4. Results

The data served to illuminate patterns of transformation and transduction and to answer the research questions regarding how language learners navigated the DST process and multimodality by transforming the text of their simple narratives into voice-over scripts and by integrating text, image and sound during transduction moves as they navigate the affordances of multimodal technologies during individual and collaborative tasks and, in each of these elements, what typified any differences (e.g., greater frequency and/or variety of transduction moves) the SHL learners and L2 learners exhibited in their navigation of multimodality.

4.1. Transforming the Text of Simple Narratives into the Voice-Over Script

In both tasks, participants were required to transform the collaborative 500–700-word simple narrative into a 250–300-word voice-over script, and they were urged in class and in the guidance of the Google document not to go over 300 words. In the collaborative task, seven participants reported in their written reflections that they focused on isolating and maintaining the most important points of the narrative decided via discussion among partners, as when Mason (Pair 5) stated, “We looked at our story and chose what needed to be kept for an emotional appeal as well as solid information to back up our topic”. His partner concurred when Charlee said, “We worked together…[going] through the whole narrative and decided what was crucial information”. Four of fourteen mentioned “cutting” or “condensing” the simple narrative, and both members of Pair 4 mentioned changing the point of view for part of the voice-over script. William (Pair 4) mentioned a shift in point of view from the father in the simple narrative to the son in the voice-over script. He recalled, “We shifted from focusing on the son, Armando, [in the story] to Mateo [the father in the story], because after talks with [the instructor] we thought it would add more drama”. He continued, “When it came to the voice-over itself we split it up, using myself as a 1st person perspective to add depth to the story, and [Emma--his SHL partner] was the one to set the scene and explained the plot information in order to move the story along”.

Using word count, one element of transformation, results show that all seven pairs of language learners were successful in meeting the minimum word count of 500 for the collaborative simple narrative, while four of seven pairs were unsuccessful in transforming the voice-over script to the maximum word count of 300 or less, as instructed in class and within the guidance of the Google document; however, these were over by no more than 32 words. This contrasts sharply with the totals for the second task, the individual DS, as can be seen in

Table 6. SHLs were slightly more productive than the L2s in total word count in the simple narratives and slightly more able to condense their stories into the voice-over scripts, as can be seen in the first columns of

Table 6 below.

Four participants also cited preliminary plans for using images and sounds as they wrote their voice-over script. The writing guide in Google Docs defined transduction and encouraged them to contemplate possible transduction moves as they transformed the narrative to script. Olivia and Abigail (Pair 5) mentioned using the idea of transduction during the transformation process. Olivia wrote, “For the most part it was just picking words that we could omit and then replacing them with pictures and other things”. Abigail concurred, “We also decided which parts we could explain through pictures and which parts we could use through sound”.

As with the collaborative DS, participants were required to transform the 500–700-word individual simple narrative into a 250–300-word individual voice-over script. While four of the fourteen language learners were unsuccessful in meeting the minimum word count for the individual simple narratives, seven were unsuccessful in transforming the individual voice-over script to the maximum word count; two exceeded by more than 160 words. As can be seen in

Table 6 below, compositions exceeding the task parameters are in bold and justified to the right, and compositions not reaching task parameters are in italics and justified to the left.

None of the collaborative compositions were under the word count parameters, while seven of the twenty-eight individual compositions were short. As noted in the table above, four SHLs complained specifically about having to cut or sacrifice detail in the individual voice-over script, and three of those exceeded the word-count parameters. Two L2s made that complaint, but only one of those two exceeded the maximum. In fact, Olivia (Pair 5) complained; however, she came under the suggested minimum by 18 words.

4.2. Structuring the Multimodal Text: Transduction

The second reflection occurred after students completed the rough drafts of the collaborative DS multimodal composition. Question 2 asked them about ways in which they accomplished transduction: “Which elements did you convert to other modes (images, sounds, music) in order to economize your words?” Respondents referred to images, music, voice effects, sound effects and text-on-screen. All fourteen respondents mentioned the use of images for transduction. Only two of the six L2s, Mason and Charlee (Pair 6), mentioned transduction through music. Conversely, five SHLs of eight did so: Maria (Pair 1), Amelia (Pair 2), both Noah and Avery (Pair 3), and William (Pair 4). Two from each demographic said they used sound effects to replace text, and only one L2 said she used text-on-screen to economize. However, evidence of their professed transduction efforts was not always obvious in the digital compositions.

Regarding the substitution with image, Abigail (Pair 5) explained, “We did this … by changing the description of the red-headed teacher to a picture of the teacher. The description was then rendered useless, and we were able to cut that part out”. William (Pair 4) explained their deliberate use of image, sounds, and silence when he stated, “The main way we used pictures and sounds to convey a meaning is when Mateo is picked up by the police. At this point, we used a lack of music and a pause of [silence] before the sirens and sounds of jail bars being closed are played”. This pause in the music and use of sound effects in the collaborative DS corresponded to the pause in the voice-over script after his partner Emma, the narrator, said, “Era un día normal en mayo cuando…./It was a normal day in May when…” and before his character stated, “En un segundo, todo de mi futuro cambia./In a second, my whole future changes”. William continues to explain the lack of music as his first-person narration continues, “Then for my narrative, there is no music again so there’s only one thing to focus on, adding to the intensity and conveying that sense of unknowing”.

Clearly, not all digital composers understood the transduction concept at this point despite having heard explanations in class and having an explanation in the task guidance. Both partners in two pairs and one partner in another pair only referred to images and sounds as complementing the words of the voice-over script rather than additive or substituting elements of the original simple narrative. For example, Noah (Pair 3) said, “I told my partner that we should first listen to our audio and write down images that we would imagine as the script played out. This way, we would have images that the listener would most likely be thinking of as the script went on”. Liam (Pair 7) responded, “Mainly we are just using sound effects and pictures to reinforce what is said”.

The fifth reflection followed the completion of the rough drafts of the individual DSs, and participants responded to the question, “What changed between the narrative form of the digital story and the final script with images and sound?” Six of the fourteen, as indicated by the asterisks in

Table 7 below, referred to cutting out details or words to achieve the transformation between individual simple narrative and voice-over script, including Mason (Pair 6) who only reduced his word count by 29 words. Four of those six respondents did not mention replacing the cut passages with images or sound. Six of the fourteen reported replacing words with sounds, images and video. Sofia (Pair 1) incorporated all three; she stated, “I focused a lot on taking words away and working more with visuals. …a lot of scenes had to be cut in order to stay within time limits. … I attempted to balance this a bit with other background sounds and music shifts. Of course, I also took a risk in adding video to part of my story”. Abigail (Pair 5) specified multiple modes she used to replace text: “The final script used images and sound to consolidate the number of words used. I utilized a ringing sound and a door shutting sound to exemplify the effects of the story without using too many descriptive words. I also used a map to show where José’s parents moved without using extra words to portray this”.

In the reflections, students were asked specifically about their use of transduction. After the collaborative DS process, only four of fourteen participants made mention of plans for the substitutions of another mode for words in the simple narrative. At this stage in the individual DS process, six of the fourteen participants mentioned substitutions of another mode for words.

The total transduction moves during the collaboration were seven and increased to 50 in the individual DSs. Sofia (Pair 1) accounted for 26 transduction moves in her individual DS, as seen in

Table 8 below.

Mason and Charlee (Pair 6) did not show any clear evidence of transduction as a team or as individuals, whereas Pair 1 exhibited 29 transduction moves across both tasks. Though a statistical analysis was not advisable due to the scarcity of data and the wide range of scores, the raw data did yield interesting trends. For example, SHLs accounted for 87.72% of all transduction moves, and L2s only accounted for 12.28%, which will be discussed further in the discussion section below.

4.3. Navigating the Affordances of Multimodal Technologies

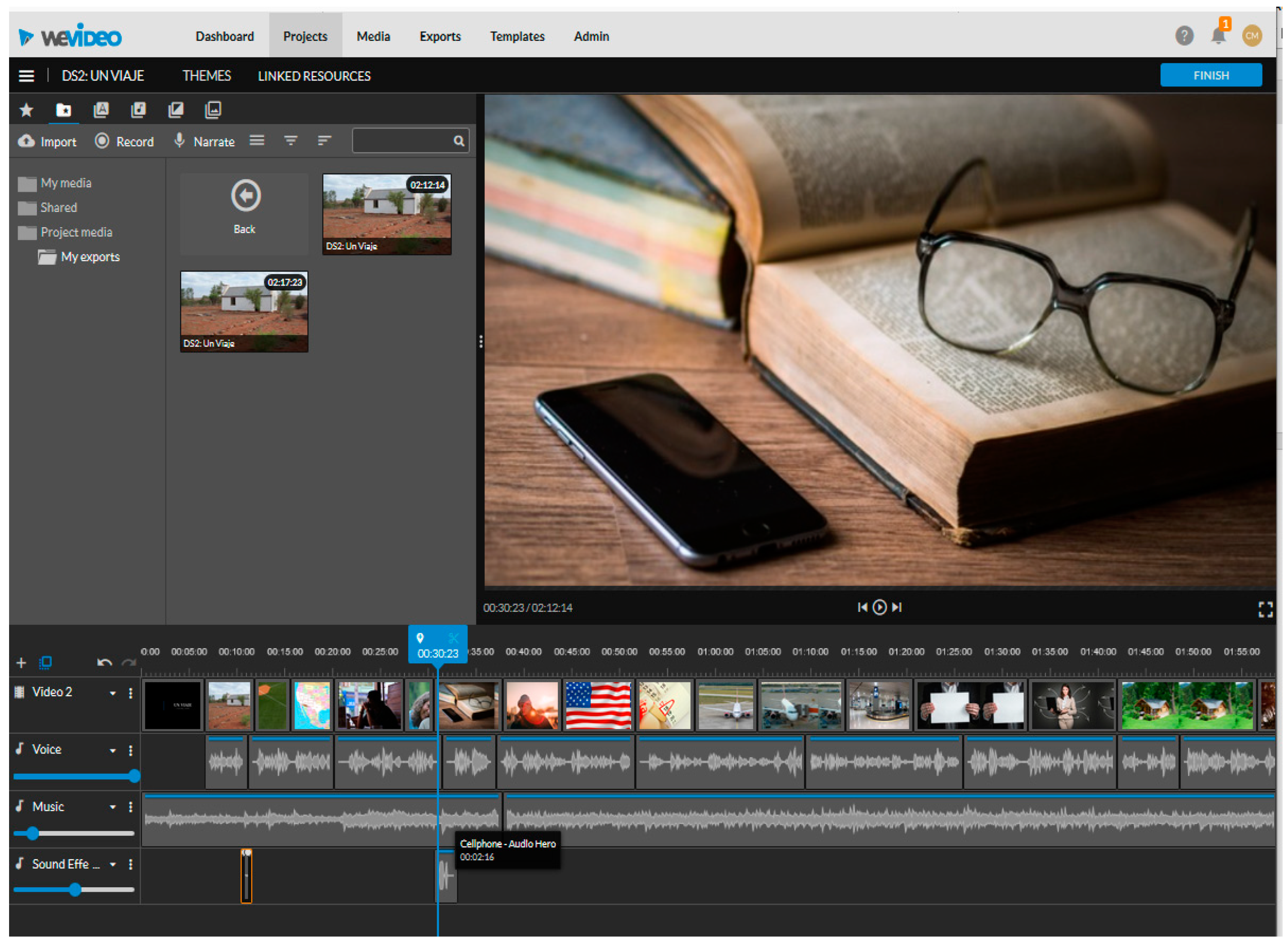

The WeVideo platform proved to be an exceptional tool for the integration of modes in a DS. In WeVideo, the digital composers could layer as many visual and audio tracks as they desired, resulting in digital synesthesia (

Kress 2000). For example, some participants even layered images, thereby creating a new image; however, no one overlapped music tracks even if they created separate lines for each in WeVideo. In

Figure 1, Abigail (Pair 5) used four layers of media, visible across the bottom of the screen capture: (a)

Video 2 with images (including the beginning title slide and the credits not pictured but at the end); (b)

Voice with the voice-over recording; (c)

Music with two audio tracks of music; and (d)

Sound Effects with audio clips of a door closing and a cell phone ringing.

Like Abigail’s, most DSs contained four media tracks; although, some contained overlapping images rather than sound effects. For example, Liam and Luca (Pair 7) used an image of a single-family house with an image of U.S. dollar signs (

$$) superimposed on the image, to reinforce the idea that owning a house is expensive in the United States. All DSs contained at least three separate tracks: one for images, voice-over recordings, and music. Only Sofia (Pair 1) inserted a fifth type of track using layers of text-on-screen over images. The use of multiple layers of media did not, however, always result in transduction. Transduction occurs when digital composers use one mode to replace another. For example, in Abigail’s story above in

Figure 1 above, the blue vertical line intersects a point in the story in which the picture of a telephone complements the sound effect of a ringing telephone at the point that Abigail’s recorded voice-over states, “Después de mucho tiempo, José recibió una llamada./

After a long time, José received a call”. This was not an example of transduction because the exact sentence also appeared in her original narrative; therefore, the image and sound effect were not additive in that they did not supply information missing from the voice-over recording but present in the original text. Most of the additional modes complemented or illustrated rather than substituted text. Some multimodal elements may have substituted language ideation occurring during the development of the digital version, but was missing in the original text narratives. It is possible, for example, that Abigail could have selected the image of the telephone with the idea that her character’s parents interrupted a homework session with the call, which would make the image additive. However, the point of comparison was the simple narrative from Google Docs, the recorded voice-over script, and the digital composition in WeVideo; Abigail’s individual simple narrative did not contain information on what her character was doing when he received the call, making it impossible to code as transduction. Participants could also add movement to their images by adding transitions between images. The classroom instructor explained the transition tools during class, and 100% of the participants used transitions during their DSs.

All DSs also contained music tracks; although, a few suspended the music at some point in favor of using silence for effect. Many used only one music track for the entire DS, and a few even inserted the same track a second time when it did not last for the length of the DS. Some with two music tracks waited until the credits to play the second track, while others used a second, third, or even fourth track to match the storyline with a particular song to set the mood or to change the story’s tone. Noah (Pair 3) mentioned adding three tracks in his collaborative DS, and later he added four to his individual DS; he explained his use in the individual DS, “The music reflected the mood and pace of my story. I also utilized certain music to highlight moments that I wanted the audience to pay attention to. I did this by changing tracks, alternating volume, or even cutting out music completely”. However, it was difficult to say that music replaced text in the simple narrative, which would have comprised a transduction move. Only three clear instances of transduction from written language to musical tracks emerged, and all three were in two individual DSs produced by two SHLs. For instance, Victoria replaced “viven felices/they live happily” with festive Mexican music in her individual DS.

While no one added video footage to the collaborative DSs, three did so for the individual DSs. Noah (Pair 3) and Mason (Pair 6) used videos that they found on the internet. They may have noticed that one of the example DSs from the pilot contained video footage, or they may have realized the possibility independently while using WeVideo. Conversely, Sofia (Pair 1) asked the instructor for permission to use video, recruited an actor, and self-produced seven of her own video clips. The video footage from Sofia’s individual DS were among the clearest examples of transduction in the project. All but one of her video clips could be directly linked to passages in the simple narrative that were missing from the voice-over script as can be seen in

Table 9. To clarify, her actor never spoke, and the video footage itself had no sound. The sounds of the DS were the voice-over track, the music tracks and the four sound effects.

Sofia stated that her use of video occurred when her character was moving forward and that she switched to still images when he faced obstacles due to his lack of English-language skills, adding an interesting layer that she acknowledged might have been lost on the viewers. Sofia, an SHL, was the only participant exhibiting transduction from language to video.

In sum, participants used the available affordances of a variety of modes including images, video, sound effects (e.g., siren, telephone ring), and text-on-screen to replace text passages present in the simple narratives—elements that were removed from the voice-over scripts and that reappeared in the DSs via other modalities. Transduction was defined for the participants in class and in the writing prompts for the voice-over script; however, using transduction moves was not on the grading rubric and, therefore, was not specifically required. As a result, not all participants showed clear evidence of transduction between the simple narrative and DS tasks. In the collaborative task, Pairs 6 (Mason and Charlee) and 7 (Liam and Luca) did not clearly use transduction. Five participants, Noah (Pair 3), William (Pair 4), Mason and Charlee (Pair 6), and Liam (Pair 7) did not clearly use transduction in the individual task.

Pairs used images in transduction moves five times in the collaborative DSs, whereas individuals used images in transduction moves 29 times. Sofia (Pair 1) used self-produced video six times to replace text in the individual simple narrative. There was no clear evidence of transduction using sound effects or text-on-screen in the collaborative DSs, whereas individuals used sounds in transduction moves 11 times, and Sofia (Pair 1) used text-on-screen in transduction moves four times. For example, Sofia layered three modes to replace language from the individual simple narrative, as seen in

Table 10 below.

The research questions sought to explore how the composers navigated multimodality using digital tools in the collaborative and individual products as well as the behaviors of the different demographics within the class, specifically, how they used modalities during the synesthesia. After completing their original narrative stories, the participants were tasked with economy of text during the transformation of the simple narrative to the voice-over script in that they had to keep their voice-over scripts under a maximum number of words. As they transformed one written text into another, they planned for the integration of the diverse modes of image and sound beyond the spoken words of the audio recordings of their written voice-over scripts. The use of some of these images and sounds resulted in the occurrence of transduction moves in which they substituted words from the simple narrative with visual elements and sound within the multimodal digital composition.

5. Discussion

Regarding the transformation of the simple narratives to the voice-over scripts, collaborative partners stayed very close to task parameters; however, the majority of the individual writers did not seem able or chose not to stay within prescribed word counts, mostly by exceeding the word count for the scripts. This willingness to forgo parameters could result from lack of partner accountability or lack of dialogue between collaborators on ways to reduce the word count. Writers also seemed more preoccupied with “cutting content” rather than following the guidelines, which encouraged replacing text with other modes.

Regarding structuring the multimodal text and navigating multimodality, one of the most salient conclusions evident in this research is that multimodality did not necessarily mean that the participants rendered clear evidence that they utilized these modes to achieve transduction by substituting passages from the original text versions of the narratives with other modes in the digital versions in WeVideo. This difficulty in putting the concept of transduction into practice is hinted at in Nelson’s study (

Nelson 2006), which found that participants struggle in their manipulation of semiotic resources to convey deeper meanings and is confirmed by

Elola and Oskoz (

2017), who also found that transduction can be difficult for learners to accomplish, even when explained. Rather than configuring the words, images, and sounds in such a way that each holds a part of a message in counterpoint, each element is incomplete without the others, and most of the collaborative DS composers held a line of melody with the elements working in unison, each sharing the same message. Without the second task, transduction would barely be noticeable. Possible reasons for its relative absence in the first task may include

lack of understanding of the concept or

lack of motivation for the deep thinking required in a more complex design.

Although transduction in the collaborative DSs was almost nonexistent, the individual digital compositions contained many more occurrences of transduction. Collaborative DSs only exhibited seven clear transduction moves, while individual DSs contained fifty, with Sofia (Pair 1) accounting for 26. In the collaborative project, all participants complained of having to cut content from the simple narratives to accommodate the guidelines of the task, and that appeared to be the way most pairs achieved economy in the transformation process, with only one sound effect and six images to substitute language. The increased number and the greater variety of modes used in substitution in the individual DS indicated growth in using diverse methods for economy; although, many still complained about having to cut detail and content, indicating a possible progress in understanding the concept of transmodal movements. This greater use of transduction in the second project may be due to just that, a better concept of using multiple modes effectively via the practice effect of task repetition.

Manchón (

2014) cited the benefits of oral task repetition for language acquisition and suggested the possible extension of benefits for language acquisition from the repetition of a written task and continued instruction. The same could be true for developing synesthetic skills during multimodal task repetition. By this time in the second task, the participants had seen and heard the definition and examples multiple times in the classroom setting as well as the task guidance in Google Docs and individual writing conferences, highlighting the importance of the practice needed to develop expertise in multimodal design and the need for improvement in its instruction.

When considering demographics, the SHLs created many more transduction moves than the L2s, 87.72%, or more than seven to one, and with half of all the L2 population having no clear transduction moves of any kind. All three of these L2 participants acknowledged the use of images for economy in their reflections, revealing a conscious effort to combine different modes to share their message, whereas others simply visualized the action of the script and looked for images that illustrated those mental images, resulting in illustrative rather than additive images. The composers may have ignored the task guidance, which instructed them to ponder and identify passages that could be replaced with images and sound before writing the script, or they were simply focused on cutting language and forgot that option. The SHLs also used a greater variety of transduction modes, including images, video, sound effects, music and text-on-screen, while the L2s only revealed clear substitutions using images.

Why were the L2 participants for the most part unable or unwilling to transform their texts by transduction or “movement between and across modes” (

Newfield 2017, p. 103)? They clearly expressed frustration with what they perceived as the necessity to cut content and detail. The researcher’s field notes recorded details on two separate occasions when L2 participants complained openly in class of having to cut material from the simple narrative, and, each time, the instructor coached them on possible transduction moves by re-explaining the concept of transduction and giving examples. The qualitative data from the participants also mentioned that the instructor suggested transduction moves as an alternative to simple text reduction in some of the instructor’s face-to-face feedback sessions. The L2s appeared to understand the concept, but this apparent understanding did not translate to practice. Almost all images and sounds were illustrative rather than additive, as with Abigail’s DS (Pair 5) seen previously in

Figure 1. In such a small sample size (L2s:

n = 6), it is impossible to generalize, but it may have been due to individual differences or preferences among the participants, lack of task engagement, or, perhaps, inability or unwillingness to deal with the increased cognitive load required in the transduction process (

Newfield 2017). This notion of language learners having a limited capacity or a maximum cognitive load was advanced by

Skehan (

1998), who posited that the brain can handle only attend to a limited amount of detail at any one time. The language skills of the L2 learners may have been taxed to the point that they chose not to expend the extra energy on the deep thinking required to achieve transduction. As mentioned previously, transduction was not a requirement but a suggestion; therefore, L2 learners, who were more focused on task completion and grade, did not have that incentive to encourage them. Only one of the L2s, Olivia (Pair 5), highly rated and boasted of her writing skills in Spanish, and she and her partner Abigail were responsible for all but one of the L2 transduction moves; perhaps her view of herself as a masterful L2 writer may have been an individual difference affecting the outcome. This notion is strengthened by the fact that Sofia (Pair 1) was responsible for many of the transduction moves for the SHLs. Sofia also considered herself a strong writer, and she prided herself on the lengths she went to in the crafting of her story. Olivia also indicated a level of engagement in her individual DS not present for many of the L2s, in that she intended for the person she interviewed to view the story he had inspired. Another possible variable is that, although the stories were not autobiographical, SHLs still identified with the characters in their DSs, resulting in a vicarious identity-building and sense of empowerment, evident in

Davis (

2005),

Hull and Katz (

2006) and

Jiang et al. (

2020).

Still images were the greatest source of transduction from the text to the digital compositions. This is not surprising since digital composers used a whopping 380 images, which included stock photographs, candid photographs, self-made photographs, clipart, maps, and emoticons. In the qualitative data, many participants often spoke about substituting language with images, revealing an understanding and application of the concept in their efforts to economize their words in the digital version. For instance, Abigail recalled that she “used a map to show where José’s parents moved without using extra words to portray this”. A few studies have looked specifically at transduction and the use of images in DSs (

Hull and Nelson 2005;

Nelson 2006;

Oskoz and Elola 2016a;

Yang 2012), but none have accounted for the rate of transduction moves using images as compared to illustrative images or their frequency as compared to other transduction moves. The deliberate depth of thinking involved in making these choices is what

Newfield (

2017) refers to as the “transmodal moment” (p. 103), and not all participants appeared to grasp or to invest in its completion.

Although presented as an option, most composers did not utilize text-on-screen beyond a title and the credits. Only Sofia’s (Pair 1) contained text-on-screen to replace language and information from the simple narrative, establishing setting and time of day. Conversely, the use of video rather than still images was not presented specifically, but three used video footage in the individual DSs. Although not a requirement, all of the participants enhanced their DSs by adding movement to at least some of their images by using the digital tools available in WeVideo. These tools made it possible to add transitions between images to soften the change from one image to another, such as the fading in and out of the image. Another tool used widely was a pan-in or pan-out feature, which meant that the image could start with the full image and slowly focus in on one element of the image, such as a face, or vice versa. The students were shown how to use these tools during class time. However, the addition of video by Sofia (Pair 1), Noah (Pair 3), and Mason (Pair 6), rather than still images, is an example of innovation on the part of these individuals in the development of digital skills, as found in

Chan et al. (

2017), who found that “students may develop their creativity and innovation in expressing their ideas with digital media” (p. 13).

Although a distant second in the types of transduction moves, the digital composers embraced the use of sound effects in the individual task, more than quadrupling their use of sound effects from the collaborative DSs to the individual DSs. These sound effects, or non-musical sounds, such as an audio clip of a siren or the chatter of children on a playground, added to the realism of the composition. The presentation of the first DSs was a very high moment in the class, and this may have translated to including a non-required element in the second by observing the dramatic impact of sound effects in the collaborative DS by Emma and William (Pair 4), who used a siren and the slam of a cell door at the detention of the first-person narrator. Mason (Pair 6) remarked that he liked Pair 4’s collaborative DS “…because of the use of sound effects to stress the situation and add flavor”. Since sound effects were not required for the DSs, their increased use may have correlated with a higher level of motivation and engagement in the second task, as when

Semones (

2001) found that levels of motivation rose during the DST process.

Sadik (

2008) also found that DST promoted creativity and motivation, which could be connected to this willingness to add an additional layer to the stories, illustrated by Pair 1’s Maria who stated, “I was able to add sound effects which made my digital story stand out compared to others who chose not to incorporate sounds into their stories”. Additionally, as in

Chan et al. (

2017), growing ease with the technology as the participants had more practice with WeVideo may have been a factor, resulting in more intricate digital compositions due to task repetition. A counterpoint might have helped to gauge if the increase is due to task repetition or to working individually. When separated by demographic, the SHLs used many more sound effects than the L2s (18 to 5, respectively).

Despite the higher number of sound effects used, the majority served to enhance the language of the recorded voice-over script rather than to replace passages in the simple narratives. Clear connection to transduction from language to sound effect was only present in three DSs, all created by SHLs: the collaborative DS by Pair 4 mentioned above and two individual DSs, Pair 4’s Emma (airplane taking off) and Pair 1’s Sofia (wind, shoppers, door slam, and construction tools). There is a dearth of research specifically addressing the use of sound effects to achieve transduction and multimodal synesthesia in digital compositions, except for

Oskoz and Elola (

2016a), who found that DS composers used inflection, repetition and pauses to replace connectors between sentences. However, the initial plan for transduction, as with other transmodal moments, most likely needs to occur during the process of text transformation from the simple narrative to the voice-over script, and if the composers fail to do so at that point in the process, it may not happen at all. Transduction does not happen accidentally, but rather by deliberate choices that multimodal composers make as they construct the digital versions. In this project, once the target number of words emerged from the transformation process, the need for transduction ended; therefore, any changes after that point would be the result of desiring to add more words to the voice-over script recording and finding a way to replace passages at that point. However, these participants were more likely to extend the voice-over script beyond the maximum word count, as Liam (Pair 7) did when he submitted a shorter voice-over script in the text version for grading, but added passages in the recorded version, highlighting that half the participants were unable to transform their simple narratives into voice-over scripts, which fit the parameters of the task by going over the maximum word count allowed.

Another surprise was the difficulty in attaching a musical passage or track change as a substitution for words in the simple narratives. Most of the time the language of the voice-over script also indicated the change in tone. Very few clear instances of transduction from written language to musical tracks emerged, and all were in two individual DSs produced by two SHLs. Many studies on DST mention the use of music as an additional layer (e.g.,

Chan et al. 2017;

Huang et al. 2017;

Yang 2012), but most describe the use of background music in terms of simply setting the mood for the DS rather than specifically noting musical passages as transduction moves replacing text. Although setting the mood could be perceived as a form of transduction, the music seemed to complement the text of the voice-over script rather than replace it.

Lastly, was the unique case of Pair 1’s SHL Sofia, who was one of the top writers in the class. The depth of thought and planning that Sofia incorporated in the execution of her individual DS was unparalleled. Sofia considers herself a writer, so, that she would meticulously craft her words was unsurprising, but her DS showed evidence of that same meticulousness in the crafting of the nonverbal modes, some of which she admitted were lost on the viewers. As mentioned earlier, she used still images when her character hit roadblocks in communication, but used self-created video footage when her character was moving forward toward the accomplishment of his goals. Also mentioned previously, Sofia was the source of almost half of all instances of transduction, which shows a deep level of understanding of the concept of transduction moves, which

Kress (

2010) suggested indicate agency in the multimodal designer. Also surprising was the variety of types of transduction moves. Sofia used all of the moves mentioned in the task guidelines (image, music, sound effects, and text-on-screen) as well as the silent video she self-produced to replace text. The greatest surprise of all was that the outside judges, who were familiar with the DS process and products, did not recognize Sofia’s DS as a class winner, and only Abigail (Pair 5), who heard Sofia mention all the time she spent on it, mentioned it as a favorite because she recognized the time and effort invested once she viewed the DS. This lack of recognition could have come from the judges’ privileging the overall impact of the DS rather than the intricacy of design. If the intended outcome within the activity system was digital literacy in the L2, then Sofia was the winner, but somehow, her effort did not translate into a DS that was recognized as the multilayered, complex multimodal product it was.

Nelson (

2006) stated,

However, power tools do not necessarily a carpenter make, to coin a phrase. To engage Synaesthesia in its truly creative sense, one must not only understand the tools and the codes of the new media age; one must understand how to recombine these communication resources so as to bend them to her/his expressive will.

p. 72

Sofia acknowledged that some of her imagery was most likely lost on the viewers and that her choice to keep the pacing slow in an effort to communicate the monotony of her character’s days may have been a misfire, which may have been the main reason her individual DS did not stand out: it seemed very slow. In other words, Sofia’s weakness was that she did not have a sense of how the slow pace would affect the classroom community and judges. Perhaps if she had had a collaborative partner or more practice, this weakness could have been addressed and she would have realized that she needed to make adjustments to heighten the impact of her story.

When considering the demographics separately, the SHLs produced text and digital compositions that were more complex in their design than those of the L2s in the variety and quantity of transduction moves in their process of transformation from simple narrative to digital compositions. This willingness to add transduction could stem from their language skills as typical SHLs, which may have allowed them to manage the tasks in such a way that allowed them the time to increase the intricacy of their multimodal products. This addition of additive elements in the individual products was most likely due to the SHLs’ strength and confidence in their linguistic skills that made up for the lack of a partner, the connectedness the SHLs felt toward their content, and/or the L2s’ focus on fulfilling, but not necessarily exceeding, the tasks’ parameters: barely producing the required number of words in text documents and not adding complex elements, which were not required, to the digital texts. In fact, some L2s accounted for their reduced output by saying that it was hard to generate content alone, and others said that they were anticipating having to cut content for the individual voice-over script to comply with the directive to economize because they were concerned with the graded product and not necessarily the ungraded process. While the SHLs seemed more invested in the DSs as an opportunity to share a meaningful message that was close to their hearts, the L2s were more focused on the composing process as a series of tasks to complete and grades to earn; although, their emotional investment seemed to rise in the individual project, due to the requirement of a personal interview. The L2s also seemed more resistant to the inclusion of DST in the curriculum, perhaps because they felt less connected to their content and more focused on the tasks; although, their emotional investment seemed to grow with the interviews included in the second task. Conversely, the SHLs seemed to view the DSs as a meaningful activity with a purpose worthy of their time and effort, most likely due to their connection to the cultural content of their research and interviews. Therefore, educators should find ways to enhance the presentation of DST as a valuable genre and include additional means of enhancing task engagement for L2 composers.