Abstract

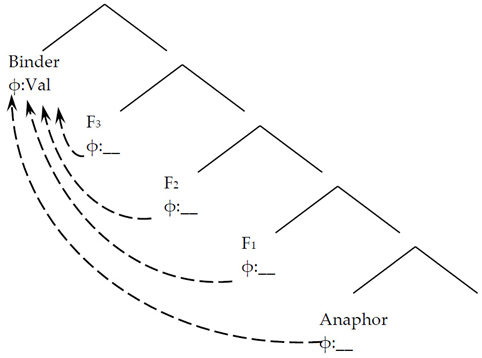

In this paper, I present evidence for variable agreement with anaphors in Tatar. I show that inflected reflexives trigger co-varying person agreement as DP/nominalization subjects and as complements of postpositions, which appears to contradict the generalization on the anaphor agreement effect (AAE). At the same time, inflected reciprocals induce 3p agreement on external targets. These data are puzzling in two aspects. First, it is unclear how to derive co-varying agreement with inflected reflexives because it cannot be handled as a regular exception to AAE predicted to arise by the agreement-based theory if the antecedent of the anaphor is positioned lower than the agreement target. Secondly, the difference between reflexives and reciprocals with respect to external agreement looks enigmatic. I propose that Tatar reflexives and reciprocals, despite their superficial resemblance, have different internal structures, which in turn bring about differences in their feature sets, and external agreement reveals these differences. As to AAE violations, I propose that the Tatar data can be accounted for under the feature sharing approach whereby the features on the anaphor and on the external probe are first identified as instances of the same feature set and then valued by the anaphor’s binder.

1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to examine agreement with anaphors in Tatar. Tatar possesses several anaphors which are regularly attested in local contexts: the simple reflexive üz-e ‘self-3’, the reduplicated reflexive üz-üz-e ‘self-self-3’ and the (reduplicated) reciprocal ber-ber-se ‘one-one-3’.1 Similarly to their counterparts in other Turkic languages, Tatar anaphors consist of a root (üz ‘self’, ber ‘one’) and a possessive affix. The possessive affix in anaphors co-varies with their binder with respect to a bundle of person and number features, much like the English reflexive pronouns myself, yourself, etc. Unlike English reflexives, however, Tatar anaphors can occur in syntactic positions construed with agreement: as subjects of nominalized clauses, as genitive possessors in DPs and as arguments of postpositions. Therefore, Tatar provides us with an opportunity to study agreement patterns available for anaphors. The two options we might expect are agreement co-varying with the possessive affix (thereafter person agreement pattern, (1a)) and invariable 3rd person/default agreement (thereafter default agreement pattern, (1b)).2

| (1) | a. | person agreement pattern | |

| Probe | Goal | ||

| X | üz-em | ||

| [uϕ: 1sg] | self-1sg | ||

| b. | default agreement pattern | ||

| Probe | Goal | ||

| X | üz-em | ||

| [uϕ: 3] | self-1sg | ||

Agreement with anaphors is of interest for several reasons. First of all, there is a robust cross-linguistic generalization called Anaphor Agreement Effect (AAE) which states that anaphors tend to avoid agreeing positions or, if licit in syntactic positions construed with agreement, can only trigger a default, non-co-varying agreement (Rizzi 1990; Woolford 1999; Sundaresan 2016). There are two major approaches accounting for AAE: the feature deficiency approach and the structural encapsulation approach. The feature deficiency approach (Kratzer 2009; Rooryck and Vanden Wyngaerd 2011; Murugesan 2019) relies on the idea that referential deficiency of anaphors results from their featural deficiency: possessing unvalued phi-features, anaphors need them to be valued by syntactic binding. Accordingly, anaphors’ phi-features only become valued after binding. This reasoning underlies the timing-based approach to AAE (Murugesan 2019): if the agreeing probe is lower than the binder, agreement with an anaphor fails or yields default values. The encapsulation approach (Preminger 2019) suggests that the reason for agreement failure is the anaphors’ complex internal structure: their phi-features are buried under a functional layer specific to anaphors, which makes them inaccessible for external agreement probes. Tatar data on agreement with anaphors is of high relevance for this line of research, because they allow us to test predictions of both approaches.

The second reason is that Tatar reflexive and reciprocal pronouns belong to a very intricate structural class of nominals centered around partitive constructions. Thus, Tatar anaphors pattern structurally with inflected quantifiers such as (bezneŋ) barı-bız da ‘all of us’, (sezneŋ) kajsı-gız ‘which of you’, (alarnıŋ) eki-se ‘two of them’, etc., cf. (2a–c).

| (2) | a. | Bez | üz-ebez-ne | gajeple | sana-bız. | |

| we | self-1pl-acc | guilty | believe.ipf-1pl | |||

| ‘We consider ourselves guilty.’ | ||||||

| b. | Bez | barı-gız-nı | da | gajeple | sana-bız. | |

| we | all-2pl-acc | ptcl | guilty | believe.ipf-1pl | ||

| ‘We consider you all guilty.’ | ||||||

| c. | Bez | ike-gez-ne | gajeple | sana-bız. | ||

| we | two-2pl-acc | guilty | believe.ipf-1pl | |||

| ‘We consider two of you guilty.’ | ||||||

Inflected quantifiers are true partitives (Seržant 2021) or canonical partitives (Falco and Zamparelli 2019), where the quantifier identifies the subset and the optional genitive possessor cross-referenced in possessive agreement denotes the superset (von Heusinger and Kornfilt 2017, 2021). Partitives are known for triggering variable agreement patterns both intra- and cross-linguistically (Martí i Girbau 2010; Danon 2013; Leclercq and Depraetere 2016; Pérez-Jiménez and Demonte 2017); in particular, agreement with inflected quantifiers has been reported to be sensitive to semantics, e.g., group reading vs. distributive reading of the partitive (Pérez-Jiménez and Demonte 2017). Consequently, we might expect Tatar anaphors to pattern with inflected quantifiers in their agreement properties; moreover, we should evaluate agreement with anaphors against agreement with inflected quantifiers. Comparing agreement with anaphors and agreement with inflected quantifiers would allow us to distinguish between AAE, which would only affect anaphors, and general agreement constraints in partitive constructions, which would influence equally anaphors and inflected quantifiers. Looking a bit ahead, Tatar data presented in this paper point towards the latter.

Finally, Tatar data are interesting against the background of other Turkic languages. To date, there is detailed information about agreement with inflected anaphors and inflected quantifiers in Turkish (Aydın 2008; Ince 2008; Kornfilt 1988; Paparounas and Akkuş 2020, forthcoming; Satık 2020); for Kyrgyz, Sakha, Altai and Uzbek, there is a more limited set of data concerning possessive agreement with inflected quantifiers coming from Satık 2020. Although data are scarce for generalizing over all Turkic languages, it is evident that there is significant variation in agreement patterns: thus, according to Aydın 2008 and Ince 2008, in possessive configurations, Turkish only allows for default agreement with inflected anaphors (see also Kornfilt 1988) and quantifiers, and Uzbek strongly prefers person agreement with inflected quantifiers (no data on anaphors), whereas Kyrgyz, Sakha and Altai allow for both patterns with inflected quantifiers (again, no data on anaphors). The data on Turkish inflected quantifiers presented in Paparounas and Akkuş (2020) and Satık (2020) suggest that there can also be variation between agreement configurations; thus, predicate agreement with nominative subjects exhibits the person agreement pattern, whereas predicate agreement with genitive subjects in nominalizations and possessive agreement with genitive possessors only allows for the default agreement pattern. However, more recent work (Paparounas and Akkuş, forthcoming) recognizes that Turkish inflected quantifiers allow for both agreement patterns in all agreement configurations; overt agreement with anaphors is not discussed. Given these findings, the complete Tatar dataset on agreement with anaphors and related constructions would contribute significantly to the intragenetic typology of Turkic languages.

Given what we know about agreement with anaphors in other Turkic languages and cross-linguistically, Tatar presents a previously undescribed case. The striking characteristic of Tatar is that agreement patterns attested with inflected anaphors are distributed not among various agreement positions, but among the anaphors themselves. Specifically, inflected reflexives invariably trigger the person agreement pattern, whereas inflected reciprocals strongly prefer the default agreement pattern. In (3a–b), this contrast is shown for the possessive agreement triggered by the nominalization’s genitive subject.

| (3) | a. | Bez | üz-üz-ebez-neŋ | awıl-ga | kil-ü-ebez-gä | / |

| we | self-self-1pl-gen | village-dat | come-nml-1pl-dat | |||

| *kil-ü-e-nä | šatlan-dı-k. | |||||

| come-nml-3-dat | become_glad-pst-1pl | |||||

| ‘We were pleased with our return to the village.’ | ||||||

| b. | Bez | ber-ber-ebez-neŋ | awıl-ga | *kil-ü-ebez-gä | / | |

| we | one-one-1pl-gen | village-dat | come-nml-1pl-dat | |||

| kil-ü-e-nä | šatlan-dı-k. | |||||

| come-nml-3-dat | become_glad-pst-1pl | |||||

| ‘We were pleased with each other’s return to the village.’ | ||||||

Moreover, this distribution is maintained in related partitive constructions. The lexical heads üz ‘self’ and ber ‘one’ are not only used in building reflexives and reciprocals, but also give rise to non-anaphoric partitive constructions exemplified in (4): ber ‘one’ produces the inflected quantifier (one of X), whereas üz ‘self’ produces the inflected intensifier (X oneself). These items, unlike inflected anaphors, are licit in the finite subject position construed with finite predicate agreement. Importantly, in this configuration, they show agreement patterns attested elsewhere with their anaphoric counterparts. The fact that the agreement pattern of a partitive is ultimately determined by its subset-denoting element provides us with a cue for capturing the contrasting properties of anaphors with respect to external agreement.

| (4) | a. | Üz-ebez | kal-ırga | ujla-dı-k | / | *ujla-dı |

| self-1pl | stay-inf | think-pst-1pl | think-pst | |||

| ‘We ourselves decided to stay.’ | ||||||

| b. | Ber-ebez | kal-ırga | *ujla-dı-k | / | ujla-dı. | |

| one-1pl | stay-inf | think-pst-1pl | think-pst | |||

| ‘One of us decided to stay.’ | ||||||

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, I discuss major agreement configurations in Tatar and show that anaphors maintain their agreement patterns across all the contexts. Section 3 examines the internal structure of anaphors and provides their characterization with respect to syntactic and semantic binding. The aim of this section is to demonstrate that the mismatch of agreement patterns between reflexives and reciprocals cannot be attributed to their different status with respect to binding. In Section 4, agreement patterns attested with inflected quantifiers are investigated. I show that the choice between the person agreement pattern and the default agreement pattern strongly correlates with the subset–superset relation specified by the quantifier. Section 5 sketches the analysis of the two agreement patterns based on a structural representation of the semantics of partitives. Section 6 concludes.

The data for this study come from several sources. Non-elicited examples are from the two corpora of Tatar—Corpus of written Tatar (620 mln tokens, https://search.corpus.tatar/en; accessed on 7 August 2022, tagged as [CWT] in the examples) and «Tugan Tel» Tatar National Corpus (180 mln tokens, http://tugantel.tatar/?lang=en; accessed on 7 August 2022, tagged as [TT]). Information about acceptability of anaphors and personal pronouns in various syntactic positions and with various agreement patterns was obtained by running a survey on the Yandex Toloka crowdsourcing platform (https://toloka.yandex.ru/en/; accessed on 7 August 2022); 15 native speakers of Tatar were asked to rate 55 sentences presented in a random order on the binary (yes/no) scale. Another survey whereby sentences exemplifying alternative agreement patterns attested with inflected quantifiers and intensifiers were evaluated against a wider context (forced choice task) was run on the Google Forms service (ten native speakers of Tatar, 15 sentences, two contexts for each). Judgments about availability of strict and sloppy readings were provided by my Kazan colleagues Ayrat Gatiatullin, Alfiya Galimova and Bulat Khakimov.

2. Agreement in Tatar

2.1. Basic Configurations

Tatar exhibits agreement in a wide array of configurations: finite predicate, nominalized predicate, possessive construction, postpositional phrase. An important property of Tatar agreement is that the categories involved in agreement—person and number—are the same for all the agreement configurations. Thus, Tatar differs from, e.g., German or French, which attest verbal predicate agreement for person and number but nominal concord for other categories.

The finite predicate agrees with its nominative subject. There are two sets of person–number agreement markers distributed between TAM forms of verbal predicates, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Agreement markers in finite verbal forms (adapted from Zakiev 1995, vol. 2, p. 86).

Table 1.

Agreement markers in finite verbal forms (adapted from Zakiev 1995, vol. 2, p. 86).

| Subject’s Features | Set I (“Full”): Present, Future 1 and 2, Perfect Indicative | Set II (“Truncated”): Past Indicative, Conditional, Hortative, Imperative |

|---|---|---|

| 1sg | -mIn3 | -m |

| 2sg | -sIn | -ŋ |

| 3sg | — | — |

| 1pl | -bIz | -k |

| 2pl | -sIz | -gIz |

| 3pl | (-lAr) | (-lAr) |

For 1–2p subjects, agreement is obligatory with overt and non-overt (pro) subjects (5a–c). For 3p subjects, there is no special agreement marker for person, and the predicate can optionally bear a plural affix –lAr (5d–e).

| (5) | a. | Menä | min | šušı | urın-da | kičermäslek |

| but | I | this | place-loc | unforgivable | ||

| zur | xata | jasa-dı-*(m). | ||||

| big | mistake | make-pst-1sg | ||||

| ‘But at that place I made a big, unforgivable mistake.’ [CWT] | ||||||

| b. | Närsä-gä | öjrän-ep | kajt-tı-*(gız) | sez? | ||

| what-dat | learn-cvb | return-pst-2pl | you | |||

| ‘What did you learn?’ [CWT] | ||||||

| c. | pro1sg | [pro3sg | siz-gän-e] | juk | dip | |

| notice-pf-3 | neg.cop | comp | ||||

| ujlıj | i-de-*(m). | |||||

| think.ipf | aux-pst-1sg | |||||

| ‘I thought he did not notice (it).’ [TT] | ||||||

| d. | Kız-lar | kul-lar-ı-n | jua-lar. | |||

| girl-pl | hand-pl-3-acc | wash.ipf-pl | ||||

| ‘The girls are washing their hands.’ [CWT] | ||||||

| e. | Kız-lar | aŋa | borıl-mıjča | tüzä | al-ma-dı. | |

| girl-pl | this.dat | turn-neg.cvb | resist.ipf | can-neg-pst | ||

| ‘The girls could not stand it and turned to him’ [CWT] | ||||||

The choice between agreeing and non-agreeing predicate with 3pl subjects is influenced by a number of parameters. First of all, number agreement is obligatory if the subject is non-overt, cf. (6). With overt subjects, the use of the plural marker can be semantically motivated, reflecting the collective/distributive distinction (cf. Zakiev 1995, p. 96; Lyutikova 2017, p. 32). However, it cannot be analyzed as a pure “semantic” agreement reflecting semantic plurality of the referent, since collective nouns like police or numeral constructions, which are grammatically singular, never trigger plural agreement (7). Performance factors can influence the use of –lAr as well: the larger the distance between the subject and the predicate, the more likely the plural agreement.

| (6) | pro3pl | Jırak-jırak | ǯir-lär-gä | oč-ıp | kitä-*(lär). |

| far-far | land-pl-dat | fly-cvb | leave.ipf-pl | ||

| ‘They are flying away to distant lands.’ [CWT] | |||||

| (7) | a. | Policija | aeroplan-nar-dan | gaz | bomba-lar-ı | tašla-dı-(*lar). | |

| police | airplane-pl-abl | gas | bomb-pl-3 | drop-pst-pl | |||

| ‘The police dropped gas bombs from airplanes.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| b. | Kazan-nan | Mäskäü | konservatorija-se-nä | uk-ırga | |||

| Kazan-abl | Moscow | conservatory-3-dat | study-inf | ||||

| ike | kız | kil-de-(*lär). | |||||

| two | girl | come-pst-pl | |||||

| ‘Two girls came to study in the Moscow Conservatory from Kazan.’ [CWT] | |||||||

Possessive agreement is characteristic for the genitive possessive construction (ezafe 3 in traditional grammatical descriptions, e.g., Zakiev 1963). Tatar possessive constructions can feature either a genitive or an unmarked (nominative or caseless) possessor (the latter is characteristic for ezafe 2 constructions); in both cases, the ezafe marker on the head noun is obligatory to license a dependent nominal constituent4. The distribution of genitive vs. unmarked possessors is influenced by a number of structural and interpretational factors (see Pereltsvaig and Lyutikova 2014 for discussion). Importantly, DP possessors (pronominal, definite and possessive noun phrases) cannot be unmarked and require genitive marking. Accordingly, unmarked possessors can only be 3p, whereas genitive possessors are not restricted with respect to the person feature.

The ezafe marker can host an agreement probe responsible for the possessive agreement. Possessive agreement markers are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Agreement markers in ezafe forms (adapted from Zakiev 1995, vol. 2, p. 32).

With unmarked possessors, which can only be 3p, the ezafe marker is invariably 3p (-I/-sI); number agreement is also illicit, cf. (8a–b). I consider this as evidence that the ezafe marker itself does not necessarily contain a phi-probe but can come without it.

| (8) | a. | bala-lar | bakča-sı |

| child-pl | garden-3 | ||

| ‘a/the kindergarten’ | |||

| b. | bala-lar | bakča-lar-ı | |

| child-pl | garden-pl-3 | ||

| ‘(the) kindergartens’ / ‘*a/the kindergarten’ | |||

With genitive possessors, the ezafe marker obligatorily displays co-varying possessive agreement. I consider this generalization as a direct outcome of genitive case assignment under phi-agreement. Thus, the ezafe marker licenses the nominal argument whereas the phi-probe is responsible for case assignment.

With 1–2p possessors, the head noun bears a possessive affix which agrees with the genitive possessor for person and number (9). Importantly, the plural marker –lAr on the head noun can only be assessed as an exponent of the interpretable number of the head, cf. (9d). Non-overt (pro) 1–2p possessors are readily available and trigger possessive agreement in the standard manner (9e).

| (9) | a. | sineŋ | ukıtučı-ŋ |

| you.gen | teacher-2sg | ||

| ‘your teacher’ | |||

| b. | sineŋ | ukıtučı-lar-ıŋ | |

| you.gen | teacher-pl-2sg | ||

| ‘your teachers’ | |||

| c. | bez-neŋ | ukıtučı-bız | |

| our-gen | teacher-1pl | ||

| ‘our teacher’ | |||

| d. | bez-neŋ | ukıtučı-lar-ıbız | |

| our-gen | teacher-pl-1pl | ||

| ‘our teachers’ (*‘our teacher’) | |||

| e. | pro2sg | ukıtučı-lar-ıŋ | |

| teacher-pl-2sg | |||

| ‘your teachers’ | |||

A deviation from this pattern is a genitive construction lacking a possessive affix, or a possessive-free genitive, PFG, as Satık (2020) dubs its counterpart in Turkish. PFG is only licensed with 1–2p possessors, and for some speakers, with 3p singular pronoun anıŋ (when used for humans) as well (10a–b); however, according to my Tatar consultants, neither personal names nor common nouns participate in PFG constructions (10c–d). The possessive-free genitive construction appears to have a more limited scope of application, but unlike the Turkish PFG (Öztürk and Taylan 2016), it can denote a kinship relation or a part–whole relation with body parts, cf. (11a–b).6

| (10) | a. | bez-neŋ | at-ıbız | / | at |

| we-gen | horse-1pl | / | horse | ||

| ‘our horse’ | |||||

| b. | a-nıŋ | at-ı | / | at | |

| this-gen | horse-3 | / | horse | ||

| ‘his/her horse’ | |||||

| c. | Marat-nıŋ | at-ı | / | *at | |

| Marat-gen | horse-3 | / | horse | ||

| ‘Marat’s horse’ | |||||

| d. | äti-m-neŋ | at-ı | / | *at | |

| father-1sg-gen | horse-3 | / | horse | ||

| ‘my dad’s horse’ | |||||

| (11) | a. | Minem | bala-nı | tatar-ča | ukıt-ma-gız! |

| I.gen | child-acc | Tatar-adv | teach-neg-2pl | ||

| ‘Do not teach my child in Tatar!’ [CWT] | |||||

| b. | Belä-seŋ, | minem | kul | jalgıš-mıj. | |

| know.ipf-2sg | I.gen | hand | mistake-neg.ipf | ||

| ‘My hand never makes mistakes, you know.’ [CWT] | |||||

The possessive construction with 3p genitive possessors differs from possessive constructions with 1–2p genitive possessors in that the plural genitive possessor can, but need not, trigger the appearance of the plural marker –lAr on the head noun (12).7 As a result, the plural marker in possessive phrases with a 3p plural possessor is ambiguous between interpretable and agreement-induced (13). Note that these possessive constructions contrast with ezafe 2 constructions with 3p plural unmarked possessors (8), where the plural marker on the head noun can only be interpretable.

| (12) | a. | Bondarenko | očučı-lar | mäktäb-en-dä | ukı-gan-da, | |

| Bondarenko | pilot-pl | school-3-loc | learn-pf-loc | |||

| major | alar-nıŋ | ukıtučı-lar-ı | bul-gan. | |||

| major | they-gen | teacher-pl-3 | be-pf | |||

| ‘When Bondarenko was in the pilot school, the major was their teacher.’ [CWT] | ||||||

| b. | Äle | kečkene | čag-ım-da… | min | alar-nıŋ | |

| already | small | time-1sg-loc | I | they-gen | ||

| ukıtučı-sı | bula | i-de-m | ||||

| teacher-3 | be.ipf | aux-pst-1sg | ||||

| ‘Since my childhood, I was their teacher.’ [CWT] | ||||||

| (13) | alar-nıŋ | ukıtučı-lar-ı |

| they-gen | teacher-pl-3 | |

| ‘their teachers’ / ‘their teacher’ | ||

It is important to mention that the nominal possessive structure is also employed in partitives based on quantifiers. The DP denoting the superset is represented by the genitive possessor, whereas the quantifier gets substantivized8 and corresponds to the possessum. Like in the standard possessive construction, the genitive possessor may be non-overt. With 1–2p genitives, possessive agreement is obligatory; with 3p genitives, number agreement is optional.

| (14) | a. | bez-neŋ | barı-bız | da | / | pro1pl | barı-bız | da | ||

| we-gen | all-1pl | ptcl | all-1pl | ptcl | ||||||

| ‘all of us’ | ||||||||||

| b. | alar-nıŋ | ike-se | / | alar-nıŋ | ike-lär-e | / | pro3pl | ike-se | / | |

| they-gen | two-3 | they-gen | two-pl-3 | two-3 | ||||||

| pro3pl | ike-lär-e | |||||||||

| two-pl-3 | ||||||||||

| ‘two of them’9 | ||||||||||

| c. | alar-nıŋ | kajsı-sı | / | alar-nıŋ | kajsı-lar-ı | / | pro3pl | kajsı-sı | / | |

| they-gen | which-3 | they-gen | which-pl-3 | which-3 | ||||||

| pro3pl | kajsı-lar-ı | |||||||||

| which-pl-3 | ||||||||||

| ‘which of them’ | ||||||||||

With most quantifiers, the plural affix –lAr can only be agreement-induced, since universal quantifiers and numerals exclude plural marking on the noun: ike kitap-(*lar) ‘two books’. However, the numeral ber ‘one’, the interrogative modifier kajsi ‘which’ and indefinite modifiers (nindider ‘any’, berkadär ‘some’, etc) are compatible with a plural-marked nominal. In the partitive construction, they can have an interpretable plural marker –lAr. With a 3p plural genitive, the plural marker –lAr is then ambiguous between interpretable and uninterpretable.

| (15) | a. | bez-neŋ | kajsı-lar-ıbız |

| we-gen | which-pl-1pl | ||

| ‘which ones among us’ | |||

| b. | alar-nıŋ | kajsı-lar-ı | |

| they-gen | which-pl-3 | ||

| ‘which one among them’/‘which ones among them’ | |||

Nominalized clauses exhibit two patterns depending on their status in the argument vs. adjunct dichotomy (see Kornfilt 2003, 2007; Aygen 2007 for the same distinction in Turkish). Argumental nominalizations are predominantly headed by regular deverbal nouns (-U) or perfective participles (-gAn); they take case affixes corresponding to the clause’s grammatical function within the main clause. In argumental nominalized clauses, the subject is genitive, and the nominalized predicate bears a possessive affix and agrees with this subject. Agreement with 1–2p subjects is obligatory (16a–b); number agreement with 3p subjects is optional (16c–d).

| (16) | a. | Bez-neŋ | žurnal-lar-nı | ǯiber-ü-*(ebez)-ne | sora-dı | ul. |

| we-gen | magazine-pl-acc | send-nml-1pl-acc | ask-pst | this | ||

| ‘He asked that we send him the magazines.’ [TT] | ||||||

| b. | Ul | minem | toz-la-gan | it | jarat-ma-gan-*(ım)-nı | |

| this | I.gen | salt-vbl-pf | meat | like-neg-pf-1sg-acc | ||

| gel | onıta. | |||||

| always | forget.ipf | |||||

| ‘He always forgets that I do not like salty meat.’ [CWT] | ||||||

| c. | Bügen | min | ukučı-lar-ım-nıŋ | mine | ||

| today | I | reader-pl-1sg-gen | I.acc | |||

| aŋla-w-ı-n | sorıj-m. | |||||

| understand-nml-3-acc | ask.ipf-1sg | |||||

| ‘Today, I ask my readers to understand me.’ [TT] | ||||||

| d. | Keše-lär-neŋ | üz-e-nnän | kurk-u-lar-ı-n | telä-gän | ul. | |

| man-pl-gen | self-3-abl | fear-nml-pl-3-acc | want-pf | this | ||

| ‘He wanted people to be afraid of him.’ [TT] | ||||||

In adjoined nominalized clauses with adverbial functions, we observe the same nominalizing morphology; specific semantic relations the adverbial clause bears with respect to the main clause are expressed by case markers and/or postpositions. Thus, dative and locative forms (-U-gA, -gAn-gA, -gAn-dA) introduce temporal adverbial clauses, ablative forms and postpositional phrases (-gAn-nAn, -gAn öčen, -gAn/-U arkasında) introduce causal adverbial clauses, etc.

As a general rule, in adverbial nominalized clauses the subject is nominative, and the nominalized predicate has no ezafe marker and exhibits no agreement (17). However, with several types of adverbial clauses (specifically, with temporal –U-gA clauses and causal clauses introduced by postpositions like –U arkasında) two other patterns are also licit—nominative subject plus agreeing ezafe marker and genitive subject plus agreeing ezafe marker. Tatar grammars describe the variation as free (Zakiev 1995, vol. 3, p. 344; Pazel’skaya and Shluinsky 2007). Adverbial nominalized clauses based on the –gAn participle only attest the general pattern—nominative subject plus ezafe-less predicate (Zakiev 1995, vol. 3, pp. 351–52). In the rest of this paper, I only consider argumental nominalizations, leaving the more puzzling patterns of agreement available in some adverbial nominalizations for future research.

| (17) | a. | Sin | kit-ü-gä, | a-nı | tiz | arada | |

| you | leave-nml-dat | this-acc | quickly | meanwhile | |||

| juk | it-ärgä | mömkin-när. | |||||

| neg.cop | do-inf | possibility-pl | |||||

| ‘Once you leave, it becomes possible to destroy10 it quickly.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| b. | Min | awır-gan-da, | Kimov | ta | ker-ep | čık-kan | |

| I | be_sick-pf-loc | Kimov | ptcl | enter-cvb | exit-pf | ||

| bul-sa | kiräk. | ||||||

| be-cnd | necessary | ||||||

| ‘Kimov must have come in when I was sick.’ [CWT] | |||||||

Finally, let us consider agreement in postpositional phrases. Among Tatar postpositions, only denominal postpositions exhibit agreement with their arguments. In what follows, we only discuss this subtype of postposition.

Denominal postpositions come in two forms, plain and agreeing. Plain postpositions consist of the relational root and one of the case markers—dat, loc, abl. In agreeing postpositions, there is a possessive affix between the root and the case marker.11 Example (18) illustrates these options.

| (18) | a. plain form | |

| minem | jan-da | |

| I.gen | near-loc | |

| ‘near me’ | ||

| b. agreeing form | ||

| minem | jan-ım-da | |

| I.gen | near-1sg-loc | |

| ‘near me’ | ||

Arguments of denominal postpositions appear in the genitive or nominative (caseless) form. Personal pronouns and 3p sg human pronoun are genitive; all other nominals, including other pronouns, proper names, etc., are caseless.

Case assignment and agreement in postpositional phrases are interrelated. With 1–2p and 3p sg human pronouns, which are always genitive-marked, both plain and agreeing forms of postpositions are licit (19a–b); in the agreeing form, 1–2p agreement is obligatory (19a). With the rest of the nominals, plain postpositions are illicit (19c–e); agreeing postpositions can optionally attach a plural affix –lAr between the root and the possessive affix signaling agreement with a 3p plural argument (19c,e). This option is predominantly used when the postposition’s argument is expressed by 3p plural pro (20).

| (19) | a. | minem | jan-da | / | minem | jan-ım-da | / | *minem | jan-ı-nda |

| I.gen | near-loc | I.gen | near-1sg-loc | I.gen | near-3-loc | ||||

| ‘near me’ | |||||||||

| b. | a-nıŋ | jan-da | / | a-nıŋ | jan-ı-nda | ||||

| this-gen | near-loc | this-gen | near-3-loc | ||||||

| ‘near her/him’ | |||||||||

| c. | *a-lar | jan-da | / | a-lar | jan-ı-nda | / | a-lar | jan-nar-ı-nda | |

| this-pl | near-loc | this-pl | near-3-loc | this-pl | near-pl-3-loc | ||||

| ‘near them’ | |||||||||

| d. | *Marat | jan-da | / | Marat | jan-ı-nda | ||||

| Marat | near-loc | Marat | near-3-loc | ||||||

| ‘near Marat’ | |||||||||

| e. | *kız-lar | jan-da | / | kız-lar | jan-ı-nda | / | kız-lar | jan-nar-ı-nda | |

| girl-pl | near-loc | girl-pl | near-3-loc | girl-pl | near-pl-3-loc | ||||

| ‘near the girls’ | |||||||||

| (20) | pro3pl | Jan-nar-ı-nda | min | bul-ma-sa-m, | ||

| near-pl-3-loc | I | be-neg-cnd-1sg | ||||

| jä | pro3pl | berär | küŋelsez | xäl-gä | tor-ır-lar. | |

| then | some | unpleasant | situation-dat | stay-fut-pl | ||

| ‘If I won’t be with them, they will get to some unpleasant situation.’ [CWT] | ||||||

Properties of agreement configurations in Tatar are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Agreement configurations in Tatar.

Summarizing the discussion, 1–2p pronouns trigger obligatory person+number agreement in all contexts construed with agreement. Agreement with 3p nominals is for number exclusively; it is optional unless the controller is non-overt. Additional properties that distinguish 1–2p pronouns (and 3p sg human pronoun anıŋ ‘this.gen’) from other nominals are that they allow for PFG in nominal possessive constructions, are marked with genitive as postpositions’ arguments and can combine with plain denominal postpositions.

2.2. Agreement with Anaphors

In this section, I present data on agreement with anaphors: the simple reflexive üz-e ‘self-3’, the reduplicated reflexive üz-üz-e ‘self-self-3’ and the (reduplicated) reciprocal ber-ber-se ‘one-one-3’. I show that reflexives and reciprocals differ systematically in all agreement configurations: 1–2p reflexives pattern with 1–2p pronouns, and 1–2p reciprocals pattern with 3p nominals.

Tatar anaphors are excluded from the finite clause’s subject position for binding reasons (I address this issue in Section 3); consequently, there are only three types of positions construed with agreement available for anaphors: possessors in nominal possessive construction, subjects of nominalizations and arguments of agreeing postpositions.

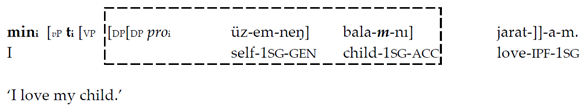

Both simple and reduplicated 1–2p reflexives trigger 1–2p agreement in all licit agreement configurations, cf. elicited examples in (21), as well as corpus examples (22) and (23). Thus, they exhibit the person agreement pattern (1a).

| (21) | a. possessive construction | |||||||

| Min | (üz)-üz-em-neŋ | bala-m-nı | / | *bala-sı-n | jarata-m. | |||

| I | self-self-1sg-gen | child-1sg-acc | child-3-acc | love.ipf-1sg | ||||

| ‘I love my own child.’ | ||||||||

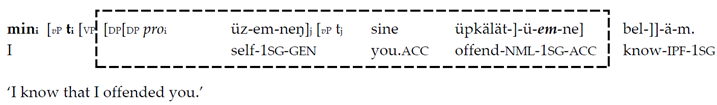

| b. nominalization | ||||||||

| Min | (üz)-üz-em-neŋ | sine | üpkälät-ü-em-ne | / | *üpkälät-ü-e-n | |||

| I | self-self-1sg-gen | you.acc | hurt-nml-1sg-acc | hurt-nml-3-acc | ||||

| bel-mi | i-de-m. | |||||||

| know-neg.ipf | aux-pst-1sg | |||||||

| ‘I didn’t know that I was hurting you.’ | ||||||||

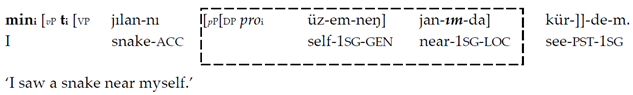

| c. postpositional phrase | ||||||||

| Min | jılan-nı | (üz)-üz-em-neŋ | jan-ım-da | / | *jan-ı-nda | kür-de-m. | ||

| I | snake-acc | self-self-1sg-gen | near-1sg-loc | near-3-loc | see-pst-1sg | |||

| ‘I saw a snake near myself.’ | ||||||||

| (22) | a. possessive construction | ||||||

| Min | üz-em-neŋ | xatın-ım-nı | häm | ike | ul-ım-nı | üter-de-m. | |

| I | self-1sg-gen | wife-1sg-acc | and | two | son-1sg-acc | kill-pst-1sg | |

| ‘I killed my wife and my two sons.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| b. nominalization | |||||||

| Üz-em-neŋ | matur | i-kän-em-ne | dä | ǯir-dä | bel-mičä | ||

| self-1sg-gen | beautiful | aux-pf-1sg-acc | ptcl | earth-loc | know-neg.cvb | ||

| jör-gän-men. | |||||||

| walk-pf-1sg | |||||||

| ‘I walked the Earth without knowing that I was beautiful.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| c. postpositional phrase | |||||||

| Kal-dır-gan | bul-sa, | üz-em-neŋ | jan-ım-a | al-ıp | kajt-ır | ||

| stay-caus-pf | be-cnd | self-1sg-gen | near-1sg-dat | take-cvb | return-fut | ||

| i-de-m | dä | ber | iptäš | bul-ır | i-de, | ič-ma-sa. | |

| aux-pst-1sg | ptcl | one | comrade | be-fut | aux-pst | drink-neg-cnd | |

| ‘If he quitted (drinking), I would take him with me, he would be my only friend, if he did not drink.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| (23) | a. possessive construction | ||||||

| Min | üz-üz-em-neŋ | uj-fiker-lär-em-ne | šušı | bloknot-ka | |||

| I | self-self-1sg-gen | thought-thought-pl-1sg-acc | that | notebook-dat | |||

| töšer-ep | bara-m. | ||||||

| put_in-cvb | go.ipf-1sg | ||||||

| ‘I keep writing down my thoughts into that notebook.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| b. nominalization | |||||||

| Čönki | bel | ütkän | zaman-da | üz-üz-ebez-neŋ | kem | ||

| because | know.imp | past | time-loc | self-self-1pl-gen | who | ||

| bul-gan-ıbız-nı | tirännän | aŋla-p | bel-ergä | tiješ. | |||

| be-pf-1pl-acc | deeply | understand-cvb | know-inf | need | |||

| ‘Because we should know it having understood deeply who we were in past times.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| c. postpositional phrase | |||||||

| Äni-eŋ | ölkän | jaš-tä … | al-ıp | kil | üz-üz-eŋ-neŋ | jan-ıŋ-a. | |

| mom-2sg | old | age-loc | take-cvb | come.imp | self-self-2sg-gen | near-2sg-dat | |

| ‘Your mom is old … come and take (her) to your place.’ [CWT] | |||||||

Note also that 1–2p reflexives pattern with 1–2p pronouns, in that they are genitive-marked in postpositional constructions (24a), can appear in the possessive-free genitive construction (24b–c) and combine with plain denominal postpositions (24a,d–e)12.

| (24) | a. | Min | a-nı | üz-em-*(neŋ) | jan-ım-da | / | jan-da | kür-de-m. | |

| I | this-acc | self-1sg-gen | near-1sg-loc | near-loc | see-pst-1sg | ||||

| ‘I saw it near myself.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Bez | Azija | belän | Jewropa | ara-sı-nda | üz-ebez-neŋ | |||

| we | Asia | with | Europe | between-3-loc | self-1pl-gen | ||||

| kunak-lar-nı | karšı | ala-bız. | |||||||

| guest-pl-acc | towards | take.ipf-1pl | |||||||

| ‘We meet our guests between Asia and Europe.’ [TT] | |||||||||

| c. | Üz-üz-egez-neŋ | bala | belän | arlaš-u | |||||

| self-self-2pl-gen | child | with | communicate-nml | ||||||

| alım-nar-ı-n | üzgert-egez. | ||||||||

| manner-pl-3-acc | change.imp-2pl | ||||||||

| ‘Change your manner of communication with your child.’ [CWT] | |||||||||

| d. | Ber | zaman | min | bul-ma-m, | üz-em-neŋ | urın-ga | |||

| one | time | I | be-neg.fut-1sg | self-1sg-gen | instead-dat | ||||

| Rädif-ne | kal-dır-a-m. | ||||||||

| Radif-acc | stay-caus-ipf-1sg | ||||||||

| ‘Once I am gone, I leave Radif in my place.’ [CWT] | |||||||||

| e. | Üz-ebez-neŋ | ara-da | šulaj | gına | atıj-bız | sez-ne. | |||

| self-1pl-gen | between-loc | so | only | call.ipf-1pl | you-acc | ||||

| ‘Among us, we only call you like that.’ [TT] | |||||||||

With 1–2p reciprocals, on the other hand, we generally find the default agreement pattern, cf. elicited examples in (25) and corpus examples in (26); only a couple of corpus examples shown in (27) attest 1–2p agreement, which was judged as marginal by my consultants. In postpositional phrases, 1–2p reciprocals appear in the nominative (caseless) form, which is also characteristic for 3p nominals; moreover, they do not occur in the PFG construction and do not combine with plain denominal postpositions (28).

| (25) | a. possessive construction | ||||||

| Bez | ber-ber-ebez-neŋ | bala-lar-ı-n | / | *bala-lar-ıbız-nı | jarata-bız. | ||

| we | one-one-1pl-gen | child-pl-3-acc | child-pl-1pl-acc | love.ipf-1pl | |||

| ‘We love each other’s children.’ | |||||||

| b. nominalization | |||||||

| Bez | ber-ber-ebez-neŋ | sine | xatın | it-ep | |||

| we | one-one-1pl-gen | you.acc | wife | do-cvb | |||

| sajla-gan-ı-n | / | *sajla-gan-ıbız-nı | bel-mi | i-de-k. | |||

| choose-pf-3-acc | choose-pf-1pl-acc | know-neg.ipf | aux-pst-1pl | ||||

| ‘We didn’t know that each of us had chosen you (as wife).’ | |||||||

| c. postpositional phrase | |||||||

| Bez | jılan-nar-nı | ber-ber-ebez-(*neŋ) | jan-ı-nda | / | *jan-ıbız-da | ||

| we | snake-pl-acc | one-one-1pl-gen | near-3-loc | near-1pl-loc | |||

| kür-de-k. | |||||||

| see-pst-1pl | |||||||

| ‘We saw snakes near each other.’ | |||||||

| (26) | a. possessive construction | ||||||

| Barıber | ber-ber-ebez-neŋ | isänleg-e-n | beleš-ep | tora | i-de-k. | ||

| still | one-one-1pl-gen | health-3-acc | ask-cvb | stay.ipf | aux-pst-1pl | ||

| ‘Still, we kept asking about each other’s health.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| b. nominalization | |||||||

| Ber-ber-ebez-neŋ | sulıš | al-u-ı-n | išetä-bez. | ||||

| one-one-1pl-gen | breath | take-nml-3-acc | hear.ipf-1pl | ||||

| ‘We feel each other’s breath (lit. We hear each other’s taking breath)’ [CWT] | |||||||

| c. postpositional phrase | |||||||

| Bez | küp | millet-le | töbäk-tä | jäši-bez, | ber-ber-ebez | tur-ı-nda | |

| we | many | people-atr | state-loc | live.ipf-1pl | one-one-1pl | about-3-loc | |

| kečkenä-dän | bel-ep | üs-ü | bik | kiräk. | |||

| childhood-abl | know-cvb | grow-nml | very | necessary | |||

| ‘We live in a multinational country; we shall grow up knowing about each other from our childhood.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| (27) | reciprocal, agreeing (possessive construction) | |||||

| a. | Kitap-ta | da | “ber-ber-egez-neŋ | gajeb-egez-ne | ezlä-mä-gez” | |

| book-loc | ptcl | one-one-2pl-gen | fault-2pl-acc | search-neg-2pl | ||

| dip | jaz-ıl-gan. | |||||

| comp | write-pass-pf | |||||

| ‘It is also written in the Qur’an, “do not look for each other’s fault”.’ [CWT] | ||||||

| b. | Uŋıšlı | xezmättäšlek | öčen | ber-ber-ebez-neŋ | ||

| beneficial | cooperation | for | one-one-1pl-gen | |||

| mömkinlek-lär-ebez-ne | häm | ixtıjaǯ-lar-ıbız-nı | ||||

| capacity-pl-1pl-acc | and | interest-pl-1pl-acc | ||||

| öjrän-ergä | kiräk. | |||||

| study-inf | necessary | |||||

| ‘For a mutually beneficial cooperation, we have to study capacities and interests of each other.’ [CWT] | ||||||

| (28) | a. possessive construction: no PFG | ||||

| *Bez | ber-ber-ebez-neŋ | bala-lar-nı | jarata-bız. | ||

| we | one-one-1pl-gen | child-pl-acc | love.ipf-1pl | ||

| Int.: ‘We love each other’s children.’ | |||||

| b. postpositional phrase: no plain postpositions | |||||

| *Bez | jılan-nar-nı | ber-ber-ebez-(neŋ) | jan-da | kür-de-k. | |

| we | snake-pl-acc | one-one-1pl-gen | near-loc | see-pst-1pl | |

| Int.: ‘We saw snakes near each other.’ | |||||

To sum up, 1–2p reflexives induce the person agreement pattern and behave like 1–2p pronouns in other grammatical respects (form a PFG construction, combine with plain denominal postpositions, require genitive marking with postpositions). On the other hand, 1–2p reciprocals generally trigger the default agreement pattern and behave like 3p nominals in other grammatical respects (do not form a PFG construction, do not combine with plain denominal postpositions, lack genitive marking with postpositions).

2.3. Tatar Agreement in Theoretical Perspective

In this section, I address theoretical accounts of Tatar agreement and show its relevance for all theories aiming to tackle agreement with anaphors.

I consider all Tatar configurations discussed in Section 2.1 as syntactic agreement configurations. They have all the hallmarks of agreement: they involve different extended projections, they are based on a one-to-one correspondence between probe and goal, they involve person features and they are rigidly connected to case licensing.

In fact, possessive agreement is the exact counterpart of the predicate agreement in the nominal extended projection. This parallelism in the structure of Turkic clauses and noun phrases has been generally acknowledged at least since Abney’s (1987) account of nominalizations. Updating Abney’s hypothesis with Chomsky’s (2000) theory of Agree, we can characterize predicate and possessive agreement in Tatar in the following way (see Pereltsvaig and Lyutikova 2014; Lyutikova 2017 for details). The relevant functional head (finite T or possessive D) bearing unvalued phi-features functions as a probe and finds a caseless nominal goal in its c-command domain. The emerging Agree relation yields valuation of the probe’s phi-features and case-licenses the goal nominal. T and D differ as to the structural case licensed: T assigns nominative and D assigns genitive. Finally, the goal is attracted to the specifier of the probe. The same holds for argumental nominalizations, where embedded clausal projections cannot case-license the subject and it enters the Agree relation with D. For denominal postpositions, we can assume a complex internal structure whereby the projection of a lexical head P selects for an argument which is case-licensed (and agreed with) by a functional head p similar to D.13 Agreement configurations are schematically represented in (29). It is important to emphasize that in all the agreement configurations in (29), the agreement target is higher than the controller, which complies with the standardly assumed structural relation between the probe and the goal.

| (29) | a. finite clause |

| [TP T[uϕ:__] [AspP … DP[iϕ:Val], [uCase:__] …] | |

| b. possessive noun phrase | |

| [DP D[uϕ:__] [NumP … DP[iϕ:Val], [uCase:__] …] | |

| c. argumental nominalization | |

| [DP D[uϕ:__] [vP … DP[iϕ:Val], [uCase:__] …] | |

| d. denominal postposition phrase | |

| [pP p[uϕ:__] [PP … DP[iϕ:Val], [uCase:__] …] |

The two constructions which apparently do not comply with this analysis are the PFG construction and the plain postposition construction. They seem to lack possessive agreement (and consequently, the ezafe marker in nominals and its counterpart in denominal postpositions) but still assign genitive case to personal pronouns.

Satık (2020) considers the Turkish PFG as an instance of genitive-marked adjuncts. Indeed, in Turkish, the PFG seems to be restricted to non-argumental uses. However, this is not the case in Tatar, see above. Moreover, the PFG construction can be employed to accommodate the nominalization’s subject, as in (30a). In any case, PFG nominals behave like DP arguments with respect to differential object marking; exactly like standard possessed nominals, they cannot remain caseless and require overt accusative marking, cf. (30b).

| (30) | a. | Tik | ul | minem | bügen | monda | kil-ü-ne |

| but | this | I.gen | today | here | come-nml-acc | ||

| bel-ergä | tiješ | tügel. | |||||

| know-inf | need | neg.cop | |||||

| ‘But he need not know that I come here today.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| b. | A-nıŋ | üz-e-neŋ | bala-lar-ı-na | äti | kiräk, | ||

| this-gen | self-3-gen | child-pl-3-dat | father | need | |||

| šuŋa | da | minem | äti-*(ne) | al-dı. | |||

| hence | ptcl | I.gen | father-acc | take-pst | |||

| ‘Her own children need (a) father, that is why she took mine.’ [CWT] | |||||||

Therefore, I conclude that the PFG is rather a specific phonological realization of the standard possessive construction than a separate syntactic construction. I assume that the same logic applies to plain forms of denominal postpositions, though we lack similar diagnostics for PPs. I refrain from formulating a specific PF rule responsible for these phenomena and only subsume them under the generalization that possessive and postpositional constructions can receive a special spell-out when their argument bears a marked person feature.

Though agreement configurations in (29) are structurally parallel, possessive noun phrases are unique featurally. Indeed, possessive DPs have two phi-feature sets: one is its own interpretable phi-feature set which is inherited by DP from the lower nominal projection and the other one is the uninterpretable phi-feature set which is valued via Agree and spelt out on the possessive affix. DPs cannot have two complete phi-feature sets, since an interpretable person feature is only present in indexicals, and they are DP proforms themselves and cannot combine with a possessive D. However, it is possible for a possessive DP to have an interpretable number feature inherited from the Num head.14 In this case, DP will possess two instances of number: interpretable number and agreement-induced uninterpretable number.15

Importantly, it is the interpretable phi-feature set that is employed in the external agreement with a possessive DP, cf. (31). In other agreement configurations, the relevant functional head only has an uninterpretable phi-feature set valued by agreement, which is never used as a source of phi-features by a higher probe.16

| (31) | a. | Bez-neŋ | ukıtučı-lar-ıbız | kil-de | / | kil-de-lär | / | *kil-de-k. |

| we-gen | teacher-pl-1pl | come-pst | come-pst-pl | come-pst-1pl | ||||

| ‘Our teachers came.’ | ||||||||

| b. | bez-neŋ | ukıtučı-lar-ıbız-nıŋ | kil-ü-e | / | kil-ü-lär-e | / | *kil-ü-ebez | |

| we-gen | teacher-pl-1pl-gen | come-nml-3 | come-nml-pl-3 | come-nml-1pl | ||||

| ‘our teachers’ coming’ | ||||||||

| c. | bez-neŋ | ukıtučı-lar-ıbız-nıŋ | kitab-ı | / | kitap-lar-ı | / | *kitab-ıbız | |

| we-gen | teacher-pl-1pl | book-3 | book-pl-3 | book-1pl | ||||

| ‘our teachers’ book’ | ||||||||

If the analysis presented above is essentially correct and all the agreement configurations in Tatar are construed in a similar fashion, as (29) depicts, we expect consistent behavior of anaphors across all the agreement configurations; our data show that this is indeed the case. Moreover, the fact that anaphors are excluded from finite subject positions in Tatar cannot be attributed to the AAE but requires an alternative explanation (which will be presented in Section 3).

Furthermore, the properties of agreement in Tatar allow us to exclude analytical options proposed in Satık (2020) for deriving the possible agreement with partitives and the lack of agreement with anaphors in Turkish. The author assumes that when the partitive construction triggers person agreement, which is the case in finite predicate agreement configurations, it is the 1–2p pronoun in the highest specifier of the possessive DP that is the controller of the agreement, and that phi-features of this pronoun are transferred directly to the probe, without any intermediate agreement process. The default agreement pattern with partitives (and anaphors as their subtype) in possessive agreement configurations results from the blocking effect produced by genitive marking. Genitive is assumed to increase the structural complexity of the partitive construction, which, in its turn, makes the possessor’s phi-features inaccessible for external probes. However, the generalization on Tatar agreement runs counter to this hypothesis: in possessive constructions and postpositional phrases, genitive goals trigger agreement whereas nominative/caseless goals do not.

The uniformity of agreement configurations in Tatar and the consistent behavior of anaphors across these configurations suggest that the difference between reflexives and reciprocals with respect to agreement patterns can only be accounted for by drawing on their own characteristics, e.g., their different internal structures, their different feature sets or their different statuses with respect to binding theory. In the next section, we examine the binding-theoretical properties of reflexives and reciprocals and investigate the relation between their anaphoric nature and their internal structure.

3. Tatar Anaphors and Their Binding

In this section, I discuss binding-theoretical properties of Tatar anaphors. To my knowledge, there are no detailed descriptions of the Tatar anaphoric system, let alone its characterization in terms of syntactic and semantic binding. The few relevant works include Shluinsky (2007) on anaphoric dependencies between the matrix and embedded clauses, and Podobryaev (2014) on indexical shift and alternative anaphoric strategies in finite dependent clauses, both based on the Mishar dialect of Tatar. For this reason, I have to present my own findings rather than build on previous literature, though exact and complete characterization of literary Tatar anaphora goes far beyond the purpose of this paper.

Reduplicated reflexives and reciprocals pattern together with respect to a number of properties. Both require a local binder; both are obligatorily bound semantically; both disallow overt expression of the possessor. Let us start with syntactic binding.

First of all, reduplicated reflexives and reciprocals are anaphors; they require a c-commanding antecedent (32a)–(33a). Importantly, the c-command requirement cannot be dispensed with and replaced by linear precedence, cf. (32b)–(33b).

| (32) | a. | Kızi | üz-üz-e-ni | fotoräsem-dä | kür-ep |

| girl | self-self-3-acc | photograph-loc | see-cvb | ||

| tan-dı. | |||||

| recognize-pst | |||||

| ‘The girl recognized herself on the picture.’ | |||||

| b. | *Kız-nıŋi | ukıtučı-sı | üz-üz-e-ni | fotoräsem-dä | |

| girl-gen | teacher-3 | self-self-3-acc | photograph-loc | ||

| kür-ep | tan-dı. | ||||

| see-cvb | recognize-pst | ||||

| Int.: ‘The girl’s teacher recognized her on the picture.’ | |||||

| (33) | a. | Kız-lari | ber-ber-(lär)-e-ni | fotoräsem-dä | kür-ep |

| girl-pl | one-one-pl-3-acc | photograph-loc | see-cvb | ||

| tan-dı-(lar). | |||||

| recognize-pst-pl | |||||

| ‘The girls recognized each other on the picture.’ | |||||

| b. | *Kız-lar-nıŋi | ukıtučı-lar-ı | ber-ber-se-ni | fotoräsem-dä | |

| girl-pl-gen | teacher-pl-3 | one-one-3-acc | photograph-loc | ||

| kür-ep | tan-dı-(lar). | ||||

| see-cvb | recognize-pst-pl | ||||

| Int.: ‘The girlsi’ teachers recognized themi on the picture.’ | |||||

The next thing to note is that Tatar reduplicated reflexives and reciprocals are not subject-oriented, i.e., they allow for a non-subject c-commanding antecedent.17 This is illustrated with corpus examples in (34a–b).

| (34) | a. | Bez | keše-nei | üz-üz-ei | belän | genä | kal-sa-k, … |

| we | man-acc | self-self-3 | with | only | leave-cnd-1pl | ||

| ‘If we leave a man alone with himself, …’ [CWT] | |||||||

| b. | Isem-när… | keše-lär-nei | ber-ber-se-nnäni | ajıra-lar. | |||

| name-pl | man-pl-acc | one-one-3-abl | distinguish.ipf-pl | ||||

| ‘Names … distinguish people from each other.’ [CWT] | |||||||

Finally, we have to determine the binding domain for reduplicated reflexives and reciprocals. Examples (32)–(34) suggest that it is at least as large as the clause containing the anaphor. To proceed further, we have to determine major types of clause embedding available in Tatar. In what follows, I delimit my study to complement clauses.

There are three major complementation strategies, which employ non-finite nominalized clauses (-U and –gAn), infinitival clauses (-rgA) and finite clauses introduced by the complementizer (dip, digän). Argumental nominalizations do not license nominative subjects; instead, they make use of nominal functional projections hosting possessive agreement and licensing a genitive subject (see Section 2.1 and Section 2.3 above). Infinitival clauses are used in control configurations, with desiderative, implicative and causative verbs, as well as with non-verbal modal predicates (e.g., kiräk ‘need’, tiješ ‘need’); their subject is the controlled PRO.18 Finally, a large class of matrix verbs including verbs of saying, thinking and emotions make use of the finite embedding strategy with the complementizer dip (digän). Finite embedded clauses license their own nominative subject which controls predicate agreement. A peculiar property of many Turkic languages including Tatar is the availability of accusative-marked subjects in finite embedded clauses (Baker and Vinokurova 2010; Baker 2015; Kornfilt and Preminger 2015; Lyutikova and Ibatullina 2015). Accusative subjects, like nominative subjects, control embedded predicate agreement; the only difference is that accusative subjects are only licit at the left edge of the embedded clause, whereas nominative subjects can appear clause-internally.19

The binding domain of reduplicated anaphors can be roughly defined as a minimal clause (finite or non-finite) or a DP containing a subject. This is shown in examples (35) for reduplicated reflexives (for reasons of space, I skip parallel examples for reciprocals); additional corpus examples of both reciprocals and reduplicated reflexives are provided in (36).

| (35) | a. | Alsui | Räfik-neŋj | üz-üz-e-nj,*i | kür-gän-e-n | belä. | |

| Alsu | Rafik-gen | self-self-3-acc | see-pf-3-acc | know.ipf | |||

| ‘Alsu knows that Rafik saw himself/*her.’ | |||||||

| b. | Alsui | Räfik-nej | PROj | üz-üz-e-nj,*i | kürsät-ergä | ǯiber-de. | |

| Alsu | Rafik-acc | self-self-3-acc | show-inf | send-pst | |||

| ‘Alsu sent Rafik to show himself/*her.’ | |||||||

| c. | Alsui | Räfik-(ne)j | üz-üz-e-nj,*i | jarata | dip | ujlıj. | |

| Alsu | Rafik-acc | self-self-3-acc | love.ipf | comp | think.ipf | ||

| ‘Alsu thinks that Rafik loves himself/*her.’ | |||||||

| d. | Alsui | Räfik-neŋj | üz-üz-ej,*i | tur-ı-nda-gı | xikejä-se-n | išet-te. | |

| Alsu | Rafik-gen | self-self-3 | about-3-loc-atr | story-3-acc | hear-pst | ||

| ‘Alsu heard Rafik’s story about himself/*her.’ | |||||||

| (36) | a. | Sini | üz-üz-eŋ-nei | alda-p | jör-gän-eŋ-ä | |

| you | self-self-2sg-acc | deceive-cvb | go-pf-2sg-dat | |||

| min | gajeple | tügel. | ||||

| I | guilty | neg.cop | ||||

| ‘It is not my fault if you were deceiving yourself.’ [CWT] | ||||||

| b. | Bezi | ber-ber-ebez-nei | jaxšı | belä-bez | dip | |

| we | one-one-1pl-acc | well | know-1pl | comp | ||

| ujlıj | i-de-m. | |||||

| think.ipf | aux-pst-1sg | |||||

| ‘I thought that we knew each other well.’ [CWT] | ||||||

| c. | pro1sg | Alar-nıŋi | ber-ber-sei | tur-ı-nda-gı | ||

| they-gen | one-one-3 | about-3-loc-atr | ||||

| fiker-lär-e-n | bel-de-m. | |||||

| thought-pl-3-acc | know-pst-1sg | |||||

| ‘I knew their opinion about each other.’ | ||||||

However, if a reduplicated anaphor is itself in the possessor/subject position, its binding domain is extended to the inclusion of another nominal which is a potential binder. Accordingly, the binding domain of the reduplicated anaphor is a minimal clause or a DP containing the anaphor itself and another DP which could serve as a binder.20 Extension of the binding domain can be observed in elicited examples (37) and in corpus examples (38a–c) where the reduplicated anaphor is in the subject/possessor position.

| (37) | a. | Alsui | [Räfik-neŋj | [üz-üz-e-neŋj,*i | Kazan-ga | kit-ü-e-n] |

| Alsu | Rafik-gen | self-self-3-gen | Kazan-dat | leave-nml-3-acc | ||

| bel-gän-e-n] | sizen-de. | |||||

| know-pf-3-acc | feel-pst | |||||

| ‘Alsu felt that Rafik knew that he/*she was going to Kazan.’ | ||||||

| b. | Kız-lari | jeget-lär-nej | [PROj | [ber-ber-se-neŋj, *i | xikejä-lär-e-n] | |

| girl-pl | boy-pl-acc | one-one-3-gen | story-pl-3-acc | |||

| tıŋla-rga] | mäǯbür | it-te. | ||||

| listen-inf | obliged | do-pst | ||||

| ‘The girlsi made the boysj listen to each other’sj, *i stories.’ | ||||||

| (38) | a. | Bez-neŋ | härkajsı-bızi | üz-üz-e-neŋi | adwokat-ı. | |||

| we-gen | each-1pl | self-self-3-gen | lawyer-3 | |||||

| ‘Each of us is his own lawyer.’ [CWT] | ||||||||

| b. | Šušı | portatiw | fotokamera | belän | keše-läri | |||

| that | handy | camera | with | man-pl | ||||

| üz-üz-lär-e-neŋi | közge-dä-ge | čagılıš-ı-n | ||||||

| self-self-pl-3-gen | mirror-loc-atr | reflection-3-acc | ||||||

| töšer-ä | i-de-lär. | |||||||

| take_down.ipf | aux-pst-pl | |||||||

| ‘With that handy camera, people take pictures of their reflection in the mirror.’ [CWT] | ||||||||

| c. | Alari | monda | ber-ber-se-neŋi | ni | belän | jäšä-gän-e-n | belä-lär. | |

| they | here | one-one-3-gen | what | with | live-pf-3-acc | know.ipf-pl | ||

| ‘Here they find out with what each of them lives.’ [CWT] | ||||||||

At the same time, the binding domain of reduplicated anaphors cannot be larger than a minimal finite clause containing the anaphor. Thus, reduplicated anaphors are ungrammatical as finite subjects, either nominative or accusative:21

| (39) | a. | *Alsu | [üz-üz-e | / | üz-üz-e-n | Räfik-ne | jaxšı | |

| Alsu | self-self-3 | self-self-3-acc | Rafik-acc | well | ||||

| belä | dip] | ujlıj. | ||||||

| know.ipf | comp | think.ipf | ||||||

| Int.: ‘Alsu thinks that she knows Rafik well.’ | ||||||||

| b. | *Kız-lar | [ber-ber-se | / | ber-ber-se-n | Räfik-ne | |||

| girl-pl | one-one-3 | one-one-3-acc | Rafik-acc | |||||

| jarata | dip] | aŋla. | ||||||

| love.ipf | comp | understand.ipf | ||||||

| Int.: ‘The girls understand that each of them loves Rafik.’ | ||||||||

| c. | *Bez | [üz-üz-ebez | / | üz-üz-ebez-ne | ber-ber-ebez-gä | |||

| we | self-self-1pl | self-self-1pl-acc | one-one-1pl-dat | |||||

| bulıš-ırga | tiješ | dip] | ujlıj-bız | |||||

| support-inf | need | comp | think.ipf-1pl | |||||

| Int.: ‘We think that we have to lend support to each other.’22 | ||||||||

Therefore, I conclude that reduplicated reflexives and reciprocals pattern together in that they are local syntactic anaphors. The next important property that they share is that they are obligatorily bound semantically in all the positions where they are licit. Examples in (40) show that they do not support a strict interpretation in focused contexts; in (41), the strict reading is excluded under ellipsis:

| (40) | a. | Sini | genä | üz-üz-eŋ-nei | kür-ä-seŋ. | |

| you | only | self-self-2sg-acc | see-ipf-2sg | |||

| ‘Only you see yourself.’ (OKsloppy reading, *strict reading) | ||||||

| b. | Bezi | genä | ber-ber-ebez-neŋi | bala-lar-ı-n | äjt-te-k. | |

| we | only | one-one-1pl-gen | child-pl-3-acc | invite-pst-1pl | ||

| ‘Only we invited each other’s children.’ (OKsloppy reading, *strict reading) | ||||||

| (41) | Alsui | üz-üz-e-neŋi | matur | i-kän-e-n | sanıj, | min | dä. |

| Alsu | self-self-3-gen | beautiful | aux-pf-3-acc | consider.ipf | I | ptcl | |

| ‘Alsu considers herself beautiful, and so do I.’ (OKsloppy reading, *strict reading) | |||||||

The last thing to note is that reduplicated anaphors disallow overt possessors, either nominal or pronominal. Thus, all the combinations listed in (42) are ungrammatical:

| (42) | a. nominal possessors: | ||||||

| *Alsu-nıŋ | üz-üz-e | / | *kız-lar-nıŋ | ber-ber-se | / | ber-ber-lär-e | |

| Alsu-gen | self-self-3 | girl-pl-gen | one-one-3 | one-one-pl-3 | |||

| b. 3p pronominal possessors: | |||||||

| *a-nıŋ | üz-üz-e | / | *a-lar-nıŋ | ber-ber-se | / | ber-ber-lär-e | |

| this-gen | self-self-3 | this-pl-gen | one-one-3 | one-one-pl-3 | |||

| c. 1–2p pronominal possessors: | |||||||

| *bez-neŋ | üz-üz-ebez | / | *sez-neŋ | ber-ber-egez | |||

| we-gen | self-self-1pl | you-gen | one-one-2pl | ||||

The simple reflexive üz-e ‘self-3’ differs from reduplicated anaphors in many respects. First of all, it allows for an overt genitive possessor (minem üz-em ‘I.gen self-1sg’, a-nıŋ üz-e ‘this-gen self-3’, kız-lar-nıŋ üz-(lär)-e ‘girl-pl-gen self-(pl)-3’ etc).23 In this case, it functions as an intensifier (43) and avoids syntactic binding (44).

| (43) | a. | At-lar-nı | tap-ma-sa-k, | minem | üz-em-ne | ||

| horse-pl-acc | find-neg-cnd-1pl | I.gen | self-1sg-acc | ||||

| al-ıp | kitä-lär | bit. | |||||

| take-cvb | leave.ipf-pl | ptcl | |||||

| ‘If we don’t find horses, they will take me away as well.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| b. | Sineŋ | üz-eŋ-neŋ | tormoz-ıŋ | ešlä-mä-gän | di-m | min, | |

| you.gen | self-2g-gen | brakes-2sg | work-neg-pf | say-1sg | I | ||

| belä-seŋ | kil-sä. | ||||||

| know.ipf-2sg | come-cnd | ||||||

| ‘I say that your own brakes didn’t work properly, if you ask.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| c. | Ǯir-neŋ | üz-e-nä | dä | köčle | ximikat | daru | |

| ground-gen | self-3-dat | ptcl | strong | chemical | drug | ||

| sipter-ep | tora-lar. | ||||||

| pour-cvb | stay.ipf-pl | ||||||

| ‘They pour strong chemical drugs into the soil itself.’ [TT] | |||||||

| d. | Läkin | min | säbäb-e-n | soraš-ma-dı-m, | |||

| but | I | reason-3-acc | ask-neg-pst-1sg | ||||

| Azat-nıŋ | üz-e-neŋ | äjt-kän-e-n | köt-te-m. | ||||

| Azat-gen | self-3-gen | tell-pf-3-acc | wait-pst-1sg | ||||

| ‘But I didn’t ask for an explanation, I waited that Azat would tell (it) himself.’ [TT] | |||||||

| (44) | a. | *Sin/pro2sg | sineŋ | üz-eŋ-ne | kürä-seŋ. | |

| you | you.gen | self-self-2sg-acc | see.ipf-2sg | |||

| Int.: ‘You see yourself.’ | ||||||

| b. | *Bez/pro1pl | bez-neŋ | üz-ebez-neŋ | bala-bız-nı | äjt-te-k. | |

| we | we-gen | self-1pl-gen | child-1pl-acc | invite-pst-1pl | ||

| Int.: ‘We invited the child of ours.’ | ||||||

With a non-overt possessor, the simple reflexive üz-e ‘self-3’ has a peculiar behavior. In configurations where the reduplicated reflexive is bound, the simple reflexive can have a c-commanding antecedent, too. In non-subject positions, the antecedent is found within its own clause (45a–b); in non-finite subject position, the binding domain extends up to the next clause, exactly like with reduplicated anaphors (45c). Importantly, in these cases, the simple reflexive can (or, in most local cases, is even strongly preferred to) be semantically bound (46).24 On the other hand, it can be coindexed with a non-local c-commanding antecedent (47) without being semantically bound by it (48). Finally, it can have no antecedent at all (49).

| (45) | a. | Sini | eš-tä | üz-eŋ-nei | kürsät-sä-ŋ, | aklana | |

| you | work-loc | self-2sg-acc | show-cnd-2sg | redeem.ipf | |||

| ala-sıŋ. | |||||||

| can.ipf-2sg | |||||||

| ‘If you prove yourself in work, you will be able to redeem yourself.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| b. | Mini | üz-em-neŋi | xatın-ım-nı | häm | ike | ||

| I | self-1sg-gen | wife-1sg-acc | and | two | |||

| ul-ım-nı | üter-de-m. | ||||||

| son-1sg-acc | kill-pst-1sg | ||||||

| ‘I killed my wife and my two sons.’ [CWT] | |||||||

| c. | Mini | alar-ga | üz-em-neŋi | ike | operacija | jasat-u-ım-nı | |

| I | they-dat | self-1sg-gen | two | surgery | perform-nml-1sg-acc | ||

| äjt-ep | karıj-m. | ||||||

| tell-cvb | look.ipf-1sg | ||||||

| ‘I look at them and tell that I have performed two surgeries.’ [TT] | |||||||

| (46) | a. | Alsui | genä | üz-e-ni | sekcijä-gä | jaz-dır-dı. |

| Alsu | only | self-3-acc | section-dat | write-caus-pst | ||

| ‘Only Alsu enrolled herself in the sports section.’ (OKsloppy reading, ?*strict reading) | ||||||

| b. | Bezi | genä | üz-ebez-neŋi | süz-ebez-ne | wlast’-ka | |

| we | only | self-1pl-gen | word-1pl-acc | authorities-dat | ||

| ǯitker-ergä | tiješ-bez. | |||||

| inform-inf | must-1pl | |||||

| ‘Only we have to communicate our statement to the authorities.’ (OKsloppy reading, ?strict reading) | ||||||

| c. | mini | üz-em-neŋi | matur | i-kän-em-ne | sanıj-m, | |

| I | self-1sg-gen | beautiful | aux-pf-1sg-acc | consider.ipf-1sg | ||

| Räfik | dä. | |||||

| Rafik | ptcl | |||||

| ‘I consider myself beautiful, and so does Rafik.’ (OKsloppy reading, okstrict reading) | ||||||

| (47) | a. | [pro3pl | Üz-em-nei | jarat-u-lar-ı] | belän | bäxetle | mini. | ||

| self-1sg-acc | love-nml-pl-3 | with | happy | I | |||||

| ‘I am happy to be loved.’ [TT] | |||||||||

| b. | Mini | berenče | tapkır | [[üz-em-neŋi | öst-em-ä | kil-gän] | |||

| I | first | time | self-1sg-gen | over-1sg-dat | come-pf | ||||

| fašist-nıŋ | tilergän | küz-lär-e-n] | kür-de-m. | ||||||

| fascist-gen | crazy | eye-pl-3-acc | see-pst-1sg | ||||||

| ‘For the first time I saw the crazy eyes of the fascist who stood over me.’ [TT] | |||||||||

| c. | Uli, | [[[üz-ei | jaxšı | dip] | ujla-gan] | berničä | šigır-e-n] | ||

| this | self-3 | good | comp | think-pf | several | poetry-3-acc | |||

| bik | tırıš-ıp | ak-ka | küčer-ep, | ber | gazeta-ga | ||||

| very | care-cvb | white-dat | copy-cvb | one | newspaper-dat | ||||

| bir-ü | öčen | idaräxanä-gä | kit-te. | ||||||

| give-nml | for | administration_office-dat | leave-pst | ||||||

| ‘He rewrote diligently fair copies of several poetries which he believed to be good and went to the administration office to send (them) to a newspaper.’ [CWT] | |||||||||

| (48) | a. | [Äti-m-neŋ | üz-em-nei | Kazan-ga | üz-e | belän | al-gan-ı-n] | |

| father-1sg-gen | self-1sg-acc | Kazan-dat | self-3 | with | take-pf-3-acc | |||

| mini | genä | xäterli-m. | ||||||

| I | only | remember.ipf-1sg | ||||||

| ‘Only I remember that my father took me to Kazan with him.’ (*sloppy reading, OKstrict reading) | ||||||||

| b. | Mini | genä | [[üz-em-nei | üpkälät-kän] | jeget-tän] | üč | al-dı-m. | |

| I | only | self-1sg-acc | offend-pf | boy-abl | revenge | take-pst-1sg | ||

| ‘Only I took revenge on the guy who offended me.’ (*sloppy reading, OKstrict reading) | ||||||||

| (49) | a. | pro3sg | Watan-nı | sakla-rga | bar-ma-sa, | |||

| motherland-acc | defend-inf | go-neg-cnd | ||||||

| üz-ebez-neŋ | jan-ıbız-da | järdämče | bul-ır. | |||||

| self-1pl-gen | near-1pl-loc | assistant | be-fut | |||||

| ‘If they are not going to defend the motherland, they will be our aide near us.’ [CWT] | ||||||||

| b. | Tatar | jäš-lär-e | üz-ebez-neŋ | matur | jaŋgırašlı | |||

| Tatar | joung-pl-3 | self-1pl-gen | beautiful | sonorous | ||||

| isem-när-gä | kajta | bašla-dı. | ||||||

| name-pl-dat | return.ipf | begin-pst | ||||||

| ‘Tatar youth started getting back to our beautiful sonorous names.’ [CWT] | ||||||||

The two opposite patterns—the bound anaphor and semantically free pronominal—suggests that in case of üz-e ‘self-3’, we are dealing with exempt anaphora (Charnavel and Sportiche 2016; Charnavel 2019), whereby the anaphor covers non-reflexive functions, e.g., is used as a logophoric pronoun. Indeed, the logophoric analysis has been proposed for Turkish reflexive kendi-si ‘self-3’ (Kornfilt 2001), which is much like Tatar üz-e in allowing non-local antecedents or antecedent-less configurations. Therefore, it is important to distinguish between purely reflexive and possibly logophoric uses of üz-e.

The standard assumption about logophoricity is that logophors mark reference to the logophoric center of the utterance, which different languages associate with “the source of the report, the person with respect to whose consciousness (or “self”) the report is made, and the person from whose point of view the report is made” (Sells 1987, p. 445). That is, to distinguish between logophoric and reflexive uses, we should consider contexts with non-human antecedents, as suggested in Charnavel and Sportiche (2016); Charnavel (2019); a.m.o.

First of all, both reduplicated and simple reflexive, as well as the reciprocal, allow for (local) non-human antecedents.

| (50) | a. | Xäjer, | ul | jarai | bügen | dä | üz-ei | tur-ı-nda |

| though | this | wound | today | ptcl | self-3 | about-3-loc | ||

| onıt-tır-mıj. | ||||||||

| forget-caus-neg.ipf | ||||||||

| ‘Though, this wound still reminds about itself.’ [CWT] | ||||||||

| b. | Bu | ısuli | eš-tä | üz-üz-e-ni | jaxšı | kür-sät-te. | ||

| this | method | work-loc | self-self-3-acc | well | see-caus-pst | |||

| ‘This method has proven itself in work.’ | ||||||||

| c. | Tarix | bit-lär-e | wakıjga-lar-nıi | ber-ber-se-näi | bäjlä-de. | |||

| history | page-pl-3 | event-pl-acc | one-one-3-dat | bind-pst | ||||

| ‘The pages of history linked the events together.’ [CWT] | ||||||||

As expected, in these configurations simple reflexives are semantically bound:

| (51) | Eši | mine | üz-ei | tur-ı-nda | onıt-tır-mıj, | sälamätlek | tä. |

| work | I.acc | self-3 | about-3-loc | forget-caus-neg.ipf | health | ptcl | |

| ‘Work does not let me forget it, and so does health.’ (oksloppy reading, *?strict reading) | |||||||

Importantly, in non-local contexts, i.e., in contexts where reduplicated anaphors are disallowed and simple reflexives are not semantically bound, non-human antecedents of simple reflexives are ungrammatical. Compare (52a) with a locally bound reflexive and (52b) with an intended non-local antecedent.

| (52) | a. | Bu | problemai | üz-e-neŋi | karaš-ı-n | taläp | itä. | |

| this | problem | self-3-gen | approach-3-acc | requirement | do.ipf | |||

| ‘This problem requires its own approach.’ | ||||||||

| b. | *Bu | problemai | bez-neŋ | üz-e-neŋi | karaš-ı-n | |||

| this | problem | we-gen | self-3-gen | approach-3-acc | ||||

| kullan-u-ıbız-nı | taläp | itä. | ||||||

| adopt-nml-1pl-acc | requirement | do.ipf | ||||||

| Int.: ‘This problem requires that we adopt its (specific) approach.’ | ||||||||

Charnavel (2019) argues that apparent antecedent-less uses of logophors can be accounted for under the same lines as long-distance logophors by introducing a logophoric operator in the syntactically represented pragmatic shell of the clause; this operator binds “exempt anaphors”, which derives their logophoric reading. It seems that non-bound (long-distance and antecedent-less) uses of the simple reflexive üz-e can be subsumed under the logophoric pattern too. Indeed, in antecedent-less contexts, we often find 1–2p reflexives, which is expected, since the speech act participants are natural logophoric centers. Moreover, 3p antecedent-less reflexives are attested in free indirect speech contexts like (53).

| (53) | Ilšäti | kurka | bašla-dı. | |||

| Ilshat | fear.ipf | start-pst | ||||

| Zöläjxa-apa | uz-e-ni | internat-ta | kal-dır-ırga | teli | kebek? | |

| Zulejxa-aunt | self-3-acc | orphanage-loc | stay-caus-inf | want.ipf | maybe | |

| ‘Ilshat was scared. Maybe aunt Zulejxa will put him into the orphanage?’ | ||||||

Though both anaphors and logophors are bound pronouns under Charnavel’s (2019) approach, we can still distinguish between binding by an antecedent DP and binding by a logophoric operator. In what follows, I consider the exempt anaphors as syntactically free, much like Kornfilt (2001) suggests. Thus, the Tatar simple reflexive allows for both types of uses—syntactically bound and syntactically free.

I believe that this peculiar behavior of the simple reflexive receives a principled explanation under the hypothesis about the internal structure of reflexives put forward in Kornfilt 2001 for Turkish. Kornfilt argues that the Turkish reflexive kendi-si ‘self-3’ “is actually a phrase in disguise” and this phrase, AgrP, hosts the pronominal pro in its specifier (Kornfilt 2001, p. 199). AgrP being a binding domain for pro, pro is trivially free in its binding domain irrespective of its referential index. This allows kendi-si ‘self-3’ to be coindexed with whatever local or non-local antecedent or lack a syntactic antecedent altogether.

Though this elegant hypothesis accounts for the insensitivity of the simple reflexive to syntactic binding, it cannot account for its preferences with respect to semantic binding. Additionally, it does not predict any difference between the behavior of null and overt anaphoric pronouns; however, the former support semantic binding whereas the latter disallow it, cf. (54).

| (54) | a. null pro: semantic binding | |||||

| Bez | genä | pro1pl | üz-ebez-neŋ | süz-ebez-ne | wlast’-ka | |

| we | only | self-1pl-gen | word-1pl-acc | authorities-dat | ||

| ǯitker-ergä | tiješ-bez. | |||||

| inform-inf | must-1pl | |||||

| ‘Only we have to communicate our statement to the authorities.’ (OKsloppy reading, ?strict reading) | ||||||

| b. overt pronoun: no semantic binding | ||||||

| Bez | genä | bez-neŋ | üz-ebez-neŋ | süz-ebez-ne | wlast’-ka | |

| we | only | we-gen | self-1pl-gen | word-1pl-acc | authorities-dat | |

| ǯitker-ergä | tiješ-bez. | |||||

| inform-inf | must-1pl | |||||

| ‘Only we have to communicate our statement to the authorities.’ (*sloppy reading, OKstrict reading) | ||||||

| (55) | a. null pro: semantic binding | ||||||

| Räfik | kenä | jılan-nı | pro3sg | üz-e | jan-ı-nda | kür-de. | |

| Rafik | only | snake-acc | self-3 | near-3-loc | see-pst | ||

| ‘Only Rafik saw a snake near himself.’ (OKsloppy reading, ?strict reading) | |||||||

| b. overt pronoun: no semantic binding | |||||||

| Räfik | kenä | jılan-nı | a-nıŋ | üz-e | jan-ı-nda | kür-de. | |

| Rafik | only | snake-acc | this-gen | self-3 | near-3-loc | see-pst | |

| ‘Only Rafik saw a snake near him.’ (*sloppy reading, OKstrict reading) | |||||||

Therefore, I propose that Tatar pro comes in two binding-theoretical varieties: as an anaphor and as a pronominal. The idea that the possessor of the self-reflexive is an actual anaphor has been successfully exploited by Iatridou (1988) in accounting for the agreement properties of Greek reflexives revealed in clitic doubling, cf. (56). The clitic pronoun shows agreement with the direct object, allegedly violating AAE, but in fact, Iatridou argues, it is the possessive pronoun which is an anaphor. It co-varies with its binder for phi-features, whereas the reflexive phrase is invariably 3p singular masculine.

| (56) | a. | I | Maria | ton | thavmazi | ton | |

| the.nom.f.sg | Maria | cl.acc.m.sg | admire.prs.3sg | det.acc.m.sg | |||

| eafton | tis. | ||||||

| self | her(gen.f.sg) | ||||||

| ‘Maria admires herself.’ (Iatridou 1988:(9a)) | |||||||

| b. | Egho | ton | xero | ton | eafton | mu. | |

| I | cl.acc.m.sg | know.prs.1sg | det.acc.m.sg | self | my(gen.1sg) | ||

| ‘I know myself.’ (Iatridou 1988:(9b)) | |||||||

Importantly, pro as a pronominal and pro as an anaphor have different binding domains. The pronominal pro’s binding domain is a minimal clause or DP with its own subject which contains pro. As suggested by Kornfilt (2001), this is the reflexive phrase itself. When pro is an anaphor, its binding domain extends as to the inclusion of a potential binder, but this extension cannot go beyond a minimal finite clause. Consequently, in non-local domains, the pro-anaphor is excluded, whereas the pronominal pro is available, and these uses are responsible for the exempt anaphora.25 In local configurations, both varieties of pro are available.26

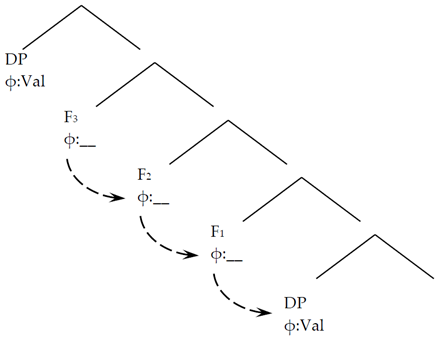

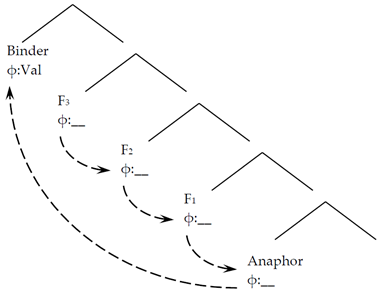

The twofold characterization of pro as anaphor or pronominal is a descriptive generalization allowing us to capture properties of simple reflexives with respect to semantic binding. However, in view of minimalist premises, it is highly desirable to eliminate binding-theoretical notions such as anaphor or pronominal from the list of primitives and to explain their specific distribution and interpretation by using mechanisms independently required in the grammar. Accordingly, I am going to make the next step and assume a valuation-based difference between anaphors and pronominals: anaphors possess unvalued phi-feature sets whereas pronominals have valued phi-feature sets. In doing so I, follow the appealing approach in the minimalist research seeking to derive binding from a general Agree operation (Reuland 2005; Heinat 2008; Kratzer 2009; Rooryck and Vanden Wyngaerd 2011; Wurmbrand 2017; Murphy and Meyase 2022; Paparounas and Akkuş, forthcoming, a.m.o.). The basic idea is that referential deficiency of anaphors follows from their featural deficiency. The anaphor enters the derivation with unvalued phi-features, which are then valued under agreement (immediate or mediated) with its antecedent, and the relation between the anaphor and the source of phi-features is interpreted as binding at LF. Semantic binding is then a hallmark of Agree-based valuation of the pronoun’s phi-features; therefore, wherever we observe a bound interpretation of the pronoun, we are dealing with agreement. A free interpretation of the pronoun signals that it entered the derivation with valued phi-features.