010, p. 24). Its status as a heritage language is not entirely canonical because a larger community that maintains this variety (or rather its historical evolution) in a different geographical area does not exist, as is the case for the native varieties spoken by immigrants, nor is there a standard variety for reference. In fact, the process that resulted in Standard German followed the Cimbrian settlements in the north-eastern Italian regions by at least three centuries.

Nevertheless, Cimbrian complies fully with the three fundamental aspects of heritage languages on which there is general agreement in the scientific literature (see Lohndal et al. 2019, p. 4):

A. Heritage speakers are minority language speakers in a majority language environment. In this regard, Cimbrian is a severely endangered minority language of Germanic origin that is spoken in northern Italy.

B. Heritage speakers are bilingual. This is also true for Cimbrian, as all Cimbrian speakers have full competence in both the Italian dialect of the surrounding environment and in Standard Italian, which is the language of school education.

C. By the time they are adults, heritage speakers tend to be dominant, or more proficient (in a productive way) in the language of their larger national community.

The results of our analysis of the Cimbrian complementizer system support this and provide new insights into the following theoretical generalizations about stable and vulnerable domains in language contact situations in terms of multilingual competence (see the surveys proposed and discussed by Polinsky and Scontras 2020 and Lohndal et al. 2019, among others):

- (i)

- Syntactic knowledge, particularly the knowledge of phrase structure and word order, appears to be more resilient to incomplete acquisition under reduced input conditions than is inflectional morphology. In other words, the structure of the C domain is not only maintained, but is even enriched due to the pressure of the model language. In fact, the borrowing of the lexical complementizer ke resulted in an innovation within the Cimbrian system that is not found in either Italian or German, namely a specialized introduction for embedded clauses selected by factive versus non-factive verbs; furthermore, an embedded sentence introduced by ke does not manifest root-embedded asymmetry, but maintains the root word order pattern characterized by structural V2.

- (ii)

- The relative stability of syntactic features compared to morpho-phonological exponents. Our research revealed that the feature characterization of C as [+Fin], [+Mood] was definitely more stable than were the corresponding morpho-phonological exponents (subjunctive versus indicative)

- (iii)

- A prevalence for ‘defaults’; that is, the prevalence of the indicative mood with respect to the subjunctive mood and the dismantling of the root versus embedded word order asymmetry in favor of the root word order pattern.

Even if the formal definitions of crucial notions such as ‘default’ and ‘unmarked’ are still far from being determined, it seems clear that this theoretical question will find an answer precisely in the test ground of language contact situations that manifest a sufficient degree of both complexity and transparency.

Author Contributions

The overall paper is the result of joint work but each author provided their own individual contribution: conceptualization A.T. and E.B.; methodology, A.T., A.P. and E.B.; formal analysis A.T., A.P. and E.B.; investigation and data curation E.B.; writing A.T. and E.B.; supervision A.T. For the concerns of the Italian Academia, A.T. takes responsibility of Section 1 and Section 3; E.B. of Section 2 and Section 4. A.P. for Section 5. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the PRIN project “Models of language variation and change: new evidence from language contact” of the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research, grant nr. 2017K3NHHY (PI: Maria Rita Manzini).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented are all taken from previous literature, but confirmed and integrated by both dedicated fieldwork and the crowdsourcing platform VinKo (www.vinko.it). The data are stored in personal archives by the authors and partly available at the Eurac Research CLARIN Centre Repository (http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12124/32).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Tyroller (2003), Bidese (2004), Panieri et al. (2006), and Bidese (2021), among others, provided a general introduction to the formation of the Cimbrian language-islands in the north-eastern Alps and to the main linguistic features of Cimbrian. |

| 2 | See, amongst others, Grewendorf and Poletto (2011), Bidese and Tomaselli (2018), and Bidese et al. (2020). |

| 3 | Again, we refer to a large amount of research on this topic. In particular, see Grewendorf and Poletto (2009, 2011), Padovan (2011), Bidese et al. (2012, 2014), Padovan et al. (2016), Bidese and Tomaselli (2016), and Bidese (2017). |

| 4 | We follow the proposal by Grewendorf and Poletto (2011, based on Bhatt and Yoon 1991), who differentiated between complementizers that act as indicators of mood, such as the Cimbrian az ‘that’, and complementizers that act as pure subordinators (see Grewendorf and Poletto 2011, p. 318, Note 10 and Bidese 2017). |

| 5 | More precisely, we should describe the borrowing of functional words in terms of lexicalization or spelling out of the highest structural position of the Cimbrian C-domain by a lexical item taken from Italian functional lexicon. What matters to us is that the transfer of functional words does not imply the borrowing of a chunk of structure, but it works just like a filler of a new position created by the internal development of the language. |

| 6 | In this sense, we assume that the functional loanword ke enter the system ‘from above’ into the Cimbrian clause spine, affecting the highest portion of the C-domain. This assumption is supported by several facts, already discussed. |

| 7 | For example, this is the case in the Salentino dialect, which uses the complementizer ca + Ind in declarative or epistemic contexts and cu + Subjv in modal contexts (see Calabrese 1993; Damonte 2010). The same phenomenon can be found in southern Calabrian dialects (ca versus mu/ma/mi; see Rohlfs 1969, § 786a and Trumper and Rizzi 1985), as well as in some other southern Italian varieties (see Ledgeway 2004, 2005, 2007). A differentiation between declarative and volitional contexts and complementizer selection has also been identified in Romanian (see Farkas 1992), Albanian, Bulgarian (see Krapova 2010; Metzeltin 2016, p. 157), and Greek (see Giannakidou 1998, 2009, 2013). For a general overview of different complementizers depending on factive versus non-factive (modal) predicates in Slavonic, see Hansen et al. (2016). |

| 8 | The acquisition of embedded clauses in Italian–German bilingual children displays a similar phenomenon. Traute Taeschner’s (1983) study of her four- and five-year-old daughters showed that bilingual children produced the first embedded clauses in German earlier than did corresponding monolingual children, approximately at the same time as in Italian, but in the ‘wrong’ order; that is, with the root word order pattern: the lexical complementizer dass ‘that’ was used to introduce a V2 clause allowing subject–finite verb inversion. The correct asymmetrical word order, that is the final position of the finite verb, appeared later than it did in monolingual children, who apparently produce embedded clauses with the correct word order from the first attestations. In other words, the contact with Italian in the bilingual brain fills in a ‘gap’ in the process of acquiring German (characterized by a late maturation of the embedded structure) with a temporary innovation that will be dismissed at the appropriate acquisition stage (for a discussion of the data, see Alessandra; Carpene 1999). |

| 9 | The empirical data have been already published and discussed in detail in Bidese et al. (2013). We refer to this study for further explanations; also see Bidese (2017, pp. 143–45). |

| 10 | An anonymous reviewer notes that it is rather stipulative to assume that the complementizer che enters the Cimbrian system without a mood feature resulting in default indicative marking as in (10b), whereas only later on the mood feature of the Italian system is imported (cf. 10d), and asks for evidence for such a stepwise process instead of a single transfer of che plus subjunctive from the Italian system into the Cimbrian one. Let us put it more precisely in the following way: the evidence for this stepwise assumption is based on the fact that the verbs selected by ke in Cimbrian are only factive or semi-factive and that they are only compatible with the default (not selected/ not specified) value. On the contrary, che in Italian selects either indicative mood with factive verbs or subjunctive with non-factive verbs; when che enters the Cimbrian C-domain it specializes for the introduction of embedded clauses selected by factive verbs. Later on [+subjunctive] is imported as mood feature (cf. 12d) under the pressure of Italian (cf. 12c) in translation tasks which involve non-factive verb plus ke plus subjunctive, violating the Cimbrian ‘specialized’ system (cf. 12a,b). |

| 11 | An anonymous reviewer surmised that the Cimbrian speaker translated the sentence using the complementizer ke since only this complementizer is compatible with both indicative and subjunctive forms; hence, s/he believes that these data do not indicate any deep property or change in the Cimbrian system, but simply constitute a conscious decision in the translation task. We totally refuse this interpretation. The complementizer ke is not compatible with both mood forms, but only with the indicative one. The syncretic interpretation is present only in Italian. The deletion of the sentence with az in the first-person plural (cf. 18) is rather induced by the attrition with Italian during the translation task in the bilingual mind/brain of the speakers. It shows, nevertheless, in which direction the change of the Cimbrian system may evolve, namely, expanding the domain of ke with respect to az and spreading the symmetric word order. In fact, we never find az plus indicative. Remember that ke introduces a clause that does not display word order asymmetry with the root clause; hence, its expansion to subjunctive and perhaps non-factive verbs reduces the specialization space of az, weakening the whole V2 system, as root-embedded asymmetry is one of the fundamental correlates of the V2 phenomenon. |

References

- Aboh, Enoch Oladé. 2015. The Emergence of Hybrid Grammars. Language Contact and Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, Rakesh, and James Yoon. 1991. On the Composition of COMP and Parameters of V2. In The Proceedings of the 10th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Edited by Dawn Bates. Stanford: Stanford Linguistic Association, pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo. 2004. Die Zimbern und ihre Sprache: Geographische, historische und sprachwissenschaftlich relevante Aspekte. In “Alte” Sprachen. Beiträge zum Bremer Kolloquium über “Alte Sprachen und Sprachstufen”. Edited by Thomas Stolz. Bochum: Brockmeyer, pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo. 2017. Reassessing contact linguistics: Signposts towards an explanatory approach to language contact. Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik 84: 126–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo. 2021. Introducing Cimbrian. The main linguistic features of a German(ic) language in Italy. Energeia 46: 19–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2016. The decline of asymmetric word order in Cimbrian subordination and the special case of umbrómm. In Co- and Subordination in German and Other Languages. Edited by Ingo Reich and Augustin Speyer. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag, pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2018. Developing pro-drop: The case of Cimbrian. In Null Subjects in Generative Grammar. A Synchronic and Diachronic Perspective. Edited by Federica Cognola and Jan Casalicchio. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, Andrea Padovan, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2012. A binary system of complementizers in Cimbrian relative clauses. Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 90: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, Andrea Padovan, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2013. Bilingual competence, complementizer selection and mood in Cimbrian. In Dialektologie in Neuem Gewand. Zu Mikro-/Varietätenlinguistik, Sprachenvergleich und Universalgrammatik. Edited by Werner Abraham and Elisabeth Leiss. Hamburg: Buske, pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, Andrea Padovan, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2014. The syntax of subordination in Cimbrian and the rationale behind language contact. Language Typology and Universals—STUF Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung 67: 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, Andrea Padovan, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2020. Rethinking V2 and Nominative case assignment: New insights from a Germanic variety in Northern Italy. In Rethinking Verb Second. Edited by Rebecca Woods and Sam Wolfe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 575–93. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, Andrea. 1993. The sentential complementation of Salentino: A study of a language without infinitival clauses. In Syntactic Theory and the Dialects of ITALY. Edited by Adriana Belletti. Torino: Rosenberg & Sellier, pp. 29–98. [Google Scholar]

- Carpene, Alessandra. 1999. Bilinguismo precoce: Alcuni aspetti sintattici. In Studi su Fenomeni, Situazioni e Forme del Bilinguismo. Edited by Augusto Carli. Bolzano and Bozen: Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Damonte, Federico. 2010. Matching moods: Mood concord between CP and IP in Salentino and southern Calabrian subjunctive complements. In Mapping the Left Periphery. Edited by Paola Benincà and Nicola Munaro. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 228–56. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, Donka. 1992. On the Semantics of Subjunctive Complements. In Romance Languages and Modern Linguistic Theory. Edited by Paul Hirschbühler and Ernst Frederyk Konrad Koerner. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 67–104. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1998. Polarity Sensitivity as (Non)veridical Dependency. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2009. The dependency of the subjunctive revisited. Temporal semantics and polarity. Lingua 120: 1883–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2013. (Non)veridicality, evaluation, and event actualization. Evidence from the subjunctive in relative clauses. In Nonveridicality and Evaluation. Theoretical, Computational, and Corpus Approaches. Edited by Maite Taboada and Rada Trnavac. Leiden: Brill, pp. 17–49. [Google Scholar]

- Grewendorf, Günther, and Cecilia Poletto. 2009. The hybrid complementizer system of Cimbrian. In Proceedings XXXV Incontro di Grammatica Generativa. Edited by Vincenzo Moscati and Emilio Servidio. Siena: Centro Interdipartimentale di Studi Cognitivi sul Linguaggio, pp. 181–94. [Google Scholar]

- Grewendorf, Günther, and Cecilia Poletto. 2011. Hidden verb second: The case of Cimbrian. In Studies on German Language-Islands. Edited by Michael T. Putnam. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 301–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Björn, Alexander Letuchiy, and Izabela Błaszczyk. 2016. Complementizers in Slavonic (Russian, Polish, and Bulgarian). In Complementizer Semantics in European Languages. Edited by Kasper Boye and Petar Kehayov. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 175–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapova, Iliana. 2010. Bulgarian relative and factive clauses with an invariant complementizer. Lingua 120: 1240–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledgeway, Adam. 2004. Il sistema completivo dei dialetti meridionali: La doppia serie di complementatori. Rivista Italiana di Dialettologia 27: 89–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ledgeway, Adam. 2005. Moving through the left periphery: The dual complementiser system in the dialects of southern Italy. Transactions of the Philological Society 103: 336–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledgeway, Adam. 2007. Diachrony and finiteness: Subordination in the dialects of southern Italy. In Finiteness: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations. Edited by Irina Nikolaeva. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 335–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lohndal, Terje, Jason Rothman, Tanja Kupisch, and Marit Westergaard. 2019. Heritage language acquisition: What it reveals and why it is important for formal linguistic theories. Language and Linguistics Compass 13: e12357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzeltin, Michael. 2016. Das Rumänische in romanischen Kontrast. Eine sprachtypologische Betrachtung. Berlin: Frank & Timme. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, Christopher. 2010. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Paris: The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). [Google Scholar]

- Padovan, Andrea. 2011. Diachronic clues to grammaticalization phenomena in the Cimbrian CP. In Studies on German Language-Islands. Edited by Michael T. Putnam. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 279–99. [Google Scholar]

- Padovan, Andrea, Alessandra Tomaselli, Myrthe Bergstra, Norbert Corver, Ricardo Etxepare, and Simon Dold. 2016. Minority languages in language contact situations: Three case studies on language change. Us Wurk 65: 146–74. [Google Scholar]

- Panieri, Luca, Monica Pedrazza, Adelia Nicolussi Baiz, Sabine Hipp, and Cristina Pruner, eds. 2006. Bar lirnen z’ schraiba un zo reda az be biar. Grammatica del cimbro di Luserna. Grammatik der zimbrischen Sprache von Lusérn. Trento/Luserna: Regione Autonoma Trentino-Alto Adige/Autonome Region Trentino-Südtirol & Istituto Cimbro/Kulturinstitut Lúsern. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Gregory Scontras. 2020. Understanding heritage languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23: 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The Fine Structure of the Left Periphery. In Elements of Grammar. Handbook in Generative Syntax. Edited by Liliane Haegeman. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 281–337. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfs, Gerhard. 1969. Grammatica Storica Della Lingua Italiana e dei suoi Dialetti. Sintassi e formazione delle Parole. Torino: Einaudi, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Taeschner, Traute. 1983. The Sun is Feminine: A Study of Language Acquisition in Bilingual Children. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Trumper, John, and Luigi Rizzi. 1985. Il problema sintattico di CA/MU nei dialetti calabresi mediani. Quaderni del Dipartimento di Linguistica Università della Calabria 1: 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tyroller, Hans. 2003. Grammatische Beschreibung des Zimbrischen von Lusern. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, Sam. 2019. Verb Second in Medieval Romance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).