Abstract

Subject-verb agreement mismatches have been reported in the L2 and heritage literature, usually involving infinitives, analyzed as default morphological forms for fully specified T-heads. This article explores the mechanisms behind these mismatches, testing two hypotheses: the default form and the surface-similarity hypotheses. It compares non-finite and finite S-V mismatches with subjects with different persons, testing whether similarity with other paradigmatic forms makes them more acceptable, controlling for the role of verb frequency. Participants were asked to rate sentences on a Likert scale that included (a) infinitive forms with first, second and third person subjects, and (b) third person verbal forms with first, second and third person subjects. Two stem-stressed verbs (e.g., tra.j-o ‘brought.3p.past’) and two affix-stressed verbs (e.g., me.ti-o ‘introduced.3p.past’), varying in frequency were tested. Inflectional affixes of stem-stressed verbs are similar to other forms of the paradigm both phonologically and in being unstressed (tra.j-o ‘brought.3p.past’ vs. trai.g-o ‘bring.1 p.pres’), whereas affixes of affix-stressed verbs have dissimilar stress patterns (me.ti-o ´introduced.3p.past’ vs. me.t-o ‘introduce.1p.pres’). Results show significantly higher acceptability for finite vs. non-finite non-matching, and for 1st vs. 2nd person subjects. Stem-stressed verbs showed higher acceptability ratings than affix-stressed ones, suggesting a role for surface-form correspondence, partially confirming previous findings.

1. Introduction

Spanish has a generalized agreement between the subject and the verb, realized as systematic variation in the inflectional morphology of the verb depending on the features of the subject. For example, in (1)a, -o encodes 1st person singular on the verb to match the person features of the subject, whereas in (1)b, the affix -e indicates 3rd person singular to match a 3rd person subject. The property of agreement is thus indirectly encoded in the inflectional morphology of the verb. In certain cases, verbal morphology is not completely transparent in the sense that the same morpheme can encode different person/tense combinations, as seen in (2), where the affix for a 1st person, present tense is the same as the affix for a 3rd person preterit.

- (1)

- a. Yo com-o.I eat-1sg‘I eat.’b. Ella com-e.she eat-3sg‘She eats.’

- (2)

- a. Yo traig-o.I bring-1sg.pres‘I bring.‘b. Ella traj-oshe brought--3sg.past

Heritage speakers, who can be characterized as speakers exposed to a minority language at home from birth in the context of a socially dominant majority language show, in some cases, variability with respect to subject-verb agreement, which we will call agreement mismatches. On the one hand, as (3) illustrates, instances of infinitives in main clauses (so-called root infinitives) have been documented among low proficiency heritage speakers (Camacho n.d. to appear, among others, see below) and also late bilinguals (see Liceras et al. 1999 and Prévost and White 2000). The infinitive in (3) appears in a root clause and since it is unmarked for a person, it fails to agree with the subject. Adult root infinitives of this type are not possible in monolingual Spanish (for cases where root infinitives with different properties are possible, see Hernanz 1999).1

- (3)

Y él llama-r mi papá. (Camacho n.d. to appear) and he call-inf my dad ‘And he call my dad.’

On the other hand, some low proficiency heritage speakers produce examples in which what looks like a 3rd person singular verb agrees with a 1st person singular subject, as seen in (4)a; and similar mismatches have been reported in heritage Hungarian, Egyptian Arabic, in addition to heritage Spanish (see Sánchez 1983; Bolonyai 2007; Albirini et al. 2011; Silva-Corvalán 2014; Rodríguez and Reglero 2015, among others). By contrast, the general consensus is that adult Spanish monolinguals and possibly advanced proficiency heritage speakers would typically produce traj-e, as in (4)b. The difference between root infinitives and person-mismatched finite verbs is that the former lacks person features whereas the latter has them. Put another way, (3) involves lack of agreement, whereas in (4)a the 1st person features of the subject and the 3rd person features of the verb clash.

- (4)

a. Entonces yo traj-o todos los papeles. (* for monolinguals) then I brought-3sg al the papers ‘Then I brought all the papers.’ b. Entonces yo traj-e todos los papeles. (acceptable) then I brought-1sg all the papers ‘Then I brought all the papers.’

Neither root infinitives nor person-agreement mismatches have been studied in depth in the heritage language literature, although they are well-documented in the production of L2 speakers. Assuming that the mentions in the HS literature point to real phenomena, even if infrequent, they raise several interesting questions: is there a systematic relationship between root infinitives and person-agreement mismatches? If so, is this relationship related to linguistic representations or to proficiency (or to both)? Relatedly, what determines the morphological shape of the verbal form? Finally, does language contact play a role?

This paper tests the acceptability of root infinitives and person-agreement mismatches among heritage speakers with higher proficiency levels, and it advances a hypothesis about one potential factor that determines the morphological shape of the verbal form in Spanish. Specifically, I capitalize on the observation that certain forms in the Spanish verbal paradigm are similar and that this similarity improves acceptability (see below). Specifically, comparing infinitival verbal forms, which are not similar to other forms in the paradigm to mismatched finite forms, which may be similar to others, allows us to assess whether surface similarity is the relevant notion. As we will see below, previous studies have argued for an alternative explanation for adult root infinitives, suggesting that they appear because they are analyzed as default forms (see Prévost and White 2000 and below). This study will compare the predictions of those alternative explanations.

1.1. The Representation of Non-Target Inflection in Bilinguals

In general, verb agreement morphology is an area where heritage and monolingual speakers diverge less, for example, in Hindi (Montrul et al. 2012), Russian and other languages, as noted by Benmamoun et al. (2010, 2013). However, several studies have shown examples like (3)–(4)a with an infinitive and a mismatching finite verb respectively. Infinitives are arguably not specified for a person, whereas finite forms have fully specified person features that clash with the features of the subject in (4)a (McCarthy 2006, p. 205). Prévost and White (2000) document instances of root infinitives in the spontaneous production of adult L2 speakers of French and German, which they analyze as cases in which a fully specified syntactic tense head is mapped to underspecified morphology, in what is known as the missing surface inflection hypothesis (see also Liceras et al. 1999 and Herschensohn 2001). These adult L2 infinitives are different from child root infinitives, which have been analyzed as not being fully inflected T heads (see Pierce 1989; Grinstead 1994; Guasti 1994; Rizzi 1994; Wexler 1994; Haegeman 1995; Phillips 1996; Lasser 1997; Hoekstra and Hyams 1998; Ezeizabarrena 2002, 2003; Hyams 2005; Liceras et al. 2006, a.o.).

In Prévost & White’s account, infinitives can appear in root contexts in adult language because the rule that guides morpheme insertion to the abstract syntactic nodes relaxes the conditions under which it applies. Normally, a syntactic tense node specified as [+FINITE] must be matched with a morpheme that is equally specified as [+FINITE], but for these speakers, the feature [±FINITE] of the morpheme becomes an underspecified [αFINITE] and can, therefore, match a syntactic feature specified as + or − [FINITE]. Prévost & White’s analysis thus relies on two notions: feature underspecification (from a ± value to an underspecified α value) and the notion of a ‘default’ form, namely the idea that an underspecified morphological feature ([αFINITE] in this case) may match a more specified syntactic feature ([+FINITE], for example). In this sense, a default form is a less specified form.(i)

McCarthy (2006) found that the majority of L2 agreement “errors” in the spontaneous production of intermediate L2 Spanish speakers constitute underspecification cases (92%), which she analyzed as cases where the underspecified 3rd person morpheme is inserted in the terminal node instead of the more specified 1st or 2nd person morpheme. VanPatten et al. (2012) challenged these results, noting that their study did not find an asymmetry in the combination of person or number features their participants are sensitive to, as one would expect if 3rd person were underspecified. Their study analyzed reaction times in agreement matching and non-matching S-V sentences using a moving window paradigm, comparing low proficiency L2 and native Spanish speakers. Their study included two separate groups of stimuli: the first group combined 1st and 3rd person subjects with either matching verbs (yo tomo ‘I.1sg drink.1sg’, Pedro toma ‘Pedro.3sg drinks.3sg’) or mismatching verbs (*yo toma ‘I.1sg drink.3sg’ or *Pedro tomo ‘Pedro.3sg drink.1sg’); the second group combined 2nd person singular and 3rd person plural subjects with either matching verbs (tú tocas ‘you.2sg play.2sg’, ellos tocan ‘they.3pl play.3pl) or mismatching verbs (tú tocan ‘you.2sg play.3pl, ellos tocas ‘you.3sg play.2sg’). If 3rd person singular is the underspecified form, one would expect asymmetrical response times for items containing the 3rd person default form compared to non-default ones. However, their L2 speakers did not show sensitivity to any of the person/number combinations, that is, reaction times were not significantly different between yo tomo ‘I.1sg drink.1sg’ and *yo toma ‘I.1sg drink.3sg’. It is important to note that McCarthy’s and VanPatten et al.’s studies differ with respect to the proficiency level of participants (intermediate and low L2 respectively) and also with respect to analyzing production versus processing data. VanPatten et al. suggest that default effects may appear in more advanced L2 speakers, but not in lower proficiency ones.

Shibuya and Wakabayashi (2008) and Wakabayashi et al. (2021) observe that L2 English (Japanese and Taiwanese L1) speakers are more sensitive to mismatches when subject plurality is marked with a demonstrative plus quantifier (*these two students speaks English) or syntactically (*Sam and Tom speaks English) than when only the head of the DP marks plurality (*the students speaks English). Additionally, they argue that L2 speakers are more sensitive to mismatches with I/you than with they, suggesting that number is problematic for these speakers. However, as VanPatten et al. (2012) note, these results may be due to the limited inflectional paradigm of English, since their own study did not find asymmetries based on person or number.

Rodríguez and Reglero (2015) replicated VanPatten et al.’s study with advanced heritage speakers, intermediate and advanced L2 speakers and native speakers, concluding that advanced heritage speakers showed slightly different reaction patterns to grammatical vs. ungrammatical items compared to native speakers: whereas native speakers showed significantly delayed reaction times in the Verb + 2 (words) region, heritage speakers showed a delayed reaction in the Verb + 3 (words) region. Heritage speakers patterned similarly to advanced L2 speakers, and both groups were different than intermediate L2 speakers. Unfortunately for our purposes, the article does not break down the results by person.

In addition to Rodríguez and Reglero’s (2015) study, which included heritage speakers in the experimental design, several studies mention S-V agreement mismatches in heritage languages, but few offer detailed accounts. For Spanish, Silva-Corvalán (2014) observed substitutions of 3rd person for 1st person forms (yo mató ‘I killed-3s’) which are more frequent in children that had less exposure to Spanish in their study. Bolonyai (2007) analyzed nominal and verbal inflection in Hungarian heritage speakers with English as dominant L2, noting that nominal, possessive inflection was more consistently dropped than verbal inflection, which was substituted for with a different form. She suggested that because verbal inflection is abstractly present in the L2, this may prevent deletion of the relevant morphology, whereas possessive inflection does not have an abstract parallel in English. Note that this is the opposite explanation to what Prévost and White (2000) and McCarthy (2006) propose for Spanish, in the sense that underspecified morphology is possible precisely in the context of verbal inflection in their analysis.

Albirini et al. (2011) analyzed the oral production of heritage varieties of Egyptian and Palestinian Arabic, observing two possibly related properties. First, word order tended to be SVO, as opposed to the canonical VSO in monolingual varieties. Relatedly, instances of VSO almost uniformly involved 3rd person singular masculine verbs regardless of the features of the subject, suggesting that these heritage speakers had difficulties mastering the morphosyntax of VSO order. Second, Egyptian HS showed slightly higher levels of S-V agreement mismatches (6.42%) than Palestinian HS (2.57%). Many of these mismatches were with plural and feminine nouns. Albirini et al. also reported a tendency to use participial forms in place of fully inflected verbal forms, although participial forms inflect for gender and number. To the extent that participial forms lack specified tense information, they could be seen as parallel to infinitival forms in Spanish.

Turning to heritage Spanish, Anderson’s (2001) longitudinal study of two children who moved from Puerto Rico to the US included instances of mismatching S-V, and noted that most of those instances involved using 3rd person singular forms for other person/numbers (va a cocinar go.3s to cook for voy a cocinar go.1s to cook ‘I am going to cook).

Goldin (2020) analyzed the development of inflection in several groups of Spanish-English bilingual children in a dual-language immersion program that included HS speakers. She found that HS speakers showed similar development to a Spanish-dominant comparison group.

With the exception of VanPatten et al. (2012) and Rodríguez and Reglero (2015), most of the studies on agreement mismatches are production-based; this is an important difference with the current study, which is based on acceptability ratings. The potential consequences of this difference are discussed in Section 4.

In sum, the L2 and heritage literature note instances of S-V agreement mismatches and instances of root infinitives, typically restricted to lower proficiency levels. Both are considered instances of default strategies, although some researchers do not find evidence for a preferred default strategy when reaction times are measured, a fact that may be attributed to the lower proficiency of the speakers. Reaction time studies have also found different patterns with respect to mismatches in S-V agreement in heritage speakers. Based on these findings, the question that arises is whether person-agreement mismatches and root infinitives are related. One natural explanation is that they both involve underspecification, but how is this relationship articulated in such a way that it covers both instances? Are these related representations mediated perhaps by proficiency?

1.2. The Source of Mismatches

As suggested in the preceding section, Prévost and White (2000) argue that root infinitives are default forms, that is, they are the result of a rule that inserts a form with a less-specified feature. A similar account has been proposed for agreement mismatches in inflected verbal forms, proposing that 3rd person is the unmarked form (McCarthy 2006). Whether these default accounts are correct or not, one can ask what drives insertion of a finite 3rd person default vs. an infinitival default. One factor we will explore in this paper is the role of a priming effect across members of the verbal paradigm. Bybee (1988, 1995) suggests that the morphological properties of words emerge from a network of connected surface forms based on the degree of similarity so that more related forms are more connected. In this context, related means sharing the number and type of semantic features and the degree of phonological similarity. More strongly connected forms will result in more interaction between them, explaining, for example, certain instances of historical change. In this paper, we explore an extension of this notion of similarity that other phonological aspects, specifically stress patterns and morphological similarity.

In this sense, form similarity may explain some of the variability observed in mismatches: since the inflectional ending for teng-o ‘I have’ is sometimes the same as the inflectional ending for 3rd person tuv-o ‘s/he had’, it is possible that the two identical inflectional endings -o will develop a stronger connection, despite their different person features, and therefore, trigger mismatches, such as yo tuvo ‘I had.3p’.2

Additionally, Bybee proposes that more frequent forms create stronger connections than less frequent ones, so we would expect to see these types of mismatches more with frequent forms than with infrequent forms. Bybee and Brewer (1980) note that 3p.sg forms are more frequent in their corpus analysis, closely followed by 1p.sg forms, particularly in the preterit. This suggests that we should expect to see more mismatches between 1p.sg and 3p.sg forms in the preterite since those are the two most frequent forms (but see below).

To illustrate the case for this surface-network model, Bybee reports results from Bybee and Slobin (1982) in which “experimentally induced errors involving vowel changes for past tense result in almost all cases not in the production of nonce forms, such as the past tense of heap as *hept, but rather in the replacement of one preexisting word for another, usually within the semantic domain (Bybee 1988, p. 125).” For example, rose was the form given for the past tense of raise, sat for the past tense of seat and sought for search. In other words, the substitutions made by these speakers build on existing connections based on phonological and semantic similarity with another existing word. Bybee also argues that the rules used in generative linguistics are really reinforced representational patterns, namely “abstractions from existing lexical forms which share one or more semantic properties (p. 135).” Importantly, connection strength depends on frequency, so that forms more frequently available in the input establish stronger connections than less frequent ones. The role of frequency in producing and/or recognizing morphemes has also been repeatedly documented in several studies, specifically for bilingual populations in Gal (1989); Giancaspro (2017, 2020); Hur (2020); Hur et al. (2020), among others.

Burzio (2004a, 2004b) formalizes a similar idea within an Optimality Theory framework, proposing the notion of connections as output-to-output faithfulness constraints (OO) that are stronger among forms that are similar (“closer” in Burzio’s terminology). The notion of output-to-output faithfulness is a consequence of the Representational Entailments Hypothesis in (5), which suggests that two forms that shift together in context X will also do so in context Y.

- (5)

- Representational Entailments Hypothesis (REH): Mental representations of linguistic expressions are sets of entailments, e.g., a representation consisting of A and B corresponds to the entailments: A ⇒ B, B ⇒ A.

Stems and morphemes are also formalized as entailments that encode information specific for individual lexical items, for example, ive ⇒ generat__. At the same time, certain entailments result from the summation of individual entailments, yielding higher order or general selection properties, for example, -ive ⇒ V. These higher order selectional entailments perform the same functions as word-formation rules in other frameworks, but like Bybee’s schemata, they emerge from the lexicon itself, so they are not independent rules in a separate grammar or morphology module, and they are violable. Frequency effects also result from a summation of entailments over the lexicon.

This notion of surface similarity suggests a possible factor in agreement mismatches. Specifically, does surface similarity interact with default forms when establishing surface-to-surface relationships? Consider the two mismatching forms in (6). The first one involves a 1st person pronoun with an infinitive verb, the second one a 1st person pronoun with a 3rd person verb. In Prévost and White’s analysis, (6)a is a case of a fully inflected T head mapped to a default form that lacks specification for finiteness. All things being equal, we would expect it to be similarly possible for subjects in all persons. By the same logic, if the finite verb in (6)b is also generated as a default (as suggested by McCarthy 2006), we would also expect it to be equally possible with subjects in all persons. Alternatively, vino ‘came.3s’ in (6)b could be the result of a surface-to-surface correspondence with 1st person forms, such as met-o ‘I introduce.1s’, but no such possibility is available for (6)a, because no other forms are like the infinitive but with person features. In other words, a pure default analysis predicts that (6)a and b should be equally possible with all persons, but surface similarity predicts an effect in (6)b but not in (6)a.

- (6)

a. Entonces yo ven-ir. then I come.inf ‘Then I came.’ b. Entonces yo vin-o. then I come-3pst ‘Then I came.’

In this paper, I will address these different predictions made by the default account vs. the OO correspondence (surface similarity) account. Specifically, the OO correspondence account predicts that only forms that are surface-similar to the target form should appear in mismatches, as formulated in (7)a, whereas the default account predicts that all person subjects should be possible with a 3rd person verb, as in (8)a. Second, the OO correspondence account predicts the opposite, since they are not surface-similar, as formulated in (7)b, whereas the default account predicts no differences between finite and non-finite 3rd person forms, since they are both defaults, as formulated in (8)b.

- (7)

- Hypothesis 1 (OO correspondence account version).a. Surface similarity affects OO correspondencei. If confirmed, S1-V3 should have higher acceptability ratings than S2-V3b. Finiteness affects OO correspondencei. If confirmed, mismatching finite and non-finite forms should be accepted at different rates.ii. If rejected, mismatching finite and non-finite forms should be accepted at comparable rates.

- (8)

- Hypothesis 1 (default account version).a. 3rd person insertion is the default rulei. All subjects should be equally acceptable with 3rd person verbs.

Regarding the question of whether surface similarity affects feature mismatches, compare the forms in (9), which vary depending on whether the stem or the affix is stressed in the preterit (the examples show syllable boundaries and stressed syllables).

- (9)

a. Stem-stressed verbs: tra.jo, tu.vo brought.3p had.3p b. Affix-stressed verbs me.tio vio inserted.3p saw.3p

This difference is important because the 3rd person preterit inflection of these verbs has the same stress pattern as the 1st person inflection of the present tense: tra.j-o ‘s/he brought’ vs. trai.g-o ‘I bring-1p’, whereas affix-stressed verbs are different: me.ti-o ’inserted-3p’ vs. me.t-o ‘insert-1p’. The affix of me.ti-o is stressed, but the affix of trai.g-o is unstressed. OO correspondence based on phonological (including prosodic) information should relate tra.j-o ‘s/he brought-1p’ to trai.g-o ‘I bring-1p’ more strongly than me.ti-o ‘insert-1p’ to me.t-o ‘insert-1p’, because of the stress difference in the latter pair. In other words, (9)a is compatible with OO correspondence (in the relevant aspects related to stress), but (9)b is not. For this reason, in order to test hypothesis (7)a, we included two stem-stressed and two affix-stressed verbs.3 Only a few verbs in Spanish are stem-stressed, and in this sense they are irregular. Tener ‘have’ shows a further root alternation: ten- in most forms vs. tuv- in the preterit and some subjunctive forms. Traer ‘bring’, on the other hand, shows three different roots: tra- (trae ‘s/he brings’) vs. traig- (traigo ‘I bring’) vs. traj- (traje ‘I brought’).

Corbett et al. (2001) point out that morphological irregularity has long been associated in the literature with high frequency, although they note that this relationship is not strictly linear. Bybee (2001, p. 12) hypothesizes that “morphological irregularity is always centered on the high-frequency items of a language”, noting that low-frequency irregular verbs like English weep/wept regularize to weeped, whereas high-frequency irregular verbs like keep/kept do not. In the context of HS, Perez-Cortes (2022) finds that heritage speakers produce target forms more accurately in irregular embedded verbs (which she assumes to be high-frequency) in the context of mood alternations.

Following this line of research, the next question we raise is whether frequency plays a role in OO correspondence. Whether one follows Bybee’s or Burzio’s formulation, frequency should favor OO correspondence, because surface forms of more frequent verbs should have stronger links (or more entailments) than those of less frequent verbs. This leads to hypothesis 2 in (10). Notice that the default account makes no specific predictions with respect to frequency.

- (10)

- Hypothesis 2.OO correspondence is mediated by frequency effects.i. If confirmed, OO correspondence should vary depending on verbfrequencies

To test for frequency effects, we selected two high-frequency and two low-frequency verbs, based on type-frequency counts from corpora (see below for details).

2. The Study

2.1. Participants

Forty-six advanced college-age (M = 19.8, SD = 1.74) heritage Spanish speakers from the Chicago area completed the task. Additionally, a group of 37 participants (age M = 34.6, SD = 9.14) who grew up in a Spanish-speaking country until at least 15 years of age but currently live in the US also completed the task as a Spanish-dominant comparison group. On average, the self-reported age of acquisition of Spanish for the heritage group was 2.35 (SD = 2.45) and 3.82 (SD = 2.14) for English. These data stems from the response to the question “at what age did you start learning the following languages?”, so may explain why the mean was 2.35. They spent an average of 19.02 years (SD = 1.61) in a Spanish-speaking family and 16.53 (SD = 5.89) in an English-speaking family. These averages may reflect changes in the composition of their family, or perhaps the introduction of English as children begin schooling in English. Their education has been primarily in English (M = 15.29 years, SD = 3.12) and to a lesser degree in Spanish (M = 4.36 years, SD = 3.76). They have spent an average of 7.97 years (SD = 8.91) in a Spanish-speaking region, which may include visits and 18.8 (SD = 1.75) in an English-speaking region.

All the Spanish-dominant participants lived at least their first 15 years of life in a Spanish-speaking country, 94% of them spent more than 20 years (M = 19.62, SD = 1.42) and an average of 9.02 years (SD = 5.66) in an English-speaking country.

Participants reported self-reported proficiency in different abilities in Spanish and English on a scale of 0–3, as seen in Table 1. Although the use of self-rating to establish proficiency is controversial, Marian et al. (2007) show that this measure accounts for the most variance in their factor analysis of the Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q). Tomoschuk et al. (2019) point out that self-rating raises issues regarding comparability across languages and differences in scales. Since this study does not establish group comparisons, the first criticism is less relevant.

Table 1.

Self-reported proficiency in English and Spanish.

In sum, the heritage participants in this study had advanced oral skills and slightly lower reading skills and lower writing skills in Spanish. Their self-reported skills in English were close to the ceiling. The Spanish-dominant group, on the other hand, had close to ceiling self-reported abilities in Spanish and high proficiency in English.

2.2. Materials

The main task was an acceptability judgment task on a scale of 1–5, which contrasts several types of Subject-Verb (S-V) agreement patterns. In addition to S3-V3 matching sentences, it included finite-verb mismatches S1-V3 (see (11)a), S2-V3 (see (11)b), and non-finite verb mismatches including S1-VINF (see (11)c), S2-VINF (see (11)d) and S3-VINF (see (11)e).

- (11)

a. Entonces yo traj-o unos documentos. (S1-V3) then I brought-3sg some documents b. Entonces tú traj-o una limonada con hielo (S2-V3) then you brought-3sg a lemonade with ice c. Por eso yo traer todos los documentos (S1-VINF) for that I bring-inf all the documents d. Entonces tú traer un flan de coco (S1-VINF) so you bring-inf a flan of coconut e. Por eso ella traer un postre a la oficina (S1-VINF) for that she bring-inf a dessert to the office

The default analysis predicts that all five mismatching items in (11) should be rated similarly, whereas the OO surface correspondence account predicts (11)a to be rated higher due to the similar stress pattern between tra.j-e ‘I brought-1p’ and tra.j-o ‘s/he brought-1p’ (and possibly also with the 1st person affix in can.t-o ‘I sing-1p’). Furthermore, OO correspondence predicts higher acceptability ratings for mismatched finite forms than for non-finite forms, on the assumption that -o may be surface-similar to other forms in the paradigm, but -er is not.

Four verbs were selected, two high frequency in monolingual corpora (ver ‘see’ and tener ‘have’) and two low frequency (traer ‘bring’, meter ‘introduce’). Traer ‘bring’ and tener ‘have’ are stem-stressed verbs and the other two (ver and meter) are affix-stressed in the 3rd person, as seen in Table 2.4

Table 2.

Experimental verbs.

Frequency calculations yield different results depending on the corpora used. Larger corpora, such as (CREA n.d.), the NOW and the Web/dialects corpora (Davies 2016) include close to 8 billion words taken together, so they represent a large sample of language data. Relative frequencies for these items, presented in Table 3, converge with Bybee and Brewer’s (1980, p. 224) observation that 1st person preterit forms are much less frequent than 3rd person preterit forms. 1st person forms are presented for illustration purposes since the experiment did not include 1st person verb forms.5 However, these corpora include oral and mostly written texts of different genres and from many regions, so it is not obvious whose language input they represent. Furthermore, these corpora may not reflect the mostly oral input that bilinguals hear in the US. For that reason, we also assessed the normalized frequencies in the Corpus del Español en el Sur de Arizona (Carvalho 2012), an oral corpus with close to 680,000 words from speakers born mostly in Arizona and Mexico. Although smaller, this corpus has the advantage of being based on oral sociolinguistic interviews from US-based speakers, and, in this sense, the frequencies in Table 4 may better reflect the input heritage speakers in the US receive. Comparison between the two tables shows interesting patterns. First, ver and tener are much more frequent than traer and meter, with the notable exception of 3p. preterit trajo ‘brought’, which has a much lower frequency in Table 4 than Table 3. The frequency of infinitives in the two tables follows similar trends: tener > ver > meter > traer. Second, the frequency of infinitival forms is systematically higher than the frequency of 3rd (and 1st) person forms, so that different by itself should favor the infinitive if frequency is an important factor.

Table 3.

Average relative frequencies by person and verb (CREA, NOW and WEB corpora).

Table 4.

Average relative frequencies by person and verb (CESA).

Fisher’s exact test determined no significant association between stress type (stem vs. affix-stressed) and frequency (High vs. Low) for 3rd person (p = 0.21). For the CREA, NOW and WEB corpora, there was a significant association for 3rd person (p = 0.02). Since stress does not shift in the infinitive, testing the association between stress placement and frequency is less relevant. We used two separate corpora frequency calculations in the statistical computation.

The task, presented online using Qualtrics®, included a total of 24 experimental sentences and 30 fillers (see Appendix A). Half of the verbs in the experimental items appeared in the infinitive form, half were presented in inflected 3rd person, all of them with a 1st, 2nd, or 3rd person singular subject, as described in Table 5. Fillers included 15 grammatical items (seven with clitics, eight without) and 15 deviant sentences (seven fully ungrammatical with clitics, eight semantically anomalous ones, see (12)). In total, 27 items were ungrammatical, 19 were fully grammatical and eight were semantically anomalous but syntactically grammatical. Because the experimental items included matching S3-V3 sentences, we thought it important to include sentences with clitics to assess grammaticality independently of the experimental items (see Montrul 2010 on the acceptability of clitics by HS). Participants first read an informed consent document, followed by a description of the task and instructions on how to react to each item. Experimental items were presented in randomized order, followed by the linguistic background questionnaire completed a linguistic background questionnaire.6

Table 5.

Experimental items.

- (12)

a. Yo no los pude encontrar. (clitic, gramatical) I not cl could find ‘I couldn’t find them.’ b. *Yo no quise los entregar (clitic, ungrammatical) I not wanted cl hand.in c. Esta mañana mi hermano salió de su casa. Pero él no salió de this morning my brother left of his house. But he not left of su casa (semantically contradictory) his house ‘This morning, my brother left his house, but he didn’t leave his house.’

3. Results

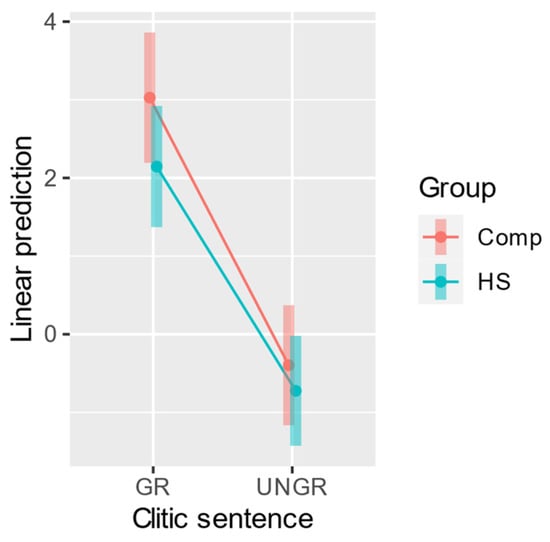

In order to establish a baseline for grammaticality, we first compared the ratings of fillers with grammatical and ungrammatical clitics. The average rating for grammatical clitic sentences was 4.41 for both groups (4.30 for the HS group) and 2.58 for ungrammatical sentences with clitics (2.55 for the HS group) on a scale of 1–5. An ordinal logistic regression in R (R Core Team 2021) using the ordinal package (Christensen 2019), with ratings as the output and item (grammatical or ungrammatical clitic sentence), group and item by group interaction as predictors, resulted in a significant main effect of item (Item(Grammatical) β0 = 3.43, SE = 0.51, p < 0.0001) but not for group (Group(HS) β0 = −0.33, SE = 0.33, p = 0.32) and the interaction between item and group (Item(Ungrammatical) × Group (HS) β0 = 0.55, SE = 0.29, p = 0.05). Grammatical clitic items were 30 times more likely to be rated highly compared to ungrammatical clitic items, more of the effect coming from the rating of grammatical items, as the interaction in Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1.

Group by item interaction.

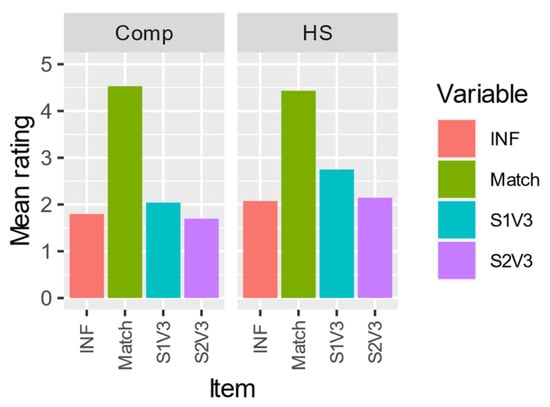

Looking at the experimental items, Figure 2 presents the mean acceptability ratings for different conditions by group.7 As expected, agreement-matching sentences were ranked highest, followed by S1-V3 mismatching sentences, S2-V3 mismatching sentences and infinitival sentences. HS speakers rated mismatching sentences higher than the comparison group, suggesting higher tolerance for mismatches.

Figure 2.

Mean ratings for infinitival, matching and mismatching forms by group.

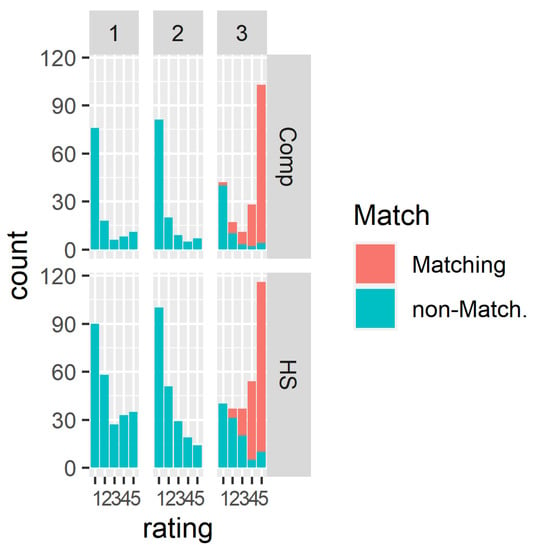

Figure 3 shows the acceptability ratings by person and agreement matching. In this figure, we can see that the lowest ratings correspond to agreement-mismatching items (in blue), and the highest ratings to agreement-matching (in red). Participants gave more 4–5 ratings to 1st person than to 2nd person and 3rd person, mismatching subjects.

Figure 3.

Response counts per person (matching vs. non-matching items).

In order to confirm that participants made a clear distinction between matching and non-matching items, we ran a mixed-effects ordinal logistic regression in R (R Core Team 2021) using the ordinal package (Christensen 2019), including rating (an ordered ordinal variable) as output variable and Match (Matching, non-Matching) as independent variable and Participant and Verb as random effects. As expected, matching items were significantly more likely to be rated highly than mismatching items (Match(Matching) β0 = 4.65, SE = 0.32, p < 0.0001), specifically 105 times higher odds.

Because of multicollinearity effects, Match could not be included in the model with the other variables, so a second model with rating (an ordered ordinal variable) as output variable and Person (1, 2, 3), Form (Finite, non-finite), Person X Form and ProficiencyOral (average of self-rated speaking and listening proficiency in Spanish) as fixed effects and random intercepts for participant and verb.8

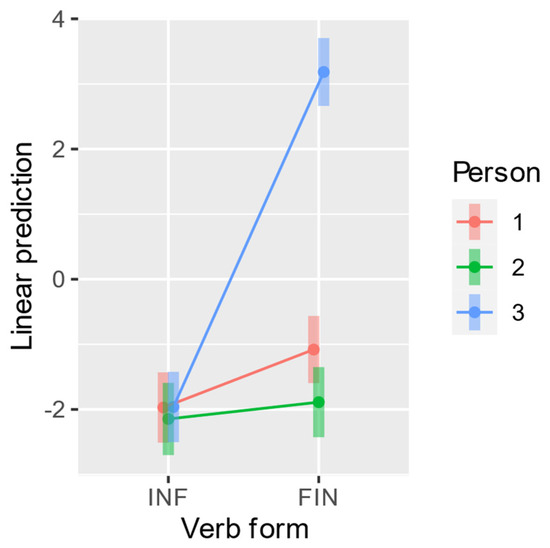

Results in Table 6 show that Form and Proficiency were significant predictors. Specifically, finite forms were 2.4 times more likely to receive a higher rating than non-finite forms, and higher proficiency lowered the odds of higher ratings. More importantly, Person significantly interacted with finite Form. Form-Person interactions are illustrated in Figure 4 (person refers to subjects): 3rd person subjects had a significantly higher effect on rating for finite forms than for non-finite, as expected since finite forms include matching, but 1st person also had a significantly higher effect on finite forms than on non-finite verbs. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons for verb form and person found that only finite forms had significant contrasts between 1st and 2nd person subjects (Bonferroni adjusted p = 0.0007), as well as 1st and 3rd and 2nd and 3rd (p < 0.0001) although the latter two are not relevant for our purpose, since 3rd person subjects include matching S3-V3 and non-matching S3-Vinf items. Non-finite forms, on the other hand, had no significant contrasts between persons.

Table 6.

Model parameters (Person, Form, Frequency, V-type and Proficiency).

Figure 4.

Pairwise contrasts between Form and person.

The contrast between 1st and 2nd person subjects confirms the first hypothesis in (7)a and disproves the alternative default account hypothesis in (8)a, since S1-V3 and S2-V3 had significantly different acceptability ratings, with 1st persons having a greater probability of higher ratings than 2nd persons.

In order to test hypothesis (7)b, which predicts differences between finite and non-finite mismatching conditions, and the default account hypothesis in and (8)b, which predicts the opposite, we ran a model with the mismatching conditions only (S1-V3, S2-V3 and S1, S3, S3-Vinf). This model included acceptability rating as an ordered outcome variable and verb Form (finite or non-finite), V-type (affix or stem-stressed) and oral proficiency as independent variables, with participant and verb as random factors. As the model parameters in Table 7 show, all three variables were significant. Finite verbs were 94% more likely to get a higher acceptability rating than non-finite verbs, and stem-stressed verbs were 66% more likely to be highly rated than affix-stressed verbs. Oral proficiency increases reduced the likelihood of higher ratings by 96%. Considering that all the items in this model were non-matching, this effect of higher proficiency is expected: with higher proficiency, speakers will more confidently reject mismatching items and rate them less acceptable. The fact that acceptability ratings for finite verb forms significantly differed from non-finite verbs refutes (8)b and confirms hypothesis (7)b, which predicted that finite nonmatching forms should be rated higher than non-finite forms if surface similarity plays a role.

Table 7.

Model parameters for non-matching items (Form, V-type and Proficiency).

The fact that frequency did not have an effect does not support the hypothesis in (10)9.

In sum, S1-V3 had significantly greater odds of acceptable ratings than S2-V3 and, among mismatching items, finite forms had greater odds of acceptable ratings than non-finite forms.

4. Discussion

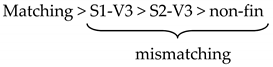

The results presented in the previous section indicate that bilingual speakers (proficient HS speakers and Spanish-dominant comparison speakers) show a preference for the scale in (13), with a clear break between matching and mismatching, but also between each of the mismatching categories.

- (13)

The participants in this study had a smaller range of self-reported proficiency than those in previous studies and proficiency was measured as a continuous variable. Nevertheless, these results are consistent with Liceras et al.’s (1999) observation that root infinitives diminish in production when proficiency increases.

4.1. Person Asymmetries and OO Correspondence (Surface-Similarity)

The first hypothesis in (7)a predicted that OO correspondence should be sensitive to person, assuming that the phonological and prosodic shape of the surface form affects OO correspondence. This hypothesis was confirmed since S1-V3 mismatches were rated systematically higher than S2-V3 mismatches. The OO correspondence hypothesis establishes a link (or an entailment in Burzio’s terms) between the unstressed 3rd person affix of tra.j-o ‘brought.3p.past’ and unstressed 1st person affix of trai.g-o ‘bring.1p.pres’, but not between stressed 3rd person affix of me.ti-o ‘introduced.3p.past’ and the stressed 1st person affix of me.t-o ‘introduce.1p.pres‘, so we expected a higher rating for the former than for the latter. Furthermore, the fact that stem-stressed verbs showed higher ratings than affix-stressed ones confirms the proposed analysis since the former would find more surface correspondences within the paradigm (tra.j-o ‘brought.3p.past’, tra.j-e ‘brought.1p.past’ and trai.g-o ‘bring.1p.pres’) than the latter.

It is possible that nominals may have a different feature structure depending on the person, as Béjar (2003); Béjar and Rezac (2009); Harley and Ritter (2002a, 2002b); Nevins (2007) among others, have suggested. In general, these analyses provide a mechanism to distinguish 3rd persons from all others, capturing the observation that 3rd persons are default. However, as we have seen, the results of these studies do not support the idea that 3rd persons are more favored than 1st or 2nd persons. Nevins (2007) proposes an account that maintains the role of 3rd person as default without treating as unmarked, however, the specific combination of features and the relativized agreement he uses predicts that if there is an asymmetry between 1st and 2nd person, S2-V3 should be preferred to S1-V3, contrary to what we observe. Specifically, Nevins (2007)’ agreement features appear in (14).

- (14)

- a. 1st person: [+Author], [+Participant]b. 2nd person: [-Author], [+Participant]c. 3rd person: [-Author], [-Participant]

Agreement is formalized as a feature-matching relationship between a probe, T in our case, and a goal (DP). An agreement can match full feature sets or feature subsets that have features with contrastive values or marked values. Given the way contrastivity and markedness are defined in his system, relativized agreement between a 3rd person probe and, a goal would target either a 3rd person or a 2nd person, predicting possible S2-V3 and, S3-V3 agreement mismatches. However, as we have seen, S1-V3 has better acceptability odds than S2-V3.10

4.2. The Place of OO Correspondence

Returning to the role of surface similarity, it is clear that all speakers were aware that non-matching forms were deviant compared to matching S-V forms, even if they rated yo tra.j-o ‘I brought.3p.past’ higher than yo me.ti-o ‘introduced.3p.past’. Presumably, when speakers read the mismatching forms, processing S-V agreement failed because of the feature clash between the subject and inflection, but the surface form tra.j-o would trigger an OO correspondence with trai.g-o ‘bring.1p.pres’ that would mitigate the failed agreement, whereas me.ti-o would not trigger such correspondence with me.t-o ‘introduce.1p.pres‘ because the stress patterns are different. This would account for the higher acceptability rating for S1-V3 in the stem-stressed forms.11

From a different point of view, this paper raises an intriguing question: why should speakers show these gray areas between grammaticality and ungrammaticality? Under the canonical generative view of grammar, grammaticality, and its close correlate, acceptability is viewed as categorical, perhaps mediated by processing effects, but not as a gradable concept, although in practice grammaticality judgments have always had degrees. However, the phenomena under analysis in this paper seem to exploit productive grammatical mechanisms that operate on “unacceptable” structures. In this view, we are suggesting, speakers process mismatches as mismatches, but are able to formally repair them using surface similarity networks. The implications for bilingual grammars are important, since these gray-area mechanisms may be a path for divergence between bilingual and monolingual grammars.

4.3. Morphological Mechanisms. The Role of Frequency

The second hypothesis in (7)b, which predicted that finite forms should receive higher acceptability ratings than non-finite ones, given the potential surface similarity of the former was also confirmed. Specifically, ratings for non-finite forms were systematically lower than for finite mismatched ones. This result is not predicted by the default account. In the current account, tener ‘have.inf’ differs enough from inflected forms that form similarity correspondences would be weak and would not alleviate a failed feature agreement.12

It is important to note that the OO correspondence analysis does not preclude the existence of defaults. Indeed, several researchers have argued that 3rd person is less marked than 1st and 2nd persons (see Jakobson 1963; Benveniste 1966; Harley and Ritter 2002a, 2002b; Bianchi 2006; Nevins 2007; Piñeros 2017), so it is quite possible that surface similarity may interact with paradigm defaults. The design of this study was not intended to test for default effects, since all finite forms were 3rd person, but our results suggest that surface similarity ameliorates mismatches with default 3rd person verbal forms compared to dissimilar infinitival forms.

What is less clear from this study is the connection between morphological processes or representations and frequency. Traditional generative accounts do not generally postulate an explicit role for frequency in morphological processes However, notions, such as markedness or default implicitly capture how a form undergoes a certain process. Burzio’s account explicitly incorporates these notions to his model, as does Bybee. In this sense, the previous literature has observed that frequent irregular forms are more resilient (see Bybee 2001, for example), a finding indirectly replicated in the HS literature in Perez-Cortes (2022), who found that irregular embedded verbs were more target-like than regular ones in contexts where mood is alternated.

Our results only partially confirmed this view: on the one hand, irregular, stem-stressed verbs were more acceptable particularly with nonmatching items. If irregular verbs have stronger networks or entailments than regular ones, one would expect speakers to activate surface similarity connections more readily. On the other hand, this preference extended to both high and low-frequency stem-stressed verbs, suggesting that frequency did not modulate irregular morphology.

If confirmed, these results suggest the need to develop a more comprehensive notion of how lexical networks are interrelated and how frequency affects them. As noted in our discussion of the different corpora, different forms in the paradigm had very different frequencies, so a high frequency for a 1st person preterit may be comparatively low compared to the infinitive, and if the OO correspondence view is right, one would expect the frequency to affect not only word-to-word networks, but affix-to-stem, affix-to-affix, paradigmatic form-to-paradigmatic form, etc., and to affect them possibly differently.

4.4. On the Bilingualism Continuum

One of the research questions that motivated this study was whether these mismatching agreement effects were related to bilingualism. However, the absence of group effects suggests this is not the case. It is likely that this is due to the similar proficiency level between the HS group and the Spanish-dominant group, but it is also interesting to note that oral proficiency, imperfect as it may be as a self-reported continuous variable, did have a strong effect. This contrast between the absence of group effects and strong proficiency effects suggests that the categorical distinction between heritage and minority-dominant speakers is less relevant than the proficiency continuum. Although previous studies have found nonmatching S-V agreement patterns among HS speakers, these are mostly among lower proficiency speakers and the studies do not include proficiency as a continuous variable.

From a different perspective, this study shows an area in which HS speakers have patterns similar to Spanish-dominant counterparts, even though sensitivity to OO correspondence could be argued to be a peripheral and subtle aspect of linguistic ability. In other words, most studies of HS focus on how those speakers are different from either minority-dominant speakers or monolinguals. This study shows an area in which they seem to be very similar. It is possible that the similarity in acceptability ratings among HS and Spanish-dominant speakers may be due to the absence of cross-linguistic effects from English, since English verbs have limited morphology, and arguably the 3rd person form is not the default morphological form (see Nevins 2007, p. 283).

5. Conclusions

This study opens several areas for future research. First, testing whether the effects we have found are also present in lower proficiencies in the continuum. Second, the current design compared stem-stressed vs. affix-stressed forms, an interesting extension would be to include the actual suspected target for the output correspondence, comparing, for example, yo me.tió ‘I introduced.3p.past’ vs. ella me-te ‘she introduces.3p.pres’ and yo tra.j-o ‘I brought.3p.past’ vs. ella trai.g-o ‘she bring.1p.pres’. These combinations would allow us to confirm whether actual similar forms are subject to output-to-out correspondence.

To conclude, the results presented in this study have found some evidence for the role of OO correspondence, or surface similarity in morphological form acceptability in the context of agreement mismatches. It also stresses the importance of treating proficiency as a continuous variable, perhaps as a more important variable than categorical group distinctions. Finally, it raises the need to find a more nuanced operationalization of frequency in the studies where the role of lexical frequency may be suspected.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Illinois, Chicago (protocol # 2020-0228 “Grammatical properties of Spanish”, approved 24 March 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Following the approved protocol, data cannot be made public.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for the time devoted to commenting this paper, and for the excellent suggestions they made. The paper has also greatly benefitted from discussions with David Giancaspro about agreement mismatches. He initially mentioned the use of 3rd person verbal forms with 1st person subjects among heritage speakers.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Experimental items

| Context | Experimental item | |

| S1-V3 (mismatched finite, ungrammatical in monolingual Spanish) sentences | ||

| S1-V3 | Ayer me pidieron varios documentos en la oficina. | Así que yo trajo todos los papeles |

| S1-V3 | Esta mañana, mi hermano salió de la casa. | Yo vio su moto en la calle |

| S1-V3 | Cuando tenía 5 años trajeron un perro. | Yo tuvo ese animal muchos años |

| S1-V3 | Esta mañana se me cayó la llave. | Por eso yo metió la mano en el hueco |

| S2-V3 (mismatched finite, ungrammatical in monolingual Spanish) sentences | ||

| S2-V3 | En el restaurante te pedí una bebida. | Entonces tú trajo una limonada con hielo |

| S2-V3 | Esa serie de Netflix fue muy famosa. | Tú vio toda la temporada |

| S2-V3 | Primero, compraste un carro rojo. | Después tú tuvo un Honda azul |

| S2-V3 | Ese día, empezó a llover mucho. | Entonces tú metió los muebles en tu casa |

| S3-V3 (matched finite, grammatical) sentences | ||

| S3-V3 | En esa época Juana tuvo una pastelería. | Por eso ella trajo muchos pasteles |

| S3-V3 | Ayer jugaron la final de tenis. | Ella vio el partido en la televisión |

| S3-V3 | Miguel perdió a sus padres muy joven. | Él tuvo muchos problemas después |

| S3-V3 | Santiago buscaba nuevos amigos. | Él metió su información en Instagram |

| S1-V3 (mismatched non-finite, ungrammatical) sentences | ||

| S1-V3 | Hoy me pidieron unos papeles en el registro. | Por eso yo traer todos los documentos |

| S1-V3 | Mi papá salió de la casa. | Yo ver la puerta de la casa cerrada. |

| S1-V3 | Cuando tenía 20 años compré una moto. | Yo tener esa moto 10 años |

| S1-V3 | Ayer compré un regalo para Lara. | Después yo meter el regalo en el cajón |

| S2-V3 (mismatched non-finite, ungrammatical) sentences | ||

| S2-V3 | En la cafetería te pedí un postre. | Entonces tú traer un flan de coco |

| S2-V3 | Esa película de Hulu fue muy mala. | Tú ver solo la primera mitad |

| S2-V3 | Yo me acuerdo de tus botas amarillas. | Después tú tener unos zapatos rojos |

| S2-V3 | El otro día, empezó a hacer mucho calor. | Entonces tú meter a los niños en la casa |

| S3-V3 (mismatched non-finite, ungrammatical) sentences | ||

| S3-V3 | En esa época Juana hacía tortas. | Por eso ella traer un postre a la oficina |

| S3-V3 | Ana olvidó el partido de futbol ayer. | Ella ver tenis en la televisión |

| S3-V3 | Miguel perdió su celular hace un mes. | Él tener muchos problemas después |

| S3-V3 | Este año, Ruth recibió un aumento. | Ella meter el dinero en el banco |

| Grammatical filler sentences | ||

| Clitic | Ayer me pidieron varios documentos en la oficina. | Yo no los pude encontrar |

| Clitic | En esa época Juana tenía una pastelería. | Ella quería venderla |

| Clitic | En la cafetería te pedí un postre. | Tú no lo quisiste comer |

| Clitic | En la universidad, Ruth descubrió el Karate. | En poco tiempo lo pudo aprender |

| Clitic | Cuando tenía 5 años trajeron un perro. | Yo lo adopté inmediatamente |

| Clitic | Yo me acuerdo de tu carro rojo. | Tú no lo tuviste mucho tiempo |

| Clitic | Ese día, empezó a llover mucho. | Yo me mojé completamente |

| Esa serie de Netflix fue muy famosa. | Lamentablemente yo no la pude ver | |

| Mi papá salió de la casa. | Mi hermano se quedó | |

| Cuando tenía 20 años compré una moto. | Después yo compré un carro rojo | |

| Yo me acuerdo de tus botas amarillas. | Tú tenías unos pantalones verdes también | |

| Miguel perdió su celular hace un mes. | Él compró uno nuevo después | |

| Ana estaba en la universidad. | Ahí ella estudió español | |

| Gabriel llegó un día a su casa. | Cuando entró, él encontró una araña | |

| Lani subió las escaleras. | Arriba ella sintió frío | |

| Grammatical but semantically anomalous sentences | ||

| Esta mañana, mi hermano salió de la casa. | Pero él no salió de la casa | |

| Ana olvidó el partido de futbol ayer. | Pero recordó el partido | |

| El huracán destruyó la casa de Marta. | Ella vive en su casa | |

| El día estaba muy caliente. | Carla tenía mucho frío | |

| El gato se cayó de la ventana. | Tenía buen equilibrio | |

| Miguel perdió a sus padres muy joven. | Ellos vivieron muchos años | |

| En el restaurante te pedí una bebida. | Pero yo no te pude pedir la bebida | |

| Santiago aprendió rápido sobre tecnología. | Él no sabe sobre tecnología | |

| Ungrammatical fillers | ||

| Clitic | Esta mañana se me cayó la llave. | Yo no pude la encontrar |

| Clitic | En esa época Juana hacía tortas. | Ella no podía las vender |

| Clitic | Hoy me pidieron unos papeles en el registro. | Yo no quise los entregar |

| Clitic | Ayer compré un regalo para Lara. | Después yo no pude selo dar |

| Clitic | El otro día, empezó a hacer mucho calor. | Por eso tú seguiste te quejando mucho |

| Clitic | Ayer jugaban la final de tenis. | Tú pudiste la ver en tu casa |

| Clitic | Esa película de Hulu fue muy mala. | Por eso tú no quisiste la ver |

Notes

| 1 | The conditions for root infinitives in adult monolingual grammars are very different than what we find in bilinguals. Most notably, monolingual root infinitives generally lack assertive force, for example, and they tend to be questions or exclamatives, as in (i), where the assertive force is not in the clause that contains the infinitive, but in the so-called coda (qué maravilla ‘how wonderful’). See Lambrecht (1990) and especially Grohmann and Etxepare (2003, 2005) for a full analysis of their properties, and Hernanz (1999) for a general description of patterns in Spanish.

|

| 2 | See Aronoff (2013) and Ackema and Neeleman (2019) for a discussion of different conceptions of “default”, as well as Kiparski (1973) and subsequent references for the notion of “Elsewhere Principle” that underlies Prévost and White’s (2000) Distributed Morphology account. Tsimpli and Hulk (2013) argue for the need to distinguish between linguistic default and learner default, from the point of view of acquisition. |

| 3 | As an anonymous reviewer points out, extending similarity to morphological and prosodic domains raises the question of how these different dimensions of similarity interact. So, for example, tuv-o ‘have.3.sg.pret’ is phonologically closer to tuv-e ‘have-1.sg.pret’ than teng-o ‘have-1.sg.pres’ is to tuv-e ‘have-1.sg.pret’, if one looks at the overall similarity at the world-level. In general, I agree that the most important aspect related to surface similarity has to be segmental, with two caveats: first, form-similarity can be restricted to certain domains (for example suffixes), and second, stress placement can also induce effects. Working out the full set of interactions that drive similarity is complex and goes beyond the scope of this paper. |

| 4 | Kim (2020) notes that Spanish heritage speakers differ from monolinguals in the acoustic correlates of stress, both in production and perception. Although differences emerged, these were mostly related to production, whereas heritage speakers were more similar to monolinguals when perceiving lexical stress. |

| 5 | Anonymous reviewers note the limitation of having only 4 verbs, each representing a combination of frequency and stress patterns. Notice, however, that both Bybee and Burzio’s accounts are based on individual lexical items that may or may not build up to schemata or higher order selection entailments depending on frequency. In this sense, while having more lexical items would allow us to possibly extend claims to higher order schemata, results from individual items are valid in themselves within the assumptions of these frameworks. |

| 6 | Austin (2013) also observes that bilingual Spanish-Basque children produce 3rd person more frequently than 1st person, as do the adults that surround them. |

| 7 | An anonymous reviewer notes that an overwhelming number of experimental items would be considered ungrammatical in monolingual Spanish. Since we are comparing different types of mismatches (by person and by finiteness) and not establishing the absolute grammaticality of a given construction, having 50% of “grammatical” (or matching) sentences in the task does not seem to be crucial. |

| 8 | Notice that the number of infinitival sentences is much larger than the other categories, because it includes all three persons. |

| 9 | Group (HS vs. comparison) and Frequency (in the CESA corpus) were also included in alternative models, but they were not statistically significant, and the model comparison with those variables did not improve the fit, so they were dropped. |

| 10 | Running the model with a normalized token frequency from the larger CREA, web and now corpora did not change results: frequency has a very small effect and it is not statistically significant. |

| 11 | I wish to thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting the potential relevance of Nevins’ framework as an alternative explanation for the current data. |

| 12 | An anonymous reviewer raises the question of whether defaults or surface similarity should arise in comprehension (as opposed to production), and notes that most studies of agreement mismatches have included production data. I assume that defaults and surface similarity can also apply in comprehension, and the fact that we find significantly different ratings depending on person is consistent with the notion that speakers can process non-target input and assign it a grammatical representation that fits it best. Given those differences, surface similarity can be seen as one of the mechanisms that bridges the gap between the target representation and input. |

References

- Albirini, Abdulkafi, Elabbas Benmamoun, and Eman Saadah. 2011. Grammatical Features of Egyptian and Palestinian Arabic Heritage Speakers’ Oral Production. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 33: 273–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackema, Peter, and Ad Neeleman. 2019. Default person versus default number in agreement. In Agreement, Case and Locality in the Nominal and Verbal Domains. Edited by Ludovico Franco, Mihaela Marchis Moreno and Mathew Reeve. Berlin: Language Science Press, p. 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Raquel. 2001. Lexical morphology and verb use in child first language loss: A preliminary case study investigation. International Journal of Bilingualism 5: 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronoff, Mark. 2013. Varieties of morphological defaults and exceptions. Revista Virtual de Estudos da Linguagem-REVEL 11: 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, Jennifer. 2013. Markedness, input frequency, and the acquisition of inflection: Evidence from Basque/Spanish bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingualism 17: 259–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béjar, Susana. 2003. Phi-Syntax: A Theory of Agreement. Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Béjar, Susana, and Milan Rezac. 2009. Cyclic Agree. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 35–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul, and Maria Polinsky. 2010. Prolegomena to Heritage Linguistics. Available online: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:23519841 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul, and Maria Polinsky. 2013. Heritage languages and their speakers: Opportunities and challenges for linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics 39: 129–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benveniste, Émile. 1966. Problèmes de linguistique générale. Paris: Bibliothéque des Sciences Humaines. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Valentina. 2006. On the syntax of personal arguments. Lingua 116: 2023–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolonyai, Agnes. 2007. (In)vulnerable agreement in incomplete bilingual L1 learners. The International Journal of Bilingualism 11: 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burzio, Luigi. 2004a. Paradigmatic and Syntagmatic Relations in Italian Verbal Inflection. In Contemporary Approaches to Romance Linguistics: Selected Papers from the 33rd Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL). Edited by Julie Auger, J. Clancy Clements and Barbara Vance. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzio, Luigi. 2004b. Sources of Paradigm Uniformity. In Paradigms in Phonological Theory. Edited by Laura J. Downing, Alan Hall and Renate Raffelsiefen. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan L. 1988. Morphology as lexical organization. In Theoretical Morphology. Edited by Michael Hammond and Michael Noonan. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 119–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan L. 1995. Regular morphology and the lexicon. Language Cognitive Processes 10: 425–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan L. 2001. Phonology and Language Use. Phonology and Language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan L., and Dan I. Slobin. 1982. Rules and Schemas in the Development and Use of the English past Tense. Language 58: 265–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan L., and Mary Alexandra Brewer. 1980. Explanation in morphophonemics: Changes in provençal and Spanish preterite forms. Lingua 52: 201–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, José. n.d. Infinitivos matriz en un hispanohablante de herencia. To appear in volume edited by Miguel Rodríguez-Mondoñedo and Liliana Sánchez. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

- Carvalho, Ana M. 2012. Corpus del Español en el Sur de Arizona (CESA). Tucson: University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Rune Haubo Bojesen. 2019. Ordinal—Regression Models for Ordinal Data. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ordinal (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Corbett, Greville, Andrew Hippisley, Dunstan Brown, and Paul Marriott. 2001. Frequency and the emergence of linguistic structure. In Frequency and the Emergence of Linguistic Structure. Edited by Joan L. Bybee and Paul J. Hopper. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 201–26. [Google Scholar]

- CREA. n.d. Real Academia Española: Banco de Datos. Corpus de Referencia del Español Actual. Available online: http://www.rae.es (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Davies, Mark. 2016. Corpus del Español: Two Billion Words, 21 Countries. Available online: http://www.corpusdelespanol.org (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Ezeizabarrena, Maria-José. 2002. Root Infinitives in Two Pro-Drop Languages. In The Acquisition of Spanish Morphosyntax. Studies in Theoretical Psycholinguistics. Edited by Pérez-Leroux Ana Teresa and Juana Liceras. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 35–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeizabarrena, Maria-José. 2003. Null Subjects and optional infinitives in Basque. In (In)vulnerable Domains in Multilingualism. Edited by Natascha Müller. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, Susan. 1989. Lexical innovation and loss: The use and value of restricted Hungarian. In Investigating Obsolescence. Edited by Nancy C. Dorian. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 313–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancaspro, David. 2017. Heritage speakers’ production and comprehension of lexically- and contextually-selected mood in Spanish. Ph.D. thesis, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Giancaspro, David. 2020. Not in the Mood: Frequency Effects in Heritage Speakers’ Subjunctive Knowledge. In Lost in Transmission: The Role of Attrition and Input in Heritage Language Development. Edited by Bernhard Brehmer and Jeanine Treffers-Daller. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 72–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, Michele. 2020. Syntax before morphology? The Role of Age and Context of Acquisition in the Development of Subject-Verb Agreement in Bilingual Children. Ph.D. thesis, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstead, John. 1994. The Emergence of Nominative Case Assignment in Child Catalan and Spanish. Master’s thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann, Kleanthes, and Ricardo Etxepare. 2003. Root Infinitives: A Comparative View. Probus 15: 201–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, Kleanthes, and Ricardo Etxepare. 2005. Towards a Grammar of Adult Root Infinitives. In Proceedings of the 24th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Edited by John Alderete, Han Chung-hye and Alexei Kochetov. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 129–37. [Google Scholar]

- Guasti, Maria-Teresa. 1994. Verb syntax in italian child grammar: Finite and nonfinite verbs. Language Acquisition 3: 1–40. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20011388 (accessed on 15 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Haegeman, Liliane. 1995. Root infinitives, tense, and truncated structures in Dutch. Language Acquisition 4: 205–55. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20011422 (accessed on 15 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Harley, Heidi, and Elizabeth Ritter. 2002a. Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language 78: 482–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, Heidi, and Elizabeth Ritter. 2002b. Structuring the bundle: A universal morphosyntactic feature geometry. In Pronouns–Features and Representation. Edited by Horst Simon and Heike Weise. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernanz, María Luisa. 1999. El infitivo. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, pp. 2202–355. [Google Scholar]

- Herschensohn, Julia. 2001. Missing inflection in second language French: Accidental infinitives and other verbal deficits. Second Language Research 17: 273–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, Teun, and Nina Hyams. 1998. Aspects of root infinitives. Lingua 106: 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Esther. 2020. Verbal lexical frequency and DOM in heritage speakers of Spanish. In The Acquisition of Differential Object Marking. Edited by Alexandru Mardale and Silvina Montrul. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 207–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Esther, Julio Lopez-Otero, and Liliana Sánchez. 2020. Gender Agreement and Assignment in Spanish Heritage Speakers: Does Frequency Matter? Languages 5: 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyams, Nina. 2005. Child non-finite clauses and the mood-aspect connection. Evidence from Greek. In Aspectual Inquiries. Edited by Paula Kempchinsky and Roumiana Slabakova. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobson, Roman. 1963. Implications of language universals for linguistics. In Universals of Language. Edited by Joseph Greenberg. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 263–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, Knud. 1990. “What, me worry?”--‘Mad Magazine Sentences’ Revisited. Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 16: 215–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Ji Young. 2020. Discrepancy between heritage speakers’ use of suprasegmental cues in the perception and production of Spanish lexical stress. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23: 233–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiparski, Paul. 1973. ‘Elsewhere’ in phonology. In A Festschrift for Morris Halle. Edited by Steven Anderson and Paul Kiparsky. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Lasser, Ingeborg. 1997. Finiteness in Adult and Child German. Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, Juana M., Aurora Bel, and Susana Perales. 2006. Living with optionality: Root infinitives, bare forms and inflected forms in child null subject languages. In Selected Proceedings of the 9th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Nuria Sagarra and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 203–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, Juana M., Elena Valenzuela, and Lourdes Díaz. 1999. L1/L2 Spanish Grammars and the Pragmatic Deficit Hypothesis. Second Language Research 15: 161–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, Viorica, Henrike K. Blumenfeld, and Margarita Kaushanskaya. 2007. The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing Language Profiles in Bilinguals and Multilinguals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 50: 940–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCarthy, Corrine. 2006. Default Morphology in Second Language Spanish. In New Perspectives on Romance Linguistics: Morphology, Syntax, Semantics and Pragmatics. Edited by Jean-Pierre Montreuil and Chiyo Nichida. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, pp. 201–12. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2010. How similar are adult second language learners and Spanish heritage speakers? Spanish clitics and word order. Applied Psycholinguistics 31: 167–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, Rakesh M. Bhatt, and Archna Bhatia. 2012. Erosion of case and agreement in Hindi heritage speakers. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 2: 141–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevins, Andrew. 2007. The representation of third person and its consequences for person-case effects. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25: 273–313. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cortes, Silvia. 2022. Lexical frequency and morphological regularity as sources of heritage speaker variability in the acquisition of mood. Second language Research 38: 149–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Collin. 1996. Root Infinitives are Finite. In Proceedings of BUCLD 20. Edited by Andy Stringfellow, Dalia Cahana-Amitay, Hughes Elizabeth and Andrea Zukowski. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 588–600. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, Amy. 1989. On the Emergence of Syntax: A Cross-Linguistic Study. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Piñeros, Carlos-Eduardo. 2017. Person and number markers in Spanish verb forms. Lingua 195: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévost, Philippe, and Lydia White. 2000. Missing Surface Inflection or Impairment in second language acquisition? Evidence from tense and agreement. Second Language Research 16: 103–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1994. Early null subjects and root null subjects. In Language Acquisition Studies in Generative Grammar. Edited by Teun Hoekstra and Bonnie Schwartz. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 151–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Estrella, and Lara Reglero. 2015. Heritage and L2 processing of person and number features: Evidence from Spanish subject-verb agreement. Euro American Journal of Applied Linguistics and Languages 2: 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez, Rosaura. 1983. Chicano Discourse: Socio-Historic Perspectives. Houston: Arte Público Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya, Mayumi, and Shigenori Wakabayashi. 2008. Why are L2 learners not always sensitive to subject-verb agreement? Eurosla Yearbook 8: 235–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 2014. Bilingual Language Acquisition: Spanish and English in the First Six Years. Cambride: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tomoschuk, Brendan, Victor Ferreira, and Tamar Gollan. 2019. When a seven is not a seven: Self-ratings of bilingual language proficiency differ between and within language populations. Bilingualism 22: 516–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsimpli, Ianthi Maria, and Aafke Hulk. 2013. Grammatical gender and the notion of default: Insights from language acquisition. Lingua 137: 128–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, Bill, Gregory D. Keating, and Michael J. Leeser. 2012. Missing verbal inflections as a representational problem: Evidence from self-paced reading. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 2: 109–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, Shigenori, Takayuki Kimura, John Matthews, Takayuki Akimoto, Tomohiro Hokari, Tae Yamazaki, and Koichi Otaki. 2021. Asymmetry between Person and Number Features in L2 Subject-Verb Agreement. In Proceedings of the 45th annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Danielle Dionne and Lee-Ann Vidal Covas. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 735–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler, Kenneth. 1994. Optional infinitives, head movement and the economy of derivations. In Verb Movement. Edited by David Lightfoot and Norbert Hornstein. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 305–50. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).