1. Introduction

Code-switching is a natural and commonly occurring phenomenon; it can be observed in the speech and writing of multilinguals who go back and forth between their languages in the same conversation or text (e.g.,

Deuchar (

2012)). As the following English-

Spanish examples demonstrate, code-switching happens both between (1a) and within (1b) clauses.

| (1a) | Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish, | y termino en español | |

| | | and I finish in Spanish | (Poplack 1980) |

| (1b) | Estaba snowing | | |

| | it was | | (Miccio et al. 2009) |

It is generally accepted that code-switching is not a random process (cf.

Labov (

1971)), but is a rule-governed speech practice, indicative of high proficiency in, and active use of, both/all of a speaker’s languages (e.g.,

Poplack (

1980)). Speakers choose when, where and with whom to code-switch, and intuitively regulate the switch points. Code-switching may also facilitate language production: recent evidence suggests that habitual code-switchers have a higher global speech rate in bilingual mode (i.e., when they are code-switching) than when they are unilingual mode (i.e., not switching;

Johns and Steuck (

2021); cf.

Meuter and Allport (

1999)). Nonetheless, the regularities and innovations observable in code-switched speech can—and should—inform theories of (multilingual) grammar more broadly (e.g.,

Toribio (

2017);

López (

2020)).

The rules governing code-switching have, to date, largely been formulated in terms of structural constraints, such as the subject pronoun-verb constraint (e.g.,

MacSwan (

1999) for Spanish-Nahuatl; see also

MacSwan (

2021)). Yet these constraints are often based on data from a small number of language pairs, sometimes just (one community of) Spanish-English speakers. Studies focusing on the same constraint or switch site may also use different methodologies, making their results less comparable and thus the overall claims less convincing (see, e.g.,

Parafita Couto et al. (

2021) for an overview). Moreover, there is an expanding body of evidence to indicate that code-switching patterns are also modulated by community norms (e.g.,

Blokzijl et al. (

2017)). There is, therefore, a clear need to expand the empirical base to test existing constraints, especially with typologically varied languages. The present study contributes to this broadening of the evidence base by focusing on the subject pronoun-verb constraint in P’urhepecha-Spanish bilinguals in Michoacán, Mexico.

1.1. Background

According to early studies, switches between a subject pronoun and a finite verb were dispreferred or even impossible (see

Lipski (

1978) on Spanish-English judgements;

Timm (

1975) on Mexican Spanish-US English production data from California; see also

Lipski (

2019);

van Gelderen and MacSwan (

2008)). An example of such a switch can be observed in the English-

Spanish example in (2a). In contrast, and as highlighted by

Fuertes et al. (

2016), a switch between a full lexical DP and a finite verb continues to be considered acceptable, see (2b).

However, as has been the case for many proposed constraints, counter-evidence for a (near-)ban on subject pronoun-verb switches soon emerged (see

Toribio (

2017) for a critique of the prevailing claim and counter-claim culture in code-switching research). This evidence stems from several sources, including a spoken corpus of

French-Moroccan Arabic in Morocco, compiled by

Bentahila and Davies (

1983), see (3a, 3b).

Two noteworthy points emerge from these examples: first, the switch can go in both directions; in other words, a pronoun from French or Moroccan Arabic can be followed by a verb (and other elements) in the other language of the pair. Second, the behaviour of the two switch directions is not the same (see

Deuchar (

2020) for a discussion of directionality in code-switching). In (3a), the French discourse-emphatic pronoun

moi ‘me’ combines directly with the Arabic finite verb, even though in unilingual French mode, the personal pronoun

je ‘I’ would be used to express the subject. In contrast, in (3b) there is doubling between the discourse-emphatic Arabic pronoun

nta ‘you’ and the French personal pronoun

tu ‘you’ (see also the discussion of the Matrix Language Frame (MLF) model below).

On the basis of evidence such as that presented in (3a, 3b), it has been claimed that the grammaticality of the subject pronoun-verb switch is modulated by the typology or features of the pronouns involved (see

Cardinaletti and Starke (

1999)). To this end, two approaches have been proposed to account for (un)acceptable switches: Generativism/Minimalism on the one hand, and the Matrix Language Frame model on the other.

1.2. Generativist/Minimalist Approaches

Coordination, e.g., tú y yo ordered … (you and I)

Modification, e.g., él con el pelo negro ordered … (him with the black hair)

Prosodic stress, e.g., pero ÉL ordered … (HE)

Clefts, e.g., dijo que es él que ordered … ([she] said that it is he who)

Subject pronouns are considered to be syntactically akin to lexical DP subjects in these contexts (they are ‘strong’, as in example (2b)), thereby licensing the switch (see also

Koronkiewicz (

2020)). In

MacSwan’s (

1999) Nahuatl-Spanish judgement data, however, switches are constrained by the person of the pronoun: a Spanish (underlined) subject pronoun followed by a Nahuatl verb is only acceptable for the third person (4a, 4b).

| (4a) | Él kikoas tlakemetl | | | |

| | Él | ø-ki-koa-s | tlake-me-tl | |

| | he | 3S-3Os-buy-FUT | garment-PL-NSF1 | |

| | ‘He will buy clothes’ | | | (MacSwan 1999, p. 129) |

| (4b) | *Yo nikoas tlakemetl | | | |

| | Yo | ni-k-koa-s | tlake-me-tl | |

| | I | 1S-3Os-buy-FUT | garment-PL-NSF | |

| | ‘I will buy clothes’ | | | (MacSwan 1999, p. 129) |

These judgements also hold when the subject pronoun is postponed to the end of the clause, as indicated in (5a, 5b).

| (5a) | Kitlalia tlantikuaske nochipa él | | | | |

| | ø-ki-tlalia | tlantikuaske | nochipa | él | |

| | 3S-3Os-prepare | food | daily | he | |

| | ‘He prepares food every day’ | | | | (MacSwan 1999, pp. 129–30) |

| (5b) | *Niktlalia tlantikuaske nochipa yo | | | | |

| | ni-k-tlalia | tlantikuaske | nochipa | yo | |

| | 1S-3Os-prepare | food | daily | I | |

| | ‘I prepare food every day’ | | | | (MacSwan 1999, pp. 129–30) |

The permitted switch with the third person pronoun in Spanish corresponds to the absence of overt third-person subject marking in Nahuatl (

MacSwan 1999, pp. 128–29). A different picture emerges, however, when the switch is between a Nahuatl subject pronoun and a Spanish verb; here switches are degraded for the first person (marked by ‘?’), and unacceptable for other persons, see (6a, 6b).

| (6a) | ?Ne tengo (una) casa ‘I have a house’ | |

| (6b) | *Te tienes (una) casa ‘You have a house’ | (MacSwan 1999, p. 130) |

The second person is especially unacceptable due to the similarity between the Spanish te (second person singular clitic/reflexive) and Nahuatl te (second person singular subject pronoun), which are phonetically identical but syntactically behave very differently.

1.3. MLF Approach

The MLF assumes an asymmetry between the languages participating in a code-switched clause. One language—the matrix language—provides the system morphemes, that is, morphemes that do not assign thematic roles (e.g., finite verb morphology), while the other language—the embedded language—generally provides content morphemes, such as nouns, which do assign or receive thematic roles (

Myers-Scotton 1993,

2002). The matrix language of a clause is identified on the basis of two principles: the Morpheme Order Principle (MOP) and the System Morpheme Principle (SMP). The MOP indicates the language that provides the word order for the clause, while the SMP indicates which language provides the system or functional morphemes, such as finite verb morphology.

In an MLF analysis, then, it is necessary to establish what kind of morphemes the personal pronouns are in a given language, namely system or content.

Jake (

1994) identifies four types of subject pronoun cross-linguistically (underlined and in boldface type in column two), two of which are classified as content morphemes, and two as system morphemes (see

Table 1).

The classification of subject pronouns is language-specific but, irrespective of the language, only those that are classified as content morphemes can participate in switches with verbs (

Myers-Scotton 1993;

Jake 1994) In

Table 1, therefore, only discourse-emphatic (as in examples in (3) and (4), above) and indefinite personal pronouns can participate in code-switches. These two types of pronoun would be considered akin to lexical DP subjects in a Minimalist analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of the present study is to investigate subject pronoun-finite verb code-switching preferences among P’urhepecha-Spanish bilinguals in Mexico. P’urhepecha is a language isolate spoken in the state of Michoacán by around 125,000 people, the majority of whom are bilingual with Spanish, the main national language of education, administration, commerce, etc. (

INEGI 2010). The language has been the subject of scholarly investigation since the mid-sixteenth century, when some of the earliest descriptive and lexicographic works in the Americas appeared (e.g.,

Gilberti [1559] 1975,

[1558] 1987). The modern era has provided only one full-length grammar (

Chamoreau 2000), although shorter works, including grammar sketches (and a whole host of articles on specific topics) are also available (e.g.,

Foster 1969;

Friedrich 1984;

Capistrán Garza 2015, chp. 1;

Bellamy 2018, chp. 1).

P’urhepecha is a wholly suffixing, agglutinative language with extensive derivational resources, including a large set of spatial location suffixes (e.g.,

Friedrich 1971;

Monzón 2004;

Mendoza 2007). It possesses both subject pronouns and subject (and object) clitics, which may co-occur in the same clause (see (7), taken from the first author’s own corpus (

Bellamy, forthcoming)).

| (7) | T’ueskiri? |

| | t’u-e-s-ki = ri |

| | you-PRED-PERF-INTERROG = 2.SG.S |

| | ‘You are?’ |

Both P’urhepecha and Spanish have first, second and third person pronouns, with all three occurring in both the singular and the plural. That said, the third person pronouns are marked for different features: Spanish has a masculine/feminine distinction (

él, ella ‘he, she’), while the P’urhepecha pronouns indicate distance and visibility in relation to the speaker (

i ‘this, proximal’,

inte ‘that, distal and visible’,

ima ‘that, distal, not visible’).

Table 2 provides an overview of the two subject pronoun paradigms.

Moreover, third person pronouns in P’urhepecha are synchronically identical to the demonstrative pronouns. Depending on the location of the person (or object) in relation to the speaker, any of the three forms can therefore be used by a P’urhepecha speaker. In (8a), the third person plural distal visible

ts’ïmi functions as a personal pronoun, whereas in (8b), it functions as a demonstrative pronoun.

| (8a) | Ts’ïmi sapirhastiksï | |

| | ts’ïmi | sapi-rha-s-ti = ksï |

| | 3.PL | small-SF.PL-PERF-3.S.ASS = 1/3.S |

| | ‘They are small.’ | |

| (8b) | Ts’ïmi kurucha sapirhastiksï | | |

| | ts’ïmi | kurucha | sapi-rha-s-ti = ksï |

| | 3.PL | fish | small-SF.PL-PERF-3.S.ASS = 1/3.S |

| | ‘Those fish are small.’ | | |

Note also that the inclusion of the personal pronoun in (8a) is optional since subject person marking is present in the form of the clitic = ksï. Alternatively, the clitic could be omitted, but then the pronoun would be required to differentiate between first and third person plural, if context could not. As such, it seems that third person pronouns in P’urhepecha could be considered strong (in the Minimalist/generativist sense) or discourse-emphatic and, thus, content morphemes (in the MLF sense).

2.1. Research Questions

On the basis of previous findings, as well as the differences between the two sets of subject pronoun systems in P’urhepecha and Spanish, two principal research questions and associated hypotheses were formulated. The first tests the Minimalist/generativist proposal that only strong or contextually lexical pronouns are acceptable in code-switches, while the second tests the MLF prediction that only content morphemes can partake in pronoun-verb switches.

- RQ1:

Are strong or contextually lexical pronouns, namely, coordinated pronouns (e.g., tú y yo, t’u ka ji ‘you and I’), more acceptable than less lexical ones (e.g., nosotros, jucha ‘we’) in pronoun-verb switches?

- Expectation:

Coordinated pronouns are more acceptable than non-coordinated pronouns.

- RQ2:

Are content morphemes (e.g., P’urhepecha ima ‘s/he, that’) more acceptable than system morphemes in switches?

- Expectation:

The third-person pronouns in P’urhepecha may be preferred as they are also demonstratives and can be considered content morphemes, while the others (and all those in Spanish) could be considered system morphemes and, thus, dispreferred.

2.2. Stimuli

Three subject pronouns were used from each language (Spanish and P’urhepecha): 1SG,

yo/ji ‘I’, 1PL coordinated,

tú y yo/t’u ka ji ‘you and I’, and 3SG

él/ella/ima s/he’ (distal, non-visible in P’urhepecha). For each pronoun we generated five sentences with the switch going from P’urhepecha to Spanish and five from Spanish to P’urhepecha. Each pair of sentences differed in the subject pronoun, which was always sentence-initial, and its verbal agreement. This gave us a total of 15 pairwise comparisons in each switch direction. Examples of such pairwise comparisons can be found in (9a–9c), where the P’urhepecha subject pronouns are underlined.

| (9a) | ji trabajo cada día hasta las 10 | 1SG vs. 3SG |

| | ima trabaja cada día hasta las 10 | |

| | ‘I//s/he work(s) every day until 10.’ | |

| (9b) | ji corro muy lentamente | 1SG vs. 1PL |

| | t’u ka ji corremos muy lentamente | |

| | ‘I // you and I run very slowly.’ | |

| (9c) | ima canta canciones tradicionales | 3SG vs. 1PL |

| | t’u ka ji cantamos canciones tradicionales | |

| | ‘S/he//you and I sing traditional songs.’ | |

Sentences with the opposite switch direction (Spanish to P’urhepecha) take the same form, but only the subject pronoun is in Spanish (see

Appendix A for a full list of the stimuli).

2.3. Task

Participants completed a two-alternative forced-choice acceptability judgement task (2AFC) administered through Qualtrics. In the 2AFC task participants are presented with successive pairwise comparisons of exemplars belonging to all the relevant conditions and are asked to select one preferred item from each pair. The 2AFC task has been shown to be a good method for measuring subjective judgements (

Stadthagen-González et al. 2018). Comparative judgments present multiple advantages over other methods used for acceptability judgements such as Yes/No acceptability tasks and Likert-type scales (see, e.g.,

Párraga (

2015)), including higher inter- and intra-participant reliability (

Mohan 1977); higher statistical power (

Sprouse 2011), and more sensitivity to contrasts between conditions (

Stadthagen-González et al. 2018).

The task consisted of 30 experimental stimuli (five per condition × two switch directions), 40 fillers, and eight quality control items. For each item, participants saw two code-switched sentences and were asked to choose which sounded more natural to them. Experimental stimuli consisted of pairwise comparisons between all the relevant conditions described above, while filler items contrasted code-switched sentences with different gender-assignment strategies for nouns (the analysis of those items has been reported in (

Bellamy et al. 2018). The quality control items included code-switched sentences containing an incorrect subject-verb agreement in both languages (four in P’urhepecha, four in Spanish). The criterion for exclusion from the study was set at three or more incorrect answers for these quality control questions, but there was no need to exclude any participants based on this criterion. The order of presentation of items, as well as the order of each member of a pair within an item, was individually randomized for each participant. The 2AFC task was completed first, followed by a sociolinguistic questionnaire.

2.4. Participants

Twelve participants (six female) with an average age of 27;9 years (range = 21;6–37;9, SD 5.1) took part in the experiment. All are P’urhepecha-Spanish bilinguals, 11 of whom were born in Michoacán, and all were living there at the time of testing. Nine participants reported acquiring P’urhepecha from birth to two years, two from the age of four and one from primary school onwards. Only one participant (the same who started speaking P’urhepecha at primary school) reported learning Spanish from birth to two years and so represents the only early sequential Spanish-P’urhepecha bilingual in the sample. Of the P’urhepecha L1 speakers, two reported learning Spanish from age four or earlier, six from primary school, one from secondary school, and one as an adult. Regarding current language use, only one participant reported speaking only P’urhepecha at home and with friends. Three use half-half P’urhepecha and Spanish, while five use a lot of P’urhepecha and a bit of Spanish, and the final three, a lot of Spanish and a bit of P’urhepecha in the same contexts.

Participants also self-reported frequency of and attitudes towards code-switching. One participant reported using P’urhepecha and Spanish in the same sentence every day, four reported that they did so a few times a week, one once a week, two a few times a month, two less than once a month, and two stated that they never engaged in such a practice. To the statement, “people should avoid mixing P’urhepecha and Spanish in the same conversation”, responses varied across the spectrum: two were totally in agreement, four in agreement, two neither agreed nor disagreed, two were in disagreement and two totally disagreed.

3. Results

Data from the forced-choice responses were analysed using

Thurstone’s (

1927) analysis for comparative judgements case V. The measures resulting from Thurstone’s analysis can be interpreted as values on an interval scale that represent the acceptability of the code-switched sentences and are relative to the pattern with the lowest acceptability for each direction of switch (which is, by convention, set to 0). The unit of measurement along that scale is defined as the standard deviation of the distribution, so the measure itself provides information about its variability.

Stadthagen-González et al. (

2018) provide further details on the use of this type of analysis in code-switching research. We calculated the confidence intervals using

Montag’s (

2006) method, which was specifically developed for paired comparison data. The 95% confidence interval for the data collected was ±0.15.

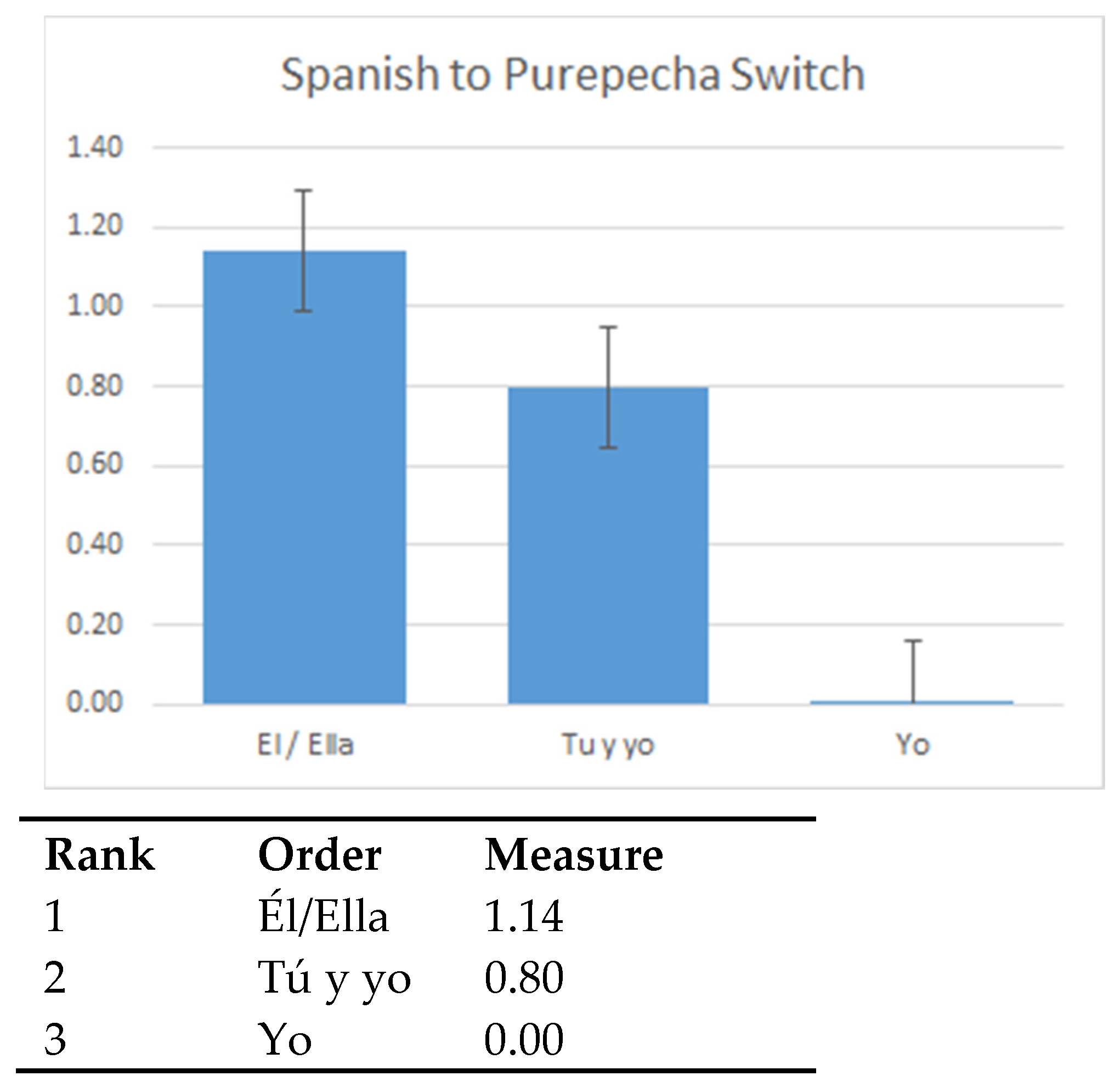

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 summarise the results of our analysis for Spanish to P’urhepecha and P’urhepecha to Spanish switches, respectively. For both switch directions, the third person singular pronoun is preferred well above the other two options. Second in preference is the coordinated ‘you and I’ pronoun, followed by the first person singular, again for both switch directions. In the case of a Spanish subject pronoun and a P’urhepecha verb, the differences between each rank (i.e., each pronoun) are all significant (see

Figure 1).

While the rank ordering is the same for P’urhepecha to Spanish switches, only the difference between 1SG and the other two conditions (1PL coordinated and 3SG) is significant (see

Figure 2). The difference between 3SG and 1PL coordinated conditions approaches significance and, in all likelihood, this difference would become significant with a few more participants.

2These results are rather unexpected. Following,

inter alia,

González-Vilbazo and Koronkiewicz (

2016), we would expect the coordinated 1PL pronoun in Spanish to be more acceptable than the weak 3SG or 1SG, but this is not what we find. Indeed, despite Spanish

él/ella ‘s/he’ being weak pronouns/system morphemes, and P’urhepecha

ima ‘s/he’ a strong pronoun/content morpheme, both are the most acceptable choice for the participants.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The main finding of the present study is that code-switches involving a 3SG pronoun and a finite verb were considered the most accepted for both switch directions, followed by coordinated 1PL, and then 1SG. On the basis of previous studies, we predicted that coordinated pronouns would be more acceptable in switches than non-coordinated pronouns (RQ1). This prediction was clearly not borne out by the findings. That 3SG is acceptable in both directions also contrasts with

MacSwan’s (

1999) judgement findings for Spanish-Nahuatl, where the 3SG pronoun was only accepted when it occurred in Spanish. We could therefore view the present results as an example of language-specific patterns in code-switching, since a universal ordering cannot be sustained. In the absence of results from another P’urhepecha-Spanish bilingual community, it is perhaps unwise to claim that the patterns are also community-specific. Nevertheless, it seems clear that previous claims regarding the acceptability of pronoun-verb switches should be revised in light of these new data.

We also predicted that third person pronouns in P’urhepecha would be preferred as they could be considered content morphemes, while the other pronouns (and all those in Spanish) could be considered system morphemes and thus dispreferred (RQ2). In Minimalist/generativist terms, the lexically strong 3SG in P’urhepecha would be preferred over the other, lexically weak pronouns. This prediction was partially upheld, since 3SG was the preferred pronoun for switches, but both strong (i.e., P’urhepecha ima ‘s/he’) and weak (i.e., Spanish él ‘he’) behaved identically, contrary to predictions.

However, this result is not necessarily that surprising, given the results of previous studies.

Parafita Couto and Stadthagen-Gonzalez (

2019), for example, find that the norms of the Spanish-English bilingual community under investigation were to express no preference for a particular switch direction in mixed NPs. This lack of preference is observed in two types of judgement tasks (forced-choice and Likert scale), despite naturalistic production data in the same language pair showing far more switches from Spanish to English, i.e., that Spanish functions overwhelmingly as the Matrix Language. We could view this as a difference between receptive and productive language.

A similar situation seems to hold for P’urhepecha-Spanish: in a corpus of around ten hours (

Bellamy, forthcoming), P’urhepecha is overwhelmingly the Matrix Language in code-switched speech (although it should be highlighted that this may not be true of all P’urhepecha-Spanish-speaking communities). Given the attested directionality preference in production, we might therefore expect speakers to have less clear judgements in their less frequent switch direction and, thus, follow the judgements they would make for switches in the more frequent direction. A similar finding emerged from an acceptability judgement task measured with event-related potentials (ERP):

Vaughan-Evans et al. (

2020) found that Welsh-English bilinguals only differentiated between adherence and violation conditions when the matrix language of the stimulus was Welsh, i.e., for Welsh to English code-switches.

That said, it is acknowledged that despite their richness and ecological validity, corpus data are not exhaustive, and not all naturally occurring structures will appear in a given corpus, irrespective of its size. Moreover, corpora are not probative in nature, but rather can be used to generate hypotheses and construct experimental materials (

Stadthagen-González et al. 2018). As we saw above, it is possible for receptive and productive language to not fully overlap (yet both being part of a person’s language competence), and for those differences to be reflected in specific tasks. Consequently, judgement tasks provide a valuable means of testing—and potentially falsifying—these generated hypotheses in a controlled, more probative, way than could be accomplished with corpus-based research alone. As also indicated above, the forced-choice format also has advantages over scaled or yes/no judgement tasks, since the latter are more likely to be affected by extra-linguistic factors such as attitudes and also display weaker intra- and inter-participant reliability (see, e.g.,

Párraga (

2015)). Indeed, this study also highlights the benefit of using a 2AFC judgement task: despite the wide range of attitudes towards code-switching reported by the participants (see

Section 3), the results are very clear.

In sum, the findings of the present study indicate that the patterns of subject pronoun-finite verb code-switches vary between language pairs, rather than constituting universal constraints of code-switching behaviour. More data from this and other communities is necessary to expand our understanding of the limits of this particular code-switch, amongst many others. Code-switched language reveals combinatorial possibilities that would otherwise be hidden in monolingual speech, and so is vital for refining grammatical theory (see

Vanden Wyngaerd (

2021) for an overview). In addition, the results highlight both the advantage and the need for data to be collected using multiple methods (see also

Parafita Couto et al. (

2021);

Gullberg et al. (

2009)). More extensive, comparable data will help us to tease apart the relationship between acceptability and usage patterns. The ultimate goal of such work, therefore, is to test and refine existing models of code-switching in order to improve our understanding of (multilingual) language competence.