Abstract

Recent research suggests that island effects may vary as a function of dependency type, potentially challenging accounts that treat island effects as reflecting uniform constraints on all filler-gap dependency formation. Some authors argue that cross-dependency variation is more readily accounted for by discourse-functional constraints that take into account the discourse status of both the filler and the constituent containing the gap. We ran a judgment study that tested the acceptability of wh-extraction and relativization from nominal subjects, embedded questions (EQs), conditional adjuncts, and existential relative clauses (RCs) in Norwegian. The study had two goals: (i) to systematically investigate cross-dependency variation from various constituent types and (ii) to evaluate the results against the predictions of the Focus Background Conflict constraint (FBCC). Overall we find some evidence for cross-dependency differences across extraction environments. Most notably wh-extraction from EQs and conditional adjuncts yields small but statistically significant island effects, but relativization does not. The differential island effects are potentially consistent with the predictions of the FBCC, but we discuss challenges the FBCC faces in explaining finer-grained judgment patterns.

1. Introduction

Natural languages can form filler-gap dependencies, which establish a relationship between a moved element (the filler) and a gap in its base syntactic position (i.e., where the filler is ultimately interpreted).1 In wh-questions such as (1-a), the filler wh-phrase which book is linked to a gap contained within the complement clause. Relative clauses (RCs) such as (1-b) are also filler-gap dependencies, where the head of the RC is the filler that is linked to a gap.

| (1) | a. | Which book did Anna say [that Brian had read __]? |

| b. | That is the book which Anna said [that Brian had read __]. |

Filler-gap dependencies can in principle cross an arbitrary linear and structural distance (Chomsky1973, 1977), as illustrated in (2):

| (2) | a. | Which book did Anna say [that Sunniva thought [that Kristin believed [that Brian had read __]]]? |

| b. | That was the book which Anna said [that Sunniva thought [that Kristin believed [that Brian had read __]]]. |

Although long-distance filler-gap dependencies are possible, it has been known at least since Ross (1967) that trying to relate a filler to a gap inside specific constituents leads to unacceptability. These domains are called islands. Several constituent types have been identified as islands, including subject phrases (nominal or clausal), certain adjuncts, embedded questions (EQs), and relative clauses (RCs) (Chomsky 1973, 1977; Huang 1982; Ross 1967; Stepanov 2007). Examples of these island types are given in (3).

| (3) | a. | Subject |

| *Which boy did you think that [the mother of __] was interesting? | ||

| b. | Adjunct | |

| *Which boy did Christian talk to Odd [after Anne yelled at __]? | ||

| c. | Embedded Question | |

| *Which boy did Odd remember [what __ was called]? | ||

| d. | Relative Clause | |

| *Which cake did you meet the woman [who made __]? |

Following recent experimental work, we label the unacceptability that arises with such filler-gap dependencies island effects (Sprouse 2007; Sprouse et al. 2012, 2016).

Since the discovery of island effects, researchers have been interested in figuring out why they arise. A dominant tradition has sought to explain island effects as arising from universal syntactic conditions on A’-movement operations (Chomsky 1973, 1977, 1986, 2000; Cinque 1990; Huang 1982).2 The traditional syntactic approach predicts, all else equal, that island effects should be observed with all dependencies that are derived via A’-movement, such as wh-movement and relativization (Chomsky 1977; Schütze et al. 2015).

An alternate functionalist tradition attributes island effects to discourse-pragmatic factors grounded in the information status of different elements in a sentence (e.g., Erteschik-Shir 1973; Goldberg 2006; Kuno 1987; Van Valin 1995). Particulars of individual accounts differ, but most employ the distinction between items that are in focus (those that correspond to or request new information) and those that are backgrounded (e.g., items that are given or discourse-old). The underlying intuition behind many of these accounts is that island effects arise when prominent or focused items are linked to gaps in backgrounded constituents. For example, Goldberg (2006) proposed that all filler-gap dependencies place the filler in a discourse prominent position, which is incompatible with gaps that fall inside backgrounded constituents. As a result the account also predicts that backgrounded constituents are islands for filler-gap dependencies.

| (4) | Backgrounded Constituents are Islands (BCI) |

| Backgrounded constituents may not serve as gaps in filler-gap constructions. (Goldberg 2006, p. 135) |

In apparent contradiction to the predictions of both traditional syntactic accounts and discourse-based accounts such as Goldberg (2006), recent experimental research suggests that certain island effects may vary as a function of A’-dependency type (Abeillé et al. 2020; Bondevik et al. 2021; Kush et al. 2018, 2019; Sprouse et al. 2016). The extent of cross-dependency variation is, however, not well established. Moreover, the conclusion that different dependency types yield different island effects has been made based on comparison across experiments. Few studies have directly compared different dependency types within a single experiment.

The first goal of this paper, therefore, is to more systematically map the empirical landscape in one language, Norwegian, through a side-by-side comparison of island effects with wh- and RC-dependencies.

The second goal of the paper is to evaluate our results against a new discourse-based account of island effects, the Focus Background Conflict constraint (henceforth FBCC) put forward by Abeillé et al. (2020), which was developed specifically with the goal of accounting for cross-dependency variation in island effects. To keep the size of the paper manageable, we focus primarily on the FBCC and do not attempt to exhaustively cover how prior syntactic and discourse-based approaches could or would account for our findings.

Before we present our experiment and the results, the remainder of the introduction reviews the FBCC and provides some relevant background on islands in Norwegian.

1.1. The Focus-Background Conflict Constraint

Abeillé et al. (2020) proposed a new discourse-based constraint intended to account for island effects:

| (5) | Focus-Background Conflict Constraint (FBCC) |

| A focused element should not be part of a backgrounded constituent. (Abeillé et al. 2020, ex. 8) |

According to the FBCC, whenever a focused filler is associated with a gap inside a backgrounded constituent, a clash in discourse-status occurs, causing the sentence to be infelicitous (rather than syntactically ill-formed). This infelicity results in a decrease in acceptability.3 The FBCC links islandhood to backgroundedness, but unlike Goldberg’s BCI (4), the FBCC is stated in such a way that it does not uniformly treat backgrounded constituents as islands for all filler-gap dependencies. Instead, the FBCC holds that backgrounded constituents are only islands for dependencies where the filler is focalized. Wh-dependencies put the questioned element into focus (Jackendoff 1972) by seeking new information, so wh-extraction from a backgrounded constituent is predicted to be unacceptable. RC-dependencies, however, do not place the filler—the head of the RC—into focus, because the function of a standard RC is to add information to a given entity. Therefore, the FBCC predicts that RC-dependencies into backgrounded constituents should be felicitous.

Abeillé and colleagues tested the predictions of the FBCC by investigating the acceptability of wh- and RC-dependencies into nominal subject phrases in English and French, which they argued are backgrounded by default. The authors motivate the backgrounded status of subject phrases using a (corrective) negation test (Erteschik-Shir 1973; Van Valin 1995; Van Valin and LaPolla 1997). The test relies on the intuition that constituents can only be negated or denied if they are contained in the part of the sentence that is asserted/focused. The authors note (p. 19) that ‘[i]n a neutral context, it is more felicitous to negate (part of) the object than (part of) the subject.’ This explains the difference between (6-a) and (6-b).

| (6) | a. | A: The football player liked the color of the car. |

| B: No, the size of the car. | ||

| b. | A: The football player liked the color of the car. | |

| B: #No, the baseball player. |

As we will see later, it is unclear whether this test reliably diagnoses backgrounded constituents in other constructions, but for the moment we take the distinction at face value. According to Abeillé and colleagues, the relative infelicity of (6-b) indicates that the subject phrase is backgrounded. Therefore, the account predicts that extraction of a wh-filler from inside a subject should result in an island effect. No island effects are predicted, however, for RC-dependencies from the same subjects.

Across multiple experiments the authors investigated the acceptability of English wh- and RC-dependencies with PP fillers (pied-piping, as in (7-a) and (7-b)) and NP fillers (prepositional stranding as in (7-c) and (7-d)) from definite subject NPs.

| (7) | a. | Pied-piping from Subject,Wh-question |

| Of which sportscar did [the color __] delight the baseball player because of its surprising luminance? | ||

| b. | Pied-piping from Subject, RC-dependency | |

| The dealer sold a sportscar, of which [the color __] delighted the baseball player because of its surprising luminance. | ||

| c. | P-stranding in Subject,Wh-question | |

| Which sportscar did the [color of __] delight the baseball player because of its surprising luminance? | ||

| d. | P-stranding in Subject, RC-dependency | |

| The dealer sold a sportscar, which [the color of __] delighted the baseball player because of its surprising luminance. |

Experiments 2 and 3 of Abeillé et al. (2020) compared sentences such as those above with counterpart sentences in which the wh- and RC-fillers were associated with gaps inside NPs in object position (e.g., (8)) and unquestionably ungrammatical baseline sentences (9).4

| (8) | a. | Pied-piping from Object NP,Wh-question |

| Of which sportscar did the baseball player love [the color __] because of its surprising luminance? | ||

| b. | Pied-piping from Object NP, RC-dependency | |

| The dealer sold the sportscar of which the baseball player loved [the color __] because of its surprising luminance. | ||

| c. | P-stranding in Object NP,Wh-question | |

| Which sportscar did the baseball player love [the color of __] because of its surprising luminance? | ||

| d. | P-stranding in Object NP, RC-dependency | |

| The dealer sold the sportscar which the baseball player loved [the color of __] because of its surprising luminance. |

| (9) | a. | Ungrammatical Baseline,Wh-question |

| *Which sportscar did the baseball player love the color because of its surprising luminance? | ||

| b. | Ungrammatical Baseline, RC-dependency | |

| *The dealer sold a sportscar, which [the color __] the baseball player loved because of its surprising luminance. |

The results of the experiments showed that extraction from object phrases was generally more acceptable than from subject phrases, irrespective of dependency type. Differences in the acceptability of extraction from subjects varied by dependency type and by the category of the filler. For wh-questions, both pied-piping and P-stranding dependencies were judged as unacceptable as the ungrammatical baseline (9-a). For RC-dependencies, while P-stranding dependencies were judged as unacceptable as the corresponding ungrammatical baseline (9-a), pied-piping dependencies were judged significantly more acceptable and on par with grammatical P-stranding from an object NP (8-b).

Abeillé and colleagues argue that the results broadly support the FBCC. The unacceptability of wh-extraction from subject phrases is predicted. The authors also contend that the results of the RC-experiments align with the FBCC. Without any auxiliary assumptions, the FBCC predicts that both pied-piping and P-stranding RC-dependencies into subjects should be acceptable. The prediction for pied-piping is arguably borne out in English (and in French). However, the unacceptability of P-stranding is inconsistent with the simple predictions of the FBCC. To accommodate the P-stranding results, Abeillé and colleagues argue that there is an additional constraint—independent of the FBCC—that renders P-stranding (inside subjects) unacceptable. They speculate that the factor could be grounded in processing difficulty. We find the possible explanations proposed in Abeillé et al. (2020) unlikely5, but for the purposes of the paper we remain agnostic as to why there are differences between P-stranding and pied-piping from nominal subjects.

With the caveat above, the acceptability of pied-piped RC-movement from subjects provides suggestive support for the FBCC. As the FBCC is proposed as a general constraint, it is expected to apply beyond subjects to other domains that have been considered islands. The prediction of the FBCC is that—all else equal—any domain that is backgrounded should block wh-dependencies, but should permit RC-dependencies. Our experiment tests these general predictions in Norwegian based on three domains: adjuncts, embedded questions, and (existential) RCs. We also test extraction with P-stranding from nominal subjects as an unacceptable baseline against which to compare the results of the other domains.

1.2. Norwegian

Native speakers of Mainland Scandinavian languages such as Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish are consistently reported to accept and produce filler-gap dependencies into domains that were considered islands in many other languages (see, among others, Christensen 1982; Engdahl 1982, 1997; Erteschik-Shir 1973; Lindahl 2017; Maling and Zaenen 1982; Taraldsen 1982). It has been observed that Norwegian permits filler-gap dependencies into embedded questions and (some types of) relative clauses. The following sentences are examples of such dependencies found in a recent corpus study of children’s books (Kush et al. 2021, pp. 22, 25):

| (10) | Embedded Question |

| Han ene typen vet vi jo ikke engang [hva __ heter]. | |

| he one guy.def know we prt neg even what is.called | |

| ‘That one guy, we don’t even know what __ is called.’ | |

| ≈ ‘That one guy, we don’t even know the name of.’ |

| (11) | Relative Clause |

| Det er det ingen [som __ vet __] | |

| that is it no.one rel knows | |

| ‘That, there is no one who knows __.’ | |

| ≈ ‘No one knows that.’ |

The acceptability of sentences such as those above in Norwegian (and Swedish and Danish) has led some researchers to posit parametric differences in syntactic islandhood of EQs and RCs in Mainland Scandinavian on the one hand and languages such as English on the other where extraction from EQs and RCs incurs a more reliable cost.6

According to these accounts, the underlying structure of EQs and RCs in Mainland Scandinavian makes it possible to move out of EQs and RCs without violating locality rules on movement, thus rendering the data compatible with traditional syntactic accounts (Lindahl 2017; Nyvad et al. 2017; Vikner et al. 2017).

Island-insensitivity beyond EQs and RCs is not as well-established. The formal literature has largely assumed that subjects are islands for all filler-gap dependencies in Norwegian. This assumption has recently received support from experiments that have shown that sentences such as (12) are consistently rated as unacceptable (Bondevik et al. 2021; Kush and Dahl 2020; Kush et al. 2018, 2019).

| (12) | Subject |

| *Hvilken gutt syntes du at [mora til __] var interessant? | |

| which boy thought you that mother.def to was interesting | |

| ’Which boy did you think the mother of __ was interesting?’ |

The islandhood of adjuncts is also less often discussed. A reference grammar of Norwegian (Faarlund 1992, p. 117) provides examples of apparently acceptable topicalization out of tensed (temporal) adjunct clauses in (13).7 However, Bondevik et al. (2021) found that while topicalization from conditional adjuncts did not result in island effects, topicalization from reason and temporal adjunct clauses did. This suggests that a more nuanced understanding of the islandhood of different adjuncts may be required.

In sum, prior work shows that filler-gap dependencies are in principle possible into EQs and RCs (and perhaps some adjuncts) in Norwegian.

| (13) | Adjunct | |

| a. | Det blir han sint [når jeg sier __]. | |

| that becomes he angry when I say | ||

| ‘That he becomes angry when I say __.’ | ||

| b. | Den saken venter vi her [mens de fikser __]. | |

| that case.def wait we here while they fix | ||

| ‘That case we wait here while they fix __.’ | ||

Though dependencies into EQs, RCs and possibly adjuncts are reported, the acceptability of extraction from different constituents may vary by dependency type ( wh-movement, relativization and topicalization). The majority of documented examples of extraction from RCs feature topicalization (Taraldsen 1982; see also Engdahl 1997 and Lindahl 2017). In the parsed child-fiction corpus of Norwegian bokmål (part of NorGramBank, see Rosén et al. 2009), Kush et al. (2021) found that all instances of extraction from RCs were topicalization dependencies. Attested examples of extraction from EQs usually feature either RC-movement or topicalization: Kush et al. (2021) found that of the 404 examples of extraction from EQs in their corpus, 319 featured relativization and the remaining 85 examples were topicalization dependencies. Wh-question dependencies are conspicuously absent in most collections of naturally occurring examples.8 The lack of any examples with wh-extraction from these domains is potentially surprising given earlier claims that, in principle, nothing blocks such dependencies in Norwegian (e.g., Maling and Zaenen 1982).

Recent judgment studies paint a roughly similar picture: Kush et al. (2018) did not find wh-extraction to be acceptable in Norwegian for extraction from subjects, conditional adjuncts, relative clauses, or complex NPs. A smaller island effect was found for wh-movement from whether EQs. When investigating topicalization on the other hand, Kush et al. (2019) found that contextually-supported topicalization from EQs was acceptable (though topicalization without context did produce an island effect), while judgments of topicalization from RCs were variable. Topicalization from subjects and complex NPs was, however, unacceptable. Interestingly, the authors also found that topicalization from conditional adjuncts did not produce island effects, an effect which Bondevik et al. (2021) replicated. Finally, Kush and Dahl (2020) confirmed that relativization from EQs did not produce island effects.

Given the variation discussed above, we reasoned that Norwegian was a good language in which to systematically test for differences in island effects across dependency type. An added benefit of testing Norwegian is that Norwegian may also offer us the opportunity to isolate discourse-based (or non-structural) factors that influence the acceptability of ‘island violations’ and that are independent of syntactic constraints in domains such as EQs and RCs, if those domains are assumed to not be syntactic islands.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Materials

We ran a preregistered acceptability judgement study that tested Norwegian speakers’ intuition about the acceptability of wh- and RC-extraction from four syntactic domains: (1) Nominal Subjects; (2) Conditional Adjuncts; (3) Embedded Questions; (4) Existential RCs. The first three domains have been tested in previous experiments, but the current experiment is the first, to our knowledge, to test existential RCs in Norwegian.9

The experiment employed the factorial definition of island effects established by Sprouse (2007) and widely used in previous experimental research cross-linguistically (Almeida 2014,Bondevik et al. 2021; Kush et al. 2019; Pañeda et al. 2020; Sprouse et al. 2012, 2016). Test sentences were multiclausal sentences containing a filler-gap dependency. We created test items by manipulating three factors: Distance, Structure, and Dependency. Distance had two levels that controlled whether the gap was in the matrix clause or an embedded clause, corresponding to Short or Long distance between the filler and the gap. Structure had two levels that controlled whether the embedded clause was or contained an Island structure or not (no Island). An island effect was defined as the super-additive interaction of Distance and Structure. Dependency controlled whether the filler-gap dependency in test sentence was a (wh- or RC-dependency).

Our wh-dependencies used lexically restricted wh-phrases (e.g., hvilke aktivister ‘which activists’) instead of bare wh-phrases. RC-dependencies contained the relative pronoun som (glossed as rel) and the lexical material of the head matched the filler in corresponding wh-dependency sentences.

For RC dependencies we chose to use what we term demonstrative RCs such as those in (14). In demonstrative RCs the RC head is definite and is preceded by (i) the pronoun det and a tensed version of the verb være (‘to be’). In such RCs the pronoun det can be interpreted as analogous to the demonstrative that in the gloss in (14). In such RCs the pronoun/demonstrative is focused, while the head of the RC and and the RC itself are backgrounded. Since the head of the RC is backgrounded, the dependency is suitable for testing the FBCC.

| (14) | Det var boken [som jeg leste __ ]. |

| It was book.def rel I read | |

| ‘That was the book that I read.’ |

We chose to use demonstrative RCs in order to avoid introducing extra lexical or semantic material into the matrix clause of RC-dependency sentences that was not in wh-dependency sentences. One complication associated with using demonstrative RCs is that they are string-ambiguous with cleft sentences. The sentence in (14) could also be interpreted in the right contexts as roughly analogous to the English it-cleft It was the book that I read. Clefting in Norwegian places the head of the cleft in focus as in English (Gundel 2002; Hedberg 2000; Prince 1978), so the FBCC predicts that it should not be possible to associate a clefted filler with a gap inside a backgrounded constituent (on par with wh-extraction).

We acknowledge that this potential ambiguity potentially complicates using our wh- and RC-dependencies to test the divergent predictions of the FBCC for focalizing and non-focalizing dependencies. We note that some of our items give us the opportunity to test whether the ambiguity had negative effects: Our EQ items were adapted from Kush and Dahl (2020), which tested the acceptability of ‘eventive’ relativization from EQs. Eventive RCs are not subject to the same ambiguity as demonstrative RCs, so to the extent that effects in our study match those in Kush and Dahl (2020), we can conclude that the ambiguity did not cause a problem.

We applied the Distance × Structure × Dependency design to all four of the island types mentioned above. We briefly discuss design considerations for each island type in turn.

2.1.1. Subjects

Before testing for cross-dependency differences in extraction from adjuncts, EQs and existential RCs, we wanted to establish an unacceptable baseline against which to compare other effects. Prior work shows that Norwegian speakers consistently rate wh- and RC- dependencies from nominal Subjects with P-stranding as unacceptable (Bondevik et al. 2021; Kush and Dahl 2020; Kush et al. 2018; Kush et al. 2019). We therefore reasoned that we could use the Subject Island sub-design as an example of uncontroversially unacceptable extraction. Since we are primarily using the Subject Island items as a benchmark for unacceptability, it is immaterial for the immediate purposes of our study whether the unacceptability arises from a grammatical violation (as is standardly assumed) or whether it reflects parsing difficulties related to P-stranding (as suggested by Abeillé et al. 2020).

Subject Island items were adapted from previous studies, e.g., (Bondevik et al. 2021; Kush and Dahl 2020; Kush et al. 2018). A full example item is presented in (15). Here and in the other items, the Long-Island conditions ((15-g) and (15-h)) correspond to sentences where the gap is located inside an island structure.

| (15) | a. | Short × No Island xWh-dependency |

| Hvilke aktivister er redde for at fabrikken skader miljøet? | ||

| which activists are worried c factory.def harms environment.def | ||

| ‘Which activists are worried that the factory is harming the environment?’ | ||

| b. | Short × No Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det er aktivistene som er redde for at fabrikken skader miljøet. | ||

| those are activists.def rel are worried c factory.def harms environment.def | ||

| ‘Those are the activists that are worried that the factory is harming the environment.’ | ||

| c. | Long × No Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvilken fabrikk er aktivistene redde for at skader miljøet? | ||

| which factory are activists.def worried c harms environment.def | ||

| ‘Which factory are the activists worried __ is harming the environment?’ | ||

| d. | Long × No Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det er fabrikken som aktivistene er redde for at skader miljøet. | ||

| that is factory.def rel activists.def are worried c harms environment.def | ||

| ‘That is the factory that the activists worry __ is harming the environment.’ | ||

| e. | Short × Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvilke aktivister er redde for at avfall fra fabrikken skader miljøet? | ||

| which activists are worried c waste from factory.def harms environment.def | ||

| ‘Which activists are worried that waste from the factory is harming the environment?’ | ||

| f. | Short × Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det er aktivistene som er redde for at avfall fra fabrikken skader miljøet. | ||

| those are activists.def that are worried c waste from factory.def harms environment.def | ||

| ‘Those are the activists that are worried that waste from the factory is harming the environment.’ | ||

| g. | Long × Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvilken fabrikk er aktivistene redde for at avfall fra skader miljøet? | ||

| which factory are activists.def worried c waste from harms environment.def | ||

| ‘Which factory are the activists worried that waste from __ harms the environment?’ | ||

| h. | Long × Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det er fabrikken som aktivistene er redde for at avfall fra skader miljøet. | ||

| that is factory.def that activists.def are worried c waste from harms environment.def | ||

| ‘That is the factory that the activists are worried that waste from __ is harming the environment.’ |

2.1.2. Embedded Questions

EQ items were adapted from Kush and Dahl (2020). We used EQs where either hva (‘what’) or hvor (‘where’) were linked to VP-internal gaps. In Long test sentences, the gap always occurred in embedded subject position immediately following the complementizer at (in the Long-noIsland condition) or the wh-phrase (in the Long-Island condition). Extraction of a subject immediately following a lexically-filled complementizer phrase is acceptable for (most) Norwegians, i.e., Norwegian does not exhibit Comp-t effects (Lohndal 2009,Vangsnes 2019). A full example of a test item is in (16):

| (16) | a. | Short × No Island xWh-dependency |

| Hvilken snekker sa at hylla skulle monteres i stuen? | ||

| which carpenter said c shelf.def should install.pass in living.room.def | ||

| ‘Which carpenter said that the shelf should be installed in the living room?’ | ||

| b. | Short × No Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det var snekkeren som sa at hylla skulle monteres i stuen. | ||

| that was carpenter.def rel said c shelf.def should install.pass in living.room.def | ||

| ‘That was the carpenter that said that the shelf should be installed in the living room.’ | ||

| c. | Long × No Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvilken hylle sa snekkeren at skulle monteres i stuen? | ||

| which shelf said carpenter.def c should install.pass in living.room.def | ||

| ‘Which shelf did the carpenter say __ should be installed in the living room?’ | ||

| d. | Long × No Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det var hylla som snekkeren sa at skulle monteres i stuen. | ||

| that was shelf.def rel carpenter.def said c should install.pass in living.room.def | ||

| ‘That was the shelf that the carpenter said __ should be installed in the living room.’ | ||

| e. | Short × Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvilken snekker sa hvor hylla skulle monteres? | ||

| which carpenter said where shelf.def should install.pass | ||

| ‘Which carpenter said where the shelf should be installed?’ | ||

| f. | Short × Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det var snekkeren som sa hvor hylla skulle monteres. | ||

| that was carpenter.def rel said where shelf.def should install.pass | ||

| ‘That was the carpenter that said where the shelf should be installed.’ | ||

| g. | Long × Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvilken hylle sa snekkeren hvor skulle monteres? | ||

| which shelf said carpenter.def where should install.pass | ||

| ‘Which shelf did the carpenter say where __ should be installed?’ | ||

| h. | Long × Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det var hylla som snekkeren sa hvor skulle monteres. | ||

| that was shelf.def that carpenter.def said where should install.pass | ||

| ‘That was the shelf that the carpenter said where __ should be installed.’ |

Our items, such as those from Kush and Dahl (2020), differed from the EQs tested in Kush et al. (2018, 2019) in two ways. First, we did not use embedded polar questions (i.e., whether questions). Second, our items used the Norwegian equivalents of know, forget, say, remember, and find out (many of which Lahiri (2002) categorizes as responsive predicates) as embedding predicates instead of rogative predicates such as wonder which were used in Kush et al. (2018).10 We chose to use these EQs because Kush et al. (2021) found that dependencies such as (16) were far more frequent in the input than dependencies into polar questions and (ii) Kush and Dahl (2020) found that relativization from such EQs did not result in an island effect. We wished to see whether we would replicate this result.

In order to determine the predictions of the FBCC for EQs, we wanted to establish whether EQs are backgrounded or focused. EQs are traditionally considered backgrounded, insofar as they do not convey the assertion of the clause (Simons 2007). We nevertheless chose to test whether EQs in our items were focused or backgrounded using the negation test employed by Abeillé et al. (2020). We can conclude, for example, that the embedded declarative clause is part of the focus domain in (17-a) because we can negate constituents, such as the subject, in corrective responses (17-b).

| (17) | a. | Snekkeren sa at hylla skulle monteres. |

| carpenter.def said that shelf.def should install.pass | ||

| ‘The carpenter said that the shelf should be installed.’ | ||

| b. | Nei, kommoden. | |

| No dresser.def | ||

| ‘No, the dresser.’ |

Applying the same test to the EQ in (18-a) results in (18-b). We have marked the judgment in (18-b)as ‘(%)#’ to reflect that there is some inter-speaker variation between the Norwegian-speaking authors of the paper and ten additional informants, on whether it is infelicitous to negate the subject in a corrective response. However, seven out ten of our informants reported either complete infelicity for the negation of elements inside wh-clauses or noted that negation of the subject in the EQ was less felicitous than negation of the subject in the corresponding embedded declarative clause (17).

| (18) | a. | Snekkeren sa hvor hylla skulle monteres. |

| carpenter.def said where shelf.def should install.pass | ||

| ‘The carpenter said where the shelf should be installed.’ | ||

| b. | Nei, kommoden. | |

| No dresser.def | ||

| ‘No, the dresser.’ |

The fact that informants, on balance, judged negation to be less felicitous with the EQ than with an embedded declarative is consistent with there being a difference between the backgroundedness of the two constituents on average. Thus, the FBCC predicts that there should be an observable penalty for extracting a focused wh-filler from an EQ compared to RC-extraction from the same EQ. There are two ways to deal with inter-participant variation in the results of the negation test: one could simply ignore it and treat EQs as backgrounded across the board (as a traditional view might assume), or one could assume that (participants’ judgments of) the backgroundedness of EQs can vary in a way that should interact with possibility of extraction. Under the first option, the penalty associated with wh-extracting from an EQ should be relatively consistent across trials (e.g., it should clearly affect the mode of the judgment distribution). Under the second option, we expect judgments of wh-extraction from an EQ to vary across trials or participants, corresponding to whether the EQ is interpreted as backgrounded. We take the first option.

2.1.3. Adjuncts

We used conditional clauses headed by om ‘if’ as the adjunct in our items, as in (19-a) below. Adjuncts are traditionally regarded as backgrounded constituents. Again we ran the corrective negation test to determine whether we could confirm the traditional categorization. We asked the same individuals as above whether it was possible to negate the adjunct-internal object kniven ‘the knife’ in the example below, which was based on one of our test items.

| (19) | a. | Kokken blir sur om hun bruker kniven. |

| chef.def gets angry if she uses knife.def | ||

| ‘The chef gets angry if she uses the knife.’ | ||

| b. | Nei, øsen. | |

| no ladle.def | ||

| ‘No, the ladle.’ |

Once again, we saw some variability in judgments. Overall, seven out of ten informants judged negation in (19-a) to be completely infelicitous our degraded. Following our logic above, we interpret this as suggestive confirmation that conditional adjuncts are backgrounded. As such, the FBCC predicts that there should be an observable penalty for wh-extraction from a conditional adjunct compared to RC-extraction.

A full set of items is presented below:

| (20) | a. | Short × No Island xWh-dependency |

| Hvilken kokk misliker at hun bruker den skarpe kniven? | ||

| which chef dislikes c she uses the sharp knife.def | ||

| ‘Which chef dislikes that she uses the sharp knife?’ | ||

| b. | Short × No Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det er kokken som misliker at hun bruker den skarpe kniven. | ||

| that is chef.def rel dislikes c she uses the sharp knife.def | ||

| ‘That is the chef that dislikes that she uses the sharp knife.’ | ||

| c. | Long × No Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvilken kniv misliker kokken at hun bruker? | ||

| which knife dislikes chef.def c she uses | ||

| ‘Which knife does the chef dislike that she uses __?’ | ||

| d. | Long × No Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det er kniven som kokken misliker at hun bruker. | ||

| that is knife.def rel chef.def dislikes c she uses | ||

| ‘Which knife does the chef dislike that she uses __?’ | ||

| e. | Short × Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvilken kokk blir sur om hun bruker den skarpe kniven? | ||

| which chef gets angry if she uses the sharp knife.def | ||

| ‘Which chef gets angry if she uses the sharp knife?’ | ||

| f. | Short × Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det er kokken som blir sur om hun bruker den skarpe kniven. | ||

| that is chef.def rel gets angry if she uses the sharp knife.def | ||

| ‘That is the chef that gets angry if she uses the sharp knife.’ | ||

| g. | Long × Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvilken kniv blir kokken sur om hun bruker? | ||

| which knife gets chef.def angry if she uses | ||

| ‘Which knife does the chef get angry if she uses __?’ | ||

| h. | Long × Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det er kniven som kokken blir sur om hun bruker. | ||

| that is knife.def rel chef.def gets angry if she uses | ||

| ‘That is the knife that the chef gets angry if she uses __.’ |

2.1.4. Relative Clauses

Kush et al. (2018, 2019) tested wh-extraction and topicalization from RCs that were attached constituents in direct or oblique argument positions such as (21).11

| (21) | Hvilken film snakket han med mange kritikere som likte __? |

| Which film spoke he with many critics rel liked | |

| ‘ Which film did he speak with many critics that liked __?’ |

We chose to test extraction from existential RCs such as (22) instead, because existential RCs (alongside clefts) are the RC-type most commonly observed in naturalistic examples of extraction (Engdahl 1997; Erteschik-Shir and Lappin 1979; Kush et al. 2021; Lindahl 2017).

| (22) | Det var mange som bestilte ølet. |

| it was many rel ordered beer.def | |

| ‘There were many people who ordered the beer.’ |

Existential RCs are different from ordinary restrictive RCs in that they introduce or assert the existence of a referent (the head) and use the RC to provide potentially new information about that referent (Engdahl 1997; Lambrecht 1994). 12 Existential RCs are string-ambiguous with cleft sentences in Norwegian, in that both constructions have an expletive subject det, followed by the copula. To avoid the possibility that participants interpreted existential RCs as clefts, we used bare (weak) quantifiers as RC-heads (see Milsark 1974), which bias towards an existential reading.

If backgrounded material is that which is not asserted or which is presupposed, then existential RCs are not backgrounded. To verify whether the negation test identifies existential RCs as not-backgrounded, we tested the felicity of negating the RC-internal object øl/ølet ‘beer/the beer’ as in (23-b).

| (23) | a. | Det var mange som bestilte øl/ølet. |

| it was many rel ordered beer/beer.def | ||

| ‘There were many people who ordered (the) beer.’ | ||

| b. | Nei, vin/vinen. | |

| No wine/wine.def | ||

| ‘No, (the) wine.’ |

Eight of ten of our informants were willing to accept the negation in (23-b), corroborating the consensus view that existential RCs are not backgrounded. As such, the FBCC predicts that both relativization and wh-extraction from RCs in our experiment should be felicitous.

An example item set is below:

| (24) | a. | Short × No Island xWh-dependency |

| Hvilken servitør sa at mange bestilte ølet? | ||

| which waiter said c many ordered beer.def | ||

| ‘Which waiter said that many people ordered the beer?’ | ||

| b. | Short × No Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det var servitør som sa at mange bestilte ølet. | ||

| that was waiter.def rel said that many ordered beer.def | ||

| ‘That was the waiter that said that many people ordered the beer.’ | ||

| c. | Long × No Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvilket øl sa servitøren at mange bestilte? | ||

| which beer said waiter.def c many ordered | ||

| ‘Which beer did the waiter say many people ordered __?’ | ||

| d. | Long × No Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det var ølet som servitøren sa at mange bestilte. | ||

| that was beer.def rel waiter.def said c many ordered | ||

| ‘That was the beer that the waiter said many people ordered __.’ | ||

| e. | Short × Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvor mange var det som bestilte ølet? | ||

| how many was it rel ordered beer.def | ||

| ‘How many were there that ordered the beer?’ | ||

| f. | Short × Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det var mange som bestilte ølet. | ||

| it was many rel ordered beer.def | ||

| ‘There were many people that ordered the beer.’ | ||

| g. | Long × Island xWh-dependency | |

| Hvilket øl var det mange som bestilte? | ||

| which beer was it many rel ordered | ||

| ‘Which beer were there many people that ordered __?’ | ||

| h. | Long × Island × RC-dependency | |

| Det var ølet som det var mange som bestilte. | ||

| that was beer.def rel it was many rel ordered | ||

| ‘That was the beer that there were many people that ordered __.’ |

Before moving on, we must note one way in which our RC items deviated from the strict factorial design, since it has bearing on whether cross-condition comparisons are apt. A commonality across materials in our Subject, EQ, and Adjunct sub-designs was that wh-fillers and RC heads in Short conditions were lexical NPs extracted from matrix subject position. This design feature could not be carried over to Short-Island conditions in the RC sub-design because the formal subject of an existential RC construction is an expletive det that cannot be questioned or relativized. Since it was not possible to have short-distance extraction from subject position in these items, we had to construct alternative comparison sentences. For the Short Island RC-dependency condition (24-f), we used the simple existential RC that formed the base used in the other Island sentences. In these sentences there simply was no filler-gap dependency in the matrix clause. For the Short Island Wh-dependency (24-g), we created a wh-question by questioning the quantified head of the base existential RC. Given that the these sentences deviated from the factorial design, the interaction effect that we measure does not offer a direct measurement of a residual island effect where all extraneous factors have been cleanly factored out. We therefore do not rely solely on the presence or absence of a statistically significant interaction to determine whether there was an island effect or not.

2.2. Participants

A total of 96 native Norwegian speakers were recruited through Prolific and public announcements on several social media websites. Prolific participants were paid GBP 3.50; participants recruited via social media were not compensated. The average study duration was 23 min. After completing the experiment, the participants were asked a series of demographic questions that concerned age, their language/dialect background, their parents’ language/dialect background, and their preferred standard of written Norwegian. We included a question about participants’ age by providing five age groups to choose from.13 The distribution of participants by age group was the following: 18–30 (54 participants), 31–39 (25 participants), 40–49 (11 participants), 50–59 (2 participants), and 60–69 (4 participants). We excluded 1 participant who reported that Norwegian was not their native language.

2.3. Procedure

A total of 16 items of 8 conditions apiece were created for each island type, according to the design outlined above. This resulted in 512 test sentences that were distributed across 8 experimental lists, with each participant seeing 64 test sentences. The test sentences were interspersed with 40 filler sentences, resulting in 104 sentences that each participant was asked to judge. The filler sentences contained 10 acceptable fillers (good fillers) and 30 unacceptable fillers (bad fillers) that varied in length and complexity. We chose unequal number of acceptable and unacceptable fillers to compensate for the fact that at least 75% of test items were acceptable sentences without any grammatical errors (Short-noIsland, Short-Island, and Long-noIsland conditions). Adding more unacceptable items allowed us to (roughly) counter-balance the number of acceptable and unacceptable sentences in the whole experiment to mitigate scale bias. Sentences were pseudorandomly ordered between participants, such that no two consecutive items were of the same island or filler type.

The experiment was built using jsPsych (De Leeuw 2015) and hosted on a JATOS server at UiT The Arctic University of Norway (Lange et al. 2015). Participants completed the task using their own personal computer. They were instructed to give ratings to sentences that were presented on a screen one at a time. The judgments were given on a seven point scale. Participants were instructed to treat 1 as dårlig ‘bad’ and 7 as god ‘good’, and to rate sentences that were ’maybe not completely unacceptable, but also not fully acceptable’ with a score in the middle range. The first two items of the study were unannounced practice ‘filler’ items: one regular, acceptable sentence, and one unacceptable sentence. Termed ’anchoring’ items by Sprouse and Almeida (2017), these items served to expose participants to, and encourage use of, the entire range of the scale. These items were the same, and presented in the same order, for every participant.

2.4. Analysis

Data preprocessing included three steps. First, ratings were z-transformed by participant to reduce bias from differences in participants’ use of the 7-point scale. Second, trials where no rating was recorded (68 trials, constituting 0.7% of all trials) were removed from the dataset.14 Third, one participant with unusually low ratings to grammatical sentences was removed from the dataset. In the preregistration we planned to remove trials where participants responded in less than 1000 ms, but after removing trials with missing ratings, no trials remained with a reaction time less than this threshold. We had also planned to remove any participant whose mean rating to all trials was less than the midpoint of the 7 pt. scale, but there were no participants who met this criterion.

We applied two different types of models to participant ratings to test for island effects: We applied linear mixed-effects models (LMEMs) to z-scored ratings using the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al. 2017) in R (R Core Team 2021). We also analyzed participants’ untransformed ratings using cumulative ordinal regression with cumulative link mixed models (CLMMs) implemented using the ordinal package (Christensen 2019). Unlike LMEMs, CLMMs do not assume that numerical judgments are drawn from an ordinal scale and have been argued to be more appropriate for analysis of rating data (Bürkner and Vuorre 2019; Liddell and Kruschke 2018). We present the results of both analyses.

We ran separate models for each island type. All models included Distance, Structure, and Dependency and their interactions as fixed effects and a full random effects structure (Barr et al. 2013). If island effects vary by dependency type, we expect a three-way interaction of Distance × Structure × Dependency. Centered simple difference coding was used for contrasts: Distance (Long = −0.5, Short = 0.5); Structure (Island = −0.5, noIsland = 0.5); Dependency (Wh-dependency = −0.5; RC-dependency = 0.5). Details of the individual models are provided in Section 3.

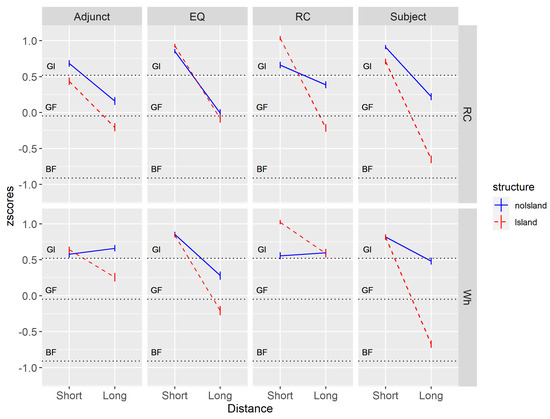

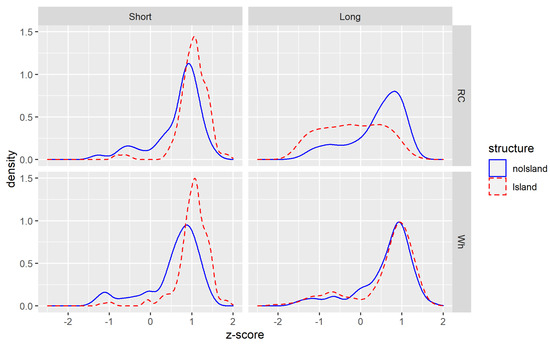

We report the size of each interaction effect using a Difference-in-Differences (DD) score (Maxwell and Delaney 2004) calculated on the z-scored ratings. We also perform further (informal) comparisons. First, we compare the average (z-scored) rating of the Long-Island conditions to the average ratings of grammatical fillers (GF in Figure 1) and the average ratings of all grammatical items (GI in Figure 1, which included the good fillers, the Short-noIsland, Short-Island, and Long-noIsland conditions), as a way of determining the ‘overall’ acceptability of individual conditions. Such comparisons are important in light of recent findings that statistically significant island effects have been observed in some languages even when the island-violations are judged to be relatively acceptable (see discussion of so-called ‘subliminal island effects’ in Almeida (2014); Keshev and Meltzer-Asscher (2019); Pañeda et al. (2020)). Second, we compare the ratings of average z-scores of Long-Island conditions within constituent type as a way of assessing whether one dependency type is ‘more unacceptable’ in the absolute sense than another. Third, we examine the distributions of (z-scored) participant judgments in order to determine whether the average acceptability ratings we observe represent a central tendency in the data and to determine the extent to which there was variability in judgments. Recent work has argued that this kind of distributional analysis helps in drawing inferences about the source of island effects (see Kush et al. 2018, 2019; Pañeda and Kush 2021 for discussion).

Figure 1.

Interaction plots for each island type split by dependency. Error bars represent standard errors. Dotted lines represent mean ratings for all acceptable items (“good” items, GI), acceptable fillers (“good” fillers, GF), and unacceptable fillers (“bad” fillers, BF).

3. Results

Participants rated bad filler sentences low (mean z-score = −0.91). The average rating of bad fillers is marked on each interaction plot with the dotted line labeled ‘BF’ to give a sense of the lower bound of unacceptability. Good fillers, which varied in complexity, received an average rating close to z = 0, represented by the dotted line labeled ‘GF’. Aggregated together all good items (filler and test) were rated close to z = 0.51 (‘GI’ in Figure 1). Ratings on these trials indicate that the participants understood and performed the task as expected. Below we present the results for each of the island types in turn.

3.1. Subjects

Statistical analysis revealed a significant Structure × Distance × Dependency interaction (LMEM: = 0.52, t = 3.27, p = 0.0037; CLMM: = 2.24, z = 3.64, p = 0.0003), indicating that the size of the Structure × Distance island effect varied across dependency type. Follow-up analysis revealed significant Structure × Distance interactions for RC-dependencies (LMEM: = −0.67, t = −5.66, p < 0.0001; CLMM: = −1.19, z = −2.61, p = 0.0090) and Wh-dependencies (LMEM: = −1.18, t = −10.4, p < 0.0001; CLMM: = −3.24, z = −6.65, p < 0.0001). The Structure × Distance interaction effect was larger for wh-dependencies than for RC-dependencies (DD = 1.15 v. DD = 0.67, respectively). The difference in size of the interaction effect appears largely driven by the reduced average acceptability of the RC-dependency in the Long-noIsland condition (z = 0.22) compared to the wh-dependency (z = 0.48). The average acceptability of wh-movement from a subject (z = −0.66) and RC-movement from a subject (−0.65) did not differ significantly.

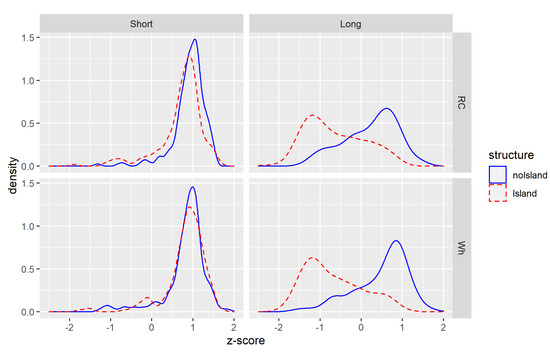

Ratings distributions by condition are presented in Figure 2. Ratings across Short conditions were nearly all at the top end of the scale (z ∼ 1). Ratings were differently distributed in the Long-noIsland versus Long-Island conditions. Ratings in Long-noIsland conditions were largely distributed around z = 1, though there was a longer left tail indicating that participants rated the occasional Long-noIsland sentences as degraded. In contrast, the Long-Island conditions mostly grouped around the lower end of the scale (z <−1), indicating that participants overwhelmingly perceived the sentences as deeply unacceptable.

Figure 2.

Distributions of ratings for sentences in the Subject Island sub-design split by dependency type and condition.

3.2. Embedded Questions

Statistical analysis revealed a significant Structure × Distance × Dependency interaction in the LMEM ( = 0.34, t = 2.05, p = 0.0508), but the 3-way interaction was only marginally significant in the CLMM ( = 1.22, z = 1.82, p = 0.0682). Resolving the three-way interaction revealed that while there was an island effect for wh-dependencies as manifested by a significant Structure × Distance interaction (LMEM: = −0.48, t = −4.33, p = 0.0003; CLMM: = −1.37, z = −3.59, p = 0.0003), no such effect was found for RC-dependencies. The DD score was larger for wh-dependencies than for RC-dependencies (DD = 0.47 v. DD = 0.15, respectively).

Visual inspection of Figure 1 suggests that the difference in interaction size across dependency type is mostly due to differences in the acceptability of the Long-noIsland conditions (Wh: z = 0.28 v. RC: z = −0.01), not differences between the Long-Island conditions. The average acceptability of wh-movement from an EQ (z = −0.21) is relatively close to the mean acceptability of RC-movement (z = −0.08) and post hoc comparisons revealed that the numerical difference between the conditions was not significant (p > 0.1).

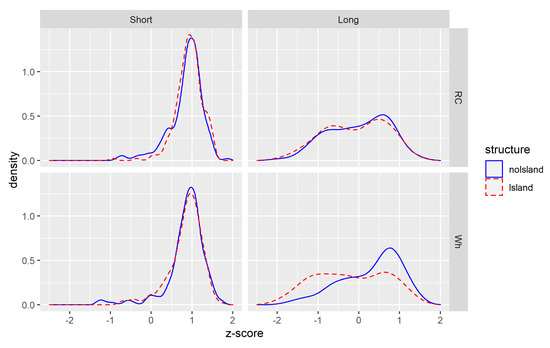

Ratings distributions are presented in Figure 3. Ratings in Short conditions were nearly all high, whereas ratings in Long conditions were more variable. The variable ratings of RC-dependencies in the Long-Island and Long-noIsland conditions overlap completely, confirming that participants did not perceive RC-movement from EQs as marked compared to RC-movement from embedded declaratives. For wh-dependencies, ratings in the Long conditions were also variable, but there was slightly less overlap between the Long-Island and Long-noIsland distributions. On the one hand, participants were slightly less likely to give high ratings to wh-extraction from EQs than wh-extraction from embedded declaratives. This could be interpreted as evidence for a penalty. On the other hand, if we compare judgments of Long-Island sentences across dependency type, we see that the distributions in the Long-Island Wh and the Long-Island RC condition are nearly identically distributed. This could be taken to suggest that participants did not perceive wh-movement from EQs to be worse, in the absolute sense, than RC-movement from EQs.

Figure 3.

Distributions of ratings for sentences in the Embedded Question sub-design split by dependency type and condition.

3.3. Adjuncts

Statistical analysis revealed a significant Structure × Distance × Dependency interaction in the CLMM ( = 1.36, z = 2.33, p = 0.0199), though the effect was only marginally significant in the LMEM ( = 0.32, t = 1.84, p = 0.0819). Effect sizes differed between the two dependency types (DD = 0.47 for wh-dependencies v. DD = 0.11 for RCs). We ran a separate analysis for each dependency type, which revealed an absence of an island effect for RC-dependencies as manifested by a non-significant Structure × Distance interaction (LMEM: p = 0.5; CLMM p = 0.9). Visual inspection of Figure 1 confirms the absence of an island effect for RC-dependencies. There was a significant Structure × Distance interaction for wh-dependencies (LMEM: = −0.41, t = −2.61, p = 0.0214; CLMM: = −1.35, z = −3.11, p = 0.0019). The interaction is notable, however, in that wh-movement from a conditional adjunct was rated higher on average (≈z = 0.25) than RC-movement (≈z = −0.21). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that this difference was significant (p < 0.05).

Figure 4 shows that the participants’ ratings across Short conditions were generally rated high (∼+1). The distribution of judgments in Long conditions differed across dependency type. Judgments in the the Long-noIsland-Wh-dependency condition were mostly high, similar to judgments in Short conditions. Judgments in the the Long-Island-Wh dependency condition were more variable. The distribution suggests relatively polar responses across trials with a larger cluster around z = +0.75 and a smaller cluster around z = −1. It seems that the majority of trials were rated around +0.75, suggesting that the sentences were judged acceptable more often than they were rejected. Ratings of Long sentences for RC-dependencies had qualitatively different distributions. Ratings of Long-noIsland sentences had a mode at the top of the scale, but many sentences were rated as less acceptable to some degree. In the corresponding Long-Island-RC dependency condition, the ratings are centered around the midpoint of the scale with substantial variance. If we compare judgments in the Long-Island conditions across dependency type, it appears that participants were more likely to give a high acceptability score to wh-movement from a conditional than RC-movement, despite the fact that an ‘island effect’ is only observed with wh-movement.

Figure 4.

Distributions of ratings for sentences in the Adjunct Island sub-design split by dependency type and condition.

3.4. Relative Clauses

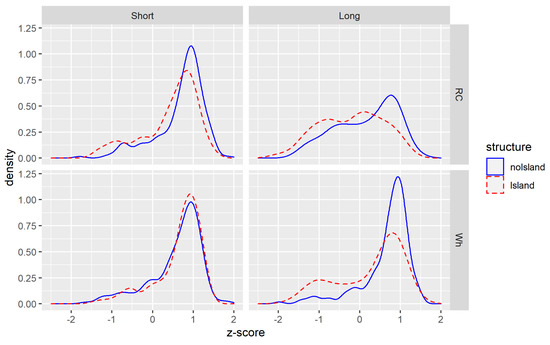

For Relative Clauses, the Structure × Distance × Dependency interaction was significant in the LMEM ( = −0.44, t = −2.29, p = 0.0368) and marginally significant in the CLMM ( = −2.16, z = −1.89, p = 0.0587). Resolving the three-way interaction revealed Structure × Distance interactions for both RC- (LMEM: = −0.95, t = −9.22, p < 0.0001; CLMM: = −5.48, z = −5.3, p < 0.0001) and wh-dependencies (LMEM: = −0.51, t = −2.8, p = 0.0145; CLMM: = −2.95, z = −3.44, p = 0.0006). The interaction observed for RC-dependencies resembles a standard island effect, such that the Long-Island condition is rated significantly worse than the Long-noIsland condition. The interaction with wh-dependencies does not resemble the typical interaction pattern. First, there is not a signficant difference between the average acceptability of the Long-Island and Long-noIsland conditions. The interaction appears to be driven entirely by extremely high acceptability ratings in the Short-Island condition. We attribute the high ratings to the relative simplicity of the structures used in these conditions. As discussed in Section 2.1, we were forced to deviate from a strict factorial design in the Short-Island condition. Therefore it seems inappropriate to use DD scores to quantify the ‘RC island effect’. Instead, the most informative comparison for determining whether there is an island effect is to compare the mean ratings in the Long-Island (z = 0.59) and Long-noIsland (z = 0.60) conditions. We interpret the negligible difference between the two Long conditions as evidence that there is no island effect for wh-extraction from an existential RC.

Rating distributions by condition are presented in Figure 5. Similar to other domains, Short conditions received consistently high ratings. Looking at wh-dependencies where we observed no island effect, we see that the Long-Island and Long-noIsland distributions are nearly identical, indicating that participants did not distinguish wh-movement from a declarative complement clause from an existential RC. Interpreting the ratings of Long RC-dependencies is less straightforward. Participants generally rated sentences from the Long-noIsland condition high, indicating that they judged RC-movement from a declarative complement clause acceptable. Ratings of RC-movement from existential RCs, however, show considerable variation and no clear mode. Insofar as the distribution is clearly different from the Long-noIsland condition, the conclusion that there is an island effect of some sort is supported. It seems, however, that the island effect does not reflect uniform rejection of the dependencies (as seen with movement from subjects).

Figure 5.

Distributions of ratings for sentences in the Relative Clause sub-design split by dependency type and condition.

4. Discussion

We found that statistically significant Distance × Structure effects varied by domain and dependency type. These ‘island’ effects indicate that some extractions resulted in decreases in acceptability that could not be accounted for by main effects of Structure and Distance alone. We found that significant effects (i) often reflect highly variable judgments in the ‘island-violating’ Long-Island condition and (ii) do not always entail that ‘island violations’ are unacceptable in absolute terms. In what follows we discuss effects by domain and how our results align with predictions of the FBCC.

4.1. Subjects

We observed large island effects for both RC- and wh-extraction from the subject phrases we tested. We saw that the size of the island effects differed by dependency type, but we reasoned that the statistically significant differences were not practically or theoretically meaningful in that participants reliably rejected RC- and wh-dependencies into subjects. Regardless of its origins, the subject island effect provides a benchmark for a large, consistent island effect against which we can compare other effects in the study.

We do not draw conclusions about whether the island effect we observed is consistent with the predictions of the FBCC because our items used preposition stranding, which Abeillé et al. (2020) argued was unacceptable for independent reasons. We point out, however, that if preposition stranding causes the problem, the explanation for the unacceptability cannot be that readers could not locate the gap site. The stranded preposition marked the gap site very clearly. It is also unlikely that the explanation can be linked to a preference for pied-piping, since pied-piping is not an option in Norwegian RC-dependencies, and it is not used in wh-questions in standard varieties.

4.2. Embedded Questions

Replicating the findings of Kush and Dahl (2020), we found that relativization of a subject from an EQ did not result in a significant island effect. We observed a significant island effect for wh-extraction from the same EQs, though this island effect was smaller (DD = 0.49) than our subject island effects (DDs = 1.14). Since we replicate the absence of an island effect for relativization, we conclude that the ambiguity between demonstrative relativization and clefting did not have an effect on the acceptability of extraction from EQs.

Although there was an island effect for wh-movement, the effect was largely due to differences in the average acceptability of wh- and RC-extraction from declarative complements. The average acceptability of wh-extraction from EQs was not significantly different from RC-extraction from the same EQs. Further, judgments of wh-extraction and relativization from EQs exhibited nearly identical variability.

If EQs are more backgrounded than declarative complement clauses, the FBCC predicts that we should see a penalty for wh-extraction from an EQ compared to wh-extraction from a declarative complement. A comparable penalty should not be observed for RC-extraction. A proponent of the FBCC might interpret the island effect we observed as consistent with this prediction.

We think, however, that there are also reasons to treat the interaction with caution. First, the small interaction effect could simply be an artifact of a ceiling effect. As discussed, the interaction emerges for wh-dependencies because there is a pairwise difference between the Long-noIsland and the Long-Island conditions, but not between the Short conditions. However, both Short conditions are rated essentially at the top of the scale, where potentially meaningful acceptability differences may be compressed. Second, the the average acceptability ratings and their distributions in the Long-Island condition were nearly identical for wh- and RC-extraction. The similarities make it hard to conclude that participants perceived wh-extraction as ‘worse’ than RC-extraction.

4.3. Adjuncts

We found that relativization from a conditional adjunct did not result in a significant island effect, similar to English results from Sprouse et al. (2016).

Wh-extraction yielded a statistically significant island effect, but the effect was small (DD = 0.44) because the mean rating of wh-extraction from a conditional (z≈ 0.25) was relatively high. It was above the average rating of the good fillers in the experiment and significantly higher than the average rating of relativization from a conditional adjunct. Thus, wh-extraction from conditionals appears to be, on average, ‘acceptable’ despite the island effect. The distribution of judgments confirmed that most participants considered wh-extraction from an adjunct to be acceptable more often than not: Participants rated the sentences near the top of the scale on the majority of trials, though they rated the sentences at the bottom end of the scale on the rest of trials.

We now turn to how our results square with the FBCC. The absence of an island effect for relativization from conditional adjuncts is consistent with the FBCC insofar as the FBCC does not predict island effects for relativization from any constituent. The significant island effect for wh-extraction is potentially consistent with the FBCC.

Once again, we think that the interaction effect, and the judgment distributions underlying that effect, do not unequivocally support the FBCC. We saw that the relatively high mean rating of wh-extraction from an adjunct was the result of averaging over a judgment distribution that had a mode at the top of the scale and a smaller proportion or judgments at or below zero. That is, participants were more likely, on balance, to judge wh-extraction from an adjunct just as acceptable as from an embedded declarative. If conditional adjuncts are uniformly backgrounded, we would expect a reliable penalty for wh-extraction from them: participants should have rated wh-extraction from an adjunct to be less acceptable than from a declarative on a majority of trials. This is not what we see. It seems instead that insofar as there is a penalty, it is observed inconsistently, on a small number of trials.

A proponent of the FBCC could accommodate the inconsistent unacceptability of wh-extraction, by letting the backgroundedness of conditional adjuncts vary. Under this interpretation, participants rated wh-extraction from conditional adjuncts acceptable on trials where they interpreted the conditional as part of the focus domain and rejected wh-extraction on trials where they interpreted the adjunct as backgrounded. If variability in backgroundedness is behind the judgment variability we observed, there is a simple prediction: there should be a negative correlation between individual items’ backgroundedness as measured by the negation test and the acceptability of wh-movement from those adjuncts.15 We have not conducted the experiments to confirm or falsify this prediction, but have made our items and data publicly available on the project’s OSF page to any researchers who are interested in conducting the experiments.

Finally, it should be noted that our results, which seem to suggest that wh-extraction from a conditional is largely acceptable, appear to conflict with the results of Kush et al. (2018), where wh-extraction from conditional adjuncts resulted in large, consistent island effects across three experiments. What is responsible for the differences in extractability? We do not have an iron-clad explanation for the discrepancy, but we suspect that lexical differences between items used in the studies may have played a role: The current experiment adapted adjunct items from Bondevik et al. (2021), which differed from those used in Kush et al. (2018) in two potentially relevant ways. First, items in Bondevik et al. (2021) were constructed relative to a context sentence, which may have indirectly led to more ‘natural-sounding’ items than those used in Kush et al. (2018). Second, items in Bondevik et al. (2021) and our study used a very restrictive set of predicates in the main clause. In all Island conditions, the matrix verb was bli (‘become’), followed by an adjective describing an emotional state (e.g, ‘happy’, ‘angry’, ‘nervous’ and ‘surprised’). In Kush et al. (2018) a wider set of matrix predicates was used (‘complain’, ‘sigh’, ‘protest’, ‘worry’ and ‘become happy’). If the matrix predicate influences the possibility of extraction from an adjunct, as suggested by Truswell (2011) and others, the difference in predicate types could be the source of the apparent discrepancy in results. We encourage more systematic investigation of how different predicates influence the possibility of extracting from conditionals and other adjuncts and whether the observed cross-dependency differences in English would be attenuated with different predicates.

4.4. Relative Clauses

Participants rated wh-extraction from an existential RC just as acceptable as wh-extraction from a declarative complement clause. However, they rated relativization from an existential RC as significantly worse, on average, than relativization from a declarative complement. Where judgments of wh-extraction were consistently acceptable, judgments of relativization exhibited a large degree of variation, ranging across the scale from z = −1 to z = +1.

As we discussed in the Materials section, existential RCs are non-presuppositional and are therefore not backgrounded. As such, the FBCC predicts that they should therefore allow wh-extraction. Our results are consistent with this prediction.

The island effect for RC-movement from existential RCs does not follow from any formalized account that we are aware of. According to the FBCC, RC-movement should, all else equal, be permissible wherever wh-movement is possible. Therefore, the source of the island effect must lie elsewhere. We do not have a concrete proposal for what additional factor(s) could be at play, but our results rule out a simple explanation grounded in complexity or dependency length. One possibility is that it is specifically the combination of demonstrative relativization and an existential RC that causes infelicity or unacceptability. If so, we might predict that sentences with eventive relativization would not be judged as unacceptable:

| (25) | Jeg likte faktisk ølet som det var mange som hata __ |

| I liked actually beer.def rel it was many rel hated | |

| lit. ‘I actually liked the beer that there were many who hated __.’ | |

| ≈ ‘I actually liked the beer that many hated.’ |

The variation in judgments also suggests that RC-movement from existential RCs may not be uniformly unacceptable. It is possible that item-specific factors, individual differences, or some interaction of the two modulate acceptability. For example, participants may have struggled (to varying degrees) to accommodate/imagine a supporting context for relativization across individual items (see Chaves and Putnam 2020 for more discussion). Providing a formal foundation for these intuitions should be one goal of future inquiry.

5. Conclusions

Our results show that wh- and RC-dependencies into nominal subjects are consistently unacceptable in Norwegian, but judgments of extraction from other domains show more nuanced patterns. We observed small island effects for wh-extraction from conditional adjuncts and embedded questions, but not for relativization from the same constituents. We argued, however, that the mere presence of significant island effects for wh-movement did not straightforwardly support the Focus Background Conflict constraint. Our results also suggest that other semantic/pragmatic factors above and beyond a simple focus-background partitioning are needed to explain cross-dependency differences in the acceptability of extraction (from domains such as existential RCs). We hope that the data we have collected can be used in the development of more fine-grained accounts of the factors that influence the acceptability of filler-gap dependencies in ‘island’ environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K., T.L., A.K., C.S.; methodology, D.K., C.S., T.L., A.K. and P.T.R.; formal analysis, A.K., P.T.R., M.V. and D.K.; data curation, M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., C.S., P.T.R., M.V., T.L. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K., D.K, C.S., P.T.R., M.V. and T.L.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by an Onsager Fellowship from NTNU to D.K.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study in accordance with the policies of the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) because the study collected no personal data which could be used to identify individual participants (either directly or by combining data).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to three anonymous reviewers for their constructive and helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCI | Backgrounded Constituents are Islands |

| C | complementizer |

| DEF | definite |

| EQ | embedded question |

| FBCC | The Focus-Background Conflict Constraint |

| NP | noun phrase |

| PASS | passive |

| PP | prepositional phrase |

| RC | relative clause |

| REL | relative pronoun |

Notes

| 1 | We use the common ‘filler-gap’ terminology and indicate the ‘gap’ site of extracted elements for ease of exposition. Such description does not necessarily entail commitment to an analysis where the relation between the filler and the verb read in (1-a) and (1-b) is mediated via an empty element such as a trace or where the filler is related directly to the head itself as it would be in trace-less theories (e.g., HPSG, Pollard and Sag 1994); LFG, (Kaplan and Bresnan 1995), or Construction Grammar (Goldberg 1995). |

| 2 | An alternative is that the constraints apply to the structure-building mechanisms themselves. See Nunes and Uriagereka (2000); Stepanov (2007); Uriagereka (1999). |

| 3 | According to Abeillé et al. (2020), the size of the acceptability decrease can vary—presumably corresponding to the degree of infelicity. |

| 4 | Other baseline sentences were used in these experiments, but we omit them from discussion to focus on the critical comparisons. |

| 5 | For example, we do not think that there is less ambiguity about the true gap site for an extracted PP than for an extracted DP/NP associated with a stranded preposition. If anything, the stranded preposition provides a clearer signal for the true gap site. As McInnerney and Sugimoto (2022) note, there is no independent motivation to assume that P-stranding should ever be harder than pied-piping, since the former is clearly the preferred option for extraction in English. We refer the interested reader to McInnerney and Sugimoto (2022) for an interesting alternate explanation of Abeillé and colleagues’ results, according to which the apparent cases of pied-piping from subjects are not cases of extraction at all, but rather instances of base-generated topic PPs. |

| 6 | It has been observed that sometimes extraction from relative clauses such as those in (11) is significantly less degraded in languages outside of the Mainland Scandinavian group including Hebrew, Italian, and even English (see, e.g., Cinque 2010; Kluender 1998; Kush et al. 2013; Lindahl 2017; Rubovitz-Mann 2000; Sichel 2018; Vincent 2021). However, recent experimental work suggests that the perceived acceptability of such sentences does not reflect a complete amelioration of island effects (see, e.g., Vincent 2021). |

| 7 | We have converted Faarlund’s examples into the Bokmål written standard to align with other examples across the paper. |

| 8 | A recent corpus study by Abeillé and Winckel (2020) found similar asymmetry for extraction out of subjects in French. |

| 9 | The preregistration can be found at https://osf.io/zksh6/. |

| 10 | A reviewer notes that the complements of verbs such as know and say can be interpreted as resolved questions, whereas the complements of rogative verbs such as wonder are interpreted as ‘open’ questions in the terminology of Ginzburg and Sag (2000). Insofar as the ‘resolved’ questions are interpreted as factive complements, they are potentially predicted to behave as more backgrounded than ‘open’ questions. Contrary to this prediction, island effects are more consistently observed with rogative verbs than with responsive verbs (Abrusán 2014; Pañeda and Kush 2021; Suñer 1991; Torrego 1984). |

| 11 | Christensen and Nyvad (2014) tested similar sentences in Danish. |

| 12 | In essence, existential RCs are similar in semantic content to mono-clausal declaratives such as ‘Many ordered beer’. Interestingly, Norwegian uses existential and presentational RCs (as well as clefts) more often than simple declaratives, presumably reflecting a preference to keep indefinites or new material out of surface subject position (see Diesing 1992; Johansson 2001). |

| 13 | We did not collect exact ages to minimize the amount of potentially-identifiable data we collected. |

| 14 | Due to a software error, participants were not prevented from proceeding to the next trial before giving a response. The small number of affected trials were relatively evenly distributed across participants, items, conditions, and place in the study. |

| 15 | Ambridge and Goldberg (2008) argue that ease of extraction from complement clauses correlates negatively with degree of backgroundedness as measured by the negation test, but in a recent larger study Liu et al. (2022) failed to replicate this finding. |

References

- Abeillé, Anne, and Elodie Winckel. 2020. French subject island? empirical studies of dont and de qui. Journal of French Language Studies 30: 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeillé, Anne, Barbara Hemforth, Elodie Winckel, and Edward Gibson. 2020. Extraction from subjects: Differences in acceptability depend on the discourse function of the construction. Cognition 204: 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrusán, Márta. 2014. Weak Island Semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, Diogo. 2014. Subliminal wh-islands in Brazilian Portuguese and the consequences for syntactic theory. Revista da ABRALIN 13: 55–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambridge, Ben, and Adele Goldberg. 2008. The island status of clausal complements: Evidence in favor of an information structure explanation. Cognitive Linguistics 19: 357–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]