Abstract

After decades of persistent dominance of monolingual approaches in language teaching, we are now witnessing a shift to pluralist pedagogical practices that recognize learners’ mother tongues (MTs) as a valuable resource. This paper examines data from 44 questionnaire respondents and 4 interviewees to investigate teacher perspectives on using learners’ MTs in the classroom and the extent to which teacher education shaped their beliefs. The results suggest that while most of the participants stressed the importance of maximizing target language (TL) use, some of them also recognized the value of employing MTs for specific purposes, such as anchoring new learning, providing grammar explanations and task instructions, decreasing student and teacher anxiety, sustaining motivation, and supporting learner identity. Most participants agreed that their teacher education program exerted some influence on their beliefs and practices, but their personal experiences as learners and teachers were also named as influential sources. The most notable change in views related to an increased use of the TL, which contradicts recent findings relative to the value of using learners’ existing resources. The paper concludes by stressing the need to examine the curricula and objectives of teacher education programs in the light of the current research on multilingualism in education.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Research Questions

English language classrooms around the world are becoming increasingly diverse and multilingual (Conteh and Meier 2014; Hammer et al. 2019; May 2013). Consequently, language teaching practices should enable multilingual students to draw on their previous knowledge and full linguistic repertoires (Flores and Aneja 2017; Lee and Levine 2020) as they are developing proficiency in English as an additional language (EAL). For many years, the integration of students’ mother tongues (MTs) in EAL classrooms was perceived as a borderline incorrect teaching practice (Copland and Neokleous 2011; Hall and Cook 2012; Shin et al. 2020). Currently, however, there has been a pendulum shift towards multilingual and pluralist approaches which acknowledge optimal or judicious use of MTs as a valuable resource (García et al. 2017; Shin et al. 2020). Consequently, there is a need to re-examine EAL teachers’ views about working with multilingual learners.

Teacher beliefs impact teachers’ choice of pedagogical practices (Borg 2006), and teacher education programs constitute one of the factors that impact teacher beliefs and practices (Borg 2011; Phipps 2007). Increasing numbers of teacher education programs have modified their curricula to include topics, modules, and courses that focus on multilingualism and language teaching in multilingual contexts (Hammer et al. 2019). This paper aims to examine teachers’ own perspectives on the role teacher education had in shaping their beliefs about pedagogical practices for teaching EAL in multilingual contexts. The study presented here addresses the following research questions:

- What are teachers’ beliefs about the use of learners’ MTs when teaching EAL?

- Do teachers feel that their teacher education has prepared them for teaching EAL in a multilingual classroom?

- To what extent do teachers base their teaching practices on the knowledge acquired through teacher education? What do teachers believe about the impact of teacher education on their views about the role of learners’ MTs in the teaching and learning of EAL?

1.2. Terminology

Before we proceed with a brief review of the literature, it is important to shed light on the terminology adopted in this paper. Several terms are used in the literature to delineate the language(s) people are exposed to from birth; namely, MT, first language, native language, home-language, own-language, heritage language, and even minority language. While these terms are often used interchangeably, they have been under scrutiny, with researchers highlighting the connotations associated with some of them (Hall and Cook 2012; Shin et al. 2020). Hall and Cook (2012) opted for the term own-language(s) to identify the language students speak best in lieu of first language, MT, and native language. As they elaborated, the terms first and native language might not represent classroom reality as the common shared language is often not the students’ first and/or native language. Additionally, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish a student’s first/native language when two or more additional languages are learned simultaneously. Furthermore, the term MT is believed to have emotive connotations although it is not necessarily a language spoken by a person’s mother. The term first language is not necessarily used to illustrate the language students learn first but the first language out of the students’ entire linguistic repertoire that first comes to their minds. The term heritage language is typically used to denote a language other than the dominant societal language to which speakers have some historical or personal connection, regardless of the level of proficiency (Valdés 2001). Heritage language may be preferred in lieu of minority language because of the latter’s emotive charges. By definition, minority language, as opposed to the majority, is interpreted as the language that is spoken by a small group of people in a country. The term is problematic because as Viaut (2019) pointed out, it primarily centers on ‘the territorialized legitimacy of a language’ (p. 169). Eisenchlas and Schalley (2020) argued that none of these terms “appears to be able to capture the different dimensions encountered in research and practice” (p. 17). For this study, however, the term MT is used to portray the language that is most often employed by a family for their everyday interactions. In the context of the present project, this includes Norwegian and other languages which are spoken by families of immigrant backgrounds in Norway. However, no distinction is made between Norwegian and these other languages for the purpose of data collection and analysis. The term target language (TL) is used to indicate the language students learn in a classroom.

Norwegian English language teaching (ELT) classrooms are often perceived as EFL, but English has acquired a status that vacillates between EFL and ESL (Simensen 2005). English language is a mandatory subject for students for eleven years, beginning in grade 1, with its own curriculum that is separate from other foreign languages (e.g., German, Spanish) also taught in school. Although English does not have an official status in the country, it plays an important role in work and higher education, and its impact outside the classroom is ubiquitous. Therefore, it has been postulated that Norwegian ELT classrooms should be identified as ESL settings (Rindal 2014; Simensen 2005). However, to avoid the oscillation between the terms EFL and ESL, but also to illustrate the fact that Norwegian classrooms are becoming increasingly multilingual, in this paper, we have opted for the term EAL.

1.3. Literature Review

EAL instruction has primarily been conducted through the medium of the students’ MT(s) in monolingual environments (i.e., classrooms with a shared common language) (Hall and Cook 2012; Shin et al. 2020). In these contexts, teachers have often adopted the grammar-translation method, which includes activities that rely on the direct translation from TL to the students’ MT. However, the emergence of new teaching approaches that foregrounded interaction amongst students (e.g., Communicative Language Teaching, Richards 2006) placed a more prominent role on the use of the TL (Hall and Cook 2012; Shin et al. 2020). Krashen’s (1985) input hypothesis that put forward that students should immerse themselves in an environment that makes exclusive use of the TL constituted a further incentive for EAL classrooms to shy away from the recourse to the MT (Hall and Cook 2012). The popularity of the input hypothesis, along with the application of the new communicative teaching methodologies, cemented the idea that an EAL classroom should rely on the use of the TL (Shin et al. 2020). This reliance was often interpreted and perceived as prohibiting the integration of the MT (Hall and Cook 2012; Shin et al. 2020). The exclusive role that the TL should serve in the EAL classroom was also evidenced in national curricula (e.g., The Curriculum Development Council 2004; Kim 2008) in countries such as South Korea and Hong Kong that prescribed exclusive usage of the TL.

Despite the assumption that an all-English approach constitutes the ideal conditions for language acquisition, research studies that ventured to explore the teacher and student perspective revealed that the MT held a prominent role in the EAL classroom (Izquierdo et al. 2016; Shin et al. 2020). The studies described classroom environments where the MT ranged from sporadic utterances to lessons conducted in their entirety in the MT. The MT fulfilled different purposes in the classroom. For example, it was used to exemplify grammar and introduce vocabulary (e.g., Nukuto 2017), while it was also employed on an affective level to strengthen the relationship between teacher and students (e.g., Tsagari and Diakou 2015). The most common classroom function that the MT served was to offer translations in the students’ MT. While research revealed EAL teachers’ trenchant critique on resorting to translations (e.g., Copland and Neokleous 2011), recent studies displayed the benefits this practice can exert on TL acquisition (Ahmed 2019; Duc Hoang 2021). Translating to the students’ MT can assist in pinpointing the accurate meaning of newly introduced vocabulary but also complex grammatical structures.

Research studies that explored the student perspective revealed that students hold a positive stance towards the use of the MT in the EAL classroom, with the learners underlining the positive impact it could have on students’ language development (Hlas 2016; Liu and Zeng 2015; Neokleous and Ofte 2020; Nukuto 2017). In fact, the participants in these studies acknowledged the value of using the MT in the EAL classroom as an important aid and tool that would assist in the clarification of complex TL concepts (Tian and Hennebry 2016). However, the EAL students in these studies also underlined the importance of exposure to the TL (Izquierdo et al. 2016; Neokleous 2017). For the students, the classroom constituted the possibility of practicing the language through interaction with their peers. While the MT could assist in ensuring comprehension of key parts of the lesson and contribute to TL acquisition, the student participants also cautioned about the possibility of MT overuse (Shin et al. 2020; Thompson and Harrison 2014). This concern was also echoed by EAL teachers in studies that attempted to unearth their perspectives (Copland and Neokleous 2011). As the authors elaborated, the teachers felt that making frequent recourse to the students’ MT could potentially restrict them from seeking new opportunities to demonstrate their students’ new grammar and vocabulary. Most significantly, they continued, the reliance on the MT could lead to students always expecting their teachers to provide the equivalent in the MT and restrict opportunities for students to unearth the meaning themselves.

Research has also revealed that students’ grade level could also play a decisive role in the amount and frequency of MT used in the classroom (Moore 2013; Thompson and Harrison 2014). Advanced learners of English seemed to rely less on their own but also on their teachers’ MT usage whereas younger learners not only made recourse to the MT more frequently, but they also expected and required their instructors to integrate it into the lesson (Lin and Wu 2015; Tsagari and Diakou 2015). Younger EAL learners described MT integration as a valuable and useful tool that helped them understand complex concepts and structures of the TL while it also enabled them to draw comparisons between the two languages, which is deemed as one of the greatest benefits of MT integration (Neokleous 2017).

However, studies exploring the teacher perspective revealed that teachers’ attitudes toward MT integration are not always aligned with their students’ beliefs on the topic (Hlas 2016; Neokleous et al. 2022; Nukuto 2017; Shin et al. 2020). While in most studies, the teacher participants acknowledged the benefits associated with MT use, particularly when dealing with grammar, they expressed their ambition to create classroom settings that offer maximum exposure to the TL. Most surprisingly, some of the studies identified displayed traces of guilt amongst teacher participants for resorting to the students’ MT to illustrate or answer questions (Copland and Neokleous 2011; Neokleous and Ofte 2020). This tendency was often ascribed to the unpreparedness of the teachers to work in multilingual classrooms. For instance, Krulatz and Dahl’s (2016) study revealed teachers’ desire to undergo additional training with only 62% of the participants claiming satisfactory preparedness. More recently, Lorenz et al.’s (2021) study conducted in Norwegian classrooms highlighted the challenge that the increasing number of multilingual students presents and the need for practical applications to be considered during teacher training.

Along with students highlighting the benefits associated with MT integration, the current multilingual and multicultural nature of EAL classrooms further underscores the pivotal role the students’ MTs could play (García and Lin 2017; Otheguy et al. 2018; Wei 2018). Researchers reevaluated MT integration and asserted that EAL instructors should aspire toward judicious or optimal MT use as it is believed to facilitate TL acquisition. While the definition of optimal use of the MT remains vague, Shin et al. (2020) stressed that “the amount of L1 use should be judged by its purpose, content, and task styles when considering how to support L2 learning” (p. 414). However, the presence of a range of MTs in the classroom contributed to the development of pedagogical strategies that embrace the students’ entire linguistic repertoire as a useful tool and resource in optimizing the TL learning experience. The pedagogical strategy of translanguaging, defined as the students’ ability to make use of their entire linguistic repertoires as one single unit without adherence to the conventional boundaries of named languages (Wei 2018), transfers into the classroom the dynamic and fluid languaging practices of bi/multilingual children. Wei (2018) argued that the practice of translanguaging “emphasizes the interconnectedness between traditionally and conventionally understood languages” (p. 23) and enhances the notion of identity amongst bi/multilingual children. EAL instructors are encouraged to adopt translanguaging and implement it in their classrooms. However, research also points out that teachers should be adequately trained to develop a deeper understanding of the concept of translanguaging and how it can be effectively and efficiently used in the multilingual classroom.

It needs to be acknowledged, however, that classroom practices are closely associated with teacher beliefs about learners, learning, and teaching (Borg 2006; Raths and McAninch 2003). Teacher beliefs are influenced by a range of factors, of which, knowledge obtained through teacher education is just one of them (Raths and McAninch 2003). Other sources of influence include teachers’ own experiences as learners (Lortie 1975), local and national curricula, and teaching experience (Borg 2006, 2011; Phillips and Borg 2009). Additionally, teacher beliefs about language learning and teaching are impacted by the dominant language ideologies and the perceived values of learners’ MTs (Barcelos 2003; Fitch 2003). Research has shown that in cases where novel ideas and interventions were introduced, teachers were unlikely to adopt them if these clashed with what they were taught during their training (Raths and McAninch 2003). Taken together, in the context of language education, teacher beliefs and experiences lead to the construction of teacher ideologies, defined by Blackledge (2008, p. 29) as “the values, practices, and beliefs associated with language use by speakers, and the discourse that constructs values and beliefs at state, institutional, national and global levels”. The specific impact of teacher education on teacher ideologies is not well understood, and the present paper aims to address this gap.

2. Context, Materials, and Methods

This study was conducted with Norwegian EAL teachers. In Norway, English is taught as an additional language from Grade 1 and is obligatory for eleven years. For students whose MT is Norwegian, English is their second language, although these students may have been exposed to other languages such as Swedish and Danish outside of school, for example, on television. For immigrant students, whose numbers have been gradually increasing over the last few decades, English may be their third or even fourth language. They speak languages other than Norwegian at home and they learn Norwegian as a second language (NSL) at school.

This study utilized a questionnaire and an interview as data collection methods. The participants were selected via convenience sampling using respondents that were enrolled at a Norwegian institution either for pre- or in-service teacher training. Forty-four Norwegian EAL teachers responded to the questionnaire.1 There were 10 males and 34 females. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 54, and their teaching experience ranged from 0 to 15+ years. Participation was voluntary and no sensitive participant data were collected. While the study aimed to sample teachers of various ages and in different stages of experience (pre- and in-service), the sample size was insufficient to undertake any group comparisons. The study acknowledges that the sample might not be representative of the EAL teacher population in Norway. However, the results might potentially be relevant and applicable to similar educational contexts. Table 1 summarizes the background information about the questionnaire participants.

Table 1.

Questionnaire participant background information (N = 44).

The participants completed a paper-based questionnaire that examined their perspectives on using MTs in the EAL classroom and views relative to the extent to which teacher education shaped their beliefs. The questionnaire consisted of 22 open-ended questions, and the responses to 10 questions were examined to answer the research questions in this paper. The questions included in the analysis asked the participants to provide information about their beliefs and practices relative to the use of MT and TL in the classroom, about the impact of their teacher education on these beliefs and practices, and about their assessment of the usefulness of their teacher education relative to teaching EAL in multilingual contexts.

In addition, four teachers who did not complete the questionnaire were interviewed to obtain more in-depth responses to the research questions. The participants were asked to state their beliefs about teaching in a multilingual setting and to describe any experiences that significantly influenced these beliefs. They were also asked whether they use learners’ MTs when teaching and in what ways. The semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded, and the relevant excerpts were transcribed. The background information about the four teachers is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interview participant background information (N = 4).

The questionnaire and interview data were analyzed qualitatively using QSR International’s NVivo 12 analytical software, adhering to the principles of qualitative content analysis (Frey 2018). Three major themes were established deductively based on the research questions: (1) teacher beliefs about the role of MT; (2) the impact of teacher education on beliefs; and (3) the perceived usefulness of teacher education. Both the questionnaire and the interview data underwent a thematic, inductive analysis, during which specific codes emerged under each of the three pre-established categories. After the first round of coding, the codes were checked and grouped together under sub-themes (Table 3).

Table 3.

The coding categories for theme (1) teacher beliefs about the role of MT.

3. Results

The following three sections report the findings from the analysis of the questionnaire and interview data to address the three research questions. We first present the central themes that emerged from questionnaire data and then move to interviews to provide in-depth understandings relative to teacher beliefs about the role of MT, the perceived usefulness of teacher education, and the perceived impact of teacher education on those beliefs. We end each section by illustrating the general trends by giving extensive examples and vignettes taken untouched from the data.

3.1. Teachers’ Beliefs about the Role of MT in the EAL Classroom

The first research question aimed to examine the teachers’ beliefs about the role of MT when teaching EAL. In their responses to the open-ended questions in the questionnaire, the participants provided information relative to both their beliefs about the amount of MT used and the functions they believed that the MT can fulfill in the EAL classroom. By far, the majority of the participants believed that they needed to maximize the use of the TL. In fact, there were 96 references pertaining to the importance of maximizing the TL input in the data. Some of the teachers reported on their actual pedagogical practices. For example:

- I do not use the mother tongue. Students have to use and speak the language as much as possible (T3).

- A couple of years ago I just made up my mind—now I am going to speak English! And I stick to that plan (T14).

- In practice, I make sure to speak English in my class when teaching (T35).

Other respondents, however, referred to their goals and ambitions or gave recommendations, as illustrated in the excerpts below:

- I want to create an environment where we only speak English (T12).

- The teacher should try to be a good role model and speak as much English as possible (T23).

- English should be the primary means of communication (T31).

- It’s better to only speak English (T35).

The next prominent trend in the data pertained to minimizing the use of the MT. One of the prevalent themes was a concern that allowing MT use in the classroom deprives learners of opportunities to develop their skills in the TL. The following vignettes illustrate this finding:

- I keep the use of the mother tongue to a minimum as I believe that while making sense of English is more cognitively challenging to my students, it stimulates learning (T28).

- I think we should avoid it. The children need to be exposed to English (T29).

- Students cannot improve their English skills if they don’t practice. Therefore, I think there should be a minimal amount of mother tongue in the classroom (T40).

The interview participants also acknowledged their preference for maximizing TL use and minimizing MT use when working with multilingual learners. While one teacher believed that the TL could create a common cultural space within which learners could interact with no need to switch back and forth between TL and MT, three of the four interviewees attributed their lack of use of students’ MTs to their own low or entirely lacking proficiency in students’ MTs. These teachers believed that being able to understand or at least having some knowledge of students’ MTs was the precondition to using MTs in the EAL classroom. The following statements illustrate such beliefs:

- From my part, at the first, is I would have to be able to speak the language, which is, I mean, difficult. It would be very cool to be able to, but that’s not necessarily feasible (T45).

- It’s difficult since I don’t speak their home languages, so I don’t really know. I don’t have enough knowledge about their own languages, so no, I haven’t even thought about using their languages (T46).

- I don’t, because as I said, I have just three languages (T47).

Nevertheless, the questionnaire data suggested that some of the teachers felt that the MT could be used to the learners’ benefit in the classroom and recommended that the use of the MT and the TL should be balanced, as illustrated in the following comments:

- I think it’s best to use both languages (T17).

- When planning my lessons, I decide when I should use English and when I can use the mother tongue (T18).

There was a total of 89 mentions of some use or role of the MT in the questionnaire data. Of these, 15 teachers acknowledged that the MT constituted a valuable resource and should be activated as a steppingstone to new learning, as in the examples below:

- It is important to let children go via their mother tongue for support (T7).

- Mother tongue is the child’s base (T7).

- I think that the knowledge students have about language in their mother tongue is a good foundation (T27).

For seven of the teachers, it was also important to draw comparisons between the MT and the TL, for instance:

- I think it might be interesting for the students to learn and see the connections between the languages (T31).

- I think it is important to compare languages and look at similarities/differences (T37).

Other MT functions mentioned in the questionnaire data included introducing new words (e.g., It might be necessary to explain some words or expressions in the mother tongue), providing grammar explanations (e.g., I think it’s necessary when you have to explain difficult grammar), giving instructions (e.g., I sometimes find it necessary to use the mother tongue in order to ensure that all students understand instructions), increasing student understanding (e.g., I think it’s important to use the mother tongue if the students need clarification or if they don’t understand what is being said), increasing motivation (e.g., Using mother tongue is motivating), decreasing student anxiety (e.g., Some students get scared if they are not allowed to use their mother tongue), and decreasing teacher anxiety (e.g., Teachers should feel comfortable in the teacher role and speak English when they feel ready for it). Finally, eight of the respondents believed that it was necessary to use MT with young learners, whose English proficiency is not very advanced (e.g., First graders would need more translation to understand than tenth graders).

The interview material gave further insights into the specific benefits the teachers associated with the use of the MT and the functions the MT can serve in the classroom. T1 explained that it was of crucial importance for learners to understand the teacher and thus recommended that both the TL and MTs could be utilized. T47 referred to this combined use of MT and TL as a negotiation between her own beliefs about the best pedagogical practices and the recommendations of the national educational policy:

- Here in Norway, I think they’re focusing so much on multilingualism. The Norwegian schools they consider and see that the use of mother tongue will help their child to understand and learn the Norwegian language… As a teacher, I think it’s a little bit challenging. But as I said before, it depends maybe on that country and how the country looks into the multilingualism… In Norway, they give that importance.

T46 perceived knowledge of additional languages as a clear benefit to students and stated that she helped her students draw comparisons between the TL and their MTs. However, she pointed out that it was easier to practice such a multilingual pedagogy when teaching NSL to immigrant students that newly arrived in Norway rather than in her mixed EAL classrooms, as illustrated in the following statements:

- Not in the regular English class. I was a teacher in the [NSL] class, so I wanted to learn more of their languages, and I was happy to speak and compare Norwegian with their own languages. That was quite helpful for them. I see how it could be helpful in learning Norwegian, but then when they’re in [the EAL] class, they should also be good in Norwegian, like they should learn Norwegian, so it’s easier to use Norwegian to learn English, instead of using their languages.

- I’ve always known that is good for children to learn a lot of languages, because then they will have a lot of language knowledge in various languages. And, yeah, it’s a good principle, and for to remember the words, it’s a strength if you know a lot of languages.

It is worthwhile mentioning that T48 highlighted the function of MT as an identity marker, which seemed to be overlooked by the questionnaire participants, although it was linked to decreasing student anxiety, which was featured in questionnaire responses. By emphasizing the inseparable relationship between language and identity, T48 endorsed the importance and value of using MTs to create an inclusive and safe space that could facilitate students’ EAL learning. The following statement illustrates her advocacy for using MTs:

- As I’ve learned in my teacher education and have experienced that language and identity are closely connected, so it’s important to value the diversity and the language that students know, except for Norwegian, and that they can be just as important in the classroom. Because when we value these differences, students do learn better.

When asked about the challenge of practicing multilingual approaches in EAL classrooms, T48 acknowledged such difficulties by saying “it’s hard when you don’t speak their languages, but there are ways of doing it”. The teacher gave examples of practices she employed in her teaching such as writing identity texts, role playing, and relating new linguistic knowledge to previous knowledge in MT. She asserted that:

- It’s not like you have to engage in a whole big conversation, but as long as you know these little things, just to acknowledge that, I [as a teacher] know that you [the students] know more than me, or that you know more than just Norwegian.

3.2. The Perceived Usefulness of Teacher Education

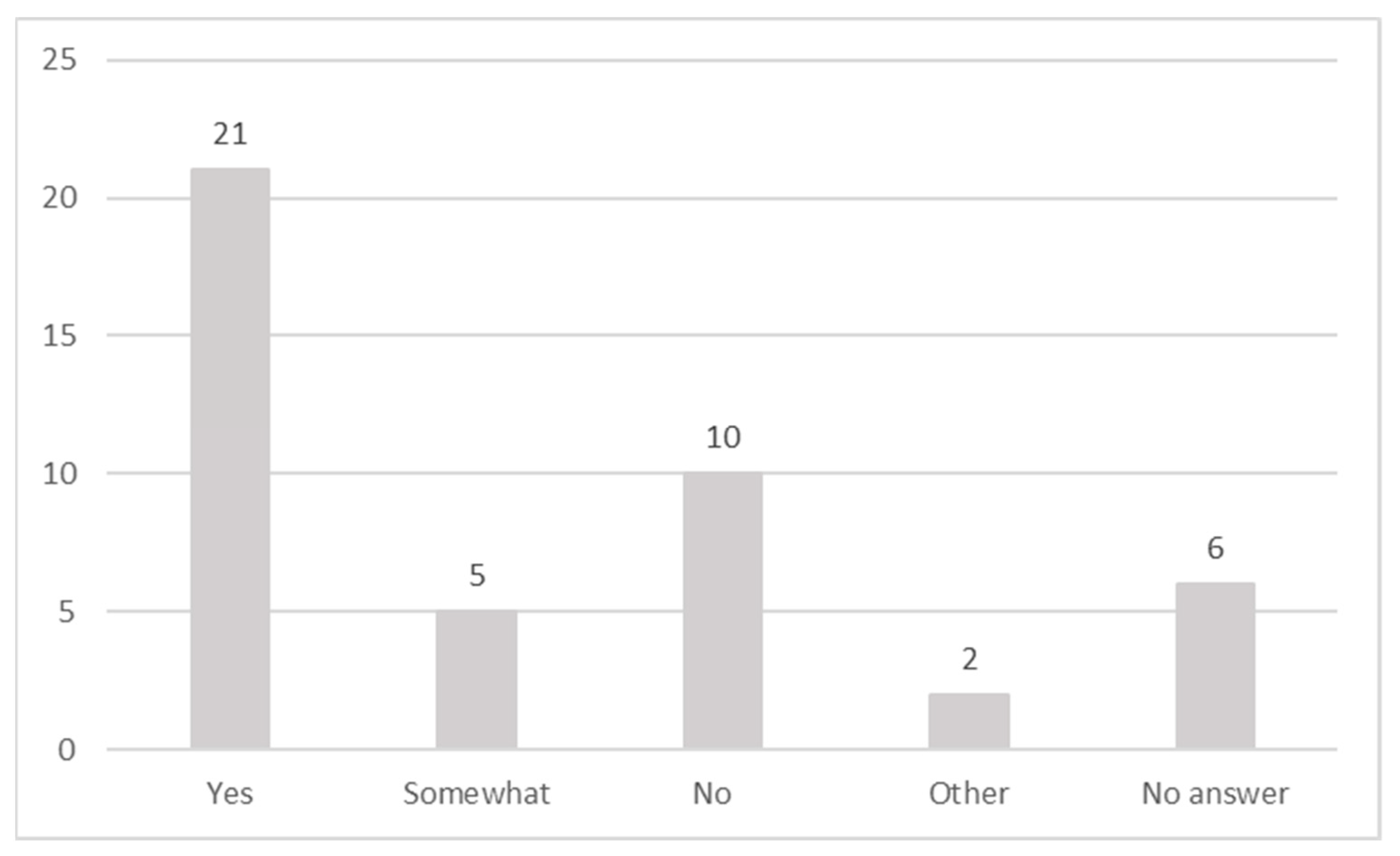

The second research question asked whether teachers feel that their teacher education has prepared them for teaching EAL in a multilingual classroom. Specifically, the teachers commented on whether teacher education helped them reevaluate their pedagogical approaches with respect to the use of MT in the EAL classroom. The data pertaining to this research question were coded as “Yes”, “Somewhat”, “No”, “Other”, and “No answer”. The results are visualized in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Teacher assessment of the usefulness of their teacher education relative to the use of MT in the EAL classroom (N = 44).

As can be seen, nearly half of the questionnaire respondents (N = 21) stated that their teacher education program prepared them for teaching EAL to multilingual learners, while five teachers found it somewhat useful, and ten did not find it useful at all. Two respondents provided other answers that suggested they did not understand the question, while six teachers left the space blank.

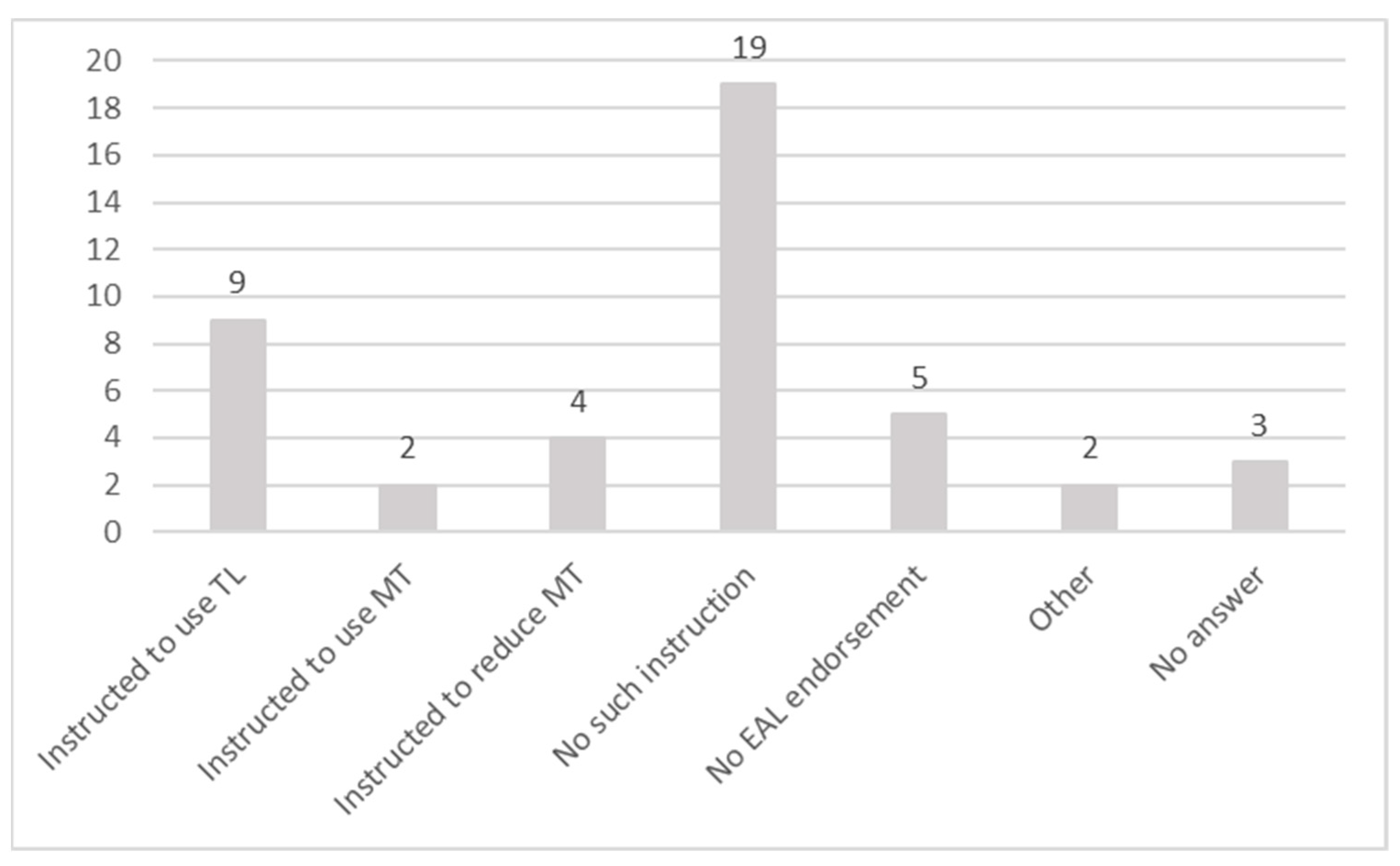

Finally, the questionnaire participants were asked if the role of the MT was explicitly discussed in their teacher education program and if so, what specifically were they taught. The responses were divided into the following categories: “Instructed to use TL”, “Instructed to use MT”, “Instructed to reduce MT”, “No such instruction”, “No EAL endorsement”, “Other”, and “No answer”. Figure 2 summarizes these findings.

Figure 2.

Explicit coverage of the role of MT in teacher education (N = 44).

Most of the participants (N = 19) admitted that they did not receive explicit instruction relative to the pedagogical functions of MT, while nine participants reported that they learned to maximize TL use, and four recalled being instructed to reduce the amount of MT. Only two teachers stated that they were instructed to use the MT. Two answers were placed in the category “other”. These included a teacher who recalled learning about both the advantages and disadvantages of employing MT and about how to balance the use of different linguistic resources and another teacher who could not recall exactly what they had been taught.

3.3. The Impact of Teacher Education on Teachers’ Beliefs

The third research question examined to what extent the participating teachers base their teaching practices on the knowledge acquired through teacher education and what the teachers think about the impact of teacher education on their views about the role of the students’ MTs in the teaching and learning of EAL. In total, 15 of the 44 participants indicated that what they had learned in their teacher education program impacts their pedagogical choices to some degree, with 6 asserting that the knowledge and skills obtained through formal education were very useful. The overall trend can be exemplified by the following vignettes:

- I have learned so much! I love to try it out in my classes (T3).

- The experience I have from teacher training is something I bring with me to my own class as I have seen a lot of things that work and things that don’t work (T28).

- I base a lot of my teaching on knowledge acquired in teacher training because everything I’ve learned is helpful and meaningful (T44).

Two of the interview participants (T46 and T48) also credited their teacher education and training for having triggered their transformation from employing TL only to using MTs, as illustrated in the following statements:

- This is something that I feel is very new to me, so I haven’t really been thinking about the importance of using their first languages as a resource in my teaching. And so that’s why I think [teacher professional development] is really good for me to be a part of, so that I can start thinking about it (T46).

- Yeah, earlier I would maybe be very strict, and I only spoke English in my class and no Norwegian. But after […] we talked about […] identity and language […], I feel it’s natural that we can also [include] some Norwegian in the English and vice versa, and even if the children speak other languages, they can use that language to help their learning. I don’t think it’s like we should only speak English anymore, which I did for a while (T48).

Only two of the questionnaire participants explicitly stated that what they had learned through teacher education bore no relevance to their current classroom teaching:

- Teacher training was theory based at such a level that educators cannot use it (T2).

- I think I learned very little about how to teach a foreign language (T9).

This perception was echoed in the interview data by T45, who stated:

- I don’t actively learn anything really, in kind of very passive way of learning…

The next large source of impact on pedagogical practice, however, was the teachers’ own experiences in the classroom as well as experiences as language learners. Sixteen interview participants indicated that this was the case, as illustrated in the examples below:

- I think personal experiences dominate my teaching (T9).

- I teach as I have been taught (T13).

- It’s personal experiences from all subjects I have taught (T29).

- I’ve also been a student and seen what works and what doesn’t (T38).

The influence of teachers’ previous language learning experiences on their current teaching was elaborated by all the four interview participants:

- I don’t think school has helped me very much with learning the languages and this is something in one way at least it has influenced my teaching practices in this sense that I would very much prefer my students to be able to hold a conversation in English and make themselves understood… I think my style of teaching is a very personal one. I don’t subscribe to the idea that you have to be a theoretical standing in front of the blackboard writing on the blackboard teacher… especially in English, it’s more important to be able to use the language in a constructive manner than it is to learn the grammar (T45).

- I have always been interested in the grammar part because I understood it quite early… because I like grammar so much that maybe I push a bit more on the grammar in my teaching (T46).

- So, the previous language learning experiences affected or not affected my teaching? They actually [did]. When I was trying to learn all these languages, for example, when I started learning Norwegian, I tried all the time to connect the words between English and Norwegian. [When it comes to teaching], yeah, I actually use connections between them (T47).

- Yeah, back then [when learning the languages] it was really like this: this is your Norwegian class, and this is your English class, and this is your German class and you do not mix them at all…. Yeah, so earlier I would, I would maybe be very strict, and I only spoke English in my class and no Norwegian (T48).

Nine of the questionnaire participants acknowledged that in their pedagogical practices, they drew on both the knowledge obtained through teacher education and the teaching experience they accumulated in the classroom. The following examples illustrate this trend:

- It is difficult to differentiate between what I’ve learned and what I’ve picked up through experience (T14).

- I base my teaching on both. I draw from personal experience on how to approach a subject, and from teacher training on more technical aspects of the language (T32).

- It starts out as something I learned but when applying it, I use my personal experience to modify it for the level of the students and my own capabilities (T43).

Other sources of impact on teaching practices mentioned in the responses to the questionnaire included ideas from colleagues, inspiration from professional groups on social media, and teacher companion guides to textbooks. In the interviews, while T47 acknowledged the influence of the multilingualism-focused policy on her use of students’ MTs, the other three teachers believed that it was important to consider the classroom reality, including the number of minority students, these students’ proficiency in the TL, and students’ attitudes towards their own MTs.

By far, the most prominent influence of teacher education pertained to the increased use of the TL. Twenty-three teachers commented in their questionnaire responses that they aimed to maximize their own and their student’s use of the TL because of what they had been taught in their program, as can be seen in the following comments:

- I have learned that I can explain English grammar in English (T6).

- I am more aware of using English only (T20).

- I am more focused on the importance of speaking English (T23).

- Before I completed teacher education, I was less aware of the many scaffolding methods available that can make the use of Norwegian, in many cases, redundant. Therefore, I saw the use of mother tongue as unavoidable. Now, as I am more aware of the benefits of extensive input and output, I believe one should strive to use English only (T29).

However, 11 of the questionnaire participants stated that they had not experienced any change in their beliefs about the amount of MT that should be used in the EAL classroom. In fact, about half (n = 5) of these teachers reported that their beliefs about the importance of TL use were reinforced through participation in teacher education courses. The following vignettes illustrate this theme:

- My beliefs have not changed. I always felt the same way. In my experience one can speak only English and still be understood by the students (T35).

- My beliefs are the same. I was always of the belief that you should speak English most of the time (T36).

- I always believed that English alone should be enough. Teacher education taught me the same thing (T41).

Other changes relative to the beliefs about the use of the TL and MT that the questionnaire participants ascribed to teacher education included increased MT use, balanced use of TL and MT, more reflective teaching, using task-based instruction to model and encourage TL use, and the importance of paying closer attention to giving clear instructions.

4. Discussion

Rooted in the tradition of studies that investigated language teacher attitudes to the use of the MT in the classroom, the present study set out to examine EAL teacher attitudes about the use of learners’ MT in the EAL classroom. Further, the study sought to explore whether their teacher education had prepared them for teaching EAL in the multilingual classroom and whether it had had an impact on their views about the role of the MT in the teaching and learning of EAL.

The study participants acknowledged the benefits associated with the integration of the MT in the EAL classroom. The main argument they put forward relied on the ability of the MT to ensure and deepen student understanding, particularly when they were required to introduce new vocabulary and complex grammar points. In such cases, the teachers were also in favor of making comparisons between the TL and the MT. These findings were also in sync with previous studies that explored teacher and student perspectives on MT use (Hlas 2016; Neokleous 2017; Nukuto 2017; Shin et al. 2020). Current research embraces and actively encourages teachers to make use of the students’ entire linguistic repertoires (e.g., Singleton and Aronin 2019; García et al. 2017; García and Kleyn 2016). This finding was corroborated by the interview data in the present study, as most of the participants attributed greater importance to maximizing TL use and minimizing MT use in the EAL classroom. In fact, they reported a preferred minimized MT usage when working with multilingual learners, which is in contrast with current research on multilingualism that promotes a classroom environment that is appreciative and inclusive of students’ linguistic repertoires (Krulatz et al. 2022; Singleton and Aronin 2019; Shin et al. 2020).

This preference for an increased use of the TL was also echoed in other studies conducted in Norwegian contexts. For instance, Vikøy and Haukås’s (2021) study disclosed that most of the Norwegian teacher participants perceived students’ multilingualism as a problem and thus rarely utilized students’ MTs as a resource. In addition, this negative view of the learners’ MTs was reflected by actual language use in Norwegian EAL classrooms. Similarly, Brevik and Rindal’s (2020) study revealed that languages other than the TL (English) and the language of instruction (Norwegian) were not employed in the classroom due to the dominance of these two languages in the academic domain and the society at large. Despite recent research encouraging multilingual approaches to EAL teaching, similar attitudes have also been reported in many classrooms around the globe with teachers still striving to implement English-only policies (Pennycook 2017). However, more recently, Neokleous and Ofte’s (2020) study in Norwegian EAL classrooms acknowledged teacher awareness of the benefits that may be derived from MT use, although their participants also expressed feelings of guilt for resorting to the MT in their lessons. As evidenced by research conducted in Norwegian EAL settings, the stigma associated with MT integration still seems to prevail among teachers. The pivotal role that students’ linguistic repertoires can have in enhancing TL acquisition has not been successfully communicated to teachers. For this reason, it is important that teacher-training programs focus more extensively on the ways in which the students’ MT can be integrated into linguistically diverse classrooms.

Nevertheless, some of the teachers (n = 9) in the present study stated that a balanced use of the TL and MT can be beneficial for learners. These teachers felt that the MT can be employed as a steppingstone to learning the TL (for example, via pointing out similarities and differences between MTs and the TL), or as a resource that improves student understanding, minimizes anxiety, and increases motivation. Thus, the teachers showed some evidence of their conceptualization of MT use as potentially beneficial to students in line with current research conducted in EAL classrooms around the globe (Hlas 2016; Krulatz et al. 2022; Naka 2018; Singleton and Aronin 2019; Shin et al. 2020; Tonio and Ella 2019). However, future research should aim to shed additional light on how EAL teachers could cater to the needs of students in Norwegian classrooms who are speaking increasingly diversified MTs. As classrooms in Norway are becoming increasingly linguistically and culturally diverse, most of the practices observed might not be in line with what multilingual approaches to teaching, such as translanguaging, recommend. Because both of our in- but also pre-service teacher participants have not yet been introduced to similar concepts and the pivotal role the students’ MTs could play in optimizing the learning experience, it might explain the hesitance about employing the MT in their lessons.

Relative to the second research question, even though almost half of the questionnaire participants (n = 19) stated that they did not receive any explicit instruction on the role of MTs in a multilingual EAL classroom, and further 13 were instructed to either maximize the use of TL or minimize the use of MT, nearly a half of the respondents (n = 26) indicated that what they learned in their teacher education program was useful or somewhat useful relative to the use of MT. This suggests that, even in courses where the use of MT is not directly addressed, some other information may be provided to pre- and in-service teachers that helps them draw conclusions about how to balance the TL and the MT for optimal instruction. These results point to the effectiveness of teacher education in changing teachers’ beliefs about the usefulness of MTs. However, they also confirm the persistence of monolingual-oriented approaches such as the TL-only policy which has tended to dominate educational contexts. Research has shown that teachers report an urgent need for additional training (Krulatz and Dahl 2016; Faez and Valeo 2012) and that the lack of instruction as to the pivotal role the MT can play in increasingly multilingual classrooms may further cultivate and promote pedagogical practices that rely on the monolingual bias with student teachers reporting a reluctance to use languages other than the TL (Portolés and Martí 2020). The importance of training on shaping student teacher beliefs about an optimized learning environment was also highlighted in recent studies conducted by Alisaari et al. (2019) and Portolés and Martí’s (2020).

The most important finding relative to the third research question was that more than half of the participants (n = 25) admitted that their teacher education program exerted some impact on their beliefs and pedagogical practices, with two teachers asserting that their teacher education enabled their transformation from TL-only approaches to employing MTs as a resource in the classroom. However, we are unable to pinpoint the exact impact teacher education could have on teacher beliefs about their attitudes and practices relative to MT use. Several previous studies revealed the influence the teacher training period can exert on student teachers (e.g., Cabaroglu and Roberts 2000; Debreli 2012). However, research has also concluded that the pre-existing set of beliefs of student teachers could remain unchanged (e.g., Abasifar and Fotovatnia 2015; Karavas and Drossou 2010; Peacock 2001). The participants in the present study identified their individual experiences as language learners, their teaching experience in the classroom, and inspiration from colleagues, social media groups, and teacher companion guides as other important sources of their pedagogical beliefs and knowledge.

As it transpires from recent studies unearthing the teacher perspective in increasingly multilingual settings, the pedagogies encouraged to be adopted in EAL education aim to not only promote foreign language acquisition but also enhance learners’ competence in other languages they know (Krulatz et al. 2022; Singleton and Aronin 2019; Shin et al. 2020). Yet, despite the paradigm shift towards adopting multilingual pedagogies in the classroom, in EAL settings where teachers did not undergo training on multilingual pedagogies, EAL teachers are still reluctant to fully embrace such an approach (Krulatz et al. 2022; Vikøy and Haukås 2021). Evidently, the challenges teachers are facing in the new multilingual and multicultural norm are met with the relatively stable nature of educational frames and policies. Even in teacher education programs that aspire to train prospective teachers to teach two or more languages, the recommended practices often continue to abide by a strict separation of languages. Although an increasing number of teacher education programs include instructional approaches and strategies that treat and assess students’ linguistic repertoire as a valuable tool, the universal acceptance of multilingual approaches as the norm is still a distant reality. Along with previous research unearthing teacher attitudes, the present study also pinpointed the pivotal role that EAL teachers’ training can play in the strategies and approaches they adopt in their lessons and can further cement the path towards the integration of multilingual and multicultural teaching. For this reason, it is useful for teacher training programs to foster teachers’ understanding of their key role as agents of change for a successful and efficient multilingual turn in language education.

5. Conclusions

With EAL classroom settings becoming increasingly multilingual, this study attempted to unearth the impact of teacher education on EAL teachers’ perspectives on using learners’ MTs. While some teachers acknowledged the importance of catering to their students’ needs and the ensuing advantages of employing the MT, most of the participants stressed the objective of abiding by an English-only approach. Some of the participants associated the use of the MT in the classroom with reduced opportunities to enhance TL acquisition. Acknowledging the impact of teacher education programs on teachers’ pedagogical practices, data from the participants revealed a lack of training on the positive role of the MT in the EAL classroom.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this project. First, as the number of participants was limited, it was impossible to examine the relationship between the participants’ age and their length of teaching experience and their views about the use of MT in the EAL classroom. Future studies should examine this issue. In total, 18 of the 44 participants were aged 18–25 and enrolled in pre-service teacher education. As some of these participants were in the early stages of their teacher training, it is possible that they had not taken relevant courses that tackle the question of MT use at the time of the study and that such courses are offered at some later stage of their respective programs. Additionally, as our definition of MT encompassed both Norwegian and other languages, we are unable to provide any insights into whether teachers view Norwegian and other languages differently. Finally, as we did not collect information about the languages spoken by the participants, we are unable to comment on the extent to which teachers’ potential competencies in students’ MTs impacted their ability and willingness to allow and employ these languages in the classroom.

Undisputedly, continued work is needed on this topic and particularly in increasingly multilingual and multicultural nations, such as Norway. The findings of this study have indicated that multilingualism would be one of the issues that Norwegian EAL classrooms will have to address as it is increasingly becoming the norm. The emergence of linguistically diverse classrooms demands cautious planning and competent teachers who optimize the learning experience of the students.

For this reason, teacher-training programs should re-assess their objectives and prioritize EAL pre-service teacher preparedness to work with multilingual students. Similarly, in-service teachers should undergo additional training that would strengthen their awareness of the catalyst role the use of the student MT can play in optimizing learning. What is also pivotal is for teachers to comprehend that each classroom is unique and there is no perfect or “one size fits all” approach. It is precisely for this reason that teachers should conduct individual action research projects that would help them shed additional light on the classroom practices and purposes their students’ MTs can serve in the classroom. Further, comparing and contrasting the results of these projects along with collaborative research conducted internationally would help paint a more adequate picture of the preferred MT practices. As a result, such projects could contribute to the alleviation of any negative attitudes that surround MT use so that language learning can become not only more inclusive and flexible but also more effective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and G.N.; methodology, A.K., G.N. and Y.X.; data analysis, A.K. and Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., G.N. and Y.X.; writing—review and editing, A.K., G.N. and Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for the questionnaire data in this study due to the age and full anonymity of the participants (no names, IP addresses, or contact information were stored at any point during the study). Ethical approval was obtained from the Norwegian Center for Research Data to collect the interview data (Report form 202376; date of approval 20 November 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | These participants received IDs 1–44. Interview participants’ IDs were 45–48. |

References

- Abasifar, Shirin, and Zahra Fotovatnia. 2015. Impact of teacher training course on Iranian EFL teachers’ beliefs. International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching & Research 3: 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Abdelhamid. 2019. Effects and students’ perspectives of blended learning on English/Arabic translation. Arab Journal of Applied Linguistics 4: 50–80. [Google Scholar]

- Alisaari, Jenni, Leena Maria Heikkola, Nancy Commins, and Emmanuel O. Acquah. 2019. Monolingual ideologies confronting multilingual realities. Finnish teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity. Teaching and Teacher Education 80: 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, Ana Maria Fereira. 2003. Teachers’ and students’ beliefs within a Deweyan framework: Conflict and influence. In Beliefs about SLA: New Research Approaches. Edited by Ana Maria Feireira Barcelos and Paula Kalaja. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 2, pp. 171–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackledge, Adrian. 2008. Language ecology and language ideology. In Ecology of Language: Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Edited by Angela Creese, Peter Martin and Nancy Hornberge. Doredrecht: Springer, vol. 9, pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, Simon. 2006. The distinctive characteristics of foreign language teachers. Language Teaching Research 10: 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, Simon. 2011. The impact of in-service teacher education on language teachers’ beliefs. System 39: 370–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brevik, Lisbeth M., and Ulrikke Rindal. 2020. Language use in the classroom: Balancing target language exposure with the need for other languages. TESOL Quarterly 54: 925–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaroglu, Nese, and Jon Roberts. 2000. Development in student teachers’ pre-existing beliefs during a 1-year PGCE programme. System 28: 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conteh, Jean, and Gabriela Meier. 2014. The Multilingual Turn in Languages Education: Opportunities and Challenges. Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Copland, Fiona, and Georgios Neokleous. 2011. L1 to teach L2: Complexities and contradictions. ELT Journal 65: 270–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debreli, Emre. 2012. Change in beliefs of pre-service teachers about teaching and learning English as a foreign language throughout an undergraduate pre-service teacher training program. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 46: 367–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc Hoang, Doan. 2021. Learners’ Perspectives on the Benefits of Authentic Materials in Learning Vietnamese-English and English-Vietnamese Translation. In ICDEL 2021: 2021 the 6th International Conference on Distance Education and Learning. Edited by Mario Barajas Frutos and Rui Zhang. New York City: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 266–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenchlas, Susana A., and Andrea C. Schalley. 2020. Making sense of “home language” and related concepts. In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development. Social and Affective Factors. Edited by Andrea C. Schalley and S. Eisenchlas De Gruyter. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter, pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faez, Farahnaz, and Antonella Valeo. 2012. TESOL teacher education: Novice teachers’ perceptions of their preparedness and efficacy in the classroom. TESOL Quarterly 46: 450–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, Frank. 2003. Inclusion, exclusion, and ideology. Special education students’ changing sense of self. The Urban Review 35: 233–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Nelson, and Geeta Aneja. 2017. “Why needs hiding?” Translingual (re) orientations in TESOL teacher education. Research in the Teaching of English 51: 441–63. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, Bruce B., ed. 2018. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., vols. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Ofelia, and Tatyana Kleyn. 2016. Translanguaging theory in education. In Translanguaging with Multilingual Students: Learning from Classroom Moment. Edited by Ofelia García and Tatyana Kleyn. New York: Routledge, pp. 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, and Angel M. Y. Lin. 2018. Translanguaging in bilingual education. In Bilingual and Multilingual Education. Edited by Ofelia García and Angel M. Y. Lin. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, Susana Ibarra Johnson, Kate Seltzer, and Guadalupe Valdés. 2017. The Translanguaging Classroom: Leveraging Student Bilingualism for Learning. Philadelphia: Caslon. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Graham, and Guy Cook. 2012. Own-language use in language teaching and learning: State of the art. Language Teaching 45: 271–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Svenja, Kara Mitchell Viesca, and Nancy L. Commins, eds. 2019. Teaching Content and Language in the Multilingual Classroom: International Research on Policy, Perspectives, Preparation and Practice. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hlas, Anne Cummings. 2016. Secondary teachers’ language usage: Beliefs and practices. Hispania 99: 305–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, Jesús, Verónica García Martínez, María Guadalupe Garza Pulido, and Silvia Patricia Aquino Zúñiga. 2016. First and target language use in public language education for young learners: Longitudinal evidence from Mexican secondary-school classrooms. System 61: 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavas, Evdokia, and Mary Drossou. 2010. How amenable are student teacher beliefs to change? A study of EFL student teacher beliefs before and after teaching practice. In Advances in Research on Language Acquisition and Teaching: Selected Papers. Edited by Angeliki Psaltou-Joycey and Marina Mattheoudakis. Thessaloniki: Greek Applied Linguistic Association, pp. 261–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sung-Yeon. 2008. Five years of teaching English through English: Responses from teachers and prospects for learners. English Teaching 63: 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Krashen, Stephen D. 1985. The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. New York City: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Krulatz, Anna, and Anne Dahl. 2016. Baseline assessment of Norwegian EFL teacher preparedness to work with multilingual students. Journal of Linguistics and Language Teaching 7: 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Krulatz, Anna, Georgios Neokleous, and Anne Dah, eds. 2022. Theoretical and Applied Perspectives on Teaching Foreign Languages in Multilingual Settings: Pedagogical Implications. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jang Ho, and Glenn S. Levine. 2020. The effects of instructor language choice on second language vocabulary learning and listening comprehension. Language Teaching Research 24: 250–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Lu-Chun, and Wan-Yu Yu. 2015. A think-aloud study of strategy use by EFL college readers reading Chinese and English texts. Journal of Research in Reading 38: 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yingqin, and Annie Ping Zeng. 2015. Loss and gain: Revisiting the roles of the first language in novice adult second language learning classrooms. Theory and Practice in Language Studies 5: 2433–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, Eliane, Anna Krulatz, and Eivind Nessa Torgersen. 2021. Embracing linguistic and cultural diversity in multilingual EAL classrooms: The impact of professional development on teacher beliefs and practice. Teaching and Teacher Education 105: 103428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lortie, Dan C. 1975. Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- May, Stephen, ed. 2013. The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and bilingual education. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Paul J. 2013. An emergent perspective on the use of the first language in the English-as-a-foreign-language classroom. The Modern Language Journal 97: 239–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naka, Laura. 2018. Advantages of mother tongue in English language classes. Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics 42: 102–12. [Google Scholar]

- Neokleous, Georgios. 2017. Closing the gap: Student attitudes toward first language use in monolingual EFL classrooms. TESOL Journal 8: 314–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neokleous, Georgios, and Ingunn Ofte. 2020. In-service teacher attitudes toward the use of the mother tongue in Norwegian EFL classrooms. Nordic Journal of Modern Language Methodology 8: 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neokleous, Georgios, Ingunn Ofte, and Tor Sylte. 2022. The use of home language(s) in increasingly linguistically diverse in EAL classrooms in Norway. In Handbook of Research on Multilingual and Multicultural Perspectives on Higher Education and Implications for Teaching. Edited by Sviatlana Karpava. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 42–62. [Google Scholar]

- Nukuto, Hirokazu. 2017. Code choice between L1 and the target language in English learning and teaching: A case study of Japanese EFL classrooms. Acta Linguistica Hafniensia 49: 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia García, and Wallis Reid. 2018. A translanguaging view of the linguistic system of bilinguals. Applied Linguistics Review 10: 625–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, Matthew. 2001. Preservice ESL teacher’ beliefs about second language learning: A longitudinal study. System 29: 177–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2017. Translanguaging and semiotic assemblages. International Journal of Multilingualism 14: 269–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Simon, and Simon Borg. 2009. Exploring tensions between teachers’ grammar teaching beliefs and practices. System 27: 380–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, Shelley. 2007. What difference does DELTA make? Research Notes 29: 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Portolés, Laura, and Otilia Martí. 2020. Teachers’ beliefs about multilingual pedagogies and the role of initial training. International Journal of Multilingualism 17: 248–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raths, James, and Amy C. McAninch, eds. 2003. Teacher Beliefs and Classroom Performance: The Impact of Teacher Education. Greenwich: IAP. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Jack C. 2006. Communicative Language Teaching Today. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rindal, Ulrikke. 2014. What is English? Acta Didactica Norge 8: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shin, Jee-Young, Quentin Dixon, and Yunkyeong Choi. 2020. An updated review on use of L1 in foreign language classrooms. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 41: 406–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simensen, Aud Margit. 2005. Ja, engelsk er noe vi møter som barn og det er ikke lenger et fremmedspråk. Sprogforum. Tidsskrift for sprog-og kulturpædagogik 11: 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, David, and Larissa Aronin, eds. 2019. Twelve Lectures on Multilingualism. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- The Curriculum Development Council. 2004. English Language Curriculum Guide. Available online: http://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/curriculum-development/kla/eng-edu/primary%201_6.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Thompson, Gregory L., and Katie Harrison. 2014. Language use in the foreign language classroom. Foreign Language Annals 47: 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Lili, and Mairin Hennebry. 2016. Chinese learners’ perceptions towards teachers’ language use in lexical explanations: A comparison between Chinese-only and English-only instructions. System 63: 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonio, Jimmylen J., and Jennibelle R. Ella. 2019. Pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards the use of mother tongue as medium of instruction. Asian EFL 21: 231–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tsagari, Dina, and Constantina Diakou. 2015. Students’ and teachers’ attitudes towards the use of the first language in the EFL State School Classrooms. Research Papers in Language Teaching & Learning 6: 86–108. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 2001. Bilingualism, heritage language learners, and SLA research: Opportunities lost or seized? The Modern Language Journal 89: 410–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaut, Alain. 2019. An approach to the notion of “linguistic minority” in the light of the identificatory relation between a group and its minority language. Multilingua 38: 169–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikøy, Aasne, and Åsta Haukås. 2021. Norwegian L1 teachers’ beliefs about a multilingual approach in increasingly diverse classroom. International Journal of Multilingualism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Li. 2018. Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics 39: 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).