Abstract

The study offers novel evidence on the grammar and processing of clitic placement in heritage languages. Building on earlier findings of divergent clitic placement in heritage European Portuguese and Serbian, this study extends this line of inquiry to Bulgarian, a language where clitic placement is subject to strong prosodic constraints. We found that, in heritage Bulgarian, clitic placement is processed and rated differently than in the baseline, and we asked whether such clitic misplacement results from the transfer from the dominant language or follows from language-internal reanalysis. We used a self-paced listening task and an aural acceptability rating task with 13 English-dominant, highly proficient heritage speakers and 22 monolingual speakers of Bulgarian. Heritage speakers of Bulgarian process and rate the grammatical proclitic and ungrammatical enclitic clitic positions as equally acceptable, and we contend that this pattern is due to language-internal reanalysis. We suggest that the trigger for such reanalysis is the overgeneralization of the prosodic Strong Start Constraint from the left edge of the clause to any position in the sentence.

1. Introduction

Object clitics are of special interest to theoretical linguistics and language acquisition due to their morphosyntactic and prosodic complexity. Their two main features—realization and placement—raise important questions about language architecture and processing mechanisms in both monolingual and bilingual populations. Clitic realization has been studied extensively in the L1 acquisition of Romance (Perez-Leroux et al. 2017) and Slavic languages (Mykhaylyk and Sopata 2016; Radeva-Bork 2012; Varlokosta et al. 2016). It represents a continuous process of knowledge integration, which reaches target, regardless of initial period(s) of clitic omission in some languages, such as French, Italian, and Catalan (for an overview, see Grohmann and Neokleous 2015; Ionin and Radeva-Bork 2017).

Unlike clitic realization, L1 acquisition of clitic placement has not attracted much attention. A large elicited-production study of clitics in 16 different languages (Varlokosta et al. 2016) revealed that monolingual children achieve the correct clitic placement at around age 5;0. Consistent clitic misplacement has been documented only in European Portuguese and Cypriot Greek (Costa et al. 2015; Grohmann and Neokleous 2015; Neokleous 2015). These languages show protracted development of clitic placement in the direction of enclitic bias, that is, the use of post-verbal clitics (enclitics) in contexts that require pre-verbal clitics (proclitics). Such behavior was attributed by some to the complexity of the input and the properties of lexical items and syntactic contexts (Duarte and Matos 2000; Petinou and Terzi 2009).

In heritage languages (HLs), the topic of the present article, clitic realization appears target-like (although, more empirical data are needed). In contrast, clitic placement in HLs shows mixed results. Target- and non-target-like performance has been reported in clitic languages with different triggers for clitic placement, be that finiteness, interrogatives, or negation (Montrul 2010; Pérez-Leroux et al. 2011; Rinke and Flores 2014).

In this article, we present novel evidence for divergence in the processing of clitic placement by adult heritage speakers (henceforth: HSs) of Bulgarian, a language where prosody constrains that placement. Using online and offline comprehension tasks, we show that, although clitics are resilient in Heritage Bulgarian (HB), there is overgeneralization of the prosodic constraints, which leads to a lack of discrimination in processing and equal acceptance of ungrammatical and grammatical clitic positions.

While the morphology and syntax of HLs have received much attention, not enough is known about the representation and processing of prosodic constraints in HLs. Scholars have noted that early L1 exposure bestows a perceptual advantage on HSs in suprasegmental properties, such as stress, intonation, or contrastive focus (Kim 2019, 2020; Laleko and Polinsky 2017; Singh and Seet 2019). Task type, acoustic similarity of HL contrasts, degree of literacy, language mode, and proficiency level are all strong predictors of HSs’ robust perceptual performance (Chang 2022). Will HSs be also sensitive to prosodic constraints on clitic placement, given that they are less salient acoustically than intonation or contrastive focus? Prosodic constraints are usually viewed by theoretical accounts as operating post-syntactically, after the initial linearization of elements (Franks 2017, 2021). This could make them vulnerable in HL due to the higher cognitive load associated with the mapping of post-syntactic (interface) operations (Benmamoun et al. 2013; Sorace 2012; Sorace and Filiaci 2006; Tsimpli and Sorace 2006).1

Despite the important role of clitic placement for HL architecture and processing, it has been investigated only in a small number of languages. In Spanish, clitic placement in main clauses is regulated by finiteness; that is, proclitics are placed before finite verbs, while enclitics are used after non-finite forms. Clitics in Spanish are common in both oral and written language, and speakers are exposed to them from early age. Target-like performance was documented in Heritage Spanish, both in adult and child production and comprehension (Montrul 2010; Pérez-Leroux et al. 2011). Montrul (2010) tested clitic placement in adult HSs with low proficiency; the tests included oral narrative production, a written acceptability judgment task (on a 5-point Likert scale), and an accelerated visual picture–sentence matching task. HSs showed knowledge of the finiteness constraints on Spanish clitic placement in both production and comprehension, and their response times were close to those of the native speakers. Compared with the other experimental group in the study, L2 Spanish learners, HSs showed more native-like knowledge and use of clitics, an expected outcome given their early exposure to the language.

Bilingual children acquiring Spanish also performed generally on target by producing clitics in their grammatical positions, as shown in the study conducted by Pérez-Leroux et al. (2011). However, some of the responses in their two bilingual groups (simultaneous and sequential) showed enclitic bias, with children repeating a pre-verbal clitic as post-verbal in a quarter of their responses to proclitic sentences. No such bias was attested in the monolingual group studied by Eisenchlas (2003), which was used as a control group. At the same time, when asked to repeat sentences with enclitics, Heritage Spanish children used proclitics less often than monolingual children did in the same sentences. The authors attributed these performance differences to the age and length of exposure to English, a language that lacks functional projections for clitics. Particularly, they attributed the preference for enclitics and other bilingual-specific effects to a cross-linguistic syntactic transfer defined as ‘the result of activation changes in the selectional features associated with a lexical term’ (Pérez-Leroux et al. 2011, p. 230). Another explanation of the better performance with proclitics in Heritage Spanish compared with the baseline was suggested by Polinsky (2018), who analyzed these findings as an example of reduction in optionality or variability. Compared to the choice monolinguals have to make, that is, between enclisis and proclisis, the bilingual participants in the study by Pérez-Leroux and colleagues generalized either the proclitic or the enclitic position as the only one possible in particular contexts, thus streamlining this aspect of their grammar.

Studies of other HLs, in particular, European Portuguese (Rinke and Flores 2014) and Serbian (Dimitrijević-Savić 2008), also found evidence for clitic misplacement in their judgments. Rinke and Flores used untimed grammaticality judgments and discovered that HSs exhibited preference for enclitics in some of the contexts that required proclitics. The authors attribute this bias to the reduced experience that HSs have with formal registers. As already mentioned, child speakers of monolingual European Portuguese showed similar enclitic bias in their initial acquisition of clitic placement before they converge on target at around 4 years of age; however, bilingual children continued to manifest divergent patterns until much later (Costa et al. 2015). It is therefore likely that the incipient enclitic bias present in monolingual child European Portuguese is amplified in the grammar of adult HSs. The enclitic bias was also attested in the spontaneous production of Heritage Serbian speakers living in Australia (Dimitrijević-Savić 2008). In standard Serbian, clitics appear in second position of their intonational phrase, a prosodic requirement, which is enforced after the movement of the auxiliary and pronominal clitics takes place (Boskovic 2020).

The overview of the research on clitic placement in HLs shows that clitic misplacement could be due either to language-internal factors (including internal reanalysis or lack of experience with formal registers) or due to language transfer. In most of the languages studied so far, clitic placement is driven by morphological and syntactic factors. Serbian is the only language among the ones investigated in which clitic placement is subject to prosodic requirements. Our goal is to expand our inquiry into another language with clitics where prosodic well-formedness plays a role in their post-syntactic linearization. The perceptual sensitivity of HSs and their good control over salient suprasegmental cues have been documented (see Chang (2022) for an overview); hence, an investigation of clitic placement constrained by prosody in Bulgarian may help us to dissociate any inherent positional bias from the impact of language-internal factors.

2. Bulgarian Object Clitics: Syntactic and Prosodic Properties

2.1. General Overview

Clitics are prosodically, semantically, and syntactically deficient elements. Unlike nouns, they lack rich lexical content and are typically analyzed as instantiations of formal grammatical features, such as gender, number, and case (Baker and Kramer 2018; Franks 2017). These properties have consequences for their distribution, manifested in the Wackernagel position (e.g., in Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian—BCMS) or verb adjacency, such as in Bulgarian and Macedonian. When clitics appear in clusters, they have a fixed order, as the Bulgarian clitic Template (1) and Example (2) indicate.2

| 1. | ne > | šte > | săm > | IO clitic > | DO clitic > | e | |

| NEG | FUT | 1SgAUX | Dative | Accusative | 3sgAUX | (Hauge 1999) | |

| 2. | Štjal | săm | da | săm | ti | ja | pokazal |

| FUT | AUX-1Sg | Conj | AUX-1g | DAT | ACC | shown | |

| ‘I would have shown her to you.’ | |||||||

Bulgarian clitics are present in the verbal and the nominal domains. The former group includes direct and indirect object clitics (note that indirect object clitics are also present in the extended nominal domain), reflexives, auxiliaries, the clitic šte (the future marker), and the invariant interrogative particle li. Clitics are specified for gender (masculine, feminine, and neuter) only in 3Sg, and unlike in French, Italian, or Catalan, there is no clitic–past participle agreement (Varlokosta et al. 2016). Bulgarian does not have a case system; however, clitics have retained their case forms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bulgarian direct object clitics and strong pronouns.

Bulgarian clitics are in binary opposition with strong (tonic) pronouns. Only the latter are used in coordination (3), clefts (4), contrastive sentences (5), or as objects of prepositions (6); otherwise, clitics are the default option. Strong pronouns must always be referential, and unlike clitics, they can occur in theta positions.

| 3. | Vidjax | nego/*go | i | Maria | Coordination | |

| saw-1Sg | him-PR/CL | and | Maria | |||

| ‘I saw him and Maria.’ | ||||||

| 4. | Nego/*go | vidjax. | Clefts | |||

| him-PR/CL | saw-1Sg | |||||

| ‘It was him that I saw.’ | ||||||

| 5. | Nego/*go | vidjax, | a | ne | Maria | Contrast |

| him.PR/CL | saw-1Sg, | but | not | Maria | ||

| ‘I saw him, not Maria.’ | ||||||

| 6. | Otivam | pri | tjax/ | *gi. | Object of a preposition | |

| go-1Sg | to | them-PR | them-CL | |||

| ‘I am going to them (their house).’ | ||||||

2.2. Syntax–Prosody Interface: The Strong Start Constraint

Although syntax is necessary to determine the placement of Bulgarian object clitics, it is not sufficient. Typically, syntax places the clitics in proclitic position, but apparent post-syntactic operations can reposition them post-verbally, as enclitics, in order to avoid prosodic deviance (Franks 2017; Harizanov 2014; Pancheva 2005). This repositioning is triggered by a prosodic constraint on clitics and is captured by the following generalization (Harizanov 2014; see also Selkirk 2011 for general considerations):

| 7. | Strong | Start | Constraint |

The leftmost constituent of a Maximal Intonational Phrase (e.g., the Utterance) should not be a prosodically deficient element (i.e., such an element must be parsed inside a prosodic word).

The examples below show the operation of this constraint on clitics, (8a, b) and (9), but not on strong pronouns (10):

| 8a. | Maria | go | vidja | (canonical proclitic) | ||

| Maria | him-CL | saw-3Sg | ||||

| ‘Maria saw him.’ | ||||||

| Prosodic structure: [U[I[WMaria]] [I[go [Wvidja]]] | ||||||

| 8b. | *Maria | vidja | go | |||

| Maria | saw-3Sg | him-CL | ||||

| ‘Maria saw him.’ | ||||||

| 9. | Vidja | go | Maria | (enclitic because of Strong Start) | ||

| saw-3Sg | him-CL | Maria | ||||

| ‘Maria saw him.’ | ||||||

| Prosodic structure: [U[i[Wvidja] go] [I[WMaria]]] | ||||||

| 10. | Nego/*go | vidja | Maria. | |||

| him-PR/him-CL | saw-3Sg | Maria | ||||

| ‘It was him that Maria saw.’ | ||||||

In Example (8a) the clitics are linearized as canonical proclitics, whereas their placement as enclitics in Example (9) avoids a violation of Strong Start (Harizanov 2014). The repositioning of the canonical pre-verbal clitic in sentences with right dislocation of the subject, Maria (as in Example 9), is the outcome of the operation of Strong Start, which ‘saves’ the clitic go from being initial in its Utterance [u] after the movement of the subject. Thus, enclisis is grammatical in Bulgarian, but only when the host of the clitic is at the left edge of the clause and the clitic immediately follows it. When there are several XPs between the beginning of the clause and the enclitic, the enclitic is illicit, as shown in Example (8b).3

Previous analyses have employed a language-specific account to explain the non-initial restriction on Bulgarian clitics based on the so-called Tobler Mussafia Law (Franks 2017, 2021; Pancheva 2005). Despite the ostensible similarities between this account and the Strong Start Constraint, there are some important differences that implore us to use the latter in our analysis. First, the generalizations captured by the Strong Start Constraint are based on independent facts about the prosodic behavior of clitics in Bulgarian and Macedonian (see Harizanov 2014 for details). Second, these generalizations have broader scope than the restrictions imposed by the Tobler Mussafia Law because they explain the behavior of any prosodically deficient elements, not just clitics.

Bulgarian clitics can appear after any prosodically non-deficient elements, even if such constituents are prosodically lighter, such as conjunctions (11), the negative particle ne (12), or the future marker šte (13). However, only in two cases do they form a prosodic word with the element to their left. The first one is when the enclisis is triggered by the Strong Start Constraint and the clitic forms a prosodic word with its verbal host (14), and the second is with the negative particle, where the stress falls on the clitic (12).

| 11. | I | go | vidjax | v | parka. | Conjunction |

| and | him-CL | saw-1Sg | in the | park | ||

| ‘And I saw him in the park.’ | ||||||

| 12. | Ne | go | vidjax | v | parka. | Negative particle |

| no | him-CL | saw-1Sg | in the | park | ||

| ‘I did not see him in the park.’ | ||||||

| 13. | Šte | go | vidja | v | parka. | Future marker |

| will | him-CL | see-1Sg | in the | park. | ||

| ‘I will see him in the park.’ | ||||||

| 14. | Vidjax | go | v | parka. | ||

| saw-1Sg | him-CL | in the | park. | |||

| ‘I saw him in the park.’ | ||||||

In sum, Bulgarian object clitics are common in both spoken and written language and their placement is not dependent on semantic or pragmatic (i.e., Information Structure) factors. They reside at the syntax–phonology interface, and their phonological properties interact with certain prosodic constraints that prohibit them from appearing non-initially in their Utterance. Their placement is determined by a complex interplay of syntactic factors and prosodic positional readjustments. In contrast to clitics, strong (tonic) pronouns appear in the contexts where clitics are not permitted (see Examples 3–6). The complexities of the computation of the canonical (proclisis) and non-canonical (enclisis) clitic placement could potentially make clitics vulnerable in the conditions of reduced input and output, and in contact with a dominant language without clitics, such as English.

3. Research Questions, Hypotheses, and Predictions

Taking into consideration the findings of previous studies of clitic placement in HLs and the perceptual sensitivity of HSs, we can predict divergent processing of clitic placement in HB comprehension in comparison with the native baseline. Specifically, our two research questions are the following:

RQ1.

Do HB speakers show a preference for non-canonical enclitics? If yes, what are the causes of such preference?

RQ2.

Does the operation of the Strong Start Constraint have an impact on the processing of clitic placement by HB speakers?

If HB speakers’ comprehension diverges from that of baseline Bulgarian speakers, we assume two different sources for this. The first is direct cross-linguistic transfer (CLT) from the dominant language, English, as follows:

Hypothesis 1.

Clitics in HB are reinterpreted as strong pronouns (clitics = pronouns), due to direct CLT associated with the canonical post-verbal position of English pronouns. Particularly, as a result of the surface overlap between Bulgarian and English in the post-verbal position of direct object pronouns, clitics in HB are processed and accepted as grammatical in the ungrammatical post-verbal (enclitic) condition.

In a self-paced listening task, we predict that HSs will be slower than the baseline in their comprehension, as is often the case (Montrul 2016; Polinsky 2018). In the acceptability judgment task (AJT), they will rate post-verbal clitics higher as a result of direct CLT from English. However, we should keep in mind that in some cases, the divergent results of HSs could reflect a tendency to amplify a variation already present in the input and not a result of CLT (Rinke and Flores 2014; Flores et al. 2017). There is also the possibility that the clitic misplacement in heritage grammars (as discussed earlier for European Portuguese) mimics the protracted development of clitic placement in monolingual language acquisition, but, unlike the latter, it does not ultimately converge on the target placement. However, we should note that in contrast to European Portuguese, monolingual Bulgarian children attain the adult-like clitic placement of proclitics and enclitics from very early on, around the age of 2;3. (Ivanov 2008; Radeva-Bork 2012).

Our prediction, related to Hypothesis 1, is that the pre-verbal position for clitics, which is canonical in Bulgarian but ungrammatical in the context of English direct object pronouns, would result in longer reaction times (RTs) and lower ratings in HB compared with the baseline. Conversely, as a result of a direct CLT from English, HSs will have shorter RTs and higher ratings for the enclitic than for the proclitic position.

As a reminder, enclitics are ungrammatical in Bulgarian only when they are not subject to post-syntactic prosodic requirements in the form of the Strong Start Constraint. We did not test HSs on contexts directly targeting Strong Start (beginning of the sentence, as in Example 10) because this would have obscured the possible effects of CLT (cf. Ivanov 2009 for similar considerations about English L2 learners of Bulgarian). However, the surface overlap between clitics and the English object pronouns exists in both the grammatical and the ungrammatical enclitic contexts in Bulgarian, thus making access to their representation a much more onerous task for HB speakers.

In view of these considerations, we suggest that if satisfied, our prediction would indicate that HB speakers reanalyze Bulgarian clitics as English object pronouns independently of the representation of the Bulgarian strong pronouns in their grammar. A more detailed comparison of clitics and strong pronouns in Heritage Bulgarian would require a different study that would take into consideration their binary opposition, the prosodic (atonic–tonic) and structural (non-branching–branching) differences between them, as well as pragmatic effects, such as contrastive focus in the placement of strong pronouns pre- and post-verbally.

Our second hypothesis is related to the complexity of clitic computation; we predict that processing of the clitic placement in HB will be more uniform than in the baseline.

Hypothesis 2.

Clitics grammar in HB is the same as in the baseline (clitics ≠ pronouns), but HSs process and accept clitics in a uniform manner across contexts regardless of their syntactic and prosodic constraints.

If speakers interpret different options in clitic placement as instances of free variation, that could be attributed either to language-internal variation or CLT. In the former case, if pre-verbal and post-verbal clitics are rated equally high, we assume a representation that allows for both positions of the object clitics indiscriminately (unlike English, which sanctions only post-verbal direct object pronouns). Such representation presupposes at least partial sensitivity to Strong Start because of its role in the post-syntactic repositioning of the clitics. The uniform treatment of both clitic positions would then stem from the overextension of the Strong Start Constraint to any enclitic position, not just the one associated with the prosodically deviant left edge of the clause.

Alternatively, under a more holistic view of CLT, HSs would rate ungrammatical enclitics equally high (or low) because there is no clitic functional projection in English, unlike in Bulgarian. Under both the language-internal and the external accounts, HB speakers are expected to process the canonical (proclitic) and non-canonical (enclitic) position in a uniform way. Our hypotheses and predictions are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Hypotheses and predictions for each task for the HSs group.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Self-Paced Listening Task

4.1.1. Participants

We had 2 groups of participants in our study: 13 English-dominant, highly proficient speakers of HB (Mage = 25) and 22 monolingual Bulgarian speakers (Mage = 30). All were recruited via social media and were compensated for their participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the City University of New York, the University of New Mexico, and the University of Maryland. It was carried out in accordance with ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

A short, 10-question sociolinguistic questionnaire asked participants about their age, gender, level of proficiency in spoken and written Bulgarian, age of arrival in the English-speaking country, level of formal education completed in Bulgaria, frequency, and sources of communication in Bulgarian, and so forth. Of the HSs, 4 were born in an English-speaking country, the rest arrived there between the ages of 1 and 14 (Mage of arrival = 4.3). Earlier studies have reported that variance in the age of arrival, as well as immigration after the first decade in life, does not affect HL fluency and language control (Shishkin and Ecke 2018). Moreover, all our participants reported high proficiency in spoken (3.00) and written Bulgarian (3.15) on a scale from 1 to 4 (4 being fluent). On average, they speak Bulgarian 22.8 h a week, ranging from 3 to 100 h. Most of them did not receive formal education in Bulgaria, and the ones who did completed only their elementary education. Due to the relatively small number of the participants, we did not divide this group further.

4.1.2. Materials, Design, and Procedure

The study included 16 experimental items and 16 fillers. Each experimental item consisted of context that introduced the antecedents of the clitics and a target sentence that contained a clitic or an NP that were placed in pre- or post-verbal position). We manipulated the grammaticality of the position of the clitics (grammatical pre-verbal vs. ungrammatical post-verbal) and the group (HSs vs. baseline) in a 2 × 2 experimental design. The sentences with the NPs were designed as controls and were not directly compared to the clitic conditions because of NP longer duration compared with the clitics. We decided to include NPs in the same positions (pre-verbal and post-verbal) as clitics in order to assure the lack of ‘yes’ bias in judgments and verify that HSs were paying attention to the different elements in object positions. As mentioned earlier, a direct comparison between clitics and strong (tonic) pronouns in the same positions would have confounded several variables.

A total of 16 items (4 per condition) were distributed across 4 lists in a Latin square design and were interspersed with 16 filler items in a pseudo-randomized order. There were 4 experimental conditions, as shown in Table 3: 2 conditions with clitics (Conditions 1 and 2) and 2 with NPs (Conditions 3 and 4). The experimental items in each list contained 8 sentences with clitics (4 in Condition 1 and 4 in Condition 2) and 8 with NPs (4 in Condition 3 and 4 in Condition 4).

Table 3.

Conditions and ROI.

The canonical placement of object clitics in Bulgarian is pre-verbal, as shown in Condition 1. Clitics can also appear post-verbally, but only if the pre-verbal clitics violate the prosodic Strong Start Constraint by appearing initially in the Utterance. Because there is no such violation in Condition 2 (there are several XPs before the clitic), the post-verbal clitic is ungrammatical. In contrast, the canonical position of the NP in Bulgarian is post-verbal (Condition 3), whereas its pre-verbal placement is infelicitous (Condition 4).

The target sentence shown in Table 3 is divided into regions of interest (ROI): pre-critical region 1–pre-critical region 2–subject–pre-verbal object–verb–post-verbal object–post-critical region. The pre-verbal and post-verbal objects could be either clitics or nouns depending on the condition. Our focus is on the verb, the post-verbal object and the post-critical region (due to the spillover effect). All participants listened to the experimental sentences word by word in the self-paced listening task (Papadopoulou et al. 2014) by pressing the space bar after each word in order to advance to the next item. Their reaction times for the three ROIs above were recorded and analyzed.

The study was hosted on the FindingFive platform for behavioral research and took place remotely. It took the participants between 45 and 60 min to complete all the components of the study: the consent form, instructions, audio check, a short written sociolinguistic questionnaire with 10 questions, 4 practice items, and 16 experimental items (8 target items and 8 fillers). The consent form and the questionnaire were the only ones that were written in both Bulgarian and English.

The study was conducted remotely on a computer, with headphones in order to enhance the quality of the sound. The participants were instructed to complete the study in a single sitting, without any interruptions, which most of them did, according to their time stamps. The answers from the questionnaire were used to divide the participants into two groups, i.e., HSs and monolinguals.

4.2. Acceptability Judgment Task

4.2.1. Participants

The participants who completed the self-paced listening task completed the AJT.

4.2.2. Materials, Design, and Procedure

The Acceptability Judgment Task was performed right after the participants completed the self-paced listening task, and thus, both tasks were completed in a single session. Particularly, the instructions in the beginning of the study asked the participants to listen to all the sentences (the context and the target sentence) but evaluate only the last one, the target sentence. In order to draw the participants’ attention to that sentence, a short two-second tone was played before the sentence started. The participants progressed through it word by word (because it was part of the self-paced task), and after they reached the end, they were presented with a five-point scale for evaluating its acceptability, with labels in Bulgarian:

| 1 | absoljutno nepriemlivo | ‘absolutely inacceptable’ |

| 2 | donjakude nepriemlivo | ‘somewhat unacceptable’ |

| 3 | donjakude priemlivo | ‘somewhat acceptable’ |

| 4 | priemlivo | ‘acceptable’ |

| 5 | absoljutno priemlivo | ‘absolutely acceptable’ |

The use of a gradient instead of a binary Likert scale avoids the tendency for judgments towards the end points of the scale (Haussler and Juzek 2017). Second, the aural presentation of AJT avoids potential literacy issue in the HSs group because of their diverse background in formal education. Furthermore, it allows us to tap more directly into the speakers’ implicit knowledge as compared with a presentation of the stimuli in written form (Plonsky et al. 2020). Finally, having both tasks (self-paced listening and AJT) in the same aural modality creates more coherence in the experimental session.

5. Results

Follow-up comprehension questions were administered after half of the target items. The other half was followed by the message ‘Click here to proceed’. This was done to hold the participants’ attention. The HSs’ answers to the comprehension questions were less accurate as compared with the baseline (81% vs. 90%). We included data from participants who did not answer the comprehension questions correctly. We decided to do that because their RTs had a normal distribution, without large variations although we had to exclude five HSs because of such variations. Additionally, an inaccurate response on a comprehension question was not essential for the objective of the task, which focused on a grammatical property, rather than a semantic one. Finally, self-paced listening is a less natural test than some other traditional behavioral experiments, which may account for a higher rate of incorrect responses to comprehension questions.

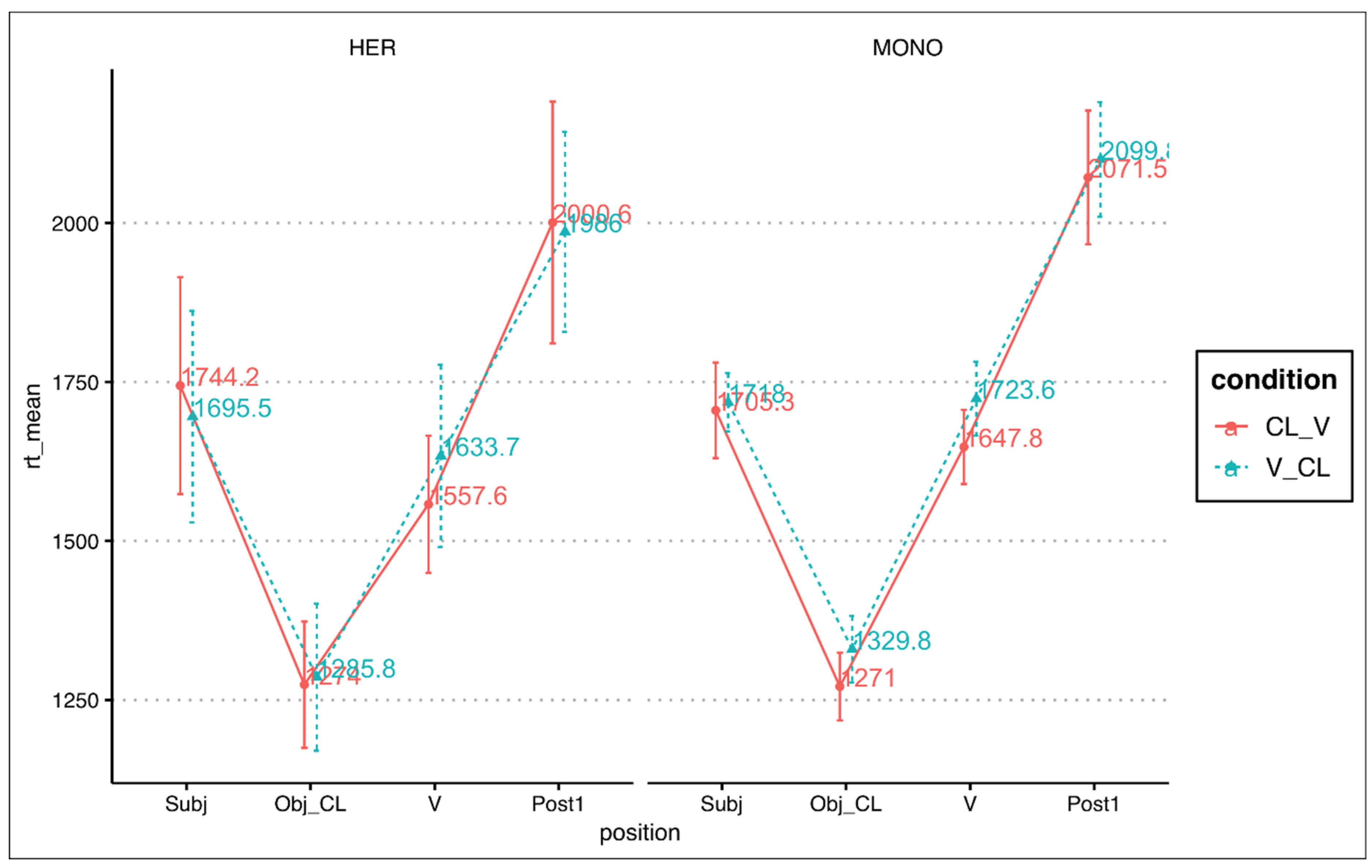

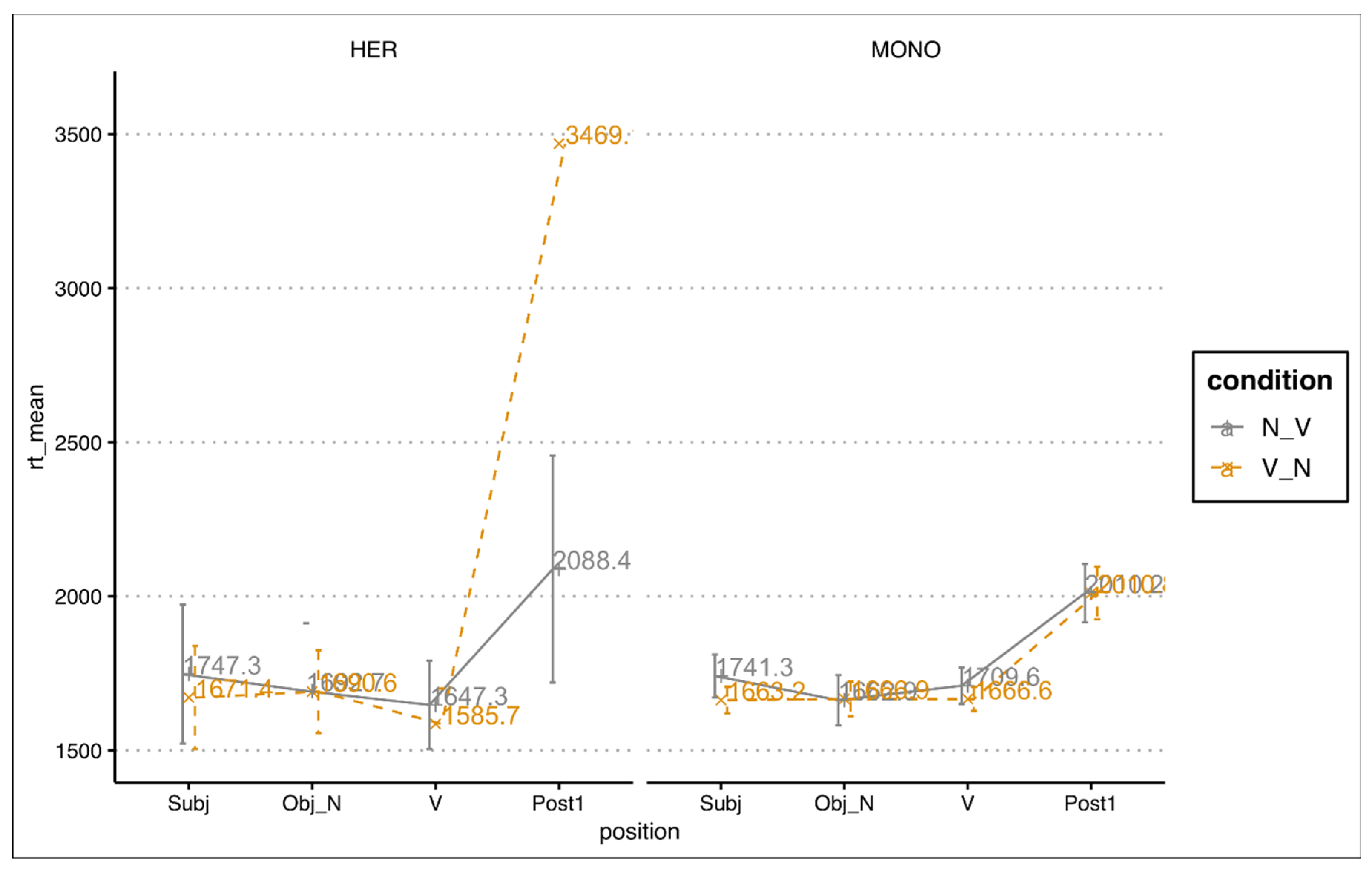

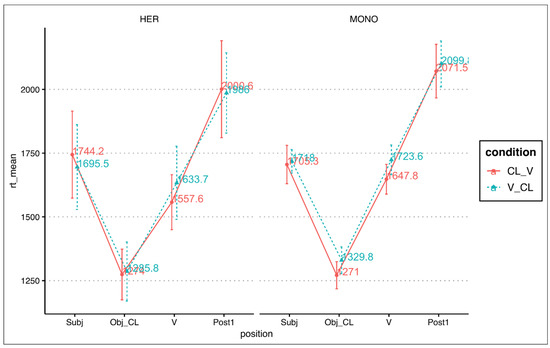

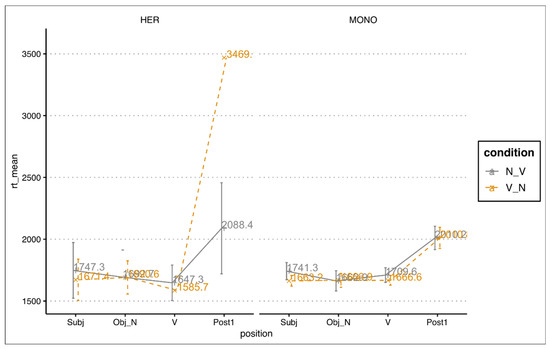

5.1. Self-Paced Listening

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show participants’ mean RTs and confidence intervals by condition (clitics vs. NPs), position in the sentence, and group (heritage vs. baseline). Table 4 reports the results of the mixed-effects models in the log-transformed RTs. Our analysis did not show any effect of group, condition, or position (ROI), thus demonstrating that the two groups have similar processing outcomes. Particularly, the processing pattern in the HS group did not differ between the grammatical (proclitic) and the ungrammatical (enclitic) condition, thus ruling out the enclitic bias. Interestingly, the baseline behaved the same way, although this outcome could have concealed different processing strategies.

Figure 1.

HS and baseline mean RTs of object clitics in Conditions 1 and 2.

Figure 2.

HS and baseline mean RTs of NPs in Conditions 3 and 4.

Table 4.

Response times: simple effects by group.

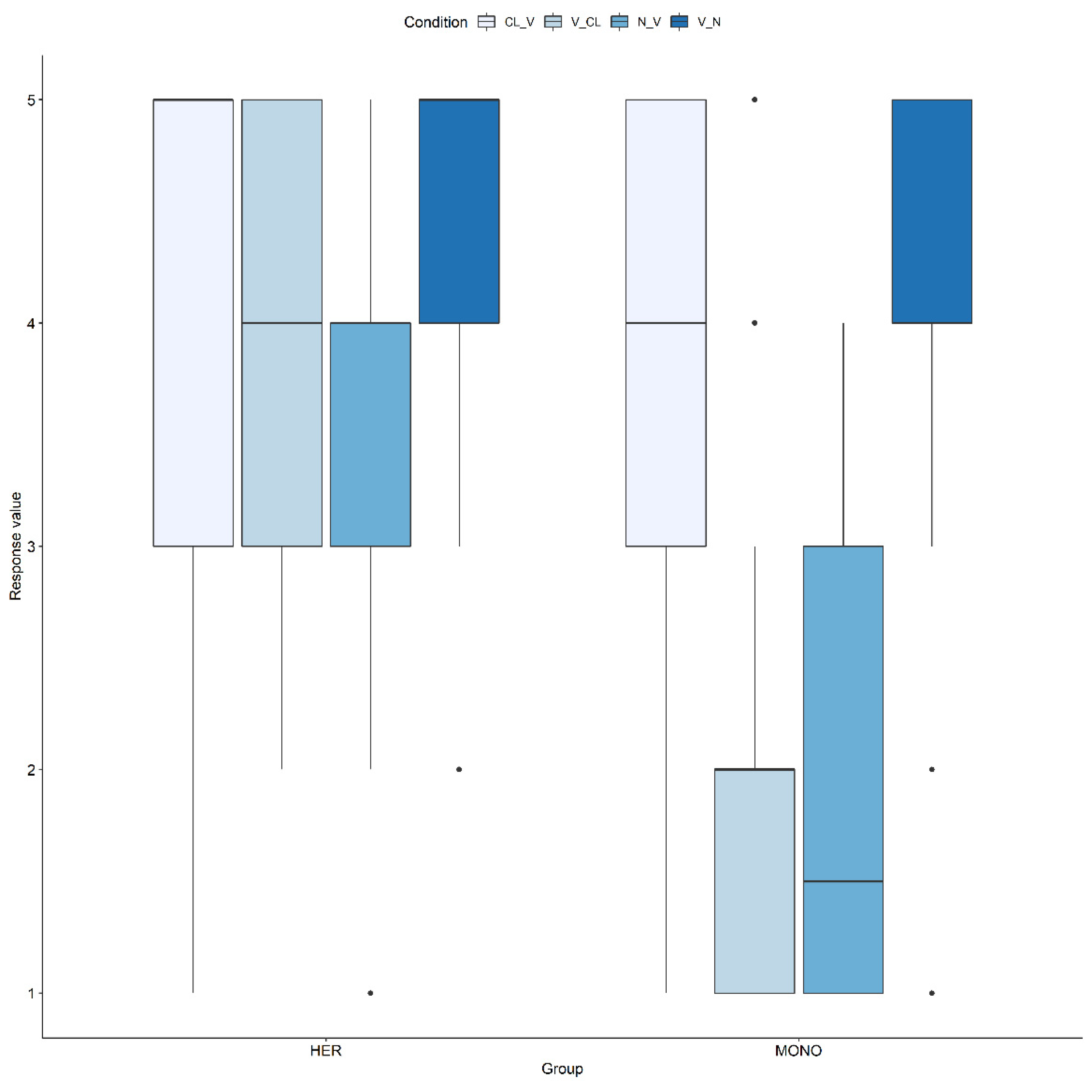

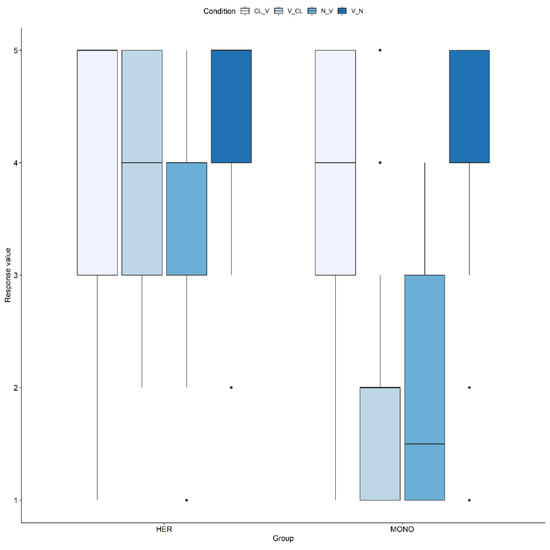

5.2. Acceptability Judgment Task

The box plot in Figure 3 shows the median values of group ratings of object clitics and NPs. The mean acceptability ratings by condition are provided in Table 5. Finally, Table 6 and Table 7 report the results of the mixed-effects model by rating across groups and within groups, respectively. As Table 6 shows, we did not find any difference in acceptability judgments between the two groups in the grammatical (proclitic) condition, only in the ungrammatical one (t = −9.076; p < 0.001). These results parallel the control conditions with the NPs, showing group difference only in the infelicitous Condition 4 (t = −8.375; p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

HS and baseline ratings of object clitics and NPs.

Table 5.

Means of heritage and baseline ratings of clitics and NPs.

Table 6.

Ratings in AJT: simple effects across groups.

Table 7.

Ratings in AJT: simple effects within groups.

No grammaticality effect was attested in the HS group, but such an effect was quite robust in the baseline (t = 13.9347; p < 0.001), with lower ratings for the ungrammatical enclitic position. The two groups converged on their ratings of the NP conditions distinguishing between Condition 3 and Condition 4 (HSs: t = −3.6561; p = 0.005; and baseline: t = −16.4613; p < 0.001). This result demonstrates that HSs do not exhibit a simple ‘yes’ bias across the board (on the ‘yes’ bias in HSs, see Orfitelli and Polinsky 2017; Polinsky 2018) but have metalinguistic skills that are on par with the baseline, at least in respect to some placement positions.

We ran subsequent analyses only on the HS group, in which we excluded the two participants who came to the country at a late age (between 12 and 14) in order to rule out the age of onset of the dominant language as a factor. The results were the same as before, pointing towards other variables with possible impact on the performance in that group.

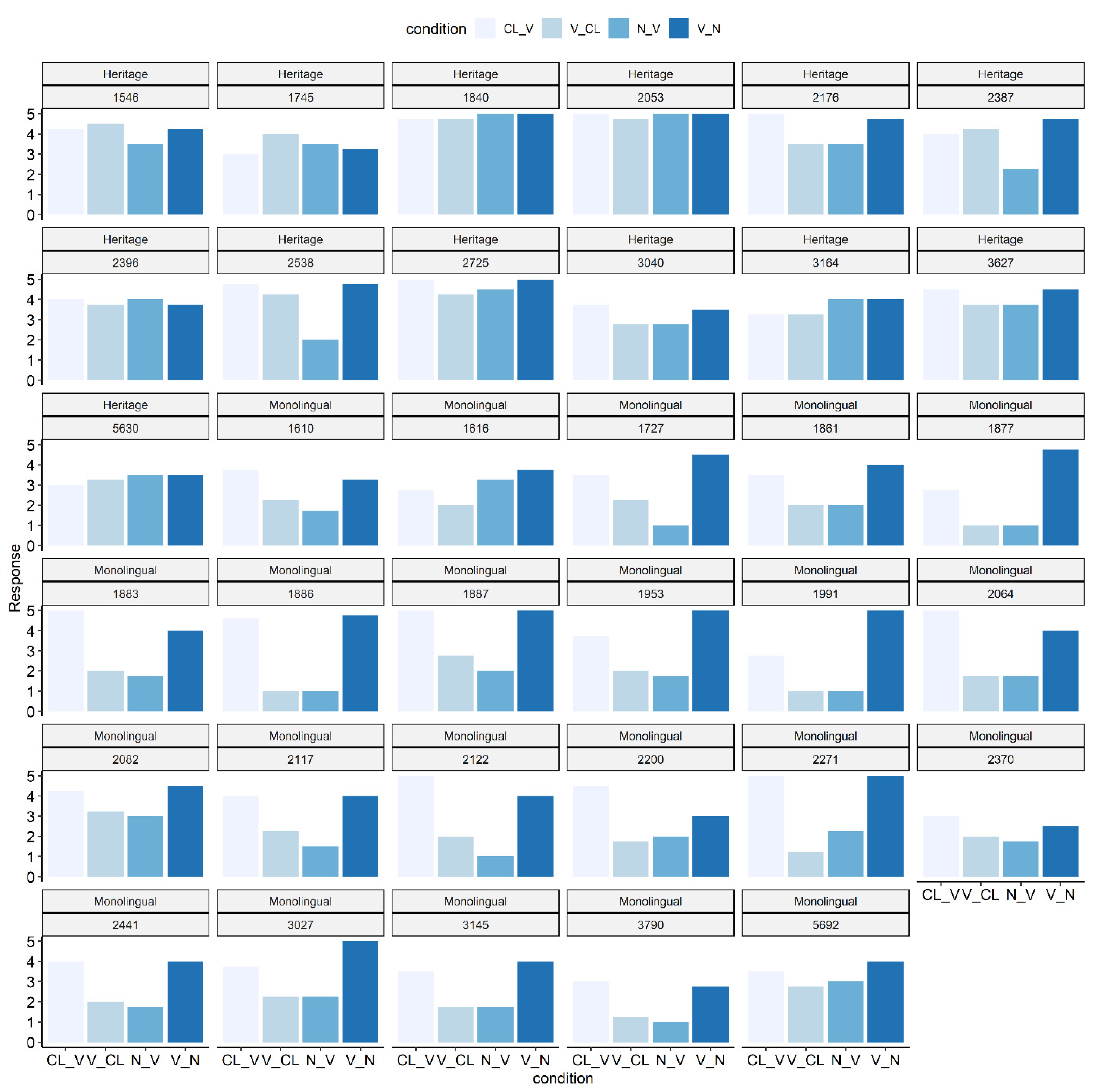

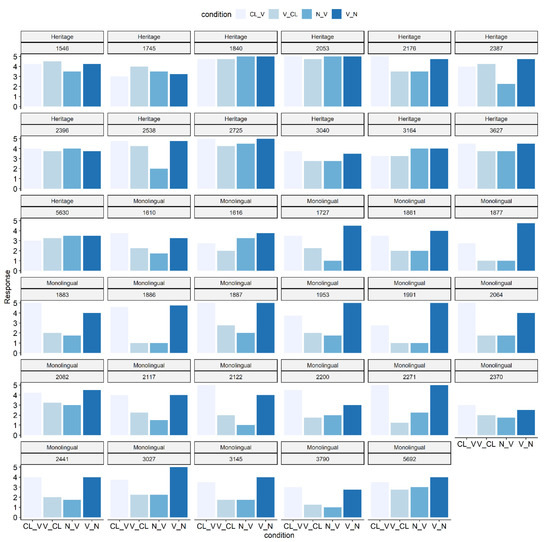

The heterogeneity of the HS group prompted a closer look at the individual results. Figure 4 shows the means of the acceptability judgments in the four conditions for each participant (in both groups). The HS group presents a larger divergence with qualitatively different ratings compared with the baseline. All the participants in the monolingual group discriminated between the two clitics and two NP positions. However, this was not the case in the HS group, where only four participants judged the two-clitic position differently and three (different) participants discriminated between the two NP positions. Only one heritage speaker discriminated between all four positions. Due to the relatively small size of that group, it is difficult to generalize about the factors that could have impacted the internal variability. For example, heritage participants No. 1840 and No. 2053 did not discriminate between the two clitics or NP positions despite their similar sociolinguistic profiles (born in the US/came to the US at the age of 1, weekly communication in Bulgarian amounts to 3 h, no formal education, good speaking and reading proficiency). On the other hand, participant No. 3040, who has a similar background but differs in the amount of Bulgarian per week (14 h), rated clitics, and NPs qualitatively similar to the baseline. In future studies the level of reading proficiency and years of formal education could be explored further in order to determine the influence of these factors on the performance of HSs with clitics.

Figure 4.

Individual results in AJT in heritage and baseline (MONO) groups.

6. Discussion

The goal of the present study was to determine whether clitic placement is vulnerable in heritage language comprehension as compared with clitic realization, which supposedly shows overall resilience in heritage languages (see Polinsky 2018; Polinsky and Scontras 2020). The mixed findings on clitic placement in previous HL studies came from languages in which either finiteness (Spanish), syntactic operators (European Portuguese), or syntactic–prosodic factors (Bosnian–Serbian–Croatian–Macedonian) drive the computation of clitic placement. In order to probe further the impact of prosodic factors on clitic placement in Bulgarian, a language with proclitic–enclitic variation, we tested HB speakers on their comprehension of clitic placement in an online and offline task.

We found that the HB speakers processed the grammatical proclitic and the ungrammatical enclitic positions the same way, thus confirming Hypothesis 2, namely, that HSs differentiate clitics from pronouns. The results in the HS group were similar to the baseline but we argue that this similarity between the two groups is ostensible and only shows processing outcomes, not routines or patterns. In a previous (unpublished) study with a different group of Bulgarian monolinguals, in which we used the same materials but with self-paced reading, baseline participants were faster in the grammatical placement of the clitics than in the ungrammatical placement, as expected. Given the lack of stress and the short length of the object clitics, it is possible that they are less salient in auditory mode than in writing. Thus, it is possible that the lack of grammaticality effect in the baseline processing of clitic placement in the present study is affected by the modality, namely, the difference between auditory and written sentences. Similar inhibitory impact of auditory modality on the performance in self-paced listening has been documented in earlier studies (Murphy 1997; Wong 2001).

In contrast to the online processing, where the HSs’ RTs were similar to those of baseline, their offline AJT judgments of clitic placement were poorer in comparison to the baseline. This differs from their clear distinctions in the NPs rating in which the infelicitous pre-verbal NP placement was judged low, similar to the baseline. That again suggests that heritage speakers differentiate between clitics and NPs in regard to the placement of direct objects. The lack of shorter RTs or higher ratings of the ungrammatical enclitics in the present study distinguishes HB from heritage Serbian and heritage European Portuguese and raises questions about precisely what it is that triggers morphosyntactically and prosodically driven clitic placement in HLs more broadly.

The uniform behavior of our HS group in the online and offline tasks suggests that HSs do not discriminate between the grammatical and ungrammatical position of the clitics. In their grammar, clitics can appear anywhere in the sentence, unlike direct object pronouns in English, and in contrast to clitics in Serbian, which have strict linear order requirements imposed by prosody. Clitics in Bulgarian could be left- or right-adjacent to the verb with variable distance from the left edge of the clause as a result of syntactic computations and subsequent prosodic readjustments (Harizanov 2014; Franks 2017, 2021). Which factors that govern this variable placement in baseline Bulgarian could have been the sources of the uniform interpretation of clitic positions in Heritage Bulgarian? Given the lack of prosodically driven clitic placement in the dominant language, we could assume lower sensitivity to the prosodic domains of the clitics in Heritage Bulgarian. This could have made the distance of the clitics from the leftmost edge of the clause rather arbitrary and could have resulted in overextension of the prosodically driven canonical enclisis (XP CL) at the left edge of the maximal Phonological Phrase to other non-canonical contexts inside the Phonological Phrase (XP XP CL), with the resulting global enclisis in HB. In other words, the only licit utterance-initial enclisis constrained by Strong Start becomes licit in any position of the Phonological Phrase. In general, if the HB speakers are not so sensitive to prosodic parsing, the word-by-word presentation of the target sentence in auditory mode could have also contributed to their uniform ratings of the two clitic positions in the auditory AJT. However, this manner of presentation did not impact the ratings of the baseline speakers, showing prosodically well-formed representations, with a fully operational Strong Start.

The uniform treatment of proclitics and enclitics by HB speakers lessens the need of computing all prosodic and syntactic dependencies in clitic placement, reducing the processing load of clitic computation. Of course, the overgeneralization of the Strong Start Constraint could be viewed as a complication: after all, yet another constraint is added to the post-syntactic operations, which may strain (rather than relieve) resources. However, Strong Start is part of the baseline, so it is not added in HB. Instead, the constraint is reanalyzed as fully global in that it applies regardless of the prosodic boundaries (edges). No added computational cost is associated with this change.

Finally, there is yet another possibility, that the equally high ratings of both proclitic and enclitic conditions by the HSs manifest their uncertainty as to which position is grammatical (i.e., without imposing new constraints). It is difficult to say which one of these explanations is more plausible without widening the scope of our experimental conditions. However, regardless of the root cause, such behavior is reminiscent of the optionality reduction manifested either in the proclitic or enclitic generalization by child HSs of Spanish in some contexts (Pérez-Leroux et al. 2011; Polinsky 2018). In both Heritage Spanish and Bulgarian, such reduction would solve the problem of the onerous choice between proclitics and enclitics that rests on the knowledge of complex grammatical and prosodic constraints.

7. Conclusions

Our investigation of clitic placement in Heritage Bulgarian uncovered an intact clitic grammar that clearly differs from the grammar of English direct object pronouns. HB speakers gave high ratings to the canonical non-argument position of the clitic (the pre-verbal position), which shows that they are not reinterpreting clitics as pronouns, contrary to Hypothesis 1. On the other hand, the uniform treatment of enclitics and proclitics by HSs in the self-paced listening and AJT is evidence of optionality in clitic computation and could have resulted either from language-internal factors or the absence of the target structure in the dominant language, English. In the former case, we suggested that the lack of fully integrated operation of the prosodic Strong Start Constraint in Heritage Bulgarian leads to interpreting the distance of the clitic from the left edge of the clause as ‘arbitrary’, one that could range from one XP (in the case of canonical enclitics) to several XPs (non-canonical enclitics).

Another source of language-internal optionality in the interpretation of the clitic placement could be HSs’ reduced sensitivity to prosodic domains and boundaries, particularly due to a prosodic constraint in English, similar to Strong Start but at the right edge of the clause (cf. the analysis of stranded prepositions in English in Harizanov (2014)). However, in order to confirm such a hypothesis, we need to add experimental contexts that distinguish between different prosodic domains, such as Utterance and Intonational Phrase.

Although the explanations presented above are compelling, we cannot rule out the role of a more general CLT in the uniform processing of clitic placement by the English-dominant HB speakers in our study. In particular, the lack of clitics in English compared with the complex interplay of clitics and strong pronouns in Bulgarian could cause uncertainty in HSs about the canonical status of clitic positions. To fully evaluate this possibility and to determine the most plausible explanation of the clitic placement pattern documented here, we need to extend the scope of our study by including contexts with strong (tonic) pronouns in those positions where canonical direct object pronouns are found in English. In more general terms, investigations of clitics in HLs could fine-tune our understanding of CLT, especially in cases of surface overlap and structural differences between the heritage and the dominant language.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.I.-S., I.A.S. and M.P.; methodology, T.I.-S., I.A.S. and M.P.; software, D.T.; validation, T.I.-S. and I.A.S.; formal analysis, T.I.-S. and I.A.S.; investigation, T.I.-S.; data curation, T.I.-S., D.T. and I.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.I.-S.; writing—review and editing, T.I.-S., D.T., I.A.S. and M.P.; visualization, D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The second author (IAS) was partially supported by the PSC-CUNY grant #64464-00-52 and by the Center for Language and Brain NRU Higher School of Economics, RF Government Grant ag. No. 14.641.31.0004. The fourth author (MP) was partially supported by NSF grant BCS-1619857.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of New Mexico (IRB # 07520, 20 April 2020), College of Staten Island (IRB # 2020-0322, 30 July 2020) and University of Maryland (IRB # 766233-25, 15 June 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The stimuli for the study can be found on https://www.iris-database.org/iris/app/home/detail?id=york:939969, accessed on 2 October 2021.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Prosodic constraints are not included in the cited discussion of interface problems, but the reasoning applied to other interface phenomena can be extrapolated to these constraints as well. |

| 2 | Abbreviations follow the Leipzig Glossing Rules. The symbol * indicates ungrammaticality. |

| 3 | Unlike the prosodic deviations with initial clitics, Information Structure factors, such as focus, drive the use of the strong pronoun nego, as shown in Example (10). |

References

- Baker, Mark, and Ruth Kramer. 2018. Doubled Clitics Are Pronouns: Amharic Objects (and Beyond). Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 36: 1035–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul, and Maria Polinsky. 2013. Heritage Languages and Their Speakers: Opportunities and Challenges for Linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics 39: 129–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskovic, Zeljko. 2020. On the Syntax and Prosody of Verb Second and Clitic Second. In Rethinking Verb Second. Edited by Rebecca Woods and Sam Wolfe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 503–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Charles. 2022. Phonetics and Phonology. In The Cambridge Handbook of Heritage Languages and Linguistics. Cambdridge: Cambdridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, João, Alexandra Fiéis, and Maria Lobo. 2015. Input Variability and Late Acquisition: Clitic Misplacement in European Portuguese. Lingua 161: 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dimitrijević-Savić, Jovana. 2008. Convergence and Attrition: Serbian in Contact with English in Australia. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 16: 57–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duarte, Inês, and Gabriela Matos. 2000. Romance Clitics and the Minimalist Program. In Portuguese Syntax: New Comparative Studies. Edited by João Costa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 116–42. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenchlas, Susana. 2003. Clitics in Child Spanish. First Language 23: 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Cristina, Esther Rinke, and Anabela Rato. 2017. Comparing the Outcomes of Early and Late Acquisition of European Portuguese: An Analysis of Morpho-Syntactic and Phonetic Performance. Heritage Language Journal 14: 124–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, Steven. 2017. Syntax and Spell-Out in Slavic. Bloomington: Slavica Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, Steven. 2021. Microvariation in the South Slavic Noun Phrase. Bloomington: Slavica Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann, Kleanthes K., and Theoni Neokleous. 2015. Acquisition of Clitics: A Brief Introduction. Lingua 161: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harizanov, Boris. 2014. The Role of Prosody in the Linearization of Clitics: Evidence from Bulgarian and Macedonian. Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics 22: 109–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hauge, Kjetil Ra. 1999. A Short Grammat of Contemporary Bulgarian. Bloomington: Slavica Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Haussler, Jana, and Tom Juzek. 2017. Hot Topics Surrounding Acceptability Judgement Tasks. In Proceedings of Linguistics Evidence 2016: Empirical, Theoretical, and Computational Perspectives. Edited by Sam Featherson, Robin Hornig, Reinhild Steinberg, Birgit Umbreit and Jennifer Wallis. Tubingen: University of Tubingen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionin, Tania, and Teodora Radeva-Bork. 2017. The State of the Art of First Language Acquisition Research on Slavic Languages. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 25: 337–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Ivan. 2008. L1 Acquisition of Bulgarian Object Clitics—Unique Checking Constraint or Failure to Mark Referentiality. In Proceedings from the 32 Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Harvey Chan, Heather Jacob and Enkeleida Kapia. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, Ivan. 2009. Second Language Acquisition of Bulgarian Object Clitics: A Test Case for the Interface Hypothesis. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA. Available online: http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/300 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Kim, Ji Young. 2019. Heritage Speakers’ Use of Prosodic Strategies in Focus Marking in Spanish. International Journal of Bilingualism 23: 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Ji Young. 2020. Discrepancy between Heritage Speakers’ Use of Suprasegmental Cues in the Perception and Production of Spanish Lexical Stress. Bilingualism 23: 233–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laleko, Oksana, and Maria Polinsky. 2017. Silence Is Difficult: On Missing Elements in Bilingual Grammars. Zeitschrift fur Sprachwissenschaft 36: 135–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2010. How Similar Are Adult Second Language Learners and Spanish Heritage Speakers? Spanish Clitics and Word Order. Applied Psycholinguistics 31: 167–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2016. The Acquisition of Heritage Languages. Cambdridge: Cambdridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Victoria A. 1997. The Effect of Modality on a Grammaticality Judgement Task. Second Language Research 13: 34–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykhaylyk, Roksolana, and Aldona Sopata. 2016. Object Pronouns, Clitics, and Omissions in Child Polish and Ukrainian. Applied Psycholinguistics 37: 1051–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neokleous, Theoni. 2015. The L1 Acquisition of Clitic Placement in Cypriot Greek. Lingua 161: 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orfitelli, Robyn, and Maria Polinsky. 2017. When Performance Masquerades as Comprehension: Grammaticality Judgments in Experiments with Non-Native Speakers. Quantitative Approaches to the Russian Language 2017: 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancheva, Roumyana. 2005. The Rise and Fall of Second-Position Clitics. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 23: 103–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, Despina, Ianthi Tsimpli, and Nikos Amvrazis. 2014. Sefl-Paced Listening. In Research Methods in Second Language Psycholinguistics. Edited by Jill Jegerski and Bill VanPatten. London: Routledge, pp. 50–68. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Leroux, Ana Teresa, Alejandro Cuza, and Danielle Thomas. 2011. Clitic Placement in Spanish-English Bilingual Children. Bilingualism 14: 221–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perez-Leroux, Ana Teresa, Mihaela Pirvulescu, and Yves Roberge. 2017. Direct Objects and Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petinou, Kakia, and Arhonto Terzi. 2009. Clitic Misplacement Among Normally Developing Children and Children with Specific Language Impairment and the Status of Infl Heads. Language Acquisition 10: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plonsky, Luke, Emma Marsden, Dustin Crowther, Susan M. Gass, and Patti Spinner. 2020. A Methodological Synthesis and Meta-Analysis of Judgment Tasks in Second Language Research. Second Language Research 36: 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2018. Heritage Languages and Their Speakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Gregory Scontras. 2020. Understanding Heritage Languages. Bilingualism 23: 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radeva-Bork, Teodora. 2012. Single and Double Clitics in Adult and Child Grammar. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Rinke, Esther, and Cristina Flores. 2014. Morphosyntactic Knowledge of Clitics by Portuguese Heritage Bilinguals. Bilingualism 17: 681–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Selkirk, Elisabeth. 2011. The Syntax–Phonology Interface. In The Handbook of Phonological Theory, 2nd ed. Edited by John Goldsmith, Jason Riggle and Alan Yu. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 435–84. [Google Scholar]

- Shishkin, Elena, and Peter Ecke. 2018. Language Dominance, Verbal Fluency, and Language Control in Two Groups of Russian–English Bilinguals. Languages 3: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, Leher, and See Kim Seet. 2019. The Impact of Foreign Language Caregiving on Native Language Acquisition. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 185: 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2012. Pinning down the Concept of Interface in Bilingual Development: A Reply to Peer Commentaries. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 2: 209–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella, and Franceses Filiaci. 2006. Anaphora Resolution in Near-Native Speakers of Italian. Second Language Research 22: 339–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimpli, Ianthi, and Antonella Sorace. 2006. Differentiating Interfaces: L2 Performance in Syntax-Semantics and Syntax-Discourse Phenomena. Paper Present at the Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development, Boston, MA, USA, November 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Varlokosta, Spyridoula, Adriana Belletti, João Costa, Naama Friedmann, Anna Gavarró, Kleanthes K. Grohmann, Maria Teresa Guasti, Laurice Tuller, Maria Lobo, Darinka Anđelković, and et al. 2016. A Cross-Linguistic Study of the Acquisition of Clitic and Pronoun Production. Language Acquisition 23: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, Wynne. 2001. Modality and Attention to Meaning and form in the Input. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 23: 345–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).