1. Introduction

The numbers of Spanish courses that are specifically designed for bilingual Latinx

1 students continue to grow in U.S. colleges and universities (

Beaudrie 2012). This upward trend reflects an increasing awareness of the strengths and needs that characterize this learner profile among language teachers and administrators. Scholars in the field of heritage language education agree on a number of foundational objectives and practices. These include—but are not limited to—a sociolinguistically informed curriculum, attention to the development of new registers, linguistic and literacy practice, and community engagement (e.g.,

Roca and Colombi 2003;

Beaudrie and Fairclough 2012;

Beaudrie et al. 2014;

Pascual y Cabo and Prada 2018). Moreover, given the sociopolitical and historical pressures framing language-minoritized racialized bi-/multilinguals, this line of pedagogical proposals has defined positive identity work as yet another core objective (

Leeman 2005,

2015;

Parra 2016a). This means that curricular spaces must be developed where students can learn about, discuss, and position themselves in relation to the sociohistorical formations and representations of the language-related issues affecting them and their communities. While these identity-related objectives lend themselves to different pedagogical approaches, they remain undertheorized and underexplored in the literature, particularly in reference to 21st century realities, such as digital environments.

Beyond heritage language education, current pedagogies in bi-/multilingualism across different contexts (such as TESOL and EME) have benefited from proposals that bear on the inclusion of meaning-making resources beyond those traditionally construed as the “target language”. Three such important approaches are multimodality (

Kress 2000), multiliteracies (

Cazden et al. 1996), and translanguaging (

García and Wei 2014). While each represents a different perspective, they coincide on a number of key points, which reveals the powerful synergies to be seized, both theoretically and in practice. For example, all three assume that meaning-making is not carried out solely through the linguistic structures limited to those assumed to constitute the named target language. They also acknowledge that communication happens in context, and that meaning is co-constructed. Multiliteracies and translanguaging consider the politicized nature of named languages and propose pedagogical practices that counter such politicization (

Cazden et al. 1996). Additionally, multimodality assumes that an overemphasis on language in communication studies leaves out the fundamental resources at work in actual meaning-making (

Kress 2003), and the complex relationships among these resources and processes are captured in translanguaging as a practical theory of language (

Wei 2018).

This article contributes to the literature on pedagogical spaces and strategies that center multilingualism and identity, with attention to the rich histories and profiles brought into the classroom by racialized language-minoritized students. Specifically, I explore digital collages as spaces for identity and experience representation, and I discuss their role and potential for composition curricula in heritage language programs. The

proyecto final reported herein was adapted from a (4- or 5-min) digital story to a digital collage (a self-contained assemblage of pictures, words, and colors created with digital tools), following the sudden changes faced in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the hopes of promoting key objectives while adapting to new and much less favorable circumstances. Each digital collage submission was accompanied by two written documents: one describing the processes driving the creation of the collage, and another explaining the meaning of the collage, creating transmediating flows between them. Qualitative content analysis (

Cavanagh 1997) was used to identify the patterns and categories that, when combined, speak to the pedagogical value of this project in relation to a number of the goals in heritage language education. In this article, I focus on exploring instances of identity and experience representation, and how these were enabled by complex translanguaging practices, thereby pushing our understanding of composition towards the realm of showing–telling. Before exploring the digital collages, I turn to providing an overview of the core tenets of heritage language education, with an emphasis on Spanish in the U.S. This is followed by a description that integrates the three theories comprising the theoretical bedrock: multiliteracies, multimodality, and translanguaging.

2. Bilingual Latinxs in the United States, Heritage Language Education, and Identity

In the U.S. context, the term “heritage speaker” (hereafter “HS”) refers to someone who grew up in a home/community where a non-English language was spoken and who, as a result, has acquired a certain degree of functionality in that language (the heritage language) and English (the majority language in the U.S.) (e.g.,

Valdés 2000). HSs of Spanish comprise the largest HS community in the U.S. and often report varying degrees of dominance and self-confidence in their heritage language and the majority language, with English typically being described as the dominant language in their repertoires. This should not be surprising, since it is common for HSs to have no access to bilingual support through schooling. It bears stating that the U.S. educational system typically fails to cater to this student profile in ways that are linguistically and culturally sustaining (

Pascual y Cabo and Prada 2018), and it is not uncommon for “immigrant parents to be advised to interrupt the use of their home language with their children” (

Lynch and Potowski 2014, p. 157). These and other issues may affect the use of Spanish by these youths. Therefore, when bilingual Latinx/Hispanic youths arrive at college, many of them feel the need to take or retake instruction in Spanish. At this stage, their linguistic and cultural self-esteem may be low as a product of their lived experiences and the naturalized social, educational, and historical pressures in place (

Parra 2016a).

Parra (

2020) describes how the vast majority of Spanish HSs come from (or have ties to) Latin America and the Caribbean and may come from families of different socioeconomic statuses and immigrant generations (

Suárez-Orozco 2001). Because of their varied backgrounds, HSs may have a wide array of abilities and skills across the externally named languages comprising their linguistic repertoires, with some of them exhibiting more receptive abilities in monolingual situations in the heritage language, and others showing high functionality across the different monolingual contexts. Nonetheless, the bilingualism of people of color, ethnic minorities, and transnational people is often perceived through a co-naturalized relationship between their language and race through the White-listening subject’s eyes and ears (

Flores and Rosa 2015), which is a perspective that is widely adopted in school settings and which reinforces the oppressive forces at work in language courses (

Prada 2019).

Considering the above, attention to the development of positive identities becomes an imperative in heritage language courses and programs. Identity plays a central role in the college lives of bilingual Latinxs (e.g.,

Leeman 2015;

Parra 2016b;

Showstack 2018) and it is of the essence to develop appropriate pedagogies to support it in its many fluid dimensions and forms. Therefore, these courses must incorporate an appropriate array of strategies to allow all students to engage in transformative work through readings, conversations, engagement with others, and the production of original artifacts as different lenses through which to reflect and grow. The composition course for HSs, where this

proyecto final was designed and completed with this in mind, offers a space for students to reflect on the complexity of their evolving identities as racialized language- minoritized bilinguals, but also as powerful communicators with complex histories and experiences.

4. Context

2020 disrupted the day-to-day dynamics around the world. As the COVID-19 pandemic spread around the globe, different national governments deployed various strategies to safeguard their populations against the novel virus. By the end of spring 2020, new rules and regulations were in place that prevented people from travelling, both nationally and internationally, and strict lockdowns and curfews were enforced in many countries. Transportation and commerce were negatively disrupted, which affected the global economy. Additionally, individual nations faced their own troubles, which ranged from economic distress to rising unemployment rates. Furthermore, in the United States, 25 May 2020 brought into the picture the murder of George Floyd as a result of police brutality. Subsequently, the Black Lives Matter movement gained unprecedented vigor as was reported in the media and on social networks. At the same time, the pressures of the presidential elections increased as 2020 drew to an end, with political rallies and media appearances by (then presidential candidate) Joe Biden and (then U.S. President) Donald Trump.

Considering the ways in which the realities of 2020 affected everyone around the globe, and while maintaining attention to the central goals and objectives of heritage language courses, this digital collage project was designed to provide students with an outlet to present an overview of their identities and experiences as bilingual Latinxs/Hispanics, through and beyond words, within the specific context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.1. The Students

A total of 22 students were enrolled in the course in the fall of 2020. Most of them were born and raised in the United States, and were 19–22 years old at the time that the proyecto final was completed. All of the students identified as Hispanic (x12), Hispano or Hispana (x3), Latino, Latina, or Latinx (x5), or as Latinx and Hispanic (x2). Three of them had received formal schooling in Spanish at some point in their childhoods, two of them grew up in Spanish-speaking countries (Mexico and Guatemala), and one went to a dual-language program in the Midwest. The rest of the students had attended K–12 in mainstream schools around the U.S. Midwest. As was demonstrated in the placement exam, all of the students were fluent bilinguals; however, their experiences with written Spanish, and with interacting in monolingual Spanish settings at home or abroad, varied greatly. Below, the students will be addressed as S-1, S-2, S-X, where the numbers represent the order in which they submitted their assignments.

4.2. The Course: Spanish Composition for Heritage/Native Speakers

In previous semesters, the course was taught face to face. However, in the fall of 2020, the first full semester after the COVID-19 pandemic started, the classes were taught online, and when possible, asynchronously. To this end, the course was adapted in order to create a more flexible schedule for students, more autonomy in time management, and less reliance on specific technologies that might not be available to students working from home. Taken together, the changes implemented sought to simplify the course. The lack of weekly meetings begged for fewer assignments, fewer reminders, fewer interrelated tasks, and more individual work, as well as structural consistency between the modules. At the same time, consequently, the teacher’s ability to engage at a personal level and perceive and react to the students’ needs diminished considerably.

One of the greatest changes implemented was the redesign of the final project: typically, a 4- or 5-min digital story or a podcast was developed over six weeks, with video and/or audio editing lab sessions, an ethnography component, group discussions, a heavy peer feedback and editing component, and individualized tutoring. However, during the pandemic, tasking students with the creation of these digital stories or podcasts at home was not an option. One could not assume that all of the students would have access to the technological tools required, and importantly, the collaborative nature of creating digital stories and podcasts, as conceptualized in this course, was out of the question. Therefore, the proyecto final was simplified to a digital collage that was to be completed in four weeks instead, which was an option that, at least a priori, seemed to present fewer potential technological difficulties, and importantly, could be completed on any laptop, tablet, or smartphone available to the students in their homes, while maintaining attention to the key goals and objectives.

4.3. “Identity and Uncertainty in 2020”—A Digital Collage Proyecto Final

Towards the middle of the semester, after having completed six assignments where writing was conceptualized following a more traditional definition (i.e., sequences of letters and blank spaces, and text as linear), the students were introduced to the notion of multimodal composing through a series of short videos created by the instructor and a small research assignment. They were subsequently asked to create a digital collage that captured the important aspects of their identities and subjective experiences as bilingual Latinxs/Hispanics in the United States in 2020. The title of the project was, “Identity and Uncertainty in 2020”. This title sought to create a thematic umbrella to guide the students in their digital collage creation. The year 2020 seemed to be too much of a pivotal point in history to make the project’s topic a more general one; hence, the emphasis on “in 2020”.

The instructions to create the collage were provided in the documents and instructional videos that were placed in the “Proyecto Final” folder on the course platform. These materials provided an overview of collage-making, digital art examples, and software options. Moreover, two special office hours sessions were held for Q&A over Zoom. One of the provided videos described the assignment in detail. It explained how the collage could include any combination of photographs, drawings, emojis/icons, and words/phrases, all of which could be original (created by the author) or borrowed from the Internet. The students could use playdough, clay or objects, shape and/or arrange them, and take a picture of them, to then edit them and add other layers of meaning. They could use any (number of) tools, artifacts, or software(s) to create their collage. A collage could focus on one particular drawing or photograph, or could include several interrelated ones, or it could include parts of the existing or original elements. Filters, light/darkness, and color adjustments could be used as resources too. The students were provided with examples of similar projects for illustration, and they were encouraged to be creative and nuanced in their visual narratives. Importantly, the students were reminded that this assignment did not evaluate their artistic skills in terms of aesthetic achievement, but rather their ability to create a collage that would be highly descriptive and communicatively powerful.

The final submission included three elements: (1) The collage (submitted as .jpg or .PDF); (2) A narrative describing the processes leading to the creation of the piece and the resources used to create the collage; and (3) A narrative containing the title of the piece and describing its meaning. The narratives had to be between 400 and 900 words, and no strict language policy was set, which allowed the students to deploy their linguistic repertoires flexibly. Beyond mere descriptions, these two documents captured the students’ perspectives on the proyectos, and their experiences creating them. In this exploration of the digital collages, I draw extensively from the perspectives presented in these documents.

Figure 1, shown below, shows S-6’s digital collage. As an exemplar, S-6’s collage showcases the general trends found in most of the submissions, including personal pictures (all faces have been covered for the purpose of this publication), emojis, and a wide array of semiotic resources (e.g., political symbols, strategically used colors), combined with written language, which, taken together, express the student’s experience by weaving in individual identity dimensions, such as her multilingualism, her spirituality, her nationality(-ies), and her moods and psychological states in the context of the year 2020. I return to a specific portion of this collage in

Section 5.2.3.

As this collage illustrates, meaning- and sense-making reflect an ecological integration of semiotic resources that include (but go beyond written) named language, and that situate the student, her world, and her agency at the center. In doing so, the bottom-up processes engaged for meaning-making bring the student’s repertoires, experiences, and abilities into the classroom in ways that traditional monolingual composition formats fail to accommodate. These multilayered digital assemblages are the product of complex trans-semiotizing (

Lin 2014) processes that mesh multimodal features together, critically and creatively, to share a story that is both shown and told in mutually constitutive ways (hence showing–telling), which illustrates Li

Wei’s (

2018) argument that translanguaging undoes the boundaries between language and other forms of cognition. The literacy practices at work in the creation of these

proyectos align with

Cope and Kalantzis’ (

2009,

2016) call to support the students’ development of their meaning-making potential in a diverse society through multiliteracies, whereby schools should promote and value all modes of communication (

Rowsell et al. 2008). Alongside the collage, two narratives were submitted where other more traditional forms of written literacy were promoted. Much of the pedagogical value of these three components is in the

proyecto as a whole, rather than in the individual elements.

5. Exploring the Proyecto Final Submissions: A Focus on Identity, Experience, and Self-Representation through Translanguaging

5.1. Emerging Themes across Three Interwoven Documents

The qualitative content analysis (

Cavanagh 1997) conducted on the

proyectos finales revealed two broad thematic trends that were central to the students’ identities and experiences, and these were the aspects related to: (1) Life during the COVID-19 pandemic; and (2) Politics and political developments. These categories bring in to focus the key dimensions of the students’ social, linguistic, and cultural selves, as well as how these interacted with the realities of 2020.

The first thematic category was developed through elements directly related to the pandemic, including, among others: virus symbols; pictures of hospitals, hand sanitizers, and medicines; as well as aspects that characterized the state of lockdown, such as the sudden move to online learning, the university closing down, empty streets and classrooms, and people getting sick. In the digital collages, these pictures were often accompanied by words and phrases, such as “la universidad está cerrada” (“the university is closed”), and “nos vamos a online” (“we’re going online”). Unsurprisingly, this category generally captures the negative experiences, stress, and discomfort produced by the social, political, and health-related issues that characterized 2020. The second category, “politics and political developments”, was generated through elements portraying political tension, change, and the oppression of communities of color and immigrants. The elements pertaining to this category evidence the students’ awareness of the political dynamics around them and, and in some cases, they showcase varying degrees of engagement in political activism. Examples from the digital collages include photographs of Donald Trump and Joe Biden, “I VOTED” stickers, or “vote/vota” (in imperative form), as well as images portraying different aspects of the Black Lives Matter movement and issues around the United States–Mexico border, which were accompanied by phrases such as “El Muro” (“the wall”), “los niños encarcelados” (“children in jails”), and “build that wall”, among many others.

By bringing together the multiple aspects of their repertoires into the assignment, not only could the students showcase their own experiences, but they could also include themselves, as people, rather than as descriptions of people, in their narratives. In one of his written documents, S-9, for example, stated that “poder estar yo personalmente en mi narración es algo muy nuevo para mí y me gustó mucho poder representarme. Admito que era un poco embarazoso poner mi picture pero no es igual hablar de mí que mostrarme a mí. Lo segundo es más poderoso” (“having my voice in my narration, personally, is a very new thing for me, and I really enjoyed being able to represent myself. I admit that I was a little embarrassed to include my picture but talking about myself is not the same as showing myself. The latter is more powerful”)

2. Similarly, the students valued the opportunity to include their relatives through the use of original photographs, instead of through written descriptions. S-13 explained how “me gustó mucho poder presentar a mi madre en este collage. Ella tiene los ojos muy hermosos y mucha bondad que yo no podría describir en palabras” (“I really liked being able to include my mother in this collage. She has beautiful eyes, and so much kindness that I wouldn’t be able to describe it in words”). Statements such as these reveal the value that students ascribe to presenting themselves through a first-person multimodal lens that is focused on showing–telling.

Besides pictures of themselves and their relatives, some of the students included pictures of their new working stations at home, of their bedrooms, as well as of other working spaces. For instance, S-5 included a picture of her car, and wrote: “esta es mi nueva biblioteca con internet: el parqueadero de McDonalds” (“this is my new library with internet access: the parking lot at McDonalds”). In her written narrative, S-5 explained that they do not have reliable Internet access at home, so she would drive to McDonalds and attend her lectures from her car, in the parking lot. She added “cuando mire para atrás estaré muy orgullosa de mis esfuerzos como hispana trabajadora” (“when I look back I’ll be proud of my efforts as a hard-working Hispanic woman”). The possibilities of self-representation afforded by the inclusion of original photographs grant digital compositions (including digital collages and digital stories) a particularly powerful nature: it opens new possibilities for students to portray their lives as they experience them through translanguaging and trans-semiotizing processes, while supporting the reader’s/viewer’s meaning- and sense-making and the co-construction of important aspects of somebody else’s experience. The vulnerability that may come with choosing to share one’s original pictures is rewarded with a more intimate and detailed retelling of one’s story.

Against this overview of the proyectos, I now turn to exploring a few examples of the identity and experience representations generated by the students. The examples showcase how the students critically and creatively orchestrated resources, how they named languages, modalities, ways of knowing, and ways of being, and how the external boundaries among these were flaunted and reformulated through translanguaging.

5.2. Complex Representations of Identity and Experience through Translanguaging

Given the wide array of topics included by the students, I have selected three of the most frequent ones: (1) Voting in the elections; (2) Using bilingualism to serve, to support, and to overcome difficulties during the pandemic; and (3) Enduring and contesting raciolinguistic oppression during (and beyond) the pandemic. Every collage submission included at least two of these topics , and 14 of them included all three.

5.2.1. Voting in the Election

The 2020 election was a central topic in the

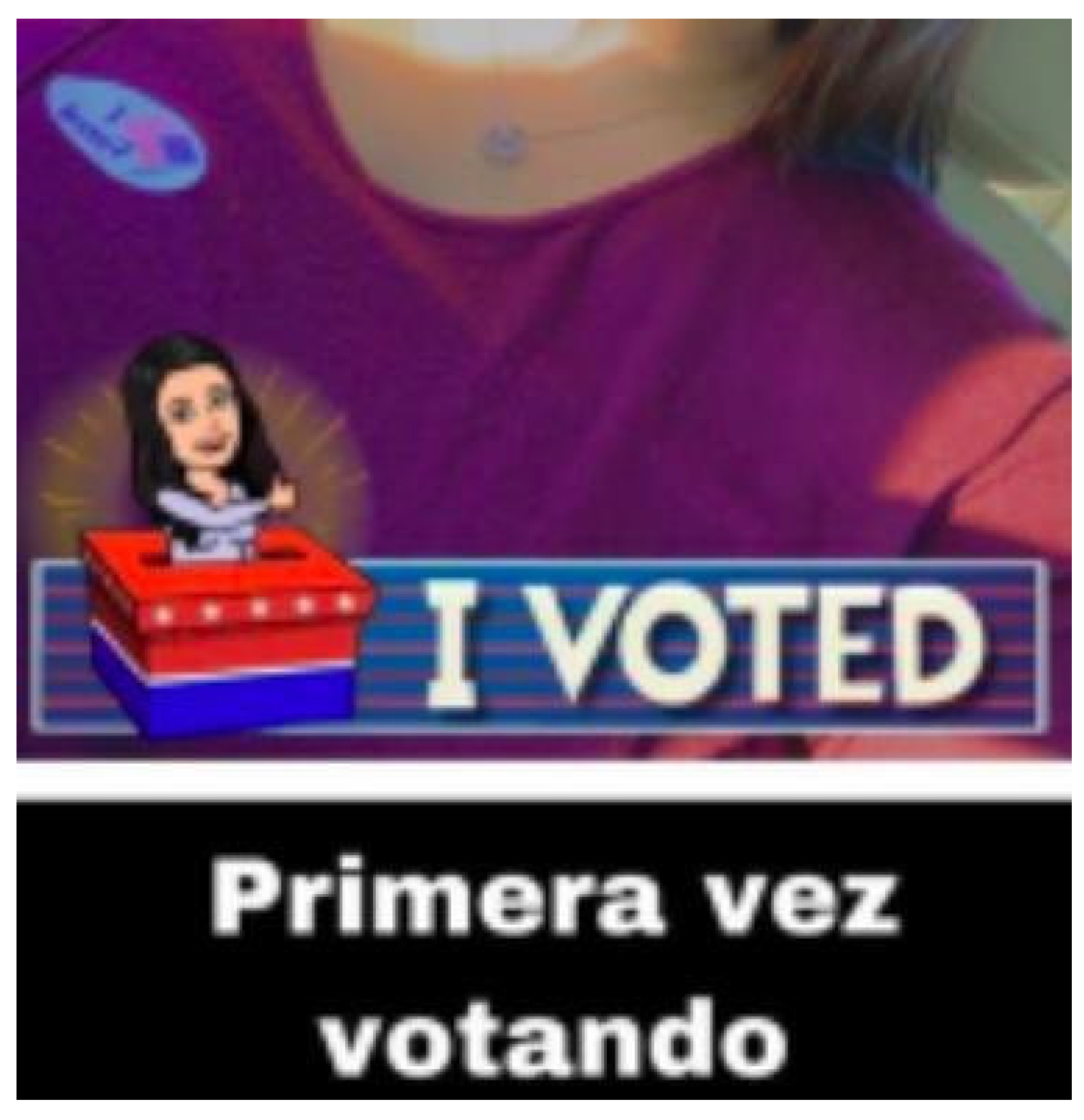

proyectos finales. Many students described how this was the first time they could vote, and they used the opportunity to have a voice in this decisive year. The codes and segments found in the collages included easily recognizable elements, such as stickers and emojis related to voting, political party logos, and the colors red and blue, all of which were positioned in dialogue with one another. A representative example of the theme of voting in the 2020 election was provided in a portion of S-2’s collage, which is shown in

Figure 2 below.

Image 2 includes a combination of strategically arranged elements, each one of them adding nuance to the overall meaning of this section in particular, and to the collage in general. The main axis—which also serves as the background for this portion of the collage—is a selfie displaying S-2’s “I VOTED” sticker (which includes the U.S. flag). The selfie, as she described it in one of her written documents, was taken the day she voted, and she shared it on her own social media immediately after. In the photograph, the student (whose face has been cropped out for anonymity purposes) shows a proud smile expressing her happiness. Additionally, the image includes a filter, which shows a ballot box with the words, “I VOTED”, and a cartoon version of the student popping out of the ballot box with a thumbs up surrounded by a glow, all at the bottom of the selfie, which supports it visually. The last element is placed below this assemblage and contains the phrase “primera vez votando” (“first time voting”) in white lettering. The phrase is inside a black band that frames the perimeter of the entire collage, and which the student used to write short descriptive words and phrases (all in Spanish) that named the different elements she wanted to highlight about the year.

Taken together, these elements co-create a complex message of having voted, of being happy and proud of having done so, and a willingness to share it with the world through a first-person perspective. By using her selfie, S-2 utilizes a form of representation that pushes textual narratives about the self towards nuanced multimodal portrayals. By including that particular selfie, the student brings into her composition an embodied expression of her story that captures the action of voting and her mood at the time. Additionally, S-2 uses written English and written Spanish: the English portion, “I VOTED”, is part of a pre-made element taken directly from a social media platform. By doing so, she is not only mobilizing her linguistic repertoire and integrating (premade) visual elements (which hold their own social currency and meaning), but she is also deploying a complex assemblage of resources in a way that speaks of who she is in the world, as a young woman with a social media presence, and to her understanding of the social value of this form of personal representation. In her descriptive document, the student explained that she chose this picture because she was “muy feliz” (“very happy”) to be able to vote in this important election, and that just including a generic “I VOTED” sticker would not capture this feeling. Besides S-2, many other students included “voting in the elections” as a theme (e.g., see Image 1 above). Another example is S-19’s translingual combination of “YOU/USTED—VOTE” (see

Figure 3, below), where both “you” and “usted” (the former in English and the latter in Spanish) cue the reader to read “vote” in English or in Spanish, respectively—the two meaning the same thing but having different pronunciations.

In this instance, the student draws from his linguistic repertoire holistically to create an original message by using the word, “vote”, as a bilingual axis that allows for its conjugation in both English and Spanish, which showcases S-19’s dexterity at integrating the different features of his repertoire to cater to both bilingual and monolingual audiences alike. By doing so, S-19 brings both languages together and connects them creatively and critically. As he explained in his descriptive narrative, this was a “juego de palabras” (“wordplay”), which allowed him to “mostrar mi bilingüismo y como mi bilingüismo está siempre en mi mente” (“show my bilingualism, and how my bilingualism is always in my mind”). Moreover, S-19 utilized the colors red and blue, respectively, for the words “you” and “usted”. In one of his written documents, the student explained that ‘‘estos son los colores de los dos grupos políticos, el republican y el democratic’’ (“these are the colors of the two political groups, the republican and the democratic parties”). As he explained in one of his narratives, the word “vote” is in white because it is an individual right to vote the color you choose, which underscores “libertad en la votación “ (“freedom in voting”). His chromatic choices are, therefore, another layer of semiotic meaning that were incorporated by capitalizing on the relationship between script and color. This is another example that captures how showing–telling is accomplished through translanguaging not as independent processes, but as a single meaning-making action.

5.2.2. Using Bilingualism to Serve, to Support, and to Overcome

Bilingual Latinxs/Hispanics growing up in the United States often report acting as language brokers and serving as translators and interpreters for their parents and other elders in situations ranging from day-to-day shopping, to visits to the doctor, or reading confidential documents (

Gasca Jimenez 2018). This reality was not unfamiliar to many of the students who completed this assignment, who reflected on how, in 2020, they used their bilingualism to serve and support their families and communities.

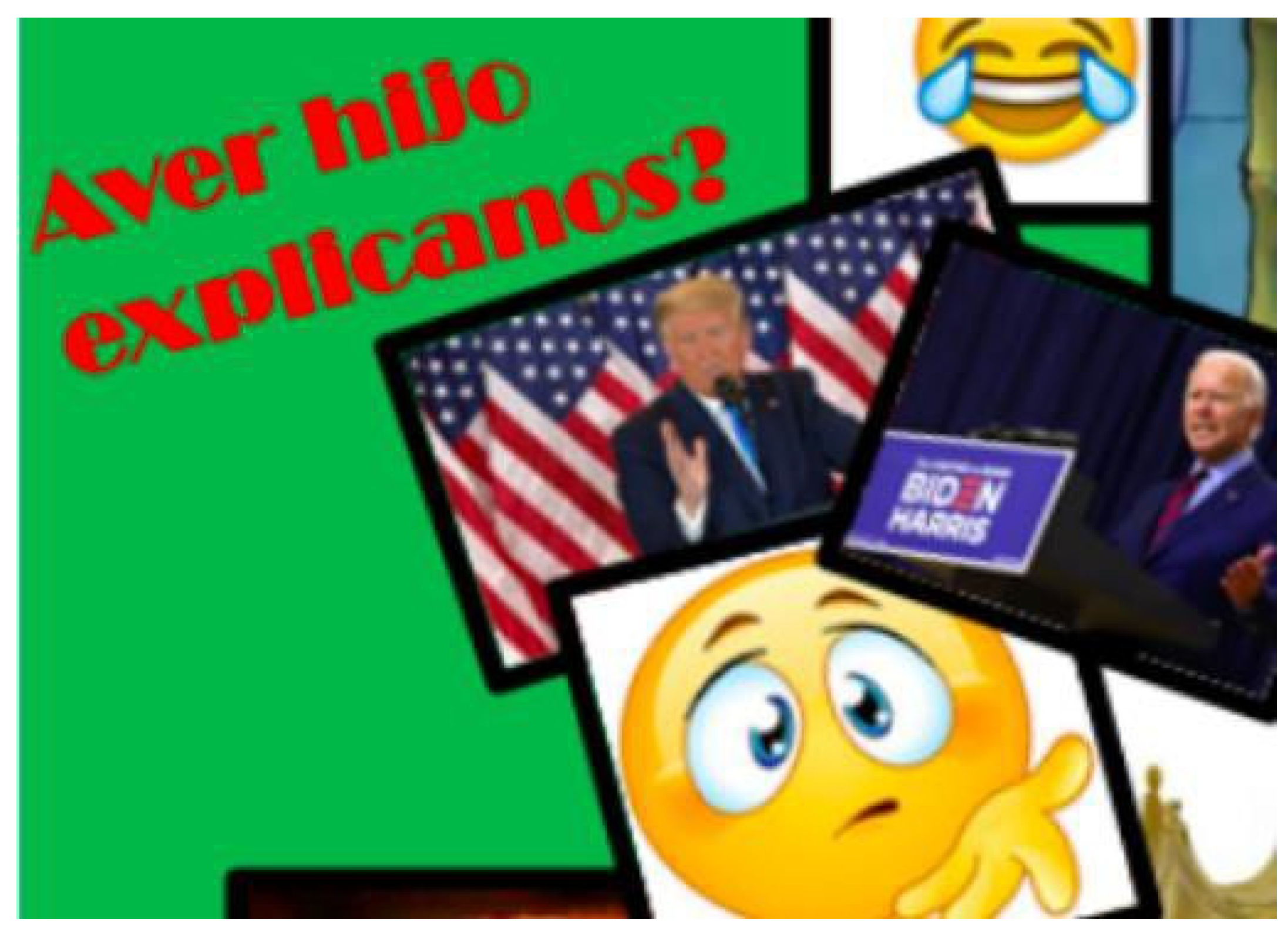

Figure 4 below shows a segment taken from S-9’s collage. In it, the student assemblages four key elements: two photographs (one of Donald Trump and one of Joe Biden, both holding political rallies); one emoji expressing confusion; and the phrase: “Aver hijo explicanos?” (“Okay son, explain it to us?”).

The four elements combine to express the student’s experience of using his bilingualism to translate the political news reported on the television and in the media for his parents. As he described in one of the written documents accompanying the digital collage, the confused emoji captures the feelings experienced by both the parents and the student himself, with the parents not understanding the news, and the student not always knowing how to translate certain ideas. The phrase, “aver hijo explicanos?”, captures the parents’ request to be informed about the news. In his narrative, S-9 explained how “siempre he sido el translator en mi familia porque soy el big brother y mi little sister no habla español como yo. No es fácil traducir para mis papás siempre porque muchas veces son palabras muy complicadas y specialized y yo no las entiendo bien. A veces no estoy muy seguro de que hice una buena traducción ” (“I’ve always been the translator in my family because I’m the older brother and my little sister does not speak Spanish like I do. It’s not easy to translate for my parents all the time because, often, there are difficult and specialized words that I don’t quite understand. Sometimes I’m not sure if I translated them well”).

Moreover, the phrase, “aver hijo explicanos?”, is spelled out through the student’s home literacy as opposed to the normative, “a ver”. In one of his narratives, he explained how “en la clase aprendí la regla de escribir ‘a ver y haber’ como ‘let’s see y have’ pero mis papás no fueran a la escuela y no sabían esa regla so lo escribe como mis papás” (“in class I learned the rule “a ver and haber” meaning “let’s see and have” but since my parents didn’t go to school and don’t know that rule I wrote it like my parents would”). In this way, S-9 is mobilizing grassroots literacies and trans-semiotizing practices (as proposed by Blommaert and Lin, respectively) in a curricular space that values such bottom-up processes that build on local/vernacular ways of knowing and acting, and, in this case, promoting them to represent the voices and literacies of his own parents. Translation falls within the range of the multilingual practices at work during translanguaging (e.g.,

Baynham and Lee 2019), and this collage segment captures the feelings experienced by the student during language brokering in this particular context. The message conveyed here capitalizes on the insecurity felt by the student while relaying important information to his parents who were navigating this complex space, and in doing so, S-9 reflects on the emotional side of translanguaging, an aspect he captures through an emoji in his collage.

5.2.3. Oppression and Resilience

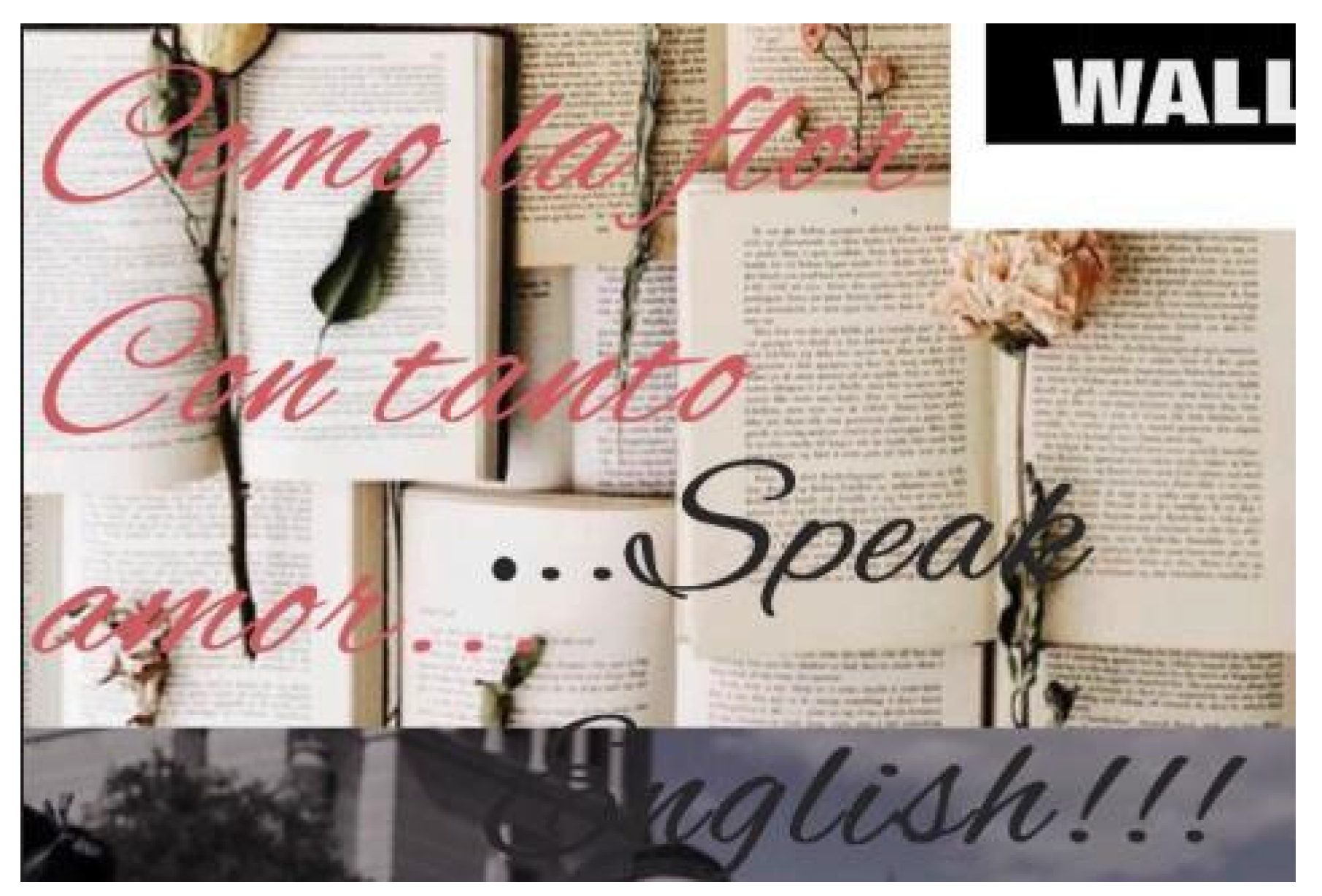

The last examples included herein showcase representations of instances of the raciolinguistic oppression and resilience experienced by the students, many of which are not unique to the year 2020, but, as explained by many of them (e.g., S-1; S-4; S-7; S-15), seemed to “hit differently in the tension of year 2020,” as was reported by S-4 in her document describing the meaning of the collage. While regrettable, it not uncommon for Latinx/Hispanic students to report being told to “speak English”, to have their linguistic legitimacy or functionality questioned by teachers and peers, and to have their language abilities problematized in different contexts. A portion of S-5’s digital collage (

Figure 5 below) illustrates how a student engages in complex translanguaging processes to represent her experiences of oppression, while bringing into focus aspects of her cultural identity and her knowledge as a Hispana.

As was exemplified earlier on, the semiotics of color played an important role in many of the digital collages. Some students, in fact, used color and specific filters to create moods around their collages. S-5’s digital collage is a great example of this, as it incorporates different shades of pink and gray as a chromatic axis. In the mid-section, on the left side of the collage, she included the assemblage cropped out in Image 5. In this section, S-5 shares how, as a bilingual Latina, she feels observed and judged by others. To achieve this, she used the phrase “como la flor con tanto amor’’ (“just like the flower, with so much love…”) in pink (her favorite color, as she described in one of her written documents), followed by ‘‘…Speak English!!!’’ (in dark gray, a color she described as sad, and which she does not like). The phrase in Spanish is the opening line of a popular song by the 1990s Tejano music icon, Selena (who she referred to in her narrative as her favorite artist). These phrases are placed against a background of open books and withering flowers. The withering flowers represent the flower from the song S-5 describes, and she states that “las palabras de la canción continúan ‘se marchitó’ pero como me interrumpió alguien mientras la cantaba, las mostré como fotografias en el fondo ” (“the lyrics go on to say ‘the flower withered’ but since I was interrupted while singing it, I showed it through pictures instead”). This process constitutes another powerful example of showing–telling, where S-5 engaged in meaning- and sense-making beyond words through trans-semiotic flows. To that end, she mobilized her linguistic knowledge and her cultural knowledge, and presented them in ways that show an inherent mutual constituency.

S-5, when describing the meaning of the collage, explains how that a portion of the collage depicts her as a young ‘‘hispana’’ singing her favorite song and being herself, but always being interrupted by someone who demands she changes who she is. She emphasizes how, even though you may be thriving, somebody will feel entitled to demand that you change and that you adapt to them: “La gente siente que puede exigir el idioma en el que hablo, en el que canto y en el que siento. Mucha gente quiere interrumpir quien yo soy como Mexicana y quieren que sea diferente, inclusive si eso significa que yo esté triste y gris” (“people feel that they can demand what language I speak, what language I should sing in, and what language I should feel in. Many people want to interrupt who I am as a Mexicana and want me to be different, even if that means that I am sad and gray”). She added, “I chose to use my favorite line because in America, for Hispanos like me, we are told to shut up and speak English when we start singing. When we start shining somebody will always try to shut us down. That is why I added the ‘build that wall’ sticker close to these sentences. It’s all interrelated.” She continues to explain how ‘‘los libros del background representan como leer en silencio puedo hacerlo en español y nadie me interrumpe ’’ (“the open books in the background represent how I can read quietly in Spanish and nobody will interrupt me”).

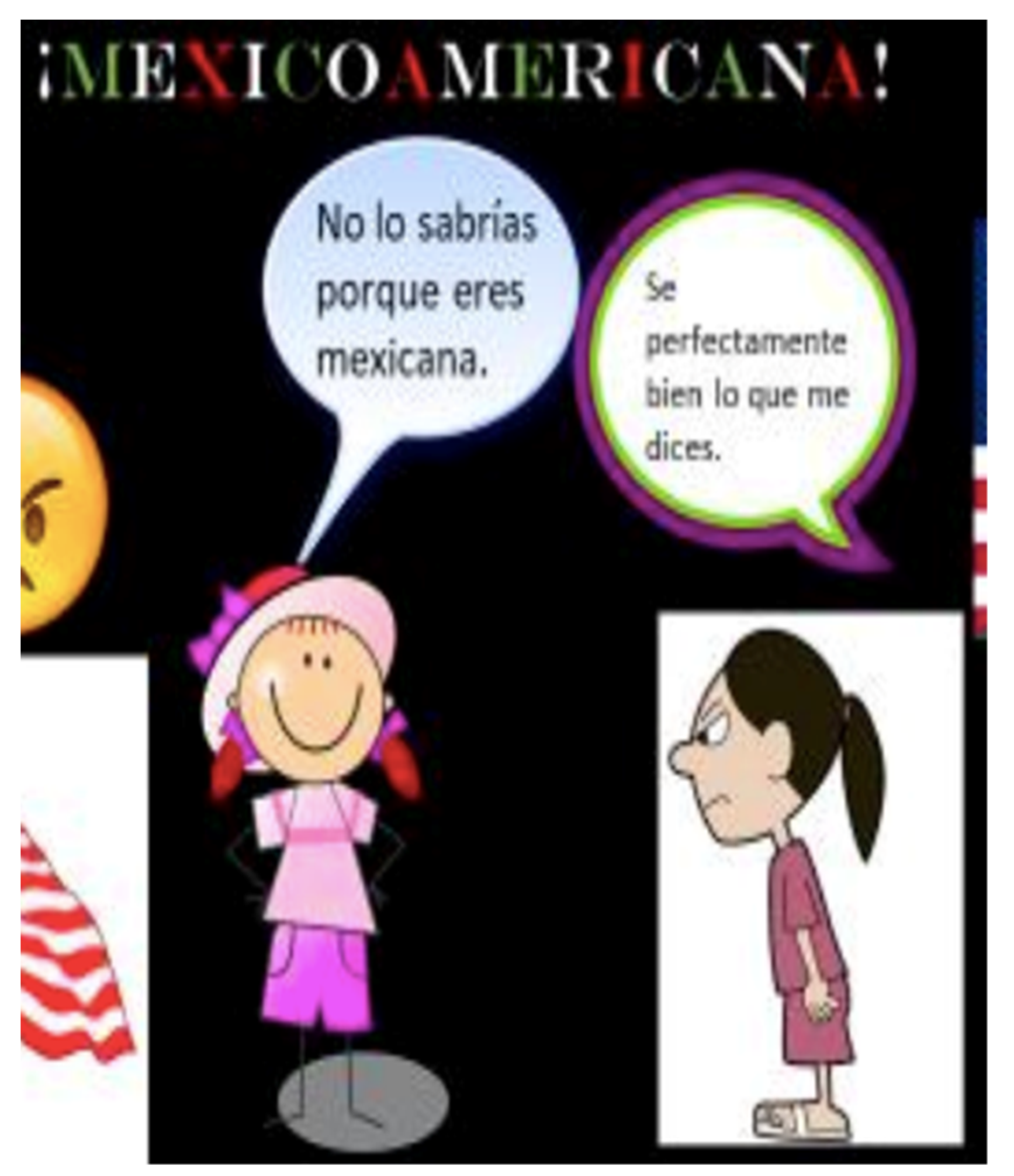

In this part of her collage, S-6 show–tells how she feels as though she is often considered less intelligent or is mocked by some people. In one of her documents, she explains: “desde la infancia cuando era una niña muchas person as piensan que no puedo entender algunas cosas. Es posible que no entiendo algunas palabras pero síentiendo las ideas y la realidad ’’ (“since I was little, many people have thought that I couldn’t understand some things. I might not be able to understand some words but I do understand ideas and reality”). Similar representations of questioning, problematization, and marginalization appeared in 13 (of 22) collages, with other examples including phrases such as “you’re not from here” (S-16) and “Go back to your country” (S-9) (both in English, which highlights that these calls mostly come from English-speakers), alongside responses such as “Mi alma no escucha tu ignorancia” (“My soul doesn’t listen to your ignorance”) (S-16), and “USA = mi casa” (“USA = my home”) (S-9), which showcase the contestation of and resistance to racist sociocultural impositions.

Lastly, another instance of (racio)linguistic oppression and resilience was found in S-6´s collage (shared in Image 1, above, and cropped out in

Figure 6 below). This portion of the collage shows two girls, one with a smiley face, dressed up in pink clothes, and saying, “No lo sabrías porque eres mexicana.” (you wouldn't know because you're Mexican). Her interlocutor is another girl (who represents S-6) with dark hair, an angry face, and a tense body posture, who is clearly upset by the other girl. S-6 says, ‘‘se perfectamente bien lo que me dices’’ (“I know perfectly well what you´re saying”). Across the top, one can read the word “MEXICOAMERICANA” (“Mexican American female”), which uses green, white, and red, the colors of the Mexican flag, as an identity marker in the lettering.

6. Showing–Telling through Translanguaging: Some Implications for Supporting Historically Underserved Multilinguals

6.1. A Few Notes on Showing–Telling

Against the general background of the goals and objectives in heritage language education, this proyecto final was designed to provide students with the space, tools, and affordances to develop complex narratives of their experiences in the year 2020 as they digitally assembled snapshots of their individual stories and their identities in an interplay with the broader social events and collective dynamics. Herein, as illustrated, narrating is best captured as showing–telling: a way of sharing stories that hinges on the student’s commitment to storytelling through and beyond words, as well as on their abilities to navigate decision-making critically, creatively, and effectively by means of emergent multiliteracies and grassroots practices. The idea of showing–telling captures the inseparability between written words and other visual elements in these digital collages, as the students weave visual elements, including written words, pictures, colors, etc., and critically and creatively arrange them in a given space, which results in a digital composition/narration.

Importantly, the spaces between showing and telling are not seen as cracks or divides, but as flexible organic interfaces that interact with one another as the composer and the reader/viewer navigate the proyecto and bring their own knowledge and intuitions to the fore. This is enabled by the individual’s capacity to make sense and to make meaning by attending to the ecological relationships within and outside of the collage. For the composer, this proyecto offers spaces to tell by visualizing, and to tell by writing, and to mesh both in ways that reflect their individual abilities and worldviews; for the viewer/reader, the proyecto becomes a space for learning, where one must be guided by their translanguaging instinct, and where one is required to actively view/read and interpret.

This assignment emerged as a translanguaging space where students were encouraged to show–tell their experiences through multimodal visualizations of their universes, utilizing their voices through this wider ecological lens, and thereby reflecting the trans-semiotic flows at work in everyday communication, as well as the types of literacy practices that academic spaces often problematize as illegitimate. This ecological multimodal understanding of composition seeks to support the students’ voices and to amplify them by centering a first-person approach to meaning-making. Therefore, composition is not conceptualized as something to codify through writing, and particularly not by privileging the standardized writing practices of monolingual people who have enjoyed sustained access to education. In this way, digital composing is pushed towards broader and more complex understandings that reflect the social semiotics and the practices characterizing our world today.

6.2. A Multidocument Submission for a Multiliteracies Proyecto

It bears considering that the three documents included in the submissions speak to one another, expand one another, and complement one another, becoming mutually constitutive elements that reflect a transmediated nature. While a detailed discussion of their mutual constituency falls outside of the scope of this paper, attention must be brought to the trans-semiotic flows between them, and their literacy- and criticality-building powers, which are all aspects of translanguaging about which we know very little. In fact, much of the value of this assignment, as a proyecto de composición digital, lies in its nature as a whole, and specifically, it lies in the interwovenness of its different components, their objectives, and the forms of literacy and meaning-making that they promote. With regard to this issue, in the written documents, the students are tasked with identifying what portions of the digital collage to translate into words, and then, how to language those complex ideas through linguistic practices that may or may not (that is up to the student) adhere to the boundaries of the named languages. These and other choices seek to encourage students to adopt a metaperspective, and to reflect on why they chose to show–tell their story the way they did, and how they did it, which, at times, leads to the addition of new layers of nuance.

6.3. Rethinking Academic Expectations and Practices from Below

This proyecto offered the students different possibilities for assembling ideas and for presenting them on their own terms, and without the restrictions of the named language boundaries and the academic ideologies developed through elite monolingualism. The creation of the collages required the mobilization of sophisticated understandings of the cultural and social conventions, which were all orchestrated into a complex bricolage that students were already familiar with. Several students mentioned that the creation of the digital collage was similar to creating posts for some social media platforms. For example, S-17 stated: “it [creating the collages] felt like a big snapchat of this $hit year,” and S-3 mentioned how “era un poco raro editar mis fotografías como un post de instagram pero para un trabajo de la clase. Eso si es algo que ya sabía hacer pero se sentía tan fácil y natural que pensé que estaba hacindo algo incorrecto” (“it was a little weird to edit my photos like an Instagram post but for a class assignment. It is something I knew how to do already but it felt so natural that I thought I was doing it wrong”). The integration of “unacademic” practices into the classroom was an important component of this assignment, as it sought to legitimize the students’ home literacies/grassroots practices as powerful and meaningful, and thus appropriate.

A key element of curricular design through a translanguaging lens is to allow for—and to even promote—the inclusion of linguistic and cultural processes that are often construed as not academic enough, or as void of appropriate communicative value (

Canagarajah 2011). In the context of heritage, community, and minoritized language populations, the promotion of these subaltern forms of meaning-making may promote new ways of thinking about the value of flexible multilingual practices, which leads to empowerment and self-value (

Prada 2019). In line with this, digital media and the skills required for much of this assignment, the translanguaging practices at work, and the student-led nature of the

proyecto as a whole, can be seen as intrusive in many educational contexts. This is perhaps because digital media has developed mostly outside of educational settings, it maintains a strong connection to popular culture and leisure, and it is used by youths in their daily nonacademic lives. I agree with Sutherland et al.’s (2004) idea on digital tools in education, and I consider that much of the value of this assignment lies precisely in the fact that digital tools may lead pupils to engage in bottom-up movements that could encourage them to question the nature of academic appropriateness and the values it promotes, which could serve as tools that contribute to dismantling the top-down understandings of academic discourse.

This reformulation of what counts as real literacy practices in academic spaces is in keeping with how transcending the imagined boundaries of named languages may be seen as unacademic and inappropriate for the university setting (

Prada 2021a,

2021b). Thus, curricular spaces, such as the one described herein, where the undoing of these sociopolitical boundaries is accepted as part of the student’s rightful agency and choice-making, may contribute to the democratization of language education, the decolonization of literacy in the heritage language classroom, and the reformulation of literacy as a whole—as is already captured in the multiliteracy and new literacy approaches. In the move from theory to practice, and from practice to theory, translanguaging offers a vehicle that cuts across the ideological, theoretical, and applied aspects that stimulate a reformulation away from the monolingual written-word-centered focus of language education, and that privileges the students’ voices and histories. This is an issue that is of the essence when working with multilingual students whose linguistic repertoires reflect historical institutional neglect through the disregard of their multilingualism.

6.4. Towards Sustainable Change in Composition Courses for Racialized Language-Minoritized Multilinguals

As I see it, heritage language pedagogues that seek to substantively change the educational models to serve their students must produce curricularizations of meaning- and sense-making that support the students’ profiles as multilingual people, with complex histories and real-life valuable skills, by conceptualizing the organic growth of the students’ repertoires, abilities, and worldviews as evidence of “learning” beyond the verbo-centric (i.e., that which conceives of words and named languages as central) conceptions of the target language grammar. As I have discussed elsewhere, building on Ofelia García’s ideas (see

García 2009), the inseparability of language and content is a problematic element in language education (

Prada 2021c), particularly in classrooms populated by historically underserved students. Showing–telling, as a pedagogical strategy, addresses this issue in a number of ways. Students who historically have not enjoyed educational support across the various named languages that they are socially expected to be literate in are deserving of curricular spaces that recognize this systemic failure and that meet them where the system has left them.

An important (and often ignored) part of this equation is how HSs are expected to use the heritage language in the same way as monolingual individuals. Considering the diverse profiles that this population bring to the language classroom, heritage language courses must be designed with that diversity in mind, with dedicated spaces where all ideas and experiences become classroom contributions, and with efforts being geared towards separating the value of storytelling (e.g., their coherence, their cohesion, their structure, the robustness of their argument, and the effectiveness of the strategies used to relay the details and create different dimensions) and the language objectives of the course. Pedagogues seeking to support their students, and to support them linguistically and culturally, must develop curricula that center this differentiation. Showing–telling strategies are an appropriate pathway towards democratizing some types of heritage language courses, which, in this case, was a composition-intensive course.

7. Conclusions

On the whole, the digital collage

proyectos finales provided a wealth of insight into the nature and value of translanguaging in this curricular context, which furthers our understanding of the affordances of translanguaging in the heritage language classroom, and which contributes to broader discussions around translanguaging in general through the notion of showing–telling. In this article, I have engaged with the idea that, in the curricular context of language courses specifically designed for students whose lives and literacy profiles have been shaped by the normalized forms of educational neglect (

Prada 2021b,

2021c), the imposition of logo-centric monolingual approaches may be considered yet another form of neglect that becomes naturalized through the curricularization within “heritage” classrooms and programs. Language courses “for HSs” must serve as strongholds for curricular change, where innovation is driven by the students’ lives and experiences. It is, therefore, our role as course designers and teachers to shape these spaces into culturally and linguistically sustaining ones, where new understandings of literacy are forged beyond the institutionalized standards. To that end, and grounded in the

proyectos finales developed by my students, I have advanced the idea of digital composing as showing–telling by exploring examples of complex meaning- and sense-making through a translanguaging lens that recognizes how multimodality, multiliteracies, and trans-semiotizing processes are at the heart of this pedagogy.

To finish, a word of caution. As technological changes continue, we must wonder how the new forms of literacy that emerge from interacting with these advances can feed into our curricular designs, since those are the types of literacy that will continue to shape composition and rhetoric in the future. Because of this, the very nature of academic writing, and of composition for academic and professional purposes, must change in order to reflect new meaning- and sense-making possibilities. Over time, the range of elements found in digital compositions will continue to broaden, from words and phrases, to the increasing inclusion of more visuals, images, videos, 3-D imaging, sounds, and virtual reality, as well as interactive elements, such as links, searchable tables, maps, and other virtual spaces. As we incorporate these elements into our pedagogies, we must remain open to furthering our understanding of composition to integrate new possibilities for meaning-making and storytelling, such as the use of wearable and sensorial tools. Critically, the curricularization of digital composition must not be guided by the same principles of appropriateness and rigidity that have naturalized the educational opportunities of middle- and upper-class individuals from privileged backgrounds. With this in mind, efforts to redefine concepts and theories concerned with digital composing must integrate understandings of how accessibility, privilege, and gatekeeping thrive within academic writing and composition discourses and classrooms; in so doing, we will be able to carve out a reformulation of digital composing as a decolonizing space.