1. Introduction

In second language (L2) writing contexts, corrective feedback (CF) has widely evidenced affording statistically significant positive effects (

Storch 2010) while revising and creating new writing pieces (

Ashwell 2000;

Ferris and Roberts 2001;

Ferris 2006;

Bitchener and Knoch 2010;

Shintani and Ellis 2013). Teacher comments can be equally conducive to writing and language development (

Bitchener and Knoch 2010) when learners’ accountability for self-correction is upheld (

Furnborough and Truman 2009). To this effect, some studies have found that indirect written CF is to be favored over direct corrections (

Hamel et al. 2017;

Valentín-Rivera 2016,

2019). However, a consensus regarding the most effective type of indirect CF (e.g., underlying, color coding, linguistic coding, metalinguistic cues, and accessing corpora) has yet to be reached (

Cotos 2011). Perhaps the wide-ranging degrees of efficacy of varied strategies of indirect written CF are condition-dependent (e.g., learners’ linguistic background, proficiency level, motivation, previous experience receiving written CF). This lack of consensus could also be explained by the fact that indirect written CF has not been studied as much as direct CF has (

Kang and Han 2015;

Shintani and Aubrey 2016). The benefits of traditional paper-based written CF have transferred to L2 writing embedded in digital media (

Elola and Oskoz 2016). In fact, digital CF may yield greater uptake and learning opportunities. This may be due to its dynamism, accessibility, and perpetuity (

Campbell and Feldmann 2017).

Not all research focused on technologically delivered written CF, however, reflects multimodality. For instance,

Shintani (

2015) and

Shintani and Aubrey (

2016) explored the efficacy of immediate and delayed focused (i.e., hypothetical conditional) indirect CF, which was delivered via track changes. A positive impact of CF in both studies was observed, especially when comments were provided as learners composed their texts. Additionally, CF prompted noticing (

Shintani 2015) and advanced the learners’ grammar development (

Shintani and Aubrey 2016). Despite the contributions of these two highly innovative and novel studies, the adoption of track changes reflects a monomodal communication, as it only involves text to deliver feedback. Contrastively, multimodality comprises diverse semantic modes (

Elola and Oskoz 2016;

Jiang 2018), such as text, graphics, sound, images, etc. The incorporation of multimodality in CF has yielded high success rates of error correction (

Ducate and Arnold 2012), as L2 learners find comments delivered by varied semiotic means to be clear (

Harper et al. 2015;

Elola and Oskoz 2016) and memorable (

Harper et al. 2015). These positive findings are further explored in the section below.

1.1. Multimodal Written CF: Screen-Casting and Word Processing Tools

The positive impact of multimodal written CF intertwined in screencast within L2 classrooms has been observed (e.g.,

Ducate and Arnold 2012;

Elola and Oskoz 2016;

Harper et al. 2015). Being one of the first studies that examined the effects of digital multimodality on written CF provision,

Ducate and Arnold (

2012) compared the efficacy of digital, indirect feedback delivered by screen-casting (i.e., audio and video) versus the comment function of word processors. The participants were 22 university students enrolled in a fourth semester L2 German class, who completed four writing assignments of different topics and genres during the 13-week semester. For each assignment, the participants submitted two drafts and were expected to incorporate the instructor’ indirect feedback (i.e., in the form of error code along with short explanations) into their final drafts. At the end of the semester, they also filled out a survey eliciting their preference. Overall, the multimodal feedback via screen-casting was found to be associated with higher success rates of error correction than the comment function. In addition, the participants overwhelmingly reported their preference for screen-casting over the comment function in the survey responses, as the multimodality feedback afforded them more detailed and learner-friendly information. Similarly,

Harper et al. (

2015) explored whether the impact of CF can be boosted by multimodality (i.e., image and audio) by working with 38 learners of German and Spanish who completed a writing task and revised their drafts based on individualized screencast comments. A questionnaire and a semi-structured interview were used to collect participants’ perceptions concerning clarity, affective impact, and accessibility. The results showed that screencast CF was well received as learners reported getting more meaningful comments, having greater access to an expert (i.e., their tutors), and amplifying their affective involvement, thus engaging more deeply in the revision process. The latter was because they could identify the tone of the comments. Similarly,

Elola and Oskoz (

2016) investigated how different computer-based resources affected instructors’ CF provision and whether the communicative modality (i.e., spoken vs. written comments) impacted learners’ revisions. Four L2 learners of Spanish from an intact advanced writing class at a U.S. university on the East Coast partook in this study. In this course, six writing tasks were assigned (i.e., two essays per three genres: expository, argumentative, and narrative) and two rounds of revisions per essay were expected, thus crafting three pieces per composition. To facilitate this, the instructor provided comprehensive indirect multimodal CF on content and form through comments shown by track changes (written comments) and screen-casting (spoken comments). For the one narrative essay interlinked with the study, written CF was provided to two participants in the first round of comments, while the other two subjects received oral CF. In the second round, the order was reversed. Overall, both communicative modalities impacted the amount and the quality of the feedback provision. Spoken comments (screencast) on content, structure, and organization were more detailed and longer, whereas written comments on form were more explicit. These approaches matched learners’ preferences. Interestingly, the participants made a similar number of revisions regardless of the communicative modality in use.

1.2. Using Eye-Tracking Techniques to Measure Learner Noticing in L2 Written CF Research

Though prior research on digital multimodality in L2 written CF reported its overall benefits, it remains under-researched how learners’ engagement with the feedback is associated with the effects of multimodality. Particularly, noticing has been considered a key factor closely tied to the efficacy of written CF among the L2 written CF research grounded in the cognitive-interactionist approach to L2 learning. According to

Schmidt (

1995), noticing is a surface level of focal attention, referred to as “conscious registration of the occurrence of some event” (p. 29). Because of the limited storage capacity of working memory (

Baddeley 2003), noticing is argued to be a necessary condition for L2 learning in that the target features in the input must first be noticed before being available for further processing (

Schmidt 1993). Despite the important role that noticing plays in L2 development, the empirical research exploring the extent to which learners noticed and reacted to the written CF has been small (

Smith 2012;

Han and Hyland 2015;

Ma 2020). This line of research is especially insightful in that it could not only uncover learners’ engagement and processing with the feedback but also deepen our understanding of the potential benefits of written CF for L2 development.

Among the current L2 written CF research, four main methods have been employed to measure learner noticing (

Smith 2012;

Ma 2020): learner uptake in the subsequent writing task(s) following written CF, concurrent verbal reports (e.g., think-aloud protocols), retrospective verbal reports (e.g., stimulated recall interviews), and eye-tracking techniques. Of relevance to this study, the research using eye-tracking techniques to investigate L2 written CF is reviewed below.

Smith (

2010) was the first empirical study evaluating the use of eye tracking as a tool for exploring whether written recasts were noticed in an L2 synchronous computer-mediated communication (SCMC) environment. Eight EFL learners participated in the study by re-telling a story to the native-speaker researcher in English through synchronous written chats. During the process, they received intensive recasts on the errors they made, and their eye movements were recorded by an eye tracker. After the online chats, all participants independently completed a timed writing task to retell the same story. The study reported findings consistent with prior research: learners fixated on more lexical recasts than grammatical recasts, and all the recast items resulting in successful uptake seemed to be noticed by learners and used with slightly more accuracy in the post-chat writing than those without uptake. Building on this pilot study,

Smith (

2012) further examined the possibility of employing eye tracking to measure learners’ noticing of corrective recasts during text-based SCMC by increasing the participant pool (N = 18) and adopting a more rigorous research design (pretest/immediate posttest/delayed posttest). He specifically compared the eye-gaze data with those of a stimulated recall on each recast item the participants received to examine whether the two measures resulted in similar findings. Overall, the results confirmed the effectiveness of both measures (i.e., eye tracking and stimulated recall) as good indications of noticing in the written corrective recasts during SCMC. More importantly, the author emphasized the potential value of using eye tracking to explore the nature of noticing in L2 written CF research, since it could uncover what learners attend to in written CF in a way not interfering with their cognitive processing. Following the conclusions drawn by prior research,

Shintani and Ellis (

2013) employed the combination of eye tracking and stimulate recall to explore how six ESL learners attended to direct corrective feedback (DCF) versus metalinguistic explanation (ME), as a supplement to the main study that compared the effects of the two types of written CF on learners’ acquisition of the indefinite article in English. Three of the participants received the DCF treatment (i.e., the DCF group), while the others received the ME treatment (i.e., the ME group). The eye-tracking machine was used to track the participants’ eye-gaze movements to identify where they fixated on the feedback/errors as well as the duration of their fixations. The results showed no difference in the noticing that the two groups paid to the feedback/errors. However, the relatively short duration of the fixations of the participants in the DCF group suggested that they may not engage in a deep processing of errors, thus failing to develop an understanding of the rules/patterns. While the results of the eye-tracking data served as a mere supplement to the main findings of the study, the authors explicitly acknowledged its contribution, as it provided valuable information regarding the participants’ engagement with the two types of feedback.

The eye-tracking technique was employed as the measure of learner noticing in this study primarily because of two considerations. First, it enables us to have an objective, online record of learner attention or noticing by tracking the path of their eye movements across the screen and observing the frequency and the duration of the eye fixations when they attend to the feedback. As

Smith (

2010,

2012) explained, though the context is necessary for interpreting the eye-tracking data, the path of learners’ eye movements may tell us where their attention is concentrated, the frequency of their eye fixations possibly indicates the areas they show interest in, and the duration of their eye fixations likely suggests the amount of processing time they need for certain items. Additionally, while the application of eye tracking has a short history within the field of L2 written CF and the empirical evidence is limited, the existing observations suggest overall effectiveness in its use as an instrument for measuring learner noticing, as evidenced by the brief overview of the relevant research above.

1.3. Aims and Research Questions

As reviewed above, the previous studies that investigated the effectiveness of digital multimodality in L2 written CF directly offered learners comments without providing any training on how to approach them. They also did not examine how learners attended to the multimodal feedback or to what extent their noticing of CF was associated with the success rates of error correction. This is of significance since it would deepen our understanding of the potential benefits of multimodal feedback for learners’ linguistic and writing development. Building on prior research, this descriptive study focuses on Spanish, a scantly researched target language, and attempts to achieve two goals. First, we aim to better understand the impact of two multimodal resources as means to prepare learners to cope with indirect CF (i.e., codes and metalinguistic cues). It is crucial to emphasize that in this study, multimodality is observed in two different artifacts: (1) an audiovisual training on approaching CF and (2) a soundless videos carrying individualized CF. As such, each of these artifacts respectively combine two modes: sound and image, and text (via track changes) and image. Second, we attempt to trace any relationship between noticing and accurate revisions via eye-gaze activity afforded by eye-tracking techniques. The first aim responds to the call to unveiling the interface between tools that mediate written, graphic, and oral input “in how feedback is constructed and received” (

Chang et al. 2017, p. 417), whereas the second goal corresponds to the same scholars’ observation to “strive for a context-rich description of e-feedback activities” (p. 406), especially by utilizing devices such as screen-casting, eye tracking, and keystroke logging technologies. These aims are embedded in the following research questions:

- (1)

What is the overall success rate of revisions after receiving guided CF (i.e., codes and metalinguistic cues) embedded in multimodal resources? What types of errors (i.e., lexical, spelling, verb-related, missing word, agreement) are more successfully revised?

- (2)

Does noticing measured via eye fixation account for accurate revisions? If so, how?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and the Learning Context

The pool of participants consisted of three L2 learners who were part of the language sequence of Spanish (N = 3) at a public Midwestern university in the U.S. Two of them (one female and one male) were enrolled in Spanish III, while the other one (male) was a Spanish IV student at the time of data collection.

2.2. Spanish Language Sequence and In-Classroom Writing Practice

The four lower-level Spanish courses (I–IV) in the language sequence, which account for the foreign language requirement, are conducted entirely in the target language and are embedded in a core-communicative approach. Approximately three to four sections per course are offered per semester. Classes include speaking, listening, reading, writing, and audiovisual exercises completed individually, in pairs, small groups, and as whole class activities.

Concerning writing, two compositions per semester are assigned to primarily recycle the covered lexical, cultural, and linguistic content. For Spanish III, composition #1 requires students to write about common rituals, habits, and traditions in Spanish-speaking countries. The preparation stage is completed at home while responding to a list of guiding questions to brainstorm ideas, which can be subsequently consulted during the in-class composing phase. The revision process is also assigned as homework. Students must turn in a second draft for composition #1, but the revisions for composition #2 are optional. The latter focuses on a biographical sketch of a personal hero. Similarly, Spanish IV discusses ‘entertainment’ and compares different means of entertainment throughout time (e.g., going to the theater vs. streaming a movie at home (composition #1)). Composition #2 focuses on a comparison between rural and urban life.

Additionally, after talking to the two coordinators in charge, who create all syllabi, teaching materials, tests, and assignments, it was found that very few students decided to engage in the revision process of the second composition, regardless of the course, as it is optional. Those who opt to engage in this process may earn up to ten additional points for their final grade. Furthermore, instructors provide the CF of their choice, which usually consists of color-coded underlines, that is, instructors underline problematic portions of the text with different colors that convey the nature of the error (i.e., green reflects conjugation errors, while blue displays vocabulary-related issues). Neither the body of instructors, usually consisting of six to eight graduate teaching assistants, nor the students receive any formal training on efficiently providing written CF or revising; although students receive comments, the types of CF adopted by the instructors may vary significantly and are not explicitly addressed in class. Thus, students receive no information on the reasoning behind the selected feedback strategy or examples on how to fix these inaccuracies.

2.3. Data Collection Process

The data collection process (see

Table 1) was completed in two sessions at the office of one of the researchers. In the first session, the three participants individually watched the three-and-a-half-minute long soundless video entitled

“love at first write”1. The common soundless video was used for consistency in the content of the writing task. Afterwards, 20 min were allocated for participants to narrate the story in a Microsoft Word document. Narrating was selected given the participants’ overall familiarity with the genre, regardless of the class they were enrolled in (i.e., SPAN III and SPAN IV).

The follow-up session for participants to revise their drafts took place a week later. First, they watched a 10-min YouTube audiovisual tutorial on how to approach written CF (see more details below), and then received written CF through a soundless, personalized YouTube video (the two videos are described in the next sub-section). After reviewing the CF, participants were given 20 min to revise their compositions. The eye-gaze activities of each participant when watching both YouTube videos (i.e., the tutorial and the soundless personalized CF provision) were recorded with a Gazepoint 3 HD eye tracker.

2.4. Feedback Treatment

2.4.1. YouTube Audiovisual Tutorial

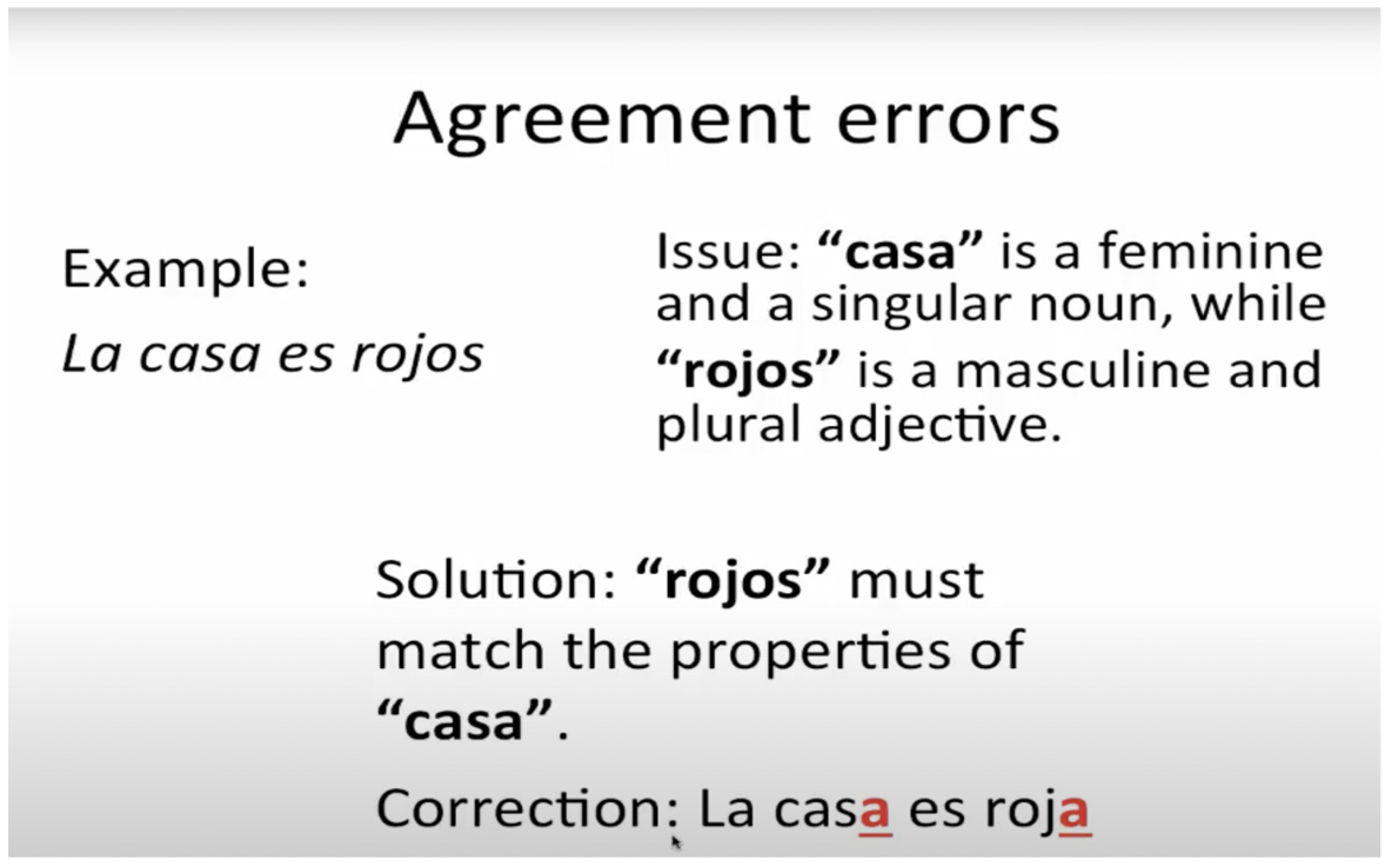

To assist participants in understanding the written CF they were about to receive (i.e., codes + metalinguistic cues), especially considering the lack of writing and feedback instruction in the language classes they attended, the researchers created one audiovisual tutorial delivered through a PowerPoint presentation (with 10 slides). The audiovisual component focused on a general introduction that stated the purpose (slide #1), in addition to the explanation of five common types of language-related errors in the target language (presented from slide #2 through slide #10), as seen in

Table 2. Three out of the nine slides that featured the linguistic-related content presented agreement, missing word, and spelling errors, with each type being shown in one slide at a time. However, verb- and vocabulary-related errors were sub-divided into four and two categories respectively, since errors in Spanish related to these two matters tend to represent a higher level of difficulty due to the different linguistic requirements that need to be met, such as tense, aspect, and mood in the case of verb matters. These sub-divisions were incorporated into the tutorial as six additional PowerPoint slides. English was used in the tutorial to ensure the comprehension of the content.

The explanations of each error followed the same sequence: an example illustrating each error was first introduced, followed by an explanation of the root of the issue and alternatives on how to solve the inaccuracy along with the correction itself. Additionally, some information, such as key words in the examples and the solutions, was made salient by being underlined, bolded, and changing the color of a letter, as seen in

Figure 1. The tutorial was recorded via Camtasia and was converted to an mp4 format for the purpose of uploading it to YouTube, as this platform easily connected to the eye tracker employed to track participants’ eye-gaze activity.

2.4.2. Indirect CF Treatment

The length of the participants’ compositions ranged from 20–22 sentences (238–283 words) and displayed several grammatical errors, which were marked with indirect CF (i.e., codes accompanied by metalinguistic cues), since this type of correction has the potential to stimulate learners’ cognitive involvement by holding them accountable to do something with the comments received (

Chandler 2003). A secondary reason to choose this type of CF, as opposed to direct CF, was the fact that the participants’ training on written CF was limited to watching the YouTube videos.

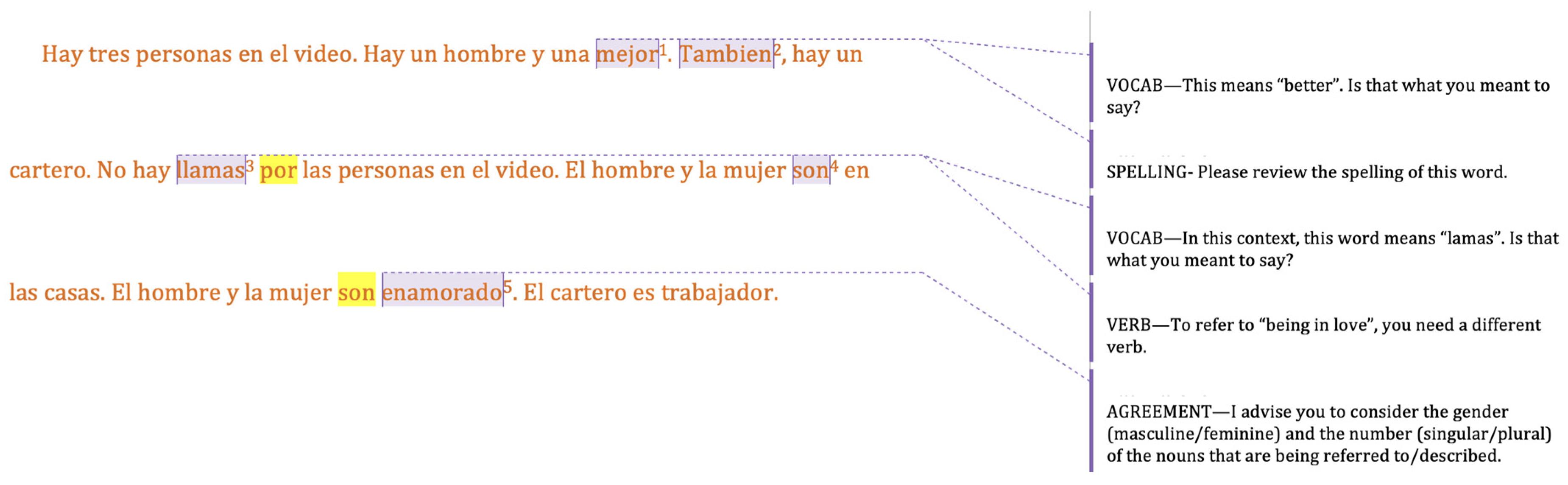

Although there were more, only 15 errors were marked (i.e., three per each type of error presented in the YouTube tutorial, see

Table 2), for consistency. Limiting the marked errors to 15 also guaranteed that the participants would have enough time to self-revise, as the time allocation to correct their compositions was 20 minutes. The codes and the metalinguistic information were provided in English (e.g., “agreement”) to ensure participants’ comprehension—as seen in the example below.

Expected form: El hombre escribe la carta para la mujer (The man writes the letter for the woman).

Error (participant #3): El hombre escribe la carta *por la mujer (The man writes the letter because of/instead of the woman).

Researcher’s CF: “VOCAB”—This means: “The man writes the letter because of/for the woman”. Is this what you meant to say?

2.4.3. Soundless YouTube Videos with Personalized Written CF

Once the researchers provided CF in the participant’s compositions, a 10-min soundless video for each narration created by the participants was created using Camtasia. The audio was not included to avoid overwhelming the participants cognitively when they reviewed the CF (

Moreno and Mayer 2000). Additionally, since the comments were in the participants’ L1 (English), no oral explanation was provided, as it seemed unnecessary and repetitive—see

Figure 2. Given that these soundless videos combined written information facilitated via Word track changes and input provided through video (i.e., image), it can be argued that this tool is embedded in a secondary modality

3. These soundless feedback videos were also converted into mp4 files and uploaded to YouTube. This process ensured uniformity in the length of time and the way in which the participants were exposed to written CF, while also conducting their attention to the marked errors right after they watched the tutorial.

2.5. Analysis Procedure

The data, including the compositions, the revisions, and the eye-gaze activity collected by the eye tracker, were analyzed as described below.

2.5.1. Composition Analysis

To account for the impact of CF on the degree of accuracy of self-corrections, each sentence in the composition was assigned applicable points (i.e., ranging from 0 point to 3.75 points) to establish the systematic quality per communicative attempt (i.e., sentence). That is, only sentences that displayed no errors were granted 3.75 points; otherwise, points were deducted according to a common rubric developed based on three domains which encompass linguistic features in Spanish that are crucial to convey meaning at the text level: (1) sentential requirements, (2) linguistic accuracy, and (3) mechanics. The “linguistic accuracy” domain directly corresponded to agreement-, missing word-, verb-, and vocabulary-related errors, while the “mechanics” sphere was associated with spelling errors. Although the sentential requirements were not directly included in the YouTube audiovisual tutorial, errors linked to missing words and vocabulary-related matters could be categorized in this domain. As shown in

Table 3, the distribution of points varied across sub-categories, mainly considering the level of difficulty the sub-category may pose for learners. Afterwards, all the points were summed up and divided by the total number of available points to obtain the overall rate for each composition. For example, a hypothetical narration that contained 20 correct sentences would be 75 points (i.e., 20 × 3.75). However, if because of grammatical errors the same narration would have received 65 points, the overall quality rate of the assignment would have been set at 86.66% (i.e., 65/75).

A couple of clarifications are important to make regarding the rubric. First, any meaning-related error embedded in a verb, for instance, *translatar, as opposed to traducir, to express the idea of “to translate”, was considered under the criterion “lexical/phrasal usage” (i.e., third sub-section of the second domain). This was because the “verb conjugation” (first sub-section of the second domain) only pertained to morphological errors. This created consistency with the YouTube audiovisual tutorial. As previously mentioned, sentential accuracy comprises a vital linguistic quality in Spanish to effectively communicate at the text level. Additionally, sentential accuracy was impacted by some missing words and vocabulary-related errors when these interfered with the conveyance of the meaning or affected the degrees of complexity of the sentence.

The errors marked with indirect CF were also coded to account for the total points that each participant could achieve upon accurate revisions. This codification process followed the exact same rubric used to rate the compositions (see

Table 3). For example, when provided with the code SP (i.e., spelling), which pertains to domain #3 (i.e., mechanics), the participants were granted 0.25 points, if the error was fixed successfully. Following the same scoring system was beneficial to allocate a comparable number of points to be obtained for accurate revisions across participants. In addition, the overall quality rate for the second draft was computed by adding the overall rate for the first draft and the total number of points earned upon successful corrections.

After the rubric was developed, the errors in each composition were first identified and coded by the first author of the study, and then examined by an instructor with rich experience in Spanish language instruction. The discrepancies between the two coders were resolved through discussion.

2.5.2. Eye-Gaze Data Analysis

While each participant watched the audiovisual tutorial and the soundless video with personalized feedback, all their eye-gaze movements were recorded with a Gazepoint 3 HD eye tracker. The device could capture participants’ left and right eye points of gaze, fixation point, left and right pupil data, and cursor position. The GP 3 analysis software interlinked with the device parsed the eye-gaze data in real time and produced gaze plots that tracked the path of participants’ eye-gaze movements by showing the location, order, and time as they looked at the screen. This helped us establish any ocular patterns when participants watched the tutorial and feedback videos. In addition, the software created heat maps at four levels of intensity, each reflected by a different color ranging from the least to the most intensive level of eye-gaze in the following way: green, blue, yellow, and red. Following

Smith (

2010,

2012), the participants’ eye-gaze activity registered at and above ⅗ of a second, in this case, yellow or red on the heat map (see

Figure 3), was operationalized in this study as profound (level of) attention, thus indicating meaningful eye engagement. For analysis purposes, the instances of meaningful eye engagement were compared to the total number of times that showcased any eye activity, which was established by resetting the analysis software to its original configuration (i.e., 0.0 s). In other words, making the machine display all eye-gaze movements as opposed to only showing those that were ⅗ of a second or above. When analyzing the audiovisual tutorials, the ocular occurrences registered in the introductory slide were not considered, as it mainly stated the aim and the layout of the video.

4. Discussion

This descriptive study attempted to unveil the connection between tools that mediate written, visual, and oral input and the way in which written CF is assembled and approached. This was achieved by exploring rates of successful revisions, types of errors that were more successfully revised, and whether and how eye fixation (i.e., noticing) account for accurate revisions. To this end, multimodal CF was derived by (1) an audiovisual tutorial on approaching teachers’ comments and (2) a soundless video displaying indirect CF (metalinguistic codes accompanied by metalinguistic cues). The results presented here are in line with

Shintani’s (

2015) observations regarding the overall efficacy of indirect written CF, as both studies showed high rates of successful revisions completed by the participants. In the present study, direct CF provision embedded in two semiotically different resources (i.e., audiovisual and visual only) seem to have contributed to an overall high rate of success. Additionally, the premise that learners’ accountability is a vital condition for CF to be impactful (

Furnborough and Truman 2009) is also substantiated. Although this study did not focus on the participants’ perceptions regarding the effects of multimodal CF (

Ducate and Arnold 2012;

Harper et al. 2015) or the advancement of learners’ linguistic system as a result of engaging in revisions (

Shintani and Aubrey 2016), our findings support the conclusion of

Ducate and Arnold (

2012),

Harper et al. (

2015), and

Shintani and Aubrey (

2016) regarding the potential of written CF for enhancing the overall quality of learners’ texts (in this case, draft one and two of the same writing assignment). Specifically, learners’ successful revisions in this study, facilitated by the provision of comprehensive, varied, and multimodal CF, led to the improvement of the original texts. When it came to the types of errors that were more accurately revised, it was observed that verb and vocabulary errors reflected the highest rates of successful corrections (88.88%). This could be due to the high number of occurrences of profound attention (214/421) that these two errors received while watching the YouTube audiovisual tutorial. This is of interest because verb and vocabulary errors are often difficult to avoid and to fix because of the different linguistic requirements that need to be met to convey a message (i.e., tense, aspect, and mood in the case of verb use). However, it cannot be argued that a high number of occurrences of profound attention necessarily led to more successful revisions, as when watching the soundless personalized video with CF, several accurate corrections displayed a low number of instances of profound attention, and vice versa. Because of this, when conducting similar research on multimodal resources that contain customized CF, such as the YouTube video with personalized CF in this study, it may be suitable to conduct an analysis of the overall instances of eye-gazing, as opposed to only focusing on those that register profound attention, as was the case in this study. This, however, is an arduous and time-consuming task.

Another objective was identifying any correlation between written CF provision and noticing via eye-gaze fixation. The positive relationship between learner noticing and their accurate rates of revisions provided further empirical support for the noticing hypothesis (

Schmidt 1993) and

Shintani’s (

2015) findings: more noticing, represented by learners’ profound level of attention, especially in the audiovisual tutorial, seemed to have positively contributed to a high success rate of learners’ revisions. Additionally, the results connected to learners’ eye-gaze activity support that using an eye-tracker technique can further unveil the linguistic features that learners pay attention to (

Smith 2010,

2012). More importantly, according to the observations by

Shintani and Ellis (

2013), the use of eye-tracking data provided the researchers with a novel and valuable approach to explore how learners attended to written CF, and thus, this helped uncover learners’ engagement and processing with the feedback that underlie their revising process, which has been insufficiently examined by existing studies.

Moreover, the results regarding eye-gaze data subsequently displays insights on (1) the rate of profound attention, (2) ocular patterns, and (3) the allocation of attention concerning (a) the types of errors that were most attended to and (b) the degree of concentration devoted to different types of content (i.e., CF vs. text without CF—see

Table 10). Specifically, in terms of the rate of profound attention when watching the audiovisual tutorial, accentuated similarities among participants were drawn, regardless of the course they were enrolled in, as displayed by the average of 10%. Regarding ocular patterns, similar behaviors were observed as all participants recorded repetitive and steady eye-gaze activities that were nonlinear while consistently relying on examples. This could be due to the overall uniformity of the treatment, as the information to address each type of error followed the same order, thus making the structure of the presentation somewhat predictable.

Concerning the allocation of attention, the fact that the types of errors that were most attended to were those connected to vocabulary- and verb-related matters is compelling since it reveals details to better understand how the revision process was approached, such as the fact that most of the errors of these kinds were successfully revised, as previously explained. Furthermore, when comparing the allocation of attention regarding different types of content (i.e., CF vs. text without CF) while watching the soundless personalized videos with CF, it was observed that most ocular activity fixated on the text without CF. Because of this, no visual patterns could have been established between error type and degree of attention. Perhaps the participants focused much attention on parts of the text that were not marked with CF because they wanted to make further sense out of the errors by considering the context relevant to them. All these findings, however, should be observed tentatively, as the sample size is small and no statistical measures were conducted in this study between time spent observing and successful correction.

Since it is imperative to develop effective pedagogical practices to assist learners to create meaning when constructing texts (

Hampel and Hauck 2006), or recreating meaning, as in the case when revising, the following tentative suggestions in terms of in-class practices to enhance the impact of multimodal written CF are in order. Nonetheless, it is important to mention that due to being a descriptive study, it is premature to recommend indirect CF over other types of feedback. The following next steps are suggested:

- ○

Designing audiovisual aids to serve as training means to guide learners to comprehend teachers’ comments, better understand or identify the nature of linguistic ruptures, and seek ways to amend them. An audiovisual format is highly suggested based on the overall positive effect that said means could have per the results of this study. Additionally, as previously mentioned, the multimodal component integrated in an audiovisual tool, like the one suggested, could yield greater uptake (

Chang et al. 2017) due to its dynamism, perpetuity, and its accessibility (

Campbell and Feldmann 2017). To maximize the benefits of these training means, the content should be personalized by focusing on the immediate needs of the class, such as the most recurrent errors in the target language, as was the case of this study, or on specific elements that cause difficulty to convey meaning, such as punctual grammatical points.

- ○

Incorporating a concise example that features a specific error, as was done in the audiovisual tutorials included in this study. This is suggested because of the visual behavior observed from the participants, as they heavily and cyclically relied on the example per error that was offered while watching the video. This suggestion, however, needs to be corroborated by further research as linear and nonlinear visual patterns connected to CF and revisions are unique to this study.

- ○

To maximize the degree of attention devoted to examples, integrating any techniques of saliency (e.g., changing the font color and bolding in this case) is recommended, as while analyzing the ocular engagement in this study, it was observed that these elements always drew participants’ attention and often represented profound visual activity. The efficacy and impact of saliency, however, is beyond the scope of this study.

- ○

Presenting the most complex information at the beginning of the audiovisual aid so that high attentional control is required from the participants when exposed to the training. This is recommended as the participants of this study produced more than half of the registered eye activity episodes within the first five minutes of the audiovisual tutorial. In other words, it was observed that the longer the participants stared at the screen, the less occurrences of profound ocular engagement were observed.

- ○

Decreasing the cognitive demand from learners by:

- ○

Featuring one error per audiovisual aid (i.e., slide) breaking down complex errors (e.g., verb-related inaccuracies in Spanish) into smaller units (e.g., inaccurate tense vs. requiring a different verb). This pattern was adopted when presenting the different scenarios that could be associated with verb-related errors and suggested being effective as 93.33% related to this category were successfully revised.

- ○

Enabling extended accessibility to all audiovisual aids so that learners can revisit them as many times as needed. This can also allow instructors to assign a particular tutorial or module to be watched prior to learners’ receiving CF and/or while revising. Given that the treatment drew a positive impact, as a high degree of efficient revisions was observed, it is plausible that having unlimited access to this content could reinforce learners’ awareness of common errors, especially in classes that comprise the language sequence at the college level.

5. Conclusions

This study has several limitations, so we should be careful in interpreting and applying the findings because of the small sample and exploratory nature of the study. The small size made it impossible to apply inferential statistics to the data and, thus, limited the generalizability of the findings. As such, it is indispensable to meaningfully expand the pool of participants to at least 40 individuals. Additionally, without having a control group and incorporating a pretest-posttest design, the efficacy of multimodal written CF in this study was mainly based on the comparison between learners’ first and second drafts of the compositions. Building on this descriptive study, future research should adopt a more rigorous design to investigate the possible effects of multimodal written CF more accurately on learners’ writing development as measured by the efficacy of revisions and the creation of new pieces of writing as a means of immediate and delayed posttests. Additionally, instead of providing learners with feedback on five types of linguistic errors, we can also offer learners comments targeting only one linguistic element in future endeavors to explore the effects of focused written CF more aptly, such as the hypothetical conditional researched by

Shintani (

2015).

Overall, this descriptive study reported insightful findings regarding the efficacy of multimodal CF and the possible relationship between learner noticing and their revising performance. The observations of this study not only added to the scant investigation into the potential benefits that multimodal written CF may provide for L2 Spanish learners, but also unveiled learners’ engagement and ways to approach teacher feedback.