Abstract

Recent studies investigating whether bilingualism has effects on cognitive abilities beyond language have produced mixed results, with evidence from young adults typically showing no effects. These inconclusive patterns have been attributed to many uncontrolled factors, including linguistic similarity and the conversational contexts the bilinguals find themselves in, including the opportunities they get to switch between their languages. In this study, we focus on the effects on cognition of diglossia, a linguistic situation where two varieties of the same language are spoken in different and clearly separable contexts. We used linear mixed models to compare 32 Arabic diglossic young adults and 38 English monolinguals on cognitive tasks assessing the executive function domains of inhibition, and switching. Results revealed that, despite both groups performing as expected on all tasks, there were no effects of diglossia in any of these domains. These results are discussed in relation to the Adaptive Control Hypothesis. We propose that any effects on executive functions that could be attributed to the use of more than one language or language variety may not be readily expected in contexts with limited opportunities for switching between them, especially in younger adults.

1. Introduction

The effects of using two languages on cognition have been widely discussed in the psycholinguistic literature on bilingualism. It is widely accepted that the two languages of a bilingual are constantly active (Kroll and Bialystok 2013; Marian and Spivey 2003). In order to select the language that is appropriate to a given context, a bilingual must access domain general mechanisms that are not restricted to language processing (Green and Abutalebi 2013). These mechanisms are thought to include executive functions such as inhibition, switching and updating (Miyake et al. 2000). Significantly better performance for bilinguals compared to monolinguals in non-linguistic tasks tapping into these functions have led several researchers to claim cognitive advantages in bilinguals, which stem from their long-term greater reliance on these executive functions; however, this claim remains controversial, especially as a far as young bilinguals are concerned (for a comprehensive review, see Valian (2015)). Much less is known about the effects on cognition of speaking two varieties of a single language, in linguistic situations such as bidialectalism and diglossia; indeed, the limited available evidence has only added to the controversy in the field (Alrwaita et al. 2022). Many explanations have been put forward to explain the contradictions in the evidence, including some relating to the type and frequency of opportunities for switching between languages/varieties. One of the most prominent proposals is the Adaptive Control Hypothesis (Green and Abutalebi 2013), which predicts that different bilingual conversational contexts would require different degrees of reliance on executive functions, and as a result, modulate the extent of the relevant effects on domain general cognition (Bialystok et al. 2006; Costa et al. 2009). One of the contexts that the Adaptive Control Hypothesis describes is the Single Language Context (SLC), where limited opportunities for language switching occur, and as a result minimal, if any, effects on cognition should be expected compared to the Dual Language Context which allows for more switching (for details, see Section 1.3). In the present study, we focus on Arabic diglossia as a case for studying the effects of using two varieties of the same language on cognition. Arabic diglossia offers a good example of an SLC which provides limited opportunities for switching between the two varieties, allowing to test the predictions of the Adaptive Control Hypothesis for SLCs. The remaining sections of this introduction define diglossia, summarize the evidence on the effects of two languages, or two varieties of a single language, on cognition in young adults, before outlining the aims of the present study.

1.1. Defining Diglossia

According to Ferguson (1959), diglossia refers to the coexistence of two or more related varieties of the same language in one community. Ferguson described four linguistic situations as prototypes of diglossia, including Standard/Colloquial Arabic (in the Arabic-speaking world), Katharevousa/Dhimotiki (in Greece), Standard/Swiss German (in German), and Standard/Creole French (in Haiti). In such situations one variety functions as the “standard” formal language, while the other is typically a regional dialect. The two varieties are very divergent: the standard or “high” (H) variety is highly codified, more grammatically complex, often the language used for written literature or for educational or religious reasons, and learned through formal education. As a result, a person speaking the high variety is often seen as more educated or of higher status. The “low” (L) variety tends to be less grammatically complex, used for everyday conversations in informal settings, and is learnt at home.

As already mentioned, one of the prototypical diglossic situations is diglossia in Arabic-speaking countries. Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is the common high variety which is used across Arabic-speaking nations in formal contexts and found in the literature, governance, religious discourse and formal speeches. Low varieties of Arabic, known as colloquial dialects, vary between countries and are used in informal communication, in music, films, sport and everyday conversation (Albirini 2016). These two varieties also have different levels of language complexity. For example, H includes an elaborate system of inflections, such as number, gender, person, case and definiteness. This results in a more complex grammatical phrases in H compared to L. L, on the other hand, is known to have a simplified morphological system which lacks inflections (Albirini 2016). From a syntactic perspective, H is known to have a SVO word order while L has an SVO order (Boudelaa and Marslen-Wilson 2013).

In contrast to the disappearing diglossic situations in other countries (e.g., Greece) (Frangoudaki 1992), diglossia remains a defining characteristic of the Arab world. This serves to maintain the Islamic heritage and the language of the Qura’an (Amara and Mar’I 2002), enforces a sense of nationalism and functions as a unifying force amongst Arab countries (Palmer 2008). It is worth noting that Arabic diglossia takes different forms in different countries, and several factors affect the local Arabic variety that is spoken. For example, Rosenhouse and Goral (2006) divided Arabic dialects on the basis of four categories: First, geographical dimension, separating Eastern dialects, those spoken in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Kuwait, Oman and the United Arab Emirates, from Western dialects, including those spoken in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya; second, sociolinguistic background, including Bedouin vs. al-Hadar backgrounds; third, religious background (Islam, Christianity or Judaism); and last, gender, age and education (Alsahafi 2016). It is important to note that mutual intelligibility often exist between local varieties, and it has been suggested that the more geographically close countries are, the more intelligibility is found between the speakers of these countries’ varieties. It has also been reported that Arabic speaking individuals often modify their variety to approach another individual’s variety (Giles 1973; S’hiri 2002). This usually happens during intralingual contact and the process is referred to as convergent accommodation (Alsahafi 2016). For instance, dialects of Western Arab countries, such as Tunisia and Morocco, have diverged from Standard Arabic more noticeably than dialects of Eastern Arab countries, such as Jordanian or Palestinian. Thus, it is expected that Moroccans, for instance, would modify their dialect when speaking to Jordanians (Alsahafi 2016). Diglossia in the Arab world, therefore, constitutes an ideal candidate for studying the effects of using two varieties of a language on cognition, a phenomenon that remains under- researched (Alrwaita et al. 2022).

1.2. The Effects of Bilingualism on Executive Functions

Before considering the effects of diglossia on cognition, it is useful to review the evidence relating to bilingualism, which has received greater attention from researchers. As discussed earlier, the juggling of two languages in the bilingual mind is thought to activate domain general cognitive mechanisms that support executive functions. Thus, bilinguals are “trained” to prevent interference from the non-target language in order to use the target language (Bialystok et al. 2012; Carlson and Meltzoff 2008). The need to constantly inhibit interference is thought to be the origin of the reported enhanced inhibition abilities in bilinguals compared to monolinguals, which are seen even in non-linguistic tasks (Calvo and Bialystok 2014; Costa et al. 2008; Kroll and Bialystok 2013; Ross and Melinger 2017). Inhibition, the ability to suppress attention to, or ignore, misleading information in order to attend to an appropriate target, along with switching, the ability to switch from one task to another, and updating, the ability to temporarily hold and update information in working memory for processing, are fundamental to executive functions (Miyake et al. 2000) and the most commonly investigated domains in bilingual studies. However, some controversy still exists on whether these effects are reliable, especially as far as young adults are concerned. For example, while several studies have reported benefits for bilinguals across a variety of tasks tapping different executive function domains (Bialystok 2011; Costa et al. 2008, 2009; Emmorey et al. 2008; Soveri et al. 2011; Treffers-Daller et al. 2020), a good number of studies has also failed to find such effects in some or all of executive function domains (Bialystok et al. 2012; Hernández et al. 2013; Kousaie and Phillips 2012; Paap and Greenberg 2013; Scaltritti et al. 2017); with some authors suggesting that benefits are most commonly found in older bilingual adults (Hilchey and Klein 2011). The lack of a consistent advantage for young adults has been explained in terms of the peak performance hypothesis, which states that, in contrast to children and older adults, young adults are at the peak of their cognitive performance (Bialystok et al. 2005), making it difficult to find evidence of advantages in one group over another (Paap et al. 2015).

However, other suggestions have also been put forward regarding the discrepancies of the findings in young adults, including how bilinguals are defined in each of these studies (Surrain and Luk 2019), as well as the quantity and quality of bilingual language use (Yang et al. 2016), which is the main focus of the present study. Indeed, it is perhaps surprising that the inconsistent findings in the literature have not been systematically linked to differences in linguistic context or amount of language switching of the bilingual participants studied. It has recently been suggested that the extent to which bilinguals engage their executive functions to resolve conflict between their two languages may be key to whether any domain general cognitive effects should be expected in bilinguals. According to the Adaptive Control Hypothesis (ACH) (Green and Abutalebi 2013), there are three conversational contexts that vary in the amount of switching between a bilingual’s two languages, each impacting on executive functions differently: (a) the Single Language Context, where speakers use each language in a different context (e.g., one language at home and another at work); (b) the Dual Language Context, where speakers use the two languages in the same context, and switching occurs between sentences but not within sentences; (c) the Dense Code-Switching context, where speakers freely switch between the two languages even within the same sentence. According to the ACH, Dual Language Contexts require the most inhibitory control, followed by Single Language Contexts and the Dense Code-Switching contexts; therefore, Dual Language Contexts should result in particularly enhanced executive functions in bilinguals (Green and Abutalebi 2013). Following the Adaptive Control Hypothesis categorization, diglossia, and Arabic diglossia in particular, is closest to a Single Language Context, considering the exclusive contexts in which the varieties are used and the minimal switching between the two varieties. Therefore, Diglossia constitutes the appropriate test case to study the effects on cognition of such linguistic contexts.

1.3. The Effects of Speaking Two Varieties of One Language on Executive Functions

Only a few studies have investigated the effects of speaking two varieties of a single language on executive functions of young adults. We first review the evidence from bidialectalism, a linguistic situation that is very similar to diglossia but where the typical H and L varieties are better represented as a standard variety and a local dialect (Papapavlou and Pavlou 1998). Scaltritti et al. (2017) investigated whether the amount of exposure to the two varieties of a language relates to bidialectals’ performance in inhibitory control tasks. In two experiments, Scaltritti et al. used a questionnaire about the participants’ exposure to standard Italian and a local Venetian dialect, which they used to calculate a dialect familiarity score. Scaltritti and colleagues reported no significant correlation between this score and participants’ performance in the Flanker and Simon tasks; moreover, they reported no benefits in these tasks for bidialectals when compared to Italian monolinguals, in line with studies that reported no benefits in bilingual young adults (Kousaie and Phillips 2012; Paap and Greenberg 2013). Scaltritti et al. (2017) argued that the limited opportunities for switching (which however was not measured directly) between the different language varieties in the Italian-Venetian context explains the lack of a bidialectal advantage in this study. In a different study, Poarch et al. (2019) tested the performance of a group of Swabian-German bidialectals aged 18–26 in the Simon and Flanker tasks. Poarch and colleagues used a dialect use questionnaire to place their participants in a continuum of dialect dominance, from Swabian-dominant to balanced Swabian-German speakers. Poarch et al. reported that dialect dominance negatively correlated with both Simon and Flanker effects, meaning in that the more dominant the participants were in Swabian, the better the cognitive control they demonstrated, which went against their original predictions. This finding was interpreted as evidence that using the non-standard dialect more than the standard one enhances inhibitory control more than equal use of the two dialects may do, directly contradicting the suggestions by Scaltritti et al. (2017). It is also worth noting that in Scaltritti et al. (2017) the lack of inhibitory control was linked to less switching, relating to less usage of the Venetian dialect.

To date, only one study has investigated the effects of diglossia on executive functions in young adults (Antoniou and Spanoudis 2020). This study was conducted in Cyprus, where Modern Standard Greek functions as the high variety and Cypriot Greek as the low variety (Antoniou et al. 2016). Diglossic and multilingual benefits were explored across the executive functions domains of inhibition, switching and updating (Miyake et al. 2000) by comparing diglossics (speakers of Cypriot Greek and Modern Standard Greek), multilingual participants (speakers of Cypriot Greek, Modern Standard Greek and another language) and monolingual speakers of Modern Standard Greek on the Stroop, Flankers, Color-Shape, N-back and Corsi block tasks. Antoniou and Spanoudis reported both multilingual and diglossic benefits across all executive functions components, but stopped short of reporting how these relate to opportunities for switching between languages. Notably, while these findings contradict the results of studies in bilinguals and bidialectals of a similar age, they corroborate those of Antoniou et al. (2016), who found diglossic benefits in Cypriot-Greek children. Some additional corroborating evidence also comes from a recent study comparing Arab diglossic older adults to bilinguals and monolinguals, which reported significant effects of diglossia, including a diglossic benefit in tasks tapping inhibitory control and switching (Alrwaita et al. n.d.). The authors interpreted their findings as the outcome of long-term experience in inhibiting the non-target language at SLC contexts.

The discrepancy between the evidence from diglossia and bidialectalism, two very similar linguistic situations, is intriguing, and potentially related to the different usage of the two language varieties in bidialectal and diglossic settings. Most importantly, the evidence from the few studies on diglossia contradicts the suggestion that executive control demands, and the related cognitive benefits, should be low in diglossic environments, given the clear separation between the contexts in which each variety is used.

1.4. The Role of Context and Switching Opportunities

As mentioned, both diglossia and bidialectalism can be considered to constitute SLCs in the Adaptive Control Hypothesis terms (Green and Abutalebi 2013); both offer limited opportunities for switching between the two varieties, which are used in a specific context. For these reasons, the Adaptive Control Hypothesis predicts that SLCs have minimal effects on executive functions compared to dual language contexts, which feature greater language switching requirements. The predictions of the Adaptive Control Hypothesis are supported by studies highlighting the role of language switching in modulating performances in executive function tasks and by the observation that benefits of bilingualism are more likely to be found in tasks that require more switching (Bialystok et al. 2006; Costa et al. 2009). It is therefore important to consider why, in conditions where we would expect to see minimal or no benefits (diglossic and bidialectal environments), contradictory results have been found in the only available study of diglossia (Antoniou and Spanoudis 2020).

While the bidialectal and diglossic situations appear to be similar, it is worthwhile considering the differences in how the H and L varieties function in each case, and how often speakers switch between them. First, bidialectalism develops in diglossic situations when H takes over L, meaning that the high variety is used for both formal and informal purposes (Rowe and Grohmann 2013). Second, diglossic native speakers are raised in homes where only L is used (Keller 1973). Finally, in bidialectalism H is seen as the more prestigious variety and learning it is considered more important than learning L, while in diglossia both varieties are expected to be learned (Rowe and Grohmann 2013). Linguistically, in bidialectalism H and L are similar in complexity, while in diglossia H is syntactically and grammatically more complex than L (Ferguson 1959).

There are also some differences in the functional uses of bidialectalism and diglossia, which suggest that diglossia better corresponds to an SLC than bidialectalism does. In diglossia, switching between the two dialects depends entirely on the activity, as all users understand both varieties, although the level of understating of the H variety can vary with education. However, in bidialectalism the use of the two varieties is overlapping (Shapiro et al. 1989); which means that both H and L can be used for formal purposes. It follows that we should be less likely to observe cognitive benefits in diglossia than in bidialectalism. As described above, the limited available evidence points in the opposite direction, suggesting that broad brush categorizations of environments as diglossic or bidialectal might not necessarily describe the important characteristics of those environments. For example, in diglossia, exposure to and usage of the two varieties might vary considerably across different environments (Kaye 2001). Given that lower exposure to one variety results in less switching between the two varieties, and therefore to less enhancement of executive control abilities (Kirk et al. 2014; Scaltritti et al. 2017), relative use of the two varieties in diglossia is likely an important factor to consider. Interestingly, the diglossic situation in Cyprus has been recently characterized as diglossic transitioning into type B diglossia or “diaglossia”, where the use of the standard or H dialect is no longer restricted to written purposes, but also extends to oral communication. In such cases, the extent of code-switching depends more on the situation than on the activity (speaking/writing) (Auer 2011; Rowe and Grohmann 2013), a situation that is more similar to bidialectalism than true diglossia. This issue highlights the need for studies of diglossia in environments other than Cyprus.

Arabic offers the ideal test case for investigating the effects of diglossia on executive functions. First, in typical diglossia there is a clear separation between the contexts in which each variety is used, which should limit enhancement to executive functions (Costa et al. 2009). This separation is strongly enforced in Arabic diglossia, where there is rigid use of the high variety for formal purposes and the low variety for informal purposes (Albirini 2016), ruling out the possibility of an overlap in their use (Kaye 2001). According to Albirini (2016), even the most educated Arabs do not use the formal dialect (H) for informal purposes, or vice versa; doing so would be a clear violation of sociolinguistic norms. In contrast, switching between the high and the low dialects is very frequent in Cyprus, even when the speaker does not intend to switch (Pavlou 2004). Second, some Arabic speakers are rarely exposed to the high variety; even educated Arabs would find it difficult to hold conversations entirely in the high variety, and understanding it is even more difficult for uneducated Arabs (Kaye 2001). Again, this implies less switching between the two dialects and, as a result, limited effects on executive functions, if any at all. Arabic therefore offers a clear example of diglossia in which two language varieties are used in an SLC.

2. This Study

To investigate whether Arabic diglossia has an effect on executive functions, we compared young Arab diglossics (in their early to late twenties on average) to English-speaking monolinguals in a series of tasks that have been reported to demonstrate effects of diglossia in older adults (Alrwaita et al. n.d.), namely the Flanker, Stroop, and Color-shape tasks. If our results replicate previous evidence for diglossic benefits (Alrwaita et al. n.d.; Antoniou and Spanoudis 2020), this would suggest that diglossic situations, in general, enhance performance in tasks tapping executive functions, irrespective of the amount of language switching (which, as discussed, differs between Cyprus and the Arab world) or the age of the participants. Conversely, if we fail to report any effects of diglossia, and taking into account the findings from older Arab diglossics, this would constitute evidence for the peak performance hypothesis even for young diglossics in strict SLCs as they materialise in the Arab world.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

70 young adults participated, 32 Arabic speaking diglossics (22 females, mean age = 29.6, SD = 5.7), and 38 English speaking monolinguals (34 females, mean age = 21.6; SD = 5.6)). Arabic speaking adults were recruited from the Prince Sultan University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. English speaking adults were recruited from the School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences at the University of Reading. One English-speaking individual was excluded for having bilingual parents and scoring significantly higher than other monolinguals in the Language and Social Background Questionnaire (LSBQ) (Anderson et al. 2018) (see below). Our final monolingual group consisted of 37 participants (34 females, mean age = 21.7; SD = 5.7) and was significantly younger than the diglossic group (F(1,67) = 33.8, p < 0.001).

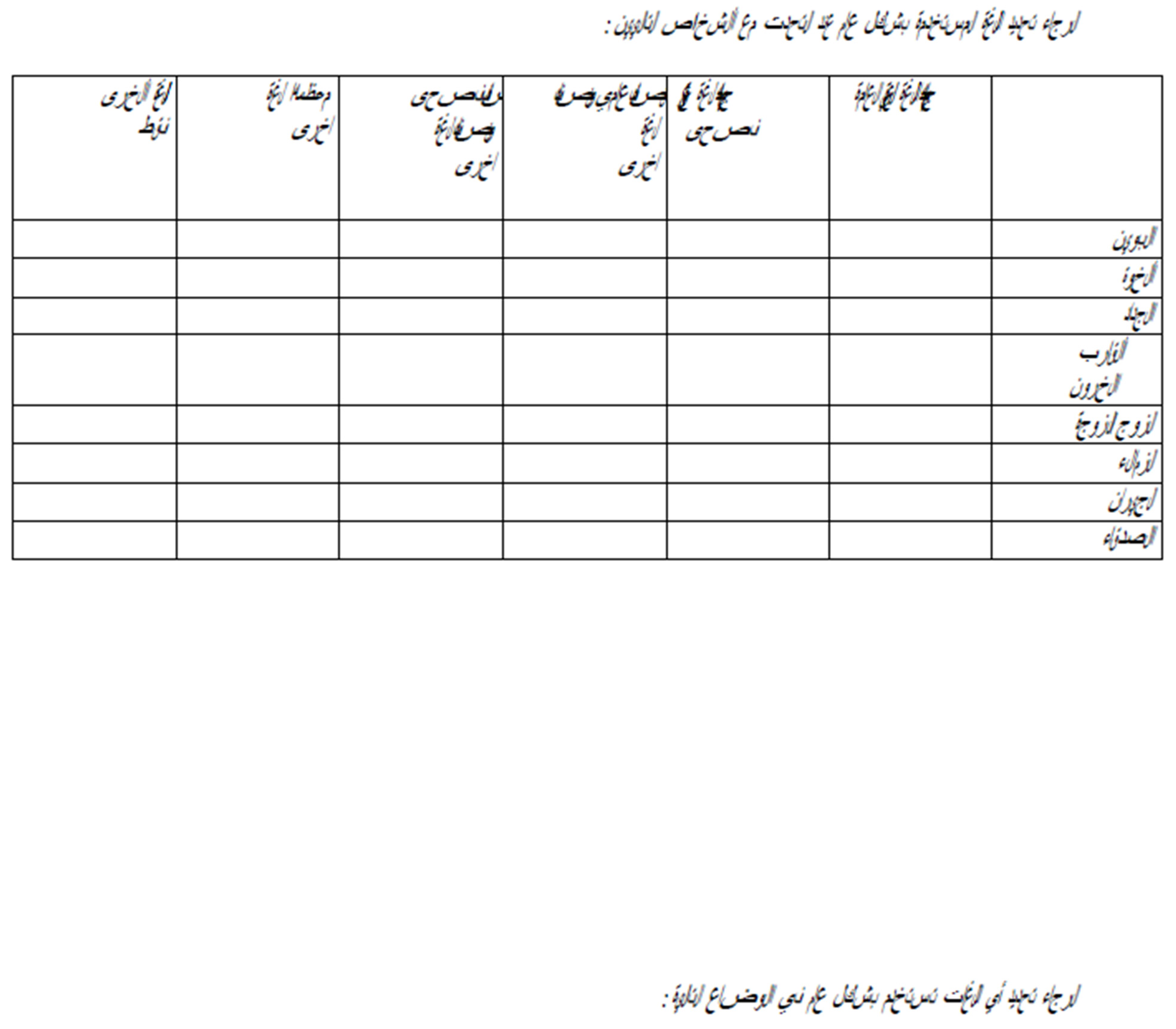

3.2. Language Background and Proficiency Measures

Prior to the study, our monolingual participants were assessed using the Language and Social Background Questionnaire (LSBQ) (Anderson et al. 2018). The LSBQ examines the degree to which, and the domains in which, participants use English, and other languages (if applicable), in their daily lives. To measure proficiency, the questionnaire includes self- rating questions about reading, writing and listening skills in English/other languages. Factor scores were calculated for each participant for three domains: English proficiency, non- English social use, non-English home use. A composite ‘bilingualism score’ was computed by summing the factor scores weighted by the variance in each factor. According to Anderson et al. (2018), those with composite scores below −3.13 should be classified as monolinguals, while composite scores above 1.23 indicate bilinguals. Our monolingual young adults had an average composite score of −8.29 (SD = 1.2; range: −9.66 to −4.91), meaning they could all be safely classified as monolinguals according to the LSBQ. Moreover, monolinguals scored low in all three domains of switching found in the LSBQ, including switching with family (mean: −0.93, SD: 0.53, range: −1.12 to 0.96), switching with friends (mean: −0.44, SD: 0, range: −0.44 to −0.44), and switching in social media (mean: −0.45, SD: 0.9, range: −0.47 to −0.08).

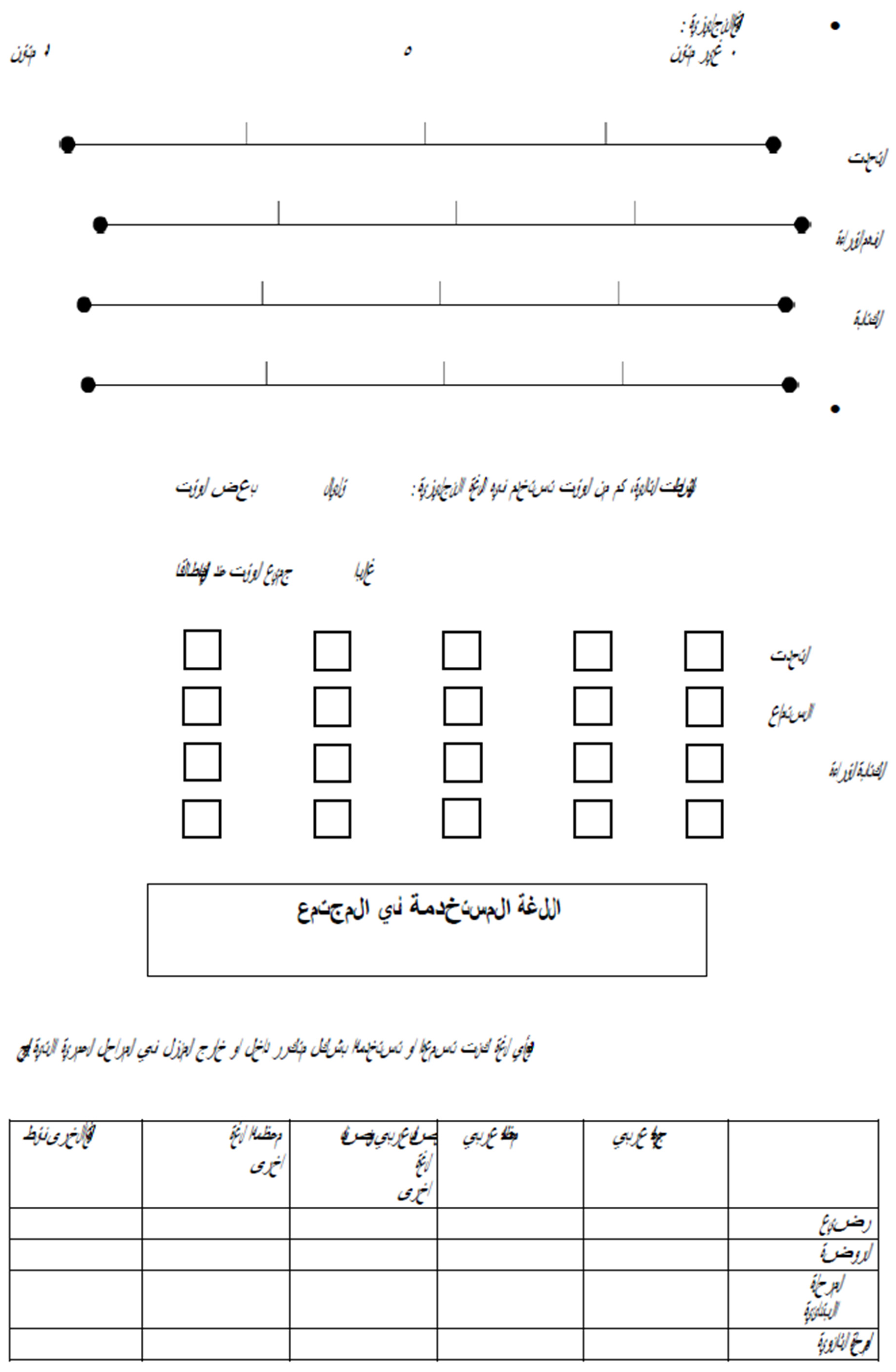

To ensure that our diglossic group were indeed diglossics (knowing both the standard and the spoken variety), we adapted the LSBQ to investigate the degree of variety use, and the domains in which each variety was used (see Appendix A). Given that Standard Arabic is the language used for writing and reading, the Arabic version of LSBQ was conducted in Standard Arabic. Diglossics achieved an average composite score of −0.22 (SD = 2.6; range −6.62–4.92). According to Anderson et al. (2018), this score lies in the grey area between bilingualism and monolingualism. Crucially, results from the LSBQ revealed low scores in the three domains of switching, including with family (mean: −0.57; SD: 0.60; range −1.12 to 0.96), with friends (mean: −0.025; SD: 0.04; range (−0.44 to 1.09), and in social media (mean: 0.12, SD: 0.55; range −0.47 to 1.21). This shows that diglossics belong to an environment with limited amounts of switching (SLC); however, they significantly engage to switching more than monolinguals do in all three domains (all ps < 0.05).

Because the level of knowledge of Standard Arabic differs according to the level of education and exposure to the standard dialect (Kaye 2001), proficiency in Standard Arabic was measured using a vocabulary test designed by Masrai and Milton (2019). This pen-and-paper test comprises a checklist of 100 of the 50,000 most common Arabic words (generated by Kilgarriff et al. (2014), from the web-based corpus of Arabic (Sharoff 2006)). The test is divided into two parts, each including 20 words and 20 non-words intermixed. Participants indicated if they recognized each word by responding either “yes” or “no”. The duration of the test is between 10–15 min. To estimate participant’s vocabulary size, measured as words known out of 50,000 words, all “yes” answers to real words are given a score of 500 to form an unadjusted vocabulary score, and each “yes” answer to a false word deducts 2500 points from the unadjusted score to form an adjusted vocabulary score. The final adjusted score gives the participants total vocabulary knowledge. Based on this, our diglossic group had an average of 87.59% (SD = 12.17) of “yes” responses to real words, an average of 5.25% (SD = 3.69) to “yes” responses to non-words, and an estimated average of 30,672 (SD = 7329; median = 30,375; range 15,000–42,000) known words. No one was excluded from the diglossic group based on this score, as they all demonstrated at least basic competency in standard Arabic (Masrai and Milton 2019).

3.3. Executive Function Tasks

Our tasks tapped on the executive function domains of inhibition (Flanker and Stroop) and switching (Color-shape). The tasks were delivered using E- prime 2.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Sharpsburg, PA, USA). All tasks were presented in a 15.6-inch computer screen, and all participants were tested in private rooms.

3.3.1. Inhibition-Flanker

This task had three conditions: Congruent, Incongruent and Neutral. In all conditions, a central arrow appeared on the screen and participants were asked to indicate if the arrow pointed to the right or left by pressing either (<) or (>) buttons on the keyboard. Participants were instructed to respond as fast and accurately as possible. In the Congruent condition, there were surrounding (flanking) arrows, which pointed in the same direction as the target central arrow (<<<<<). In the Neutral condition, the target central arrow appeared with dashes on the left and the right sides (--<--). In the Incongruent condition, there were surrounding arrows pointing in the opposite direction to the target central arrow (>><>>). Forty-four trials of each type were distributed across four blocks, each including 33 trials, 11 per condition, presented in a random order. Each trial began with a 250 ms fixation cross, followed by a stimulus lasting for 5000 ms, or until a response was provided. Trials were separated by a blank screen which appeared for 250 ms.

3.3.2. Inhibition-Stroop

In this task, a single word appeared on the screen and participants were asked to decide the color in which the word was written. The task consisted of three conditions: Congruent, Incongruent and Neutral. In Congruent trials, color words were presented that were consistent with the ink color; for example the word “green” was presented in green ink. In Neutral trials, non-color words (e.g., “dry”) were presented in different ink colors (red, green or blue). In Incongruent trials, color words were presented in inconsistent ink color; for example, the word “green” was presented in red ink. The three different colors (red, green and blue) were assigned to three adjacent keyboard buttons and participants responded by clicking the corresponding button.

48 trials of each type were distributed across three blocks, each consisting of 48 trials in random order, with a total of 144 trials. Each trial began with a 250 ms fixation cross, followed by the presentation of the word for a maximum of 5000 ms, or until a response was provided. For Arabic-speaking participants, the same task was administrated translated in Arabic.

3.3.3. Switching–Color-Shape

In this task, participants were presented with three possible patterns in either blue, green or red. There were three blocks. First, in the color block, two patterns appeared on the screen and participants had to decide whether the patterns were in the same or different colors. Second, in the pattern block participants were presented with two patterns and were asked to decide whether they were the same or different. Third, in the switching block participants had to switch between attending to the color or the pattern. In each trial, a word (color/pattern) was presented at the top of the screen, indicating whether color or pattern should be responded to. To respond, participants had to press the S button on the keyboard for “same”, or the D button for “different”.

There was a total of 124 trials. The blocked color task and blocked pattern task each included 31 trials. The switching block included 62 randomized trials consisting of 31 ‘Stay’ trials, where participants were asked to attend to the same property (color/pattern) as the previous trial, and 31 “Change” trials, where participants had to switch to attending to the other property. Each trial began with a 100 ms central fixation cross, followed by a stimulus presentation until a response was detected. There was a 250 ms blank screen between trials.

4. Results

Analyses of accuracy and reaction time (RT) data were run using generalized linear mixed-effects models (with a binomial link function for Accuracy data) and linear mixed effect models (for RT data) from the statistical package lme4 (Bates et al. 2015), in R studio (version 4.0.3). Reaction times in the outlier data were removed by using a cut-off of 2 standard deviations above or below the task median. Because reaction times were not normally distributed, they were log- transformed prior to the analysis.

Model fitting followed the same procedure for all data. Age was entered as a covariate. Task Condition (e.g., congruent, incongruent, neutral; stay or change trials) were entered as main effects. Group (monolingual or diglossic) was entered as a main effect. We also tested the interaction between Group and Condition (i.e., whether monolingual or diglossic participants responded to the task conditions differently). First, a maximal model was fit with random intercepts for participants and correlated random slopes for within-subject conditions. If there were convergence issues with the maximal model, the first step was removing correlations between random effects. If convergence issues persisted (as they did for all models that initially had convergence issues for the maximal model) we then removed random slopes and ran a model with participant intercepts only. We compared model fit for the maximal model and the final simplified model, and not any differences in the model output where the simplified model did not fit the data as well as the maximal model. Where a factor had more than two levels (Flanker and Stroop tasks with incongruent, congruent and neutral conditions) we relevelled the reference factor to extract all possible comparisons between conditions, and used emmeans (Lenth et al. 2021) to report the relevant comparisons for the interaction between group (diglossics vs. monolinguals) and condition (incongruent, congruent, neutral).

4.1. Flanker

4.1.1. Accuracy

A maximal model with random intercepts for participants and slopes for condition varying over participant did not converge. We removed correlations for the random effects and re-ran the model, but convergence issues were again present. A model with participant intercepts only converged. The maximal model was a better fit to the data than the intercepts only model (X2 = 12.985, df = 5, p < 0.05). Between the maximal and intercept only model, the only difference in significant results was that the maximal model did not find a significant difference between the Incongruent and Neutral conditions (Est = 0.646, SE = 0.424, Z = 1.525, p = 0.13). We report the results from the intercept only model (see Table 1), and interpret the main effect difference between Incongruent and Neutral conditions with caution.

Table 1.

Accuracy results for the Flanker task.

Results showed a main effect of Age (Beta = 0.074 (0.033), z = 2.24, p < 0.05) with older participants having higher accuracy. There was a difference between Congruent and Incongruent conditions (Beta = −0.84 (0.29), Z = −2.909, p < 0.005) with higher accuracy in the Congruent condition. There were no other significant main effects or interactions.

4.1.2. Reaction Times

For the RTs analysis, all incorrect trials were removed, affecting 7% of the trials pf the Diglossics and 4% of the trials of the Monolinguals.

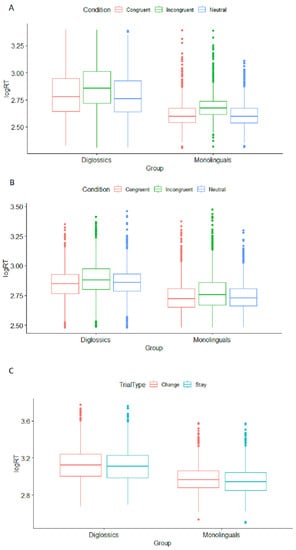

Figure 1A illustrates RTs data for the Flanker task. The maximal model for Flanker RTs gave a convergence warning, which was repeated when the model was run without correlated slopes. An intercept only model converged. The maximal model was a better fit to the data (X2 = 152.36, df = 5, p < 0.001) and the intercept only model showed marginally significant interactions where the maximal model did not. We therefore report the maximal model here, rather than report results from the intercept only model that may be spurious. The reported maximal model shows difficulties with convergence hence the large dfs reported for some comparisons (Table 2); note also the high correlations between intercepts and slopes, indicating that the slopes do not add substantial information over and above the intercepts for some conditions.

Figure 1.

Reaction times for Diglossics and Monolinguals across conditions for (A) Flanker, (B) Stroop and (C) Color-shape tasks.

Table 2.

Reaction time results for the Flanker task.

All task conditions showed significant differences, with RTs in the congruent condition being faster than those in the incongruent condition (Beta = 0.08 (0.008), t (68.1) = 9.781, p < 0.001), but slightly longer than those in the Neutral condition (Beta = −0.012 (0.005), t (221.8) = −2.51, p < 0.05). RTs in the incongruent condition were significantly longer than those in both the congruent and neutral conditions ((Beta = 0.074 (0.033), z = 2.24, p < 0.05)). There was a main effect of group, with Monolinguals having faster RTs than Diglossics (Beta = −0.15 (0.035), t (70.91) = −4.32, p < 0.001). There was no significant interaction between Group and task Condition.

4.2. Stroop

4.2.1. Accuracy

A maximal model with random intercepts for participants and slopes for condition varying over participant did not converge. We removed correlations for the random effects and re-ran the model, convergence issues were again present. A model with participant intercepts only converged. The intercept only model and the maximal model did not differ in how well they fit the data (X2 = 2.6328, df = 5, p = 0.76). We report results from the intercept only model. There were no significant effects (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Accuracy results for the Stroop task.

4.2.2. Reaction Times

All incorrect trials were removed. This affected 2% of the trials of the Diglossic group, and 3% of the trials of the Monolingual group.

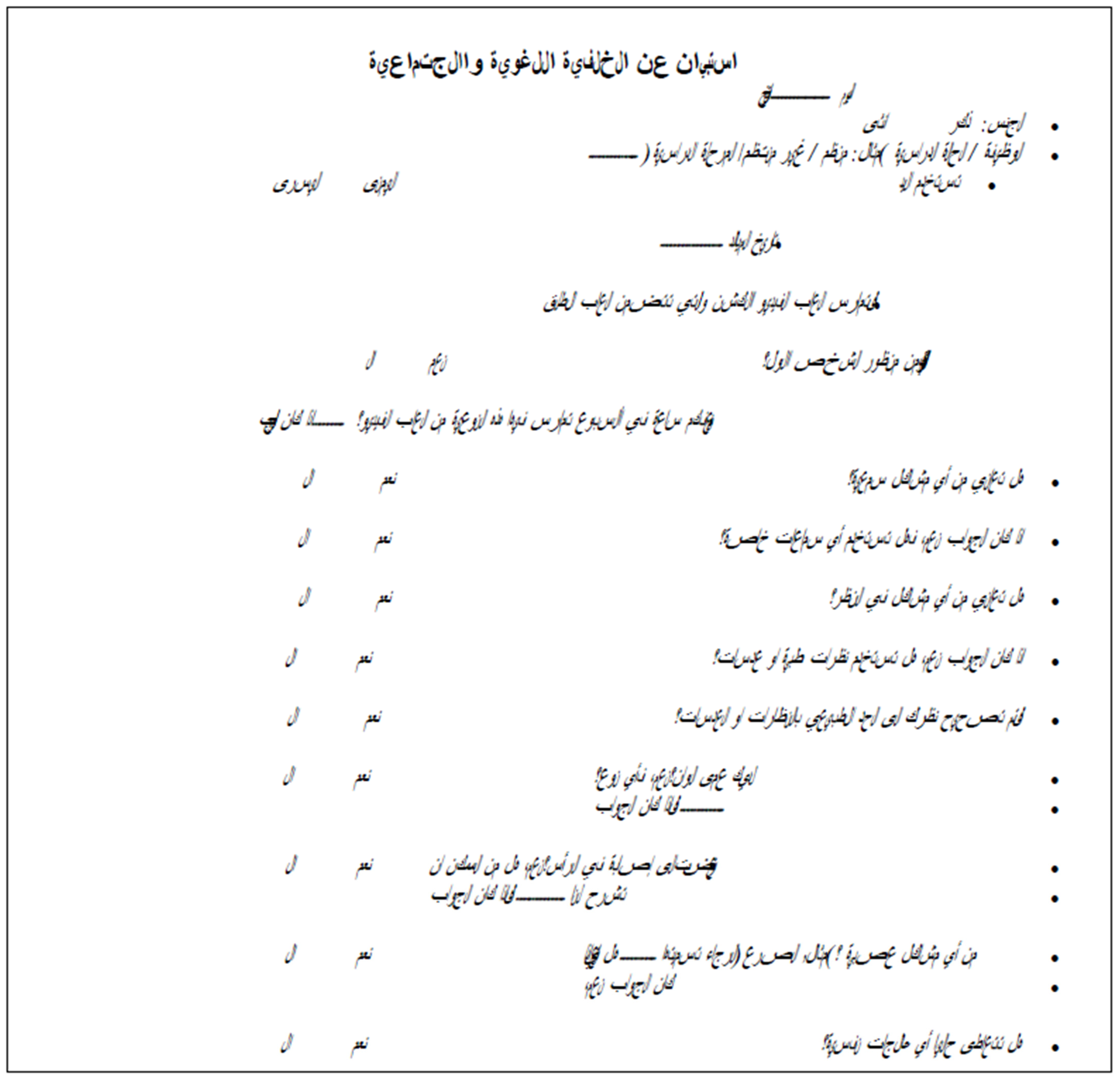

The maximal model with random intercepts and slopes for both subject and condition, converged without errors (see Table 4). Figure 1B illustrates RT data for the Stroop task.

Table 4.

Reaction time results for the Stroop task.

There were significant main effects for all task Condition comparisons. RTs in the congruent condition were faster than RTs in the Incongruent condition (Beta = 0.04 (0.005), t (67.3) = 7.385, p < 0.001), and faster than RTs in the Neutral condition (Beta = 0.03 (0.005), t (67.7) = 2.74, p < 0.01). RTs in the Incongruent condition were slower than RTs in the Neutral condition (Beta = −0.03 (0.006), t (52.89) = −4.486, p < 0.001). There was a main effect of group, with Monolinguals having faster RTs than Diglossic participants (Beta = −0.18 (0.006), t (73) = −5.265, p < 0.001). There were no significant interactions between Group and Condition.

4.3. Color-shape

4.3.1. Accuracy

The maximal model for Accuracy gave a convergence warning, which was repeated when the model was run with un-correlated slopes. When the model was run with intercepts only, no convergence warnings were given. The maximal model fit the data better than the model with intercepts only (X2 = 76.441, df = 55, p < 0.05). However, the maximal model was clearly unreliable as all predictors were reported as highly significant with very large z values. Therefore, we report the model with intercepts only (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Accuracy results for the Color-shape task.

There was a significant main effect of Condition, with Change trials having lower accuracy than Stay trials (Beta = 0.84 (0.26), z = 3.196, p < 0.005). There were no other significant effects.

4.3.2. Reaction Times

Along with extreme values, all incorrect trials were removed affecting 3%of the trials of the Diglossic group, and 6% of the trials of the Monolingual group.

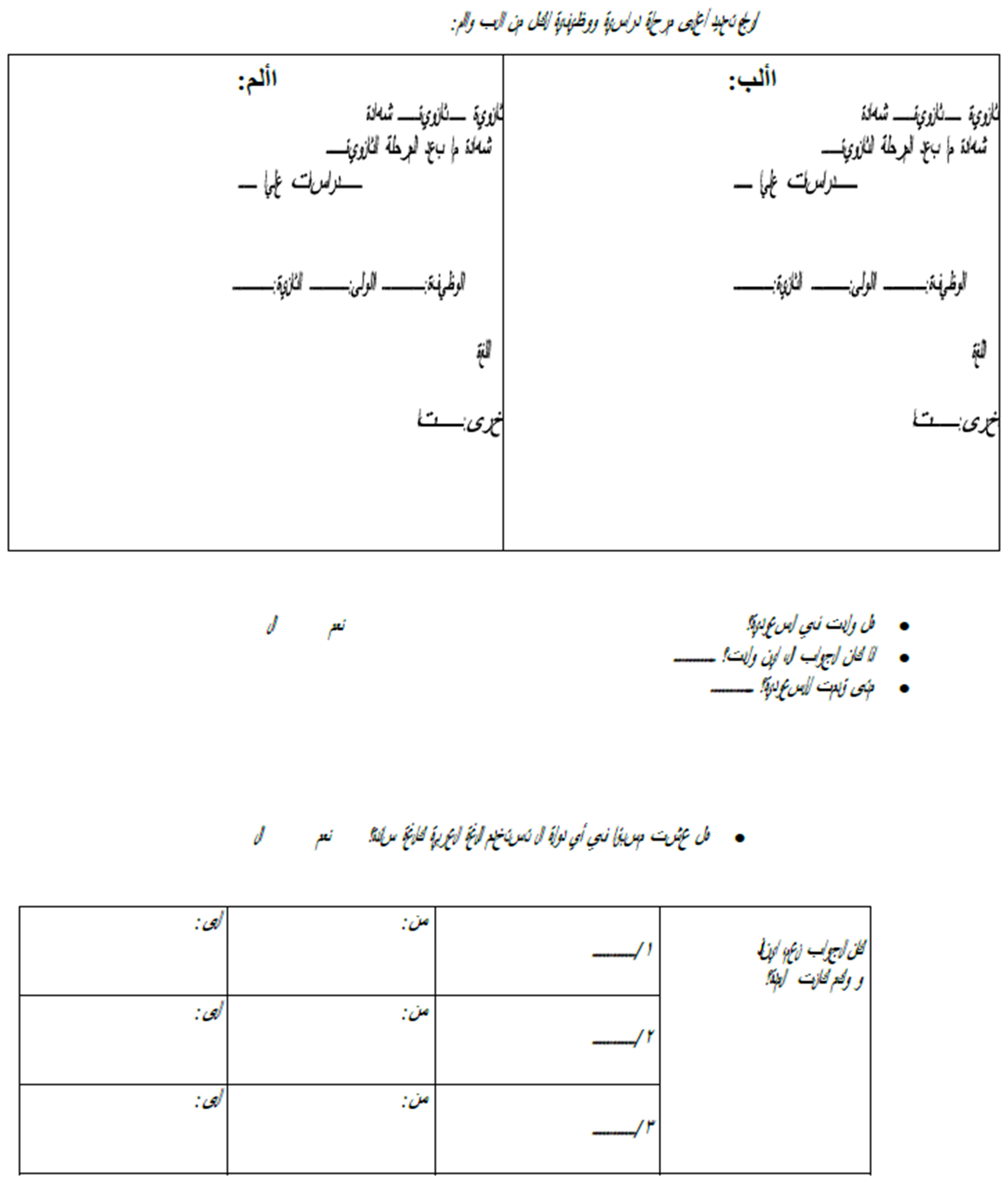

Figure 1C illustrates RTs data for the Switching task. The maximal model for Switch RTs gave a convergence warning, which was repeated when the model was run with un-correlated slopes. We ran the model with intercepts for participants only, and this gave no convergence warnings. The intercept only model fit the data as well as a model with uncorrelated slopes (X2 = 0.1, df = 2, p = 0.9512). We therefore report the results from the model with intercepts only (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Reaction time results for the Color-shape task.

There was a significant main effect of condition (Beta = −0.013 (0.005), z = −2.459, p < 0.05), with RTs in the Change condition being slower than those in the Stay condition. There was a significant main effect of Group (Beta = −0.132 (0.031), z = −4.2, p < 0.001), with Monolinguals having faster RTs as compared to Diglossics.

4.4. Continuous Experience-Based Factors as Predictors of Diglossics’ Performance

Following up from studies that used measures quantifying the bidialectal experiences as continuous predictors of their participants’ performance (Poarch et al. 2019; Scaltritti et al. 2017), we ran two sets of regression analyses on the diglossics’ data using our own measures as predictors of the Flanker effect (Incongruent-Congruent), the Stroop effect (Incongruent-Congruent), and the Switch effect (Change-Stay), by adding age and sex as covariates. The first measure was diglossics’ proficiency in Modern Standard Arabic as measured by the Arabic vocabulary test. These analyses did not yield significant results for the Flanker effect (p = 0.63), the Stroop effect (p = 0.593), and the Switch effect (Change-stay) (p = 0.63). The second measure was the diglossic LSBQ composite score. These analyses did not yield significant results for the Flanker effect (p = 0.77) or the Switch effect (p = 0.63); however, the model was significant for the Stroop effect (R2 = 0.301, F(3, 28) = 4.02, p = 0.017), with the LSBQ composite score demonstrating a positive correlation with the Stroop effect (p = 0.04), suggesting that the higher the composite score, the higher the Stroop effect. In order to explore this further, we ran separate models to investigate the effect of the three switching domains that the LSBQ measures. The models were not significant for switching with friends (p = 0.628) and for switching in social media (p = 0.606), but the effect was significant when switching with family was used as the predictor (R2 = 0.265, F(3, 28) = 3.37, p = 0.033), which positively correlated with the Stroop effect (p = 0.009). This may have driven the significant effect of the composite score.

5. Discussion

Following suggestions that conversational contexts requiring different levels of switching affect executive functions differently (Green and Abutalebi 2013) this study examined whether diglossic participants (who, with minimal opportunities for code-switching between their two language varieties, correspond to Green & Abutalebi’s SLC) perform similarly to monolinguals. We compared the performance of Arabic speaking young adults to English speaking monolinguals of a similar age on three tasks, Flanker, Stroop and Color-Shape, which tap the executive function domains of inhibition and switching (Miyake et al. 2000). In each task we compared performance between cognitively challenging and control conditions, namely between Congruent and Incongruent trials for the Flanker and Stroop tasks, and between Stay and Change trials for the Color-shape task. While all of our tasks yielded the expected pattern (i.e., lower accuracy and slower RTs for the more cognitively challenging conditions), the difference in performance across task levels did not differ between our diglossic and monolingual groups in any of the tasks. Specifically, our results did not reveal smaller cognitive costs for diglossics compared to monolinguals, a pattern that has been typically interpreted as a benefit for bilingual groups when compared to monolinguals (Valian 2015); in other words, our results suggest no diglossic benefits in any task. These findings will be discussed with reference to previous studies and theoretical proposals for the effect of using two languages on cognition.

It is worth noting that the monolingual group had shorter overall RTs than the diglossic group across all tasks (all ps < 0.001), while no such pattern was observed with respect to overall accuracy. While a bilingual benefits in global RTs have been often linked to the high monitoring skills of bilinguals compared to monolinguals (Hilchey and Klein 2011), our study fails to replicate these effects in a diglossic population; rather, our findings point toward a global disadvantage for the diglossic group. It is important to note that bilingual advantages in overall reaction times have not been replicated in all studies (Antón et al. 2019; Kirk et al. 2014). In order to explain this discrepancy, some have rejected bilingualism as a factor leading to faster overall RTs, and attributed such effects to unmatched external factors such as socioeconomic status (Antón et al. 2019). Since monolinguals in our study demonstrated faster RTs than diglossics, we cannot readily attribute this seeming diglossic “disadvantage” to the two groups’ language experiences; indeed, we had no grounds to predict it, nor has it been reported previously. As suggested by Antón et al. (2019), this finding might be related to external factors which warrant further investigation. One candidate is task familiarity; our monolingual group were psychology students recruited for course credit who may have been familiar with the classic cognitive tasks we employed. In contrast, our diglossics were not recruited from a psychology department. Prior training has been shown to result in better performance in inhibition, switching and updating tasks (Chevalier et al. 2012; Hughes et al. 2009; Salminen et al. 2012) and to increased processing speed (Dux et al. 2009), and this suggestion might explain our overall RTs patterns. Another possible explanation could be that, while both groups still lie within the grey area of young adults as defined by bilingual studies (Donnelly et al. 2019), diglossics were slightly but significantly older than monolinguals, and it has been suggested that processing speed and reaction times decline with age (Ferreira et al. 2015). Nevertheless, the inclusion of age as a covariate in our models may this explanation less likely as a candidate.

An unexpected finding in our study was the positive correlation between the Stroop effect and measures of diglossic experience, namely the LSBQ composite score and the “switching with family” subscale of the same test. If anything, we would expect the opposite pattern, that is, the more experience the participants have in switching between languages, the easier it would be to process the incongruent trials, i.e., the smaller the Stroop effect would be. However, this prediction is usually drawn from findings from bilinguals not necessarily in SLCs, so it may not entirely apply to our diglossic environment and the particularities it encompasses. Taken at face value, this pattern suggests that people who switch in one context only may actually face difficulties in inhibitory control as it is measured by the Stroop task. Nevertheless, such effects that have occasionally be characterised as bilingual disadvantages (but see Luk (2022), for a criticism on this term), have been reported very rarely in the literature, and have been attributed to Type I errors (De Bruin et al. 2015). Based on this, our relatively small sample size, and the fact that such an effect was not observed for the related Flanker effect, we treat this finding with caution.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that reports no benefits in executive functions across the board in diglossics. Our findings contradict recent evidence suggesting some benefits in inhibition in older diglossics from the same linguistic environment (Alrwaita et al. n.d.), lending support to the peak performance hypothesis (Bialystok et al. 2005). However, our findings also contradict those from previous studies conducted in Cyprus by Antoniou et al. (2016), who found diglossic benefits in children (Antoniou et al. 2016) and young adults (Antoniou and Spanoudis 2020). The contradiction between our and those findings might be explained in light of the amount of switching required by our diglossic group. In Arabic the standard dialect and regional varieties are clearly separated by context, and orally switching between the two varieties is very unlikely (Albirini 2016). In this respect Arabic is a good example of an SLC as described by the Adaptive Control Hypothesis (Green and Abutalebi 2013), where each language/dialect is used in a specific context and switching between them rarely occurs. This contrasts with the diglossic situation in Cyprus, where switching between the two varieties occurs frequently (Pavlou 2004), as the two varieties are not restricted to a specific context (Rowe and Grohmann 2013). Therefore, we suggest that the diglossic benefits found in those previous studies (Antoniou et al. 2016; Antoniou and Spanoudis 2020) are due to the diglossic situation in Cyprus allowing for switching between the two varieties. Importantly, our results are in line with Scaltritti et al. (2017) who reported no bidialectal benefits in executive functions amongst young adults. This pattern of findings across studies calls for careful attention to the context in which each language is used in each environment, irrespective of whether the case in hand is diglossia, bidialectalism and bilingualism. As discussed previously, the type and amount of code-switching cannot be assumed to be constant in each of these situations. Together, these findings suggest that it is overly simplistic to label a diglossic environment as an SLC, or a bilingual environment as a Dual Language Context, based on narrow linguistic criteria. Strong predictions about the effects of multiple language use on cognition should not be drawn based on these crude categories alone; instead, the everyday linguistic experiences of the user should be central to the formulation of predictions.

This study aimed to investigate the role of context solely as a factor in enhancing EFs. The results of the study, however, suggest that the relationship between language and cognition is a complex one, involving heterogenous populations, sociocultural contexts and individual experiences. One limitation of this study is the lack of consideration for other factors alongside context. For instance, many studies have highlighted the importance of controlling for factors such as the socio-economic status (Engel de Abreu et al. 2012; Morton and Harper 2007), age (Bialystok et al. 2005), education (Luo et al. 2013), age of second language acquisition (Kapa and Colombo 2013; Pelham and Abrams 2014) and cultural background (Samuel et al. 2018). In the case of our study, most of these factors (with the exception of educational level) were not systematically controlled, and they could potentially explain the overall difference in reaction times between our groups, but not necessarily the absence of effects that would suggest a benefit for diglossics. Nevertheless, future studies on diglossic populations should aim to account for such factors by using tools that carefully measure them.

6. Conclusions

Despite the wealth of studies into the effect of speaking two or more languages on executive functions, little research has investigated similar effects of speaking two language varieties. In this study we assessed diglossic and monolingual young adults on the executive function domains of inhibition and switching (Miyake et al. 2000), which have been shown to be affected in older participants from the same linguistic environment (Alrwaita et al. n.d.). Our study found no diglossic benefits in any on these tasks, suggesting that, even if single language contexts are able to confer some effects on aspects of domain general cognition, these may not be observable in younger individuals. We argue that examining the language context, in terms of the amount of code-switching employed, is essential to understanding the relationship between using multiple languages/language varieties and cognition. Further, we argue that no contextual assumptions should be ascribed to all bilingual or diglossic situations. Rather, careful attention should be paid to the specific code- switching requirements of each language environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P. and N.A.; methodology, C.P. and N.A.; validation, C.P., L.M. and N.A.; formal analysis, N.A. and L.M.; investigation, N.A.; resources, C.P.; data curation, N.A. and L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.; writing—review and editing, C.P. and C.H.-P.; visualization, L.M.; supervision, C.P. and C.H.-P.; project administration, N.A.; funding acquisition, N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded Saudi Government Scholarship awarded to N.A. The APC was funded by the University of Reading Open Access Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Reading.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OSF at https://osf.io/z6g2p, accessed on 7 December 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

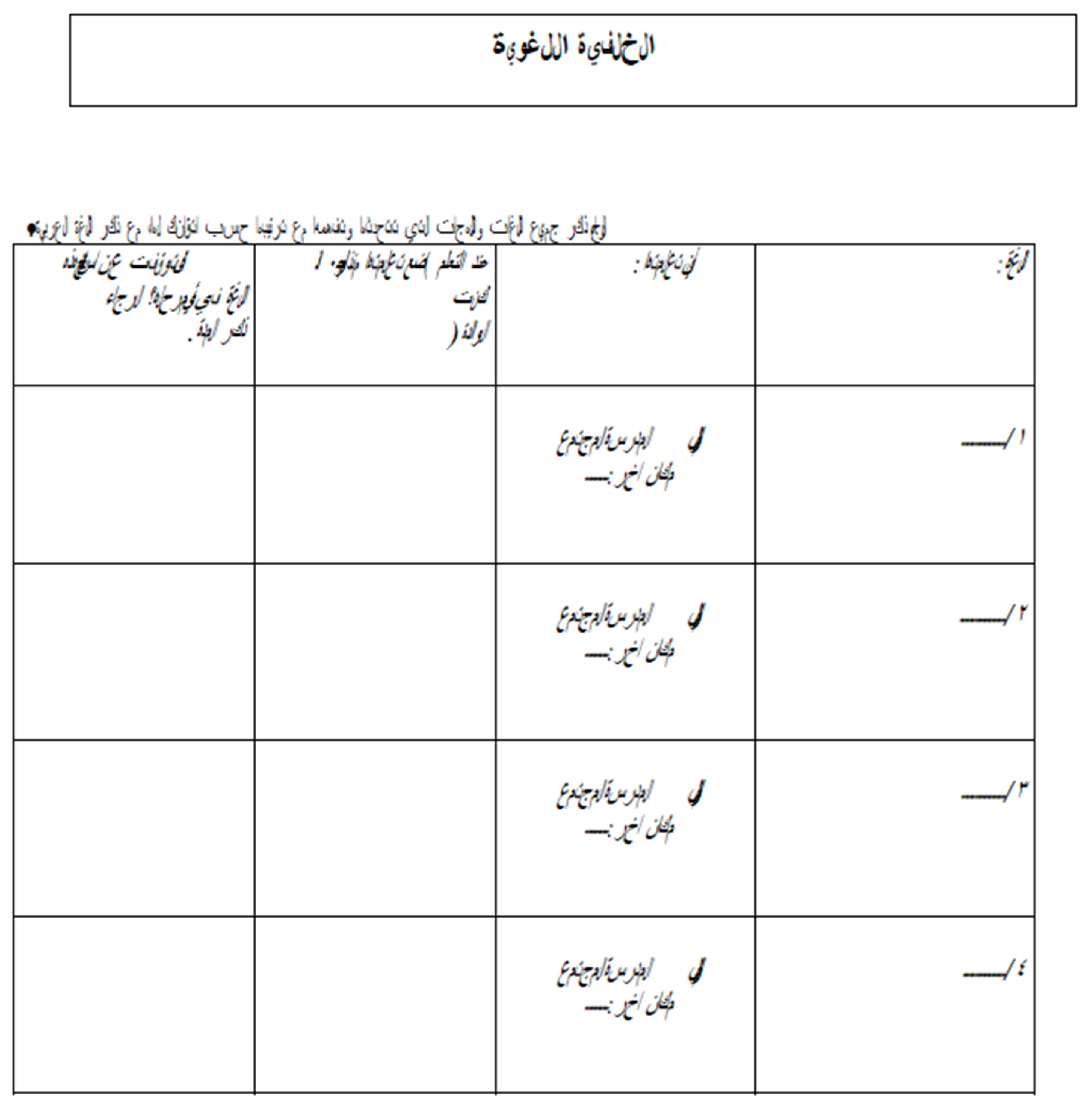

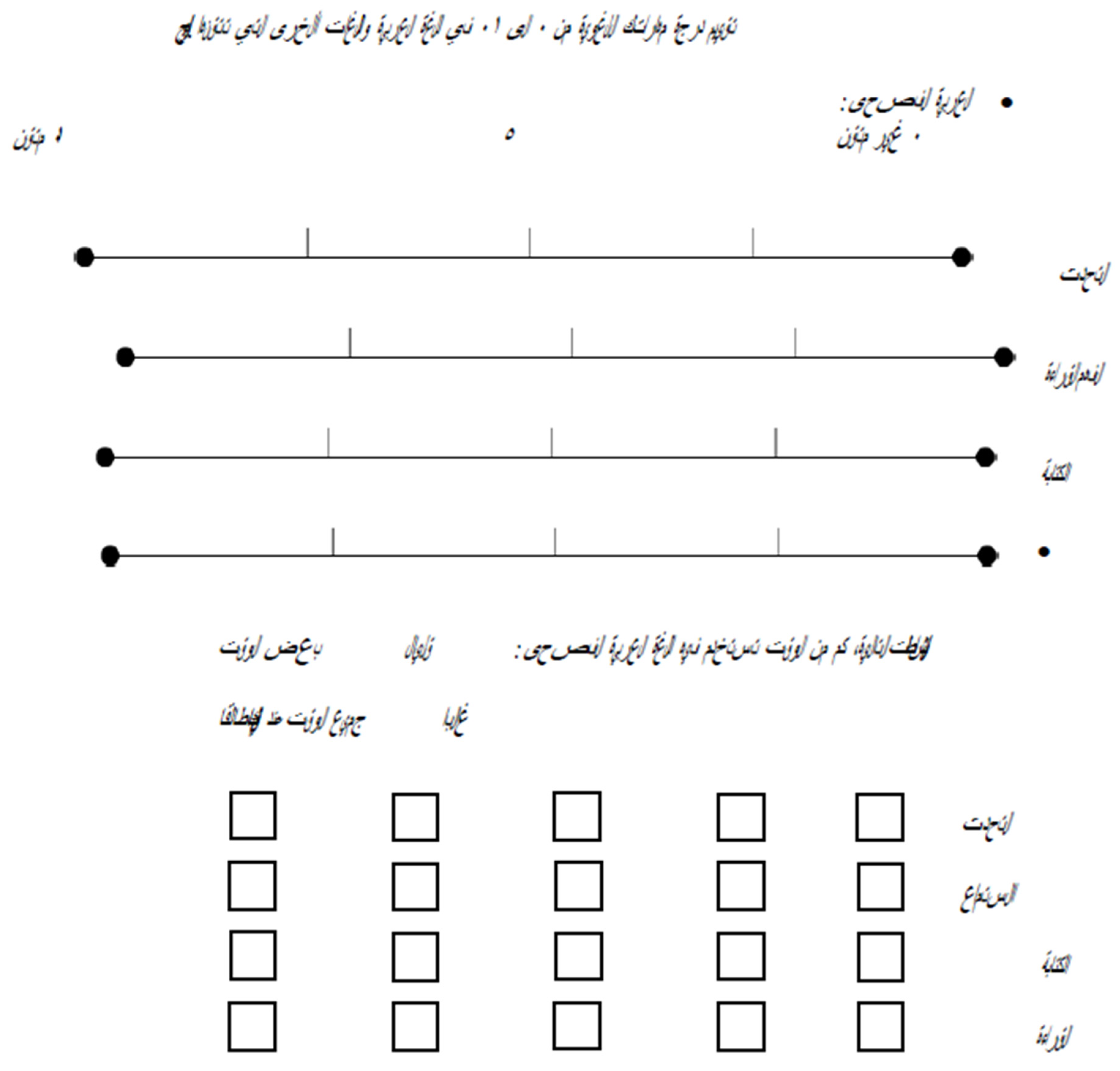

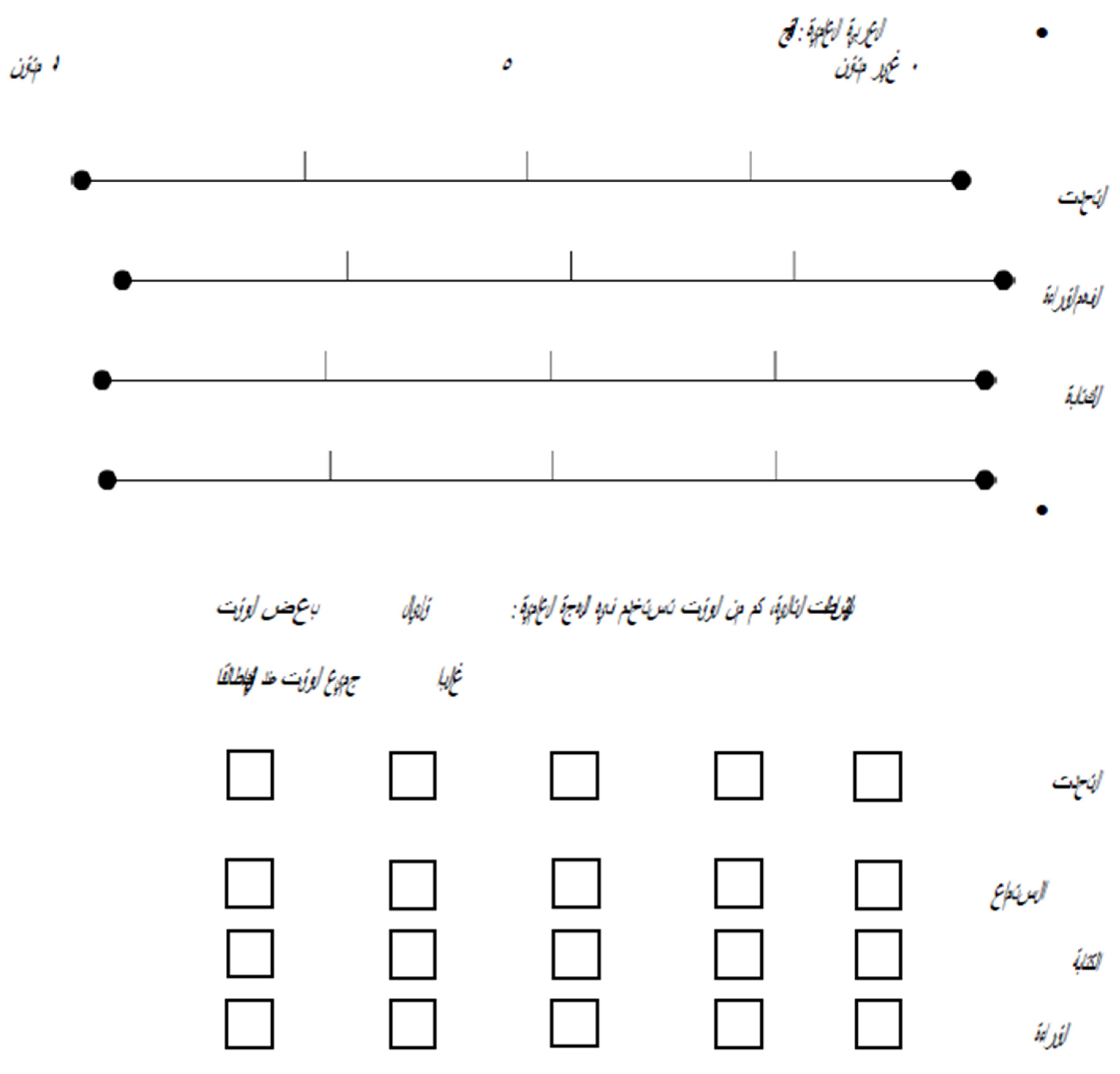

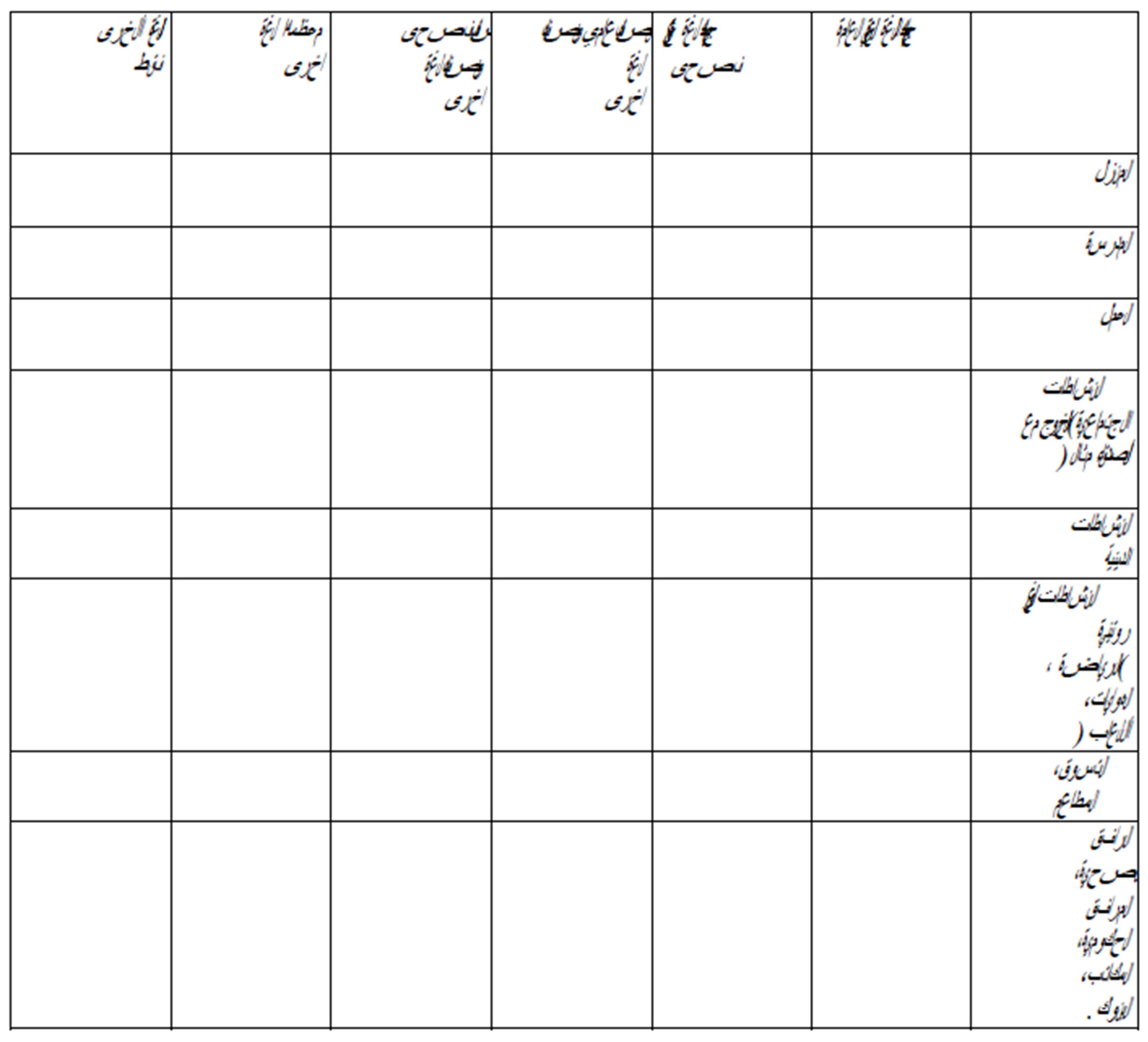

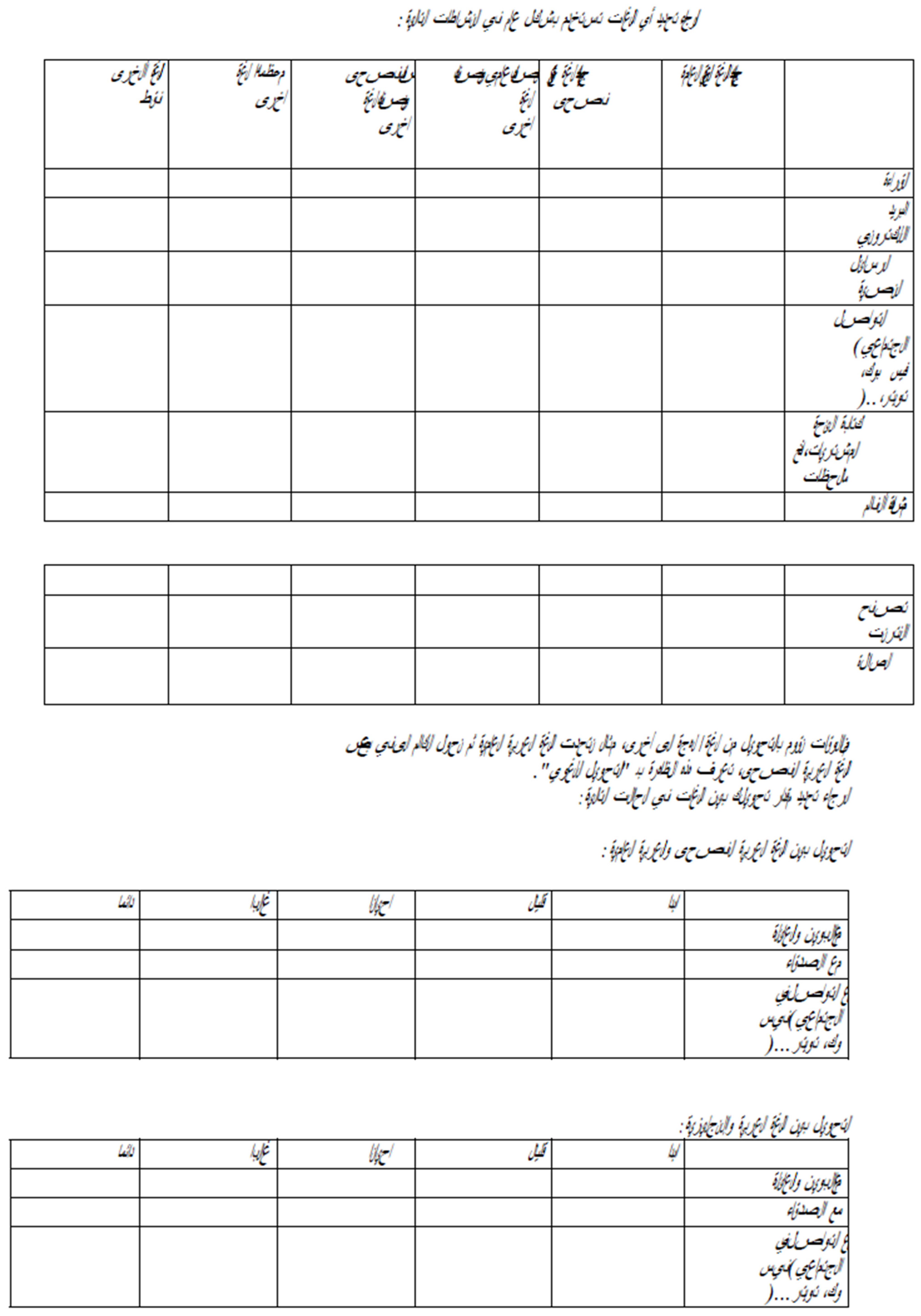

Appendix A. Language and Social Background Questionnaire (Translated to Arabic)

References

- Albirini, Abdulkafi. 2016. Modern Arabic Sociolinguistics: Diglossia, Variation, Codeswitching, Attitudes and Identity. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Alrwaita, Najla, Carmel Houston-Price, and Christos Pliatsikas. 2022. The effects of using two variants of one language on cognition: Evidence from bidialectalism and diglossia. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrwaita, Najla, Lotte Meteyard, Toms Voits, Carmel Houston-Price, and Christos Pliatsikas. n.d. Executive Functions are Modulated by the Context of Dual Language Use: Comparing Diglossic and Bilingual Older Adults. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition.

- Alsahafi, Morad. 2016. Diglossia: An overview of the Arabic situation. International Journal of English Language and Linguistics Research 4: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Amara, Muhammad Hasan, and Abd Al-Rahman Mar’I. 2002. Policy and Teaching Arabic as a Mother Tongue. In Language Education Policy: The Arab Minority in Israel. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, John A. E. Anderson, Lorinda Mak, Aram Keyvani Chahi, and Ellen Bialystok. 2018. The language and social background questionnaire: Assessing degree of bilingualism in a diverse population. Behavior Research Methods 50: 250–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, Eneko, Manuel Carreiras, and Jon Andoni Duñabeitia. 2019. The impact of bilingualism on executive functions and working memory in young adults. PLoS ONE 14: e0206770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, Kyriakos, and George Spanoudis. 2020. An Investigation of the Multilingual and Bi-dialectal Advantage in Executive Control. The Cognitive Science Society 2020 8: 2050–56. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, Kyriakos, Kleanthes Grohmann, Maria Kambanaros, and Napoleon Katsos. 2016. The effect of childhood bilectalism and multilingualism on executive control. Cognition 149: 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, Peter. 2011. Europe’s sociolinguistic unity, or: A typology of European dialect/standard constellations. In Perspectives on Variation. Edited by Nicole Delbecque, Johan van der Auwera and Dirk Geeraerts. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen. 2011. Reshaping the mind: The benefits of bilingualism. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue Canadienne de Psychologie Expérimentale 65: 229–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen, Fergus I. M. Craik, and Gigi Luk. 2012. Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 16: 240–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen, Fergus I. M. Craik, and Jennifer Ryan. 2006. Executive control in a modified antisaccade task: Effects of aging and bilingualism. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 32: 1341–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen, Michelle M. Martin, and Mythili Viswanathan. 2005. Bilingualism across the lifespan: The rise and fall of inhibitory control. International Journal of Bilingualism 9: 103–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudelaa, Sami, and William D. Marslen-Wilson. 2013. Morphological structure in the Arabic mental lexicon: Parallels between standard and dialectal Arabic. Language and Cognitive Processes 28: 1453–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, Amelia, and Ellen Bialystok. 2014. Independent effects of bilingualism and socioeconomic status on language ability and executive functioning. Cognition 130: 278–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Stephanie M., and Andrew N. Meltzoff. 2008. Bilingual experience and executive functioning in young children. Developmental Science 11: 282–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, Nicolas, Tifanny D. Sheffield, Jennifer MizeNelson, Caron A. C. Clark, Sandra A. Wiebe, and Kimberly Andrews Espy. 2012. Underpinnings of the Costs of Flexibility in Preschool Children: The Roles of Inhibition and Working Memory. Developmental Neuropsychology 37: 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Albert, Mireia Hernández, and Nuria Sebastián-Gallés. 2008. Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: Evidence from the ANT task. Cognition 106: 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Albert, Mireia Hernández, Jordi Costa-Faidella, and Nuria Sebastián-Gallés. 2009. On the bilingual advantage in conflict processing: Now you see it, now you don’t. Cognition 113: 135–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, Angela, Barbara Treccani, and Sergio Della Sala. 2015. Cognitive Advantage in Bilingualism: An Example of Publication Bias? Psychological Science 26: 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, Seamus, Patricia J. Brooks, and Bruce D. Homer. 2019. Is there a bilingual advantage on interference-control tasks? A multiverse meta-analysis of global reaction time and interference cost. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 26: 1122–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dux, Paul E., Michael N. Tombu, Stephenie Harrison, Baxter P. Rogers, Frank Tong, and Rene Marois. 2009. Training Improves Multitasking Performance by Increasing the Speed of Information Processing in Human Prefrontal Cortex. Neuron 63: 127–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmorey, Karen, Gigi Luk, Jennie. E. Pyers, and Ellen Bialystok. 2008. The Source of Enhanced Cognitive Control in Bilinguals. Psychological Science 19: 1201–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel de Abreu, Pascale M. J., Anabela Cruz-Santos, Carlos J. Tourinho, Romain Martin, and Ellen Bialystok. 2012. Bilingualism Enriches the Poor: Enhanced Cognitive Control in Low-Income Minority Children. Psychological Science 23: 1364–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Charles A. 1959. Diglossia. WORD 15: 325–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Daniel, Rat Correia, Antonieta Nieto, Alejandra Machado, Yaiza Molina, and José Barroso1. 2015. Cognitive decline before the age of 50 can be detected with sensitive cognitive measures. Psicothema 27: 216–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangoudaki, Anna. 1992. Diglossia and the present language situation in Greece: A sociological approach to the interpretation of diglossia and some hypotheses on today’s linguistic reality. Language in Society 21: 365–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, Howard. 1973. Accent Mobility: A Model and Some Data. Anthropological Linguistics 15: 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Green, David W., and Jubin Abutalebi. 2013. Language control in bilinguals: The Adaptive Control Hypothesis. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 25: 515–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, Mireia, Clara D. Martin, Francisco Barceló, and Albert Costa. 2013. Where is the bilingual advantage in task-switching? Journal of Memory and Language 69: 257–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilchey, Mathew D., and Raymond M. Klein. 2011. Are there bilingual advantages on nonlinguistic interference tasks? Implications for the plasticity of executive control processes. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 18: 625–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Claire, Rosie Ensor, Anji Wilson, and Andrew Graham. 2009. Tracking executive function Across the Transition to School: A Latent Variable Approach. Developmental Neuropsychology 35: 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapa, Leah L., and John Colombo. 2013. Attentional control in early and later bilingual children. Cognitive Development 28: 233–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, Alan S. 2001. Diglossia: The state of the art. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2001: 117–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Keller, Rudolf E. 1973. Diglossia in German-speaking Switzerland. Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 56: 130–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgarriff, Adam, Frieda Charalabopoulou, Maria Gavrilidou, Janne Bondi Johannessen, Saussan Khalil, Sofie Johansson Kokkinakis, Robert Lew, Serge Sharoff, Ravikiran Vadlapudi, and Elena Volodina. 2014. Corpus-based vocabulary lists for language learners for nine languages. Language Resources and Evaluation 48: 121–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, Neil W., Linda Fiala, Kenneth C. Scott-Brown, and Vera Kempe. 2014. No evidence for reduced Simon cost in elderly bilinguals and bidialectals. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 26: 640–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousaie, Shanna, and Natalie A. Phillips. 2012. Ageing and bilingualism: Absence of a “bilingual advantage” in Stroop interference in a nonimmigrant sample. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 65: 356–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, Judith F., and Ellen Bialystok. 2013. Understanding the consequences of bilingualism for language processing and cognition. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 25: 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, Russel V., Paul Buerkner, Maxime Herve, Jonathon Love, Hannes Riebl, and Henrik Singmann. 2021. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means (Version 1.5.4). Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Luk, Gigi Justice. 2022. Examining the assumptions and framing of researching bilingual (dis)advantage. In Applied Psycholinguistics. Edited by Rachel Hayes-Harb. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Lin, Fergus I. M. Craik, Sylvain Moreno, and Ellen Bialystok. 2013. Bilingualism interacts with domain in a working memory task: Evidence from aging. Psychology and Aging 28: 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, Viorica, and Michael Spivey. 2003. Competing activation in bilingual language processing: Within- and between-language competition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 6: 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrai, Ahmed, and James Milton. 2019. How many words do you need to speak Arabic? An Arabic vocabulary size test. The Language Learning Journal 47: 519–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, Akira, Naomi P. Friedman, Michael J. Emerson, Alexander H. Witzki, Amy Howerter, and Tor D. Wager. 2000. The Unity and Diversity of executive functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cognitive Psychology 41: 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J. Bruce, and Sarah N. Harper. 2007. What did Simon say? Revisiting the bilingual advantage. Developmental Science 10: 719–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paap, Kenneth R., and Zachary I. Greenberg. 2013. There is no coherent evidence for a bilingual advantage in executive processing. Cognitive Psychology 66: 232–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paap, Kenneth R., Hunter A. Johnson, and Oliver Sawi. 2015. Bilingual advantages in executive functioning either do not exist or are restricted to very specific and undetermined circumstances. Cortex 69: 265–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, Jeremy. 2008. Arabic Diglossia: Student Perception of spoken Arabic after living in the Arabic-speaking world. Journal of Second Language Acquisition and Teaching 15: 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Papapavlou, Andreas N., and Pavlos Pavlou. 1998. A Review of the Sociolinguistic Aspects of the Greek Cypriot Dialect. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 19: 212–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, Pavlos. 2004. Greek dialect use in the mass media in Cyprus. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2004: 101–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelham, Sabra D., and Lise Abrams. 2014. Cognitive advantages and disadvantages in early and late bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 40: 313–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poarch, Gregory J., Jan Vanhove, and Raphael Berthele. 2019. The effect of bidialectalism on executive function. International Journal of Bilingualism 23: 612–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenhouse, Judith, and Mira Goral. 2006. Bilingualism in the Middle East and North Africa: A Focus on the Arabic-Speaking World. In The Handbook of Bilingualism. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 835–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Josephine, and Alissa Melinger. 2017. Bilingual advantage, bidialectal advantage or neither? Comparing performance across three tests of executive function in middle childhood. Developmental Science 20: e12405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, Charley, and Kleanthes K. Grohmann. 2013. Discrete bilectalism: Towards co-overt prestige and diglossic shift in Cyprus. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2013: 119–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S’hiri, Sonia. 2002. Speak Arabic Please!: Tunisian Arabic Speakers’ Linguistic Accommodation to Middle Easterners. In Language Contact and Language Conflict in Arabic. Milton Park: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Salminen, Tiina, Tilo Strobach, and Torsten Schubert. 2012. On the impacts of working memory training on executive functioning. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 6: 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, Steven, Karen Roehr-Brackin, Hyensou Pak, and Hyunji Kim. 2018. Cultural Effects Rather Than a Bilingual Advantage in Cognition: A Review and an Empirical Study. Cognitive Science 42: 2313–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaltritti, Michele, Francesca Peressotti, and Michelle Miozzo. 2017. Bilingual advantage and language switch: What’s the linkage? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20: 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Michael C., Bhadriraju Krishnamurti, Colin P. Masica, and Anjanji K Sinha. 1989. South Asian Languages: Structure, Convergence and Diglossia. Journal of the American Oriental Society 109: 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharoff, Serge. 2006. Open-source Corpora: Using the net to fish for linguistic data. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 11: 435–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soveri, Anna, Matti Laine, Heikki Hämäläinen, and Kenneth Hugdahl. 2011. Bilingual advantage in attentional control: Evidence from the forced-attention dichotic listening paradigm*. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 14: 371–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surrain, Sarah, and Gigi Luk. 2019. Describing bilinguals: A systematic review of labels and descriptions used in the literature between 2005–15. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 22: 401–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffers-Daller, Jeanine, Zehra Ongun, Julia Hofweber, and Michal Korenar. 2020. Explaining Individual Differences in Executive Functions Performance in Multilinguals: The Impact of Code-Switching and Alternating Between Multicultural Identity Styles. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 561088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valian, Virginia. 2015. Bilingualism and cognition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 18: 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Hwajin, Andree Hartanto, and Sujin Yang. 2016. The importance of bilingual experience in assessing bilingual advantages in executive functions. Cortex 75: 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).