Abstract

This paper explores a novel case of contact-induced change due to micro-contact within Italy, where various Italo-Romance languages coexist (Standard Italian, Italiano Regionale ‘regional Italian’, and numerous local languages). Although morphosyntactic change due to micro-contact is probably widespread across Italy, it has received almost no attention in the literature. This case study involves the complementizer system of the local language Ferentinese (Southern Lazio), which underwent restructuring over a very brief period. I claim that this change is a case of downward reanalysis from Force to Fin within the split CP, triggered by the regression of the subjunctive and its subsequent replacement by a new complementation strategy. In turn, I argue that this change was the by-product of an increase in the number of complementizers in the language, from two to three, due to micro-contact between Ferentinese and Italiano Regionale. Crucially, the latter furnished a complementizer form (che) identical to one already present in the Ferentinese system, leading to reanalysis. Thus, in addition to reporting on a novel case of micro-contact in Italy, this paper illustrates one pathway to the genesis of a rare three-way complementizer system and sketches an initial typology of how related complementizer systems have changed in diachrony.

1. Introduction

This paper is a case study in a contact-induced change of a sort that is likely to be widespread throughout Italy, but to date has received almost no attention in the literature: namely, morphosyntactic change within a local Italo-Romance language induced by (micro-)contact with Italiano Regionale (IR) ‘regional Italian’. The case study under investigation here involves Ferentinese (Southern Lazio), a southern Italo-Romance language whose complementizer system has undergone reorganisation in a short time period (around 100 years). Based on corpus data from around 1900 onwards, I show that the finite C(omplementizer) system of Ferentinese comprises three distinct forms, namely che, ca, and cu (composing a three-way C-system), but that this system underwent changes within just this 100-year period. Specifically, I show that one of its complementizers, che, went from occupying a high position (Force) to a low position (Fin) within the CP domain during this period. I argue that this change is an instance of downward reanalysis, and reflects the innovation of a novel complementation strategy arising as a direct consequence of the narrowing distribution of the subjunctive mood in this variety.

The source of such change is the increase of complementizer forms in Ferentinese, which went from two to three as a result of language contact between Ferentinese and IR. Crucially, the latter has a C-form (che) which is not only homophonous with—but also structurally identical to—one of Early Ferentinese’s complementizers. The case of Ferentinese, therefore, exemplifies one pathway to the genesis of a rare three-complementizer system (ca vs. cu vs. che) from a previous two-way system (ca vs. cu) under contact.

Given that this change involves contact between two closely-related Italo-Romance languages, this is therefore a straightforward example of micro-contact. However, all prior cases of micro-contact documented in the literature so far have arisen as the result of immigration (e.g., of Italo-Romance speakers to another part of the Romance-speaking world; Andriani et al. 2022; D’Alessandro 2021; D’Alessandro et al. 2021; Frasson 2022; Frasson et al. 2021). The novelty of the present case study is that it reports for the first time an instance of micro-contact arising entirely as the result of domestic language policy (i.e., the imposition of Standard Italian on the local Italo-Romance languages). I present the details of this change before making the case that it is the result of micro-contact with IR. To the extent that our account of Ferentinese is correct, it should help lay the groundwork for further studies into the influence of IR on the morphosyntax of the countless other Italo-Romance languages with whom they are in constant and intense contact.

I also briefly consider the C-forms in Ferentinese that did not change, namely cu and ca. Retention of these C-forms is found in other southern Italo-Romance languages, even those with only two-way C-systems—a fact I take to be significant, as it sheds light on the typology of diachronic stability vs. instability within the Italo-Romance CP. This also represents additional evidence for a correlation between complementizer systems and the regression of subjunctive mood in Southern Italo-Romance.

This paper is organised as follows: in Section 2, I discuss previous literature and concepts related to the linguistic landscape in Italy (Section 2.1), micro-contact-induced change in Italy (Section 2.2), and child-driven language change (Section 2.3). In Section 3, I illustrate a prima facie case of micro-contact within Italy. In particular, I first describe the C-system of Ferentinese (Section 3.1), arguing that the change involving the reorganisation of its complementizer system is a case of downward reanalysis due to the regression of subjunctive mood and the development of a new embedding strategy (Section 3.2). I demonstrate that the genesis of the Ferentinese three-way complementizer system from a two-way complementizer system (and its restructuring) is a result of micro-contact within Italy between languages belonging to the same subfamily, namely Italo-Romance (Section 3.3). I briefly touch upon what did not change in Ferentinese C-system in Section 3.4. In Section 4, I discuss potential extensions to the Ferentinese case, namely two case studies of language change that could be ascribed to micro-contact in Southern Italy. In Section 5, I present the conclusions.

2. Background

2.1. The Linguistic Landscape in Italy

To talk about the effects of (micro-)contact within Italy, we first need to take a closer look at the language situation there. Broadly speaking, the majority of Italians living today have at least partial command of three grammars (or more): Standard Italian (SI); one of numerous local languages spoken at the town/community level (i dialetti); and, Italiano Regionale (IR) ‘regional Italian’. I briefly describe each of these (groups of) languages in turn, as all three will play a crucial role in the coming discussion.

2.1.1. Standard Italian (SI)

SI, the language that emerged from the standardisation of literary medieval Florentine, has been the official language of Italy since its unification in 1861 and is considered the most prestigious of the Italo-Romance languages. SI is taught in school, and mostly used in formal, primarily-written contexts. Despite its official status, however, SI is not actually the language Italians speak in their everyday lives (see below). Given that most Italians are not consistently exposed to SI until they are taught it in school, we might ask what its acquisitional status is. Berruto (2003) addresses this question directly, taking the strong position that native speakers of SI do not actually exist.1 Consequently, many scholars have wondered whether it is even possible to talk about an ‘Italian language’ at all (see Lepschy and Lepschy 1979, p. 7; Acquaviva 2000).

Nevertheless, the extensive exposure to SI that all Italians receive as part of their compulsory schooling has had a significant effect on the linguistic landscape of the country, in part by providing an ever-present source of possible contact-induced change, as we will see.

2.1.2. The Local Languages (i dialetti)

What I am calling here the ‘local languages’ (e.g., Neapolitan, Barese, Cepranese, Ariellese, etc.) are more commonly referred to as i dialetti, even within in the linguistics literature; this already-problematic term is then mistakenly translated to English as ‘Italian dialects’ (or even more misleadingly, ‘dialects of Italian’). In reality, these languages are sister languages of SI—not dialects of it—and are distinguished from each other by fine-grained isoglosses typically defined at the level of individual towns and local communities.2 These languages are used mostly by older generations among family members and some close friends. Incredibly, there are estimated to be roughly 7000/9000 distinct local languages within Italy—one for each town in the country (Vignuzzi 2005; see also Furlan 2014). Although these languages exhibit broad structural similarities with one another (as we would expect of closely-related languages), they also differ in minimal but significant ways—not only in terms of their syntax, but also their morphology, phonology, and lexis (see Ledgeway 2003b among many others).

For instance, while Standard Italian (like Romance more generally) is said to lack the phenomenon of dative shift (1), many of the local languages in the South of Italy allow it, subject to variation. For example, Neapolitan allows accusative indirect objects in ditransitives, i.e., canonical dative shift (2), as witnessed in clitic-doubling sentences. In standard ditransitives with dative-marked indirect objects as in (2a), the indirect object a Maria is doubled by the third person dative pronoun ce. This alternates with sentences such as (2b), in which the order of the direct and indirect object is transposed, with the indirect object now marked by Direct Object Marking (dom; homophonous with the dative marker), and, crucially, now doubled by an accusative clitic (which alternates with the phi-features of the indirect object it doubles, not shown here). However, Cosentino (3) allows them only in monotransitives (which Ledgeway 2003b, 110 takes to be a more constrained type of dative shift):

- (1)

- Standard Italian (adapted from Ledgeway 2003b, p. 110)

- Ho dato un libro a Maria.I-have given a book to Maria‘I gave a book to Maria.’

- *Ho dato Maria un libro.I-have given Maria a bookIntended: ‘I gave Maria a book.’

- (2)

- Neapolitan (adapted from Ledgeway 2003b, p. 110)

- ce rette nu libbro a Maria.her.dat I-gave a book to Maria‘I gave a book to Maria.’

- ’a rette a Maria nu libbro.her.acc I-gave dom Maria a book‘I gave Maria a book.’

- (3)

- Cosentino (adapted from Ledgeway 2003b, p. 111)

- ’u cucinu / sparu / telefunu / scrivu.him.acc I-cook I-shoot I-phone I-write‘I will cook for / shoot at/ ring / write to him.’

- cci / *u scrivu na littera.him.dat / him.acc I-write a letter‘I will write them a letter.’

Points of structural variation such as these, which serve to internally distinguish the full array of local languages in Italy, can be categorised and rendered as isoglosses. Pellegrini (1960, 1977) was the first linguist to classify these varieties into different groups according to their salient structural properties, and the essence of their classification is still used today (cf. Rohlfs 1966, fn. 1). As we can see in Pellegrini’s map in Figure 1, there are several sub-groups of Italo-Romance indicated with different colours. Simplifying, for the purposes of this paper it will suffice to highlight that the isogloss La Spezia-Rimini divides northern Italo-Romance from southern Italo-Romance (the yellow area from the set of pink and purple areas in Figure 1), the isogloss Roma-Ancona differentiates the central varieties (light pink area in Figure 1) from the upper southern varieties (dark pink area in Figure 1), and both the Taranto-Ostuni in Apulia and the Diamante-Cassano/Cetraro-Cirò Marina in Calabria demarcate the upper southern (the dark pink area in Figure 1) and extreme southern varieties (the purple area in Figure 1). Although these isoglosses define the major Italo-Romance subgroups, there is also non-trivial variation within these subgroups as well (left aside here); see Loporcaro (2009) for details.

Figure 1.

Map of local languages of Italy (Pellegrini 1977).6

Within the linguistic landscape of Italy, these local languages generally hold no prestige whatsoever, and are consistently stigmatised across the country (perhaps with the exception of some urban varieties). Indeed, many Italians consider speaking them to be ‘speaking badly’—for instance, it is common for parents and teachers to admonish pupils non parlare dialetto, parla bene ‘do not speak dialetto, speak properly’. This is surely one reason these languages are also highly endangered: in the last Italian census (ISTAT 2014), only 9% of Italians reported that they spoke a local language (mostly in the South and North-East of Italy).

2.1.3. Italiano Regionale (IR)

We turn now to Italiano Regionale (IR), which is perhaps the least studied Italo-Romance subgroup in spite of its ubiquity across the peninsula.3 IR is not a single language, but rather a collection of languages—specifically, contact varieties—that developed as a result of pressure from SI on the local languages (Berruto [1987] 2021, pp. 17, 58; Pellegrini 1960).4

In spite of the adjective regionale ‘regional’ in its name, IR’s isoglosses do not neatly align with the borders of specific administrative regions of Italy. For instance, what might be identified as a ‘Campanian’ variety of IR may also be the dominant IR spoken in bordering parts of Southern Lazio, for example. In fact, the most relevant factor for distinguishing varieties of IR is not geography per se, but rather the linguistic properties of the local languages that shape IR via contact. Thus, the isoglosses of the local languages inform the isoglosses of the IR varieties that they influence, yielding, e.g., southern regional Italian (cf. the southern Italo-Romance subgroup of local languages spoken in the upper South and extreme South of Italy in Figure 1), northern regional Italian (cf. the northern Italo-Romance subgroup of local languages spoken in the North of Italy in Figure 1), central regional Italian (cf. the central Italo-Romance subgroup of local languages spoken in the central part of Italy in Figure 1), etc.

Across Italy, IR is the primary means of everyday interaction (both informal and formal, e.g., at work, within the family, etc.)—it is what most Italians actually speak on a day-to-day basis. In general, IR is seen as more prestigious than the local languages, but less prestigious than SI. There are also differences in prestige within IR, in the sense that northern varieties of IR (e.g., as spoken in Lombardy) are currently perceived as more prestigious than southern varieties.5

Scholars cannot agree on when exactly the genesis of IR began, and whether it has ever finished. In broader terms, the main idea is that the genesis of IR originates from the spread of literary medieval Florentine (which then became SI) in the 15th and 16th centuries across Italy as a written language (accessible only to a very few literate people). It is only after the unification of Italy in 1861 that this spread becomes a large-scale phenomenon, when native speakers of different local languages started acquiring what became SI through a process of second language acquisition (see also Cortelazzo 1952, p. 11 for a similar point). The development of different IR varieties of stems from this, on the basis of the geographical distribution of the local languages spoken across Italy, while some scholars think that this is still in some respects an ongoing process (Berruto [1987] 2021, pp. 133–34), others argue that the process is now complete (Sobrero and Miglietta 2006, pp. 79–80; see Berruto [1987] 2021, pp. 130–39 and references therein for a detailed discussion).

Taken together, all of these languages—SI, the local languages, and IR—constitute the Italo-Romance family, of which ‘(Standard) Italian’ is only one small part. If we fail to take stock of this complex linguistic landscape, we risk ascribing to ‘Italian’ (=SI) features that actually belong to different languages, thereby obscuring the mechanisms of contact at work within this landscape.

2.2. Language Change Induced by (Micro-)Contact

As noted in Heine and Kuteva (2003, 2005), when two or more languages enter a situation of intense contact, one language (=the model language) can transfer linguistic material to another (=the replica language), namely, contact-induced language change can happen. In a generative perspective, Kroch (2001, p. 716) describes language contact as an “actuating force for syntactic change whose existence cannot be doubted”, namely an external factor that has the power of triggering an internal change in the grammar. Specifically, in a contact situation in which speakers of one language become familiar with another, structural changes such as reanalysis, syntactic borrowing, and imperfect learning can take place (Kroch 2001; Roberts 2007). In other words, the transfer of syntactic material induced by contact can be affected during first language acquisition or second language acquisition; see Kroch (2001). I return to this point below in Section 3.2.

Its complex linguistic situation makes Italy a multilingual country (Lepschy and Tosi 2002; Tosi 2001) where local languages, IR, and SI co-exist, and are often used in different contexts even within the same community (Berruto 1987; Loporcaro 2009). Extensive language contact is inevitable in such situations, giving rise to contact-induced changes in multiple different directions (with certain specific constraints).7 Specifically, these changes happen in three main directions within Italo-Romance: influence from SI on both IR and the local languages, influence from IR on the local languages, and influence from local languages on IR.

SI could in principle also undergo contact-induced change at a structural level due to pressure from IR and the local languages; however, this is a fairly unlikely scenario: SI is the most prestigious variety, and the only one to have undergone extensive language policy and planning (i.e., standardisation), unlike IR and the local languages.8 In general, contact-induced change is sensitive to the relative prestige of the languages involved (Heine and Kuteva 2005, p. 35). Thus, a more realistic situation is one in which the low-prestige, non-standardised languages (i.e., the local languages) undergo change under pressure from higher-prestige varieties (i.e., SI or IR). The example in (4) depicts the Italo-Romance languages along a cline of prestige (from high to low), with Standard Italian and Italiano Regionale holding far more prestige than any one of the local languages (with the gulf separating the former two from the latter indicated with ‘…’ in (4)). We therefore expect contact-induced changes to proceed from left-to-right along this cline, and not right-to-left.

- (4)

- Italo-Romance (macro-)languages by prestigeStandard Italian > Italiano Regionale > … > local languages

Since all these languages of Italy (barring those in note 7) belong to the same language sub-family—namely Italo-Romance—they can be considered minimally-differing varieties. As such, the three contact scenarios described above all qualify as micro-contact scenarios in the sense of D’Alessandro (2021; see also Andriani et al. 2022; Frasson 2022; Frasson et al. 2021). The difference here is that the scenarios under discussion in this paper exclusively involve an Italo-Romance language changing under contact with some other Italo-Romance language, rather than with some language from another branch of the Romance family.9 I return to this point further below.

2.3. Theoretical Assumptions on Language Change

Finally, before we turn to a detailed case study in (micro-)contact-induced change within Italy, we must first establish some background on the theory of language change more generally.

In the generative model, syntactic change is acquisitional: change occurs when the child acquires a grammar (i.e., a language system) which differs from that of their parents (Biberauer and Roberts 2017; Hale 1998; Lightfoot 1979, 1991; Lightfoot and Westergaard 2007; among many others). While acquiring a language, the child is presented with possible parametric choices, and those choices then feature in the newly acquired grammar. Following Lightfoot (1999, Biberauer and Roberts 2017, i.a.), parametric change involves a resetting of parameter values of the underlying grammar and comes from the ‘inside’, as the child reanalyses a lexical item or structure on the basis of the possible options within the parametric space (see Evers and Van Kampen 2008; Fodor 1998; Gibson and Wexler 1994; Lightfoot and Westergaard 2007, i.a.). Thus, in a generative perspective, language variation, language change, and language acquisition all converge.

If we further assume an emergentist approach to parametric variation (Biberauer and Roberts 2012b, 2015; Roberts 2019; Roberts and Holmberg 2010, i.a.), which takes individual parameters not to be part of Universal Grammar but rather emergent during the acquisition process (from the interaction of Chomsky’s 2005 Three Factors; Biberauer and Roberts 2012b; 2015; Roberts and Holmberg 2010, i.a.), then we end up with different granularities of language variation reflecting the hierarchical organisation of these emergent parameters and their parameter values. This is schematised in (5) below:

- (5)

- Types of parameters (Biberauer and Roberts 2015, p. 302; 2017, p. 57; Biberauer 2019, p. 22; Roberts 2019, pp. 75–76)For a given value vi of a parametrically variant feature F:

- Macroparameters: all heads of the relevant type share vi;

- Mesoparameters: all heads of a given naturally definable class, e.g., [+V], share vi;

- Microparameters: a small subclass of functional heads (e.g., modal auxiliaries) shows vi;

- Nanoparameters: one or more individual lexical items is/are specified for vi.

What differentiates the various types or ‘sizes’ of parameters in (5) is “the class of lexical entries in the functional lexicon which the presence/absence of a given functional feature F (or set of features) ranges over” (Roberts 2019, p. 76). In particular, macroparameters are concerned with the largest inventory of functional heads which can host a feature; mesoparameters involve a large class of heads; microparameters include small sets of functional heads; and nanoparameters constitute single lexical entries. These theoretical notions will play a crucial role in the analysis to come in Section 3.2.

With this background in place, we turn now to Ferentinese, a local language that underwent structural changes due to micro-contact with IR.

3. Micro-Contact in Italy: The Case of Ferentinese

The goal of this section is to illustrate and analyse a change that happened rapidly in the complementizer system of Ferentinese, and situate it within the broader typology of such changes within Italo-Romance.

I begin by describing the Ferentinese system in Section 3.1, leading to a description of the change in question in Section 3.2: namely, reanalysis of the complementizer che due to the development of a new complementation strategy resulting from the regression of embedded subjunctive environments. The cause of this change is a net increase in the number of finite complementizer forms in the language, from two forms to three. In other words, this change represents the genesis of a three-way complementizer system, an exceedingly rare feature in the Italo-Romance context. Since the state of affairs leading to this change was not unique to Ferentinese, but was in fact common within southern Italo-Romance, I conclude this section with some typological remarks: specifically, I compare the pathway of the change in Ferentinese (which resulted in a rare three-way system) with those of several of its close relatives (which resulted instead in two-way or even single complementizer systems), leading to a partial diachronic typology of finite complementizer systems in Italo-Romance.

3.1. The Complementizer System of Ferentinese (Colasanti 2017)

The local Italo-Romance languages spoken in Southern Italy display finite complementizer systems (C-systems) that can be descriptively characterised by the number of complementizer forms that compose them (Colasanti 2017, 2018a; Ledgeway 2003a, 2005, 2006; Rohlfs 1969, i.a.). The majority of these languages have one-way or two-way systems (i.e., one vs. two finite C-forms), but, rarely, three-way systems are found as well (Colasanti 2017; D’Alessandro and Ledgeway 2010; Ledgeway 2005). An example of a modern variety with a two-way system is given in (6), from Modern Secinarese:

- (6)

- Modern Secinarese (Manzini and Savoia 2005, I, p. 457)

- M annə ’dittə ka v’vè du’manə.to-me they-have said that he-comes tomorrow‘They said he’s coming tomorrow.’

- Vujjə kə v’vi.I-want that you-come‘I want you to come.’

Crucially, the choice of ka vs. kə is conditioned not by phonology, but by syntax (e.g., formal features encoding factivity, modality, etc.; see below). Over time, many Italo-Romance languages have undergone diachronic changes away from multiple-complementizer systems and toward single-complementizer systems, as in the case of Early vs. Modern Cosentino:

- (7)

- Early Cosentino (Ledgeway and Lombardi 2014, p. 40)

- Un pienzu ca vi canuscia buonu.Not I-think that to-you he-knows well‘I do not think he knows better.’

- Vulìa chi m’ accumpagnassa a ra casa.I-want.sbjv that it= he-accompany.sbjv to the house‘I wanted that he would accompany me home.’

- (8)

- Modern Cosentino (Ledgeway and Lombardi 2014, p. 40)

- A dittu ca sgarrati.He-has said that you-are-mistaken‘He has said that you are mistaken.’

- Idda vo ca ci fazzu na picca ’i spisa.She wants that to-her I-do a bit of shopping‘She wants that I do a bit of shopping.’

This diachronic trend toward simplification of C-systems via a reduction in the number of C-forms is no doubt part of the reason three-way C-systems are now rare. Nevertheless, some three-way C-systems can be found in Southern Italo-Romance.

Our point of departure is one such three-way C-system from Ferentinese, a local Italo-Romance language spoken in Ferentino (province of Frosinone, Southern Lazio). As argued in Colasanti (2017, 2018b), this C-system is a property of the present-day variety (henceforth Modern Ferentinese), but there is also historical evidence of it from an earlier stage of the language (henceforth Early Ferentinese).10 Like the rest of southern Italo-Romance, the distribution of complementizers in Ferentinese is sensitive to the embedding predicate type, the morphological mood of the embedded predicate (e.g., subjunctive, indicative), and the presence of topics/foci within the split CP (Rizzi 1997). In particular, the Early Ferentinese system includes three complementizers: ca (<quia), che (<quid), and cu (<quod). Throughout the discussion, I render che in small caps in order to generalise over orthographic variation in the source texts.11

First, consider how the distribution of the three C-forms in Ferentinese is influenced by the embedding predicate:12 regret-verbs (sacci ‘I know’) select the complementizer ca (9), say-verbs (dici ‘you say’) select che (10) or ca (11), and want-verbs (uria ‘I wish’) select cu (12).

- (9)

- Early Ferentinese (Bianchi 1991a, p. 120 apud Colasanti 2017)Sacci ca tu nun si ’na bbona pezza.I-know that you not are a good patch‘I know that you’re not a good person.’

- (10)

- Early Ferentinese (Bianchi 1974, p. 22 apud Colasanti 2017)Po’ dici che ci batte ’n petto.Then you-say that to-us it-beats in chest‘Then you say that it beats in our chest.’

- (11)

- Early Ferentinese (Prosperi and Bianchi [1942] 1980, p. 38)Dici ca la so ffatta penitènza.you-say that it= I-am done penitence‘You say that I have repented.’

- (12)

- Early Ferentinese (Angelisanti 1983, p. 9 apud Colasanti 2017)Uria cu nun fussi mai unuta.I-want.cond that not you-be.sbjv never come‘I wish that you would have never come.’

A closer look at the data in (9), (10), and (12) reveals that complementizer distribution in Early Ferentinese is also sensitive to the morphological mood (i.e., indicative vs. subjunctive) of the embedded clause: indicative complements are headed by che (10) or ca ((9), (11)), and subjunctive complements are headed by cu (12).

Like Early Ferentinese, Modern Ferentinese also displays a three-way complementizer system (ca (<quia), che (<quid), and cu (<quod)) whose distribution is influenced by the selecting predicate type, morphological mood, and the activation of the split CP. However, the details of the Modern system differ from those of Early system: specifically, say/regret-verbs now pattern alike in selecting only the complementizer ca (13a), whereas want-verbs can now select either the complementizer che (13b) or cu (13c). Moreover, the distribution of the complementizers again seems to be sensitive to the embedded morphological mood: say/regret-verbs select indicative complements (13a), and want-verbs can either select (irrealis) indicative (13b) or subjunctive (13c) complements.

- (13)

- Modern Ferentinese (Colasanti 2017, p. 75)

- Peppu diʃi/credi ca Angilu pò unì a casa.Peter says/believes that Angelo can come at home‘Peter says/believes that Angelo can come home.’

- Maria uléssu chə Peppu bèuə/*bèuessə sempre.Mary want.sbjv that Peter drink.ind/sbjv always‘Mary wishes that Peter would always drink.’

- Giuagni uléssu cu ie n ci issi alla festa.John want.sbjv that I not there I-go.sbjv to-the party‘John wishes that I would not go to the party.’

This is summarised in Table 1 below, where the grey cells highlight the changes involving the complementizer che.13

Table 1.

Complementizer distribution by matrix predicate type and morphological mood.

Complementizer systems in Italo-Romance and beyond have been profitably modelled using a richly articulated structure of the CP (a “split CP”: Rizzi 1997; Rizzi and Bocci 2017; (14)):

- (14)

- Force Top* Int Top* Foc Top* Mod Top* Qemb Fin [IP …](adapted from Rizzi and Bocci 2017, p. 9)

Evidence for the articulated left-peripheral structure in (14) can be found in several Italo-Romance varieties (Ledgeway 2003a et seq., i.a.), including Early Ferentinese. For instance, whereas the complementizers ca and che precede the dislocated (contrastive) topics pu Fiorenza ‘for Florence’ and biastéma fiacca ‘soft swear’ in (15) and (16), the complementizer che follows (exceptionally) the focalised element èccu ‘here’ in (17), suggesting that it is in Fin.14

- (15)

- Early Ferentinese (Prosperi and Bianchi [1942] 1980, p. 53)’Na vota su diceva caForce pu Fiorenza stevenu tuttu quantu cioccu.one time one said that for Florence they-stand all as drunk‘Once upon a time, it was said that they were all drunk because of Florence.’

- (16)

- Early Ferentinese (Bianchi 1991a, p. 41)Gli frintinési, si vóto dici cheForce biastéma fiacca, è puThe inhabitants-of-Ferentino if the-vow says that swear soft is for’ssi santi du ‘ss’ àtri paesi…those saints of these other towns‘As for the inhabitants of Ferentino, if the vow says that little swears are for the saints of nearby towns…’

- (17)

- Early Ferentinese (Prosperi and Bianchi [1942] 1980, p. 37)J’e vulessu èccu cheFin tu dicu radduvuntà pu ’nu minutu sulu uttru.I want.sbjv here that you say to-become-again for one minute only child‘I wish that, for just a minute, you say I could be a child again here.’

In general, say-verbs and regret-verbs in southern Italo-Romance can only select complementizers that precede (never follow) topics/foci, whereas want-verbs can only select complementizers that follow (never precede) topics/foci (Colasanti 2017, 2018a; Ledgeway 2003a, 2005, 2006; Rizzi 1997, i.a.). The data above show that this is corroborated by Early Ferentinese as well. The split-CP structure consistent with the distribution of C-forms in Early Ferentinese is schematised in (18).

- (18)

- Early Ferentinese: distribution of C-forms within the Split CP[CP Force (che/ca) [Top [Foc [Fin (cu) [IP …]]]]]

As we can see in (19), like Early Ferentinese, the distribution of C-forms is also sensitive to the split-CP structure in Modern Ferentinese:

- (19)

- Modern Ferentinese (adapted from Colasanti 2017, p. 77)

- Peppu diʃi/credi caForce Angilu addumanu *caFin pò unì aPeter says/believes that Angelo tomorrow that can to-come atcasa.home‘Peter says/believes that Angelo can come home tomorrow.’

- Maria uléssu la figlia allocu chəFin n’ ci ua più.Mary want.sbjv the daughter there that not to-it she-goes anymore‘Mary wishes that her daughter would not go there anymore.’

- Giuagni uléssu Maria cuFin n’ ci issi alla festa.John want.sbjv Mary that not to-it he-go.sbjv to-the party‘John wishes that Maria would not go to the party.’

These examples show that the complementizer ca occupies the higher position Force, as it can only precede (but never follow) topics/foci (19a), whereas the complementizers che and cu can both occupy the lower position Fin, since these can only follow (but never precede) topics/foci, respectively, ((19b), (19c)). The distribution of C-forms in Modern Ferentinese is summarised below, presented alongside the picture of the Early Ferentinese split CP given above in (18) above:

- (20)

- The distribution of Ferentinese C-forms within the Split CP

- Early Ferentinese: [CP Force (che/ca) [Top [Foc [Fin (cu) [IP …]]]]]

- Mod. Ferentinese: [CP Force (ca) [Top [Foc [Fin (che/cu) [IP …]]]]]

To account for the distribution of these C-forms, I follow Colasanti’s (2018b, 2018c) feature-based analysis of the C-systems in several other Southern Italo-Romance languages. Specifically, I assume the Ferentinese C-system is characterised by a set of features—namely, [realis], [factive], and [irrealis]—whose association with specific C-forms undergoes a change over time. In the brief transition from Early to Modern Ferentinese, we witness the reorganisation of its complementizer system summarised in Table 2. Specifically, in this short period, the complementizer che went from occupying a higher Force[realis] position to a lower Fin[irrealis] position, where it now introduces strictly indicative complements (vs. subjunctive). By contrast, the distribution of the complementizer forms cu and ca did not change (for reasons I return to shortly in Section 3.4).

Table 2.

Complementizer distribution in Early and Modern Ferentinese.

In other words, this change in position of che within the split CP crucially coincided with the innovation of a novel complementation strategy: namely, want-verbs were suddenly able to take indicative complements headed by che (alongside subjunctive complements headed by cu), where previously such verbs exclusively took subjunctive complements. This is illustrated by the structure below:

- (21)

- New complementation strategy in Ferentinese[… want [CP cheFin[irrealis] … Vind]]

I propose an account of this change in the next subsection.

3.2. From Early to Modern Ferentinese: Downward Reanalysis of che

The Ferentinese-internal change described above involving che is an instance of downward reanalysis (Munaro 2016; Quinn 2009) with concomitant feature reassignment: che went from occupying the higher position Force to the lower position Fin, while at the same time swapping its [realis] feature for an [irrealis] feature.

- (22)

- Downward reanalysis of che from Early to Modern FerentinesecheForce[realis] > cheFin[irrealis]

I propose that this downward reanalysis was initiated by another change taking place in Ferentinese (and in Italo-Romance more broadly): namely, the partial erosion of the -ss- imperfect subjunctive. In brief, want-verbs went from only taking subjunctive complements, to taking either subjunctive or indicative complements. These innovative indicative complements required a complementizer—this, I argue, is what led to the downward reanalysis of che. The result is the want-verb + che + ind complementation strategy we witness in Modern Ferentinese. I claim that this change occurred because of morphological opacity/obsolescence in the input for the child acquiring Early Ferentinese—opacity whose resolution led the acquirer to posit the reorganised C-system described above.

Downward reanalysis of this sort has some precedent in the literature. Munaro (2016) discusses a different case of downward reanalysis within the Italo-Romance CP involving the complementizer che undergoing a change from occupying the (low) Topic position to the Fin position below it. Munaro adopts previous diachronic treatments of complementizer doubling in Early Italo-Romance (see Ledgeway 2005; Vincent 2006), which claim that if-clauses (and other clausal adjuncts) frequently fill the position between two complementizers (Comp1 and Comp2), the higher one in Force (Comp1) and the lower one in Topic (Comp2). The Early Italo-Romance CP structure assumed by Munaro—illustrated below in (23)—is claimed to be lost in contemporary Italo-Romance varieties, where Comp 2 now lexicalises the lower position Fin (24), after undergoing downward reanalysis because of morphological ambiguity.

- (23)

- Early Italo-Romance CP structure (adapted from Munaro 2016, p. 218)Main clause [ForceP [Force Comp1] [TopicP adverbial clause [Topic Comp2] … [FinP [Fin]]]]

- (24)

- Contemporary Italo-Romance CP structure (adapted from Munaro 2016, p. 218)Main clause [ForceP [Force Comp1] [TopicP adverbial clause [Topic] … [FinP [Fin Comp2]]]]

It is well-known that syntactic change can be triggered by obsolescent morphological material in the input, which is difficult for the child to acquire (Biberauer and Roberts 2017; Hale 1998; Lightfoot 1979, 1991; Lightfoot and Westergaard 2007; Roberts 1993; Roberts and Roussou 2003, Willis 2016; Roberts 2007, ch. 3; among many others). When the child is exposed to ambiguous input, there are two logical scenarios: the child simply fails to acquire the ambiguous item/structure; or, the child resolves the problem by positing an unambiguous representation of the item/structure, thereby departing from the triggering input (thus effecting language change).

Applied to Ferentinese, the latter scenario would mean that the input of che was already ambiguous in Early Ferentinese. Indeed, there is evidence of such ambiguity in our corpus: one of the texts first published around 1942 displays an instance of the complementizer che preceded by the focalised element èccu ‘here’ (in the repeated example (17)), suggesting that this C-form occupies Fin and not Force. This contradicts what we saw earlier in (16) (repeated below): there, in the same period, we find che followed by dislocated left-peripheral constituents, suggesting it lexicalises Force in such examples:

- (17)

- Early Ferentinese (Prosperi and Bianchi [1942] 1980, p. 37)J’e vulessu èccu cheFin tu dicu radduvuntà pu ’nu minutu sulu uttru.I want.sbjv here that you say to-become-again for one minute only child‘I wish that, for just a minute, you say I could be a child again here.’

- (16)

- Early Ferentinese (Bianchi 1991a, p. 41)Gli frintinési, si vóto dici cheForce biastéma fiacca, è puThe inhabitants-of-Ferentino if the-vow says that swear soft is for’ssi santi du ‘ss’ àtri paesi…those saints of these other towns‘As for the inhabitants of Ferentino, if the vow says that little swears are for the saints of nearby towns…’

This is but one example in the whole corpus of Early Ferentinese, but indicates that che was already undergoing a change, which we now witness today in Modern Ferentinese (25):

- (25)

- Modern Ferentinese (adapted from Colasanti 2017, p. 77)Maria uléssu la figlia allocu chəFin n’ ci uà più.Mary want.sbjv the daughter there that not to-it she-goes anymore‘Mary wishes that her daughter would not go there anymore.’

Since the example in (17) is the only one in the whole corpus, is unlikely that this was the usual distribution of che at the time. Concretely, within the same period, we see both (i) the usual distribution of che in Force, and (ii) the occasional distribution of che in Fin. To the extent that these two conflicting orders in the written record were also reflected in the input of the Early Ferentinese acquirer, then the system was crucially ambiguous: the child was exposed to a single phonological surface form (che) which nevertheless lexicalises two featurally-distinct positions within the split CP—positions which would only be disambiguated in the presence of a left-dislocated constituent. The acquisition of che therefore posed a challenge for the Early Ferentinese child: to acquire this form at all, its ambiguity had to be resolved, leading to the exceptional pattern in Early Ferentinese (i.e., che in Fin) becoming the norm in Modern Ferentinese—a straightforward case of downward reanalysis.

Importantly, the downward reanalysis of che from Force to Fin coincided with the innovation of a novel complementation strategy in Early Ferentinese, namely want-verb+che+ind (cf. (25) vs. (17); see the discussion above). As mentioned above, this novel complementation strategy arose in Ferentinese—like many other Southern Italo-Romance languages—when want-verbs stopped taking exclusively subjunctive complements (marked with -ss-), and started allowing indicative complements as well (Rohlfs 1969, p. 301; see also Ledgeway 2009b, §12.2.3.3; Colasanti 2018c, pp. 29–32). This is shown in the contrast between the repeated Modern Ferentinese examples (19b) and (19c): in the same period, the want-verb can embed either an indicative complement headed by cheFin (19b) or a subjunctive complement headed by cuFin (19c), both of which are irrealis:

- (19)

- Modern Ferentinese (adapted from Colasanti 2017, p. 77)

- Peppu diʃi/credi caForce Angilu addumanu *caFin pò unì aPeter says/believes that Angelo tomorrow that can to-come atcasa.home‘Peter says/believes that Angelo can come home tomorrow.’

- Maria uléssu la figlia allocu chəFin n’ ci ua più.Mary want.sbjv the daughter there that not to-it she-goes anymore‘Mary wishes that her daughter would not go there anymore.’

- Giuagni uléssu Maria cuFin n’ ci issi alla festa.John want.sbjv Mary that not to-it he-go.sbjv to-the party‘John wishes that Maria would not go to the party.’

The co-occurrence of C-system changes alongside the recession of subjunctive mood has caught the attention of several scholars of Italo-Romance; however, the literature has long held that this co-occurrence is merely coincidental (Ledgeway 2009b, pp. 523–24; but cf. Rohlfs 1969, p. 190; i.a.). By contrast, Colasanti (2018c, pp. 29–32) argues that the alternation between the subjunctive form and the present indicative in irrealis complements is not coincidental for at least Southern Lazio varieties. The main evidence is that the distribution of irrealis complements selected by want-verbs with indicative vs. subjunctive is related to the presence of a specific complementizer form—precisely what we see in the Ferentinese data above.

Based on this correlation, I claim that the partial loss of subjunctive morphology and the substitution with indicative forms creates opacity in the alternation between indicative-subjunctive in embedded contexts. I argue below that this opacity is resolved in some varieties—e.g., Ferentinese—by specialisation of one complementizer form, so that it is only found introducing these newly-innovated indicative complements.

Chronologically speaking, the reduction in the use of subjunctive in Southern Italo-Romance seems to occur quite early on (see Rati 2016). For instance, Ledgeway (2009b, p. 522) reports that in Neapolitan the subjunctive appears to be reduced from the beginning of the 18th century. It is therefore clear that the regression of the subjunctive in Southern Italo-Romance precedes the restructuring of the Ferentinese C-system by some time, as the retraction of subjunctive in neighbouring varieties evidently occurred between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century (Ledgeway 2009b, p. 523). I propose that the downward reanalysis of che in Ferentinese described above is a side-effect of this narrowing of the subjunctive—or, more to the point, the rise of the novel indicative complementation strategy under want-verbs that occurred as a result.15

Indeed, as we already saw above (see Table 2), the C-system of Early Ferentinese was characterised by two distinct C-forms with the exact same featural makeup in realis contexts, both lexicalising Force: namely, ca and che. In short, Early Ferentinese had a pair of redundant Force complementizers apparently in free variation with one another in realis contexts; and, at the same time, it also had an emerging complementation strategy in need of a C-form to introduce it (i.e., indicative complements of want-verbs).

Thus, the restructuring of the Ferentinese C-system appears to be directly related to the shrinking distribution of the subjunctive and its substitution by the indicative in irrealis contexts.

We are therefore faced with a typical example of the Regress Problem (Roberts 2007, pp. 123–32; see also Kroch 2001, pp. 699–700): if the change-inducing property (i.e., cheFin+ind) was already present in the corpus of Early Ferentinese, then why did not the change arise in that grammar, as well? Put differently: why was the ambiguity tolerated and perpetuated by Early Ferentinese acquirers, but reanalysed by Modern Ferentinese acquirers? Kroch (2001, pp. 699–700) discusses two general solutions to the Regress Problem; I discuss each in turn, as applied to Ferentinese. The first possible solution to this problem would be that Early Ferentinese’s corpus changed so quickly that Modern Ferentinese’s grammar was more rapidly abduced from it as a result (vs Early Ferentinese’s grammar). This seems plausible, given how abrupt and rapid the change was from Early to Modern Ferentinese. However, the second possible solution to the Regress Problem put forward by Kroch is that an external factor triggered the change: namely, language contact. This is the most likely explanation, given that local languages such as Ferentinese have been in intense contact with SI (and IR) for more than 150 years (see Section 2.1).

Since the co-occurrence of changing C-systems and the regression of subjunctive is common within southern Italo-Romance, I compare the change that happened in Ferentinese with other neighbouring languages in order to establish a partial typology of C-reorganisation strategies across southern Italo-Romance. Since the Ferentinese pathway turns out to be unique within Italo-Romance, there are reasons to believe that its three-way system is a particularly rare result of micro-contact with IR. This is the topic of the next subsection.

The presence of multiple complementizer systems and the regression of subjunctive in irrealis contexts are two widespread features of Southern Italo-Romance. Hence, we expect neighbouring local languages spoken within the South to have undergone a similar restructuring of their C-systems. This prediction is confirmed, although the nature of these changes differ from language to language. For instance, upper Southern Italo-Romance languages such as Neapolitan and Cosentino underwent a reduction of their C-systems from two C-forms (chi/chə) to just one (ca), thereby becoming one-way C-systems (for Cosentino, see Ledgeway 2009a; for Neapolitan, see: Ledgeway 2009b, §24.1.3). Other upper Southern Italo-Romance languages such as Cepranese maintained two C-forms (chə, ca in Fin) which can both introduce indicative complements. However, nowadays only one of these C-forms (chə) can introduce subjunctive complements selected by want-verbs (see Colasanti 2018a). Elsewhere, the three-way complementizer system found in Early Salentino (cu vs. che vs. ca) was reduced to a two-way system in Modern Salentino (cu vs. ca; see Calabrese 1993, p. 36; Ledgeway 2005, pp. 364–70).

These various diachronic pathways—each arising in response to the two factors described above (i.e., narrowing of the subjunctive paired with the innovation of a novel indicative environment under want-verbs)—are summarised in (26):

- (26)

- Typology of C-reorganisation strategies in Southern Italo-RomanceNeapolitan/Cosentino: two-way (chə/chi vs ca) > one-way (ca)Cepranese: two-way (chə vs ca) > two-way (chə vs ca)Salentino: three-way (cu vs che vs ca) > two-way (cu vs ca)Ferentinese: three-way (cu vs che vs ca) > three-way (cu vs che vs ca)

From the typology above we can notice that Ferentinese is the only language that maintained a three-way complementizer system across Southern Italo-Romance. (I will discuss below how Ferentinese started out as a two-way system before becoming a three-way system.) Indeed, three-complementizer systems are not only rare, but are in fact only documented in extreme Southern Italo-Romance (i.e., Early Salentino). In other words, aside from the Ferentinese case described here, they are not found in upper Southern Italo-Romance. Moreover, none of the languages above adopts the Ferentinese C-reorganisation strategy; presumably, this is because none went through a stage with two redundant C-forms in Force, such that one could be reanalysed by the acquirer as only introducing the novel complementation strategy arising as a result of the narrowing subjunctive. This makes Ferentinese C-reorganisation a typologically isolated case across Southern Italo-Romance, perhaps explaining the overall rarity of three-way C-systems in this context.

3.3. From Pre-Early to Early Ferentinese: The Genesis of a Three-Way C-System

Pushing further, there are independent reasons to believe that the Early Ferentinese three-way C-system was itself the product of language contact between IR and an even earlier diachronic stage of Ferentinese. I refer to this earlier stage as Pre-Early Ferentinese (ca. 19th century), and describe the genesis of its three-way C-system below.

Crucially, the relevant variety of IR has a C-form realised as che which is homophonous with, and structurally identical to, the che found in Early Ferentinese (but structurally distinct from the che of Modern Ferentinese). Given that historical varieties of neighbouring languages all lack an equivalent che form, we can take this form to be the product of borrowing under micro-contact with IR. In turn, this would mean that Pre-Early Ferentinese was in possession of a two-way C-system (cu vs. ca), gaining this third C-form due to micro-contact (yielding cu vs. ca vs. che); see Table 3.16

Table 3.

Complementizer forms in IR, Pre-Early, Early, and Modern Ferentinese.

As mentioned above, the fact that neighbouring varieties historically show robust two-way systems across the board provides a strong argument for the existence of the Pre-Early Ferentinese stage I am proposing. For instance, historical records of Neapolitan dating back to ca. 1200 show that it had a two-way complementizer system right up to the mid-19th century (Ledgeway 2009b, pp. 881–82). As a nearby sister language of Ferentinese (with a significantly older written record), 19th century Neapolitan provides our best approximation of what 19th century (Pre-Early) Ferentiese must have looked like, in turn furnishing an argument for a two-way C-system in the latter language.

The above arguments for a two-way C-system in Pre-Early Ferentinese are further supported by remarks in a Ferentinese dictionary first published in 1982 by Bianchi (1982). In this work, the complementizer forms ca and cu can be found, but the complementizer che is conspicuously missing. In its absence, Bianchi is explicit, stating in the dictionary’s prologue that he was trying to document the ‘original’ Ferentinese language as spoken by their grandmother. Interestingly, the author observes that their Ferentinese underwent substantial changes with respect to the variety spoken by their grandmother due to contact with IR (Bianchi 1982, Preface). Given the scope and rapidity of the changes that Ferentinese underwent during this period, it is unsurprising that language experts such as Bianchi were metalinguistically aware that their own variety of Ferentinese was different from the one spoken by their grandparents’ generation. Concretely, then, we can say that Bianchi excluded che from their dictionary because he recognised it as an innovative form compared to their grandmother’s generation, which, based on the preceding discussion, we can conclude was borrowed under contact with IR. This represents further indirect evidence supporting the claim that Pre-Early Ferentinese had a two-way C-system rather than a three-way system, and that che was borrowed from IR.

Taking stock, the genesis of the Ferentinese three-way C-system is an example of micro-contact (in the sense of D’Alessandro 2021, et seq.) within Italy, arising as a direct result of language policy leading to the imposition of SI on existing Italo-Romance language communities (and the subsequent emergence of IR as a result, itself an example of micro-contact not explored in depth here). Southern Lazio is therefore no exception to the linguistic situation outlined above in Section 2.1: the Ferentinese language, like thousands of other Italo-Romance local languages, has now been under extensive contact-induced pressure from IR for more than a century (see discussion in Section 2).

The contact-induced change described here seems to be a case of imperfect learning in the sense of Kroch (2001, pp. 716–17; see also Roberts 2007, §5.2.1): the transfer of the complementizer che into Early Ferentinese happened via L2 contact, a typical scenario in which imperfect learning arises. In particular, as L2 learners of IR, Pre-Early Ferentinese speakers acquired the language imperfectly, leading to the appearance of IR features in the input of Pre-Early Ferentinese speakers. This means that they likely passed certain IR features on to their children acquiring Ferentinese, leading to language change from one generation to the next.

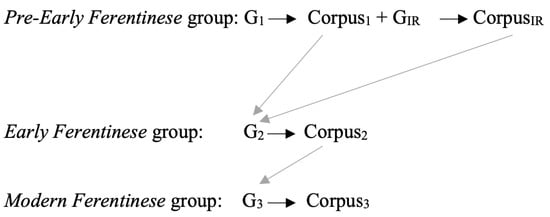

Following Roberts (2007, §5.2.1), we can think of such imperfect learning as a case of indirect contact. Specifically, the native speakers of Pre-Early Ferentinese started using a second language (IR) and their input contained a significant quantity of tokens of che due to their imperfect (L2) learning of IR. It is only with the Early Ferentinese generation that che becomes incorporated as part of the Ferentinese grammar, which then transformed the preceding generation’s two-way C-system into an innovative three-way system. This is illustrated in Figure 2, adapted from Roberts (2007, p. 391), in which each G(rammar) generates a Corpus that serves as the input for the next generation of acquirers:

Figure 2.

Indirect micro-contact-induced change in Ferentinese.

As we can see in Figure 2, the Pre-Early Ferentinese group comprised native speakers of Pre-Early Ferentiense (G1), which were L2 learners of GIR. The Early Ferentinese group’s input came from both Corpus1 (the output of G1 from Pre-Early Ferentinese) and CorpusIR (the output of GIR).

Although the linguistic landscape of Italy makes micro-contact inevitable (see Section 2), we still need to explain what differentiates micro-contact between IR and Pre-Early Ferentinese from a simple case of contact. Several arguments support the micro-contact hypothesis here. The first concerns the structural homogeneity found between Ferentinese and IR. The group of Pre-Early Ferentinese native speakers (G1), which were L2 learners of IR, must have been exposed to a high degree of homogeneous structures similar to both Ferentinese and IR. This scenario would make their output easily acquirable for the following generation of Early Ferentinese child-acquirers. Since the two languages involved in this contact scenario are minimally different from each other, Early Ferentinese acquirers likely could not fully differentiate the output of G1’s Pre-Ferentinese grammar from the output of GIR’s imperfectly-learned (L2) grammar. In those terms, the Ferentinese case qualifies as a case of micro-contact: this kind of change was only possible because of the extensive homogeneity between these Italo-Romance languages. The second argument is the short span of time (ca. 160 years, but likely less) required for this transfer of che from Early Ferentinese to its reanalysed state in Modern Ferentinese. As highlighted by Roberts (2007, p. 398), rapid language change suggests indirect contact-induced change, which—coupled with the fact that the languages in contact are minimally different—makes the case of Ferentinese the perfect example of micro-contact within Italy. This also seems compatible with the various case studies reported in D’Alessandro 2021, et seq.) involving changes to heritage grammars induced by micro-contact, which similarly arose in relatively short periods of time.

Before concluding this section, I now briefly touch upon aspects of the Ferentinese C-system that did not change, and how this might inform a microparametric analysis of the facts.

3.4. What Has Not Changed in Ferentinese?

Biberauer and Roberts (2012a) note that, in a parametric approach to diachronic syntax, we must examine not only what changes, but also what does not change. In the restructuring of the Ferentinese C-system, neither the distribution of cu (cuFin[irrealis] > cuFin[irrealis]), nor the distribution of ca (caForce[realis, factive] > caForce[realis, factive]) underwent change. Evidently, Ferentinese is not alone in preserving these components of its C-system. That is, we generally find a C-form lexicalising Force[realis, factive] and a C-form lexicalising Fin[irrealis] in southern Italo-Romance, suggesting these parts of the C-system are relatively resistant to change. This is exemplified below in Lenolano:

- (27)

- Lenolano (Colasanti 2018c, pp. 17, 59)

- I richə (*aumànə) ca aumànə Mariə uè.I say tomorrow that tomorrow Mario comes‘I say that Mario comes tomorrow.’

- A Mariə ce rəʃpiàcə (*mo) ca mo Giuanna stà a piagnə.to Mario to-him regrets now that now Giovanna stands to cry‘Mario regrets that Giovanna is crying now.’

- Maria vò aumànə chə (*aumànə) venéssə Giannə (noMaria wants tomorrow that tomorrow come.sbjv Giannə notdoppəumànə).the.day.after.tomorrow‘Maria wishes that Gianni would come tomorrow (not the day after tomorrow).’

- [CP Force[realis, factive] (ca) [Top [Foc [Fin[irrealis] (chə) [IP …]]]]]

From a parametric perspective, we might take this to indicate that the microparameter settings associated with these parts of the C-system are apparently rather stable. More generally, this is evidence that not all microparameters are created equal—some are more resistant to change than others (Biberauer and Roberts 2012a). For instance, it seems that realis and factive complementizers are usually more susceptible to change. As Colasanti (2018c, chp. 3) argues at length for Southern Italo-Romance (based on the scarcity of complementizers found exclusively in factive contexts and the frequency of complementizers appearing in factive/realis contexts in Italo-Romance, left aside here), the loss of the factive complementizer seems to be the trigger for original three-way (for example in Salentino: Ledgeway 2005).

Assuming the emergentist approach to parametric variation and the taxonomy of parameters discussed in Section 2.3, I suggest that the irrealis complementizer’s resistance to change is the effect of a parameter cluster: i.e., the proposal from Biberauer and Roberts (2017, 2015); Roberts (2019), and others that certain parameters are linked to other parameters, such that a change in one of them within the cluster implicates a change in the others. By the same rationale, the absence of certain parameter changes can result in stability within the parameter cluster. In Ferentinese, cuFin[irrealis] seems to be linked to the presence of the subjunctive in the embedded complement; however, as discussed in the previous subsection, the indicative vs. subjunctive opposition is eroding in southern Italo-Romance, with the latter giving way to the former (see also Colasanti 2018c, chp. 2). Perhaps, then, we have not yet seen any change in cuFin[irrealis] because this parameter is linked to the subjunctive mood parameter, which is part of the same parameter cluster within the I-domain. For instance, the loss of morphological subjunctive is taken to be the cause of changes within the C-domain in Modern Greek and in extreme Southern Italo-Romance varieties (see relevant case studies by Roberts and Roussou 2003, chp. 3). In upper Southern Italo-Romance, the mood of embedded complement clauses influences the distribution of their complementizers, as we saw above in Section 3.1. Thus, in Ferentinese, the partial but incomplete loss of subjunctive complementation might be the reason the complementizer cuFin[irrealis] is maintained, such that it exclusively introduces subjunctive complements.

While speculative, this proposal unifies various diachronic properties of these languages, and provides some additional evidence for the regression of subjunctive as relevant to the change in the Ferentinese C-system described in Section 3.2.

3.5. Summary

To summarise, Early Ferentinese had a three-way C-system that underwent rapid restructuring over a span of roughly 100 years, leading to the reorganised three-way system we see today in Modern Ferentinese. This abrupt change involved a case of downward reanalysis from Force to Fin, in the sense of Munaro (2016). The evidence shows that this reanalysis is directly correlated with the regression of subjunctive mood under want-verbs, and the concomitant innovation of a new complementation strategy in the same environment.

However, this restructuring is also the indirect result of a change that took place in an earlier stage of the language: namely, the change from the two-way C-system of Pre-Early Ferentinese to the three-way system of Early Ferentinese. I argue that this change, characterised by the addition of che into the system, is the direct result of micro-contact between Ferentinese and IR.

Interestingly, though, these changes to the Ferentinese C-system were rather limited: some components of this system remained stable throughout this period. Specifically, the C-forms cu and ca each retained their original distribution all along; and, in so doing, they behaved much like their counterparts in many southern Italo-Romance languages under diachrony. This suggests that C-systems are resistant to changing their C-forms realising the feature [irrealis] in Fin and the [realis, factive] in Force, a fact which is best understood in terms of microparametric stability (itself the result of parameter clustering).

This concludes the discussion of Ferentinese. In what remains of the paper, I provide arguments for the plausibility of the above proposals, in the form of two additional case studies in micro-contact.

4. Extensions: Two Further Case Studies of Micro-contact within Italy

In this section, I review and discuss two case studies on language change which, like the Ferentinese case, are attributable to micro-contact within Italy. The first of these (Section 4.1) involves the local language Cegliese, which has innovated a non-finite subordination strategy due to extensive micro-contact with IR of Apulia. The second case study (Section 4.2) goes in the opposite direction: it involves IR of Sicily, which has seemingly borrowed Differential Object Marking from the local languages spoken in Sicily, while both of these case studies are taken from the existing literature, neither has previously been framed in terms of micro-contact until now. Together with the case of Ferentinese described in depth above, these brief case studies allow us to begin building a picture of the directionality and effects of micro-contact within Italy.

4.1. Case Study 1: Cegliese under Pressure from IR of Apulia

The extent of language contact within Italy is quite difficult to assess and has hence often been overlooked, though there are some exceptions. For instance, Tempesta (1984) reports an example involving the C-system of Cegliese, a local language spoken in Ceglie Messapica (Salento, Apulia), changing under contact with the Apulian variety of IR.17 Like SI, IR of Apulia exhibits a non-finite subordination pattern involving a (prepositional) complementizer (de/pe/a) alongside a non-finite verbal form, as in (28a). In the same context, IR of Apulia cannot use a finite complementation strategy (che + indicative), again like SI (28b):

- (28)

- IR of Apulia (adapted from Tempesta 1984, p. 114)

- Ho mandato mio fratello a chiamar-ti. non-finite complementationI-have sent my brother a to-call-you‘I have sent my brother to call you.’

- *Ho mandato mio fratello che ti chiama. finite complementationI-have sent my brother che to-you he-calls‘I have sent my brother to call you.’(Lit. ‘I have sent my brother that he calls you.’)

This is essentially the opposite of the pattern found in the variety of Cegliese spoken by the oldest generation (henceforth, G1) in Tempesta’s (1984) study. In such contexts, speakers from the G1 generation reject the Cegliese equivalent of the a + infinitive strategy seen above in (28a), and instead use a ku + indicative strategy akin to (28b). Strikingly, however, this preference changes rapidly across the three generations 18 sampled in the study, clearly demonstrating a change in progress. This is illustrated in the examples below (where G1 are the oldest speakers, and G3 are the youngest, with G2 in between):

- (29)

- Cegliese complementation across three generations (adapted from Tempesta 1984, p. 114)

- Agghə mannatə fràtə-mə a stutià. G1: * | G2: ✔ | G3: ✔AI-have sent brother-my to study‘I have sent my brother to study.’

- Agghə mannatə fràtə-mə ku ttə chiəmə. G1: ✔ | G2: ✔ | G3: *I-have sent brother-my ku to-you he-calls‘I have sent my brother to call you.’(Lit. ‘I have sent my brother that he calls you.’)

To summarise, at the time of Tempesta’s (1984) study, the youngest speakers of Cegliese (G3) were reported to be exclusively using the innovative IR-like non-finite complementation strategy in contexts such as (29a), rather than the traditional Cegliese strategy in (29b). The oldest speakers (G1) exhibited the opposite pattern, preferring the traditional ku + indicative strategy. The middle generation, G2, made use of both strategies, reflecting a transitional stage in this change in progress.

This change—in which the local language acquires a complementation strategy skin to IR, while simultaneously losing its traditional strategy for the same contexts—is clearly the result of micro-contact between Cegliese and IR of Apulia.

The case reported by Tempesta (1984) for Cegliese is a representative example of language change due to micro-contact in the sense of Andriani et al. (2022); Frasson (2022); Frasson et al. (2021), albeit one arising strictly between two Italo-Romance languages, unlike the cases those works discuss (but similar to the case of Ferentinese described above).

4.2. Case Study 2: IR of Sicily under Pressure from Sicilian?

As discussed in Section 2.2, it is far more common for the local languages of Italy to undergo change via contact with IR rather than vice versa; this is consistent with Heine and Kuteva’s (2003, 2005) claim that such changes typically flow from higher-prestige languages to lower-prestige ones. However, there are also attested cases of certain varieties of IR undergoing changes induced by the local languages they are in contact with.19

One such case comes from the variety of IR spoken in Sicily, documented in see also Amenta and Castiglione (2007, see also Amenta 2017): unlike SI—but very much like many local languages of Sicily—this variety of IR exhibits Differential Object Marking (DOM). That is, this IR variety introduces certain specific objects with a (Andriani 2016; Guardiano 2010, i.a.), directly parallel to the local languages it is in constant contact with:

- (30)

- DOM in Sicily (Amenta and Castiglione 2007, p. 70)

- Chiama a tua madre. IR of Sicilyyou-call dom your mother

- Chiama a tto matri.you-call dom your mother Sicilian (local languages)20‘Call your mother.’

Meanwhile, DOM is entirely unavailable in SI:

- (31)

- Standard ItalianChiama (*a) tua madre.you-call dom your mother‘Call your mother.’

Clearly, then, IR of Sicily has taken DOM not from SI, but from the particular local languages that it is in intense contact with.

Thus, the development of DOM in IR of Sicily described by Amenta (2017) appears to be another instance of micro-contact within Italy. To state this conclusively, however, we would need to have clear records of each of these (groups of) languages from a stage before the putative contact took place (Heine and Kuteva 2005). Although we have extensive written records for the local languages of Sicily (both before and after the arrival of SI: Leone 1995), we have no such records of what we might call ‘Early IR of Sicily’—namely, the stage of the language immediately following its genesis via creolisation (see note 20). As Berruto ([1987] 2021, p. 201) notes, this is a general problem for all varieties of IR; however, in this case it means we cannot conclusively establish whether DOM was transferred post-creolisation under contact with the local languages, or as part of the initial creolisation process itself (and thus not a traditional case of ‘contact’; see note 20).

Since the very existence of IR is the result of micro-contact driven change, establishing exactly when the innovation of DOM happened is impossible. This discussion is also related to the ‘baseline problem’ outlined by D’Alessandro (2021) and D’Alessandro et al. (2021): by the time of Amenta and Castiglione’s (2007) study, there may not have been any remaining monolingual speakers of the Sicilian local languages left, making it difficult to fully control for the potential influence of contact-related factors (see Section 2.1.3 for discussion).

5. Conclusions

This paper has explored a prima facie example of micro-contact within Italy, where the local Italo-Romance languages spoken at the level of individual towns have been in extensive contact with Standard Italian and, subsequently, Italiano Regionale (a group of languages arising from such contact). The main case study under investigation involves Ferentinese, a local Italo-Romance language from Southern Lazio whose complementizer system underwent significant structural changes over a short period (ca. 100 years) induced by extensive contact with another Italo-Romance language, namely Italiano Regionale. In particular, one of the forms exhibited by Ferentinese (che) underwent a change from occupying a high to a low position within the split CP. I argued that this change is an example of downward reanalysis from Force to Fin. Situating this language change within a generative model in which diachronic change is ‘acquisitional’, the process of reanalysis reflects the acquisitional process and the changes imposed by the child acquirer in response to ambiguous input, e.g., morphological opacity Willis (2010, 2016).

This reanalysis, I argued, was due to the regression of subjunctive mood and concomitant development of a new complementation strategy in Modern Ferentinese. In turn, this reflects one pathway to the genesis of a rare three-way complementizer system from an original two-way system due to micro-contact between Ferentinese and IR. IR features the complementizer form che which is homophonous with—and structurally identical to—one found in Early Ferentinese. Moreover, extensive evidence from early neighbouring varieties (e.g., Neapolitan) and metalinguistic data from speakers of Early Ferentinese support the claim that che in Early Ferentinese is the result of imperfect learning of IR as an L2 by native speakers of Pre-Early Ferentinese.

The genesis of the three-way complementizer system of Ferentinese is a case study of a micro-contact-induced change of the sort reported by D’Alessandro (2021); however, the case of micro-contact discussed here is novel in that it only involves Italo-Romance languages, and arises not due to immigration, but due to language policy (i.e., the imposition of SI on the local language communities). These minimally-different varieties have been in a situation of constant contact starting from the second half of the 19th century. Thus, this kind of change driven by micro-contact is likely to be pervasive throughout Italy, despite having been overlooked up to this point.

Funding

This research has received fundings from the Higher Education Authority of Ireland (HEA), COVID-19 Extension Fund 2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I thank Craig Sailor for his invaluable comments on an earlier draft of the present paper. This paper comes from our endless discussions on the linguistic situation found in Italy. I also thank three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Usual disclaimers apply. A CC BY license is applied to the Author Accepted Manuscript of this submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | A clear parallel can therefore be drawn between the status of SI in Italy on the one hand, and the status of Modern Standard Arabic in the Arabic-speaking world on the other hand. Like SI, Modern Standard Arabic is a literary variety that Schultz (1981) and many others have argued has no native speakers (in contrast with the innumerable ‘dialects’ of spoken/colloquial Arabic, which are in fact languages in their own right, parallel to the local languages in Italy: see below). |

| 2 | In some cases, alongside the languages spoken at this level, there are also languages spoken at the level of the geographical or administrative region (e.g., Lombard, Venetan, etc.; see Loporcaro 2009, p. 7). However, this is the exception rather than the rule (e.g., see Colasanti 2018c on the heterogeneity of the languages of the Lazio region, and the lack of a homogeneous ‘Laziale’ language). |

| 3 | Cf. work by (Beninca and Damonte 2009; Beninca and Poletto 2006; Cardinaletti 2004; Cardinaletti and Munaro 2009; Cruschina 2020; Golovko 2012; Poletto 2005, i.a.). |

| 4 | Here we have another terminological problem, since the term Italiano Regionale clearly implies that IR is a ‘regional variety of Italian’ (Cerruti 2011) or a ‘dialect of Italian’. By that same logic, though, we could just as easily consider a particular variety of IR to be a ‘dialect of’ the local language(s) it partially originated from, contrary to fact. Since IR originated from the extensive contact between SI and the local varieties it is by definition a contact language. Following Bakker and Matras (2013, p. 2), contact languages “are new languages, they usually emerged within one or two generations, and they contain major structural components that can be traced back to more than a single ancestor language”. By contrast, a dialect is usually defined as a sub-variety or sub-varieties of a single language (Meyerhoff 2006, p. 27). Perhaps the only variety that can be considered a true dialect of Standard Italian is the modern regional variety spoken in Rome, i.e., Romano (which underwent a process of ‘tuscanisation’ in 1600). |

| 5 | See also Berruto (2002) on neostandard Italian. |

| 6 | A full-sized scan of this map available at https://phaidra.cab.unipd.it/imageserver/o:318149 (Accessed: 4 November 2022). |

| 7 | In addition to the coexistence of all the Italo-Romance varieties in Italy, there have also been pockets of particular non-Italo-Romance languages spoken in Italy for centuries (e.g., Albanian, Catalan, German, Griko/Greko, Slovene, Croatian, French, Franco-Provençal, Friulian, Ladin, Occitan, and Sardinian), while these languages have of course undergone extensive contact with the Italo-Romance varieties spoken across the peninsula, such cases fall outside the scope of this paper. For more details on contact between Griko/Greko and Italo-Romance, see work by Ledgeway et al. 2020; 2021; Squillaci 2017; i.a. |

| 8 | We can retrieve examples of lexical borrowing in SI from the local languages: this is because SI was originally a literary variety, and thus its lexicon lacked entries for certain every day (especially heavily regional) concepts, e.g., those relating to food. |

| 9 | D’Alessandro (2021, et seq.) discuss cases of micro-contact in the heritage context. Many younger Italians nowadays are perhaps best characterised as heritage speakers of their local languages; however, I do not treat such heritage speakers in this paper. |

| 10 | Note that ‘Early Ferentinese’ refers to a variety in use during the 20th century—in other words, the ‘early’ here refers exclusively to the period of the earliest texts within the available corpus, which is admittedly quite recent (at least by traditional Italo-Romance historical standards: cf. Early Neapolitan texts dating back to c. 1200–1600, for example): it comprises texts written during the first half of the 20th century, published only at the end of the 20th century (Angelisanti 1983; Bianchi 1974, 1978, 1982, 1984, 1991a, 1991b; Cedrone 1975; Cupini 1961; Prosperi and Bianchi [1942] 1980). I acknowledge that the history of Ferentinese likely predates the earliest texts in this corpus by several centuries (thus, should earlier written texts be subsequently discovered, a terminological revision for this stage of the language would be necessary). On the other hand, ‘Modern Ferentinese’ refers to the late 20th/early 21st century variety of Ferentinese. Most of the Early and Modern Ferentinese data come from Colasanti (2017, 2018b) and the author’s own fieldwork in Ferentino between 2015 and 2018. |

| 11 | Specifically, the texts variously represent this form as ‘che’ and ‘chə’, the latter being a faithful phonetic representation of word-final /e/ in Ferentinese. Since local Italo-Romance languages did not undergo orthographic standardisation, there is no uniform strategy for representing [ə]; however, use of the grapheme <e> is extremely common in many early Italo-Romance documents (e.g., from Early Neapolitan), and continues to be used today. |

| 12 | In describing the distribution of the three different complementizers in Ferentinese, I consider factive predicates (Kiparsky and Kiparsky 1970) such as ‘regret’, ‘know’, ‘like’, etc. (henceforth, regret-verbs), verbs of saying/thinking (henceforth say-verbs), and verbs of wanting (henceforth, want-verbs). |