Collaborative Multimodal Writing via Google Docs: Perceptions of French FL Learners

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Empirical Research

3.1. Learners’ Perceptions on Collaborative Writing

3.2. Learners’ Perceptions on Multimodal Writing

- How do French FL learners view the benefits and challenges of collaborative multimodal writing?

- What factors do French FL learners perceive as mediating their writing processes in the collaborative multimodal writing task?

4. Methods

4.1. Context and Participants

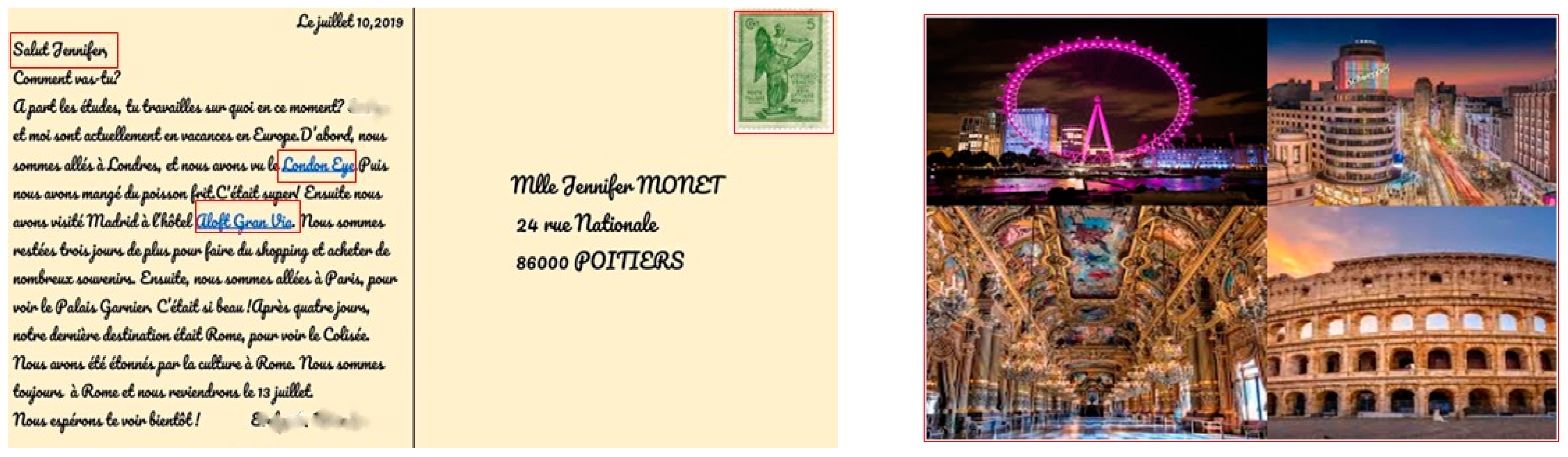

4.2. Task Description

4.3. Description of Data Sources

4.4. Data Collection and Instructional Procedures

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Results

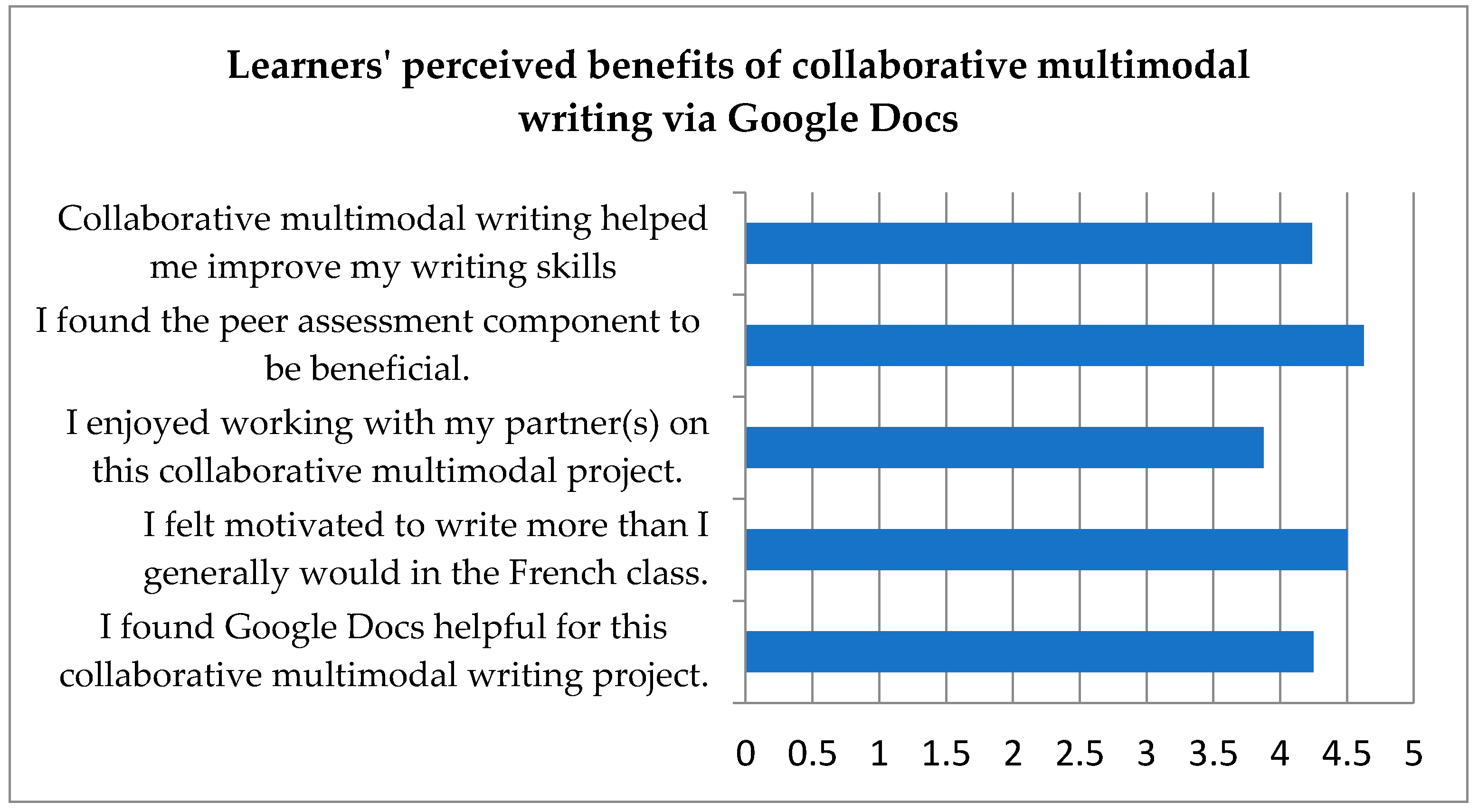

5.1. Perceived Benefits

To be honest, I felt a little nervous in the beginning because I usually prefer to do my work alone and don’t really like it when other people view my work or critique it. […] But after working with Eva for over a month, I think that I have grown a lot and I’m a lot more open to the idea of working with other people. I also really liked getting feedback from other people and seeing their postcards was fun; I ended up spending more time on ours because of that.(Interview, 8 December 2020)

I think ah … talking things over with Christine and looking for new ways to convey our message on the postcard was quite interesting. […] because I’ve never done this type of work before … like um … normally you don’t get to do that in my Spanish class. So being able to add like pictures and thinking about even small things like color and font was sort of new and exciting for me … and yeah I think that all that stuff helps to make the postcard even better.(Interview, 9 December 2020)

Like … how we all already know what a postcard kinda looks like in English … like there’s the the stamp (of course), the address, the date and all that stuff. And so when I saw the examples in French it was way easier to understand because they all follow the same pattern even though the French ones always seem so formal. [laughs]

When I compared our postcard with everybody else’s, it gave me a different perspective … Like I realized that ours needed to be developed more. So I left some comments for Mary-Ann on what needed to be changed in our introduction. That part was very helpful because if we didn’t do that I don’t think we would have made any progress.(Interview, 8 December 2020)

5.2. Perceived Challenges

I don’t think ah … we all contributed equally and that was just because … um most of the time I didn’t know what was up with Brian and there was a time I even emailed him and he didn’t get back to me for three days and I was kinda like dude I can’t wait any longer for you to do things so that part was really frustrating because we were all supposed to work on this together as a team.(Interview, 11 December 2020)

Yeah I think it was hard sometimes because … um … maybe I added something and then when I checked later it was not there anymore. But me […] before you erase something you have to ask first. I always comment before I delete or add something but I don’t think that everybody is like me.(Interview, 8 December 2020)

5.3. Mediating Factors

Using Google Docs was very helpful because it allowed us to work together while not looking at the same screen and also instead of working on it at fully at home, I think the fact that we did it face to face in the multimedia lab made it successful.

For me … um I would say that I was a bit unsure about how the project was going to go but after the first workshop I felt a lot better because everything we needed to know about the project was right there … uh like right from the get-go what me and Eva did, was to compare the example postcards that you showed us and decide what makes a postcard look good and what does not … that really helped us figure out how we wanted ours to look.

Normally you just do the work and then later you can go and check to see what grade you got … like after the fact. […] in this one we already knew what things we would be graded on before we even started so it was kinda different.

I feel like it is kind of difficult to be in a group with your friends. Like last semester, I was in a group with my roommate and she didn’t take the work serious […] she kept distracting us and making stupid jokes. So like working with Britney was cool because she was nice and she always did her part of the work.(Interview, 11 December 2020)

6. Discussion

7. Implications and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, Susan J., Sylvia G. Roch, and Roya Ayman. 2005. Communication Medium and Member Familiarity: The Effects on Decision Time, Accuracy, and Satisfaction. Small Group Research 36: 321–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Heather Willis. 2018. Redefining Writing in the Foreign Language Curriculum: Toward a Design Approach. Foreign Language Annals 51: 513–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, Nike, Lara Ducate, and Claudia Kost. 2012. Collaboration or Cooperation? Analyzing Group Dynamics and Revision Processes in Wikis. CALICO Journal 29: 431–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawarshi, Anis S., and Mary Jo Reiff. 2010. Genre: An Introduction to History, Theory, Research, and Pedagogy. West Lafayette: Parlor Press LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Belcher, Diane D. 2017. On Becoming Facilitators of Multimodal Composing and Digital Design. Journal of Second Language Writing 38: 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikowski, Dawn, and Ramyadarshanie Vithanage. 2016. Effects of Web-Based Collaborative Writing on Individual L2 Writing Development. Language Learning & Technology 20: 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, Jerome. 1985. Child’s Talk: Learning to Use Language. Child Language Teaching and Therapy 1: 111–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, Martha E. 2013. ‘I Am Proud That I Did It and It’s a Piece of Me’: Digital Storytelling in the Foreign Language Classroom. CALICO Journal 30: 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimasko, Tony, and Dong-shin Shin. 2017. Multimodal resemiotization and authorial agency in an L2 writing classroom. Written Communication 34: 387–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, Bill, and Mary Kalantzis. 2009. ‘Multiliteracies’: New Literacies, New Learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal 4: 164–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, Bill, and Mary Kalantzis. 2015. The Things You Do to Know: An Introduction to the Pedagogy of Multiliteracies. In A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Learning by Design. Edited by Bill Cope and Mary Kalantzis. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Donato, Richard. 1988. Beyond Group: A Psycholinguistic Rationale for Collective Activity in Second Language Learning. Ann Arbor: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Available online: https://search.proquest.com/docview/303711939?pq-origsite=primo (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Donato, Richard. 1994. Collective Scaffolding in Second Language Learning. In Vygotskian Approaches to Second Language Research. Edited by James P. Lantolf and Gabriela Appel. Norwood: Ablex Publishing Corporation, pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Donato, Richard. 2004. 13. Aspects of Collaboration in Pedagogical Discourse. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 24: 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducate, Lara C., Lara Lomicka Anderson, and Nina Moreno. 2011. Wading Through the World of Wikis: An Analysis of Three Wiki Projects. Foreign Language Annals 44: 495–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzekoe, Richmond. 2017. Computer-Based Multimodal Composing Activities, Self-Revision, and L2 Acquisition through Writing. Language Learning & Technology 21: 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ede, Lisa S., and Andrea A. Lunsford. 1990. Singular Texts/Plural Authors Perspectives on Collaborative Writing. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elola, Idoia, and Ana Oskoz. 2010. Collaborative Writing: Fostering Foreign Language and Writing Conventions Development. Language Learning & Technology 14: 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Elola, Idoia, and Ana Oskoz. 2017. Writing with 21st Century Social Tools in the L2 Classroom: New Literacies, Genres, and Writing Practices. Journal of Second Language Writing 36: 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilje, Øystein. 2010. Multimodal redesign in filmmaking practices: An inquiry of young filmmakers’ deployment of semiotic tools in their filmmaking practice. Written Communication 27: 494–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, Christoph A. 2014. Embedding Digital Literacies in English Language Teaching: Students’ Digital Video Projects as Multimodal Ensembles. TESOL Quarterly: A Journal for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages and of Standard English as a Second Dialect 48: 655–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, Christoph A., and Lindsay Miller. 2011. Fostering Learner Autonomy in English for Science: A Collaborative Digital Video Project in a Technological Learning Environment. Language Learning 15: 68–86. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1978. Language as a Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning. Baltimore: University Park Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hron, Aemilian, and Helmut-Felix Friedrich. 2003. A Review of Web-Based Collaborative Learning: Factors beyond Technology. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 19: 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Hsiu-Ting, Yi-Ching Jean Chiu, and Hui-Chin Yeh. 2013. Multimodal Assessment of and for Learning: A Theory-Driven Design Rubric. British Journal of Educational Technology 44: 400–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, Ken. 2007. Genre Pedagogy: Language, Literacy and L2 Writing Instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing; Erratum in Teacher Educators: Exploring Writing Teacher Education 16: 148–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, Jeroen, Gijsbert Erkens, Paul A. Kirschner, and Gellof Kanselaar. 2009. Influence of group member familiarity on online collaborative learning. Computers in Human Behavior 25: 161–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Lianjiang, and Jasmine Luk. 2016. Multimodal Composing as a Learning Activity in English Classrooms: Inquiring into the Sources of Its Motivational Capacity. System 59: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Lianjiang, and Jinyuan Gao. 2020. Fostering EFL Learners’ Digital Empathy through Multimodal Composing. RELC Journal 51: 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Lianjiang, and Wei Ren. 2020. Digital Multimodal Composing in L2 Learning: Ideologies and Impact. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Lianjiang, Miaoyan Yang, and Shulin Yu. 2020. Chinese Ethnic Minority Students’ Investment in English Learning Empowered by Digital Multimodal Composing. TESOL Quarterly 54: 954–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Lianjiang. 2018. Digital Multimodal Composing and Investment Change in Learners’ Writing in English as a Foreign Language. Journal of Second Language Writing 40: 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, Greg, and Dawn Bikowski. 2010. Developing Collaborative Autonomous Learning Abilities in Computer Mediated Language Learning: Attention to Meaning among Students in Wiki Space. Computer Assisted Language Learning 23: 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, Greg, Dawn Bikowski, and Jordan Boggs. 2012. Collaborative Writing among Second Language Learners in Academic Web-Based Projects. Language Learning & Technology 16: 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Koelzer, Marie-Louise. 2017. Is It Just “Very Fun?” Or Does It Actually Help?: Digital Storytelling in L2 Academic Writing. Master’s thesis, The University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/docview/1906291982/abstract/E2AAC1E8D9EB44B0PQ/13 (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Kost, Claudia. 2011. Investigating Writing Strategies and Revision Behavior in Collaborative Wiki Projects. CALICO Journal 28: 606–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2001. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunther R. 2003. Literacy in the New Media Age. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunther R. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunther R., and Carey Jewitt. 2003. Introduction. In Multimodal Literacy. Edited by Carey Jewitt and Gunther R. Kress. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, Wan Shun Eva. 2000. L2 Literacy and the Design of the Self: A Case Study of a Teenager Writing on the Internet. TESOL Quarterly 34: 457–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Lina. 2010. Exploring Wiki-Mediated Collaborative Writing: A Case Study in an Elementary Spanish Course. CALICO Journal 27: 260–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Sy-Ying, Yi-Hsuan Gloria Lo, and Ting-Chin Chin. 2019. Practicing Multiliteracies to Enhance EFL Learners’ Meaning Making Process and Language Development: A Multimodal Problem-Based Approach. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leont’ev, Alekseĭ Nikolaevich. 1978. Activity, Consciousness, and Personality. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Mimi. 2020. Multimodal Pedagogy in TESOL Teacher Education: Students’ Perspectives. System 94: 102337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Mimi, and Deoksoon Kim. 2016. One Wiki, Two Groups: Dynamic Interactions across ESL Collaborative Writing Tasks. Journal of Second Language Writing 31: 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Mimi, and Neomy Storch. 2017. Second Language Writing in the Age of CMC: Affordances, Multimodality, and Collaboration. Journal of Second Language Writing 36: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Mimi, and Wei Zhu. 2013. Patterns of Computer-Mediated Interaction in Small Writing Groups Using Wikis. Computer Assisted Language Learning 26: 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, Andreas. 2008. Wikis: A Collective Approach to Language Production. ReCALL: The Journal of Eurocall 20: 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manchón, Rosa M. 2017. The Potential Impact of Multimodal Composition on Language Learning. Journal of Second Language Writing 38: 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqueda, Cheryl Hurst. 2020. Heritage and L2 Writing Processes in Individual and Collaborative Digital Storytelling. Ph.D dissertation, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, Paul K. 2003. Second Language Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Situated Historical Perspectives. In Exploring the Dynamics of Second Language Writing. Edited by Kroll Barbara. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Suzanne M. 2010. Toward a multimodal literacy pedagogy: Digital video composing as 21st century literacy. In Literacies, the Arts, and Multimodality. Edited by Peggy Albers and Jennifer Sanders. Urbana-Champaign: National Council of Teachers of English, pp. 254–81. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Mark Evan. 2006. Mode, Meaning, and Synaesthesia in Multimedia L2 Writing. Language Learning 2: 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Mark Evan, and Glynda A. Hull. 2008. Self-presentation through multimedia A Bakhtinian perspective on digital. In Digital Storytelling, Mediatized Stories: Self-Representations in New Media. Edited by Knut Lundby. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 123–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, Amy Snyder. 2000. Re-thinking interaction in SLA: Developmentally appropriate assistance in the zone of proximal development and the acquisition of L2 grammar. In Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning. Edited by James P. Lantolf. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Oskoz, Ana, and Idoia Elola. 2014. Integrating digital stories in the writing class: Towards a 21st century literacy. In Digital Literacies in Foreign Language Education: Research, Perspectives, and Best Practices. Edited by Janel Pettes Guikema and Lawrence Williams. San Marcos: CALICO, pp. 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- Oskoz, Ana, and Idoia Elola. 2016. Digital Stories: Bringing Multimodal Texts to the Spanish Writing Classroom. ReCALL: The Journal of Eurocal Cambridge 28: 326–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskoz, Ana, and Idoia Elola. 2019. Digital L2 Writing Literacies. London: Equinox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paesani, Kate A., Heather W. Allen, and Beatrice Dupuy. 2016. A Multiliteracies Framework for Collegiate Foreign Language Teaching. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Prior, Paul. 2006. A sociocultural theory of writing. In Handbook of Writing Research. Edited by Charles A. MacArthur, Steve Graham and Jill Fitzgerald. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Purdy, James P. 2014. What Can Design Thinking Offer Writing Studies? College Composition and Communication 65: 612–41. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Weiguo. 2017. For L2 Writers, It Is Always the Problem of the Language. Journal of Second Language Writing 38: 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichelt, Melinda, Natalie Lefkowitz, Carol Rinnert, and Jean Marie Schultz. 2012. Key issues in foreign language writing. Foreign Language Annals 45: 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, Johnny. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Dong-shin, Tony Cimasko, and Youngjoo Yi. 2020. Development of Metalanguage for Multimodal Composing: A Case Study of an L2 Writer’s Design of Multimedia Texts. Journal of Second Language Writing 47: 100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Blaine E. 2017. Composing across Modes: A Comparative Analysis of Adolescents’ Multimodal Composing Processes. Learning, Media and Technology 42: 259–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Blaine E. 2019. Collaborative Multimodal Composing: Tracing the Unique Partnerships of Three Pairs of Adolescents Composing across Three Digital Projects. Literacy 53: 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, Blaine E., Mark B. Pacheco, and Mariia Khorosheva. 2020. Emergent Bilingual Students and Digital Multimodal Composition: A Systematic Review of Research in Secondary Classrooms. Reading Research Quarterly 56: 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Pippa. 2008. Multimodal instructional practices. In Handbook of Research on New Literacies. Edited by Julie Coiro, Michele Knobel, Colin Lankshear and Donald J. Leu. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 871–98. [Google Scholar]

- Storch, Neomy. 2005. Collaborative writing: Product, process, and students’ reflections. Journal of Second Language Writing 14: 153–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, Neomy. 2011. Collaborative writing in L2 contexts: Processes, outcomes, and future directions. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 31: 275–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, Neomy. 2013. Collaborative Writing in L2 Classrooms. Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters, vol. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Storch, Neomy. 2019. Collaborative Writing. Language Teaching 52: 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, Carola. 2014. Affordances of Web 2.0 Technologies for Collaborative Advanced Writing in a Foreign Language. CALICO Journal 31: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, Merrill, and Sharon Lapkin. 1998. Interaction and Second Language Learning: Two Adolescent French Immersion Students Working Together. The Modern Language Journal 82: 320–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardy, Christine M. 2005. ‘It’s like a Story’: Rhetorical Knowledge Development in Advanced Academic Literacy. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, Advanced Academic Literacy 4: 325–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The New London Group, Courtney Cazden, Bill Cope, Norman Fairclough, Jim Gee, Mary Kalantzis, Gunther Kress, Allan Luke, Carmen Luke, Sarah Michaels, and et al. 1996. A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures. Harvard Educational Review 66: 60–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimbur, John. 1994. Taking the Social Turn: Teaching Writing Post-Process. Edited by Patricia Bizzell, C. H. Knoblauch, Lil Brannon and Kurt Spellmeyer. Nashville: College Composition and Communication, vol. 45, pp. 108–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandommele, Goedele, Kris Van den Branden, Koen Van Gorp, and Sven De Maeyer. 2017. In-school and out-of-school multimodal writing as an L2 writing resource for beginner learners of Dutch. Journal of Second Language Writing 36: 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lier, Leo. 1996. Interaction in the Language Curriculum: Awareness, Autonomy and Authenticity. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova, Polina. 2011. Digital Storytelling in ESL Instruction: Identity Negotiation through a Pedagogy of Multiliteracies. Unpublished. Doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/docview/897541543/abstract/19F145FC07414DDCPQ/96 (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Vinogradova, Polina. 2014. Vinogradova, Polina. Digital stories in heritage language education: Empowering heritage language learners through a pedagogy of multiliteracies. In Handbook of Heritage, Community, and Native American Languages in the United States. London: Routledge, pp. 328–37. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, Lev Semenovich. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, Lev Semenovich. 1981. The genesis of mental functions. In The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology. Edited by James V. Wertsch. Armonk: Sharpe, pp. 144–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yu-Chun. 2015. Promoting Collaborative Writing through Wikis: A New Approach for Advancing Innovative and Active Learning in an ESP Context. Computer Assisted Language Learning 28: 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertsch, James V. 1988. Vygotsky and the Social Formation of Mind. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/tamu/detail.action?docID=3300753 (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Wood, David, Jerome S. Bruner, and Gail Ross. 1976. The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving*. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 17: 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Yu-Feng. 2012. Multimodal Composing in Digital Storytelling. Computers and Composition, New Literacy Narratives: Stories about Reading and Writing in a Digital Age 29: 221–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Hui-Chin. 2018. Exploring the Perceived Benefits of the Process of Multimodal Video Making in Developing Multiliteracies. Language Learning & Technology 22: 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Youngjoo, and Tuba Angay-Crowder. 2016. Multimodal Pedagogies for Teacher Education in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly 50: 988–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Youngjoo, Dong-shin Shin, and Tony Cimasko. 2020. Special Issue: Multimodal Composing in Multilingual Learning and Teaching Contexts. Journal of Second Language Writing 47: 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğitoğlu, Nur, and Melinda Reichelt. 2019. L2 Writing in Non-English Languages: Toward a Fuller Understanding of L2 Writing. L2 Writing Beyond English. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.21832/9781788923132-003/html (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Yim, Soobin, Dakuo Wang, Judith Olson, Viet Vu, and Mark Warschauer. 2017. Synchronous Collaborative Writing in the Classroom: Undergraduates’ Collaboration Practices and Their Impact on Writing Style, Quality, and Quantity. Paper presented at CSCW ’17,2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, USA, February 25–March 1; New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 468–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zapata, Gabriela C., and Manel Lacorte, eds. 2017. Multiliteracies Pedagogy and Language Learning: Teaching Spanish to Heritage Speakers. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Meixiu, Akoto Miriam, and Li Mimi. 2021. Digital Multimodal Composing in Post-secondary L2 Settings: A Review of the Empirical Landscape. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name 1 | Age | Gender | Major | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Britney | 2020 | Female | Theatre |

| Eva | 20 | Female | Art | |

| Group 2 | Joshua | 21 | Male | Music |

| Christine | 20 | Female | English | |

| Brian | 20 | Male | History/Political Science | |

| Group 3 | Alejandro | 23 | Male | Music |

| Mary-Ann | 21 | Female | Music/Theatre |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akoto, M. Collaborative Multimodal Writing via Google Docs: Perceptions of French FL Learners. Languages 2021, 6, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030140

Akoto M. Collaborative Multimodal Writing via Google Docs: Perceptions of French FL Learners. Languages. 2021; 6(3):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030140

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkoto, Miriam. 2021. "Collaborative Multimodal Writing via Google Docs: Perceptions of French FL Learners" Languages 6, no. 3: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030140

APA StyleAkoto, M. (2021). Collaborative Multimodal Writing via Google Docs: Perceptions of French FL Learners. Languages, 6(3), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030140