Optionality in the Expression of Indefiniteness: A Pilot Study on Piacentine

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Variation and Optionality in Syntax

1.2. The Expression of Indefiniteness

| (1) | a. | Mary visited a garden, some garden(s), some of the gardens, a certain garden. |

| b. | Maurice visited the/this garden, these gardens/the capital of Albania/the largest museum in the world. (Brasoveanu and Farkas 2016, p. 238) |

- (2)

- Muriel visited gardens when she traveled to France this summer. (Brasoveanu and Farkas 2016, p. 239)

1.3. Variation in the Italian and Italo-Romance Determiner System

- The zero determiner introducing bare nominals, henceforth labeled “ZERO” (cf. (3a)).3

- The definite article with indefinite interpretation, henceforth “ART” (cf. (3b)).

- The simple di determiner, homophonous to the genitive preposition, referred to as “bare di”, common in certain north-western Italo-Romance varieties (cf. (3c)) and only appearing on dislocated indefinites in standard Italian (cf. (3c’)).

- The partitive determiner, which displays a superficial syncretism with the articulated preposition introducing partitive constructions. This determiner combines di with the morphology of the definite article. It will be labeled “di+art” (cf. (3d)).

- The determiner-like certo “certain”, which is used as an indefinite determiner only in some southern varieties (Rohlfs 1968, p. 119) (cf. (3e)). In standard Italian, it only conveys a specific reference (cf. (3e’)).

| (3) | a. | Mangio | Ø | biscotti | |

| I-eat | ZERO | biscuits | |||

| b. | Mangio | i | biscuits | ||

| I-eat | ART | biscuits | |||

| “I eat biscuits.” | |||||

| c. | sei | fyse | d’ | aqua | |

| if-there | was | di | water | ||

| “If there was water.” | (Piedmontese; Berruto 1974, p. 57) | ||||

| c’ | Di | biscotti, | ne | mangio | |

| di | biscuits | NE | I-eat | ||

| “Of biscuits, I eat.” | |||||

| d. | Mangio | dei | biscotti. | ||

| I-eat | di+art | biscuits | |||

| “I eat some biscuits.” | |||||

| e. | cǝ | šta | cirta | pǝrzonǝ | |

| there | is | certo | people | ||

| “There are some people.” | (Abruzzese; Rohlfs 1968, p. 119) | ||||

| e’. | Mangio | solo | certi | biscotti | |

| I-eat | only | certo | biscuits | ||

| “I only eat certain (kinds of) biscuits.” | |||||

1.4. True Optionality in Italian?

- Noun class: mass nouns vs. plural count nouns.

- Polarity: negative vs. positive sentences.

- Sentential aspect: telic vs. atelic sentences.

- Sentence type: episodic vs. generic.

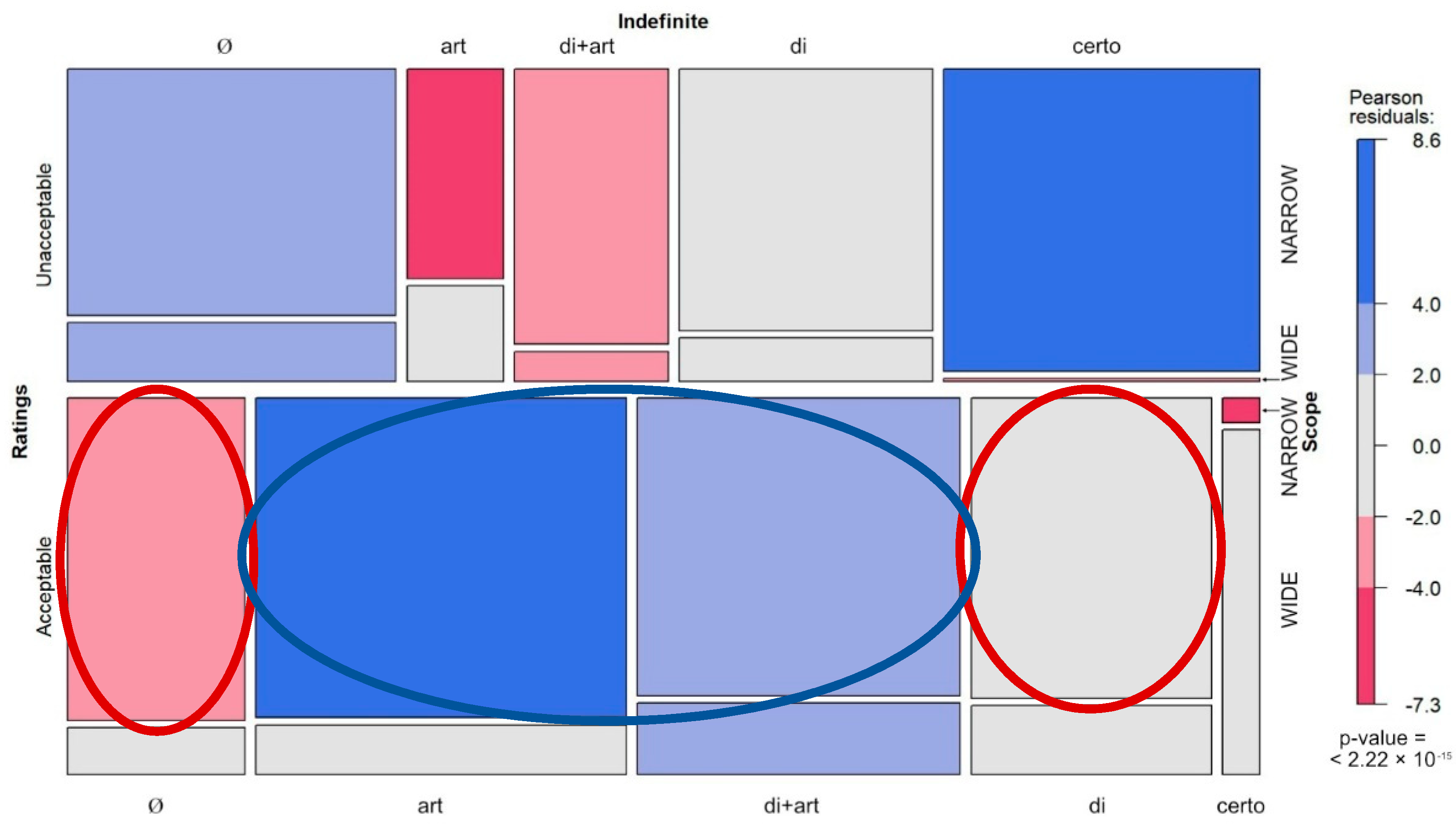

- Scope of the indefinite: wide vs. narrow.

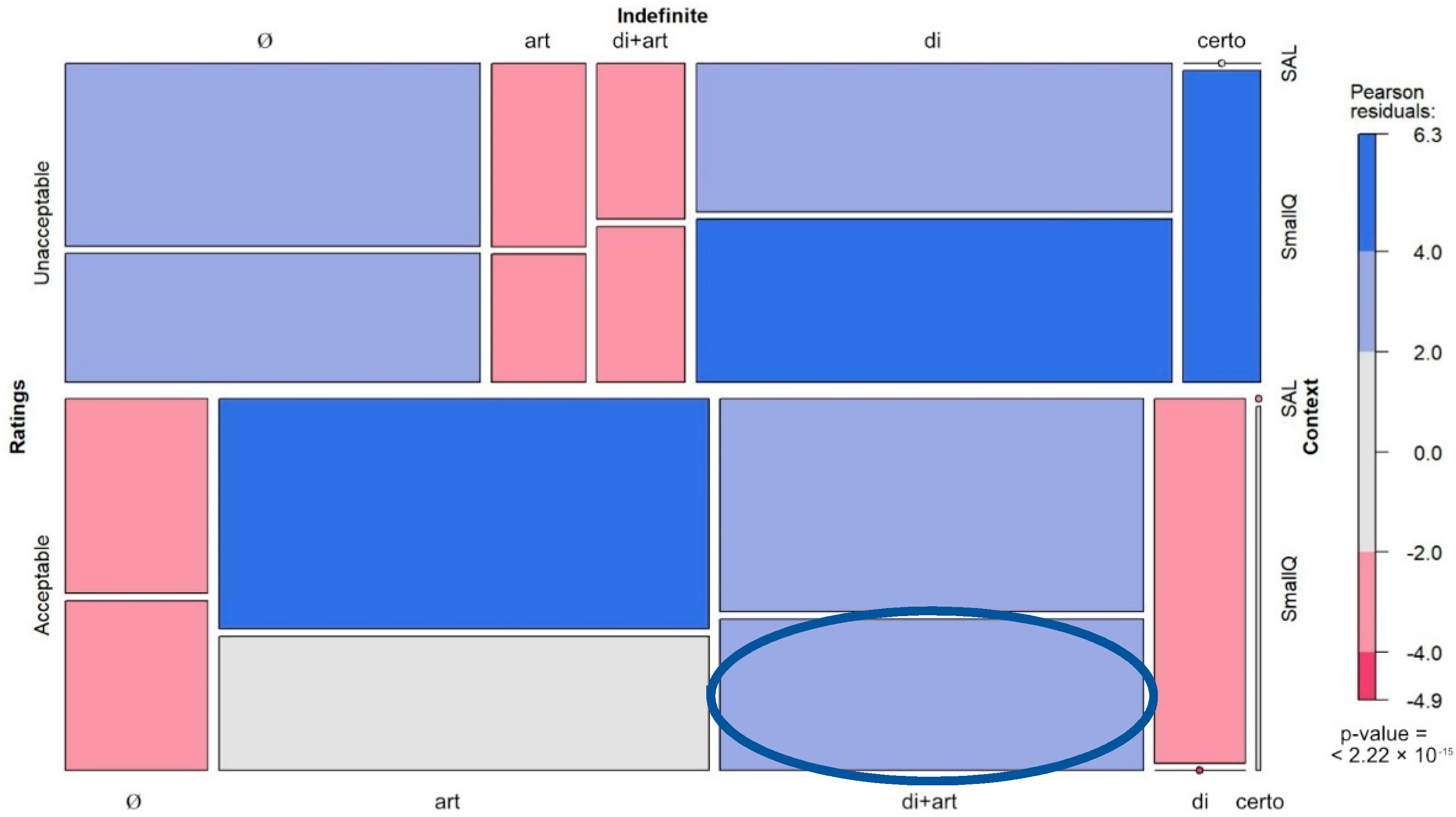

- Meaning specialization: saliency vs. small quantity.

1.5. Aim and Research Questions

- (4)

- Research questions for the study on Piacentine:

- How many and which indefinite determiners are available in Piacentine?

- If more than one indefinite determiner is available (as expected), is there optionality in the choice of competing forms?

- If pure optionality is excluded, what are the features they specialize for?

- Are there any observable patterns that may be reduced to contact with Italian?12

- Null hypothesis: determiners freely co-vary with one another. There is optionality in the expression of indefiniteness.

- Alternative hypothesis: different determiners cannot freely co-vary with one another. Optionality is only apparent, and the occurrence of a given form may be predicted to a certain extent by the syntactic environment and/or the semantic traits of the sentence.

- In Piacentine, the main four determiners presented in (3a–d) are available, but pure optionality in their choice is excluded, as there seems to be a divide between two pairs of determiners: ART and di+art vs. ZERO and bare di.

- ART and di+art are the dominant forms, found in all the investigated contexts. They are the only forms available in wide scope contexts. Bare di is the unmarked form for non-existential indefiniteness (in negative sentences), and together with ZERO specializes for narrow scope.

- The use of ZERO in Piacentine was strengthened by contact with Italian, preventing its loss (as happened in French).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

- (5)

- Traits investigated in the research on Piacentine15:

- Noun class: singular mass vs. plural count nouns.

- Sentence type: episodic sentences (featuring past tense) vs. generic sentences (featuring present tense).

- Polarity: negative vs. positive sentences.

- Aspect: telic vs. atelic predicates.

- Scope of the indefinite: narrow vs. wide.

- Semantic specialization: saliency vs. small interpretation.

- 13 items consisting of forced-multiple choice tasks.16 The choice is not limited to one variant, but the informants could select all the sentences they deem correct (including the selection of none of the variants). The items are structured as follows: a context sentence provides the participants with a background as a base for their judgment. For each introductory sentence, there are 5 possible alternatives. The 5 possible options consist of the same sentence, in which only the indefinite determiner is changed. An example is given in (6).17

| (6) | In t’al to dialët, un astemi dirisal: | ||||

| “In your dialect, a teetotaler would say”: | |||||

| a. | A bev | mia | Ø | vein | |

| I-drink | not | ZERO | wine | ||

| b. | A bev | mia | al | vein | |

| I-drink | not | ART | wine | ||

| c. | A bev | mia | ad | vein | |

| I-drink | not | di | vein | ||

| d. | A bev | mia | dal | vein | |

| I-drink | not | di+art | wine | ||

| e. | A bev | mia | sèrt | vein | |

| I-drink | not | certo | wine | ||

| “I don’t drink wine.” | |||||

- Two forced-multiple choice tasks, which require the informant to choose among four possible sentences (each containing a different indefinite determiner, excluding certo). These are pragmatically coherent variant sentences, structured with a causative subordinate clause or with a coordination. An example is given in (7).

- (7)

- Lesa ogni ragion fein in fonda e signa cu ch’è scrit ma ‘t diris.

| a. | A disnè | incӧ | ho | mia | buì | Ø | acqua |

| at-lunch | today | I-have | not | drank | ZERO | water | |

| parché | la sèva | ad | candegina | ||||

| because | it-tasted | of | chlorine | ||||

| b. | A disnè | incӧ | ho | mia | buì | l’ | acqua |

| at-lunch | today | I-have | not | drank | ART | water | |

| parché | la sèva | ad | candegina | ||||

| because | it-tasted | of | chlorine | ||||

| c. | A disnè | incӧ | ho | mia | buì | d’ | acqua |

| at-lunch | today | I-have | not | drank | di | water | |

| parché | la sèva | ad | candegina | ||||

| because | it-tasted | of | chlorine | ||||

| d. | A disnè | incӧ | ho | mia | buì | dl’ | acqua |

| at-lunch | today | I-have | not | drank | di | water | |

| parché | la sèva | ad | candegina. | ||||

| because | it-tasted | of | chlorine | ||||

| “Today, at lunch, I didn’t drink water because it tasted like chlorine.” | |||||||

- Six open comments referred to some of the multiple-choice tasks. The comments are relative to possible differences in the meaning and the interpretation of competing options in case the informant chose more than one. An example of this task is reported in (8).

- (8)

- Sa t’è sarnì püsè ‘d ‘na risposta in (X), at sa ‘d vis c’ag sia ‘na difareinsa ad cu ch’i vӧn dì tra vüna e l’ètra? Pӧt aspieghè quèl ela?“If you chose more than one answer in (X), do you think there is a difference in meaning among them? Could you explain it?”

- Three concluding questions on the linguistic attitude of the participants. These ask about the confidence in their judgments, their linguistic attitude, and the personal appreciation of the task they had to fulfill. The first of these questions is reported here in (9) as an example.

- (9)

- A pinsè a la manera ca t’è cumpilè ‘l dumandi, cus dirisat?“Thinking about the way you answered the questions, what would you say?”

- Ho sempar sarnì sicür/sicüra, sensa aveg di dübi,“I have always been sure, without having doubts”;

- G’ho avì di dübi, ma ad solit s’era sicür/sicüra ca, “l me risposti i fisan giüsti”“I had some doubts, but generally I was sure that my answers were correct”;

- Specialment par sèrti dmandi sum mia sicür/sicüra d’avé dat la risposta giüsta,“Especially for some questions I am not sure I gave the right answer”.

- The questionnaire concludes with the request of the consensus to use the data (cf. the statements in Supplementary Materials).

2.2. Method of Submission

- The request of talking in Piacentine during the entire task to avoid interferences from Italian.

- The fact that the questionnaire was not a test (pointing out that there were no wrong or right answers), but only a tool to gain linguistic data thanks to the native competence of the participant.

- The fact that participants could choose all and only the possible variants they deemed correct, but they could also reject all of them.

- The possibility of asking the interviewer to repeat a sentence if it was not understood, as well as looking at the printed version of the questionnaire if something was unclear.

2.3. Participants

- Gender:

- ○

- M (male): 6 subjects.

- ○

- F (female): 10 subjects.18

- Age (in number of years):

- ○

- A (range up to 30): 5 subjects.

- ○

- B (range 31–60): 6 subjects.

- ○

- C (range above 61): 5 subjects.

- Level of education:

- ○

- E (elementary school): 3 subjects.

- ○

- M (middle school): 1 subject.

- ○

- S (high school): 9 subjects.

- ○

- U (university): 3 subjects.

2.3.1. Use of Piacentine

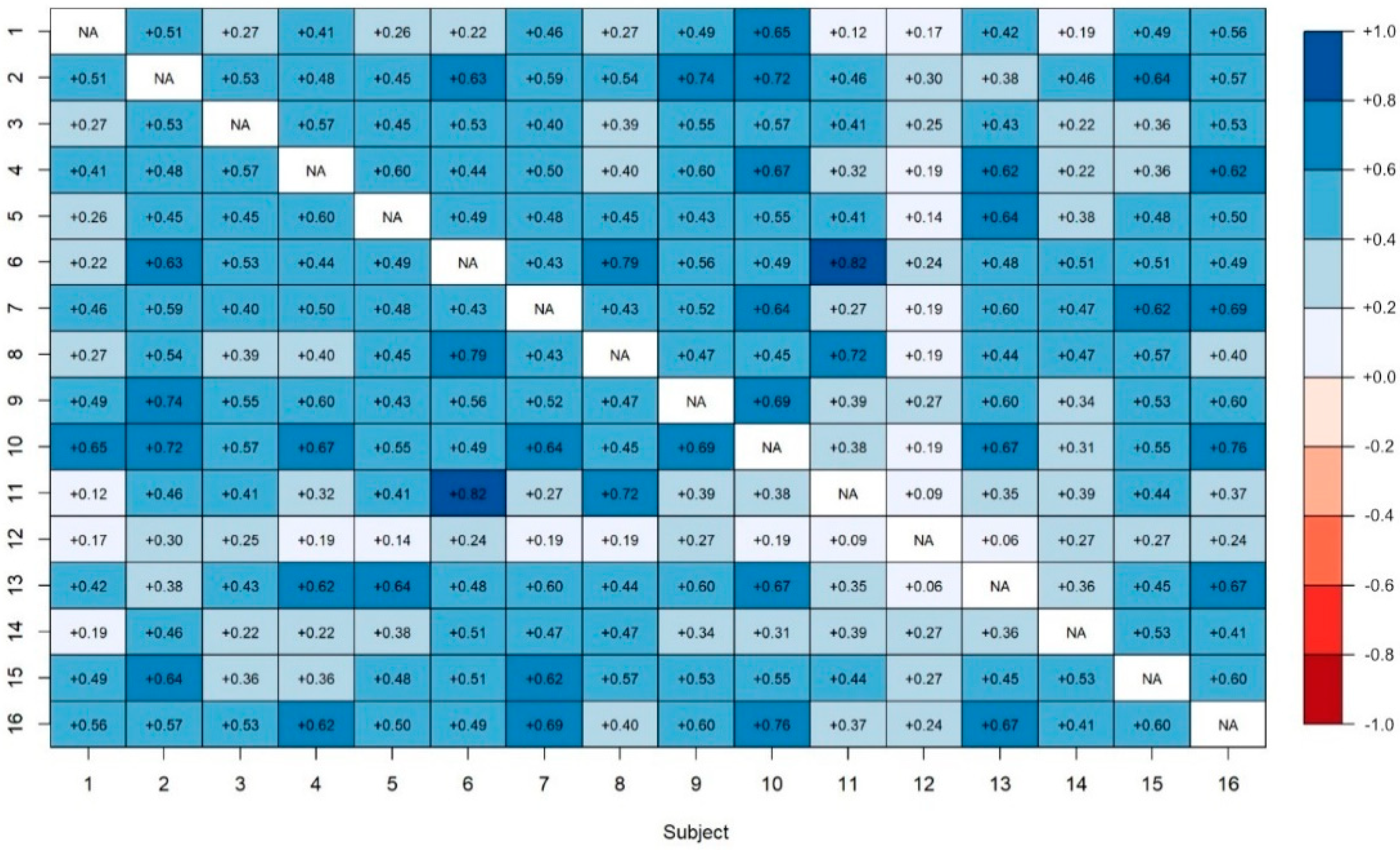

2.3.2. Inter-Subject Agreement

2.4. Data Analysis

- -

- Each column contained a relevant variable (subject number, item question, relevant syntactic trait, answer, etc.).

- -

- Each row encoded all the relevant information concerning one single sentence among those that could be chosen by the participants (e.g., (6a–e)). The (un)acceptability of a given sentence could assume the values ”0” or “1”. “1” represented the case in which a particular sentence among the other options was chosen (i.e., that option is grammatical); the options which were not selected were instead considered ungrammatical and were assigned “0”.21

3. Results

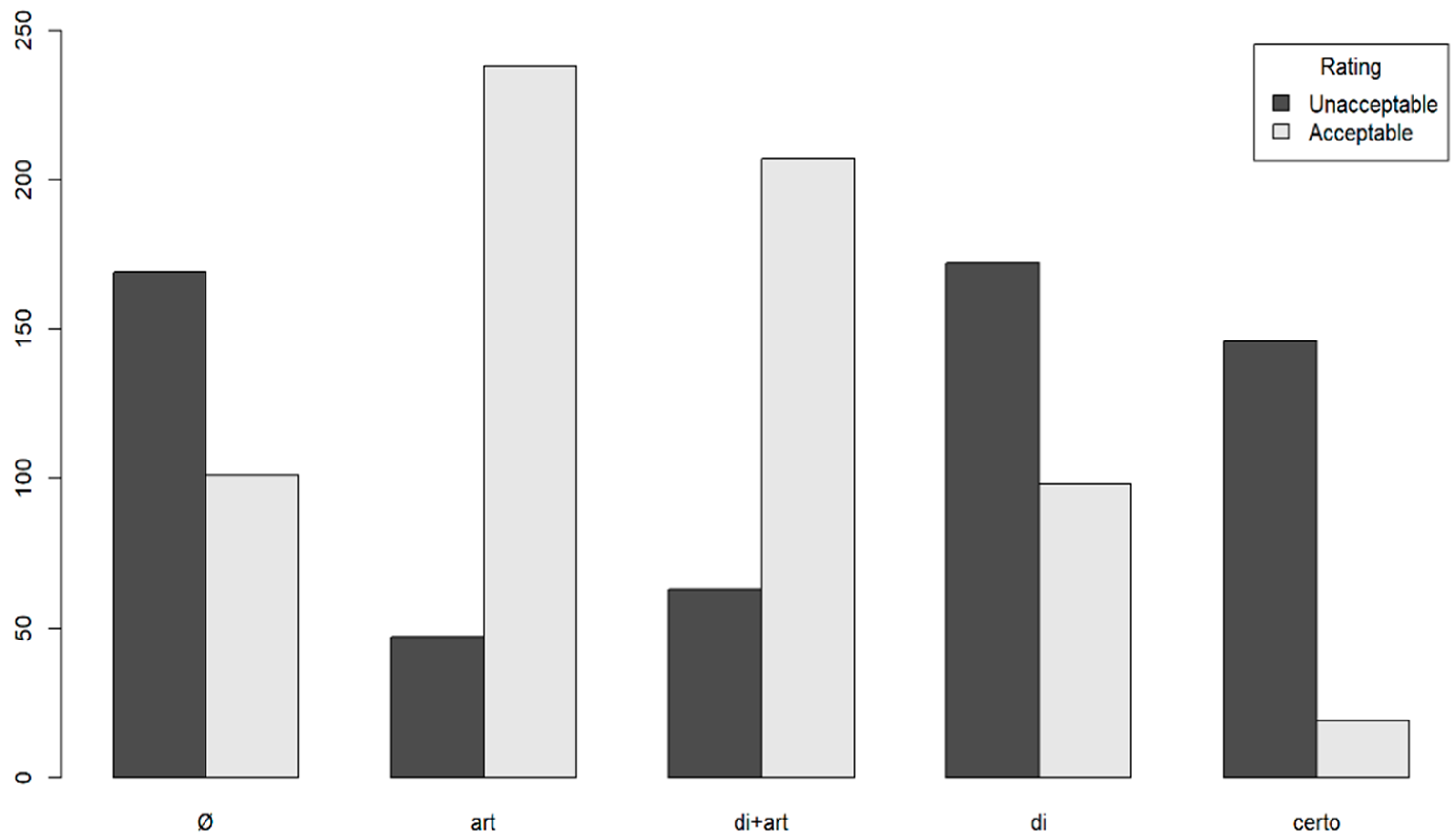

3.1. Overall Acceptability of the Indefinite Determiners

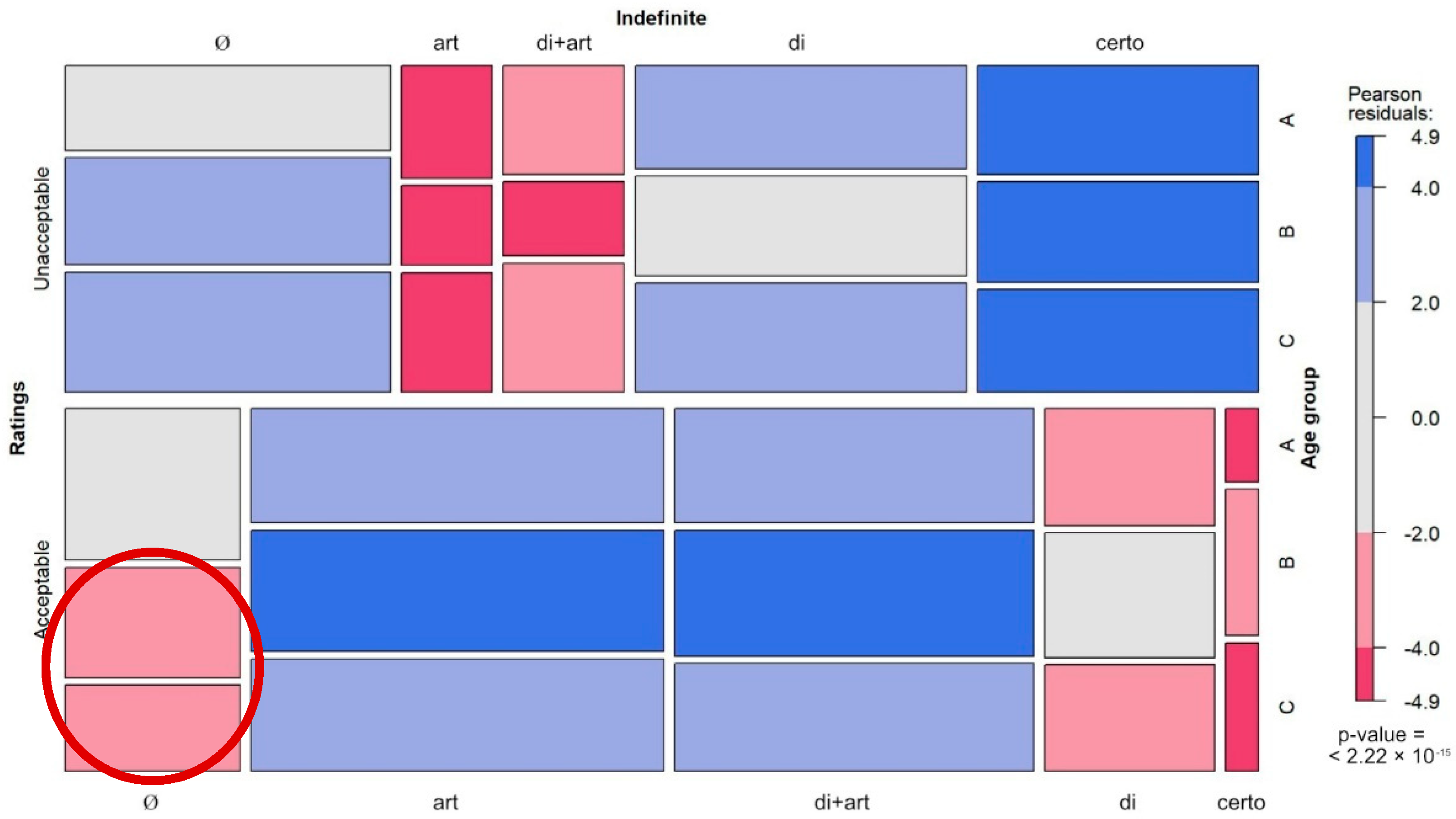

3.2. Acceptability in Age Groups

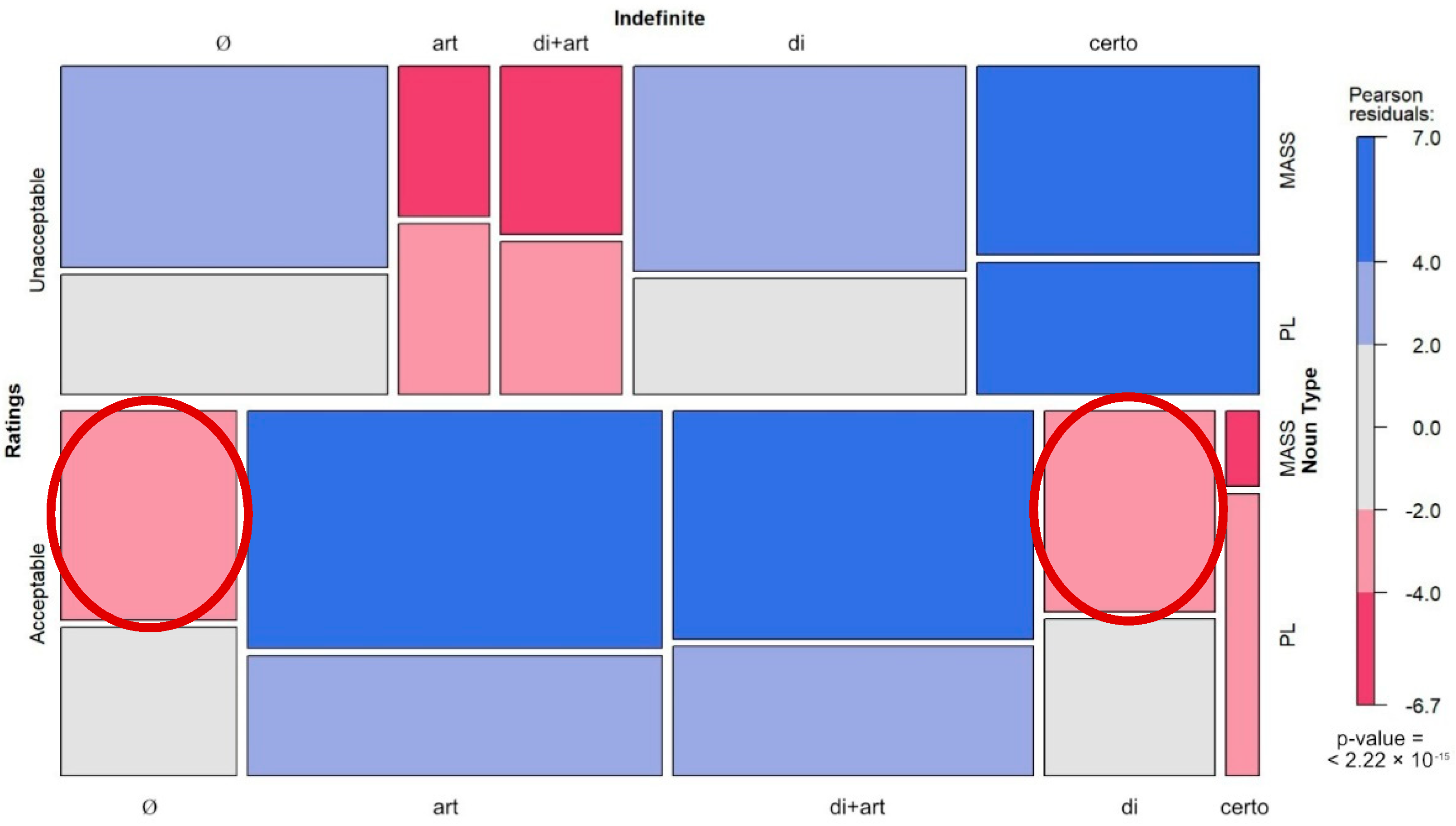

3.3. Acceptability with Noun Class

3.4. Acceptability with Different Polarity

3.5. Acceptability with Different Clause Type

3.6. Acceptability with Different Aspect

3.7. Acceptability with Different Scope

3.8. Acceptability of the Indefinite Determiners with Different Contexts

4. Discussion

- (10)

- Research questions for the study on Piacentine:

- How many and which indefinite determiners are available in Piacentine?

- If more than one indefinite determiner is available (as expected), is there optionality in the choice of competing forms?

- If pure optionality is excluded, which are the features they specialize for?

- Are there any observable patterns which may be reconducted to the contact with Italian?

4.1. Available Indefinite Determiners

4.2. Optionality among Determiners?

4.3. ART and di+art

4.3.1. ART and di+art in Italian

| (11) | a. | Gianni | (non) | ha | mangiato | Ø / | i / | dei | biscotti | |||

| John | not | has | eaten | ZERO | ART | di+art | biscuits | |||||

| “John ate biscuits.” | ||||||||||||

| b. | (Non) | ho | messo | Ø / | il / | del | sale | nell’ | acqua | |||

| not | [I] have | put | ZERO | ART | di+art | salt | in-the | water | ||||

| “I put salt in the water” | ||||||||||||

| (12) | a. | Non | mangio | Ø | / | la | pasta. | |||||

| not | [I] eat | ZERO | ART | pasta | ||||||||

| “I don’t eat pasta.” | ||||||||||||

| b. | #Non | mangio | della | pasta. | ||||||||

| not | [I] eat | di+ART | pasta | |||||||||

| “I don’t eat some pasta.” | ||||||||||||

| (13) | Non | ho | visto | dei | ragazzi. |

| not | [I] have | seen | di+art | boys | |

| “I didn’t see some boys/any boy.” | |||||

| Possible continuations:a. Ho visto Gianni e Maria, ma non ho visto Mario e Teresa.“I saw Gianni and Maria, but I didn’t see Mario and Teresa.”b. Ho visto solo (dei) bambini.“I only saw children.” | |||||

| (14) | Non | ho | bevuto | del | vino. |

| not | [I] have | drunk | di+art | wine | |

| “I didn’t drink wine.” | |||||

| Possible continuations:a. #Ho bevuto (del) Prosecco e (del) Cabernet, ma non ho bevuto (del) Ribolla o (del) Sauvignon.#”I drank (some) Prosecco and (some) Cabernet, but I didn’t drink Ribolla or Sauvignon.”b. Ho bevuto solo (dei) liquori e (dell’)acqua minerale.“I only drank (some) liqueurs and (some) mineral water.” | |||||

| (adapted from Cardinaletti and Giusti 2016, p. 60) | |||||

| (15) | Non | ho | invitato | i | ragazzi | alla | festa… |

| not | [I] have | invited | ART | boys | at-the | party | |

| “I didn’t invite the boys at the party…” | |||||||

| a. ma solo (delle/le) ragazze“but only (the) girls”b. #perché erano antipatici“because they were obnoxious.” | |||||||

| (adapted from Cardinaletti and Giusti 2018, pp. 144–45) | |||||||

| (16) | Maria | ha | raccolto | Ø | / | le | fragole | per | un’ | ora. |

| Maria | has | picked | ZERO | ART | strawberries | for | an | hour | ||

| “Maria picked strawberries for an hour.” | ||||||||||

| (17) | Maria | ha | raccolto | *(le) | fragole | in | un’ | ora | ||

| Maria | has | picked | ART | strawberries | in | an | hour | |||

| “Maria picked the strawberries in an hour.” | (adapted from Cardinaletti and Giusti 2020, p. 282) | |||||||||

4.3.2. ART and di+art in French

| (18) | a. | Jean | a | mangé | des | biscuits. | ||

| Jean | has | eaten | di+art | biscuits | ||||

| ‘Jean ate (some of the) biscuits.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Jean | a | bu | du | café. | |||

| Jean | has | drunk | di+art | coffee | ||||

| ‘Jean drank (some of the) coffee.’ | (adapted from Ihsane 2008, p. 142) | |||||||

| (19) | a. | #J’ai | vu | les | lions. | |||

| [I] have | seen | ART | lions | |||||

| “I have seen the lions.” (specific) | ||||||||

| b. | J’ai | vu | des | lions. | ||||

| [I] have | seen | di+art | lions | |||||

| “I have seen some lions.” | (adapted from Le Bruyn 2010, p. 116) | |||||||

| (20) | a. | Jeanne | mange | les | pommes. | |||

| Jeanne | eats | ART | apples | |||||

| “Jeanne eats apples.“ (habitual)28/“Jeanne is eating the apples.” (non-habitual) | ||||||||

| b. | Jeanne | mange | des | pommes. | ||||

| Jeanne | eats | di+art | apples | |||||

| “Jeanne eats apples.“ (habitual)/“Jeanne is eating apples.” (non-habitual) | ||||||||

| (adapted from Behrens 2005, p. 285) | ||||||||

| (21) | a. | Des | enfants | viennent | jouer. | ici | tous | les | jours. | |

| di+art | children | come | playing | here | all | the | days | |||

| “Children/The children come playing here all the days.” | ||||||||||

| b. | *De l’ | étoffe | que | j’avais | achetée | hier | traînait | par | terre. | |

| di+art | material | that | I had | bought | yesterday | lay-about | on | floor | ||

| (Bosveld-de Smet 1998, 33ff. apud Ihsane 2008, p. 139) | ||||||||||

| (22) | Marie | a cueilli | des | fraises | pendant | des heures | /*en | une | heure. |

| Mary | picked | di+art | strawberries | for | hours | in | one | hour | |

| “Mary picked strawberries for hours/*in an hour.” | |||||||||

| (23) | Marie | a cueilli | les | fraises | en | une | heure/ | *pendant | des heures. |

| Marie | picked | ART | strawberries | in | one | hour | for | hours | |

| “Marie picked the strawberries in an hour/*for hours.” | |||||||||

| (adapted from Ihsane 2008, p. 230) | |||||||||

4.3.3. ART and di+art in Piacentine

| (24) | a. | A mangi | mia | al | / | dal | patèti. | |||||

| I eat | not | ART | di+art | potatoes | ||||||||

| “I don’t eat potatoes.” | ||||||||||||

| b. | A bev | mia | al | / | dal | vein. | ||||||

| I drink | not | ART | di+art | wine | ||||||||

| “I don’t drink wine.” | ||||||||||||

| (25) | a. | Teresa | l’é andè | dal | maslein | a | cumprè | al / | dal | bistechi | ||

| Teresa | she-went | to-the | butcher | to | buy | ART | di+art | steaks | ||||

| “Teresa went to the butcher to buy steaks.” | ||||||||||||

| b. | A disnè | incӧ | ho | mia | buì | l’ | acqua | ma | admé | al | vein | |

| at lunch | today | [I]have | not | drank | ART | water | but | only | ART | wine | ||

| b’. | A disnè | incӧ | ho | mia | buì | dl’ | acqua | ma | admé | dal | vein | |

| at lunch | today | [I] have | not | drank | di+art | water | but | only | di+art | wine | ||

| “For lunch today I didn’t drink water but only wine.” | ||||||||||||

| (26) | Ala | festa, | ho | mia | invidè | i | / | di | ragas, |

| at-the | party | [I] have | not | invited | ART | di+art | boys | ||

| a. | ma admé ragasi. | ¬Ǝ | |||||||

| “but only girls.” | |||||||||

| b. | parché i eran antipatic. | Ǝ¬ | |||||||

| “because they were obnoxious.” | |||||||||

| (27) | a. | Ho | tajè | l’ | erba / | dl’ | erba | pr’ | un’ura |

| [I] have | cut | ART | grass | di+art | grass | for | one hour | ||

| “I have mowed grass for an hour.” | |||||||||

| b. | Ho | tajè | l’ | erba / | dl’ | erba | in t’ | un’ura | |

| [I] have | cut | ART | grass | di+art | grass | in | one hour | ||

| “I mowed the grass in an hour.” | |||||||||

4.4. Bare di

4.4.1. Bare di in French

| (28) | a. | Il | a | du | papier. | ||||

| he | has | di+art | paper | ||||||

| a’. | Il | n’ | a | pas | de | papier. | |||

| he | NE | has | not | di | paper | ||||

| “He has paper/He doesn’t have paper.” | |||||||||

| b. | Il | a | des | papiers. | |||||

| He | has | di+art | papers | ||||||

| “He has papers/He doesn’t have papers.” | (adapted from Ihsane 2005, p. 205) | ||||||||

| b’. | Il | n’ | a | pas | de | papiers. | |||

| he | NE | has | not | di | papers | ||||

| “He has papers/He doesn’t have papers.” | (adapted from Ihsane 2005, p. 205) | ||||||||

| (29) | a. | Marie | n’ | a | pas | vu | de | fantôme. | |

| Marie | NE | has | not | seen | di | ghost | |||

| “Marie hasn’t seen a ghost.” | |||||||||

| b. | *Marie | a | vu | de | fantôme. | ||||

| Marie | has | seen | di | ghost | (adapted from Ihsane 2008, p. 79) | ||||

4.4.2. Bare di in Piacentine

| (30) | a. | A | mangi | mia | Ø/ | ad | chèran. |

| I | eat | not | ZERO | di | meat | ||

| “I don’t eat meat.” | |||||||

| b. | A | mangi | mia | Ø/ | ad | patèti. | |

| I | eat | not | ZERO | di | potatoes | ||

| “I don’t eat potatoes.” | |||||||

| (31) | Ala | festa, | ho | mia | invidè | ad | ragas, |

| at-the | party | [I] have | not | invited | di | boys | |

| “At the party I didn’t invite boys.” | |||||||

| a. | ma admé ragasi. | ¬Ǝ | |||||

| “but only girls” | |||||||

| b. | *parché i eran antipatic. | *Ǝ¬ | |||||

| “because they were obnoxious” | |||||||

4.5. ZERO

4.5.1. ZERO in Italian

| (32) | Non | ho | invitato | Ø | ragazzi | alla | festa… |

| not | [I] | have invited | ZERO | boys | at-the | party | |

| “I didn’t invite boys at the party…” | |||||||

| a. | ma solo ragazze. | ||||||

| “but only girls” | |||||||

| b. | *perché erano antipatici. | ||||||

| “because they were obnoxious” | |||||||

| (adapted from Cardinaletti and Giusti 2018, pp. 144𠄳45) | |||||||

4.5.2. ZERO in Piacentine

| (33) | Ala | festa, | ho | mia | invidè | Ø | ragas, |

| at-the | party | [I] | have not | invited | ZERO | boys | |

| “At the party I didn’t invite boys” | |||||||

| a. | ma admé ragasi | ¬Ǝ | |||||

| “but only girls” | |||||||

| b. | *parché i eran antipatic | *Ǝ¬ | |||||

| “because they were unpleasant” | |||||||

4.6. Limitations and Further Research

5. Conclusions

- Piacentine mainly has four determiners for expressing indefiniteness: ART, di+art, bare di, and ZERO.

- There is no pure optionality in the expression of indefiniteness. There is however a divide between two pairs of determiners: ART and di+art vs. ZERO and bare di.

- ART and di+art are the dominant forms in all the investigated contexts. They are the only forms which can have wide scope interpretation. In the investigated contexts, these two determiners are almost always in competition (with the possible exception of generic positive sentences), so a certain degree of optionality between them seems to exist. Di+art is much more widespread in Piacentine than in Italian and is half a way between the partitive determiner in Italian and in French.

- Bare di is the unmarked form for non-existential indefiniteness: it only occurs in negative sentences and only has a narrow scope. Its behavior perfectly reflects that of French de. This is not surprising, given the Gallic origin of this determiner.

- Since bare di corresponds to its French counterpart and ART behaves in the same way as in Italian, the features of Piacentine di+art (which behaves slightly differently both from Italian and French) may be the result of the “mixed” nature of its components.

- ZERO has roughly the same distribution and properties of bare di. However, its higher acceptability by Group A suggests that in Piacentine the use of this determiner was strengthened in contact with Italian, preventing its loss as has happened in Middle French.

| (34) | C[f1,f2] | { | ART[g1,uf1] |

| di+art[g1,uf2] |

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | For convenience, I am adopting here Cardinaletti and Giusti’s (2018) labeling for the indefinite determiners under investigation and I will maintain the same labels both for Italian and for the variety spoken in the province of Piacenza. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | The numeral due “two” can also be used as marker of indefiniteness, conveying the semantics of a small quantity. However, its distribution is still very restricted as it has not fully grammaticalized into an indefinite determiner. For this reason, it was left aside in the present research. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Since the present study aimed at investigating the nominal expressions that apparently display a great deal of optionality (i.e., more than two choices), singular count nouns were not considered as they generally only combine with the indefinite article and display no optionality. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | These maps (Jaberg and Jud 1928–1940) report the translation of specific sentences or phrases in each the local variety on the peninsular territory. They present a snapshot of the Italo-Romance varieties at the beginning of the last century. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | This is caused by lateral areas (Cardinaletti and Giusti 2018, p. 150): ART represents the innovation with respect to Latin ZERO. The innovation starts spreading from the center towards the borders: the lateral areas, being more conservative, still retain the Latin inheritance. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Indeed, the bare determiner di is a Gallic innovation (Rohlfs 1968, p. 117), spreading from today’s France. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Cardinaletti and Giusti (2018) capture the variation in the different realization of these determiners via the interplay of a micro- and a nanoparameter regulating the (non-)realization of the head and the specifier of the Determiner Phrase (DP). This combination gives four possibilities (cf. (i)), corresponding to the four determiners listed in (3a–d). (i) [SpecDP zero/di [D Ø/ART]] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | This is relevant, as Emilia-Romagna is the region in which Piacentine is spoken. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | The varieties spoken in this province are not unknown to the linguistic literature. However, the existing studies focusing on Piacentine mainly concern its clitic system (cf. e.g., Cardinaletti and Repetti 2008). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Italian in this case acts as a ceiling language (Loporcaro 2009, p. 8), i.e., it is seen by the speakers as the standard normative language to which the local varieties (in this case, Piacentine) need to conform to. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Hajek (1997) reports homogeneous syntactic patterns in the varieties spoken in Emilia-Romagna. Thus, there are no substantial differences at syntactic level among varieties spoken in the same area (e.g., in the same province). For this reason, the dialect spoken in Lugagnano is assumed to be representative for the variety spoken in the province from a syntactic point of view. Future research will take into account a larger sample, which may include various areas of the province. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | This study did not contain distractors as it was intended as a pilot to gain more insight into the expression of indefiniteness in Piacentine. This guaranteed that the questionnaire (i) was not too long and more accessible also to the oldest participants, and (ii) maintained the same structure of Cardinaletti and Giusti’s (2020) questionnaire, in order to make the results maximally comparable. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | All the indefinites investigated in this research are in object position. This choice was made to maximize the number of possible competing forms. In fact, Italian (among other languages) has a restriction on the kind of determiner, which may appear in the subject position, e.g., bare nominals are generally disallowed, except for particular conditions (cf. Delfitto and Schroten 1991). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | Among the different tasks that may fit into a questionnaire, the multiple-choice task is statistically the most powerful if compared to the Likert scale task and the yes/no task (cf. Schütze and Sprouse 2013). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | The complete list of items contained in the questionnaire can be found in Supplementary Materials. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | All the participants spontaneously identified themselves as being either ‘male’ or ‘female’. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | The output of Krippendorff’s α is a coefficient defined as Inter-Coder Agreement, calculated by comparing each participant’s answer pattern with those of the other subjects. Participants whose answers strongly deviate from the other participants’ patterns are excluded from the pool as they are considered “unreliable”. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | The Excel file is available in Supplementary Materials. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | As this was a forced-choice task (which did not involve judging sentences using a scale of values), the only possible values to be assigned were 0 and 1. For instance, if in the item repoted in (6) (“In your dialect, a teetotaler would say”) a participant chose (6b) (A bev mia al vein “I don’t drink ART wine”), (6c) (A bev mia ad vein “I don’t drink di wine”) and (6d) (A bev mia dal vein “I don’t drink di+art wine”), in the operationalization of the answers (6b), (6c), and (6d) got the score 1, while (6a) and (6e) (which were not chosen) got 0. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | χ2 verifies the probability that the difference found between two variables arose by chance, by comparing the “expected” value of a variable with the “observed” value of that same variable (cf. Gries 2013; Johnson 2013). The direction of this relation (whether the observed value is higher or lower than expected) is indicated by Pearson residuals. They correspond to “the difference between each cell’s observed minus its expected frequency, divided by the square root of the expected frequency. If a Pearson residual is positive/negative, then the corresponding observed frequency is greater/less than its expected frequency. Second, the more the Pearson residual deviates from 0, the stronger that effect.” (Gries 2013, p. 326). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | If 0.05 < p < 0.1, then the difference is “marginally significant”, i.e., there is a tendency. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | When it comes to the expression of indefiniteness, singular count nouns only display one option, i.e., they can only combine with the indefinite article un(o)/a (in Italian) or un/une (in French). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25 | The choice and the scopal behavior of a particular determiner always hinges on a complex interplay of more interacting traits (e.g., polarity, noun class, and sentence type). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27 | French almost completely disallows bare nominals (cf. Delfitto and Schroten 1991), except for some occurrences, e.g., in predicative position, as in the sentence Jean est médicin (lit. ‘Jean is doctor’, de Swart et al. 2007, p. 199). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 | This appears to be a genuine indefinite interpretation of ART and not an instance of kind reference. In fact, consumption verbs such as eat or drink cannot take a kind-referring object (cf. Giusti 2021). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 29 | Ihsane (2008) explains this fact by recalling Bunt’s (1985) homogeneity hypothesis: since the referential use entails that the speaker pick up a specific entity, this is not possible for mass nouns, as their denotation does not contain minimal entities. This trait was not investigated in subject position in the present research. Piacentine di+art seems to display a similar behavior: according to some consulted informants, (i) sounds unnatural and not completely grammatical. This issue deserves further investigation.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30 | All the generic sentences in the questionnaire were negative. In positive generic predicates, di+art features reference to subkind as in Italian (i), according to the author’s judgments and those of some informants. This issue needs further investigation.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31 | All the examples of Piacentine in this and in the following sections are obtained from the questionnaire. The complete array of items can be found in Supplementary Materials. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32 | For the time being, I refrained from claiming here that either ART or di+art is the unmarked form for expressing core indefiniteness in Piacentine. The reason is that both are almost equally widespread. This means that they must operate a division of labour at some syntactic/semantic level, allowing to individuate in which instances they may be taken to be unmarked forms. Further research will hopefully clarify this aspect. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33 | The occurrence of the definite article would yield a definite interpretation, which is maintained even under the scope of the negation, cf. Il a le papier “He has the paper” vs. Il n’a pas le papier “He doesn’t have the paper” (Ihsane 2005, p. 205). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34 | A recent proposal by Lebani and Giusti (2022) assumes the morphosyntactic complexity of the determiners to be directly proportional to the semantic complexity of the context. This hypothesis stems from the analysis of part of Piacentine data presented here and other data from Rodigino considering polarity (NEG vs. POS) and aspect (ATEL vs. TEL). Indefinites in NEG and ATEL lack the presupposition of existence, which is instead favoured in POS and TEL. Thus, NEG and ATEL should be “less complex” than POS and TEL, respectively. Given the syntactic composition of the determiners (cf. fn. 9), according to Lebani and Giusti’s hypothesis NEG and ATEL should display a higher rate of simpler determiners, i.e., ZERO (both SpecDP and D unrealized), ART (only D realized), or di (only SpecDP realized). This prediction is borne out: in NEG and ATEL Piacentine mainly displays di and ART (equally complex), while Rodigino optionally realizes ZERO or ART (as di is not available in this variety). In POS and TEL, instead, both varieties show optionality between ART and di+art, the latter being the most complex determiner (with both SpecDP and D realized). This interesting proposal deserves further attention in future research on Piacentine. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 35 | The structural analysis of di+art has been quite debated. Chierchia (1998) argues that it is a bare partitive construction derived from a canonical partitive construction (cf. (i)) via the incorporation of the definite article into the preposition di (incorporation of D into the immediately dominating P) and then movement of this complex to a higher DP projection through an empty N triggering partitive meaning (cf. (ii)).

The semantics of the bare partitive construction results, according to Chierchia, from the combination of the ι-operator (i.e., the definite article) triggering a presupposition of existence and the partitive reading of the empty N. Zamparelli (2008) elaborates upon the same structural analysis, attributing the peculiar semantics of di+art to the fact that the preposition embeds a kind-denoting DP. An alternative analysis is proposed by Cardinaletti and Giusti (2015a, 2015b, 2016), who show that the partitive determiner syntactically and semantically behaves neither as a partitive construction (as proposed by Chierchia and Zamparelli), nor as a quantified structure like alcuni ragazzi “some boys” (as put forth by Storto (2003). Cardinaletti and Giusti argue that the partitive determiner is the plural counterpart of the singular indefinite article un/a “a(n)”. Given its determiner status, they adopt a minimal DP structure in which the specifier is filled by the invariable determiner di, which is combined with overt morphology (syncretic with the definite article) in the head D. This is due to a mechanism the authors call Compensatory Concord, i.e., the overt realization of the head to compensate for the lack of features in the specifier. The structure is provided in (iii).

Differently from Chierchia’s (and Zamparelli’s) account, whose derivation suffers from a violation of Baker’s (1988) Mirror Principle, Cardinaletti and Giusti’s analysis is in line with the general rules of syntax and does not represent an ad hoc solution, as the same syntactic operation (i.e., Compensatory Concord) intervenes in other cases, e.g., with the demonstrative quei “those. M.PL” and the adjective bei “handsome.M.PL”. Moreover, it is able to reduce the variation of di+art with the other indefinite determiners in terms of micro- and nanoparameters (cf. fn. 9). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 36 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 37 | The approach of multiple grammars and that of probabilities built in the grammar have nothing to say about the rate at which the different variants are found. Combinatorial Variability instead captures the fact that variant X is met more often than Y by assuming that X has different underlying combinations of features, which result in the same superficial form. Thus, X is more likely to surface (as more than one combination of features gives X as the output). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38 | The analysis of the AIS maps does not provide strong evidence, as optionality is disregarded and only one form for each locality is reported. However, map 997 “[cook] butter” reports in Emilia-Romagna some occurrences of ART (e.g., points 413, 443) and di+art (point 424). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Adger, David. 2006. Combinatorial Variability. Journal of Linguistics 42: 503–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, David. 2016. Language variability in syntactic theory. In Rethinking Parameters. Edited by L. Eguren, O. Fernandez-Soriano and A. Mendikoetxea. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2011. Plural Mass Nouns and the Morpho-syntax of Number. In Proceedings of the 28th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Mark. 1988. Incorporation: A Theory of Grammatical Function Changing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berruto, Gaetano. 1974. Piemontese. Pisa: Pacini. [Google Scholar]

- Berruto, Gaetano. 1989. Main topics and findings in Italian sociolinguistics. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 76: 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berruto, Gaetano. 2010. Identifying dimensions of linguistic variation in a language space. In Language and Space: An International Handbook of Linguistic Variation. Edited by Peter Auer and Alfr Lameli. (Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft = Handbooks of linguistics and communication science, Bd. 30.1–Bd.30.3). Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 226–41. [Google Scholar]

- Biberauer, Theresa, and Marc Richards. 2006. True optionality: When the grammar doesn’t mind. In Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today. Edited by Cedric Boeckx. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosveld-de Smet, Leonie. 1998. On Mass and Plural Quantification: The Case of French des/du-NPs. Ph.D. dissertation, Institute for Logic, Language and Computation, Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Brasoveanu, Adrian, and Donka Farkas. 2016. Indefinites. In The Cambridge Handbook of Formal Semantics. Edited by Maria Aloni and Paul Dekker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 238–66. [Google Scholar]

- Buchstaller, Isabelle, and Ghada Khattab. 2013. Population samples. In Research Methods in Linguistics. Edited by Robert J. Podesva and Devyani Sharma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 74–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bunt, Harry. 1985. Mass Terms and Model-Theoretic Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Giuliana Giusti. 1990. Partitive “ne” and the QP-Hypothesis. A Case Study. Ms. University of Venice [Preprint]. Available online: http://157.138.8.12/jspui/bitstream/11707/41/2/cardinaletti.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Giuliana Giusti. 2015a. Cartography and optional feature realization in the nominal expression. In Beyond Functional Sequence: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by U. Shlonsky. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online, pp. 151–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Giuliana Giusti. 2015b. Il determinante indefinito: Analisi sintattica e variazione diatopica. In Plurilinguismo/Sintassi. Edited by Carla Bruno, Simone Casini, Francesca Gallina and Raymond Siebetcheu. Roma: Bulzoni (Atti del XLVI Congresso internazionale SLI), pp. 451–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Giuliana Giusti. 2016. The syntax of the Italian indefinite determiner dei. Lingua 181: 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Giuliana Giusti. 2018. Indefinite Determiners: Variation and Optionality in Italo-Romance. In Advances in Italian Dialectology. Edited by Roberta D’Alessandro and Diego Pescarini. Amsterdam: Brill, pp. 135–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Giuliana Giusti. 2020. Indefinite determiners in informal Italian: A preliminary analysis. Linguistics 58: 679–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Lori Repetti. 2008. The Phonology and Syntax of Preverbal and Postverbal Subject Clitics in Northern Italian Dialects. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 523–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlier, Anne. 2007. From Preposition to Article: The Grammaticalization of the French Partitive. Studies in Language 31: 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerruti, M. 2021. Variazione sociolinguistica e processi di grammaticalizzazione. Tipologia e sociolinguistica: Verso un approccio integrato allo studio della variazione. Atti del workshop della Società Linguistica Italiana, 10 settembre 2020 5: 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, Jack K. 1995. Sociolinguistic Theory. Linguistic Variation and its Social Significance. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Chierchia, Gennaro. 1998. Partitives, Reference to Kinds and Semantic Variation. In Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory. Edited by Aaron Lawson. Ithaca: Cornell University: CLC Publications, pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on Government and Binding. Studies in Generative Grammar, 9. Dordrecht and Cinnaminson: Foris Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corblin, Francis, Ileana Comorovski, Brenda Laca, and Claire Beyssade. 2004. Generalized quantifiers, dynamic semantics, and French determiners. In Handbook of French Semantics. Edited by Francis Corblin and Henrinëtte de Swart. Stanford: CSLI, pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- de Swart, Henrinëtte, Yoad Winter, and Joost Zwarts. 2007. Bare nominals and reference to capacities. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25: 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Delfitto, Denis, and Jan Schroten. 1991. Bare plurals and the number affix in DP. Probus 3: 155–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowty, David. 1979. Word Meaning and Montague Grammar—The Semantics of Verbs and Times in Generative Semantics and in Montague’s PTQ. Dordrecht: Reidel Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Fodor, Janet Dean, and Ivan Andrew Sag. 1982. Referential and quantificational indefinites. Linguistics and Philosophy 5: 355–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, Giuliana. 2021. A Protocol for Indefinite Determiners in Italian and Italo-Romance. In Disentangling Bare Nouns and Nominals Introduced by a Partitive Article. Edited by Tabea Ihsane. Leiden: Brill, pp. 262–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, Stefan Thomas. 2013. Basic significance testing. In Research Methods in Linguistics. Edited by Robert J. Podesva and Devyani Sharma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 316–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hajek, John. 1997. Emilia-Romagna. In The Dialects of Italy. Edited by Martin Maiden and Mair Parry. London: Routledge, pp. 271–78. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, Irene. 1982. The Semantics of Definite and Indefinite Noun Phrases. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachussets Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ihsane, Tabea. 2005. On the structure of French du/des “of.the” constituents. GG@G (Generative Grammar in Geneva) 4: 195–225. [Google Scholar]

- Ihsane, Tabea. 2008. The Layered DP: Form and Meaning of French Indefinites. Linguistik aktuell = Linguistics today, v. 124. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Jahberg, Karl, and Jud Jakob. 1928–1940. Sach-und Sprachatlas Italiens und der Südschweiz, Ringier. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/sprach-und-sachatlas-italiens-und-der-sudschweiz/oclc/12210881#relatedsubjects (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Johnson, Daniel Ezra. 2013. Descriptive statistics. In Research Methods in Linguistics. Edited by Robert J. Podesva and Devyani Sharma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 288–315. [Google Scholar]

- Krifka, Manfred. 1989. Nominal Reference, Temporal Constitution and Quantification in Event Semantics. In Semantics and Contextual Expression. Edited by Renate Bartsch, Johan van Benthem and Peter van Emde Boas. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 75–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2011. Computing Krippendorff’s Alpha-Reliability. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/43 (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- Kroch, Anthony S. 1989. Reflexes of grammar in patterns of language change. Language Variation and Change 1: 199–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Labov, William. 1969. Contraction, Deletion, and Inherent Variability of the English Copula. Language 45: 715–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, William. 1972. Language in the Inner City: Studies in the Black English Vernacular. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bruyn, Bert Simonne Walter. 2010. Indefinite Articles and Beyond. LOT, 238. Utrecht: LOT, Landelijke Onderzoekschool Taalwetenschap. [Google Scholar]

- Lebani, Gianluca E., and Giuliana Giusti. 2022. Indefinite determiners in two northern Italian dialects: A quantitative approach. Isogloss. Open Journal of Romance Linguistics 8: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levshina, Natalia. 2015. How to do Linguistics with R. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Loporcaro, Michele. 2009. Profilo Linguistico dei Dialetti Italiani. Bari: Editori Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Molinari, Luca. 2020. The Expression of Indefiniteness and Optionality in the Dialect of Piacenza. MA thesis in Language Sciences. Venezia: Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Gereon. 2003. Optionality in Optimality-Theoretic Syntax. In The Second Glot International State-of-the-Article Book: The Latest in Linguistics. Edited by Lisa Lai Shen Cheng and Rint P. E. Sybesma. Studies in Generative Grammar, 61. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 289–321. [Google Scholar]

- Poplack, Shana, and Stephen Levey. 2010. Contact-induced grammatical change: A cautionary tale. In Language and Space: An International Handbook of Linguistic Variation. Edited by Peter Auer and Alfr Lameli. Handbücher zur Sprach-und Kommunikationswissenschaft = Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science, Bd. 30.1-Bd.30.3. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 391–419. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Glenville. 2000. Encyclopedia of European Languages. London: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, Alan, and Paul Smolensky. 1993. Optimality Theory: Constraint Interaction in Generative Grammar. Cambridge: MIT Press, Available online: roa.rutgers.edu/view.php3?roa=537 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- R Core Team. 2020. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfs, G. 1968. Grammatica Storica della Lingua Italiana e dei Suoi Dialetti. Morfologia. Torino: Giulio Einaudi editore. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Bertrand. 1905. On Denoting. Mind 14: 479–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, Carson T., and Jon Sprouse. 2013. Judgment data. In Research Methods in Linguistics. Edited by Robert J. Podesva and Devyani Sharma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jennifer. 2000. Synchrony and Diachrony in the Evolution of English: Evidence from Scotland. Ph.D. dissertation, University of York, York, UK. Available online: https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/10887/1/326420.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Sorace, Antonella. 2000. Syntactic optionality in non-native grammars. Second Language Research 16: 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Storto, Gianluca. 2003. On the Status of the Partitive Determiner in Italian. In Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Edited by Josep Quer, Jan Schroten, Mauro Scorretti, Petra Sleeman and Els Verheugd. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 315–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winter, Bodo. 2019. Statistics for Linguists: An Introduction Using R, 1st ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamparelli, Roberto. 2008. Dei ex machina: A note on plural/mass indefinite determiners. Studia Linguistica 62: 301–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Age | Total Gender | Total Education | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | M | F | E | M | S | U |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molinari, L. Optionality in the Expression of Indefiniteness: A Pilot Study on Piacentine. Languages 2022, 7, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020099

Molinari L. Optionality in the Expression of Indefiniteness: A Pilot Study on Piacentine. Languages. 2022; 7(2):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020099

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolinari, Luca. 2022. "Optionality in the Expression of Indefiniteness: A Pilot Study on Piacentine" Languages 7, no. 2: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020099

APA StyleMolinari, L. (2022). Optionality in the Expression of Indefiniteness: A Pilot Study on Piacentine. Languages, 7(2), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020099