Abstract

This paper discusses verbal stem allomorphy in Romance within the framework of Distributed Morphology (DM). We will present several technical instruments provided by the framework, applying them to an analysis of Romance verbal forms, with a particular focus on stem suppletion with the verb go. We conclude that the best solution to the problem of form–function discrepancies, as they appear in suppletion (but not only), is a spanning approach. This approach operates at Vocabulary Insertion only, without any need for the assumption of further, often critically discussed, morphological processes, such as fusion or pruning.

Keywords:

verbal inflection; Romance; Distributed Morphology; allomorphy; spanning; suppletion; theme vowels 1. Introduction

The main aim of this research paper is the analysis of irregular verbal inflection in Romance within the framework of Distributed Morphology (DM; cf. Halle and Marantz 1993). In DM, morphosyntactic processes derive hierarchical structures combining roots and functional elements, and the outcome of syntax is then mapped onto morphophonological realizations (=vocabulary items) by a process called Vocabulary Insertion (VI). We will focus on verbal inflection, in particular on the forms of Romance go, in order to discuss possible problems in the context of VI where the mapping process includes allomorphy and cumulative exponence, as is the case with root suppletion.

Romance go-suppletion is one of those cases where locality effects and intricate morphological variation are found in the verbal domain, since there are cases where the suppletive pattern is dependent on the syntactic context (e.g., agreement, as in French, Italian; “contextual suppletion”, Hippisley et al. 2004) and cases where it is dependent on functional features inherent to the verb (e.g., TAM, as in Spanish; “categorial suppletion”, Veselinova 2006, 2017). In order to explain the differences in the patterns and structural interpretation of go-suppletion, we will explore different theoretical approaches that offer tools for the modeling of suppletion within DM and discuss their pros and cons. In line with Haugen and Siddiqi (2013, 2016), we argue that the assumption of nonterminal VI—i.e., VI that targets units taller than one syntactic terminal element—is the best option for explaining root allomorphy, since form alternation is, as a general rule, accompanied by a reduction in segments (cf. e.g., Vanden Wyngaerd 2018).

The overall aim is to investigate the cumulative exponence of the verbal forms concerned and the contextual conditions for root suppletion. It is commonly assumed that root allomorphy can only be triggered by elements that are (linearly) adjacent to each other. The question is which of the approaches available accurately predicts the distribution of forms without being too unrestrictive as far as context conditions are concerned. Our research questions in particular are:

- Research Question 1 (RQ1). How can TAM-triggered root suppletion be modeled?

- Research Question 2 (RQ2). How can suppletion triggered by φ-features be implemented?

The paper is structured as follows: in Section 2, we report on materials and methods used. In Section 2.1, we present the data, starting from the paradigm1 of go in Latin, extending the view to Romance. In Section 2.2, we introduce the DM framework and discuss several methodologically possible analyses for cumulative exponence and contextual conditions for root allomorphy (Section 2.2.1), embedded in different stages of theoretical thinking in DM, namely fusion (Section 2.2.2), pruning and allomorphic closeness (Section 2.2.3), and spanning (Section 2.2.4). In Section 3, we set out our analyses for several instances of Romance go within the framework of DM, presenting our results for each language in single subsections (Section 3.1 Spanish, Section 3.2 Italian, Section 3.3 French). In Section 4, the advantages of a spanning approach to Romance verbal inflection are highlighted, in particular insofar as this approach can model and maybe also explain the differences and properties in common of the Romance languages discussed.

2. Materials and Analyses: The Romance Data and the Instruments of DM

In this core section of the paper, we will first present an overview on the morphological shape of the movement verb go and its development from Latin to Romance; we will also discuss different types of suppletion (Section 2.1), which will serve as the basis of our analysis in Section 3. In Section 2.2, after an introductory part on cumulative exponence and contextual conditions (Section 2.2.1), we discuss three possible approaches to the problems posed by contextual suppletion within the framework of DM, namely fusion (Section 2.2.2), pruning (Section 2.2.3), and spanning (Section 2.2.4).

2.1. The Data: Go from Latin to Romance

The paradigm of the Latin verb go is quite regular (cf. Table 1) despite the following facts: First, Latin īre stems from one of the athematic verbs in Proto-Indo-European, i.e., many forms have no theme vowel (Th) between the stem and the verbal ending; and second, the lack of the Th is responsible for (stem) allomorphy (i.e., the so-called Wurzelablaut or root apophony; i.e., a sound change that conveys grammatical information as e.g., Engl. sing in the present tense vs. sang in the imperfect; cf. Leumann et al. ([1926–1928] 1977, p. 522ff) for the original distribution of the Ablaut of īre). This stem allomorphy can be grasped by the following rule: In the present system the stem is /i:/ before consonant and /e/ before vowel (except e, see the active participle īens). Before /t/, as in the third-person singular, this long I at some stage is shortened (it, but īt would be the older form, cf. Julia 2016, p. 62). In the perfect system it is /i/, as general rule. Forms with long [i:] in the perfect system are the result of phonological adjustment (e.g., [i:] < [i] + [i]).

Table 1.

Latin ī-re ‘(to) go‘: present and perfect system (cf. Leumann et al. [1965] 1972, [1926–1928] 1977).

In Romance instead, all languages and varieties have started with the loss of verbal forms of Lat. īre or have even completely lost it, substituting it by other roots. Verbal forms of Romance go stem thus from different Latin verbs: īre ‘to go’, ambīre/*ambitāre ‘to go around’ or ambulāre/amblāre ‘to go, to walk’ (>*andāre ‘to go around’, *allāre ‘to walk’), vādere/*vādēre ‘to go’, venīre ‘to come’ and esse ‘to be’.2 It is important to note that these Latin verbs belong to different Latin conjugation classes (CC) and some verbs are thematic (e.g., ambulāre > *allāre), whereas others count as athematic (e.g., īre and vādere). This is a fact that is still reflected in the modern Romance languages, as we will show in Section 3.

There is no Romance variety that retained the full paradigm of forms of īre. However, the Romance varieties reached different solutions. As can be seen from Table 2, suppletion with go varies in Romance with respect to (a) the number of verbs that are combined in the respective suppletive paradigm—it ranges between two verbs (e.g., Standard Italian) to three verbs (e.g., in some Rhaeto-Romance varieties)—and (b) the language-specific distributions of these verbs within the suppletive paradigm.

Table 2.

Different data samples for Romance go-suppletion3.

As can be seen from this sample, suppletion is sensitive to the grammatical context. In Spanish for example, go-suppletion is TAM-sensitive (also called categorial or inherent suppletion), but not φ-sensitive4: in the present tense, va- (< athematic CC) has taken over; in the imperfect, the future and the conditional forms derived from īre (< athematic CC) are found, but in the indefinido and categories pertaining to it, forms of the verb be (Lat. esse = athematic CC) appear. This is a case of overlapping suppletion (cf. Juge 2000), i.e., two different verbs share the same stems in certain cells of the paradigm; in Spanish, overlapping suppletion is also TAM-conditioned.

In Italian, in the present tense the singular (including the imperative) and the third-person plural have the suppletive form va- (< athematic CC), whereas all other cells of the paradigm have taken over the form and- (< thematic CC) and no trace of a stem derived from īre is left; i.e., Italian go-suppletion is sensitive to φ-features and to TAM.

In French, go-suppletion is both sensitive to φ-features and to TAM. In the present tense we find the same conditions as in Italian, but contrary to Italian, French has not extended all- (< thematic CC) to all of the remaining cells of the paradigm, but still retains forms derived from īre (< athematic CC) in the future and the conditional. This is noticeable, since as general rule, the conditional and the future (at least historically) go back to the infinitive (cf. Roberts 2009 for a discussion of the traditional accounts—e.g., Benveniste 1968; Rohlfs 1969; Tekavćič 1972—and for a formal account of the grammaticalization process). This is, however, not the case synchronically in modern French where the infinitive of go is aller.

Interestingly, suppletion sensitive to φ-features is only found in the present tense in Romance. There we find also other patterns, different from Italian and French, as e.g., in the Lombard dialect of Monza, where the second plural is the only form to have an and- stem in the present tense. Old Tuscan, in the present tense, has the same pattern as Old Italian, with the difference that instead of and- forms there still are traces of īre in the first and second plural (cf. again Table 2).

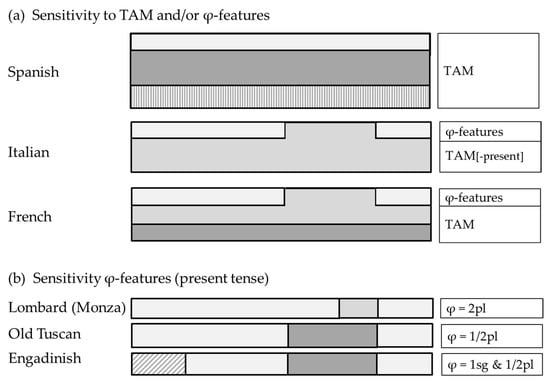

Another case of φ-sensitivity is found, e.g., in Rhetoromance, here Engadinish, where we have a distribution of forms derived from īre and and- forms as in Old Tuscan, with the exception of the first-person singular, where a verbal form of the verb come, namely veñ, is found (another case of overlapping suppletion). The distribution of the sample in Table 2 can be illustrated as in Figure 1a,b:

Figure 1.

The sensitivity of suppletion to TAM and/or φ-features.5

Of course, there are far more distributional patterns of go-suppletion in the Romance varieties and languages (cf. Pomino and Remberger 2019), which we cannot represent here. Furthermore, the use of go as a lexical verb encoding movement versus the use of go as an auxiliary (as in the Spanish progressive future, cf. e.g., Gómez Torrego 1999, or the Catalan preterite, cf. e.g., Detges 2004; Oltra-Massuet 2013) must be distinguished. However, since our paper is mainly concerned with the interpretation and analysis of root allomorphy (such as suppletion) and cumulative exponence (nonsegmentability) in Romance, in what follows, we will concentrate only on Italian, Spanish and French and we will consider only the use of go as a lexical verb.

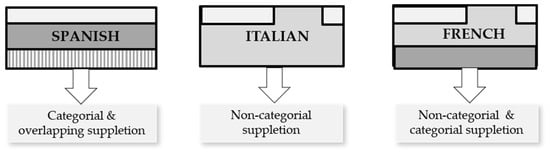

To sum up, Spanish has only TAM-sensitive suppletion, which is also called categorical (or inherent) suppletion, since it depends on categories inherent to the verb; Italian and French have additionally noncategorial (or contextual) suppletion, since φ-features are not primary categories of the verb, but contextually derived from agreement processes during the syntactic derivation (for the terminology, cf. Hippisley et al. 2004, as well as Veselinova 2006, 2017). Note again that noncategorial (contextual) suppletion, i.e., suppletion conditioned by φ occurs only in the present tense. Figure 2 shows the corresponding distributional patterns for go-suppletion:

Figure 2.

go-suppletion in Italian, Spanish and French.

The three languages, however, have in common that the respective paradigms of go contain roots going back to different Latin CCs, which are either thematic or athematic.

2.2. Instruments of DM for Cumulative Exponence and Contextual Conditions: Fusion, Pruning, Spanning

In DM (cf. Halle and Marantz 1993; for an overview, cf. Bobaljik 2017) a set of postsyntactic operations can alter the syntactic output before the vocabulary items (i.e., the morphophonological material) are inserted. Some of these processes are considered necessary to cope with different mismatches between syntax and morphology (cf. Haugen and Siddiqi 2016 for more details and arguments against these processes): (1) Fusion is assumed, for example, for portmanteau morphemes (e.g., French du, instead of *de le ‘of the’) and other cases where the syntactic output is more complex than the morphological formatives; (2) Fission, on the other hand, is proposed to account for more or less the opposite situation, i.e., for those cases where the form is more complex than the syntactic output, e.g., as in the Italian passato remoto in the third-person plural of the regular verbs, where the φ-node seems to be filled twice, i.e., is submitted to fission, which splits the φ-node into two positions, cf. irregular diss-e-ro ‘they said’ (where we have √say-Th-φ) vs. regular cant-a-ro-no ‘they sang’ (with two person–number suffixes, i.e., √say-Th-φ1-φ2) (cf. Calabrese 2015b); (3) Impoverishment is an operation that does not alter the number of syntactic terminal nodes but only the features contained therein, and has been used to explain, for instance, repairs of Romance Clitic Clusters (e.g., Spanish *le3.sg.dat lo3.sg.acc where the dative clitic le surfaces as (spurious) se, i.e., se lo) (cf. Bonet 1991); (4) Pruning is another process introduced to account for locality effects (on allomorphy): nodes that are not exponed with phonological material are removed from the structure directly after VI with a direct effect on (linear) adjacency (Embick 2010). In the following subsections we will exemplify and critically discuss these processes along Romance verbal inflection.

First, we want to point out that the assumption of these processes has been met with some criticism on the basis of the principle that (given equal explanatory adequacy) a smaller number of processes is preferable to a larger number (see Ockham’s razor); several efforts have thus been made to eliminate these processes (cf. Haugen and Siddiqi’s 2016 arguments in favor of a Vocabulary-Insertion-only programme for nonlexicalist realizational models of morphology). Fission can be avoided, for example, by allowing insertion into one and the same syntactic node more than once (cf. Halle 1997); impoverishment is not necessary, if insertion of zero exponents is allowed (cf. Trommer 1999), and fusion as well as pruning can be avoided, if VI is not limited to terminal elements, as in the nonterminal spellout of Nanosyntax (cf. Starke 2009) and the spanning approach of Svenonius (2012), among others. In what follows, we will not only show that fusion and pruning can be avoided, but also that they are not adequate for the analysis of suppletion in Romance. Before that we will introduce basic aspects of contextual conditions of allomorphy in the framework of DM.

2.2.1. Cumulative Exponence and Contextual Conditions

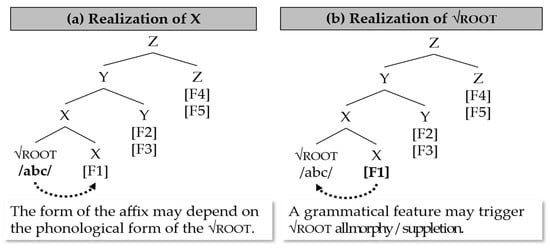

After the syntactic derivation, in DM, terminal nodes are handed over to VI. Vocabulary items are form-meaning correspondences and their insertion may be contextually conditioned by adjacent terminal nodes. Any context-induced surface variation of a morpheme could thus, in principle, be explained with VI. The contextual features triggering allomorphy are either phonological or morphosyntactic depending on whether the realization of the terminal node is inward- or outward-sensitive (cf. Bobaljik 2000). This idea is illustrated in Figure 3: when it comes to the realization of the terminal X, its form may depend on the phonological features of the vocabulary item previously inserted (and/or on following grammatical features). This is a case of inward context sensitivity, since the realization of X depends on the phonological shape of the root. In contrast, the realization of the root is outward sensitive. That is, the contextual feature [F1] of X, a grammatical feature, may condition root allomorphy (or suppletion) in (b).

Figure 3.

Inward (a) and outward (b) context sensitivity.

In this sense, suppletion of verbal roots is a case of outward context sensitivity, because the features triggering suppletion are the agreement features (in cases of noncategorial suppletion) or the TAM-features encoded in T° (in case of categorial suppletion). Yet are these features locally close enough to the root in order to trigger allomorphy? In other words, the question that arises is how we can correctly predict contextually conditioned allomorphy and restrict the conditions for the occurrence of suppletive roots. In particular, how far apart can the √root and the functional head encoding TAM or φ be to have a conditioning effect? Can T°, for example, and the grammatical features it contains trigger root allomorphy/suppletion, although it is not a direct sister to √root?

There are several proposals in the literature to grasp the locality conditions under which contextual allomorphy is possible. It is stated, for example, that two terminal nodes, α and β, are local enough if (a) no XP intervenes (Bobaljik 2012; Bobaljik and Harley 2017); (b) no overt node intervenes (Embick and Halle 2005; Embick 2010; Calabrese 2015a); (c) they belong to the same phase (Moskal 2015; Embick 2010); or (d) if they form a span (Svenonius 2012, 2016; Merchant 2015). In what follows, we will discuss some of these possible approaches to the problem at issue and show which additional postsyntactic processes are to be assumed. We will have a closer look at three processes, namely Fusion (Y can trigger root allomorphy only if it fuses with X and appears thus closer to the root), Pruning (Y triggers root allomorphy only if X is nonovert and is thus deleted, i.e., pruned) and Spanning (Y triggers root allomorphy only if it is in an adjacent span).

2.2.2. Fusion

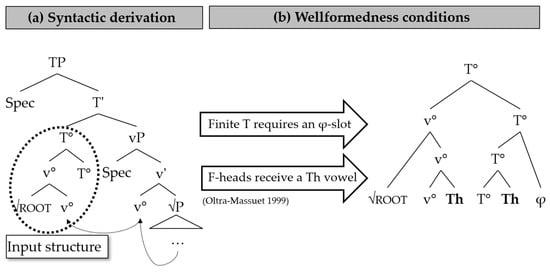

As said before, fusion is assumed for those cases where the syntactic output is more complex than the morphological formatives. Depending on the theoretical assumptions, the present tense forms of Romance are one example for this kind of mismatch between (morpho)syntactic structure and (morpho)phonological realization. We will therefore begin with the syntactic derivation and the input nodes it provides for VI of a finite verbal form in Spanish and Italian. After the syntactic derivation where movement of the root to v° and of the √-v°-complex to T° takes place, a complex T-node serves as the input structure to VI, cf. Figure 4a. In line with Oltra-Massuet (1999), we may assume that in Spanish and Italian there are, at least, two well-formedness conditions to be fulfilled before VI: As general rule, the φ-features that T° has acquired through person–number agreement with the subject in syntax receive their own slot for VI in Romance. In other words, finite T° postsyntactically requires an appropriate φ-feature position. Second, as has been claimed by Oltra-Massuet (1999) for Catalan, functional categories need to be equipped with a position for theme vowels. She proposes that a theme vowel position will be added to all syntactic functional heads, in our case v° and T°.6 That v° and the theme vowel are different VI can be seen in derivative forms such as Sp. atomizabamos or It. atomizzavamo ‘we atomized’, where after the realization of the root, the derivational suffix Sp. -iz- or It. -izz- is the vocabulary item for v° followed by the Th a, which marks the first CC.7

Figure 4.

Syntactic derivation (a) and well-formedness conditions (b) (cf. Oltra-Massuet 1999).

As a result of applying the mentioned well-formedness conditions, the syntactic output structure consisting of three terminal nodes (cf. Figure 4a) is augmented to a structure of six terminal nodes (cf. Figure 4b) to be realized by VI.

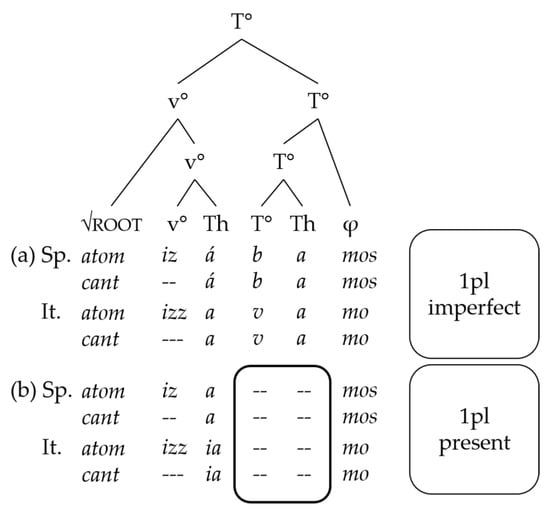

Figure 5 illustrates the realization of this structure for Spanish and Italian (note that French behaves differently with respect to theme vowels as we will show in Section 3; cf. also note 7). In the derived forms in the imperfect (cf. Figure 5a), morphological complexity stands in direct relation to the syntactic-semantic features of the respective forms (Oltra-Massuet 1999; Arregi 2000). Each input node is realized by a vocabulary item: In addition to the already mentioned realization of the root, v° and the theme vowel, imperfect T° is realized by Sp. -b- or It. -v-, again followed by a theme vowel selected by the vocabulary item for T°, and the φ-position is filled by Sp. -mos or It. -mo, since the agreement gave result to first-person plural features for φ. In the forms without a derivative affix, little v° is empty.

Figure 5.

Vocabulary insertion for the second-person plural in (a) the imperfect and (b) present in Spanish and Italian.

In the present tense, however, different from most other tenses, T° has no exponent, nor is there a theme vowel for T° (cf. Figure 5b).8 There is thus a mismatch between the number of terminal nodes and the available phonological material for the realization of this structure that has to be explained somehow.

Oltra-Massuet (1999) argues that this mismatch is not accidental, but has to do with the semantically unmarked tense feature. She proposes that heads containing only unmarked features are subject to fusion. She assumes that in the present tense, T° fuses with φ since it encodes a semantically unmarked tense feature, i.e., a tense feature that is also morphophonologically never realized. Note that in a certain sense, in the present tense, fusion reverses the well-formedness condition that consists in the addition of a separate φ-position proper to T°. After fusion of the present tense T° (which has no exponent) with the added φ-position, the φ-features appear under the fused T°/φ-head (cf. Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Fusion of T° and φ in the present tense according to Oltra-Massuet (1999).

Before we question the necessity of such an operation, let us come back to suppletion: As mentioned before, noncategorial (or contextual) suppletion is restricted to the present tense in Romance, and it is exactly in this tense where we find fusion, according to Oltra-Massuet (1999). We could be tempted to assume, thus, that suppletion/stem allomorphy is possible in this context because φ fuses with T°, becomes a sister to v° and thus can influence the selection of the VI for the root. In this sense, in the present tense, φ can locally condition the selection of different vocabulary items for the root.9

But, strictly speaking, even after fusion the φ-features are neither structurally nor (in most cases) linearly adjacent to the root, since there is always v° and the Th-position intervening. The only locality condition that is met is that there is no intervening XP (cf. Bobaljik 2012; Bobaljik and Harley 2017). What is more, why does φ trigger allomorphy only in the third-person plural and in the singular, but not in the first and second plural? In the fusion approach this would be mere coincidence, since fusion takes place in all persons. And finally, fusion is per se rejected by many linguists. First, as said before, in Oltra-Massuet’s analysis, fusion just reverses the well-formedness condition, i.e., a node is added to T° to ensure that some features of T° (the φ-features, which, as said above, are not primarily inherent to T° but derived from agreement processes) are realized independently from T° and shortly afterwards this position is fused with T° and they appear again where they originally were encoded. Would it not be more efficient to simply assume that in contrast to other tenses, in the present tense T° does not receive a separate slot for the realization of its agreement features? Second, a more general problem with the fusion approach is that it remains unclear what it is triggered by and how it is restricted. Oltra-Massuet (1999) also assumes fusion in other tenses where the semantic content of tense is certainly quite specific. In sum, fusion does not seem the appropriate means to alter the closeness of φ to other elements and to explain how root allomorphy can be triggered by φ-features.

2.2.3. Pruning

Pruning is a process introduced by Embick (2010) to account for certain locality effects on allomorphy: nodes that are not exponed with phonological material are removed from the structure after Vocabulary Insertion with a direct effect on linear adjacency (Embick 2010). To understand the necessity of this process, we will first discuss Embick’s assumption with respect to the locality conditions under which contextual allomorphy is possible after all. He assumes that allomorphy is restricted in the following two ways:

- Phase domains: Morphemes can interact for allomorphy etc. only when they are in the same phase domain.

- Linear adjacency: Morphemes can interact for allomorphy only when they are immediately linearly adjacent, i.e., concatenated: X⁀Y (Embick 2010).

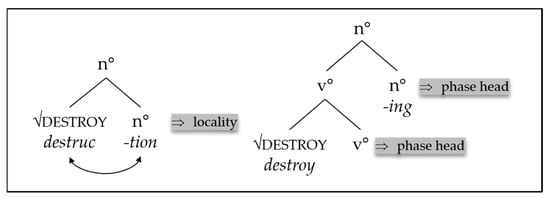

As for (1), domains correspond to phases: allomorphy can only occur when triggered in the same phase, i.e., in a locality condition. Even if linearly adjacent, elements belonging to different phases cannot trigger allomorphy. This is illustrated by the English examples destruction and destroying in Figure 7 (cf. Ingason and Sigurðsson 2015, p. 4; also Marantz 2013; Embick 2014):

Figure 7.

The domain hypothesis (Embick 2010, 2014).

In the case of destruction, the root and the nominalizer n° are in the same domain and thus they can trigger allomorphy on each other (cf. destruction not *destroytion). However, in the gerund, the root and the nominalizer are not in the same domain, since the phase is closed with the phase head v°. Therefore, root and nominalizer cannot condition allomorphy on each other—see the gerund destroying (not the hypothetical allomorphic form *destructing or something similar)—since here v° is an intervening phase head.

As for (2), according to Embick, allomorphy can only be triggered by linearly adjacent elements. Yet, linear adjacency, if not given, can be achieved through pruning: VI takes place at the linearized structure and nodes that are not exponed with phonological material are removed from the structure with a direct effect on linear adjacency (Embick 2010):

- 3.

- Pruning rule: √root⁀[x,-Ø], [x,-Ø]⁀Y → √root⁀Y (‘if x is not realized, it is pruned so that √root and Y become linearly adjacent to each other’)

At first glance, this proposal seems to work out for Romance suppletion, as illustrated with the French example allons in Table 3: Since v° and T° (and their possible theme vowels which we have omitted here for sake of simplicity, cf. also note 7) are not exponed in the French present-tense forms (cf. Table 3—b,d), they are pruned (cf. Table 3—c,e) and thus φ results to be linearly adjacent to the root (cf. Table 3—f), making φ-triggered root allomorphy possible, according to Embick (2010).

Table 3.

Derivation French allons based on Embick’s assumptions (simplified structure).

In sum, to make Embick’s proposal work, instead of a fusion rule one has to postulate a pruning rule. However, also here we encounter several problems, since there are additional claims to be made: Note that it is standardly assumed that VI starts in the most embedded element, i.e., the √root. But in Embick’s approach, v° (and also T°) has to be subject to VI and to pruning before the √root is phonologically realized, since otherwise, φ could no longer trigger allomorphy on the √root (once it is realized). Note, furthermore, that grammatical features are no longer available after VI. Therefore, the √root must be subject to VI before φ is realized since the φ-features must still be morphologically present in order to trigger the correct realization of the √root. In sum, the postsyntactic derivation must follow several ordered steps which appear to be somehow circular (see also below).

If we look at the Italian present tense forms in Table 4, one could think that the first-person plural and second-person plural trigger allomorphy on the root since all the other forms are based on va-. In Embick’s view this would not be possible, because in these cases φ and the √root are not linearly adjacent to each other: -ia- and -a- intervene between them (see also the imperfect forms in Table 4). Yet one could also assume that and- is the default realization for √go (as it is; see the other tenses) and that φ triggers allomorphy on the root in the first-, second- and third-person singular and the third-person plural, where √go and φ are linearly adjacent to each other. Note that in these va-based forms there is no intervening exponent and φ and the √root are linearly adjacent. However, singular and third-person plural do not represent a natural class (for a solution to this problem, see Section 3).

Table 4.

Present tense and imperfect of go in Italian.

But the pruning process itself has to be likewise regarded with a critical eye: Let us have a look at the single steps for the realization of Italian vai vs. andate. As you can see in Table 5, the form vai is easily derivable, since pruning allows the root to be adjacent to the φ-features (see the line highlighted in bold) and thus φ can condition the selection of va-. However, with andate, at a certain point, there is a theme vowel (highlighted in bold in the table), which disallows pruning. That is, the selection of the allomorphic root and- cannot be conditioned by φ. It is, indeed, the default (elsewhere condition). However, why is v°-Th realized by /a/ in one case and not in the other? When it comes to the realization of the theme vowel (cf. line (d) in Table 5), there are only two elements that can impinge on its realization: T° and √go. T° can be discarded immediately, since vai and andate have the same TAM-features. One could thus think that the phonological shape of the root triggers the respective realization of Th: Th is realized as Ø when preceded by /va/ and by /a/ when preceded by /and/. Yet, VI at √root is one of the latest steps (cf. line (j)) and is thus unable to influence the selection of the theme vowel.

Table 5.

Processes of pruning in single steps.

A solution to this dilemma is proposed by Calabrese (2019): He claims that suppletion, in the present tense, is not conditioned by the φ-features, but rather by the present-tense feature, and that the apparent φ-sensitivity is a “secondary” effect of an Impoverishment rule (cf. Halle 1997). To make his idea work, he introduces two kinds of pruning rules: a pruning rule that operates before VI (=Pre-VI-pruning) and another one which operates, as assumed by Embick (2010), after VI. The Pre-VI-pruning is not sensitive to the phonological null status of the pruned category, it is rather triggered by a diacritic [+suppletive] encoded in some special roots (e.g., √go[+suppl]). Pre-VI-pruning applies, for example, with vai, leading to a structure where v° and its Th-position are simply not present for VI. The nonappearance of the va-forms for the first- and second-person plural is due to an additional impoverishment rule: in these contexts, the diacritic [+suppletive] is deleted. As a consequence, Pre-VI-pruning cannot apply (Calabrese 2019). However, how the present-tense forms andiamo and andate are derived is not explained by him. Furthermore, there is no explanation for the observations that his special pruning is obviously restricted to the present tense. In addition, this approach is very technical, and one remains left with the impression that many assumptions are just restating the facts. In particular, the assumption of a diacritic and its deletion seem problematic to us. Another problem, among others, is that in the case of pruning nodes must be somehow “foreseen” by VI, since it is the realization of the root that tells us whether a verb is thematic (/and/) or athematic (/va/), but the realization of the root is conditioned by φ (which is preceded or not by a Th).

However, Calabrese (2015a, 2019) puts forward one innovative idea that we will follow in our analysis: there seems to be a link between athematicity and irregularity.

2.2.4. Spanning

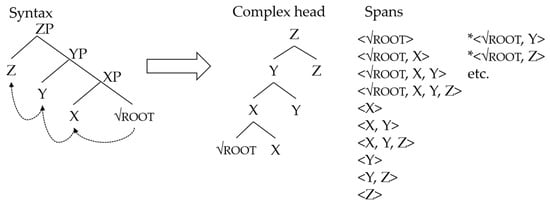

In the standard version of DM, VI operates from left to right, realizing step by step each single terminal node. Yet, it has been shown in the last years that many poststyntactic operations can be avoided if VI is not limited to terminal elements (cf. e.g., Haugen and Siddiqi 2016). Within the spanning approach, VI operates over the hierarchical structure allowing to insert phonological material not just in one terminal node at a time, but also in spans of terminal nodes that are in a complementary relation with each other (Williams 2003; Svenonius 2012; Merchant 2015; recently also Bonet 2017 for Spanish).10 Figure 8 illustrates this hypothesis: The nodes of the complex head may be realized separately or in spans. <√root,X,Y> as well as <√root,X,Y,Z>, etc., represent possible spans, but *<√root,Y> and *<√root,X,Z> do not.

Figure 8.

Spanning.

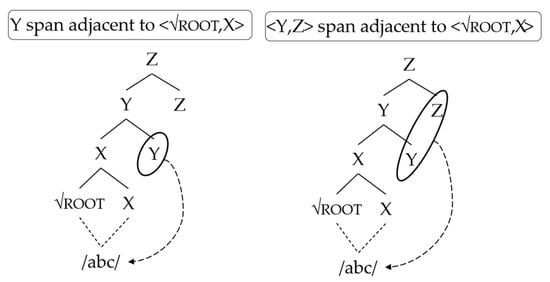

Now, with respect to the locality conditions on allomorphy, Merchant (2015) assumes that only span-adjacent elements can trigger allomorphy on each other (cf. (4)). In other words, nonadjacent nodes and their features cannot trigger allomorphy on each other unless the nonadjacent heads form a span that is adjacent to the node (or span) with the allomorphy-triggering condition.

- 4.

- Span-Adjacency Hypothesis: Allomorphy is conditioned only by an adjacent span. (Merchant 2015, p. 294)

Thus, given the derivation in Figure 9, Y can trigger allomorphy on the root if, e.g., <√root,X> is realized as a span, since in this case Y would be an adjacent span. Something similar holds for Z: Z could trigger root allomorphy if, e.g., <√root,X> and <Y,Z> were realized as span.

Figure 9.

Adjacency of spans.

We will apply the spanning approach to suppletion in the following Section 3 and we will identify different spans for VI for suppletive patterns of Romance √go, depending on language and syntactic context. Since the exact conditions and rules for spanning are still to be investigated, we hope to contribute to the issue by our analyses.

3. Results: Analysis and Outcome

In what follows, we will propose a spanning hypothesis for Spanish, Italian and French go-suppletion, which clearly shows the advantages of this approach from both a grammar-theoretical point of view as well as the perspective of cross-linguistic differences.

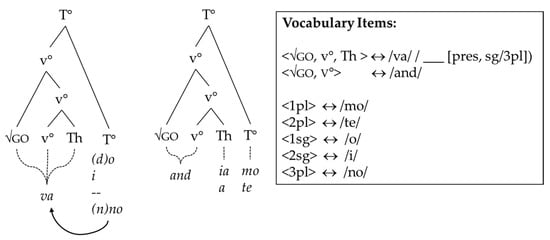

3.1. Synchronic Analysis: Spanish

As we saw in Section 2, Spanish only has categorial and no contextual suppletion, i.e., stem allomorphy is conditioned by categories inherent to the verb (and in the indefinido and related forms we find overlapping suppletion), cf. Table 6, where we find the segmented forms for go in the present tense and the imperfect.

Table 6.

Spanish: present tense and imperfect of go and some other verb forms.

In Table 6, the present tense form of the regular verb sing, cantar, can clearly be segmented into root, theme vowel and agreement features, i.e., √ + Th + φ; the imperfect form can be segmented in even more exponents, with the root, a theme vowel, an overt exponent for T° and a following theme vowel and the agreement features, i.e., √ + Th + T° + Th + φ. In contrast to Oltra-Massuet (1999), we will assume that T°-[present] is not subject to the well-formedness conditions that postsyntactically add positions on T° for the realization of the theme vowel and φ-features (cf. Figure 4, Section 2.2.2). The φ-features remain encoded under the T°-node and will be realized there if the language at issue has an appropriate vocabulary item for it. In contrast, in the imperfect form, T° receives a theme vowel position and a position for the realization of its φ-features.

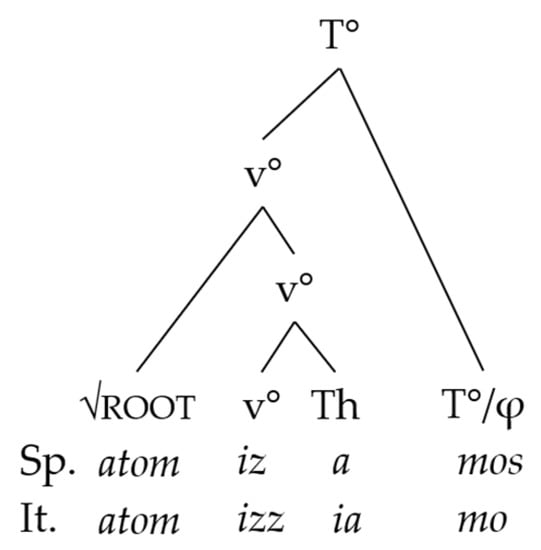

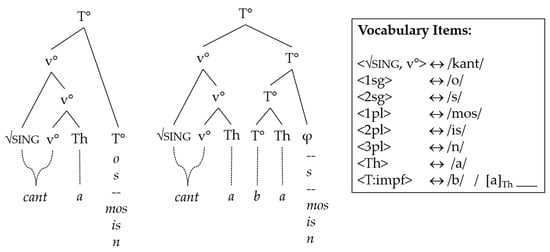

In case of a thematic verb such as cantar, we assume that the span size of the vocabulary item /kant-/ is <√sing, v°>; the following theme vowel position is realized instead by the default theme vowel /a/ (cf. Figure 10).11 The span size of the vocabulary item /kant-/ as well as the following realization of the theme vowel is dependent on the CC features of the root. /kant-/ is specified as belonging to the first CC, which is without any doubt thematic in Spanish.

Figure 10.

Spanning in the present tense and the imperfect of regular Spanish sing.12

Things are quite different for the Spanish verb ir: The above segmentations are not possible for go neither in the present tense nor in the imperfect; if we compare the present tense forms of go in Table 6 with those of the regular verb cantar, we observe two differences, namely first that also in Spanish—as in Italian—in the va- forms there is no theme vowel, i.e., √ + φ; and second, that the first-person singular is extended by the ending -y [j], parallel to other very common short verbal forms in the first-person singular, such as doy, soy and estoy, as well as maybe the existential hay.13 In the imperfect, the verbal form can be segmented into more exponents; however, again there is no theme vowel following the stem, i.e., √ + T° + Th + φ. We see, thus, that both roots are athematic, just like the Latin etyma were athematic (cf. vadere with epenthetic /e/ and īre). This fact is still reflected in the modern Spanish verb.

We will argue that the differences in the behavior of suppletive go and regular cantar are due to different sizes of “spanning” of the relevant vocabulary items: being athematic, the vocabulary item realizing the root va- has a larger spanning size (cf. Figure 11) than cant-, which is thematic, and whose span size is only <√, v°>. Again, the span size depends on the respective CC features; without going into details (cf. e.g., Pomino and Remberger, forthcoming, submitted, for a detail discussion), all athematic (or mixed) CCs have a larger spanning size than thematic verbs (e.g., cant-a-r, beb-e-r, part-i-r) and may show idiosyncratic irregularities. Consider Figure 11: in the present tense, <√go, v°, Th> forms a span that is realized by /ba/ (va-) since it is context-sensitive to the following present-tense feature. T° does not receive any exponent associated with tense, but its φ-features are realized (note that as in the regular forms in the present tense, there is no exponent for the third-person singular). In the other tenses (with the exception of the indefinido, which is a case apart; cf. Figure 12), T° has a proper exponent and a separate slot for the realization of the φ-features. The relevant point is, however, that in the imperfect, for example, the span <√go, v°, Th > receives a default realization, which is athematic /i/ in Spanish.

Figure 11.

Spanning in the present tense and in the imperfect of Spanish go14 (VIs are given in a simplified version).

With respect to the principles governing VI, we follow in essence the traditional proposal of Halle (1997, p. 428), cf. (5), with one addition proposed by Radkevich (2010, p. 8) necessary for integrating spans into the framework of DM), cf. (6): that is, a vocabulary item is inserted into the minimal node (=span) enclosing all the features of the vocabulary item. With this, it is guaranteed that the exponents do not realize a span too large or a too small.

- 5.

- The Subset Principle (Halle 1997, p. 428): The phonological exponent of a vocabulary item is inserted into a morpheme […] if the item matches all or a subset of the grammatical features specified in the terminal morpheme. Insertion does not take place if the vocabulary item contains features not present in the morpheme.

- 6.

- The Vocabulary Insertion Principle (Radkevich 2010, p. 8): The phonological exponent of a vocabulary item is inserted at the minimal node dominating all the features for which the exponent is specified.

We will illustrate this in what follows with the Spanish indefinido. As we have already mentioned, the morphosyntactic structure of these tense forms is less complex than in other tenses—not only for go but also for regular verbs; see Table 7:15

Table 7.

Spanish: The indefinido for go and regular verbs.

Both paradigms lack a separate exponent for T° and have a set of exponents for φ that is different from the present tense. We take this as an indicator that independent of the realization of the root and following elements, T°, Th and φ are realized as one span in the indefinido.16 This explains the exceptional shortness of these forms. Now, with respect to the VI, we assume the following: The vocabulary item /s/ for the second-person singular cannot be inserted in the indefinido, since there is a vocabulary item that is specified for more features, i.e., /ste/ for <T:indef, Th, 2sg>. This vocabulary item, however, cannot be inserted into the φ-slot (since it has features not encoded there), but it has to be inserted in those minimal nodes dominating all the features for which the vocabulary item is specified. Due to the tense feature included in its context of insertion, the vocabulary item /ste/ thus spans over T°, Th and φ. This is common to both verbs—regular/thematic cantar and irregular/athematic ir.

Yet, in the verbal forms of cantar there still is a preceding theme vowel in some of the forms, whereas for the go-forms, we again have an athematic root that spans over the theme position, as can be seen in Figure 12. Note that in this tense form, there are thus two adjacent spans, which trigger allomorphy on each other. This is, in contrast, not the case with thematic cantar since the theme vowels intervene.

To sum up, we have argued that Spanish has in essence two different verbs: thematic verbs (e.g., cantar = first conjugation, beber = second conjugation, partir = third conjugation) and athematic verbs (e.g., ir). This can be explained by assuming a fourth CC for athematic verbs. The main point is, however, that vocabulary items specified for belonging to one of the thematic conjugations have the span size <√go, v°>, whereas those specified for belonging to the athematic class have a larger span size which includes the theme vowel position, i.e., <√go, v°, Th>. With this, T° is an adjacent node and may trigger “root allomorphy” in the latter case, but not in the former one. Furthermore, also the verbal endings may exceptionally be realized as a span, as in the indefinido. This leads to shorter forms, which are, as general rule, also irregular.

The most important point is, however, that our analysis is predominantly based on the general process of VI to correctly derive the Spanish forms. We additionally need the well-formedness conditions, which add what are called ornamental morphemes (e.g., theme vowels) to the syntactic derivation, and regular phonological rules. We have thus shown in this section that integrating spanning into DM allows us to reduce the postsyntactic processes to a minimum. There is no need for fusion or different pruning rules (nor for impoverishment); root suppletion is instead explained in essence via VI. The spanning size of the vocabulary items realizing the roots is motivated by the (a)thematicity of the roots. In what follows, we will show that this approach is also valid for Italian and French, which, in contrast to Spanish, have noncategorial suppletion in the present tense.

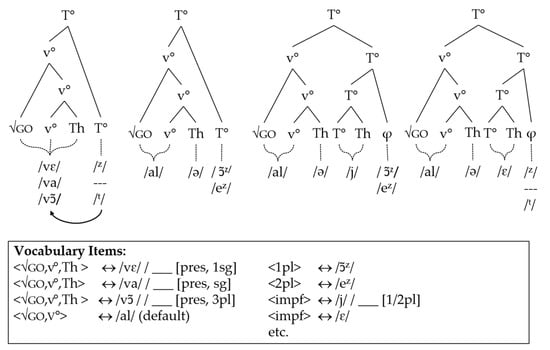

3.2. Synchronic Analysis: Italian

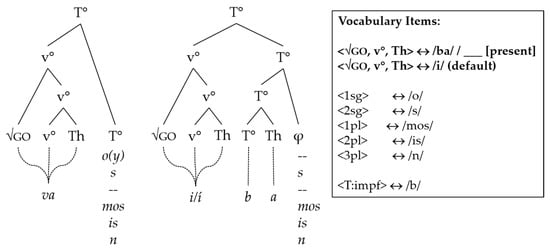

In Italian, suppletion only concerns the present tense, where it is context-sensitive. In all the other verbal categories the root /and-/ is generalized, i.e., it is the default realization for √go (cf. Table 8). Since andare is formally a first-conjugation verb, it is equipped with the theme vowel /a/ in all the cells of the paradigm where it appears, parallel to the regular verb cantare ‘to sing’.18 The only peculiarity, common to all Italian CCs, is that in the first-person plural, instead of /a/, the theme vowel is changed to /ia/ (which is a feature originally belonging to the subjunctive but then extended to the first-person plural in Florentine Tuscan) by a readjustment rule (cf. cant-ia-mo ‘we sing’, ved-ia-mo ‘we see’, fin-ia-mo ’we finish’). The suppletive forms we are interested in are the singular forms and the third-person plural in the present tense, a group of paradigmatic cells that—as mentioned before—do not belong to a natural class, whereas the first- and second-person plural would clearly represent such a natural class, characterized by the feature [+participant, plural]. Again, it is important to note that in contrast to and-, the va-based forms are athematic.

Table 8.

Italian: present tense and imperfect of go and regular sing.

That means that in Italian, there is a particular vocabulary item only for the singular forms and the third-person plural in the present tense for the root, whereas the case elsewhere is the insertion of the vocabulary item /and-/, which is a thematic root, i.e., with a span size limited to <√go, v°>. For the athematic va-forms, we assume in line with what has been said for Spanish that the “spanning” size of the relevant vocabulary items concerns <√go, v°, Th>, cf. Figure 13. As can be seen, T° (including its φ-features) is adjacent to the preceding span and may trigger allomorphy in case of the va-forms, but not in case of the and-form, since here there is an intervening theme vowel.

Figure 13.

Italian go in the present tense.

The problem now is how to circumvent the fact that [sg/3pl] is not a natural class, but rather a morphomic pattern (the N-pattern) as identified by Maiden in his work (e.g., Maiden 2004, 2009, 2018).19 We would like to go back to a solution proposed by Trommer (2016) in his “postsyntactic morpheme cookbook”: he proposes that in order to explain morphomic patterns in inflection, there are “hidden parasitic features”, or “meta-features on markedness”. These features have a metalinguistic value, but are indeed observable to have their relevance in the derivation of morphomic rules. What is needed according to Trommer (2016), is a redundancy rule that makes a metafeature [m] visible to VI. In the case of Italian go-suppletion in the present tense, this redundancy rule would look like this:

- 7.

- Redundancy Rule:20[ ] → [m]/[+sg][ ] → [m]/[+3]

We can than reformulate the rule for the insertion of the vocabulary item /va/ in Italian as follows:

- 8.

- Vocabulary Item va:<√go, v°, Th> ↔ /va//___ [pres, m]

The last two issues that need to be explained are the forms vado in the first-person singular and vanno in the third-person plural. We assume that the insertion of epenthetic /d/ in the outcome /vao/ is just another strategy to avoid the hiatus. Indeed, in colloquial Italian (and Italian from Tuscany), there is the supplementary and regular form vo (cf. Markun 1932, pp. 282, 299; Rohlfs 1949, p. 278), where the strategy to avoid the hiatus is simply monophthongization. As for the geminate /nn/ in vanno, we would like to propose that this is also a readjusted form since tonic syllables have to be bimoraic in Italian, i.e., either the vowel of the tonic syllable is lengthened or the syllable is closed by gemination; since the vocabulary entry in this case contains a short vowel, which somehow seems to resist lengthening, the other strategy, namely gemination, is chosen.

We have shown that the derivation of Italian and Spanish go forms is quite similar in the sense that athematic and thematic VI have the same span sizes in both languages. The main difference relies in the fact that Italian mixes athematic and thematic verbs in the present tense, whereas Spanish does not.

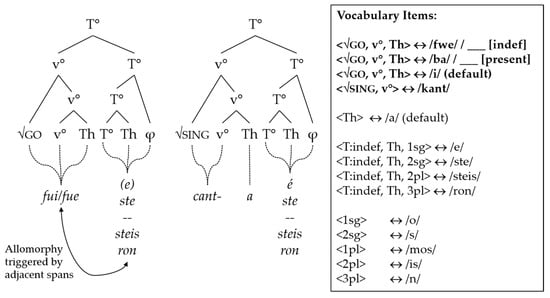

3.3. Synchronic Analysis: French

Even though French differs in its morphology in many respects from Spanish and Italian, we assume essentially the same analysis for French go suppletion. As can be depicted from Table 9, the inflectional patterns in French clearly show a reduced segmentability, not only for go, but also for regular sing. Note that only the first- and second-person plural still have exponents for φ-features that are not dependent on liaison.21 The exponents for the other persons are, as general rule, /z/ and /t/, which are latent consonants, i.e., their realization depends on a following vocalic onset (otherwise they do not surface).

Table 9.

French: several forms of go and sing.

In contrast to Spanish and Italian, the orthographic form of French verbs and their pronunciation differ greatly. In addition, as just mentioned, not all exponents surface in all contexts. This means that the segmentation of the orthographic form may give a wrong impression with respect to the phonological shape of the French verbs. In what follows, we will indicate the French verbs in their phonic form where superscript elements stand for latent consonants that may not surface. This is especially the case for the TAM and the agreement morphemes.

Thus, compared to Spanish and Italian, French verbs, including the regular ones, are structurally less “transparent”. It is not only the apparent loss of theme vowels, but also the verbal endings that are subject to a sandhi phenomenon such as liaison that makes French look different form other Romance languages, at least superficially. As said before, the first- and second-person plural still have exponents for φ-features that are “hearable” independently from liaison, CC, etc., but all other person–number endings are, in contrast, highly instable in the sense that they surface only in certain strongly restricted contexts. The illustration in Table 10 is based on Schpak-Dolt (1992, pp. 115–16); we have highlighted the forms that surface independently of the phenomenon of liaison. As you can see, person is realized in all tenses only in the first- and second-personplural. What is more, in spoken colloquial French, the first-person plural often is expressed by the impersonal form on chante [ʃãt], on va [va], etc. That means that the only remaining vocabulary item for φ-features in this case is the second-person plural.

Table 10.

French person–number endings (orthographic and phonic forms).

In order to keep the focus on the main aim of our paper, we will not enter into all details of French verbal inflection here, and will limit ourselves to the forms of the present tense and the imperfect (but see Pomino and Remberger, forthcoming, submitted). For these two tenses the French verbs aller and aimer can be segmented as given in Table 11. The present tense forms have, at first glance, only two components or even only one, whereas the imperfect forms allow a threefold decomposition. When compared to Spanish and Italian it seems thus as if French verbs were always athematic. In none of the given French forms can we find the overt realization of a theme vowel (cf. e.g., Fr. [al-j-ɔ͂z] allions vs. It. and-a-v-a-mo).

Table 11.

Selected (liaison) forms of French aller and aimer (provisional).

There are, however, good reasons to assume that French also still has theme vowels. In Pomino and Remberger (forthcoming, submitted), we assume that French has athematic verbs, but also thematic verbs: verbs of the first and second CC (e.g., aimer and finir) are thematic. Evidence for the postulation of theme vowels in French for the first CC come, for example, from the consonant–zero alternation (cf. Schane 1966): The root final consonant of athematic viv(re) ‘to live’ (third CC) is maintained if there is a possibility for it to appear in a syllable onset, e.g., before V (e.g., nous vivons [vi.vɔ͂] ‘we live’) or a C with which it can build a complex onset (e.g., nous vivrons [vi.vʁɔ͂] ‘we will live’), but is deleted before a following consonant with which it cannot form an onset (tu vis [vi-(z)] ‘yousg live’ not *tu vivs [viv-(z)]). The same final consonant of thematic arriv(er) (first CC) is, in contrast, never deleted: tu arrives [aʁiv-(z)] ‘yousg arrive’ not *tu arris [aʁi-(z)]. Schane (1966) and others assume that in this case the theme vowel [ǝ], which does not surface, blocks consonant deletion (cf./aʁiv+(ǝ)+(z)/).22 The assumption of theme vowels for the second CC (e.g., finir) is straightforward, since here the theme vowel surfaces as either [i] or [is] (cf. e.g., second-person singular [fi.ni] finis and second-person plural [fi.ni.se] finissez).23

If this is correct, the liaison forms of the French verbs aller and aimer are the ones given in Table 12: We assume that aller as well as aimer (but not the va-forms) have a theme vowel /ə/, which does, as general rule, not surface, but it blocks consonant deletion of the root final consonant.

Table 12.

Selected (liaison) forms of French aller and aimer.

With the sole exception that there is maybe no or not enough evidence for assuming a theme vowel position for T° in French,24 the verbal structure and the analysis of go-suppletion is in essence parallel to Spanish and Italian, cf. Figure 14.

Figure 14.

French go in the present tense and in the imperfect.

By assuming theme vowels for French, too, we can better understand the conditions on go-suppletion. Being thematic, the span size of the default realization of French go is <√go, v°>. In contrast, the span size of the va-forms is larger, i.e., it is <√go, v°, Th>, and the allomorphy (cf. /vɛ/, /va/ and /vɔ͂/) is conditioned by the span-adjacent features of T° (which in the present tense contains φ).

4. Discussion: The Advantages of a Spanning Approach

In Section 2, we have shown that some of the postsyntactic processes assumed in DM are disputable as far as our Romance data concern. Fusion, as well as the pruning approaches, face several shortcomings that can be solved when we admit that VI is not restricted to terminal nodes, but is allowed to be inserted in spans. In Romance, in the present tense, fusion seems to be strongly redundant, since it simply reverses the result of posited well-formedness conditions. It is thus better to assume that the respective conditions just do not apply. What is more, fusion does not alter the locality between the root and φ in a way it would be necessary to trigger allomorphy. The pruning approach, in contrast, faces a look-ahead problem: the realization of the theme vowel depends on the realization of the root, but the realization of the root can be determined only after the theme vowel is realized or pruned. Furthermore, in a pre-VI-pruning approach such as the one proposed by Calabrese (2015a), an additional impoverishment rule is necessary in order to delete the diacritic [+suppletive], to avoid a va-form being inserted in the first- and second-person plural in Italian. In sum, both approaches assume additional postsyntactic processes (fusion, pruning, impoverishment) which, in our opinion, cannot even correctly derive the respective forms.

In our analyses in Section 3, we proposed that spanning is the solution to contextual conditioned allomorphy. This approach centers predominantly on the general and well-established process of VI and correctly derives Romance verbal forms. Of course, we still additionally need the uncontroversial well-formedness conditions, which add what are called ornamental morphemes (theme vowels and φ-positions) to the syntactic derivation in other tenses than the present tense, as well as regular phonological-readjustment rules. We have thus shown that integrating spanning into DM allows us to reduce the postsyntactic processes to a minimum. There is no need for fusion or different pruning rules, and root suppletion is instead explained in essence via VI.

For the three Romance languages analyzed here, we have illustrated that the span size of the respective vocabulary items stands in direct relation to the CC they belong to. The CC may be thematic or athematic, and athematicity implies, in our analysis, a larger span size. What is more, allomorphy is restricted to adjacent spans, and thus, in those cases where T° and/or φ trigger allomorphy, the respective verbs must be athematic.

Besides this, the framework of DM with an integrated spanning approach allows us to grasp and model cross-differences on a theoretical level. To illustrate this, we will resume some generalizations that our analyses brought forward:

We have seen that there are some essential differences in the input and outcome of VI as far as tenses are concerned: The present tense is obviously a verb form where T° has no theme vowel nor a separate φ-position, allowing therefore contextually conditioned (noncategorial) allomorphy in all three languages studied here. The imperfect, at least in Spanish and French, is the tense form where we find a maximum of form–function correspondence, including theme vowels for the vocabulary items for functional categories v° and T°. Only v° is not realized except in derivatives, yet it is syntactically (and semantically) present, and visibly followed by a theme vowel. Only the root and little v° therefore are realized by a vocabulary item that builds a span. The presence of the theme vowel prevents stem allomorphy. In French, the presence of theme vowels is less obvious even in the imperfect. It is highly probable that, in French, the well-formedness condition for the insertion of theme vowels holds only for little v°, and there only for certain thematic verbs whose main characteristic is that their stem final consonant is maintained. The tenses derived from the old perfect forms, i.e., the Spanish indefinido or the Italian passato remoto again are structurally less complex, similar to the present tense. However, contrary to the verbal forms in the present tense, we assume that in this tense we have both the realization of T° and its theme vowel in form of a span that includes also φ (an assumption that is also historically justified). This “inflectional” stem then can trigger stem allomorphy, provided that there is no theme vowel, as it is the featural content of T°-[indefinido] to condition the realization of the particular inflectional endings of the indefinido.

Author Contributions

N.P. and E.-M.R. equally contributed to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing (original draft preparation as well as review and editing), and visualization of this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the audiences of the CRAFF-workshop “Connecting roots and affixes”, 13–14 May 2019, Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University, Brno; of the GGS, Frankfurt am Main, 19–21 July 2019; of the Workshop “Distributed Morphology from Latin to Romance”, 30–31 October 2019, Department of Romance Philology, University of Vienna; of the BCGL 12, Brussels, 16–17 December 2019; of the Workshop “Constraining Allomorphy” at the OLINCO, Olomouc/Czech Republic, 10 June 2021; and of the Coloquio de Gramática Generativa #30, UA Barcelona, 30 June–2 July 2021, for their valuable questions and discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Although the notion paradigm is rejected in the framework of DM (cf. e.g., Bobaljik 2002), we will continue to use it as an auxiliary concept in this paper. |

| 2 | See Leumann et al. ([1965] 1972, 757 s) for the early intrusion of these verbs; also Gartner (1883, pp. 158–160); Menéndez Pidal (1925, p. 265); Rohlfs (1949, pp. 278–82); Tekavćič (1972, pp. 351–52); Alvar and Pottier (1983, pp. 228–29); Lathrop (1989, pp. 171, 175, 177, 191); Lloyd (1987, pp. 297, 298); Penny (2000, pp. 192–93); Juge (2000, p. 190) and Julia (2016, pp. 56–191). |

| 3 | Our data stem from various grammars and descriptions of the verbal system of Romance varieties, e.g., Bernardi et al. (1994); DéRom (Buchi and Schweickard 2008); Decurtins (1958); Lapesa (1980); Lathrop (1980) and Benincà et al. (2016), besides the references mentioned in the previous footnote. For a comprehensive discussion of go-forms in Romance, cf. Maiden (2018). We have included Lombard, Old Tuscan and Engadinish in Table 2 to illustrate that there are different noncategorial patterns in the present tense. |

| 4 | There is one exception to this: the Spanish imperative is ¡ve! for the second-person singular, but ¡id! in the second-person plural. |

| 5 | Since in what follows we concentrate on French, Italian and Spanish, we will not try to indicate the distribution of the suppletive patterns for Lombard, Old Tuscan and Engadinish, mainly also because there is a lot of variation in these non-standard systems and often more than one verb form (e.g., vādere and īre, andāre and vādere) are allowed in the paradigmatic cells. As mentioned before, we have included these varieties to show that there are different noncategorial patterns in the present tense. |

| 6 | In traditional works, the imperfect forms are segmented into √-Th-TAM-φ, e.g., Sp. cant-á-ba-mos ‘we sang’). Oltra-Massuet (1999) shows that whenever TAM is realized it contains (or is) a vowel that is identical to one of the theme vowels in the respective language. Thus, she proposes to further segment -ba- (and other TAM-suffixes) into TAM and Th, i.e., cant-á-b-a-mos. The theme vowel of T° does however not depend on a CC feature, but on the vocabulary item for T° itself, and it does not surfaces in all tenses, cf. e.g., the present tense cant-a-mos ‘we sing’. We will not enter into further discussion relative to this topic, since the assumption of a theme vowel for T° does not impinge on our analysis. For a comprehensive analysis of the Spanish verb forms in DM, cf. also Pomino (2008). |

| 7 | The question whether French has theme vowels or not is discussed in Pomino and Remberger (forthcoming, submitted) and cannot be repeated here for the interest of space. We propose, in essence, that French first and secondCC classes are thematic (e.g., aimer and finir), whereas all other CCs are athematic (or belong to a mixed system, in the case of aller ‘to go’). |

| 8 | Just like singular can be interpreted as the absence of an explicit plural marker in Romance, present tense results from the nonexplicit marking of T°. |

| 9 | In an earlier paper, we still followed this line of reasoning (cf. Pomino and Remberger 2019). |

| 10 | Contrary to the mapping of morphophonological material on nonterminal nodes in the shape of complex syntactic structures proposed by nanosyntax (e.g., Caha et al. 2019), the spanning approach has the advantage of keeping syntactic structures minimal and independent of the intricate variational patterns found in morphophonological realizations. Nevertheless, some of the ideas of Nanosyntax, e.g., insertion of regular and irregular lexical items into differently sized structures, seem to somehow mirror a spanning approach—although the other way round, irregular forms such as French [saʃ] (subjunctive from savoir ‘to know’) lexically realize less structure in Starke (2020) than regular forms such as French [sav]. |

| 11 | The selection of the right theme vowel is usually modeled by a diacritic, cf. Oltra-Massuet (1999). These diacritics should be privative features, and since the first CC is the default, it is just not marked by a diacritic. |

| 12 | Note that we have fully specified the φ-features in the Figures, although the vocabulary items could essentially be simplified because of the principle of underspecification. For reasons of easier comprehensibility, we do not give the vocabulary items for the realization of the agreement features in their underspecified form (e.g., [1pl] and [1sg] vs. [1pl] and [1]) (cf. e.g., Embick 2015, pp. 26–27 for Spanish). |

| 13 | The 1sg (voy not *vao/*vaoy) is special in the sense that /a/ is not realized in order to avoid the hiatus /ao/. What is more, voy does not end in -o but it ends in -y, as other very frequent short verbs in modern Spanish (see doy, soy, voy and estoy). According to Lathrop (1989, p. 170) and others, the diachronic development of these forms can be seen as a merger of two vocabulary items (i.e., /o/ as exponent of T°/φ and /j/ as exponent for the locative clitic which goes back to the Latin ibi, see also the existential hay lit. ‘there has’) that often came to be adjacent, especially since one of them is a clitic. However, there are other explanations for /j/ brought forward in the literature, which argue, based on historical data, against an interpretation of /j/ as the long vanished locative clitic (for an overview, cf. Diaz 2016). |

| 14 | Note that, in Spanish, the exponent /b/ for the imperfect tense appears, as general rule, only in the first conjugation, i.e., after a theme vowel a (which again is either selected by a diacritic or represents the default): cantábamos, but bebíamos, mentíamos and not *bebíbamos, *mentíbamos. We leave it open, for the moment, why /b/ is inserted here (but see Fábregas 2007); note that this /b/ was already present in the Latin forms of go. |

| 15 | The indefinido has a bunch of pecularities: The shortness of the forms has to do, for example, with the loss of the Latin perfect marker -v-. This perfect marker was, at first, not realized in Latin inbetween identical vowels (e.g., audīvi > audīi). Afterwards it was also supressed in other intervocalic positions (e.g., audīveram > audīeram and cantāvī > cantāī) (cf. García-Macho and Penny 2001, p. 32; Alvar and Pottier 1983, p. 272). This had a snowball effect, since due to the regular phonological change the diphthong /ai/ was monophthongized to /e/, whereas according to Alvar and Pottier (1983, p. 273), the ending for the third-person singular was -avit > -aut > -ó(t), where the diphthong /au/ was reduced to /o/. Other peculiarities, e.g., the ending -ste for the first-person singular, were already part of the Latin system. |

| 16 | But, contrary to the present tense, the indefinido is a specific tense proper, i.e., its T°-node is equipped both by a theme vowel and a φ-position, due to the well-formedness condition illustrated in Figure 4. Note, furthermore, that it would also be possible (and diachronically plausible) to assume that the vocabulary item for the root is in all cases /fu-/ which spans over <√, v°, Th> and the following vowel is the span-realization of T° and its ThV, e.g. fu-i-mos (cf. Remberger and Pomino 2022). |

| 17 | As observed in Section 2.1, in the indefinido (and related categories) the stem allomorph for go overlaps with that of be. The φ-features in the context of T°:indef differ from the present tense forms in the first- and second-person singular and in the second- and third-person plural. Furthermore, we have one root allomorph in the third-person singular and plural, namely /fwe/, and a slightly different root allomorph in the other persons, namely /fwi/ (which phonologically merges with the vocabulary item of the first-person singular /’e/ giving result to fui). Also in the case of cantar, the respective forms may additionally be affected by phonological rules, e.g., the reductoin of the hiatus in /kan.ta.’e/ > [kan.’te]. |

| 18 | In the first-person singular the theme vowel /a/ is not realized in order to avoid the hiatus /ao/, */kanta-o/; the same holds for the second-person singular, where we have canti instead of */kantai/. One of the anonymous reviewers mentions that if we would accept /vad/ instead of /va/ as the spanning vocabulary item for go, the form vanno could be explained by phonological assimilation of /vad-no/ to /vanno/. However, we decided for /va/, and in this case, vanno must be explained by a well-formedness condition on stressed syllable structure (cf. Pomino and Remberger 2019). |

| 19 | The notion morphome goes back to Aronoff (1994). |

| 20 | We agree with one of the anonymous reviewers who critized the assumption of this redundancy rule as restatement of the facts. The reviewer further suggested an alternative analysis based on the idea that in the first- and second-person plural the verbal endings span over <Th, T°>, i.e., /iamo/ ⟷ <Th, T°-[1pl]> and /ate/ ⟷ <Th, T°-[2pl]>. This proposal, as pointed out by the reviewer, has several advantages, e.g., one could argue that first-and second-person plural endings cannot combine with athematic roots, since they have their own Th; in addition, the fact that these elements consistently bear stress could be attributed to this analysis. Indeed, in preliminary works to this publication we thought about a similar solution, but we rejected it since v° is a phase head and the span size <Th, T°> (note that Th is adjoined to v°) would ignore this. In sum, it is not yet sufficiently clear to us how phase heads may affect the spanning size of vocabulary items. |

| 21 | In the phonic (=spoken, as opposed to the graphic/written modality) realization of French, the phenomenon of liaison is one of the most striking sandhi phenomena of this language. Liaison is understood as the overt realization of a latent word-final consonant which (in a specific syntactic/prosodic context) is not pronounced before a following word-initial consonant (e.g., mes frères [me fʀɛʀ] ‘my brothers’), but is realized in front of a following word-initial vowel (e.g., mes amis [mez ami] ‘my friends’). |

| 22 | There are alternative analyses for this kind of allomorphy. We cannot discuss further details of these approaches here for the interest of space (cf., however, Pomino and Remberger, forthcoming, submitted). |

| 23 | Again, not all linguists assume theme vowels for the second conjugation (e.g., El Fenne 1994; Bonami and Boyé 2002; Bonami et al. 2008). |

| 24 | We assume here that T°-[imperfect] and its theme vowel position are realized as a span, but it is very likely that in French, the theme vowel position is not added by a well-formedness condition at all. |

References

- Alvar, Manuel, and Bernard Pottier. 1983. Morfología Histórica del Español. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff, Mark. 1994. Morphology by Itself. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arregi, Karlos. 2000. How the Spanish Verb Works. Paper Presented at the LSRL 30, Gainesville/Florida. Available online: http://home.uchicago.edu/~karlos/Arregi-theme.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Benincà, Paola, Mair Parry, and Diego Pescarini. 2016. The dialects of Northern Italy. In The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages. Edited by Adam Ledgeway and Martin Maiden. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste, Émile. 1968. Mutations of linguistic categories. In Directions for Historical Linguistics: A Symposium. Edited by Winfred Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. Austin: University of Texas, pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, Rut, Alexi Decurtins, Wolfgang Eichenhofer, Ursina Saluz, and Moritz Vögeli. 1994. Handwörterbuch des Rätoromanischen: Wortschatz aller Schriftsprachen, einschliesslich Rumantsch Grischun, mit Angaben zur Verbreitung und Herkunft. 3 vols. Zürich: Offizin. [Google Scholar]

- Bobaljik, Jonathan D. 2000. The ins and outs of contextual allomorphy. Linguistics 10: 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bobaljik, Jonathan D. 2002. Syncretism without paradigms: Remarks on Williams 1981, 1994. In Yearbook of Morphology 2001. Edited by Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 53–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bobaljik, Jonathan D. 2012. Universals in Comparative Morphology. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bobaljik, Jonathan D. 2017. Distributed Morphology. ORE—Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Available online: http://linguistics.oxfordre.com/ (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Bobaljik, Jonathan, and Heidi Harley. 2017. Suppletion is local: Evidence from Hiaki. In The Structure of Words at the Interfaces. Edited by Heather Newell, Maíre Noonan, Glynne Piggot and Lisa Travis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonami, Olivier, and Gilles Boyé. 2002. Suppletion and Stem Dependency in Inflectional Morphology. Paper presented at the HPSG ‘01 Conference, Toulouse, France, July 6–11; Edited by Franck Van Eynde, Lars Hellan and Dorothee Beerman. Stanford: CSLI Publications, pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bonami, Olivier, Gilles Boyé, Hélène Giraudo, and Madeleine Voga. 2008. Quels verbes sont réguliers en français? In Congrès Mondial de Linguistique Française 2008. Edited by Durand Jacques, Benoît Habert and Bernard Laks. Paris: Institut de Linguistique Française. Available online: https://www.linguistiquefrancaise.org/articles/cmlf/pdf/2008/01/cmlf08186.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Bonet, Eulalia. 1991. Morphology after Syntax: Pronominal Clitics in Romance. Cambridge: MIT. [Google Scholar]

- Bonet, Eulalia. 2017. Inserción de terminales versus inserción de conjuntos de terminales. In Relaciones sintácticas. Edited by Angel Gallego, Yolanda Rodríguez and Javier Fernández-Sánchez. Bellaterra: Servei de Publicacions UAB. [Google Scholar]

- Buchi, Éva, and Wolfgang Schweickard. 2008. Dictionnaire Étymologique Roman. Available online: http://www.atilf.fr/DERom/ (accessed on 12 December 2018).

- Caha, Pavel, Karen De Clercq, and Guido Vanden Wyngaerd. 2019. The Fine Structure of the Comparative. Studia Linguistica 73: 470–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, Andrea. 2015a. Irregular Morphology and Athematic verbs in Italo-Romance. Isogloss. Open Journal of Romance Linguistics, 69–102. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/isogloss/article/view/304706 (accessed on 13 June 2022). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Calabrese, Andrea. 2015b. Locality effects in Italian verbal morphology. In Structures, Strategies and Beyond. Studies in Honour of Adriana Belletti. Edited by Elisa Di Domenico, Cornelia Hamann and Simona Matteini. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins, pp. 97–132. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, Andrea. 2019. Morphological Investigations: A Theory of PF. From Syntax to Phonology in Italian and Sanskrit Verb Forms, Unpublished manuscript.

- Decurtins, Alexi. 1958. Zur Morphologie der unregelmäßigen Verben im Bündnerromanischen. Bern: Francke. [Google Scholar]

- Detges, Ulrich. 2004. How cognitive is grammaticalization? The history of the Catalan perfet perifràstic. In Up and Down the Cline. The Nature of Grammaticalization. Edited by Olga Fischer, Muriel Norde and Harry Perridon. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 211–27. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, Miriam. 2016. Semantic changes of ser, estar, and haber in Spanish: A diachronic and comparative approach. In Diachronic Applications in Hispanic Linguistics. Edited by Eva Núñez Méndez. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, pp. 303–44. [Google Scholar]

- El Fenne, Fatimazohra. 1994. La flexion verbale en français: Contraintes et stratégies de réparation dans le traitement des consonnes latentes. Ph.D. dissertation, Université Laval, Quebec City, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Embick, David, and Moritz Halle. 2005. On the status of stems in morphological theory. Paper presented at the Going Romance 2003, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, December 6–8; Edited by Twan Geerts and Haike Jacobs. Available online: http://www.ling.upenn.edu/~embick/stem.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2009).

- Embick, David. 2010. Localism versus Globalism in Morphology and Phonology. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Embick, David. 2014. Phase cycles, φ-cycles, and phonological (in)activity. In The Form of Structure, the Structure of Form: Essays in Honor of Jean Lowenstamm. Edited by Sabrina Bendjaballah, Noam Faust, Mohamed Lahrouchi and Nicola Lampitelli. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 271–86. [Google Scholar]

- Embick, David. 2015. The Morpheme. A Theoretical Introduction. Boston and Berlin: De Guyter/Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Fábregas, Antonio. 2007. Ordered Separationism: The Morphophonology of ir. In Selected Proceedings of the 5th Décembrettes: Morphology in Toulouse. Edited by Fabio Montermini, Gilles Boyé and Nabil Hathout. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- García-Macho, María Lourdes, and Ralph Penny. 2001. Gramática Histórica de la Lengua Española: Morfología. Madrid: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, Theodor. 1883. Raetoromanische Grammatik. Heilbronn: Henninger. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Torrego, Leonardo. 1999. Los verbos auxiliares. Las perífrasis verbales de infinitivo. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa, pp. 3323–89. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed Morphology and the Pieces of Inflection. In The View from Building 20. Edited by Ken Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 111–76. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, Morris. 1997. Distributed Morphology: Impoverishment and Fission. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 30: 425–49. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, Jason D., and Daniel Siddiqi. 2013. Roots and the derivation. Linguistic Inquiry 44: 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, Jason D., and Daniel Siddiqi. 2016. Towards a Restricted Realization Theory. Multimorphemic monolistemicity, portmanteaux, and post-linearization spanning. In Morphological Metatheory. Edited by Daniel Siddiqi and Heidi Harley. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins, pp. 343–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hippisley, Andrew, Marina Chumakina, Greville G. Corbett, and Dunstan Brown. 2004. Suppletion. Frequency, categories and distribution of stems. Studies in Language 28: 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingason, Anton Karl, and Einar Freyr Sigurðsson. 2015. Phase locality in Distributed Morphology and two types of Icelandic agent nominals. In NELS 45: Proceedings of the 45th Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, Volume II. Edited by Thuy Bui and Deniz Özyıldız. Amherst: Department of Linguistics, University of Massachusetts, pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Juge, Matthew L. 2000. On the Rise of Suppletion in Verbal Paradigms. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. Edited by Jeff Good and Alan C. L. Yu. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society, pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, Marie-Ange. 2016. Genèse du Supplétisme Verbal: Du Latin aux Langues Romanes. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Lapesa, Rafael. 1980. Historia de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop, Thomas A. 1980. The Evolution of Spanish. Newark: Juan de la Cuesta. [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop, Thomas A. 1989. Curso de Gramática Histórica Española. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Leumann, Manu, Johann Baptist Hofmann, and Anton Szantyr. 1972. Lateinische Grammatik. Zweiter Band. Syntax und Stilistik, 2nd ed. München: C.H. Beck’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. First published 1965. [Google Scholar]