2.4.1. Narrow Focus Constructions

Besides syntactic structure, the focus-background partition of sentences and the information status of constituents affect the assignment of stress. It is assumed that constituents belonging to the focused part of a sentence are marked with a feature F in syntactic representation, which is assigned a semantic and a phonological interpretation (

Jackendoff 1972). As for the phonological interpretation, various studies provided empirical evidence for the assumption that nuclear stress must be located in the focused part of a sentence (e.g.,

Cooper et al. 1985;

Eady and Cooper 1986 for English;

Baumann et al. 2007;

Féry and Kügler 2008 for German). This has been captured by means of the constraint

Stress-Focus (16), which employs the notion of focus domain (

Truckenbrodt 1995; see

Féry and Samek-Lodovici 2006 for the specification adopted here). In this line of research, the focus domain serves as the basis for the interpretation of narrow focus constructions and the assignment of the highest prominence (i.e., nuclear stress) of a sentence. In the present paper, we will restrict the discussion to cases of narrow focus where the entire sentence serves as the focus domain (but see

Féry and Samek-Lodovici 2006 for nested focus constructions that entail a more complex distribution of focus domains). For example, the sentence presented in (17) involves a narrow focus on the subject (hence, the F mark annotation) and a contextually given verb in post-focal position. The relevant background for the interpretation of focus is the entire sentence (i.e., [X

F schlafen]). As a result,

Stress-Focus enforces nuclear stress on the subject NP (

Eltern) instead of the verb (

schlafen), which would bear nuclear stress otherwise (according to the requirements of

Match-Phrase and

Rightmost), as it is the only element in the VP and it stands in rightmost position.

| (16) | Stress-Focus |

| | A focused phrase has the highest prosodic prominence in its focus domain. |

| (17) | Who’s sleeping? |

| | Die | [Eltern]NP, F | [schlafen]VP |

| | the | parents-NOM | sleep-PRES |

| | ‘The parents are sleeping.’ |

Most accounts on the prosodic structure of narrow focus constructions assume that the given material following the focused constituent does not bear (regular) phrasal stress and is thus unaccented (e.g.,

Truckenbrodt 1995;

Féry and Samek-Lodovici 2006 for English;

Baumann et al. 2007;

Féry and Kügler 2008;

Féry 2013 for German). Under this assumption, the subject in (17) is the only element that bears a beat of phrasal stress, as is suggested by the absence of underlining of the verb. We will refer to this assumption as the ‘dephrasing-of-φ-structure view’. In contrast, some studies argue that the prosodic structure is retained on given material in post-focal position (e.g.,

Féry and Ishihara 2010;

Kügler and Féry 2017). Evidence for this assumption comes from the observation that pitch accents undergo a large amount of register compression, but are indeed realized in this position (

Kügler and Féry 2017, see below for details; see also

Wagner and McAuliffe 2019 for English). Since pitch accents are taken as instantiations of phrasal stress, their presence suggests the presence of φ-phrases. We will refer to this assumption as the ‘preservation-of-φ-structure view’.

2.4.2. Stress Rejection Due to Givenness

Given elements can also occur within the focused part of a sentence, in which case they may reject stress (e.g.,

Ladd 1980,

1983,

1996;

Selkirk 1984;

Gussenhoven 1992;

Schwarzschild 1999). As was mentioned in the introduction,

Féry and Samek-Lodovici (

2006, p. 145) present such a case from English, which is here reproduced with modified annotations in (18). F-marks are omitted, but the focused part of the answer, as induced by the context question, is marked with FOC instead. The NP at the end of the sentence (

John) is discourse-given since it is mentioned in the context question.

Féry and Samek-Lodovici (

2006) point out that nuclear stress is assigned to the object NP (

Rome), indicated by underlining in (18), although it is not the last lexically headed XP in the focused constituent. The constraints on stress assignment established so far predict that the NP at the end must receive nuclear stress.

5 However, as this NP is a given element, stress falls on the next preceding constituent that is eligible for stress assignment.

| (18) | What did John’s mother do? |

| | She [went to Rome with [John]G]FOC |

Féry and Samek-Lodovici (

2006) account for this effect by employing the constraint

Destress-Given (19), which militates against prosodic prominence on constituents that are given in discourse. The use of such a constraint requires the assumption of a givenness feature G. Constituents that are given in discourse undergo G-marking in syntactic representation (hence, the G mark annotation in (18) and the following examples). These constituents are identified as given elements by

Destress-Given. As will be discussed below, the specification of this constraint as posited here is problematic for other cases.

| (19) | Destress-Given |

| | A given phrase is prosodically nonprominent. |

Before further addressing the specification of

Destress-Given, we will first establish that the stress rejection effect illustrated in (18) also applies in German, and not only to final elements but also to pre-final ones that would otherwise be assigned nuclear stress. In (20), the focused part of the answer includes the verb (

loben) and the object (

Jan). As discussed above, the default nuclear stress position for this type of sentences is on the object. However, as the object is mentioned in the context question, nuclear stress falls on the preceding verb. Thus, as in the case from English in (18), nuclear stress is rejected by a given element in final position and is instead assigned to the next preceding element in the focused part of the sentence. The pitch contour of a production of this sentence is presented in

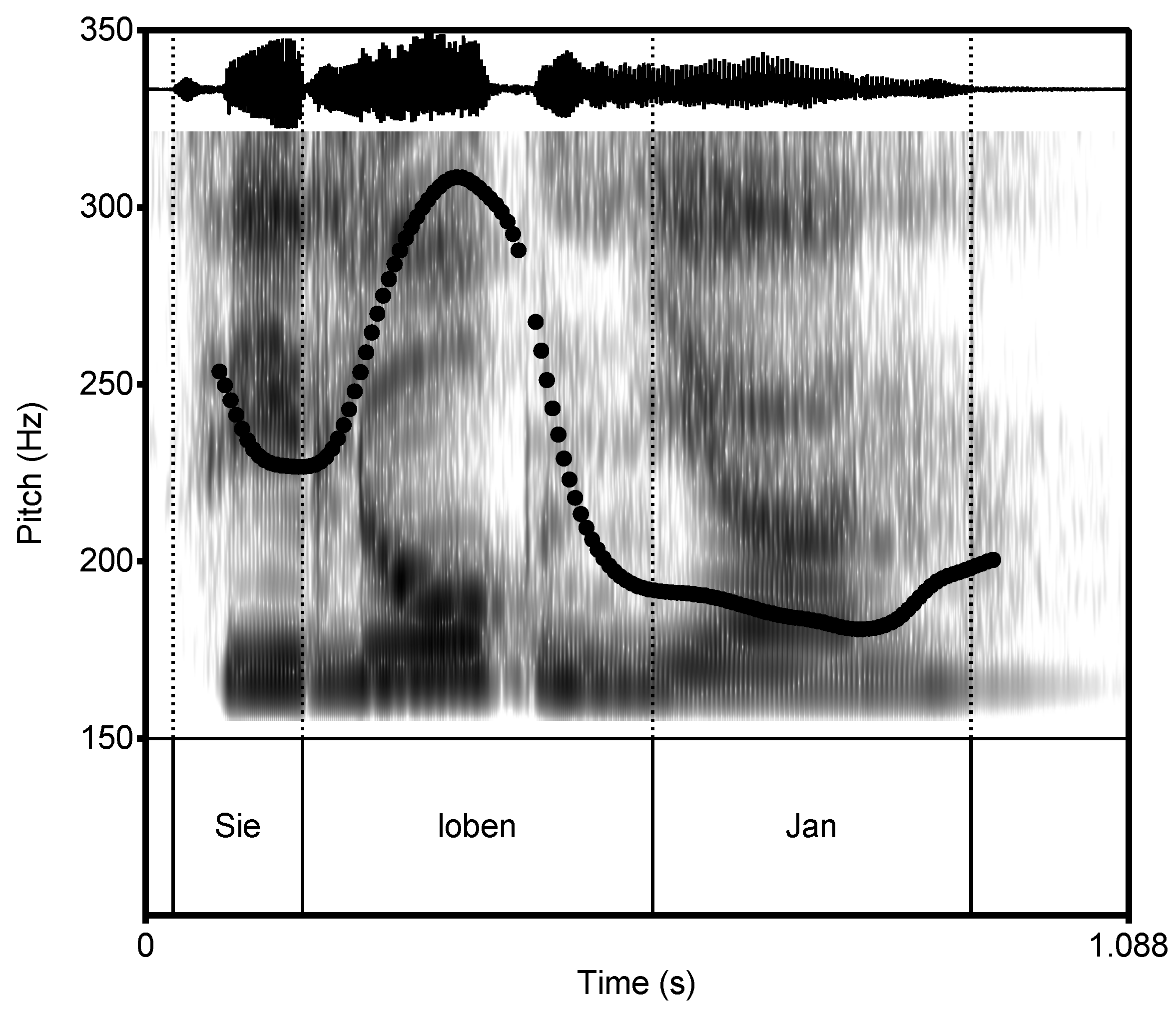

Figure 1.

6 The contour involves a rising movement in the initial portion and a falling movement in the final portion of the verb (

loben), and remains low on the following object (

Jan). This suggests that the verb bears nuclear stress, which is instantiated by a nuclear pitch accent.

7| (20) | What are Jan’s parents doing? |

| | Sie | [loben | [Jan]NP, G]FOC |

| | they | praise-PRES | Jan-ACC |

| | ‘They are praising Jan.’ |

The example in (21) provides a case that involves the same stress rejection effect as the prior one, but has reversed order of the object and the lexical verb. Here, the focused part of the sentence includes the object (

Jan) and the following verb (

loben). As discussed above, the default position for nuclear stress assignment in such a sentence is the pre-final object and not the final verb. However, as the object is given in discourse, it rejects stress, which is instead assigned to the following verb (which is the only element eligible for stress assignment in the case at hand, as it is the only new element in the focused part). This case shows that stress rejection also applies to elements in pre-final position and that stress can be shifted to a following element.

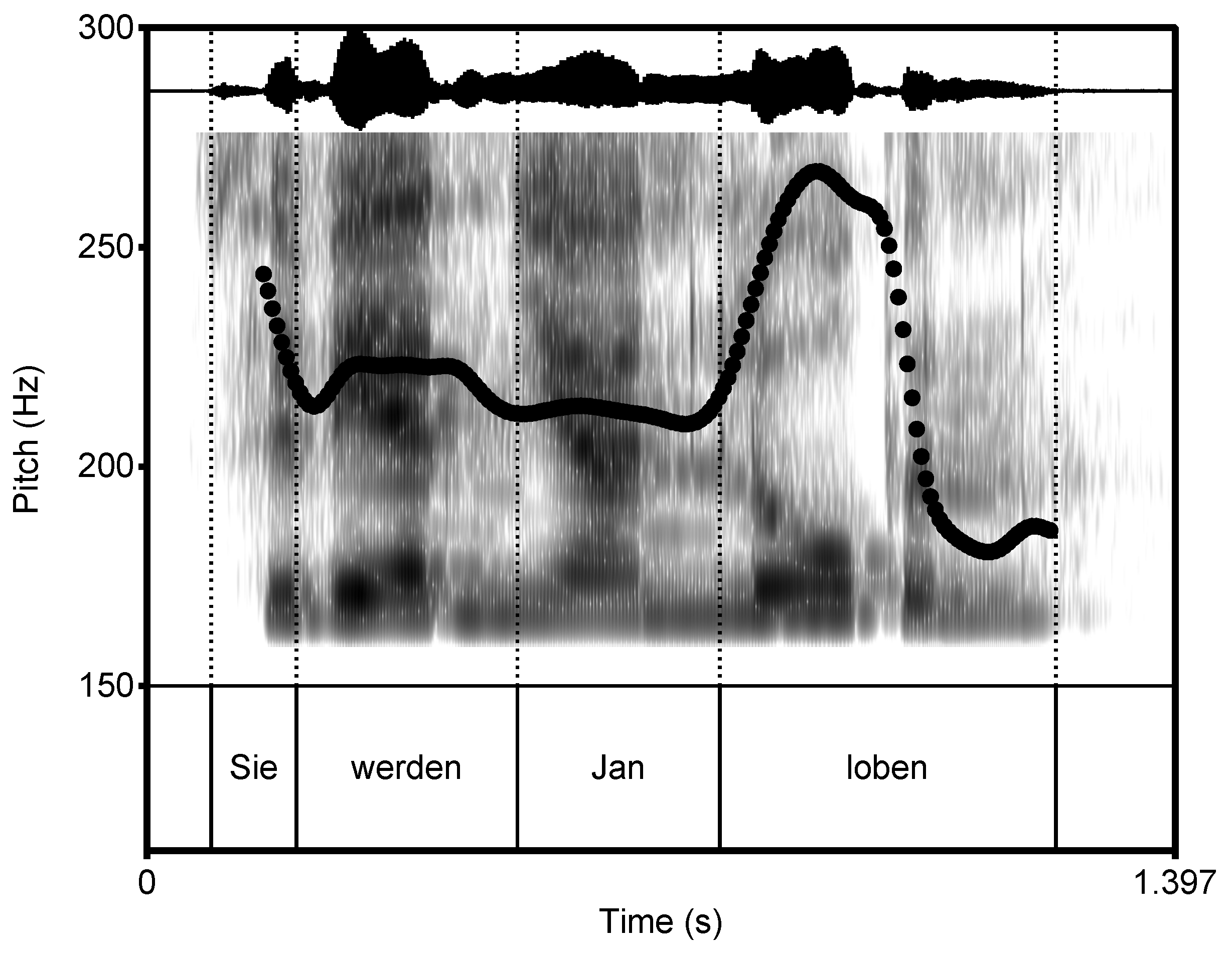

Figure 2 shows the pitch contour of a production of the sentence as an answer to the context question in (21). In this case, the contour involves a downstep from the auxiliary (

werden) to the object (

Jan). After that, on the verb (

loben), the contour involves a high-rising movement in the initial part, a falling movement in the middle, and remains low in the last part. As in the prior case, this pattern suggests that the verb bears nuclear stress, instantiated as a nuclear pitch accent.

8| (21) | What will Jan’s parents do? |

| | Sie | werden | [[Jan]NP, G | loben]FOC |

| | they | will-AUX | Jan-ACC | praise-INF |

| | ‘They will praise Jan.’ |

2.4.3. Constraint-Based Analyses of Stress Rejection

Experimental studies found that given elements in pre-focal position often bear phrasal stress (e.g.,

Cooper et al. 1985 for English;

Baumann et al. 2007;

Féry and Kügler 2008;

Schubö 2020 for German; see also

Grice et al. 2009). For example,

Baumann et al. (

2007) recorded sentences under different focus conditions. They analyzed 432 productions (collected from six speakers) and found that pre-nuclear pitch accents occurred on given constituents in the vast majority of cases across conditions (98% for broad focus, 94% for information focus, and 86% for contrastive focus).

Féry and Kügler (

2008) conducted a similar study, yet with a larger variety of materials and more speakers. They analyzed a total of 2277 productions from 18 speakers and found that the pitch register was compressed on pre-focal given arguments, but pitch accents were commonly present in this position. These findings are incompatible with the specification of

Destress-Given, since the presence of pre-focal pitch accents indicates the presence of phrasal stress on given elements. That is, unlike required by

Destress-Given, given phrases can be prosodically prominent. Thus, the constraint should allow for (non-nuclear) phrasal stress on given elements.

As a solution to this problem,

Féry (

2013, p. 719) proposed to restrict the constraint to militating against “post-nuclear given phases[s]”. This is in line with the dephrasing-of-φ-structure view, under which phrasal stress positions are absent in post-focal position, but may be present in pre-focal position. This is however problematic for the cases of stress rejection discussed above in which the assignment of nuclear stress depends on

Destress-Given. In these cases, nuclear stress shifts from one element to another due to the givenness status of the word that is in the default position for nuclear stress assignment. If

Destress-Given was restricted to the post-nuclear part of the sentence, it would be necessary to assume that the shift of nuclear stress results from a different mechanism, and it remains unclear what mechanism this would be. As will be illustrated in the next section, it is not necessary to employ

Destress-Given (or a similar constraint) in order to account for the dephrasing of post-focal φ-structure. Another problem with this restriction is that the identification of post-nuclear material would require some sort of marking in phonological representation, an assumption that is not needed elsewhere in the formation of prosodic structure.

Recent experimental evidence suggests that pitch accents, and thus beats of phrasal stress and φ-phrases, are also retained in post-focal position in German:

Kügler and Féry (

2017) analyzed 187 productions (collected from eleven speakers) involving a narrowly focused element and followed by either, one, two, or three given arguments in post-focal position. An analysis of the F0 scaling patterns revealed a downstep or upstep effect among the post-focal arguments in 63 percent of instances. These effects are taken as correlates of phrasing, suggesting that the post-focal arguments form independent φ-phrases. These findings strengthen the preservation-of-φ-structure view, under which given elements can bear prosodic prominence in any position of the sentence. This view is generally incompatible with the specification of

Destress-Given in (19) as well as with the assumption that the constraint only affects post-nuclear given phrases.

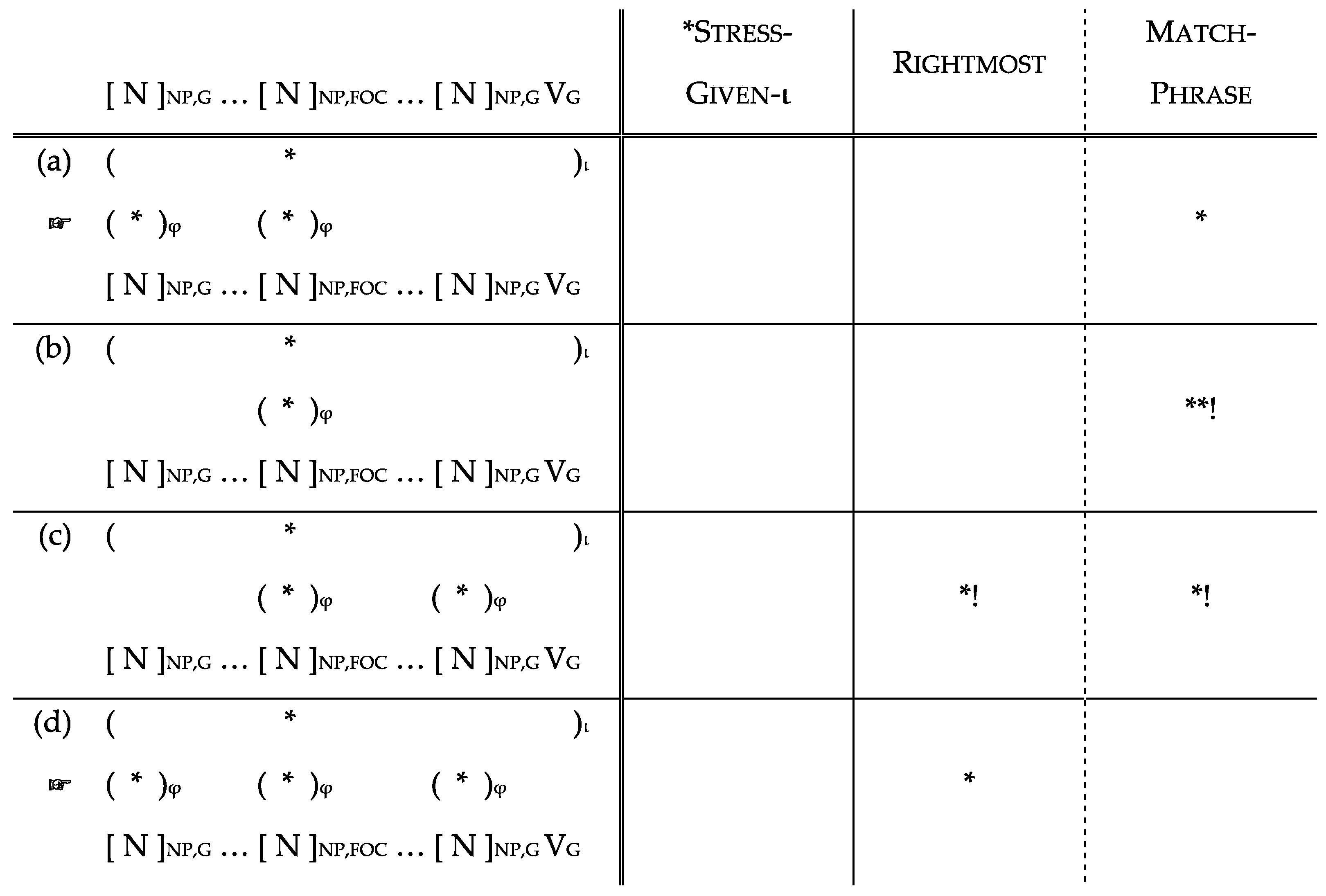

The predictions of phrasal stress distribution of the dephrasing-of-φ-structure and the preservation-of-φ-structure view are illustrated in (22). This example involves a sentence with three lexical arguments of which the second one, the indirect object (

Jan), is focused and thus receives nuclear stress (indicated by double-underlining). The subject (

die Eltern) receives a regular beat of phrasal stress (indicated by single-underlining of the NP). The direct object (

ein Auto), which immediately precedes the lexical verb at the end, does not receive phrasal stress under the dephrasing-of-φ-structure view. Under the preservation-of-φ-structure view, this object however does comprise a beat of phrasal stress. The discrepancy between the two assumptions is indicated in (22) by dotted underlining of the NP of the direct object. The prosodic structure under the dephrasing-of-φ-structure view is illustrated in (23) and the one under the preservation-of-φ-structure view in (24). Annotations for VPs and their corresponding φ-phrases are omitted. In compliance with

Stress-φ, each φ-phrase contains a beat of stress that serves as its prosodic head.

| (22) | To whom will the parents give a car? |

| | Die | [Eltern]NP, G | werden | [Jan]NP, FOC | ein | [Auto]NP, G | schenken. |

| | the | parents-NOM | will-AUX | Jan-DAT | a | car-ACC | give-INF |

| | ‘The parents will give a car to Jan.’ |

| (23) | ( | | | | * | | | | | ) | ι-structure |

| | ( | * | ) | ( | * | ) | | | | | φ-structure |

| | [ | N | ]NP | [ | N | ]NP, FOC | [ | N | ]NP | |

| (24) | ( | | | | * | | | | | ) | ι-structure |

| | ( | * | ) | ( | * | ) | | ( | * | ) | φ-structure |

| | [ | N | ]NP | [ | N | ]NP, FOC | [ | N | ]NP | |

Another example is provided in (25). The subject of this sentences contains a possessor NP (

Tom) and a possessee NP (

Eltern). As an answer to the preceding context question, the possessor is focused, as it is Tom’s and not Jan’s parents who will give Jan a car, and it is thus assigned nuclear stress (again indicated by double-underlining). The remaining lexical XPs of the sentence are given and do not receive phrasal stress under the dephrasing-of-φ-structure view, but do under the preservation-of-φ-structure (again indicated by dotted underlining). The prosodic structures are shown in (26) and (27), respectively. Under the dephrasing-of-φ-structure view, neither of the post-focal NPs is matched by a φ-phrase (26) whereas, under the preservation-of-φ-structure all of the post-focal NPs are matched by a corresponding φ-phrase. Given that this sentence has several constituents containing lexical XPs in post-focal position, it appears likely that φ-phrases (and thus phrasal stress positions) emerge for rhythmical reasons, yielding the prosodic structure in (27).

| (25) | Jan’s parents will give a car to Jan? |

| | [Toms]NP, FOC | [Eltern]NP, GIV | werden | [Jan]NP, GIV | ein | [Auto]NP,GIV |

| | Tom’s | parents | will | Jan | a | car |

| | schenken. |

| | give |

| | No, Tom’s parents will give a car to Jan. |

| (26) | ( | * | | | | | | | | | | | ) | ι |

| | ( | * | ) | | | | | | | | | | | φ |

| | [ | N | ]NP, FOC | [ | N | ]NP | [ | N | ]NP | [ | N | ]NP | |

| (27) | ( | * | | | | | | | | | | | ) | ι |

| | ( | * | ) | | ( | * | ) | ( | * | ) | ( | * | ) | φ |

| | [ | N | ]NP, FOC | [ | N | ]NP | [ | N | ]NP | [ | N | ]NP | |

Independent of the view one adopts with regard to post-focal φ-structure, the mentioned specifications of

Destress-Given cannot account for the rejection of nuclear stress by given elements that are part of the focused constituent and at the same time be compatible with the presence of φ-phrases (and thus stress positions) that contain given elements.

Ladd (

1980, p. 56) remarks that the rejection of nuclear stress on a given element is achieved by “relative weakening of its hierarchical rhythmic position”, and that this weakening leads to different prosodic patterns depending on the order of the involved elements. In case nuclear stress shifts to an earlier element in the sentence, the weakened element is in post-nuclear position, which is prosodically weak and thus leads to destressing. If nuclear stress however shifts to a later element, the weakened element is in pre-nuclear position and receives “secondary stress” (

Ladd 1980, p. 57). In both cases,

Ladd (

1980, p. 57) remarks, the resulting rhythmic structure involves a pattern in which the given element is perceived as relatively weaker. This observation suggests that the mechanism responsible for stress rejection only affects the highest prominence in the sentence, which is ι-level prominence in terms of the Prosodic Hierarchy given in

Section 2.1.

Frey and Truckenbrodt (

2015) capture this pattern in a version of

Destress-Given that restricts the stress rejection to sentence stress, which corresponds to nuclear stress (or ι-level prominence) in the terminology adopted here. The formulation employed in

Frey and Truckenbrodt (

2015) is given in (28)

. This formulation overcomes the problem of

Destress-Given as posited in

Féry and Samek-Lodovici (

2006) by allowing for (non-nuclear) phrasal stress on given elements.

| (28) | *Stress-Given |

| | Do not assign sentence stress to a constituent marked as G (i.e., contextually |

| | given). |

In a comprehensive account of the distribution of stress in English,

Büring (

2016, ch.2) captures the observation that given elements do not bear the strongest prominence by means of the condition in (29). The first part of this condition corresponds to the constraint in (28). The

F-Realization Condition referred to in the second part of (29) is an adaptation of

Stress-Focus. Büring (

2016, p. 164) later models the condition in (29) as the constraint

Focus Realization, which requires that “[t]he highest stress within a F-domain

D falls on a focus of

D” (in line with, e.g.,

Truckenbrodt 1995 and

Féry and Samek-Lodovici 2006). Furthermore,

Büring (

2016, p. 173) points out that the

G-Realization Condition (29) can be construed as a combination of two constraints: a constraint militating against nuclear stress on given elements (29) and a higher-ranking

Focus realization constraint.

| (29) | G-Realization Condition |

| | A G-marked constituent does not contain the nuclear accent, unless forced by |

| | the F-Realization Condition. |

In the account proposed in

Büring (

2016, ch. 7), the constraint on stress rejection is eventually modeled as stated in (30). The indirect formulation is meant to comply with cases where an entire ι-phrase contains given material so that nuclear stress must fall on a given element. This is illustrated in (31) with an example from

Büring (

2016, p. 174, stress marks adapted). The first clause of the answer is a repetition of the second clause of the question and thus comprises only given material. The repeated clause however does involve a nuclear stress (

Kim), as it is realized as a separate ι-phrase. The same holds for the German example in (32), which is an adaptation of (31). As in the English example, nuclear stress falls on the object (

Tom), which in this case is followed by the verb. The pattern in (31/32) is compatible with (30), but not with (28/29). Regarding the English example in (31),

Büring (

2016, p. 174) remarks that the beat of nuclear stress on the focused clause might have stronger prominence than the one on the given clause. Intuitively, this also seems to hold for the German adaptation in (32). Nuclear stress on

Ärger (‘trouble’) appears stronger than nuclear stress on

Tom.

9 This can be represented by means of a recursive ι-structure involving a higher ι-phrase for the entire sentence and an additional beat of nuclear stress on the focused clause (see

Schubö 2020 for recursive ι-structure in German).

| (30) | Givenness Realization |

| | If the strongest stress in a prosodic constituent π is on a given element, π itself |

| | is given. |

| (31) | What happens if Sam talks to Kim? |

| | If Sam talks to Kim, we’re in big trouble. |

| (32) | Was passiert, wenn Jan mit Tom spricht? |

| | Wenn | Jan | mit | Tom | spricht, | haben | wir | großen |

| | if | Jan-NOM | with | Tom-DAT | talks | have-PRES | we | big |

| | Ärger. |

| | trouble-ACC |

| | ‘If Jan talks to Tom, we’re in big trouble’ |

The constraints in (28/29) and (30) both predict the correct stress distributions. They however differ in the following respects: Givenness Realization (30) is a relational constraint that applies to each category in the Prosodic Hierarchy (π), not only to instances of nuclear stress (i.e., on the ι-level). Thus, it potentially also militates against instances of regular phrasal stress. Given the data discussed above, this is not necessary, since a constraint enforcing stress rejection due to givenness only needs to affect nuclear stress. Therefore, the more restricted stress rejection constraint in (28/29) is adopted here, which also conforms more with statements of constraints used in the framework of OT. The problem that this constraint is incompatible with the pattern in (31/32) is solved by the assumption of an undominated constraint Stress-ι. As stated earlier, this constraint enforces a nuclear stress position in any ι-phrase, regardless of the givenness status of the contained material. Thus, Stress-ι enforces the emergence of nuclear stress in cases as (31/32) in violation of the constraint that militates against nuclear stress positions on given elements.

The stress rejection constraint employed in

Frey and Truckenbrodt (

2015) and included in

Büring’s (

2016)

G-Realization Condition (25) is referred to as *

Stress-Given-ι in the following. This constraint is formalized as in (33). For the evaluation of output structures, the formalization is to be interpreted in the following way: Assign one violation mark for each beat of stress on the level of the ι-phrase that is located on a discourse-given morpho-syntactic constituent.

| (33) | *Stress-Given-ι |

| | A given constituent does not bear nuclear stress. |