Abstract

Children acquire language more easily than adults, though it is controversial whether this faculty declines as a result of a critical period or something else. To address this question, we investigate the role of age of acquisition and proficiency on morphosyntactic processing in adult monolinguals and bilinguals. Spanish monolinguals and intermediate and advanced early and late bilinguals of Spanish read sentences with adjacent subject–verb number agreements and violations and chose one of four pictures. Eye-tracking data revealed that all groups were sensitive to the violations and attended more to more salient plural and preterit verbs than less obvious singular and present verbs, regardless of AoA and proficiency level. We conclude that the processing of adjacent SV agreement depends on perceptual salience and language use, rather than AoA or proficiency. These findings support usage-based theories of language acquisition.

1. Introduction

Research investigating the existence of a critical period for language acquisition is prolific but controversial (see DeLuca et al. 2019 for a review). Many studies investigating the role of age of acquisition (AoA) have focused on morphosyntactic phenomena because adult L2 learners have pervasive difficulties processing agreement relationships absent in their L1. However, these studies have a number of limitations. First, studies comparing early bilinguals with late bilinguals are mostly restricted to one proficiency level or subjective proficiency measures. Second, studies examining a grammatical structure acquired late take the risk of producing floor effects. Third, offline studies may not faithfully represent real-time L2 processing, and online studies with non-cumulative displays, typical of self-paced reading and event-related potentials (ERPs), may increase cognitive task demands. Finally, studies including explicit tasks such as grammaticality judgments may not assess unconscious processes. To disentangle the effects of AoA and proficiency on bilingual morphosyntactic processing, we included bilinguals varying in age of onset and proficiency, a simple implicit task (a reading eye-tracking task with semantic judgments), and a simple grammatical structure known to be acquired early that does not require significant working memory resources (adjacent SV agreement).

Studies investigating SV agreement processing show that adult monolinguals (e.g., Kaltsa et al. 2016) and early bilinguals (e.g., Albirini et al. 2013) produce and process SV agreement, but late bilinguals exhibit high variability (see DeLuca et al. 2019, for a review). This variability can be explained in terms of AoA and proficiency, but studies examining these factors have generated mixed findings. For AoA, studies consistently show no AoA effects in lower proficiency early and late bilinguals (Wartenburger et al. 2003), but it is unclear whether AoA modulates SV agreement processing in higher proficiency early and late bilinguals (Wartenburger et al. 2003) or not (Foote 2011; Rodríguez and Reglero 2015). Regarding proficiency, online studies with implicit tasks regularly show that lower proficiency late bilinguals are insensitive and near-native late bilinguals sensitive to SV agreement violations, but data on intermediate and advanced late bilinguals are inconclusive (see Armstrong et al. 2018, for a review). Heeding the pitfalls of studies examining morphosyntactic processing in early and late bilinguals, the inconclusiveness of studies investigating SV agreement processing in late bilinguals, and the scarcity of studies exploring SV agreement processing in early bilinguals, a study of this nature is long overdue. The findings of our study are not only informative for L2 morphosyntactic processing studies. In most L2 studies, AoA and proficiency are confounded (e.g., Hernandez 2013; Li 2013; Monner et al. 2013), and it is difficult to determine “whether AoA effects are a proxy for proficiency effects, or whether they reflect some underlying age-related changes to the way in which the brain processes language” (Berghoff et al. 2021).

2. Background

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Over 70% of world languages have agreement (Acuña-Fariña 2009), and many of these languages express SV agreement overtly via suffixes. Yet, late bilinguals have persistent trouble acquiring L2 morphosyntactic agreement, and the reason why remains elusive, despite over half a century of research. On the one hand, representational deficit accounts claim that adults cannot acquire grammatical structures absent in their L1, due to maturational constraints in either L2 representation (Bley-Vroman 1989; Hawkins 2009; Tsimpli and Dimitrakopoulou 2007) or L2 computation (more reliance on lexical, semantic, and pragmatic information than grammatical information, Clahsen and Felser 2006, 2018; VanPatten 2015). On the other hand, representational accessibility accounts argue that L2 difficulties are not age-related and that adults can acquire grammatical structures absent in their L1. L2 errors are attributed to representational difficulties with new morphology (McCarthy 2008) and morphosyntax (Lardiere 2005) or to computational deficiencies with marked morphology retrieval (Haznedar and Schwartz 1997; Prevost and White 2000), lexical access and retrieval (Hopp 2016), retrieval interference (Cunnings 2017), working memory (McDonald 2006), or prediction during L2 processing (Kaan 2014).

In contrast with these models, frequency-based models relate L2 errors to limited L2 experience with morphosyntactic probabilistic patterns (cue availability) and exceptions to the patterns (cue reliability) (MacWhinney 1987, 2012), as well as previous experience skipping suffixes, especially when these are perceptually non-salient and redundant (Ellis 2006). Suffixes’ low reliability, low salience, and high redundancy make them harder to perceive and learn (Ellis 2006; Goldschneider and DeKeyser 2001), particularly when early experience with inflectional morphemes is limited in the L1 (Sagarra and Ellis 2013; Sarkissian and Behney 2018) and the L2 (Bardovi-Harlig 1992, 2000; Dietrich et al. 1995).

2.2. AoA Effects on Morphosyntactic Processing in Early and Late Bilinguals

Despite more than 50 years of research since Lenneberg’s (1967) seminal study and over a hundred studies (Long 2007), the existence of a critical period on L2 acquisition remains controversial. For L2 syntax acquisition, Hartshorne et al. (2018) used a very large sample to disentangle the effects of age, years of experience, and age of exposure from each other. They found a critical period in late adolescence (17.4 years old), in line with interactive specialization (Johnson 2011) and neuroemergentism (Hernandez et al. 2021).

The role of AoA in L2 morphosyntactic acquisition has received heightened attention due to late bilinguals’ persistent difficulty with inflectional morphology. Many studies have investigated this topic by comparing early bilinguals to late bilinguals but have produced mixed findings (see Mayberry and Kluender 2018 for a review). Offline studies reveal that advanced early bilinguals performed more native-like than advanced late bilinguals (production: Håkansson 1995; Bowles 2011; grammaticality judgments: McDonald 2000; Bowles 2011) but that intermediate early bilinguals and late bilinguals performed alike (production: Au et al. 2002; Knightly et al. 2003; grammaticality judgments: Knightly et al. 2003). The AoA effects in advanced, but not intermediate, bilinguals likely do not result from insufficient proficiency, because Foote (2010) found no early bilinguals–late bilinguals differences at beginning, intermediate, and advanced proficiency levels in a sentence fragment completion task.

Online studies examining AoA effects are equally inconclusive. Some studies show that advanced Russian–German early bilinguals exposed to Russian from birth and to German at varying ages of onset processed stem allomorphs of L2 German verbs more effectively with earlier than later AoA in a cross-modal lexical priming task (see Veríssimo et al. 2017 for similar findings with morphological processing in Turkish–German early bilinguals). Additionally, advanced Italian–German early bilinguals activated the same brain areas when making semantic judgments of adjacent article–noun gender, article–noun case, and SV number violations in L1 Italian and L2 German, but advanced Italian–German late bilinguals showed more extensive activation of certain areas while processing L2 German than L1 Italian (though no early bilinguals–late bilinguals differences were found at intermediate levels or at any level in behavioral measures) (Wartenburger et al. 2003).

In contrast, other online studies found no AoA effects. For example, advanced early bilinguals and late bilinguals of Spanish were more sensitive to adjacent than non-adjacent SV number disagreement with present tense verbs in Spanish (Foote 2011), and both groups showed delayed sensitivity effects (Rodríguez and Reglero 2015) in a non-cumulative, self-paced reading task. However, Rodríguez and Reglero mixed person and number violations (e.g., *tú lavan ‘you-2ndperson-singular wash-3rdperson-plural’). This is problematic because person conveys extra syntactic information about the participants in the speech act, producing different brain responses to number and person agreement violations (Mancini et al. 2011). Number suffixes are more salient in some persons than others; English only has SV number agreement in the third person singular in the present tense, and person is acquired before number (Marrero and Aguirre 2003; Meisel 1994; Forsythe 2015). In addition, they used a complex non-cumulative, self-paced reading task. Finally, they interpreted longer RTs in late bilinguals than early bilinguals as proof of AoA effects, but because the difference was obtained in both grammatical and ungrammatical sentences, longer RTs were simply a consequence of general reading speed differences.

These limitations cast doubt on Rodríguez and Reglero’s findings but cannot explain why Wartenburger et al. obtained AoA effects with adjacent SV number agreement but Foote did not. We argue that these incongruencies are due to Foote and Rodríguez and Reglero employing a more cognitively taxing technique (non-cumulative, self-paced reading paradigm) than Wartenburger et al. (judging whether the sentences were correct and whether they made sense). Additionally, two pieces of evidence tear down proposals linking task explicitness to AoA (early bilinguals are better at implicit tasks, but late bilinguals are better at explicit tasks, Bowles 2011) or to cognitive load (explicit tasks are more taxing than implicit tasks, Roberts 2012). First, Foote, Rodríguez and Reglero found a lack of early bilinguals–late bilinguals differences occurring in an implicit task (comprehension questions). Second, Wartenburger et al.’s early bilinguals–late bilinguals differences occurred in an explicit task (grammaticality judgements). Even with this persuasive line of reasoning, the puzzle is still missing one piece: a study exploring the processing of adjacent SV agreement employing a simple implicit task. To fill this gap and to explain the inconclusive findings regarding AoA effects on L2 morphosyntactic processing, we used a reading eye-tracking task, which allows participants to read sentences at their own pace and to re-read text as needed. If our argumentation is correct, AoA effects may not be present at intermediate levels, but they should be obvious at advanced levels. We delve into the role of proficiency on L2 morphosyntactic processing next.

2.3. Proficiency Effects on Morphosyntactic Processing in Early and Late Bilinguals

There is solid evidence that proficiency modulates L2 morphosyntactic processing. Behavioral studies show sensitivity to L2 morphosyntactic agreement violations at higher proficiency, but no sensitivity at lower proficiency (e.g., Sagarra and Herschensohn 2010). In addition, neurocognitive studies indicate that beginning and intermediate L2 learners show different neural representations (e.g., Dehaene et al. 1997) and that higher, but not lower, proficiency late bilinguals activate brain areas similar to those activated in monolinguals (e.g., Vingerhoets et al. 2003).

Regarding SV agreement, L2 production studies also show proficiency effects (Jackson et al. 2018; Ma and Zou 2018; and Jensen et al. 2020), but online studies with late bilinguals are inconclusive, and those contrasting early bilinguals and late bilinguals are scarce. For late bilinguals, eye-tracking data show that intermediate and advanced English–Spanish and Romanian–Spanish late bilinguals are sensitive to SV violations (Sagarra 2021), but beginners are not, regardless of having an L1 with rich morphology (Romanian) or with analogous number suffixes (English, Romanian) (Sagarra 2014). Likewise, ERP data reveal that intermediate Chinese–English late bilinguals are sensitive to the violations, but English natives show a larger P600 with quantificational rather than non-quantificational cues (Armstrong et al. 2018). Also, intermediate and advanced Italian–German and German–Italian late bilinguals are sensitive to the violations, but sensitivity is delayed more in intermediate than advanced late bilinguals (Rossi et al. 2006). Delayed processing can be a sign of knowledge that has not been automatized yet due to insufficient L2 knowledge, and that requires more cognitive effort during online processing. With respect to advanced late bilinguals, they are sensitive to the violations in self-paced reading (Hopp 2013; Rodríguez and Reglero 2015), speedy grammaticality judgments (Hopp 2013), eye-tracking (Yao and Chen 2017), and ERPs (Rossi et al. 2006).

Contrarily, other studies show that intermediate and advanced late bilinguals are insensitive to SV violations. For intermediate late bilinguals, self-paced reading data showed that English–Spanish late bilinguals (Rodríguez and Reglero 2015; VanPatten et al. 2012) and Chinese–English late bilinguals (Yao and Chen 2017) were insensitive to SV person–number violations (but VanPatten et al. found that they were sensitive to VS violations in which verb tense information is not redundant). Additionally, ERP data revealed that intermediate French–English late bilinguals processed adjacent and non-adjacent SV number violations as semantic rather than morphosyntactic like French natives (Reichle et al. 2013). Regarding advanced late bilinguals, self-paced reading data revealed that Chinese–English late bilinguals were insensitive to SV number violations (Yao and Chen 2017), and that English–Spanish late bilinguals failed to show native-like agreement attraction effects (Jegerski 2016). Furthermore, ERP data indicate that SV number violations produced late frontal negativities in advanced Chinese–English late bilinguals but a P600 effect in English natives (Chen et al. 2007).

The inconsistent findings about intermediate and advanced late bilinguals could be due to a combination of task demands and individual differences in working memory. This is a feasible possibility, considering that Yao and Chen (2017) found sensitivity effects in an eye-tracking task but not a self-paced reading one, and that Sagarra (2021) reported that natives and non-natives with a higher working memory detected SV number violations earlier than lower working memory ones (see Hartsuiker and Barkhuysen 2006, and Lago and Felser 2018 for further evidence of working memory and cognitive load influencing L2 processing of SV agreement).

The vast array of online studies investigating L2 processing of SV agreement contrasts with the scarcity of research comparing late bilinguals to early bilinguals at different proficiency levels. Wartenburger et al. (2003) investigated the effects of both AoA and proficiency on neural correlates of grammatical and semantic judgments in Italian–German bilinguals who learned their L2 at different ages and had different proficiency levels. They found that AoA affected morphosyntactic processing and proficiency-modulated semantic processing (see Weber-Fox and Neville 1996 for similar ERP findings with other structures), but their use of an explicit task (grammaticality judgements) assessed conscious processes. To understand how SV agreement is processed during comprehension, we examined AoA and proficiency effects using an implicit task: a reading eye-tracking task.

3. The Study

We investigated the role of AoA and proficiency on the processing of Spanish adjacent SV number agreement in third-person verbs, using a reading eye-tracking task with semantic judgments. First, adjacent number agreement was adopted because longer distance hinders L2 morphosyntactic processing (Foote 2010; Franck et al. 2002; see Biondo et al. 2018 for SV person-number relations) and because number agreement is acquired earlier than other structures such as tense. Second, Spanish SV number agreement was chosen because Spanish is an agreement-based, null-subject language where a subject’s number and person are consistently encoded in verbal suffixes, whereas English requires explicit subjects and only marks verbal number differences in the third-person singular of regular present tense verbs (he eats vs. they eat) (third-person singular is generally acquired before the rest of the persons, Meisel 1994). Late bilinguals are known to attend less to morphological cues accompanied by other cues expressing the same meaning lexically (e.g., quantifiers expressing number) or morphologically (e.g., articles and nouns expressing number, like in our study). Third, semantic judgments were used because meaning-based tasks assess unconscious knowledge better than grammar-based tasks during L2 reading (Leeser et al. 2011), and because some scholars claim that explicit tasks are cognitively more demanding that implicit ones (Roberts 2012). Fourth, a cognitively simple task was incorporated because previous studies suggest that AoA and proficiency interact with task complexity. In effect, studies reporting AoA effects included advanced early bilinguals and advanced late bilinguals completing a simple task (Wartenburger et al. 2003), whereas those revealing no AoA effects included lower proficiency early bilinguals and lower proficiency late bilinguals completing a simple task (Wartenburger et al. 2003) or advanced early bilinguals and advanced late bilinguals completing a complex task (Foote 2011; Rodríguez and Reglero 2015). Finally, a reading eye-tracking task was selected because it allows for a moment-to-moment analysis that can help reveal the underlying perceptual and cognitive processes of reading (Rayner and Pollatsek 1989), because it is less cognitively taxing than other reading tasks that force participants to read sentences word by word without the possibility to re-read, and because it measures both early and late processing (self-paced reading only measures late processing).

Two questions guided the present study:

- RQ 1: Does AoA modulate SV agreement processing in early and late bilinguals?

First, we predicted that all groups would be sensitive to adjacent SV violations because they are adjacent and thus easy to process. Second, we hypothesized that early bilinguals would show processing patterns more similar to those of monolinguals than those of late bilinguals both in the reading data (correct and incorrect sentences) and the picture data (accuracy at interpreting sentences and amount of reliance on verbs vis à vis subject nouns in incorrect sentences). We base our hypothesis on previous online studies examining morphosyntactic processing in early bilinguals and late bilinguals (see DeLuca et al. 2019 for a review). Importantly, even though the only two online studies on SV number agreement in Spanish show no differences between early bilinguals and L2 learners (Foote 2010; Rodríguez and Reglero 2015), these studies have serious limitations that force us to take their findings with a grain of salt.

- RQ 2: Does proficiency modulate SV agreement processing in early and late bilinguals?

We expect early bilinguals and late bilinguals with higher, but not lower, proficiency in Spanish to be able to attain Spanish monolingual-like morphosyntactic processing. This prediction follows studies indicating that higher, but not lower, proficiency late bilinguals are sensitive to agreement violations (Hoshino et al. 2010; Sagarra 2014; Jiang 2004) and that early bilingual’ processing is on par with, if not better than, that of late bilinguals (Hernandez et al. 2007; Wartenburger et al. 2003; McDonald 2000; Håkansson 1995).

4. Method

4.1. Participants

There were 136 adult participants: 36 Spanish monolinguals, 50 late bilinguals (L1 English, L2 Spanish), and 50 early bilinguals (L1 Spanish, dominant in English). Participants were 24.57 years old on average (SD = 7.78), held at least a high school degree, and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. The monolingual data were collected in the monolingual region of Teruel, Spain. Monolinguals had basic or no knowledge of other morphologically rich languages, had only lived in Spanish monolingual communities, and had not spent more than 4 months abroad.

The early and late bilingual data were collected from a large North American university. Both bilingual groups had little to basic knowledge of languages other than English and Spanish, and a linear regression showed that they were comparable in both Spanish proficiency, for which β = −0.790, SE = 2.631, t = −0.300, p = 0.765, and general reading speed and linear regression, for which β = 395.286, SE = 205.785, t = 1.921, p = 0.058 (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics for both measures). Table 1 shows that the early bilinguals and the late bilinguals had similar variability in proficiency (i.e., there were lower proficiency early and late bilinguals, mid proficiency early and late bilinguals, and higher proficiency early and late bilinguals). Table 1 only shows one proficiency mean per group because proficiency was entered as a continuous variable in the statistical models. The late bilinguals began learning Spanish more seriously after puberty and were enrolled in Spanish courses at the time of testing. A language background questionnaire showed that they completed elementary, middle, and high school in English and that they had only been exposed to English, apart from attending a Spanish class 25 min per week in elementary school, 2 h 40 min per week in middle and high school, and between 0 min to 2 h 40 min per week at the university. The early bilinguals were born in the U.S. A language background questionnaire revealed that 76% completed elementary school in English and 24% in English and Spanish, 95% completed middle school in English and 5% in English and Spanish, and 67% had taken Spanish classes at the university. Regarding language use, 57% used both Spanish and English at home from ages 0 to 18, and 43% only spoke Spanish in the home. A total of 67% were using both Spanish and English at the university, 33% were only using English, and 90% were using Spanish and English with their friends, whereas 10% used only English with their friends.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for Spanish proficiency test and overall reading speed.

- Materials and Procedure

Participants completed four tasks in this order: a language background questionnaire (5 min), a Spanish proficiency test (10–20 min), an eye-tracking task (20–40 min), and a vocabulary test (10 min):

- Language background questionnaire. The questionnaire contained questions about the participants’ experience and exposure to language during and after childhood, including age of exposure to Spanish and English, number of years studying Spanish, and location and length of time living abroad.

- Spanish proficiency test. Bilingual groups completed an adaption of the Diploma de Español como Lengua Extranjera (DELE). The 56-item multiple choice test measures grammatical knowledge and reading comprehension in Spanish across beginning, intermediate, and advanced levels of proficiency. Adapted versions of DELE tests are often used in studies with bilinguals to measure Spanish proficiency.

- Eye-tracking task. The eye-tracker was a desktop mount EyeLink 1000 Plus (SR Research) with a sampling rate of 1 kHz, spatial resolution of 0.32° horizontal and 0.25° vertical, and an average calibration error of 0.01°. The monitor used was a BenQ XL2420TE display monitor at a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels. Critically, the eye-tracker, monitor, keyboard, mouse, and headphones were identical for the data collected in the U.S. and in Spain.

Participants read sentences at their own pace, fixated on a gray box in the lower right corner of the screen for at least 500 ms, and were then prompted with a new screen containing four pictures. They looked at the pictures and mouse-clicked on the picture that best represented the sentence that they had just read. See Figure 1 for a sample trial.

Figure 1.

Sample trial of the eye-tracking task.

There were four versions of the experiment, and each version contained 85 sentences: 5 practice sentences, 32 experimental sentences (16 per condition), and 48 filler sentences. Non-practice sentences were distributed in blocks following a Latin square design, so that each block contained one sentence per condition, and randomization occurred within and between blocks.

Practice and non-practice sentences contained basic words and structures typical of beginning Spanish textbooks but had less than 20% of cognates to reduce possible priming effects. To avoid practice effects, target nouns did not appear more than twice in the entire experiment, and target verbs only appeared once.

Experimental sentences followed this order: adverbial phrase, subject, verb, object, prepositional phrase. Adverbial phrases were temporal, the subjects were human, the verbs were regular transitive verbs in the third person of present or preterit (indicative mood), and the objects were inanimate. Half of the experimental sentences with singular subjects were in the present (half correct, half incorrect) and half in the preterit (half correct, half incorrect), and half of experimental sentences with plural subjects were in the present (half correct, half incorrect) and half in the preterit (half correct, half incorrect). This is an example of a sentence: Por la tarde la abuela limpia/*limpian el vestido en el lavadero ‘In the evening the grandmother washes/*wash the dress in the laundry.’

After reading each sentence, participants saw four pictures and chose the picture that matched the sentence they had read. The pictures were (1) semantically and grammatically congruent with the subject (e.g., one woman washing a dress), (2) semantically congruent and grammatically incongruent with the subject (e.g., two women washing a dress), (3) semantically incongruent and grammatically congruent with the subject (e.g., a woman washing a dog), and (4) semantically incongruent and grammatically incongruent with the subject (e.g., two women washing a dog). About one-third of the semantic changes applied to subjects (e.g., women for men), one-third to verbs (e.g., eating for drinking), and one-third to objects (e.g., a dog for a dress).

- Vocabulary (late bilinguals and early bilinguals only). This test assessed familiarity with the experimental nouns and verbs to ensure that RTs were not affected by lack of lexical knowledge. Participants had to match a list of Spanish nouns and verbs with a list of English nouns and verbs. All groups performed at ceiling.

4.2. Scoring

The DELE test and the vocabulary test gave 1 point for correct answers and 0 points for incorrect answers. The reading eye-tracking test generated reading and picture data. The reading data measured early and late processing. Early processing was assessed with gaze duration, that is, the duration of all fixations on a word before moving on or looking back somewhere else. Late processing was measured through total time spent, defined as the duration of all fixations on a word, including both first pass and regression fixations. The picture data measured sentence interpretation (all sentences) and cue bias (only incorrect sentences). The sentence interpretation analysis assessed participants’ sentence comprehension and sensitivity to agreement violations (sensitivity could lower accuracy in incorrect trials). For example, in sentences such as Por la tarde la abuela limpia/*limpian el vestido en el lavadero ‘in the evening the grandmother washes/*wash the dress in the laundry,’ participants received 1 point for choosing either the picture of a woman washing a dress or the picture of two women washing a dress (see Figure 1). The cue bias analysis determined whether participants relied on the subject noun or the verb when asked to select pictures about incorrect sentences.

- Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using R (R Core Team 2019) and were carried out with an alpha set at 0.05. The data from the reading and picture data were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models conducted on separate data points. The reading data contained a continuous variable (proficiency) and generated linear mixed-effects models. The picture data only included categorical variables and produced generalized linear mixed-effects models with a binomial distribution. Reading data were first inspected with the R package bestNormalize (Peterson and Cavanaugh 2019), which suggested a log transformation of the data prior to fitting the models. All mixed-effects models were fitted with glmmTMB (Brooks et al. 2017), multiple comparisons were done with emmeans (Lenth 2019), and likelihood-ratio tests were extracted with car (Brooks et al. 2017). For all models, in order to select the most cost-efficient model, different models varying in fixed-effects structure were compared with the R package performance (Lüdecke et al. 2021). Finally, all models included a random intercept for the subject and a random intercept for the item. This random-effects structure was selected because other structures, such as one including random slopes, yielded singularity-related errors or were under-ranked by performance.

Three sets of models were carried out for the reading data: one set for monolinguals, one set for bilinguals, and one set directly comparing monolinguals, early bilinguals, and late bilinguals. Monolingual and bilingual data were analyzed separately in the first two sets of models because of lack of variability in the monolingual group with respect to the Spanish proficiency test results (all monolinguals received 100 points). The models for monolingual data included agreement as a fixed effect, and the models for bilingual data included group (early bilinguals, late bilinguals), proficiency (continuous), agreement (agree, disagree), and all their possible interactions as fixed effects. AoA (group) was not entered as a continuous variable in the bilingual models due to the lack of variability in the early bilingual group (all participants began learning Spanish at age 0). In addition to these variables, we assessed the possible main effects of verb number (singular, plural) and verb tense (present, preterit) to control for their potential influence on variance explanation. Whenever verb number or verb tense significantly explained part of the variation, they remained in the model. Verb tense was retained for bilinguals’ total time on subject nouns and verbs. Verb number was retained for both monolinguals’ and bilinguals’ gaze duration on verbs and total time on verbs, as well as for bilinguals’ verb bias (picture data). Because the models with the bilinguals did not show proficiency effects on SV agreement, except for shorter RTs on nouns and verbs overall, we ran another model directly comparing monolinguals, early bilinguals, and late bilinguals, excluding proficiency as a factor. The rationale of comparing the three groups directly was to find stronger evidence to support the conclusion that early bilinguals show similar processing to monolinguals compared to late bilinguals. The models with the three groups included group (monolinguals, early bilinguals, late bilinguals), agreement (agree, disagree), and verb number (singular, plural), and all their possible interactions as fixed effects. In addition, we measured the main effects of verb tense (present, preterit), and it was retained for total time on subject nouns and total time on verbs. Verb number, but not verb tense, was considered in the interactions based on the results obtained in the bilingual models, following the recommendation of an anonymous reviewer.

5. Results

The reading data produced eight linear mixed-effect models for monolinguals, eight for bilinguals, and eight for the three groups: gaze duration on verbs, object articles and object nouns, as well as total time on subject articles, subject nouns, verbs, object articles, and object nouns. Models with gaze duration and total time on object articles and object nouns were conducted to control for possible delayed processing effects, which are typical in bilinguals. Picture data produced two generalized linear mixed-effects models for monolinguals, two for bilinguals, and two for the three groups: picture interpretation (accuracy) and verb picture bias. Due to space limitations, we only report significant main effects and interactions, but we have included the full model outputs in 30 tables in one of the appendices in the Supplementary Materials.

5.1. Reading Data

Table 2 displays the means for gaze duration and total time measurements for the subject determiner phrase and the verb for all groups.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for gaze duration and total time in milliseconds.

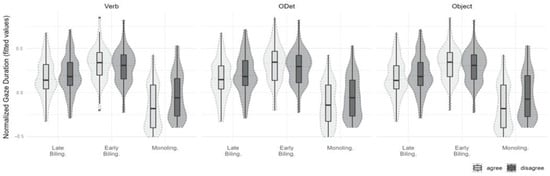

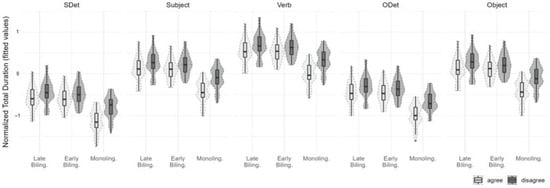

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the normalized duration means based on fitted values resulting from the statistical models.

Figure 2.

Normalized gaze duration means (fitted values from statistical models).

Figure 3.

Normalized total time duration means (fitted values from statistical models).

- Reading data with monolinguals.

A significant effect of agreement on gaze duration on verbs (β = 0.338, SE = 0.070, t = 4.854, p = 0.001) and total time on subject articles (β = 0.224, SE = 0.104, t = 2.854, p = 0.031), subject nouns (β = 0.294, SE = 0.077, t = 3.817, p = 0.001), verbs (β = 0.515, SE = 0.069, t = 7.454, p = 0.001), object articles (β = 0.349, SE = 0.110, t = 3.159, p = 0.002), and object nouns (β = 0.235, SE = 0.078, t = 3.015, p = 0.003) indicates longer reading times in incorrect than correct trials. In addition, a significant main effect of verb number on gaze duration on verbs (β = 0.263, SE = 0.045, t = 3.967, p = 0.001), and total time on subject nouns (β = 0.162, SE = 0.077, t = −2.103, p = 0.035) and verbs (β = 0.140, SE = 0.069, t = 2.044, p = 0.041) showed longer reading times with plural than singular verbs on gaze duration on verbs and total time on verbs but longer reading times with singular than plural verbs in total time on subject nouns.

- Reading data with bilinguals.

A significant effect of agreement on total time on verbs (β = 0.117, SE = 0.070, t = 4.854, p = 0.001) showed that bilinguals looked longer at verbs in incorrect trials than those in correct trials, but not during first pass reading like the monolinguals. A significant effect of group on total time on subject articles (β = −0.853, SE = 0.395, t = −2.158, p = 0.031) and object articles (β = −1.016, SE = 0.448, t = −2.266, p = 0.023) revealed that early bilinguals looked longer at subject and object articles than late bilinguals. A significant interaction between agreement and group for gaze duration on object nouns (β = 1.490, SE = 0.565, t = 2.637, p = 0.008) and total time on object articles (β = 0.265, SE = 0.130, t = 2.032, p = 0.042) and object nouns (β = 1.054, SE = 0.512, t = 2.059, p = 0.040) indicates that neither early bilinguals nor late bilinguals were sensitive but that the difference between disagreement and agreement was slightly larger for the late bilinguals than the early bilinguals (although pairwise comparisons were non-significant for gaze duration on object nouns. Additionally, as expected, there was a significant main effect of proficiency on total time on subject nouns (β = −0.009, SE = 0.003, t = −2.625, p = 0.009), verbs (β = −0.010, SE = 0.004, t = −2.675, p = 0.007) and object articles (β = −0.012, SE = 0.006, t = −2.158, p = 0.031), due to lower proficiency bilinguals’ slower reading times as compared to higher proficiency bilinguals. With regard to verb tense and verb number, there was a significant main effect of verb tense on total time on subject nouns (β = −0.230, SE = 0.112, t = −2.058, p = 0.040) and verbs (β = 0.234, SE = 0.064, t = 3.651, p = 0.001) but in opposite directions. On the one hand, bilinguals looked longer at subject nouns with present verbs than those with past tense verbs. On the other hand, bilinguals looked longer at verbs with past than present tense verbs. Finally, there was a significant main effect of verb number on total time on verbs (β = 0.285, SE = 0.045, t = 6.389, p = 0.001), such that bilinguals looked longer at plural than singular verbs.

- Reading data with monolinguals, early bilinguals, and late bilinguals.

A significant main effect of agreement on gaze duration on verbs (β = 0.329, SE = 0.088, t = 3.714, p = 0.001) and total time on subject articles (β = 0.261, SE = 0.073, t = 3.566, p = 0.001), subject nouns (β = 0.282, SE = 0.081, t = 3.496, p = 0.001), verbs (β = 0.502, SE = 0.076, t = 6.494, p = 0.001), object articles (β = 0.356, SE = 0.115, t = 3.097, p = 0.002), and object nouns (β = 0.229, SE = 0.087, t = 2.623, p = 0.009) indicates that the three groups were sensitive to the violations. Then, a significant main effect of group on gaze duration on verbs (β = 0.484, SE = 0.120, t = 4.025, p = 0.001), object articles (β = 0.329, SE = 0.094, t = 3.520, p = 0.001), and object nouns (β = 0.474, SE = 0.098, t = 4.834, p = 0.001), as well as total time on subject articles (β = 0.345, SE = 0.092, t = 3.728, p = 0.001), subject nouns (β = 0.519, SE = 0.107, t = 4.831, p = 0.001), verbs (β = 0.488, SE = 0.114, t = 4.274, p = 0.001), object articles (β = 0.583, SE = 0.130, t = 4.484, p = 0.001), and object nouns (β = 0.598, SE = 0.110, t = 5.458, p = 0.001) reveal longer reading times in early and late bilinguals than monolinguals, with no differences between the two bilingual groups. A significant interaction between agreement and group for gaze duration on verbs (β = −0.285, SE = 0.113, t = −2.529, p = 0.011) and total time on subject nouns (β = −0.215, SE = 0.102, t = −2.096, p = 0.036) reveal longer reading times for incorrect trials than correct trials in the monolinguals, but not in the bilinguals. However, the significant interaction between agreement and group for total time on verbs (β = −0.325, SE = 0.097, t = −3.351, p = 0.001) indicates that, when processing the verbs, all groups showed sensitivity to the violations (i.e., the pairwise comparisons did not show an interaction); interestingly, the p values showed that the monolinguals were the most sensitive (p = 0.000), followed by the early bilinguals (p = 0.003), and, finally, the late bilinguals (p = 0.005). Logically, later on, when processing the word following the verb (i.e., the object article), the late bilinguals (p = 0.000) showed delayed processing effects, whereas the early bilinguals no longer reacted to the violations (p = 0.498). With respect to verb tense and verb number, there was a significant main effect of verb tense on total time on verbs (β = 0.199, SE = 0.061, t = 3.240, p = 0.001), such that all groups looked longer at past than present tense verbs. Verb number produced a significant main effect of gaze duration on verbs (β = 0.268, SE = 0.044, t = 6.124, p = 0.001) and for total time on verbs (β = 0.251, SE = 0.038, t = 6.672, p = 0.001), such that all groups looked longer at plural than singular verbs. Finally, verb number generated a significant interaction between verb number and agreement for total time on subject articles (β = −0.266, SE = 0.102, t = −2.618, p = 0.009), indicating that all groups looked longer at subject articles in disagreeing conditions than agreeing conditions with singular verbs (p = 0.001), but not with plural verbs (p = 0.784).

5.2. Picture Results

Table 3 shows that all groups comprehended the experimental sentences well (the minimum value was 96.45%). This is an important finding considering that we aimed at examining SV agreement processing during comprehension. In addition, all groups barely relied on verbs to choose pictures in incorrect sentences (the maximum value for verb bias was 17.51% of all incorrect sentences). This means that, after reading an incorrect sentence such as *Por la tarde la abuela limpian el vestido en el lavandero ‘*In the evening the grandmother wash the dress in the laundry,’ participants chose the pictures containing one old woman more often than those containing two old women, because the subject noun was singular, and they relied more on the subject than the verb.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics in % for accuracy on picture selection.

As previously mentioned, the picture data generated two analyses: one for sentence interpretation and another for verb bias. For sentence interpretation, in Table 3, the model with only bilinguals and with the three groups revealed a significant main effect of group (OR = 11.482, SE = 12.128, t = 2.311, p = 0.021, and OR = −0.027, SE = 0.011, t = −2.403, p = 0.016, respectively), indicating that late bilinguals understood the sentences more accurately than early bilinguals (p = 0.021 for the model with bilinguals and p = 0.005 for the model with all groups). In addition, the monolinguals understood the sentences better than early bilinguals, but the p value was very close to reaching non-significance (p = 0.049). Finally, monolinguals and late bilinguals understood the sentences equally well (p = 1.000).

Concerning verb bias, both the model with only monolinguals (OR = 2.328, CI = 1.712–5.057, p = 0.001) and the model with only bilinguals (OR = 2.343, SE = 0.596, t = 3.346, p = 0.001) produced a significant main effect on verb number, indicating a general preference of choosing a picture in line with the verb when the verb was plural rather than singular in incorrect trials. The model with all groups revealed a significant main effect of verb tense (OR = −0.174, SE = 0.070, t = −2.495, p = 0.013), but pairwise comparisons were non-significant. Finally, the model with all groups showed a significant triple interaction among group, verb number, and verb tense (OR = −0.233, SE = 0.117, t = −1.983, p = 0.047), such that monolinguals and late bilinguals relied more on plural present verbs (lavan ‘they wash’) than on singular present verbs (lava ‘(s)he washes’), but early bilinguals spent the same amount of time reading lavan and lava (and all groups spent the same amount of time reading lavó ‘(s)he washed´ and lavaron ‘they washed’).

6. Discussion

This study investigated the effects of AoA and proficiency on morphosyntactic processing. Monolinguals and intermediate and advanced early bilinguals and late bilinguals read sentences in Spanish with adjacent SV number agreement and disagreement and chose one of four pictures while their eye-movements were recorded. The first research question investigated AoA effects on morphosyntactic processing. Our data did not provide evidence of any AoA effects. First, all groups were sensitive to violations. Second, monolinguals used articles to compute agreement (longer total times on articles in incorrect than correct conditions), and early bilinguals used articles to a greater extent than late bilinguals (longer total times on subject and object articles in early than late bilinguals). However, the early bilinguals’ greater attention to articles is probably not due to earlier AoA because there were no other AoA effects, and it is probably not due to English lacking definite article–noun agreement because the early bilinguals were dominant in English. We argue that early bilinguals’ heightened attention to articles is a result of their increased use of Spanish compared with the late bilinguals. Third, early and late bilinguals were equally sensitive to agreement violations. The only exception (late bilinguals being more sensitive to violations than early bilinguals in object articles and object nouns) was due to late bilinguals´ reduced use of Spanish, which slowed their computation of agreement producing sensitivity effects at the verb and the two words following the verb. Fourth, early bilinguals’ reduced experience with written Spanish caused them to read more slowly, interpret sentences less accurately, and be less sensitive to subtle typographical suffix changes (lavan-lava ‘they wash-s/he washes) than late bilinguals. The second research question examined proficiency effects on morphosyntatic processing. Our data did not produce any proficiency effects, apart from the finding that higher proficiency bilinguals read faster than lower proficiency bilinguals. Finally, our data indicate that all groups spent more time (i.e., greater attention) reading verbs that were perceptually more salient than perceptually less salient in terms of number (longer RTs on plural than singular verbs) and tense (longer RTs on preterit than present verbs).

6.1. AoA and Morphosyntactic Processing

The first research question examined whether earlier AoA facilitated SV number agreement processing. The hypothesis that all groups would be sensitive to agreement violations was supported. However, the hypothesis that early bilinguals would behave more similarly to monolinguals than late bilinguals was partially supported by the reading data and rejected by the picture interpretation and verb bias data.

With regard to sensitivity to agreement violations, there was a significant main effect for agreement with all groups and variables. The statistical analyses of all groups showed longer reading times in incorrect than correct sentences in monolinguals, early bilinguals, and late bilinguals in gaze duration on verbs, and total time on subject articles, subject nouns, verbs, object articles, and object nouns. Monolinguals’ recognition of SV agreement violations has been shown on numerous occasions behaviorally, electrophysiologically, and neuroanatomically (see Mancini 2018 for a comprehensive review). The bilinguals’ sensitivity to the violations is in line with online studies reporting that non-beginning bilinguals are sensitive to morphosyntactic violations in both nominal agreement such as gender (early and late bilinguals: Foote 2010; Wartenburger et al. 2003; late bilinguals: Keating 2010; Morgan-Short et al. 2010) and verbal agreement such as tense (late bilinguals: Ellis and Sagarra 2011) and number (early and late bilinguals: Rodríguez and Reglero 2015; late bilinguals: Armstrong et al. 2018; Hopp 2013; Jegerski 2016; Rossi et al. 2006; Sagarra 2021; Sagarra and LaBrozzi 2018; Yao and Chen 2017).

With respect to early bilinguals showing processing patterns closer to monolinguals in the reading data, monolinguals showed longer total times spent on subject articles in incorrect than correct conditions (i.e., they re-read the articles to “double check” that there was a violation). The findings that monolinguals rely on inflected articles to compute morphosyntactic agreement is well documented in several languages (e.g., see Padovani and Cacciari 2003 for Italian, and Lew-Williams and Fernald 2010 for Spanish). Regarding the bilinguals, the significant main effect of group on total time on subject articles and object articles in the bilingual analyses indicates that early bilinguals spent more time reading articles than late bilinguals, regardless of whether or not there was a violation. One can claim that this pattern is due to late bilinguals being faster readers than early bilinguals because early bilinguals’ experience with Spanish is mostly oral. However, the fact that early bilinguals were slower than late bilinguals in articles (total time on subject articles and object articles) but not in nouns (gaze duration and total time on subject nouns and object nouns) or in verbs (gaze duration and total time on verbs) tears down this proposal and confirms that early bilinguals looked longer at articles because they relied on them to compute morphosyntactic agreement, such as monolinguals.

Why are late bilinguals relying on articles less than early bilinguals? Is it due to their delayed AoA or their reduced use of the target language? Considering that late bilinguals rely more on articles when they are present rather than absent in their L1 (e.g., Faber 2017), one can conclude that late bilinguals’ reduced attention to articles is due to a lack of number suffixes in English articles (theSING/PL). However, this explanation is dubious, because early bilinguals relied more on articles than late bilinguals, despite being more dominant in English than Spanish. We argue that late bilinguals’ reduced attention to articles emerges from their lower use of Spanish compared to early bilinguals. Here, language use refers to the frequency with which a language is actively used. Our language-based explanation finds its roots in monolingual and bilingual studies. Monolinguals studies indicate that higher language experience facilitates speakers’ ability to make distributional associations (Romberg and Saffran 2010), and other statistical learning studies), and bilingual studies identify language use as one of the most influential factors on L2 acquisition (Ranta and Meckelborg 2013). For instance, the extra time using the L2 in immersion contexts facilitates attention to inflectional morphology to compute L2 morphosyntactic agreement (Sagarra and LaBrozzi 2018; Faretta-Stutenberg and Morgan-Short 2018). Furthermore, recent studies indicate that language use, rather than AoA or L2 proficiency, changes white matter infrastructure during language processing (Del Maschio et al. 2020). Finally, if late bilinguals’ reduced attention to articles is due to AoA, we should observe other AoA effects in both the reading data and the picture data. In the following paragraphs, we demonstrate that our data did not show other signs that earlier AoA facilitates morphosyntactic processing. In effect, our data reveal no differences between early and late bilinguals or late bilinguals behaving more similarly to monolinguals than early bilinguals.

First, the interaction between agreement and group for gaze duration on verbs and total time on subject nouns in the models with all groups revealed that only the monolinguals were sensitive to the violations in these variables, and that there were no differences between early and late bilinguals.

Second, the interaction between agreement and group for total time on object articles and object nouns in the models with bilinguals revealed that early bilinguals showed less sensitivity to violations (i.e., smaller difference between agreement and disagreement) than late bilinguals. This finding does not mean that earlier AoA hinders morphosyntactic processing because late bilinguals’ increased sensitivity to violations was only present in object articles and object nouns (i.e., the words following the verb). Delayed processing effects are considered an indication of cognitive difficulties during online processing, and they are typical of late bilinguals and other populations performing tasks with reduced expertise (think of monolingual children when they begin to read). Therefore, we attribute late bilinguals’ delayed processing effects to their reduced use of Spanish, rather than their delayed AoA. Late bilinguals’ reduced use of Spanish slowed down their computation of agreement. Further evidence of this interpretation lies in the fact that early bilinguals read the words in the rest of the sentence in correct conditions more slowly than those in incorrect conditions. We discuss this finding in the following paragraph.

Third, reading data and picture interpretation data consistently show that early bilinguals were slower readers and less accurate in interpreting sentences than late bilinguals. Actually, monolinguals understood the sentences more accurately than early bilinguals but as well as late bilinguals. Again, we attribute these results to language use and not AoA. Early bilinguals have had less experience with written language than late bilinguals, following the large body of research indicating that early bilinguals are worse at written than oral tasks (e.g., Montrul et al. 2008).

Fourth, the triple interaction among group, verb number, and verb tense in the picture verb bias analysis reveals that monolinguals and late bilinguals, but not early bilinguals, relied more on plural present verbs (lavan ‘they wash’) than on singular present verbs (lava ‘(s)he washes’). The lack of differences between lavan and lava in the early bilinguals could be a result of their reduced experience with written Spanish, which made them less sensitive to the final -n in lavan, a subtle difference with lava. However, early bilinguals responded to the more obvious perceptual difference between plural past verbs (lavaron ‘they washed’) and singular past verbs (lavó ‘s/he washed’) (we explain this finding in our discussion to our third research question).

6.2. Proficiency and Morphosyntactic Processing

The second research question explored whether proficiency affected SV number agreement processing in early and late bilinguals. Our prediction that higher proficiency early bilinguals and late bilinguals would show more native-like processing patterns than lower proficiency early bilinguals and late bilinguals was rejected. The model with the bilinguals revealed a significant main effect of proficiency on total time on subject nous, verbs, and object articles, showing shorter reading times at these words for higher than lower proficiency bilinguals. This trend is simply due to higher proficiency bilinguals looking at words for a shorter period of time than lower proficiency bilinguals. Therefore, there is no evidence of an association between higher proficiency and more native-like morphosyntactic processing. The absence of an interaction between agreement and proficiency was unexpected, because numerous studies suggest that sensitivity to morphosyntactic violations increases with proficiency in both nominal agreement (gender: Sagarra and Herschensohn 2010; number: Song 2015) and verbal agreement (number: Jegerski 2016; Rossi et al. 2006; Sagarra 2021; Yao and Chen 2017; Chen et al. 2007). The lack of interaction between agreement and proficiency can be explained in two ways. One possibility is that the interaction was not significant because the structure (adjacent SV agreement) was too easy for our highly proficient bilinguals, creating a ceiling effect. Future studies with non-adjacent SV agreement or another type of agreement dependency that is typically acquired late and less proficient bilinguals could confirm our hypothesis (there are studies on non-adjacent SV agreement, but they exclude beginning learners). Another possibility is that language use, rather than proficiency, affects the processing of adjacent SV agreement. This explanation is in line with both: (a) eye-tracking evidence that greater code-switching use increases sensitivity to code-switching rules in L2 learners of the same L2 proficiency (Beatty-Martínez et al. 2020); and (b) neuroanatomical proof that language use, rather than AoA or L2 proficiency, modulates the brain’s structural connectivity during language processing (Del Maschio et al. 2020).

6.3. Verb Number, Verb Tense, and Morphosyntactic Processing

One-fourth of the experimental sentences contained singular present verbs, one-fourth contained singular past verbs, one-fourth plural present verbs and one-fourth plural past verbs. This allowed us to examine the possible effects of verb number (singular vs. plural) and verb tense (present vs. preterit) on morphosyntactic processing. This is important because in Spanish, third-person regular verbs in plural forms are more salient than singular forms both in the present (the suffix in lavan ‘they wash’ is longer than the one in lava ‘s/he washes’) and the past (the suffix in lavaron ‘they washed’ is longer than the one in lavó ‘s/he washed’), and preterit forms are more salient than present forms both in singular (the suffix in lavó ‘s/he washed’ has typographical and acoustic stress, but the one in lava ‘s/he washes’ does not) and in plural (the suffix in lavaron ‘they washed’ is longer than the one in lavan ‘they wash)’). Perceptual salience is the ability of a stimulus to stand out from the rest and to attract attention by virtue of physical characteristics (Ellis 2019; Styles 2006). Perceptual salience affects all areas of L1 and L2 acquisition (see Dube et al. 2019 for a review), including morphosyntactic processing. Perceptual salience is particularly relevant in our stimuli, because the verbs are preceded by number-marked articles and nouns. Verbal suffixes’ redundancy makes them more difficult to notice than other words with bound morphemes. This explains why VanPatten et al. (2012) found that English–Spanish late bilinguals are more sensitive to VS than SV violations. As shown in the salience studies cited in the next paragraph, increased salience calls readers´ attention and results in longer reading times.

Regarding verb number effects, the results show a main effect for verb number on both gaze duration and total time on verbs, indicating that all groups looked longer at plural than singular verbs. The reduced time devoted to singular verbs had logical consequences on second-pass reading times on subject articles and nouns. First, monolinguals regressed longer to subject nouns after having read singular rather than plural verbs (models with monolinguals). Second, all groups regressed longer to subject articles in incorrect than correct sentences in singular verbs (but equally in plural verbs) (models with all groups). In other words, the increased salience of plural verbs made participants pay more attention to them and reduced their need to re-read subject articles and nouns. Concerning verb tense effects, the results reveal a main effect of verb tense on total time on singular and plural verbs, indicating that all groups looked longer at preterit than present verbs, regardless of whether the sentences were correct or incorrect. In the same line, all groups relied more on verbs than subject nouns to choose pictures in sentences with preterit rather than present verbs. Finally, we argue that the lack of interaction between verb number/tense and proficiency (see Gass et al. 2003) could be due to our study using a simpler structure and task or AoA and proficiency not affecting the processing of adjacent SV number agreement.

Taken together, these results of verb number and verb tense are aligned with studies showing that plural verbs and preterit verbs are more salient (Cutler and Carter 1987; Ellis 2006; Goldschneider and DeKeyser 2001) and that perceptual salience affects morphosyntactic processing in monolinguals (see Dube et al. 2019, for a review) and bilinguals. For late bilinguals, Simoens et al. (2018) reported that they attend more to longer than shorter suffixes, and Behney et al. (2018) found that they attend more to past than present verbs (see also Ellis 2017 for a review of studies indicating that perceptual salience affects L2 acquisition). For early bilinguals, DeKeyser et al. (2018) observed that early bilinguals attend more to stressed than unstressed suffixes. Importantly, research on perceptual salience and morphosyntactic processing in early bilinguals is scant (Sagarra 2019), making our study crucial to determining the role of salience in heritage speakers in their less used input modality, the written mode (Montrul 2011).

One could argue that the differences in verb number and verb tense could be a result of attraction effects, L1 transfer, or morphological markedness rather than perceptual salience. First, some scholars propose that constituents that encode salient information are often prosodically reduced and unaccented, and that, sometimes, a constituent that should be contrastive, and therefore accentable, is not, due to a grammaticality illusion. For example, Wagner (2010) showed that attraction effects are caused by plural, but not singular, constituents. If our verb number and verb tense results had emerged from “grammaticality illusions,” we would have found a significant interaction between verb number/tense and agreement. However, participants’ excess attention to plural and preterit verbs occurred both in agreeing and disagreeing conditions. Second, with respect to L1 transfer, SV disagreement is explicit in Spanish and English in the third person of the present tense (e.g., la abuela limpia/*limpian el vestido ‘the grandmother washes/*wash the dress’), whereas the violation is only obvious in Spanish in the past (e.g., la abuela limpió/*limpiaron el vestido ‘the grandmother washedSG/*washedPL). However, longer reading times in past than present verbs for Spanish natives (there was a significant main effect of verb tense on total time on verbs in models including all groups) means it could not be due to L1 transfer. Third, regarding morphological markedness, some scholars organize morphemes into default (more frequent) and marked (less frequent) (e.g., Halle and Marantz 1994). In inflectional languages, past tense tends to be more overtly marked than present tense in the plural (compare they painted with they paint) (Dahl 1985; Bybee et al. 1994). Although some scholars claim that default morphemes are easier to learn than marked morphemes due to representational or computational deficits in comprehension or production (see Rothman 2007, for a review), L1 and L2 online studies are inconclusive. Some studies reveal a default preference, others a marked preference, and others no preference (see Alemán Bañón et al. 2012, for a review). Importantly, the studies yielding markedness effects have consistently employed non-cumulative explicit tasks, which are cognitively more demanding than cumulative implicit tasks. Two online studies suggest that morphological markedness is modulated by perceptual salience and cognitive load during online sentence comprehension. On the one hand, Sagarra (2019) used an implicit reading eye-tracking task and found L1 and L2 markedness effects in noun–adjective number agreement, but not gender agreement, because number suffixes are perceptually more salient than gender suffixes. On the other hand, López Prego and Gabriele (2014) reported markedness effects in timed, but not in untimed, tasks. Because past tense suffixes in Spanish are both perceptually salient and marked, we cannot tease the two apart. Future studies contrasting salient default forms with salient marked ones will shed further light on perceptual salience effects on L1 and L2 morphosyntactic processing.

7. Conclusions

We investigated the effects of age of acquisition and proficiency on morphosyntactic processing in monolinguals and bilinguals. Spanish monolinguals and intermediate and advanced early and late bilinguals read sentences in Spanish containing adjacent SV number agreement and disagreement, and they chose the picture that corresponded to the sentence they had just read. Picture selection data show that all groups comprehended the sentences well and that they all relied more on subjects than verbs in incorrect sentences. Eye-tracking reading data reveal that all groups were sensitive to the violations. Importantly, there were no clear AoA or proficiency effects. Regarding AoA, early bilinguals’ longer RTs on subject and object articles than late bilinguals, as well as early bilinguals’ less delayed processing effects than late bilinguals, seem to be the result of early bilinguals using Spanish more often than late bilinguals, rather than earlier AoA. Apart from these two findings, the rest of the reading data do not show either differences between early and late bilinguals or late bilinguals showing processing patterns closer to monolinguals than early bilinguals. Early bilinguals were slower readers and less accurate at interpreting written sentences than late bilinguals due to early bilinguals’ reduced use of written Spanish. Furthermore, monolinguals and late bilinguals relied more on verbs to choose pictures in incorrect sentences with plural than singular verbs, but verb number was irrelevant for early bilinguals, probably because early bilinguals’ reduced use of written Spanish decreases their attention to typographical suffixes. Concerning proficiency, neither the picture data nor the reading data reveal any proficiency effects on morphosyntactic agreement processing. The only proficiency effect consisted of the logical finding that higher proficiency bilinguals are faster readers than lower proficiency bilinguals. Finally, the perceptual salience of verbal suffixes (longer RTs for plural than singular verbs and for past than present verbs) affected all groups, except early bilinguals, who seemed blind to singular–plural differences in present (but not past) verbs, probably due to their reduced experience with written Spanish.

Taken together, our findings do not provide evidence of a critical period and indicate that the processing of adjacent SV agreement depends on perceptual salience and language use, rather than AoA or proficiency. These findings support usage-based theories, which claim that acquisition of any type of knowledge (linguistic or not) depends on factors related to attention and memory, such as perceptual salience and exemplar type- and token-frequency. In addition, our findings support bilingualism-induced neuroplasticity models, which propose that the brain adapts functionally and structurally to specific bilingual experiences (see DeLuca et al. 2020, for a review). For example, our findings are in line with recent studies showing that language use, rather than AoA or L2 proficiency, modulates the brain’s structural connectivity during language processing (Del Maschio et al. 2020), particularly during attentional control tasks (DeLuca et al. 2020). Future studies should continue investigating multiple factors simultaneously to untwine their relative weight on L2 morphosyntactic processing. For instance, future studies comparing early bilinguals with different degrees of language proficiency, use, and dominance can shed light onto the contribution of each of these components and the interactions between them for morphosyntactic processing, as well as into what makes early bilinguals different from monolinguals. Our findings support accessibility models against a critical period and usage-based models advocating for the importance of active language use during online processing.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/languages7010015/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S.; Project administration, N.R. and N.S.; Writing—original draft, N.S.; Writing—review & editing, N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rutgers University (protocol code 13-431M, re-approved March 29th, 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acuña-Fariña, Juan Carlos. 2009. The Linguistics and Psycholinguistics of Agreement: A Tutorial Overview. Lingua 119: 389–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albirini, Abdulkafi, Elabbas Benmamoun, and Brahim Chakrani. 2013. Gender and Number Agreement in the Oral Production of Arabic Heritage Speakers. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 16: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán Bañón, José, Robert Fiorentino, and Alison Gabriele. 2012. The Processing of Number and Gender Agreement in Spanish: An Event-Related Potential Investigation of the Effects of Structural Distance. Brain Research 1456: 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, Andrew, Nyssa Bulkes, and Darren Tanner. 2018. Quantificational Cues Modulate the Processing of English Subject–verb Agreement by Native Chinese Speakers. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 40: 731–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, Terry Kit-Fong, Leah M. Knightly, Sun-Ah Jun, and Janet S. Oh. 2002. Overhearing a Language During Childhood. Psychological Science 13: 238–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardovi-Harlig, Kathleen. 1992. The Use of Adverbials and Natural Order in the Development of Temporal Expression. IRAL 30: 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardovi-Harlig, Kathleen. 2000. Tense and Aspect in Second Language Acquisition: Form, Meaning, and Use. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Beatty-Martínez, Anne L., Christian A. Navarro-Torres, and Paola E. Dussias. 2020. Codeswitching: A Bilingual Toolkit for Opportunistic Speech Planning. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behney, Jennifer, Patti Spinner, Susan M. Gass, and Lorena Valmori. 2018. The L2 acquisition of Italian tense. In Salience in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Susan M. Gass, Alison Mackey, Patti Spinner and Jennifer Behney. New York: Routledge, pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghoff, Robyn, Jayde McLoughlin, and Emanuel Bylund. 2021. L1 Activation During L2 Processing Is Modulated by Both Age of Acquisition and Proficiency. Journal of Neurolinguistics 58: 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondo, Nicoletta, Francesco Vespignani, Luigi Rizzi, and Simona Mancini. 2018. Widening Agreement Processing: A Matter of Time, Features and Distance. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 33: 890–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bley-Vroman, Robert. 1989. What is the logical problem of foreign language learning? In Linguistic Perspectives On Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Susan M. Gass and Jacquelyn Schachter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, Melissa A. 2011. Measuring Implicit and Explicit Linguistic Knowledge. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 33: 247–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Mollie E., Kasper Kristensen, Koen J. Van Benthem, Arni Magnusson, Casper W. Berg, Anders Nielsen, Hans J. Skaug, Martin Machler, and Benjamin M. Bolker. 2017. glmmTMB Balances Speed and Flexibility Among Packages for Zero-inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. The R Journal 9: 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan, Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca. 1994. The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect, and Modality in the Languages of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Lang, Hua Shu, Youyi Liu, Jingjing Zhao, and Ping Li. 2007. ERP Signatures of Subject–verb Agreement in L2 Learning. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 10: 161–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clahsen, Harald, and Claudia Felser. 2006. Grammatical Processing in Language Learners. Applied Psycholinguistics 27: 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clahsen, Harald, and Claudia Felser. 2018. Some Notes on the Shallow Structure Hypothesis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 40: 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnings, Ian. 2017. Parsing and Working Memory in Bilingual Sentence Processing. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20: 659–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, Anne, and David M. Carter. 1987. The Predominance of Strong in Syllables in the English Vocabulary. Computer Speech and Language 2: 133–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Östen. 1985. Tense and Aspect Systems. New York: Basil Blackwell. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11858/00-001M-0000-0012-990A-0 (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Dehaene, Stanislas, Emmanuel Dupoux, Jacques Mehler, Laurent Cohen, Eraldo Paulesu, Daniela Perani, Pierre-Francois Van de Moortele, Stéphane Lehéricy, and Denis Le Bihan. 1997. Anatomical Variability in the Cortical Representation of First and Second Language. NeuroReport 8: 3809–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeKeyser, Robert, Iris Alfi-Shabtay, Dorit Ravid, and Meng Shi. 2018. The Role of Salience in the Acquisition of Hebrew as a Second Language: Interaction with Age of Acquisition. In Salience in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Susan M. Gass, Patti Spinner and Jennifer Behney. New York: Routledge, pp. 131–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Maschio, Nicola, Simone Sulpizio, Michelle Toti, Camilla Caprioglio, Gianpaolo Del Mauro, Davide Fedeli, and Jubin Abutalebi. 2020. Second Language Use Rather Than Second Language Knowledge Relates to Changes in White Matter Microstructure. Journal of Cultural Cognitive Science 4: 165–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, Vincent, David Miller, Christos Pliatsikas, and Jason Rothman. 2019. Brain adaptations and neurological indices of processing in adult second language acquisition. In The Handbook of the Neuroscience of Multilingualism. Edited by John W. Schwieter. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 170–96. [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca, Vincent, Katrien Segaert, Ali Mazaheri, and Andrea Krott. 2020. Understanding Bilingual Brain Function and Structure Changes? U Bet! A Unified Bilingual Experience Trajectory Model. Journal of Neurolinguistics 56: 100930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, Rainer, Wolfgang Klein, and Colette Noyau. 1995. Acquisition of Temporality in a Second Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, Sithembinkosi, Carmen Kung, Jon Brock, and Katherine DeMuth. 2019. Perceptual Salience and the Processing of Subject–verb Agreement in 9–11-Year-Old English-Speaking Children: Evidence from ERPs. Language Acquisition 26: 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Nick. 2006. Selective Attention and Transfer Phenomena in L2 Acquisition: Contingency, Cue Competition, Salience, Interference, Overshadowing, Blocking, and Perceptual Learning. Applied Linguistics 27: 164–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Nick. 2017. Salience. In The Changing English Language. Edited by Marianne Hundt, Simone E. Pfenninger and Sandra Mollin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ellis, Nick. 2019. Essentials of a Theory of Language Cognition. The Modern Language Journal 103: 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Nick, and Nuria Sagarra. 2011. Learned Attention in Adult Language Acquisition: A Replication and Generalization Study and Meta-analysis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 33: 589–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, Andie. 2017. Assigning Grammatical Gender to Novel Nouns in L1 and L2 Spanish. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Faretta-Stutenberg, Mandy, and Kara Morgan-Short. 2018. The interplay of individual differences and context of learning in behavioral and neurocognitive second language development. Second Language Research 34: 67–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, Rebecca. 2010. Age of Acquisition and Proficiency as Factors in Language Production: Agreement in Bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 13: 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, Rebecca. 2011. Integrated Knowledge of Agreement in Early and Late English–Spanish Bilinguals. Applied Psycholinguistics 32: 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, Hannah. 2015. Person and Number Asymmetries in the Acquisition of Spanish Agreement and Object Clitics. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Somerville: Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franck, Julie, Gabriella Vigliocco, and Janet Nicol. 2002. Subject–verb Agreement Errors in French and English: The Role of Syntactic Hierarchy. Language and Cognitive Processes 17: 371–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gass, Susan, Ildikó Svetics, and Sarah Lemelin. 2003. Differential Effects of Attention. Language Learning 53: 497–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschneider, Jennifer M., and Robert M. DeKeyser. 2001. Explaining the ‘Natural Order of L2 Morpheme Acquisition’ in English: A Meta-Analysis of Multiple Determinants. Language Learning 51: 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, Gisela. 1995. Syntax and Morphology in Language Attrition: A Study of Five Bilingual Expatriate Swedes. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 5: 153–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1994. Some Key Features of Distributed Morphology. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 21: 88. [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne, Joshua K., Joshua B. Tenenbaum, and Steven Pinker. 2018. A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers. Cognition 177: 263–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartsuiker, Robert J., and Pashiera N. Barkhuysen. 2006. Language Production and Working Memory: The Case of Subject–verb Agreement. Language and Cognitive Processes 21: 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Roger. 2009. Statistical learning and innate knowledge in the development of second language proficiency: Evidence from the acquisition of gender concord. In Issues in Second Language Proficiency. Edited by Alessandro G. Benati. London: Continuum, pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Haznedar, Belma, and Bonnie D. Schwartz. 1997. Are there optional infinitives in child L2 acquisition. In Proceedings of the 21st annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, vol. 21, pp. 257–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Arturo E. 2013. The Bilingual Brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Arturo E., Jean P. Bodet, III, Kevin Gehm, and Shutian Shen. 2021. What Does a Critical Period for Second Language Acquisition Mean?: Reflections on Hartshorne et al. (2018). Cognition 206: 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, Arturo E., Juliane Hofmann, and Sonja A. Kotz. 2007. Age of Acquisition Modulates Neural Activity for Both Regular and Irregular Syntactic Functions. NeuroImage 36: 912–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopp, Holger. 2013. The Development of L2 Morphology. Second Language Research 29: 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]