Abstract

Light Warlpiri is a newly emerged Australian mixed language that systematically combines nominal structure from Warlpiri (Australian, Pama-Nyungan) with verbal structure from Kriol (an English-lexified Creole) and English, with additional innovations in the verbal auxiliary system. Lexical items are drawn from both Warlpiri and the two English-lexified sources, Kriol and English. The Light Warlpiri verb system is interesting because of questions raised about how it combines elements of its sources. Most verb stems are derived from Kriol or English, but Warlpiri stems also occur, with reanalysis, and stems of either source host Kriol-derived transitive marking (e.g., hit-im ‘hit-TR’). Transitive marking is productive but also variable. In this paper, we examine transitivity and its marking on Light Warlpiri verbs, drawing on narrative data from an extensive corpus of adult speech. The study finds that transitive marking on verbs in Light Warlpiri is conditioned by six of Hopper and Thompson’s semantic components of transitivity, as well as a morphosyntactic constraint.

1. Introduction

Transitivity is the degree to which an action is carried over or transferred from one participant in an event to another (Hopper and Thompson 1980, p. 253). It is an essential component of argument structure and verbal semantics across languages. The foundational work of Hopper and Thompson (1980) described a cline of semantic components of transitivity. These components contribute to the categorization of an event as high or low in transitivity. Hopper and Thompson (1980) hypothesized that the contribution of the semantic components co-varies systematically with grammatical marking of transitivity across languages, an idea called the Transitivity Hypothesis.

Questions of verb marking and transitivity in the Australian mixed language Light Warlpiri are especially interesting because Light Warlpiri verb structure is a combination of elements from three source languages, which differ in how transitivity is marked. The source languages are Warlpiri, a Pama-Nyungan language; Kriol, an English-lexified Creole; and varieties of English. Specifically, Warlpiri indicates transitivity through ergative case-marking on overt transitive subject arguments; Kriol indicates transitivity through the variable application of affixes on transitive verbs; and Standard Australian English indicates transitivity through the presence of overt object nominals or pronominals in transitive clauses, most often in AVO word order. Some varieties of English spoken by Indigenous speakers, known collectively as varieties of Aboriginal English, may also employ a Kriol-derived transitive marker on transitive verbs.

| 1a | Wi | bugi | nganayi-nga1 | kriik-nga. | |

| 1PL.S | swim | you.know-LOC | creek-LOC | ||

| “We swim in you know, in the creek”. | |||||

| 1b | Nait-taim | wi-m | bugi. | ||

| night-time | 1PL.S-NFUT | swim | |||

| “We swam at night”. | |||||

| 1c | Bat | kiwinyi-ng | i-m | bait-im | us. |

| DISJ | mosquito-ERG | 2SG.S-NFUT | bite-TR | 1PL.O | |

| “But mosquitoes bit us”. | |||||

| (ELICIT _LAC58_2015) | |||||

In the examples, elements from Warlpiri are in italics, and elements from English and Kriol are in plain font. To discuss marking on core arguments of verbs, we use the distinction drawn by Dixon (1979) between A arguments (agentive arguments of transitive verbs), O arguments (non-agentive arguments of transitive verbs) and S arguments (arguments of intransitive verbs). As shown in example 1, Light Warlpiri combines verbal structure from Kriol, including variable presence of the Kriol-derived transitive marker -im (as in bait-im ‘bite-TR’), with nominal structure from Warlpiri, including the ergative case marker -ng on overt A arguments, optionally applied. In examples (1a, b), the intransitive verb is Kriol bugi ‘swim’. The verbal complex also shows the influence of both English and Warlpiri (O’Shannessy 2013).

The variation in transitive marking on verbs, along with the ways the source languages of Light Warlpiri combine, raise the questions of how transitivity is marked in Light Warlpiri and how the variability in transitive marking in Light Warlpiri is conditioned. Light Warlpiri is known to combine source language features in surprising ways, for example, with a near-maximal inventory of plosive consonants (Bundgaard-Nielsen and O’Shannessy 2021), and a near-maximal inventory of reflexive and reciprocal marking (O’Shannessy and Brown 2021); so it is not straightforward to predict the influence of each of the source languages of Light Warlpiri in this domain.

In this paper, we describe and analyze variable transitive marking in Light Warlpiri, and ask if the semantic components of Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) cline of transitivity condition the presence of the transitive markers. The next section gives an overview of research on variable transitive marking in other contact languages in Australia, including Kriol and contact languages where reflexes of the Kriol transitive markers are found. Section 3 gives some background on Light Warlpiri, and how transitivity is indicated in its source languages. Section 4 describes the methods of this study, and Section 5 the findings. We discuss these and conclude in Section 6.

2. Variable Transitive Marking in Contact Languages in the Area

The Transitivity Hypothesis claims that ten features affect the degree of transitivity of a clause, and that a clause with more of these features present will more often be overtly marked as transitive, for instance, through morphological marking (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Hopper and Thompson’s ten components of transitivity.

For the current study, we adapt Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) components slightly, by choosing the aspectual distinction of progressive vs. nonprogressive, rather than telic vs. atelic. There is discussion about the connection between telicity, perfectivity and progressiveness (e.g., Declerck 2007; Guéron 2008), where a telic event is often also perfective and nonprogressive (e.g., Hopper and Thompson 1980, p. 262). In this study, our coding of aspect is specifically in terms of a verb being marked as progressive or not, so for transparency, we make the aspectual distinction of progressive vs. nonprogressive. This distinction appears to align with that of telic vs. atelic in the other studies reported on.

Meyerhoff (1996) explored variable transitive marking in 386 transitive clauses from five contact varieties in the South Pacific (Meyerhoff 1996, p. 60). Two of the languages are Australian: Kriol and Yumplatok (referred to as Broken), spoken in Australia’s Torres Strait. The other three languages are Tok Pisin (Papua New Guinea), Bislama (Vanuatu), and Pijin (Solomon Islands). These five languages are referred to as Contact Englishes; however, in this paper, we consider them to be English-lexified contact languages. For each one, the lexifier English varieties were those spoken in north east Australia at the time of language emergence. Verbs coded as higher in transitivity were marked with the transitive affix more often (Meyerhoff 1996, p. 69). The features of Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) components of transitivity that had the highest correlations with the presence of the transitive affix were number of participants, O affectedness, punctuality, aspect and mood. Interestingly, the presence of the transitive affix correlated with irrealis mood, not realis mood, contrasting with Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) hypothesis (Meyerhoff 1996, p. 72); furthermore, kinesis was not found to correlate with transitive marking.

These ideas were developed further by Batchelor (2017) in a study of Barunga Kriol, which examined 441 tokens of syntactically transitive Kriol verbs (i.e., with two or more participants) in recorded interviews. Firstly, the verb stems were coded ‘always marked’, ‘never marked’, or ‘variable’, based on how frequently the transitive suffix was present on a particular stem: e.g., kil (to kill or hit) was always marked with -im, while lisin (to listen) was never marked (Batchelor 2017, pp. 32–33). Secondly, verb tokens were coded as having ‘high’ or ‘low’ transitivity for each component in Hopper and Thompson’s transitivity cline (Batchelor 2017, pp. 29–30). These were then analyzed quantitatively using a single-level mixed effects model. Qualitative, discourse-functional features were also considered for each token (Batchelor 2017, p. 31).

Like the previous studies of English-lexified contact languages, ‘high’ value variables from Hopper and Thompson correlated with a higher frequency of the transitive suffix. For example, verb stems coded with a high level of kinesis had overt transitive marking 80.2% of the time, while stems with low kinesis had overt marking 18.8% of the time (Batchelor 2017, p. 35). Kinesis (80.2%) and affectedness of O (84.5%) had the strongest correlations, followed by volitionality (52.3%) and agency of A (53.1%). The single-level mixed effects model confirmed that kinesis and affectedness of O, followed by volitionality and agency, were the best predictors of transitive marking. The remaining features were not statistically significant predictors, even when correlations were found with transitive marking (Batchelor 2017, p. 36).

S. Dixon (2017) investigated variable transitive marking in another English-lexified contact language in Australia, Alyawarra English, spoken in a remote community in the Northern Territory. A corpus of 252 transitive present tense clauses in data recorded in the children’s home context was examined for the features of Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) components of transitivity. The transitive affix was always present in clauses with unexpressed O arguments and when the event was iterative and marked with the Kriol-derived iterative affix -bat. The affix was never present in progressive clauses marked with the English-derived progressive marker -ing, or when the O argument was expressed by pronominal it ‘3SG.O’. A multivariate analysis found that, among Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) components of transitivity, the most influential features were kinesis, aspect, punctuality, volitionality and object individuation. With the exception of kinesis, these features correlate with the presence of the transitive affix in a manner similar to that reported by Meyerhoff (1996) for five other contact languages. These studies did not try to control for the frequency of the verb type in their statistical models, leaving open the possibility that the effects that they found may have been driven by one or a few high-frequency verbs.

3. Light Warlpiri: Background

3.1. Structure of Light Warlpiri

Light Warlpiri is an Australian mixed language that combines verbal structure from Kriol and varieties of English with nominal structure from Warlpiri and a number of unique innovations (O’Shannessy 2005, 2013).

| 2. | Karnta-pawu-ng | an | wati-ng | de-m | jeis-im |

| woman-DIM-ERG | CONJ | man-ERG | 3PL.S-NFUT | chase-TR | |

| uus | geit-kirra. | ||||

| horse | gate-ALL | ||||

| “A woman and man chased a horse to the gate”. | |||||

| (ERGStory_LA21_2_2004) | |||||

Example 2 shows lexicon from both Warlpiri (karnta-pawu ‘woman-DIM’, wati ‘man’) and English/Kriol (jeis ‘chase’, geit ‘gate’). Warlpiri ergative case-marking is present on the A argument (karnta-pawu-ng and wati-ng), and Warlpiri allative marking also appears (gate-kirra ‘gate-ALL’). The Kriol-derived transitive affix -im ‘TR’ occurs on the transitive verb jeis ‘chase’. An innovative auxiliary construction de-m ‘3PL.S-NFUT’ is present (O’Shannessy 2013).

| 3. | Wi-m | teik | dem | kurdu-kurdu | raid-ik | Tana-ping. |

| 1PL.S-NFUT | take | 3PL.O | child-REDUP | ride-DAT | name-ASSOC | |

| “We took the children, Tana and her friends, for a ride”. | ||||||

| (Elicitation_LA21_C58_2014) | ||||||

Example 3 shows a transitive verb from English and/or Kriol (teik ‘take’) with no transitive affix, showing the variable application of the affix. Warlpiri dative case-marking is present on the English and/or Kriol-derived word raid ‘ride’, and a Warlpiri-derived associative affix -ping ‘ASSOC’ (a contraction of Warlpiri -pinki ‘ASSOC’) appears on a proper noun. The innovative auxiliary is seen in wi-m ‘1PL.S-NFUT’.

| 4. | Jinta-kari-ji | i-m | pantirn-im | jilkarla-ngu | wirliya |

| one-other-TOP | 1SG.S-NFUT | pierce-TR | thorn-ERG | leg | |

| “A thorn pierced the other one on the leg”. | |||||

| (ERGstory_LA91_2015) | |||||

Example 4 shows a Warlpiri-derived verb stem, pantirn ‘pierce’, hosting a Kriol-derived transitive affix -im ‘TR’. In Warlpiri, the verb stem is panti ‘pierce’, which hosts a non-past tense suffix -rni ‘NPAST’. In Light Warlpiri, the final vowel is deleted and the transitive affix is applied, creating a new stem, pantirn ‘pierce’ plus the transitive affix -im ‘TR’.

| 5. | Jalang | wi-m | go | kriik-kirra | kurdu-kurdu-kurl. |

| today | 1PL.S-NFUT | go | creek-ALL | child-REDUP-COM | |

| “Today we went to the creek with the children”. | |||||

| (Elicitation_LA21_C58_2014) | |||||

An intransitive clause is given in example 5, in which the verb go ‘go’ has no transitive affix, as expected.

As shown in examples 1 to 4, Warlpiri supplies nominal morphology and considerable amounts of lexicon to Light Warlpiri. Kriol provides the verb structure through the presence of a Kriol-derived transitive affix on verbs, seen in examples 1 and 3. Light Warlpiri verb stems can be of Kriol/English or Warlpiri origin; the transitive affixes appear on stems from both sources. Light Warlpiri also shows innovations in the verbal auxiliary system that can be traced to new combinations of source language features (O’Shannessy 2013), as seen in example 2.

The question of how Light Warlpiri can be a mixed language but have more than two source languages is answered by the observation that the three source languages can be grouped into two categories, as in Table 2.

Table 2.

How the three source languages of Light Warlpiri are categorized into two groups.

As shown in Table 2, although English and Kriol are two separate languages with very different social histories, in comparison with Warlpiri they have some attributes in common, and in terms of their influences on Light Warlpiri they can be grouped together. We can think of the three source languages of Light Warlpiri as being either Warlpiri-lexified (Warlpiri), or English-lexified (English and Kriol).

Issues of transitivity in Light Warlpiri are especially interesting because the three source languages mark transitivity differently, raising the question of how these differences will be resolved in the mixed language. In the next section, we describe transitivity in the source languages, Warlpiri, Kriol and English.

3.2. Transitivity Marking in the Source Languages of Light Warlpiri

3.2.1. Transitivity Marking in Warlpiri

In Warlpiri, verbs are either transitive, as in example 6, or intransitive, as in example 7.

| 6. | wati-ngki | kurdu-ngku | karnta-ngku |

| man-ERG | child-ERG | woman-ERG | |

| ka-lu | ma-ni | watiya | |

| PRES-3PL.S | get-NPST | tree. | |

| “The man, child and woman get the tree”. | |||

| (ERGstory_WA42) | |||

| 7. | Ngati-nyanu | an | kurdu-jarra | maliki-jarra |

| mother-REFL | CONJ | child-DUAL | dog-DUAL | |

| nyina-mi | ka-lu | warlu-wana. | ||

| sit-NPST | PRES-3PL.S | fire-PERL | ||

| “The mother, two children and two dogs sit by the fire”. | ||||

| (ERGstory_YWA01_2010) | ||||

Transitive verbs can be formed by the use of a preverb and a causative inflecting verb, as in (8), and intransitive verbs can be formed by the use of a preverb and an inchoative inflecting verb, as in (9).

| 8. | Karnta-ngu | ka | pushi-ma-ni | |

| woman-ERG | PRES | push-CAUS-NPST | ||

| wirriya-wita-pardu. | ||||

| boy-small-DIM | ||||

| “A woman is pushing a small boy”. | ||||

| (ERGstoryWWA06_2010) | ||||

| 9. | Wati | manu | karnta-pala | |

| man | CONJ | woman-DUAL | ||

| wardinyi-jarri-ja | nantuwu-ku. | |||

| happy-INCHO-PST | horse-DAT | |||

| “The man and woman became happy about the horse”. | ||||

| (ERGstoryNWA03_2010) | ||||

Transitivity is also indicated through an ergative–absolutive case-marking system on nominals (e.g., Hale 1982; Hale et al. 1995). A arguments are marked with an ergative case-marker, as in 8 (-ngu ‘ERG’). The ergative case marker has allomorphy conditioned by the length of the verb stem and vowel harmony with the final vowel of the stem, although this constraint is being relaxed somewhat in the usage of younger speakers. Absolutive case is null-marked. This is summarized in in Table 3.

Table 3.

Core arguments and case-marking in Warlpiri.

The ergative marker may be omitted on first and second person pronouns that occur before a verb (Bavin and Shopen 1985), but it is obligatory for other transitive clauses with an overt A argument. Note, however, that in Warlpiri, core arguments need not be overt, when their referents can be recovered anaphorically from the discourse (Swartz 1991; Hale 1982, 1992; Simpson and Mushin 2008). If there is no overt A argument, then ergative case-marking cannot be present.

While Warlpiri nominals are marked in an ergative–absolutive pattern, as seen in 8 and 9, bound pronouns in the auxiliary are marked in a nominative–accusative pattern, as in 10 (with some exceptions).

| 10. | puluku | manu | nantuwu | ka-pala | wapa-nja-ya-ni |

| cow | CONJ | horse | PRES-DUAL | walk-INF-go-NPST | |

| kuja | ka-lu-jana | nya-nyi | wati-ngki | manu | |

| REL | PRES-3PL.S-3PL.O | see-NPST | man-ERG | CONJ | |

| karnta-ngku | manu | kurdu-wita-ngku | |||

| woman-ERG | CONJ | child-small-ERG | |||

| “The cow and horse walk along when the man, woman and child see them”. | |||||

| (ERGstoryYWA03_2010) | |||||

In example 10, in ka-lu-jana ‘PRES-3PL.S-3PL.O’, the A and O arguments are referenced in the auxiliary in nominative–accusative (AO) order.

3.2.2. Transitivity Marking in Kriol

Kriol is spoken by many Indigenous people in northern Australia. It combines a mostly English-derived lexicon with grammatical and phonological attributes of Pama-Nyungan and non-Pama-Nyungan languages (Schultze-Berndt et al. 2013; Sandefur 1979, 1986). Most relevant to Light Warlpiri, transitive verbs are variably marked with either -im ‘TR’ or -it ‘TR’. The Kriol transitive markers originated from the reanalysis of English third-person accusative pronouns (‘him’, ‘them’, ‘it’) as transitive markers in Australian Pidgin, which were then retained in varieties of Kriol (Koch 2000). The reanalysis was likely influenced by traditional Indigenous languages, many of which have a morphological transitivity distinction, often through ergative marking on A arguments, as in Warlpiri.

As noted earlier, Batchelor (2017) examined the transitive suffix -Vm (where V is a vowel that varies phonologically) in Barunga Kriol. The presence of -Vm varies widely, from being always present on certain verb stems, to being variably present or always absent on others. In predicting whether the -Vm suffix will be present on a verb, the ‘high’ values of Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) components of transitivity all lead to a greater likelihood of transitive marking than their ‘low’ values. However, only kinesis, affectedness of O, volitionality and agency of A were found to be statistically significant (Batchelor 2017, p. 36). Among these, kinesis and affectedness of O were noticeably stronger predictors (80.2% and 84.5% correlation with -Vm marking, respectively) than volitionality and agency of A (52.3% and 53.1%, respectively).

3.2.3. Transitivity Marking in English

Transitivity in English is not morphologically marked on the verb, but is syntactically visible. English transitivity is seen in the number of participants; the type of pronoun, if used (e.g., the subject ‘she’ and object ‘her’); and word order (e.g., ‘you’ preceding a verb is considered a subject, but following a verb is considered an object). English contains several classes of verbs with different syntactic functions based on the number of participants involved in the event or state denoted. These include intransitive, transitive, ditransitive, and ambitransitive verbs.

Intransitive clauses typically denote actions that involve only one participant (e.g., she laughed; he fell; they yawned) and thus contain an (overt) subject but no object. Transitive clauses denote events or states with two participants (e.g., She saw him; I baked a cake). These participants are realized as overt subjects and objects. Ditransitive clauses have three participants: a subject, a direct object, and an indirect object (e.g., I gave him the book; She told us a story). Finally, ambitransitive verbs can be used with a meaning and syntax that is either transitive or intransitive, e.g., open can be intransitive (the door opened) or transitive (I opened the door).

3.2.4. Source Language Features of Transitivity Marking Present in Light Warlpiri

Source language features present in Light Warlpiri relevant to this study are morphological elements on the verb derived from Kriol and English and, in the use of the inchoative verb ‘get’, semantic influence of Warlpiri (see Section 6). Ergative case-marking on nominals, derived from Warlpiri and shown in example 11, also indicates transitivity, but is not explored in this study. For studies of variable ergative case-marking, see (Meakins and O’Shannessy 2010; O’Shannessy 2016a, 2016b). Briefly, ergative case-marking on overt A arguments in Light Warlpiri is optional, and occurs on approximately 79% of overt A arguments. When the word order is VA, the amount of ergative marking increases to 96% (O’Shannessy 2016b), presumably to disambiguate the A from the O arguments. The form of the ergative marker is most often -ng ‘ERG’, and the other allomorphs present in Warlpiri are rarely present in Light Warlpiri (O’Shannessy 2016b).

The language’s verbal attributes relevant to this study are presented here. Example 11 shows the presence of the Kriol-derived transitive marker -im ‘TR’.

| 11. | wel | warna-ng | i-m | bait-im | wirliya |

| DIS | snake-ERG | 3SG.S-NFUT | bite-TR | leg | |

| “Well a snake bit [him] on the leg”. | |||||

| (ERGstoryLA21_3_2004) | |||||

In Light Warlpiri, the -im form of the transitive affix is a productive derivational affix, as it is in Kriol (Schultze-Berndt et al. 2013). Its presence changes an intransitive verb to a transitive verb, shown in examples 12 and 13.

| 12. | An | yapa-wati-ng | de-m | elp-im |

| CONJ | man-PL-ERG | 3PL.S-NFUT | help-TR | |

| uuju | kam-at | fens-janga | ||

| horse | come-out | fence-ABL | ||

| “The men helped the horse to come out from the fence”. | ||||

| (ERGstory_LA35_2_2005) | ||||

| 13. | de-m | kam-at-im | na |

| 3PL.S-NFUT | come-out-TR | FOC | |

| dat | fens | uuju-janga | |

| DET | fence | horse-ABL | |

| “They made the fence come out away from the horse”. | |||

| (ERGstoryLA26_2_2005) | |||

Unlike in Kriol, the -im affix in Light Warlpiri does not reduce to only a vowel, -i. The affix may have allomorphs that differ in vowel quality (e.g., [im, um, əm]), but these are not examined here. Another Kriol-derived transitive marker -it ‘TR’ is seen in example 14.

| 14. | karnta-pardu-ng | i-m | push-ing-it |

| woman-DIM-ERG | 3PL.S-NFUT | push-PROG-TR | |

| kurdu-pawu | |||

| child-DIM | |||

| “The woman is pushing the child”. | |||

| (ERGstoryLA26_1_2005) | |||

Evidence that ‘-it’ ‘TR’ is not a third singular object pronoun is that it is frequently followed by an overt O argument, as in (14), kurdu-pawu ‘child-DIM’. A following O argument is not obligatory, as these can be elided, but is not uncommon in the data. A transitive-marked verb can be followed by a third singular object pronoun im ‘3SG.O’, but this is fairly uncommon (O’Shannessy and Brown 2021).

| 15. | nyampu-rra-ng | de-m | hag | de-selp-pat |

| DET-PL-ERG | 3PL.S-NFUT | hug | 3PL-RECIP-ITER | |

| “These hug each other”. | ||||

| (ERGstory_AC58) | ||||

Example 15 shows another Kriol-derived element in the verb complex: the iterative affix -pat ‘ITER’ (< Kriol -bat ‘ITER’). It also shows a reciprocal affix, -selp ‘RECIP’, that is influenced by both English (in the phonological form) and Warlpiri, but occurs within the verb complex (O’Shannessy and Brown 2021).

Light Warlpiri has an inchoative or intransitive verb with lexical shape from English, ‘get’, whose semantics are influenced by Warlpiri in terms of being an inchoative verb, as in 16.

| 16. | i-m | get-ing | linji | |

| 3PL.S-NFUT | get-PROG | dry | ||

| “It’s drying out”. | ||||

| (Elicit_LAC23_1_2015) | ||||

The current study asks how the interactions of these influences in Light Warlpiri can be described, and specifically, how the variable presence of the transitive markers, -im ‘TR’ and -it ‘TR’, are conditioned. To respond to this question, the morphosyntactic relationships of the two transitive markers to other verbal morphology are described. Six of the transitivity features of Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) Transitivity Hypothesis are examined in a statistical model to explore whether—as in Kriol, Alyawarra English and the English-lexified contact languages reported on by Meyerhoff (1996)—they play a conditioning role in the presence of the transitive markers in Light Warlpiri.

Observation of the data raised the additional hypothesis that syntactic attributes of the clause might play a role in explaining the variation. Specifically, the presence of first or second singular pronouns as direct objects of the verb, positioned directly after it, might correlate with the absence of transitive marking. For this reason, the presence or absence of these pronouns is included in our statistical model. A hypothesis suggested in earlier work is that clauses in future tense or with irrealis mood, often warnings or threats, are not marked with a transitive marker (O’Shannessy 2005, p. 41). This hypothesis is also examined in the current data. This study provides a first description of the conditioning factors for variable transitivity marking in Light Warlpiri.

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants

Data for the study consist of transcribed audio recordings of 31 Light Warlpiri adult speakers who participated in a range of tasks, part of the Light Warlpiri corpus available at The Language Archive (https://archive.mpi.nl/, accessed on 1 August 2022, O’Shannessy 2006). The speakers were female and male residents of Lajamanu Community, aged between 18 and 37 at the time of recording. Recordings were made at different times from 2004 to 2018. Speakers were recorded by the first author, who spoke Light Warlpiri or Warlpiri with them most of the time, and usually in the presence of another Light Warlpiri speaker. Recordings were made either in a building where the researcher was staying, or in the community Learning Centre, run by the Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education (BIITE) and the Warlpiri Education and Training Trust (WETT). Participants were recruited by the first author through her relationships in the community, from having worked there from 1998 onwards, and through the friend-of-a-friend (Milroy 1987) approach. Often participants would hear from each other that the recordings were taking place, and self-select to be involved. Participants were given a gift of cash as a token of appreciation, along with a copy of their recording on a CD or a USB stick2.

4.2. Materials

The largest quantity of data is from narratives in which the speakers told stories from text-less picture book stimuli (San Roque et al. 2012; O’Shannessy 2004). Speakers looked through the picture books and told their own stories either to another Light Warlpiri speaker or with no other speaker present, if they chose. These data are supplemented by utterances prompted by a series of short videos aiming to elicit reciprocal constructions (cf. Evans et al. 2011; Majid et al. 2011), and by data from elicitation sessions where the first author talked with a subset of speakers. In the elicitation sessions, speakers were asked, for instance, how they spoke about specific types of events in Light Warlpiri. In response, the speakers constructed scenarios in which they would use those or alternative elements. A total of 5550 transitive and intransitive utterances make up the dataset. The recordings were transcribed and translated in either CLAN (MacWhinney 2000) or ELAN (Brugman and Russel 2004) software, by the first author with assistance from Light Warlpiri speakers. The transcribed recordings were glossed using an automated morphosyntactic program from CLAN, customized for Light Warlpiri (Welsh 2020). The data were prepared for analysis using the software package R (R Core Team 2022). Ambiguities and errors in the glossing were corrected either (semi-)manually by editing the transcripts using BBEdit text editor, or by running post-processing scripts in R.

4.3. Coding the Data

To code the data for Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) features of transitivity, each verb type was coded by the first and second authors for the features of kinesis, punctuality, volitionality and object affectedness (O-Affectedness). Coding was binary (‘high’ vs. ‘low’), using Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) description of each feature as a guide. Where needed the data were revisited to see how a verb was used: for instance, the verb ‘break’ might be expected to be high in volitionality, but in the data, this verb was mostly used in nonvolitional contexts, such as ‘the branch broke’ or ‘its leg broke’; so it was coded as ‘low’ in volitionality. The fifth and sixth features, aspect and mood, were coded per clause, based on morphosyntactic glossing. For aspect, clauses marked with the progressive marker, -ing ‘PROG’, were coded as progressive, and all other clauses as nonprogressive. For mood, clauses where the auxiliary was marked with a future or desiderative morpheme were coded as irrealis, while clauses without these morphemes were coded as realis. The presence or absence of a first or second person pronoun following the transitive verb was coded per clause. The four other features from Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) components of transitivity were not coded. There were few non-affirmative clauses in the dataset, so coding for this feature would not have been informative. For the other features, clause-level coding would have taken time beyond that available for a dataset of 1851 transitive clauses. In addition, we were interested to see if coding verb types for the four features identified, plus coding aspect and mood per clause, would yield informative results. We acknowledge that more fine-grained coding would have been ideal; yet we find that the method employed in this study has produced interpretable results. Some verb types were removed from the data because the automated search could not accurately distinguish some relevant contrasts, for instance, when speakers use an inflected Warlpiri verb that was therefore not available to host a Kriol transitive affix. Also, instances of the verb ‘get’ used intransitively were removed (see Section 6).

4.4. Methods of Analysis

We applied a weighted binomial generalized linear mixed-effects model (GLMM) (Bates et al. 2015) to the data for all transitive verbs. The dependent variable was the proportion of the time a given speaker used a certain verb with a transitive affix (either -im or -it). We chose to run the analysis on verb types rather than verb tokens, because some verbs occur very frequently and others only a few times, so analyzing by token would have biased the results in the direction of the patterns exhibited by the highest frequency verbs. The independent variables included six features drawn from Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) components of transitivity: kinesis, punctuality, volitionality, object affectedness, mood and aspect. The first four were coded as low or high, while mood and aspect were coded as proportion of irrealis uses and proportion of progressive uses for a given speaker, respectively. In addition, the proportion of occurrences of a verb with a first or second person O argument or a dative-marked pronoun immediately following each verb was coded for each speaker. Individual speaker was entered as a random effect, to account for the possibility that different speakers might have different overall preferences for transitive marking. Finally, each combination of verb and speaker was weighted by its frequency in the data.

5. Variable Transitive Marking in Light Warlpiri

The current study asks how transitivity is marked on Light Warlpiri verbs, and how variable marking is conditioned. A total of 1851 transitive clauses have been analyzed, out of which 1145, or 62%, have a verb with a transitive marker (either -im ‘TR’ or -it ‘TR’). Of these verbs, 90% host the -im form and 10% host the -it form. The -im form attaches directly to the verb stem, as in examples 1, 2, 4, 12, and 13, whereas most of the occurrences of the -it form follow the progressive affix -ing ‘PROG’, at 86%, as in example 14. Conversely, only 30% of transitive progressive verbs marked with -ing host the transitive affix. In other words, the -im ‘TR’ form only occurs on non-progressive verbs, and never co-occurs with the progressive -ing affix. The -it form mostly occurs on progressive verbs, but can occur on non-progressive verbs as well. These frequencies are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Numbers of tokens and percentages of types of transitive marking.

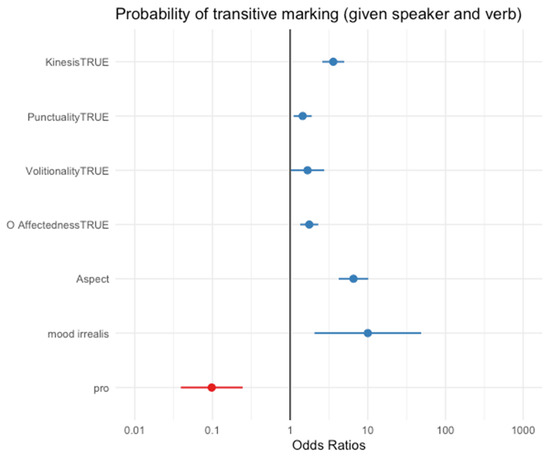

The results of the GLMM analysis (given in Appendix A) are that the six semantic components from Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) analysis of transitivity, and the syntactic attribute of the nominal status of the following word, all contribute to conditioning the occurrence of the transitive affix. There is more likely to be a transitive affix present when at least one of the six semantic features is ‘high’: kinesis, e.g., ‘take’ (β = 1.28, p < 0.001), punctuality, e.g., ‘bite’ (β = 0.37, p = 0.006), volitionality, e.g., ‘give’ (β = 0.52, p = 0.04), O affectedness, e.g., ‘hit’ (β = 0.57, p < 0.001), the verb being nonprogressive (β = 1.88, p < 0.001), and the mood being irrealis (β = 2.30, p = 0.004). On the other hand, when a first or second person pronoun follows the transitive verb, there is less likely to be a transitive affix present (β = −2.32, p < 0.001). As a visual summary, Figure 1 shows the exponential of the beta value of each predictor in the statistical model, giving the factor by which a unit increase in the value of the predictor increases or decreases the odds ratio of a given speaker using a transitive marker on a given verb. For example, if a speaker has 1:1 odds—i.e., 50% probability—of using a certain verb with a transitive marker, given that this verb scores ‘low’ or zero on all the predictors, then if the speaker uses the same verb in the irrealis, the odds of their using a transitive marker become roughly 10:1—i.e., 91% probability.

Figure 1.

A visualization of the output of the statistical model.

In addition to being affected by the semantic features and syntactic context of the verb, the likelihood of transitive marking may also be affected by individual preference. This is accounted for in the model by our use of random intercepts that vary by speaker. The mean baseline log odds ratio across speakers is −2.76; this means that, on average, a speaker is 6% likely to use a transitive marker on a verb that scores ‘low’ or zero on all predictors. The standard deviation of baseline log odds ratios across speakers is 0.70; this means that for 95% of potential speakers, the baseline probability is between 2% and 20%.

Figure 1 shows that the semantic components of kinesis, aspect, and irrealis mood have the highest positive contribution, with irrealis mood having greater uncertainty. The syntactic attribute of ‘pro’, indicating that a first or second person pronoun follows the transitive verb, has a negative contribution equal in size to the positive contribution of irrealis mood.

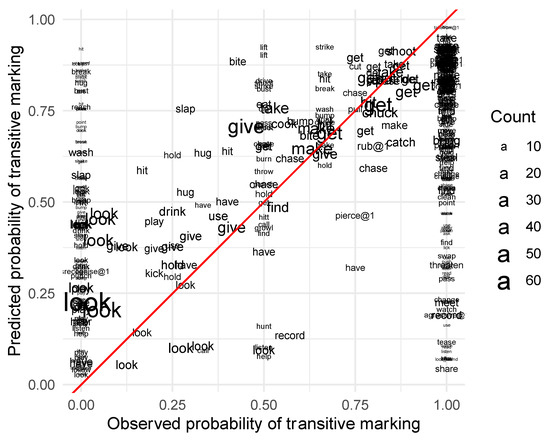

In Figure 2, the predicted probability of transitive marking for each verb type per speaker is given on the Y axis, and the observed probabilities are given on the X axis. The solid line is the 45-degree diagonal, representing the “ideal” case where the predicted and observed probabilities match exactly.

Figure 2.

Predicted vs. observed probability of transitive marking, for each combination of speaker and verb.

Verb types per speaker are labeled with the verb name, e.g., each instance of ‘look’ reflects an individual speaker’s use of ‘look’. Larger type means that the speaker used the verb more often; small type means that the speaker used the verb less often. A glance at Figure 2 shows that, e.g., ‘look’, a verb low in kinesis, is rarely marked with a transitive marker, and that speakers who use the ‘look’ verb often are actually less likely to use it with transitive marking than is predicted by the model. In contrast, ‘get’, which is higher in kinesis, is more often marked with a transitive marker, and is (correctly) predicted by the model as having a higher likelihood of transitive marking, regardless of the speaker. The vertical clusters of items at either end of the X axis are due to there being many cases where a given speaker uses a given verb only once, resulting in an observed probability of transitive marking of either 0% or 100%.

6. Discussion

This study examined Light Warlpiri verbs in terms of six features drawn from Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) components of transitivity, and one syntactic attribute. The statistical model shows that the presence of a transitive marker is conditioned by all six components of transitivity, as well as the presence of a following first or second person O pronoun. The model suggests that variation in transitive marking is consistently patterned.

The conditioning factors of transitive marking on verbs in Light Warlpiri have correlations with English-lexified languages in the area. In Kriol, the four main conditioning factors are affectedness of O, kinesis, punctuality and aspect. These correlate with Light Warlpiri. In Kriol, mood was not a conditioning factor, but in Light Warlpiri, it conditions in the opposite direction to that expected—irrealis clauses are more likely to have transitive marking. Light Warlpiri and Kriol also differ in terms of the presence of the transitive marker in reflexive and reciprocal clauses. In Kriol, reflexive and reciprocal forms are pronominal forms that follow the transitive-marked verb (Dickson and Gautier 2019; Ponsonnet 2016; Batchelor 2017). In contrast, in Light Warlpiri, reflexive and reciprocal forms occur within the verbal component of the clause and, in these clauses, the verb is only rarely marked with both a transitive marker and a reflexive and reciprocal form (O’Shannessy and Brown 2021).

Alyawarra English and Light Warlpiri have in common four of the conditioning features of verbal transitive marking: kinesis, aspect, punctuality and volitionality. They differ in that, in Alyawarra English, transitive marking is also conditioned by object individuation, which was not tested for Light Warlpiri. In addition, in Alyawarra English, reflexive and reciprocal marking follows transitive-marked verbs, as in Kriol.

The English-lexified languages in Meyerhoff’s (1996) study have the conditioning features of aspect, punctuality, mood and affectedness of O in common with Light Warlpiri. They also have some similarity in that irrealis mood, not realis, is a conditioning factor. These comparisons are summarized in Table 5. Variables not examined in this paper are marked n.a.

Table 5.

Studies of contact languages in terms of Hopper and Thompson’s ten features of transitivity.

It is not surprising that these languages would have conditioning attributes in common, not only because the components of transitivity are hypothesized to apply universally, but also because the transitive affixes are likely all derived from ways of speaking that either have earlier pidgin forms in common or were in contact (e.g., Meyerhoff 1996; Koch 2000). We might especially expect a connection between Kriol and Light Warlpiri, because the Light Warlpiri constructions are derived from Kriol. Although similarities between Light Warlpiri and Kriol had been hypothesized, it is always necessary to undertake empirical studies to test hypotheses, because sometimes a language resolves questions in unexpected ways, e.g., in Light Warlpiri, irrealis mood clauses have considerable amounts of transitive marking, where less marking would be expected according to the Transitivity Hypothesis. Unexpected patterning is seen in other areas of Light Warlpiri, for instance, in the near-maximal inventories of reflexive and reciprocal forms (O’Shannessy and Brown 2021) and plosive consonants (Bundgaard-Nielsen and O’Shannessy 2021). In these two domains of Light Warlpiri, the source languages play out differently from each other.

A hypothesis suggested in earlier work is that future tense or irrealis mood clauses, often containing warnings or threats, are not marked with a transitive marker (O’Shannessy 2005, p. 41). The current, larger dataset shows that this is not accurate, as 67% of clauses with irrealis mood contain a verb with a transitive marker present. In the statistical model, irrealis mood strongly predicted a greater likelihood of transitive marking. A more satisfactory explanation is that warnings or threats are often directed to a second person. Clauses in which a first or second person pronoun follow the transitive verb have a transitive marker present on the verb statistically less often. Interestingly, it was found that in the English-lexified languages examined by Meyerhoff (1996), irrealis mood also showed increased presence of transitive marking, in contrast to Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) hypothesis.

To explore the consistency of patterning further, we look more closely at the ditransitive verb, ‘give’, realized as gib-im ‘give-TR’, gib-it ‘give-TR’, gim-mi ‘give-1SG.O’, or gib/giv ‘give’, because it is interesting in terms of the occurrence of a transitive affix on the verb and the presence of a following first or second person pronoun. In Light Warlpiri, as in English, ditransitive ‘give’ can occur in two types of constructions. One, as in example 17, is where the direct object referent wumara ‘money’, immediately follows the verb. The other, as in example 18, is where the indirect object referent, mi ‘1SG.nonsubject’, immediately follows the verb.

| 17. | no | walku | a-m | gib-im | wumara | de | nyampu-ju |

| no | no | 1SG.S-NFUT | give-TR | money | DET | DET-TOP | |

| “No, no, I gave money to this one”. | |||||||

| (FamArgStory_A54) | |||||||

| 18. | wen | yu | go | Darwin-kirra |

| REL | 2SG | go | Darwin-ALL | |

| yu-rra | gib | me | blanket | |

| 2SG.S-FUT | give | 1SG.O | blanket | |

| “When you go to Darwin, you should give me the blanket”. | ||||

| (ELICIT_LA21_2015) | ||||

There are 62 instances of the indirect object construction in the data, and of those, 11 clauses (17%) have a transitive marker. Of 55 direct object constructions, 46 clauses (85%) have a transitive marker. This suggests that within the variable marking with a transitive affix, there is in some contexts fairly clear patterning.

Another verb of interest in terms of transitivity is ‘get’. In Light Warlpiri, there are both transitive and intransitive uses of ‘get’. An example of transitive ‘get’ is given in 19, and of intransitive ‘get’ in 20.

| 19. | Nyiya-janga | yu-m | get-im | gitaa | ngaju-nyang? |

| what-ABL | 2SG.S-NFUT | get-TR | guitar | 1SG-POSS | |

| “Why did you get my guitar?” | |||||

| (ERGstory_LA93_2015) | |||||

| 20. | Kurdu-pawu | i-m | get-ing | wirnkirrpa | tija-k. |

| child-DIM | 3SG.S-NFUT | get-PROG | naughty | teacher-DAT | |

| “The child is becoming naughty to the teacher”. | |||||

| (Elicit_LA21_2015) | |||||

Example 19 shows the transitive verb get-im ‘get-TR’, and example 20 shows the intransitive verb get-ing ‘get-PROG’. Most of the instances of intransitive ‘get’ are inchoative, as in example 20. The inchoative meaning draws on Warlpiri, in which inchoative verbs can be created by the use of a pre-verb and an inflecting inchoative verb, -jarri’ ‘INCHO’, and occur frequently (see example 9 in Section 3.2.1). The semantics of the Warlpiri and Light Warlpiri inchoative verbs are similar, where the S referent becomes, for instance, mata ‘tired’, nyurnu ‘sick’, or api ‘happy’. In Light Warlpiri, complements of the inchoative verbs can be words from Warlpiri or English, showing some similarity to Warlpiri, where the pre-verbal element in an inchoative verb can be drawn from any language. In English, one can say, for instance, ‘get sick’, so the Light Warlpiri inchoative meaning of ‘get’ might also draw on English. The other type of intransitive use of ‘get’ in Light Warlpiri draws on English and Kriol, as in get-ap ‘get up’. In the data, 81% (158/196) of transitive ‘get’ verbs are marked with a transitive affix, and none of the intransitive uses are marked transitively.

It is interesting to note that some verbs may pattern in the data in ways that might not be expected before the data are explored. One example is of the verb drink ‘drink’. This verb was coded as kinesis = ‘high’, punctuality = ‘low’, volitionality = ‘high’, and affectedness of O = ‘high’. However, in the data, when the verb is progressive, drink-ing, it is most often used in the sense of ‘partying’, or ‘drinking with friends’. This means that the coding per verb does not always align with its use in every utterance. Nevertheless, we find that coding per verb type, and including verb frequency in the model, provides interpretable patterns in the data.

Questions not explored in this study that would be of interest are how the variable presence of transitive marking correlates with nominal ergative marking, and with word order, since ergative marking occurs more often when the word order is VA (O’Shannessy 2016b). Following from these questions, it would be interesting to see if the patterning reported in this study remains constant over time, or shows change when the data of child speakers are examined, or if frequency of use changes over time. Questions that the current data could not address include those of whether both unergative and unaccusative intransitive verbs (cf. Perlmutter 1978)3 can be transitivized in Light Warlpiri, and how they interact with Hopper and Thompson’s Transitivity Hypothesis.

7. Conclusions

This study examines the conditions of the occurrence of transitive marking on verbs in the Australian mixed language, Light Warlpiri. Transitive marking on verbs has two forms, -im and -it, and these are productive, as they change the transitivity of a verb from intransitive to transitive. However, it is unclear if all intransitive verbs could undergo this process, or if it is restricted to a subset, for instance, unaccusative intransitive verbs, e.g., kamat ‘come out, emerge’ (cf. Perlmutter 1978). The two forms of the transitive affix are fairly complementary in occurrence, as the -im form usually attaches directly to the verb stem, while the -it form usually attaches to a progressive morpheme, -ing. The study tests the effects of six features drawn from Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) components of transitivity, and one syntactic attribute, the presence of a following first or second person pronoun.

The study finds that the presence of a transitive marker is conditioned by all six components of transitivity. Where the transitive component of a verb is coded as ‘high’, there is more likely to be an overt transitive marker on the verb. However, the converse is true for the feature of mood, where verbs in irrealis mood clauses are more likely to be transitively marked. The presence of a following first or second person O pronoun also correlates with less transitive marking.

The model suggests that variation in transitive marking is consistently patterned. The correlations of the presence of transitive marking with Hopper and Thompson’s (1980) components of transitivity show similarity to studies of other English-lexified contact languages in the area, with each language favoring or disfavoring some specific components (Meyerhoff 1996; S. Dixon 2017; Batchelor 2017).

Transitivity marking and verb semantics in Light Warlpiri draw on all of the source languages: Warlpiri, Kriol and English. The most direct influence is that many of the attributes of transitive marking in Kriol are present in Light Warlpiri, e.g., two forms of the marker, -im and -it, productivity, variable presence on transitive verbs, and the conditioning in terms of degree of transitivity of verbs. Light Warlpiri differs in that the -im form is not contracted to a vowel -i, and the marker is usually absent when a reflexive or reciprocal morpheme is present. It draws on Warlpiri in the use of an inchoative verb of the form get, derived from English, and in that ergative case-marking occurs on overt A arguments in transitive clauses. The ways in which Light Warlpiri constructions differ from those of its sources show that, as in other domains of Light Warlpiri, the source language combinations play out in novel ways.

Author Contributions

The study was conceptualised by C.O., who also collected and transcribed the data with help from Light Warlpiri speakers Tanya Hargraves Napanangka and Deandra Burns Napanangka♱. The project was administered by C.O., who secured the funds. A.C. undertook initial analysis of the data, with R programming by S.K. during a Summer Scholars program 2019–2020 (Australian National University and ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language); both authors continued analysis and coding beyond the program. C.O. and A.C. conceptualised the analysis. C.O. drafted the paper with input from A.C. and S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded by the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, the University of Michigan, a National Science Foundation Grant #1348013, the (Australian Research Council) ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language and ARC Future Fellowship FT190100243.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Michigan (HUM00020003, 12 May 2014) and Australian National University (2015/222, 24 April 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

De-identified data are archived at The Language Archive, tla.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank the speakers and members of Lajamanu community, and the funding bodies. We thank Tanya Hargraves Napanangka and Deandra Burns Napanangka♱ for help with understanding and transcribing the data. Thank you to Gina Welsh for assistance with CLAN automated glossing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Output of glmer() | |||||||

| Generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood (Laplace Approximation) [glmerMod] | |||||||

| Family: binomial (logit) | |||||||

| Formula: ‘Transitive Suffix’/num ~ Kinesis + Punctuality + Volitionality + | |||||||

| O_Affectedness + Aspect + mood_irrealis + pro + (1|Speaker) | |||||||

| Data: vtran_features_with_tran_prop | |||||||

| Weights: num | |||||||

| AIC | BIC | logLik | deviance | df.resid |

| 1281.4 | 1321.3 | −631.7 | 1263.4 | 614 |

| Scaled residuals: | |||||

| Min | 1Q | Median | 3Q | Max | |

| −3.8925 | −0.4859 | 0.3796 | 0.7019 | 9.3534 | |

| Random effects: | ||||

| Groups | Name | Variance | Std.Dev. | |

| Speaker | (Intercept) | 0.4872 | 0.698 | |

| Number of obs: | 623, | groups: | Speaker, | 31 |

| Fixed effects: | |||||

| Estimate Std. | Error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | ||

| (Intercept) | −2.7630 | 0.3621 | −7.630 | 2.36 × 10−14 | *** |

| KinesisTRUE | 1.2792 | 0.1657 | 7.720 | 1.17 × 10−14 | *** |

| PunctualityTRUE | 0.3721 | 0.1366 | 2.723 | 0.00647 | ** |

| VolitionalityTRUE | 0.5170 | 0.2520 | 2.052 | 0.04017 | * |

| O_AffectednessTRUE | 0.5671 | 0.1370 | 4.139 | 3.49 × 10−5 | *** |

| Aspect | 1.8785 | 0.2235 | 8.404 | <2 × 10−16 | *** |

| mood_irrealis | 2.3033 | 0.8069 | 2.855 | 0.00431 | ** |

| pro | −2.3230 | 0.4679 | −4.965 | 6.87 × 10−7 | *** |

| --- | |||||

| Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1 | |||||

| Correlation of Fixed Effects: | |||||||

| (Intr) | KnTRUE | PnTRUE | VlTRUE | O_ATRU | Aspect | md_rrl | |

| KinesisTRUE | −0.019 | ||||||

| PnctltyTRUE | −0.107 | −0.523 | |||||

| VltnltyTRUE | −0.732 | −0.118 | 0.121 | ||||

| O_AffctTRUE | −0.230 | −0.532 | 0.290 | 0.158 | |||

| Aspect | −0.580 | −0.045 | −0.073 | 0.153 | 0.106 | ||

| mood_irrels | 0.094 | −0.036 | −0.019 | −0.059 | −0.030 | −0.091 | |

| pro | 0.095 | 0.109 | −0.121 | −0.098 | −0.170 | −0.097 | −0.294 |

Appendix B

List of English glosses of transitive verbs in the study, in alphabetical order.

| agressive (W) | answer | ask | bite | block | blow | break | bring | break | bump | burn | |||

| bust | buy | call | call_name (W) | carry | catch | change | chase | check | chuck | ||||

| clean | cook | cut | cut (W) | dig | drag | drink | drive | dump | eat | feel | find | fix | |

| follow | force | get | give | growl | have | hear | help | hide | hit | hold | hug | ||

| hunt | ignore | keep | kick | lean | learn | lick | lift | listen | look | look.round | lose | ||

| make | meet | misrecognise (W) | mix | move | need | open | paint | pass | pick.up | ||||

| pierce (W) | plant | play | point | poke | press | press (W) | pull | punch | push | put | |||

| reach | read | record | ride | rub (W) | scratch | see | send | shakeshare | shoot | ||||

| show | shut | slap | smell | spill | steal | strike | swap | swing | take | take.from (W) | |||

| talk | tangle | tease | tell | threaten | throw | tie | touchtow | trip | use | ||||

| wash | watch | wear | wet | beat | wrap | ||||||||

| Note: (W) indicates a Warlpiri-derived verb stem | |||||||||||||

Notes

| 1 | Abbreviations: 1 ‘1st person’, 2 ‘2nd person’, 3 ‘3rd person’, ALL ‘allative’, CAUS ‘causative’, COM ‘comitative’, CONJ ‘conjunction’, COORD ‘coordinator’, DAT ‘dative’, DEM ‘demonstrative’, DET ‘determiner’, DIM ‘diminutive’, DIS ‘discourse marker’, DUAL ‘dual’, EXCL ‘exclusive’, EMPH ‘emphatic’, ERG ‘ergative’, FUT ‘future’, IMP ‘imperative’, INCHO ‘inchoative’, INCL ‘inclusive’, INF ‘infinitive’, ITER ‘iterative’, LOC ‘locative’, NFUT ‘nonfuture’, NPST ‘nonpast’, O ‘object’, PAUC ‘paucal’, PL ‘plural’, PRES ‘present’, PRIV ‘privative’, PROG ‘progressive’, PST ‘past’, RECIP ‘reciprocal’, REFL ‘reflexive’, REL ‘relativiser’, S ‘subject’, SG ‘singular’, TOP ‘topic’, TR ‘transitive’. |

| 2 | The cash amount increased between 2004 and 2018. CDs were in common use in 2004, USB sticks more recently. |

| 3 | We thank an anonymous reviewer for raising these questions. |

References

- Batchelor, Thomas. 2017. Making Sense of Synchronic Variation: Semantic and Phonological Factors in Transitivity Marking in Barunga Kriol. Bachelor’s thesis, Department of Linguistics, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Maechler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavin, Edith L., and Tim Shopen. 1985. Children’s acquisition of Warlpiri: Comprehension of transitive sentences. Journal of Child Language 12: 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugman, Hans, and Albert Russel. 2004. Annotating Multimedia/Multi-modal resources with ELAN. In Proceedings of LREC 2004, Fourth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation. Lisbon: European Language Resources Association (ELRA). [Google Scholar]

- Bundgaard-Nielsen, Rikke, and Carmel O’Shannessy. 2021. When more is more: The mixed language Light Warlpiri amalgamates source language phonologies to form a near-maximal inventory. Journal of Phonetics 85: 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declerck, Renaat. 2007. Distinguishing between the aspectual categories ‘(a)telic’, ‘(im)perfective’ and ‘(non)bounded’. Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics 29: 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, Greg, and Durantin Gautier. 2019. Variation in the reflexive in Australian Kriol. Asia-Pacific Language Variation 5: 171–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, Robert M. W. 1979. Ergativity. Language 55: 59–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, Sally. 2017. Alyawarr Children’s Variable Present Temporal Reference Expression in Two, Closely-Related Languages of Central Australia. Ph.D. thesis, School of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Nicholas, Stephen Levinson, Alice Gaby, and Asifa Majid. 2011. Introduction: Reciprocals and semantic typology. In Reciprocals and Semantic Typology. Edited by Nicholas Evans, Alice Gaby, Stephen Levinson and Asifa Majid. Amsterdam and New York: John Benjamins, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Guéron, Jacqueline. 2008. On the difference between telicity and perfectivity. Lingua 118: 1816–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, Kenneth. 1982. Some essential features of Warlpiri verbal clauses. In Papers in Warlpiri Grammar: In memory of Lother Jagst. Edited by Stephen Swartz. Darwin: Summer Institute of Linguistics-Australian Aborigines Branch, pp. 217–314. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, Kenneth. 1992. Basic word order in two ‘free word order’ languages. In Pragmatics of Word Order Flexibility. Edited by Doris Payne. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, Kenneth, Mary Laughren, and Jane Simpson. 1995. Warlpiri. In An International Handbook of Contemporary Research. Edited by Joachim Jacobs, Arnim von Stechow, Wolfgang Sternefeld and Theo Vennemann. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, vol. 2, pp. 1430–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul J., and Sandra A. Thompson. 1980. Transitivity in grammar and discourse. Language 56: 251–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, Harold. 2000. The role of Australian Aboriginal languages in the formation of Australian Pidgin grammar: Transitive verbs and adjectives. In Processes of Language Contact: Studies from Australia and the South Pacific. Saint-Laurent: Les Éditions Fides. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk, 3rd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Majid, Asifa, Nicholas Evans, Alice Gaby, and Stephen Levinson. 2011. The semantics of reciprocal constructions across languages: An extensional approach. In Reciprocals and Semantic Typology. Edited by Nicholas Evans, Alice R. Gaby, Stephen C. Levinson and Asifa Majid. Amsterdam: John Benjaimins, pp. 29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Meakins, Felicity, and Carmel O’Shannessy. 2010. Ordering arguments about: Word order and discourse motivations in the development and use of the ergative marker in two Australian mixed languages. Lingua 120: 1693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhoff, Miriam. 1996. Transitive marking in contact Englishes. Australian Journal of Linguistics 16: 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milroy, Lesley. 1987. Language and Social Networks, 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shannessy, Carmel. 2004. The Monster Stories: A Set of Picture Books to Elicit Overt Transitive Subjects in Oral Texts. Unpublished Series; Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shannessy, Carmel. 2005. Light Warlpiri—A new language. Australian Journal of Linguistics 25: 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shannessy, Carmel. 2006. Collection “C. O Shannessy”. The Language Archive. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1839/bbfb5fb0-e24b-47a3-9690-3f2d5a61ad42 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- O’Shannessy, Carmel. 2013. The role of multiple sources in the formation of an innovative auxiliary category in Light Warlpiri, a new Australian mixed language. Language 89: 328–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shannessy, Carmel. 2016a. Distributions of case allomorphy by multilingual children speaking Warlpiri and Light Warlpiri. Linguistic Variation 16: 68–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shannessy, Carmel. 2016b. Entrenchment of Light Warlpiri morphology. In Loss and Renewal: Australian Languages since Contact. Edited by Felicity Meakins and Carmel O’Shannessy. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 217–51. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shannessy, Carmel, and Connor Brown. 2021. Reflexive and reciprocal encoding in the Australian mixed language, Light Warlpiri. Languages 6: 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, David M. 1978. Impersonal passives and the Unaccusative Hypothesis. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. Berkeley: UC Berkeley, pp. 157–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ponsonnet, Maïa. 2016. Reflexive, reciprocal and emphatic functions in Barunga Kriol. In Loss and Renewal: Australian Languages since Colonisation. Edited by Felicity Meakins and Carmel O’Shannessy. Language Contact and Bilingualism. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 297–332. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2022. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- San Roque, Lila, Lauren Gawne, Darja Hoenigman, Julia Colleen Miller, Alan Rumsey, Stef Spronck, Alice Carroll, and Nicholas Evans. 2012. Getting the story straight: Language fieldwork using a narrative problem-solving task. Language Documentation & Conservation 6: 135–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sandefur, John. 1979. An Australian Creole in the Northern Terrritory: A Description of Ngukurr-Bamyili Dialects (Part 1). Series B; Darwin: Summer Institute of Linguistics, Australian Aborigines and Islanders Branch, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sandefur, John. 1986. Kriol of North Australia—A Language Coming of Age. Series A; Darwin: Summer Institute of Linguistics, Australian Aborigines and Islanders Branch, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Schultze-Berndt, Eva, Felicity Meakins, and Denise Angelo. 2013. Kriol. In English-Based and Dutch-Based Languages. Edited by Susanne Michaelis, Philippe Maurer, Martin Haspelmath and Magnus Huber. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 241–51. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Jane, and Ilana Mushin. 2008. Clause-initial position in four Australian languages. In Discourse and Grammar in Australian languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 25–58. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, Stephen. 1991. Constraints on Zero Anaphora and Word Order in Warlpiri Narrative Text. Darwin: Summer Institute of Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, Gina Maree. 2020. Automatic Morphosyntactic Analysis of Light Warlpiri Corpus Data. Bachelor’s thesis, School of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).