Strengthening Writing Voices and Identities: Creative Writing, Digital Tools and Artmaking for Spanish Heritage Courses

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Spanish 49H: An Advanced Online Spanish Heritage Course

SPAN49H and Digital Tools

3. Writing in SPAN 49H

3.1. Writing Assignments and Digital Tools

3.2. When Writing Meets (Digital) Artmaking

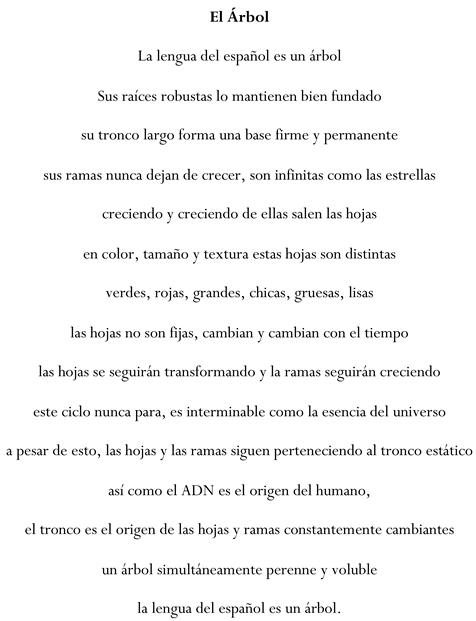

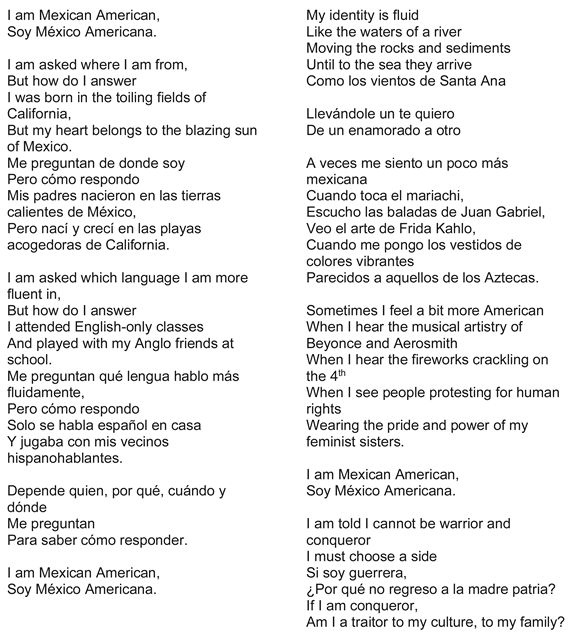

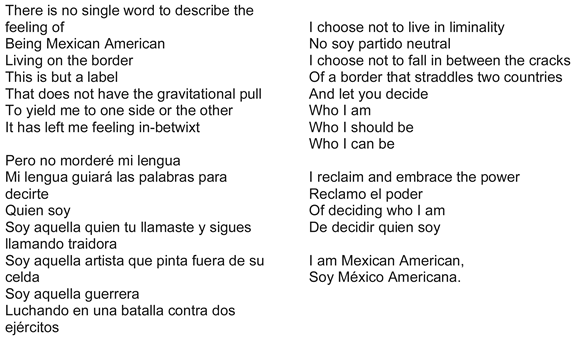

3.3. Poetry as a Creative Final Project

4. Analysis of Poems

- Finalmente, entendio Adrían que esto es lo maravilloso de este lenguaje de comunicación

- Talvez hablamos palabritas diferentes, y hablamos u oimos con confusión

- ¡Pero al fin del día, todavía se entiende la intención!

- ‘Finally, Adrian understood that this is the wonderful thing about this language of communication

- Maybe we say different little words, and we speak or hear with confusion

- But at the end of the day, the intention is still understood!’

- “I was born in the toiling fields of California

- But my heart belongs to the blazing sun of Mexico.

- Mis padres nacieron en las tierras calientes de México

- Pero nací y crecí en las playas acogedoras de California.”

- ‘My parents were born in the hot lands of Mexico

- But I was born in the welcoming beaches of California’

- Late el corazón como marimba

- Tradiciones de antigüedad

- La historia de mi familia es la mía

- Y eso no se me olvidará.

- ‘The heart beats like a marimba

- Traditions of antiquity

- My family’s story is mine

- And that I will not forget.’

5. Discussion

6. Final Remarks

- Interdisciplinary and humanities content that engages students with the richness and complexities of the history of the Spanish-speaking world and Latinx communities (Martínez and San Martín 2018; Parra 2016; Parra et al. 2018; Potowski 2012; Torres et al. 2017). As Parra (2021b, p. 61) explained elsewhere and the poems’ analysis suggests, such a curriculum enhances the possibilities of: (a) identifying with the narratives of Latinx authors; (b) expressing the plurality of their lived experiences; and (c) re-appropriating the past in order to better understand the present and project to the future (Lionnet 1989).

- Written, multimodal, and multimedia texts as models and digital technologies as resources for a myriad of meaning-making possibilities for students’ projects. As Jewitt (2008) proposed, multimodal and multimedia texts expand on traditional forms of literacies while providing models for multiple-literacies projects that build on stories based on and arising from young people’s lives and experiences and cultural forms of representation.

- A pedagogy of writing that centers on meaningful topics (Loureiro-Rodriguez 2013) and combines process and post-process approaches (Martínez 2005; Mrak 2020). The analyses of the poems and essays underscore, once more, the benefits of incorporating flexible definitions of “genre” as staged and goal-oriented (Fairclough 2003 Martínez 2005; Xerri 2012). The craft and reshaping of a text—academic and creative—have to do with purpose and audience (Kress 2010, p. 132), more than with the application of formulaic conventions.

- Poetry. Alone or combined with digital tools, poetry reading and interpretation, as well as its crafting, become a rich linguistic and learning experience (Durán 2015; Lima, forthcoming; Royster 2005; Xerri 2012). Poetry also allows for engaging with the performative dimension of the act of writing, fostering students’ awareness of: (a) the different locations they can take on as authors; (b) the effective and affective power their words can have to convey and project new understandings about the role of the Spanish language in their lives; and (c) the possibilities to imagine—and hopefully enact—reaching out to broader audiences and communities beyond the classroom. This awareness is a transformative learning experience that, at least in the four poems analyzed here, seems to have empowered students’ writing voices and identities.

- Creative assignments. The analysis of the four poems showed that creativity strengthened students’ writing voices within their own rhetorical spaces (Spicer-Escalante 2005, p. 244) while allowing them to connect with deep affective issues and questions of ethnolinguistic identity that were expressed in creative ways. It is important to note that just because assignments are creative does not mean that they are easy. Crafting a poem—or a digital image or video—implies important conceptual and linguistic challenges. However, students happily engaged and wrestled with them. As Jesús wrote in his essay: Debido a esta libertad creativa, el proceso de escribir este poema fue divertido y placentero[…]. Al mismo tiempo, aunque este proyecto fue vivificante, eso no quiere decir que fue fácil (‘Given the creative freedom, the process of writing this poem was fun and enjoyable[…]. At the same time, even when it was an energizing project, this does not mean that it was easy’). Carlos also wrote: […] decidí escribir un poema, una actividad que nunca hago ni siquiera cuando escribo en inglés y que siempre he querido probar (‘[…] I decided to write a poem, an activity that I have never done even in English but that I have always wanted to try’). He explains that writing a poem simulating Dr. Seuss’ rhythm and rhyme scheme was not an easy task: Este detalle fue muy difícil para implementar porque costo mucho a tiempos encontrar palabras que pudieran comunicar el mensaje que quiera comunicar en esa línea y que también siguieran la estética de la rima, pero pienso que valió la pena (‘This detail was really difficult to implement because it took me a long time to find the words I needed to convey the message and that also followed the aesthetics and rhyme, but I think it was worth it’).

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Desde que era pequeño, Adrían sabía que era diferente

- Su manera de hablar lo distinguía como una estrella en su frente

- Habalaba el español, como hijo de hispanos

- Y también el ingles, como un americano

- Pero habían palabras en español que él no sabía

- ¡Y tal vez las decia incorrectas, pero todavía se entendían!

- Cuando en la clase, el siempre preguntaba,

- “¿Perdón profesora, puedo ir a la librería?”

- “¿Adrían, te refieres a la biblioteca?”, su profesora contestaba

- Y Adrían, confundido, solo se callaba

- En el camino para su casa, los errores de Adrían continuaron

- Tratando de conversar le pregunto a su abuelo, “Oye pa, que piensas de esa troka”

- Su abuelo, confundido, se puso el dedo enfrente de la boca

- Deapues le contesto, “¿Mijo de que hablas? ¿Que es una troka? ¿Hablas del camión?”

- Todo confundido, Adrían se calló

- No podía esperar llegar a casa, para hablar con su mamá de todo lo que oyo

- Cuando Adrían llegó a casa, su confusión continuaba

- Ahora para hablar con su papá, quien es de Guatemala

- Y también con su mamá, quien es de El Salvador

- “¿Hola cipote como estas?”, la mamá de Adrían comenzó

- “¿Porque lo llamas gordo?” el papá de Adrían respondió

- “¿Que es un cipote?”, Adrían preguntó

- “Quiere desir niño”, la mamá de Adrían contestó

- “¿Nino?”, el papá de Adrían preguntó,

- “Eso se refiere a ser gordo de donde yo soy!”

- Todavia un poco confundido, Adrían finalmente entendió

- Que ni su mama ni su papa podían hablar correctamante el “español”

- Que ni su maestra ni su abuelo hablaban correctamente el “español”

- Y que en realidad, nadie puede hablar correctamente el “español”

- Finalmente, entendio Adrían que esto es lo maravilloso de este lenguaje de comunicación

- Talvez hablamos palabritas diferentes, y hablamos u oimos con confusión

- ¡Pero al fin del día, todavía se entiende la intención!

- Cada dia que no me siento verdad

- Diciendo que soy parte de la comunidad

- Recuerdo que los otros no deciden

- Recuerdo que es mi identidad

- Aunque sea que estoy confundida

- Hay una cosa que sé con seguridad

- La artista que soy es por la herencia

- Un regalo de generaciones atrás

- A pesar de ambas culturas

- Soy latina y no cambiará

- La historia de familia es la mía

- Una transmito (I pass on) con Felicidad

- Late el corazón como marimba

- Tradiciones de antigüedad

- La historia de familia es la mía

- La historia de familia es la mía

- Y eso no se me olvidará

| 1 | The text I quote in Spanish is the original version used by students. Orthography is not normalized. |

| 2 | The phrases in English and Spanish are all originally written by the student. There is no translation here by the author. |

| 3 | This poem won a prize in the 8th National Symposium on the Spanish as Heritage Language, organized by the Institute for Language Education in Transcultural Context (ILETC), The Graduate Center, CUNY, on 13 May and 14 May 2021. |

References

- Aparicio, Francis. 1983. Teaching Spanish to the Native Speaker at the College Level. Hispania 66: 232–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, Sara, Angélica Amezcua, and Sergio Loza. 2020. Critical language awareness in the heritage language classroom: Design, implementation, and evaluation of a curricular intervention. International Multilingual Research Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, Sara, Cynthia Ducar, and Kim Potowski. 2014. Heritage Language Teaching: Research and Practice. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Bezemer, Jeff, and Gunther Kress. 2017. Continuity and change: Semiotic relations across multimodal texts in surgical education. Text&Talk 37: 509–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, Wendy. 1997. Poetry as a therapeutic process: Realigning art and the unconscious. In Teaching Lives: Essays and Stories. Logan: Utah State University Press, pp. 252–63. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, Robert, and Gabriel Guillén. 2020. Brave New Digital Classroom. In Technology and Foreign Language Learning, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. First published in 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Burgo, Clara. 2020. Writing Strategies to Develop Literacy Skills for Advanced Spanish Heritage Language Learner. SCOLT Dimension 2020: 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, María. 2004. Seeking explanatory adequacy: A dual approach to understanding the term ‘heritage language learner’. Heritage Language Journal 2: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, Geoffrey. 1988. Accommodation, resistance, and the politics of students writing. College Composition and Communication 39: 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Hsin-I. 2013. Identity practices of multilingual writers in social networking spaces. Language Learning & Technology 17: 143–70. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, Joan F. 2004. Heritage language literacy: Theory and practice. Heritage Language Journal 2: 1–19. Available online: http://www.heritagelanguages.org (accessed on 20 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Colombi, M. Cecilia. 2015. Academic and cultural literacy for heritage speakers of Spanish: A case study of Latin@ students in California. Linguistics and Education 32: 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durán, Leah Gordon. 2015. Audience awareness and the writing development of young bilingual children. Doctoral dissertation, University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Elola, Idoia, and Ana Oskoz. 2015. Toward Online and Hybrid Courses. In The Routledge Handbook in Hispanic Applied Linguistics. Edited by Manel Lacorte. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 221–37. [Google Scholar]

- Elola, Idoia, and Ana Oskoz. 2017. Writing with 21st century social tools in the L2 classroom: New literacies, genres, and writing practices. Journal of Second Language Writing 36: 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elola, Idoia, and Ariana M. Mikulski. 2013. Revisions in Real Time: Spanish Heritage Language Learners’ Writing Processes in English and Spanish. Foreign Language Annals 46: 646–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2003. Analyzing Discourse. Textual analysis for social research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Karen. 2021. Rompecabezas. Paper presented at The 8th National Symposium on Spanish as a Heritage Language, New York, NY, USA, May 13–15. Organized by the Institute for Language Education in Transcultural Context (ILETC), The Graduate Center, CUNY. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Juan. 2000. From Bomba to Hip-Hop. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Paulo. 2005. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 30th anniversary. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, and Wei Li. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism & Education. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, Henry A. 1991. Postmodernism as border pedagogy. In Postmodernism, Feminism, and Cultural Politics: Redrawing Educational Boundaries. Edited by Henry A. Giroux. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 217–56. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, Shirley Brice. 1991. The Sense of Being Literate: Historical and Cross-Cultural Features. In Handbook of Reading Research. Edited by Rebecca Barr, Michael L. Kamil, Peter B. Mosenthal and P. David Pearson. New York: Longman, vol. II, pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw, Florencia. 2016a. Online Courses for Heritage Learners: Best Practices and Lessons Learned. In Advances in Spanish as a Heritage Language. Edited by D. Pascual y Cabo. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 281–98. [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw, Florencia. 2016b. Technology-Enhanced Heritage Language Instruction: Best Tools and Best Practices. In Innovative Strategies for Heritage Language Teaching: A Practical Guide for the Classroom. Edited by Sara Beaudrie and Marta Fairclough. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 237–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatieva, Natalia, and M. Cecilia Colombi. 2014. El lenguaje académico en México y en los Estados Unidos: Un análisis sistémico Funcional. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt, Carey. 2008. Technology, Literacy and Learning: A Multimodal Approach. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantzis, Mary, and Bill Cope. 2005. Learning by Design. Melbourne: Common Ground. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantzis, Mary, Bill Cope, Eveline Chan, and Leanne Dalley-Trim. 2016. Literacies, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kastman Breuch, Lee-Ann M. 2002. Post-Process Pedagogy: A Philosophical Exercise. JAC 22: 119–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, Richard. 2004. Literacy and advanced foreign language learning: Rethinking the curriculum. In Advanced Foreign Language Learning: A Challenge to College Programs. Edited by Heidi Byrnes and Hiram H. Maxim. Heinle: Boston, vol. 1, pp. 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunter. 2000. Text as the punctuation of semiosis: Pulling at some threads. In Intertextuality and the Media: From Genre to Everyday Life. Edited by Ulrike Meinhof and Jonathon Smith. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 132–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunther. 2004. Reading images: Multimodality, representation and new media. Information Design Journal Document Design. 12: 110–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, Gunther. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, Jennifer, and Ellen Serafini. 2016. Sociolinguistics for heritage language educators and students: A model for critical translingual competence. In Innovative Strategies for Heritage Language Teaching: A Practical Guide for the Classroom. Edited by Marta Fairclough and Sara Beaudrie. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 56–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, Rossy. Forthcoming. El uso de la escritura creativa para el desarrollo de la lecto-escritura en hablantes de español como lengua de herencia: Un acercamiento práctico. In El español como lengua de herencia. Edited by Diego Pascual y Cabo and Julio Torres. London: Routledge Press.

- Lionnet, Françoise. 1989. Autobiographical Voices: Race, Gender, Self-Portraiture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lomicka, Lara. 2020. Creating and Sustaining Virtual Communities. Foreign Language Annals. Summer. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/flan.12456 (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Loureiro-Rodriguez, Verónica. 2013. Meaningful writing in the heritage language class: A case study of heritage learners of Spanish in Canada. L2 Journal 5. Available online: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/3mp064qx (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Martínez, Glenn, and Karim San Martín. 2018. Language and Power in a Medical Spanish for Heritage Learners Program: A Learning by Design Perspective. In Multiliteracies Pedagogy and Language Learning. Teaching Spanish to Heritage Speakers. Edited by Gabriela Zapata and Manel Lacorte. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 107–28. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Glenn. 2005. Genres and Genre Chains: Post-Process Perspectives on HL Writing. Southwest Journal of Linguistics 24: 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Glenn. 2007. Writing Back and Forth: The Interplay of Form and Situation in Heritage Language Composition. Language Teaching Research 11: 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Glenn. 2016. Goals and beyond in Heritage Language Education: From Competencies to Capabilities. In Innovative Strategies for Heritage Language Teaching: A Practical Guide for the Classroom. Edited by Sara Beaudrie and Marta Fairclough. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mkhitarian, Elizabeth. 2019. While I make a poem, I am being made by poetry. Creative writing in heritage language instruction. In Western Armenian in the 21st Century: Challenges and New Approaches. Edited by Barlow Der Matossian and Bedross Der Mugrdechian. Freso: California State University Press, pp. 131–43. [Google Scholar]

- Morales Kearns, Rosalie. 2009. Voice of Authority: Theorizing Creative Wring Pedagogy. College Composition and Communication 60: 790–807. [Google Scholar]

- Mrak, Ariana. 2020. Developing Writing in Spanish Heritage Language Learners: An Integrated Process Approach. SCOLT Dimension 2020: 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete, Federico. 2020. La blanquitud y la blancura, cumbre del racismo mexicano. Revista de la Universidad de México. Dossier Racismo. Available online: https://www.revistadelauniversidad.mx/articles/ca12bb18-2c40-40dc-add6-b0acd62fafbd/la-blanquitud-y-la-blancura-cumbre-del-racismo-mexicano (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- New London Group. 1996. A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures. Harvard Educational Review 66: 60–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskoz, Ana, and Idoia Elola. 2016. Digital stories: Bringing multimodal texts to the Spanish writing classroom. ReCALL 28: 326–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskoz, Ana, and Idoia Elola. 2020. Digital L2 Writing Literacies. London: Equinox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, Derek. 1993. Composing as the voicing of multiple fictions. In Into the Field. Edited by Anne Ruggles Gere. New York: Modern Language Association of America, pp. 159–75. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, María Luisa. 2013. Expanding Language and Cultural Competence in Advanced Heritage- and Foreign-Language Learners through Community Engagement and work with the Arts. Heritage Language Journal 10: 115–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, María Luisa. 2014. Strengthening our teacher community: Consolidating a ’signature pedagogy’ for the teaching of Spanish as heritage language. In Rethinking Heritage Language Education. Edited by Peter P. Trifonas and Themistoklis Aravossitas. The Cambridge Education Research Series; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 213–136. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, María Luisa. 2016. Understanding Identity among Spanish Heritage Learners: An Interdisciplinary Endeavor. In Advances in Spanish as a Heritage Language. Diego Pascual y Cabo. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 177–204. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, María Luisa. 2017. Beyond academic language: Creative writing for empowering heritage identities. Paper presented at 10th Heritage Language Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana, Champaign, IL, USA, May 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, María Luisa, Araceli Otero, Rosa Flores, and Marguerite Lavellé. 2018. Designing a Comprehensive Course for Advanced Spanish Heritage Learners: Contributions from the Multiliteracies Framework. In Multiliteracies Pedagogy and Language Learning. Teaching Spanish to Heritage Speakers. Edited by G. Zapata and M. Lacorte. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 27–66. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, María Luisa. 2021a. La literacidad múltiple en el aprendizaje del español como lengua de herencia. In El español como lengua de herencia. Edited by Diego Pascual y Cabo and Julio Torres. New York: Routledge Press, pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, María Luisa. 2021b. La enseñanza del español a la juventud latina. Madrid: Arco Libros/La Muralla. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlenko, Aneta, and James P. Lantolf. 2000. Second language learning as participation and the (re)construction of selves. In Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning. Edited by James P. Lantolf. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 155–77. [Google Scholar]

- Potowski, Kim. 2012. Identity and heritage learners: Moving beyond essentializations. In Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States. The State of the Field. Edited by Sara María Beaudrie y and Marta Fairclough. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 179–202. [Google Scholar]

- Potowski, Kim. 2005. Fundamentos de la enseñanza del español a hispanohablantes en los EE.UU. [Foundations of the teaching of Spanish to Spanish speakers in the U.S.]. Madrid: Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Prada, Josh. 2019. Exploring the role of translanguaging in linguistic ideological and attitudinal reconfigurations in the Spanish classroom for heritage speakers. Classroom Discourse 10: 306–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, Josh. Forthcoming. Translanguaging thining y el español como lengua de herencia. In El español como lengua de herencia. Edited by Diego Pascual y Cabo and Julio Torres. London: Routledge Press.

- Reznicek-Parrado, M. Lina. 2014. The personal essay and academic writing proficiency in Spanish heritage language development. Arizona Working Papers in SLA & Teaching 21: 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rosaldo, Renato. 1993. Culture & Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis: With a New Introduction. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rovai, Alfred P. 2002. Building sense of community at a distance. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 3: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Royster, Brent. 2005. Inspiration, creativity, and crisis: The Romantic myth of the writer meets the postmodern classroom. In Power and Identity in the Creative Writing Classroom. Edited by Anna Leahy. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Muñoz, Ana. 2016. Heritage language healing? Learners’ attitudes and damage control in a heritage language classroom. In Advances in Spanish as a Heritage Language. Edited by Diego Pascual y Cabo. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 205–20. [Google Scholar]

- Schleppegrell, Mary J., and María Cecilia Colombi. 1997. Text Organization by Bilingual Writers. Written Communication 14: 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, Frank. 2014. Reading the Visual: An Introduction to Teaching Multimodal Literacy. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Serafini, Frank. 2015. Multimodal Literacy: From Theories to Practices. Language Arts 92: 412–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeter, Christine E., and Peter McLaren. 1995. Multicultural Education, Critical Pedagogy, and the Politics of Difference. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer-Escalante, María. 2005. Writing in Two Languages/Living in Two Worlds: A Rhetorical Analysis of Mexican-American Written Discourse. In Latino Language and Literacy in Ethnolinguistic Chicago. Edited by Marcia Farr. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 217–44. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Pippa. 2008. Multimodal Pedagogies in Diverse Classrooms: Representation, Rights and Resources. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tavalin, Fern. 1995. Context for Creativity: Listening to Voices, Allowing a Pause. The Journal of Creative Behavior 29: 133–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, Julio, Diego Pascual, and John Beusterien. 2017. What’s next? Heritage language learners shape news paths in Spanish teaching. Hispania 100: 271–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueland, Brenda. 2014. If You Want to Write, 1st ed. Floyd: Sublime Books. First published 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, Guadalupe, Sonia V. González, Dania López García, and Patricio Márquez. 2008. Ideologies of monolingualism: The challenges of maintaining non-English languages through educational institutions. In Heritage Language Acquisition: A New Field Emerging. Edited by Donna M. Brinton and Olga Kagan. New York: Routledge, pp. 107–30. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 1978. A comprehensive approach to the teaching of Spanish to bilingual Spanish-speaking students. The Modern Language Journal 62: 102–10. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, Daniel. 2004. No nos dejaremos: Writing in Spanish as an Act of Resistance. In Latino/a Discourses on Language, Identity & Literacy Education. Edited by Michelle Hall Kells, Valerie Balester and Victor Villanueva. Portsmouth: Heinemann, pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, Laura, and J. José del Valle. 2015. The Politics of Spanish in the World. In The Routledge Handbook in Hispanic Applied Linguistics. Edited by Manel Lacorte. London: Routledge, pp. 571–87. [Google Scholar]

- Xerri, Daniel. 2012. Poetry Teaching and Multimodality: Theory into Practice. Creative Education 3: 507–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoder Miller, Evie. 2005. Reinventing Writing Classrooms: The Combination of Creating and Composing. In Power and Identity in the Creative Writing Classroom. Edited by Anna Leahy. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, Gabriela. 2018. The Role of Digital, Learning by Design Instructional Materials in the Development of Spanish Heritage Learners’ Literacy Skills. In Multiliteracies Pedagogy and Language Learning. Teaching Spanish to Heritage Speakers. Edited by Gabriela Zapata and Manel Lacorte. London: Palgrave, pp. 67–106. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parra, M.L. Strengthening Writing Voices and Identities: Creative Writing, Digital Tools and Artmaking for Spanish Heritage Courses. Languages 2021, 6, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030117

Parra ML. Strengthening Writing Voices and Identities: Creative Writing, Digital Tools and Artmaking for Spanish Heritage Courses. Languages. 2021; 6(3):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030117

Chicago/Turabian StyleParra, María Luisa. 2021. "Strengthening Writing Voices and Identities: Creative Writing, Digital Tools and Artmaking for Spanish Heritage Courses" Languages 6, no. 3: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030117

APA StyleParra, M. L. (2021). Strengthening Writing Voices and Identities: Creative Writing, Digital Tools and Artmaking for Spanish Heritage Courses. Languages, 6(3), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030117