Aspectuo-Temporal Underspecification in Anindilyakwa: Descriptive, Theoretical, Typological and Quantitative Issues

Abstract

1. Introduction

| (1) | kembirra | nəm-awiyebe-nə=ma | mamawura. |

| then | real.veg-enter-pst=stype | veg.sun | |

| ‘Then the sun set’ | |||

| (Mərungkurra Text, 28–9) | |||

| (2) | a. | yarrungkwa | n-akən | nenəngkwarrba | nəm-akbərranga-Ø=ma |

| yesterday | 3m-that | 3m.man | real.3m>veg-find-usp=stype | ||

| mijiyelya | |||||

| veg.beach | |||||

| ‘Yesterday he found the beach’ (JL, JRB1-018-01, 00.05.31) | |||||

| b. | ngayuwa | ngu-məreya-Ø | anhəngu=wa | ||

| 1.pro | real.1-be.hungry-usp | neut.food=all | |||

| ‘I’m hungry for food’ | |||||

| (JL, 2016-07-15_01_JL, 00.15.27-00.15.32) | |||||

1.1. The Anindilyakwa Language and Its TAM System

| (3) | ning-alburre-na=wiya | ni-yama-Ø |

| real.1>neut-split-npst=quant | real.3m-say-pst | |

| ‘“I’m splitting it” he said’ [i.e., I’m in the middle of splitting it] | ||

| (Yingarna-lhangwa, A3369a Side2 a3.11) (Bednall 2020, p. 276) | ||

1.2. A Quick Overiew of Existing Analyses, and Some More Details on Our Research Question

- The Deictic Principle: Runtimes of events are located with respect to Speech Time, Smith et al. (2007, p. 44), Smith (2008, p. 231)

- The Simplicity Principle of Interpretation: Choose the interpretation that requires the least information added or implied, Smith et al. (2007, p. 60);

- The Event Structure Properties Principle:2 Interpret zero-marked sentences according to the aspectual properties (i.e., event structure properties) of the event denoted by the sentence (Smith et al. 2007, p. 61).a. Stativity Constraint: stative events are not located in the past.b. Atomic Constraint: atomic (i.e., punctual) events are not located in the present.c. Atelic dynamic events, and non-atomic telic events can freely anchor in the past or the present (Bednall 2020, pp. 221–22).

- The Bounded Event Constraint (or ‘Deictic Principle of Temporal Interpretation’, Smith 2006:92):3 bounded events cannot anchor to the present (and conversely, presently anchored events must be unbounded; Smith 2008, p. 230)—this constraint is partially equivalent to the so-called perfective present paradox, given that perfective viewpoints select for bounded events and they too, cannot anchor to the present, by and large; see De Wit (2016).

| (4) | ngayuwa | ngu-məreya-Ø | anhəngu=wa |

| 1.PRO | REAL.1-be.hungry-USP | NEUT.food=ALL | |

| a. ‘I’m hungry for food’ | |||

| b. *I was hungry for food | |||

| (JL, 2016-07-15_01_JL, 00.15.27-00.15.32) | |||

2. Materials and Methods

- Elicited utterances (particularly useful for getting at temporally empty contexts), either through traditional questionnaires (especially as translation tasks), meta-linguistic elicitation material (e.g., morphological flash cards), or experimental elicitation based on the Event Description Elicitation Database (EDED, cf. Mailhammer and Caudal 2019); see below, and Caudal & Mailhammer (this volume) for further details);

- Oral narratives recorded in 2016–2019, as well as a collation of legacy narrative recordings (1970s–90s);

- A (partial) translation of the Bible (Bible Society in Australia 1992): Neningikarrawara-angwa Ayakwa.

2.1. Constitution of Our Three Sub-Corpora

2.2. On Temporal and Aspectual Information Incorporated in Our Annotation Scheme

| (5) | dhukwa | arakb | ni-yedha-Ø-m=dha |

| maybe | compl.act | real.3m-arrive-usp=stype=trm | |

| ‘Maybe he [has] already arrived’ (JL, JRB1-042-01, 00:11:26-00:11:42) | |||

| (6) | nginu-maka-Ø=ma | neniyarringka | nungw-arrka |

| real.3m>1-tell-pst=stype | 3m.respected.old.man | 3m.father-kin.1 | |

| yirr-ambilyu=manja | Yingakumanje=ka | ena | |

| real.1a-stay.pst=loc | place.name=emph | neut.this | |

| alhawudhawarra | |||

| neut.story | |||

| ‘My old father told me this story when we were staying at Yingakumanja’ | |||

| (Dingarna-langwa akwa wurruwarda-langwa A3369a Side1 a3.5) | |||

| (7) | arakba | wurri-rn-dhərnd-arrngwa | iya | wurr-akəna | |

| compl.act | 3a.redup(?)-mother-3a.kin | and | 3a-that | ||

| wurru-ngwu-ngw-arrngwa | na-wurrak-aburiya-Ø | ||||

| 3a.redup(?)-father-3a.kin | real.3a-many-be.stuck-usp | ||||

| arakba | arrawu=wa | ||||

| compl.act | underneath=all | ||||

| ‘their mothers and fathers were stuck [=became stuck] in the ground’ (JL, A3369b Side1, a4.2 Jigagwa-langwa-langwa daburradikba akwulyangburarrka ‘Her daughter’s dream’) | |||||

| (8) | y-aka | yirrburrbula | n-angkarra-Ø | m-əkəna |

| masc-this | masc.ball | real.masc-roll-usp | veg-that | |

| [nu?]ma-jama-Ø | akəna | wall=a | akwa | |

| real.veg-do-pst | neut.that | neut.wall= pf | and | |

| [nə?]-nguwanjə-n=dha | ||||

| real.neut(?)-stop-pst=trm | ||||

| ‘The ball rolled, hit the wall and stopped’ (ST, JRB1-034-01, 00.16.53-00.17.00) | ||||

| (9) | bi:::ya | nu-walyuwu-Ø=manji=kba=dha, | y-akina | |

| and.then.xtd | real.3m-be.cooked-usp=loc=deniz=trm | masc-that | ||

| yimarndakuwaba | y-inumalye=ka=dangba | |||

| masc.blue.tonged.lizard | masc-good?=emph=emph | |||

| ‘When at last that blue-tongued lizard was cooked to perfection, it was the fattiest, juiciest blue-tongued lizard that ever was’ (Kwurrirda Kwurrirda-langwa, A3369a Side1 a3.3) | ||||

| (10) | yingi-rukwulyaka-Ø | ying-angkarru:::-Ø=wa, | ||

| real.3f-go.around-pst | real.3f-fly.xtd-usp =pl | |||

| ying-arjiyi-nga | akuwabijina | awurukwa | ||

| real.3f-stand-cofs-Ø | beside | neut.billabong | ||

| ‘She flew down and circled round and round (until) she stood at the edge of the billabong’ (GL, A3369a Side1, a3.7 Nimimba-langwa akwa nenikuwenikba-langwa ‘The blind man’) | ||||

2.3. Some Theoretical Reflections about the Role of Discourse Structure in Our Annotation and Analysis

| (11) | a. | Mon fils arriva en retard à l’école. L’instituteur le gronda. | (Narration/Result) |

| My son come-PS.3sg in late at the.school. The teacher PRO.3sg scold-PS.3sg | |||

| b. | Mon fils est arrivé en retard à l’école. L’instituteur l’a grondé | (Narration/Result) | |

| My son be.PR.3sg come-PP in late at the.school. The teacher PRO.3sg-have.PR.3sg scold-PP | |||

| ‘My son was late at schoolCause. The teacher scolded himEffect.’ | |||

| (12) | a. | L’instituteur gronda mon fils. #Il arriva en retard à l’école. | (#Explanation) |

| The teacher scold-PS3sg my son. He arrive-PS.3sg in late at the.school | |||

| b. | L’instituteur a grondé mon fils. OKIl est arrivé en retard à l’école. | (Explanation) | |

| The teacher have.PR.3sg scold-PP my son. He be.PR.3sg arrive-PP in late at the.school | |||

| ‘The teacher has scolded my sonEffect. He has been late at schoolCause.’ | |||

| (13) | nu-ngurrkwa-rnə=ma | yiburadhu=wa | |

| real.3m>masc-hunt-pst=stype | masc.wallaby=all | ||

| akena | n-angkarra-Ø | ||

| but | real.masc-run-usp | ||

| ‘[The man] was hunting the wallaby, but it ran away’ (ST, JRB1-034-01, 00.06.53-00.07.01) | |||

2.4. On the Close Association of (Un)boundedness with Viewpoint

2.5. Some Reflections on the Quality and Controlled Nature of Our Annotation Procedure

3. Results of Our Quantitative Study

3.1. Some Preliminary Observations and Empirical Generalizations: Zero Tense vs. Other Indicative Tenses, and Event Structure Types

| (14) | angkawura | angkwababərna | nə-lhəka-Ø | en=lhang=wa | angalya |

| one.day | always | real.3m-go-usp | 3m.pro=poss=all | neut.place | |

| ‘he went to his house several times’ (JL, JRB1-049-01, 00.09.25-00.09.34) | |||||

| (15) | arakbəwiya | angkabəbərnama | nə-lhəka-Ø | en=lhang=wa |

| long.ago | always | real.3m-go-usp | 3m.pro=poss=all | |

| angalya | ||||

| neut.place ‘like several times, many times, or several times he used to- went- walked to his house’ (JL, JRB1-049-01, 00.13.00-00.13.20) | ||||

| (16) | ngumu-ngwanja-jə-na=ma | duraka |

| real.1>veg-stop-caus-npst=stype | veg.car | |

| ‘I’m stopping the car’ (progressive or prospective/futurate reading) (JL, JRB1-018-01, 00.15.37-00.15.42) | ||

| (17) | ambaka+lhangw | na-mənəngka-dhə-nə=ma | ena | angalya |

| slowly | real.neut-different-inch-pst=stype | neut.this | neut.place | |

| ‘slowly this place seems to get different’ (JL, JRB1-007-01, 00.01.29-00.01.34 narrative) | ||||

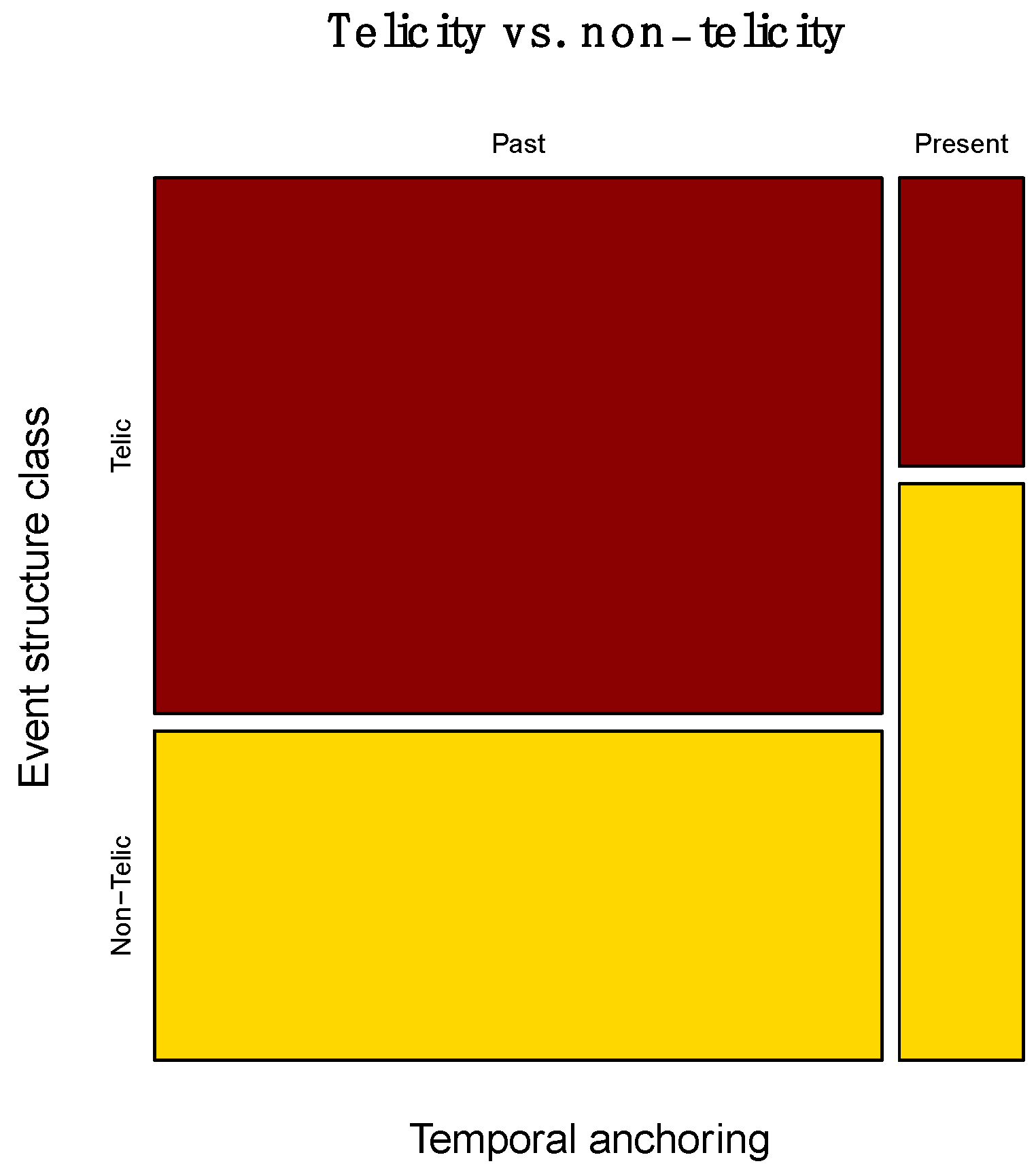

3.2. Telicity vs. Non-Telicity and Zero Tense

| (18) | “nə-dhədha-ngu=ma”, that’s past, | “nə-dhədhu-Ø=ma”, that’s now |

| REAL.3M-shut-PST=SType | REAL.3M-shut-USP=SType |

3.3. Dynamic vs. Stative Utterances and Zero Tense

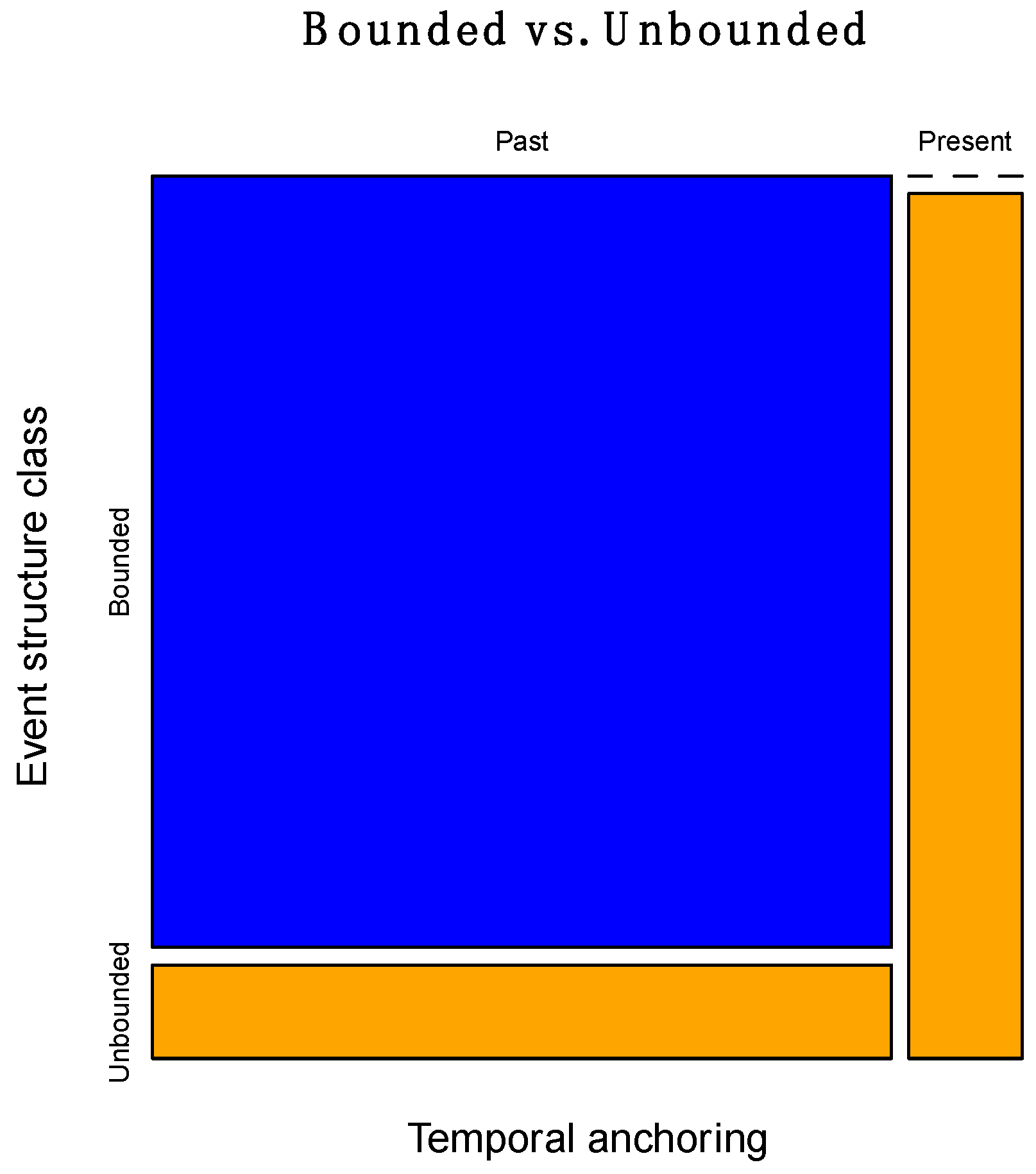

3.4. Unbounded Events vs. CoS/Bounded Events and Zero Tense

4. Discussion

4.1. Possible Aspectuo-Temporal Biases Due to Discourse/Textual Genres?

4.2. Some Novel Language-Specific Generalizations for the Anindilyakwa Zero Tense

- Only utterances denoting bounded or atomic telic events (including inchoative meanings, and single semelfactive events) monotonically determine (past) temporal anchoring, as it cannot be overruled or modified by any additional information or overt temporal marker

- The temporal anchoring of all other event structural types of utterances (i.e., unbounded utterances) can be either present or a past in our corpus, and is sensitive to aspect-independent temporal information, even for unbounded readings of accomplishment utterances; this can be achieved by overt temporal marking of the verb at stake—through e.g. past vs. present adverbials—or through some other verb with which it forms a temporal reference chain, i.e., when the corresponding discourse referents are part of a single discourse topic; we argue that such topics are very important discourse contextual factors in the semantics and pragmatics of tenses (see Caudal 2023 for a detailed discussion). In short, only unbounded utterances can have both past or present anchoring—and must conform to whatever contextual information sets the reference/topic interval to the past vs. present in the context, even though in temporally empty context, stative and activity utterances non-monotonically anchor to the present. This is a novel generalization in comparison to Bednall (2020).

4.3. Some Novel Cross-Linguistic Generalizations for Zero Tense (and Zero-Tense)

| (19) | Jeŋkul=mani=ka | mam-ŋka-ʈum | t̪ama-ja. | Jilele (Murrinh-Patha) |

| [name]=attempt=cst | do.3sg.nfut-eye.appl-dry say.2sg.irr father | |||

| ‘how about Yengkul, the one who stirs up dust in his truck, who you call father?’ (Mansfield 2019, p. 5) | ||||

| (20) | wurran-nintha-lili | (Murrinh-Patha) |

| they.6.PRES-du/m-walk | ||

| 3sgS.go(6).nfut-du.m-walk | ||

| ‘They are walking.’ (Street (1996, p. 208) in Nordlinger and Caudal (2012, p. 83)) | ||

| (21) | mam-purl | (Murrinh-Patha) |

| I.8.PERF-wash | ||

| 1sgS.hands(8).nfut-wash | ||

| ‘I washed it.’ (Street (1996, p. 209) in Nordlinger and Caudal (2012, p. 83)) | ||

| (22) | baŋam-lele-ɖim | ku-weɻe | ku-put ̪ikat=ʈe | (Murrinh-Patha) |

| affect.3sg.nfut-bite-sit.impf | anim-dog | anim-cat=agent | ||

| ‘the cat is biting the dog’ (Mansfield 2019, p. 4) | ||||

| (23) | jungarra | bawa-tha | warmgal-d | (Kayardild) |

| big(NOM) | blow-ACT | wind-NOM | ||

| ‘The wind’s blowing strong.’ (Evans 1995, p. 256) | ||||

| (24) | jirrka-rrnga-maru-tha | kurrka-tha kunawuna-ya | barrngka-y, (Kayardild) | ||

| north-BOUND-VD-ACT | take-ACT child-MLOC | waterlily-MLOC | |||

| kurndaji | jirrkur-ung-ka | mirrayala-th, | Nalkardarrawuru | ||

| sandhill(NOM) | north-ALL-NOM | make-ACT | (name) | ||

| ‘Nalkardarrawuru took the baby waterlilies to the beach to the north (Bentinck Island, from Fowler Island), and made a sandhill way to the north.’ (ibid.) | |||||

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1 | first person (exclusive) | mloc | locative modal case |

| 2 | second person | neut | neuter nominal class |

| 3 | third person | nfut | non-future |

| a | augmented | nom | nominative |

| act | actual | npst | non-past |

| all | allative | pf | phrase-final |

| anim | animate | pl | post-lengthening |

| appl | applicative | poss | possessive |

| caus | causative | pres | present |

| cofs | change-of-state | pro | pronoun |

| compl.act | completed action | pst | past |

| cst | constituent ending | purp | purposive |

| deniz | denizen case | quant | quantitative |

| du | dual | real | realis |

| emph | emphatic | S | subject |

| f | feminine gender | sg | singular |

| impf | imperfective | stype | sentence type |

| inch | inchoative | trm | terminative |

| irr | irrealis | usp | underspecified, phonologically null TAM suffix |

| kin | possessed kin | vd | verbal dative |

| loc | locative | veg | vegetable nominal class |

| m | masculine gender | xtd | prosodic lengthening (phonologically |

| masc | masculine nominal class | extended) |

Appendix A. Annotation Scheme

- Verb root

- Verb gloss

- Aktionsart category = {state; neg(ative) state; transitory state/result state/inchoative state (CofS – a context-sensitive category found in all Australian languages endowed with so-called “inchoative” verb classes / derived verbs, cf. Caudal et al. 2012); activity; iterated activity; bounded activity; bounded iterated activity; inchoative activity; unbounded change-of-state; achievement; iterated achievement; bounded iteration of achievement; hab(itual) achievement; accomplishment; iterated accomplishment; hab(itual) accomplishment; hab(itual) achievement; semelfactive (single atomic event); iterated semelfactive}

- Complex event structure = {CUMulative; AToMic; PLURactional; ATM TEL (telic atomic event); ATM TEL GROUP (group of atomic telic events constituting a non-scalar, complex atom); ATM PREP (atomic event with a preparatory stage); ATM SEM (single atomic semelfactive event); ATM INCH (atomic inchoative event—the underlying Aktionsart is CofS); STATE HABitual; CUM BD ACT (bounded cumulative activity event); CUM BD BD ACT MAX (bounded cumulative event quantified by some overt durative adverbial or other quantifier, or due to the ‘:::’ durative intonation); CUM UBD ACT (unbounded reading of a cumulative, activity event); CUM UBD STATE (unbounded reading of a cumulative, stative event); INCR Q (quantity incrementality—i.e., event involves an incremental theme/patient argument, Dowty (1991)), INCR I (quality incrementality—event is telic and scalar but does not involve an incremental theme/patient argument) (Caudal and Nicolas 2005); PLUR ACT (pluractional activity); PLUR ACH (pluractional achievement); PLUR ACC (pluractional accomplishment); PLUR BD ACH (bounded pluractional achievement); PLUR BD ACC (bounded pluractional accomplishment); HAB ACH (habitual achievement); HAB ACC (habitual accomplishment); ATM SEMelfactive (single event semelfactive, i.e., semelfactive atomic event)}

- Scalarity = {n(on scalar); b(inary scale); open scale; closed max(imal scale); dna (does not apply)}

- Control(ling subject) = {y(es);n(o)}

- Present anchoring in (complex) clause or wider context= {x = unspecified; m = present modifier; i = inflectional present marking}

- Past anchoring in (complex) clause or wider context = {x = unspecified; m = past modifier; t = past tense marking; t >> past tense marking of matrix clause; pctx = wider past context (narrative, or prompt)}

- Aspect quantifier = {x = unspecified; d = durative modifier; i = iteration marker or context; r = reduplication; l = lengthening intonation with durative meaning, especially in the sense of Mailhammer and Caudal (2019); h = habitual context or marker}

- Temporal succession = {c = connective; x = unspecified; it = iteration with micro succession; lli = linear lengthening (bounded on the right, with temporal succession); cons = construction imposes temporal succession; p = parataxis with sequence of events; o = (temporal) overlap; c = connective imposing temporal ordering; clit = temporal clitic; r = resultative; rep = ’once more’ (repeated)}

- Structural context (set of discourse relations introducing the relevant utterance (V1 clause in column O) into context) = {Narration; Background; Backgr(ound) (BackgroundForward, cf. Asher et al. (2007)); Fore(ground)Back(ground) (=BackgroundBackward, ibid.); Argu Epist = argumentative discourse relation with epistemic-inferential function (cf. the SDRT relation Question/Answer Pair); Argu Deon = argumentative jussive discourse relation (order, suggestion) with indicative antecedent utterance/clause/discourse unit; Argu Q/A-P = Question/Answer Pair relation; TempShift = forced temporal shift – with e.g. some ‘then’ clitic/particle}

- Example temporal reading = {past; present}

- TA context = {SoE = sequence of events; PstMod = past modifier; AspMod = aspectual modifier; EpistMod = Epistemic Modifier; PerfMod = perfect modifier; -PST = past inflection;—∅ = zero inflection; -PR = present inflection; -IRR.PST = past irrealis inflection; Coord PST = V-Ø coordinated with V-PST; DiscCon = discourse connective; DiscCon SoE = discourse connective precedes USP segment; SoE-PST (DiscCon/parataxis) = first or previous segment of the SoE is marked in the past; Overlap = temporal overlap (with a backgrounded clause); Overlap-PST = temporal overlap in the past; TempShift = temporal shift context (e.g., discontinuous states); Metalinguistic: metalinguistic context; XTD = durative lengthening (especially linear lengthening intonation); RED = morphological reduplication; RED-echo = full (word) reduplication; Sim = simultaneous events; V = verb; Iter = iteractive predicate; Hab = habitual marker/context; Rel = relative clause; X >> Y = matrix X dominates Y; AspClit = aspectual clitic; PST prompt = past prompt; CausSub = causal subordinate clause; <<: temporal precedence relation; >>: syntactic dominance relation}

- Overt TA pattern = {V1-∅: relevant annotated verb (with zero inflection); V-3/-V-2/V-1/V0-: verbs preceding annotated verb; V+1/V+2+V+3+V+4 = verbs following annotated verb; IRR.PST = past irrealis; PST = past; PR = present; :::= durative lengthening}

- Comment on annotation

- Example in Anindilyakwa

- Example gloss

- Example translation

- Example source

- Example genre (narrative or elicitation (video stimuli, translation ask, or flash card stimuli—speakers were shown flashcards with verb forms and asked to provide an utterance then comment on it)

- Other notes

- different types of incremental, non-atomic telic utterances—i.e., when an incremental, scalar reading gets projected onto the internal structure of some theme/patient argument, we annotated the data point as INCR Q (for quantity incrementality, cf. the object argument of English verb eat), when it does not, we annotated the datapoint as INCR I (for intensity incrementality, cf. the subject argument of English verb ripen);

- different sub-kinds of atomic events: ATM SEM signals single-event readings of normally semelfactive utterances; ATM TEL PREP refers to the class of atomic telic utterances implicating a so-called preparatory stage—cf. English arrive or reach; ATM TEL GROUP refers to atomic events involving plural entities (nominal referents or event referents) treated as a single unit, i.e., a group (such ‘atomic groups’, though plural at some abstract level, effectively contribute to forming a single atomic event; the term was coined after theories of nominal reference à la Link/Landman, see Landman (1989a, 1989b)); ATM INCH refers to inchoative readings of verbs normally ambiguous between stative and change-of-state, inchoative interpretations, due either to special derivational morphology (cf. Aktionsart class CofS), or to a merely contextual inchoative reading of a bona fide atelic (especially stative) verb;

- event plurality/pluractionality (PLUR), vs. habituality (HAB). But most crucial to our study is:

- boundedness (BD) vs. unboundedness (UBD, with BD MAX marking overt maximized duration; BD-marked readings stem from contextual information, e.g., through discourse connectives and discourse relations. BD MAX utterances only appeared with the ‘for a long time’ intonation (:::); no examples with limited duration adverbials were found within our zero tense corpus—but see Bednall (2020) for some examples with past tense marking.

| 1 | Bickerton (1981, p. 84) claims that dynamic utterances systematically trigger a past temporal anchoring for the zero tense in Sranan, while stative utterances receive a (default) present temporal anchoring. |

| 2 | Smith (2006, p. 97) and Smith et al. (2007, p. 61) name it “the Temporal Schema Principle”—but temporal schema in their terminology refers to the aspectual properties of an event, and more specifically to the interaction of aspectual viewpoint with event structural information. The boundedness vs. unboundedness opposition crucially belongs to this notional domain. |

| 3 | See also Giorgi and Pianesi’s (1997, pp. 151–52) ‘punctuality constraint’—where puncutality refers to perfectively viewed events (rather than non-durative events). |

| 4 | De Wit (2016, pp. 124–25) mentions at least one example where a dynamic utterance in Sranan anchors in the present, though, so it is actually unclear how categorical this aspectual parameter is for temporally anchoring the Sranan zero tense. |

| 5 | Where eα/β/etc. is standard SDRT shorthand notation for the event referent underlying segments α/β/etc. |

| 6 | Essentially though, this is because both types of Background relations involve a temporal overlap semantic axiom: ϕBackground(α, β) ⇒ overlap(eβ, eα) |

| 7 | Two types if inchoatively interpreted zero marked-verbs were identified in our corpus: (i) ten verbs bearing an overt morphological marking (effectively alternating between stative and change-of-state meanings, cf. Caudal et al. (2012)), and (ii) five activity verbs with a contextual inchoative reading—four instances of the ‘run’ (-angkarrə-) verb (with a clear ‘run off/away’ inchoative reading and one cognitive process verb (-engkərrka- ‘listen/think’)—again with a clear coerced reading. |

| 8 | Again, in contrast with Backgr(ound), noting so-called BackgroundForward relations in our corpus. |

| 9 | (Un)doundedness obviously relates to other binary features (e.g., homogeneous vs. heterogeneous) widely used as ‘central’ aspectual distinctions in some theories of tense-aspect, from Dowty (1979) to De Swart (1998), including in some some early theories of the relation between aspect and temporal ordering in discourse, as they were grounded on a basic opposition between change-of-state/heterogeneous and non-change-of-state/homogeneous aspectual values, cf. e.g., Dowty (1986). See also the related ontological distinction made in DRT and early SDRT works between ‘stative’ and ‘event’ discourse referents, with imperfective tenses associating with ‘stative’ discourse referents, and perfective tenses with ‘event’ discourse referents, cf. Kamp and Reyle (1993), Asher (1993) and Lascarides and Asher (1993a, 1993b). |

| 10 | We should also stress again that regardless of how they were collected, a large part of our datapoints comprise overt linguistic markers contributing to their aspectuo-temporal and causo-temporal/discourse structural interpretation (e.g., reduplication, linear lengthening, duration phrases, aspectuo-temporal clitics or particles, discourse connectives, and discourse particles or clitics). This is an important safeguard against circular ascriptions of aspectual properties and viewpoint readings, and one we tried to exploit to the full in the individual analysis of each datapoint. |

| 11 | See e.g., https://www.statsdirect.com/help/Default.htm#exact_tests_on_counts/odds_ratio_ci.htm (accessed on 10 November 2021). |

| 12 | On FET and its comparison with the chi-square test, see e.g., Bewick et al. (2004). |

| 13 | The 11 datapoints whose (un)boundedness could not be ascertained will be left aside in the remainder of this paper. |

| 14 | As the present paper focused on the Anindilyakwa zero tense, and the effects of aspectual parameters on its temporal interpretation, we will not discuss any further the precise semantics and pragmatics of the two other indicative tenses found in the language, leaving it to future research as an independent question. |

| 15 | Rather than calculating FET by running the R platform on a personal computer, it is possible to use the online biostatistical tool BiostaTGV (https://biostatgv.sentiweb.fr/?module=tests/fisher, accessed on 13 November 2022) created by the Institut Pierre Louis UMR S 1136 (INSERM/U. Paris-Sorbonne Université). |

| 16 | The corresponding R command is fisher.test(matrix(c(109,7,67,20),2,2, nrow=2)), and yields the same results as the BiostTGV online tool (except for a few decimals). |

| 17 | chisq.test(matrix(c(109,7,67,20), ncol=2)) |

| 18 | In R, fisher.test(matrix(c(164,16,12,11),2,2, byrow=TRUE)) |

| 19 | chisq.test(matrix(c(164,16,12,11), ncol=2)) gives p = 1.222 × 10−06, with X-squared = 23.543, df = 1, but also a warning the Chi-2 approximation may be incorrect. |

| 20 | In R, fisher.test(matrix(c(36,8,12,11),2,2, byrow=TRUE)) |

| 21 | Possibly even non-significant, if we take the value of 0.01 rather than 0.05 as the significance threshold for p. It hinges on how conservative we make our measurements. |

| 22 | fisher.test(matrix(c(157,0,19,27),2,2, byrow=TRUE)) |

| 23 | fisher.test(matrix(c(27,0,0,14),2,2, byrow=TRUE)) yields p = 2.838 × 10−11, an infinite odds ratio, and a 95% confidence interval [46.09243, Inf]. chisq.test(matrix(c(27,0,0,14), ncol=2)) does not fare better—it also results in a warning that the X-squared approximation might be incorrect; it yields X-squared = 36.673, df = 1, p-value = 1.397 × 10−09. |

| 24 | Interestingly, Caudal et al. (2016) also demonstrated that for an unrelated aspectually (but not temporally) underspecified tense, namely the Old French passé simple, boundedness (associated with as definite changeof-state predicate in this work) was a much better predictor of perfective viewpoint meanings than telicity. It is hardly surprising, given that perfective viewpoint functions categorically select for bounded event predicates. |

| 25 | While an anonymous reviewer suggested that Malchukov (2019) offered interesting insights into event structure parameters influencing the temporal interpretation of zero(-)tenses, we feel we must disagree. Malchukov (2019, p. 19) explicitly claims that “there is no direct interaction between actionality and tense here, but the interaction is mediated by the mechanism of default aspect. Indeed, there is no reason to view a combination of a dynamic event and present tense as infelicitous; accomplishments are regularly used in the present tense without restrictions, as it is most clear for languages where aspect is lacking”. Malchukov’s claims directly contradict some of our results, where it appears that zero tense accomplishment utterances are significantly less anchored in the present than in the past, achievement and bounded utterances always anchor in the past, etc. Although determining whether Malchulov’s ‘implicational hiearchy’ could yield interesting generalizations for the temporal interpretation zero tenses is beyond the scope of the present paper, we would also like to point out that said hierarchy is effectively based on an extremely coarse-grained ontology of aspectual types of event predicates. Our annotation results rather seem to suggest that a larger number of aspectual parameters than those underlying Malchulov’s hierarchy might play some role as well in those phenomena—which, we believe, indicates that a simple scale (i.e., a straightforward linear, one-dimensional ordering or aspectual parameters) is maybe not an option: the greater the number of aspectual parameters, the more problematic its linearization on a single dimension is likely to be. But of course, closer scrutiny of such questions must be left to further research—even for Anindilyakwa, for which a larger corpus would be very much necessary to ‘zoom in’ on numerically smaller aspectual classes of event predicates, and the related aspectual parameters. |

| 26 | More specifically, she claims they are anchored to a (past) perfective reading, which she contrasts with a present (imperfective) reading—and thus intuitively appeals to something like the ‘present perfective’ paradox, i.e., perfective entails past. ‘Perfective’ and ‘imperfective’ tenses in Bybee (1990) are explictily connected with bounded vs. unbounded events, which they respectively select (and convey). However, one might wonder how much of the past anchoring effect of dynamicity is in fact due to telic dynamic events in her data, or bounded atelic events – it possibly does not obtain with unbounded atelic dynamic events. |

References

- Alotaibi, Yasir. 2020. Verb Form and Tense in Arabic. International Journal of English Linguistics 10: 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, Nicholas, and Alex Lascarides. 2003. Logics of Conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Asher, Nicholas, Laurent Prévot, and Laure Vieu. 2007. Setting the Background in Discourse. Discours. 1. Available online: http://discours.revues.org/301 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Asher, Nicholas. 1993. Reference to Abstract Objects in Discourse. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Mark, and Lisa Travis. 1997. Mood as Verbal Definiteness in a “Tenseless” Language. Natural Language Semantics 5: 213–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavers, John. 2013. Aspectual classes and scales of change. Linguistics 51: 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Laura. 2022. The Distribution of Zero Forms in Nominal and Verbal Inflection: A Token-Based Approach. Master’s thesis, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany. Available online: https://laurabecker.gitlab.io/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Bednall, James. 2020. Temporal, Aspectual and Modal Expression in Anindilyakwa, the Language of the Groote Eylandt Archipelago, Australia. Ph.D. thesis, 2020, ANU, Canberra, Australia, Université de Paris, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Bednall, James. 2021. Identifying salient Aktionsart properties in Anindilyakwa. Languages 6: 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Michael R., and Barbara H. Partee. 1978. Toward the Logic of Tense and Aspect in English. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club. [Google Scholar]

- Bertinetto, Pier Marco. 2014. Tenselessness in South American indigenous languages with focus on Ayoreo (Zamuco). LIAMES: Línguas Indígenas Americanas 14: 149–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewick, Viv, Liz Cheek, and Jonathan Ball. 2004. Statistics review 8: Qualitative data—tests of association. Critical Care 8: 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bible Society in Australia. 1992. Neningikarrawara-Langwa Ayakwa [=Anindilyakwa Bible]. Canberra: Bible Society in Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Bickerton, Derek. 1975. Dynamics of a Creole System. London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bickerton, Derek. 1981. Roots of Language. Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bittner, Maria. 2005. Future Discourse in a Tenseless Language. Journal of Semantics 22: 339–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, Maria. 2008. Aspectual universals of temporal anaphora. In Theoretical and Crosslinguistic Approaches to the Semantics of Aspect. Edited by Susan Rothstein. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 349–85. [Google Scholar]

- Blaker, Helge. 2000. Confidence Curves and Improved Exact Confidence Intervals for Discrete Distributions. The Canadian Journal of Statistics/La Revue Canadienne de Statistique 28: 783–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochnak, M. Ryan, Vera Hohaus, and Anne Mucha. 2019. Variation in Tense and Aspect, and the Temporal Interpretation of Complement Clauses. Journal of Semantics 36: 407–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochnak, M. Ryan. 2016. Past time reference in a language with optional tense. Linguistics and Philosophy 39: 247–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnemeyer, Jürgen. 2002. The Grammar of Time Reference in Yukatek Maya. München: Lincom Europa. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnemeyer, Jürgen. 2009. Temporal anaphora in a tenseless language. In The Expression of Time. Edited by Wolfgang Klein and Ping Li. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 83–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bras, Myriam, Anne Le Draoulec, and Laure Vieu. 2001. French Adverbial Puis between Temporal Structure and Discourse Structure. In Semantic and Pragmatic Issues in Discourse and Dialogue: Experimenting with Current Dynamic Theories. Edited by Myriam Bras and Laure Vieu. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 109–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, Thuy. 2019. Temporal reference in Vietnamese. In Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Vietnamese Linguistics. Edited by Nigel Duffield, Trang Phan and Tue Trinh. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 115–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan L. 1990. The grammaticization of zero: Asymmetries in tense and aspect. La Trobe Working Papers in Linguistics 3: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan, Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca. 1994. The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect and Modality in the Language of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carolan, Elizabeth. 2015. An Exploration of Tense in Chuj. ScriptUM: La Revue Du Colloque VocUM. Available online: https://scriptum.vocum.ca/index.php/scriptum/article/view/25 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Carroll, Matthew Jay. 2016. The Ngkolmpu Language with Special Reference to Distributed Exponence. Ph.D. thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. Available online: https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/116801 (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Carruthers, Janice. 2005. Oral Narration in Modern French: A Linguistic Analysis of Temporal Patterns. Oxford: Legenda. [Google Scholar]

- Caudal, Patrick, Alan Dench, and Laurent Roussarie. 2012. A semantic type-driven account of verb-formation patterns in Panyjima. Australian Journal of Linguistics 32: 115–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudal, Patrick, and David Nicolas. 2005. Types of degrees and types of event structures. In Event Arguments: Foundations and Applications. Edited by Claudia Maienborn and Angelika Wöllstein. Tübingen: Niemeyer, pp. 277–300. [Google Scholar]

- Caudal, Patrick, and Gerhard Schaden. 2005. Discourse-Structure Driven Disambiguation of Underspecified Semantic Representations: A case-study of the Alemannic Perfekt. In Proceedings/Actes SEM-05, First International Symposium on the Exploration and Modelling of Meaning. Edited by Michel Aurnague, Myriam Bras, Anne Le Draoulec and Laure Vieu. Toulouse: Université de Toulouse le Mirail. [Google Scholar]

- Caudal, Patrick, Heather Burnett, and Michelle Troberg. 2016. Les facteurs de choix de l’auxiliaire en ancien français: étude quantitative. In Le Français en Diachronie. Dépendances Syntaxiques, Morphosyntaxe Verbale, Grammaticalisation. Edited by Sophie Prévost and Benjamin Fagard. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 237–65. [Google Scholar]

- Caudal, Patrick, Robert Mailhammer, and James Bednall. 2019. A comparative account of the Iwaidja and Anindilyakwa modal systems. Paper presented at the ALW2019 (Australian Languages Workshop), Marysville, VIC, Australia, March 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Caudal, Patrick. 1999. Computational Lexical Semantics Incrementality And The So-Called Punctuality Of Events. Paper presented at the 37th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics on Computational Linguistics, College Park, MD, USA, June 20–26; Stroudsburg: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 497–504. Available online: http://clair.eecs.umich.edu/aan/paper.php?paper_id=P99-1064 (accessed on 14 January 2016).

- Caudal, Patrick. 2010. Tense switching in French oral narratives. In The “Conte”—Oral and Written Dynamics. Edited by Janice Carruthers and Maeve McCusker. Oxford: Peter Lang, pp. 235–60. [Google Scholar]

- Caudal, Patrick. 2012. Pragmatics. In The Oxford Handbook of Tense and Aspect. Edited by Robert Binnick. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 269–305. [Google Scholar]

- Caudal, Patrick. 2015. Uses of the passé composé in Old French: Evolution or revolution? In Sentence and Discourse. Edited by Jacqueline Guéron. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 178–205. [Google Scholar]

- Caudal, Patrick. 2023. On so-called ‘tense uses’ in French as context-sensitive constructions. In Tense, Aspect and Discourse Structure. Edited by Martin Becker and Jakob Egetenmeyer. Berlin: De Gruyter. 20p. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Sherry Yong, and E. Matthew Husband. 2018. Contradictory (forward) lifetime effects and the non-future tense in Mandarin Chinese. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 3: 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, David. 1989. L’aspect Verbal. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, Colette Grinevald. 1977. The Structure of Jacaltec. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Mulder, Walter, and Carl Vetters. 1999. Temps verbaux, anaphores (pro)nominales et relations discursives. Travaux de linguistique 39: 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- De Swart, Henriëtte. 1998. Aspect Shift and Coercion. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 16: 347–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, Astrid, and Frank Brisard. 2014. Zero verb marking in Sranan. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 29: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, Astrid. 2016. The Present Perfective Paradox across Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denny, Stacy, and Korah Belgrave. 2013. Barbadian Creole English. In The Mouton World Atlas of Variation in English. Edited by Berndt Kortmann and Kerstin Lunkenheimer. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies & Australian National University. 2020. National Indigenous Languages Report 2020; Canberra: Australian Government. Available online: https://www.arts.gov.au/what-we-do/indigenous-arts-and-languages/national-indigenous-languages-report (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Depraetere, Ilse. 1995. On the necessity of distinguishing between (un)boundedness and (a)telicity. Linguistics and Philosophy 18: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowty, David. 1979. Word Meaning and Montague Grammar: The Semantics of Verbs and Times in Generative Semantics and Montague’s PTQ. Dordrecht: Reidel. [Google Scholar]

- Dowty, David R. 1986. The Effects of Aspectual Class on the Temporal Structure of Discourse: Semantics or Pragmatics? Linguistics and Philosophy 9: 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowty, David. 1991. Thematic Proto-Roles and Argument Selection. Language 67: 547–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, Nigel. 2007. Aspects of Vietnamese clausal structure: Separating tense from assertion. Linguistics 45: 765–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, Nora C. 1983. A Grammar of Mam, A Maya Language. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Nicholas. 1995. A Grammar of Kayardild. With Historical-Comparative Notes on Tangkic. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Nicholas, and Honoré Watanabe, eds. 2016. Insubordination. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Fay, Michael P. 2010. Confidence intervals that match Fisher’s exact or Blaker’s exact tests. Biostatistics 11: 373–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortescue, Michael. 2016. Polysynthesis: A Diachronic and Typological Perspective. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford: Interactive Factory. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, Alessandra, and Fabio Pianesi. 1997. Tense and Aspect: From Semantics to Morphosyntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Mark. 2017. Non-Pama-Nyungan Languages: Mapping Database and Maps. ASEDA. [Google Scholar]

- Haspelmath, Martin. 2021. Explaining grammatical coding asymmetries: Form–frequency correspondences and predictability. Journal of Linguistics 57: 605–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, Paul J. 1979. Aspect and foregrounding in discourse. In Discourse and Syntax. Syntax and Semantics 12. Edited by Talmy Givón. New York: Academic Press, pp. 213–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp, Hans, and Uwe Reyle. 1993. From Discourse to Logic. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Christopher, and Louise McNally. 2005. Scale Structure, Degree Modification, and the Semantics of Gradable Predicates. Language 81: 345–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Christopher. 2012. The composition of incremental change. In Telicity, Change, and State: A Cross-Categorial View of Event Structure. Edited by Violeta Demonte and Louise McNally. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 103–38. [Google Scholar]

- Landman, Fred. 1989a. Groups, II. Linguistics and Philosophy 12: 723–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, Fred. 1989b. Groups, I. Linguistics and Philosophy 12: 559–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascarides, Alex, and Jon Oberlander. 1993. Temporal Connectives in a Discourse Context. Paper presented at Sixth Conference on European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (EACL ’93), Utrecht, The Netherlands, April 19–23; Stroudsburg: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 260–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lascarides, Alex, and Nicholas Asher. 1993a. Temporal Interpretation, Discourse Relations and Commonsense Entailment. Linguistics and Philosophy 16: 437–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascarides, Alex, and Nicholas Asher. 1993b. A Semantics and Pragmatics for the Pluperfect. Stroudsburg: Association for Computational Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jungmee, and Judith Tonhauser. 2010. Temporal Interpretation without Tense: Korean and Japanese Coordination Constructions. Journal of Semantics 27: 307–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Jo-Wang. 2003. Temporal Reference in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 12: 259–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Jo-wang. 2010. A Tenseless Analysis of Mandarin Chinese Revisited: A Response to Sybesma 2007. Linguistic Inquiry 41: 305–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailhammer, Robert, and Patrick Caudal. 2019. Linear Lengthening Intonation in English on Croker Island: Identifying substrate origins. JournaLIPP 6: 40–56. [Google Scholar]

- Malchukov, Andrej L. 2019. Interaction of Verbal Categories in a Typological Perspective. GENGO KENKYU 156: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Malchukov, Andrej. 2009. Incompatible Categories: Resolving the “Present Perfective Paradox”. In Cross-Linguistic Semantics of Tense, Aspect, and Modality. Edited by Lotte Hogeweg, Helen de Hoop and Andrej Malchukov. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, John. 2019. Murrinhpatha Morphology and Phonology. Murrinhpatha Morphology and Phonology. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Fabienne. 2019. Non-culminating accomplishments. Language and Linguistics Compass 13: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthewson, Lisa. 2006. Temporal semantics in a superficially tenseless language. Linguistics and Philosophy 29: 673–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molendijk, Arie, and Henriëtte de Swart. 1999. L’ordre discursif inverse en français. Travaux de linguistique 39: 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mucha, Anne. 2012. Temporal reference in a genuinely tenseless language: The case of Hausa. Semantics and Linguistic Theory 22: 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, Anne. 2013. Temporal interpretation in Hausa. Linguistics and Philosophy 36: 371–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, Léa. 2017. The Structural Source of Split Ergativity and Ergative Case in Georgian. In The Oxford Handbook of Ergativity. Edited by Jessica Coon, Diane Massam and Lisa deMena Travis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, Atsuko, and Jean-Pierre Koenig. 2010. What is a perfect state? Language 86: 611–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlinger, Rachel, and Patrick Caudal. 2012. The tense, aspect and modality system in Murrinh-Patha. Australian Journal of Linguistics 32: 73–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofuani, Ogo A. 1984. On the Problem of Time and Tense in Nigerian Pidgin. Anthropological Linguistics 26: 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Pancheva, Roumyana, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta. 2020. Temporal reference in the absence of tense in Paraguayan Guaraní. In NELS 50: Proceedings of the Fiftieth Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society: October 25–27, 2019, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Edited by Mariam Asatryan, Yixiao Song and Ayana Whitmal. Cambridge: GLSA, University of Massachussets/Amherst. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, Elizabeth, and Martina Wiltschko. 2014. The composition of INFL: An exploration of “tense, tenseless” languages, and “tenseless” constructions. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 32: 1331–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ritz, Marie-Eve, and Eva Schultze-Berndt. 2015. Time for a change? The semantics and pragmatics of marking temporal progression in an Australian language. Lingua 166: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Round, Erich R. 2013. Kayardild Morphology and Syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schultze-Berndt, Eva. 2012. Pluractional Posing as Progressive: A Construction between Lexical and Grammatical Aspect. Australian Journal of Linguistics 32: 7–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuren, Pieter A. M. 2001. A View of Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shaer, Benjamin. 2003. Toward the tenseless analysis of a tenseless language. In Proceedings of SULA 2. Edited by Jan Anderssen, Paula Meéndez-Benito and Adam Werle. Amherst, MA: GLSA, pp. 139–56. [Google Scholar]

- Singler, John Victor, ed. 1990. Pidgin and Creole Tense-mood-aspect Systems. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Carlota. 2006. The Pragmatics and Semantics of Temporal Meaning. In Proceedings of the 2004 Texas Linguistics Society Conference: Issues at the Semantics-Pragmatics Interface. Edited by Pascal Denis, Eric McCready, Alexis Palmer and Brian Reese. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla, pp. 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Carlota S. 2008. Time With and Without Tense. In Time and Modality (Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory). Edited by Jacqueline Guéron and Jacqueline Lecarme. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 227–49. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Carlota S., and Mary S. Erbaugh. 2005. Temporal interpretation in Mandarin Chinese. De Gruyter Mouton 43: 713–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Carlota S., Ellavina T. Perkins, and Theodore B. Fernald. 2007. Time in Navajo: Direct and Indirect Interpretation. International Journal of American Linguistics 73: 40–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, Thomas, and Nataliya Levkovych. 2019. Absence of material exponence: A newcomer to the domain of non-canonicity. STUF—Language Typology and Universals De Gruyter (A) 72: 373–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, Chester S. 1996. Tense, aspect and mood in Murrinh-Patha. In Studies in Kimberley languages in Honour of Howard Coate. Edited by William McGregor. München: Lincom Europa, pp. 205–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali A., and Shana Poplack. 1993. The Zero-Marked Verb: Testing the Creole Hypothesis. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 8: 171–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonhauser, Judith. 2006. The Temporal Semantics of Noun Phrases: Evidence from Guarani. Ph.D. thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. Available online: http://lear.unive.it/jspui/handle/11707/4289 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Tonhauser, Judith. 2011. Temporal reference in Paraguayan Guaraní, a tenseless language. Linguistics and Philosophy 34: 257–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonhauser, Judith. 2015. Cross-Linguistic Temporal Reference. Annual Review of Linguistics 1: 129–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toosarvandani, Maziar. 2021. Encoding Time in Tenseless Languages: The View from Zapotec. In Proceedings of the 37th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Edited by D. K. E. Reisinger and Marianne Huijsmans. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 21–41. Available online: http://www.lingref.com/cpp/wccfl/37/abstract3512.html (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Vendler, Zeno. 1957. Verbs and Times. The Philosophical Review 6: 143–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winford, Donald. 2000. Tense and Aspect in Sranan and the Creole Prototype. In Language Change and Language Contact in Pidgins and Creoles. Edited by John H. McWhorter. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 383–442. [Google Scholar]

- Yakpo, Kofi. 2019. A Grammar of Pichi. Language Science Press. Berlin: Language Science Press. [Google Scholar]

| Portmanteau Prefix | TAM Suffix |

|---|---|

| Realis | non-past |

| past | |

| underspecified (Ø) | |

| irrealis | non-past |

| past | |

| underspecified (Ø) | |

| potential | |

| imperative/hortative | non-past |

| underspecified (Ø) | |

| potential |

| Temporal Anchoring | States | Activites + Accomplishments | Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Past | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Present | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Data Type | Audio Duration | Word Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elicited data (translation tasks; stimuli-prompts) | 15 h 16 min 25 s | 19,906 | 81.60% |

| Spoken narratives | 01 h 04 min 46 s | 3789 | 15.53% |

| Translated text (Bible) | - | 699 | 2.87% |

| TOTAL | 16 h 21 min 11 s | 24,394 |

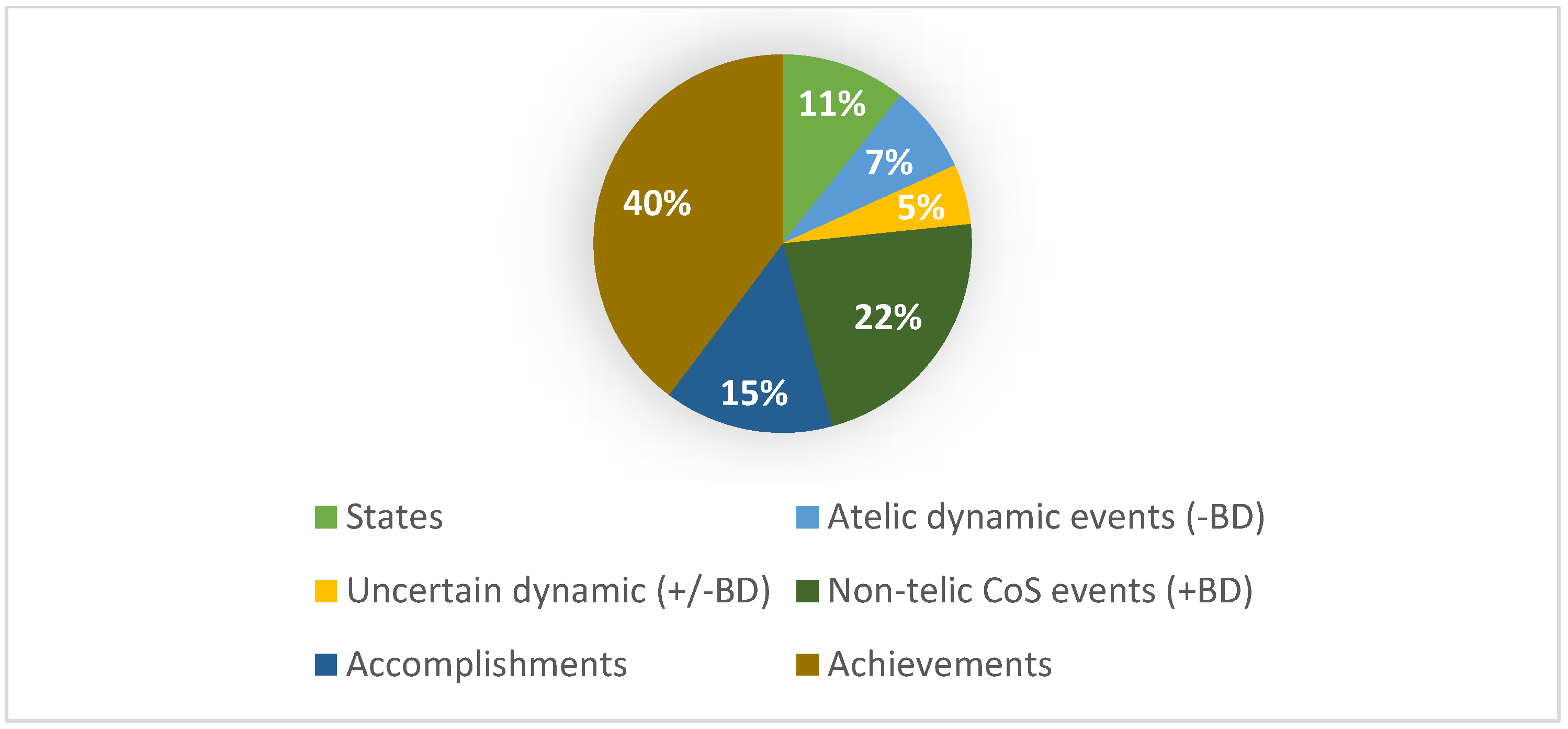

| Event Structure Class | Number of Verb Forms | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| States (-BD) | 23 | 10.75% |

| Atelic dynamic events (-BD) | 16 | 7.48% |

| Uncertain dynamic (+/-BD) | 11 | 5.14% |

| Non-telic change-of-state events (+BD) | 48 | 22.43% |

| Non-atomic telic (Accomplishments) (+BD) | 31 | 14.49% |

| Atomic telic (Achievements) (+BD) | 85 | 39.72% |

| Total | 214 |

| Event Structure Class | Number of Verb Forms | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| States | 10 | 45.45% |

| Atelic dynamic events | 12 | 54.55% |

| Non-telic change-of-state events | 0 | 0.00% |

| Non-atomic telic (Accomplishments) | 0 | 0.00% |

| Atomic telic (Achievements) | 0 | 0.00% |

| Total | 22 |

| Event Structure Class | Number of Verb Forms | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| States | 7 | 6.93% |

| Atelic dynamic events | 21 | 20.79% |

| Non-telic change-of-state events | 37 | 36.63% |

| Accomplishments | 6 | 5.94% |

| Achievements | 30 | 29.70% |

| Total | 101 |

| Event Structure Opposition | Past | Present | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telic | 109 | 7 | 116 |

| non-telic (CUM + CoS non telic) | 67 | 20 | 87 |

| Total | 176 | 27 | 203 |

| Event Structure Opposition | Past | Present | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telic atomic (achievement) | 85 | 0 | 85 |

| Telic non-atomic (accomplishment) | 24 | 7 | 31 |

| Total | 109 | 7 | 116 |

| Event Structure Opposition | Past | Present | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic | 164 | 16 | 180 |

| Stative | 12 | 11 | 23 |

| Total | 176 | 27 | 203 |

| Event Structure Opposition | Past | Present | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic atelic | 36 | 8 | 44 |

| Stative | 12 | 11 | 23 |

| Total | 48 | 19 | 67 |

| Event Structure Opposition | Past | Present | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| BD | 157 | 0 | 157 |

| UBD | 19 | 27 | 46 |

| Total | 176 | 27 | 203 |

| Event Structure in Empty Context | Past | Present | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| BD | 27 | 0 | 27 |

| UBD | 0 | 14 | 14 |

| Total | 27 | 14 | 41 |

| Parameter | Significance (p) | Odds Ratio | Confidence INTERVAL (95%) | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD/UBD | 1.3771954740868 × 10−21 | INF | [49.30634; Inf] | 1 |

| Telic/non-telic | 2.987 × 10−09 | 3.085 | [5.575388; 51.268209] | 2 |

| Dynamic/stative | 1.4465429919578 × 10−5 | 9.2173 | [3.1515; 27.261] | 3 |

| Dynamic atelic/stative | 0.02067 | 4.026621 | [1.168114; 14.715856] | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caudal, P.; Bednall, J. Aspectuo-Temporal Underspecification in Anindilyakwa: Descriptive, Theoretical, Typological and Quantitative Issues. Languages 2023, 8, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010008

Caudal P, Bednall J. Aspectuo-Temporal Underspecification in Anindilyakwa: Descriptive, Theoretical, Typological and Quantitative Issues. Languages. 2023; 8(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaudal, Patrick, and James Bednall. 2023. "Aspectuo-Temporal Underspecification in Anindilyakwa: Descriptive, Theoretical, Typological and Quantitative Issues" Languages 8, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010008

APA StyleCaudal, P., & Bednall, J. (2023). Aspectuo-Temporal Underspecification in Anindilyakwa: Descriptive, Theoretical, Typological and Quantitative Issues. Languages, 8(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010008