Examining Pedagogical Translanguaging: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What characterizes empirical studies on translanguaging in terms of their context (educational settings, geography, participants, languages), research objectives, and methodology?

- According to the analysed corpus of studies, what are the factors enabling and constraining classroom application of translanguaging?

- Based on the analysed corpus of studies, what specific avenues for future research on pedagogical translanguaging can be proposed?

2. Methodology

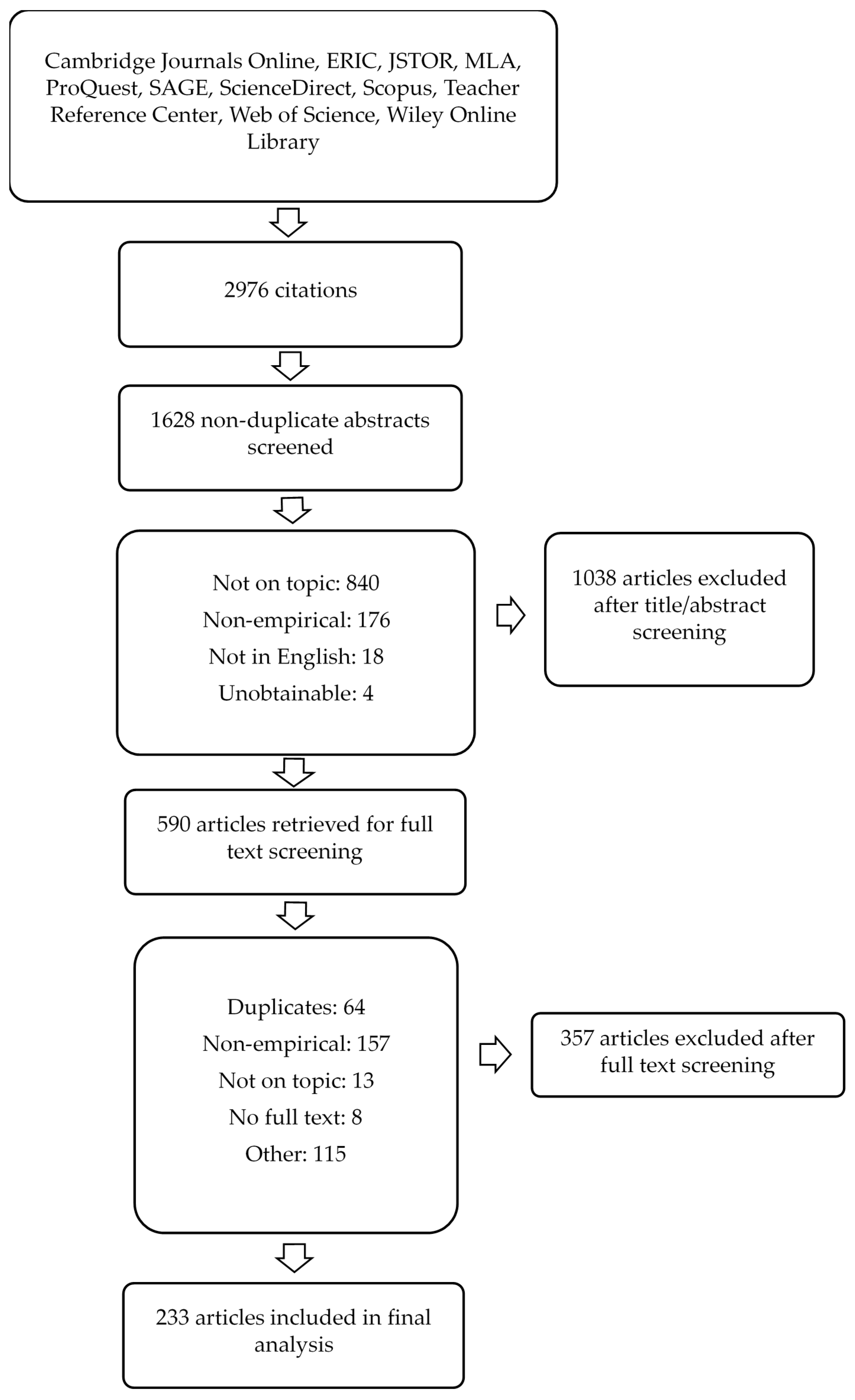

- 840 abstracts were excluded for being not on topic, that is, they presented research on translanguaging practices outside of formal educational settings, for instance, translanguaging in social media, in health care, in marketplaces, places of worship, and other social arenas;

- 18 abstracts were not in English;

- 4 abstracts could not be obtained even after requests were sent to other libraries;

- As a result of the initial title/abstract screening, 1038 abstracts were excluded, leaving 590 articles for full-text screening. During the full-text screening, more articles were excluded. These were:

- 64 duplicates;

- 157 non-empirical articles;

- 13 articles for being not on topic;

- 8 articles with no full-text available.

- Context: educational settings, geography, languages, participants;

- Research questions(s)/research objective(s);

- Methodology: quantitative, qualitative, mixed;

- Method(s) of data collection;

- Findings;

- Future avenues.

3. Results

3.1. What Characterizes Empirical Studies on Translanguaging in Terms of Their Context (Educational Settings, Geography, Participants, Languages), Research Objectives, and Methodology?

- Complementary or heritage schools with mixed age groups of learners;

- CLIL classes at primary, secondary and upper-secondary levels;

- Dual language (DL) or bilingual classrooms at all levels of education;

- English as a medium of instruction (EMI) at tertiary level;

- Sheltered classes for newly arrived immigrants at primary, secondary and upper-secondary levels;

- Mainstream English classes with English being labelled as second (ESL), foreign (EFL), additional (EAL) or new language (ENL).

- Language use and functions of translanguaging practices in teacher-learner and peer interaction;

- Perceptions of translanguaging practices among teachers and/or learners, including teacher and learner beliefs about use of L1/home/minority languages in the classroom;

- Focus on the measurable effects of translanguaging on learners’ performance and language learning;

- Investigation of the way teachers’ language ideologies interact with teaching practices and thus influence students’ translanguaging;

- Mapping of existing language policies and exploring how these may shift from monolingual to multilingual as a consequence of translanguaging-based interventions;

- Examining the affordances of translanguaging-based approaches in relation to various assessments practices;

- Looking into the way translanguaging strategies may mediate learners’ emotional well-being, alleviate language learning anxiety, and reduce negative behaviours;

- Exploring the role of translanguaging pedagogies in co-construction of emergent bilingual students’ identities as well as in promoting social justice through equity in education;

- Investigating translanguaging as a pedagogical tool. For instance, how its use may improve students’ metalinguistic awareness, reading comprehension, oral skills, and vocabulary acquisition.

3.2. According to the Analyzed Corpus Studies, What Are the Factors Enabling and Constraining Classroom Application of Translanguaging?

3.2.1. Stakeholders

Viewing their students as successful bilinguals was essential in that, from the outset, students were not seen to have linguistic deficits, which could have resulted in the professors simply believing they would not be successful in the class based solely on their language proficiency and not on their understanding of course content.

it would be helpful for teachers to have an overall understanding of translanguaging, not only as a pedagogic strategy to support learning but also as a feature of natural bilingual discourse, which they and their students can employ according to the situational demands

This study shows that providing participants with exposure to theory and research on different language ideologies in the field, paired with a first-hand experience of a translanguaging space in an academic setting, facilitates future teachers’ willingness to engage and embrace the contradictions and complexities of their role(s) as bilingual teachers and the realities and demands of educating Mexican American/Latinx emergent bilingual students in the current socio-political climate.

translanguaging functioned as an important discursive tool that emergent bilingual teachers and students used to communicate across language differences in the beginner ESL classes. In spite of its apparent utility, however, it existed within an unhospitable ecology of policies, practices, ideologies, and relationships, which tempered its pedagogical and interpersonal power.

We find that teachers apply the language resources at their disposal with some skill to make learners engage with subject content. However, the institutional language ideologies that materialize in the school’s language policy and in testing regimes, turn such skilful language practices from an asset into a relative disadvantage. While aware that they are transgressing the principal’s language policy as well as knowing that their students are struggling with monoglossic examination requirements, teachers continue to translanguage for the pedagogic advantages this brings, despite the rigid, separatist language ideologies that inform school management.

There is rhetorical celebration of multilingualism in the policy documents and this is reflected in the interviewees favourable attitudes towards multilingualism themselves. However; at the same time because of the lack of positive engagement and encouragement at the policy level there is no real culture or widespread practice in schools of using languages as flexible resources that can be meaningfully deployed for learning and assessment purposes…

If we desire to build classrooms where children develop metalinguistic awareness that can serve their writing, then we must welcome family and community members, lift their ways with words for children to appreciate, and elevate the dynamic and ever-changing nature of languages as resources for writing.

3.2.2. Context

3.2.3. Activity Type

3.3. Based on the Analyzed Corpus of Studies, What Specific Avenues for Future Research on Pedagogical Translanguaging Can Be Proposed?

- More research on translanguaging in teacher education and continuous professional development of all teachers in order to facilitate sustainable translanguaging in praxis beyond a single intervention (e.g., Costley and Leung 2020; Deroo et al. 2020; Martínez et al. 2015);

- More ethnographic sociolinguistic studies to examine the role of translanguaging in the development of learners’ hybrid identities, language ideology, and language development (e.g., Abourehab and Azaz 2020; Axelrod 2017; Parmegiani 2014);

- More small-scale investigations of translanguaging practices to examine whether these are transferrable to other contexts (e.g., Adamson and Yamauchi 2020; Esquinca et al. 2014; Makalela 2015a);

- More research on how translanguaging works in mainstream English classes (e.g., Afitska 2020);

- More projects to influence policy makers and the discourse on translanguaging in ELT and language education in general (e.g., Aitken and Robinson 2020);

- More research focusing on the translanguaging practices and interliteracy skills of young emergent bilingual children as well as across the developmental spectrum (e.g., Axelrod and Cole 2018; Velasco and García 2014);

- More rigorous, longitudinal research in school settings where translanguaging pedagogies have been adopted to explore the long-term impact of these pedagogies (e.g., Back 2020; Mwinda and van der Walt 2015; Vaish and Subhan 2015);

- More studies involving Latinx and African Americans of different ages in DL classrooms across a variety of contexts (e.g., Bauer et al. 2016; Durán and Palmer 2013; Gort and Sembiante 2015; Palmer et al. 2014);

- More research on the role of parents, extended family, and community members in leaners’ language learning process in school context (e.g., Fang and Liu 2020);

- More research on translanguaging in assessment practices (e.g., Li and Luo 2017; Prilutskaya and Knoph 2020);

- More research on the effect of translanguaging on learning outcomes, including the relationship between leaners’ proficiency level and the effects of translanguaging on language learning (e.g., Mgijima and Makalela 2016; Makalela 2015b; Turnbull 2019).

4. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abourehab, Yousra, and Mahmoud Azaz. 2020. Pedagogical Translanguaging in Community/Heritage Arabic Language Learning. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 41: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, John, and Darlene Yamauchi. 2020. Translanguaging in the Japanese Tertiary Sector: Exploring Perceptions and Practices of English Medium Content and English Language Instructors. In Pedagogic and Instructional Perspectives in Language Education: The Context of Higher Education. Edited by Enisa Mede, Kenan Dikilitaş and Derin Atay. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Afitska, Oksana. 2020. Translanguaging in Diverse Multilingual Classrooms in England: Oasis or a Mirage? European Journal of Applied Linguistics and TEFL 9: 153–81. [Google Scholar]

- Aitken, Avril, and Loretta Robinson. 2020. “Walking in Two Worlds” in the Plurilingual Classroom: Learning from the Case of an Intergenerational Project. In Plurilingual Pedagogies. Educational Linguistics. Edited by Sunny Man Chu Lau and Saskia Van Viegen. Cham: Springer, vol. 42, pp. 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, Elaine C. 2017. Re-Examining Teacher Translanguaging: An Ecological Perspective. Bilingual Research Journal 40: 116–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, Elena, April S. Salerno, and Amanda K. Kibler. 2020. “No, Professor, That Is Not True”: First Attempts at Introducing Translanguaging to Pre–Service Teachers. Educational Linguistics 45: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascenzi-Moren, Laura, Sarah Hesson, and Kate Menken. 2016. School Leadership along the Trajectory from Monolingual to Multilingual. Language and Education 30: 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, Ysaaca. 2017. “Ganchulinas” and “Rainbowli” Colors: Young Multilingual Children Play with Language in Head Start Classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal 45: 103–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, Ysaaca, and Mikel W. Cole. 2018. “The Pumpkins Are Coming…Vienen Las Calabazas…That Sounds Funny”: Translanguaging Practices of Young Emergent Bilinguals. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 18: 129–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, Michele. 2020. “It Is a Village”: Translanguaging Pedagogies and Collective Responsibility in a Rural School District. TESOL Quarterly: A Journal for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages and of Standard English as a Second Dialect 54: 900–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, Felix. 2018. Translanguaging and English-African Language Mother Tongues as Linguistic Dispensation in Teaching and Learning in a Black Township School in Cape Town. Current Issues in Language Planning 19: 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Eurydice Bouchereau, Vivian Presiado, and Soria Colomer. 2016. Writing through Partnership: Fostering Translanguaging in Children Who Are Emergent Bilinguals. Journal of Literacy Research 49: 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiler, Ingrid R. 2021. Marked and Unmarked Translanguaging in Accelerated, Mainstream, and Sheltered English Classrooms. Multilingua 40: 107–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, Blanca. 2019. To Switch or Not to Switch: Bilingual Preservice Teachers and Translanguaging in Teaching and Learning. TESOL Journal 10: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canagarajah, Suresh. 2011. Codemeshing in Academic Writing: Identifying Teachable Strategies of Translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal 95: 401–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Kevin S., Alissia de Vries, and Anyeliz Pagán Muñoz. 2020. Future Doctors in Training: Translanguaging in an Evolution Course. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 18: 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstens, Adelia. 2016. Translanguaging as a Vehicle for L2 Acquisition and L1 Development: Students’ Perceptions. Language Matters 47: 203–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, Jasone. 2017. Translanguaging in School Contexts: International Perspectives. Journal of Language, Identity & Education 16: 193–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, Jasone, and Durk Gorter. 2017. Minority Languages and Sustainable Translanguaging: Threat or Opportunity? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 38: 901–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, Jasone, and Alaitz Santos. 2020. Implementing Pedagogical Translanguaging in Trilingual Schools. System 92: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charamba, Erasmos. 2020a. Translanguaging: Developing Scientific Scholarship in a Multilingual Classroom. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 41: 655–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charamba, Erasmos. 2020b. Translanguaging in a Multilingual Class: A Study of the Relation between Students’ Languages and Epistemological Access in Science. International Journal of Science Education 42: 1779–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copland, Fiona, and Angela Creese. 2015. Linguistic Ethnography: Collecting, Analysing and Presenting Data. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Costley, Tracey, and Constant Leung. 2020. Putting Translanguaging into Practice: A View from England. System 92: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creese, Angela, and Adrian Blackledge. 2010. Translanguaging in the Bilingual Classroom: A Pedagogy for Learning and Teaching? The Modern Language Journal 94: 103–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Jim. 2019. The Emergence of Translanguaging Pedagogy: A Dialogue between Theory and Practice. Journal of Multilingual Education Research 9: 19–36. Available online: https://research.library.fordham.edu/jmer/vol9/iss1/13 (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Deroo, Matthew R., Christina M. Ponzio, and Peter I. De Costa. 2020. Reenvisioning Second Language Teacher Education through Translanguaging Praxis. In Envisioning TESOL Through a Translanguaging Lens. Educational Linguistics. Edited by Zhongfeng Tian, Laila Aghai, Peter Sayer and Jamie L. Schissel. Cham: Springer, vol. 45, pp. 111–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, Leah, and Deborah Palmer. 2013. Pluralist Discourses of Bilingualism and Translanguaging Talk in Classrooms. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 14: 367–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquinca, Alberto, Blanca Araujo, and María Teresa de la Piedra. 2014. Meaning Making and Translanguaging in a Two-Way Dual-Language Program on the U.S.-Mexico Border. Bilingual Research Journal 37: 164–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Fan, and Yang Liu. 2020. “Using All English Is Not Always Meaningful”: Stakeholders’ Perspectives on the Use of and Attitudes Towards Translanguaging at a Chinese University. Lingua: International Review of General Linguistics 247: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, Angelica. 2020. Pedagogical Translanguaging in a Multilingual English Program in Canada: Student and Teacher Perspectives of Challenges. System 92: 1–10. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0346251x20302748 (accessed on 15 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Ganuza, Natalia, and Christina Hedman. 2017. Ideology Versus Practice: Is There a Space for Pedagogical Translanguaging in Mother Tongue Instruction? In New Perspectives on Translanguaging and Education. Edited by BethAnne Paulsrud, Jenny Rosén, Boglárka Straszer and Aasa Wedin. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 208–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Ofelia. 2012. Theorizing Translanguaging for Educators. In Translanguaging: A CUNY-NYSIEB Guide for Educators. Edited by Christina Celic and Kate Seltzer. New York: The Graduate Center, The City University of New York. Available online: https://www.cuny-nysieb.org/translanguaging-resources/translanguaging-guides/ (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Gort, Mileidis, and Sabrina Francesca Sembiante. 2015. Navigating Hybridized Language Learning Spaces through Translanguaging Pedagogy: Dual Language Preschool Teachers’ Languaging Practices in Support of Emergent Bilingual Children’s Performance of Academic Discourse. International Multilingual Research Journal 9: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorter, Durk, and Eli Arocena. 2020. Teachers’ Beliefs about Multilingualism in a Course on Translanguaging. System 92: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gynne, Annaliina. 2019. “English or Swedish Please, No Dari!”–(Trans)Languaging and Language Policing in Upper Secondary School’s Language Introduction Programme in Sweden. Classroom Discourse 10: 347–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen-Thomas, Holly, Mary A. Stewart, Patricia Flint, and Tamra Dollar. 2020. Co-Learning in the High School English Class through Translanguaging: Emergent Bilingual Newcomers and Monolingual Teachers. Journal of Language, Identity and Education 20: 151–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufhold, Kathrin. 2018. Creating Translanguaging Spaces in Students’ Academic Writing Practices. Linguistics and Education 45: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Lara S., and Mastin Prinsloo. 2016. Translanguaging in a Township Primary School: Policy and Practice. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 34: 347–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Nora W. 2019. Teachers’ Translanguaging Practices and “Safe Spaces” for Adolescent Newcomers: Toward Alternative Visions. Bilingual Research Journal 42: 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonet, Oihana, Jasone Cenoz, and Durk Gorter. 2017. Challenging Minority Language Isolation: Translanguaging in a Trilingual School in the Basque Country. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education 16: 216–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Gwyn, Bryn Jones, and Colin Baker. 2012. Translanguaging: Developing its Conceptualization and Contextualization. Education Research and Evaluation 18: 655–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Shuzhan, and Wenjing Luo. 2017. Creating a Translanguaging Space for High School Emergent Bilinguals. CATESOL Journal 29: 139–62. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1164350.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Liu, Jiajia Eve, Yuen Yi Lo, and Angel M. Y. Lin. 2020. Translanguaging Pedagogy in Teaching English for Academic Purposes: Researcher-Teacher Collaboration as a Professional Development Model. System 92: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makalela, Leketi. 2015a. Breaking African Language Boundaries: Student Teachers Reflections on Translanguaging Practices. Language Matters 46: 275–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makalela, Leketi. 2015b. Moving out of Linguistic Boxes: The Effects of Translanguaging Strategies for Multilingual Classrooms. Language and Education 29: 200–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Beltrán, Melinda. 2014. “What Do You Want to Say?” How Adolescents Use Translanguaging to Expand Learning Opportunities. International Multilingual Research Journal 8: 208–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Ramón Antonio, Michiko Hikida, and Leah Durán. 2015. Unpacking Ideologies of Linguistic Purism: How Dual Language Teachers Make Sense of Everyday Translanguaging. International Multilingual Research Journal 9: 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Anna. 2020. What Does Translanguaging-for-Equity Really Involve? An Interactional Analysis of a 9th Grade English Class. Applied Linguistics Review. Available online: https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/mla-international-bibliography (accessed on 12 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Mgijima, Vukile Desmond, and Leketi Makalela. 2016. The Effects of Translanguaging on the Bi-Literate Inferencing Strategies of Fourth Grade Learners. Perspectives in Education 34: 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwinda, Nangura, and Christa van der Walt. 2015. From ‘English-Only’ to Translanguaging Strategies: Exploring Possibilities. Per Linguam-a Journal of Language Learning 31: 100–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikula, Tarja, and Pat Moore. 2019. Exploring Translanguaging in CLIL. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22: 237–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidire, Margaret F., and Sameera Ayob. 2020. The Utilisation of Translanguaging for Learning and Teaching in Multilingual Primary Classrooms. Multilingua. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia García, and Wallis Reid. 2015. Clarifying Translanguaging and Deconstructing Named Languages: A Perspective from Linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review 6: 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, Deborah K., Ramón Antontio Martínez, Suzanne G. Mateus, and Kathryn Henderson. 2014. Reframing the Debate on Language Separation: Toward a Vision for Translanguaging Pedagogies in the Dual Language Classroom. Modern Language Journal 98: 757–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmegiani, Andrea. 2014. Bridging Literacy Practices through Storytelling, Translanguaging, and an Ethnographic Partnership: A Case Study of Dominican Students at Bronx Community College. Journal of Basic Writing 33: 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poza, Luis. 2017. Translanguaging: Definitions, Implications, and Further Needs in Burgeoning Inquiry. Berkeley Review of Education 6: 101–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, Josh, and Blake Turnbull. 2018. The Role of Translanguaging in the Multilingual Turn: Driving Philosophical and Conceptual Renewal in Language Education. E-JournALL, EuroAmerican Journal of Applied Linguistics and Languages 5: 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilutskaya, Marina, and Rebecca Knoph. 2020. Research on Three L2 Writing Conditions: Students’ Perceptions and Use of Background Languages When Writing in English. Cogent Education 7: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramchander, Manduth. 2020. Using Group Work to Harness Students’ Multilinguistic Competencies for a Better Understanding of Assignment Questions. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning 8: 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, Blake. 2019. Translanguaging in the Planning of Academic and Creative Writing: A Case of Adult Japanese EFL Learners. Bilingual Research Journal 42: 232–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaish, Viniti, and Aidil Subhan. 2015. Translanguaging in a Reading Class. International Journal of Multilingualism 12: 338–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, Patricia, and Ofelia García. 2014. Translanguaging and the Writing of Bilingual Learners. Bilingual Research Journal 37: 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Cen. 1994. Arfarniad o Ddulliau Dysgu ac Addysgu yng Nghyd-Destun Addysg Uwchradd Ddwyieithog [An Evaluation of Teaching and Learning Methods in the Context of Bilingual Secondary Education]. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Wales, Bangor, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Cen. 1996. Second Education: Teaching in the Bilingual Situation. In The Language Policy: Taking Stock. Edited by Cen Williams, Gwyn Lewis and Colin Baker. Llangefni: CAI, pp. 39–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yuvayapan, Fatma. 2019. Translanguaging in EFL Classrooms: Teachers’ Perceptions and Practices. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies 15: 678–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, Angie, and Tasha Tropp Laman. 2016. “I Write to Show How Beautiful My Languages Are”: Translingual Writing Instruction in English-Dominant Classrooms. Language Arts 93: 366–78. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44809858 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

| Database | Search Results |

|---|---|

| Cambridge Journals Online | 32 |

| ERIC | 552 |

| JSTOR | 108 |

| MLA | 119 |

| ProQuest | 315 |

| SAGE | 223 |

| ScienceDirect | 249 |

| Scopus | 797 |

| Teacher Reference Center | 56 |

| Web of Science | 398 |

| Wiley Online Library | 127 |

| Total | 2976 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prilutskaya, M. Examining Pedagogical Translanguaging: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Languages 2021, 6, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040180

Prilutskaya M. Examining Pedagogical Translanguaging: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Languages. 2021; 6(4):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040180

Chicago/Turabian StylePrilutskaya, Marina. 2021. "Examining Pedagogical Translanguaging: A Systematic Review of the Literature" Languages 6, no. 4: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040180

APA StylePrilutskaya, M. (2021). Examining Pedagogical Translanguaging: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Languages, 6(4), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040180