Abstract

The current mixed-method study investigated two groups of Korean-speaking short-term sojourners in Australia. One group (students) was composed of learners enrolled in English training programs, whereas the other group (workers) was of learners in the workplace. We administered questionnaires and a semi-structured interview to examine their willingness to communicate (WTC) in English as their second language (L2) and explored the relationship between this variable and the sojourners’ amount of L2 contact and their oral fluency in English. Our quantitative analyses show that the student group showed a higher level of WTC and amount of L2 exposure than the worker group. For both groups, WTC significantly predicted sojourners’ amount of L2 exposure. However, oral fluency was found neither to be associated with WTC nor with the amount of L2 exposure. Qualitative theme-based analysis suggests that the two sojourn groups demonstrated similarities and differences in their attitudes and motivations related to WTC and unwillingness to communicate (unWTC). The students demonstrated a stronger tendency to engage in L2 interaction than the workers, aligning with their significantly higher frequency of reported L2 exposure. The workers’ attitudes were characterized by feelings of ambivalence, with co-existence of both WTC and unWTC.

1. Introduction: Willingness to Communicate

With the growing interest in individual differences in second language (L2) learning, learners’ willingness to communicate (WTC) in an L2 has drawn researchers’ attention in the last two decades. L2 WTC can be understood as “a readiness to initiate discourse with specific person(s) at a particular time, using an L2” (MacIntyre et al. 1998, p. 547). As a theoretical construct, WTC was initially defined with regard to first language (L1) communication behaviours. Furthermore, at an early stage, research on WTC focused on the unwillingness to communicate based on individual predispositions (Burgoon 1976; McCroskey and Richmond 1982). Burgoon (1976) found that several factors, including introversion, apprehension, and low communication competence prevent speakers from initiating or engaging in communication. McCroskey and Richmond (1982) also added “shyness” as a substrate of unwillingness to communicate, arguing that speakers who are reticent or timid are less likely to engage in conversations.

MacIntyre (1994) developed an earlier WTC model pertaining to L1 and L2 communication. In his L1 WTC model, perceived communicative competence is a driving force for WTC, which can be hindered by introversion (i.e., apprehension, alienation, or shyness) and anxiety. Anxiety in particular has a negative effect on WTC, which is affected by introversion and self-esteem. MacIntyre (1994) extended his L1 WTC model to the study of L2 WTC and this has largely laid the theoretical foundation for empirical studies on L2 WTC in the past two decades, where L2 WTC has been conceived as a variable that contributes to L2 learning motivation. Within this model, a high level of perceived competence and a low level of foreign language anxiety were seen as contributing to higher L2 WTC, which in turn enhance learners’ L2 learning motivation and L2 communication frequency.

In the later revised L2 WTC models, MacIntyre and colleagues (Clément et al. 2003; MacIntyre and Charos 1996; MacIntyre et al. 1998; MacIntyre et al. 2003) considered a wide range of psychological, interpersonal and situational variables that influence L2 WTC. For example, in one of the most comprehensive models of L2 WTC, MacIntyre et al. (1998) explained that variables such as interpersonal motivation (motivation to engage in interpersonal interaction), intergroup motivation (affiliation to a particular community), self-confidence, intergroup attitudes (desire and sense of satisfaction to communicate with L2 community), communicative competence, and personality all influence a person’s level of L2 WTC.

Many of the studies that have adopted the above L2 WTC models are quantitative studies that collect survey data from usually very large sample sizes. Researchers use statistical methods such as correlations, multiple regressions, and structural equation models to explore factors that contribute to learners’ L2 WTC. In synthesizing the reported correlation coefficient values, L2 communication confidence has been suggested to be the strongest determinant for L2 WTC in multiple studies (Clément et al. 2003; Peng and Woodrow 2010; Yashima 2002; Yashima et al. 2004), explaining more than 50% of the variance in L2 WTC. The second strongest predictor for L2 WTC is perceived L2 competence (Denies et al. 2015; Joe et al. 2017; MacIntyre and Charos 1996), which explains roughly 25% of the variance. L2 anxiety is found to be a mild negative predictor for WTC (Denies et al. 2015; MacIntyre and Charos 1996; Peng 2015), explaining approximately 10–25% of the variance.

More recent models conceptualise L2 WTC less as a trait variable, but more as a dynamic, state-like psychological readiness, subject to the influence of situational variables (see MacIntyre 2020 for a recent review). In these studies, L2 WTC is analysed on a moment-by-moment, turn-by-turn basis, contingent upon the interplay between various factors. They include individual factors such as proficiency levels, anxiety, self-confidence, affective factors, cognitive conditions, motivation and attitudes, gender, age, etc., (Pawlak and Mystkowska-Wiertelak 2015; Shan and Gao 2016). In addition, there are situational factors such as classroom interactions (Cameron 2021; Cao 2011; de Saint Leger and Storch 2009; Robson 2015; Peng 2012; Yashima et al. 2018; Zarrinabadi et al. 2014), specific language tasks (MacIntyre and Legatto 2011; Nematizadeh and Wood 2019; Wood 2012, 2016), intercultural exchanges (Gallagher 2013; Gallagher and Robins 2015; Kang 2005), and cultural traditions (Cao 2011; Peng 2012). The findings of these studies support L2 WTC as a dynamic, changing, and situational variable.

Most of the existing studies have attempted to unveil the factors that contribute to healthy L2 WTC, as well as factors that hinder learners’ WTC. Relatively fewer studies have explored to what extent WTC contributes to L2 language use (but see Clément et al. 2003; Yashima et al. 2004) and L2 learning outcomes (Denies et al. 2015; Derwing et al. 2007). In the present study, we adopt a mixed method design and investigate the L2 WTC of Korean-speaking short-term sojourners in Australia. We aim at investigating whether and how L2 WTC influences learners’ opportunities for establishing L2 contact and consequently how such influence affects their language performance. Specifically, we examine learners’ oral fluency as a measure of their L2 performance, which has been suggested to be affected by L2 exposure (Collentine and Freed 2004). Oral fluency has been defined and operationalized in various ways, among which temporal fluency, which measures the smoothness of speech at a given time, is the most commonly adopted measure (Kowal et al. 1975; Skehan 2009). In the present study, we quantitatively model the relationship between L2 WTC, amount of L2 exposure, and measures of temporal fluency. In addition, we conduct qualitative theme-based analyses on a semi-structured interview with participants, which reveals in-depth perspectives on how the factors are interrelated.

1.1. Willingness to Communicate and Context: Inside and Outside the Classroom

Summarising the previous viewpoints on L2 WTC, this construct can be conceptualised both as a stable trait variable and as a dynamic and fluctuating situational variable. An L2 speaker’s willingness to engage in L2 interaction is a function of his or her personal traits and situational variables related to specific context. However, context is a complex notion to define, and it is hard to quantify its contribution. Context can mean discourse situations, such as informal daily conversations versus formal public speech (MacIntyre and Charos 1996), or group size and relationship among interlocutors (Cao and Philip 2006). Context can be used to refer to the school or classroom environment, including the degree of support from school, teachers, peers, and family (MacIntyre et al. 2001; Robson 2015; Peng and Woodrow 2010). It can also mean the larger sociocultural environment and quality of L2 contact (Clément et al. 2003; Denies et al. 2015; Lee 2018; Liu 2017).

The situational variation of L2 WTC inside and outside the classroom is a relatively new and intriguing question explored by several recent studies that examined classroom-based learners (Denies et al. 2015; Lee and Lee 2020; MacIntyre et al. 2001; Peng 2015). For classroom-based learners, particularly those in a foreign language context, the classroom is where learners have the opportunity to be intensively exposed to and use the L2. Factors that can influence classroom WTC, such as school, teacher, peer, and task (Peng 2015), type of teacher feedback and classroom environment (see for example Cao and Philip 2006; Zarrinabadi et al. 2014), are somewhat restricted to the social structure of the specific educational setting, whereas the factors that affect L2 WTC “in the wild” are much less predictable. Despite the varying educational contexts in the aforementioned studies, all of them have reported a similar finding that learners’ classroom WTC is higher than their out-of-class WTC. This finding strongly suggests that L2 WTC may operate in different ways across situations (Peng 2015) and that the determinants of L2 WTC are different in the in-class versus out-of-class settings. However, there has been no general agreement within the literature on the operationalisation of L2 WTC.

Based on findings from Dutch-speaking learners of French, Denies et al. (2015) argued that integrative motivation played a more decisive role in influencing classroom WTC than out-of-class WTC. Integrative motivation refers to learners’ “desire to learn an L2 for the purpose of communicating with members of the L2 community” (Denies et al. 2015, p. 720). These classroom-based foreign language learners perceived the classroom as their comfort zone for L2 interaction. Those who were integratively motivated perceived the classroom as the main place to learn the L2 and demonstrated a stronger readiness to communicate in the L2. Outside the classroom, learners stepped outside their protected zone. Their societal willingness to communicate was more strongly hindered by their anxiety levels and perception of their own competence.

Peng (2015) also found higher classroom WTC than out-of-class WTC in her observation of Chinese EFL learners. However, her finding on the contribution of integrative motivation to WTC inside and outside the classroom was the opposite to that of Denies et al. (2015). Peng (2015) found that integrative motivation contributed more to out-of-class WTC than to in-class WTC. Classroom WTC was found to be strongly influenced by learners’ classroom experience and L2 anxiety. WTC outside the classroom was only determined by learners’ integrativeness. Peng explained that classroom WTC is more determined by learners’ classroom experience (school and teacher influence, peer interaction, task orientation). When stepping out of the classroom, they are freed from the obligation of using the L2. Thus, their WTC is largely determined by their interest in the global community and readiness to interact with intercultural partners.

In sum, it seems clear that learners demonstrate higher L2 WTC inside the classroom than outside the classroom. Yet, it remains a question why this is the case. Previous studies have all treated situational variation as a within-subjects variable and have measured the same group of classroom-based learners’ L2 WTC inside and outside the classroom environment. From a different perspective, we aim to investigate inside-vs-outside classroom WTC by treating it as a between-subjects variable and compare the L2 WTC of classroom-based learners and workplace learners in the same target language environment.

1.2. Willingness to Communicate, L2 Interaction, and L2 Speaking Abilities

In contrast to the number of studies that have tried to uncover the determinants of WTC, there are relatively fewer investigations about how WTC influences L2 language use and L2 learning outcomes. Among the studies that have addressed the contribution of WTC to L2 communication frequency (Clément et al. 2003; MacIntyre and Charos 1996; Yashima et al. 2004), all of them reported a significant contribution of L2 WTC to the amount of learner engagement in L2 interaction. The learners in these studies were classroom-based learners in either bilingual education or EFL programs.

The relationship between L2 WTC and L2 achievement, especially L2 speaking abilities, is less clear. On the one hand, L2 WTC is asserted to promote increased participation in L2 communication situations, which in turn is predicted to promote more opportunities to practice speaking and develop speaking proficiency (MacIntyre et al. 2003). For example, Derwing et al. (2007) was a two-year longitudinal study that explored the relationship between L2 speaking fluency and L2 exposure among adult Chinese-L1 and Slavic-L1 immigrants in Canada. Oral fluency was measured by human raters’ holistic rating of participants’ speech samples rather than a refined acoustically based fluency analysis. The researchers found that the Slavic-speaking group’s fluency significantly improved over time, while the Mandarin group’s fluency showed little improvement. Their survey and interview data indicated that the Slavic-speaking immigrants had more opportunities for L2 interaction, higher L2 communication confidence, and higher L2 WTC than the Chinese-speaking immigrants. To account for the findings, Derwing et al. (2007) emphasized the role of the host community in determining whether newcomers are able to access opportunities to interact in the L2. They explained that Canadian-born individuals may lack confidence in establishing interaction with newcomers due to perceptions of cultural and social distance (Schumann 1976). Therefore, immigrants of European (including Slavic) origin are viewed as more similar and therefore easier to talk to than Chinese immigrants.

Other studies have reported either mixed findings or no relationship between L2 WTC and L2 learning achievement. For example, Kang (2014) found that Korean-speaking study-abroad (SA) learners gained L2 WTC after their sojourn. Their L2 interaction during the sojourn as measured by the Language Contact Profile (LCP) (Hernandez 2010, modified from Freed et al. 2004) was reported to have a significant positive correlation with participants’ displaying post-SA gains in speaking abilities, which were measured by face-to-face interviews, and holistically scored based on the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) proficiency guidelines (ACTFL (American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages) 1999). However, Kang (2014) did not find evidence of a direct relationship between L2 WTC and learners’ speaking abilities during or after the sojourn. Another study that examined the influence of L2 WTC on L2 achievement is Joe et al. (2017), who used participants’ school exam scores as a measure of L2 achievement. Their finding suggested that L2 WTC did not make a significant contribution to learners’ L2 achievement. However, since no detailed information about the exam was provided, we cannot assess what aspects of language learning were measured.

Further evidence of the effect of WTC on L2 achievement are found in several case studies, almost all of which select L2 oral temporal fluency as a measure of L2 performance. Temporal fluency measures smoothness of speech at a given time (Skehan 2009) and includes sub-measures such as speech rate, mean length of fluent runs (MLR), pause features, and the ratio of the speaker’s fluent and dysfluent runs (Iwashita et al. 2008). The case studies reported in Nematizadeh and Wood (2019) and Wood (2012, 2016) argue for a two-way influence between L2 speakers’ WTC and temporal fluency in spontaneous task performance. Such studies assume L2 WTC to be a fluid and dynamic construct that shows moment-to-moment fluctuation during a single task performance. The assumption holds that the same person’s L2 WTC may vary and fluctuate under different conditions that are contingent upon psychological factors (e.g., excitement, responsibility, and security) and situational factors (e.g., topic, context, and interlocutor) (Kang 2005). The dynamics of L2 WTC are measured in these case studies (Nematizadeh and Wood 2019; Wood 2012, 2016) by the participants’ moment-by-moment self-rated WTC in a stimulated recall, based on video-recordings of their own task performances. Oral fluency is measured in terms of speech rate, MLR, and pause length. High WTC in a speaker was found to be associated with above-average fluency (MLR), whereas low WTC led to deteriorated fluency performance. Meanwhile, dysfluency performance heightened the speaker’s anxiety and resulted in lowered WTC. These dynamically informed case studies report important findings about a potentially strong relationship between L2 WTC and oral fluency, but it is difficult to compare these findings to those from other empirical studies that do not assume the moment-by-moment dynamicity of the WTC construct. In addition, due to the small sample sizes in these case studies (approximately 4 participants per study) (Nematizadeh and Wood 2019; Wood 2012, 2016), the difference between fluency and dysfluency can be quite subtle. This increases the risk of subjective judgment and leads to limited generalisability from the findings.

1.3. The Current Study

The current study is a mixed method study that investigates L2 WTC among two groups of Korean-speaking learners of English on short-term residency in Australia. The design of the study aims at filling several important gaps identified in the literature.

First, L2 WTC is predicted to have a direct relationship with learners’ frequency of L2 communication (MacIntyre et al. 1998) and we aim to test this prediction in the target learner groups. In addition, there are very few studies that have investigated how L2 WTC influences L2 learning achievement, particularly L2 oral fluency, which is the linguistic focus of the current study. Previous relevant studies either used human raters for holistic fluency rating, without the validation of more refined temporal fluency measures (Derwing et al. 2007), or were restricted in the generalisability of their findings due to small sample sizes (Wood 2012, 2016). We aim to quantitatively investigate the relationship between L2 WTC, amount of L2 exposure, and L2 oral fluency through inferential statistics. Because of this, it is not feasible to treat L2 WTC as a fluid construct subject to moment-by-moment dynamic change. Therefore, we follow most quantitative investigations of L2 WTC (e.g., Clément et al. 2003; Denies et al. 2015; Yashima et al. 2004) and assume this construct to be relatively stable. L2 WTC is thus conceptualised as “a general tendency to communicate in the L2 across situations, or to what extent the individual estimates that he or she will initiate communication in English whenever opportunities to do so arise” (Gallagher 2013, p. 66).

Second, the current study extends the research on L2 WTC to a new sociocultural context of learning and to new groups of language learners. We have seen extensive applications of the constructs in explaining learner characteristics in North America and in EFL settings in Asia. Most of these studies have focused on classroom-based learners. The few studies that looked into study-abroad students (Lee 2018; Yashima and Zenuk-Nishide 2008) compare them with at-home students. Our study focuses on an English naturalistic learning environment in Australia, which has not been extensively studied for WTC-related learner characteristics. Our focus is to explore diversity among Korean-speaking short-term sojourners in Australia. We compare classroom-based learners (students) with learners in the workplace (workers). The two groups come from the same first language background and have a similar experience of learning English as a foreign language in their home country. Due to their different reasons for coming to Australia, their motivations to learn English and their willingness to communicate in English are predicted to vary within and between groups. The similarities and differences between the two groups make them an ideal learner population for us to investigate WTC inside and outside the classroom as a between-subjects variable. Our goal is thus to investigate how characteristics of individual learners in the Australian context might lead to varying opportunities of L2 language use and L2 learning experiences.

Third, in addition to our quantitative investigation, we examine in-depth qualitative data from recorded semi-structured interviews that provide an emic perspective on L2 WTC. Our mixed method design thus blends etic and emic perspectives. Previous quantitative modelling studies have the strength of mapping directional interrelations between a large number of variables. But without adequate qualitative data about the learners and their learning experiences, it is often difficult to account for unpredicted path models and unexplained variance. Therefore, we postulate that it is necessary to know the internal perspective from the learner to formulate a clearer picture of L2 acquisition in a SA context.

The current study addresses the following research questions:

Research Question 1 (RQ1).

What is the relationship between Korean-speaking short-term sojourners’ L2 willingness to communicate and their amount of L2 exposure in the target language environment?

Research Question 2 (RQ2).

How does Korean-speaking short-term sojourners’ L2 willingness to communicate and amount of L2 exposure influence their oral fluency development?

Research Question 3 (RQ3).

Do the two groups of short-term sojourners, students and workers, differ in terms of their L2 willingness to communicate, amount of L2 exposure, and oral fluency?

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Setting and Participants

The current study focuses on South Koreans on short-term visits to Australia. In South Korea, English language skills are highly valued among the middle class and widely acknowledged as a necessity for entry and advancement into professional and managerial occupations (Stevens et al. 2006). English language programs in South Korea have been criticized for having a heavy emphasis on grammar and reading skills at the cost of the development of learners’ communicative skills in speaking, writing, and listening (Nunan 2003). Korean domestic students generally have limited contact with the English language. As a result, many Korean students consider studying or living abroad in English-speaking countries as a pathway to improving their English language skills and getting a better job in South Korea. Short-term visitors include young adult students who get enrolled in short-term English-language programs and other types of visitors for the purpose of “traveling, observing, consulting, sharing or demonstrating specialised knowledge or skills” (Stevens et al. 2006, p. 174).

There were 30 participants in the present study (6 males and 24 females). All were Korean learners of English, aged 25 to 35. At the time of data collection, all participants were short-term visa holders who had been living in Australia for longer than six months but less than two years. Participants with less than six months of residency were not recruited, as some previous research reports that new arrivals in the initial 4–6 months following migration tend to experience highly variable emotional reactions and levels of psychological adjustment (Gallagher 2013; Ward et al. 2001). For consistency, two years of residency was set as the upper limit, as the majority of our target participants were holding a two-year short-term study or working visa at the time of the data collection. All the participants chose to come to Australia on their own, rather than as part of any organised study or work experience program.

The participants included two learner groups: students (3 males and 12 females), and workers (3 males and 12 females). The students had a mean age of 28 years (25–34, SD = 2.07), and the workers a mean age of 29 years (25–35, SD = 2.54). The students had a mean length of residence in Australia of 1.4 years, and the workers a mean length of residence of 1.3 years. As the two groups had comparable lengths of residence (t = −0.595, SE = 0.157, estimate = −0.093, p = 0.557), we did not include it as a variable in the analysis. None of the participants had ever taken any standardized English proficiency tests such as IELTS or TOEFL. However, the participants on a whole self-reported their English proficiency to be at the low-intermediate to intermediate level. Based on the interview speech samples we collected, we assessed both groups to be at the B1 level, equivalent to a low intermediate level from the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). Our assessment was based on the fact that most participants were capable of producing simple sentences that were relevant to personal experience, giving their opinions with detailed explanations, but they had difficulty in producing sentences on topics that were unfamiliar to them (Council of Europe 2001). Our fluency analysis on the speech samples from the two groups did not reveal any group differences and confirmed the comparability of the two groups in terms of English speaking proficiency (see Results Section 3.3).

The student participants were recent graduates from tertiary-level colleges in South Korea and were enrolled in an English program at a language centre in Melbourne. They were in Australia on short-term student visas and were enrolled in a variety of programs: an IELTS preparation program (1 male; 5 females), an English for academic purposes (EAP) program (3 females), and an English for general purposes (EGP) program (2 males; 4 females). Their main purpose of studying in Australia was to improve their English proficiency in order to become more competitive job applicants in Korea. Through the training offered by the English programs, they aimed at achieving good scores in the TOEIC or TOEIC Speaking test, which is the one typically desired by Korean employers (Lee 2014).

The workers were short-term working holiday visa holders working full time in Melbourne. Working holiday visa holders often travel to Australia for tourism and hold jobs to pay their daily expenses, along with gaining overseas career experience. The higher salary in Australia is a further attraction, as the minimum wage is almost double that of South Korea (Minimum Wage by Country 2020). The workers in the current study were recent graduates from tertiary-level colleges and post-secondary vocational training institutions in South Korea. Among the 15 workers, there were hairdressers (6 females), waitresses (3 females), kitchen hands (1 male; 1 female), a nail technician (1 female), a cleaner (1 male), a factory worker (1 female), and a food deliverer (1 male).

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. L2 WTC

The measure for L2 WTC (Table 1) was a questionnaire adapted and modified from Peng and Woodrow (2010). We chose this questionnaire as it covers the measurement of L2 WTC in a range of diverse conversational situations that the current participants may have encountered. The original questionnaire has two sub-constructs: WTC in meaning-focused activities and WTC in form-focused activities. We made a more refined categorisation of the meaning-focused items, by differentiating WTC for brief meaning-based activities (Table 1: items 1–5) and WTC for meaning-based activities of a potentially longer duration (Table 1: items 6–11). Brief activities are defined as an initiation of conversation only a few utterances in length, with a clear goal for the interaction. Durative activities involve a more open-ended frame of discourse that can range from a few sentences to more extended conversations with no specific pre-determined topics. The brief vs. durative division provides a heuristic for the differentiation of speech scenarios in our meaning-oriented items. As one reviewer has pointed out, compared to the brief activity items, the durative activity items are also more clearly situated and involve better specified interlocutors.

Table 1.

WTC in English Questionnaire (modified from Peng and Woodrow 2010).

Our modified version of the questionnaire includes 15 items on a 6-point Likert scale (Cronbach α = 0.95). The questionnaire items were translated and administered in Korean to avoid misunderstanding of certain words which may have been beyond the participants’ level of English competence.

2.2.2. Amount of L2 Exposure

The Language Contact Profile (LCP) (Freed et al. 2004) was adapted as the measure of amount of L2 exposure. To accommodate the two groups of participants (particularly the workers), we excluded the items that were only relevant to classroom-based sojourners and kept those that could be applied to both groups. The questionnaire we used (Appendix A: Part I and Part II) included two components, one of which collected information on the amount of L2 interpersonal communication with different types of interlocutors (e.g., native or non-native speakers of English) in varying situations (e.g., inside or outside school/workplace). The other component was amount of L2 contact, which collects information on the amount of receptive L2 use for various purposes (e.g., watching movies, reading books, listening to music). This questionnaire was also translated and administered in Korean.

2.2.3. The Semi-Structured Interview

Participants’ in-depth insights related to WTC during their sojourn were elicited by a semi-structured interview conducted in English. The interview protocol is available in Appendix B. The last question in the interview was added primarily to elicit participants’ oral speech for fluency analysis. The question asked participants to narrate an unpleasant experience in interacting with non-Koreans in Australia. The question elicited a mean length of 2.5 min of speech from the participants. Previous research has typically collected 1–3 min of monologue narratives for temporal measures of oral fluency by L2 learners (Tavakoli 2016) and thus mean length of learner monologues in the current study provides the basis of an acceptable measure of temporal fluency.

2.3. Procedure

The participants were recruited via Kakao Talk, which is a popular mobile chat application used by Koreans (Lee 2019). Participants’ informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. Their personal information was collected and checked to ensure that they fit the selection criteria (i.e., L1 Korean; minimum low-intermediate English proficiency; short-term visa status in Australia; and minimum six months and maximum two years’ residence). During the data collection, participants first completed a demographic questionnaire and the WTC questionnaire and were then invited for an individual interview with the first author. The interviews were carried out on the phone or face-to-face on the university campus where the authors were based. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

2.4. Data Analysis

The quantitative data were analysed using R statistical software (Version 4.1.1; R Core Team 2018). The alpha value was set at 0.05. To address RQ1 and RQ2, linear regression analyses were performed on all participants’ data to investigate to what extent their amount of L2 exposure or oral fluency was modulated by L2 WTC. Linear regression analyses met the assumptions of linearity, homogeneity of variance, normality, and independence. To address RQ3, t-tests analyses were used for the group comparison between the students and the workers.

Three measures of oral fluency were adopted in the study: speech rate, phonation/time ratio, and mean length of fluent runs, which have been reported to be related to L2 situational WTC (Wood 2012, 2016). The first measure of speech rate was calculated as the total number of words spoken per minute. When counting the total number of words spoken, fillers (i.e., ah, uhm, umm, or yeh), false starts, simple repetitions, and self-initiated repairs, and other foreign languages (i.e., Chinese, Korean and “Konglish”) were excluded, and only repaired utterances were counted. The second measure of phonation/time ratio was the percentage of the total recorded time spent on speaking. The third measure was the mean length of fluent runs, which refers to the mean number of words produced between pauses. Silences longer than 0.3 s were considered to be a pause, as a silence shorter than 0.3 s can be confused with the aspiration of stop consonant sounds (Towell et al. 1996). PRAAT, a speech analysis software program, (Boersma and Weenink 2019) was used to measure pause length. We conducted a Pearson’s product-moment correlation analysis to check whether the three fluency measures were correlated before performing linear regressions.

Theme-based qualitative analysis was conducted on the interview transcripts with NVivo (Version 12; QSR International Pty Ltd. 2018). The initial coding scheme was created based on our synthesis of the contributing factors to L2 WTC from the literature (motivation for L2 communication, frequency of L2 communication, context of L2 communication, confidence in L2 communication, perceived competence in L2 communication, and personality) and factors contributing to L2 unwillingness to communicate (unWTC) (anxiety, perceived low competence in L2 communication, personality). New codes were added in the coding process (see Section 3). The first author coded all the data. The second author coded a randomly selected 30% of the data and the agreement rate was above 0.9.

3. Results

3.1. RQ1: Relationship between L2 WTC and Amount of L2 Exposure

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the mean scores and standard deviation (SD) of Korean-speaking short-term sojourners’ (students and workers) L2 WTC, amount of L2 interpersonal communication, and amount of L2 contact. The scores for the sub-constructs for L2 WTC are also reported.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of students’ and workers’ mean scores and standard deviation (SD) of L2 WTC and self-reported amount of L2 use.

Linear regression analyses were performed to predict to what extent L2 WTC influenced amount of L2 exposure. Results show that L2 WTC did not have a significant influence on participants’ amount of L2 interpersonal communication (t = 1.431, SE = 0.252, estimate = 0.360, p = 0.164). However, L2 WTC had a significant influence on amount of L2 contact (t = 2.249, SE = 0.065, estimate = 0.147, p = 0.032) and the coefficient of determination R2 suggests that approximately 15% of the variance in the dependent variable (amount of L2 contact) was explained by L2 WTC (also adjusted R2 = 0.123). When we used the mean score of the amount of L2 exposure as the dependent variable (averaging amount of L2 interpersonal communication and amount of L2 contact), the influence of L2 WTC was still significant, but with less predictive power (t = 1.965, SE = 0.126, estimate = 0.247, p = 0.05, R2 = 0.12, adjusted R2 = 0.09).

We carried out follow-up linear regression analyses to explore which of the sub-constructs of L2 WTC significantly contributed to amount of L2 contact. We found that WTC in durative meaning-focused activities was the only sub-construct out of three that yielded a significant result (t = 3.069, SE = 0.057, estimate = 0.173, p = 0.005), and its predictive strength indicated by the coefficient values (R2 = 0.25, adjusted R2 = 0.23) was strong. WTC in brief meaning-focused activities (t = 1.534, SE = 0.07, estimate = 0.1, p = 0.136) and WTC in form-focused activities (t = 1.57, SE = 0.06, estimate = 0.09, p = 0.128) failed to yield significant findings.

As a follow-up, two separate linear regression analyses were conducted in the student and worker groups. We identified very similar findings in the two groups as compared to the above overall findings on the relationship between L2 WTC and amount of L2 contact: both students’ and workers’ L2 WTC had a significant influence on their amount of L2 exposure (students: t = 2.249, SE = 0.065, estimate = 0.147, p = 0.032, R2 = 0.15; workers: t = 2.249, SE = 0.065, estimate = 0.147, p = 0.032, R2 = 0.15). Furthermore, it was also only the sub-construct of L2 WTC in durative meaning-focused activities that had a significant influence on amount of L2 exposure in both groups (students: t = 3.069, SE = 0.06, estimate = 0.173, p = 0.005, R2 = 0.25; workers: t = 3.069, SE = 0.06, estimate = 0.173, p = 0.005, R2 = 0.25).

3.2. RQ2: Influence of L2 WTC and Amount of L2 Exposure on Oral Fluency

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the mean scores and SD of participants’ L2 oral fluency in terms of the three fluency measures (speech rate, phonation time ratio, and mean length of fluent runs).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of students’ and workers’ mean scores and standard deviation (SD) of L2 oral fluency based on three fluency measures.

First, Pearson’s product-moment correlation analyses indicated that the three fluency measures were significantly correlated: speech rate and phonation time ratio (t = 7.126, p < 0.0001, r = 0.803), speech rate and mean length of fluent runs (t = 10.055, p < 0.0001, r = 0.885), and phonation time ratio and mean length of fluent runs (t = 7.087, p < 0.0001, r = 0.801). A second series of Pearson correlation analyses showed that none of the fluency measures had a significant correlation with the main variables in this research question, i.e., L2 WTC and amount of L2 exposure.

Linear regression analyses on all the participants failed to yield any significant result on the influence of L2 WTC on oral fluency measures: speech rate (t = 0.906, SE = 4.695, estimate = 4.256, p = 0.372), phonation time ratio (t = 0.56, SE = 2.064, estimate = 1.155, p = 0.58) and mean length of fluent runs (t = 0.508, SE = 0.223, estimate = 0.11, p = 0.62). Follow-up linear regression analyses in the student and worker groups, including the sub-constructs of L2 WTC, showed similar non-significant findings. Similarly, linear regression analyses on the influence of the amount of L2 exposure on oral fluency also did not lead to any significant finding in the student and worker groups, with no differences observed by either amount of L2 interpersonal communication or amount of L2 contact.

3.3. RQ3: Students versus Workers

3.3.1. Quantitative Analysis of Group Difference

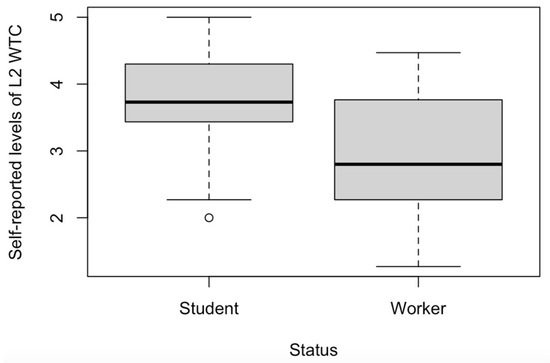

The third research question attempts to compare the two short-term sojourner groups in terms of L2 WTC, amount of L2 use, and oral fluency measures. The relevant descriptive statistics are reported in Table 2 and Table 3. ANOVA analyses show that the two groups differed significantly in terms of their overall L2 WTC (t = 2.508, SE = 0.357, estimate = 0.894, p = 0.018), with students having significantly higher WTC than workers (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rate of L2 WTC among students and workers.

Among the three sub-constructs within L2 WTC, there was a significant group difference in terms of WTC in brief meaning-focused activities (t = 2.196, SE = 0.378, estimate = 0.83, p = 0.037) and WTC in durative meaning-focused activities (t = 2.564, SE = 0.385, estimate = 0.987, p = 0.016), where in both cases, students had higher levels of these WTC sub-constructs than the workers. However, there were no significant group-based differences in terms of WTC in form-focused activities (t = 1.386, SE = 0.469, estimate = 0.65, p = 0.177).

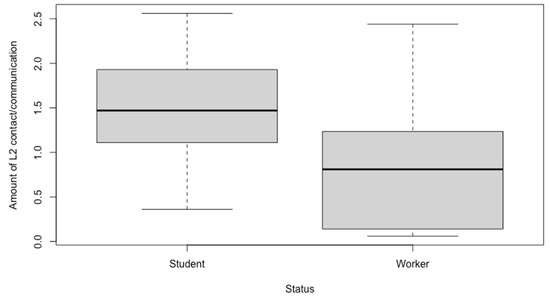

Regarding the amount of L2 exposure, students did not have a larger amount of L2 interpersonal communication than workers (t = 1.517, SE = 0.523, estimate = 0.793, p = 0.140). However, students reported a larger amount of L2 contact than workers (t = 4.02, SE = 0.118, estimate = 0.473, p = 0.0004). When we combined the two measures of L2 communication/contact into a composite score, the student group scored significantly higher than the workers (t = 2.403, SE = 0.254, estimate = 0.611, p = 0.023). This is visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Amount of L2 contact/communication (composite score) among students and workers.

Regarding oral fluency, the two groups did not show significant differences in any of the oral fluency measures: speech rate (t = 1.274, SE = 9.668, estimate = 12.321, p = 0.213), phonation time ratio (t = 0.60, SE = 4.305, estimate = 2.583, p = 0.553), or mean length of fluent runs (t = 0.86, SE = 0.461, estimate = 0.397, p = 0.397).

In sum, the students had a significantly stronger desire to integrate (i.e., higher WTC) with non-Korean speaking communities and to be engaged in communication in English than the workers. The students also reported a significantly larger amount of L2 exposure than the workers. Nonetheless, the students and the workers showed comparable oral fluency, which suggests that the two groups of participants had similar speaking proficiency, despite having different levels of L2 WTC motivations and L2 contact.

3.3.2. Qualitative Analysis of Interviews: A Group Comparison

Five main themes (including some subordinate themes) emerged from the interview data with students and workers. The main themes were motivation of communication, frequency of communication, self-esteem, personality, and context of L2 contact. The themes were coded separately for L2 WTC and L2 unWTC. Table 4 and Table 5 present the frequency of interview references coded for the themes and sub-themes of WTC and unWTC tendencies, respectively. We will elaborate on the theme-based findings by explaining the similarities and differences observed in the two groups.

Table 4.

Frequency of interview references tallied for themes of WTC.

Table 5.

Frequency of interview references tallied for themes of unWTC.

Similarities between Students and Workers: Major Contributors to L2 WTC

Several common contributors to L2 WTC were found in student and worker interviews. The most important contributor was clearly the motivation for L2 communication, the most salient of which included to improve L2 competence, interest in language and culture, and to expand conversation topic diversity. The majority of students and workers expressed a keen wish to improve their L2 competence and cited this as a main motivator for L2 communication.

Student 15: Uh yes, I do. I wanna speak English very well. And uh then in order to improve my English I have to talk with non-Korean people. And I have to use the English very well.

Worker 14: It also important to speak non-Korean people. I can improve English skills.

The second recurring motivator for L2 WTC was interest in L2 language and culture, which reflected participants’ tendency towards integrative motivation. These participants held a positive attitude towards the multicultural dimension of Australian society and expressed an integrative motivation for intercultural communication in their L2. Thus, interest in the target language and culture fuelled the participants’ L2 WTC.

Student 11: I guess umm cus it help them out in your language skills. And it is always good to learn new culture because Australia has so many different type of people from different culture.

Worker 15: I came in Australia and I I met so many country people and I use say English and then they understand and I also understand and I- I learning to the another countries’ culture. And then I’m- I’m very interesting. And then I like it.

Frequency of L2 communication was the second main perceived contributor to L2 WTC. Students and workers commented about the importance of maintaining frequent use of English to keep their momentum of L2 WTC. Finally, extroversion emerged as the third theme under WTC. Participants expressed themselves as outgoing people with an interest in expanding new social networks and making new friends, especially non-Korean friends, in Australia.

Similarities between Students and Workers: Major Contributors to L2 unWTC

Students and workers raised convenience of communication in L1 and emotional attachment to the home country and culture as the two most important de-motivators for L2 WTC. Some participants expressed a strong attachment to their home country and culture and sought opportunities to establish networks with other Korean-speaking speakers in Australia. L1 was the dominant medium in these interactions, due to convenience and efficiency of communication.

Student 11: Uh I guess I feel more closer with Korean groups. Because my uh Korean is my mother language. And I feel more comfortable than speak English.

Worker 15: In the Korean group I use Korean language. They understand one hundred percent. I also understand. And then I- I feeling like so close and the Korean groups.

Self-esteem also emerged as a major theme in our coding for unWTC. Students and workers reported having perceived low competence in L2 communication, anxiety in L2 communication, and difficulty with L2 communication. When asked about preferences for interacting in the L2 and factors that influenced L2 speaking, some participants cited low L2 competence as a major factor that significantly limited their opportunities for effective L2 communication. For example, Student 13 worried about the intelligibility of her English and claimed that her L2 interaction required a “good” listener. These negative self-perceptions of low L2 competence contributed to unWTC.

Student 13: I think I need someone who can listen very well for me because my English kinda hard to understand because my English level kinda low still.

Worker 7: Uh I don’t like [to talk in English], yes umm because I can’t speak English even I have bad English language skill.

Anxiety in L2 communication was raised by students and workers when they were asked to comment on the preference to interact with non-Koreans in Australia. Some participants said that they felt nervous in interactions with non-Koreans, which involved speaking in English. For example, Worker 14 reported having plenty of opportunities for L2 communication with non-Koreans in her workplace, but she tried her best to avoid such interactions due to her own high anxiety of speaking English.

Student 5: Actually, I don’t like to talk with non-Koreans so much. Umm because I feel nervous when speaking in English.

Worker 14: I am feeling very nervous when I with non-Korean people. So I have many chance to with non-Korean. But I never had a time with them.

The last interview question that asked participants to recall an unpleasant experience in interacting with non-Koreans in Australia was primarily intended to elicit speech for fluency analysis. However, the data also yielded a salient theme related to participants’ unWTC. Ten students and eight workers narrated a story about the downside of being minorities in Australia. Student 15 reported that minorities were not welcomed by members of the Australian community, stating that Asian people were more likely to be targeted by a security guard or a transport inspector in conducting a bag or transport ticket check. Worker 2 narrated an experience of feeling ignored by an Australian waitress and that experience left a lingering effect on her succeeding interactions with locals.

Student 15: Uhm, and when I go to big supermarket uhm security said, “Can I check your bag?” maybe I think because of I’m an Asia- umm, umm, I hear that because I’m an Asian- Asian, they checked my bag… [When] my friends entered … take a tram, the ticket inspector said that uhm, “Can I check you card?” I think the situation is my friend is Asian. So, umm this situation is very unpleasant experience.

Worker 2: When we [Worker 2 and her friend] got menu, we can’t- we couldn’t understand menu because all is English … is really confused. So we asked to [Australian] wait- waitress… many things. But she most she ignored most things. So we weren’t very ah, we felt very nervous… So after that day, we of- we often feel nervous, so we couldn’t ask to Australian people.

Differences between Students and Workers

Several differences between students and workers were found. First, students showed a higher level of L2 WTC in their interview data than workers. Some students cited career opportunities as an important motivator for L2 WTC. Most of the students we interviewed wished to go back to Korea after the study period. They believed improved English competence and the study-abroad experience in Australia would enhance their profile and increase their career opportunities back in Korea. No workers mentioned this point. One possibility is that the workers were working in low-skilled occupations, where the concept of a “career” might not be as prevalent.

In addition, quite a number of students claimed that an important motivator for having L2 communication was to expand the diversity of conversation topics, and there were much fewer mentions of this among the workers. Students reported having a very limited range of topics when talking with non-Koreans. Some of them did not know what to say to non-Koreans in order to sustain an enjoyable conversation for both parties. They expressed a desire to be engaged in meaningful L2 communication with non-Koreans and to hear about others’ life stories and experiences.

Student 3: If you just umm speaking to like original group where you belongs to uh where be- where you belong to then, there will be like limitations about like topics or umm has to- umm English speaking skills umm if you go over to uh if you go out of the boundary where you were and umm obviously as you can talk more in English in like wide range.

Students’ greater L2 WTC was also shown in their awareness of establishing context for L2 communication. Some students talked about the importance of integrating into the local community as a way of practising English. They reported that they need to join a social club or go to church as a way to approach the local community. In addition, some students commented about the importance of having receptive L2 input via for example watching TV series, reading books, or listening to music. Such efforts to establish L2 communication was not commented on by the workers.

The second major group difference that we observed was that students tended to show high consistency in their (lack of) self-esteem, whereas workers demonstrated some ambivalence in self-esteem with regard to WTC and unWTC. Students perceived themselves as having low L2 competence, difficulty with L2 communication, and high anxiety in L2 communication. The workers talked more about these unWTC-related self-esteem traits, but at the same time, some also expressed that they had confidence in L2 communication. One worker participant reported having high competence in L2 communication. In terms of WTC-related self-esteem, workers seemed to demonstrate higher within-group variation than students.

4. Discussion

4.1. RQ1: L2 WTC and Amount of L2 Exposure

Our findings suggest that L2 WTC significantly predicted participants’ amount of L2 exposure in various activities in the L2 (e.g., watching English TV/movies, reading English books/newspaper, etc.). Participants with a stronger WTC tendency were more likely to be engaged in L2-based activities. L2 WTC did not have a significant influence on learners’ amount of L2 interpersonal communication with various types of interlocutors. However, the effect of WTC on the overall amount of L2 use was still significant when we averaged amount of L2 interpersonal communication and amount of L2 contact. These overall findings are in line with existing studies (Clément et al. 2003; MacIntyre and Charos 1996; Yashima et al. 2004) showing that L2 WTC influences learners’ amount of L2 exposure. Approximately 15% of the variance in the amount of L2 exposure was explained by L2 WTC in the current study, which is very close to the corresponding path coefficient (0.16) reported in MacIntyre and Charos (1996).

A novel finding in the present study is that learners’ willingness to engage in more durative types of meaning-based activities, which are more likely to lead to L2 interactions with extended conversation, had the strongest predictability on the amount of L2 exposure and accounted for 25% of the observed variance in amount of exposure. Learners’ WTC in very brief meaning-based activities (asking for directions, short self-introductions, ordering food, etc.) and in form-based activities (clarification requests for language use) did not have a significant influence on frequency of L2 contact. We cannot compare the current findings to those of Peng and Woodrow (2010), as they did not differentiate WTC by brief versus durative meaning-based activities. However, a plausible explanation is that the durative type of items in the WTC questionnaire, such as talking to a stranger in a queue or with neighbours, are speech situations that are voluntary and contain the uncertainty of potentially prolonged conversations with no clear mutual expectation of the conversation topic or speech act structure. The interview data informed us of the worry that many participants (especially students) had about not knowing appropriate conversation topics when talking with non-Koreans in Australia. Participants’ indicated willingness to initiate a conversation in durative meaning-based activities provides a more reliable self-assessment of their level of WTC and is the most robust predictor of amount of L2 exposure. The speech situations for brief meaning-based activities and form-based activities are much less voluntary and are likely to involve short utterances with more predictable speech act structures and conversation turns. Therefore, the categories of brief meaning-based activities and form-based activities do not appear to discriminate these learners. This finding relating to the impact of duration and the open-ended nature of L2 communication on L2 WTC has not been well discussed in the previous literature and could be further explored in future research.

4.2. RQ2: L2 WTC, Amount of L2 Exposure, and Oral Fluency

We failed to find a significant influence of L2 WTC and amount of L2 exposure on L2 oral fluency. This finding confirmed our expectations, since previous quantitative studies also failed to show a direct relationship between WTC and L2 achievement (Joe et al. 2017). These quantitative studies seem rather different from qualitative studies that have argued for the mutual influence of moment-by-moment WTC and oral fluency. Whether WTC influences learners’ fluency performance only when it is treated as a situational variable (Wood 2012, 2016), rather than as a stable trait-like tendency, is worth further exploration. For now, there are simply not enough quantitative studies for reference.

One would expect to find a connection between amount of L2 exposure and oral fluency, but this was not supported by the data. It is widely acknowledged that there is a great deal of variability among study-abroad learners and that the sojourn experience does not guarantee language gains. Some well-cited studies (e.g., Collentine 2004; Freed et al. 2004) reported no clear effects of SA on sojourners’ oral fluency development. Whether sojourners can achieve SA benefits is likely to be mediated by many factors such as the pre-departure proficiencies of the students, the duration of the sojourn, and the ages of the students (Tullock and Ortega 2017). In addition, sojourners are subject to ideological struggles and identity destabilisation, which can also filter through their learning opportunities. Our finding adds another piece of evidence for the dissociation between sojourners’ amount of L2 contact in the target language environment and their language achievement. We might have found different results had we focused on longer-term sojourners (e.g., students completing a degree program or four years in Australia, or workers on skilled migrant visas). In addition, the use of another measurement of L2 contact could have yielded different results. The current measure only includes ten items that might not be able to capture the full range of interpersonal and non-interpersonal L2 activities in which our participants (particularly the learners in the workplace) were engaged. The existing L2 contact questionnaires that have been designed for study-abroad sojourners are mostly applicable to learners in institutional study-abroad programs (Ranta and Meckelborg 2013). There is a lack of reliable measures for sojourners’ language contact “in the wild”. Future research could start with an exploratory needs analysis to identify the variety of daily and weekly L2 activities accessible to the target learner group in their specific naturalistic environment. Such analysis would provide a great basis for L2 contact questionnaires for learners in the wild. In sum, there is great potential for further progress in determining the relationship between L2 WTC, amount of L2 exposure, and oral fluency.

4.3. RQ3: Students and Workers: A Comparison

4.3.1. Common Contributors to the Two Groups’ L2 WTC and unWTC

Our review of the literature indicates that the most important predictors of L2 WTC are L2 communication confidence and perceived L2 competence. Our qualitative analysis revealed that the main contributors to Korean-speaking short-term sojourners’ L2 WTC were the motivation to enhance L2 competence, integrative motivation, the wish to manage a variety of L2 conversation topics, frequent use of the L2, and extroversion. The main contributors to the participants’ unWTC were convenience of communication in L1, emotional attachment to home country, perceived low competence and difficulty with L2 communication, and anxiety in L2 communication.

L2 communication confidence and perceived L2 competence in our analysis are important contributors to unWTC. The majority of the participants considered themselves as lacking L2 communication confidence and as having low L2 competence, which explained why most of them had a strong wish to enhance their L2 competence. Integrative motivation was identified as a strong contributor to WTC. This finding aligns well with previous studies (Denies et al. 2015; Lee 2018; Peng 2015; Yashima et al. 2004). Anxiety as a main predictor of unWTC was also within expectation and is well-supported by the literature (MacIntyre and Charos 1996; Liu and Jackson 2008).

Four themes that emerged from our data have not been extensively discussed in the previous WTC literature. These are managing L2 conversation topics (WTC), convenience of using L1 for communication (unWTC), emotional attachment to home country (unWTC), and perceived social exclusion (unWTC). We found that these four themes were all related to our participants’ identities as study-abroad sojourners. Decades of study-abroad (SA) research have shown that identity “mediates sojourners’ pursuit of access to opportunities for language use and drive it as well” (Tullock 2018, p. 268).

When immersed in a new sociocultural environment, sojourners’ sense of identity is destabilised and often goes through an experience of conflict and struggle before re-entering a stage of emotional stability (Block 2007). Leaving the protected zone of the EFL classroom, sojourners are challenged with the need for situated interactions in the L2 with real world consequences. Our participants had low-intermediate English proficiency and grappled with initiating and sustaining interactions with non-Koreans, often due to a lack of knowledge of shared topics and L2 competence. This motivated some of them to seek opportunities for L2 communication with non-Koreans. This became a means for them to expand on their linguistic repertoire and equip themselves with more interactional resources.

In this process of seeking legitimate peripheral participation (Lave and Wenger 1991) within the host community, some of our participants found themselves unwilling or unable to negotiate difference and thus demonstrated a stronger disposition to disengage from the goal of gaining access to language. Their home-grounded identities were strengthened as a result (Kinginger 2008; Pellegrino Aveni 2005). They stepped back to their L1-speaking comfort zone and maintained a strong connection with the L1-speaking social network. This could be easily achieved given the ethnocultural landscape in Australia where participants lived. There are strong, relatively cohesive Korean communities in Australia. Intergroup climate (i.e., the existing ethnocultural community in the city where participants lived) (Derwing et al. 2007) could be said to have facilitated the sojourners’ strengthening of their home-grounded identities.

The identity conflict experienced by the sojourners in our study engendered feelings of vulnerability, marginalization, and stereotyping that other groups of SA learners had also experienced (Iino 2006; Talburt and Stewart 1999). The fear of becoming the target of discrimination by the locals was reinforced through these experiences narrated by the sojourners. The perceptions of being socially marginalized or discriminated against threatened the sojourners’ sense of status and constituted significant challenges to L2 WTC. However, we should emphasize that our participants talked about perceptions of social prejudice only as responses to the last interview question that explicitly asked them to narrate an unpleasant experience of interacting with non-Koreans in Australia, and not to the other questions in the interview. There was not enough evidence showing that perception of social prejudice was a salient contributor to our participants’ unWTC.

4.3.2. Group Variation in L2 WTC Tendencies and Amount of L2 Exposure

Our quantitative group comparison revealed that the students had a significantly stronger desire to integrate with non-Korean-speaking communities and to be engaged in communication in English than the workers. The students’ stronger tendencies for L2 WTC than the workers were demonstrated in the results elicited from both the questionnaire and the interview. This finding aligns with previous work (Denies et al. 2015; Peng 2015) that L2 learners’ classroom WTC tends to be stronger than out-of-class WTC (contextualised as workplace WTC in a naturalistic learning environment). In addition, our students also reported significantly higher amounts of L2 exposure than the workers.

The students and the workers had different motivations for their sojourn experiences, which consequently led to different WTC tendencies and behaviours. The students had a relatively clear instrumental reason for studying abroad. Studying abroad was believed to bring them better opportunities for job hunting, higher social status (Lin and Man 2009), career success, and further academic achievement in the Asian context (Chao et al. 2019). The students were aware that they would only stay for a short-term period to improve English competence and to enhance their job search in the home country. They had literally invested in their L2 learning since they had to pay tuition for their ESL courses (whereas the workers were being paid during their sojourn). There was a stronger awareness among the students that they needed to make good use of the time during sojourn to maximize its benefits. They seemed to have been making more efforts to create channels of L2 communication.

It is also worth noting that the English programs the students were participating in were tailored to their specific language needs and interests, which could have increased their learning motivation (Basturkmen 2010; Dudley-Evans and St John 1998) and reduced anxiety of L2 communication. The teachers in the programs could have made recommendations to the students on the sort of activities that can benefit English language learning, such as reading English books, listening to English news, watching English TV channels, etc. It is likely that students had better access to suitable materials or at least might have been directed to suitable materials by their teachers through the English programs. The sojourners in workplace environments would not be able to enjoy the same affordances.

In contrast, we could not identify a clear reason why the workers chose to work short-term in Australia. Due to the nature of their occupations (such as hairdresser or factory worker), they might not be in a better position career-wise when returning to their home country. They functioned in their jobs on the basis of a very limited range of English language use. They wanted to improve their English competence, but did not demonstrate the effort of working towards this goal. They had potential opportunities to interact with interlocutors in English in the workplace and they appeared to be interculturally curious. However, they expressed strong anxiety or lack of confidence in L2 communication. They felt strongly about their low competence and difficulty with L2 communication. As a result, their WTC momentum seemed to be overshadowed by their unWTC mindset. As MacIntyre et al. (2011) observed, “for some people at some times, it is possible to be both willing and unwilling to communicate” (p. 93). Among these people, it can be argued that the emotional state of reaching out for social acceptance, and avoiding communication for self-protection, can co-exist in a state of ambivalence. The dynamic, fluctuating, socially constructed nature of WTC and unWTC was amply demonstrated by these Korean-speaking workers doing relatively low-pay, short-term jobs in Australia.

5. Conclusions

The current mixed-method study investigated two groups of Korean-speaking short-term sojourners’ experiences in Australia with regard to their WTC. Their inclination for L2 communication was motivated by L2 communication confidence, perceived L2 competence, integrative motivation, and was also mediated by the new sociocultural environment, their sense of identity, and emotions. WTC, particularly the willingness to engage in potentially extended and open-ended L2 conversations, was found to predict the amount of L2 exposure during sojourn. None of these individual difference factors were found to be associated with the sojourners’ linguistic outcomes in terms of oral fluency. Sojourners in the classroom showed a higher level of WTC and amount of L2 exposure than sojourners in the workplace.

We note that the study is not without its limitations, which must be borne in mind before making any generalisations about short-term sojourners. First, the study was limited by the relatively small sample size. Second, one-shot data collection does not reveal the dynamics of WTC and fluency development. In the future, it may be possible to collect data from classroom-based and workplace short-term sojourners at multiple time points during their stay to capture the dynamicity of WTC as a changing, situated variable. Third, the existing measures of L2 contact for learners in study-abroad programs may not provide a reliable measure of L2 contact for learners in naturalistic environments. An exploratory needs analysis is suggested as a precursor to a more reliable measure of L2 contact in the latter case. Finally, our interviews were conducted in English, since one of the interview purposes was to examine participants’ spoken proficiency. Considering the participants’ relatively low English proficiency, it is worth keeping in mind that they might not have been able to fully articulate their thoughts and feelings during the interview.

Despite limitations, the findings in the current study raise intriguing questions regarding the relationship between individual learners and naturalistic learning contexts in migration environments. These sojourners are individuals with no support offered by well-organized study-abroad programs. They have relatively low L2 competence and little preparation for intercultural communication before their sojourn. In the literature on study abroad and individual differences in SLA, very little has been reported on this type of short-term sojourner. To add to the findings we present here, we propose that more research be done to document the language experiences, social interactions, intercultural exchanges, and individual differences among short term sojourners in different host countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K. and H.Z.; data curation, J.K.; formal analysis, J.K., H.Z. and C.D.-H.; investigation, J.K., H.Z. and C.D.-H.; methodology, J.K. and H.Z.; project administration, J.K.; resources, J.K.; software, J.K., H.Z. and C.D.-H.; supervision, H.Z.; validation, J.K., H.Z. and C.D.-H.; visualization, H.Z. and C.D.-H.; writing—original draft, J.K. and H.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.Z. and C.D.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of The University of Melbourne (protocol code #1955128.1, approved on 19 August 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethics restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Questionnaire for Measuring Amount of L2 Exposure

Part I: Amount of L2 Interpersonal Communication

- 1.

- On average, how many days do you communicate with native or fluent speakers of English in a week?

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 day | 2 days | 3 days | 4 days | more than 5 days |

- 2.

- On average, how much time do you spend communicating in English with native or fluent speakers of English in a day at workplace or school?

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| never | 0–1 h | 1–3 h | 3–5 h | more than 5 h |

- 3.

- On average, how much time do you spend communicating in English with native or fluent speakers of English in a day outside of workplace or school?

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| never | 0–1 h | 1–3 h | 3–5 h | more than 5 h |

- 4.

- On average, how much time in a day do you spend communicating in English with strangers whom you think could speak English?

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| never | 0–1 h | 1–3 h | 3–5 h | more than 5 h |

- 5.

- On average, how much time in a day do you spend communicating in English with non-native speakers of English a day?

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| never | 0–1 h | 1–3 h | 3–5 h | more than 5 h |

Part II: Amount of L2 Contact

For each of the items below, choose the response that corresponds to the amount of time you estimate you spend on average doing the following activities in English per day.

- 1.

- Watching English language television

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| never | 0–30 min | 30 min–1 h | 1 h–2 h | more than 2 h |

- 2.

- Watching movies or clips in English

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| never | 0–30 min | 30 min–1 h | 1 h–2 h | more than 2 h |

- 3.

- Reading English language newspapers/magazines

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| never | 0–30 min | 30 min–1 h | 1 h–2 h | more than 2 h |

- 4.

- Reading books in English

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| never | 0–30 min | 30 min–1 h | 1 h–2 h | more than 2 h |

- 5.

- Listening to songs in English

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| never | 0–30 min | 30 min–1 h | 1 h–2 h | more than 2 h |

Appendix B

Interview Protocol

- 1.

- Do you like to talk in English?

- 2.

- Who do you want to use English more with? (i.e., friends? strangers?)

- 3.

- Do you think that your willingness to speak in English is important for integrating into the communities in Australia? Why?

- 4.

- Do you think that your willingness to speak in English is important for speaking better English? Why?

- 5.

- What factors do you consider important for you to talk more in English?

- 6.

- Do you like to engage in interactions with non-Koreans in Australia? Why?

- 7.

- Which group do you feel closer to, non-Koreans or Koreans in Australia?

- 8.

- Do you think that engaging in interactions with non-Koreans is important for you to talk more in English? Why?

- 9

- Do you think that engaging in interactions with non-Koreans is important for you to speak better English? Why?

- 10.

- Can you recall an unpleasant experience in interacting with non-Korean people in Australia? Can you describe the experience? When and where did it happen? What went wrong?

References

- ACTFL (American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages). 1999. ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines: Speaking. Hastings-on-Hudson: ACTFL. [Google Scholar]

- Basturkmen, Helen. 2010. Developing Courses in English for Specific Purposes. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Block, David. 2007. Second Language Identities. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2019. PRAAT: Doing Phonetics by Computer (Version 6.1.06) [Computer Program]. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Burgoon, Judee. 1976. The unwillingness-to-communicate scale: Development and validation. Communication Monographs 43: 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Denise. 2021. Case studies of Iranian migrants’ WTC within an ecosystems framework: The influence of past and present language learning experiences. In New Perspectives on Willingness to Communicate in a Second Language. Edited by Nourollah Zarrinabadi and Mirosławiroslaw Pawlak. Berlin: Springer, pp. 25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Yiqian. 2011. Investigating situational willingness to communicate within second language classrooms from an ecological perspective. System 39: 468–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Yiqian, and Jenefer Philip. 2006. Interactional context and willingness to communicate: A comparison of behavior in whole class, group and dyadic interaction. System 34: 480–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Chih Nuo Grace, Dennis McInerney, and Barry Bai. 2019. Self-efficacy and self-concept as predictors of language learning achievements in an Asian bilingual context. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 28: 139–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, Richard, Susan Baker, and Peter MacIntyre. 2003. Willingness to communicate in a second language: The effects of context, norms, and vitality. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 22: 190–209. [Google Scholar]

- Collentine, Joseph. 2004. The effects of learning contexts on morphosyntactic and lexical development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 26: 227–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collentine, Joseph, and Barbara Freed. 2004. Learning context and its effects on second language acquisition: Introduction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 26: 153–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Denies, Katrijn, Tomoko Yashima, and Rianne Janssen. 2015. Classroom versus societal willingness to communicate: Investigating French as a second language in Flanders. Modern Language Journal 99: 718–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwing, Tracey, Murray Munro, and Ron Thomson. 2007. A longitudinal study of ESL learners’ fluency and comprehensibility development. Applied Linguistics 29: 359–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Saint Léger, Diane, and Neomy Storch. 2009. Learners’ perceptions and attitudes: Implications for willingness to communicate in an L2 classroom. System 37: 269–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley-Evans, Tony, and Maggie Jo St John. 1998. Developments in English for Specific Purposes: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freed, Barbara, Norman Segalowitz, and Dan Dewey. 2004. Context of learning and second language fluency in French: Comparing regular classroom, study abroad, and intensive domestic immersion programs. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 26: 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Colin. 2013. Willingness to communicate and cross-cultural adaptation: L2 communication and acculturative stress as transaction. Applied Linguistics 34: 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Colin, and Garry Robins. 2015. Network statistical models for language learning contexts: Exponential random graph models and willingness to communicate. Language Learning 65: 929–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, Todd. 2010. The relationship among motivation, interaction, and the development of second language oral proficiency in a study-abroad context. Modern Language Journal 94: 600–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iino, Masakazu. 2006. Norms of interaction in a Japanese homestay setting: Toward a two-way flow of linguistic and cultural resources. In Language Learners in Study Abroad Contexts. Edited by Margaret Dufon and Eton E. Churchill. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 151–73. [Google Scholar]

- Iwashita, Noriko, Annie Brown, Tim McNamara, and Sally O’Hagan. 2008. Assessed levels of second language speaking proficiency: How distinct? Applied Linguistics 29: 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, Hye-Kyoung, Phil Hiver, and Ali Al-Hoorie. 2017. Classroom social climate, self-determined motivation, willingness to communicate, and achievement: A study of structural relationships in instructed second language settings. Language and Individual Differences 53: 133–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Su Ja. 2005. Dynamic emergence of situational willingness to communicate in a second language. System 33: 277–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Su Ja. 2014. The effects of study-abroad experiences on EFL learners’ willingness to communicate, speaking abilities, and participation in classroom interaction. System 42: 319–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinginger, Celeste. 2008. Language learning in study abroad: Case studies of Americans in France. Modern Language Journal 92: 1–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]