Abstract

This article traces the development of voiced prepalatal obstruents // and /ʒ/ in Judeo-Spanish, the language spoken by the Sephardic Jews since before their expulsion from late-15th century Spain. Using Medieval Spanish as a comparative starting point, we examine diachronic innovations in the phonological status and distribution of affricate // and fricative /ʒ/ in Judeo-Spanish during the diaspora, focusing in particular on the effects of lexical borrowing from Turkish and French in territories of the former Ottoman Empire. In contemporary Sephardic communities that are in contact with non-Sephardic varieties of Mainstream Spanish, some speakers occasionally replace syllable-initial /∫/, //, and /ʒ/ in certain Judeo-Spanish words by a voiceless velar /x/ in efforts to accommodate the pronunciation of the corresponding Mainstream Spanish cognate form. We provide a novel analysis of Judeo-Spanish voiced prepalatal obstruents, including their diachronic and synchronic variation under language contact. The analysis combines a constraint-based approach to phonological alternations, as formalized in Optimality Theory, with a usage-based representation of the mental lexicon, as proposed in Exemplar Theory, to account for speaker- and word-specific variability. A hybrid theoretical model provides a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between lexicon and grammar in Judeo-Spanish phonology than is available in previous structuralist descriptions.

1. Introduction

Judeo-Spanish (henceforth, JS) refers to those varieties of Spanish spoken by the Sephardic Jews who were expelled from Spain beginning in 1492 and resettled around the Mediterranean. In this paper, we examine and analyze the phonological patterning of voiced prepalatal obstruents, including their diachronic evolution from Medieval Spanish into Istanbul JS, as well as their synchronic variation in contemporary Sephardic communities that are in contact with non-Sephardic Spanish. Medieval Spanish possessed two voiceless prepalatal obstruents, affricate // and fricative /∫/, but only a single voiced prepalatal obstruent, most likely pronounced as an affricate [] after a pause and certain consonants but as a fricative [ʒ] after a vowel. In the northern peninsula, /∫/ and /~ʒ/ neutralized to /x/ by the end of the 17th century. In contemporary Spanish, /x/ is pronounced as a strident postvelar [χ] in central and northern Spain, while a glottal /h/ is used in southern Spain. In Latin American Spanish, the corresponding phoneme is either a velar /x/ or a glottal /h/, depending on the geographic location or dialectal zone. For simplicity, we abstract away from this variation in non-Sephardic Spanish varieties and refer simply to the /x/ of Mainstream Spanish (henceforth, MS).

The sound changes that produced MS /x/ occurred too late to affect JS in the Sephardic diaspora. Although JS maintained voiceless // and /∫/, language contact with Turkish and French altered the phonological status and distribution of the voiced prepalatals, which underwent a phonemic split to // and /ʒ/ in territories of the former Ottoman Empire (Penny 2000; Quintana Rodríguez 2006; Bunis 2008, 2012; Hualde and Șaul 2011; Hualde 2013). Researchers of late-20th and early-21st century JS varieties in contact with MS have documented the occasional replacement of syllable-initial /∫/, //, and /ʒ/ by /x/ (Nemer 1981; Gilmer 1986; Harris 1994; Donath 1999; Romero 2012, 2013, 2016; Kirschen 2019; Spiegel 2020). According to sociolinguistic studies of the language used by Sephardic communities in Turkey, Mexico, and the United States, accommodation to MS /x/ is variable across individual speakers and lexical items. Although the process appears to involve the substitution of individual phonemes, a more likely scenario is that some speakers borrow entire MS words, some of which happen to have /x/ where the JS cognate word has syllable-initial /∫/, //, or /ʒ/.

This paper shows how the behavior of voiced prepalatal obstruents under language contact provides crucial insights into the relationship between the grammar and the lexicon in JS phonology. We first review comparative data from Medieval Spanish, Istanbul JS, and MS to establish the diachronic evolution of prepalatal obstruents (Section 2.1). We then examine quantitative data from recent sociolinguistic research on JS in Turkey and the United States to show that accommodation to MS /x/ is both variable and lexical in nature (Section 2.2). In Optimality Theory, phonological surface patterns emerge from the interaction of universal but violable constraints. Adopting Katz’s (2016) approach to fortition and continuity lenition, we motivate a constraint-based analysis of the voiced prepalatal alternation in Medieval Spanish (Section 3). To model the effects of lexical borrowing from Turkish and French, we embed the analysis within a core-periphery model of the JS lexicon (Section 4). Loanwords are lexically indexed to a general faithfulness constraint that is separate from faithfulness constraints on words of the native core (Ito and Mester 1999, 2009b; Coetzee 2009; Pater 2007, 2010). A ranking of markedness constraints in between the two types of faithfulness predicts that loanwords will pattern differently from native lexical items. In addition, a usage-based representation of the mental lexicon (Bybee 2001, 2002, 2006; Docherty and Foulkes 2014; Hinskens et al. 2014) is necessary to capture the quantitative variation observed in present-day accommodation to MS /x/. Exemplar Theory (Johnson 1997; Pierrehumbert 2002, 2016; Wedel 2006, 2012; Frisch 2018) allows for individual word tokens to be categorized during language use and for their traces to be stored within continuously updated exemplar clouds that include gradient phonetic detail, abstract phonological information, and social-indexical information. Because they decay over time, traces are stronger for exemplars whose words are categorized by language users more frequently and more recently in previous experience. Stronger traces in turn increase the probability that a given exemplar will be randomly selected as input to the phonological grammar in subsequent speech production. We argue that a hybrid theoretical framework combining exemplars and constraints (van de Weijer 2012, 2014, 2019; Sloos 2013) can model the speaker- and word-specific aspects of variable lexical accommodation in contemporary Sephardic communities (Section 5). Section 6 concludes.

2. Background and Data

JS is known for its retention of linguistic features from Medieval Spanish and other Ibero-Romance languages spoken by the Sephardic Jews in the Iberian Peninsula up through the late-15th century. JS also shows innovative features as a consequence of internal change, koineization processes that operated early in the Sephardic diaspora, and language contact throughout the diaspora. JS varieties were shaped by extensive lexical borrowing, initially from Hebrew and Aramaic and later from Arabic, Turkish, French, and other local languages in the areas of Sephardic resettlement. Despite the current endangered status of JS, there has been a renewed interest in the language over the past fifteen years or so, as well as a growing analytical focus by language researchers. Quintana Rodríguez (2006) documents geographical variation in JS, focusing primarily on the eastern dialects that developed in the Ottoman Empire and its successor states but also including data from Sephardic communities in Israel, as well as from the western dialects that developed in North Africa. Bunis (2008, 2012) compares the linguistic features of Ottoman JS (commonly referred to as judezmo among other names) with the features of Moroccan JS (historically known as haketía) and describes the differential effects of language contact with Turkish and Moroccan Arabic, respectively. Kirschen (2015, 2018) and Schwarzwald (2018) provide comprehensive overviews of the historical and linguistic roots of spoken JS, including its relation to the calque language known as ladino, which served to provide word-for-word translations of Hebrew liturgical texts. Bunis (2013, 2018) traces the development of Ottoman judezmo, including historical contact with Turkish, and gives an overview of structural features, written and oral traditions, and the state of current research on the language. Drawing from both empirical and theoretical studies, Bradley (2022) describes the phonetics and phonology of spoken JS, comparing Ottoman and Moroccan JS varieties.

2.1. Evolution of the Medieval Spanish Voiced Prepalatal Obstruents

Prepalatal obstruents were absent from Latin and came into existence in Medieval Spanish as part of a series of sound changes that created new palatal segments in the Romance languages. Zampaulo (2019) provides a thorough discussion of the chronology of these changes (for Medieval Spanish prepalatal obstruents in particular, see Boyd-Bowman 1980, pp. 10–11, 71–72; Penny 2014, pp. 84–93). In (1) we compare the prepalatal obstruents of Medieval Spanish with their present-day correspondents in the JS of Istanbul, Turkey and in MS, drawing upon data and descriptions from Perahya and Perahya (1998), Penny (2000, p. 180), Hualde and Șaul (2011, p. 99), and Hualde (2013, pp. 250–52). Both Istanbul JS and MS retain Medieval Spanish // (1a), while only Istanbul JS retains /∫/ (1b). In Medieval Spanish, there was most likely a complementary distribution between affricate [], which appeared after a pause (1c) or nasal consonant (1d), and fricative [ʒ], which appeared between vowels, both word-initially (1e) and word-medially (1f). In principle, the Medieval Spanish distribution can be analyzed as either fortition of /ʒ/ → [] (1c,d) or lenition of // → [ʒ] (1e,f), depending on which alternant is taken to be the underlying phoneme. A key difference about Istanbul JS, to be explained in greater detail below, is that [] appears in all word-initial contexts—even after a vowel (1e), unlike in Medieval Spanish—while [ʒ] appears in word-medial intervocalic position (1f) in both Medieval Spanish and Istanbul JS.

| (1) | Medieval Spanish | Istanbul JS | MS | ||

| a. | [íko] | [íko] | [íko] | ‘small’ | |

| [nóe] | [nóe] | [nóe] | ‘night’ | ||

| b. | [∫abón] | [∫avón] | [xaβón] | ‘soap’ | |

| [bá∫o] | [bá∫o] | [báxo] | ‘low’ | ||

| c. | [énte] | [énte] | [xénte] | ‘people’ | |

| d. | [kon énte] | [kon énte] | [koŋ xénte] | ‘with people’ | |

| e. | [la ʒénte] | [la énte] | [la xénte] | ‘the people’ | |

| f. | [óʒo] | [óʒo] | [óxo] | ‘eye’ |

Besides /∫/ and /~ʒ/, Medieval Spanish had two other pairs of sibilant phonemes that were distinguished by voicing: the dentoalveolar affricates // and // and the apicoalveolar fricatives // and //. In the northern peninsula, this sibilant subsystem underwent a phonological reorganization, which was completed by the 17th century (Hualde 2014, pp. 150–54; Penny 2014, pp. 120–23; Baker and Holt 2020, p. 490–91; Núñez-Méndez 2021, pp. 29–31, 35–36, 49). Traditionally, the reorganization is described in terms of three main changes that took place in the following order:

- Deaffrication of the dentoalveolar affricates to dentoalveolar fricatives // and //;

- Devoicing of the voiced obstruents //, //, and /~ʒ/ and subsequent merger with their voiceless counterparts //, //, and /∫/;

- Dissimilation in place of articulation, whereby dentoalveolar // shifted forward to interdental /θ/ and prepalatal /∫/ shifted backward to velar /x/.

After these changes, apicoalveolar // remained as the only coronal sibilant in the northern peninsula. Based on an acoustic and a perceptual study of the sibilants of contemporary Eastern Catalan, which resembles that of Medieval Spanish before the above reorganization took place, Rost Bagudanch (2022) finds strong experimental support for the internal phonetic basis of sibilant devoicing in Early Modern Spanish, which “may be accounted for in terms of acoustic and aerodynamic factors, as well as in terms of misperception, like most regular sound changes” (p. 23).1 Furthermore, MacKenzie (2022) questions the traditional assumption that sibilant devoicing occurred before the emergence of interdental /θ/. Based on a quantitative analysis of corpus data tracking the change from orthographic <d> to <z> in word-medial preconsonantal contexts, e.g., juzgar for iudgar ‘to judge’ (< Latin iudicare), he proposes that dentoalveolar // and // underwent dissibilation to non-sibilant /ð/ and /θ/, respectively, by the 16th century—before the devoicing process was completed (see also Menéndez Pidal 1987, p. 13). Though MacKenzie’s revised model of the genesis of /θ/ does not explicitly address the emergence of /x/, Núñez-Méndez’s (2021, pp. 31, 35–36, 49) meticulous overview of research on Spanish sibilant evolution makes clear that, around the end of the 16th century, /∫/ and /~ʒ/ were in fluctuation with voiceless velar /x/, which later became general by the middle of the 17th century. This is the historical source of /x/ in present-day MS (1b–f).

Although // and // had already deaffricated to // and // by the time of the late-15th century expulsion, JS sibilants in the Sephardic diaspora were unaffected by the dissibilation, devoicing, and velarization changes that would occur over the following two centuries, giving rise to the fricatives of contemporary MS. In addition to the syllable-initial contexts in (1b), two syllable-final contexts supported the emergence of /∫/ (Penny 2000, p. 180; Bunis 2012, pp. 680, 687–88). Some Medieval Spanish words had /∫/ before voiceless velar /k/, e.g., mo[∫]ka ‘fly’ (cf. MS mosca), an archaic feature retained in Ottoman JS and, to a lesser extent, Moroccan JS. Word-final /∫/ also developed as an innovation in Ottoman JS from the coalescence of /j/, in the numeral se[∫] ‘six’ and in second person plural verb forms, e.g., entende[∫] ‘you (plural) understand’ (cf. MS seis, entendéis).

In Ottoman varieties of JS, the voiced prepalatal obstruent allophones of Medieval Spanish split into separate phonemes // and /ʒ/ as consequence of extensive lexical borrowing from Turkish and French. While // exists as a phoneme in Turkish, /ʒ/ is absent from the native Turkish lexicon and appears only in loanwords from French (Comrie 1997, p. 885). French has phonemic /ʒ/ but lacks //, except for Germanisms in some Swiss varieties (Côté 2022, p. 678–79). Varol Bornes (2008, pp. 340–76) provides the most extensive documentation of lexical borrowing from Turkish and French in the JS of Istanbul. We adapt her orthographic examples to modern IPA transcription below. In Turkish loanwords, // can appear word-initially after a pause (2a) and word-medially, after a nasal (2b) or rhotic (2c) consonant—segmental contexts that would have favored [] also in Medieval Spanish (1c,d). Between vowels, [] appears in Turkish loanwords (2d), but only fricative [ʒ] appears in Medieval Spanish (1f).

| (2) | a. | [ádːe] | ‘avenue’ | < cadde |

| [ám] | ‘glass’ | < cam | ||

| [amí] | ‘mosque’ | < cami | ||

| [ámlɯk] | ‘glass cabinet’ | < camlık | ||

| [ánɯm] | ‘darling’ | < canım | ||

| [eá] | ‘penalty’ | < ceza | ||

| [ýbːe] | ‘cassock’ | < cübbe | ||

| [umxuɾijét] | ‘the Republic’ | < cumhuriyet | ||

| b. | [enidáɾ] | ‘to cause pain’ | < acıtmak | |

| [amɯ́] | ‘glassmaker’ | < camcı | ||

| [finán] | ‘teacup’ | < fincan | ||

| [i∫kéne] | ‘torture’ | < işkence | ||

| [kanunɯ́] | ‘zither player’ | < kanuncı | ||

| [kujumí] | ‘jeweler’ | < kuyumcu | ||

| [jilánik] | ‘erysipelas’ | < yılancık | ||

| c. | [bulduɾumíko] | ‘quail’ | < bıldırcın | |

| [ɡýɾy] | ‘Georgian’ | < Gürcü | ||

| d. | [aém] | ‘Persian’ | < Acem | |

| [aɯdeáɾe] | ‘to pity’ | < acımak | ||

| [xoá] | ‘Muslim priest’ | < hoca | ||

| [iabɯndá] | ‘if necessary’ | < icabında | ||

| [i∫kembeí] | ‘tripe vender’ | < işkembeci | ||

| [kaveí] | ‘coffee shop owner’ | < kahveci | ||

| [kapɯɯ́] | ‘concierge’ | < kapıcı | ||

| [kaɾaá axmét] | (Turkish cemetery) | < Karaca Ahmet | ||

| [koá] | ‘huge’ | < koca | ||

| [kokoamán] | ‘giant’ | < koskocaman | ||

| [kyfeí] | ‘bellhop’ | < küfeci | ||

| [kunduɾjaɯ́] | ‘shoemaker’ | < kunduracı | ||

| [mejxaneí] | ‘barkeeper’ | < meyhaneci | ||

| [tajaɾeí] | ‘aviator’ | < tayareci | ||

| [tulumbaɯ́] | ‘firefighter’ | < tulumbacı | ||

| [jumuɾtaɯ́] | ‘egg vender’ | < yumurtacı |

In French loanwords, /ʒ/ can appear in word-initial contexts after a pause (3a) and in word-medial intervocalic contexts, after an oral or nasal vowel (3b) or rhotic consonant (3c), as well as in word-final position (3d). The fricative [ʒ] in (3a) diverges from the expected allophonic realization of postpausal /ʒ/ as [] in Medieval Spanish (1c).

| (3) | a. | [ʒeneʁál] | ‘general’ | < général |

| [ʒimnatík] | ‘exercise’ | < gymnastique | ||

| [ʒanvijé], [ʒɑ̃vjé] | ‘January’ | < janvier | ||

| [ʒœ́n] | ‘young’ | < jeune | ||

| [ʒœnɛ́] | ‘youth’ | < jeunesse | ||

| [ʒúʁ] | ‘day’ | < jour | ||

| [ʒuʁnalíto], [ʒuʁnaléɾo] | ‘journalist’ | < journaliste | ||

| [ʒuʁnéa], [ʒuʁné] | ‘day’ | < journée | ||

| [ʒɥɛ̃] | ‘June’ | < juin | ||

| b. | [biʒuteʁí], [biʒuteʁíja] | ‘jewelry shop’ | < bijouterie | |

| [bɔ̃ʒúʁ] | ‘hello’ | < bonjour | ||

| [deʒœné] | ‘lunch’ | < déjeuner | ||

| [demɑ̃ʒɛɔ̃́] | ‘itching’ | < démangeaison | ||

| [deʁɑ̃ʒé] | ‘to cause trouble’ | < déranger | ||

| [diʁiʒáva] | ‘s/he directed’ | < diriger | ||

| [evɑ̃ʒíl] | ‘Gospel’ | < Évangile | ||

| [ɛɡiʒeó] | ‘s/he demanded’ | < exiger | ||

| [fʁiʒidɛ́ʁ] | ‘refrigerator’ | < frigidaire | ||

| [maʒí] | ‘magic’ | < magie | ||

| [pʁɔteʒáɾ] | ‘to protect, adopt’ | < protéger | ||

| [piʒamá] | ‘pajamas’ | < pyjama | ||

| [ʁəliʒjǿ], [ʁeliʒjóo] | ‘religious’ | < religieuse, religieux | ||

| [yʒé] | ‘subject’ | < sujet | ||

| [tuʒúʁ] | ‘always’ | < toujours | ||

| c. | [eɡɔʁʒeáɾ] | ‘to cut the throat’ | < égorger | |

| d. | [∫ofáʒ] | ‘heating’ | < chauffage | |

| [etáʒ] | ‘floor’ | < étage | ||

| [ɡáʒ] | ‘pledge, deposit’ | < gage | ||

| [eʁitáʒ] | ‘heritage’ | < héritage | ||

| [pʁɛtíʒ] | ‘prestige’ | < prestige | ||

| [ʁaváʒ] | ‘ravage’ | < ravage | ||

| [ʁiváʒ] | ‘shore, coastline’ | < rivage | ||

| [vjɛ́ʁʒ] | ‘virgin’ | < vierge | ||

| [viláʒ] | ‘village’ | < village |

Loanwords in both data sets commonly maintain segments from each donor language which are not part of the phonemic inventory that Istanbul JS inherited from Medieval Spanish. Most of these are vocalic segments, i.e., the closed back unrounded /ɯ/ from Turkish, the closed front rounded /y/ from Turkish and French, and the following from French: the voiced labial-palatal approximant /ɥ/, nasal open back unrounded /ɑ̃/, nasal open-mid front unrounded /ɛ̃/, open-mid front unrounded /ɛ/, open-mid front rounded /œ/, mid central /ə/, close-mid front unrounded /ø/, and open-mid back unrounded /ɔ/.2 As for novel consonants, some of the loanwords in (2) contain the voiceless velar fricative /x/ as an adaptation of Turkish glottal /h/, e.g., [umxuɾijét] (2a), [xoá], [kaɾaá axmét], and [mejxaneí] (2d). Turkish /h/ may also be deleted, especially in word-medial position, e.g., [kaveí] (2d). Hualde and Șaul (2011) note that “[t]raditionally, a feature of a ‘Jewish accent’ in Turkish was a strong, velar pronunciation of the aspirated /h/ of the Turkish language” (p. 100). An acoustic analysis of recordings of a male native JS speaker from Istanbul leads Hualde and Șaul to report variability in the amount of frication and the place of articulation of /x/, “although a velar articulation seems to be most common” (p. 100). Turkish loanwords may also include JS suffixes and clitic pronouns, e.g., [enidáɾ] (2b), [bulduɾumíko] (2c), and [aɯdeáɾe] (2d). For a detailed corpus investigation of the integration of Turkish and French loanwords into the morphosyntactic system of Istanbul JS, see Peck (2019). While absent from the JS phonemic inventory, the voiced uvular fricative /ʁ/ is maintained as a rhotic consonant in many of the French loanwords in (3). Some examples have both /ʁ/, contained within the French nominal or verbal form, and the native apicoalveolar tap /ɾ/, contained within a JS agentive or infinitival suffix, e.g., [ʒuʁnaléɾo] (3a), [pʁɔteʒáɾ] (3b), and [eɡɔʁʒeáɾ] (3c).

In a small handful of words such as (4), JS speakers of Catalan and Aragonese origin living in Thessaloniki, Greece maintained the intervocalic voiced dentoalveolar affricate //, which was deaffricated in other Sephardic Spanish varieties, including Istanbul JS. Quintana Rodríguez (2006, pp. 73–74) argues that this archaic // co-existed with innovative prepalatal variants in such words until // ultimately won out by the 17th century, later spreading to Istanbul JS in the 20th century:

| (4) | [dóe] > [dóe] | ‘twelve’ | [póo] > [póo] | ‘water well’ | ||

| [tɾée] > [tɾée] | ‘thirteen’ | [téo] > [téo] | ‘firm, rigid’ |

Hualde and Șaul (2011, p. 99) refer to examples like these as native words. We argue that such forms most likely have a special status in Istanbul JS, either as loanwords borrowed from Catalan and Aragonese, or by virtue of belonging to the class of numerals, which are known to show exceptional behavior in contemporary Catalan and some varieties of MS (for further details, see Quintana Rodríguez 2006, p. 74). Ariza (1994, p. 214) considers [póo] and [téd͡zo] to be Italianisms.

Once loanwords are taken into account, it becomes impossible to predict the surface distribution of voiced prepalatal obstruents by phonological context alone, as [] and [ʒ] now appear in both word-initial postpausal and word-medial intervocalic contexts within a considerable number of lexical items. A natural conclusion is that two allophones of a single voiced prepalatal phoneme in the Medieval language became phonologized in Istanbul JS (Penny 2000, p. 180; Bunis 2008, p. 192, 2012, pp. 680–81; Hualde and Șaul 2011, p. 99; Romero 2012, p. 143, 2013, p. 282).3 Hualde (2013, pp. 250–55) argues that once the two allophones were recategorized as distinct phonemes, the word-initial alternation between [] (1c) and [ʒ] (1e) disappeared from the native lexicon:

| (5) | Medieval Spanish | Istanbul JS | |||

| a. | [énte] | = | [énte] | ‘people’ | |

| b. | [la ʒénte] | > | [la énte] | ‘the people’ |

Further evidence that an older alternation between [] and [ʒ] was lost in word-initial position comes from words that take the prefix /a–/:4

| (6) | [auntáɾ] | ‘to add, join’ | cf. | [únto] | ‘together’ | |

| [autáɾ] | ‘to adjust’ | [úto] | ‘just’ |

For Medieval Spanish, Hualde assumes an underlying affricate // and posits a lenition process that targeted intervocalic voiced obstruents in an across-the-board fashion, regardless of word or morphological boundaries. Such an analysis agrees with the Neogrammarian hypothesis of regular sound change, which predicts that in the initial stages, obstruent lenition would have been conditioned by strictly phonetic factors, such as the intervocalic context, and not by morphological information, such as the presence of word or prefix boundaries (see Hualde 2013, pp. 232–40 for discussion). According to Hualde (2013, pp. 250–55, 260), the eventual loss of the word-initial alternation was a direct consequence of the phonemic split between // and /ʒ/ that was triggered by the influx of Turkish and French loanwords with the two obstruents in the ‘wrong’ position. The end result in Istanbul JS is a reduction in the number of surface allomorphs of native words beginning with a voiced prepalatal obstruent, which is now uniformly non-alternating //. This leaves /ʒ/ restricted to word-medial intervocalic position (1f).

2.2. Accommodation to MS /x/ in Contemporary Sephardic Communities

Fieldwork studies carried out in late-20th century Sephardic communities document lexical borrowings from non-Sephardic MS into JS. Many such borrowings involve the apparent substitution of syllable-initial prepalatal /∫/, //, or /ʒ/ by the velar /x/ of MS. In a linguistic study of the Sephardim living in Indianapolis, Indiana, Nemer (1981, p. 214) describes a JS speaker who had supervised Puerto Rican Spanish speakers at work in Chicago for several years during the 1970s and who would often substitute /x/ in place of // or /ʒ/ in certain words when speaking JS, e.g., [óxo] instead of [óʒu] ‘eye’ as pronounced in his native Monastir dialect.5 Nemer views such substitutions “as not so much a choice, for instance, of [x] over [ʒ] and [], as a choice of forms with [x] over corresponding forms with [ʒ] and []” (p. 214). Gilmer (1986, pp. 54–55) uses the term lexical instability to characterize the occasional use of variants by JS speakers in Izmir, e.g., [íxa] instead of [íʒa] ‘daughter’. Harris (1994, pp. 173–75) observes the widespread replacement of /∫/, //, or /ʒ/ by /x/ in the JS of New York and Los Angeles. Finally, Donath (1999, pp. 72, 78–79) documents replacement by JS speakers residing in Mexico City, e.g., [aúxa], [afloxáɾe], [axuɣáɾ] instead of [aɣúʒa] ‘needles’, [aflo∫áɾe] ‘to loosen’, [a∫uɣáɾ] ‘bridal dress’.

Empirical studies of early-21st century JS provide additional data on accommodation to MS /x/. On the basis of sociolinguistic interviews and translation tasks conducted in the late 2000s, Romero (2012, pp. 101–2) observes the variable substitution of /x/ in place of /∫/, //, and /ʒ/ by many speakers in Istanbul and the Prince Islands, which are part of the Istanbul Metropolitan Area. Romero (2013, pp. 288–91) argues that accommodation to MS /x/ is best understood as lexically driven borrowing instead of phonological restructuring. This argument rests upon two observations. First, accommodation shows inter- and intra-speaker variation and does not affect all native lexical items equally, some words not at all. Only 19 of Romero’s 45 informants replace syllable-initial // and /ʒ/ with /x/. The following transcriptions, which combine standard Romanized orthography and IPA symbols, show that one speaker varies in the pronunciation of i[ʒ]as ~ i[x]as (7a), while another substitutes [x] in []udio and mu[ʒ]er but not refu[ʒ]ados (7b). A third speaker appears to replace every instance of [ʒ] with [x] in vie[ʒ]as, i[ʒ]os, i[ʒ]a, and i[ʒ]o (7c) (Romero 2013, pp. 279, 286):

| (7) | a. | Dospués parí dos i[ʒ]as, dos i[x]as parí. (female, age 82) ‘Afterwards, I gave birth to two daughters, two daughters I gave birth to.’ |

| b. | Mozotros akí todos, todo el [x]udío de Estanbol de la Turkía también avlan el espanyol ke mozotros semos refu[ʒ]ados de la Espanya i avlamos la lingua… el Ladino. Yo, kon mi mu[x]er. Kon mi mu[x]er, kon personas… la edad mía porke la manseves no save. (male, age 75) ‘All of us here, all the Jews of Istanbul, Turkey, also speak Spanish because we are refugees from Spain and we speak the language… Ladino. I, with my wife. With my wife, with people… my age because the youth don’t know how.’ | |

| c. | Aka el tiempo avía Balát. Yo so nasida de Balát, pero aora moz izimos vie[x]as i vini akí. Aora estó muy repozada akí. Ya tengo i[x]os. Una i[x]a i un i[x]o tengo. (female, age 77) ‘In the past there was Balat. I was born in Balat, but now we have gotten older and I came here. Now I am very settled here. I already have two children. I have a daughter and a son.’ |

Table 1 lists the words of Hispanic origin in Romero’s fieldwork corpus in which prepalatals are most frequently replaced with /x/. Eight lexical items account for almost 84% of all instances of accommodation. In some native words, prepalatals are never replaced, e.g., [káʒi] ‘almost’, [kíʒe] ‘I wanted’, [mó∫ka] ‘fly’ (cf. MS casi, quise, mosca).6

Table 1.

Native words most frequently accommodated with /x/ in the JS of Istanbul and the Prince Islands (adapted from Romero 2013, p. 288).

The second observation that motivates lexical borrowing is that Romero’s participants never replace // or /ʒ/ with /x/ in Turkish or French loanwords, such as those in (2) and (3). As Romero (2013, pp. 282–83) points out, the voiceless prepalatal /∫/ also appears in borrowings from Hebrew (e.g., [rá∫] ‘earthquake’, [la∫ón] ‘language, sermon’), Turkish (e.g., [pa∫á] ‘dear’), and French (e.g., [∫áns] ‘luck, chance’) but is never replaced by /x/ in such loanwords. If accommodation involved merely substituting one phoneme with another, then we might expect /x/ to appear more frequently and systematically in the speech of these Sephardic communities than it actually does. We concur with Romero that lexical borrowing provides a better explanation of the variable and restricted nature of accommodation to MS /x/ and is also consistent with previous accounts in the literature that describe language contact between JS and MS.

Extending the empirical comparison, Romero (2016) includes additional data from sociolinguistic interviews carried out in 2013 within the Sephardic community of New York City. As in Istanbul and the Prince Islands, the same words tend to show accommodation to MS /x/ most often, especially by generations of speakers aged 60 and younger. To the items already listed in Table 1, Romero’s later study adds the following examples of accommodation to MS /x/ in JS words containing /∫/ (8a), // (8b), and /ʒ/ (8c):

| (8) | a. | [de∫áɾ] | ‘to leave’ |

| [dí∫o] / [dí∫e] | ‘s/he said’ / ‘I said’ | ||

| [lé∫o] | ‘far’ | ||

| [mi∫óɾ] | ‘better’ | ||

| [pá∫aɾo] | ‘bird’ | ||

| b. | [énte] | ‘people’ | |

| [etɾanéɾo] | ‘foreign’ | ||

| c. | [vjaʒáɾ] | ‘to travel’ |

Even though the process appears to substitute phonemes, accommodation to MS /x/ is actually part of a more general borrowing strategy that involves the replacement of one word by another that shares the same meaning. Romero (2016, p. 393) reports that MS loanwords carro ‘car’, caliente ‘hot’, joven ‘young man’, and comprar ‘to buy’ are used at higher frequencies in New York City, while MS trabajo ‘job’ is used more frequently in Istanbul (cf. JS arabá/otó/otomovíl/vuatur ‘car’, kayente/kaénte ‘hot’, mansevo ‘young man’, merkar ‘to buy’, lavoro/echo ‘job’). The higher prevalence of lexical accommodation in New York City is attributed to the greater degree of language contact between the Sephardim and local speakers of Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Mexican varieties of MS.

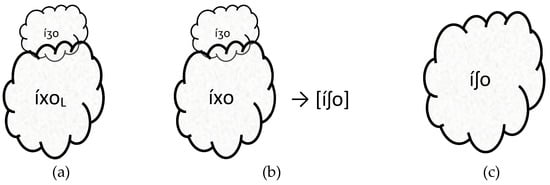

Kirschen’s (2019) study of Sephardic communities in South Florida provides more evidence of JS lexical variation within the United States. He argues in favor of classifying all speakers of contemporary JS as heritage speakers of the language, situated along a range of different proficiency levels (p. 75). Using the Leipzig-Jakarta word list (Haspelmath and Tadmor 2009) as an elicitation task with 20 JS-speaking participants in Miami-Dade, Palm Beach, and Broward Counties, Kirschen found phonological variation in vowels, consonants, and stress placement. Most importantly for our purposes, he carried out spectrographic analyses of prepalatal obstruents (pp. 68, 70–71). The variants elicited for the meaning ‘eye’ included [óʒo], [óʒu], and [óxo], as attested in previous studies. One heritage participant in particular, a bilingual speaker of JS and Cuban Spanish, consistently pronounced JS intervocalic /ʒ/ as voiceless [∫]. Along with this speaker’s productions in (9), we give the corresponding pronunciations in Istanbul JS. Kirschen describes the process as an innovation, since intervocalic /ʒ/ did not devoice historically in JS.

| (9) | South Floridian JS idiolect | Istanbul JS | ||

| [í∫o] | [íʒo] | ‘son’ | ||

| [oɾé∫a] | [oɾéʒa] | ‘ear’ | ||

| [ó∫a] | [óʒa] | ‘leaf’ | ||

| [ó∫o] | [óʒo] | ‘eye’ | ||

| [vjé∫o] | [vjéʒo] | ‘old’ |

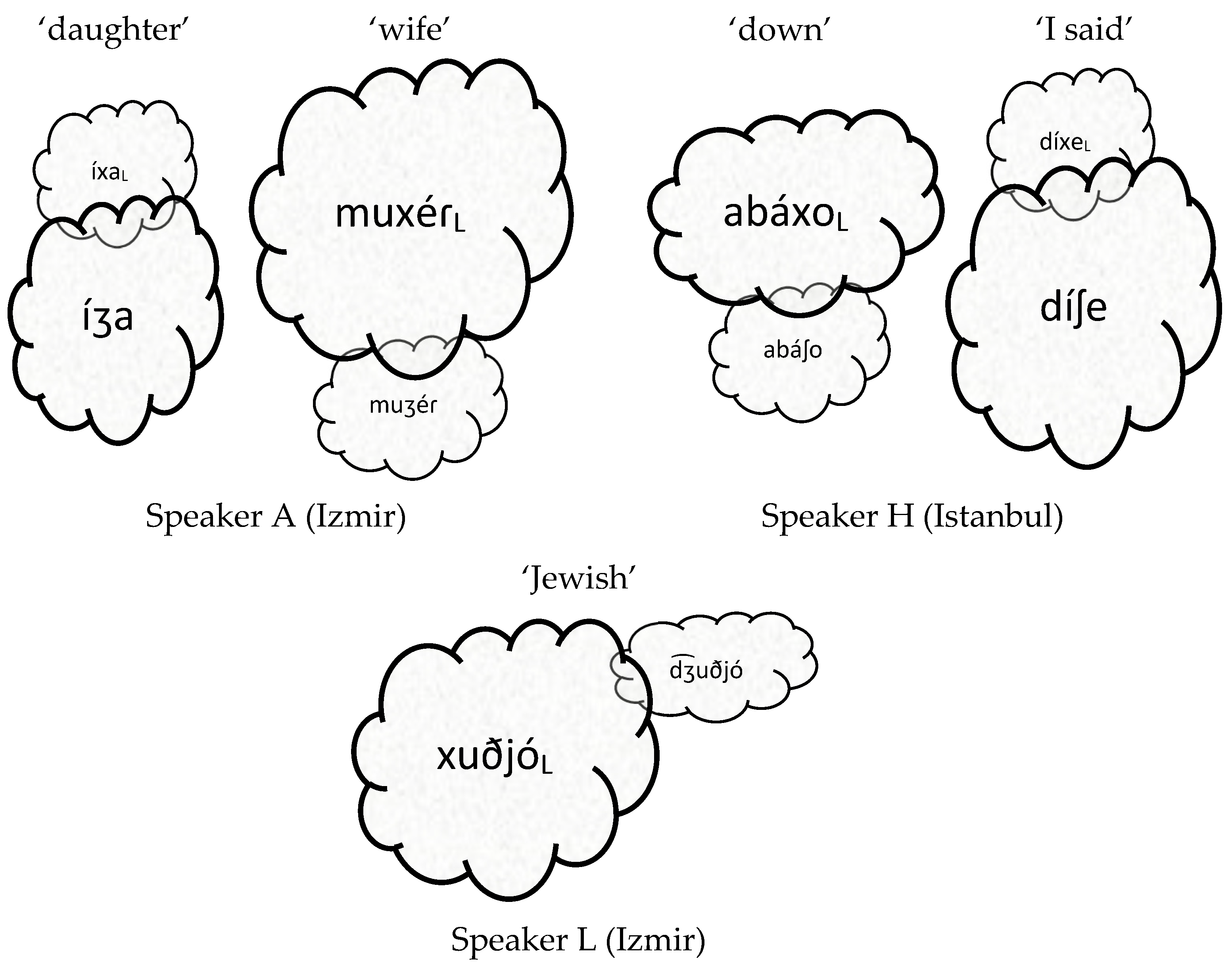

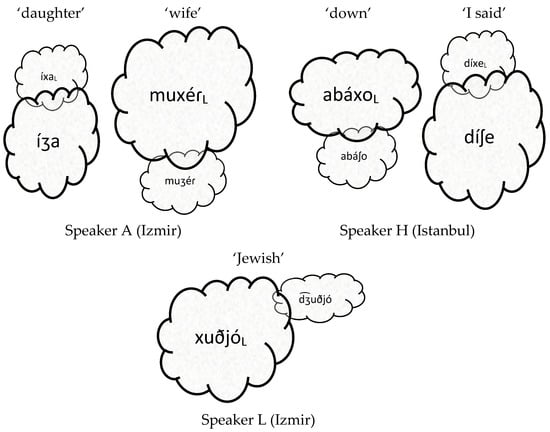

Drawing from the newly created Corpus Oral del Judeoespañol de Turquía del Siglo XXI (COJUT XXI), Spiegel (2020) documents variation in the pronunciation of Turkish, French, and MS loanwords within the Sephardic communities of Istanbul and Izmir, Turkey, both of which are highly multilingual. Besides JS and Turkish, many community members also include French, MS, Hebrew, Italian, and/or English as part of their linguistic repertoire. Spiegel analyzes transcripts of biographical-narrative interviews in JS recorded in 2015 and 2016 with 30 speakers (15 from each community) to obtain frequency counts of different lexical variants that are commonly cited in the previous literature. Of the 30 total participants, six from Izmir and eight from Istanbul are reported to have had contact with MS, either through work in tourism, by traveling to or having family members in countries where MS is spoken, or by taking classes in MS (pp. 239, 254–59). Table 2 gives a quantitative illustration of the rates of accommodation to MS /x/, drawing from the interview data of two such participants from Izmir and one from Istanbul. Within each of the five lexemes, phonological variants are ordered vertically, with more frequent realizations at the top. Different lexemes favor /∫/, //, /ʒ/, and /x/ at different rates. For example, Speaker A favors /ʒ/ at a combined rate of 73% vs. /x/ at 27% for ‘son/daughter’ but at the same time prefers /x/ at 69% vs. /ʒ/ at 31% for ‘wife’. Speaker H produces ‘down/to descend’ with /x/ at an overall rate of 71% vs. /∫/ at 29% but simultaneously produces ‘to say’ with /∫/ at 96% vs. /x/ at 4%. Speaker L pronounces ‘Jewish’ with /x/ at 73% vs. // at 27%. Spiegel’s quantitative results corroborate the findings of previous studies on accommodation in late-20th and early-21st century Sephardic communities. Not all community members show uniform variability across the entire lexicon. Instead, there is speaker- and word-specific variation. It is clearly not the case that all native JS words inherited from Medieval Spanish show accommodation to MS /x/ at the same rates.

Table 2.

Token frequency counts from the COJUT XXI showing intra- and inter-speaker variation in accommodation to MS /x/, based on the lexemes for ‘son/daughter’, ‘wife’, ‘down/to descend’, ‘to say’, and ‘Jewish’, as pronounced by three Turkish JS speakers whose linguistic repertoire also includes MS (adapted from Spiegel 2020, pp. 271, 277–78, 284).

A reviewer asks whether the variability reported in the above studies might also be related to the fact that the JS speakers were aware that the MS cognates contain /x/ but that, in the interview situation with a person who was obviously not a native speaker of JS, they tried to accommodate to the MS norm but failed to do so consistently. Because Romero (2013, 2016), Kirschen (2019), and Spiegel (2020) took care to conduct their sociolinguistic interviews in JS, the participants were less likely to try and accommodate to MS pronunciation norms during the field recording sessions. On the importance of inducing a monolingual language mode in experimental production studies with bilinguals, see Amengual (2012, p. 525). Furthermore, Spiegel’s frequency data from the COJUT XXI reveal speaker- and word-specific effects, which suggest that variability is not entirely random but instead structured, most likely on the basis of individual speakers’ previous experiences with MS interlocutors and speech communities.

In the remainder of this paper, we motivate a formal analysis of voiced prepalatal obstruents in terms of fortition and continuity lenition within a core-periphery model of the JS lexicon. We apply this model to account for the evolution of voiced prepalatals under language contact, with Medieval Spanish as a comparative starting point.

3. Fortition, Continuity Lenition, and the Voiced Prepalatal Alternation

Katz (2016) distinguishes between two types of consonant lenition. Loss lenition removes a feature or a segment from the phonological representation, tends to apply in contexts of diminished perceptibility, and may cause positional neutralization of phonological contrasts. An example of loss lenition is coda obstruent debuccalization, which neutralizes the place contrast among syllable-final obstruents to [ʔ], [h], or [Ø]. On the other hand, continuity lenition entails an increase in consonant intensity and possibly a decrease in duration, tends to apply in perceptually prominent positions, such as between vowels, and typically does not lead to positional neutralization of phonological contrasts. Two common processes of continuity lenition are the voicing of intervocalic voiceless obstruents and the spirantization of intervocalic voiced obstruents. Conjointly with the opposite processes of fortition, i.e., devoicing to a voiceless obstruent and strengthening to a voiced stop or affricate, processes classified as continuity lenition result in a surface pattern of weaker allophones appearing within prosodic domains and stronger allophones appearing at domain edges. The functional basis of continuity lenition is that it creates a segmental distribution that conveys information to the listener about the prosodic structure of the utterance (Keating 2006; Kingston 2008; for supporting evidence from psycholinguistic experimentation, see Katz and Fricke 2018; Katz and Moore 2021). “The motivation behind this pattern is that it aligns auditory disruptions with constituent boundaries, and lack of disruption with lack of boundaries, which plausibly helps a listener detect where the boundaries are” (Katz 2016, p. 47). As a prime example of continuity lenition, Katz describes the weakening of voiced stops /b/, /d/, /ɡ/ to spirant approximants [β], [ð], [ɣ] after vowels and certain consonants in MS, as observed in phonetic transcriptions of two speakers from Venezuela, and cites similar alternations in other languages, to which we also can add JS (see note 3). Cross-linguistically, spirantization “is most frequently observed between vowels and sonorant consonants, less frequently in medial clusters and final position, and is often blocked following nasals. It rarely results in positional neutralization of contrasts found elsewhere in a language” (Katz 2016, p. 51).

According to Hualde (2013), the alternation between word-initial [] and [ʒ] in Medieval Spanish was the result of a lenition process that changed underlying // to [ʒ] between vowels. A possible alternative analysis might posit phonemic /ʒ/ and a process of fortition to [] after a pause or a nasal consonant. Which of the two alternants was, in fact, underlying? From the perspective of contemporary phonological theory, the answer to this question turns out to be irrelevant. In the framework of Optimality Theory (henceforth, OT; Prince and Smolensky 2004; McCarthy and Prince 1999; McCarthy 2008), faithfulness constraints require the output value of the phonological feature of a segment to match the value specified in the corresponding segment in the input, while markedness constraints penalize outputs that contain phonotactically ill-formed structures. In line with the OT tenet known as Richness of The Base (ROTB), generalizations about a language’s inventory of sounds in the output must emerge from the phonological grammar, i.e., constraint ranking, and not from any restrictions placed directly on the input, nor from some combination of input restriction and phonological operation or constraint (Prince and Smolensky 2004, pp. 205, 225; McCarthy 2002, pp. 70–71, 2008, pp. 88–95). It does not matter whether the input in Medieval Spanish contains // or /ʒ/ because their surface distribution should be predictable entirely by constraint interaction in the phonological grammar.

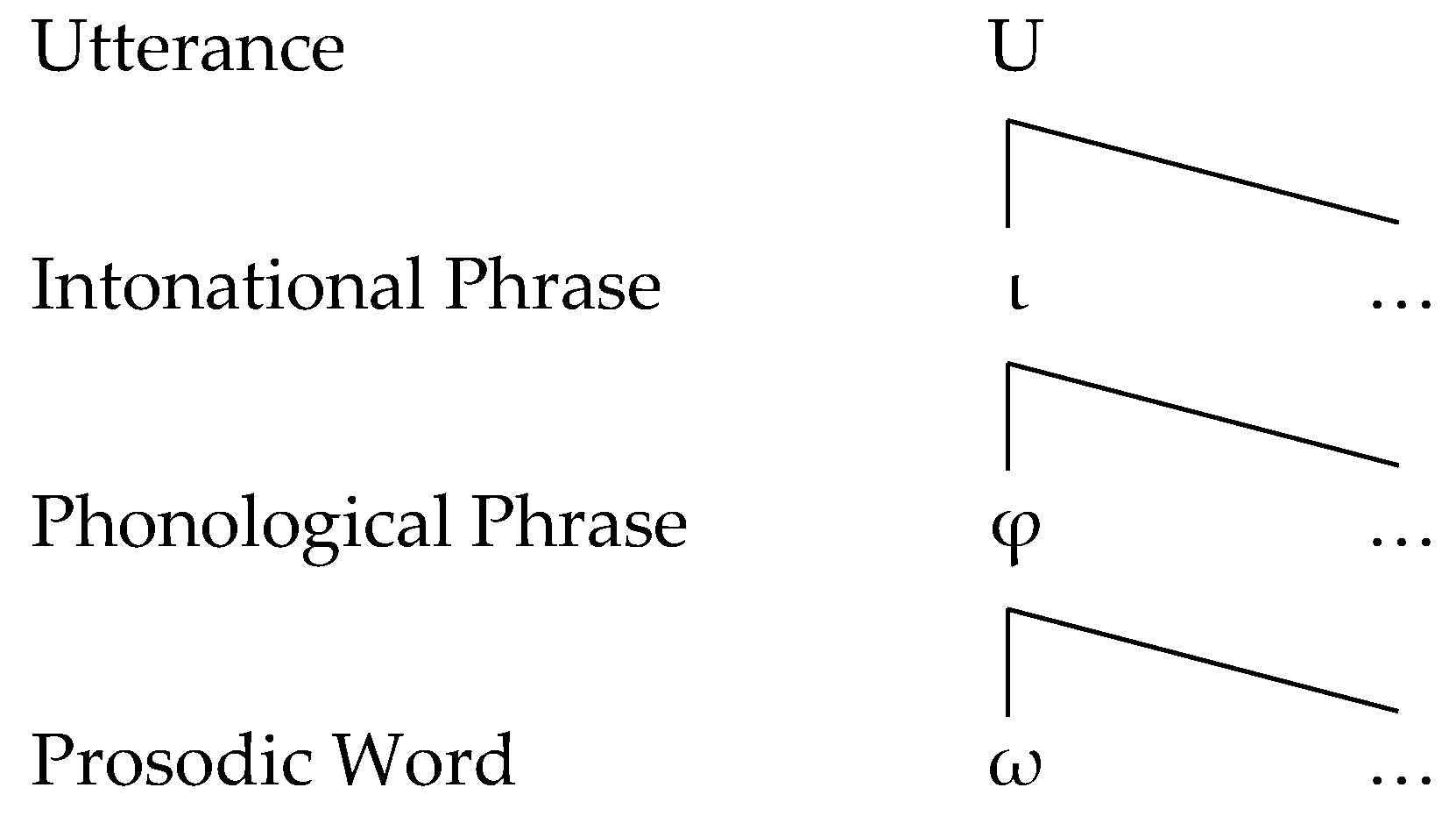

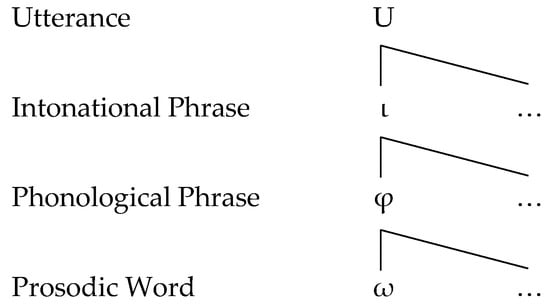

We propose to interpret the voiced prepalatal obstruent alternation in Medieval Spanish as an instance of continuity lenition, in which utterance-initial fortition to [] operates in conjunction with utterance-medial spirantization to [ʒ]. Since we posit the entire Utterance in Figure 1 as the prosodic domain of the alternation, our interpretation is consistent with the Neogrammarian hypothesis that, in its initial stages, spirantization of // would not have been blocked by word or prefix boundaries (Hualde 2013, pp. 232–40). Given its initial closure period, the voiced affricate is arguably less intense than the voiced fricative. Spirantization applies between vowels, which is a perceptually prominent position, and is blocked following nasals. Since [] and [ʒ] are non-contrastive variants of a single phoneme, spirantization does not result in positional neutralization of a phonological contrast. Rather, the surface distribution of these two consonants is completely predictable across all of the phonological contexts in which they occur. These are the hallmark properties of continuity lenition as defined by Katz (2016).

Figure 1.

Domains of the prosodic hierarchy, showing only the Prosodic Word and above (adapted from Bonet 2020, p. 333; see also Selkirk 1978, 1984, 1986; Nespor and Vogel 1986).

To explain why continuity lenition typically does not result in the positional neutralization of phonological contrasts, Katz (2016) argues that the process requires a formal treatment in OT that is distinct from the treatment of loss lenition. In an analysis of spirantization, (10a) requires faithfulness to the feature [continuant], which distinguishes the natural class of stops and affricate consonants from the class of fricatives and spirant approximants. Unlike stops, affricates can be defined as [+delayed release] (Hayes 2009, pp. 79–80), not shown here. (10b) is relevant to the analysis of obstruent [voice] alternations.

| (10) | a. | Identity(continuant) Let α be a segment in an input and β be a correspondent of α in the output. Assign a violation if α is [γcontinuant], and β is not [γcontinuant]. |

| b. | Identity(voice) Let α be a segment in an input and β be a correspondent of α in the output. Assign a violation if α is [γvoice], and β is not [γvoice]. |

If indeed separate markedness constraints were responsible for intervocalic lenition and edge fortition, then it should be possible for some language to rank (10a) or (10b) between the two constraints. However, either such ranking would incorrectly predict neutralization of continuancy or voicing contrasts in the position targeted by the higher ranking markedness constraint, as well as contrast maintenance in the position targeted by the lower ranking markedness constraint. Continuity lenition is special because it requires an interaction between faithfulness and a single markedness constraint that is responsible for both lenition and fortition.7 Katz (2016, p. 56) proposes a new family of Boundary-Disruption constraints that have exactly this property. The definition in (11) enforces opposite requirements in complementary positions in the output, depending on whether the target segment appears inside or at the edge of a given prosodic domain. Such a distribution serves to increase the perceptibility of domain boundaries.8

| (11) | Boundary-Disruption(I,D,P) Intensity drops to amount I or lower for at least duration D at and only at a prosodic boundary of level P. |

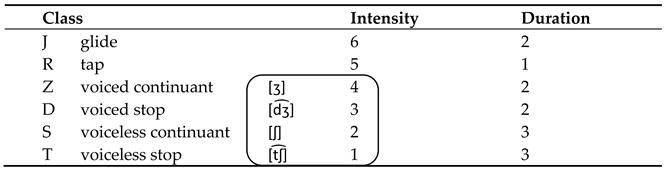

Table 3 shows the relative values of intensity (I) and duration (D) that Katz hypothesizes for various natural classes of segments. We add IPA symbols for four prepalatal obstruents to the left of their respective intensity values and assume that affricates rank with stops. Consonants that are auditorily more disruptive between vowels have lower intensity and longer duration. The parameter P in (11) ranges over the prosodic domains shown in Figure 1, which omits constituents below the Prosodic Word for convenience. The prosodic hierarchy is governed by the Strict Layer Hypothesis (Selkirk 1986): lower constituents are contained by the next highest constituent, and levels are not skipped.9

Table 3.

Intensity and duration values for major consonant classes (adapted from Katz 2016, p. 57).

Analyzing prosodically based continuity lenition of the voiced stops /b/, /d/, /ɡ/ in U.S. Spanish of Colombian heritage, Lozano (2021) reformulates (11) so as to define intensity thresholds according to a consonant’s position within a specified prosodic domain:

| (12) | a. b. | Intensity≤nDomain Assign a violation for every consonant of intensity ≤n that is not edge-adjacent in a prosodic Domain edge-adjacent consonant in a prosodic Domain that is not of intensity ≤n |

This revised format offers several advantages over (11) to an analysis of // spirantization. First, while voicing lenition can be analyzed as “a secondary consequence of shortening” (Katz 2016, p. 64) based on a reduction in duration, the main acoustic correlate of spirantization turns out to be intensity. In fact, the relative ordering of intensity values in Table 3 is overwhelmingly supported by phonetic studies of different monolingual varieties of Spanish (Martínez-Celdrán 1984; Lavoie 2001; Parker 2002; Carrasco 2008; Martínez-Celdrán and Regueira 2008; Colantoni and Marinescu 2010; Eddington 2011; Carrasco et al. 2012; Figueroa 2016; Broś et al. 2021). The definition in (12) altogether omits reference to duration. Second, (12) adheres to McCarthy’s (2003) proposed convention of defining categorical markedness constraints by explicitly stating the conditions that must hold of a given locus of violation within an output candidate in order for a violation to be triggered, i.e., “Assign a violation for every…” Third, the revised constraint unpacks the phrase “at and only at” in (11) by defining the lenition context (12a) separately from the fortition context (12b). In our experience, separating the two clauses in this way makes it easier to know when a particular candidate violates a given Intensity constraint.

The scale in Table 3 ranks natural classes of segments by the degree to which they disrupt the stream of flanking vowels, which we assume have an intensity index of 7. Intensity contours can be represented quantitatively by converting [VCV] strings into numerical sequences, situated along a continuum of relative flatness. In Figure 2, intensity values are given below their corresponding segments. We include the prepalatal obstruents here, foreshadowing their appearance in the analysis to come. The intervocalic glide is the least disruptive, dropping intensity by just one level in 767. Intervocalic [] is the most disruptive, dropping intensity by six levels in 717.10

Figure 2.

Ranking of [VCV] intensity contours by relative flatness. Flatter contours appear to the left, and greater dips in intensity appear to the right.

The constraint schema in (12) raises consonantal intensity and produces flatter [VCV] contours in the absence of a specified prosodic boundary and, at the same time, lowers consonantal intensity and produces more disruptive [VCV] contours when the consonant appears at the edge of such a boundary. This schema projects individual constraints as a function of specific intensity values and prosodic domains. For example, twelve such constraints define cutoffs for intensity levels 1–3 across the four highest prosodic domains:

| (13) | Intensity≤3u | Intensity≤3ι | Intensity≤3φ | Intensity≤3ω | |

| Intensity≤2u | Intensity≤2ι | Intensity≤2φ | Intensity≤2ω | ||

| Intensity≤1u | Intensity≤1ι | Intensity≤1φ | Intensity≤1ω |

Because they refer to scales, the constraints in (13) form stringency hierarchies (de Lacy 2004) in OT. Given a pair of constraints, the more general of the two is said to be the more stringent because it assigns more violations to the same set of candidates than the more specific, less stringent constraint assigns. Violations of the more stringent constraint form a superset of, or contain, the violations of the less stringent constraint; conversely, violations of the less stringent constraint form a subset of, or are contained by, the violations of the more stringent constraint. The harmony, or relative well-formedness, of each output candidate remains the same no matter how the stringently related constraints are ranked with respect to each other. As a result, the ranking of constraints in (13) need not be universally fixed in order to define prosodically based intensity thresholds, which emerge instead from the interaction between faithfulness and the highest ranking Intensity constraint in the grammar of a given language. For further discussion of the stringency relationship among Intensity constraints, see Lozano (2021, pp. 117–39).

We argue that the ranking of Intensity≤3u above Identity(cont) and the other Intensity constraints predicts the complementary distribution of Medieval Spanish [] and [ʒ]. We begin with an analysis of the word-initial phrasal alternation (1c–e). Tableau (14) evaluates eight input-output mappings: four in word-initial Utterance-medial position (14a–d) and four in Utterance-initial position (14e–h). ‘#’ denotes a word boundary. In accordance with ROTB, we consider both // and /ʒ/ as possible inputs in each of the two positions. To focus the analysis, we show violations of Intensity≤3u only for prepalatal obstruents. Candidate evaluation proceeds as follows. (14a,c) violate clause (12a) because [] is of intensity 3 but is not edge-adjacent in the prosodic domain of the entire Utterance, denoted as (…)U. (14b,d) satisfy (12a) because non-edge-adjacent [ʒ] is of intensity 4. (14f,h) violate (12b) because [ʒ] is edge-adjacent in the Utterance but is not of intensity level 3 or lower. (14e,g) satisfy (12b) because edge-adjacent [] is of intensity 3.

The unfaithful mappings in (14b,g) are crucial in showing that the grammar forces voiced prepalatal obstruents to undergo spirantization and fortition, respectively, to avoid the violations of Intensity≤3u in (14a,h).

| (14) | Intensity≤3u | Identity(cont) | ||

| a. /la#énte/ | (…laénte…)U 737 | *! | ||

| ☞ | b. | (…laʒénte…)U 747 | * | |

| c. /la#ʒénte/ | (…laénte…)U 737 | *! | * | |

| ☞ | d. | (…laʒénte…)U 747 | ||

| ☞ | e. /énte/ | (énte…)U 37 | ||

| f. | (ʒénte…)U 47 | *! | * | |

| ☞ | g. /ʒénte/ | (énte…)U 37 | * | |

| h. | (ʒénte…)U 47 | *! |

Tableau (15) gives the analysis of word-medial intervocalic position (1f), again assuming both // and /ʒ/ as possible inputs. Intensity≤3u rules out the 737 contours in (15a,c), as it does in word-initial Utterance-medial position (14a,c). The relatively flatter 747 contours in (15b,d) are optimal, as in (14b,d):

| (15) | Intensity≤3u | Identity(cont) | ||

| a. /óo/ | (…óo…)U 737 | *! | ||

| ☞ | b. | (…óʒo…)U 747 | * | |

| c. /óʒo/ | (…óo…)U 737 | *! | * | |

| ☞ | d. | (…óʒo…)U 747 |

Continuity lenition alone fails to explain postnasal hardening in domain-medial contexts. Assuming that nasal stops rank with voiced continuants at intensity level 4 (Katz 2016, p. 67), Intensity≤3u actually favors [nʒV] (447) because it makes a flatter intensity contour than [nV] (437). Building upon various definitions by Katz (2016, p. 62), Colina (2020, p. 8), and Martínez-Gil (2020, p. 57), we adopt the following markedness constraint:

| (16) | Agree(continuant) Assign a violation for every voiced obstruent that does not agree in the feature [continuant] with a preceding consonant. |

Tableau (17) adds this constraint at the top of the hierarchy established thus far. Although (17b,d) contain a flatter intensity contour, the [nʒ] cluster fatally violates Agree(cont), on the assumption that nasal stops require an articulatory closure in the oral cavity. (17a,c) are optimal because in the [n] cluster, the affricate and the preceding nasal stop share the same [−continuant] value. An alternative agreement strategy, not shown here, is to map the input nasal stop to [+continuant] in the output, as in [koʒénte]. This change is ruled out by a high ranking constraint against nasal continuants, which are extremely marked segments cross-linguistically (see Cohn 1993; Padgett 1994; Shosted 2006; Kingston 2008, p. 16; Katz 2016, p. 62).11

| (17) | Agree(cont) | Intensity≤3u | Identity(cont) | ||

| ☞ | a. /kon#énte/ | (…konénte…)U 437 | * | ||

| b. | (…konʒénte…)U 447 | *! | * | ||

| ☞ | c. /kon#ʒénte/ | (…konénte…)U 437 | * | * | |

| d. | (…konʒénte…)U 447 | *! |

The low ranking of Identity(cont) explains why the continuancy distribution in Medieval Spanish voiced prepalatal obstruents is non-contrastive and entirely predictable. On the other hand, prepalatal obstruents do not alternate in voicing, which points to a high ranking of faithfulness to [voice] (10b). Tableau (18) evaluates possible mappings of word-medial intervocalic // and /∫/ (1a,b), including changes in continuancy, voicing, and both features simultaneously:

| (18) | Identity(voi) | Intensity≤3u | Identity(cont) | ||

| ☞ | a. /nóe/ | (…nóe…)U 717 | * | ||

| b. | (…nó∫e…)U 727 | * | *! | ||

| c. | (…nóe…)U 737 | *! | * | ||

| d. | (…nóʒe…)U 747 | *! | * | ||

| e. /bá∫o/ | (…báo…)U 717 | * | *! | ||

| ☞ | f. | (…bá∫o…)U 727 | * | ||

| g. | (…báo…)U 737 | *! | * | * | |

| h. | (…báʒo…)U 747 | *! |

Although 747 is the only intensity contour that satisfies Intensity≤3u, mappings (18d,h) fatally violate Identity(voi), as do (18c,g). Since [] and [∫] fall below the level 3 intensity threshold, the remaining candidates within each evaluation violate Intensity≤3u equally. The tie is broken by lower ranking Identity(cont), which maintains the input contrast between // (18a) and /∫/ (18f).

Faithfulness to [voice] also explains why Utterance-initial /ʒ/ does not devoice. Both (énte…)U and (∫énte…)U satisfy Intensity≤3u, but mapping the input /ʒénte/ to either of these outputs would fatally violate high ranking Identity(voi). Fortition to a voiced prepalatal affricate is the optimal strategy for creating a great enough intensity dip at the left edge of the Utterance domain, as seen in (14g).

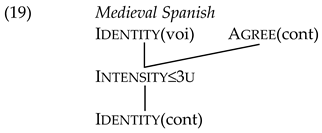

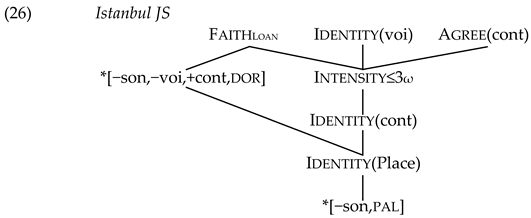

The constraint ranking for Medieval Spanish is summarized by the Hasse diagram in (19). A vertical line connects a given constraint to the constraint it dominates:

4. A Core-Periphery Model of the Istanbul JS Lexicon

The ranking in (19) also must have been active in JS at the time of the late-15th century expulsion. To model the innovative evolution of voiced prepalatal obstruents under language contact in the diaspora, our analysis requires a few more markedness constraints that make reference to segmental features. Table 4 lists the minimal feature specifications necessary to define the five obstruent, or [−sonorant], segments of interest. We use pal(atal) and dor(sal) as convenient labels to differentiate between the prepalatal obstruents, which activate both the tongue blade and tongue dorsum, and the voiceless velar fricative, which activates only the tongue dorsum. See Zampaulo (2019, pp. 31–45) for a detailed discussion of the phonetic characteristics of various palatal segments, including the prepalatal obstruents analyzed here.

Table 4.

Phonological features that define five obstruent consonants.

We assume that context-free markedness constraints can be projected from whichever feature combinations most adequately capture the patterning of natural segmental classes as observed in a given language variety. For example, the surface inventory of the native lexicon in late-15th century Medieval Spanish included the prepalatals [], [∫], [], and [ʒ], as well as the voiceless velar stop [k] (1a,d), but lacked a voiceless velar fricative [x]. This generalization can be captured by a low ranking of the markedness constraint *[−son, pal], which assigns a violation for every output prepalatal obstruent, and a high ranking of *[−son, −voi, +cont, dor], which assigns a violation for every output fricative [x], but not for the stop [k]. In addition to the faithfulness constraints in (10), we assume Identity(Place), which penalizes corresponding input and output segments that differ in place of articulation features.

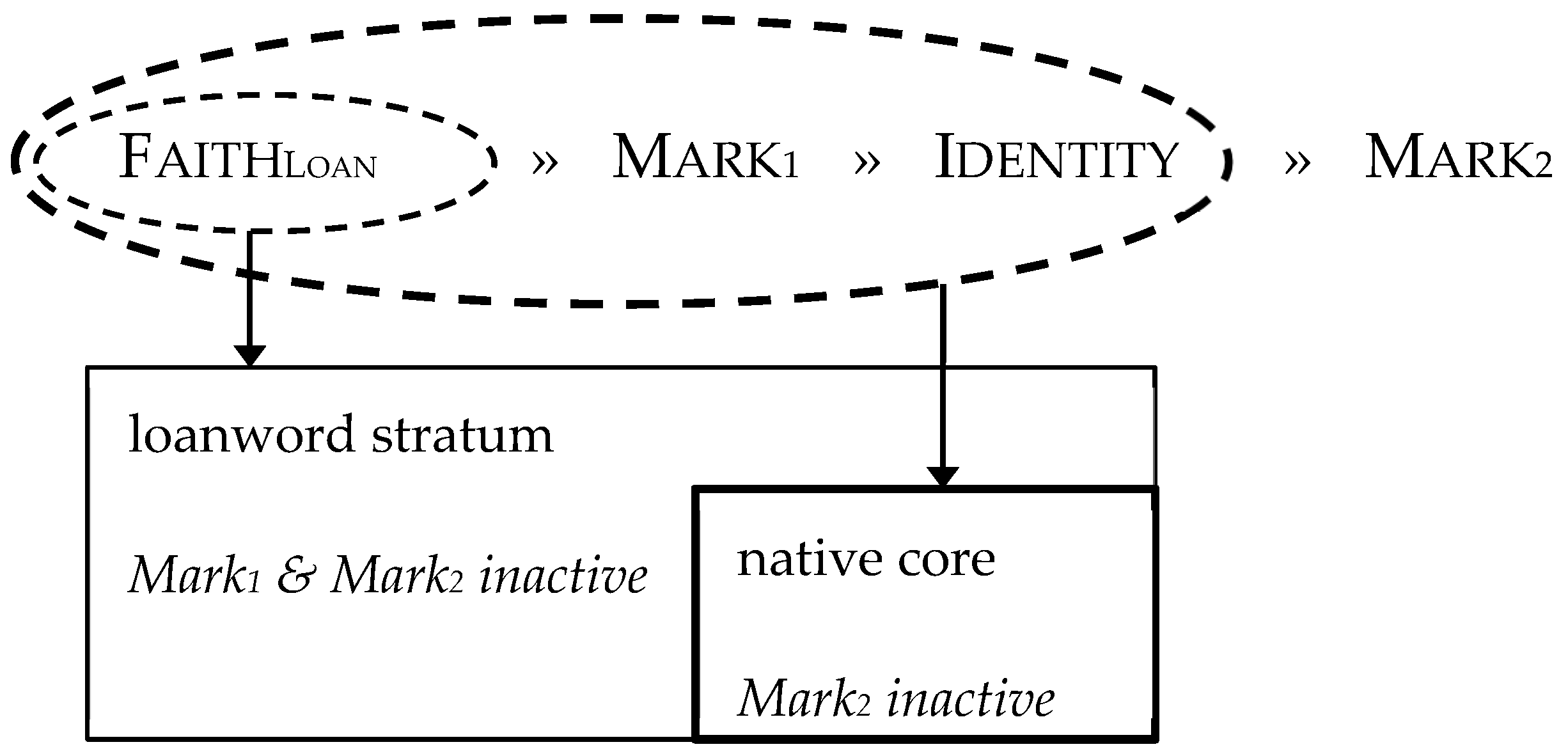

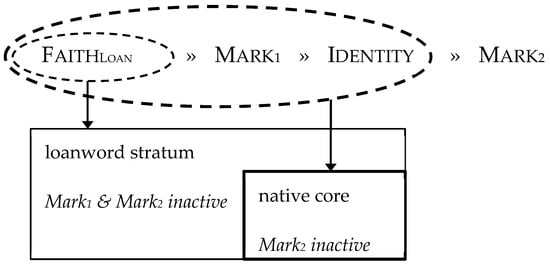

Our account of the role of lexical borrowing in JS makes use of a general faithfulness constraint that refers specifically to words that do not belong to the native core lexicon. In OT, lexical indexation of constraints makes it possible to account for phonological patterns that are observed only in specific classes of morphemes. Pater (2007, 2010) and Coetzee (2009) argue that both markedness and faithfulness can be indexed to sets of items in the lexicon as a way to capture morpheme-specific triggering and blocking effects, respectively. In their model of the Japanese lexicon, Ito and Mester (1999, 2009b) propose to restrict lexical indexation to faithfulness constraints, which are indexed to four separate lexical strata and interspersed among a hierarchy of non-indexed markedness constraints. The native core lexicon of Japanese is subject to the greatest number of markedness constraints, whose effects are blocked by higher ranking faithfulness constraints that are indexed to more peripheral strata. The interleaving of markedness and lexically indexed faithfulness mirrors the nested structure of Japanese lexical strata and is able to account for the various degrees of loanword assimilation that have been observed in the language.

A conservative hypothesis—and the correct one, as far as we can tell—is that JS imposes a binary distinction between the native core lexicon (i.e., morphemes inherited directly from the predecessor language, Medieval Spanish) and a single peripheral stratum that includes representations of lexical borrowings, such as loanwords. Identity constraints apply by default to the native vocabulary, but items from the loanword stratum are lexically marked with a subscript L diacritic that indexes them to a different faithfulness constraint, which we define as follows:

| (20) | FaithLoan Let α be a segment in an input from the loanword stratum and β be a correspondent of α in the output. For each feature F ∈ {continuant, voice, Place…}, assign a violation if α is [γF], and β is not [γF]. |

The constraint name comes from Simonovič (2009, 2015), who discusses so-called ‘onion’ models of lexical stratification that involve indexation of various faithfulness constraints, as in Ito and Mester’s (1999, 2009b) analysis of Japanese. The formal definition in (20) is ours. It allows for a single constraint to assign multiple violations to a given candidate depending on the number of unfaithful feature mappings that occur within a diacritically marked morpheme. For example, the mapping of // → [x] within a native morpheme violates Identity(cont), Identity(voi), and Identity(Place) but not FaithLoan. The same mapping within a loanword incurs three violations of FaithLoan but vacuously satisfies the three Identity constraints.

Figure 3 schematizes the core-periphery model. Given a set of markedness (Mark) constraints, their interaction with FaithLoan and Identity predicts that the segmental inventory of the JS native core lexicon will be a subset of the full inventory of segments that are observed in the language more broadly, as illustrated by the overlapping rectangles.

Figure 3.

A core-periphery model of the Istanbul JS lexicon.

Tableau (21) incorporates FaithLoan and *[−son, pal] into the hierarchy in (19), omitting Identity(voi) and Agree(cont). To save space, we no longer include numerical intensity contours beneath output candidates. The first two inputs are repeated from (14g,h) and (15a,b). The other two are representations of loanwords, marked by the subscript L: /ʒúʁL/ based on French jour ‘day’ (3a) and /aémL/ based on Turkish Acem ‘Persian’ (2d). The dashed line between the rightmost two columns indicates that the ranking of Identity(cont) and *[−son, pal] is yet to be determined. Within the native lexicon, the ranking of Intensity≤3u above Identity(cont) optimizes Utterance-initial fortition (21a) and Utterance-medial spirantization (21d). Voiced prepalatal obstruents appear in the same phonological contexts within loanword outputs (21e–h), thereby incurring the same violations of Intensity≤3u. However, the loanword inputs are lexically indexed to higher ranking FaithLoan, which blocks fortition (21e) and spirantization (21h). As this comparison shows, the late-15th century JS grammar allows voiced prepalatal obstruents to surface faithfully in the peripheral loanword stratum (21f,g) but otherwise requires a continuancy alternation in the native core (21a,d). Lexical indexation can also explain why spirantization is blocked in numerals influenced by Catalan and Aragonese borrowings and in Italianisms (4). Inputs /dóeL/, /póoL/, etc., are predicted to pattern such as /aémL/ (21g).

| (21) | FaithLoan | Intensity≤3u | Identity(cont) | *[−son,pal] | ||

| ☞ | a. /ʒénte/ | (énte…)U | * | * | ||

| b. | (ʒénte…)U | *! | * | |||

| c. /óo/ | (…óo…)U | *! | * | |||

| ☞ | d. | (…óʒo…)U | * | * | ||

| e. /ʒúʁL/ | (úʁ…)U | *! | * | |||

| ☞ | f. | (ʒúʁ…)U | * | * | ||

| ☞ | g. /aémL/ | (…aém…)U | * | * | ||

| h. | (…aʒém…)U | *! | * |

Even though /x/ is absent from the JS native lexicon, our analysis still needs to show how the phonological grammar would repair such an input fricative, in keeping with ROTB. Tableau (22) includes /xavón/ as a hypothetical input for [∫avón] ‘soap’ (1b) in comparison with the loanword input /xoáL/ based on Turkish hoca ‘Muslim priest’ (2d). A dashed line between columns indicates that the two constraints are not (yet) crucially ranked. Because the constraint against [x] outranks both Identity(Place) and *[−son, pal], hypothetical input /x/ in native morphemes is forced to surface as a prepalatal obstruent [∫] (22b). The ranking of Identity(cont) above Identity(Place) prevents the alternative strategy of strengthening /x/ to [k] (22c). Ranked above *[−son, −voi, +cont, dor] and Intensity≤3u, FaithLoan blocks the mappings /x/ → [∫] and // → [ʒ] (22e–g), which ensures that input /x/ and // surface faithfully within the loanword (22d).

| (22) | FaithL | *[−son,−voi,+cont,dor] | Int≤3u | Id(cont) | Id(Pl) | *[−son,pal] | ||

| a. /xavón/ | (xavón…)U | *! | ||||||

| ☞ | b. | (∫avón…)U | * | * | ||||

| c. | (kavón…)U | *! | ||||||

| ☞ | d. /xoáL/ | (xoá…)U | * | * | * | |||

| e. | (∫oá…)U | *! | * | ** | ||||

| f. | (xoʒá…)U | *! | * | * | ||||

| g. | (∫oʒá…)U | *!* | ** |

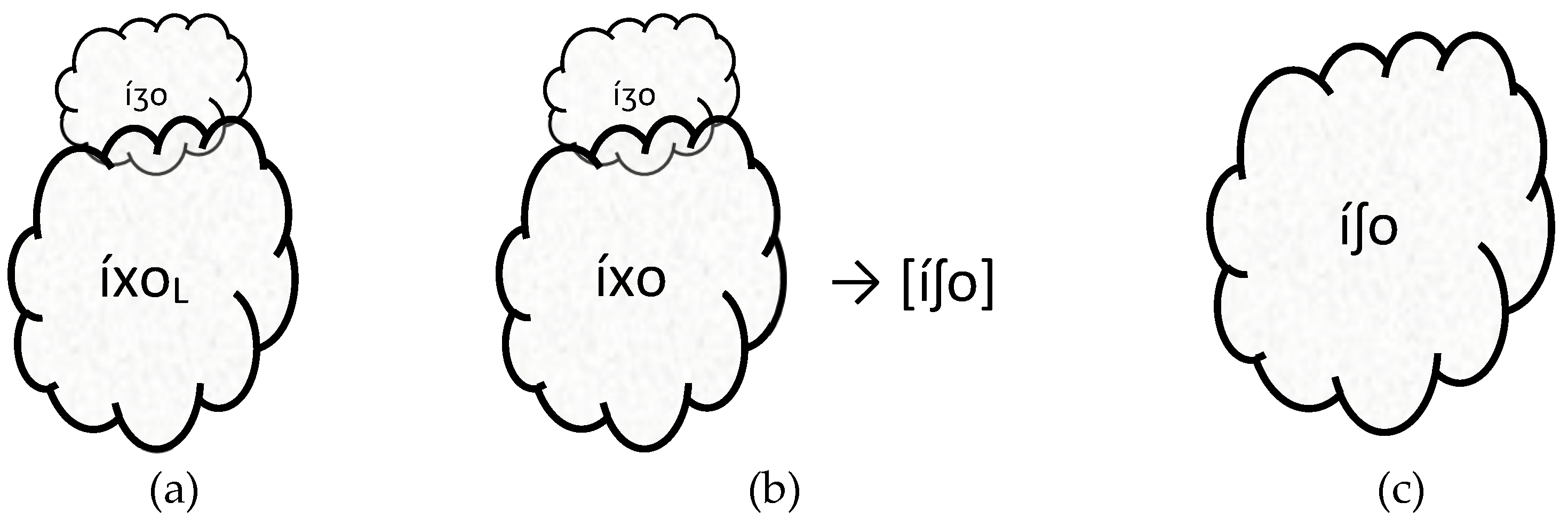

In the explanation proposed by Hualde (2013, pp. 250–55, 260), the loss of the word-initial voiced prepalatal alternation from Istanbul JS is tied to the phonemic split between // and /ʒ/. Once Turkish and French loanwords brought a new awareness that the two prepalatal obstruents were phonologically distinct, JS speakers reinterpreted // as the underlying phoneme in the initial position of words that were inherited from Medieval Spanish, leaving /ʒ/ restricted to word-medial intervocalic position. This explanation is not available within the core-periphery model in Figure 3, which regulates contrast in loanwords separately from contrast in the native lexicon. The necessary ‘split’ is not between two phonemes // and /ʒ/ but rather between two types of faithfulness constraint in the phonology, i.e., FaithLoan and Identity(cont). It is not immediately obvious how a change in the contrastiveness of voiced prepalatal obstruents in the peripheral loanword stratum could affect their distribution in the native lexicon. A re-ranking of Identity(cont) above Intensity≤3u would allow // and /ʒ/ in both initial and medial contexts to surface faithfully in native words, but this result is incorrect. What took place in the native lexicon was not a change in contrastiveness but rather a change in the surface distribution of the voiced affricate, which was merely generalized to word-initial intervocalic contexts.

A single re-ranking of two Intensity constraints can easily model the innovative generalization of word-initial []. In the grammar of late-15th century Medieval Spanish and JS, high ranking Intensity≤3u established the Utterance in Figure 1 as the prosodic domain of edge fortition and medial spirantization. Assuming that FaithLoan caused loanword // (2a) and /ʒ/ (3a) to be realized faithfully across all phrasal contexts, the absence of a word-initial alternation in lexical borrowings could have provided language learners with enough evidence to re-rank the Intensity constraints, thereby narrowing down the domain of the alternation from the Utterance to the Prosodic Word, but in the native core lexicon. Tableau (23) illustrates this new ranking of Intensity≤3ω above Intensity≤3u. The first input is repeated from (14c,d), and the second is a prefixed infinitive, from (6). ‘+’ denotes a stem-affix boundary. Only /ʒ/ is considered in the input, but the analysis would still work assuming //. Output candidates now include both Utterance and Prosodic Word constituents, omitting other prosodic domains for simplicity. Both the definite article /la/ and the prefix /a–/ are recursively adjoined to the following ω in the output, while inflectional suffixes fall within the same ω as the stem (see Elordieta 2014, pp. 31, 44 for a discussion of this prosodic representation in MS). Intensity≤3ω assigns fatal violations to (23b,d) because [ʒ] appears at the edge of a ω domain but is not of intensity level 3 or lower. Fortition to [] is optimal in candidates (23a,c), despite their violations of lower ranking Identity(cont) and Intensity≤3u.

| (23) | Intensity≤3ω | Identity(cont) | Intensity≤3u | ||

| ☞ | a. /la#ʒénte/ | (…(la(énte)ω)ω…)U | * | * | |

| b. | (…(la(ʒénte)ω)ω…)U | *! | |||

| ☞ | c. /a+ʒunt+áɾ/ | (…(a(untáɾ)ω)ω…)U | * | * | |

| d. | (…(a(ʒuntáɾ)ω)ω…)U | *! |

The re-ranking in (23) does not change the evaluation of other phonological contexts in Istanbul JS. Intensity≤3ω still ensures postpausal fortition (24a), because Utterance-initial segments are also ω-initial, as well as intervocalic spirantization within the ω domain (24b). Although Intensity≤3ω favors ω-initial fortition independently of the preceding segmental context in (24c), higher ranking Agree(cont) is still necessary to account for ω-medial postnasal hardening in examples such as (24d), repeated from (8b). Furthermore, high ranking Identity(voi) keeps prepalatal obstruents from undergoing a change in voicing, cf. the discussion surrounding Medieval Spanish (18).

| (24) | a. | ((énte)ω…)U | c. | (…(kon(énte)ω)ω…)U |

| b. | (…(óʒo)ω…)U | d. | (…(etɾanéɾo)ω…)U |

Finally, tableau (25) allows us to determine the ranking of the lowest two constraints in the hierarchies of both Medieval Spanish and JS. Identity(Place) favors the faithful candidate (25a), despite its violation of lower ranking *[−son, pal].

| (25) | Identity(Place) | *[−son,pal] | ||

| ☞ | a. /íko/ | (íko)ω | * | |

| b. | (kíko)ω | *! |

The complete ranking in Istanbul JS is summarized by the Hasse diagram in (26):

The core-periphery model can also account for lexically based differences in the realization of other segments, including cases in which borrowed words are combined with native JS affixes. For example, [ʒuʁnaléɾo] (3a) has both a uvular fricative /ʁ/ in the French nominal form and an apicoalveolar tap /ɾ/ in the JS agentive suffix. We assume that rhotic consonants are [+sonorant], [−nasal], and [−lateral], and that the markedness constraint *[+son, −nas, −lat, dor] assigns a violation for every output [ʁ], but not for [ɾ], which is cor(onal) because it activates the tongue tip. In tableau (27), the input combines /ʒuʁnalL/ (< French journal ‘newspaper’) and the JS suffix, shown here with a hypothetical input /ʁ/ to demonstrate compliance with ROTB. High ranking FaithLoan eliminates (27c,d) because the rhotic contained within the input loanword has switched from dor to cor in the output. The ranking of *[+son, −nas, −lat, dor] above Identity(Place) forces hypothetical /ʁ/ in the native JS suffix to surface as [ɾ] (27b). This ranking accounts for the general absence of /ʁ/ from Istanbul JS, except within morphemes that are diacritically marked as lexical borrowings. In principle, this approach can be extended to other segmental differences by ranking the appropriate markedness constraints between FaithLoan and the relevant Identity constraint(s).

| (27) | /ʒuʁnalL+éʁo/ | FaithLoan | *[+son,−nas,−lat,dor] | Identity(Place) |

| a. (ʒuʁnaléʁo)ω | **! | |||

| ☞ | b. (ʒuʁnaléɾo)ω | * | * | |

| c. (ʒuɾnaléʁo)ω | *! | * | ||

| d. (ʒuɾnaléɾo)ω | *! | * |

5. Variable Accommodation to MS /x/ in Contemporary Sephardic Communities

As indicated by the review of sociolinguistic studies in Section 2.2, the most recent century of the Sephardic diaspora has seen an ever-increasing degree of language contact with MS, leading many heritage speakers of JS to substitute /x/ in place of syllable-initial /∫/, //, or /ʒ/ in some words. Romero (2013, 2016) argues that accommodation to MS /x/ in the Sephardic communities of Istanbul and New York is driven by lexical borrowing: the process shows speaker- and word-specific variation, fails to affect some native JS words, and is unattested in Hebrew, Turkish, or French loanwords. Kirschen (2019) reports further evidence of variation and an innovative devoicing process affecting intervocalic /ʒ/. We now account for these patterns using the core-periphery model.

5.1. Variation among Lexical Representations

Tableau (28) shows how the JS grammar handles four different inputs: MS loanwords /óxoL/ (1f) and /xuðíoL/ (7b), native JS /óʒo/, and the hypothetical input /óxo/. High ranking FaithLoan requires /x/ in loanword inputs to be realized faithfully (28a,e). The voiced prepalatal fricative of native JS /óʒo/ surfaces faithfully (28l). (We leave it to the reader to confirm that hypothetical /óo/ also maps to [óʒo], violating lower ranking Identity(cont) in order to satisfy Intensity≤3ω.) ROTB makes a fourth input /óxo/ possible which, like /óʒo/ and hypothetical /óo/, lacks a subscript L. Identity(voi) prevents a change in voicing (28o,p), and the markedness constraint against [x] eliminates (28m). In the absence of a loanword diacritic, the phonology maps input /x/ to output [∫] (28n), as already seen in late-15th century JS (22b).

| (28) | FaithLoan | Identity(voi) | *[−son,−voi,+cont,dor] | Intensity≤3ω | Identity(cont) | Identity(Place) | *[−son,pal] | ||

| ☞ | a. /óxoL/ | (óxo)ω | * | * | |||||

| b. | (ó∫o)ω | *! | * | * | |||||

| c. | (óo)ω | *!** | * | * | |||||

| d. | (óʒo)ω | *!* | * | ||||||

| ☞ | e. /xuðíoL/ | (xuðío)ω | * | ||||||

| f. | (∫uðío)ω | *! | * | ||||||

| g. | (uðío)ω | *!** | * | ||||||

| h. | (ʒuðío)ω | *!* | * | * | |||||

| i. /óʒo/ | (óxo)ω | *! | * | * | * | ||||

| j. | (ó∫o)ω | *! | * | * | |||||

| k. | (óo)ω | *! | * | * | |||||

| ☞ | l. | (óʒo)ω | * | ||||||

| m. /óxo/ | (óxo)ω | *! | * | ||||||

| ☞ | n. | (ó∫o)ω | * | * | * | ||||

| o. | (óo)ω | *! | * | * | * | * | |||

| p. | (óʒo)ω | *! | * | * |

Faithfulness to the loanword stratum becomes relevant only for stored representations that individual speakers happen to have already marked as lexical borrowings during previous language contact experiences with MS. If a given morpheme is lexically indexed to FaithLoan, then input segments belonging to that morpheme will surface faithfully—even when the native lexicon forbids such segments in specific contexts or altogether. If a morpheme has no L diacritic, then the optimal realization will be determined by the interaction between the relevant markedness and Identity constraints. From this perspective, the variation observed within the same speaker and across different speakers and different words amounts to variation between alternate representations of a particular lexical item that are submitted to the grammar for evaluation. For example, the same speaker of Istanbul JS in (7a) produces both i[ʒ]as and i[x]as within the same sentence, which we argue reflects variation in the selection between alternate lexical representations /íʒa+/ and /íxaL+/ for the meaning ‘daughter’ plus the plural suffix.

The simplest explanation why JS speakers may substitute /x/ in place of /∫/, //, or /ʒ/ in native words but never do so in Hebrew, Turkish, and French loanwords is that, unlike MS, these three languages do not share with JS the necessary etymological cognates inherited from Medieval Spanish, in which corresponding velar and prepalatal obstruents occupy the same relative position in the segmental string. Given the Turkish word [aém] Acem ‘Persian’, JS speakers would have no reason to posit /axémL/ as a loanword representation because no such etymological cognate exists in MS (cf. persa ‘Persian’). However, /óxoL/ is a possible loanword representation because MS /óxo/ has the same etymological source as JS /óʒo/ (1f), in which /ʒ/ corresponds to /x/. On the other hand, /káxiL/, /kíxeL/, /móxkaL/, and /séxL/ are not viable loanword representations because such etymological cognates with /x/ do not exist in MS (cf. casi ‘almost’, quise ‘I wanted’, mosca ‘fly’, seis ‘six’). This account resonates with previous descriptions by Nemer (1981), Gilmer (1986), and Romero (2013, 2016), thereby reinforcing the claim that accommodation to MS /x/ is the result of lexical borrowing. That is, some JS speakers store representations of entire MS words, some of which happen to have /x/ where syllable-initial /∫/, //, or /ʒ/ appears in the JS cognate. If instead the process involved a simple replacement of phonemes without regard to lexical class, then the absence of unattested forms such as *[axém], *[káxi], *[móxka], etc., would be harder to explain.

5.2. An Exemplar-Based Model of Variable Lexical Accommodation

Using corpus data from present-day Sephardic communities in Turkey, Spiegel (2020) shows that variable accommodation to MS /x/ is not uniform across all speakers nor across the entire lexicon. Individual participants produce velar and prepalatal variants of different words at different frequency rates. While the core-periphery model in Section 5.1 allows for qualitatively different lexical representations, it makes no specific quantitative predictions about their surface variation, besides pure optionality. For example, a binary choice between /íʒa+/ and /íxaL+/ predicts an equal probability of either input surfacing faithfully. Unfortunately, this theoretical 50/50 split is not borne out in Table 2, as token frequency varies considerably across different words.

How might the core-periphery model incorporate such variability? A large body of research in the OT literature over the past three decades seeks to model variation in terms of differences in constraint ranking. An early proposal is to leave the constraint hierarchy only partially ordered and to have the grammar randomly chose one of the possible total orderings at a given evaluation time, resulting in variable outputs across multiple evaluations (Kiparsky [1993] 1994; Reynolds 1994; Anttila 1997). Another approach is Stochastic OT (Boersma 1997, 1998; Boersma and Hayes 2001), in which constraints are ranked along a numerical scale, and rankings are randomly increased or decreased by a ‘noise’ value at evaluation time. Constraints that are closer together on the scale will be more likely to vary in their stochastic ranking, thereby favoring different outputs. On the other hand, constraints are not ranked at all in Harmonic Grammar (Smolensky and Legendre 2006). Rather, the grammar calculates a numerical harmony score for each output candidate based on the sum of weighted constraint violation scores and chooses the most harmonic candidate as optimal. In Noisy Harmonic Grammar (Coetzee and Pater 2011; Boersma and Pater 2016), a random noise value, as in Stochastic OT, is added to each constraint weight, causing output candidates to vary in relative harmony across multiple evaluations. An alternative approach that combines random noise and weighted constraints is Maximum Entropy grammar (Johnson 2002; Goldwater and Johnson 2003; Hayes and Wilson 2008; Moore-Cantwell and Pater 2016), which defines a probability distribution over the set of output candidates from which optimal candidates are sampled.

The main drawback of a solely grammatical account of variation is that it predicts identical frequency rates across the entire lexicon, leaving no room for word-specific effects. Working within the Noisy Harmonic Grammar framework, Coetzee and Pater (2011, pp. 431−32) show how constraint indexation allows individual words in the lexicon to affect variable phonological processes. The researchers use English coronal stop deletion (e.g., jus’ < just, an’ < and) to illustrate their approach, in which different instantiations of faithfulness constraints are indexed to individual words in the lexicon. For those words whose final /t/ or /d/ delete less frequently, a higher weight is assigned to the Maximality constraints that prohibit deletion in various contexts. Conversely, words with higher deletion rates have a lower weighting of their indexed faithfulness constraints. In a related approach to Dutch voicing alternations, Moore-Cantwell and Pater (2016) index markedness constraints to individual lexical items within a Maximum Entropy grammar.

A potential drawback of both approaches using lexical indexation is constraint proliferation. As Fruehwald (2022) points out, proponents of lexically indexed constraints “do not suggest an upper limit on how many may be included in any given grammar. In principle, this means speakers could be tracking as many unique (and independent!) probabilities as there are items in their lexicons” (p. 7). Word-specific constraint indexation seems to us to be an unnecessary duplication of information that is ultimately lexical in nature and could be better encoded in the lexicon. An advantage of the core-periphery model in Figure 3 is its greater restrictiveness, as lexical indexation is limited to a single, general faithfulness constraint on feature mappings within loanwords.

To capture the speaker- and word-specific variability of accommodation to MS /x/, we adopt a usage-based representation of the mental lexicon (Bybee 2001, 2002, 2006; Docherty and Foulkes 2014; Hinskens et al. 2014), as formalized in Exemplar Theory (Johnson 1997; Pierrehumbert 2002, 2016; Wedel 2006, 2012; Frisch 2018). For our purposes, it is sufficient to assume an exemplar-based model in which word-sized tokens of linguistic experience are categorized by the individual JS user during the act of listening to the pronunciation of other speakers and to one’s own pronunciation. Traces of previously categorized word tokens are stored within constantly updated exemplar clouds in the JS user’s mental lexicon. These traces contain

- gradient phonetic detail along multiple continuous dimensions, both segmental and suprasegmental,

- abstract information about phonological categories, i.e., distinctive features, segments, and prosodic constituents, and