Abstract

Although classifier constructions generally aim for highly iconic depictions, like any other part of language they may be constrained by phonology. We compare utterances containing motion events between signers of Cena, an emerging rural sign language in Brazil, and Libras, the national sign language of Brazil, to investigate whether a difference in time-depth—a relevant factor in phonological reorganisation—influences trade-offs involving iconicity. First, we find that contrary to what may be expected, given that emerging sign languages exhibit great variation and favour highly iconic prototypes, Cena signers exhibit neither greater variation nor the use of more complex handshapes in classifier constructions. We also report a divergence from findings on Nicaraguan Sign Language (NSL) in how signers encode movement in a young language, showing that Cena signers tend to encode manner and path simultaneously, unlike NSL signers of comparable cohorts. Cena signers therefore pattern more like non-signing gesturers and signers of urban sign languages, including the Libras signers in our study. The study contributes an addition to the as-yet limited investigations into classifiers in emerging sign languages, demonstrating how different aspects of linguistic organisation, including phonology, can interact with classifier form.

1. Introduction

Classifiers present a ubiquitous, rich, and productive morphological category of structures within sign languages. Despite the myriad ways in which they exploit iconic properties of the referent they depict, similar to sublexical units of a language, their features may also be constrained by phonology. As phonological reorganisation takes place over time (Frishberg 1975; Brentari et al. 2012; Senghas et al. 2004), our study compares results from the same production task between signers of Cena, an emerging sign language of north-eastern Brazil in its third generation, and Libras, the national sign language of Brazil, to determine how handshape complexity and variation fare in two languages of different ages and sociolinguistic profiles. We aim to investigate the question of whether in a language of relative youth, we find more complex and varied classifier handshapes given that classifiers are likely unconventionalised, thus putting a greater burden on recoverability through strategies such as iconic depiction. We also explore how signers choose to encode manner and path in motion events. Considering existing findings from signers of Nicaraguan Sign Language (NSL) illustrating that later-cohort signers show a greater preference for encoding manner and path sequentially relative to earlier-cohort signers, we are interested in whether this departure from iconic depiction represents a developmental stage of emerging sign languages generally, or whether it may be specific to the conditions under which NSL emerged.

In Section 1, we provide background on classifiers in sign languages, providing a brief summary of common categorisations of classifier types. The section also details how the phonological features of classifier complexity may be reorganised in predictable ways over time and provides a model of quantifying complexity based on the prosodic model (Brentari 1998). Finally, Section 1 contextualises both languages in the study and the cultural contexts in which they are used. Section 2 details the Haifa Clips communicative production task, developed for Sandler et al. (2005), in which signers describe basic motion events to another native signer who must correctly identify the events, and our subsequent analysis methods. Section 3 provides results, finding that, overall, Cena signers do not appear to make as much use of more complex handshapes as we may have expected given young sign languages’ propensity for iconic depiction (Sandler et al. 2011; Hou 2016), and although we do find more handshape variants in one type of classifier in Cena, these may be accounted for by assimilation. Our results also show how in their encoding of movement, both Libras and Cena signers pattern more like gesturers, early-cohort NSL signers, and signers of urban sign languages. Section 4 presents discussion of the findings. We consider and further break down results in terms of complexity and variation in this section, before discussing our conclusions in Section 5.

1.1. Classifiers in Sign Languages

1.1.1. An Overview

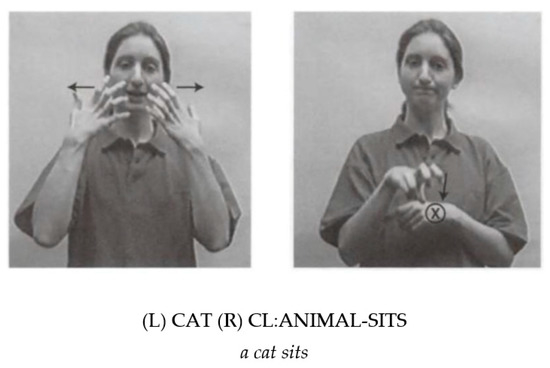

Classifiers are handshapes that denote a broad class of referents such as vehicles, people, or round objects within a given sign language. In this way, they function similarly to those of spoken languages, although in the interests of space we will not include a detailed comparison here1. Handshape is usually described as one of the sub-lexical building blocks of signs that combines with location and movement to form meaningful signs, much in the same way meaningless sounds combine to form words in spoken language. However, handshapes as they exist in classifiers are morphemic; simply put, they are meaningful. Classifiers may be combined with particular movement or location specifications to depict verb events, forming what we will call classifier constructions, although labels in the literature vary (c.f. Engberg-Pedersen 2010 for classifier signs; Cormier et al. 2012 for depicting constructions) depending on which model of proposed classifier representation and structure one may subscribe to. Examples of classifier constructions from British Sign Language (BSL) (Sutton-Spence and Woll 1999) and Hong Kong Sign Language (HKSL) (Tang and Yang 2007) are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. In Figure 1, the signer first produces the lexical sign CAT in the image on the left, and on the right depicts an action performed by the referent with a BSL animal classifier and a motion verb. The construction in Figure 2 combines a vehicle classifier with a verb of motion producing a vehicle arrives. Both classifiers pick out some visual characteristic of the referent—the vehicle classifier depicts the overall shape, whereas the animal classifier highlights the salient property of its legs. This exemplifies what is known as iconicity, which features heavily in classifiers—some motivated relationship between form and meaning.

Figure 1.

An animal classifier used in a classifier construction ‘a cat sits’ in BSL. Reprinted with permission from Sutton-Spence and Woll. Cambridge University Press 1999.

Figure 2.

A vehicle classifier used in a classifier construction in HKSL. Reprinted with permission from Tang and Yang. 2007 Elsevier.

Classifiers vary in the properties of their referents they pick out and how they do so. In his early analysis of American Sign Language (ASL) classifiers, Supalla (1982, 1986) proposed five types: (i) size and shape specifiers (hereby SaSSes), which denote a referent by depicting its size or physical form; the hands may statically show the outer edges of the object to show its height or width (such as the thickness of a book), or they may trace its shape (such as the outline of a Christmas tree); (ii) semantic classifiers, depicting a general semantic class of objects such as an animal in Figure 1 or vehicle in Figure 2, but may be manipulated to show additional or specific details; Supalla (1986) gives the example of a tree classifier—a signer is free to modify this broad semantic category classifier to show the type of tree, be it a palm or weeping willow; (iii) body classifiers, which use the body of the signer to denote the whole body of an animate referent; (iv) body part classifiers in which parts of the body represent themselves; and (v) instrument classifiers, indirectly denoting a referent through depicting its handling or manipulation. In the manipulation of the referent object, the hands can represent themselves, or a tool being manipulated (one may think of a flat hand moved in a sawing motion to represent a knife).

Since Supalla’s work, many other categories have been proposed for ASL and other languages, and terminology varies (see Tang et al. 2021 for a recent overview). Studies also vary in the number of proposed sub-types of classifiers, but the same two main types of classifiers persist throughout much of the literature even when additional categories are also proposed:

- Whole entity classifiers, in which the hand or hands directly represent a whole object. They denote a general class of objects (e.g., people, vehicles, four-legged animals) using some aspect of their form, though their iconicity can vary in its transparency. Some consider this category to include SaSSes (e.g., Zwitserlood 2012), while others do not (Morgan and Woll 2007).

- Handling classifiers, which denote an object through depicting the handling or manipulation of the object in question, e.g., holding a mobile phone, or turning a key. These often still provide some information about the size and/or form of the object, although indirectly.

Classifiers are often discussed as a freer class of items in a sign language relative to lexical signs, in that some (not all) featural specifications of the same classifier may vary across usages based on the semantic properties of the specific referent. The movement features for an entity classifier within a classifier construction depicting a person walking may depend on their style or speed of walking, just as the type of tree depicted may determine specifics of the chosen handshape. However, whilst a signer has relatively more articulatory choices at their behest when using classifiers, it is not completely unconstrained. They must become conventionalised within a given language. Classifiers for the same group of referents vary crosslinguistically and are not always transparent despite their tendency to take advantage of iconic relations—compare the BSL vehicle classifier handshape]2 to that of ASL  .

.

.

.This crosslinguistic variation might in part be due to the iconic capacity of handshape being more varied than that of movement and location. There are often many aspects of an entity available for iconic depiction, and choices are influenced by various factors including conceptual salience (Tkachman et al. 2020), i.e., which visual aspect of the referent may be most salient such as the beak of a chicken as opposed to its feet. The choices for movement and location are not so broad, if one wants to depict iconically. In reality, referents are only ‘specified’ (to use a phonological metaphor) for one location at any given time, relative to other potential referents. The same may be said about orientation, and to a lesser extent, movement3. It cannot be said that an entity is specified only for one shape, however. A human being or a car could be deconstructed into many shapes, including but not limited to their overall shape. The overall shape of a referent is merely one representational choice available out of many in constructing an entity classifier. This variety of choice can be observed in experimental contexts. Schembri et al. (2005) found that when depicting the same referents, the handshapes of classifiers used by signers of unrelated sign languages varied much more than their movement or location specifications. In short, handshapes for the same referent vary widely between languages. We turn next to what may influence system-wide choices in handshape in languages, particularly those of different ages and stages of conventionalisation.

1.1.2. The Phonology of Classifiers

Such variety of possibility in classifier handshape may serve as one motivation to stray further away from iconicity. As users of any communicative system mediated through anatomy, signers and speakers are subject to biological principles of energy conservation and a temptation towards the path of least resistance. It is known that signs become less iconic over time (Frishberg 1975), and that such phonological reorganisation can be motivated by ease of articulation. Eccarius (2008) notes the older form of the airplane classifier handshape in HKSL is the highly marked  . Over time, young signers are replacing this handshape with

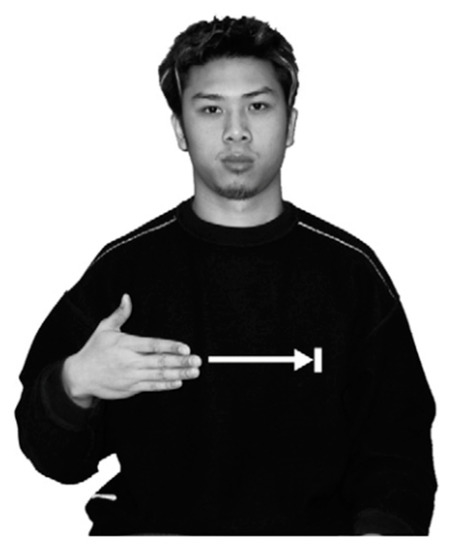

. Over time, young signers are replacing this handshape with  , wherein the index finger is extended rather than the middle. What this newer variant may lose in iconicity, it gains in ease. Only the thumb, index, and pinky fingers are controlled by muscles that allow them to extend independently with no adjacent digit to support them (Ann 2006, p. 94). This pull towards articulatorily ease appears strong enough to transcend the lone domain of handshape. The movement features of VIDEOTAPE-RECORDER in ASL have shifted from being asymmetrical—depicting the way in which the reels really move—to being symmetrical (Figure 3). The motivation from articulatory ease is clear. Human physiology is marked by bilateral symmetry, and as such movements that are symmetrical from the midline of the body can be specified for only one path of movement, rather than the two that asymmetrical movements require. Empirically, studies on symmetry in gesture (in hearing non-sign language-learning infants) and sign (in deaf sign language-learning infants) in young children support the idea that two-handed symmetrical movement is articulatorily easier than two-handed asymmetrical movement (Fagard 1994; Cheek et al. 2001; Pettenati et al. 2010). We take this as strong evidence of their relative ease, analogously to how factors such as infant substitutions and error shape conclusions about the relative difficulty of sounds in spoken language.

, wherein the index finger is extended rather than the middle. What this newer variant may lose in iconicity, it gains in ease. Only the thumb, index, and pinky fingers are controlled by muscles that allow them to extend independently with no adjacent digit to support them (Ann 2006, p. 94). This pull towards articulatorily ease appears strong enough to transcend the lone domain of handshape. The movement features of VIDEOTAPE-RECORDER in ASL have shifted from being asymmetrical—depicting the way in which the reels really move—to being symmetrical (Figure 3). The motivation from articulatory ease is clear. Human physiology is marked by bilateral symmetry, and as such movements that are symmetrical from the midline of the body can be specified for only one path of movement, rather than the two that asymmetrical movements require. Empirically, studies on symmetry in gesture (in hearing non-sign language-learning infants) and sign (in deaf sign language-learning infants) in young children support the idea that two-handed symmetrical movement is articulatorily easier than two-handed asymmetrical movement (Fagard 1994; Cheek et al. 2001; Pettenati et al. 2010). We take this as strong evidence of their relative ease, analogously to how factors such as infant substitutions and error shape conclusions about the relative difficulty of sounds in spoken language.

. Over time, young signers are replacing this handshape with

. Over time, young signers are replacing this handshape with  , wherein the index finger is extended rather than the middle. What this newer variant may lose in iconicity, it gains in ease. Only the thumb, index, and pinky fingers are controlled by muscles that allow them to extend independently with no adjacent digit to support them (Ann 2006, p. 94). This pull towards articulatorily ease appears strong enough to transcend the lone domain of handshape. The movement features of VIDEOTAPE-RECORDER in ASL have shifted from being asymmetrical—depicting the way in which the reels really move—to being symmetrical (Figure 3). The motivation from articulatory ease is clear. Human physiology is marked by bilateral symmetry, and as such movements that are symmetrical from the midline of the body can be specified for only one path of movement, rather than the two that asymmetrical movements require. Empirically, studies on symmetry in gesture (in hearing non-sign language-learning infants) and sign (in deaf sign language-learning infants) in young children support the idea that two-handed symmetrical movement is articulatorily easier than two-handed asymmetrical movement (Fagard 1994; Cheek et al. 2001; Pettenati et al. 2010). We take this as strong evidence of their relative ease, analogously to how factors such as infant substitutions and error shape conclusions about the relative difficulty of sounds in spoken language.

, wherein the index finger is extended rather than the middle. What this newer variant may lose in iconicity, it gains in ease. Only the thumb, index, and pinky fingers are controlled by muscles that allow them to extend independently with no adjacent digit to support them (Ann 2006, p. 94). This pull towards articulatorily ease appears strong enough to transcend the lone domain of handshape. The movement features of VIDEOTAPE-RECORDER in ASL have shifted from being asymmetrical—depicting the way in which the reels really move—to being symmetrical (Figure 3). The motivation from articulatory ease is clear. Human physiology is marked by bilateral symmetry, and as such movements that are symmetrical from the midline of the body can be specified for only one path of movement, rather than the two that asymmetrical movements require. Empirically, studies on symmetry in gesture (in hearing non-sign language-learning infants) and sign (in deaf sign language-learning infants) in young children support the idea that two-handed symmetrical movement is articulatorily easier than two-handed asymmetrical movement (Fagard 1994; Cheek et al. 2001; Pettenati et al. 2010). We take this as strong evidence of their relative ease, analogously to how factors such as infant substitutions and error shape conclusions about the relative difficulty of sounds in spoken language.

Figure 3.

The evolution of ASL VIDEOTAPE-RECORDER. Adapted from Klima and Bellugi (1979). Reprinted with permission from Klima and Bellugi. 1979 Harvard University Press.

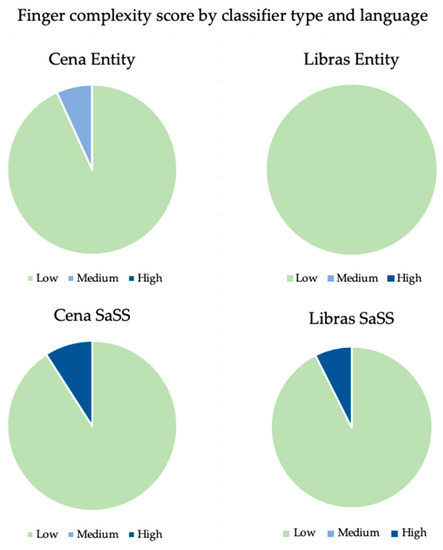

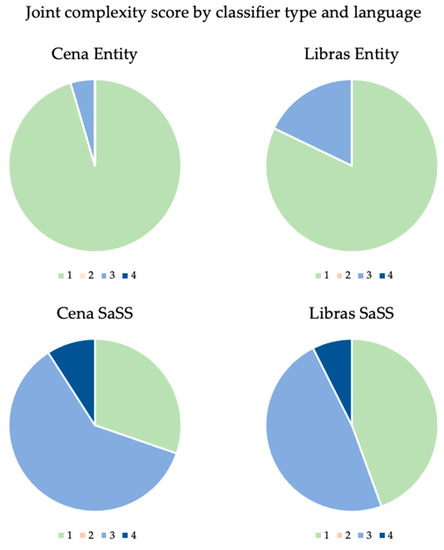

In short, the balance of the trade-off between faithfulness to iconicity and pressures of phonology may shift over time. Such an idea is also supported by more recent work. Brentari et al. (2012) present evidence that the phonological features of classifiers show a predictable distribution in terms of complexity. Naturally, a quantifiable measure of complexity is needed for such a claim. The authors compare two types of complexity—finger complexity and joint complexity—and define them as follows. Finger complexity is concerned with which fingers are selected for a given handshape, as articulatory difficulty varies in part because of how different muscle groups support the extension of the digits of the hand. For example, it is less strenuous for the middle, ring, and pinky fingers to all share the specification of flexion or extension in a handshape (see Ann 2006 for an anatomical explanation of why). Brentari and colleagues describe the different criteria one can use to arrive at a notion of low finger complexity in handshapes: early acquisition, crosslinguistic frequency, and representational simplicity—in this case under the prosodic model (Brentari 1998)4. These criteria all overlap to capture three selected finger groups of low complexity (all, index, and thumb) shown in Table 1. Handshapes with medium complexity are those that have a single non-radial finger extended, i.e., the middle, ring, or pinky finger. Additionally, the medium complexity category captures handshapes with two selected fingers. Representational complexity determines this criterion; medium finger complexity handshapes differ from low complexity handshape by one additional feature specification. The prosodic model utilises one of the central ideas of dependency phonology5: features dominate over other features to yield possible contrasts. This is analogous to representations of vowel systems wherein the place feature [high] alone might be realised as [i], but if [high] dominates over [low] this results in [ɪ]. For a handshape where the index and middle fingers are extended, for selected fingers [one] dominates [all]. Similarly, different place features combine in dominance relations to yield handshapes such as the ring finger alone being extended. As such feature interactions require two features, this additional feature forms the criteria for medium complexity. High complexity captures all other possible selected finger groups that differ in the type and number of additional feature configurations they need.

Table 1.

Handshapes demonstrating finger complexity scores according to Brentari et al. (2012).

Whilst joint complexity was not the authors’ focus, they define it as follows. Fully open and fully closed handshapes are given the lowest score of 1, in which the selected fingers are fully extended, or all fingers are fully closed respectively. Flat and spread handshapes receive a higher score of 2. Flat handshapes are formed by bending the finger(s) at the base joint while the other finger joints remain extended, and spread handshapes are any in which the extended fingers are spread apart from one another. Curved and bent handshapes receive a higher score still (3), wherein all the selected finger joints are flexed to a greater (bent) or lesser (curved) degree. The category of highest joint complexity, 4, is reserved for stacked (in which each selected finger is increasingly flexed) and crossed (when selected fingers are crossed) handshapes. Accompanying examples of all groups can be found in Table 2. These complexity scores are again based on a notion of representational complexity under the Prosodic Model (Brentari 1998), but the resulting stratification accurately predicts patterns we would expect given such categorisation (Brentari et al. 2016). In acquisition, the handshapes that are the earliest acquired by ASL- (Boyes Braem 1990) and BSL-learning children (Morgan et al. 2007) are of low joint complexity. Those that are of high joint complexity, conversely, are among the latest acquired and among the most infrequent crosslinguistically (Rozelle 2003). However, whilst all handshapes of low complexity may be those that are crosslinguistically frequent and earliest acquired, the reverse does not necessarily hold. That is, handshapes that may be frequent or easily acquired may not always receive scores of low complexity. One such exception is the curved  handshape6, which is considered unmarked (Battison 1978) and is frequent crosslinguistically in classifiers (Zwitserlood 2012). Its relative frequency in classifiers across languages is likely at least partially grounded in its ubiquity as a manual configuration for handling objects. As the model of Brentari et al. is motivated primarily by representational complexity, such a model will overlook influences of this type.

handshape6, which is considered unmarked (Battison 1978) and is frequent crosslinguistically in classifiers (Zwitserlood 2012). Its relative frequency in classifiers across languages is likely at least partially grounded in its ubiquity as a manual configuration for handling objects. As the model of Brentari et al. is motivated primarily by representational complexity, such a model will overlook influences of this type.

handshape6, which is considered unmarked (Battison 1978) and is frequent crosslinguistically in classifiers (Zwitserlood 2012). Its relative frequency in classifiers across languages is likely at least partially grounded in its ubiquity as a manual configuration for handling objects. As the model of Brentari et al. is motivated primarily by representational complexity, such a model will overlook influences of this type.

handshape6, which is considered unmarked (Battison 1978) and is frequent crosslinguistically in classifiers (Zwitserlood 2012). Its relative frequency in classifiers across languages is likely at least partially grounded in its ubiquity as a manual configuration for handling objects. As the model of Brentari et al. is motivated primarily by representational complexity, such a model will overlook influences of this type.

Table 2.

Handshapes demonstrating joint complexity scores according to Brentari et al. (2012).

Moving away from notions of complexity defined by linguistic criteria, Brentari et al.’s model generally overlaps with a model of articulatory ease based on the anatomy and physiology of the hand proposed by Ann (2006), with some minor differences7. Whilst keeping in mind that representational complexity is not automatically the same as articulatory difficulty, it is pertinent to determine to what extent a phonological measure of complexity overlaps with purely motoric articulatory difficulty. In this case, this model of representational complexity does largely overlap with conceptions of articulatory difficulty based on acquisition, crosslinguistic distribution, and anatomy.

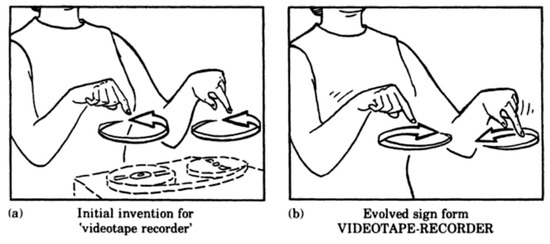

Considering the findings of Eccarius (2008) and Brentari and Eccarius (2010), that handshapes in entity classifiers (or object classifiers as they call them) have greater finger complexity and handshapes in handling classifiers have greater joint complexity across unrelated sign languages, Brentari et al. (2012) compare hearing gesturers, homesigners, and ASL and Italian Sign Language signers to shed light on whether this pattern is one imposed by some aspect of the linguistic system, or a general tendency in codification shared by signers and non-signers alike, based on iconic properties available to all. The authors found the former: gesturers demonstrated the inverse of the results from the crosslinguistic studies (i.e., greater joint complexity in object handshapes and greater finger complexity in handling handshapes). The homesigners’ results mirrored those of signers but with less polarised differences, and the signers in the study replicated findings from previous research. In other words, there is a unidirectional pattern of change in phonological complexity through gesturers, homesigners, and signers respectively. Finger complexity in entity classifier handshapes increases, as does joint complexity in handling classifier handshapes. Differences in finger complexity distribution across signers, homesigners, and gesturers found by Brentari et al. (2012) can be seen in Figure 4, in which the asterisk denotes a statistically significant difference. Taken together with examples from Frishberg (1975) and Eccarius (2008), this seems to suggest that even in a realm as iconic as classifiers, we still observe that something like handshape complexity is not distributed equally across classifier types and is subject to, at least in part, predictable phonological organisation. We take this as our starting point for the current study.

Figure 4.

Finger complexity in object8 and handling classifier handshapes across groups. Adapted from Brentari et al. (2012). Reprinted with permission from Brentari et al. 2012 Springer Nature.

1.1.3. Manner and Path in Motion Events

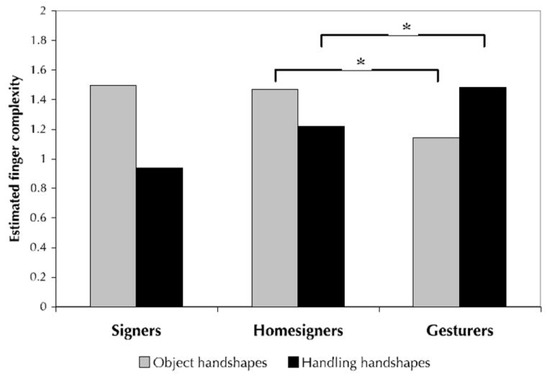

Entity classifiers allow signers to set up a referent in space and have it undergo or perform actions. As such, they are often used by signers to depict motion events. If motion occurred, there is always a start and end point between which a referent moved; this is what is referred to as path movement. There is also a manner of movement—how a referent got from A to B (such as rolling or walking). Perceptually, both these aspects of movement are perceived simultaneously and thus one might imagine that any linguistic expression of motion events would reflect this simultaneity. However, comparisons made among spoken languages demonstrate that they tend to segment a motion event into two linguistic structures, one encoding the path and another the manner (Talmy 1985). More recent research on signers and gesturers has aimed to answer the question on whether this tendency to segment and linearise is a general property of language, or an effect of modality. Visual information such as path and manner of movement can be easily ‘stacked’ in sign languages—encoded simultaneously mirroring the way it is visually experienced. Sequential encoding is of course equally possible (see Figure 5 for both methods). Nicaraguan Sign Language (NSL) offers a unique vantage point into the dynamic early stages of a developing sign language and how motion information is encoded (Senghas et al. 2004); much like hearing Spanish-speaking, non-signing gesturers, first-cohort child NSL signers tended to encode events holistically, representing the simultaneous exhibition of path and movement features as they occur in the real observed event. In second- and third-cohort child signers, significantly less simultaneous encoding was observed, and was replaced by sequential encoding at a comparable rate of frequency (Figure 6).

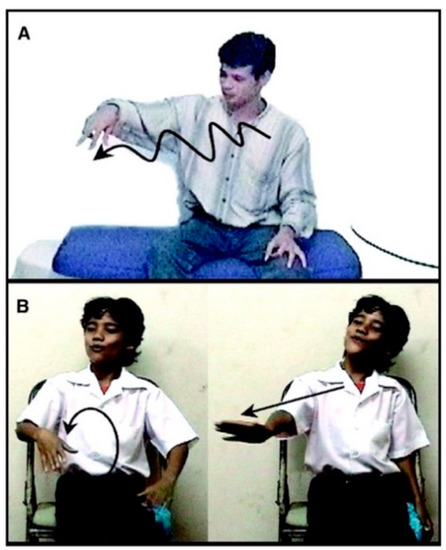

Figure 5.

(A) A gesturer encoding manner and path simultaneously; (B) a NSL signer encoding manner and path sequentially. Adapted from Senghas et al. (2004). Reprinted with permission from (Senghas et al. 2004) The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

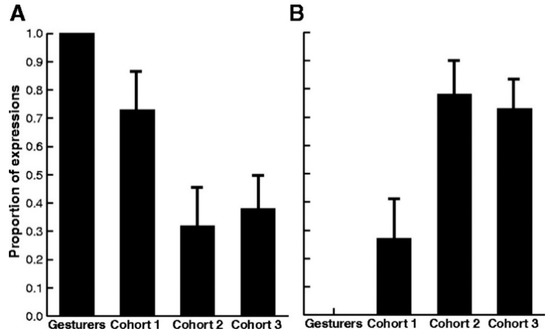

Figure 6.

Proportion of simultaneous (A) and sequential (B) movement encoding across groups in Senghas et al. (2004). Reprinted with permission from (Senghas et al. 2004) The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

However, one should not rush to conclude that there is simply a unidirectional change in a language from simultaneous encoding towards sequential encoding as a language develops over time. When tested with the same materials as the NSL signers, signers of Spanish Sign Language encoded manner and path primarily simultaneously (Senghas and Littman 2004), demonstrating the tendency of urban sign languages to depict manner and path simultaneously rather than sequentially. There are mentions, however brief, in existing literature on other conditions in which linear segmentation of movement may occur. Supalla (1990) describes two types of constraints on simultaneity of manner and path in ASL classifiers: motoric constraints, where manner and path physically cannot be depicted simultaneously, and grammatical constraints, wherein existing constraints on movement prohibit a particular combination of a verb of motion with a selected classifier9. Newport and Meier (1985), De Beuzeville (2004), and Tang et al. (2007) all report instances of sign language-learning children breaking down motion events into linear constructions, the individual parts of which sequentially encode aspects of its path or manner. Newport and Meier (1985) argue that this is motivated by articulatory ease, that children may struggle to articulate classifier handshapes (which are often marked) and the path or manner of the motion verb simultaneously. Concerning the choice between linear segmentation and simultaneous encoding of manner and path, the latter is the more iconic choice in terms of temporality. That is, manner and path are simultaneous in a motion event itself, so to encode them as such is faithful to reality. Among children acquiring sign languages, in the trade-off between iconicity and articulatory ease, ease may prevail when certain aspects of manner or path are difficult to produce simultaneously for the young signer.

What the cases of later-cohort NSL signers and children in the acquisition stage seem to suggest is that segmentation is the exception rather than the rule. The language model available to later-cohort NSL signers (who exhibit linear segmentation of motion events) was one that was undergoing rapid and multifaceted restructuring as various homesigners came together. Children in the acquisition stage are also in an atypical linguistic situation relative to other language users; they are in a transitory and temporary period when they do not yet have a full grasp of their native language. What both these cases have in common is some unique environment in terms of language input and/or acquisition stage, and both cases involve child signers. None of this applies to signers in our study. On the other hand, further investigation may suggest that these are not conditioning factors in accounting for sequential encoding of manner and path, and the preference may be also found in second and third cohorts of adult signers of emerging sign languages. The current study takes one step towards answering this question.

1.2. The Current Study

So far, we have presented evidence that classifiers are indeed an area in which the phonological domains of handshape and movement are subject to (re)organisation over time. Subsequently, we present an exploratory analysis of classifier handshape and movement in two sign languages differing in age and sociolinguistic profile. Existing work by Sandler et al. (2011) on Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language (a village sign language of Israel, henceforth ABSL) in accounting for phonetic variation details how signers of an emergent sign language aim for highly iconic holistic depictions of referents, in lieu of contrastive primitives or phoneme-like units in a phonological system. This appears to be true of other typologically similar sign languages (e.g., Hou 2016). If it is the case that classifiers are subject to pressures from articulatory ease over time, and that signers of emerging sign languages tend to aim for holistic iconic depictions, we may expect greater complexity and variation in Cena considering its youth relative to Libras, as Cena signers aim for specific and unconventionalised iconic depictions.

To test this, we compare responses to a video depicting a bottle falling from Cena and Libras signers. In the stimulus, the bottle falls without intervention from a visible human agent so it elicited mostly entity classifiers and SaSSes (our criteria for assigning a classifier each of these labels is explained in Section 2.3). We present the analysis of these types separately, to tease apart the distribution of handshapes across different types of classifiers considering there may be aspects of each type of depiction (whole entity vs. size and shape) that may influence the selection of handshapes, as we have seen happens between entity and handling handshapes. The variants will be coded for complexity following Brentari et al. (2012) and Brentari (1998) and compared across languages. We will also assess variation by way of the number of handshape variants per language and their distribution. Last, we present an analysis of how movement manner and path are encoded in descriptions of motion events considering the relevant variable of language time-depth (cf. Senghas et al. 2004). The domain of classifiers is well-suited to our aims. The high degree of iconicity often found in classifiers provides an opportunity to observe other factors that may pull sign form away from faithfulness to semantics or an iconic representation, such as articulatory ease, or the emergence of sequential encoding.

Predictions

The conventionalisation of classifier form in languages over time is a process that allows signers to rely on convention to depict referents rather than only iconic resemblance, inviting the possibility for forms to become phonologically reorganised under the pressure of articulatory ease in cases where the two are indeed opposing forces. Of course, there are other forces influencing classifier form such as semantics, but pressures of ease function within such influences (there are articulatorily more and less difficult ways of picking out the same semantic property). Given the tendency for signs—including classifiers—to submit to pressures of articulatory ease as a system increases in time-depth and becomes more conventionalised, and given the holistic depictions found in village sign languages in lieu of robust systematic phonological structure (Sandler et al. 2011; Hou 2016), we predict that iconic depiction will triumph in any trade-off against articulatory ease. Our first hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Cena classifiers will exploit handshapes of greater complexity than Libras.

Since it is unlikely that a systematic level of phonological structure has emerged in a language of such an age and sociocultural profile, and that close-knit communities can tolerate great variation (Wray and Grace 2007) at higher rates than their national counterparts (Meir and Sandler 2019) over long periods of time (Meir et al. 2012), our second hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Cena classifier handshapes will exhibit greater intersigner variation than Libras.

Last, we turn to the encoding of motion events. Whilst Cena signers have not yet been grouped into distinct cohorts by researchers, they are not homesigners; most of them grew up with an existing language model. However, this linguistic input is different to that of later-cohort NSL signers, who showed a greater preference for the linear sequencing of motion events relative to first-cohort signers. The vertical linguistic input of later-cohort signers was that of various unconnected homesigners whom the establishment of a school had brought together. Although we believe the majority of Cena signers in our study to be roughly second cohort, their language is not undergoing the intense restructuring of second-cohort NSL, or others in creolisation language contexts (though this may have been partly in play with the establishment of Libras over 150 years ago in its early development with the foundation of INES). Recall also that linear sequencing of motion events has been observed in children acquiring a sign language. As all signers in our study are well past the acquisition period, and given that Cena does not share its context of emergence with NSL and the subsequent type of restructing that follows, we predict Cena signers will prefer simultaneous encoding of manner and path. We also predict Libras signers will prefer this strategy, in line with data from signers of Spanish Sign Language. Our final hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Both Cena and Libras signers will exhibit a preference for simultaneous encoding of motion events.

1.3. Language Profiles

1.3.1. Libras

Libras—an abbreviation of its Portuguese name, Língua Brasileira de Sinais—is the official national sign language of Brazil, used in (but not limited to) institutions and urban centres across Brazil. Its establishment was associated with the foundation of the National Institute of Deaf Education (INES) in Rio de Janeiro in 1857. Since one of the original teachers at the institute was French, modern Libras has evolved from a mixture of French Sign Language and existing signs in use in the region (Xavier and Agrella 2015). In 2002, Libras was legally recognised as the language of many Brazilian deaf communities, reaffirming its cultural and linguistic importance as a natural language10. The legal recognition of Libras under the ‘Libras Law’ (as Federal Law 10.436 is known) and a resulting decree (5.626) has manifested basic deaf rights in Brazil, including rights to interpreters in official settings and the translation of official documents. In the wake of such legal recognition, Silva (2021) suggests we need to look anew at the sign languages of Brazil used outside of urban centres. Outside of legal protections and benefits, we have seen that their documentation paves the way for a richer and broader understanding of (sign) language typology (de Vos and Pfau 2015), phonology (see Sandler et al. 2011 for the emergence of), and syntax (Sandler et al. 2005 for word order; Meir 2010; Padden et al. 2010; Ergin et al. 2018 for argument structure). We compare Cena to Libras in the current study to control as many orthogonal variables as possible. Primarily, the comparison ensures that the repertoires of ambient gestures of the surrounding culture are closely matched. This is a known and significant influence on sign languages, as they absorb and reorganise gestures that are culturally specific even within the realms of classifiers (Nyst 2019). We know of at least one such borrowing in Cena, where the sign PAST/A-LONG-TIME is identical in form to a common Brazilian finger-snapping gesture relating to time passing. Therefore, although the desired comparison is primarily between a young emergent language and an urban sign language with greater time depth, we aim to minimise confounds from distinct gestural influences by comparing Cena to the most culturally similar language that otherwise meets our criteria.

1.3.2. Cena

Silva (2021, p. 107) details studies that deal with at least 21 sign languages used by deaf communities in Brazil (see Fusellier-Souza 2004; Stoianov and Nevins 2017; and Godoy 2020 for examples of linguistic investigation). However, such studies are still preliminary and in need of richer linguistic description. Among these emerging sign languages used by isolated communities far from urban centres we find Cena, literally scene, the word used to refer to what signers recount with their hands as they sign and the term that has come to be used as a name for the language in its community. Cena is a sign language in its third generation used by deaf (and many hearing) inhabitants of Várzea Queimada, a community with a population of about 900. Várzea Queimada is located in the eastern part of Piauí, a mostly landlocked state of north-eastern Brazil. Cena, like other languages of its kind, has emerged within a context of a high rate of congenital deafness and is unrelated to the national sign language of its country. It is in the PhD thesis of Everton Pereira (2013) that we find the first published mention of Cena11. From an anthropological perspective, he details the use of Cena as it interacts with aspects of daily life and society in Várzea Queimada: work, religious practices, family life, and local artisanal crafting. The majority of residents, deaf and hearing alike, subsist on agriculture, animal husbandry, local commerce, and government benefits12. In claiming that many hearing people sign, and in drawing any parallels between the work-related livelihoods of deaf and hearing inhabitants of the community, it is important to be careful to not perpetuate idealistic notions of a ‘deaf utopia’ in villages such as Várzea Queimada, as warned by Kusters (2010). She explains the risk of flattening many nuanced asymmetries between the social, economic, educational, and professional realities of deaf and hearing people in such contexts by over-emphasising the integration of deaf community members relative to Western urban contexts. In Várzea Queimada, deaf access to education has historically been subpar or non-existent, and the community is not immune to negative attitudes towards deafness from within their ranks. Anthropological and linguistic work on Cena is undoubtedly in its infancy, but suffice it to say for now that the gap of social and economic stratification between deaf and hearing inhabitants of Várzea Queimada is far smaller than that of urban centres around Brazil, which is of course in no small part likely due to the upper limits of such stratification within the confines of the village.

There are 34 known deaf inhabitants as of 202113, most of whom use Cena as their primary language although there is variation in the exposure to and use of Libras, particularly with younger signers. Most deaf inhabitants are clustered in three villages, each a few kilometres apart. The first deaf woman in the community was born in 1949, and soon after another six deaf children were born into a different family. Cena is not a homesign system, but we hypothesise that like many similar languages, it likely started as one. As is common with sign languages of this sociocultural context (de Vos and Pfau 2015), an unknown number of hearing people in the community sign to varying degrees of competency. Many deaf adults have hearing children—known as CODAs (children of deaf adults)—who are proficient signers, and some hearing members of deaf individuals’ families are competent signers. At the time of publication, the youngest deaf signer is 15, with no other known deaf children born in the community since. There is some use of Libras among younger signers since many temporarily attended schools in the community, where they had weekly classes in Libras. Younger signers also have access to the internet and numerous social networks to varying degrees, and signers of a variety of ages use lexical borrowings from Libras. Despite the increased and perhaps increasing presence of Libras in the community through education and the internet, age remains a determining factor; older signers do not, and have not historically, attended school and thus use of Libras among them is often minimal.

Whilst Pereira’s thesis discusses matters of deaf social life and integration in detail, Almeida-Silva and Nevins (2020) provide the first linguistic overview of the language. Their data is comprised of 330 signs including nouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, and functional items. Pronominal markers rather expectedly use self-anchored pointing to mark first person, and pointing using real-world location to mark the second or third person of any present referent. In all existing data including that in the current study, no absent third-person pronouns have been observed. The authors also present evidence of adverbial modification (shown in Figure 7) in the use of facial expression and body movement to intensify manual signs, much like uses of similar non-manual features for intensification purposes in other urban sign languages, such as the ‘ee’ mouth gesture in BSL (Sutton-Spence and Woll 1999) and Auslan (Johnston and Schembri 2007), and the furrowed brows and hunching of the torso used in intensification in Libras (Xavier 2017). Concerning word order, there appears to be little overall convergence. Yet ‘overall’ may be the operative word in this case, as work on Central Taurus Sign Language (Ergin et al. 2018) and ABSL (Meir 2010) suggests consistency of word order in emerging sign languages can be dependent on syntactical properties of the verb events in question, as well as on signing cohort. Almeida-Silva and Nevins (2020) encountered various minimal pairs such as the example shown in Figure 8, where one should note that the difference of left- and right-handedness between the signers is irrelevant to lexical contrast. As expected from languages that have emerged among low or unreliable rates of literacy, there is no manual alphabet nor any attested native alphabetised signs present thus far, though several signers know the Libras manual alphabet to varying extents—it is not uncommon for signers to use it for their own names or the names of others. Although there exist lexical borrowings from Libras, both the findings of Almeida-Silva and Nevins (2020) and data in the current study provide evidence for a vocabulary largely comprised of local Cena signs, including compounds unattested in Libras. Based on our observations over many field visits, signers are predominantly monolingual. This description is corroborated by self-reports from signers (Almeida-Silva, forthcoming), and by interviews with those who worked as teachers with the deaf members of the community, one going so far as to say Cena signers “reject” Libras (Franco 2022, p. 7).

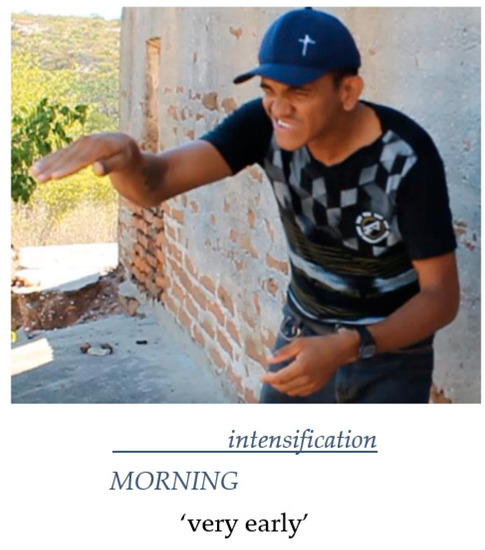

Figure 7.

A case of modification utilising the ‘ee’ mouth shape and body posture.

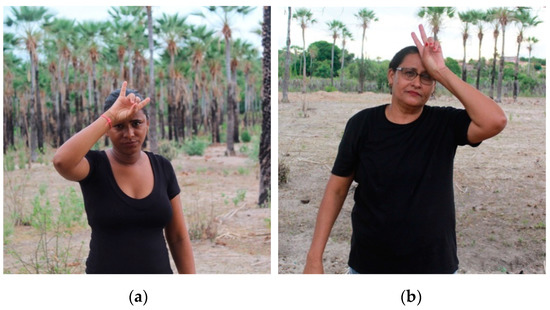

Figure 8.

A minimal pair in Cena differing in handshape: (a) GOAT; (b) TO BETRAY.

This preliminary linguistic sketch of Cena found considerable robustness of various domains of the lexicon, notably food, animals, and religious terminology (which details the numerous saints and religious festivals observed by the mostly Catholic inhabitants of the community). Despite this, variation prevails. It is primarily along inter-familial and inter-generational lines where lexical variation is found, but phonetic variation is widespread among signers. This comes as no surprise (cf. Israel and Sandler 2011 for ABSL). It is known that for language in general, degrees of social intimacy and shared communal knowledge has a bearing on the resulting types of linguistic structures (Wray and Grace 2007). The lives of the inhabitants of Várzea Queimada are highly intertwined. People spend a great deal of daily time in each other’s company doing domestic or farm work. From this repeated interaction sprouts a high degree of knowledge and intimacy concerning the lives and families of others, shared reference points, events and practices of cultural importance, and a knowledge of the surrounding area. The communication patterns of Várzea Queimada would fall squarely into what Wray and Grace (2007) and Thurston (1989) call esoteric, inward-facing language use on topics of mutual familiarity among those who are known to each other. This shared knowledge and relative homogeneity is what enables languages in such communities to tolerate high rates of variation (Meir and Sandler 2019), and is primarily what motivates our Hypothesis 2, predicting greater variation in Cena.

1.3.3. Typological Considerations

Considering the above sociocultural and linguistic outline of Cena, we turn briefly to the issue of language typology. Typological classification is a useful exercise as it enables us to compare phenomena across languages of the same type. Of course, type can refer to many aspects of linguistic structure—tonal languages are a type, as well as those with or without agglutinative morphology. Given what is known about the effects of sociocultural and geographical context on linguistic structure in young sign languages, the existing literature has commonly sought to categorise them along these lines. Broadly speaking, two main categories appear in the literature following the distinction first made by Meir et al. (2010): deaf community sign languages, and what we will term village sign languages (although there is more debate around the labels for sign languages of this general kind). Deaf community sign languages are the result of a group of deaf people of varied backgrounds coming together for some (often institutional) purpose, and often coincide with the establishment of a deaf school. NSL is one often-cited example of a deaf community sign language (see Senghas 1995 and Kegl et al. 1999 for early work) as the establishment of the school that galvanised its development was relatively recent. The historical development of several national sign languages including ASL also meets the criteria for this label, though these are often referred to as urban sign languages.

It should already be clear that Cena is not a deaf community sign language. As it has emerged among its users of the same background within the community in which it is used, Cena does not meet this description. Concerning the second type, there are many overlapping terms, including village sign language (Zeshan 2011), shared sign language (Nyst 2012), indigenous sign language (Woodward 2000), and micro-community sign language (Schembri 2010), which generally overlap in their criteria of a high rate of congenital deafness and a geographically rural context. The label shared sign language foregrounds the tendency for a large number of hearing people in such communities to sign, with varying degrees of fluency and regularity. Similarly, the name indigenous sign language aims to highlight the origin of such languages as the same region or country as that in which they are used. All such features are true of Cena, meaning perhaps it is a question of what we to wish to foreground. For the current study, we follow Almeida-Silva and Nevins (2020) in using the label emerging sign language with the caveat that Cena does broadly fit the typical profile of a village sign language, since it is primarily the difference of time depth that is relevant for our aims. That is, we wish to compare Cena with a language in the same national and therefore to some degree cultural context, but one that has a stable and conventionalised lexicon and linguistic structure.

Whilst Almeida and Nevins provide an invaluable preliminary overview of the language, there is to date no mention of classifiers in any work on Cena. With the exception of Brentari et al. (2012)14, there is little in the existing literature on classifiers in young or emerging sign languages. Although not an emergent language, in her description of Adamorobe Sign Language (a village sign language used in Ghana), Nyst (2007) details the gestural and linguistic resources signers exploit for depiction of size and shape. Nyst’s striking finding that Adamorobe Sign Language lacks entity classifiers highlights the importance of village sign language data in investigations of language typology and in questioning linguistic universals. Similarly, de Vos (2012) describes some classifier constructions in Kata Kolok—another non-emergent village sign language (she posits that Kata Kolok is in its fifth generation) used on Bali, Indonesia. De Vos finds that entity classifiers in Kata Kolok exploit a more restricted set of handshapes than urban sign languages; instead of handshape, entity classifiers in Kata Kolok are primarily defined by different features of movement or orientation (cf. de Vos 2012, p. 101; Marsaja 2008). Again, her findings demonstrate that village sign languages can exhibit typologically unique or unusual properties in the realm of classifiers and the distribution of the features that comprise them15. The current study contributes another such investigation into classifiers in a young language, and the distribution of some elements that comprise them. It also provides the first English-language work on Cena, and the first comparative study of Cena with any other language.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The participants consisted of 19 deaf, predominantly monolingual Cena signers aged 13–5916 who all live in or around Várzea Queimada, and 19 deaf adult native Libras signers based in Rio de Janeiro. Cena signers generally do not have fluency in written Portuguese, and many are not fully literate. The Libras participants in our study all have a strong grasp of written Portuguese as it forms a part of their daily lives.

2.2. Materials and Task

The current study used the Haifa Clips stimuli set, designed by Sandler et al. (2005), to elicit recounts of short events from participants. The task consisted of 30 short (1–3 s) video clips depicting a variety of intransitive, transitive, and ditransitive actions, such as a ball rolling, a woman looking at a man, and a man throwing a ball to a girl. Participants were asked to relay each event to an interlocutor, another deaf signer and native user of the language in question. Participants then later functioned as interlocutors for following participants. Although many hearing individuals can sign to varying degrees of competency within the community where Cena is used, we chose to limit participants to only deaf monolingual signers to avoid any potential effects of linguistic accommodation between deaf and non-native or non-fluent hearing signers. This also ensures the utterances most closely mirror language used in its natural form—in a communicative context with comprehension as a desired target. To maintain consistency across the two groups, all Libras signers in the study were also deaf native signers.

Once a participant had relayed the event to the interlocutor, the interlocutor chose the corresponding event from three options depicted in images. All response options were still images—no part of the form relied on written language. An example page of the interlocutor’s task is shown in Figure 9. Usually, the options differed in one argument of the verb and/or the verb itself. For example, for the stimulus with a rolling ball, the events depicted in the three choices are a ball falling, a bottle rolling, or a ball rolling. Once the interlocutor made a choice, this response was recorded as the first attempt. If correct, the researchers showed the following clip. If the interlocutor did not understand or chose incorrectly, the participant was prompted to explain the clip again. Participants were allowed as many attempts as needed to relay the event successfully. If none of these were successful, the attempt was marked incorrect and we played the next clip. The data for both languages was glossed by two fluent hearing Libras signers who have exposure to and knowledge of Cena through fieldwork. In light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and lack of internet connection in Várzea Queimada, it was unfeasible to have any native Cena signer or our bimodal bilingual consultant in the community involved in the glossing process.

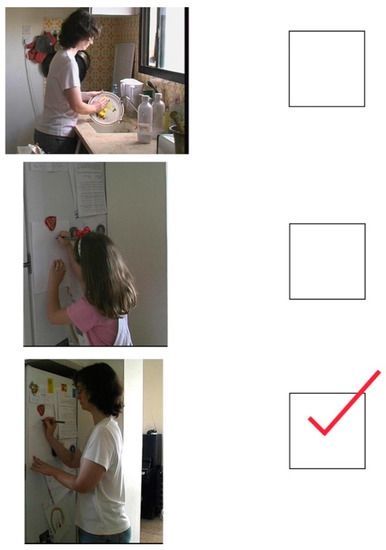

Figure 9.

Multiple choice options for the stimulus ‘woman writes on refrigerator’.

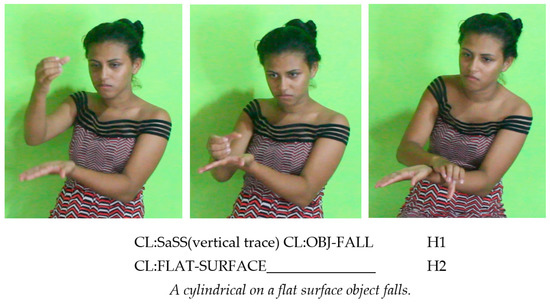

2.3. Analysis

In our investigation of classifier handshapes, we analyse responses to one stimulus clip of a bottle falling (shown in Figure 10). Finding a target item in our data set that consistenly elicited classifiers from a high number of signers was difficult, a problem made more obstructive by the small number of possible Cena participants. The bottle clip most consistently elicited use of classifiers, meaning that we had usable responses from all but one participant. We coded handshapes used to depict the referent when it is involved in some verb event as entity classifiers. Any classifiers that only depicted the extension of the object were coded as SaSSes. These could be static (perhaps depicting the height of the object) or have movement tracing its shape. For a classifier with movement to be classified as a SaSS, the movement must only depict the dimensions of the object, and no verb event. All tokens of a variable of interest in a participant’s response were coded. For example, if a participant used two entity classifiers with different handshapes to represent the bottle (perhaps one as the bottle wobbled and one as it fell), both were coded separately and used in the analysis.

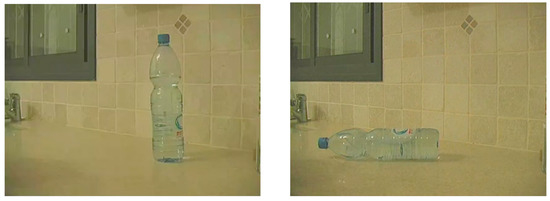

Figure 10.

Still images from the stimulus video depicting a bottle falling.

In the analysis of movement, we looked at five of the Haifa clips: a ball bouncing, a ball rolling, a girl running in a circle, a woman walking, and a woman running. We assigned one possible value out of two for movement encoding: simultaneous in cases where path and manner were encoded in the same classifier construction, sequential when a verb event was split into two signs within a phrase, one providing the manner and the other the path. If a participant provided both a simultaneous and a sequential depiction of a verb event in their response, both were coded. In some responses, signers provided both a simultaneous encoding and another additional sign encoding manner or path only. For such responses the simultaneous construction was recorded, and the additional sign excluded from the analysis. Responses that only included manner or path were also excluded.

3. Results

3.1. Accuracy

We saw similar rates of response accuracy from interlocutors across both groups, with both Cena and Libras interlocutors identifying the correct target clip in 91% of cases. The similarity in these figures serves as a confirmation that the productions in response to the task were highly successful from a communicative standpoint. Correct comprehension tended to fail in cases of reversible transitive (such as woman looks at man) or ditransitive (man throws ball to girl) events or in non-agentive intransitive events (ball rolls). In transitive and ditransitive cases of communication breakdown, it was usually due to a need to disambiguate who was the subject and who was the object. We imagine that incorrect comprehension of non-agentive intransitive events may be because telling a friend or family member ‘a ball rolled’ with no additional information or context is a strange communicative interaction perhaps with the potential to confuse.

3.2. Handshape

First, we present results for the analysis of classifier handshapes. As a reminder, we coded handshapes that were used to depict that the referent in some verb event were coded as entity classifier handshapes. Handshapes used only in depicting the extension of the object (in other words, not in a verb event) were coded as size and shape specifier handshapes. We recorded 91 tokens of some type of classifier depicting the bottle from Cena signers, with at least one from every participant. Fourteen of these were handling classifiers used in a construction depicting the act of opening a bottle to specify the object; as we believe this is in the process of becoming a conventionalised lexical sign for bottle, we exclude this as a classifier variant. This leaves 77 tokens: 44 entity classifier handshapes used in verb events and 33 SaSS handshapes used only to depict the extension of the bottle. We observed five variants of entity classifier handshapes (Table 3) and four SaSS handshapes (Table 4) in the Cena data, displayed below with number of tokens and frequency, as well as the number of participants who used the variant.

Table 3.

Cena entity classifier handshapes for the bottle stimulus.

Table 4.

Cena SaSS classifier handshapes for the bottle stimulus.

For the Libras signers, we recorded 56 tokens of some classifier depicting the bottle, with at least one from every participant. In this case, the breakdown was 28 entity classifier handshape tokens used in some verb event and 27 SaSS handshape tokens used only to depict the extension of the referent. The 3 attested entity classifier handshape variants are shown in Table 5, and the 4 SaSS variants in Table 6.

Table 5.

Libras entity classifier handshapes for the bottle stimulus.

Table 6.

Libras SaSS classifier handshapes for the bottle stimulus.

Quantitively, we find more handshape variants in entity classifiers in Cena than in Libras. All handshapes used in entity classifiers in Libras form a subset of those used in the same context in Cena. Four handshape variants were attested in SaSSes in both Cena and Libras, with three of the four handshapes being the same across the two languages. The least frequent handshape in each varied only in its degree of openess, the thumb-opposed  handshape appearing in Cena entity classifiers, and the slightly open version

handshape appearing in Cena entity classifiers, and the slightly open version  in Libras entity classifiers. At a glance, the results seem to support our prediction for Hypothesis 2 (that of greater intersigner variation in Cena) when considering entity classifiers, since more handshape variants were attested in Cena than Libras. For size and shape specifier handshapes, our prediction was not borne out as the number of handshapes attested across the languages was the same. An evaluation of Hypothesis 1 (that of greater handshape complexity in Cena classifier handshapes) requires assigning complexity scores and determining whether there is a statistically significant difference in the distribution of scores across the two languages, which follows in Section 4.1.

in Libras entity classifiers. At a glance, the results seem to support our prediction for Hypothesis 2 (that of greater intersigner variation in Cena) when considering entity classifiers, since more handshape variants were attested in Cena than Libras. For size and shape specifier handshapes, our prediction was not borne out as the number of handshapes attested across the languages was the same. An evaluation of Hypothesis 1 (that of greater handshape complexity in Cena classifier handshapes) requires assigning complexity scores and determining whether there is a statistically significant difference in the distribution of scores across the two languages, which follows in Section 4.1.

handshape appearing in Cena entity classifiers, and the slightly open version

handshape appearing in Cena entity classifiers, and the slightly open version  in Libras entity classifiers. At a glance, the results seem to support our prediction for Hypothesis 2 (that of greater intersigner variation in Cena) when considering entity classifiers, since more handshape variants were attested in Cena than Libras. For size and shape specifier handshapes, our prediction was not borne out as the number of handshapes attested across the languages was the same. An evaluation of Hypothesis 1 (that of greater handshape complexity in Cena classifier handshapes) requires assigning complexity scores and determining whether there is a statistically significant difference in the distribution of scores across the two languages, which follows in Section 4.1.

in Libras entity classifiers. At a glance, the results seem to support our prediction for Hypothesis 2 (that of greater intersigner variation in Cena) when considering entity classifiers, since more handshape variants were attested in Cena than Libras. For size and shape specifier handshapes, our prediction was not borne out as the number of handshapes attested across the languages was the same. An evaluation of Hypothesis 1 (that of greater handshape complexity in Cena classifier handshapes) requires assigning complexity scores and determining whether there is a statistically significant difference in the distribution of scores across the two languages, which follows in Section 4.1.3.3. Movement

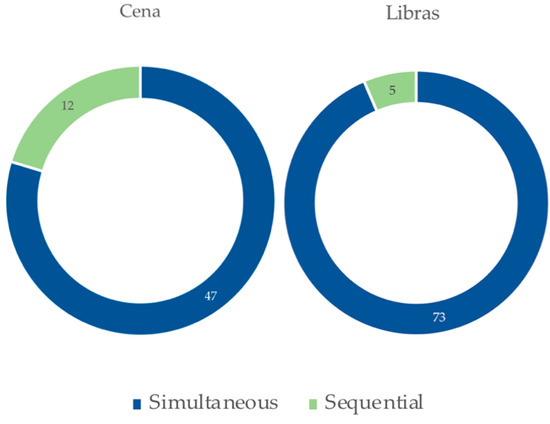

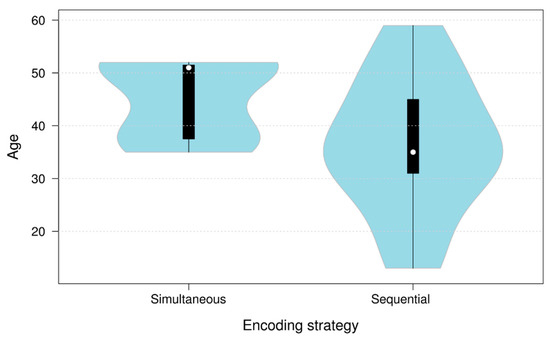

Next, we turn to movement feature encoding, where we predicted both languages to show a preference for simultaneous encoding of manner and path for the reasons outlined in Section 1.1.3. Figure 11 shows the proportion of movement encoding strategies across the two groups, demonstrating that in both languages, signers overwhelmingly preferred the simultaneous strategy: 80% of Cena tokens encoded movement manner and path simultaneously, compared to 94% in Libras.

Figure 11.

Movement encoding in Cena and Libras by token frequency.

4. Discussion

4.1. Handshape

In order to find out whether the handshapes observed in the data are articulatorily easy or simple, we return to the quantification of complexity formulated by Brentari et al. (2012), which we outlined in Section 1. All handshapes attested within entity classifiers in Cena and their resulting finger and joint complexity scores are shown in Table 7, listed in descending order of frequency. The three most frequent entity handshapes have the lowest possible finger and joint complexity scores. Only the two least frequent handshapes have a finger or joint complexity score above the lowest possible value. Such a distribution upholds the general prediction of phonological markedness (Battison 1978) that there should be an inverse relationship between frequency and complexity; that is, the more complex a handshape, the less frequent we expect it to be. Conversely, we expect the most frequent handshapes to be the least complex. This prediction is borne out in the results.

Table 7.

Entity classifier handshapes in Cena with finger and joint complexity scores.

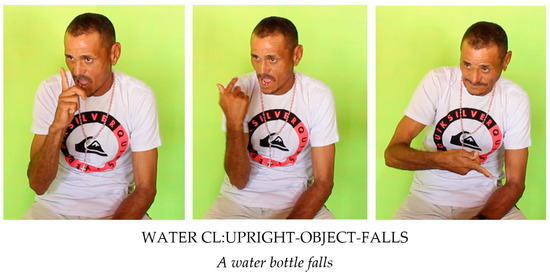

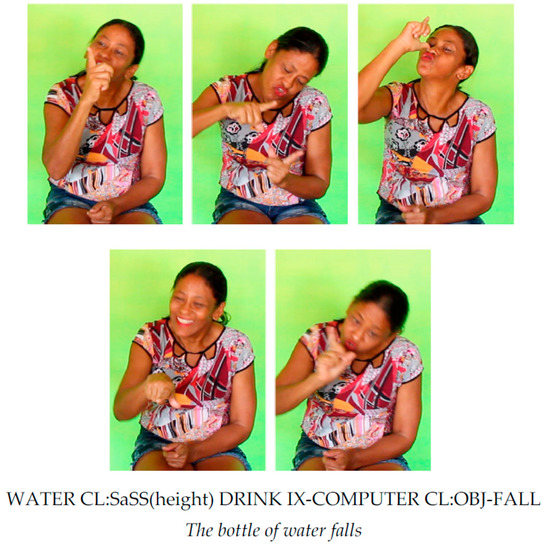

Aside from influence from a preference for ease, we can speculate further about the distribution of the data and the presence of the two least frequent handshapes. If it is the case that over time signers may choose to substitute iconic but difficult handshapes for less iconic easier ones, this alone would not explain the presence of  in the data, which is a departure from both iconicity (having no obvious semantic motivation) and finger and joint simplicity. Looking at the classifier within the phrase provides clues. The handshape was only attested (n = 3 from two different participants) in cases where the sign WATER—which is specified for the same handshape, although the thumb is not visible in the first image in the following example—preceded the classifier. An example sequence is shown in Figure 12. This appears to be a case of handshape assimilation. Similar to spoken languages where a feature of a particular sound (such as place of articulation, or voicing) may spread onto its neighbour, sublexical features of a particular sign may also spread onto adjacent signs. In this case, the handshape in WATER remains throughout the following classifier.

in the data, which is a departure from both iconicity (having no obvious semantic motivation) and finger and joint simplicity. Looking at the classifier within the phrase provides clues. The handshape was only attested (n = 3 from two different participants) in cases where the sign WATER—which is specified for the same handshape, although the thumb is not visible in the first image in the following example—preceded the classifier. An example sequence is shown in Figure 12. This appears to be a case of handshape assimilation. Similar to spoken languages where a feature of a particular sound (such as place of articulation, or voicing) may spread onto its neighbour, sublexical features of a particular sign may also spread onto adjacent signs. In this case, the handshape in WATER remains throughout the following classifier.

in the data, which is a departure from both iconicity (having no obvious semantic motivation) and finger and joint simplicity. Looking at the classifier within the phrase provides clues. The handshape was only attested (n = 3 from two different participants) in cases where the sign WATER—which is specified for the same handshape, although the thumb is not visible in the first image in the following example—preceded the classifier. An example sequence is shown in Figure 12. This appears to be a case of handshape assimilation. Similar to spoken languages where a feature of a particular sound (such as place of articulation, or voicing) may spread onto its neighbour, sublexical features of a particular sign may also spread onto adjacent signs. In this case, the handshape in WATER remains throughout the following classifier.

in the data, which is a departure from both iconicity (having no obvious semantic motivation) and finger and joint simplicity. Looking at the classifier within the phrase provides clues. The handshape was only attested (n = 3 from two different participants) in cases where the sign WATER—which is specified for the same handshape, although the thumb is not visible in the first image in the following example—preceded the classifier. An example sequence is shown in Figure 12. This appears to be a case of handshape assimilation. Similar to spoken languages where a feature of a particular sound (such as place of articulation, or voicing) may spread onto its neighbour, sublexical features of a particular sign may also spread onto adjacent signs. In this case, the handshape in WATER remains throughout the following classifier.

Figure 12.

Handshape assimilation in an entity classifier.

Similarly, the curved  handshape only appears as an entity classifier when preceded by a SaSS depicting the bottle’s cylindrical shape using the same handshape (n = 4 from one participant), as in Figure 13. Of course, a phonological explanation is not the only type possible. Such variants could be motivated by reasons of semantics17, in that the handshapes signers select may be motivated by semantic properties determined by certain experiences (or lack thereof) with objects, or certain semantic properties the signers feel to be salient in the object in the stimulus. To tease this apart, one could elicit depictions of different types of the same object, perhaps forms varying in colour, material, or intended use. This would not only foreground different semantic associations, but ideally also encourage varied lexical items preceding or following the classifiers to further investigate a hypothesis of assimilation. However, when we revisit one specific production, additional evidence for assimilation emerges. In Figure 14, a signer produces an account of the bottle falling. It begins with the sign WATER, with its

handshape only appears as an entity classifier when preceded by a SaSS depicting the bottle’s cylindrical shape using the same handshape (n = 4 from one participant), as in Figure 13. Of course, a phonological explanation is not the only type possible. Such variants could be motivated by reasons of semantics17, in that the handshapes signers select may be motivated by semantic properties determined by certain experiences (or lack thereof) with objects, or certain semantic properties the signers feel to be salient in the object in the stimulus. To tease this apart, one could elicit depictions of different types of the same object, perhaps forms varying in colour, material, or intended use. This would not only foreground different semantic associations, but ideally also encourage varied lexical items preceding or following the classifiers to further investigate a hypothesis of assimilation. However, when we revisit one specific production, additional evidence for assimilation emerges. In Figure 14, a signer produces an account of the bottle falling. It begins with the sign WATER, with its  handshape remaining over a string of several subsequent signs including a lexicalised sign, two classifiers, and an indexical point. DRINK, which appears in the middle of this string, is a conventionalised sign with the

handshape remaining over a string of several subsequent signs including a lexicalised sign, two classifiers, and an indexical point. DRINK, which appears in the middle of this string, is a conventionalised sign with the  handshape, yet the presence of the extended index finger in this production is evident. We take this as robust evidence for assimilation, and thus apply the same hypothesis to the case of the curved

handshape, yet the presence of the extended index finger in this production is evident. We take this as robust evidence for assimilation, and thus apply the same hypothesis to the case of the curved  handshape in entity classifiers, given its similar distribution only following another classifier with the same handshape. It seems that in entity classifiers that used

handshape in entity classifiers, given its similar distribution only following another classifier with the same handshape. It seems that in entity classifiers that used  and

and  , any constraints on markedness or complexity were violated by virtue of other influences from phonology—assimilation. In the case of WATER, the influence of phonology in pulling sign form away from faithfulness to semantics or iconicity is particularly clear.

, any constraints on markedness or complexity were violated by virtue of other influences from phonology—assimilation. In the case of WATER, the influence of phonology in pulling sign form away from faithfulness to semantics or iconicity is particularly clear.

handshape only appears as an entity classifier when preceded by a SaSS depicting the bottle’s cylindrical shape using the same handshape (n = 4 from one participant), as in Figure 13. Of course, a phonological explanation is not the only type possible. Such variants could be motivated by reasons of semantics17, in that the handshapes signers select may be motivated by semantic properties determined by certain experiences (or lack thereof) with objects, or certain semantic properties the signers feel to be salient in the object in the stimulus. To tease this apart, one could elicit depictions of different types of the same object, perhaps forms varying in colour, material, or intended use. This would not only foreground different semantic associations, but ideally also encourage varied lexical items preceding or following the classifiers to further investigate a hypothesis of assimilation. However, when we revisit one specific production, additional evidence for assimilation emerges. In Figure 14, a signer produces an account of the bottle falling. It begins with the sign WATER, with its

handshape only appears as an entity classifier when preceded by a SaSS depicting the bottle’s cylindrical shape using the same handshape (n = 4 from one participant), as in Figure 13. Of course, a phonological explanation is not the only type possible. Such variants could be motivated by reasons of semantics17, in that the handshapes signers select may be motivated by semantic properties determined by certain experiences (or lack thereof) with objects, or certain semantic properties the signers feel to be salient in the object in the stimulus. To tease this apart, one could elicit depictions of different types of the same object, perhaps forms varying in colour, material, or intended use. This would not only foreground different semantic associations, but ideally also encourage varied lexical items preceding or following the classifiers to further investigate a hypothesis of assimilation. However, when we revisit one specific production, additional evidence for assimilation emerges. In Figure 14, a signer produces an account of the bottle falling. It begins with the sign WATER, with its  handshape remaining over a string of several subsequent signs including a lexicalised sign, two classifiers, and an indexical point. DRINK, which appears in the middle of this string, is a conventionalised sign with the

handshape remaining over a string of several subsequent signs including a lexicalised sign, two classifiers, and an indexical point. DRINK, which appears in the middle of this string, is a conventionalised sign with the  handshape, yet the presence of the extended index finger in this production is evident. We take this as robust evidence for assimilation, and thus apply the same hypothesis to the case of the curved

handshape, yet the presence of the extended index finger in this production is evident. We take this as robust evidence for assimilation, and thus apply the same hypothesis to the case of the curved  handshape in entity classifiers, given its similar distribution only following another classifier with the same handshape. It seems that in entity classifiers that used

handshape in entity classifiers, given its similar distribution only following another classifier with the same handshape. It seems that in entity classifiers that used  and

and  , any constraints on markedness or complexity were violated by virtue of other influences from phonology—assimilation. In the case of WATER, the influence of phonology in pulling sign form away from faithfulness to semantics or iconicity is particularly clear.

, any constraints on markedness or complexity were violated by virtue of other influences from phonology—assimilation. In the case of WATER, the influence of phonology in pulling sign form away from faithfulness to semantics or iconicity is particularly clear.

Figure 13.

Handshape assimilation of  in an entity classifier.

in an entity classifier.

in an entity classifier.

in an entity classifier.

Figure 14.

Handshape assimilation of  across several signs.

across several signs.

across several signs.

across several signs.

Turning to SaSS handshapes in Cena (Table 8), we see two handshapes with high joint complexity scores, both depicting the cylindrical shape of the bottle. The more frequent curved  handshape has only high joint complexity since all the fingers are selected and act in unison. The less frequent thumb-opposed